User login

Endocrine Mucin-Producing Sweat Gland Carcinoma and Primary Cutaneous Mucinous Carcinoma: A Case Series

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) and

Methods

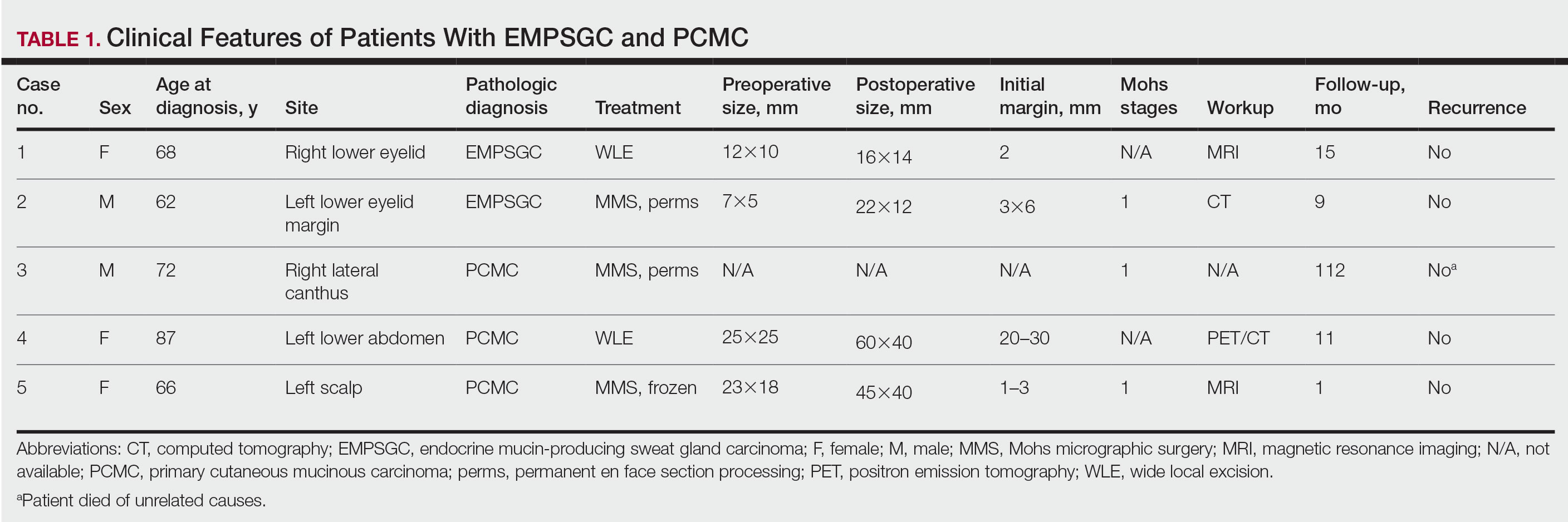

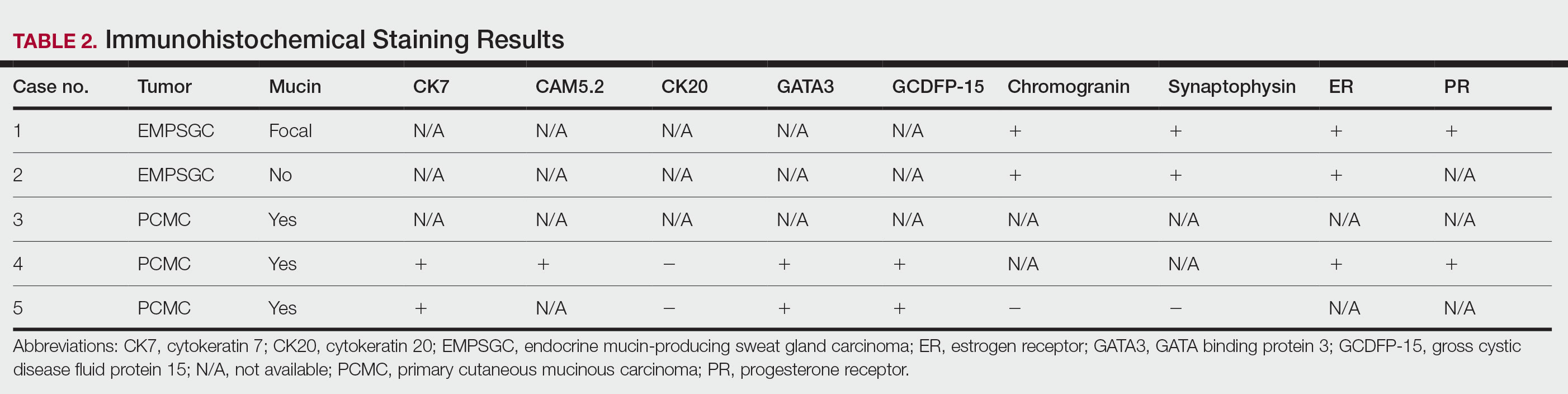

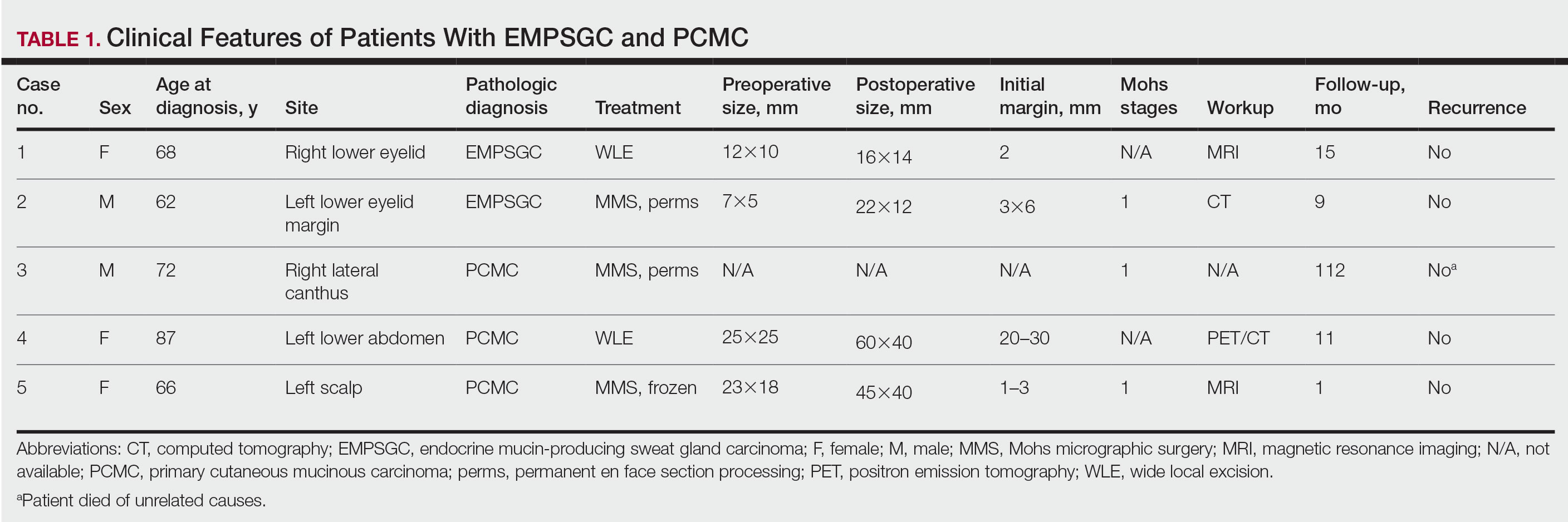

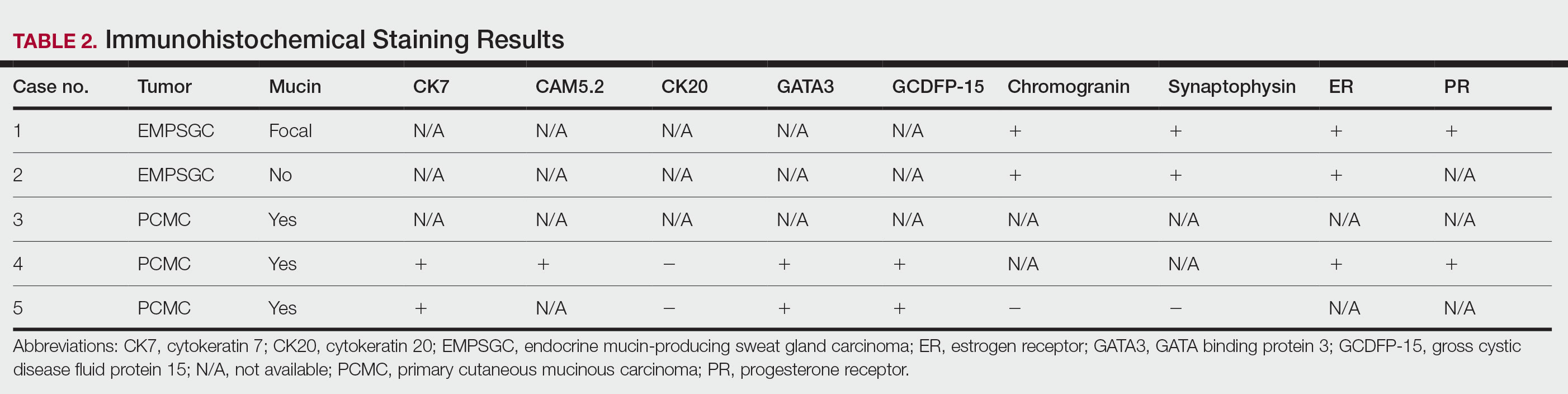

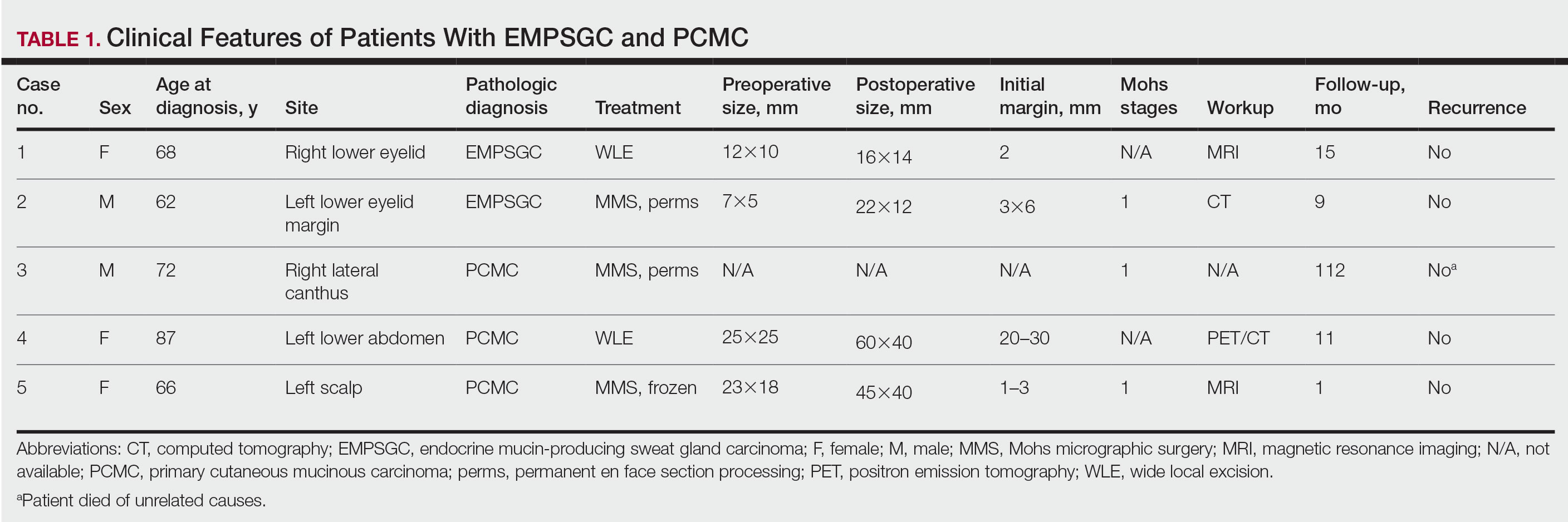

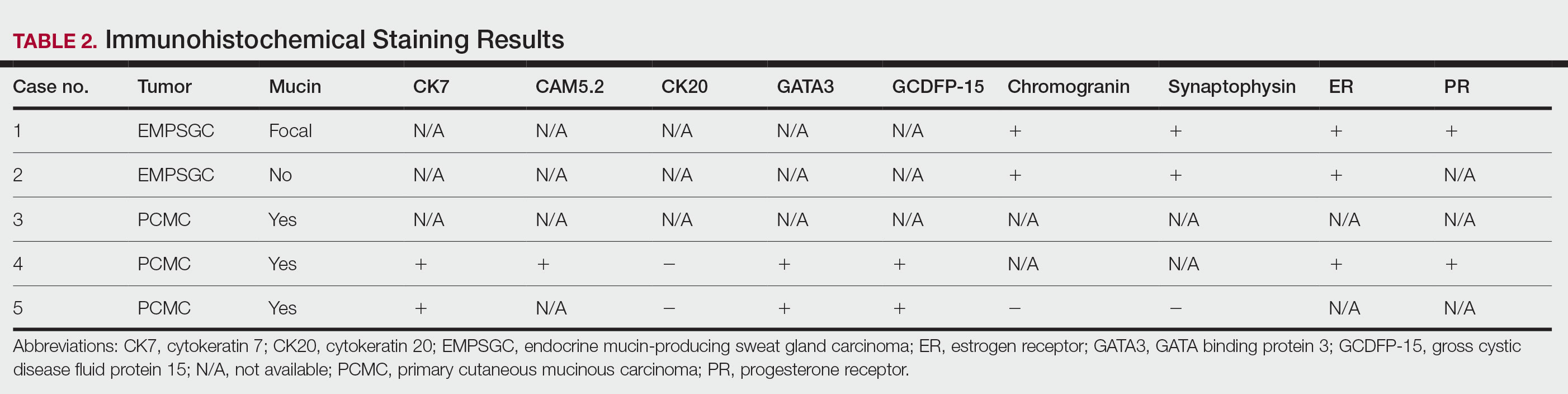

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective, single-institution case series. We searched electronic medical records dating from 2000 to 2019 for tumors diagnosed as PCMC or extramammary Paget disease treated with MMS. We gathered demographic, clinical, pathologic, and follow-up information from the electronic medical records for each case (Tables 1 and 2). Two dermatopathologists (B.P. and B.F.K.) reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each tumor as well as all available immunohistochemical stains. One of the reviewers (B.F.K.) is a board-certified dermatologist, dermatopathologist, and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Information—We identified 2 cases of EMPSGC and 3 cases of PCMC diagnosed and treated at our institution; 4 of these cases had been treated within the last 2 years. One had been treated 18 years prior; case information was limited due to planned institutional record destruction. Three of the patients were female and 2 were male. The mean age at presentation was 71 years (range, 62–87 years). None had experienced recurrence or metastases after a mean follow-up of 30 months.

Case 1—A 68-year-old woman noted a slow-growing, flesh-colored papule measuring 12×10 mm on the right lower eyelid. An excisional biopsy was completed with 2-mm clinical margins, and the defect was closed in a linear fashion. Histologic sections demonstrated EMPSGC with uninvolved margins. The patient desired no further intervention and was clinically followed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck found no evidence of metastasis. She has had no recurrence after 15 months.

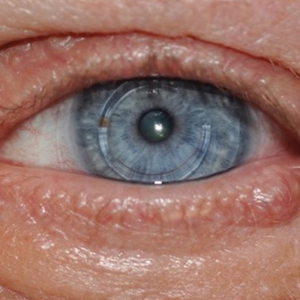

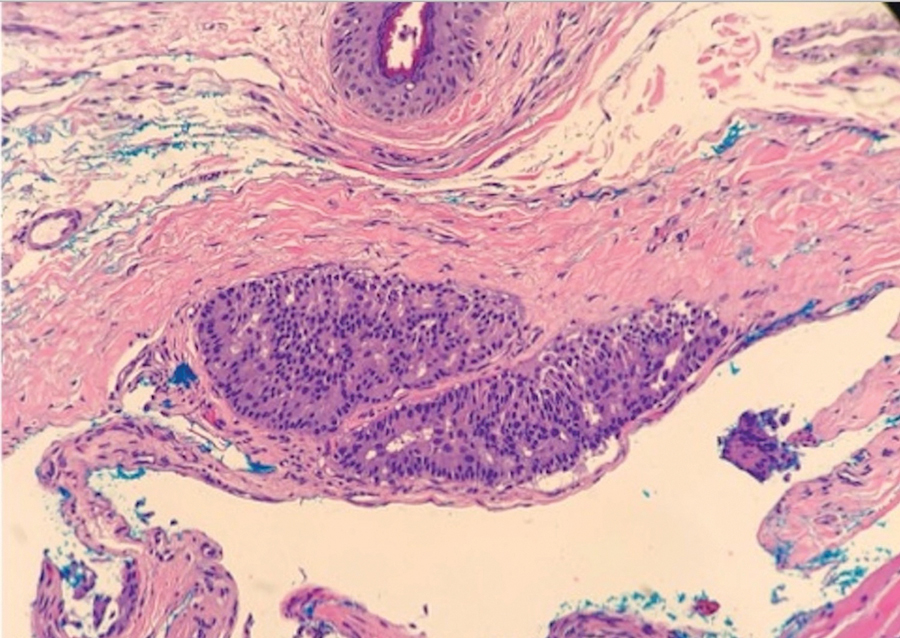

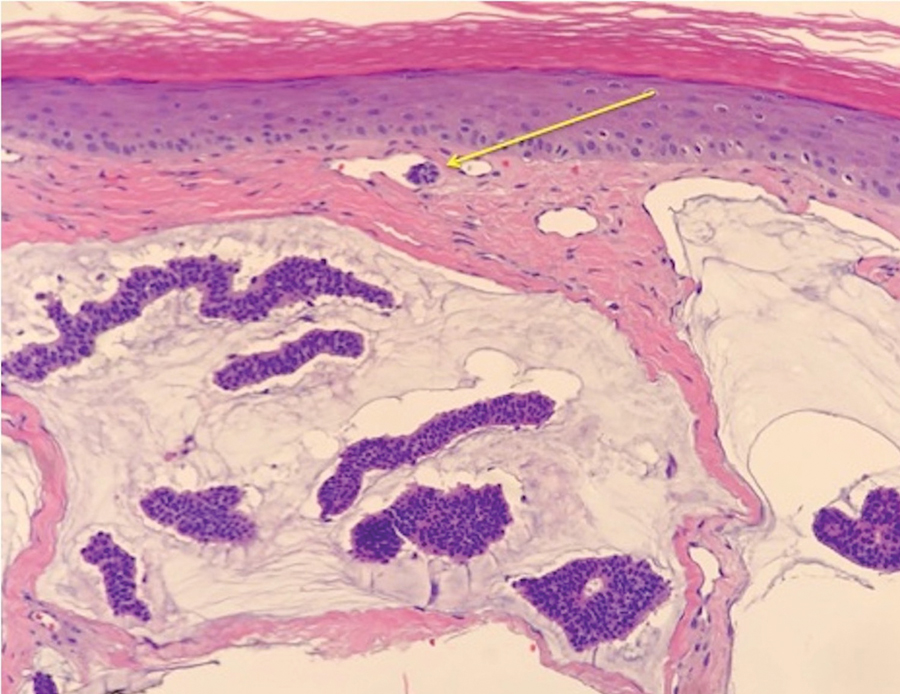

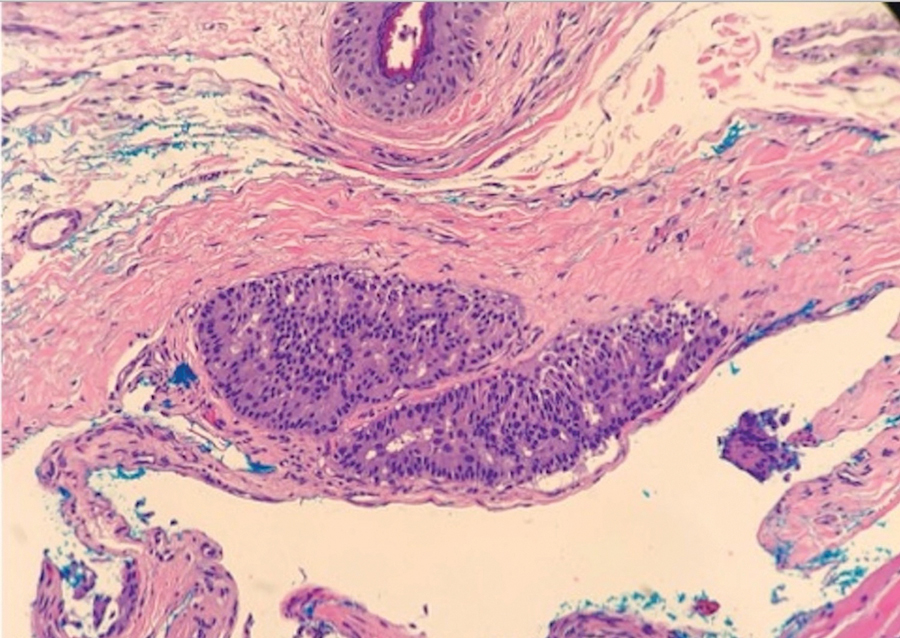

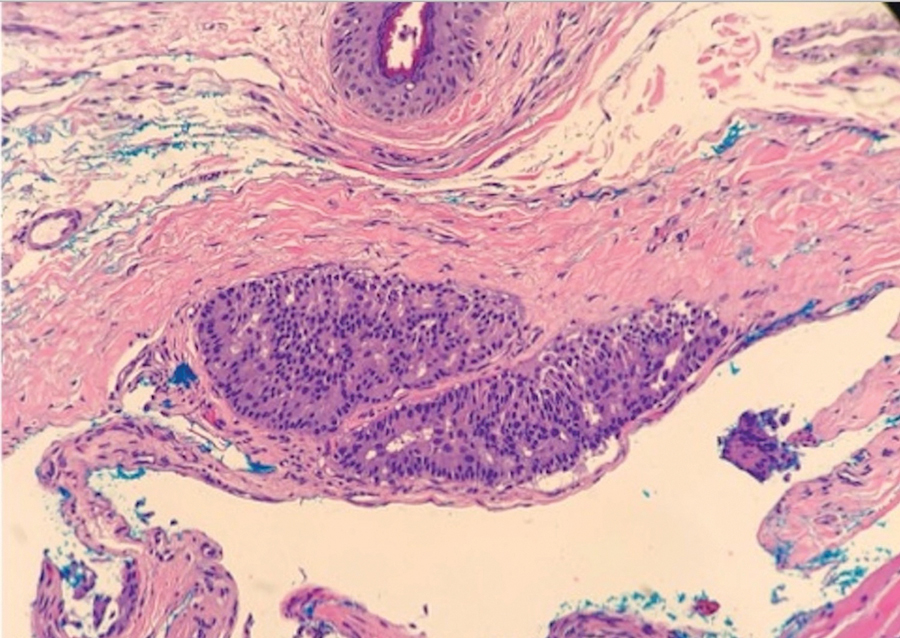

Case 2—A 62-year-old man presented with a 7×5-mm, flesh-colored papule on the left lower eyelid margin (Figure 1). It was previously treated conservatively as a hordeolum but was biopsied after it failed to resolve with 3-mm margins. Histopathology demonstrated an EMPSGC (Figure 2). The lesion was treated with modified MMS with permanent en face section processing and cleared after 1 stage. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no abnormalities. He has had no recurrence after 9 months.

Case 3—A 72-year-old man presented with a nontender papule near the right lateral canthus. A punch biopsy demonstrated PCMC. He was treated via modified MMS with permanent en face section processing. The tumor was cleared in 1 stage. He showed no evidence of recurrence after 112 months and died of unrelated causes. The rest of his clinical information was limited because of planned institutional destruction of records.

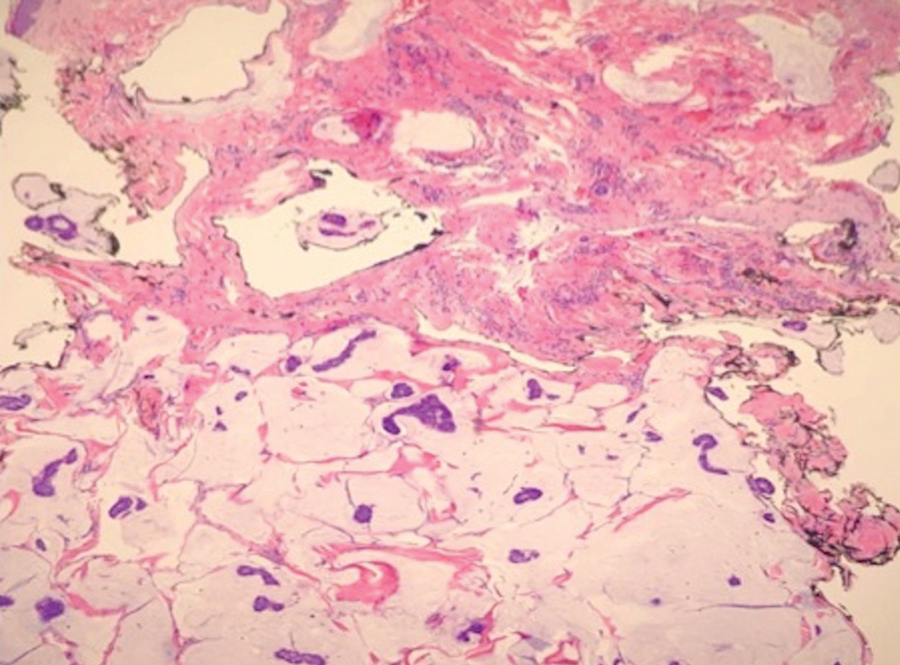

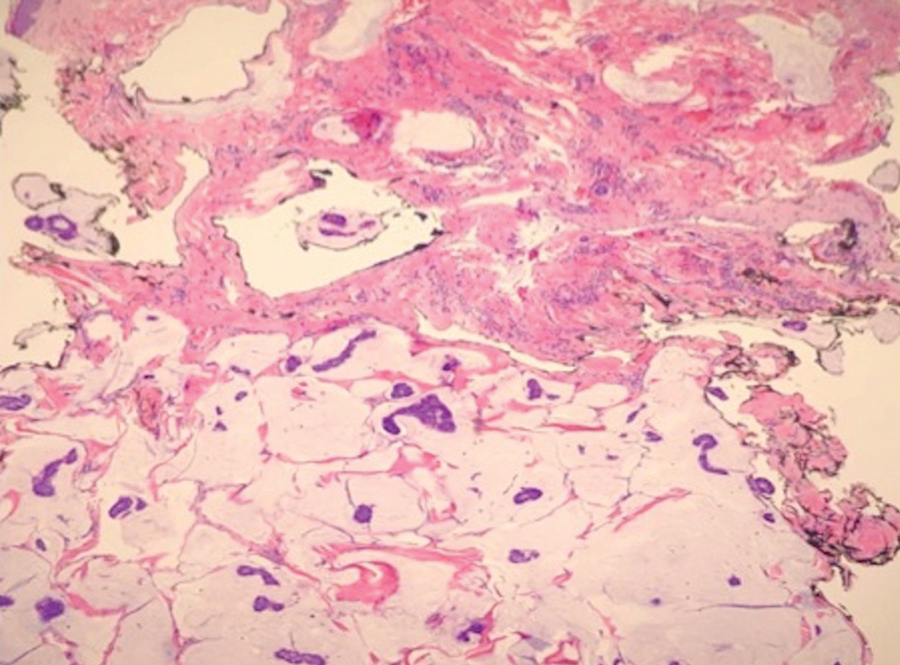

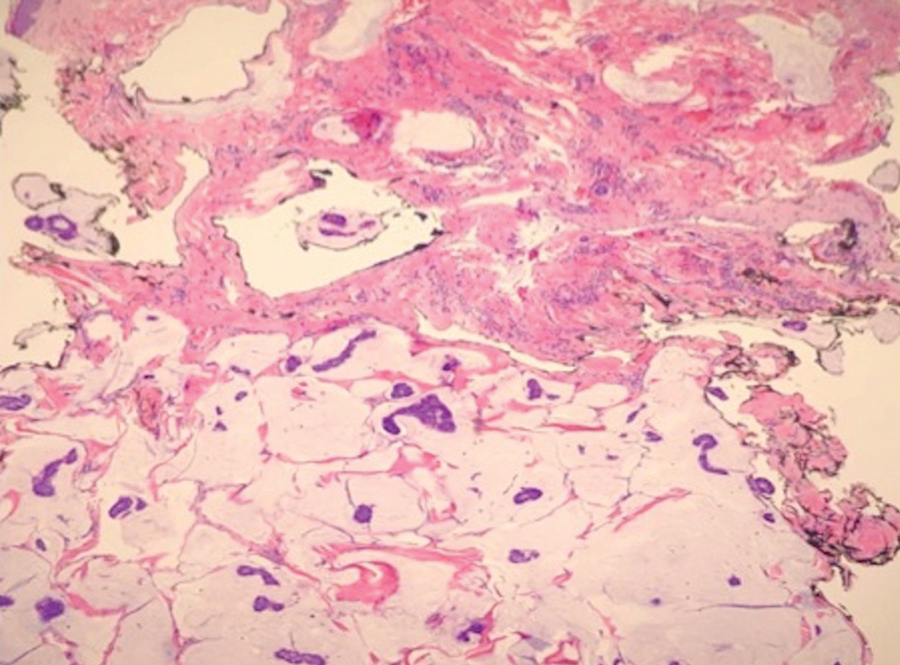

Case 4—An 87-year-old woman presented with a 25×25-mm, slow-growing mass of 12 months’ duration on the left lower abdomen (Figure 3). A biopsy demonstrated PCMC (Figure 4). Because of the size of the lesion, she underwent WLE with 20- to 30-mm margins by a general surgeon under general anesthesia. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography was unremarkable. She has remained disease free for 11 months.

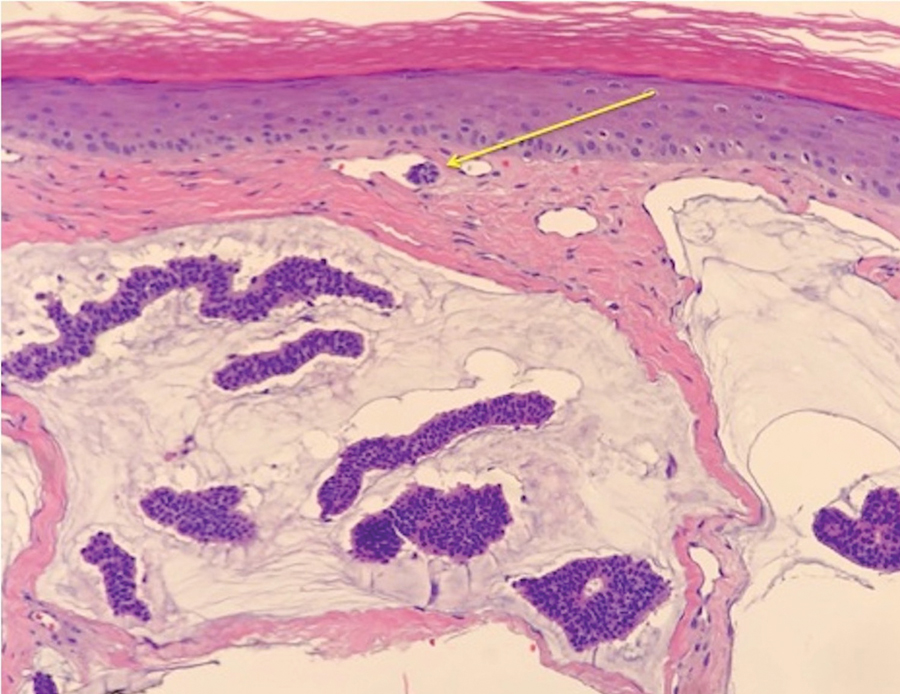

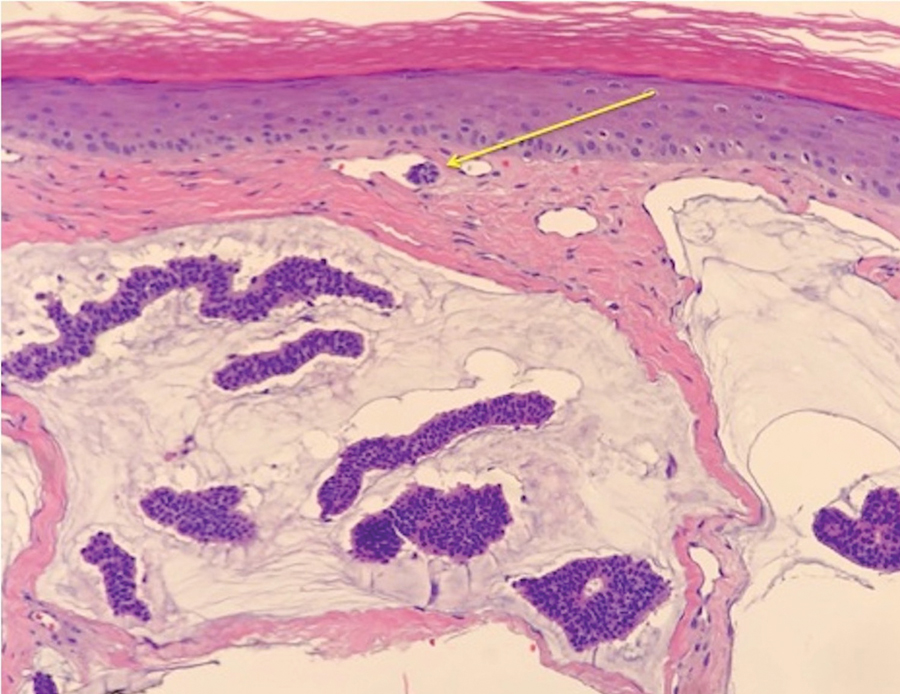

Case 5—A 66-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a posterior scalp mass measuring 23×18 mm that had grown over the last 24 months. Biopsy showed mucinous carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion consistent with PCMC (Figure 5) confirmed on multiple tissue levels and with the aid of immunohistochemistry. She was sent for an MRI of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which demonstrated 2 enlarged postauricular lymph nodes and raised suspicion for metastatic disease vs reactive lymphadenopathy. Mohs micrographic surgery with frozen sections was performed with 1- to 3-mm margins; the final layer was sent for permanent processing and confirmed negative margins. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphadenectomy of the 2 nodes present on imaging showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient had no recurrence in 1 month.

Comment

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and PCMC are sweat gland malignancies that carry low metastatic potential but are locally aggressive. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma has a strong predilection for the periorbital region, especially the lower eyelids of older women.3 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma may arise on the eyelids, scalp, axillae, and trunk and has been reported more often in older men. These slow-growing tumors appear as nonspecific nodules.3 Lesions frequently are asymptomatic but rarely may cause pruritus and bleeding. Histologically, EMPSGC appears as solid or cystic nodules of cells with a papillary, cribriform, or pseudopapillary appearance. Intracellular or extracellular mucin as well as malignant spread of tumor cells along pre-existing ductlike structures make it difficult to histologically distinguish EMPSGC from ductal carcinoma in situ.3

A key histopathologic feature of PCMC is basophilic epithelioid cell nests in mucinous lakes.4 Rosettelike structures are seen within solid areas of the tumor. Fibrous septae separate individual collections of mucin, creating a lobulated appearance. The histopathologic differential diagnosis of EMPSGC and PCMC is broad, including basal cell carcinoma, hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Positive expression of at least 1 neuroendocrine marker (ie, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin) and low-molecular cytokeratin (cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, Ber-EP4) can aid in the diagnosis of both EMPSGC and PCMC.4 The use of p63 immunostaining is beneficial in delineating adnexal neoplasms. Adnexal tumors that stain positively with p63 are more likely to be of primary cutaneous origin, whereas lack of p63 staining usually denotes a secondary metastatic process. However, p63 staining is less reliable when distinguishing primary and metastatic mucinous neoplasms. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas often stain positive with p63, while PCMC usually stains negative despite its primary cutaneous origin, decreasing the clinical utility of p63. The tumor may be identical to metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and pancreas. Tumor islands floating in mucin are identified in both primary cutaneous and metastatic disease to the skin.3,6 Areas of tumor necrosis, notable atypia, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion are infrequently reported in EMPSGC or PCMC, though lymphatic invasion was identified in case 5 presented herein.

A metastatic workup is warranted in all cases of PCMC, including a thorough history, review of systems, breast examination, and imaging. A workup may be considered in cases of EMPSGC depending on histologic features or clinical history.

There is uncertainty regarding the optimal management of these slow-growing yet locally destructive tumors.5 The incidence of local recurrence of PCMC after WLE with narrow margins of at least 1 cm can be as high as 30% to 40%, especially on the eyelid.4 There is no consensus on surgical care for either of these tumors.5 Because of the high recurrence rate and the predilection for the eyelid and face, MMS provides an excellent alternative to WLE for tissue preservation and meticulous margin control. We advocate for the use of the Mohs technique with permanent sectioning, which may delay the repair, but reviewing tissue with permanent fixation improves the quality and accuracy of the margin evaluation because these tumors often are infiltrative and difficult to delineate under frozen section processing. Permanent en face sectioning allows the laboratory to utilize the full array of immunohistochemical stains for these tumors, providing accurate and timely results.

Limitations to our retrospective uncontrolled study include missing or incomplete data points and short follow-up time. Additionally, there was no standardization to the margins removed with MMS or WLE because of the limited available data that comment on appropriate margins.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Kutzner H, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 11 cases with emphasis on MYB immunoexpression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:674-680.

- Navrazhina K, Petukhova T, Wildman HF, et al. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:887-889.

- Scott BL, Anyanwu CO, Vandergriff T, et al. Endocrine mucin–producing sweat gland carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1498-1500.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, et al. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2010;44:97-100.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Bulliard C, Murali R, Maloof A, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:812-816.

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) and

Methods

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective, single-institution case series. We searched electronic medical records dating from 2000 to 2019 for tumors diagnosed as PCMC or extramammary Paget disease treated with MMS. We gathered demographic, clinical, pathologic, and follow-up information from the electronic medical records for each case (Tables 1 and 2). Two dermatopathologists (B.P. and B.F.K.) reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each tumor as well as all available immunohistochemical stains. One of the reviewers (B.F.K.) is a board-certified dermatologist, dermatopathologist, and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Information—We identified 2 cases of EMPSGC and 3 cases of PCMC diagnosed and treated at our institution; 4 of these cases had been treated within the last 2 years. One had been treated 18 years prior; case information was limited due to planned institutional record destruction. Three of the patients were female and 2 were male. The mean age at presentation was 71 years (range, 62–87 years). None had experienced recurrence or metastases after a mean follow-up of 30 months.

Case 1—A 68-year-old woman noted a slow-growing, flesh-colored papule measuring 12×10 mm on the right lower eyelid. An excisional biopsy was completed with 2-mm clinical margins, and the defect was closed in a linear fashion. Histologic sections demonstrated EMPSGC with uninvolved margins. The patient desired no further intervention and was clinically followed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck found no evidence of metastasis. She has had no recurrence after 15 months.

Case 2—A 62-year-old man presented with a 7×5-mm, flesh-colored papule on the left lower eyelid margin (Figure 1). It was previously treated conservatively as a hordeolum but was biopsied after it failed to resolve with 3-mm margins. Histopathology demonstrated an EMPSGC (Figure 2). The lesion was treated with modified MMS with permanent en face section processing and cleared after 1 stage. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no abnormalities. He has had no recurrence after 9 months.

Case 3—A 72-year-old man presented with a nontender papule near the right lateral canthus. A punch biopsy demonstrated PCMC. He was treated via modified MMS with permanent en face section processing. The tumor was cleared in 1 stage. He showed no evidence of recurrence after 112 months and died of unrelated causes. The rest of his clinical information was limited because of planned institutional destruction of records.

Case 4—An 87-year-old woman presented with a 25×25-mm, slow-growing mass of 12 months’ duration on the left lower abdomen (Figure 3). A biopsy demonstrated PCMC (Figure 4). Because of the size of the lesion, she underwent WLE with 20- to 30-mm margins by a general surgeon under general anesthesia. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography was unremarkable. She has remained disease free for 11 months.

Case 5—A 66-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a posterior scalp mass measuring 23×18 mm that had grown over the last 24 months. Biopsy showed mucinous carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion consistent with PCMC (Figure 5) confirmed on multiple tissue levels and with the aid of immunohistochemistry. She was sent for an MRI of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which demonstrated 2 enlarged postauricular lymph nodes and raised suspicion for metastatic disease vs reactive lymphadenopathy. Mohs micrographic surgery with frozen sections was performed with 1- to 3-mm margins; the final layer was sent for permanent processing and confirmed negative margins. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphadenectomy of the 2 nodes present on imaging showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient had no recurrence in 1 month.

Comment

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and PCMC are sweat gland malignancies that carry low metastatic potential but are locally aggressive. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma has a strong predilection for the periorbital region, especially the lower eyelids of older women.3 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma may arise on the eyelids, scalp, axillae, and trunk and has been reported more often in older men. These slow-growing tumors appear as nonspecific nodules.3 Lesions frequently are asymptomatic but rarely may cause pruritus and bleeding. Histologically, EMPSGC appears as solid or cystic nodules of cells with a papillary, cribriform, or pseudopapillary appearance. Intracellular or extracellular mucin as well as malignant spread of tumor cells along pre-existing ductlike structures make it difficult to histologically distinguish EMPSGC from ductal carcinoma in situ.3

A key histopathologic feature of PCMC is basophilic epithelioid cell nests in mucinous lakes.4 Rosettelike structures are seen within solid areas of the tumor. Fibrous septae separate individual collections of mucin, creating a lobulated appearance. The histopathologic differential diagnosis of EMPSGC and PCMC is broad, including basal cell carcinoma, hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Positive expression of at least 1 neuroendocrine marker (ie, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin) and low-molecular cytokeratin (cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, Ber-EP4) can aid in the diagnosis of both EMPSGC and PCMC.4 The use of p63 immunostaining is beneficial in delineating adnexal neoplasms. Adnexal tumors that stain positively with p63 are more likely to be of primary cutaneous origin, whereas lack of p63 staining usually denotes a secondary metastatic process. However, p63 staining is less reliable when distinguishing primary and metastatic mucinous neoplasms. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas often stain positive with p63, while PCMC usually stains negative despite its primary cutaneous origin, decreasing the clinical utility of p63. The tumor may be identical to metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and pancreas. Tumor islands floating in mucin are identified in both primary cutaneous and metastatic disease to the skin.3,6 Areas of tumor necrosis, notable atypia, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion are infrequently reported in EMPSGC or PCMC, though lymphatic invasion was identified in case 5 presented herein.

A metastatic workup is warranted in all cases of PCMC, including a thorough history, review of systems, breast examination, and imaging. A workup may be considered in cases of EMPSGC depending on histologic features or clinical history.

There is uncertainty regarding the optimal management of these slow-growing yet locally destructive tumors.5 The incidence of local recurrence of PCMC after WLE with narrow margins of at least 1 cm can be as high as 30% to 40%, especially on the eyelid.4 There is no consensus on surgical care for either of these tumors.5 Because of the high recurrence rate and the predilection for the eyelid and face, MMS provides an excellent alternative to WLE for tissue preservation and meticulous margin control. We advocate for the use of the Mohs technique with permanent sectioning, which may delay the repair, but reviewing tissue with permanent fixation improves the quality and accuracy of the margin evaluation because these tumors often are infiltrative and difficult to delineate under frozen section processing. Permanent en face sectioning allows the laboratory to utilize the full array of immunohistochemical stains for these tumors, providing accurate and timely results.

Limitations to our retrospective uncontrolled study include missing or incomplete data points and short follow-up time. Additionally, there was no standardization to the margins removed with MMS or WLE because of the limited available data that comment on appropriate margins.

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma (EMPSGC) and

Methods

Following institutional review board approval, we conducted a retrospective, single-institution case series. We searched electronic medical records dating from 2000 to 2019 for tumors diagnosed as PCMC or extramammary Paget disease treated with MMS. We gathered demographic, clinical, pathologic, and follow-up information from the electronic medical records for each case (Tables 1 and 2). Two dermatopathologists (B.P. and B.F.K.) reviewed the hematoxylin and eosin–stained slides of each tumor as well as all available immunohistochemical stains. One of the reviewers (B.F.K.) is a board-certified dermatologist, dermatopathologist, and fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon.

Results

Demographic and Clinical Information—We identified 2 cases of EMPSGC and 3 cases of PCMC diagnosed and treated at our institution; 4 of these cases had been treated within the last 2 years. One had been treated 18 years prior; case information was limited due to planned institutional record destruction. Three of the patients were female and 2 were male. The mean age at presentation was 71 years (range, 62–87 years). None had experienced recurrence or metastases after a mean follow-up of 30 months.

Case 1—A 68-year-old woman noted a slow-growing, flesh-colored papule measuring 12×10 mm on the right lower eyelid. An excisional biopsy was completed with 2-mm clinical margins, and the defect was closed in a linear fashion. Histologic sections demonstrated EMPSGC with uninvolved margins. The patient desired no further intervention and was clinically followed. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck found no evidence of metastasis. She has had no recurrence after 15 months.

Case 2—A 62-year-old man presented with a 7×5-mm, flesh-colored papule on the left lower eyelid margin (Figure 1). It was previously treated conservatively as a hordeolum but was biopsied after it failed to resolve with 3-mm margins. Histopathology demonstrated an EMPSGC (Figure 2). The lesion was treated with modified MMS with permanent en face section processing and cleared after 1 stage. Computed tomography of the head and neck showed no abnormalities. He has had no recurrence after 9 months.

Case 3—A 72-year-old man presented with a nontender papule near the right lateral canthus. A punch biopsy demonstrated PCMC. He was treated via modified MMS with permanent en face section processing. The tumor was cleared in 1 stage. He showed no evidence of recurrence after 112 months and died of unrelated causes. The rest of his clinical information was limited because of planned institutional destruction of records.

Case 4—An 87-year-old woman presented with a 25×25-mm, slow-growing mass of 12 months’ duration on the left lower abdomen (Figure 3). A biopsy demonstrated PCMC (Figure 4). Because of the size of the lesion, she underwent WLE with 20- to 30-mm margins by a general surgeon under general anesthesia. Positron emission tomography/computed tomography was unremarkable. She has remained disease free for 11 months.

Case 5—A 66-year-old woman presented for evaluation of a posterior scalp mass measuring 23×18 mm that had grown over the last 24 months. Biopsy showed mucinous carcinoma with lymphovascular invasion consistent with PCMC (Figure 5) confirmed on multiple tissue levels and with the aid of immunohistochemistry. She was sent for an MRI of the head, neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis, which demonstrated 2 enlarged postauricular lymph nodes and raised suspicion for metastatic disease vs reactive lymphadenopathy. Mohs micrographic surgery with frozen sections was performed with 1- to 3-mm margins; the final layer was sent for permanent processing and confirmed negative margins. Sentinel lymph node biopsy and lymphadenectomy of the 2 nodes present on imaging showed no evidence of metastasis. The patient had no recurrence in 1 month.

Comment

Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and PCMC are sweat gland malignancies that carry low metastatic potential but are locally aggressive. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma has a strong predilection for the periorbital region, especially the lower eyelids of older women.3 Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma may arise on the eyelids, scalp, axillae, and trunk and has been reported more often in older men. These slow-growing tumors appear as nonspecific nodules.3 Lesions frequently are asymptomatic but rarely may cause pruritus and bleeding. Histologically, EMPSGC appears as solid or cystic nodules of cells with a papillary, cribriform, or pseudopapillary appearance. Intracellular or extracellular mucin as well as malignant spread of tumor cells along pre-existing ductlike structures make it difficult to histologically distinguish EMPSGC from ductal carcinoma in situ.3

A key histopathologic feature of PCMC is basophilic epithelioid cell nests in mucinous lakes.4 Rosettelike structures are seen within solid areas of the tumor. Fibrous septae separate individual collections of mucin, creating a lobulated appearance. The histopathologic differential diagnosis of EMPSGC and PCMC is broad, including basal cell carcinoma, hidradenoma, hidradenocarcinoma, apocrine adenoma, and dermal duct tumor. Positive expression of at least 1 neuroendocrine marker (ie, synaptophysin, neuron-specific enolase, chromogranin) and low-molecular cytokeratin (cytokeratin 7, CAM5.2, Ber-EP4) can aid in the diagnosis of both EMPSGC and PCMC.4 The use of p63 immunostaining is beneficial in delineating adnexal neoplasms. Adnexal tumors that stain positively with p63 are more likely to be of primary cutaneous origin, whereas lack of p63 staining usually denotes a secondary metastatic process. However, p63 staining is less reliable when distinguishing primary and metastatic mucinous neoplasms. Metastatic mucinous carcinomas often stain positive with p63, while PCMC usually stains negative despite its primary cutaneous origin, decreasing the clinical utility of p63. The tumor may be identical to metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, ovary, and pancreas. Tumor islands floating in mucin are identified in both primary cutaneous and metastatic disease to the skin.3,6 Areas of tumor necrosis, notable atypia, and perineural or lymphovascular invasion are infrequently reported in EMPSGC or PCMC, though lymphatic invasion was identified in case 5 presented herein.

A metastatic workup is warranted in all cases of PCMC, including a thorough history, review of systems, breast examination, and imaging. A workup may be considered in cases of EMPSGC depending on histologic features or clinical history.

There is uncertainty regarding the optimal management of these slow-growing yet locally destructive tumors.5 The incidence of local recurrence of PCMC after WLE with narrow margins of at least 1 cm can be as high as 30% to 40%, especially on the eyelid.4 There is no consensus on surgical care for either of these tumors.5 Because of the high recurrence rate and the predilection for the eyelid and face, MMS provides an excellent alternative to WLE for tissue preservation and meticulous margin control. We advocate for the use of the Mohs technique with permanent sectioning, which may delay the repair, but reviewing tissue with permanent fixation improves the quality and accuracy of the margin evaluation because these tumors often are infiltrative and difficult to delineate under frozen section processing. Permanent en face sectioning allows the laboratory to utilize the full array of immunohistochemical stains for these tumors, providing accurate and timely results.

Limitations to our retrospective uncontrolled study include missing or incomplete data points and short follow-up time. Additionally, there was no standardization to the margins removed with MMS or WLE because of the limited available data that comment on appropriate margins.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Kutzner H, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 11 cases with emphasis on MYB immunoexpression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:674-680.

- Navrazhina K, Petukhova T, Wildman HF, et al. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:887-889.

- Scott BL, Anyanwu CO, Vandergriff T, et al. Endocrine mucin–producing sweat gland carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1498-1500.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, et al. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2010;44:97-100.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Bulliard C, Murali R, Maloof A, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:812-816.

- Held L, Ruetten A, Kutzner H, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical and molecular analysis of 11 cases with emphasis on MYB immunoexpression. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:674-680.

- Navrazhina K, Petukhova T, Wildman HF, et al. Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma of the scalp treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4:887-889.

- Scott BL, Anyanwu CO, Vandergriff T, et al. Endocrine mucin–producing sweat gland carcinoma treated with Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2017;43:1498-1500.

- Chang S, Shim SH, Joo M, et al. A case of endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma co-existing with mucinous carcinoma: a case report. Korean J Pathol. 2010;44:97-100.

- Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-384.

- Bulliard C, Murali R, Maloof A, et al. Endocrine mucin‐producing sweat gland carcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:812-816.

Practice Points

- Endocrine mucin-producing sweat gland carcinoma and primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma are rare low-grade neoplasms thought to arise from apocrine glands that are morphologically and immunohistochemically analogous to ductal carcinoma in situ and mucinous carcinoma of the breast, respectively.

- Management involves a metastatic workup and either wide local excision with margins greater than 5 mm or Mohs micrographic surgery in anatomically sensitive areas.

Chilblain Lupus Erythematosus Presenting With Bilateral Hemorrhagic Bullae of Distal Halluces

To the Editor:

A 20-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of mildly painful, hemorrhagic bullae on the bilateral halluces of 1 month’s duration. On initial presentation the patient reported the lesions developed after wearing a new pair of tight-fitting shoes, suggesting a diagnosis of trauma-induced bullae. The patient was instructed to wear loose-fitting shoes and to follow up in 6 weeks to assess for improvement. At follow-up the bullae had resolved with residual violaceous patches on the bilateral distal halluces. He additionally developed a faint retiform erythematous patch on the left distal toe (Figure 1). The patient also had reticulate erythematous patches on the dorsal aspects of the hands extending to the forearms and legs resembling livedo reticularis. The patient was unsure if the skin lesions were triggered or worsened by cold exposure and reported that he smoked half a pack of cigarettes daily. At this time, the differential diagnosis still included trauma; however, there was concern for either embolic, thrombotic, or connective-tissue disease. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the left distal hallux demonstrated basal vacuolar interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular inflammation and deep periadnexal mucin deposition (Figure 2) consistent with lupus dermatitis.

Serologic workup revealed increased antinuclear antibody titers of 1:320 (reference range, <1:40) and anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies of 86 (reference range, <20). There was no elevation in anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, or anticardiolipin antibodies. Complement levels also were within reference range. Furthermore, the patient denied a history of Raynaud phenomenon, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, joint pain, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, arthritis, blood clots, or any other systemic symptoms. Additional evaluation by the rheumatology department did not support criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In the context of the clinical presentation, histologic findings, and serologic markers, a diagnosis of chilblain lupus erythematosus (CHLE) was made. He was counseled on sun protection and smoking cessation and declined systemic therapy citing concern for side effects. Follow-up with the dermatology and rheumatology departments was advised.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) comprises various forms of lupus, including acute cutaneous lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and chronic cutaneous lupus. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare subset of chronic CLE that first was described in 18881 and is characterized by tender violaceous papules and plaques that typically present in an acral distribution (ie, fingers, toes, nose, cheeks, ears). The skin lesions often are triggered or exacerbated by cold temperatures and dampness. As the lesions evolve, they can ulcerate, fissure, become hyperkeratotic, or result in atrophic plaques with scarring.2,3 A subset of patients also may have concurrent Raynaud phenomenon.1 Up to 20% of patients will eventually develop SLE, especially those patients with concurrent discoid lupus erythematosus, warranting close long-term follow-up.3 Serologic studies can reveal antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies, rheumatic factor, and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies.1,4 Hypergammaglobulinemia also is a common finding in patients with CHLE, affecting more than two-thirds of patients.1 Typical features of CHLE seen on histopathology include interface dermatitis, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, apoptotic keratinocytes, lichenoid tissue reaction, and increased dermal mucin.1,4

Chilblain lupus erythematosus most commonly presents sporadically; however, there is a familial form that has been previously described.5 Sporadic CHLE usually occurs in middle-aged females, in contrast to familial CHLE, which presents in early childhood.1 The pathogenesis of the sporadic form is poorly understood, but it is thought to be stimulated by vasoconstriction or microvascular injury provoked by cold exposure. Furthermore, hypergammaglobulinemia and the presence of autoantibodies may contribute to the pathogenesis by increasing blood viscosity.1 The

Several drugs including thiazides, terbinafine, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and chemotherapeutic agents have been reported to trigger CHLE.4 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been shown to precipitate CHLE.6 Of note, drug-induced CHLE usually is limited to the skin and has not been shown to progress to SLE.6 Lebeau et al4 described a patient with breast cancer and preexisting CHLE that flared while the patient received docetaxel therapy, suggesting that certain drugs may not only induce but also may aggravate CHLE.

Many of the therapies that are effective in SLE such as antimalarial agents (ie, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) often are less efficacious in treating the lesions of CHLE.1 However, these patients often can be managed successfully by physical protection from the cold environment.1 Calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine also have been implicated, as they counteract vasoconstriction, which is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of CHLE.1 Topical and systemic steroids also have been used to treat CHLE. Dapsone and pentoxifylline are other treatment modalities that have been effective in select cases of CHLE.5 Boehm and Bieber7 reported near resolution of CHLE with mycophenolate mofetil in an elderly woman with skin lesions that had been refractory to systemic steroids, antimalarial agents, azathioprine, dapsone, and pentoxifylline, suggesting that mycophenolate mofetil may be a therapeutic option for recalcitrant cases of CHLE. Local immunosuppressive agents such as tacrolimus also can be considered in treatment-refractory disease.

Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare chronic form of CLE that typically occurs sporadically but also has a familial form that has been described in several families. It most commonly is observed in middle-aged women, but we describe a case in a young man. Although CHLE typically does not respond well to traditional lupus therapies used in the management of SLE, good effects have been observed with cold avoidance, calcium channel blockers, and topical or oral steroids. For treatment-refractory cases, mycophenolate mofetil and other immunosuppressive agents have been shown to be effective.

- Hedrich CM, Fiebig B, Hauck FH, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus—a review of literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:949-954.

- Kuhn A, Lehmann P, Ruzicka T, eds. Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2005.

- Obermoser G, Sontheimer RD, Zelger B. Overview of common, rare and atypical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and histopathological correlates. Lupus. 2010;19:1050-1070.

- Lebeau S, També S, Sallam MA, et al. Docetaxel-induced relapse of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:871-874.

- Günther C, Hillebrand M, Brunk J, et al. Systemic involvement in TREX1-associated familial chilblain lupus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:179-181.

- Sifuentes Giraldo WA, Ahijón Lana M, García Villanueva MJ, et al. Chilblain lupus induced by TNF-α antagonists: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:563-568.

- Boehm I, Bieber T. Chilblain lupus erythematosus Hutchinson: successful treatment with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:235-236.

To the Editor:

A 20-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of mildly painful, hemorrhagic bullae on the bilateral halluces of 1 month’s duration. On initial presentation the patient reported the lesions developed after wearing a new pair of tight-fitting shoes, suggesting a diagnosis of trauma-induced bullae. The patient was instructed to wear loose-fitting shoes and to follow up in 6 weeks to assess for improvement. At follow-up the bullae had resolved with residual violaceous patches on the bilateral distal halluces. He additionally developed a faint retiform erythematous patch on the left distal toe (Figure 1). The patient also had reticulate erythematous patches on the dorsal aspects of the hands extending to the forearms and legs resembling livedo reticularis. The patient was unsure if the skin lesions were triggered or worsened by cold exposure and reported that he smoked half a pack of cigarettes daily. At this time, the differential diagnosis still included trauma; however, there was concern for either embolic, thrombotic, or connective-tissue disease. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the left distal hallux demonstrated basal vacuolar interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular inflammation and deep periadnexal mucin deposition (Figure 2) consistent with lupus dermatitis.

Serologic workup revealed increased antinuclear antibody titers of 1:320 (reference range, <1:40) and anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies of 86 (reference range, <20). There was no elevation in anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, or anticardiolipin antibodies. Complement levels also were within reference range. Furthermore, the patient denied a history of Raynaud phenomenon, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, joint pain, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, arthritis, blood clots, or any other systemic symptoms. Additional evaluation by the rheumatology department did not support criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In the context of the clinical presentation, histologic findings, and serologic markers, a diagnosis of chilblain lupus erythematosus (CHLE) was made. He was counseled on sun protection and smoking cessation and declined systemic therapy citing concern for side effects. Follow-up with the dermatology and rheumatology departments was advised.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) comprises various forms of lupus, including acute cutaneous lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and chronic cutaneous lupus. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare subset of chronic CLE that first was described in 18881 and is characterized by tender violaceous papules and plaques that typically present in an acral distribution (ie, fingers, toes, nose, cheeks, ears). The skin lesions often are triggered or exacerbated by cold temperatures and dampness. As the lesions evolve, they can ulcerate, fissure, become hyperkeratotic, or result in atrophic plaques with scarring.2,3 A subset of patients also may have concurrent Raynaud phenomenon.1 Up to 20% of patients will eventually develop SLE, especially those patients with concurrent discoid lupus erythematosus, warranting close long-term follow-up.3 Serologic studies can reveal antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies, rheumatic factor, and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies.1,4 Hypergammaglobulinemia also is a common finding in patients with CHLE, affecting more than two-thirds of patients.1 Typical features of CHLE seen on histopathology include interface dermatitis, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, apoptotic keratinocytes, lichenoid tissue reaction, and increased dermal mucin.1,4

Chilblain lupus erythematosus most commonly presents sporadically; however, there is a familial form that has been previously described.5 Sporadic CHLE usually occurs in middle-aged females, in contrast to familial CHLE, which presents in early childhood.1 The pathogenesis of the sporadic form is poorly understood, but it is thought to be stimulated by vasoconstriction or microvascular injury provoked by cold exposure. Furthermore, hypergammaglobulinemia and the presence of autoantibodies may contribute to the pathogenesis by increasing blood viscosity.1 The

Several drugs including thiazides, terbinafine, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and chemotherapeutic agents have been reported to trigger CHLE.4 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been shown to precipitate CHLE.6 Of note, drug-induced CHLE usually is limited to the skin and has not been shown to progress to SLE.6 Lebeau et al4 described a patient with breast cancer and preexisting CHLE that flared while the patient received docetaxel therapy, suggesting that certain drugs may not only induce but also may aggravate CHLE.

Many of the therapies that are effective in SLE such as antimalarial agents (ie, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) often are less efficacious in treating the lesions of CHLE.1 However, these patients often can be managed successfully by physical protection from the cold environment.1 Calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine also have been implicated, as they counteract vasoconstriction, which is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of CHLE.1 Topical and systemic steroids also have been used to treat CHLE. Dapsone and pentoxifylline are other treatment modalities that have been effective in select cases of CHLE.5 Boehm and Bieber7 reported near resolution of CHLE with mycophenolate mofetil in an elderly woman with skin lesions that had been refractory to systemic steroids, antimalarial agents, azathioprine, dapsone, and pentoxifylline, suggesting that mycophenolate mofetil may be a therapeutic option for recalcitrant cases of CHLE. Local immunosuppressive agents such as tacrolimus also can be considered in treatment-refractory disease.

Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare chronic form of CLE that typically occurs sporadically but also has a familial form that has been described in several families. It most commonly is observed in middle-aged women, but we describe a case in a young man. Although CHLE typically does not respond well to traditional lupus therapies used in the management of SLE, good effects have been observed with cold avoidance, calcium channel blockers, and topical or oral steroids. For treatment-refractory cases, mycophenolate mofetil and other immunosuppressive agents have been shown to be effective.

To the Editor:

A 20-year-old man with no notable medical history presented to our dermatology clinic for evaluation of mildly painful, hemorrhagic bullae on the bilateral halluces of 1 month’s duration. On initial presentation the patient reported the lesions developed after wearing a new pair of tight-fitting shoes, suggesting a diagnosis of trauma-induced bullae. The patient was instructed to wear loose-fitting shoes and to follow up in 6 weeks to assess for improvement. At follow-up the bullae had resolved with residual violaceous patches on the bilateral distal halluces. He additionally developed a faint retiform erythematous patch on the left distal toe (Figure 1). The patient also had reticulate erythematous patches on the dorsal aspects of the hands extending to the forearms and legs resembling livedo reticularis. The patient was unsure if the skin lesions were triggered or worsened by cold exposure and reported that he smoked half a pack of cigarettes daily. At this time, the differential diagnosis still included trauma; however, there was concern for either embolic, thrombotic, or connective-tissue disease. A 4-mm punch biopsy of the left distal hallux demonstrated basal vacuolar interface dermatitis with superficial and deep perivascular inflammation and deep periadnexal mucin deposition (Figure 2) consistent with lupus dermatitis.

Serologic workup revealed increased antinuclear antibody titers of 1:320 (reference range, <1:40) and anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies of 86 (reference range, <20). There was no elevation in anti–double-stranded DNA, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, or anticardiolipin antibodies. Complement levels also were within reference range. Furthermore, the patient denied a history of Raynaud phenomenon, photosensitivity, oral ulcers, joint pain, shortness of breath, pleuritic chest pain, arthritis, blood clots, or any other systemic symptoms. Additional evaluation by the rheumatology department did not support criteria for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). In the context of the clinical presentation, histologic findings, and serologic markers, a diagnosis of chilblain lupus erythematosus (CHLE) was made. He was counseled on sun protection and smoking cessation and declined systemic therapy citing concern for side effects. Follow-up with the dermatology and rheumatology departments was advised.

Cutaneous lupus erythematosus (CLE) comprises various forms of lupus, including acute cutaneous lupus, subacute cutaneous lupus, and chronic cutaneous lupus. Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare subset of chronic CLE that first was described in 18881 and is characterized by tender violaceous papules and plaques that typically present in an acral distribution (ie, fingers, toes, nose, cheeks, ears). The skin lesions often are triggered or exacerbated by cold temperatures and dampness. As the lesions evolve, they can ulcerate, fissure, become hyperkeratotic, or result in atrophic plaques with scarring.2,3 A subset of patients also may have concurrent Raynaud phenomenon.1 Up to 20% of patients will eventually develop SLE, especially those patients with concurrent discoid lupus erythematosus, warranting close long-term follow-up.3 Serologic studies can reveal antinuclear antibodies, anti-Ro/Sjögren syndrome antigen antibodies, rheumatic factor, and anti–double-stranded DNA antibodies.1,4 Hypergammaglobulinemia also is a common finding in patients with CHLE, affecting more than two-thirds of patients.1 Typical features of CHLE seen on histopathology include interface dermatitis, perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate, apoptotic keratinocytes, lichenoid tissue reaction, and increased dermal mucin.1,4

Chilblain lupus erythematosus most commonly presents sporadically; however, there is a familial form that has been previously described.5 Sporadic CHLE usually occurs in middle-aged females, in contrast to familial CHLE, which presents in early childhood.1 The pathogenesis of the sporadic form is poorly understood, but it is thought to be stimulated by vasoconstriction or microvascular injury provoked by cold exposure. Furthermore, hypergammaglobulinemia and the presence of autoantibodies may contribute to the pathogenesis by increasing blood viscosity.1 The

Several drugs including thiazides, terbinafine, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, and chemotherapeutic agents have been reported to trigger CHLE.4 Tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors have been shown to precipitate CHLE.6 Of note, drug-induced CHLE usually is limited to the skin and has not been shown to progress to SLE.6 Lebeau et al4 described a patient with breast cancer and preexisting CHLE that flared while the patient received docetaxel therapy, suggesting that certain drugs may not only induce but also may aggravate CHLE.

Many of the therapies that are effective in SLE such as antimalarial agents (ie, chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine) often are less efficacious in treating the lesions of CHLE.1 However, these patients often can be managed successfully by physical protection from the cold environment.1 Calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine also have been implicated, as they counteract vasoconstriction, which is thought to contribute to the pathogenesis of CHLE.1 Topical and systemic steroids also have been used to treat CHLE. Dapsone and pentoxifylline are other treatment modalities that have been effective in select cases of CHLE.5 Boehm and Bieber7 reported near resolution of CHLE with mycophenolate mofetil in an elderly woman with skin lesions that had been refractory to systemic steroids, antimalarial agents, azathioprine, dapsone, and pentoxifylline, suggesting that mycophenolate mofetil may be a therapeutic option for recalcitrant cases of CHLE. Local immunosuppressive agents such as tacrolimus also can be considered in treatment-refractory disease.

Chilblain lupus erythematosus is a rare chronic form of CLE that typically occurs sporadically but also has a familial form that has been described in several families. It most commonly is observed in middle-aged women, but we describe a case in a young man. Although CHLE typically does not respond well to traditional lupus therapies used in the management of SLE, good effects have been observed with cold avoidance, calcium channel blockers, and topical or oral steroids. For treatment-refractory cases, mycophenolate mofetil and other immunosuppressive agents have been shown to be effective.

- Hedrich CM, Fiebig B, Hauck FH, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus—a review of literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:949-954.

- Kuhn A, Lehmann P, Ruzicka T, eds. Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2005.

- Obermoser G, Sontheimer RD, Zelger B. Overview of common, rare and atypical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and histopathological correlates. Lupus. 2010;19:1050-1070.

- Lebeau S, També S, Sallam MA, et al. Docetaxel-induced relapse of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:871-874.

- Günther C, Hillebrand M, Brunk J, et al. Systemic involvement in TREX1-associated familial chilblain lupus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:179-181.

- Sifuentes Giraldo WA, Ahijón Lana M, García Villanueva MJ, et al. Chilblain lupus induced by TNF-α antagonists: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:563-568.

- Boehm I, Bieber T. Chilblain lupus erythematosus Hutchinson: successful treatment with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:235-236.

- Hedrich CM, Fiebig B, Hauck FH, et al. Chilblain lupus erythematosus—a review of literature. Clin Rheumatol. 2008;27:949-954.

- Kuhn A, Lehmann P, Ruzicka T, eds. Cutaneous Lupus Erythematosus. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2005.

- Obermoser G, Sontheimer RD, Zelger B. Overview of common, rare and atypical manifestations of cutaneous lupus erythematosus and histopathological correlates. Lupus. 2010;19:1050-1070.

- Lebeau S, També S, Sallam MA, et al. Docetaxel-induced relapse of subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus and chilblain lupus. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2013;11:871-874.

- Günther C, Hillebrand M, Brunk J, et al. Systemic involvement in TREX1-associated familial chilblain lupus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69:179-181.

- Sifuentes Giraldo WA, Ahijón Lana M, García Villanueva MJ, et al. Chilblain lupus induced by TNF-α antagonists: a case report and literature review. Clin Rheumatol. 2012;31:563-568.

- Boehm I, Bieber T. Chilblain lupus erythematosus Hutchinson: successful treatment with mycophenolate mofetil. Arch Dermatol. 2001;137:235-236.

Practice Points

- Up to 20% of patients with chilblain lupus erythematosus (CHLE) will develop systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), necessitating close long-term follow-up.

- Medications such as antihypertensives, antifungals, chemotherapeutic agents, and tumor necrosis factor 11α inhibitors have been reported to trigger CHLE.

- Chilblain lupus erythematosus is less responsive to traditional antimalarial agents commonly used to treat SLE.

- Management of CHLE includes physical protection from cold environments, calcium channel blockers, topical and systemic steroids, and pentoxifylline, among other treatment modalities.