User login

Comparison of Lateral Retinaculum Release and Lengthening in the Treatment of Patellofemoral Disorders

Take-Home Points

- Understanding the indications for treatment is essential.

- Identifying the superficial (oblique fibers) and deep layers (transverse fibers) of the LR is very important and can lengthen the LR by as much as 20 mm.

- Open procedures reduce the risk of hematomas and related pain.

- The goal is to obtain 1 or 2 patellar quadrants of medial and lateral patellar glide in extensino and a neutral patella.

- If the Z-plasty is combined with the MPFL reconstruction or tibial tubercle transfer, the LR is set to length after the tubercle transfer and before the MPFL reconstruction (to avoid overconstraint).

Anterior knee pain is a common clinical problem that can be challenging to correct, in large part because of multiple causative factors, including structural/anatomical, functional, alignment, and neuroperception/pain pathway factors. One difficult aspect of anatomical assessment is judging the soft-tissue balance between the medial restraints (medial patellofemoral ligament [MPFL]; medial quadriceps tendon to femoral ligament; medial patellotibial and patellomeniscal ligaments) and the lateral restraints (lateral retinaculum [LR] specifically). Both LR tightness and patellar instability can be interpreted as anterior knee pain. Differentiating these entities is one of the most difficult clinical challenges in orthopedics.

LR release (LRR) has been found to improve patellar mobility and tracking.1 In the absence of clearly defined guidelines, the procedure quickly gained in popularity because of its technical simplicity and the enticing "one tool fits all" treatment approach suggested in early reviews. Injudicious use of LRR, alone or in combination with other procedures, led to iatrogenic instability and chronic pain. LR lengthening (LRL) was introduced to address LR tightness while maintaining lateral soft-tissue integrity and avoiding some of the severe complications of LRR.2

Today, isolated use of LRR/LRL is recommended only for treatment of LR tightness and pain secondary to lateral patellar hypercompression.3 It can also be used as an adjunct treatment in the setting of patellofemoral instability. LRR/LRL should never be used as primary treatment for patellofemoral instability.

In this review of treatments for LR tightness and patellofemoral disorders, we compare the use of LRR and LRL.

Discussion

LR procedures are indicated for LR tightness, which is assessed by taking a history, performing a physical examination, and obtaining diagnostic imaging. Decisions should be based on all findings considered together and never on imaging findings alone.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should include assessment of limb alignment, patellar mobility, muscle balance, and dynamic patellar tracking.

Limb Alignment. Abnormal valgus, rotational deformities, and increased Q-angle are associated with LR tightness. Valgus alignment can be assessed on standing inspection; rotational deformities with increased hip anteversion by hip motion with the patient in the prone position (increased hip internal rotation, decreased hip external rotation); and Q-angle on weight-bearing standing examination and with the patient flexing and extending the knee while seated.

Patellar Mobility. The patellar glide and tilt tests provide the most direct evaluations of LR tightness. Medial displacement of <1 quadrant is consistent with tightness, and displacement of >3 quadrants is consistent with laxity. In full extension, the patellar glide test evaluates only the soft-tissue restraints; at 30° flexion, it also evaluates patellofemoral engagement. The patellar tilt test measures the lifting of the lateral edge of the patella. With normal elevation being 0° to 20°, lack of patellar tilt means the LR is tight, and tilt of >20° means it is loose. MPFL patency can be examined with the Lachman test; the examiner rapidly moves the patella laterally while feeling for the characteristic hard endpoint of lateral translation.

Muscle Balance. The tone, strength, and tightness of the core (abdomen, dorsal, and hip muscles) and lower extremities (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius) should be evaluated.

Dynamic Patellar Tracking. The J-sign is the course (shaped like an inverted J) that the patella takes when it is medialized into the trochlea from its laterally displaced resting position as the knee goes from full extension to flexion. The J-sign can be associated with LR tightness, trochlear dysplasia, and patella alta.

Imaging

Although we cannot provide a comprehensive review of the imaging literature, the following radiologic examinations should be used to assess the patellofemoral joint.

30° Lateral Radiograph. Increased tilt is seen when the lateral facet is not anterior to the patellar ridge. Also evaluated are trochlear anatomy, patellar height, and other factors involved in patellofemoral disorders.

30° Flexed Axial (Merchant) Radiograph. Patellar tilt, subluxation, and trochlear dysplasia are evaluated. Images obtained with progressive flexion can be very useful in verifying patellar tilt reduction. Lack of reduction during early flexion suggests LR tightness.4

Alignment Axial Radiographs (Scanogram). Valgus alignment is assessed with this full-length, standing, long-leg examination.

Computed Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Many parameters of patellar alignment have been described. Basic assessment should include evaluation of patellar tilt, angle by the line across posterior condyles and a line through the greatest patellar width (>20° indicates abnormality and LR tightness) and tibial tubercle-trochlear groove distance (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scan of the knee is used to measure this distance, and to confirm a significant amount in light of complex patellofemoral malalignment5).

Indications

Lateral compression syndrome with LR tightness is often successfully treated with isolated LRR, and results are reproducible and predictable.6 Surgical intervention for patellofemoral pain should be undertaken only after failed extensive nonoperative treatment with physical therapy and bracing/taping. Patients with LR tightness on preoperative examination, lateral patellar tilt on imaging, and normal Q-angle can obtain satisfactory results with this procedure. Patellar subluxation or dislocation history, high Q-angle (>20°), grade 3 or 4 chondral injury, and patellofemoral arthritis are associated with poorer outcomes when the procedure is performed in isolation.6International Patellofemoral Study Group members agreed that LRR/LRL is a valid treatment option when indicated, but it is rarely performed in isolation and constitutes only 1% to 2% of surgeries performed by this group of experts.7 When lateral compression syndrome progresses to arthritis, LRR/LRL can be performed with lateral patella facetectomy for maximal improvement.4 In the setting of patellofemoral instability, LRR/LRL can be combined with proximal and/or distal realignment surgery if the LR is tight. The LR is the last line of defense limiting lateral translation in the setting of an incompetent MPFL. Isolated LRR/LRL in the setting of instability further destabilizes the patella and worsens the instability. Therefore, LRR/LRL

is a poor surgical option as an isolated procedure for this condition and should be used only as an adjunct in cases of patellofemoral instability with LR tightness that does not allow the patella to be centralized into the trochlea.8 LRR/LRL can also be performed to improve patellar tracking in patellofemoral arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty.

Lateral Retinaculum Release Versus Lengthening

LRR was first described for the treatment of patellar instability in 1891.9 It was also used for the treatment of lateral patellar hypercompression syndrome associated with LR tightness that led to lateral patellar tracking, joint overload, degeneration, and anterior knee pain.10 Metcalf10 further popularized the procedure by describing a minimally invasive arthroscopic version. However, the arthroscopic technique is as aggressive as the open technique and may be performed with less control, potentially making its results more variable. As proximal and distal releases are performed from the "inside out," more capsule and muscle disruption is needed to release the more superficial layers.

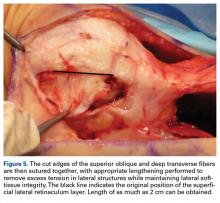

Z-plasty lengthening of the LR was described as an alternative for maintaining lateral patellar soft-tissue integrity while reducing the tension of the lateral tissue restraints.3 This is our preferred method.

Performing LRL instead of LRR avoids iatrogenic medial patellar instability, avoids overrelease and muscle injury, and improves soft-tissue balance.3 Open release or lengthening reduces inadvertent injury to the lateral superior/inferior geniculate arteries and allows direct hemostasis. Two prospective randomized studies found functional knee outcomes and return to athletic activities were improved more after LRL than LRR.11,12 These procedures had similar rates of postoperative knee stiffness, decreased muscle mass, and decreased strength. Each prospective study used an extensive LRR technique for LRR cases (various authors have recommended performing the release until the patella is perpendicular to the trochlea), which may have affected outcomes. In any case, with lengthening, the surgeon is less likely to excessively disrupt the lateral tissues.

Lateral Retinaculum Release. LRR can be openly performed by lateral parapatellar incision,1 a mini-open percutaneous technique, or arthroscopy. For these open techniques, incisions of various sizes have been used to access the LR and incise it about 1 cm lateral to the patella starting at the distal end of the vastus lateralis and extending distally until patellar tilt reduction is sufficient. If tightness in deep flexion persists, the LRR can be extended distally to the tibial tubercle. Open techniques have the advantage of sparing the joint capsule. All-arthroscopic techniques involve using electrocautery to cut through the capsule and access the LR.

Lateral Retinaculum Lengthening.

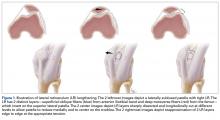

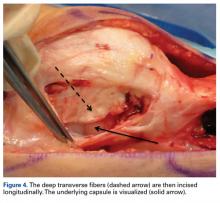

The LR is sharply divided into a superficial layer of superficial oblique fibers from the anterior iliotibial band and a deep layer of transverse fibers from the femur. For LRR, these 2 layers must be identified separate from the articular capsule.13

Complications

Complications of performing LRR/LRL to change the lateral restraint include medial patellar instability, increased lateral pain, repair failure, recurrent lateral instability, quadriceps weakness and atrophy, postoperative hemarthrosis, knee stiffness, wound complications, and thermal skin injury.7 These complications often result from poor surgical technique and too aggressive release. Although recommended patellar tilt historically has varied from 45° to 90°, the current goal is to normalize the tight soft-tissue restraints without creating secondary instability.

The most significant complication of LRR is medial patellar instability caused by muscle atrophy and loss of soft-tissue restraint.14 Medial instability can be difficult to diagnose and should be considered in any patient with patellofemoral pain, popping, or patellar instability after LRR.15 A positive medial subluxation test or medial patellar apprehension test suggests medial instability.

Medial patellar instability usually requires surgical treatment. Direct LR repair, lateral soft-tissue reconstruction, and other procedures can be used to restore lateral restraint.15 However, these are salvage techniques, and patients often remain significantly limited by pain or instability. Therefore, the LR must be carefully addressed and preferably should undergo lengthening rather than release.

1. Merchant AC, Mercer RL. Lateral release of the patella. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;(103):40-45.

2. Ceder LC, Larson RL. Z-plasty lateral retinacular release for the treatment of patellar compression syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(144):110-113.

3. Biedert R. Lateral patellar hypercompression, tilt and mild lateral subluxation. In: Biedert R, ed. Patellofemoral Disorders. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2004:161-166.

4. Hinckel BB, Arendt EA. Lateral retinaculum lengthening or release. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2015;23(2):100-106.

5. Seitlinger G, Scheurecker G, Högler R, Labey L, Innocenti B, Hofmann S. Tibial tubercle–posterior cruciate ligament distance: a new measurement to define the position of the tibial tubercle in patients with patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1119-1125.

6. Lattermann C, Toth J, Bach BR Jr. The role of lateral retinacular release in the treatment of patellar instability. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2007;15(2):57-60.

7. Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Post WR, Panni AS; International Patellofemoral Study Group. Lateral retinacular release: a survey of the International Patellofemoral Study Group. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):463-468.

8. Christoforakis J, Bull AM, Strachan RK, Shymkiw R, Senavongse W, Amis AA. Effects of lateral retinacular release on the lateral stability of the patella. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(3):273-277.

9. Pollard B. Old dislocation of patella by intra-articular operation. Lancet. 1891;(988):17-22.

10. Metcalf RW. An arthroscopic method for lateral release of subluxating or dislocating patella. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;167:9-18.

11. Pagenstert G, Wolf N, Bachmann M, et al. Open lateral patellar retinacular lengthening versus open retinacular release in lateral patellar hypercompression syndrome: a prospective double-blinded comparative study on complications and outcome. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):788-797.

12. O’Neill DB. Open lateral retinacular lengthening compared with arthroscopic release. A prospective, randomized outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(12):1759-1769.

13. Merican AM, Amis AA. Anatomy of the lateral retinaculum of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):527-534.

14. Hughston JC, Deese M. Medial subluxation of the patella as a complication of lateral retinacular release. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(4):383-388.

15. McCarthy MA, Bollier MJ. Medial patella subluxation: diagnosis and treatment. Iowa Orthop J. 2015;35:26-33.

Take-Home Points

- Understanding the indications for treatment is essential.

- Identifying the superficial (oblique fibers) and deep layers (transverse fibers) of the LR is very important and can lengthen the LR by as much as 20 mm.

- Open procedures reduce the risk of hematomas and related pain.

- The goal is to obtain 1 or 2 patellar quadrants of medial and lateral patellar glide in extensino and a neutral patella.

- If the Z-plasty is combined with the MPFL reconstruction or tibial tubercle transfer, the LR is set to length after the tubercle transfer and before the MPFL reconstruction (to avoid overconstraint).

Anterior knee pain is a common clinical problem that can be challenging to correct, in large part because of multiple causative factors, including structural/anatomical, functional, alignment, and neuroperception/pain pathway factors. One difficult aspect of anatomical assessment is judging the soft-tissue balance between the medial restraints (medial patellofemoral ligament [MPFL]; medial quadriceps tendon to femoral ligament; medial patellotibial and patellomeniscal ligaments) and the lateral restraints (lateral retinaculum [LR] specifically). Both LR tightness and patellar instability can be interpreted as anterior knee pain. Differentiating these entities is one of the most difficult clinical challenges in orthopedics.

LR release (LRR) has been found to improve patellar mobility and tracking.1 In the absence of clearly defined guidelines, the procedure quickly gained in popularity because of its technical simplicity and the enticing "one tool fits all" treatment approach suggested in early reviews. Injudicious use of LRR, alone or in combination with other procedures, led to iatrogenic instability and chronic pain. LR lengthening (LRL) was introduced to address LR tightness while maintaining lateral soft-tissue integrity and avoiding some of the severe complications of LRR.2

Today, isolated use of LRR/LRL is recommended only for treatment of LR tightness and pain secondary to lateral patellar hypercompression.3 It can also be used as an adjunct treatment in the setting of patellofemoral instability. LRR/LRL should never be used as primary treatment for patellofemoral instability.

In this review of treatments for LR tightness and patellofemoral disorders, we compare the use of LRR and LRL.

Discussion

LR procedures are indicated for LR tightness, which is assessed by taking a history, performing a physical examination, and obtaining diagnostic imaging. Decisions should be based on all findings considered together and never on imaging findings alone.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should include assessment of limb alignment, patellar mobility, muscle balance, and dynamic patellar tracking.

Limb Alignment. Abnormal valgus, rotational deformities, and increased Q-angle are associated with LR tightness. Valgus alignment can be assessed on standing inspection; rotational deformities with increased hip anteversion by hip motion with the patient in the prone position (increased hip internal rotation, decreased hip external rotation); and Q-angle on weight-bearing standing examination and with the patient flexing and extending the knee while seated.

Patellar Mobility. The patellar glide and tilt tests provide the most direct evaluations of LR tightness. Medial displacement of <1 quadrant is consistent with tightness, and displacement of >3 quadrants is consistent with laxity. In full extension, the patellar glide test evaluates only the soft-tissue restraints; at 30° flexion, it also evaluates patellofemoral engagement. The patellar tilt test measures the lifting of the lateral edge of the patella. With normal elevation being 0° to 20°, lack of patellar tilt means the LR is tight, and tilt of >20° means it is loose. MPFL patency can be examined with the Lachman test; the examiner rapidly moves the patella laterally while feeling for the characteristic hard endpoint of lateral translation.

Muscle Balance. The tone, strength, and tightness of the core (abdomen, dorsal, and hip muscles) and lower extremities (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius) should be evaluated.

Dynamic Patellar Tracking. The J-sign is the course (shaped like an inverted J) that the patella takes when it is medialized into the trochlea from its laterally displaced resting position as the knee goes from full extension to flexion. The J-sign can be associated with LR tightness, trochlear dysplasia, and patella alta.

Imaging

Although we cannot provide a comprehensive review of the imaging literature, the following radiologic examinations should be used to assess the patellofemoral joint.

30° Lateral Radiograph. Increased tilt is seen when the lateral facet is not anterior to the patellar ridge. Also evaluated are trochlear anatomy, patellar height, and other factors involved in patellofemoral disorders.

30° Flexed Axial (Merchant) Radiograph. Patellar tilt, subluxation, and trochlear dysplasia are evaluated. Images obtained with progressive flexion can be very useful in verifying patellar tilt reduction. Lack of reduction during early flexion suggests LR tightness.4

Alignment Axial Radiographs (Scanogram). Valgus alignment is assessed with this full-length, standing, long-leg examination.

Computed Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Many parameters of patellar alignment have been described. Basic assessment should include evaluation of patellar tilt, angle by the line across posterior condyles and a line through the greatest patellar width (>20° indicates abnormality and LR tightness) and tibial tubercle-trochlear groove distance (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scan of the knee is used to measure this distance, and to confirm a significant amount in light of complex patellofemoral malalignment5).

Indications

Lateral compression syndrome with LR tightness is often successfully treated with isolated LRR, and results are reproducible and predictable.6 Surgical intervention for patellofemoral pain should be undertaken only after failed extensive nonoperative treatment with physical therapy and bracing/taping. Patients with LR tightness on preoperative examination, lateral patellar tilt on imaging, and normal Q-angle can obtain satisfactory results with this procedure. Patellar subluxation or dislocation history, high Q-angle (>20°), grade 3 or 4 chondral injury, and patellofemoral arthritis are associated with poorer outcomes when the procedure is performed in isolation.6International Patellofemoral Study Group members agreed that LRR/LRL is a valid treatment option when indicated, but it is rarely performed in isolation and constitutes only 1% to 2% of surgeries performed by this group of experts.7 When lateral compression syndrome progresses to arthritis, LRR/LRL can be performed with lateral patella facetectomy for maximal improvement.4 In the setting of patellofemoral instability, LRR/LRL can be combined with proximal and/or distal realignment surgery if the LR is tight. The LR is the last line of defense limiting lateral translation in the setting of an incompetent MPFL. Isolated LRR/LRL in the setting of instability further destabilizes the patella and worsens the instability. Therefore, LRR/LRL

is a poor surgical option as an isolated procedure for this condition and should be used only as an adjunct in cases of patellofemoral instability with LR tightness that does not allow the patella to be centralized into the trochlea.8 LRR/LRL can also be performed to improve patellar tracking in patellofemoral arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty.

Lateral Retinaculum Release Versus Lengthening

LRR was first described for the treatment of patellar instability in 1891.9 It was also used for the treatment of lateral patellar hypercompression syndrome associated with LR tightness that led to lateral patellar tracking, joint overload, degeneration, and anterior knee pain.10 Metcalf10 further popularized the procedure by describing a minimally invasive arthroscopic version. However, the arthroscopic technique is as aggressive as the open technique and may be performed with less control, potentially making its results more variable. As proximal and distal releases are performed from the "inside out," more capsule and muscle disruption is needed to release the more superficial layers.

Z-plasty lengthening of the LR was described as an alternative for maintaining lateral patellar soft-tissue integrity while reducing the tension of the lateral tissue restraints.3 This is our preferred method.

Performing LRL instead of LRR avoids iatrogenic medial patellar instability, avoids overrelease and muscle injury, and improves soft-tissue balance.3 Open release or lengthening reduces inadvertent injury to the lateral superior/inferior geniculate arteries and allows direct hemostasis. Two prospective randomized studies found functional knee outcomes and return to athletic activities were improved more after LRL than LRR.11,12 These procedures had similar rates of postoperative knee stiffness, decreased muscle mass, and decreased strength. Each prospective study used an extensive LRR technique for LRR cases (various authors have recommended performing the release until the patella is perpendicular to the trochlea), which may have affected outcomes. In any case, with lengthening, the surgeon is less likely to excessively disrupt the lateral tissues.

Lateral Retinaculum Release. LRR can be openly performed by lateral parapatellar incision,1 a mini-open percutaneous technique, or arthroscopy. For these open techniques, incisions of various sizes have been used to access the LR and incise it about 1 cm lateral to the patella starting at the distal end of the vastus lateralis and extending distally until patellar tilt reduction is sufficient. If tightness in deep flexion persists, the LRR can be extended distally to the tibial tubercle. Open techniques have the advantage of sparing the joint capsule. All-arthroscopic techniques involve using electrocautery to cut through the capsule and access the LR.

Lateral Retinaculum Lengthening.

The LR is sharply divided into a superficial layer of superficial oblique fibers from the anterior iliotibial band and a deep layer of transverse fibers from the femur. For LRR, these 2 layers must be identified separate from the articular capsule.13

Complications

Complications of performing LRR/LRL to change the lateral restraint include medial patellar instability, increased lateral pain, repair failure, recurrent lateral instability, quadriceps weakness and atrophy, postoperative hemarthrosis, knee stiffness, wound complications, and thermal skin injury.7 These complications often result from poor surgical technique and too aggressive release. Although recommended patellar tilt historically has varied from 45° to 90°, the current goal is to normalize the tight soft-tissue restraints without creating secondary instability.

The most significant complication of LRR is medial patellar instability caused by muscle atrophy and loss of soft-tissue restraint.14 Medial instability can be difficult to diagnose and should be considered in any patient with patellofemoral pain, popping, or patellar instability after LRR.15 A positive medial subluxation test or medial patellar apprehension test suggests medial instability.

Medial patellar instability usually requires surgical treatment. Direct LR repair, lateral soft-tissue reconstruction, and other procedures can be used to restore lateral restraint.15 However, these are salvage techniques, and patients often remain significantly limited by pain or instability. Therefore, the LR must be carefully addressed and preferably should undergo lengthening rather than release.

Take-Home Points

- Understanding the indications for treatment is essential.

- Identifying the superficial (oblique fibers) and deep layers (transverse fibers) of the LR is very important and can lengthen the LR by as much as 20 mm.

- Open procedures reduce the risk of hematomas and related pain.

- The goal is to obtain 1 or 2 patellar quadrants of medial and lateral patellar glide in extensino and a neutral patella.

- If the Z-plasty is combined with the MPFL reconstruction or tibial tubercle transfer, the LR is set to length after the tubercle transfer and before the MPFL reconstruction (to avoid overconstraint).

Anterior knee pain is a common clinical problem that can be challenging to correct, in large part because of multiple causative factors, including structural/anatomical, functional, alignment, and neuroperception/pain pathway factors. One difficult aspect of anatomical assessment is judging the soft-tissue balance between the medial restraints (medial patellofemoral ligament [MPFL]; medial quadriceps tendon to femoral ligament; medial patellotibial and patellomeniscal ligaments) and the lateral restraints (lateral retinaculum [LR] specifically). Both LR tightness and patellar instability can be interpreted as anterior knee pain. Differentiating these entities is one of the most difficult clinical challenges in orthopedics.

LR release (LRR) has been found to improve patellar mobility and tracking.1 In the absence of clearly defined guidelines, the procedure quickly gained in popularity because of its technical simplicity and the enticing "one tool fits all" treatment approach suggested in early reviews. Injudicious use of LRR, alone or in combination with other procedures, led to iatrogenic instability and chronic pain. LR lengthening (LRL) was introduced to address LR tightness while maintaining lateral soft-tissue integrity and avoiding some of the severe complications of LRR.2

Today, isolated use of LRR/LRL is recommended only for treatment of LR tightness and pain secondary to lateral patellar hypercompression.3 It can also be used as an adjunct treatment in the setting of patellofemoral instability. LRR/LRL should never be used as primary treatment for patellofemoral instability.

In this review of treatments for LR tightness and patellofemoral disorders, we compare the use of LRR and LRL.

Discussion

LR procedures are indicated for LR tightness, which is assessed by taking a history, performing a physical examination, and obtaining diagnostic imaging. Decisions should be based on all findings considered together and never on imaging findings alone.

Physical Examination

The physical examination should include assessment of limb alignment, patellar mobility, muscle balance, and dynamic patellar tracking.

Limb Alignment. Abnormal valgus, rotational deformities, and increased Q-angle are associated with LR tightness. Valgus alignment can be assessed on standing inspection; rotational deformities with increased hip anteversion by hip motion with the patient in the prone position (increased hip internal rotation, decreased hip external rotation); and Q-angle on weight-bearing standing examination and with the patient flexing and extending the knee while seated.

Patellar Mobility. The patellar glide and tilt tests provide the most direct evaluations of LR tightness. Medial displacement of <1 quadrant is consistent with tightness, and displacement of >3 quadrants is consistent with laxity. In full extension, the patellar glide test evaluates only the soft-tissue restraints; at 30° flexion, it also evaluates patellofemoral engagement. The patellar tilt test measures the lifting of the lateral edge of the patella. With normal elevation being 0° to 20°, lack of patellar tilt means the LR is tight, and tilt of >20° means it is loose. MPFL patency can be examined with the Lachman test; the examiner rapidly moves the patella laterally while feeling for the characteristic hard endpoint of lateral translation.

Muscle Balance. The tone, strength, and tightness of the core (abdomen, dorsal, and hip muscles) and lower extremities (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius) should be evaluated.

Dynamic Patellar Tracking. The J-sign is the course (shaped like an inverted J) that the patella takes when it is medialized into the trochlea from its laterally displaced resting position as the knee goes from full extension to flexion. The J-sign can be associated with LR tightness, trochlear dysplasia, and patella alta.

Imaging

Although we cannot provide a comprehensive review of the imaging literature, the following radiologic examinations should be used to assess the patellofemoral joint.

30° Lateral Radiograph. Increased tilt is seen when the lateral facet is not anterior to the patellar ridge. Also evaluated are trochlear anatomy, patellar height, and other factors involved in patellofemoral disorders.

30° Flexed Axial (Merchant) Radiograph. Patellar tilt, subluxation, and trochlear dysplasia are evaluated. Images obtained with progressive flexion can be very useful in verifying patellar tilt reduction. Lack of reduction during early flexion suggests LR tightness.4

Alignment Axial Radiographs (Scanogram). Valgus alignment is assessed with this full-length, standing, long-leg examination.

Computed Tomography/Magnetic Resonance Imaging. Many parameters of patellar alignment have been described. Basic assessment should include evaluation of patellar tilt, angle by the line across posterior condyles and a line through the greatest patellar width (>20° indicates abnormality and LR tightness) and tibial tubercle-trochlear groove distance (computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging scan of the knee is used to measure this distance, and to confirm a significant amount in light of complex patellofemoral malalignment5).

Indications

Lateral compression syndrome with LR tightness is often successfully treated with isolated LRR, and results are reproducible and predictable.6 Surgical intervention for patellofemoral pain should be undertaken only after failed extensive nonoperative treatment with physical therapy and bracing/taping. Patients with LR tightness on preoperative examination, lateral patellar tilt on imaging, and normal Q-angle can obtain satisfactory results with this procedure. Patellar subluxation or dislocation history, high Q-angle (>20°), grade 3 or 4 chondral injury, and patellofemoral arthritis are associated with poorer outcomes when the procedure is performed in isolation.6International Patellofemoral Study Group members agreed that LRR/LRL is a valid treatment option when indicated, but it is rarely performed in isolation and constitutes only 1% to 2% of surgeries performed by this group of experts.7 When lateral compression syndrome progresses to arthritis, LRR/LRL can be performed with lateral patella facetectomy for maximal improvement.4 In the setting of patellofemoral instability, LRR/LRL can be combined with proximal and/or distal realignment surgery if the LR is tight. The LR is the last line of defense limiting lateral translation in the setting of an incompetent MPFL. Isolated LRR/LRL in the setting of instability further destabilizes the patella and worsens the instability. Therefore, LRR/LRL

is a poor surgical option as an isolated procedure for this condition and should be used only as an adjunct in cases of patellofemoral instability with LR tightness that does not allow the patella to be centralized into the trochlea.8 LRR/LRL can also be performed to improve patellar tracking in patellofemoral arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty.

Lateral Retinaculum Release Versus Lengthening

LRR was first described for the treatment of patellar instability in 1891.9 It was also used for the treatment of lateral patellar hypercompression syndrome associated with LR tightness that led to lateral patellar tracking, joint overload, degeneration, and anterior knee pain.10 Metcalf10 further popularized the procedure by describing a minimally invasive arthroscopic version. However, the arthroscopic technique is as aggressive as the open technique and may be performed with less control, potentially making its results more variable. As proximal and distal releases are performed from the "inside out," more capsule and muscle disruption is needed to release the more superficial layers.

Z-plasty lengthening of the LR was described as an alternative for maintaining lateral patellar soft-tissue integrity while reducing the tension of the lateral tissue restraints.3 This is our preferred method.

Performing LRL instead of LRR avoids iatrogenic medial patellar instability, avoids overrelease and muscle injury, and improves soft-tissue balance.3 Open release or lengthening reduces inadvertent injury to the lateral superior/inferior geniculate arteries and allows direct hemostasis. Two prospective randomized studies found functional knee outcomes and return to athletic activities were improved more after LRL than LRR.11,12 These procedures had similar rates of postoperative knee stiffness, decreased muscle mass, and decreased strength. Each prospective study used an extensive LRR technique for LRR cases (various authors have recommended performing the release until the patella is perpendicular to the trochlea), which may have affected outcomes. In any case, with lengthening, the surgeon is less likely to excessively disrupt the lateral tissues.

Lateral Retinaculum Release. LRR can be openly performed by lateral parapatellar incision,1 a mini-open percutaneous technique, or arthroscopy. For these open techniques, incisions of various sizes have been used to access the LR and incise it about 1 cm lateral to the patella starting at the distal end of the vastus lateralis and extending distally until patellar tilt reduction is sufficient. If tightness in deep flexion persists, the LRR can be extended distally to the tibial tubercle. Open techniques have the advantage of sparing the joint capsule. All-arthroscopic techniques involve using electrocautery to cut through the capsule and access the LR.

Lateral Retinaculum Lengthening.

The LR is sharply divided into a superficial layer of superficial oblique fibers from the anterior iliotibial band and a deep layer of transverse fibers from the femur. For LRR, these 2 layers must be identified separate from the articular capsule.13

Complications

Complications of performing LRR/LRL to change the lateral restraint include medial patellar instability, increased lateral pain, repair failure, recurrent lateral instability, quadriceps weakness and atrophy, postoperative hemarthrosis, knee stiffness, wound complications, and thermal skin injury.7 These complications often result from poor surgical technique and too aggressive release. Although recommended patellar tilt historically has varied from 45° to 90°, the current goal is to normalize the tight soft-tissue restraints without creating secondary instability.

The most significant complication of LRR is medial patellar instability caused by muscle atrophy and loss of soft-tissue restraint.14 Medial instability can be difficult to diagnose and should be considered in any patient with patellofemoral pain, popping, or patellar instability after LRR.15 A positive medial subluxation test or medial patellar apprehension test suggests medial instability.

Medial patellar instability usually requires surgical treatment. Direct LR repair, lateral soft-tissue reconstruction, and other procedures can be used to restore lateral restraint.15 However, these are salvage techniques, and patients often remain significantly limited by pain or instability. Therefore, the LR must be carefully addressed and preferably should undergo lengthening rather than release.

1. Merchant AC, Mercer RL. Lateral release of the patella. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;(103):40-45.

2. Ceder LC, Larson RL. Z-plasty lateral retinacular release for the treatment of patellar compression syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(144):110-113.

3. Biedert R. Lateral patellar hypercompression, tilt and mild lateral subluxation. In: Biedert R, ed. Patellofemoral Disorders. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2004:161-166.

4. Hinckel BB, Arendt EA. Lateral retinaculum lengthening or release. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2015;23(2):100-106.

5. Seitlinger G, Scheurecker G, Högler R, Labey L, Innocenti B, Hofmann S. Tibial tubercle–posterior cruciate ligament distance: a new measurement to define the position of the tibial tubercle in patients with patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1119-1125.

6. Lattermann C, Toth J, Bach BR Jr. The role of lateral retinacular release in the treatment of patellar instability. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2007;15(2):57-60.

7. Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Post WR, Panni AS; International Patellofemoral Study Group. Lateral retinacular release: a survey of the International Patellofemoral Study Group. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):463-468.

8. Christoforakis J, Bull AM, Strachan RK, Shymkiw R, Senavongse W, Amis AA. Effects of lateral retinacular release on the lateral stability of the patella. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(3):273-277.

9. Pollard B. Old dislocation of patella by intra-articular operation. Lancet. 1891;(988):17-22.

10. Metcalf RW. An arthroscopic method for lateral release of subluxating or dislocating patella. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;167:9-18.

11. Pagenstert G, Wolf N, Bachmann M, et al. Open lateral patellar retinacular lengthening versus open retinacular release in lateral patellar hypercompression syndrome: a prospective double-blinded comparative study on complications and outcome. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):788-797.

12. O’Neill DB. Open lateral retinacular lengthening compared with arthroscopic release. A prospective, randomized outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(12):1759-1769.

13. Merican AM, Amis AA. Anatomy of the lateral retinaculum of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):527-534.

14. Hughston JC, Deese M. Medial subluxation of the patella as a complication of lateral retinacular release. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(4):383-388.

15. McCarthy MA, Bollier MJ. Medial patella subluxation: diagnosis and treatment. Iowa Orthop J. 2015;35:26-33.

1. Merchant AC, Mercer RL. Lateral release of the patella. A preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1974;(103):40-45.

2. Ceder LC, Larson RL. Z-plasty lateral retinacular release for the treatment of patellar compression syndrome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1979;(144):110-113.

3. Biedert R. Lateral patellar hypercompression, tilt and mild lateral subluxation. In: Biedert R, ed. Patellofemoral Disorders. Chichester, England: Wiley; 2004:161-166.

4. Hinckel BB, Arendt EA. Lateral retinaculum lengthening or release. Oper Tech Sports Med. 2015;23(2):100-106.

5. Seitlinger G, Scheurecker G, Högler R, Labey L, Innocenti B, Hofmann S. Tibial tubercle–posterior cruciate ligament distance: a new measurement to define the position of the tibial tubercle in patients with patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(5):1119-1125.

6. Lattermann C, Toth J, Bach BR Jr. The role of lateral retinacular release in the treatment of patellar instability. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2007;15(2):57-60.

7. Fithian DC, Paxton EW, Post WR, Panni AS; International Patellofemoral Study Group. Lateral retinacular release: a survey of the International Patellofemoral Study Group. Arthroscopy. 2004;20(5):463-468.

8. Christoforakis J, Bull AM, Strachan RK, Shymkiw R, Senavongse W, Amis AA. Effects of lateral retinacular release on the lateral stability of the patella. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(3):273-277.

9. Pollard B. Old dislocation of patella by intra-articular operation. Lancet. 1891;(988):17-22.

10. Metcalf RW. An arthroscopic method for lateral release of subluxating or dislocating patella. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1982;167:9-18.

11. Pagenstert G, Wolf N, Bachmann M, et al. Open lateral patellar retinacular lengthening versus open retinacular release in lateral patellar hypercompression syndrome: a prospective double-blinded comparative study on complications and outcome. Arthroscopy. 2012;28(6):788-797.

12. O’Neill DB. Open lateral retinacular lengthening compared with arthroscopic release. A prospective, randomized outcome study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79(12):1759-1769.

13. Merican AM, Amis AA. Anatomy of the lateral retinaculum of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(4):527-534.

14. Hughston JC, Deese M. Medial subluxation of the patella as a complication of lateral retinacular release. Am J Sports Med. 1988;16(4):383-388.

15. McCarthy MA, Bollier MJ. Medial patella subluxation: diagnosis and treatment. Iowa Orthop J. 2015;35:26-33.

Cartilage Restoration in the Patellofemoral Joint

Take-Home Points

- Careful evaluation is key in attributing knee pain to patellofemoral cartilage lesions-that is, in making a "diagnosis by exclusion".

- Initial treatment is nonoperative management focused on weight loss and extensive "core-to-floor" rehabilitation.

- Optimization of anatomy and biomechanics is crucial.

- Factors important in surgical decision-making incude defect location and size, subchondral bone status, unipolar vs bipolar lesions, and previous cartilage procedure.

- The most commonly used surgical procedures-autologous chondrocyte implantation, osteochondral autograft transfer, and osteochondral allograft-have demonstrated improved intermediate-term outcomes.

Patellofemoral (PF) pain is often a component of more general anterior knee pain. One source of PF pain is chondral lesions. As these lesions are commonly seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and during arthroscopy, it is necessary to differentiate incidental and symptomatic lesions.1 In addition, the correlation between symptoms and lesion presence and severity is poor.

PF pain is multifactorial (structural lesions, malalignment, deconditioning, muscle imbalance and overuse) and can coexist with other lesions in the knee (ligament tears, meniscal injuries, and cartilage lesions in other compartments). Therefore, careful evaluation is key in attributing knee pain to PF cartilage lesions—that is, in making a "diagnosis by exclusion."

From the start, it must be appreciated that the vast majority of patients will not require surgery, and many who require surgery for pain will not require cartilage restoration. One key to success with PF patients is a good working relationship with an experienced physical therapist.

Etiology

The primary causes of PF cartilage lesions are patellar instability, chronic maltracking without instability, direct trauma, repetitive microtrauma, and idiopathic.

Patellar Instability

Patients with patellar instability often present with underlying anatomical risk factors (eg, trochlear dysplasia, increased Q-angle/tibial tubercle-trochlear groove [TT-TG] distance, patella alta, and unbalanced medial and lateral soft tissues2). These factors should be addressed before surgery.

Patellar instability can cause cartilage damage during the dislocation event or by chronic subluxation. Cartilage becomes damaged in up to 96% of patellar dislocations.3 Most commonly, the damage consists of fissuring and/or fibrillation, but chondral and osteochondral fractures can occur as well. During dislocation, the medial patella strikes the lateral aspect of the femur, and, as the knee collapses into flexion, the lateral aspect of the proximal lateral femoral condyle (weight-bearing area) can sustain damage. In the patella, typically the injury is distal-medial (occasionally crossing the median ridge). A shear lesion may involve the chondral surface or be osteochondral (Figure 1A).

Chronic Maltracking Without Instability

Chronic maltracking is usually related to anatomical abnormalities, which include the same factors that can cause patellar instability. A common combination is trochlear dysplasia, increased TT-TG or TT-posterior cruciate ligament distance, and lateral soft-tissue contracture. These are often seen in PF joints that progress to lateral PF arthritis. As lateral PF arthritis progresses, lateral soft-tissue contracture worsens, compounding symptoms of laterally based pain. With respect to cartilage repair, these joints can be treated if recognized early; however, once osteoarthritis is fully established in the joint, facetectomy or PF replacement may be necessary.

Direct Trauma

With the knee in flexion during a direct trauma over the patella (eg, fall or dashboard trauma), all zones of cartilage and subchondral bone in both patella and trochlea can be injured, leading to macrostructural damage, chondral/osteochondral fracture, or, with a subcritical force, microstructural damage and chondrocyte death, subsequently causing cartilage degeneration (cartilage may look normal initially; the matrix takes months to years to deteriorate). Direct trauma usually occurs with the knee flexed. Therefore, these lesions typically are located in the distal trochlea and superior pole of the patella.

Repetitive Microtrauma

Minor injuries, which by themselves do not immediately cause apparent chondral or osteochondral fractures, may eventually exceed the capacity of natural cartilage homeostasis and result in repetitive microtrauma. Common causes are repeated jumping (as in basketball and volleyball) and prolonged flexed-knee position (eg, what a baseball catcher experiences), which may also be associated with other lesions caused by extensor apparatus overload (eg, quadriceps tendon or patellar tendon tendinitis, and fat pad impingement syndrome).

Idiopathic

In a subset of patients with osteochondritis dissecans, the patella is the lesion site. In another subset, idiopathic lesions may be related to a genetic predisposition to osteoarthritis and may not be restricted to the PF joint. In some cases, the PF joint is the first compartment to degenerate and is the most symptomatic in a setting of truly tricompartmental disease. In these cases, treating only the PF lesion can result in functional failure, owing to disease progression in other compartments. Even mild disease in other compartments should be carefully evaluated.

History and Physical Examination

Patients often report a history of anterior knee pain that worsens with stair use, prolonged sitting, and flexed-knee activities (eg, squatting). Compared with pain alone, swelling, though not specific to cartilage disease, is more suspicious for a cartilage etiology. Identifying the cartilage defect as the sole source of pain is particularly difficult in patients with recurrent patellar instability. In these patients, pain and swelling, even between instability episodes, suggest that cartilage damage is at least a component of the symptomology.

Important diagnostic components of physical examination are gait analysis, tibiofemoral alignment, and patellar alignment in all 3 planes, both static and functional. Patella-specific measurements include medial-lateral position and quadrants of excursion, lateral tilt, and patella alta, as well as J-sign and subluxation with quadriceps contraction in extension.

It is also important to document effusion; crepitus; active and passive range of motion (spine, hips, knees); site of pain or tenderness to palpation (medial, lateral, distal, retropatellar) and whether it matches the complaints and the location of the cartilage lesion; results of the grind test (placing downward force on the patella during flexion and extension) and whether they match the flexion angle of the tenderness and the flexion angle in which the cartilage lesion has increased PF contact; ligamentous and soft-tissue stability or imbalance (tibiofemoral and patellar; apprehension test, glide test, tilt test); and muscle strength, flexibility, and atrophy of the core (abdomen, dorsal and hip muscles) and lower extremities (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius).

Imaging

Imaging should be used to evaluate both PF alignment and the cartilage lesions. For alignment, standard radiographs (weight-bearing knee sequence and axial view; full limb length when needed), computed tomography, and MRI can be used.

Meaningful evaluation requires MRI with cartilage-specific sequences, including standard spin-echo (SE) and gradient-recalled echo (GRE), fast SE, and, for cartilage morphology, T2-weighted fat suppression (FS) and 3-dimensional SE and GRE.5 For evaluation of cartilage function and metabolism, the collagen network, and proteoglycan content in the knee cartilage matrix, consideration should be given to compositional assessment techniques, such as T2 mapping, delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage, T1ρ imaging, sodium imaging, and diffusion-weighted sequences.5 Use of the latter functional sequences is still debatable, and these sequences are not widely available.

Treatment

In general, the initial approach is nonoperative management focused on weight loss and extensive core-to-floor rehabilitation, unless surgery is specifically indicated (eg, for loose body removal or osteochondral fracture reattachment). Rehabilitation focuses on achieving adequate range of motion of the spine, hips, and knees along with muscle strength and flexibility of the core (abdomen, dorsal and hip muscles) and lower limbs (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius). Rehabilitation is not defined by time but rather by development of an optimized soft-tissue envelope that decreases joint reactive forces. The full process can take 6 to 9 months, but there should be some improvement by 3 months.

Corticosteroid, hyaluronic acid,6 or platelet-rich plasma7 injections can provide temporary relief and facilitate rehabilitation in the setting of pain inhibition. As stand-alone treatment, injections are more suitable for more diffuse degenerative lesions in older and low-demand patients than for focal traumatic lesions in young and high-demand patients.

Surgery is indicated for full-thickness or nearly full-thickness lesions (International Cartilage Repair Society grade 3a or higher) >1 cm2 after failed conservative treatment.

Optimization of anatomy and biomechanics is crucial, as persistent abnormalities lead to high rates of failure of cartilage procedures, and correction of those factors results in outcomes similar to those of patients without such abnormal anatomy.8 The procedures most commonly used to improve patellar tracking or unloading in the PF compartment are lateral retinacular lengthening and TT transfer: medialization and/or distalization for correction of malalignment, and straight anteriorization or anteromedialization for unloading. These procedures can improve symptoms and function in lateral and distal patellar and trochlear lesions even without the addition of a cartilage restoration procedure.

Factors that are important in surgical decision-making include defect location and size, subchondral bone status, unipolar vs bipolar lesions, and previous cartilage procedure.

Location. The shapes of the patella and trochlea vary much more than the shapes of the condyles and plateaus. This variability complicates morphology matching, particularly with involvement of the central TG and median patellar ridge. Therefore, focal contained lesions of the patella and trochlea may be more technically amenable to cell therapy techniques than to osteochondral procedures, which require contour matching between donor and recipient

Size. Although small lesions in the femoral condyles can be considered for microfracture (MFx) or osteochondral autograft transfer (OAT), MFx is less suitable because of poor results in the PF joint, and OAT because of donor-site morbidity in the trochlea.

Subchondral bone status. When subchondral bone is compromised, such as with bone loss, cysts, or significant bone edema, the entire osteochondral unit should be treated. Here, OAT and osteochondral allograft (OCA) are the preferred treatments, depending on lesion size.

Unipolar vs bipolar lesions. Compared with unipolar lesions, bipolar lesions tend to have worse outcomes. Therefore, an associated unloading procedure (TT osteotomy) should be given special consideration. Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) appears to have better outcomes than OCA for bipolar PF lesions.9,10

Previous surgery. Although a failed cartilage procedure can negatively affect ACI outcomes, particularly in the presence of intralesional osteophytes,11 it does not affect OCA outcomes.12 Therefore, after previous MFx, OCA instead of ACI may be considered.

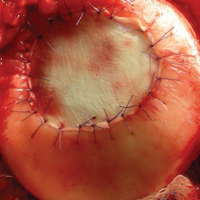

Fragment Fixation

Viable fragments from traumatic lesions (direct trauma or patellar dislocation) or osteochondritis dissecans should be repaired if possible, particularly in young patients. In a fragment that contains a substantial amount of bone, compression screws provide stable fixation. More recently, it has been recognized that fixation of predominantly cartilaginous fragments can be successful13 (Figure 1B). Débridement of soft tissue in the lesion bed and on the fragment is important in facilitating healing, as is removal of sclerotic bone.

MFx

Although MFx can have good outcomes in small contained femoral condyle lesions, in the PF joint treatment has been more challenging, and clinical outcomes have been poor (increased subchondral edema, increased effusion).14 In addition, deterioration becomes significant after 36 months. Therefore, MFx should be restricted to small (<2 cm2), well-contained trochlear defects, particularly in low-demand patients.

ACI and Matrix-Induced ACI

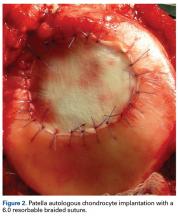

As stated, ACI (Figure 2) is suitable for PF joints because it intrinsically respects the complex anatomy.

OAT

As mentioned, donor-site morbidity may compromise final outcomes of harvest and implantation in the PF joint. Nonetheless, in carefully selected patients with small lesions that are limited to 1 facet (not including the patellar ridge or the TG) and that require only 1 plug (Figure 3), OAT can have good clinical results.16

OCA

Two techniques can be used with OCA in the PF joint. The dowel technique, in which circular plugs are implanted, is predominantly used for defects that do not cross the midline (those located in their entirety on the medial or lateral aspect of the patella or trochlea). Central defects, which can be treated with the dowel technique as well, are technically more challenging to match perfectly, because of the complex geometry of the median ridge and the TG (Figure 4).

Experimental and Emerging Technologies

Biocartilage

Biocartilage, a dehydrated, micronized allogeneic cartilage scaffold implanted with platelet-rich plasma and fibrin glue added over a contained MFx-treated defect, can be used in the patella and trochlea and has the same indications as MFx (small lesions, contained lesions). There are limited clinical studies of short- or long-term outcomes.

Fresh and Viable OCA

Fresh OCA (ProChondrix; AlloSource) and viable/cryopreserved OCA (Cartiform; Arthrex) are thin osteochondral scaffolds that contain viable chondrocytes and growth factors. They can be implanted alone or used with MFx, and are indicated for lesions measuring 1 cm2 to 3 cm2. Aside from a case report,17 there are no clinical studies on outcomes.

Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate Implantation

Bone marrow aspirate concentrate from centrifuged iliac crest–harvested aspirate containing mesenchymal stem cells with chondrogenic potential is applied under a synthetic scaffold. Indications are the same as for ACI. Medium-term follow-up studies in the PF joint have shown good results, similar to those obtained with matrix-induced ACI.18

Particulated Juvenile Allograft Cartilage

Particulated juvenile allograft cartilage (DeNovo NT Graft; Zimmer Biomet) is minced cartilage allograft (from juvenile donors) that has been cut into cubes (~1 mm3). Indications are for patellar and trochlear lesions 1 cm2 to 6 cm2. For both the trochlea and the patella, short-term outcomes have been good.19,20

Rehabilitation After Surgery

Isolated PF cartilage restoration generally does not require prolonged weight-bearing restrictions, and ambulation with the knee locked in full extension is permitted as tolerated. Concurrent TT osteotomy, however, requires protection with 4 to 6 weeks of toe-touch weight-bearing to minimize the risk of tibial fracture.

Conclusion

Comprehensive preoperative assessment is essential and should include a thorough core-to-floor physical examination as well as PF-specific imaging. Treatment of symptomatic chondral lesions in the PF joint requires specific technical and postoperative management, which differs significantly from management involving the condyles. Attending to all these details makes the outcomes of PF cartilage treatment reproducible. These outcomes may rival those of condylar treatment.

1. Curl WW, Krome J, Gordon ES, Rushing J, Smith BP, Poehling GG. Cartilage injuries: a review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy. 1997;13(4):456-460.

2. Steensen RN, Bentley JC, Trinh TQ, Backes JR, Wiltfong RE. The prevalence and combined prevalences of anatomic factors associated with recurrent patellar dislocation: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):921-927.

3. Nomura E, Inoue M. Cartilage lesions of the patella in recurrent patellar dislocation. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(2):498-502.

4. Vollnberg B, Koehlitz T, Jung T, et al. Prevalence of cartilage lesions and early osteoarthritis in patients with patellar dislocation. Eur Radiol. 2012;22(11):2347-2356.

5. Crema MD, Roemer FW, Marra MD, et al. Articular cartilage in the knee: current MR imaging techniques and applications in clinical practice and research. Radiographics. 2011;31(1):37-61.

6. Campbell KA, Erickson BJ, Saltzman BM, et al. Is local viscosupplementation injection clinically superior to other therapies in the treatment of osteoarthritis of the knee: a systematic review of overlapping meta-analyses. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(10):2036-2045.e14.

7. Saltzman BM, Jain A, Campbell KA, et al. Does the use of platelet-rich plasma at the time of surgery improve clinical outcomes in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair when compared with control cohorts? A systematic review of meta-analyses. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(5):906-918.

8. Gomoll AH, Gillogly SD, Cole BJ, et al. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in the patella: a multicenter experience. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(5):1074-1081.

9. Meric G, Gracitelli GC, Gortz S, De Young AJ, Bugbee WD. Fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation for bipolar reciprocal osteochondral lesions of the knee. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(3):709-714.

10. Peterson L, Vasiliadis HS, Brittberg M, Lindahl A. Autologous chondrocyte implantation: a long-term follow-up. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(6):1117-1124.

11. Minas T, Gomoll AH, Rosenberger R, Royce RO, Bryant T. Increased failure rate of autologous chondrocyte implantation after previous treatment with marrow stimulation techniques. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):902-908.

12. Gracitelli GC, Meric G, Briggs DT, et al. Fresh osteochondral allografts in the knee: comparison of primary transplantation versus transplantation after failure of previous subchondral marrow stimulation. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(4):885-891.

13. Anderson CN, Magnussen RA, Block JJ, Anderson AF, Spindler KP. Operative fixation of chondral loose bodies in osteochondritis dissecans in the knee: a report of 5 cases. Orthop J Sports Med. 2013;1(2):2325967113496546.

14. Kreuz PC, Steinwachs MR, Erggelet C, et al. Results after microfracture of full-thickness chondral defects in different compartments in the knee. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2006;14(11):1119-1125.

15. Vasiliadis HS, Lindahl A, Georgoulis AD, Peterson L. Malalignment and cartilage lesions in the patellofemoral joint treated with autologous chondrocyte implantation. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2011;19(3):452-457.

16. Astur DC, Arliani GG, Binz M, et al. Autologous osteochondral transplantation for treating patellar chondral injuries: evaluation, treatment, and outcomes of a two-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(10):816-823.

17. Hoffman JK, Geraghty S, Protzman NM. Articular cartilage repair using marrow simulation augmented with a viable chondral allograft: 9-month postoperative histological evaluation. Case Rep Orthop. 2015;2015:617365.

18. Gobbi A, Chaurasia S, Karnatzikos G, Nakamura N. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation versus multipotent stem cells for the treatment of large patellofemoral chondral lesions: a nonrandomized prospective trial. Cartilage. 2015;6(2):82-97.

19. Farr J, Tabet SK, Margerrison E, Cole BJ. Clinical, radiographic, and histological outcomes after cartilage repair with particulated juvenile articular cartilage: a 2-year prospective study. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(6):1417-1425.

20. Tompkins M, Hamann JC, Diduch DR, et al. Preliminary results of a novel single-stage cartilage restoration technique: particulated juvenile articular cartilage allograft for chondral defects of the patella. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(10):1661-1670.

Take-Home Points

- Careful evaluation is key in attributing knee pain to patellofemoral cartilage lesions-that is, in making a "diagnosis by exclusion".

- Initial treatment is nonoperative management focused on weight loss and extensive "core-to-floor" rehabilitation.

- Optimization of anatomy and biomechanics is crucial.

- Factors important in surgical decision-making incude defect location and size, subchondral bone status, unipolar vs bipolar lesions, and previous cartilage procedure.

- The most commonly used surgical procedures-autologous chondrocyte implantation, osteochondral autograft transfer, and osteochondral allograft-have demonstrated improved intermediate-term outcomes.

Patellofemoral (PF) pain is often a component of more general anterior knee pain. One source of PF pain is chondral lesions. As these lesions are commonly seen on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and during arthroscopy, it is necessary to differentiate incidental and symptomatic lesions.1 In addition, the correlation between symptoms and lesion presence and severity is poor.

PF pain is multifactorial (structural lesions, malalignment, deconditioning, muscle imbalance and overuse) and can coexist with other lesions in the knee (ligament tears, meniscal injuries, and cartilage lesions in other compartments). Therefore, careful evaluation is key in attributing knee pain to PF cartilage lesions—that is, in making a "diagnosis by exclusion."

From the start, it must be appreciated that the vast majority of patients will not require surgery, and many who require surgery for pain will not require cartilage restoration. One key to success with PF patients is a good working relationship with an experienced physical therapist.

Etiology

The primary causes of PF cartilage lesions are patellar instability, chronic maltracking without instability, direct trauma, repetitive microtrauma, and idiopathic.

Patellar Instability

Patients with patellar instability often present with underlying anatomical risk factors (eg, trochlear dysplasia, increased Q-angle/tibial tubercle-trochlear groove [TT-TG] distance, patella alta, and unbalanced medial and lateral soft tissues2). These factors should be addressed before surgery.

Patellar instability can cause cartilage damage during the dislocation event or by chronic subluxation. Cartilage becomes damaged in up to 96% of patellar dislocations.3 Most commonly, the damage consists of fissuring and/or fibrillation, but chondral and osteochondral fractures can occur as well. During dislocation, the medial patella strikes the lateral aspect of the femur, and, as the knee collapses into flexion, the lateral aspect of the proximal lateral femoral condyle (weight-bearing area) can sustain damage. In the patella, typically the injury is distal-medial (occasionally crossing the median ridge). A shear lesion may involve the chondral surface or be osteochondral (Figure 1A).

Chronic Maltracking Without Instability

Chronic maltracking is usually related to anatomical abnormalities, which include the same factors that can cause patellar instability. A common combination is trochlear dysplasia, increased TT-TG or TT-posterior cruciate ligament distance, and lateral soft-tissue contracture. These are often seen in PF joints that progress to lateral PF arthritis. As lateral PF arthritis progresses, lateral soft-tissue contracture worsens, compounding symptoms of laterally based pain. With respect to cartilage repair, these joints can be treated if recognized early; however, once osteoarthritis is fully established in the joint, facetectomy or PF replacement may be necessary.

Direct Trauma

With the knee in flexion during a direct trauma over the patella (eg, fall or dashboard trauma), all zones of cartilage and subchondral bone in both patella and trochlea can be injured, leading to macrostructural damage, chondral/osteochondral fracture, or, with a subcritical force, microstructural damage and chondrocyte death, subsequently causing cartilage degeneration (cartilage may look normal initially; the matrix takes months to years to deteriorate). Direct trauma usually occurs with the knee flexed. Therefore, these lesions typically are located in the distal trochlea and superior pole of the patella.

Repetitive Microtrauma

Minor injuries, which by themselves do not immediately cause apparent chondral or osteochondral fractures, may eventually exceed the capacity of natural cartilage homeostasis and result in repetitive microtrauma. Common causes are repeated jumping (as in basketball and volleyball) and prolonged flexed-knee position (eg, what a baseball catcher experiences), which may also be associated with other lesions caused by extensor apparatus overload (eg, quadriceps tendon or patellar tendon tendinitis, and fat pad impingement syndrome).

Idiopathic

In a subset of patients with osteochondritis dissecans, the patella is the lesion site. In another subset, idiopathic lesions may be related to a genetic predisposition to osteoarthritis and may not be restricted to the PF joint. In some cases, the PF joint is the first compartment to degenerate and is the most symptomatic in a setting of truly tricompartmental disease. In these cases, treating only the PF lesion can result in functional failure, owing to disease progression in other compartments. Even mild disease in other compartments should be carefully evaluated.

History and Physical Examination

Patients often report a history of anterior knee pain that worsens with stair use, prolonged sitting, and flexed-knee activities (eg, squatting). Compared with pain alone, swelling, though not specific to cartilage disease, is more suspicious for a cartilage etiology. Identifying the cartilage defect as the sole source of pain is particularly difficult in patients with recurrent patellar instability. In these patients, pain and swelling, even between instability episodes, suggest that cartilage damage is at least a component of the symptomology.

Important diagnostic components of physical examination are gait analysis, tibiofemoral alignment, and patellar alignment in all 3 planes, both static and functional. Patella-specific measurements include medial-lateral position and quadrants of excursion, lateral tilt, and patella alta, as well as J-sign and subluxation with quadriceps contraction in extension.

It is also important to document effusion; crepitus; active and passive range of motion (spine, hips, knees); site of pain or tenderness to palpation (medial, lateral, distal, retropatellar) and whether it matches the complaints and the location of the cartilage lesion; results of the grind test (placing downward force on the patella during flexion and extension) and whether they match the flexion angle of the tenderness and the flexion angle in which the cartilage lesion has increased PF contact; ligamentous and soft-tissue stability or imbalance (tibiofemoral and patellar; apprehension test, glide test, tilt test); and muscle strength, flexibility, and atrophy of the core (abdomen, dorsal and hip muscles) and lower extremities (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius).

Imaging

Imaging should be used to evaluate both PF alignment and the cartilage lesions. For alignment, standard radiographs (weight-bearing knee sequence and axial view; full limb length when needed), computed tomography, and MRI can be used.

Meaningful evaluation requires MRI with cartilage-specific sequences, including standard spin-echo (SE) and gradient-recalled echo (GRE), fast SE, and, for cartilage morphology, T2-weighted fat suppression (FS) and 3-dimensional SE and GRE.5 For evaluation of cartilage function and metabolism, the collagen network, and proteoglycan content in the knee cartilage matrix, consideration should be given to compositional assessment techniques, such as T2 mapping, delayed gadolinium-enhanced MRI of cartilage, T1ρ imaging, sodium imaging, and diffusion-weighted sequences.5 Use of the latter functional sequences is still debatable, and these sequences are not widely available.

Treatment

In general, the initial approach is nonoperative management focused on weight loss and extensive core-to-floor rehabilitation, unless surgery is specifically indicated (eg, for loose body removal or osteochondral fracture reattachment). Rehabilitation focuses on achieving adequate range of motion of the spine, hips, and knees along with muscle strength and flexibility of the core (abdomen, dorsal and hip muscles) and lower limbs (quadriceps, hamstrings, gastrocnemius). Rehabilitation is not defined by time but rather by development of an optimized soft-tissue envelope that decreases joint reactive forces. The full process can take 6 to 9 months, but there should be some improvement by 3 months.

Corticosteroid, hyaluronic acid,6 or platelet-rich plasma7 injections can provide temporary relief and facilitate rehabilitation in the setting of pain inhibition. As stand-alone treatment, injections are more suitable for more diffuse degenerative lesions in older and low-demand patients than for focal traumatic lesions in young and high-demand patients.

Surgery is indicated for full-thickness or nearly full-thickness lesions (International Cartilage Repair Society grade 3a or higher) >1 cm2 after failed conservative treatment.

Optimization of anatomy and biomechanics is crucial, as persistent abnormalities lead to high rates of failure of cartilage procedures, and correction of those factors results in outcomes similar to those of patients without such abnormal anatomy.8 The procedures most commonly used to improve patellar tracking or unloading in the PF compartment are lateral retinacular lengthening and TT transfer: medialization and/or distalization for correction of malalignment, and straight anteriorization or anteromedialization for unloading. These procedures can improve symptoms and function in lateral and distal patellar and trochlear lesions even without the addition of a cartilage restoration procedure.

Factors that are important in surgical decision-making include defect location and size, subchondral bone status, unipolar vs bipolar lesions, and previous cartilage procedure.

Location. The shapes of the patella and trochlea vary much more than the shapes of the condyles and plateaus. This variability complicates morphology matching, particularly with involvement of the central TG and median patellar ridge. Therefore, focal contained lesions of the patella and trochlea may be more technically amenable to cell therapy techniques than to osteochondral procedures, which require contour matching between donor and recipient

Size. Although small lesions in the femoral condyles can be considered for microfracture (MFx) or osteochondral autograft transfer (OAT), MFx is less suitable because of poor results in the PF joint, and OAT because of donor-site morbidity in the trochlea.

Subchondral bone status. When subchondral bone is compromised, such as with bone loss, cysts, or significant bone edema, the entire osteochondral unit should be treated. Here, OAT and osteochondral allograft (OCA) are the preferred treatments, depending on lesion size.

Unipolar vs bipolar lesions. Compared with unipolar lesions, bipolar lesions tend to have worse outcomes. Therefore, an associated unloading procedure (TT osteotomy) should be given special consideration. Autologous chondrocyte implantation (ACI) appears to have better outcomes than OCA for bipolar PF lesions.9,10

Previous surgery. Although a failed cartilage procedure can negatively affect ACI outcomes, particularly in the presence of intralesional osteophytes,11 it does not affect OCA outcomes.12 Therefore, after previous MFx, OCA instead of ACI may be considered.

Fragment Fixation

Viable fragments from traumatic lesions (direct trauma or patellar dislocation) or osteochondritis dissecans should be repaired if possible, particularly in young patients. In a fragment that contains a substantial amount of bone, compression screws provide stable fixation. More recently, it has been recognized that fixation of predominantly cartilaginous fragments can be successful13 (Figure 1B). Débridement of soft tissue in the lesion bed and on the fragment is important in facilitating healing, as is removal of sclerotic bone.

MFx

Although MFx can have good outcomes in small contained femoral condyle lesions, in the PF joint treatment has been more challenging, and clinical outcomes have been poor (increased subchondral edema, increased effusion).14 In addition, deterioration becomes significant after 36 months. Therefore, MFx should be restricted to small (<2 cm2), well-contained trochlear defects, particularly in low-demand patients.

ACI and Matrix-Induced ACI

As stated, ACI (Figure 2) is suitable for PF joints because it intrinsically respects the complex anatomy.

OAT

As mentioned, donor-site morbidity may compromise final outcomes of harvest and implantation in the PF joint. Nonetheless, in carefully selected patients with small lesions that are limited to 1 facet (not including the patellar ridge or the TG) and that require only 1 plug (Figure 3), OAT can have good clinical results.16

OCA

Two techniques can be used with OCA in the PF joint. The dowel technique, in which circular plugs are implanted, is predominantly used for defects that do not cross the midline (those located in their entirety on the medial or lateral aspect of the patella or trochlea). Central defects, which can be treated with the dowel technique as well, are technically more challenging to match perfectly, because of the complex geometry of the median ridge and the TG (Figure 4).

Experimental and Emerging Technologies

Biocartilage

Biocartilage, a dehydrated, micronized allogeneic cartilage scaffold implanted with platelet-rich plasma and fibrin glue added over a contained MFx-treated defect, can be used in the patella and trochlea and has the same indications as MFx (small lesions, contained lesions). There are limited clinical studies of short- or long-term outcomes.

Fresh and Viable OCA

Fresh OCA (ProChondrix; AlloSource) and viable/cryopreserved OCA (Cartiform; Arthrex) are thin osteochondral scaffolds that contain viable chondrocytes and growth factors. They can be implanted alone or used with MFx, and are indicated for lesions measuring 1 cm2 to 3 cm2. Aside from a case report,17 there are no clinical studies on outcomes.

Bone Marrow Aspirate Concentrate Implantation

Bone marrow aspirate concentrate from centrifuged iliac crest–harvested aspirate containing mesenchymal stem cells with chondrogenic potential is applied under a synthetic scaffold. Indications are the same as for ACI. Medium-term follow-up studies in the PF joint have shown good results, similar to those obtained with matrix-induced ACI.18

Particulated Juvenile Allograft Cartilage

Particulated juvenile allograft cartilage (DeNovo NT Graft; Zimmer Biomet) is minced cartilage allograft (from juvenile donors) that has been cut into cubes (~1 mm3). Indications are for patellar and trochlear lesions 1 cm2 to 6 cm2. For both the trochlea and the patella, short-term outcomes have been good.19,20

Rehabilitation After Surgery