User login

The value proposition comes home: The Jack A. Vennes, M.D. and Stephen E. Silvis, M.D. Honorary Lecture

Value in health care is often defined as “health outcomes achieved per dollar spent,” or “outcomes/costs.” Value encompasses efficiency, but is primarily results oriented and not based on volume. For purposes of comparison and assessment, value assessments apply to patient- and condition-specific episodes of care.

As the dominant driver of value-based reimbursement (VBR), the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, has defined a payment taxonomy for coming years based upon the degree of linkage between quality and reimbursement (JAMA 2014;311:1967-8). Four categories of reimbursement extend from traditional fee for service (FFS; Category 1) to FFS with significant reliance on quality measures and outcome (Cat. 2), entirely population-based models with payments stimulated by delivery of care (Cat. 3), and payment based entirely on capitated coverage of individuals over time (Cat. 4).

Category 2 reimbursement for physicians is largely based upon the Physicians Quality Reporting System (PQRS) with Value-Based Payment Modifiers (VBPM). Incentives for participation in PQRS ended in 2014. For select groups of more than 100 physicians, 2015 payments will be based on 2013 PQRS submissions, with a 1% cut for groups that didn’t submit data in 2013. For all physicians, failure to participate in 2015 will result in a downward adjustment of 2% in 2017. Participation will generate bonuses or penalties of 1%-4% in 2017, based on group size, claims-based cost data, and submission of PQRS quality data, via one of three mechanisms. The most attractive option for many groups will be submission of data for 50% of applicable patients via a Qualified Clinical Data Registry, such as the ASGE & ACG’s GI Quality Improvement Consortium (GIQUIC) or the AGA’s Digestive Health Registry (DHR).

Category 3 in the CMS payment taxonomy triggers reimbursement by delivery of care, but links it to episodes of care or to population management, with varied mechanisms for providers to share in the potential benefits and risks of cost extremes. Programs include Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), medical homes for specified conditions, and shared savings for comprehensive primary care and end-stage renal disease. Presently, most employ a modest potential upside in reimbursement for savings but only limited downside risk. In 2015, ACOs cover about 23 million lives, or 7% of the population of the United States. Estimates suggest coverage of 72 million (22%) by 2020 (Leavitt Partners, Salt Lake, 2015).

In Category 4 of the CMS taxonomy, the Next Generation ACO Model drops all links between reimbursement and actual delivery of care, in favor of reimbursement for the assumption of care of individuals over time frames greater than 1 year, with greater participation in savings and risk. Several inducements and tools are included to enhance participation and the management of care, including: 1) reward to beneficiaries for participation, 2) reimbursement for skilled nursing care without prior hospitalization, and 3) expanded coverage for tele-health and home services. CMS aims to increase Categories 3 (alternative FFS) and 4 (population-based payment models) to 50% of covered individuals by 2018.

VBR by nongovernmental payers lags behind that of federal and state programs. CMS is currently testing more than 20 models for care and reimbursement, with aims to pull private payers into VBR and the final common pathway of management of populations while conserving health care resources (JAMA 2014;311:1967-8).

For gastroenterology, VBR will require practice redesign, with the expectation that physicians will focus their care toward their maximal level of licensure and privileging, while enabling employed advanced practice R.N.’s (certified nurse practitioner, or CNP) and physician assistants to do the same (Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:1584-6 ).

This trend is already well established in many environments. Redesign is also stimulating consolidation of practices to better enable contracts for population management by the group. A second development will be increasing use of risk-bearing contracts for episodes of care, particularly for colorectal cancer surveillance and liver transplantation. Specialty medical homes, as opposed to primary care medical homes, will grow for care of inflammatory bowel disease and perhaps for chronic liver disease patients. Success with these initiatives, with both preservation of adequate reimbursement and appropriate constraint in delivery of care, will require extensive reliance on big data for demonstration of quality and patient engagement for optimizing the frequency and intensity of care.

Dr. Petersen is professor of medicine, Mayo Graduate School of Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn. He has no conflicts of interest. His comments were made during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Value in health care is often defined as “health outcomes achieved per dollar spent,” or “outcomes/costs.” Value encompasses efficiency, but is primarily results oriented and not based on volume. For purposes of comparison and assessment, value assessments apply to patient- and condition-specific episodes of care.

As the dominant driver of value-based reimbursement (VBR), the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, has defined a payment taxonomy for coming years based upon the degree of linkage between quality and reimbursement (JAMA 2014;311:1967-8). Four categories of reimbursement extend from traditional fee for service (FFS; Category 1) to FFS with significant reliance on quality measures and outcome (Cat. 2), entirely population-based models with payments stimulated by delivery of care (Cat. 3), and payment based entirely on capitated coverage of individuals over time (Cat. 4).

Category 2 reimbursement for physicians is largely based upon the Physicians Quality Reporting System (PQRS) with Value-Based Payment Modifiers (VBPM). Incentives for participation in PQRS ended in 2014. For select groups of more than 100 physicians, 2015 payments will be based on 2013 PQRS submissions, with a 1% cut for groups that didn’t submit data in 2013. For all physicians, failure to participate in 2015 will result in a downward adjustment of 2% in 2017. Participation will generate bonuses or penalties of 1%-4% in 2017, based on group size, claims-based cost data, and submission of PQRS quality data, via one of three mechanisms. The most attractive option for many groups will be submission of data for 50% of applicable patients via a Qualified Clinical Data Registry, such as the ASGE & ACG’s GI Quality Improvement Consortium (GIQUIC) or the AGA’s Digestive Health Registry (DHR).

Category 3 in the CMS payment taxonomy triggers reimbursement by delivery of care, but links it to episodes of care or to population management, with varied mechanisms for providers to share in the potential benefits and risks of cost extremes. Programs include Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), medical homes for specified conditions, and shared savings for comprehensive primary care and end-stage renal disease. Presently, most employ a modest potential upside in reimbursement for savings but only limited downside risk. In 2015, ACOs cover about 23 million lives, or 7% of the population of the United States. Estimates suggest coverage of 72 million (22%) by 2020 (Leavitt Partners, Salt Lake, 2015).

In Category 4 of the CMS taxonomy, the Next Generation ACO Model drops all links between reimbursement and actual delivery of care, in favor of reimbursement for the assumption of care of individuals over time frames greater than 1 year, with greater participation in savings and risk. Several inducements and tools are included to enhance participation and the management of care, including: 1) reward to beneficiaries for participation, 2) reimbursement for skilled nursing care without prior hospitalization, and 3) expanded coverage for tele-health and home services. CMS aims to increase Categories 3 (alternative FFS) and 4 (population-based payment models) to 50% of covered individuals by 2018.

VBR by nongovernmental payers lags behind that of federal and state programs. CMS is currently testing more than 20 models for care and reimbursement, with aims to pull private payers into VBR and the final common pathway of management of populations while conserving health care resources (JAMA 2014;311:1967-8).

For gastroenterology, VBR will require practice redesign, with the expectation that physicians will focus their care toward their maximal level of licensure and privileging, while enabling employed advanced practice R.N.’s (certified nurse practitioner, or CNP) and physician assistants to do the same (Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:1584-6 ).

This trend is already well established in many environments. Redesign is also stimulating consolidation of practices to better enable contracts for population management by the group. A second development will be increasing use of risk-bearing contracts for episodes of care, particularly for colorectal cancer surveillance and liver transplantation. Specialty medical homes, as opposed to primary care medical homes, will grow for care of inflammatory bowel disease and perhaps for chronic liver disease patients. Success with these initiatives, with both preservation of adequate reimbursement and appropriate constraint in delivery of care, will require extensive reliance on big data for demonstration of quality and patient engagement for optimizing the frequency and intensity of care.

Dr. Petersen is professor of medicine, Mayo Graduate School of Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn. He has no conflicts of interest. His comments were made during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Value in health care is often defined as “health outcomes achieved per dollar spent,” or “outcomes/costs.” Value encompasses efficiency, but is primarily results oriented and not based on volume. For purposes of comparison and assessment, value assessments apply to patient- and condition-specific episodes of care.

As the dominant driver of value-based reimbursement (VBR), the Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services, has defined a payment taxonomy for coming years based upon the degree of linkage between quality and reimbursement (JAMA 2014;311:1967-8). Four categories of reimbursement extend from traditional fee for service (FFS; Category 1) to FFS with significant reliance on quality measures and outcome (Cat. 2), entirely population-based models with payments stimulated by delivery of care (Cat. 3), and payment based entirely on capitated coverage of individuals over time (Cat. 4).

Category 2 reimbursement for physicians is largely based upon the Physicians Quality Reporting System (PQRS) with Value-Based Payment Modifiers (VBPM). Incentives for participation in PQRS ended in 2014. For select groups of more than 100 physicians, 2015 payments will be based on 2013 PQRS submissions, with a 1% cut for groups that didn’t submit data in 2013. For all physicians, failure to participate in 2015 will result in a downward adjustment of 2% in 2017. Participation will generate bonuses or penalties of 1%-4% in 2017, based on group size, claims-based cost data, and submission of PQRS quality data, via one of three mechanisms. The most attractive option for many groups will be submission of data for 50% of applicable patients via a Qualified Clinical Data Registry, such as the ASGE & ACG’s GI Quality Improvement Consortium (GIQUIC) or the AGA’s Digestive Health Registry (DHR).

Category 3 in the CMS payment taxonomy triggers reimbursement by delivery of care, but links it to episodes of care or to population management, with varied mechanisms for providers to share in the potential benefits and risks of cost extremes. Programs include Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), medical homes for specified conditions, and shared savings for comprehensive primary care and end-stage renal disease. Presently, most employ a modest potential upside in reimbursement for savings but only limited downside risk. In 2015, ACOs cover about 23 million lives, or 7% of the population of the United States. Estimates suggest coverage of 72 million (22%) by 2020 (Leavitt Partners, Salt Lake, 2015).

In Category 4 of the CMS taxonomy, the Next Generation ACO Model drops all links between reimbursement and actual delivery of care, in favor of reimbursement for the assumption of care of individuals over time frames greater than 1 year, with greater participation in savings and risk. Several inducements and tools are included to enhance participation and the management of care, including: 1) reward to beneficiaries for participation, 2) reimbursement for skilled nursing care without prior hospitalization, and 3) expanded coverage for tele-health and home services. CMS aims to increase Categories 3 (alternative FFS) and 4 (population-based payment models) to 50% of covered individuals by 2018.

VBR by nongovernmental payers lags behind that of federal and state programs. CMS is currently testing more than 20 models for care and reimbursement, with aims to pull private payers into VBR and the final common pathway of management of populations while conserving health care resources (JAMA 2014;311:1967-8).

For gastroenterology, VBR will require practice redesign, with the expectation that physicians will focus their care toward their maximal level of licensure and privileging, while enabling employed advanced practice R.N.’s (certified nurse practitioner, or CNP) and physician assistants to do the same (Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;12:1584-6 ).

This trend is already well established in many environments. Redesign is also stimulating consolidation of practices to better enable contracts for population management by the group. A second development will be increasing use of risk-bearing contracts for episodes of care, particularly for colorectal cancer surveillance and liver transplantation. Specialty medical homes, as opposed to primary care medical homes, will grow for care of inflammatory bowel disease and perhaps for chronic liver disease patients. Success with these initiatives, with both preservation of adequate reimbursement and appropriate constraint in delivery of care, will require extensive reliance on big data for demonstration of quality and patient engagement for optimizing the frequency and intensity of care.

Dr. Petersen is professor of medicine, Mayo Graduate School of Medicine, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester, Minn. He has no conflicts of interest. His comments were made during the ASGE and AGA joint Presidential Plenary at the annual Digestive Disease Week.

Quality Improvement for the Ambulatory Surgery Center

Quality measurement and performance improvement now are accepted uniformly as key strategies and responsibilities in the delivery of health care,1 including in the management of gastrointestinal endoscopic services. Numerous metrics for quality performance by endoscopists have been adopted in recent years2,3,4,5,6 and now are being updated for 2014. Unit-specific measures pertaining to customer care, safety and infection control, communication and continuity of care, efficiency, and procedure-specific unit factors also are under development by gastrointestinal and surgical societies at this time. Until recently, the mandates and inducements for assessing and improving quality from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, accreditation organizations, and state health departments have been very generic, but measures adopted for 2014 and beyond incorporate greater numbers of endoscopy-specific expectations. In contrast, private payers have been slow to delineate quality-based performance expectations or thresholds for reimbursement. Beyond regulatory requirements, additional issues warrant focused attention to maintain the quality of care delivery. In this article, I address quality improvement principles for ambulatory endoscopy centers.

A number of metrics commonly are used for tracking the financial health of endoscopy centers, including physician-, unit-, and practice-specific costs and revenues prorated to procedural volume, space, or unit of time. Similarly, the high-quality facility is also dependent on recruitment and care of a cohesive team of physicians, nurses, and supporting personnel. This is an ongoing task that requires specific intent and planning. Although benchmarks for personnel management and financial performance commonly are used, they are both beyond the scope of this article.

Quality measurement concepts

Quality improvement efforts are based on the principle that performance can be measured and compared with optimal performance to identify needs for improvement (gaps) so that leaders then can alter structures or processes to improve health outcomes for patients. Performance on a given parameter (commonly termed a metric, measure, or indicator) is expressed as a ratio between a numerator, representing the incidence of correct performance, and a denominator, representing the opportunities for correct performance. To enable uniform data collection and interpretation, measures should be defined formally in advance of improvement efforts. Measures used for regulatory or reimbursement purposes are rigidly standardized and often use cumbersome administrative codes for claims-based reporting, but those identified for submission via registries, or for local improvement efforts, can be stated more simply using clinical terminology.

Optimal metrics should correlate with pertinent clinical outcomes and be evidence based, reproducible, feasible to collect, and amenable to improvement. Measures typically are identified by the type of performance assessed: structural measures address features of the environment of care (such as training, staffing, facilities, and policies); process measures address performance in the delivery of care (routine use of antibiotics in cirrhotic patients admitted with gastrointestinal bleeding, use of appropriate intervals for screening and surveillance colonoscopy); and outcome measures address the results of care from the patient’s perspective (resolution of infection, occurrence of interval cancer, and so forth).

Requirements for successful quality improvement efforts

The requirements for effective quality improvement initiatives in an ambulatory endoscopy center include the following: (1) recognition of the need for improvement; (2) motivation, leadership, and coherent advocacy for improvement from the unit’s owners, partners, and management; (3) clear definition of the gaps or shortcomings in performance and their contributing factors; (4) availability of timely and accurate data; and (5) a process for achieving the desired change.7

Challenges to quality endeavors on a local level include insufficient awareness, willingness, knowledge base in expectations and solutions, improvement expertise, time, and financial resources.

Significant investments in infrastructure, staff time, and expertise are required for larger improvement efforts and fulfilling national expectations for performance and data submission. For short-term ad hoc improvement projects, manual data tracking and display typically are sufficient. Automated data accrual is helpful for larger settings, ongoing tracking of performance, and serial submission of data for benchmarking and regulatory or reimbursement purposes. The repetitive nature of gastrointestinal endoscopy simplifies uniform documentation and data accrual via standardized electronic report generators. CMS-qualified report generators and electronic health records are now becoming essential business tools.

In small ambulatory endoscopy centers, quality oversight may be shared by all partners or a managing partner and administrator. In large endoscopy facilities, quality improvement may be managed primarily by a nonphysician manager or specialist. Adoption of electronic systems and submission of quality data requires expertise in information technology and CMS coding and billing. Quality monitoring and improvement efforts often benefit from skills in project management, statistical assessment, and process control charting. Many of the major skills involved can be contracted out or acquired with purchased systems, but some degree of on-site employed expertise should be considered a modern cost of practice, despite a lack of funding to meet the evolving mandates.

Recognizing and prioritizing improvement opportunities

Every facility has opportunities for improvement in safety, efficiency, clinical outcomes, cost, or service. However, the capacity to undertake quality improvement initiatives usually is constrained, therefore departments must prioritize their efforts. Top priority should be given to the following: (1) gaps in care that pose a direct risk to patient safety or procedural outcomes (such as suboptimal processes or performance in preprocedure and postprocedure management of anticoagulants, antibiotics, hypoglycemic agents, and other medications; intraprocedural sedation practices; endoscope reprocessing; and major lapses in endoscopists’ procedural safety or performance); (2) measures required to ensure full reimbursement, such as licensure, deemed status, and other measures stipulated by CMS and accreditation organizations; (3) glaring issues related to patient dissatisfaction; and (4) quality measures promulgated by national and international organizations. Additional quality needs can be identified by attention to near-miss, never, or sentinel events (all of which warrant investigation for structural or process failures), patient complaints, and repeated mention on patient, employee, or referring physician questionnaires. Units must be aware of health system, state, and federal requirements for reporting (for example, wrong site of surgery) and implement processes to comply with these regulations.

Most well-managed departments already have addressed basic quality issues, allowing them to focus on other less glaring gaps in performance, including those unique to their specific environment or patient population. One useful practice for identifying improvement opportunities is to perform an assessment of lapses and bottlenecks in the sequential steps in care, from the referral process to scheduling, preprocedure exchange of information and patient guidance, preparation, check-in, procedure performance, recovery, dismissal process and guidance, and subsequent communication of results (called value mapping in Lean terminology). Ancillary aspects of care that tie into this linear process include periprocedural management of families, supplies, medications, pathology samples, procedural results, and so forth.

Quality metrics for endoscopy vary in their applicability to entire units vs. individual endoscopists and/or patients.8 Structural measures pertaining to the facility, personnel management, policies, and procedures are intended for application on the unit level; indeed, many are delineated in the CMS’s “Conditions for Participation” and, hence, are subject to scrutiny during accreditation surveys. The United Kingdom’s National Health Service uses a global rating scale (GRS)9 of 306 metrics in 21 major domains clustered among four dimensions (clinical quality, quality of the patient experience, workforce, and training) as a means of prioritizing improvement efforts and scoring service quality within endoscopy departments. Many measures scored by the GRS are encompassed in the training, privileging, credentialing, accreditation, and employment practices that we use in the United States. As previously noted, a multisociety initiative now is underway to identify unit-level quality metrics analogous to the GRS for application in our country, with consensus measures anticipated by late 2014.

Process measures are applicable at both the unit and the endoscopist level, such as those defining standard preprocedure, intraprocedure, and postprocedure care of all endoscopy patients, as outlined by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy–American College of Gastroenterology work group noted earlier.1

Because electronic systems also harbor data specific to individual endoscopist performance on most nationally defined measures, units should take responsibility for the acquisition and assessment of data and the quality oversight processes pertaining to individual endoscopist measures. This can be challenging, however, because many endoscopists practice at multiple locations. There is not yet a good mechanism to aggregate data at an individual level under this circumstance.

Quality measure reporting for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS has developed a broad and all-encompassing quality strategy that strives to deliver enhanced and affordable care to achieve healthy individuals and communities. The strategy focuses on six National Quality Strategy (NQS) domains, including patient safety, person and caregiver-centered experience and outcomes, communication and care coordination, effective clinical care, community/population health, and efficiency and cost reduction. Toward these ends, numerous voluntary quality programs have been initiated, each with differing time frames, means of data submission, and financial inducements – most of which are evolving into financial penalties for nonparticipation. Two CMS programs are particularly pertinent to ambulatory endoscopy centers, which fall under the category of ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs).

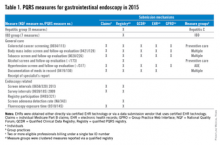

The Physicians Quality Reporting System (PQRS) provides financial incentives to practitioners and groups that submit quality data via any of several mechanisms, including claims-based reporting, certified electronic health records, or participation in qualified registries, which is itself a PQRS quality measure. In past years very few quality measures specific to gastroenterology practice, and even fewer for endoscopy services, were available for reporting. This is gradually changing, however, with several additional measures adopted this year. Measures available for reporting in 2014 are listed in Table 1. Standards for successful reporting evolve each year, so annual reassessment of submission requirements is important. This year, most PQRS reporting options for the 2014 payment incentive (+0.5%) require a practitioner or group to report on nine or more measures from at least three NQS domains (listed previously) for at least 50% of their Medicare Part B fee-for-service (FFS) patients, or report all measures in one measures group on a 20-patient sample, most of whom are Medicare Part B FFS patients.10 To avoid the 2016 downward payment adjustment (−2%), participants must either earn the 2014 PQRS incentive or report on at least three measures covering one NQS domain for at least 50% of their Medicare Part B FFS patients.

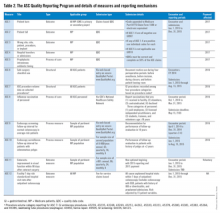

The ASC Quality Reporting Program began in 2012 with five measures developed and owned by the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association. They were generic and applicable to most surgical environments, but minimally so to gastrointestinal endoscopy. During 2014, the ASC Quality Reporting Program will require ASCs to report on 11 perioperative measures (ASC 1-11) to avoid payment decrements for 2016 (Table 2).11 Among these measures, measures 2-4 and 6-10 are pertinent to gastrointestinal endoscopy units. ASC 1 through ASC 5 are reported via claims-based quality data codes (defined for each measure), ASC 8 (influenza vaccination of personnel) is reported on the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network, and the other measures are submitted via web-based entry on the secure quality net portal.

The quality improvement process

Many practice changes can be addressed administratively, but substantive improvement or redesign in care processes is facilitated by formal improvement projects, defined by assembling a team of responsible individuals who define a transparent plan with clearly delineated goals, use of established techniques, and a time line. Improvement teams should include both staff and managers with responsibility for the process or outcome being addressed, and individuals with skills and experience with database queries, data acquisition, statistical assessment, and process control charting.

Most major quality improvement methodologies use steps analogous to those of the basic plan, do, study, act method, which uses cycles of planning, pilot testing, analysis of test results and lessons learned, followed by full adoption of new processes into practice, vs. repeated plan, do, study, act method cycles. This approach is used commonly to identify rapid stepwise improvements when time and resources are limited.

Commonly used quality-assurance practices

Numerous well-established practices in health care provide oversight and assurance regarding the quality of care delivered by an individual or a practice (Table 3). They vary greatly in rigor and frequency of use. Some are mandated and several others can be adapted easily for use by independent ambulatory centers.

Accreditation, or analogous state health department certification, is required by the CMS to gain so-called deemed status, by which a facility is deemed to be in compliance with CMS’s regulatory standards, as delineated in the Conditions for Participation (available at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CFCsAndCoPs/index.html?redirect=/CFCsAndCoPs/06_Hospitals.asp). Deemed status is required to bill for service to CMS clients. Accreditation, therefore, encompasses numerous other expectations, including credentialing of professional staff at initial appointment and biannual privileging thereafter, monitoring of adverse and sentinel events, routine assessment of patient satisfaction, and use of ongoing quality improvement programs pertinent to the services delivered. Despite their seemingly burdensome nature, these processes should be embraced as opportunities for a facility to unapologetically assess the quality of their providers, outcomes for their patients, and overall practice performance.

Benchmarking is a method for comparing one’s performance and outcomes against those from similar individuals or institutions. In contrast to audit-feedback programs, external benchmarking sometimes is referred to as participation in a registry that typically provides comparison against aggregate data from many groups. Risk adjustment for differences in populations and services can enable comparison between disparate groups. A prime motivation for participating in national registries for endoscopy or other focused practice areas within clinical gastroenterology (hepatitis and inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] care) is to facilitate automated submission of performance data on quality measures to CMS, for which entry of some measures is required to be completed through certified registries. As these mechanisms evolve, registry participation will become another de facto necessity for most practices.

The GI Quality Improvement Consortium is a nonprofit national registry collaboratively established and wholly owned by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the ACG, and built and run by Quintiles Outcomes Inc. The program provides comparative results on numerous unit-wide and physician-specific quality measures pertaining to endoscopy (colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy; endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pending). The measures of interest are submitted electronically after either manual abstraction or automated retrieval from an electronic endoscopic report generator. Registered physicians can report individual PQRS measures and measure groups via the Outcome PQRS registry, which generally provides greater success in participation, compared with submission via the claims-based mechanism. The GI Quality Improvement Consortium also provides the measures and results necessary for providers to complete an American Board of Internal Medicine self-directed Practice Improvement Module (PIM) for either colonoscopy or esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Built in partnership with the Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute, the AGA Digestive Health Recognition Program (DHRP) was designed to provide quality reporting that is familiar to payers, and has been successful in other specialties. In addition, the DHRP supports the submission of data to the CMS to meet requirements for the PQRS, and avoid reimbursement penalties for nonparticipation. In the DHRP, 30 consecutive Medicare patients are used for data extraction and submission using a web-based tool. DHRP currently is available for IBD and hepatitis C practices, and is linked to Bridges to Excellence recognition, a program of the Healthcare Incentives Improvement Institute, designed to recognize and reward clinicians who deliver superior patient care. The DHRP also supplies providers with the measures and results necessary to complete an ABIM self-directed Practice Improvement Module for either IBD or hepatitis C. A module is in development for colon cancer prevention (available at: http://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/aga-digestive-health-recognition-program).

Summary

All gastroenterologists should be familiar with the quality improvement process. Participation in formal quality improvement efforts is now required for accreditation, board certification, and, in some cases, payer reimbursement. Endoscopy facilities should embrace their role as the data resource and oversight body for unit-wide and most endoscopist-specific quality initiatives. This necessitates investments in infrastructure and personnel. Ultimately, such efforts benefit both our patients and our professional endeavors.

References

1. Kheraj, R., Tewani, S.K., Ketwaroo, G., et al. Quality improvement in gastroenterology clinical practice. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10:1305-14.

2. Faigel, D.O., Pike, I.M., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: an introduction. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S3-S9.

3. Cohen, J., Safdi, M.A., Deal, S.E., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:S10-S15.

4. Rex, D.K., Petrini, J.L., Baron, T.H., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S16-S28.

5. Baron, T.H., Petersen, B.T., Mergener, K.,and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S29-S34.

6. Jacobson, B.C., Chak, A., Hoffman, B., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S35-S38.

7. Petersen, B.T. Quality in the ambulatory endoscopy center. Tech. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011;13:224-8.

Petersen, B.T. Quality assurance for endoscopists. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011;25:349-61.

8. Global Rating Scale. Available at: http://www.globalratingscale.com. Accessed January 1, 2014.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Measures Codes. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/MeasuresCodes.html. Accessed March 31, 2014.

9. QualityNet. Overview: Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting (ASCQR) Program. Available at: https://www.qualitynet.org. Accessed March 31, 2014.

10. Cotton, P.B., Eisen, G.M., Aabakken, L. et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE Workshop. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010;71:446-54.

11. ASGE Endoscopy Unit Recognition Program. Available at: http://www.asge.org/clinicalpractice/clinical-practice.aspx?id=13576. Accessed March 31, 2014.

Dr. Petersen is professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He has no conflicts of interest.

Quality measurement and performance improvement now are accepted uniformly as key strategies and responsibilities in the delivery of health care,1 including in the management of gastrointestinal endoscopic services. Numerous metrics for quality performance by endoscopists have been adopted in recent years2,3,4,5,6 and now are being updated for 2014. Unit-specific measures pertaining to customer care, safety and infection control, communication and continuity of care, efficiency, and procedure-specific unit factors also are under development by gastrointestinal and surgical societies at this time. Until recently, the mandates and inducements for assessing and improving quality from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, accreditation organizations, and state health departments have been very generic, but measures adopted for 2014 and beyond incorporate greater numbers of endoscopy-specific expectations. In contrast, private payers have been slow to delineate quality-based performance expectations or thresholds for reimbursement. Beyond regulatory requirements, additional issues warrant focused attention to maintain the quality of care delivery. In this article, I address quality improvement principles for ambulatory endoscopy centers.

A number of metrics commonly are used for tracking the financial health of endoscopy centers, including physician-, unit-, and practice-specific costs and revenues prorated to procedural volume, space, or unit of time. Similarly, the high-quality facility is also dependent on recruitment and care of a cohesive team of physicians, nurses, and supporting personnel. This is an ongoing task that requires specific intent and planning. Although benchmarks for personnel management and financial performance commonly are used, they are both beyond the scope of this article.

Quality measurement concepts

Quality improvement efforts are based on the principle that performance can be measured and compared with optimal performance to identify needs for improvement (gaps) so that leaders then can alter structures or processes to improve health outcomes for patients. Performance on a given parameter (commonly termed a metric, measure, or indicator) is expressed as a ratio between a numerator, representing the incidence of correct performance, and a denominator, representing the opportunities for correct performance. To enable uniform data collection and interpretation, measures should be defined formally in advance of improvement efforts. Measures used for regulatory or reimbursement purposes are rigidly standardized and often use cumbersome administrative codes for claims-based reporting, but those identified for submission via registries, or for local improvement efforts, can be stated more simply using clinical terminology.

Optimal metrics should correlate with pertinent clinical outcomes and be evidence based, reproducible, feasible to collect, and amenable to improvement. Measures typically are identified by the type of performance assessed: structural measures address features of the environment of care (such as training, staffing, facilities, and policies); process measures address performance in the delivery of care (routine use of antibiotics in cirrhotic patients admitted with gastrointestinal bleeding, use of appropriate intervals for screening and surveillance colonoscopy); and outcome measures address the results of care from the patient’s perspective (resolution of infection, occurrence of interval cancer, and so forth).

Requirements for successful quality improvement efforts

The requirements for effective quality improvement initiatives in an ambulatory endoscopy center include the following: (1) recognition of the need for improvement; (2) motivation, leadership, and coherent advocacy for improvement from the unit’s owners, partners, and management; (3) clear definition of the gaps or shortcomings in performance and their contributing factors; (4) availability of timely and accurate data; and (5) a process for achieving the desired change.7

Challenges to quality endeavors on a local level include insufficient awareness, willingness, knowledge base in expectations and solutions, improvement expertise, time, and financial resources.

Significant investments in infrastructure, staff time, and expertise are required for larger improvement efforts and fulfilling national expectations for performance and data submission. For short-term ad hoc improvement projects, manual data tracking and display typically are sufficient. Automated data accrual is helpful for larger settings, ongoing tracking of performance, and serial submission of data for benchmarking and regulatory or reimbursement purposes. The repetitive nature of gastrointestinal endoscopy simplifies uniform documentation and data accrual via standardized electronic report generators. CMS-qualified report generators and electronic health records are now becoming essential business tools.

In small ambulatory endoscopy centers, quality oversight may be shared by all partners or a managing partner and administrator. In large endoscopy facilities, quality improvement may be managed primarily by a nonphysician manager or specialist. Adoption of electronic systems and submission of quality data requires expertise in information technology and CMS coding and billing. Quality monitoring and improvement efforts often benefit from skills in project management, statistical assessment, and process control charting. Many of the major skills involved can be contracted out or acquired with purchased systems, but some degree of on-site employed expertise should be considered a modern cost of practice, despite a lack of funding to meet the evolving mandates.

Recognizing and prioritizing improvement opportunities

Every facility has opportunities for improvement in safety, efficiency, clinical outcomes, cost, or service. However, the capacity to undertake quality improvement initiatives usually is constrained, therefore departments must prioritize their efforts. Top priority should be given to the following: (1) gaps in care that pose a direct risk to patient safety or procedural outcomes (such as suboptimal processes or performance in preprocedure and postprocedure management of anticoagulants, antibiotics, hypoglycemic agents, and other medications; intraprocedural sedation practices; endoscope reprocessing; and major lapses in endoscopists’ procedural safety or performance); (2) measures required to ensure full reimbursement, such as licensure, deemed status, and other measures stipulated by CMS and accreditation organizations; (3) glaring issues related to patient dissatisfaction; and (4) quality measures promulgated by national and international organizations. Additional quality needs can be identified by attention to near-miss, never, or sentinel events (all of which warrant investigation for structural or process failures), patient complaints, and repeated mention on patient, employee, or referring physician questionnaires. Units must be aware of health system, state, and federal requirements for reporting (for example, wrong site of surgery) and implement processes to comply with these regulations.

Most well-managed departments already have addressed basic quality issues, allowing them to focus on other less glaring gaps in performance, including those unique to their specific environment or patient population. One useful practice for identifying improvement opportunities is to perform an assessment of lapses and bottlenecks in the sequential steps in care, from the referral process to scheduling, preprocedure exchange of information and patient guidance, preparation, check-in, procedure performance, recovery, dismissal process and guidance, and subsequent communication of results (called value mapping in Lean terminology). Ancillary aspects of care that tie into this linear process include periprocedural management of families, supplies, medications, pathology samples, procedural results, and so forth.

Quality metrics for endoscopy vary in their applicability to entire units vs. individual endoscopists and/or patients.8 Structural measures pertaining to the facility, personnel management, policies, and procedures are intended for application on the unit level; indeed, many are delineated in the CMS’s “Conditions for Participation” and, hence, are subject to scrutiny during accreditation surveys. The United Kingdom’s National Health Service uses a global rating scale (GRS)9 of 306 metrics in 21 major domains clustered among four dimensions (clinical quality, quality of the patient experience, workforce, and training) as a means of prioritizing improvement efforts and scoring service quality within endoscopy departments. Many measures scored by the GRS are encompassed in the training, privileging, credentialing, accreditation, and employment practices that we use in the United States. As previously noted, a multisociety initiative now is underway to identify unit-level quality metrics analogous to the GRS for application in our country, with consensus measures anticipated by late 2014.

Process measures are applicable at both the unit and the endoscopist level, such as those defining standard preprocedure, intraprocedure, and postprocedure care of all endoscopy patients, as outlined by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy–American College of Gastroenterology work group noted earlier.1

Because electronic systems also harbor data specific to individual endoscopist performance on most nationally defined measures, units should take responsibility for the acquisition and assessment of data and the quality oversight processes pertaining to individual endoscopist measures. This can be challenging, however, because many endoscopists practice at multiple locations. There is not yet a good mechanism to aggregate data at an individual level under this circumstance.

Quality measure reporting for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS has developed a broad and all-encompassing quality strategy that strives to deliver enhanced and affordable care to achieve healthy individuals and communities. The strategy focuses on six National Quality Strategy (NQS) domains, including patient safety, person and caregiver-centered experience and outcomes, communication and care coordination, effective clinical care, community/population health, and efficiency and cost reduction. Toward these ends, numerous voluntary quality programs have been initiated, each with differing time frames, means of data submission, and financial inducements – most of which are evolving into financial penalties for nonparticipation. Two CMS programs are particularly pertinent to ambulatory endoscopy centers, which fall under the category of ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs).

The Physicians Quality Reporting System (PQRS) provides financial incentives to practitioners and groups that submit quality data via any of several mechanisms, including claims-based reporting, certified electronic health records, or participation in qualified registries, which is itself a PQRS quality measure. In past years very few quality measures specific to gastroenterology practice, and even fewer for endoscopy services, were available for reporting. This is gradually changing, however, with several additional measures adopted this year. Measures available for reporting in 2014 are listed in Table 1. Standards for successful reporting evolve each year, so annual reassessment of submission requirements is important. This year, most PQRS reporting options for the 2014 payment incentive (+0.5%) require a practitioner or group to report on nine or more measures from at least three NQS domains (listed previously) for at least 50% of their Medicare Part B fee-for-service (FFS) patients, or report all measures in one measures group on a 20-patient sample, most of whom are Medicare Part B FFS patients.10 To avoid the 2016 downward payment adjustment (−2%), participants must either earn the 2014 PQRS incentive or report on at least three measures covering one NQS domain for at least 50% of their Medicare Part B FFS patients.

The ASC Quality Reporting Program began in 2012 with five measures developed and owned by the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association. They were generic and applicable to most surgical environments, but minimally so to gastrointestinal endoscopy. During 2014, the ASC Quality Reporting Program will require ASCs to report on 11 perioperative measures (ASC 1-11) to avoid payment decrements for 2016 (Table 2).11 Among these measures, measures 2-4 and 6-10 are pertinent to gastrointestinal endoscopy units. ASC 1 through ASC 5 are reported via claims-based quality data codes (defined for each measure), ASC 8 (influenza vaccination of personnel) is reported on the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network, and the other measures are submitted via web-based entry on the secure quality net portal.

The quality improvement process

Many practice changes can be addressed administratively, but substantive improvement or redesign in care processes is facilitated by formal improvement projects, defined by assembling a team of responsible individuals who define a transparent plan with clearly delineated goals, use of established techniques, and a time line. Improvement teams should include both staff and managers with responsibility for the process or outcome being addressed, and individuals with skills and experience with database queries, data acquisition, statistical assessment, and process control charting.

Most major quality improvement methodologies use steps analogous to those of the basic plan, do, study, act method, which uses cycles of planning, pilot testing, analysis of test results and lessons learned, followed by full adoption of new processes into practice, vs. repeated plan, do, study, act method cycles. This approach is used commonly to identify rapid stepwise improvements when time and resources are limited.

Commonly used quality-assurance practices

Numerous well-established practices in health care provide oversight and assurance regarding the quality of care delivered by an individual or a practice (Table 3). They vary greatly in rigor and frequency of use. Some are mandated and several others can be adapted easily for use by independent ambulatory centers.

Accreditation, or analogous state health department certification, is required by the CMS to gain so-called deemed status, by which a facility is deemed to be in compliance with CMS’s regulatory standards, as delineated in the Conditions for Participation (available at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CFCsAndCoPs/index.html?redirect=/CFCsAndCoPs/06_Hospitals.asp). Deemed status is required to bill for service to CMS clients. Accreditation, therefore, encompasses numerous other expectations, including credentialing of professional staff at initial appointment and biannual privileging thereafter, monitoring of adverse and sentinel events, routine assessment of patient satisfaction, and use of ongoing quality improvement programs pertinent to the services delivered. Despite their seemingly burdensome nature, these processes should be embraced as opportunities for a facility to unapologetically assess the quality of their providers, outcomes for their patients, and overall practice performance.

Benchmarking is a method for comparing one’s performance and outcomes against those from similar individuals or institutions. In contrast to audit-feedback programs, external benchmarking sometimes is referred to as participation in a registry that typically provides comparison against aggregate data from many groups. Risk adjustment for differences in populations and services can enable comparison between disparate groups. A prime motivation for participating in national registries for endoscopy or other focused practice areas within clinical gastroenterology (hepatitis and inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] care) is to facilitate automated submission of performance data on quality measures to CMS, for which entry of some measures is required to be completed through certified registries. As these mechanisms evolve, registry participation will become another de facto necessity for most practices.

The GI Quality Improvement Consortium is a nonprofit national registry collaboratively established and wholly owned by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the ACG, and built and run by Quintiles Outcomes Inc. The program provides comparative results on numerous unit-wide and physician-specific quality measures pertaining to endoscopy (colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy; endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pending). The measures of interest are submitted electronically after either manual abstraction or automated retrieval from an electronic endoscopic report generator. Registered physicians can report individual PQRS measures and measure groups via the Outcome PQRS registry, which generally provides greater success in participation, compared with submission via the claims-based mechanism. The GI Quality Improvement Consortium also provides the measures and results necessary for providers to complete an American Board of Internal Medicine self-directed Practice Improvement Module (PIM) for either colonoscopy or esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Built in partnership with the Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute, the AGA Digestive Health Recognition Program (DHRP) was designed to provide quality reporting that is familiar to payers, and has been successful in other specialties. In addition, the DHRP supports the submission of data to the CMS to meet requirements for the PQRS, and avoid reimbursement penalties for nonparticipation. In the DHRP, 30 consecutive Medicare patients are used for data extraction and submission using a web-based tool. DHRP currently is available for IBD and hepatitis C practices, and is linked to Bridges to Excellence recognition, a program of the Healthcare Incentives Improvement Institute, designed to recognize and reward clinicians who deliver superior patient care. The DHRP also supplies providers with the measures and results necessary to complete an ABIM self-directed Practice Improvement Module for either IBD or hepatitis C. A module is in development for colon cancer prevention (available at: http://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/aga-digestive-health-recognition-program).

Summary

All gastroenterologists should be familiar with the quality improvement process. Participation in formal quality improvement efforts is now required for accreditation, board certification, and, in some cases, payer reimbursement. Endoscopy facilities should embrace their role as the data resource and oversight body for unit-wide and most endoscopist-specific quality initiatives. This necessitates investments in infrastructure and personnel. Ultimately, such efforts benefit both our patients and our professional endeavors.

References

1. Kheraj, R., Tewani, S.K., Ketwaroo, G., et al. Quality improvement in gastroenterology clinical practice. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10:1305-14.

2. Faigel, D.O., Pike, I.M., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: an introduction. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S3-S9.

3. Cohen, J., Safdi, M.A., Deal, S.E., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:S10-S15.

4. Rex, D.K., Petrini, J.L., Baron, T.H., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S16-S28.

5. Baron, T.H., Petersen, B.T., Mergener, K.,and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S29-S34.

6. Jacobson, B.C., Chak, A., Hoffman, B., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S35-S38.

7. Petersen, B.T. Quality in the ambulatory endoscopy center. Tech. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011;13:224-8.

Petersen, B.T. Quality assurance for endoscopists. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011;25:349-61.

8. Global Rating Scale. Available at: http://www.globalratingscale.com. Accessed January 1, 2014.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Measures Codes. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/MeasuresCodes.html. Accessed March 31, 2014.

9. QualityNet. Overview: Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting (ASCQR) Program. Available at: https://www.qualitynet.org. Accessed March 31, 2014.

10. Cotton, P.B., Eisen, G.M., Aabakken, L. et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE Workshop. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010;71:446-54.

11. ASGE Endoscopy Unit Recognition Program. Available at: http://www.asge.org/clinicalpractice/clinical-practice.aspx?id=13576. Accessed March 31, 2014.

Dr. Petersen is professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He has no conflicts of interest.

Quality measurement and performance improvement now are accepted uniformly as key strategies and responsibilities in the delivery of health care,1 including in the management of gastrointestinal endoscopic services. Numerous metrics for quality performance by endoscopists have been adopted in recent years2,3,4,5,6 and now are being updated for 2014. Unit-specific measures pertaining to customer care, safety and infection control, communication and continuity of care, efficiency, and procedure-specific unit factors also are under development by gastrointestinal and surgical societies at this time. Until recently, the mandates and inducements for assessing and improving quality from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, accreditation organizations, and state health departments have been very generic, but measures adopted for 2014 and beyond incorporate greater numbers of endoscopy-specific expectations. In contrast, private payers have been slow to delineate quality-based performance expectations or thresholds for reimbursement. Beyond regulatory requirements, additional issues warrant focused attention to maintain the quality of care delivery. In this article, I address quality improvement principles for ambulatory endoscopy centers.

A number of metrics commonly are used for tracking the financial health of endoscopy centers, including physician-, unit-, and practice-specific costs and revenues prorated to procedural volume, space, or unit of time. Similarly, the high-quality facility is also dependent on recruitment and care of a cohesive team of physicians, nurses, and supporting personnel. This is an ongoing task that requires specific intent and planning. Although benchmarks for personnel management and financial performance commonly are used, they are both beyond the scope of this article.

Quality measurement concepts

Quality improvement efforts are based on the principle that performance can be measured and compared with optimal performance to identify needs for improvement (gaps) so that leaders then can alter structures or processes to improve health outcomes for patients. Performance on a given parameter (commonly termed a metric, measure, or indicator) is expressed as a ratio between a numerator, representing the incidence of correct performance, and a denominator, representing the opportunities for correct performance. To enable uniform data collection and interpretation, measures should be defined formally in advance of improvement efforts. Measures used for regulatory or reimbursement purposes are rigidly standardized and often use cumbersome administrative codes for claims-based reporting, but those identified for submission via registries, or for local improvement efforts, can be stated more simply using clinical terminology.

Optimal metrics should correlate with pertinent clinical outcomes and be evidence based, reproducible, feasible to collect, and amenable to improvement. Measures typically are identified by the type of performance assessed: structural measures address features of the environment of care (such as training, staffing, facilities, and policies); process measures address performance in the delivery of care (routine use of antibiotics in cirrhotic patients admitted with gastrointestinal bleeding, use of appropriate intervals for screening and surveillance colonoscopy); and outcome measures address the results of care from the patient’s perspective (resolution of infection, occurrence of interval cancer, and so forth).

Requirements for successful quality improvement efforts

The requirements for effective quality improvement initiatives in an ambulatory endoscopy center include the following: (1) recognition of the need for improvement; (2) motivation, leadership, and coherent advocacy for improvement from the unit’s owners, partners, and management; (3) clear definition of the gaps or shortcomings in performance and their contributing factors; (4) availability of timely and accurate data; and (5) a process for achieving the desired change.7

Challenges to quality endeavors on a local level include insufficient awareness, willingness, knowledge base in expectations and solutions, improvement expertise, time, and financial resources.

Significant investments in infrastructure, staff time, and expertise are required for larger improvement efforts and fulfilling national expectations for performance and data submission. For short-term ad hoc improvement projects, manual data tracking and display typically are sufficient. Automated data accrual is helpful for larger settings, ongoing tracking of performance, and serial submission of data for benchmarking and regulatory or reimbursement purposes. The repetitive nature of gastrointestinal endoscopy simplifies uniform documentation and data accrual via standardized electronic report generators. CMS-qualified report generators and electronic health records are now becoming essential business tools.

In small ambulatory endoscopy centers, quality oversight may be shared by all partners or a managing partner and administrator. In large endoscopy facilities, quality improvement may be managed primarily by a nonphysician manager or specialist. Adoption of electronic systems and submission of quality data requires expertise in information technology and CMS coding and billing. Quality monitoring and improvement efforts often benefit from skills in project management, statistical assessment, and process control charting. Many of the major skills involved can be contracted out or acquired with purchased systems, but some degree of on-site employed expertise should be considered a modern cost of practice, despite a lack of funding to meet the evolving mandates.

Recognizing and prioritizing improvement opportunities

Every facility has opportunities for improvement in safety, efficiency, clinical outcomes, cost, or service. However, the capacity to undertake quality improvement initiatives usually is constrained, therefore departments must prioritize their efforts. Top priority should be given to the following: (1) gaps in care that pose a direct risk to patient safety or procedural outcomes (such as suboptimal processes or performance in preprocedure and postprocedure management of anticoagulants, antibiotics, hypoglycemic agents, and other medications; intraprocedural sedation practices; endoscope reprocessing; and major lapses in endoscopists’ procedural safety or performance); (2) measures required to ensure full reimbursement, such as licensure, deemed status, and other measures stipulated by CMS and accreditation organizations; (3) glaring issues related to patient dissatisfaction; and (4) quality measures promulgated by national and international organizations. Additional quality needs can be identified by attention to near-miss, never, or sentinel events (all of which warrant investigation for structural or process failures), patient complaints, and repeated mention on patient, employee, or referring physician questionnaires. Units must be aware of health system, state, and federal requirements for reporting (for example, wrong site of surgery) and implement processes to comply with these regulations.

Most well-managed departments already have addressed basic quality issues, allowing them to focus on other less glaring gaps in performance, including those unique to their specific environment or patient population. One useful practice for identifying improvement opportunities is to perform an assessment of lapses and bottlenecks in the sequential steps in care, from the referral process to scheduling, preprocedure exchange of information and patient guidance, preparation, check-in, procedure performance, recovery, dismissal process and guidance, and subsequent communication of results (called value mapping in Lean terminology). Ancillary aspects of care that tie into this linear process include periprocedural management of families, supplies, medications, pathology samples, procedural results, and so forth.

Quality metrics for endoscopy vary in their applicability to entire units vs. individual endoscopists and/or patients.8 Structural measures pertaining to the facility, personnel management, policies, and procedures are intended for application on the unit level; indeed, many are delineated in the CMS’s “Conditions for Participation” and, hence, are subject to scrutiny during accreditation surveys. The United Kingdom’s National Health Service uses a global rating scale (GRS)9 of 306 metrics in 21 major domains clustered among four dimensions (clinical quality, quality of the patient experience, workforce, and training) as a means of prioritizing improvement efforts and scoring service quality within endoscopy departments. Many measures scored by the GRS are encompassed in the training, privileging, credentialing, accreditation, and employment practices that we use in the United States. As previously noted, a multisociety initiative now is underway to identify unit-level quality metrics analogous to the GRS for application in our country, with consensus measures anticipated by late 2014.

Process measures are applicable at both the unit and the endoscopist level, such as those defining standard preprocedure, intraprocedure, and postprocedure care of all endoscopy patients, as outlined by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy–American College of Gastroenterology work group noted earlier.1

Because electronic systems also harbor data specific to individual endoscopist performance on most nationally defined measures, units should take responsibility for the acquisition and assessment of data and the quality oversight processes pertaining to individual endoscopist measures. This can be challenging, however, because many endoscopists practice at multiple locations. There is not yet a good mechanism to aggregate data at an individual level under this circumstance.

Quality measure reporting for the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. CMS has developed a broad and all-encompassing quality strategy that strives to deliver enhanced and affordable care to achieve healthy individuals and communities. The strategy focuses on six National Quality Strategy (NQS) domains, including patient safety, person and caregiver-centered experience and outcomes, communication and care coordination, effective clinical care, community/population health, and efficiency and cost reduction. Toward these ends, numerous voluntary quality programs have been initiated, each with differing time frames, means of data submission, and financial inducements – most of which are evolving into financial penalties for nonparticipation. Two CMS programs are particularly pertinent to ambulatory endoscopy centers, which fall under the category of ambulatory surgery centers (ASCs).

The Physicians Quality Reporting System (PQRS) provides financial incentives to practitioners and groups that submit quality data via any of several mechanisms, including claims-based reporting, certified electronic health records, or participation in qualified registries, which is itself a PQRS quality measure. In past years very few quality measures specific to gastroenterology practice, and even fewer for endoscopy services, were available for reporting. This is gradually changing, however, with several additional measures adopted this year. Measures available for reporting in 2014 are listed in Table 1. Standards for successful reporting evolve each year, so annual reassessment of submission requirements is important. This year, most PQRS reporting options for the 2014 payment incentive (+0.5%) require a practitioner or group to report on nine or more measures from at least three NQS domains (listed previously) for at least 50% of their Medicare Part B fee-for-service (FFS) patients, or report all measures in one measures group on a 20-patient sample, most of whom are Medicare Part B FFS patients.10 To avoid the 2016 downward payment adjustment (−2%), participants must either earn the 2014 PQRS incentive or report on at least three measures covering one NQS domain for at least 50% of their Medicare Part B FFS patients.

The ASC Quality Reporting Program began in 2012 with five measures developed and owned by the Ambulatory Surgery Center Association. They were generic and applicable to most surgical environments, but minimally so to gastrointestinal endoscopy. During 2014, the ASC Quality Reporting Program will require ASCs to report on 11 perioperative measures (ASC 1-11) to avoid payment decrements for 2016 (Table 2).11 Among these measures, measures 2-4 and 6-10 are pertinent to gastrointestinal endoscopy units. ASC 1 through ASC 5 are reported via claims-based quality data codes (defined for each measure), ASC 8 (influenza vaccination of personnel) is reported on the CDC’s National Healthcare Safety Network, and the other measures are submitted via web-based entry on the secure quality net portal.

The quality improvement process

Many practice changes can be addressed administratively, but substantive improvement or redesign in care processes is facilitated by formal improvement projects, defined by assembling a team of responsible individuals who define a transparent plan with clearly delineated goals, use of established techniques, and a time line. Improvement teams should include both staff and managers with responsibility for the process or outcome being addressed, and individuals with skills and experience with database queries, data acquisition, statistical assessment, and process control charting.

Most major quality improvement methodologies use steps analogous to those of the basic plan, do, study, act method, which uses cycles of planning, pilot testing, analysis of test results and lessons learned, followed by full adoption of new processes into practice, vs. repeated plan, do, study, act method cycles. This approach is used commonly to identify rapid stepwise improvements when time and resources are limited.

Commonly used quality-assurance practices

Numerous well-established practices in health care provide oversight and assurance regarding the quality of care delivered by an individual or a practice (Table 3). They vary greatly in rigor and frequency of use. Some are mandated and several others can be adapted easily for use by independent ambulatory centers.

Accreditation, or analogous state health department certification, is required by the CMS to gain so-called deemed status, by which a facility is deemed to be in compliance with CMS’s regulatory standards, as delineated in the Conditions for Participation (available at: https://www.cms.gov/Regulations-and-Guidance/Legislation/CFCsAndCoPs/index.html?redirect=/CFCsAndCoPs/06_Hospitals.asp). Deemed status is required to bill for service to CMS clients. Accreditation, therefore, encompasses numerous other expectations, including credentialing of professional staff at initial appointment and biannual privileging thereafter, monitoring of adverse and sentinel events, routine assessment of patient satisfaction, and use of ongoing quality improvement programs pertinent to the services delivered. Despite their seemingly burdensome nature, these processes should be embraced as opportunities for a facility to unapologetically assess the quality of their providers, outcomes for their patients, and overall practice performance.

Benchmarking is a method for comparing one’s performance and outcomes against those from similar individuals or institutions. In contrast to audit-feedback programs, external benchmarking sometimes is referred to as participation in a registry that typically provides comparison against aggregate data from many groups. Risk adjustment for differences in populations and services can enable comparison between disparate groups. A prime motivation for participating in national registries for endoscopy or other focused practice areas within clinical gastroenterology (hepatitis and inflammatory bowel disease [IBD] care) is to facilitate automated submission of performance data on quality measures to CMS, for which entry of some measures is required to be completed through certified registries. As these mechanisms evolve, registry participation will become another de facto necessity for most practices.

The GI Quality Improvement Consortium is a nonprofit national registry collaboratively established and wholly owned by the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy and the ACG, and built and run by Quintiles Outcomes Inc. The program provides comparative results on numerous unit-wide and physician-specific quality measures pertaining to endoscopy (colonoscopy and esophagogastroduodenoscopy; endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography pending). The measures of interest are submitted electronically after either manual abstraction or automated retrieval from an electronic endoscopic report generator. Registered physicians can report individual PQRS measures and measure groups via the Outcome PQRS registry, which generally provides greater success in participation, compared with submission via the claims-based mechanism. The GI Quality Improvement Consortium also provides the measures and results necessary for providers to complete an American Board of Internal Medicine self-directed Practice Improvement Module (PIM) for either colonoscopy or esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

Built in partnership with the Health Care Incentives Improvement Institute, the AGA Digestive Health Recognition Program (DHRP) was designed to provide quality reporting that is familiar to payers, and has been successful in other specialties. In addition, the DHRP supports the submission of data to the CMS to meet requirements for the PQRS, and avoid reimbursement penalties for nonparticipation. In the DHRP, 30 consecutive Medicare patients are used for data extraction and submission using a web-based tool. DHRP currently is available for IBD and hepatitis C practices, and is linked to Bridges to Excellence recognition, a program of the Healthcare Incentives Improvement Institute, designed to recognize and reward clinicians who deliver superior patient care. The DHRP also supplies providers with the measures and results necessary to complete an ABIM self-directed Practice Improvement Module for either IBD or hepatitis C. A module is in development for colon cancer prevention (available at: http://www.gastro.org/practice/quality-initiatives/aga-digestive-health-recognition-program).

Summary

All gastroenterologists should be familiar with the quality improvement process. Participation in formal quality improvement efforts is now required for accreditation, board certification, and, in some cases, payer reimbursement. Endoscopy facilities should embrace their role as the data resource and oversight body for unit-wide and most endoscopist-specific quality initiatives. This necessitates investments in infrastructure and personnel. Ultimately, such efforts benefit both our patients and our professional endeavors.

References

1. Kheraj, R., Tewani, S.K., Ketwaroo, G., et al. Quality improvement in gastroenterology clinical practice. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2012;10:1305-14.

2. Faigel, D.O., Pike, I.M., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for gastrointestinal endoscopic procedures: an introduction. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S3-S9.

3. Cohen, J., Safdi, M.A., Deal, S.E., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for esophagogastroduodenoscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;63:S10-S15.

4. Rex, D.K., Petrini, J.L., Baron, T.H., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for colonoscopy. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S16-S28.

5. Baron, T.H., Petersen, B.T., Mergener, K.,and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S29-S34.

6. Jacobson, B.C., Chak, A., Hoffman, B., and the ASGE/ACG Taskforce on Quality in Endoscopy. Quality indicators for endoscopic ultrasonography. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2006;63:S35-S38.

7. Petersen, B.T. Quality in the ambulatory endoscopy center. Tech. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2011;13:224-8.

Petersen, B.T. Quality assurance for endoscopists. Best Pract. Res. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2011;25:349-61.

8. Global Rating Scale. Available at: http://www.globalratingscale.com. Accessed January 1, 2014.

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Measures Codes. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/MeasuresCodes.html. Accessed March 31, 2014.

9. QualityNet. Overview: Ambulatory Surgical Center Quality Reporting (ASCQR) Program. Available at: https://www.qualitynet.org. Accessed March 31, 2014.

10. Cotton, P.B., Eisen, G.M., Aabakken, L. et al. A lexicon for endoscopic adverse events: report of an ASGE Workshop. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2010;71:446-54.

11. ASGE Endoscopy Unit Recognition Program. Available at: http://www.asge.org/clinicalpractice/clinical-practice.aspx?id=13576. Accessed March 31, 2014.

Dr. Petersen is professor of medicine in the division of gastroenterology and hepatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. He has no conflicts of interest.