User login

Decreasing the Incidence of Surgical-Site Infections After Total Joint Arthroplasty

Take-Home Points

- SSIs after TJA pose a substantial burden on patients, surgeons, and the healthcare system.

- While different forms of preoperative skin preparation have shown varying outcomes after TJA, the importance of preoperative patient optimization (nutritional status, immune function, etc) cannot be overstated.

- Intraoperative infection prevention measures include cutaneous preparation, gloving, body exhaust suits, surgical drapes, OR staff traffic and ventilation flow, and antibiotic-loaded cement.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures in TJA patients continues to remain a controversial issue with conflicting recommendations.

- SSIs have considerable financial costs and require increased resource utilization. Given the significant economic burden associated with TJA infections, it is imperative for orthopedists to establish practical and cost-effective strategies to prevent these devastating complications.

Surgical-site infection (SSI), a potentially devastating complication of lower extremity total joint arthroplasty (TJA), is estimated to occur in 1% to 2.5% of cases annually.1 Infection after TJA places a significant burden on patients, surgeons, and the healthcare system. Revision procedures that address infection after total hip arthroplasty (THA) are associated with more hospitalizations, more operations, longer hospital stay, and higher outpatient costs in comparison with primary THAs and revision surgeries for aseptic loosening.2 If left untreated, a SSI can go deeper into the joint and develop into a periprosthetic infection, which can be disastrous and costly. A periprosthetic joint infection study that used 2001 to 2009 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data found that the cost of revision procedures increased to $560 million from $320 million, and was projected to reach $1.62 billion by 2020.3 Furthermore, society incurs indirect costs as a result of patient disability and loss of wages and productivity.2 Therefore, the issue of infection after TJA is even more crucial in our cost-conscious healthcare environment.

Patient optimization, advances in surgical technique, sterile protocol, and operative procedures have been effective in reducing bacterial counts at incision sites and minimizing SSIs. As a result, infection rates have leveled off after rising for a decade.4 Although infection prevention modalities have their differences, routine use is fundamental and recommended by the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee.5 Furthermore, both the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee6,7 recently updated their SSI prevention guidelines by incorporating evidence-based methodology, an element missing from earlier recommendations.

The etiologies of postoperative SSIs have been discussed ad nauseam, but there are few reports summarizing the literature on infection prevention modalities. In this review, we identify and examine SSI prevention strategies as they relate to lower extremity TJA. Specifically, we discuss the literature on the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative actions that can be taken to reduce the incidence of SSIs after TJA. We also highlight the economic implications of SSIs that occur after TJA.

Methods

For this review, we performed a literature search with PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Scopus. We looked for reports published between the inception of each database and July 2016. Combinations of various search terms were used: surgical site, infection, total joint arthroplasty, knee, hip, preoperative, intraoperative, perioperative, postoperative, preparation, nutrition, ventilation, antibiotic, body exhaust suit, gloves, drain, costs, economic, and payment.

Our search identified 195 abstracts. Drs. Mistry and Chughtai reviewed these to determine which articles were relevant. For any uncertainties, consensus was reached with the help of Dr. Delanois. Of the 195 articles, 103 were potentially relevant, and 54 of the 103 were excluded for being not relevant to preventing SSIs after TJA or for being written in a language other than English. The references in the remaining articles were assessed, and those with potentially relevant titles were selected for abstract review. This step provided another 35 articles. After all exclusions, 48 articles remained. We discuss these in the context of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative measures and economic impact.

Results

Preoperative Measures

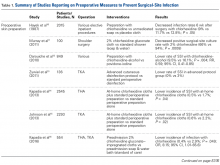

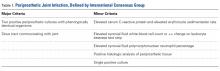

Skin Preparation. Preoperative skin preparation methods include standard washing and rinsing, antiseptic soaps, and iodine-based or chlorhexidine gluconate-based antiseptic showers or skin cloths. Iodine-based antiseptics are effective against a wide range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, and viruses. These agents penetrate the cell wall, oxidize the microbial contents, and replace those contents with free iodine molecules.8 Iodophors are free iodine molecules associated with a polymer (eg, polyvinylpyrrolidone); the iodophor povidone-iodine is bactericidal.9 Chlorhexidine gluconate-based solutions are effective against many types of yeast, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and a wide variety of viruses.9 Both solutions are useful. Patients with an allergy to iodine can use chlorhexidine. Table 1 summarizes the studies on preoperative measures for preventing SSIs.

There is no shortage of evidence of the efficacy of these antiseptics in minimizing the incidence of SSIs. Hayek and colleagues10 prospectively analyzed use of different preoperative skin preparation methods in 2015 patients. Six weeks after surgery, the infection rate was significantly lower with use of chlorhexidine than with use of an unmedicated bar of soap or placebo cloth (9% vs 11.7% and 12.8%, respectively; P < .05). In a study of 100 patients, Murray and colleagues11 found the overall bacterial culture rate was significantly lower for those who used a 2% chlorhexidine gluconate cloth before shoulder surgery than for those who took a standard shower with soap (66% vs 94%; P = .0008). Darouiche and colleagues12 found the overall SSI rate was significantly lower for 409 surgical patients prepared with chlorhexidine-alcohol than for 440 prepared with povidone-iodine (9.5% vs 16.1%; P = .004; relative risk [RR], 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.41-0.85).

Chlorhexidine gluconate-impregnated cloths have also had promising results, which may be attributed to general ease of use and potentially improved patient adherence. Zywiel and colleagues13 reported no SSIs in 136 patients who used these cloths at home before total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and 21 SSIs (3.0%) in 711 patients who did not use the cloths. In a study of 2545 THA patients, Kapadia and colleagues14 noted a significantly lower incidence of SSIs with at-home preoperative use of chlorhexidine cloths than with only in-hospital perioperative skin preparation (0.5% vs 1.7%; P = .04). In 2293 TKAs, Johnson and colleagues15 similarly found a lower incidence of SSIs with at-home preoperative use of chlorhexidine cloths (0.6% vs 2.2%; P = .02). In another prospective, randomized trial, Kapadia and colleagues16 compared 275 patients who used chlorhexidine cloths the night before and the morning of lower extremity TJA surgery with 279 patients who underwent standard-of-care preparation (preadmission bathing with antibacterial soap and water). The chlorhexidine cohort had a lower overall incidence of infection (0.4% vs 2.9%; P = .049), and the standard-of-care cohort had a stronger association with infection (odds ratio [OR], 8.15; 95% CI, 1.01-65.6).

Patient Optimization. Poor nutritional status may compromise immune function, potentially resulting in delayed healing, increased risk of infection, and, ultimately, negative postoperative outcomes. Malnutrition can be diagnosed on the basis of a prealbumin level of <15 mg/dL (normal, 15-30 mg/dL), a serum albumin level of <3.4 g/dL (normal, 3.4-5.4 g/dL), or a total lymphocyte count under 1200 cells/μL (normal, 3900-10,000 cells/μL).17-19 Greene and colleagues18 found that patients with preoperative malnutrition had up to a 7-fold higher rate of infection after TJA. In a study of 135 THAs and TKAs, Alfargieny and colleagues20 found preoperative serum albumin was the only nutritional biomarker predictive of SSI (P = .011). Furthermore, patients who take immunomodulating medications (eg, for inflammatory arthropathies) should temporarily discontinue them before surgery in order to lower their risk of infection.21

Smoking is well established as a major risk factor for poor outcomes after surgery. It is postulated that the vasoconstrictive effects of nicotine and the hypoxic effects of carbon monoxide contribute to poor wound healing.22 In a meta-analysis of 4 studies, Sørensen23 found smokers were at increased risk for wound complications (OR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.82-2.84), delayed wound healing and dehiscence (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.53-2.81), and infection (OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.57-2.04). Moreover, smoking cessation decreased the incidence of SSIs (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21-0.85). A meta- analysis by Wong and colleagues24 revealed an inflection point for improved outcomes in patients who abstained from smoking for at least 4 weeks before surgery. Risk of infection was lower for these patients than for current smokers (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.56-0.84).

Other comorbidities contribute to SSIs as well. In their analysis of American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program registry data on 25,235 patients who underwent primary and revision lower extremity TJA, Pugely and colleagues25 found that, in the primary TJA cohort, body mass index (BMI) of >40 kg/m2 (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.3-2.9), electrolyte disturbance (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.0-6.0), and hypertension diagnosis (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.0) increased the risk of SSI within 30 days. Furthermore, diabetes mellitus delays collagen synthesis, impairs lymphocyte function, and impairs wound healing, which may lead to poor recovery and higher risk of infection.26 In a study of 167 TKAs performed in 115 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, Han and Kang26 found that wound complications were 6 times more likely in those with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels higher than 8% than in those with lower HbA1c levels (OR, 6.07; 95% CI, 1.12-33.0). In a similar study of 462 patients with diabetes, Hwang and colleagues27 found a higher likelihood of superficial SSIs in patients with HbA1c levels >8% (OR, 6.1; 95% CI, 1.6-23.4; P = .008). This association was also found in patients with a fasting blood glucose level of >200 mg/dL (OR, 9.2; 95% CI, 2.2-38.2; P = .038).

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is thought to account for 10% to 25% of all periprosthetic infections in the United States.28 Nasal colonization by this pathogen increases the risk for SSIs; however, decolonization protocols have proved useful in decreasing the rates of colonization. Moroski and colleagues29 assessed the efficacy of a preoperative 5-day course of intranasal mupirocin in 289 primary or revision TJA patients. Before surgery, 12 patients had positive MRSA cultures, and 44 had positive methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA) cultures. On day of surgery, a significant reduction in MRSA (P = .0073) and MSSA (P = .0341) colonization was noted. Rao and colleagues30 found that the infection rate decreased from 2.7% to 1.2% in 2284 TJA patients treated with a decolonization protocol (P = .009).

Intraoperative Measures

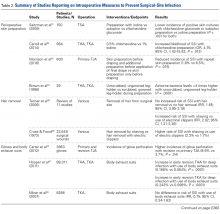

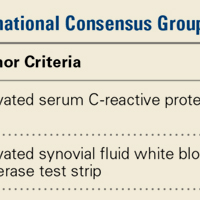

Cutaneous Preparation. The solutions used in perioperative skin preparation are similar to those used preoperatively: povidone-iodine, alcohol, and chlorhexidine. The efficacy of these preparations varies. Table 2 summarizes the studies on intraoperative measures for preventing SSIs.

The literature also highlights the importance of technique in incision-site preparation. In a prospective study, Morrison and colleagues33 randomly assigned 600 primary TJA patients to either (1) use of alcohol and povidone-iodine before draping, with additional preparation with iodine povacrylex (DuraPrep) and isopropyl alcohol before application of the final drape (300-patient intervention group) or (2) only use of alcohol and povidone-iodine before draping (300-patient control group). At the final follow-up, the incidence of SSI was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group (1.8% vs 6.5%; P = .015). In another study that assessed perioperative skin preparation methods, Brown and colleagues34 found that airborne bacteria levels in operating rooms were >4 times higher with patients whose legs were prepared by a scrubbed, gowned leg-holder than with patients whose legs were prepared by an unscrubbed, ungowned leg-holder (P = .0001).

Hair Removal. Although removing hair from surgical sites is common practice, the literature advocating it varies. A large comprehensive review35 revealed no increased risk of SSI with removing vs not removing hair (RR, 1.65; 95% CI, 0.85-3.19). On the other hand, some hair removal methods may affect the incidence of infection. For example, use of electric hair clippers is presumed to reduce the risk of SSIs, whereas traditional razors may compromise the epidermal barriers and create a pathway for bacterial colonization.5,36,37 In the aforementioned review,35 SSIs were more than twice as likely to occur with hair removed by shaving than with hair removed by electric clippers (RR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.21-3.36). Cruse and Foord38 found a higher rate of SSIs with hair removed by shaving than with hair removed by clipping (2.3% vs 1.7%). Most surgeons agree that, if given the choice, they would remove hair with electric clippers rather than razors.

Gloves. Almost all orthopedists double their gloves for TJA cases. Over several studies, the incidence of glove perforation during orthopedic procedures has ranged from 3.6% to 26%,39-41 depending on the operating room personnel and glove layering studied. Orthopedists must know this startling finding, as surgical glove perforation is associated with an increase in the rate of SSIs, from 1.7% to 5.7%.38 Carter and colleagues42 found the highest risk of glove perforation occurs when double-gloved attending surgeons, adult reconstruction fellows, and registered nurses initially assist during primary and revision TJA. In their study, outer and inner glove layers were perforated 2.5% of the time. All outer-layer perforations were noticed, but inner-layer perforations went unnoticed 81% of the time, which poses a potential hazard for both patients and healthcare personnel. In addition, there was a significant increase in the incidence of glove perforations for attending surgeons during revision TJA vs primary TJA (8.9% vs 3.7%; P = .04). This finding may be expected given the complexity of revision procedures, the presence of sharp bony and metal edges, and the longer operative times. Giving more attention to glove perforations during arthroplasties may mitigate the risk of SSI. As soon as a perforation is noticed, the glove should be removed and replaced.

Body Exhaust Suits. Early TJAs had infection rates approaching 10%.43 Bacterial-laden particles shed from surgical staff were postulated to be the cause,44,45 and this idea prompted the development of new technology, such as body exhaust suits, which have demonstrated up to a 20-fold reduction in airborne bacterial contamination and decreased incidence of deep infection, from 1% to 0.1%, as compared with conventional surgical attire.46 However, the efficacy of these suits was recently challenged. Hooper and colleagues47 assessed >88,000 TJA cases in the New Zealand Joint Registry and found a significant increase in early revision THA for deep infection with vs without use of body exhaust suits (0.186% vs 0.064%; P < .0001). The incidence of revision TKAs for deep infections with use of these suits was similar (0.243% vs 0.098%; P < .001). Many of the surgeons surveyed indicated their peripheral vision was limited by the suits, which may contribute to sterile field contamination. By contrast, Miner and colleagues48 were unable to determine an increased risk of SSI with use of body exhaust suits (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.34-1.62), though there was a trend toward more infections without suits. Moreover, these suits are effective in reducing mean air bacterial counts (P = .014), but it is not known if this method correlates with mean wound bacterial counts (r = –.011) and therefore increases the risk of SSI.49

Surgical Drapes. Surgical draping, including cloths, iodine-impregnated materials, and woven or unwoven materials, is the standard of care worldwide. The particular draping technique usually varies by surgeon. Plastic drapes are better barriers than cloth drapes, as found in a study by Blom and colleagues50: Bacterial growth rates were almost 10 times higher with use of wet woven cloth drapes than with plastic surgical drapes. These findings were supported in another, similar study by Blom and colleagues51: Wetting drapes with blood or normal saline enhanced bacterial penetration. In addition, wetting drapes with chlorhexidine or iodine reduced but did not eliminate bacterial penetration. Fairclough and colleagues52 emphasized that iodine-impregnated drapes reduced surgical-site bacterial contamination from 15% to 1.6%. However, a Cochrane review53 found these drapes had no effect on the SSI rate (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.06-1.66; P = .89), though the risk of infection was slightly higher with adhesive draping than with no drape (RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.02-1.48; P = .03).

Ventilation Flow. Laminar-airflow systems are widely used to prevent SSIs after TJA. Horizontal-flow and vertical-flow ventilation provides and maintains ultra-clean air in the operating room. Evans54 found the bacterial counts in the air and the wound were lower with laminar airflow than without this airflow. The amount of airborne bacterial colony-forming units and dust large enough to carry bacteria was reduced to 1 or 2 particles more than 2 μm/m3 with use of a typical laminar- airflow system. In comparing 3922 TKA patients in laminar-airflow operating rooms with 4133 patients in conventional rooms, Lidwell and colleagues46 found a significantly lower incidence of SSIs in patients in laminar-airflow operating rooms (0.6% vs 2.3%; P < .001).

Conversely, Miner and colleagues48 did not find a lower risk of SSI with laminar-airflow systems (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.75-3.31). In addition, in their analysis of >88,000 cases from the New Zealand Joint Registry, Hooper and colleagues47 found that the incidence of early infections was higher with laminar-airflow systems than with standard airflow systems for both TKA (0.193% vs 0.100%; P = .019) and THA (0.148% vs 0.061%; P < .001). They postulated that vertically oriented airflow may have transmitted contaminated particles into the surgical sites. Additional evidence may be needed to resolve these conflicting findings and determine whether clean-air practices provide significant clinical benefit in the operating room.

Staff Traffic Volume. When staff enters or exits the operating room or makes extra movements during a procedure, airflow near the wound is disturbed and no longer able to remove sufficient airborne pathogens from the sterile field. The laminar- airflow pattern may be disrupted each time the operating room doors open and close, potentially allowing airborne pathogens to be introduced near the patient. Lynch and colleagues55 found the operating room door opened almost 50 times per hour, and it took about 20 seconds to close each time. As a result, the door may remain open for up to 20 minutes per case, causing substantial airflow disruption and potentially ineffective removal of airborne bacterial particles. Similarly, Young and O’Regan56 found the operating room door opened about 19 times per hour and took 20 seconds to close each time. The theater door was open an estimated 10.7% of each hour of sterile procedure. Presence of more staff also increases airborne bacterial counts. Pryor and Messmer57 evaluated a cohort of 2864 patients to determine the effect of number of personnel in the operating theater on the incidence of SSIs. Infection rates were 6.27% with >17 different people entering the room and 1.52% with <9 different people entering the room. Restricting the number of people in the room may be one of the easiest and most efficient ways to prevent SSI.

Systemic Antibiotic Prophylaxis. Perioperative antibiotic use is vital in minimizing the risk of infection after TJA. The Surgical Care Improvement Project recommended beginning the first antimicrobial dose either within 60 minutes before surgical incision (for cephalosporin) or within 2 hours before incision (for vancomycin) and discontinuing the prophylactic antimicrobial agents within 24 hours after surgery ends.58,59 However, Gorenoi and colleagues60 were unable to recommend a way to select particular antibiotics, as they found no difference in the effectiveness of various antibiotic agents used in TKA. A systematic review by AlBuhairan and colleagues61 revealed that antibiotic prophylaxis (vs no prophylaxis) reduced the absolute risk of a SSI by 8% and the relative risk by 81% (P < 0.0001). These findings are supported by evidence of the efficacy of perioperative antibiotics in reducing the incidence of SSI.62,63 Antibiotic regimens should be based on susceptibility and availability, depending on hospital prevalence of infections. Even more, patients should receive prophylaxis in a timely manner. Finally, bacteriostatic antibiotics (vancomycin) should not be used on their own for preoperative prophylaxis.

Antibiotic Cement. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement (ALBC), which locally releases antimicrobials in high concentration, is often used in revision joint arthroplasty, but use in primary joint arthroplasty remains controversial. In a study of THA patients, Parvizi and colleagues64 found infection rates of 1.2% with 2.3% with and without use of ALBC, respectively. Other studies have had opposing results. Namba and colleagues65 evaluated 22,889 primary TKAs, 2030 (8.9%) of which used ALBC. The incidence of deep infection was significantly higher with ALBC than with regular bone cement (1.4% vs 0.7%; P = .002). In addition, a meta- analysis of >6500 primary TKA patients, by Zhou and colleagues,66 revealed no significant difference in the incidence of deep SSIs with use of ALBC vs regular cement (1.32% vs 1.89%; RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.43-1.33; P = .33). More evidence is needed to determine the efficacy of ALBC in primary TJA. International Consensus Meeting on Periprosthetic Joint Infection participants recommended use of ALBC in high-risk patients, including patients who are obese or immunosuppressed or have diabetes or a prior history of infection.67

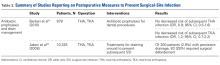

Postoperative Measures

Antibiotic Prophylaxis. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Dental Association (ADA) have suggestions for antibiotic prophylaxis for patients at increased risk for infection. As of 2015, the ADA no longer recommends antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with prosthetic joint implants,68 whereas the AAOS considers all patients with TJA to be at risk.69

Although recommendations exist, the actual risk of infection resulting from dental procedures and the role of antibiotic prophylaxis are not well defined. Berbari and colleagues71 found that antibiotic prophylaxis in high- or low-risk dental procedures did not decrease the risk of subsequent THA infection (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.5-1.6) or TKA infection (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.7-2.2). Moreover, the risk of infection was no higher for patients who had a prosthetic hip or knee and underwent a high- or low-risk dental procedure without antibiotic prophylaxis (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.4-1.6) than for similar patients who did not undergo a dental procedure (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-1.1). Some studies highlight the low level of evidence supporting antibiotic prophylaxis during dental procedures.72,73 However, there is no evidence of adverse effects of antibiotic prophylaxis. Given the potential high risk of infection after such procedures, a more robust body of evidence is needed to reach consensus.

Evacuation Drain Management. Prolonged use of surgical evacuation drains may be a risk factor for SSI. Therefore, early drain removal is paramount. Higher infection rates with prolonged drain use have been found in patients with persistent wound drainage, including malnourished, obese, and over-anticoagulated patients. Patients with wounds persistently draining for >1 week should undergo superficial wound irrigation and débridement. Jaberi and colleagues74 assessed 10,325 TJA patients and found that the majority of persistent drainage ceased within 1 week with use of less invasive measures, including oral antibiotics and local wound care. Furthermore, only 28% of patients with persistent drainage underwent surgical débridement. It is unclear if this practice alone is appropriate. Infection should always be suspected and treated aggressively, and cultures should be obtained from synovial fluid before antibiotics are started, unless there is an obvious superficial infection that does not require further work-up.67

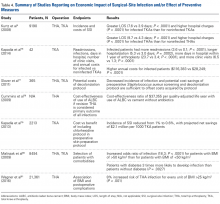

Economic Impact

SSIs remain a significant healthcare issue, and the social and financial costs are staggering. Without appropriate measures in place, these complications will place a larger burden on the healthcare system primarily as a result of longer hospital stays, multiple procedures, and increased resource utilization.75 Given the risk of progression to prosthetic joint infection, early preventive interventions must be explored.

Improved patient selection may be an important factor in reducing SSIs. In an analysis of 8494 joint arthroplasties, Malinzak and colleagues80 noted that patients with a BMI of >50 kg/m2 had an increased OR of infection of 21.3 compared to those with BMI <50 kg/m2. Wagner and colleagues81 analyzed 21,361 THAs and found that, for every BMI unit over 25 kg/m2, there was an 8% increased risk of joint infection (P < .001). Although it is unknown if there is an association between reduction in preoperative BMI and reduction in postoperative complication risk, it may still be worthwhile and cost-effective to modify this and similar risk factors before elective procedures.

Market forces are becoming a larger consideration in healthcare and are being driven by provider competition.82 Treatment outcomes, quality of care, and healthcare prices have gained attention as a means of estimating potential costs.83 In 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) advanced the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative, which aimed to provide better coordinated care of higher quality and lower cost.84 This led to development of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) program, which gives beneficiaries flexibility in choosing services and ensures that providers adhere to required standards. During its 5-year test period beginning in 2016, the CJR program is projected to save CMS $153 million.84 Under this program, the institution where TJA is performed is responsible for all the costs of related care from time of surgery through 90 days after hospital discharge—which is known as an “episode of care.” If the cost incurred during an episode exceeds an established target cost (as determined by CMS), the hospital must repay Medicare the difference. Conversely, if the cost of an episode is less than the established target cost, the hospital is rewarded with the difference. Bundling payments for a single episode of care in this manner is thought to incentivize providers and hospitals to give patients more comprehensive and coordinated care. Given the substantial economic burden associated with joint arthroplasty infections, it is imperative for orthopedists to establish practical and cost-effective strategies that can prevent these disastrous complications.

Conclusion

SSIs are a devastating burden to patients, surgeons, and other healthcare providers. In recent years, new discoveries and innovations have helped mitigate the incidence of these complications of THA and TKA. However, the incidence of SSIs may rise with the increasing use of TJAs and with the development of new drug-resistant pathogens. In addition, the increasing number of TJAs performed on overweight and high-risk patients means the costs of postoperative infections will be substantial. With new reimbursement models in place, hospitals and providers are being held more accountable for the care they deliver during and after TJA. Consequently, more emphasis should be placed on techniques that are proved to minimize the incidence of SSIs.

1. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System report, data summary from January 1992 through June 2004, issued October 2004. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32(8):470-485.

2. Bozic KJ, Ries MD. The impact of infection after total hip arthroplasty on hospital and surgeon resource utilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1746-1751.

3. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Watson H, Schmier JK, Parvizi J. Economic burden of periprosthetic joint infection in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(8 suppl):61-65.e61.

4. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Schmier J, Ong KL, Zhao K, Parvizi J. Infection burden for hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2008;23(7):984-991.

5. Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(4):250-278.

6. Berrios-Torres SI. Evidence-based update to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection: developmental process. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2016;17(2):256-261.

7 Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27(2):97-132.

8. Marchetti MG, Kampf G, Finzi G, Salvatorelli G. Evaluation of the bactericidal effect of five products for surgical hand disinfection according to prEN 12054 and prEN 12791. J Hosp Infect. 2003;54(1):63-67.

9. Reichman DE, Greenberg JA. Reducing surgical site infections: a review. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2009;2(4):212-221.

10. Hayek LJ, Emerson JM, Gardner AM. A placebo-controlled trial of the effect of two preoperative baths or showers with chlorhexidine detergent on postoperative wound infection rates. J Hosp Infect. 1987;10(2):165-172.

11. Murray MR, Saltzman MD, Gryzlo SM, Terry MA, Woodward CC, Nuber GW. Efficacy of preoperative home use of 2% chlorhexidine gluconate cloth before shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(6):928-933.

12. Darouiche RO, Wall MJ Jr, Itani KM, et al. Chlorhexidine-alcohol versus povidone-iodine for surgical-site antisepsis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(1):18-26.

13. Zywiel MG, Daley JA, Delanois RE, Naziri Q, Johnson AJ, Mont MA. Advance pre-operative chlorhexidine reduces the incidence of surgical site infections in knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2011;35(7):1001-1006.

14. Kapadia BH, Johnson AJ, Daley JA, Issa K, Mont MA. Pre-admission cutaneous chlorhexidine preparation reduces surgical site infections in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(3):490-493.

15. Johnson AJ, Kapadia BH, Daley JA, Molina CB, Mont MA. Chlorhexidine reduces infections in knee arthroplasty. J Knee Surg. 2013;26(3):213-218.

16. Kapadia BH, Elmallah RK, Mont MA. A randomized, clinical trial of preadmission chlorhexidine skin preparation for lower extremity total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(12):2856-2861.

17. Mainous MR, Deitch EA. Nutrition and infection. Surg Clin North Am. 1994;74(3):659-676.

18. Greene KA, Wilde AH, Stulberg BN. Preoperative nutritional status of total joint patients. Relationship to postoperative wound complications. J Arthroplasty. 1991;6(4):321-325.

19. Del Savio GC, Zelicof SB, Wexler LM, et al. Preoperative nutritional status and outcome of elective total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;(326):153-161.

20. Alfargieny R, Bodalal Z, Bendardaf R, El-Fadli M, Langhi S. Nutritional status as a predictive marker for surgical site infection in total joint arthroplasty. Avicenna J Med. 2015;5(4):117-122.

21. Bridges SL Jr, Lopez-Mendez A, Han KH, Tracy IC, Alarcon GS. Should methotrexate be discontinued before elective orthopedic surgery in patients with rheumatoid arthritis? J Rheumatol. 1991;18(7):984-988.

22. Silverstein P. Smoking and wound healing. Am J Med. 1992;93(1A):22S-24S.

23. Sørensen LT. Wound healing and infection in surgery. The clinical impact of smoking and smoking cessation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2012;147(4):373-383.

24. Wong J, Lam DP, Abrishami A, Chan MT, Chung F. Short-term preoperative smoking cessation and postoperative complications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Anaesth. 2012;59(3):268-279.

25. Pugely AJ, Martin CT, Gao Y, Schweizer ML, Callaghan JJ. The incidence of and risk factors for 30-day surgical site infections following primary and revision total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(9 suppl):47-50.

26. Han HS, Kang SB. Relations between long-term glycemic control and postoperative wound and infectious complications after total knee arthroplasty in type 2 diabetics. Clin Orthop Surg. 2013;5(2):118-123.

27. Hwang JS, Kim SJ, Bamne AB, Na YG, Kim TK. Do glycemic markers predict occurrence of complications after total knee arthroplasty in patients with diabetes? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(5):1726-1731.

28. Whiteside LA, Peppers M, Nayfeh TA, Roy ME. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in TKA treated with revision and direct intra-articular antibiotic infusion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(1):26-33.

29. Moroski NM, Woolwine S, Schwarzkopf R. Is preoperative staphylococcal decolonization efficient in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(3):444-446.

30. Rao N, Cannella BA, Crossett LS, Yates AJ Jr, McGough RL 3rd, Hamilton CW. Preoperative screening/decolonization for Staphylococcus aureus to prevent orthopedic surgical site infection: prospective cohort study with 2-year follow-up. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1501-1507.

31. Saltzman MD, Nuber GW, Gryzlo SM, Marecek GS, Koh JL. Efficacy of surgical preparation solutions in shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(8):1949-1953.

32. Carroll K, Dowsey M, Choong P, Peel T. Risk factors for superficial wound complications in hip and knee arthroplasty. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(2):130-135.

33. Morrison TN, Chen AF, Taneja M, Kucukdurmaz F, Rothman RH, Parvizi J. Single vs repeat surgical skin preparations for reducing surgical site infection after total joint arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized, double-blinded study. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31(6):1289-1294.

34. Brown AR, Taylor GJ, Gregg PJ. Air contamination during skin preparation and draping in joint replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78(1):92-94.

35. Tanner J, Woodings D, Moncaster K. Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004122.

36. Mishriki SF, Law DJ, Jeffery PJ. Factors affecting the incidence of postoperative wound infection. J Hosp Infect. 1990;16(3):223-230.

37. Harrop JS, Styliaras JC, Ooi YC, Radcliff KE, Vaccaro AR, Wu C. Contributing factors to surgical site infections. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2012;20(2):94-101.

38. Cruse PJ, Foord R. A five-year prospective study of 23,649 surgical wounds. Arch Surg. 1973;107(2):206-210.

39. Laine T, Aarnio P. Glove perforation in orthopaedic and trauma surgery. A comparison between single, double indicator gloving and double gloving with two regular gloves. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(6):898-900.

40. Ersozlu S, Sahin O, Ozgur AF, Akkaya T, Tuncay C. Glove punctures in major and minor orthopaedic surgery with double gloving. Acta Orthop Belg. 2007;73(6):760-764.

41. Chan KY, Singh VA, Oun BH, To BH. The rate of glove perforations in orthopaedic procedures: single versus double gloving. A prospective study. Med J Malaysia. 2006;61(suppl B):3-7.

42. Carter AH, Casper DS, Parvizi J, Austin MS. A prospective analysis of glove perforation in primary and revision total hip and total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2012;27(7):1271-1275.

43. Charnley J. A clean-air operating enclosure. Br J Surg. 1964;51:202-205.

44. Whyte W, Hodgson R, Tinkler J. The importance of airborne bacterial contamination of wounds. J Hosp Infect. 1982;3(2):123-135.

45. Owers KL, James E, Bannister GC. Source of bacterial shedding in laminar flow theatres. J Hosp Infect. 2004;58(3):230-232.

46. Lidwell OM, Lowbury EJ, Whyte W, Blowers R, Stanley SJ, Lowe D. Effect of ultraclean air in operating rooms on deep sepsis in the joint after total hip or knee replacement: a randomised study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1982;285(6334):10-14.

47. Hooper GJ, Rothwell AG, Frampton C, Wyatt MC. Does the use of laminar flow and space suits reduce early deep infection after total hip and knee replacement? The ten-year results of the New Zealand Joint Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(1):85-90.

48. Miner AL, Losina E, Katz JN, Fossel AH, Platt R. Deep infection after total knee replacement: impact of laminar airflow systems and body exhaust suits in the modern operating room. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(2):222-226.

49. Der Tavitian J, Ong SM, Taub NA, Taylor GJ. Body-exhaust suit versus occlusive clothing. A randomised, prospective trial using air and wound bacterial counts. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(4):490-494.

50. Blom A, Estela C, Bowker K, MacGowan A, Hardy JR. The passage of bacteria through surgical drapes. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2000;82(6):405-407.

51. Blom AW, Gozzard C, Heal J, Bowker K, Estela CM. Bacterial strike-through of re-usable surgical drapes: the effect of different wetting agents. J Hosp Infect. 2002;52(1):52-55.

52. Fairclough JA, Johnson D, Mackie I. The prevention of wound contamination by skin organisms by the pre-operative application of an iodophor impregnated plastic adhesive drape. J Int Med Res. 1986;14(2):105-109.

53. Webster J, Alghamdi AA. Use of plastic adhesive drapes during surgery for preventing surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(4):CD006353.

54. Evans RP. Current concepts for clean air and total joint arthroplasty: laminar airflow and ultraviolet radiation: a systematic review. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(4):945-953.

55. Lynch RJ, Englesbe MJ, Sturm L, et al. Measurement of foot traffic in the operating room: implications for infection control. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(1):45-52.

56. Young RS, O’Regan DJ. Cardiac surgical theatre traffic: time for traffic calming measures? Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;10(4):526-529.

57. Pryor F, Messmer PR. The effect of traffic patterns in the OR on surgical site infections. AORN J. 1998;68(4):649-660.

58. Bratzler DW, Houck PM; Surgical Infection Prevention Guidelines Writers Workgroup, American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Association of Critical Care Nurses, et al. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(12):1706-1715.

59. Rosenberger LH, Politano AD, Sawyer RG. The Surgical Care Improvement Project and prevention of post-operative infection, including surgical site infection. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2011;12(3):163-168.

60. Gorenoi V, Schonermark MP, Hagen A. Prevention of infection after knee arthroplasty. GMS Health Technol Assess. 2010;6:Doc10.

61. AlBuhairan B, Hind D, Hutchinson A. Antibiotic prophylaxis for wound infections in total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2008;90(7):915-919.

62. Bratzler DW, Houck PM; Surgical Infection Prevention Guideline Writers Workgroup. Antimicrobial prophylaxis for surgery: an advisory statement from the National Surgical Infection Prevention Project. Am J Surg. 2005;189(4):395-404.

63. Quenon JL, Eveillard M, Vivien A, et al. Evaluation of current practices in surgical antimicrobial prophylaxis in primary total hip prosthesis—a multicentre survey in private and public French hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 2004;56(3):202-207.

64. Parvizi J, Saleh KJ, Ragland PS, Pour AE, Mont MA. Efficacy of antibiotic-impregnated cement in total hip replacement. Acta Orthop. 2008;79(3):335-341.

65. Namba RS, Chen Y, Paxton EW, Slipchenko T, Fithian DC. Outcomes of routine use of antibiotic-loaded cement in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 suppl):44-47.

66. Zhou Y, Li L, Zhou Q, et al. Lack of efficacy of prophylactic application of antibiotic-loaded bone cement for prevention of infection in primary total knee arthroplasty: results of a meta-analysis. Surg Infect (Larchmt). 2015;16(2):183-187.

67. Leopold SS. Consensus statement from the International Consensus Meeting on Periprosthetic Joint Infection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(12):3731-3732.

68. Sollecito TP, Abt E, Lockhart PB, et al. The use of prophylactic antibiotics prior to dental procedures in patients with prosthetic joints: evidence-based clinical practice guideline for dental practitioners—a report of the American Dental Association Council on Scientific Affairs. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(1):11-16.e18.

69. Watters W 3rd, Rethman MP, Hanson NB, et al. Prevention of orthopaedic implant infection in patients undergoing dental procedures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2013;21(3):180-189.

70. Merchant VA; American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Dental Association. The new AAOS/ADA clinical practice guidelines for management of patients with prosthetic joint replacements. J Mich Dent Assoc. 2013;95(2):16, 74.

71. Berbari EF, Osmon DR, Carr A, et al. Dental procedures as risk factors for prosthetic hip or knee infection: a hospital-based prospective case–control study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(1):8-16.

72. Little JW, Jacobson JJ, Lockhart PB; American Academy of Oral Medicine. The dental treatment of patients with joint replacements: a position paper from the American Academy of Oral Medicine. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(6):667-671.

73. Curry S, Phillips H. Joint arthroplasty, dental treatment, and antibiotics: a review. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17(1):111-113.

74. Jaberi FM, Parvizi J, Haytmanek CT, Joshi A, Purtill J. Procrastination of wound drainage and malnutrition affect the outcome of joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(6):1368-1371.

75. Stone PW. Economic burden of healthcare-associated infections: an American perspective. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2009;9(5):417-422.

76. Kapadia BH, McElroy MJ, Issa K, Johnson AJ, Bozic KJ, Mont MA. The economic impact of periprosthetic infections following total knee arthroplasty at a specialized tertiary-care center. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):929-932.

77. Slover J, Haas JP, Quirno M, Phillips MS, Bosco JA 3rd. Cost-effectiveness of a Staphylococcus aureus screening and decolonization program for high-risk orthopedic patients. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(3):360-365.

78. Cummins JS, Tomek IM, Kantor SR, Furnes O, Engesaeter LB, Finlayson SR. Cost-effectiveness of antibiotic-impregnated bone cement used in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(3):634-641.

79. Kapadia BH, Johnson AJ, Issa K, Mont MA. Economic evaluation of chlorhexidine cloths on healthcare costs due to surgical site infections following total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1061-1065.

80. Malinzak RA, Ritter MA, Berend ME, Meding JB, Olberding EM, Davis KE. Morbidly obese, diabetic, younger, and unilateral joint arthroplasty patients have elevated total joint arthroplasty infection rates. J Arthroplasty. 2009;24(6 suppl):84-88.

81. Wagner ER, Kamath AF, Fruth KM, Harmsen WS, Berry DJ. Effect of body mass index on complications and reoperations after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(3):169-179.

82 Broex EC, van Asselt AD, Bruggeman CA, van Tiel FH. Surgical site infections: how high are the costs? J Hosp Infect. 2009;72(3):193-201.

83. Anderson DJ, Kirkland KB, Kaye KS, et al. Underresourced hospital infection control and prevention programs: penny wise, pound foolish? Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(7):767-773.

84. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), HHS. Medicare program; comprehensive care for joint replacement payment model for acute care hospitals furnishing lower extremity joint replacement services. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2015;80(226):73273-73554.

Take-Home Points

- SSIs after TJA pose a substantial burden on patients, surgeons, and the healthcare system.

- While different forms of preoperative skin preparation have shown varying outcomes after TJA, the importance of preoperative patient optimization (nutritional status, immune function, etc) cannot be overstated.

- Intraoperative infection prevention measures include cutaneous preparation, gloving, body exhaust suits, surgical drapes, OR staff traffic and ventilation flow, and antibiotic-loaded cement.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures in TJA patients continues to remain a controversial issue with conflicting recommendations.

- SSIs have considerable financial costs and require increased resource utilization. Given the significant economic burden associated with TJA infections, it is imperative for orthopedists to establish practical and cost-effective strategies to prevent these devastating complications.

Surgical-site infection (SSI), a potentially devastating complication of lower extremity total joint arthroplasty (TJA), is estimated to occur in 1% to 2.5% of cases annually.1 Infection after TJA places a significant burden on patients, surgeons, and the healthcare system. Revision procedures that address infection after total hip arthroplasty (THA) are associated with more hospitalizations, more operations, longer hospital stay, and higher outpatient costs in comparison with primary THAs and revision surgeries for aseptic loosening.2 If left untreated, a SSI can go deeper into the joint and develop into a periprosthetic infection, which can be disastrous and costly. A periprosthetic joint infection study that used 2001 to 2009 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data found that the cost of revision procedures increased to $560 million from $320 million, and was projected to reach $1.62 billion by 2020.3 Furthermore, society incurs indirect costs as a result of patient disability and loss of wages and productivity.2 Therefore, the issue of infection after TJA is even more crucial in our cost-conscious healthcare environment.

Patient optimization, advances in surgical technique, sterile protocol, and operative procedures have been effective in reducing bacterial counts at incision sites and minimizing SSIs. As a result, infection rates have leveled off after rising for a decade.4 Although infection prevention modalities have their differences, routine use is fundamental and recommended by the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee.5 Furthermore, both the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee6,7 recently updated their SSI prevention guidelines by incorporating evidence-based methodology, an element missing from earlier recommendations.

The etiologies of postoperative SSIs have been discussed ad nauseam, but there are few reports summarizing the literature on infection prevention modalities. In this review, we identify and examine SSI prevention strategies as they relate to lower extremity TJA. Specifically, we discuss the literature on the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative actions that can be taken to reduce the incidence of SSIs after TJA. We also highlight the economic implications of SSIs that occur after TJA.

Methods

For this review, we performed a literature search with PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Scopus. We looked for reports published between the inception of each database and July 2016. Combinations of various search terms were used: surgical site, infection, total joint arthroplasty, knee, hip, preoperative, intraoperative, perioperative, postoperative, preparation, nutrition, ventilation, antibiotic, body exhaust suit, gloves, drain, costs, economic, and payment.

Our search identified 195 abstracts. Drs. Mistry and Chughtai reviewed these to determine which articles were relevant. For any uncertainties, consensus was reached with the help of Dr. Delanois. Of the 195 articles, 103 were potentially relevant, and 54 of the 103 were excluded for being not relevant to preventing SSIs after TJA or for being written in a language other than English. The references in the remaining articles were assessed, and those with potentially relevant titles were selected for abstract review. This step provided another 35 articles. After all exclusions, 48 articles remained. We discuss these in the context of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative measures and economic impact.

Results

Preoperative Measures

Skin Preparation. Preoperative skin preparation methods include standard washing and rinsing, antiseptic soaps, and iodine-based or chlorhexidine gluconate-based antiseptic showers or skin cloths. Iodine-based antiseptics are effective against a wide range of Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, fungi, and viruses. These agents penetrate the cell wall, oxidize the microbial contents, and replace those contents with free iodine molecules.8 Iodophors are free iodine molecules associated with a polymer (eg, polyvinylpyrrolidone); the iodophor povidone-iodine is bactericidal.9 Chlorhexidine gluconate-based solutions are effective against many types of yeast, Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, and a wide variety of viruses.9 Both solutions are useful. Patients with an allergy to iodine can use chlorhexidine. Table 1 summarizes the studies on preoperative measures for preventing SSIs.

There is no shortage of evidence of the efficacy of these antiseptics in minimizing the incidence of SSIs. Hayek and colleagues10 prospectively analyzed use of different preoperative skin preparation methods in 2015 patients. Six weeks after surgery, the infection rate was significantly lower with use of chlorhexidine than with use of an unmedicated bar of soap or placebo cloth (9% vs 11.7% and 12.8%, respectively; P < .05). In a study of 100 patients, Murray and colleagues11 found the overall bacterial culture rate was significantly lower for those who used a 2% chlorhexidine gluconate cloth before shoulder surgery than for those who took a standard shower with soap (66% vs 94%; P = .0008). Darouiche and colleagues12 found the overall SSI rate was significantly lower for 409 surgical patients prepared with chlorhexidine-alcohol than for 440 prepared with povidone-iodine (9.5% vs 16.1%; P = .004; relative risk [RR], 0.59; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.41-0.85).

Chlorhexidine gluconate-impregnated cloths have also had promising results, which may be attributed to general ease of use and potentially improved patient adherence. Zywiel and colleagues13 reported no SSIs in 136 patients who used these cloths at home before total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and 21 SSIs (3.0%) in 711 patients who did not use the cloths. In a study of 2545 THA patients, Kapadia and colleagues14 noted a significantly lower incidence of SSIs with at-home preoperative use of chlorhexidine cloths than with only in-hospital perioperative skin preparation (0.5% vs 1.7%; P = .04). In 2293 TKAs, Johnson and colleagues15 similarly found a lower incidence of SSIs with at-home preoperative use of chlorhexidine cloths (0.6% vs 2.2%; P = .02). In another prospective, randomized trial, Kapadia and colleagues16 compared 275 patients who used chlorhexidine cloths the night before and the morning of lower extremity TJA surgery with 279 patients who underwent standard-of-care preparation (preadmission bathing with antibacterial soap and water). The chlorhexidine cohort had a lower overall incidence of infection (0.4% vs 2.9%; P = .049), and the standard-of-care cohort had a stronger association with infection (odds ratio [OR], 8.15; 95% CI, 1.01-65.6).

Patient Optimization. Poor nutritional status may compromise immune function, potentially resulting in delayed healing, increased risk of infection, and, ultimately, negative postoperative outcomes. Malnutrition can be diagnosed on the basis of a prealbumin level of <15 mg/dL (normal, 15-30 mg/dL), a serum albumin level of <3.4 g/dL (normal, 3.4-5.4 g/dL), or a total lymphocyte count under 1200 cells/μL (normal, 3900-10,000 cells/μL).17-19 Greene and colleagues18 found that patients with preoperative malnutrition had up to a 7-fold higher rate of infection after TJA. In a study of 135 THAs and TKAs, Alfargieny and colleagues20 found preoperative serum albumin was the only nutritional biomarker predictive of SSI (P = .011). Furthermore, patients who take immunomodulating medications (eg, for inflammatory arthropathies) should temporarily discontinue them before surgery in order to lower their risk of infection.21

Smoking is well established as a major risk factor for poor outcomes after surgery. It is postulated that the vasoconstrictive effects of nicotine and the hypoxic effects of carbon monoxide contribute to poor wound healing.22 In a meta-analysis of 4 studies, Sørensen23 found smokers were at increased risk for wound complications (OR, 2.27; 95% CI, 1.82-2.84), delayed wound healing and dehiscence (OR, 2.07; 95% CI, 1.53-2.81), and infection (OR, 1.79; 95% CI, 1.57-2.04). Moreover, smoking cessation decreased the incidence of SSIs (OR, 0.43; 95% CI, 0.21-0.85). A meta- analysis by Wong and colleagues24 revealed an inflection point for improved outcomes in patients who abstained from smoking for at least 4 weeks before surgery. Risk of infection was lower for these patients than for current smokers (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.56-0.84).

Other comorbidities contribute to SSIs as well. In their analysis of American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program registry data on 25,235 patients who underwent primary and revision lower extremity TJA, Pugely and colleagues25 found that, in the primary TJA cohort, body mass index (BMI) of >40 kg/m2 (OR, 1.9; 95% CI, 1.3-2.9), electrolyte disturbance (OR, 2.4; 95% CI, 1.0-6.0), and hypertension diagnosis (OR, 1.5; 95% CI, 1.1-2.0) increased the risk of SSI within 30 days. Furthermore, diabetes mellitus delays collagen synthesis, impairs lymphocyte function, and impairs wound healing, which may lead to poor recovery and higher risk of infection.26 In a study of 167 TKAs performed in 115 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, Han and Kang26 found that wound complications were 6 times more likely in those with hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels higher than 8% than in those with lower HbA1c levels (OR, 6.07; 95% CI, 1.12-33.0). In a similar study of 462 patients with diabetes, Hwang and colleagues27 found a higher likelihood of superficial SSIs in patients with HbA1c levels >8% (OR, 6.1; 95% CI, 1.6-23.4; P = .008). This association was also found in patients with a fasting blood glucose level of >200 mg/dL (OR, 9.2; 95% CI, 2.2-38.2; P = .038).

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is thought to account for 10% to 25% of all periprosthetic infections in the United States.28 Nasal colonization by this pathogen increases the risk for SSIs; however, decolonization protocols have proved useful in decreasing the rates of colonization. Moroski and colleagues29 assessed the efficacy of a preoperative 5-day course of intranasal mupirocin in 289 primary or revision TJA patients. Before surgery, 12 patients had positive MRSA cultures, and 44 had positive methicillin-sensitive S aureus (MSSA) cultures. On day of surgery, a significant reduction in MRSA (P = .0073) and MSSA (P = .0341) colonization was noted. Rao and colleagues30 found that the infection rate decreased from 2.7% to 1.2% in 2284 TJA patients treated with a decolonization protocol (P = .009).

Intraoperative Measures

Cutaneous Preparation. The solutions used in perioperative skin preparation are similar to those used preoperatively: povidone-iodine, alcohol, and chlorhexidine. The efficacy of these preparations varies. Table 2 summarizes the studies on intraoperative measures for preventing SSIs.

The literature also highlights the importance of technique in incision-site preparation. In a prospective study, Morrison and colleagues33 randomly assigned 600 primary TJA patients to either (1) use of alcohol and povidone-iodine before draping, with additional preparation with iodine povacrylex (DuraPrep) and isopropyl alcohol before application of the final drape (300-patient intervention group) or (2) only use of alcohol and povidone-iodine before draping (300-patient control group). At the final follow-up, the incidence of SSI was significantly lower in the intervention group than in the control group (1.8% vs 6.5%; P = .015). In another study that assessed perioperative skin preparation methods, Brown and colleagues34 found that airborne bacteria levels in operating rooms were >4 times higher with patients whose legs were prepared by a scrubbed, gowned leg-holder than with patients whose legs were prepared by an unscrubbed, ungowned leg-holder (P = .0001).

Hair Removal. Although removing hair from surgical sites is common practice, the literature advocating it varies. A large comprehensive review35 revealed no increased risk of SSI with removing vs not removing hair (RR, 1.65; 95% CI, 0.85-3.19). On the other hand, some hair removal methods may affect the incidence of infection. For example, use of electric hair clippers is presumed to reduce the risk of SSIs, whereas traditional razors may compromise the epidermal barriers and create a pathway for bacterial colonization.5,36,37 In the aforementioned review,35 SSIs were more than twice as likely to occur with hair removed by shaving than with hair removed by electric clippers (RR, 2.02; 95% CI, 1.21-3.36). Cruse and Foord38 found a higher rate of SSIs with hair removed by shaving than with hair removed by clipping (2.3% vs 1.7%). Most surgeons agree that, if given the choice, they would remove hair with electric clippers rather than razors.

Gloves. Almost all orthopedists double their gloves for TJA cases. Over several studies, the incidence of glove perforation during orthopedic procedures has ranged from 3.6% to 26%,39-41 depending on the operating room personnel and glove layering studied. Orthopedists must know this startling finding, as surgical glove perforation is associated with an increase in the rate of SSIs, from 1.7% to 5.7%.38 Carter and colleagues42 found the highest risk of glove perforation occurs when double-gloved attending surgeons, adult reconstruction fellows, and registered nurses initially assist during primary and revision TJA. In their study, outer and inner glove layers were perforated 2.5% of the time. All outer-layer perforations were noticed, but inner-layer perforations went unnoticed 81% of the time, which poses a potential hazard for both patients and healthcare personnel. In addition, there was a significant increase in the incidence of glove perforations for attending surgeons during revision TJA vs primary TJA (8.9% vs 3.7%; P = .04). This finding may be expected given the complexity of revision procedures, the presence of sharp bony and metal edges, and the longer operative times. Giving more attention to glove perforations during arthroplasties may mitigate the risk of SSI. As soon as a perforation is noticed, the glove should be removed and replaced.

Body Exhaust Suits. Early TJAs had infection rates approaching 10%.43 Bacterial-laden particles shed from surgical staff were postulated to be the cause,44,45 and this idea prompted the development of new technology, such as body exhaust suits, which have demonstrated up to a 20-fold reduction in airborne bacterial contamination and decreased incidence of deep infection, from 1% to 0.1%, as compared with conventional surgical attire.46 However, the efficacy of these suits was recently challenged. Hooper and colleagues47 assessed >88,000 TJA cases in the New Zealand Joint Registry and found a significant increase in early revision THA for deep infection with vs without use of body exhaust suits (0.186% vs 0.064%; P < .0001). The incidence of revision TKAs for deep infections with use of these suits was similar (0.243% vs 0.098%; P < .001). Many of the surgeons surveyed indicated their peripheral vision was limited by the suits, which may contribute to sterile field contamination. By contrast, Miner and colleagues48 were unable to determine an increased risk of SSI with use of body exhaust suits (RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.34-1.62), though there was a trend toward more infections without suits. Moreover, these suits are effective in reducing mean air bacterial counts (P = .014), but it is not known if this method correlates with mean wound bacterial counts (r = –.011) and therefore increases the risk of SSI.49

Surgical Drapes. Surgical draping, including cloths, iodine-impregnated materials, and woven or unwoven materials, is the standard of care worldwide. The particular draping technique usually varies by surgeon. Plastic drapes are better barriers than cloth drapes, as found in a study by Blom and colleagues50: Bacterial growth rates were almost 10 times higher with use of wet woven cloth drapes than with plastic surgical drapes. These findings were supported in another, similar study by Blom and colleagues51: Wetting drapes with blood or normal saline enhanced bacterial penetration. In addition, wetting drapes with chlorhexidine or iodine reduced but did not eliminate bacterial penetration. Fairclough and colleagues52 emphasized that iodine-impregnated drapes reduced surgical-site bacterial contamination from 15% to 1.6%. However, a Cochrane review53 found these drapes had no effect on the SSI rate (RR, 1.03; 95% CI, 0.06-1.66; P = .89), though the risk of infection was slightly higher with adhesive draping than with no drape (RR, 1.23; 95% CI, 1.02-1.48; P = .03).

Ventilation Flow. Laminar-airflow systems are widely used to prevent SSIs after TJA. Horizontal-flow and vertical-flow ventilation provides and maintains ultra-clean air in the operating room. Evans54 found the bacterial counts in the air and the wound were lower with laminar airflow than without this airflow. The amount of airborne bacterial colony-forming units and dust large enough to carry bacteria was reduced to 1 or 2 particles more than 2 μm/m3 with use of a typical laminar- airflow system. In comparing 3922 TKA patients in laminar-airflow operating rooms with 4133 patients in conventional rooms, Lidwell and colleagues46 found a significantly lower incidence of SSIs in patients in laminar-airflow operating rooms (0.6% vs 2.3%; P < .001).

Conversely, Miner and colleagues48 did not find a lower risk of SSI with laminar-airflow systems (RR, 1.57; 95% CI, 0.75-3.31). In addition, in their analysis of >88,000 cases from the New Zealand Joint Registry, Hooper and colleagues47 found that the incidence of early infections was higher with laminar-airflow systems than with standard airflow systems for both TKA (0.193% vs 0.100%; P = .019) and THA (0.148% vs 0.061%; P < .001). They postulated that vertically oriented airflow may have transmitted contaminated particles into the surgical sites. Additional evidence may be needed to resolve these conflicting findings and determine whether clean-air practices provide significant clinical benefit in the operating room.

Staff Traffic Volume. When staff enters or exits the operating room or makes extra movements during a procedure, airflow near the wound is disturbed and no longer able to remove sufficient airborne pathogens from the sterile field. The laminar- airflow pattern may be disrupted each time the operating room doors open and close, potentially allowing airborne pathogens to be introduced near the patient. Lynch and colleagues55 found the operating room door opened almost 50 times per hour, and it took about 20 seconds to close each time. As a result, the door may remain open for up to 20 minutes per case, causing substantial airflow disruption and potentially ineffective removal of airborne bacterial particles. Similarly, Young and O’Regan56 found the operating room door opened about 19 times per hour and took 20 seconds to close each time. The theater door was open an estimated 10.7% of each hour of sterile procedure. Presence of more staff also increases airborne bacterial counts. Pryor and Messmer57 evaluated a cohort of 2864 patients to determine the effect of number of personnel in the operating theater on the incidence of SSIs. Infection rates were 6.27% with >17 different people entering the room and 1.52% with <9 different people entering the room. Restricting the number of people in the room may be one of the easiest and most efficient ways to prevent SSI.

Systemic Antibiotic Prophylaxis. Perioperative antibiotic use is vital in minimizing the risk of infection after TJA. The Surgical Care Improvement Project recommended beginning the first antimicrobial dose either within 60 minutes before surgical incision (for cephalosporin) or within 2 hours before incision (for vancomycin) and discontinuing the prophylactic antimicrobial agents within 24 hours after surgery ends.58,59 However, Gorenoi and colleagues60 were unable to recommend a way to select particular antibiotics, as they found no difference in the effectiveness of various antibiotic agents used in TKA. A systematic review by AlBuhairan and colleagues61 revealed that antibiotic prophylaxis (vs no prophylaxis) reduced the absolute risk of a SSI by 8% and the relative risk by 81% (P < 0.0001). These findings are supported by evidence of the efficacy of perioperative antibiotics in reducing the incidence of SSI.62,63 Antibiotic regimens should be based on susceptibility and availability, depending on hospital prevalence of infections. Even more, patients should receive prophylaxis in a timely manner. Finally, bacteriostatic antibiotics (vancomycin) should not be used on their own for preoperative prophylaxis.

Antibiotic Cement. Antibiotic-loaded bone cement (ALBC), which locally releases antimicrobials in high concentration, is often used in revision joint arthroplasty, but use in primary joint arthroplasty remains controversial. In a study of THA patients, Parvizi and colleagues64 found infection rates of 1.2% with 2.3% with and without use of ALBC, respectively. Other studies have had opposing results. Namba and colleagues65 evaluated 22,889 primary TKAs, 2030 (8.9%) of which used ALBC. The incidence of deep infection was significantly higher with ALBC than with regular bone cement (1.4% vs 0.7%; P = .002). In addition, a meta- analysis of >6500 primary TKA patients, by Zhou and colleagues,66 revealed no significant difference in the incidence of deep SSIs with use of ALBC vs regular cement (1.32% vs 1.89%; RR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.43-1.33; P = .33). More evidence is needed to determine the efficacy of ALBC in primary TJA. International Consensus Meeting on Periprosthetic Joint Infection participants recommended use of ALBC in high-risk patients, including patients who are obese or immunosuppressed or have diabetes or a prior history of infection.67

Postoperative Measures

Antibiotic Prophylaxis. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) and the American Dental Association (ADA) have suggestions for antibiotic prophylaxis for patients at increased risk for infection. As of 2015, the ADA no longer recommends antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with prosthetic joint implants,68 whereas the AAOS considers all patients with TJA to be at risk.69

Although recommendations exist, the actual risk of infection resulting from dental procedures and the role of antibiotic prophylaxis are not well defined. Berbari and colleagues71 found that antibiotic prophylaxis in high- or low-risk dental procedures did not decrease the risk of subsequent THA infection (OR, 0.9; 95% CI, 0.5-1.6) or TKA infection (OR, 1.2; 95% CI, 0.7-2.2). Moreover, the risk of infection was no higher for patients who had a prosthetic hip or knee and underwent a high- or low-risk dental procedure without antibiotic prophylaxis (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.4-1.6) than for similar patients who did not undergo a dental procedure (OR, 0.6; 95% CI, 0.4-1.1). Some studies highlight the low level of evidence supporting antibiotic prophylaxis during dental procedures.72,73 However, there is no evidence of adverse effects of antibiotic prophylaxis. Given the potential high risk of infection after such procedures, a more robust body of evidence is needed to reach consensus.

Evacuation Drain Management. Prolonged use of surgical evacuation drains may be a risk factor for SSI. Therefore, early drain removal is paramount. Higher infection rates with prolonged drain use have been found in patients with persistent wound drainage, including malnourished, obese, and over-anticoagulated patients. Patients with wounds persistently draining for >1 week should undergo superficial wound irrigation and débridement. Jaberi and colleagues74 assessed 10,325 TJA patients and found that the majority of persistent drainage ceased within 1 week with use of less invasive measures, including oral antibiotics and local wound care. Furthermore, only 28% of patients with persistent drainage underwent surgical débridement. It is unclear if this practice alone is appropriate. Infection should always be suspected and treated aggressively, and cultures should be obtained from synovial fluid before antibiotics are started, unless there is an obvious superficial infection that does not require further work-up.67

Economic Impact

SSIs remain a significant healthcare issue, and the social and financial costs are staggering. Without appropriate measures in place, these complications will place a larger burden on the healthcare system primarily as a result of longer hospital stays, multiple procedures, and increased resource utilization.75 Given the risk of progression to prosthetic joint infection, early preventive interventions must be explored.

Improved patient selection may be an important factor in reducing SSIs. In an analysis of 8494 joint arthroplasties, Malinzak and colleagues80 noted that patients with a BMI of >50 kg/m2 had an increased OR of infection of 21.3 compared to those with BMI <50 kg/m2. Wagner and colleagues81 analyzed 21,361 THAs and found that, for every BMI unit over 25 kg/m2, there was an 8% increased risk of joint infection (P < .001). Although it is unknown if there is an association between reduction in preoperative BMI and reduction in postoperative complication risk, it may still be worthwhile and cost-effective to modify this and similar risk factors before elective procedures.

Market forces are becoming a larger consideration in healthcare and are being driven by provider competition.82 Treatment outcomes, quality of care, and healthcare prices have gained attention as a means of estimating potential costs.83 In 2011, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) advanced the Bundled Payments for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative, which aimed to provide better coordinated care of higher quality and lower cost.84 This led to development of the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement (CJR) program, which gives beneficiaries flexibility in choosing services and ensures that providers adhere to required standards. During its 5-year test period beginning in 2016, the CJR program is projected to save CMS $153 million.84 Under this program, the institution where TJA is performed is responsible for all the costs of related care from time of surgery through 90 days after hospital discharge—which is known as an “episode of care.” If the cost incurred during an episode exceeds an established target cost (as determined by CMS), the hospital must repay Medicare the difference. Conversely, if the cost of an episode is less than the established target cost, the hospital is rewarded with the difference. Bundling payments for a single episode of care in this manner is thought to incentivize providers and hospitals to give patients more comprehensive and coordinated care. Given the substantial economic burden associated with joint arthroplasty infections, it is imperative for orthopedists to establish practical and cost-effective strategies that can prevent these disastrous complications.

Conclusion

SSIs are a devastating burden to patients, surgeons, and other healthcare providers. In recent years, new discoveries and innovations have helped mitigate the incidence of these complications of THA and TKA. However, the incidence of SSIs may rise with the increasing use of TJAs and with the development of new drug-resistant pathogens. In addition, the increasing number of TJAs performed on overweight and high-risk patients means the costs of postoperative infections will be substantial. With new reimbursement models in place, hospitals and providers are being held more accountable for the care they deliver during and after TJA. Consequently, more emphasis should be placed on techniques that are proved to minimize the incidence of SSIs.

Take-Home Points

- SSIs after TJA pose a substantial burden on patients, surgeons, and the healthcare system.

- While different forms of preoperative skin preparation have shown varying outcomes after TJA, the importance of preoperative patient optimization (nutritional status, immune function, etc) cannot be overstated.

- Intraoperative infection prevention measures include cutaneous preparation, gloving, body exhaust suits, surgical drapes, OR staff traffic and ventilation flow, and antibiotic-loaded cement.

- Antibiotic prophylaxis for dental procedures in TJA patients continues to remain a controversial issue with conflicting recommendations.

- SSIs have considerable financial costs and require increased resource utilization. Given the significant economic burden associated with TJA infections, it is imperative for orthopedists to establish practical and cost-effective strategies to prevent these devastating complications.

Surgical-site infection (SSI), a potentially devastating complication of lower extremity total joint arthroplasty (TJA), is estimated to occur in 1% to 2.5% of cases annually.1 Infection after TJA places a significant burden on patients, surgeons, and the healthcare system. Revision procedures that address infection after total hip arthroplasty (THA) are associated with more hospitalizations, more operations, longer hospital stay, and higher outpatient costs in comparison with primary THAs and revision surgeries for aseptic loosening.2 If left untreated, a SSI can go deeper into the joint and develop into a periprosthetic infection, which can be disastrous and costly. A periprosthetic joint infection study that used 2001 to 2009 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) data found that the cost of revision procedures increased to $560 million from $320 million, and was projected to reach $1.62 billion by 2020.3 Furthermore, society incurs indirect costs as a result of patient disability and loss of wages and productivity.2 Therefore, the issue of infection after TJA is even more crucial in our cost-conscious healthcare environment.

Patient optimization, advances in surgical technique, sterile protocol, and operative procedures have been effective in reducing bacterial counts at incision sites and minimizing SSIs. As a result, infection rates have leveled off after rising for a decade.4 Although infection prevention modalities have their differences, routine use is fundamental and recommended by the Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee.5 Furthermore, both the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee6,7 recently updated their SSI prevention guidelines by incorporating evidence-based methodology, an element missing from earlier recommendations.

The etiologies of postoperative SSIs have been discussed ad nauseam, but there are few reports summarizing the literature on infection prevention modalities. In this review, we identify and examine SSI prevention strategies as they relate to lower extremity TJA. Specifically, we discuss the literature on the preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative actions that can be taken to reduce the incidence of SSIs after TJA. We also highlight the economic implications of SSIs that occur after TJA.

Methods

For this review, we performed a literature search with PubMed, EBSCOhost, and Scopus. We looked for reports published between the inception of each database and July 2016. Combinations of various search terms were used: surgical site, infection, total joint arthroplasty, knee, hip, preoperative, intraoperative, perioperative, postoperative, preparation, nutrition, ventilation, antibiotic, body exhaust suit, gloves, drain, costs, economic, and payment.

Our search identified 195 abstracts. Drs. Mistry and Chughtai reviewed these to determine which articles were relevant. For any uncertainties, consensus was reached with the help of Dr. Delanois. Of the 195 articles, 103 were potentially relevant, and 54 of the 103 were excluded for being not relevant to preventing SSIs after TJA or for being written in a language other than English. The references in the remaining articles were assessed, and those with potentially relevant titles were selected for abstract review. This step provided another 35 articles. After all exclusions, 48 articles remained. We discuss these in the context of preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative measures and economic impact.

Results

Preoperative Measures