User login

Aquatic Antagonists: Dermatologic Injuries From Sea Urchins (Echinoidea)

Sea urchins—members of the phylum Echinodermata and the class Echinoidea—are spiny marine invertebrates. Their consumption of fleshy algae makes them essential players in maintaining reef ecosystems.1,2 Echinoids, a class that includes heart urchins and sand dollars, are ubiquitous in benthic marine environments, both free floating and rock boring, and inhabit a wide range of latitudes spanning from polar oceans to warm seas.3 Despite their immobility and nonaggression, sea urchin puncture wounds are common among divers, snorkelers, swimmers, surfers, and fishers who accidentally come into contact with their sharp spines. Although the epidemiology of sea urchin exposure and injury is difficult to assess, the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ most recent annual report in 2022 documents approximately 1426 annual aquatic bites and/or envenomations.4

Sea Urchin Morphology and Toxicity

Echinoderms (a term of Greek origin meaning spiny skin) share a radially symmetric calcium carbonate skeleton (termed stereom) that is supported by collagenous ligaments.1 Sea urchins possess spines composed of calcite crystals, which radiate from their body and play a role in locomotion and defense against predators—namely sea otters, starfish/sea stars, wolf eels, and triggerfish, among others (Figure).5 These brittle spines can easily penetrate human skin and subsequently break off the sea urchin body. Most species of sea urchins possess solid spines, but a small percentage (80 of approximately 700 extant species) have hollow spines containing various toxic substances.6 Penetration and systemic absorption of the toxins within these spines can generate severe systemic responses.

The venomous flower urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus), found in the Indian and Pacific oceans, is one of the more common species known to produce a systemic reaction involving neuromuscular blockage.7-9 The most common species harvested off the Pacific coast of the United States—Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (purple sea urchin) and Strongylocentrotus franciscanus (red sea urchins)—are not inherently venomous.8

Both the sea urchin body and spines are covered in a unique epithelium thought to be responsible for the majority of their proinflammatory and pronociceptive properties. Epithelial compounds identified include serotonin, histamines, steroids, glycosides, hemolysins, proteases, and bradykininlike and cholinergic substances.5,7 Additionally, certain sea urchin species possess 3-pronged pincerlike organs at the base of spines called pedicellariae, which are used in feeding.10 Skin penetration by the pedicellariae is especially dangerous, as they tightly adhere to wounds and contain venom-producing organs that allow them to continue injecting toxins after their detachment from the sea urchin body.11

Presentation and Diagnosis of Sea Urchin Injuries

Sea urchin injuries have a wide range of manifestations depending on the number of spines involved, the presence of venom, the depth and location of spine penetration, the duration of spine retention in the skin, and the time before treatment initiation. The most common site of sea urchin injury unsurprisingly is the lower extremities and feet, often in the context of divers and swimmers walking across the sea floor. The hands are another frequently injured site, along with the legs, arms, back, scalp, and even oral mucosa.11

Although clinical history and presentation frequently reveal the mechanism of aquatic injury, patients often are unsure of the agent to which they were exposed and may be unaware of retained foreign bodies. Dermoscopy can distinguish the distinct lines radiating from the core of sea urchin spines from other foreign bodies lodged within the skin.6 It also can be used to locate spines for removal or for their analysis following punch biopsy.6,12 The radiopaque nature of sea urchin spines makes radiography and magnetic resonance imaging useful tools in assessment of periarticular soft-tissue damage and spine removal.8,11,13 Ultrasonography can reveal spines that no longer appear on radiography due to absorption by human tissue.14

Immediate Dermatologic Effects

Sea urchin injuries can be broadly categorized into immediate and delayed reactions. Immediate manifestations of contact with sea urchin spines include localized pain, bleeding, erythema, myalgia, and edema at the site of injury that can last from a few hours to 1 week without proper wound care and spine removal.5 Systemic symptoms ranging from dizziness, lightheadedness, paresthesia, aphonia, paralysis, coma, and death generally are only seen following injuries from venomous species, attachment of pedicellariae, injuries involving neurovascular structures, or penetration by more than 15 spines.7,11

Initial treatment includes soaking the wound in hot water (113 °F [45 °C]) for 30 to 90 minutes and subsequently removing spines and pedicellariae to prevent development of delayed reactions.5,15,16 The compounds in the sea urchin epithelium are heat labile and will be inactivated upon soaking in hot water.16 Extraction of spines can be difficult, as they are brittle and easily break in the skin. Successful removal has been reported using forceps and a hypodermic needle as well as excision; both approaches may require local anesthesia.8,17 Another technique involves freezing the localized area with liquid nitrogen to allow easier removal upon skin blistering.18 Punch biopsy also has been utilized as an effective means of ensuring all spiny fragments are removed.9,19,20 These spines often cause black or purple tattoolike staining at the puncture site, which can persist for a few days after spine extraction.8 Ablation using the erbium-doped:YAG laser may be helpful for removal of associated pigment.21,22

Delayed Dermatologic Effects

Delayed reactions to sea urchin injuries often are attributable to prolonged retention of spines in the skin. Granulomatous reactions typically manifest 2 weeks after injury as firm nonsuppurative nodules with central umbilication and a hyperkeratotic surface.7 These nodules may or may not be painful. Histopathology most often reveals foreign body and sarcoidal-type granulomatous reactions. However, tuberculoid, necrobiotic, and suppurative granulomas also may develop.13 Other microscopic features include inflammatory reactions, suppurative dermatitis, focal necrosis, and microabscesses.23 Wounds with progression to granulomatous disease often require surgical debridement.

Other more serious sequalae can result from involvement of joint capsules, especially in the hands and feet. Sea urchin injury involving joint spaces should be treated aggressively, as progression to inflammatory or infectious synovitis and tenosynovitis can cause irreversible loss of joint function. Inflammatory synovitis occurs 1 to 2 months on average after injury following a period of minimal symptoms and begins as a gradual increase in joint swelling and decrease in range of motion.8 Infectious tenosynovitis manifests quite similarly. Although suppurative etiologies generally progress with a more acute onset, certain infectious organisms (eg, Mycobacterium) take on an indolent course and should not be overlooked as a cause of delayed symptoms.8 The Kavanel cardinal signs are a sensitive tool used in the diagnosis of infectious flexor sheath tenosynovitis.8,24 If suspicion for joint infection is high, emergency referral should be made for debridement and culture-guided antibiotic therapy. Left untreated, infectious tenosynovitis can result in tendon necrosis or rupture, digit necrosis, and systemic infection.24 Patients with joint involvement should be referred to specialty care (eg, hand surgeon), as they often require synovectomy and surgical removal of foreign material.8

From 1 month to 1 year after injury, prolonged granulomatous synovitis of the hand may eventually lead to joint destruction known as “sea urchin arthritis.” These patients present with decreased range of motion and numerous nodules on the hand with a hyperkeratotic surface. Radiography reveals joint space narrowing, osteolysis, subchondral sclerosis, and periosteal reaction. Synovectomy and debridement are necessary to prevent irreversible joint damage or the need for arthrodesis and bone grafting.24

Other Treatment Considerations

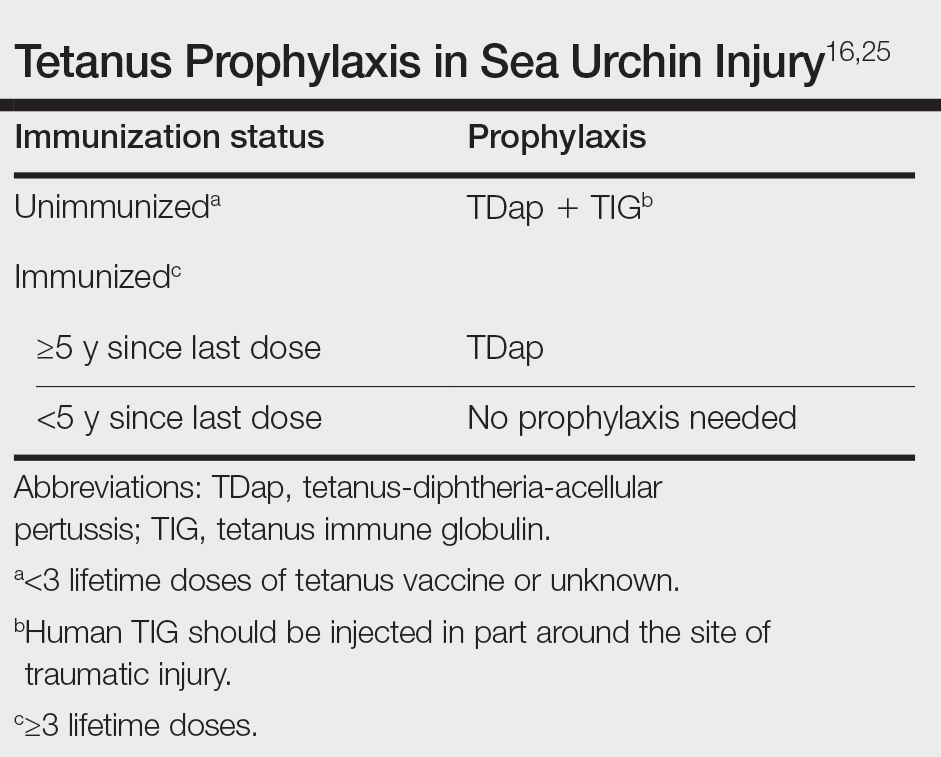

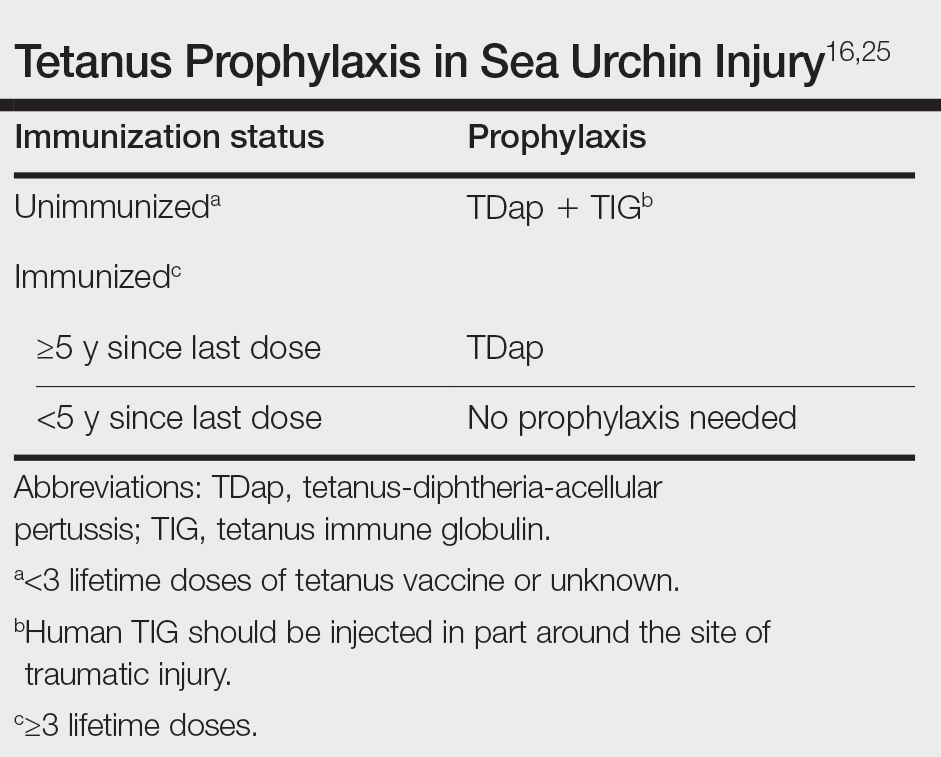

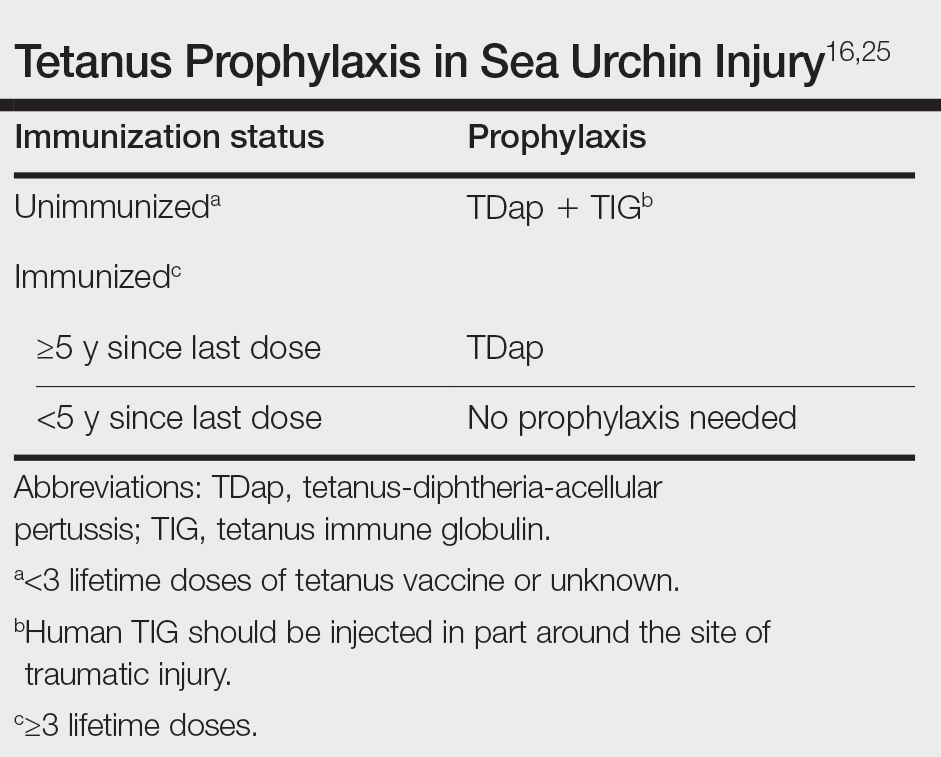

Other important considerations in the care of sea urchin spine injuries include assessment of tetanus immunization status and administration of necessary prophylaxis as soon as possible, even in delayed presentations (Table).16,25 Cultures should be taken only if infection is suspected. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended unless the patient is immunocompromised or otherwise has impaired wound healing. If a patient presents with systemic symptoms, they should be referred to an emergency care facility for further management.

Final Thoughts

Sea urchin injuries can lead to serious complications if not diagnosed quickly and treated properly. Retention of sea urchin spines in the deep tissues and joint spaces may lead to granulomas, inflammatory and infectious tenosynovitis (including mycobacterial infection), and sea urchin arthritis requiring surgical debridement and possible irreversible joint damage, up to a year after initial injury. Patients should be educated on the possibility of developing these delayed reactions and instructed to seek immediate care. Joint deformities, range-of-motion deficits, and involvement of neurovascular structures should be considered emergent and referred for proper management. Shoes and diving gear offer some protection but are easily penetrable by sharp sea urchin spines. Preventive focus should be aimed at educating patients and providers on the importance of prompt spine removal upon injury. Although dermatologic and systemic manifestations vary widely, a thorough history, physical examination, and appropriate use of imaging modalities can facilitate accurate diagnosis and guide treatment.

- Amemiya CT, Miyake T, Rast JP. Echinoderms. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R944-R946. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.026

- Koch NM, Coppard SE, Lessios HA, et al. A phylogenomic resolution of the sea urchin tree of life. BMC Evol Biol. 2018;18:189. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1300-4

- Amir Y, Insler M, Giller A, et al. Senescence and longevity of sea urchins. Genes (Basel). 2020;11:573. doi:10.3390/genes11050573

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, et al. 2022 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System® (NPDS) from America's Poison Centers®: 40th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2023;61:717-939. doi:10.1080/15563650.2023.2268981

- Gelman Y, Kong EL, Murphy-Lavoie HM. Sea urchin toxicity. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Suarez-Conde MF, Vallone MG, González VM, et al. Sea urchin skin lesions: a case report. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021009. doi:10.5826/dpc.1102a09

- Al-Kathiri L, Al-Najjar T, Sulaiman I. Sea urchin granuloma of the hands: a case report. Oman Med J. 2019;34:350-353. doi:10.5001/omj.2019.68

- Dahl WJ, Jebson P, Louis DS. Sea urchin injuries to the hand: a case report and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:153-156.

- Hatakeyama T, Ichise A, Unno H, et al. Carbohydrate recognition by the rhamnose-binding lectin SUL-I with a novel three-domain structure isolated from the venom of globiferous pedicellariae of the flower sea urchin Toxopneustes pileolus. Protein Sci. 2017;26:1574-1583. doi:10.1002/pro.3185

- Balhara KS, Stolbach A. Marine envenomations. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32:223-243. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2013.09.009

- Schwartz Z, Cohen M, Lipner SR. Sea urchin injuries: a review and clinical approach algorithm. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:150-156. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1638884

- Park SJ, Park JW, Choi SY, et al. Use of dermoscopy after punch removal of a veiled sea urchin spine. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14947. doi:10.1111/dth.14947

- Wada T, Soma T, Gaman K, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:398-401. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.11.016

- Groleau S, Chhem RK, Younge D, et al. Ultrasonography of foreign-body tenosynovitis. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1992;43:454-456.

- Hornbeak KB, Auerbach PS. Marine envenomation. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:321-337. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2016.12.004

- Noonburg GE. Management of extremity trauma and related infections occurring in the aquatic environment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:243-253. doi:10.5435/00124635-200507000-00004

- Haddad Junior V. Observation of initial clinical manifestations and repercussions from the treatment of 314 human injuries caused by black sea urchins (Echinometra lucunter) on the southeastern Brazilian coast. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45:390-392. doi:10.1590/s0037-86822012000300021

- Gargus MD, Morohashi DK. A sea-urchin spine chilling remedy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1867-1868. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1209382

- Sjøberg T, de Weerd L. The usefulness of a skin biopsy punch to remove sea urchin spines. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:383. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05296.x

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, Cuellar-Barboza A, Ancer-Arellano J, et al. Classic dermatological tools: foreign body removal with punch biopsy.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E93-E94. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.038

- Gungor S, Tarikçi N, Gokdemir G. Removal of sea urchin spines using erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet ablation. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:508-510. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02259.x

- Böer A, Ochsendorf FR, Beier C, et al. Effective removal of sea-urchin spines by erbium:YAG laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:169-170. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04306.x

- De La Torre C, Toribio J. Sea-urchin granuloma: histologic profile. a pathologic study of 50 biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:223-228. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028005223.x

- Yi A, Kennedy C, Chia B, et al. Radiographic soft tissue thickness differentiating pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis from other finger infections. J Hand Surg Am. 2019;44:394-399. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2019.01.013

- Callison C, Nguyen H. Tetanus prophylaxis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Sea urchins—members of the phylum Echinodermata and the class Echinoidea—are spiny marine invertebrates. Their consumption of fleshy algae makes them essential players in maintaining reef ecosystems.1,2 Echinoids, a class that includes heart urchins and sand dollars, are ubiquitous in benthic marine environments, both free floating and rock boring, and inhabit a wide range of latitudes spanning from polar oceans to warm seas.3 Despite their immobility and nonaggression, sea urchin puncture wounds are common among divers, snorkelers, swimmers, surfers, and fishers who accidentally come into contact with their sharp spines. Although the epidemiology of sea urchin exposure and injury is difficult to assess, the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ most recent annual report in 2022 documents approximately 1426 annual aquatic bites and/or envenomations.4

Sea Urchin Morphology and Toxicity

Echinoderms (a term of Greek origin meaning spiny skin) share a radially symmetric calcium carbonate skeleton (termed stereom) that is supported by collagenous ligaments.1 Sea urchins possess spines composed of calcite crystals, which radiate from their body and play a role in locomotion and defense against predators—namely sea otters, starfish/sea stars, wolf eels, and triggerfish, among others (Figure).5 These brittle spines can easily penetrate human skin and subsequently break off the sea urchin body. Most species of sea urchins possess solid spines, but a small percentage (80 of approximately 700 extant species) have hollow spines containing various toxic substances.6 Penetration and systemic absorption of the toxins within these spines can generate severe systemic responses.

The venomous flower urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus), found in the Indian and Pacific oceans, is one of the more common species known to produce a systemic reaction involving neuromuscular blockage.7-9 The most common species harvested off the Pacific coast of the United States—Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (purple sea urchin) and Strongylocentrotus franciscanus (red sea urchins)—are not inherently venomous.8

Both the sea urchin body and spines are covered in a unique epithelium thought to be responsible for the majority of their proinflammatory and pronociceptive properties. Epithelial compounds identified include serotonin, histamines, steroids, glycosides, hemolysins, proteases, and bradykininlike and cholinergic substances.5,7 Additionally, certain sea urchin species possess 3-pronged pincerlike organs at the base of spines called pedicellariae, which are used in feeding.10 Skin penetration by the pedicellariae is especially dangerous, as they tightly adhere to wounds and contain venom-producing organs that allow them to continue injecting toxins after their detachment from the sea urchin body.11

Presentation and Diagnosis of Sea Urchin Injuries

Sea urchin injuries have a wide range of manifestations depending on the number of spines involved, the presence of venom, the depth and location of spine penetration, the duration of spine retention in the skin, and the time before treatment initiation. The most common site of sea urchin injury unsurprisingly is the lower extremities and feet, often in the context of divers and swimmers walking across the sea floor. The hands are another frequently injured site, along with the legs, arms, back, scalp, and even oral mucosa.11

Although clinical history and presentation frequently reveal the mechanism of aquatic injury, patients often are unsure of the agent to which they were exposed and may be unaware of retained foreign bodies. Dermoscopy can distinguish the distinct lines radiating from the core of sea urchin spines from other foreign bodies lodged within the skin.6 It also can be used to locate spines for removal or for their analysis following punch biopsy.6,12 The radiopaque nature of sea urchin spines makes radiography and magnetic resonance imaging useful tools in assessment of periarticular soft-tissue damage and spine removal.8,11,13 Ultrasonography can reveal spines that no longer appear on radiography due to absorption by human tissue.14

Immediate Dermatologic Effects

Sea urchin injuries can be broadly categorized into immediate and delayed reactions. Immediate manifestations of contact with sea urchin spines include localized pain, bleeding, erythema, myalgia, and edema at the site of injury that can last from a few hours to 1 week without proper wound care and spine removal.5 Systemic symptoms ranging from dizziness, lightheadedness, paresthesia, aphonia, paralysis, coma, and death generally are only seen following injuries from venomous species, attachment of pedicellariae, injuries involving neurovascular structures, or penetration by more than 15 spines.7,11

Initial treatment includes soaking the wound in hot water (113 °F [45 °C]) for 30 to 90 minutes and subsequently removing spines and pedicellariae to prevent development of delayed reactions.5,15,16 The compounds in the sea urchin epithelium are heat labile and will be inactivated upon soaking in hot water.16 Extraction of spines can be difficult, as they are brittle and easily break in the skin. Successful removal has been reported using forceps and a hypodermic needle as well as excision; both approaches may require local anesthesia.8,17 Another technique involves freezing the localized area with liquid nitrogen to allow easier removal upon skin blistering.18 Punch biopsy also has been utilized as an effective means of ensuring all spiny fragments are removed.9,19,20 These spines often cause black or purple tattoolike staining at the puncture site, which can persist for a few days after spine extraction.8 Ablation using the erbium-doped:YAG laser may be helpful for removal of associated pigment.21,22

Delayed Dermatologic Effects

Delayed reactions to sea urchin injuries often are attributable to prolonged retention of spines in the skin. Granulomatous reactions typically manifest 2 weeks after injury as firm nonsuppurative nodules with central umbilication and a hyperkeratotic surface.7 These nodules may or may not be painful. Histopathology most often reveals foreign body and sarcoidal-type granulomatous reactions. However, tuberculoid, necrobiotic, and suppurative granulomas also may develop.13 Other microscopic features include inflammatory reactions, suppurative dermatitis, focal necrosis, and microabscesses.23 Wounds with progression to granulomatous disease often require surgical debridement.

Other more serious sequalae can result from involvement of joint capsules, especially in the hands and feet. Sea urchin injury involving joint spaces should be treated aggressively, as progression to inflammatory or infectious synovitis and tenosynovitis can cause irreversible loss of joint function. Inflammatory synovitis occurs 1 to 2 months on average after injury following a period of minimal symptoms and begins as a gradual increase in joint swelling and decrease in range of motion.8 Infectious tenosynovitis manifests quite similarly. Although suppurative etiologies generally progress with a more acute onset, certain infectious organisms (eg, Mycobacterium) take on an indolent course and should not be overlooked as a cause of delayed symptoms.8 The Kavanel cardinal signs are a sensitive tool used in the diagnosis of infectious flexor sheath tenosynovitis.8,24 If suspicion for joint infection is high, emergency referral should be made for debridement and culture-guided antibiotic therapy. Left untreated, infectious tenosynovitis can result in tendon necrosis or rupture, digit necrosis, and systemic infection.24 Patients with joint involvement should be referred to specialty care (eg, hand surgeon), as they often require synovectomy and surgical removal of foreign material.8

From 1 month to 1 year after injury, prolonged granulomatous synovitis of the hand may eventually lead to joint destruction known as “sea urchin arthritis.” These patients present with decreased range of motion and numerous nodules on the hand with a hyperkeratotic surface. Radiography reveals joint space narrowing, osteolysis, subchondral sclerosis, and periosteal reaction. Synovectomy and debridement are necessary to prevent irreversible joint damage or the need for arthrodesis and bone grafting.24

Other Treatment Considerations

Other important considerations in the care of sea urchin spine injuries include assessment of tetanus immunization status and administration of necessary prophylaxis as soon as possible, even in delayed presentations (Table).16,25 Cultures should be taken only if infection is suspected. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended unless the patient is immunocompromised or otherwise has impaired wound healing. If a patient presents with systemic symptoms, they should be referred to an emergency care facility for further management.

Final Thoughts

Sea urchin injuries can lead to serious complications if not diagnosed quickly and treated properly. Retention of sea urchin spines in the deep tissues and joint spaces may lead to granulomas, inflammatory and infectious tenosynovitis (including mycobacterial infection), and sea urchin arthritis requiring surgical debridement and possible irreversible joint damage, up to a year after initial injury. Patients should be educated on the possibility of developing these delayed reactions and instructed to seek immediate care. Joint deformities, range-of-motion deficits, and involvement of neurovascular structures should be considered emergent and referred for proper management. Shoes and diving gear offer some protection but are easily penetrable by sharp sea urchin spines. Preventive focus should be aimed at educating patients and providers on the importance of prompt spine removal upon injury. Although dermatologic and systemic manifestations vary widely, a thorough history, physical examination, and appropriate use of imaging modalities can facilitate accurate diagnosis and guide treatment.

Sea urchins—members of the phylum Echinodermata and the class Echinoidea—are spiny marine invertebrates. Their consumption of fleshy algae makes them essential players in maintaining reef ecosystems.1,2 Echinoids, a class that includes heart urchins and sand dollars, are ubiquitous in benthic marine environments, both free floating and rock boring, and inhabit a wide range of latitudes spanning from polar oceans to warm seas.3 Despite their immobility and nonaggression, sea urchin puncture wounds are common among divers, snorkelers, swimmers, surfers, and fishers who accidentally come into contact with their sharp spines. Although the epidemiology of sea urchin exposure and injury is difficult to assess, the American Association of Poison Control Centers’ most recent annual report in 2022 documents approximately 1426 annual aquatic bites and/or envenomations.4

Sea Urchin Morphology and Toxicity

Echinoderms (a term of Greek origin meaning spiny skin) share a radially symmetric calcium carbonate skeleton (termed stereom) that is supported by collagenous ligaments.1 Sea urchins possess spines composed of calcite crystals, which radiate from their body and play a role in locomotion and defense against predators—namely sea otters, starfish/sea stars, wolf eels, and triggerfish, among others (Figure).5 These brittle spines can easily penetrate human skin and subsequently break off the sea urchin body. Most species of sea urchins possess solid spines, but a small percentage (80 of approximately 700 extant species) have hollow spines containing various toxic substances.6 Penetration and systemic absorption of the toxins within these spines can generate severe systemic responses.

The venomous flower urchin (Toxopneustes pileolus), found in the Indian and Pacific oceans, is one of the more common species known to produce a systemic reaction involving neuromuscular blockage.7-9 The most common species harvested off the Pacific coast of the United States—Strongylocentrotus purpuratus (purple sea urchin) and Strongylocentrotus franciscanus (red sea urchins)—are not inherently venomous.8

Both the sea urchin body and spines are covered in a unique epithelium thought to be responsible for the majority of their proinflammatory and pronociceptive properties. Epithelial compounds identified include serotonin, histamines, steroids, glycosides, hemolysins, proteases, and bradykininlike and cholinergic substances.5,7 Additionally, certain sea urchin species possess 3-pronged pincerlike organs at the base of spines called pedicellariae, which are used in feeding.10 Skin penetration by the pedicellariae is especially dangerous, as they tightly adhere to wounds and contain venom-producing organs that allow them to continue injecting toxins after their detachment from the sea urchin body.11

Presentation and Diagnosis of Sea Urchin Injuries

Sea urchin injuries have a wide range of manifestations depending on the number of spines involved, the presence of venom, the depth and location of spine penetration, the duration of spine retention in the skin, and the time before treatment initiation. The most common site of sea urchin injury unsurprisingly is the lower extremities and feet, often in the context of divers and swimmers walking across the sea floor. The hands are another frequently injured site, along with the legs, arms, back, scalp, and even oral mucosa.11

Although clinical history and presentation frequently reveal the mechanism of aquatic injury, patients often are unsure of the agent to which they were exposed and may be unaware of retained foreign bodies. Dermoscopy can distinguish the distinct lines radiating from the core of sea urchin spines from other foreign bodies lodged within the skin.6 It also can be used to locate spines for removal or for their analysis following punch biopsy.6,12 The radiopaque nature of sea urchin spines makes radiography and magnetic resonance imaging useful tools in assessment of periarticular soft-tissue damage and spine removal.8,11,13 Ultrasonography can reveal spines that no longer appear on radiography due to absorption by human tissue.14

Immediate Dermatologic Effects

Sea urchin injuries can be broadly categorized into immediate and delayed reactions. Immediate manifestations of contact with sea urchin spines include localized pain, bleeding, erythema, myalgia, and edema at the site of injury that can last from a few hours to 1 week without proper wound care and spine removal.5 Systemic symptoms ranging from dizziness, lightheadedness, paresthesia, aphonia, paralysis, coma, and death generally are only seen following injuries from venomous species, attachment of pedicellariae, injuries involving neurovascular structures, or penetration by more than 15 spines.7,11

Initial treatment includes soaking the wound in hot water (113 °F [45 °C]) for 30 to 90 minutes and subsequently removing spines and pedicellariae to prevent development of delayed reactions.5,15,16 The compounds in the sea urchin epithelium are heat labile and will be inactivated upon soaking in hot water.16 Extraction of spines can be difficult, as they are brittle and easily break in the skin. Successful removal has been reported using forceps and a hypodermic needle as well as excision; both approaches may require local anesthesia.8,17 Another technique involves freezing the localized area with liquid nitrogen to allow easier removal upon skin blistering.18 Punch biopsy also has been utilized as an effective means of ensuring all spiny fragments are removed.9,19,20 These spines often cause black or purple tattoolike staining at the puncture site, which can persist for a few days after spine extraction.8 Ablation using the erbium-doped:YAG laser may be helpful for removal of associated pigment.21,22

Delayed Dermatologic Effects

Delayed reactions to sea urchin injuries often are attributable to prolonged retention of spines in the skin. Granulomatous reactions typically manifest 2 weeks after injury as firm nonsuppurative nodules with central umbilication and a hyperkeratotic surface.7 These nodules may or may not be painful. Histopathology most often reveals foreign body and sarcoidal-type granulomatous reactions. However, tuberculoid, necrobiotic, and suppurative granulomas also may develop.13 Other microscopic features include inflammatory reactions, suppurative dermatitis, focal necrosis, and microabscesses.23 Wounds with progression to granulomatous disease often require surgical debridement.

Other more serious sequalae can result from involvement of joint capsules, especially in the hands and feet. Sea urchin injury involving joint spaces should be treated aggressively, as progression to inflammatory or infectious synovitis and tenosynovitis can cause irreversible loss of joint function. Inflammatory synovitis occurs 1 to 2 months on average after injury following a period of minimal symptoms and begins as a gradual increase in joint swelling and decrease in range of motion.8 Infectious tenosynovitis manifests quite similarly. Although suppurative etiologies generally progress with a more acute onset, certain infectious organisms (eg, Mycobacterium) take on an indolent course and should not be overlooked as a cause of delayed symptoms.8 The Kavanel cardinal signs are a sensitive tool used in the diagnosis of infectious flexor sheath tenosynovitis.8,24 If suspicion for joint infection is high, emergency referral should be made for debridement and culture-guided antibiotic therapy. Left untreated, infectious tenosynovitis can result in tendon necrosis or rupture, digit necrosis, and systemic infection.24 Patients with joint involvement should be referred to specialty care (eg, hand surgeon), as they often require synovectomy and surgical removal of foreign material.8

From 1 month to 1 year after injury, prolonged granulomatous synovitis of the hand may eventually lead to joint destruction known as “sea urchin arthritis.” These patients present with decreased range of motion and numerous nodules on the hand with a hyperkeratotic surface. Radiography reveals joint space narrowing, osteolysis, subchondral sclerosis, and periosteal reaction. Synovectomy and debridement are necessary to prevent irreversible joint damage or the need for arthrodesis and bone grafting.24

Other Treatment Considerations

Other important considerations in the care of sea urchin spine injuries include assessment of tetanus immunization status and administration of necessary prophylaxis as soon as possible, even in delayed presentations (Table).16,25 Cultures should be taken only if infection is suspected. Prophylactic antibiotics are not recommended unless the patient is immunocompromised or otherwise has impaired wound healing. If a patient presents with systemic symptoms, they should be referred to an emergency care facility for further management.

Final Thoughts

Sea urchin injuries can lead to serious complications if not diagnosed quickly and treated properly. Retention of sea urchin spines in the deep tissues and joint spaces may lead to granulomas, inflammatory and infectious tenosynovitis (including mycobacterial infection), and sea urchin arthritis requiring surgical debridement and possible irreversible joint damage, up to a year after initial injury. Patients should be educated on the possibility of developing these delayed reactions and instructed to seek immediate care. Joint deformities, range-of-motion deficits, and involvement of neurovascular structures should be considered emergent and referred for proper management. Shoes and diving gear offer some protection but are easily penetrable by sharp sea urchin spines. Preventive focus should be aimed at educating patients and providers on the importance of prompt spine removal upon injury. Although dermatologic and systemic manifestations vary widely, a thorough history, physical examination, and appropriate use of imaging modalities can facilitate accurate diagnosis and guide treatment.

- Amemiya CT, Miyake T, Rast JP. Echinoderms. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R944-R946. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.026

- Koch NM, Coppard SE, Lessios HA, et al. A phylogenomic resolution of the sea urchin tree of life. BMC Evol Biol. 2018;18:189. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1300-4

- Amir Y, Insler M, Giller A, et al. Senescence and longevity of sea urchins. Genes (Basel). 2020;11:573. doi:10.3390/genes11050573

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, et al. 2022 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System® (NPDS) from America's Poison Centers®: 40th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2023;61:717-939. doi:10.1080/15563650.2023.2268981

- Gelman Y, Kong EL, Murphy-Lavoie HM. Sea urchin toxicity. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Suarez-Conde MF, Vallone MG, González VM, et al. Sea urchin skin lesions: a case report. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021009. doi:10.5826/dpc.1102a09

- Al-Kathiri L, Al-Najjar T, Sulaiman I. Sea urchin granuloma of the hands: a case report. Oman Med J. 2019;34:350-353. doi:10.5001/omj.2019.68

- Dahl WJ, Jebson P, Louis DS. Sea urchin injuries to the hand: a case report and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:153-156.

- Hatakeyama T, Ichise A, Unno H, et al. Carbohydrate recognition by the rhamnose-binding lectin SUL-I with a novel three-domain structure isolated from the venom of globiferous pedicellariae of the flower sea urchin Toxopneustes pileolus. Protein Sci. 2017;26:1574-1583. doi:10.1002/pro.3185

- Balhara KS, Stolbach A. Marine envenomations. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32:223-243. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2013.09.009

- Schwartz Z, Cohen M, Lipner SR. Sea urchin injuries: a review and clinical approach algorithm. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:150-156. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1638884

- Park SJ, Park JW, Choi SY, et al. Use of dermoscopy after punch removal of a veiled sea urchin spine. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14947. doi:10.1111/dth.14947

- Wada T, Soma T, Gaman K, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:398-401. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.11.016

- Groleau S, Chhem RK, Younge D, et al. Ultrasonography of foreign-body tenosynovitis. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1992;43:454-456.

- Hornbeak KB, Auerbach PS. Marine envenomation. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:321-337. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2016.12.004

- Noonburg GE. Management of extremity trauma and related infections occurring in the aquatic environment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:243-253. doi:10.5435/00124635-200507000-00004

- Haddad Junior V. Observation of initial clinical manifestations and repercussions from the treatment of 314 human injuries caused by black sea urchins (Echinometra lucunter) on the southeastern Brazilian coast. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45:390-392. doi:10.1590/s0037-86822012000300021

- Gargus MD, Morohashi DK. A sea-urchin spine chilling remedy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1867-1868. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1209382

- Sjøberg T, de Weerd L. The usefulness of a skin biopsy punch to remove sea urchin spines. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:383. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05296.x

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, Cuellar-Barboza A, Ancer-Arellano J, et al. Classic dermatological tools: foreign body removal with punch biopsy.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E93-E94. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.038

- Gungor S, Tarikçi N, Gokdemir G. Removal of sea urchin spines using erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet ablation. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:508-510. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02259.x

- Böer A, Ochsendorf FR, Beier C, et al. Effective removal of sea-urchin spines by erbium:YAG laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:169-170. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04306.x

- De La Torre C, Toribio J. Sea-urchin granuloma: histologic profile. a pathologic study of 50 biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:223-228. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028005223.x

- Yi A, Kennedy C, Chia B, et al. Radiographic soft tissue thickness differentiating pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis from other finger infections. J Hand Surg Am. 2019;44:394-399. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2019.01.013

- Callison C, Nguyen H. Tetanus prophylaxis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Amemiya CT, Miyake T, Rast JP. Echinoderms. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R944-R946. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.11.026

- Koch NM, Coppard SE, Lessios HA, et al. A phylogenomic resolution of the sea urchin tree of life. BMC Evol Biol. 2018;18:189. doi:10.1186/s12862-018-1300-4

- Amir Y, Insler M, Giller A, et al. Senescence and longevity of sea urchins. Genes (Basel). 2020;11:573. doi:10.3390/genes11050573

- Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Beuhler MC, et al. 2022 Annual Report of the National Poison Data System® (NPDS) from America's Poison Centers®: 40th annual report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2023;61:717-939. doi:10.1080/15563650.2023.2268981

- Gelman Y, Kong EL, Murphy-Lavoie HM. Sea urchin toxicity. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Suarez-Conde MF, Vallone MG, González VM, et al. Sea urchin skin lesions: a case report. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2021;11:E2021009. doi:10.5826/dpc.1102a09

- Al-Kathiri L, Al-Najjar T, Sulaiman I. Sea urchin granuloma of the hands: a case report. Oman Med J. 2019;34:350-353. doi:10.5001/omj.2019.68

- Dahl WJ, Jebson P, Louis DS. Sea urchin injuries to the hand: a case report and review of the literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2010;30:153-156.

- Hatakeyama T, Ichise A, Unno H, et al. Carbohydrate recognition by the rhamnose-binding lectin SUL-I with a novel three-domain structure isolated from the venom of globiferous pedicellariae of the flower sea urchin Toxopneustes pileolus. Protein Sci. 2017;26:1574-1583. doi:10.1002/pro.3185

- Balhara KS, Stolbach A. Marine envenomations. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32:223-243. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2013.09.009

- Schwartz Z, Cohen M, Lipner SR. Sea urchin injuries: a review and clinical approach algorithm. J Dermatolog Treat. 2021;32:150-156. doi:10.1080/09546634.2019.1638884

- Park SJ, Park JW, Choi SY, et al. Use of dermoscopy after punch removal of a veiled sea urchin spine. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14947. doi:10.1111/dth.14947

- Wada T, Soma T, Gaman K, et al. Sea urchin spine arthritis of the hand. J Hand Surg Am. 2008;33:398-401. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2007.11.016

- Groleau S, Chhem RK, Younge D, et al. Ultrasonography of foreign-body tenosynovitis. Can Assoc Radiol J. 1992;43:454-456.

- Hornbeak KB, Auerbach PS. Marine envenomation. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2017;35:321-337. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2016.12.004

- Noonburg GE. Management of extremity trauma and related infections occurring in the aquatic environment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13:243-253. doi:10.5435/00124635-200507000-00004

- Haddad Junior V. Observation of initial clinical manifestations and repercussions from the treatment of 314 human injuries caused by black sea urchins (Echinometra lucunter) on the southeastern Brazilian coast. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45:390-392. doi:10.1590/s0037-86822012000300021

- Gargus MD, Morohashi DK. A sea-urchin spine chilling remedy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1867-1868. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1209382

- Sjøberg T, de Weerd L. The usefulness of a skin biopsy punch to remove sea urchin spines. ANZ J Surg. 2010;80:383. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2010.05296.x

- Cardenas-de la Garza JA, Cuellar-Barboza A, Ancer-Arellano J, et al. Classic dermatological tools: foreign body removal with punch biopsy.J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:E93-E94. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.038

- Gungor S, Tarikçi N, Gokdemir G. Removal of sea urchin spines using erbium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet ablation. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:508-510. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2011.02259.x

- Böer A, Ochsendorf FR, Beier C, et al. Effective removal of sea-urchin spines by erbium:YAG laser ablation. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:169-170. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04306.x

- De La Torre C, Toribio J. Sea-urchin granuloma: histologic profile. a pathologic study of 50 biopsies. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:223-228. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0560.2001.028005223.x

- Yi A, Kennedy C, Chia B, et al. Radiographic soft tissue thickness differentiating pyogenic flexor tenosynovitis from other finger infections. J Hand Surg Am. 2019;44:394-399. doi:10.1016/j.jhsa.2019.01.013

- Callison C, Nguyen H. Tetanus prophylaxis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Practice Points

- Sea urchin spines easily become embedded in human skin upon contact and cause localized pain, edema, and black or purple pinpoint markings.

- Immediate treatment includes soaking in hot water (113 12°F [45 12°C]) for 30 to 90 minutes to inactivate proinflammatory compounds, followed by extraction of the spines.

- Successful methods of spine removal include the use of forceps and a hypodermic needle, as well as excision, liquid nitrogen, and punch biopsy.

- Prompt removal of the spines can reduce the incidence of delayed granulomatous reactions, synovitis, and sea urchin arthritis.