User login

Fat Necrosis of the Breast Mimicking Breast Cancer in a Male Patient Following Wax Hair Removal

To the Editor:

Fat necrosis of the breast is a benign inflammatory disease of adipose tissue commonly observed after trauma in the female breast during the perimenopausal period.1 Fat necrosis of the male breast is rare, first described by Silverstone2 in 1949; the condition usually presents with unilateral, painful or asymptomatic, firm nodules, which in rare cases are observed as skin retraction and thickening, ecchymosis, erythematous plaque–like cellulitis, local depression, and/or discoloration of the breast skin.3-5

Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the male breast may need to be confirmed via biopsy in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings because the condition can mimic breast cancer.1 We report a case of bilateral fat necrosis of the breast mimicking breast cancer following wax hair removal.

A 42-year-old man presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation of redness, swelling, and hardness of the skin of both breasts of 3 weeks’ duration. The patient had a history of wax hair removal of the entire anterior aspect of the body. He reported an erythematous, edematous, warm plaque that developed on the breasts 2 days after waxing. The plaque did not respond to antibiotics. The swelling and induration progressed over the 2 weeks after the patient was waxed. The patient had no family history of breast cancer. He had a standing diagnosis of gynecomastia. He denied any history of fat or filler injection in the affected area.

Dermatologic examination revealed erythematous, edematous, indurated, asymptomatic plaques with a peau d’orange appearance on the bilateral pectoral and presternal region. Minimal retraction of the right areola was noted (Figure 1). The bilateral axillary lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory results including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (108 mm/h [reference range, 2–20 mm/h]), C-reactive protein (9.2 mg/dL [reference range, >0.5 mg/dL]), and ferritin levels (645

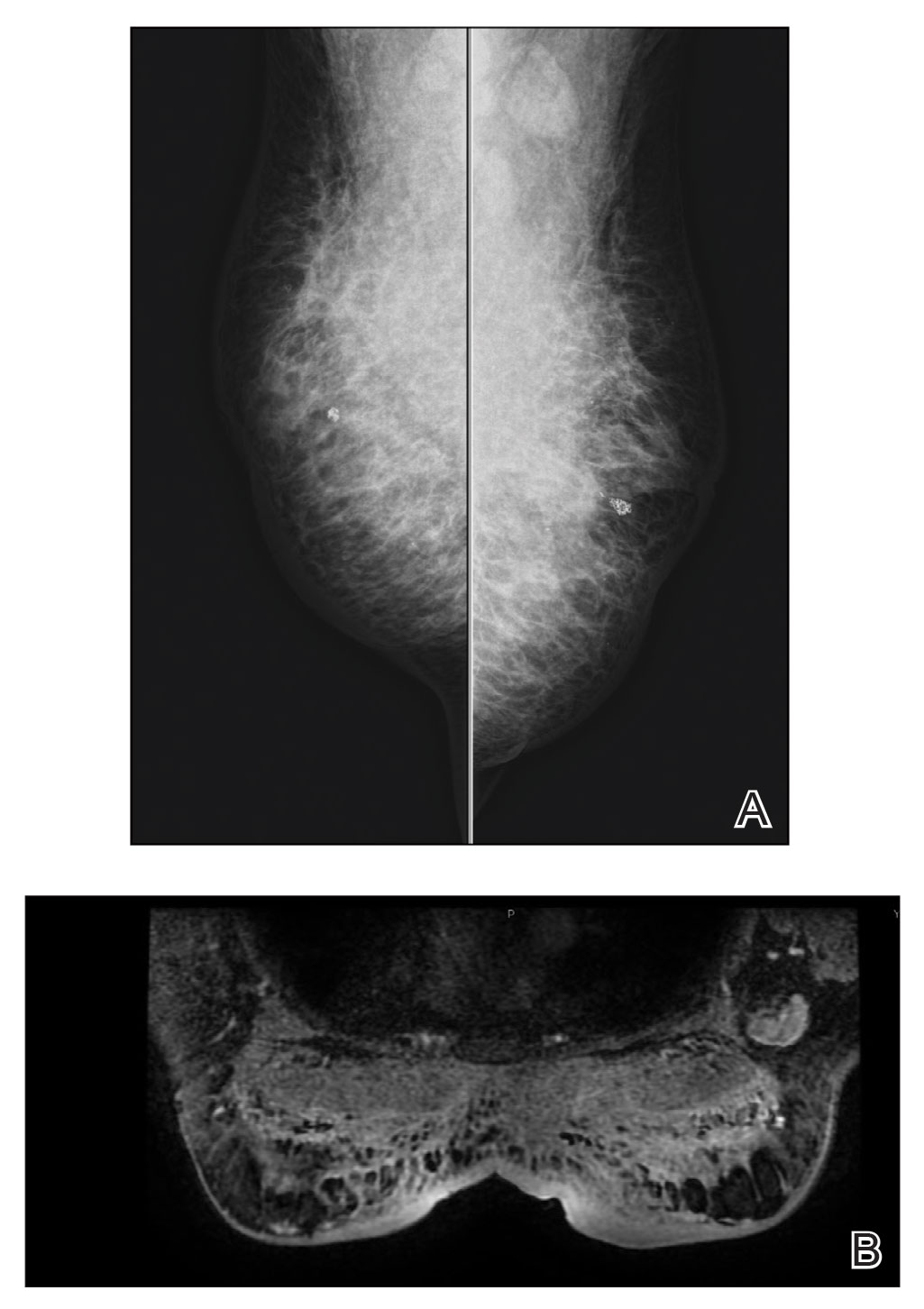

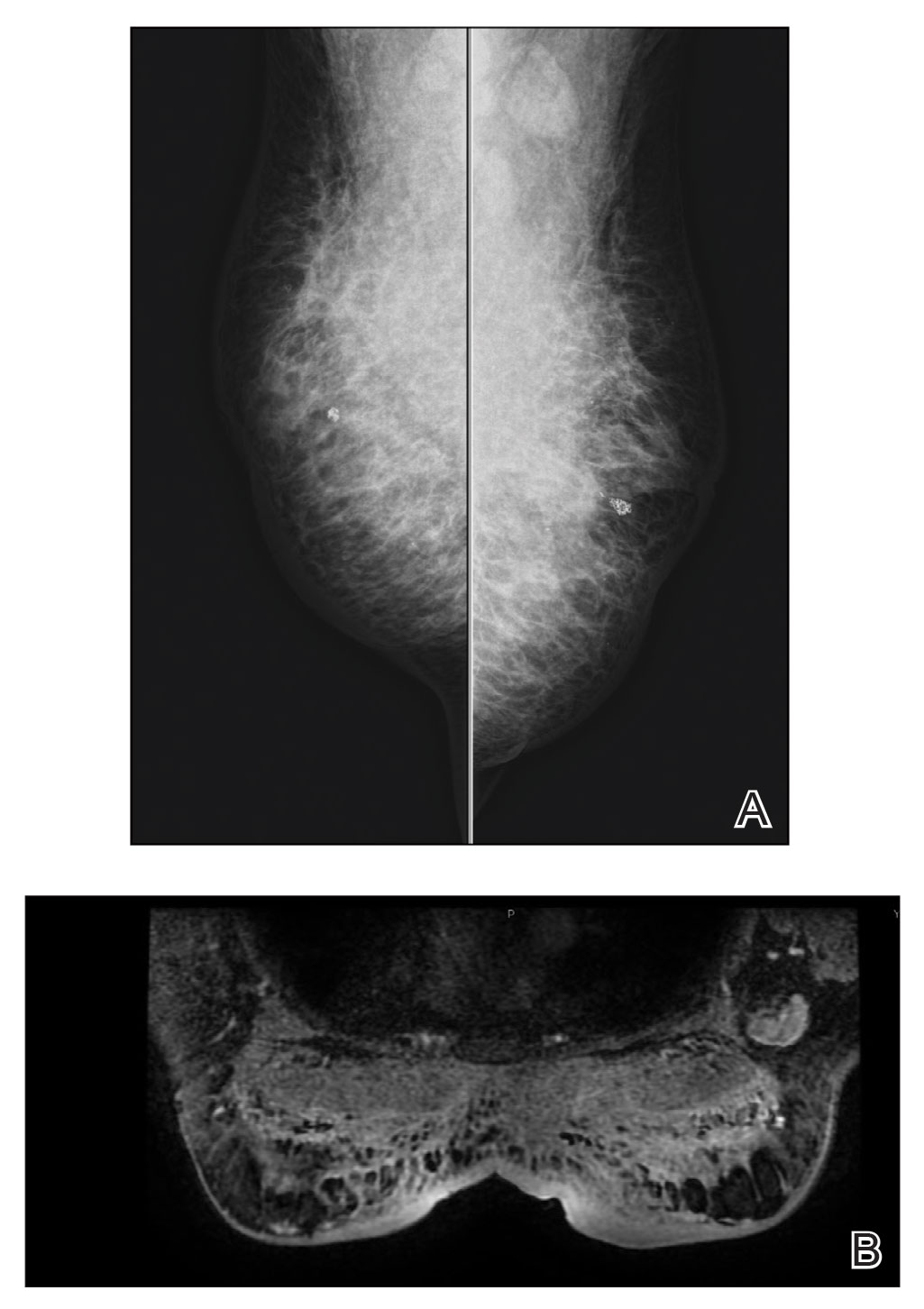

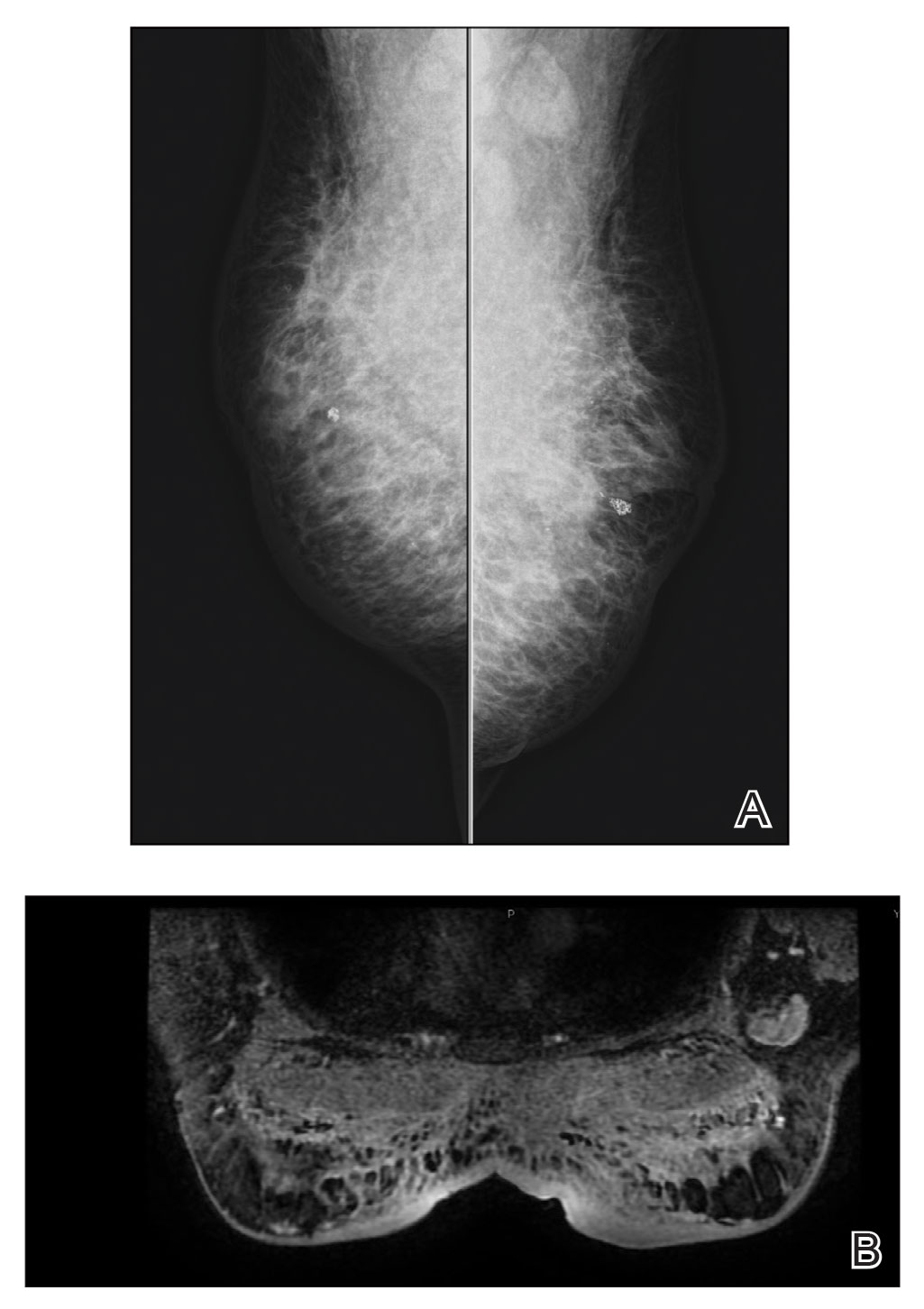

Mammography of both breasts revealed a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) score of 4 with a suspicious abnormality (ie, diffuse edema of the breast, multiple calcifications in a nonspecific pattern, oil cysts with calcifications, and bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy with a diameter of 2.5 cm and a thick and irregular cortex)(Figure 2A). Ultrasonography of both breasts revealed an inflammatory breast. Magnetic resonance imaging showed similar findings with diffuse edema and a heterogeneous appearance. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse contrast enhancement in both breasts extending to the pectoral muscles and axillary regions, consistent with inflammatory changes (Figure 2B).

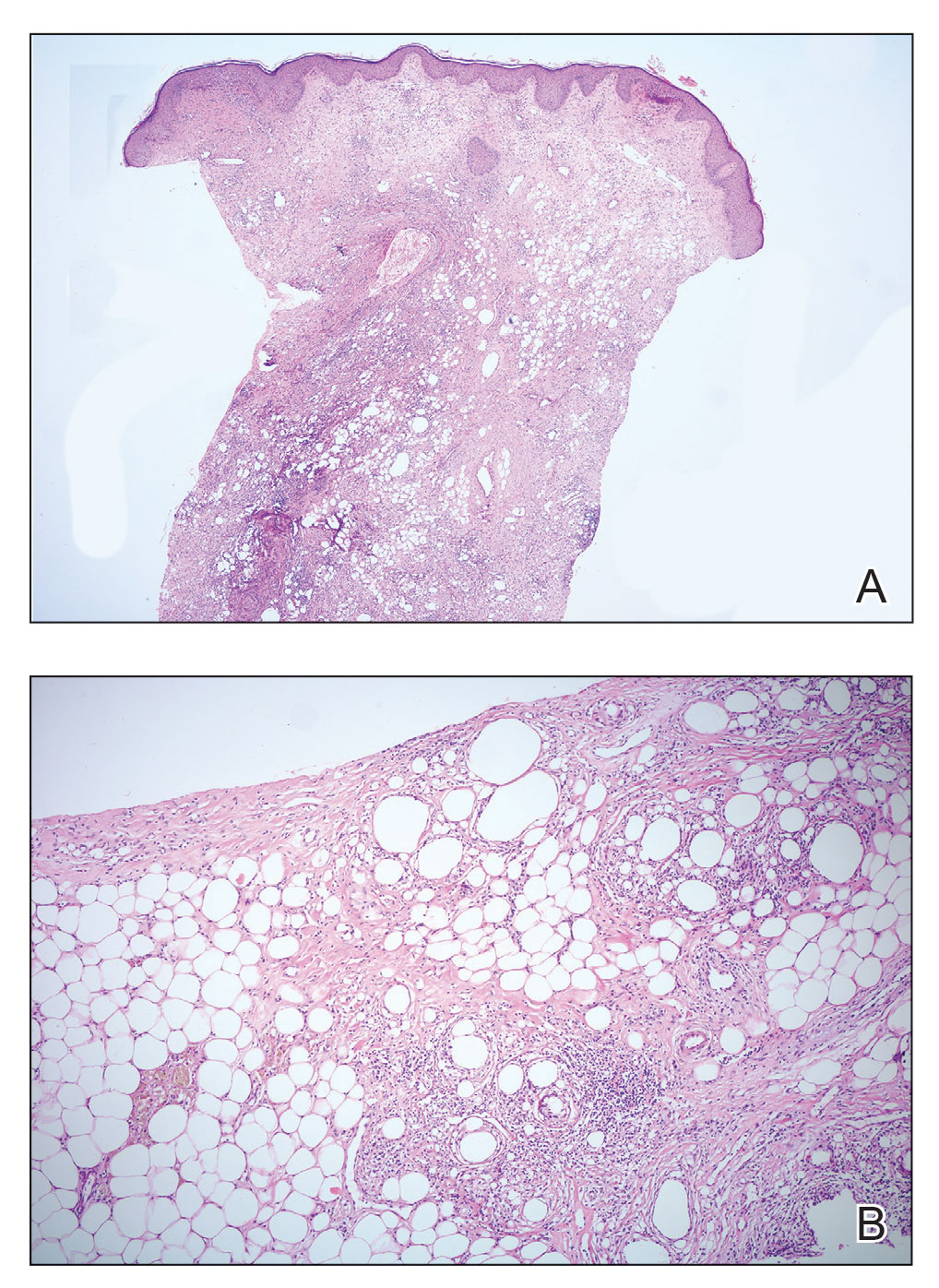

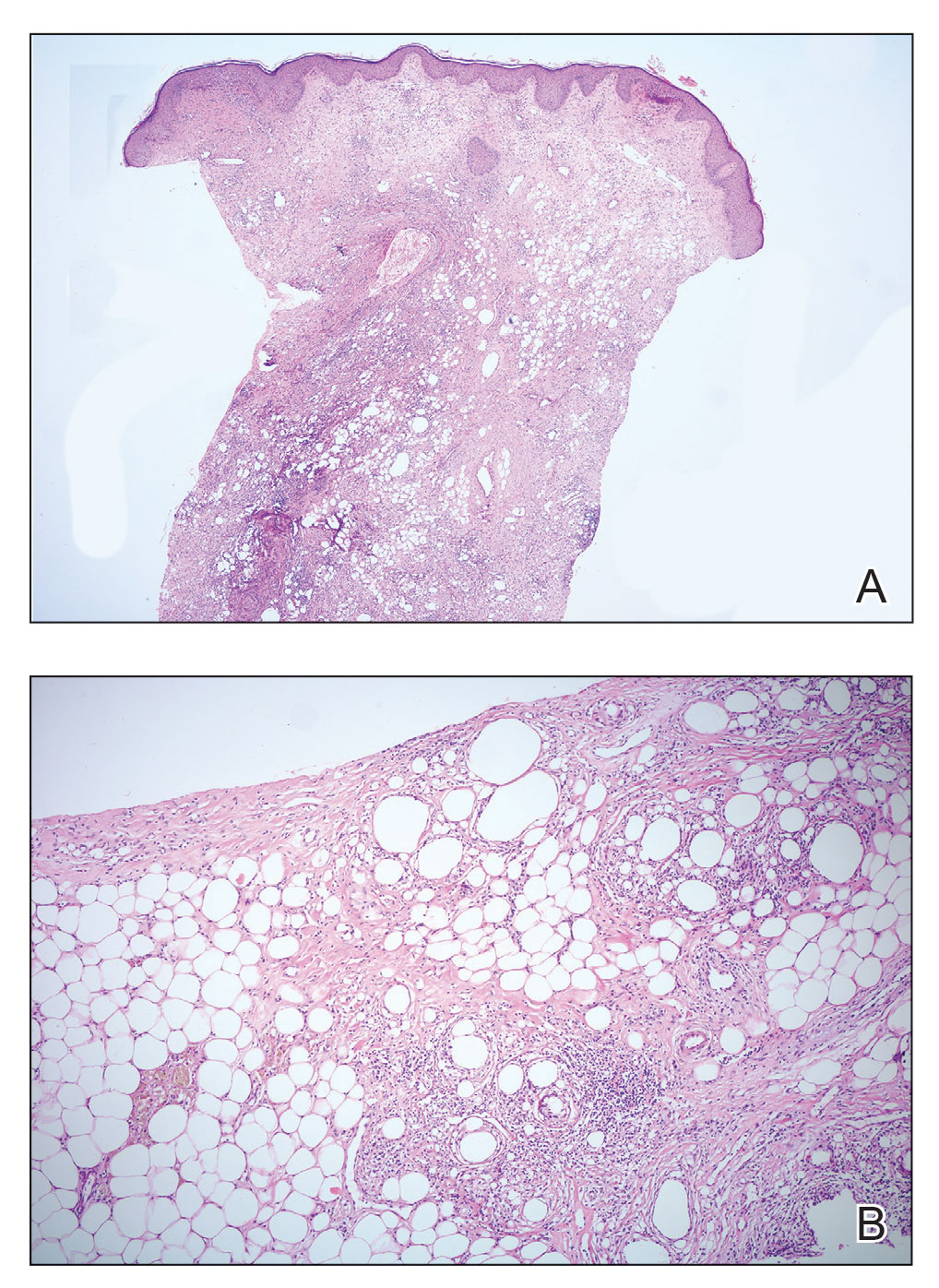

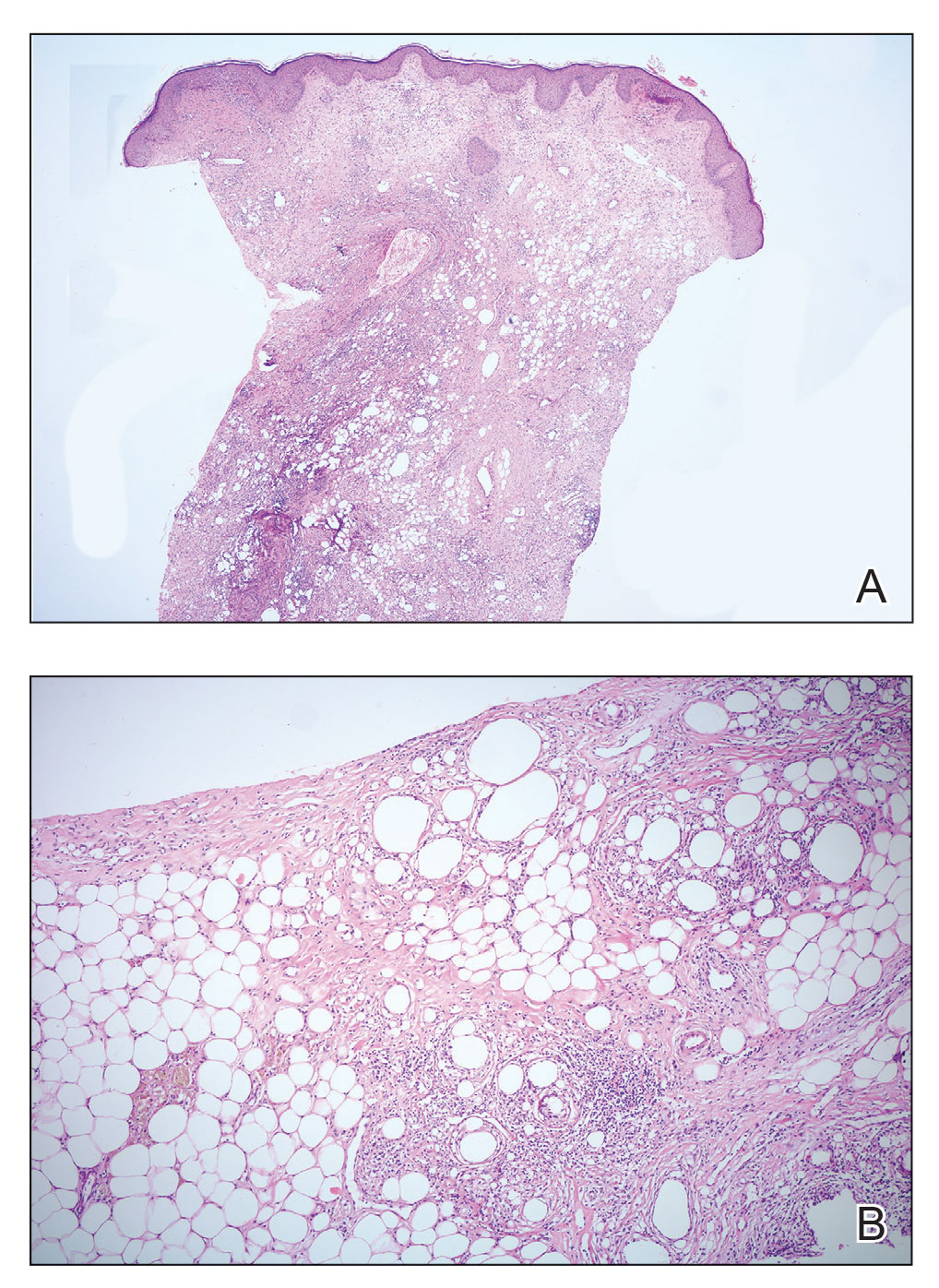

Because of difficulty differentiating inflammation and an infiltrating tumor, histopathologic examination was recommended by radiology. Results from a 5-mm punch biopsy from the right breast yielded the following differential diagnoses: cellulitis, panniculitis, inflammatory breast cancer, subcutaneous fat necrosis, and paraffinoma. Histopathologic examination of the skin revealed a normal epidermis and a dense inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising lymphocytes and monocytes in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Marked fibrosis also was noted in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Lipophagic fat necrosis accompanied by a variable inflammatory cell infiltrate consisted of histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure 3A). Pankeratin immunostaining was negative. Fat necrosis was present in a biopsy specimen obtained from the right breast; no signs of malignancy were present (Figure 3B). Fine-needle aspiration of the axillary lymph nodes was benign. Given these histopathologic findings, malignancy was excluded from the differential diagnosis. Paraffinoma also was ruled out because the patient insistently denied any history of fat or filler injection.

Based on the clinical, histopathologic, and radiologic findings, as well as the history of minor trauma due to wax hair removal, a diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast was made. Intervention was not recommended by the plastic surgeons who subsequently evaluated the patient, because the additional trauma may aggravate the lesion. He was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

At 6-month follow-up, there was marked reduction in the erythema and edema but no notable improvement of the induration. A potent topical steroid was added to the treatment, but only slight regression of the induration was observed.

The normal male breast is comprised of fat and a few secretory ducts.6 Gynecomastia and breast cancer are the 2 most common conditions of the male breast; fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. In a study of 236 male patients with breast disease, only 5 had fat necrosis.7

Fat necrosis of the breast can be observed with various clinical and radiological presentations. Subcutaneous nodules, skin retraction and thickening, local skin depression, and ecchymosis are the more common presentations of fat necrosis.3-5 In our case, the first symptoms of disease were similar to those seen in cellulitis. The presentation of fat necrosis–like cellulitis has been described only rarely in the medical literature. Haikin et al5 reported a case of fat necrosis of the leg in a child that presented with cellulitis followed by induration, which did not respond to antibiotics, as was the case with our patient.5

Blunt trauma, breast reduction surgery, and breast augmentation surgery can cause fat necrosis of the breast1,4; in some cases, the cause cannot be determined.8 The only pertinent history in our patient was wax hair removal. Fat necrosis was an unexpected complication, but hair removal can be considered minor trauma; however, this is not commonly reported in the literature following hair removal with wax. In a study that reviewed diseases of the male breast, the investigators observed that all male patients with fat necrosis had pseudogynecomastia (adipomastia).7 Although our patient’s entire anterior trunk was epilated, only the breast was affected. This situation might be explained by underlying gynecomastia because fat necrosis is common in areas of the body where subcutaneous fat tissue is dense.

Fat necrosis of the breast can be mistaken—both clinically and radiologically—for malignancy, such as in our case. Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast should be a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, histopathologic confirmation of the lesion is imperative.9

In conclusion, fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. The condition can present as cellulitis. Hair removal with wax might be a cause of fat necrosis. Because breast cancer and fat necrosis can exhibit clinical and radiologic similarities, the diagnosis of fat necrosis should be confirmed by histopathologic analysis in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings.

- Tan PH, Lai LM, Carrington EV, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast—a review. Breast. 2006;15:313-318. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2005.07.003

- Silverstone M. Fat necrosis of the breast with report of a case in a male. Br J Surg. 1949;37:49-52. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003714508

- Akyol M, Kayali A, Yildirim N. Traumatic fat necrosis of male breast. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:954-956. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.05.009

- Crawford EA, King JJ, Fox EJ, et al. Symptomatic fat necrosis and lipoatrophy of the posterior pelvis following trauma. Orthopedics. 2009;32:444. doi:10.3928/01477447-20090511-25

- Haikin Herzberger E, Aviner S, Cherniavsky E. Posttraumatic fat necrosis presented as cellulitis of the leg. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:672397. doi:10.1155/2012/672397

- Michels LG, Gold RH, Arndt RD. Radiography of gynecomastia and other disorders of the male breast. Radiology. 1977;122:117-122. doi:10.1148/122.1.117

- Günhan-Bilgen I, Bozkaya H, Ustün E, et al. Male breast disease: clinical, mammographic, and ultrasonographic features. Eur J Radiol. 2002;43:246-255. doi:10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00483-1

- Chala LF, de Barros N, de Camargo Moraes P, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast: mammographic, sonographic, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2004;33:106-126. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2004.01.001

- Pullyblank AM, Davies JD, Basten J, et al. Fat necrosis of the female breast—Hadfield re-visited. Breast. 2001;10:388-391. doi:10.1054/brst.2000.0287

To the Editor:

Fat necrosis of the breast is a benign inflammatory disease of adipose tissue commonly observed after trauma in the female breast during the perimenopausal period.1 Fat necrosis of the male breast is rare, first described by Silverstone2 in 1949; the condition usually presents with unilateral, painful or asymptomatic, firm nodules, which in rare cases are observed as skin retraction and thickening, ecchymosis, erythematous plaque–like cellulitis, local depression, and/or discoloration of the breast skin.3-5

Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the male breast may need to be confirmed via biopsy in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings because the condition can mimic breast cancer.1 We report a case of bilateral fat necrosis of the breast mimicking breast cancer following wax hair removal.

A 42-year-old man presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation of redness, swelling, and hardness of the skin of both breasts of 3 weeks’ duration. The patient had a history of wax hair removal of the entire anterior aspect of the body. He reported an erythematous, edematous, warm plaque that developed on the breasts 2 days after waxing. The plaque did not respond to antibiotics. The swelling and induration progressed over the 2 weeks after the patient was waxed. The patient had no family history of breast cancer. He had a standing diagnosis of gynecomastia. He denied any history of fat or filler injection in the affected area.

Dermatologic examination revealed erythematous, edematous, indurated, asymptomatic plaques with a peau d’orange appearance on the bilateral pectoral and presternal region. Minimal retraction of the right areola was noted (Figure 1). The bilateral axillary lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory results including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (108 mm/h [reference range, 2–20 mm/h]), C-reactive protein (9.2 mg/dL [reference range, >0.5 mg/dL]), and ferritin levels (645

Mammography of both breasts revealed a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) score of 4 with a suspicious abnormality (ie, diffuse edema of the breast, multiple calcifications in a nonspecific pattern, oil cysts with calcifications, and bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy with a diameter of 2.5 cm and a thick and irregular cortex)(Figure 2A). Ultrasonography of both breasts revealed an inflammatory breast. Magnetic resonance imaging showed similar findings with diffuse edema and a heterogeneous appearance. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse contrast enhancement in both breasts extending to the pectoral muscles and axillary regions, consistent with inflammatory changes (Figure 2B).

Because of difficulty differentiating inflammation and an infiltrating tumor, histopathologic examination was recommended by radiology. Results from a 5-mm punch biopsy from the right breast yielded the following differential diagnoses: cellulitis, panniculitis, inflammatory breast cancer, subcutaneous fat necrosis, and paraffinoma. Histopathologic examination of the skin revealed a normal epidermis and a dense inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising lymphocytes and monocytes in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Marked fibrosis also was noted in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Lipophagic fat necrosis accompanied by a variable inflammatory cell infiltrate consisted of histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure 3A). Pankeratin immunostaining was negative. Fat necrosis was present in a biopsy specimen obtained from the right breast; no signs of malignancy were present (Figure 3B). Fine-needle aspiration of the axillary lymph nodes was benign. Given these histopathologic findings, malignancy was excluded from the differential diagnosis. Paraffinoma also was ruled out because the patient insistently denied any history of fat or filler injection.

Based on the clinical, histopathologic, and radiologic findings, as well as the history of minor trauma due to wax hair removal, a diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast was made. Intervention was not recommended by the plastic surgeons who subsequently evaluated the patient, because the additional trauma may aggravate the lesion. He was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

At 6-month follow-up, there was marked reduction in the erythema and edema but no notable improvement of the induration. A potent topical steroid was added to the treatment, but only slight regression of the induration was observed.

The normal male breast is comprised of fat and a few secretory ducts.6 Gynecomastia and breast cancer are the 2 most common conditions of the male breast; fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. In a study of 236 male patients with breast disease, only 5 had fat necrosis.7

Fat necrosis of the breast can be observed with various clinical and radiological presentations. Subcutaneous nodules, skin retraction and thickening, local skin depression, and ecchymosis are the more common presentations of fat necrosis.3-5 In our case, the first symptoms of disease were similar to those seen in cellulitis. The presentation of fat necrosis–like cellulitis has been described only rarely in the medical literature. Haikin et al5 reported a case of fat necrosis of the leg in a child that presented with cellulitis followed by induration, which did not respond to antibiotics, as was the case with our patient.5

Blunt trauma, breast reduction surgery, and breast augmentation surgery can cause fat necrosis of the breast1,4; in some cases, the cause cannot be determined.8 The only pertinent history in our patient was wax hair removal. Fat necrosis was an unexpected complication, but hair removal can be considered minor trauma; however, this is not commonly reported in the literature following hair removal with wax. In a study that reviewed diseases of the male breast, the investigators observed that all male patients with fat necrosis had pseudogynecomastia (adipomastia).7 Although our patient’s entire anterior trunk was epilated, only the breast was affected. This situation might be explained by underlying gynecomastia because fat necrosis is common in areas of the body where subcutaneous fat tissue is dense.

Fat necrosis of the breast can be mistaken—both clinically and radiologically—for malignancy, such as in our case. Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast should be a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, histopathologic confirmation of the lesion is imperative.9

In conclusion, fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. The condition can present as cellulitis. Hair removal with wax might be a cause of fat necrosis. Because breast cancer and fat necrosis can exhibit clinical and radiologic similarities, the diagnosis of fat necrosis should be confirmed by histopathologic analysis in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings.

To the Editor:

Fat necrosis of the breast is a benign inflammatory disease of adipose tissue commonly observed after trauma in the female breast during the perimenopausal period.1 Fat necrosis of the male breast is rare, first described by Silverstone2 in 1949; the condition usually presents with unilateral, painful or asymptomatic, firm nodules, which in rare cases are observed as skin retraction and thickening, ecchymosis, erythematous plaque–like cellulitis, local depression, and/or discoloration of the breast skin.3-5

Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the male breast may need to be confirmed via biopsy in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings because the condition can mimic breast cancer.1 We report a case of bilateral fat necrosis of the breast mimicking breast cancer following wax hair removal.

A 42-year-old man presented to our outpatient dermatology clinic for evaluation of redness, swelling, and hardness of the skin of both breasts of 3 weeks’ duration. The patient had a history of wax hair removal of the entire anterior aspect of the body. He reported an erythematous, edematous, warm plaque that developed on the breasts 2 days after waxing. The plaque did not respond to antibiotics. The swelling and induration progressed over the 2 weeks after the patient was waxed. The patient had no family history of breast cancer. He had a standing diagnosis of gynecomastia. He denied any history of fat or filler injection in the affected area.

Dermatologic examination revealed erythematous, edematous, indurated, asymptomatic plaques with a peau d’orange appearance on the bilateral pectoral and presternal region. Minimal retraction of the right areola was noted (Figure 1). The bilateral axillary lymph nodes were palpable.

Laboratory results including erythrocyte sedimentation rate (108 mm/h [reference range, 2–20 mm/h]), C-reactive protein (9.2 mg/dL [reference range, >0.5 mg/dL]), and ferritin levels (645

Mammography of both breasts revealed a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) score of 4 with a suspicious abnormality (ie, diffuse edema of the breast, multiple calcifications in a nonspecific pattern, oil cysts with calcifications, and bilateral axillary lymphadenopathy with a diameter of 2.5 cm and a thick and irregular cortex)(Figure 2A). Ultrasonography of both breasts revealed an inflammatory breast. Magnetic resonance imaging showed similar findings with diffuse edema and a heterogeneous appearance. Contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging showed diffuse contrast enhancement in both breasts extending to the pectoral muscles and axillary regions, consistent with inflammatory changes (Figure 2B).

Because of difficulty differentiating inflammation and an infiltrating tumor, histopathologic examination was recommended by radiology. Results from a 5-mm punch biopsy from the right breast yielded the following differential diagnoses: cellulitis, panniculitis, inflammatory breast cancer, subcutaneous fat necrosis, and paraffinoma. Histopathologic examination of the skin revealed a normal epidermis and a dense inflammatory cell infiltrate comprising lymphocytes and monocytes in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Marked fibrosis also was noted in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Lipophagic fat necrosis accompanied by a variable inflammatory cell infiltrate consisted of histiocytes and neutrophils (Figure 3A). Pankeratin immunostaining was negative. Fat necrosis was present in a biopsy specimen obtained from the right breast; no signs of malignancy were present (Figure 3B). Fine-needle aspiration of the axillary lymph nodes was benign. Given these histopathologic findings, malignancy was excluded from the differential diagnosis. Paraffinoma also was ruled out because the patient insistently denied any history of fat or filler injection.

Based on the clinical, histopathologic, and radiologic findings, as well as the history of minor trauma due to wax hair removal, a diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast was made. Intervention was not recommended by the plastic surgeons who subsequently evaluated the patient, because the additional trauma may aggravate the lesion. He was treated with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

At 6-month follow-up, there was marked reduction in the erythema and edema but no notable improvement of the induration. A potent topical steroid was added to the treatment, but only slight regression of the induration was observed.

The normal male breast is comprised of fat and a few secretory ducts.6 Gynecomastia and breast cancer are the 2 most common conditions of the male breast; fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. In a study of 236 male patients with breast disease, only 5 had fat necrosis.7

Fat necrosis of the breast can be observed with various clinical and radiological presentations. Subcutaneous nodules, skin retraction and thickening, local skin depression, and ecchymosis are the more common presentations of fat necrosis.3-5 In our case, the first symptoms of disease were similar to those seen in cellulitis. The presentation of fat necrosis–like cellulitis has been described only rarely in the medical literature. Haikin et al5 reported a case of fat necrosis of the leg in a child that presented with cellulitis followed by induration, which did not respond to antibiotics, as was the case with our patient.5

Blunt trauma, breast reduction surgery, and breast augmentation surgery can cause fat necrosis of the breast1,4; in some cases, the cause cannot be determined.8 The only pertinent history in our patient was wax hair removal. Fat necrosis was an unexpected complication, but hair removal can be considered minor trauma; however, this is not commonly reported in the literature following hair removal with wax. In a study that reviewed diseases of the male breast, the investigators observed that all male patients with fat necrosis had pseudogynecomastia (adipomastia).7 Although our patient’s entire anterior trunk was epilated, only the breast was affected. This situation might be explained by underlying gynecomastia because fat necrosis is common in areas of the body where subcutaneous fat tissue is dense.

Fat necrosis of the breast can be mistaken—both clinically and radiologically—for malignancy, such as in our case. Diagnosis of fat necrosis of the breast should be a diagnosis of exclusion; therefore, histopathologic confirmation of the lesion is imperative.9

In conclusion, fat necrosis of the male breast is rare. The condition can present as cellulitis. Hair removal with wax might be a cause of fat necrosis. Because breast cancer and fat necrosis can exhibit clinical and radiologic similarities, the diagnosis of fat necrosis should be confirmed by histopathologic analysis in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings.

- Tan PH, Lai LM, Carrington EV, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast—a review. Breast. 2006;15:313-318. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2005.07.003

- Silverstone M. Fat necrosis of the breast with report of a case in a male. Br J Surg. 1949;37:49-52. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003714508

- Akyol M, Kayali A, Yildirim N. Traumatic fat necrosis of male breast. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:954-956. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.05.009

- Crawford EA, King JJ, Fox EJ, et al. Symptomatic fat necrosis and lipoatrophy of the posterior pelvis following trauma. Orthopedics. 2009;32:444. doi:10.3928/01477447-20090511-25

- Haikin Herzberger E, Aviner S, Cherniavsky E. Posttraumatic fat necrosis presented as cellulitis of the leg. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:672397. doi:10.1155/2012/672397

- Michels LG, Gold RH, Arndt RD. Radiography of gynecomastia and other disorders of the male breast. Radiology. 1977;122:117-122. doi:10.1148/122.1.117

- Günhan-Bilgen I, Bozkaya H, Ustün E, et al. Male breast disease: clinical, mammographic, and ultrasonographic features. Eur J Radiol. 2002;43:246-255. doi:10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00483-1

- Chala LF, de Barros N, de Camargo Moraes P, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast: mammographic, sonographic, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2004;33:106-126. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2004.01.001

- Pullyblank AM, Davies JD, Basten J, et al. Fat necrosis of the female breast—Hadfield re-visited. Breast. 2001;10:388-391. doi:10.1054/brst.2000.0287

- Tan PH, Lai LM, Carrington EV, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast—a review. Breast. 2006;15:313-318. doi:10.1016/j.breast.2005.07.003

- Silverstone M. Fat necrosis of the breast with report of a case in a male. Br J Surg. 1949;37:49-52. doi:10.1002/bjs.18003714508

- Akyol M, Kayali A, Yildirim N. Traumatic fat necrosis of male breast. Clin Imaging. 2013;37:954-956. doi:10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.05.009

- Crawford EA, King JJ, Fox EJ, et al. Symptomatic fat necrosis and lipoatrophy of the posterior pelvis following trauma. Orthopedics. 2009;32:444. doi:10.3928/01477447-20090511-25

- Haikin Herzberger E, Aviner S, Cherniavsky E. Posttraumatic fat necrosis presented as cellulitis of the leg. Case Rep Pediatr. 2012;2012:672397. doi:10.1155/2012/672397

- Michels LG, Gold RH, Arndt RD. Radiography of gynecomastia and other disorders of the male breast. Radiology. 1977;122:117-122. doi:10.1148/122.1.117

- Günhan-Bilgen I, Bozkaya H, Ustün E, et al. Male breast disease: clinical, mammographic, and ultrasonographic features. Eur J Radiol. 2002;43:246-255. doi:10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00483-1

- Chala LF, de Barros N, de Camargo Moraes P, et al. Fat necrosis of the breast: mammographic, sonographic, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol. 2004;33:106-126. doi:10.1067/j.cpradiol.2004.01.001

- Pullyblank AM, Davies JD, Basten J, et al. Fat necrosis of the female breast—Hadfield re-visited. Breast. 2001;10:388-391. doi:10.1054/brst.2000.0287

Practice Points

- Fat necrosis of the breast can be mistaken—both clinically and radiologically—for malignancy; therefore, diagnosis should be confirmed by histopathology in conjunction with clinical and radiologic findings.

- Fat necrosis of the male breast is rare, and hair removal with wax may be a rare cause of the disease.

Asymptomatic Erythematous Plaques on the Scalp and Face

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Faciale

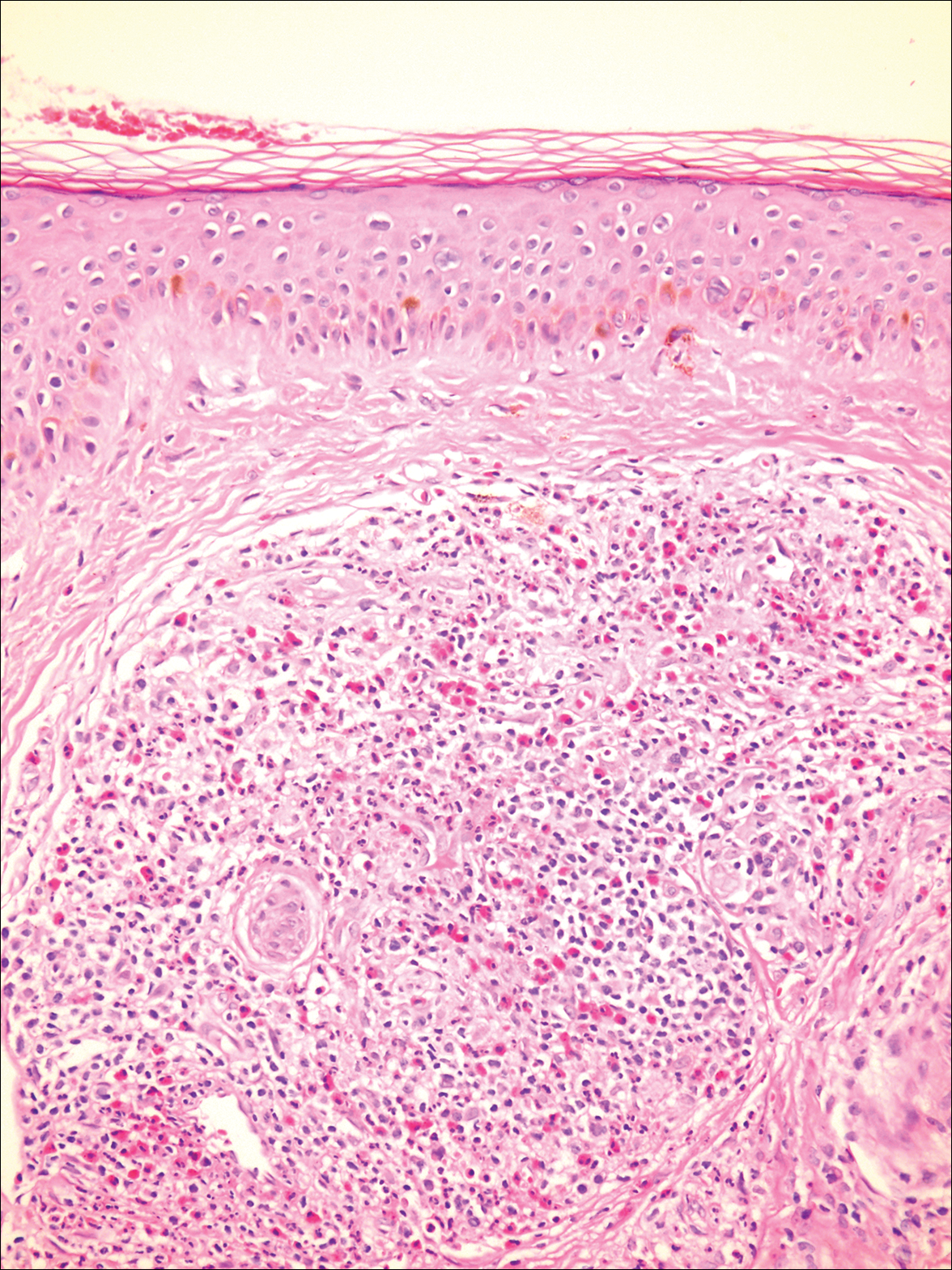

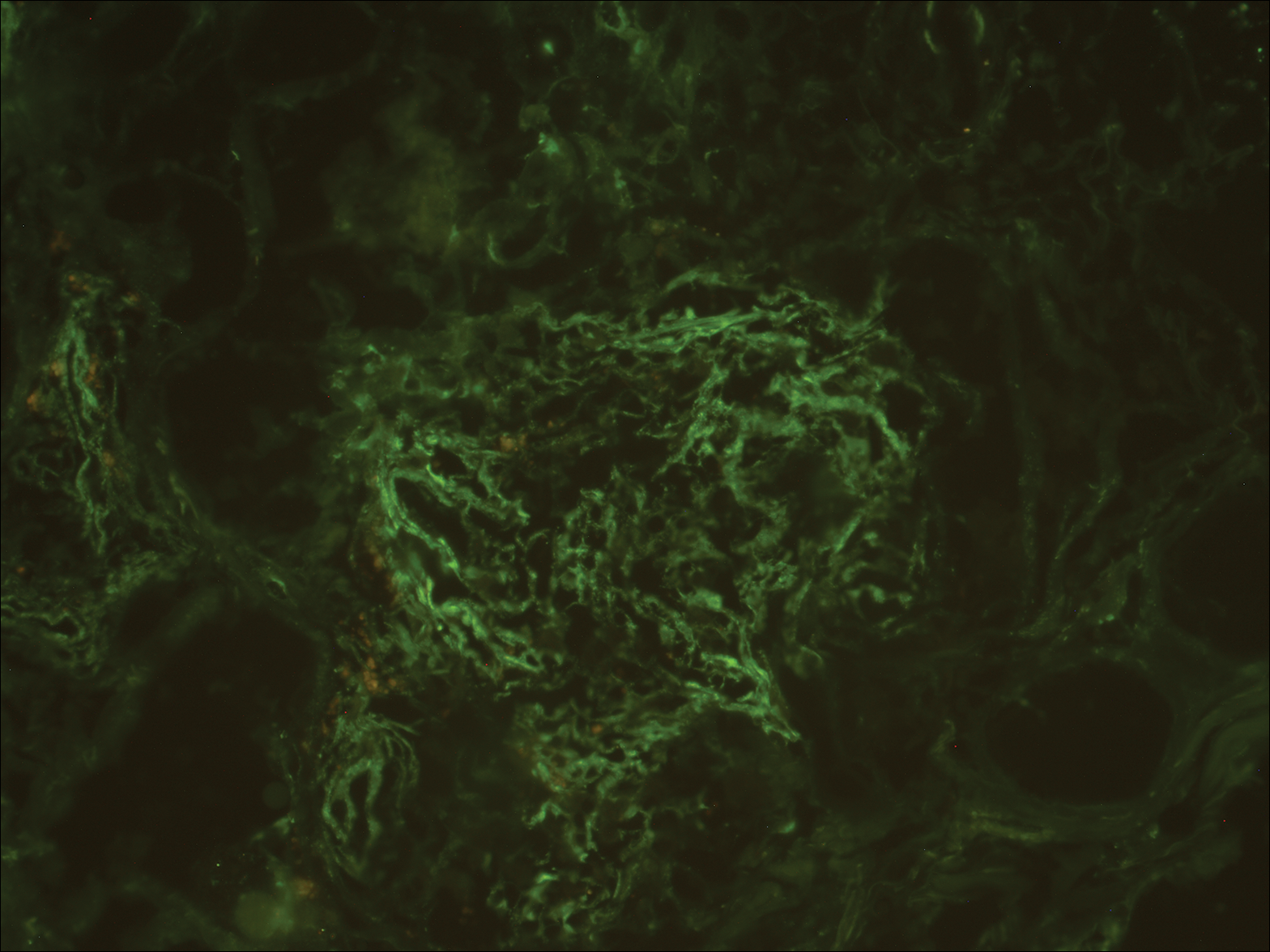

A biopsy from a scalp lesion showed an intense mixed inflammatory infiltrate mainly consisting of eosinophils, but lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells also were present. A grenz zone was observed between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis. Perivascular infiltrates were penetrating vessel walls, and hyalinization of the vessel walls also was seen (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated IgG positivity on vessel walls (Figure 2). A diagnosis of granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions was made. Twice daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% was started, but after a 10-month course of treatment, there was no notable difference in the lesions.

Granuloma faciale (GF) is an uncommon benign dermatosis of unknown pathogenesis characterized by erythematous, brown, or violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules. Granuloma faciale lesions can be solitary or multiple as well as disseminated and most often occur on the face. Predilection sites include the nose, periauricular area, cheeks, forehead, eyelids, and ears; however, lesions also have been reported to occur in extrafacial areas such as the trunk, arms, and legs.1-4 In our patient, multiple plaques were seen on the scalp. Facial lesions usually precede extrafacial lesions, which may present months to several years after the appearance of facial disease; however, according to our patient's history his scalp lesions appeared before the facial lesions.

The differential diagnoses for GF mainly include erythema elevatum diutinum, cutaneous sarcoidosis, cutaneous lymphoma, lupus, basal cell carcinoma, and cutaneous pseudolymphoma.5 Diagnosis may be established based on a combination of clinical features and skin biopsy results. On histopathologic examination, small-vessel vasculitis usually is present with an infiltrate predominantly consisting of neutrophils and eosinophils.6

It has been suggested that actinic damage plays a role in the etiology of GF.7 The pathogenesis is uncertain, but it is thought that immunophenotypic and molecular analysis of the dermal infiltrate in GF reveals that most lymphocytes are clonally expanded and the process is mediated by interferon gamma.7 Tacrolimus acts by binding and inactivating calcineurin and thus blocking T-cell activation and proliferation, so it is not surprising that topical tacrolimus has been shown to be useful in the management of this condition.8

- Leite I, Moreira A, Guedes R, et al. Granuloma faciale of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Radotra BD, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1284-1286.

- Castellano-Howard L, Fairbee SI, Hogan DJ, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case and response to treatment. Cutis. 2001;67:413-415.

- Inanir I, Alvur Y. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:360-362.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Koplon BS, Wood MG. Granuloma faciale. first reported case in a Negro. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:188-192.

- Ludwig E, Allam JP, Bieber T, et al. New treatment modalities for granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:634-637.

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Faciale

A biopsy from a scalp lesion showed an intense mixed inflammatory infiltrate mainly consisting of eosinophils, but lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells also were present. A grenz zone was observed between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis. Perivascular infiltrates were penetrating vessel walls, and hyalinization of the vessel walls also was seen (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated IgG positivity on vessel walls (Figure 2). A diagnosis of granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions was made. Twice daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% was started, but after a 10-month course of treatment, there was no notable difference in the lesions.

Granuloma faciale (GF) is an uncommon benign dermatosis of unknown pathogenesis characterized by erythematous, brown, or violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules. Granuloma faciale lesions can be solitary or multiple as well as disseminated and most often occur on the face. Predilection sites include the nose, periauricular area, cheeks, forehead, eyelids, and ears; however, lesions also have been reported to occur in extrafacial areas such as the trunk, arms, and legs.1-4 In our patient, multiple plaques were seen on the scalp. Facial lesions usually precede extrafacial lesions, which may present months to several years after the appearance of facial disease; however, according to our patient's history his scalp lesions appeared before the facial lesions.

The differential diagnoses for GF mainly include erythema elevatum diutinum, cutaneous sarcoidosis, cutaneous lymphoma, lupus, basal cell carcinoma, and cutaneous pseudolymphoma.5 Diagnosis may be established based on a combination of clinical features and skin biopsy results. On histopathologic examination, small-vessel vasculitis usually is present with an infiltrate predominantly consisting of neutrophils and eosinophils.6

It has been suggested that actinic damage plays a role in the etiology of GF.7 The pathogenesis is uncertain, but it is thought that immunophenotypic and molecular analysis of the dermal infiltrate in GF reveals that most lymphocytes are clonally expanded and the process is mediated by interferon gamma.7 Tacrolimus acts by binding and inactivating calcineurin and thus blocking T-cell activation and proliferation, so it is not surprising that topical tacrolimus has been shown to be useful in the management of this condition.8

The Diagnosis: Granuloma Faciale

A biopsy from a scalp lesion showed an intense mixed inflammatory infiltrate mainly consisting of eosinophils, but lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, and plasma cells also were present. A grenz zone was observed between the dermal infiltrate and epidermis. Perivascular infiltrates were penetrating vessel walls, and hyalinization of the vessel walls also was seen (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence demonstrated IgG positivity on vessel walls (Figure 2). A diagnosis of granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions was made. Twice daily application of tacrolimus ointment 0.1% was started, but after a 10-month course of treatment, there was no notable difference in the lesions.

Granuloma faciale (GF) is an uncommon benign dermatosis of unknown pathogenesis characterized by erythematous, brown, or violaceous papules, plaques, or nodules. Granuloma faciale lesions can be solitary or multiple as well as disseminated and most often occur on the face. Predilection sites include the nose, periauricular area, cheeks, forehead, eyelids, and ears; however, lesions also have been reported to occur in extrafacial areas such as the trunk, arms, and legs.1-4 In our patient, multiple plaques were seen on the scalp. Facial lesions usually precede extrafacial lesions, which may present months to several years after the appearance of facial disease; however, according to our patient's history his scalp lesions appeared before the facial lesions.

The differential diagnoses for GF mainly include erythema elevatum diutinum, cutaneous sarcoidosis, cutaneous lymphoma, lupus, basal cell carcinoma, and cutaneous pseudolymphoma.5 Diagnosis may be established based on a combination of clinical features and skin biopsy results. On histopathologic examination, small-vessel vasculitis usually is present with an infiltrate predominantly consisting of neutrophils and eosinophils.6

It has been suggested that actinic damage plays a role in the etiology of GF.7 The pathogenesis is uncertain, but it is thought that immunophenotypic and molecular analysis of the dermal infiltrate in GF reveals that most lymphocytes are clonally expanded and the process is mediated by interferon gamma.7 Tacrolimus acts by binding and inactivating calcineurin and thus blocking T-cell activation and proliferation, so it is not surprising that topical tacrolimus has been shown to be useful in the management of this condition.8

- Leite I, Moreira A, Guedes R, et al. Granuloma faciale of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Radotra BD, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1284-1286.

- Castellano-Howard L, Fairbee SI, Hogan DJ, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case and response to treatment. Cutis. 2001;67:413-415.

- Inanir I, Alvur Y. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:360-362.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Koplon BS, Wood MG. Granuloma faciale. first reported case in a Negro. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:188-192.

- Ludwig E, Allam JP, Bieber T, et al. New treatment modalities for granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:634-637.

- Leite I, Moreira A, Guedes R, et al. Granuloma faciale of the scalp. Dermatol Online J. 2011;17:6.

- De D, Kanwar AJ, Radotra BD, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2007;21:1284-1286.

- Castellano-Howard L, Fairbee SI, Hogan DJ, et al. Extrafacial granuloma faciale: report of a case and response to treatment. Cutis. 2001;67:413-415.

- Inanir I, Alvur Y. Granuloma faciale with extrafacial lesions. Br J Dermatol. 2001;145:360-362.

- Ortonne N, Wechsler J, Bagot M, et al. Granuloma faciale: a clinicopathologic study of 66 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:1002-1009.

- LeBoit PE. Granuloma faciale: a diagnosis deserving of dignity. Am J Dermatopathol. 2002;24:440-443.

- Koplon BS, Wood MG. Granuloma faciale. first reported case in a Negro. Arch Dermatol. 1967;96:188-192.

- Ludwig E, Allam JP, Bieber T, et al. New treatment modalities for granuloma faciale. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:634-637.

An 84-year-old man presented with gradually enlarging, asymptomatic, erythematous to violaceous plaques on the face and scalp of 11 years' duration ranging in size from 0.5×0.5 cm to 10×8 cm. The plaques were unresponsive to treatment with topical steroids. The lesions were nontender with no associated bleeding, burning, or pruritus. The patient denied any trauma to the sites or systemic symptoms. He had a history of essential hypertension and benign prostatic hyperplasia and had been taking ramipril, tamsulosin, and dutasteride for 5 years. His medical history was otherwise unremarkable, and routine laboratory findings were within normal range.

Systemic Interferon Alfa Injections for the Treatment of a Giant Orf

Orf, also known as ecthyma contagiosum, is a common viral zoonotic infection caused by a parapoxvirus. It is widespread among small ruminants such as sheep and goats, and it can be transmitted to humans by close contact with infected animals or contaminated fomites. It usually manifests as vesiculoulcerative lesions or nodules on the inoculation sites, mostly on the hands, but other sites such as the head and scalp occasionally may be involved.1 We report the case of an orf that proliferated dramatically and became giant after total excision. It was successfully treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections and imiquimod cream.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging mass on the left hand that developed 4 weeks prior after close contact with a freshly slaughtered sheep during an Islamic holiday in Turkey. His medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which was diagnosed one year prior. The patient had been treated with systemic prednisolone and cyclophosphamide therapies, but his disease was in remission at the current presentation and he currently was not receiving any treatment. On physical examination, a 2-cm, exophytic, pinkish gray, weeping nodule was observed on the proximal aspect of the right thumb. Based on the clinical findings and typical anamnesis, a diagnosis of an orf was concluded. It was decided to monitor the patient without any intervention; however, because the lesion did not resolve and remained stable, he was referred to a plastic surgeon for surgical removal after 6 weeks of follow-up.

Histopathologic examination of the excision specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, massive capillary proliferation, and viral cytopathic changes in keratinocytes characterized by ballooning degeneration and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which was consistent with the clinical diagnosis of an orf. Unfortunately, the lesion relapsed rapidly following excision (Figure, A). Treatment with oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily) and imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) was initiated. However, this treatment was unsuccessful and was discontinued after 6 weeks, as the lesion kept growing, reaching a diameter of approximately 5 cm and becoming lobulated on the surface (Figure, B). Combination therapy was started with imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) and intralesional interferon alfa-2a injections (3 million IU twice weekly). The injections were so painful that the patient refused further therapy after only 2 injections. The therapy was switched from intralesional to systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon alfa-2a (3 million IU twice weekly) with concomitant imiquimod cream 5% 3 times weekly. This treatment was well tolerated by our patient with no notable side effects, except for mild fever on the night of each injection. Three weeks after the commencement of systemic injections, remarkable healing of the lesions with reduced size and exudation was noted. The frequency of injections was decreased to once weekly, which was then discontinued after 6 weeks when the lesion totally resolved (Figure, C). At 12 months’ follow-up, there were no signs of relapse.

Comment

Orf is an occupational disease that usually develops in farmers, butchers, and veterinarians; however, epidemic outbreaks of human orf are commonly observed in Turkey after the feast of sacrifice, as many individuals have close contact with the animals during sacrification.2 In Turkey, orf is well recognized by dermatologists, and clinical diagnosis usually is not difficult.

Human orf has a self-limited course in which lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, such as our patient with CLL, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant, requiring early and effective treatment. Treatment options for giant orf tumors in immunocompromised individuals include surgical excision,3 cryotherapy, topical imiquimod,4,5 topical or intralesional cidofovir,6 and intralesional interferon alfa injections.7 According to our clinical observations, surgical interventions for treatment of orfs usually cause a delay in the natural healing process; however, because surgical excision is a recommended treatment option for exophytic and recalcitrant orfs, we decided to treat our patient with surgical excision, which resulted in rapid recurrence and massive proliferation. A similar case of giant orf that was aggravated after surgery has been reported.8 In light of these cases, it is our opinion that treatment options other than surgery may be reasonable.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia may show features of both humoral and cell-mediated deficiency. Patients are known to be prone to viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and human papillomavirus. A giant orf infection on the background of CLL also has been described.9

Interferons were first discovered in 1957 and named after their ability to interfere with viral replication. They represent a family of cytokines that has an essential role in the innate immune response to virus infections. Because of their antiviral properties, recombinant forms of interferon alfa are widely used with success in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. A few other antiviral clinical applications of interferon alfa include infections caused by human herpesvirus 8 (the etiological agent in Kaposi sarcoma) and human papillomatosis virus (the etiological agent in juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis and condyloma acuminatum).10

In a report by Ran et al,7 intralesional interferon alfa injections were successfully used for treatment of giant orf lesions in an immunocompromised patient. As a result, we started treating the patient with intralesional interferon alfa-2a, but it was not well tolerated by our patient, as it was quite painful. We then decided to continue the therapy with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections, as we believed that it was a good option due to its antiviral, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic properties. With the experimental combined therapy of systemic interferon alfa-2a and topical imiquimod, our patient achieved a complete response in 9 weeks (3 weeks of twice weekly injections and then 6 weeks of once weekly injections) and had no relapses during 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of a giant orf treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections. Because intralesional injections are quite painful, systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon might be a good and safe alternative for recalcitrant orf lesions in immunocompromised patients. However, more studies and reports are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Gurel MS, Ozardali I, Bitiren M, et al. Giant orf on the nose. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:183-185.

- Uzel M, Sasmaz S, Bakaris S, et al. A viral infection of the hand commonly seen after the feast of sacrifice: human orf (orf of the hand). Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:653-657.

- Ballanger F, Barbarot S, Mollat C, et al. Two giant orf lesions in a heart/lung transplant patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:284-286.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Lederman ER, Green GM, DeGroot HE, et al. Progressive ORF virus infection in a patient with lymphoma: successful treatment using imiquimod. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e100-e103.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma–like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Key SJ, Catania J, Mustafa SF, et al. Unusual presentation of human giant orf (ecthyma contagiosum). J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1076-1078.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Friedman RM. Clinical uses of interferons. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:158-162.

Orf, also known as ecthyma contagiosum, is a common viral zoonotic infection caused by a parapoxvirus. It is widespread among small ruminants such as sheep and goats, and it can be transmitted to humans by close contact with infected animals or contaminated fomites. It usually manifests as vesiculoulcerative lesions or nodules on the inoculation sites, mostly on the hands, but other sites such as the head and scalp occasionally may be involved.1 We report the case of an orf that proliferated dramatically and became giant after total excision. It was successfully treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections and imiquimod cream.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging mass on the left hand that developed 4 weeks prior after close contact with a freshly slaughtered sheep during an Islamic holiday in Turkey. His medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which was diagnosed one year prior. The patient had been treated with systemic prednisolone and cyclophosphamide therapies, but his disease was in remission at the current presentation and he currently was not receiving any treatment. On physical examination, a 2-cm, exophytic, pinkish gray, weeping nodule was observed on the proximal aspect of the right thumb. Based on the clinical findings and typical anamnesis, a diagnosis of an orf was concluded. It was decided to monitor the patient without any intervention; however, because the lesion did not resolve and remained stable, he was referred to a plastic surgeon for surgical removal after 6 weeks of follow-up.

Histopathologic examination of the excision specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, massive capillary proliferation, and viral cytopathic changes in keratinocytes characterized by ballooning degeneration and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which was consistent with the clinical diagnosis of an orf. Unfortunately, the lesion relapsed rapidly following excision (Figure, A). Treatment with oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily) and imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) was initiated. However, this treatment was unsuccessful and was discontinued after 6 weeks, as the lesion kept growing, reaching a diameter of approximately 5 cm and becoming lobulated on the surface (Figure, B). Combination therapy was started with imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) and intralesional interferon alfa-2a injections (3 million IU twice weekly). The injections were so painful that the patient refused further therapy after only 2 injections. The therapy was switched from intralesional to systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon alfa-2a (3 million IU twice weekly) with concomitant imiquimod cream 5% 3 times weekly. This treatment was well tolerated by our patient with no notable side effects, except for mild fever on the night of each injection. Three weeks after the commencement of systemic injections, remarkable healing of the lesions with reduced size and exudation was noted. The frequency of injections was decreased to once weekly, which was then discontinued after 6 weeks when the lesion totally resolved (Figure, C). At 12 months’ follow-up, there were no signs of relapse.

Comment

Orf is an occupational disease that usually develops in farmers, butchers, and veterinarians; however, epidemic outbreaks of human orf are commonly observed in Turkey after the feast of sacrifice, as many individuals have close contact with the animals during sacrification.2 In Turkey, orf is well recognized by dermatologists, and clinical diagnosis usually is not difficult.

Human orf has a self-limited course in which lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, such as our patient with CLL, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant, requiring early and effective treatment. Treatment options for giant orf tumors in immunocompromised individuals include surgical excision,3 cryotherapy, topical imiquimod,4,5 topical or intralesional cidofovir,6 and intralesional interferon alfa injections.7 According to our clinical observations, surgical interventions for treatment of orfs usually cause a delay in the natural healing process; however, because surgical excision is a recommended treatment option for exophytic and recalcitrant orfs, we decided to treat our patient with surgical excision, which resulted in rapid recurrence and massive proliferation. A similar case of giant orf that was aggravated after surgery has been reported.8 In light of these cases, it is our opinion that treatment options other than surgery may be reasonable.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia may show features of both humoral and cell-mediated deficiency. Patients are known to be prone to viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and human papillomavirus. A giant orf infection on the background of CLL also has been described.9

Interferons were first discovered in 1957 and named after their ability to interfere with viral replication. They represent a family of cytokines that has an essential role in the innate immune response to virus infections. Because of their antiviral properties, recombinant forms of interferon alfa are widely used with success in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. A few other antiviral clinical applications of interferon alfa include infections caused by human herpesvirus 8 (the etiological agent in Kaposi sarcoma) and human papillomatosis virus (the etiological agent in juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis and condyloma acuminatum).10

In a report by Ran et al,7 intralesional interferon alfa injections were successfully used for treatment of giant orf lesions in an immunocompromised patient. As a result, we started treating the patient with intralesional interferon alfa-2a, but it was not well tolerated by our patient, as it was quite painful. We then decided to continue the therapy with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections, as we believed that it was a good option due to its antiviral, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic properties. With the experimental combined therapy of systemic interferon alfa-2a and topical imiquimod, our patient achieved a complete response in 9 weeks (3 weeks of twice weekly injections and then 6 weeks of once weekly injections) and had no relapses during 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of a giant orf treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections. Because intralesional injections are quite painful, systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon might be a good and safe alternative for recalcitrant orf lesions in immunocompromised patients. However, more studies and reports are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

Orf, also known as ecthyma contagiosum, is a common viral zoonotic infection caused by a parapoxvirus. It is widespread among small ruminants such as sheep and goats, and it can be transmitted to humans by close contact with infected animals or contaminated fomites. It usually manifests as vesiculoulcerative lesions or nodules on the inoculation sites, mostly on the hands, but other sites such as the head and scalp occasionally may be involved.1 We report the case of an orf that proliferated dramatically and became giant after total excision. It was successfully treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections and imiquimod cream.

Case Report

A 68-year-old man presented with a rapidly enlarging mass on the left hand that developed 4 weeks prior after close contact with a freshly slaughtered sheep during an Islamic holiday in Turkey. His medical history was remarkable for chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), which was diagnosed one year prior. The patient had been treated with systemic prednisolone and cyclophosphamide therapies, but his disease was in remission at the current presentation and he currently was not receiving any treatment. On physical examination, a 2-cm, exophytic, pinkish gray, weeping nodule was observed on the proximal aspect of the right thumb. Based on the clinical findings and typical anamnesis, a diagnosis of an orf was concluded. It was decided to monitor the patient without any intervention; however, because the lesion did not resolve and remained stable, he was referred to a plastic surgeon for surgical removal after 6 weeks of follow-up.

Histopathologic examination of the excision specimen revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, massive capillary proliferation, and viral cytopathic changes in keratinocytes characterized by ballooning degeneration and eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions, which was consistent with the clinical diagnosis of an orf. Unfortunately, the lesion relapsed rapidly following excision (Figure, A). Treatment with oral valacyclovir (1 g 3 times daily) and imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) was initiated. However, this treatment was unsuccessful and was discontinued after 6 weeks, as the lesion kept growing, reaching a diameter of approximately 5 cm and becoming lobulated on the surface (Figure, B). Combination therapy was started with imiquimod cream 5% (3 times weekly) and intralesional interferon alfa-2a injections (3 million IU twice weekly). The injections were so painful that the patient refused further therapy after only 2 injections. The therapy was switched from intralesional to systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon alfa-2a (3 million IU twice weekly) with concomitant imiquimod cream 5% 3 times weekly. This treatment was well tolerated by our patient with no notable side effects, except for mild fever on the night of each injection. Three weeks after the commencement of systemic injections, remarkable healing of the lesions with reduced size and exudation was noted. The frequency of injections was decreased to once weekly, which was then discontinued after 6 weeks when the lesion totally resolved (Figure, C). At 12 months’ follow-up, there were no signs of relapse.

Comment

Orf is an occupational disease that usually develops in farmers, butchers, and veterinarians; however, epidemic outbreaks of human orf are commonly observed in Turkey after the feast of sacrifice, as many individuals have close contact with the animals during sacrification.2 In Turkey, orf is well recognized by dermatologists, and clinical diagnosis usually is not difficult.

Human orf has a self-limited course in which lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, such as our patient with CLL, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant, requiring early and effective treatment. Treatment options for giant orf tumors in immunocompromised individuals include surgical excision,3 cryotherapy, topical imiquimod,4,5 topical or intralesional cidofovir,6 and intralesional interferon alfa injections.7 According to our clinical observations, surgical interventions for treatment of orfs usually cause a delay in the natural healing process; however, because surgical excision is a recommended treatment option for exophytic and recalcitrant orfs, we decided to treat our patient with surgical excision, which resulted in rapid recurrence and massive proliferation. A similar case of giant orf that was aggravated after surgery has been reported.8 In light of these cases, it is our opinion that treatment options other than surgery may be reasonable.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia may show features of both humoral and cell-mediated deficiency. Patients are known to be prone to viral infections such as varicella-zoster virus, herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and human papillomavirus. A giant orf infection on the background of CLL also has been described.9

Interferons were first discovered in 1957 and named after their ability to interfere with viral replication. They represent a family of cytokines that has an essential role in the innate immune response to virus infections. Because of their antiviral properties, recombinant forms of interferon alfa are widely used with success in the treatment of chronic hepatitis B and hepatitis C virus infections. A few other antiviral clinical applications of interferon alfa include infections caused by human herpesvirus 8 (the etiological agent in Kaposi sarcoma) and human papillomatosis virus (the etiological agent in juvenile laryngeal papillomatosis and condyloma acuminatum).10

In a report by Ran et al,7 intralesional interferon alfa injections were successfully used for treatment of giant orf lesions in an immunocompromised patient. As a result, we started treating the patient with intralesional interferon alfa-2a, but it was not well tolerated by our patient, as it was quite painful. We then decided to continue the therapy with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections, as we believed that it was a good option due to its antiviral, antiproliferative, and antiangiogenic properties. With the experimental combined therapy of systemic interferon alfa-2a and topical imiquimod, our patient achieved a complete response in 9 weeks (3 weeks of twice weekly injections and then 6 weeks of once weekly injections) and had no relapses during 12 months of follow-up.

Conclusion

We present a rare case of a giant orf treated with systemic interferon alfa-2a injections. Because intralesional injections are quite painful, systemic subcutaneous injections of interferon might be a good and safe alternative for recalcitrant orf lesions in immunocompromised patients. However, more studies and reports are needed to confirm its effectiveness and safety.

The 9th Cosmetic Surgery Forum will be held November 29-December 2, 2017, in Las Vegas, Nevada. Get more information at www.cosmeticsurgeryforum.com.

- Gurel MS, Ozardali I, Bitiren M, et al. Giant orf on the nose. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:183-185.

- Uzel M, Sasmaz S, Bakaris S, et al. A viral infection of the hand commonly seen after the feast of sacrifice: human orf (orf of the hand). Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:653-657.

- Ballanger F, Barbarot S, Mollat C, et al. Two giant orf lesions in a heart/lung transplant patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:284-286.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Lederman ER, Green GM, DeGroot HE, et al. Progressive ORF virus infection in a patient with lymphoma: successful treatment using imiquimod. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e100-e103.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma–like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Key SJ, Catania J, Mustafa SF, et al. Unusual presentation of human giant orf (ecthyma contagiosum). J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1076-1078.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Friedman RM. Clinical uses of interferons. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:158-162.

- Gurel MS, Ozardali I, Bitiren M, et al. Giant orf on the nose. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:183-185.

- Uzel M, Sasmaz S, Bakaris S, et al. A viral infection of the hand commonly seen after the feast of sacrifice: human orf (orf of the hand). Epidemiol Infect. 2005;133:653-657.

- Ballanger F, Barbarot S, Mollat C, et al. Two giant orf lesions in a heart/lung transplant patient. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:284-286.

- Zaharia D, Kanitakis J, Pouteil-Noble C, et al. Rapidly growing orf in a renal transplant recipient: favourable outcome with reduction of immunosuppression and imiquimod. Transpl Int. 2010;23:E62-E64.

- Lederman ER, Green GM, DeGroot HE, et al. Progressive ORF virus infection in a patient with lymphoma: successful treatment using imiquimod. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:e100-e103.

- Geerinck K, Lukito G, Snoeck R, et al. A case of human orf in an immunocompromised patient treated successfully with cidofovir cream. J Med Virol. 2001;64:543-549.

- Ran M, Lee M, Gong J, et al. Oral acyclovir and intralesional interferon injections for treatment of giant pyogenic granuloma–like lesions in an immunocompromised patient with human orf. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:1032-1034.

- Key SJ, Catania J, Mustafa SF, et al. Unusual presentation of human giant orf (ecthyma contagiosum). J Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:1076-1078.

- Hunskaar S. Giant orf in a patient with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Dermatol. 1986;114:631-634.

- Friedman RM. Clinical uses of interferons. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2008;65:158-162.

Resident Pearl

- Human orf lesions spontaneously resolve in 4 to 8 weeks; however, in immunocompromised patients, orf lesions may be persistent, atypical, and giant. We observed that surgical interventions for treatment of orfs cause a delay in the natural healing process, and other treatment options such as subcutaneous interferon alfa-2a may be used.