User login

A Computer-Assisted Process to Reduce Discharge of Emergency Department Patients with Abnormal Vital Signs

From Case Western Reserve University, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a computer-assisted process for reducing the number of patients discharged from the emergency department with abnormal vital signs.

- Methods: We devised a best practice alert in the Epic electronic medical record that triggers when the clinician attempts to print an after visit summary (discharge paperwork) at the time of discharge from the emergency department.

- Results: We saw no change in the percentage of patients discharged with elevated blood pressures, consistent with national recommendations. Removing that category of patients, we saw a decrease in the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs, primarily driven by a decrease in the percentage of patients discharged with tachycardia.

- Conclusion: A computer-assisted process can reduce the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs. Since based on national recommendations ED physicians do not address most elevated blood pressures in the ED, hypertension should not trigger an alert.

Abnormal vital signs in the emergency department (ED) have been associated with adverse outcomes [1,2]. While most patients discharged from the ED do well, some studies have found that the death rate within days to weeks post–ED discharge may be as high as 200 per 100,000 visits, although other studies have found a much lower rate [1]. A study by Sklar et al, although not specifically focused on vital signs at discharge, found that unexpected death within 7 days of ED discharge occurred at a rate of 30 per 100,000 patients. Abnormal vital signs, most commonly tachycardia, were present in 83% of cases [2].

In busy EDs, the combination of patient volume, frequent interruptions, and the intensity of tasks can result in deficiencies in vital sign monitoring [3–5] as well as abnormal vital signs not being recognized by the clinician at the time of patient discharge [6]. The importance of addressing this quality problem has been recognized. Prior efforts to address the problem have included nurses using manual methods to alert the physician to the presence of abnormal vital signs at the time of discharge [7]. Recommendations have been made to use electronic medical record (EMR) functions for prospectively addressing the problem of ED discharge with abnormal vital signs [8]. The utility of the EMR to identify potentially septic patients earlier and reduce mortality from sepsis via an algorithm that incorporated vital signs and other clinical crieria has been demonstrated [9,10]. In addition, automated vital signs advisories have been associated with increased survival on general hospital wards [11].

An adverse event that occurred at our institution prompted us to review this issue for our ED. We designed an EMR-assisted intervention to reduce the rate of patients discharged from the ED with abnormal vital signs.

Methods

Setting

Our ED is a busy, urban, Level 1 trauma center within a teaching facility. It sees over 100,000 patients per year and is segmented into resuscitation, high acuity, moderate acuity, and fast tract areas, in addition to the observation unit. Our organization uses the Epic (Madison, Wisconsin) electronic health record, which we have been using for over a decade.

Discharge Instructions—Old Process

In our ED, providers, attending physicians, residents and advance practice nurses enter and print their own discharge instructions, which are given to nursing staff to review with patients. Prior to the project, nurses were expected to notify a physician if they thought a vital sign was abnormal. Each nurse made independent decisions on what constituted a vital sign abnormality based on the patient’s condition and could communicate that to the provider at their discretion prior to discharge. This process created inconsistencies in care.

Development of Alert

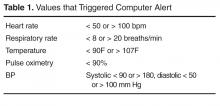

We created an alert that appears within the provider workflow at the time the provider attempts to print discharge instructions. Based on literature review and operational leadership consensus, we set the parameters for abnormal vital signs (Table 1). We chose parameters to identify abnormalities important to

The alert displays when a user attempts to print discharge instructions on a patient whose last recorded vital signs are not all normal. The display informs that there are abnormal vital signs (Figure). Upon display of the alert, the user can click on the message, which would take them to the vital sign entry activity in the EMR, or they can proceed with printing by clicking the print button (not visible in the Figure). The alert is not a forcing function; the user can proceed with printing the discharge instructions without addressing the abnormality that triggered the alert.

Pre-Post Evaluation

We would have liked to have determined how often the abnormal vital signs alert triggered, how it was responded to, and whether the patient was subsequently discharged with normal vital signs; however, our system does not record these events. Instead, we used the system to compare the percentage of adult patients who were discharged with abnormal vital signs for 2 time periods: the period prior to our December 2014 implementation (1 Oct to 1 Dec 2014) and the post implementation period (15 Dec 2014 to 15 Feb 2015). Our presumption was that the use of the alert system would reduce the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs, including an abnormal pulse oximetry.

To conduct our analysis, we identified adult patients seen during the 2 time periods. We eliminated those patients who died, left without being seen, eloped, were admitted or were transferred to other institutions. This resulted in 3664 patients, with 2179 in the pre-implementation group and 1485 in the post-implementation group. The higher volume in the pre group reflects the early occurrence of influenza season in our area during the study period, along with our generally busier time in late fall compared to winter.

The analysis was performed as a likelihood ratio chi-square analysis using SAS (Cary, NC) software.

Results

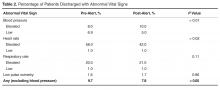

The analysis demonstrated that physicians were, by and large, following recommendations consistent with policies of the American College of Emergency Physicians regarding the management of elevated blood pressures, which do not mandate that patients with asymptomatic elevations of blood pressure receive medical intervention in the ED [12]. In our analysis, the percentage of patients discharged with elevated blood pressures actually increased from 7.5% to 9.9% following the intervention. Importantly, however, the percentage of patients discharged with low blood pressures decreased from 6.9% to 5.0% (P < 0.01).Tthe percent of patients discharged with an elevated heart rate, decreased from 58% in the pre alert group to 42% in the post alert group (P < 0.02).

Discussion

In our study, we used features of the EMR prospectively to affect discharge and then used the database functions of the EMR to assess the effectiveness of those efforts. Previous studies that have looked at the incidence of abnormal vital signs at discharge have been manual, retrospective reviews of records. We are not aware of any studies reporting the results of introducing an EMR alert to prospectively identify patients with abnormal vital signs prior to discharge

While we found that this intervention was successful in reducing clinically relevant abnormal vital signs at discharge, we have realized that the elevated blood pressure alert was unnecessary and we have eliminated it from the programming. We will revisit our strategy to determine if further reducing the high blood pressure alerts can lead to greater improvements in reducing the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs.

Future plans include a review of the re-visit or hospitalization rate for patients discharged with abnormal vital signs. A companion study evaluating a similar approach to the care of children is under consideration. We are also considering including a field in the EMR for the clinician to document why they discharged a patient with abnormal vital signs.

Corresponding author: Jonathan E. Siff, MD 2500 MetroHealth Drive BG3-65 Cleveland, Ohio 44109 jsiff@metrohealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Gunnarsdottir OS, Rafnsson V. Death within 8 days after discharge to home from the emergency department. Eur J of Public Health 2008;18:522–6.

2. Sklar DP, Crandall CS, Loeliger E, et al. Unanticipated death after discharge home from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2007;49:735–45.

3. Johnson KD, Winkelman C, Burant CJ, et al. The factors that affect the frequency of vital sign monitoring in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2014;40:27–35.

4. Gravel J, Opatrny L, Gouin S. High rate of missing vital signs data at triage in a paediatric emergency department. Paediatr Child Health 2006;11:211–5.

5. Depinet HE, Iyer SB, Hornung R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on reassessment of children with critically abnormal vital signs. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:1116–20.

6. Hafner JW, Parrish SE, Hubler JR, et al. Repeat assessment of abnormal vital signs and patient re-examination in us emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48(4 Suppl):S66.

7. Domagala SE. Discharge vital signs: an enhancement to ED quality and patient outcomes. J Emerg Nursing 2009;35:138–40.

8. Welch S. Red flags: abnormal vital signs at discharge.Emerg Med News 2011:33;7–8.

9. Nguyen SQ, Mwakalindile E, Booth JS, et al. Automated electronic medical record sepsis detection in the emergency department. PeerJ 2014;2:e343.

10. Narayanan N, Gross AK, Pintens M, et al. Effect of an electronic medical record alert for severe sepsis among ED patients. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:185–8.

11. Bellomo R, Ackerman M, Bailey M, et al. A controlled trial of electronic automated advisory vital signs monitoring in general hospital wards. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2349–61.

12. Wolf SJ, Lo B, Smith MD, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients in the emergency department with asymptomatic elevated blood pressure. Ann Emerg Med 2013:62;59–68.

From Case Western Reserve University, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a computer-assisted process for reducing the number of patients discharged from the emergency department with abnormal vital signs.

- Methods: We devised a best practice alert in the Epic electronic medical record that triggers when the clinician attempts to print an after visit summary (discharge paperwork) at the time of discharge from the emergency department.

- Results: We saw no change in the percentage of patients discharged with elevated blood pressures, consistent with national recommendations. Removing that category of patients, we saw a decrease in the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs, primarily driven by a decrease in the percentage of patients discharged with tachycardia.

- Conclusion: A computer-assisted process can reduce the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs. Since based on national recommendations ED physicians do not address most elevated blood pressures in the ED, hypertension should not trigger an alert.

Abnormal vital signs in the emergency department (ED) have been associated with adverse outcomes [1,2]. While most patients discharged from the ED do well, some studies have found that the death rate within days to weeks post–ED discharge may be as high as 200 per 100,000 visits, although other studies have found a much lower rate [1]. A study by Sklar et al, although not specifically focused on vital signs at discharge, found that unexpected death within 7 days of ED discharge occurred at a rate of 30 per 100,000 patients. Abnormal vital signs, most commonly tachycardia, were present in 83% of cases [2].

In busy EDs, the combination of patient volume, frequent interruptions, and the intensity of tasks can result in deficiencies in vital sign monitoring [3–5] as well as abnormal vital signs not being recognized by the clinician at the time of patient discharge [6]. The importance of addressing this quality problem has been recognized. Prior efforts to address the problem have included nurses using manual methods to alert the physician to the presence of abnormal vital signs at the time of discharge [7]. Recommendations have been made to use electronic medical record (EMR) functions for prospectively addressing the problem of ED discharge with abnormal vital signs [8]. The utility of the EMR to identify potentially septic patients earlier and reduce mortality from sepsis via an algorithm that incorporated vital signs and other clinical crieria has been demonstrated [9,10]. In addition, automated vital signs advisories have been associated with increased survival on general hospital wards [11].

An adverse event that occurred at our institution prompted us to review this issue for our ED. We designed an EMR-assisted intervention to reduce the rate of patients discharged from the ED with abnormal vital signs.

Methods

Setting

Our ED is a busy, urban, Level 1 trauma center within a teaching facility. It sees over 100,000 patients per year and is segmented into resuscitation, high acuity, moderate acuity, and fast tract areas, in addition to the observation unit. Our organization uses the Epic (Madison, Wisconsin) electronic health record, which we have been using for over a decade.

Discharge Instructions—Old Process

In our ED, providers, attending physicians, residents and advance practice nurses enter and print their own discharge instructions, which are given to nursing staff to review with patients. Prior to the project, nurses were expected to notify a physician if they thought a vital sign was abnormal. Each nurse made independent decisions on what constituted a vital sign abnormality based on the patient’s condition and could communicate that to the provider at their discretion prior to discharge. This process created inconsistencies in care.

Development of Alert

We created an alert that appears within the provider workflow at the time the provider attempts to print discharge instructions. Based on literature review and operational leadership consensus, we set the parameters for abnormal vital signs (Table 1). We chose parameters to identify abnormalities important to

The alert displays when a user attempts to print discharge instructions on a patient whose last recorded vital signs are not all normal. The display informs that there are abnormal vital signs (Figure). Upon display of the alert, the user can click on the message, which would take them to the vital sign entry activity in the EMR, or they can proceed with printing by clicking the print button (not visible in the Figure). The alert is not a forcing function; the user can proceed with printing the discharge instructions without addressing the abnormality that triggered the alert.

Pre-Post Evaluation

We would have liked to have determined how often the abnormal vital signs alert triggered, how it was responded to, and whether the patient was subsequently discharged with normal vital signs; however, our system does not record these events. Instead, we used the system to compare the percentage of adult patients who were discharged with abnormal vital signs for 2 time periods: the period prior to our December 2014 implementation (1 Oct to 1 Dec 2014) and the post implementation period (15 Dec 2014 to 15 Feb 2015). Our presumption was that the use of the alert system would reduce the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs, including an abnormal pulse oximetry.

To conduct our analysis, we identified adult patients seen during the 2 time periods. We eliminated those patients who died, left without being seen, eloped, were admitted or were transferred to other institutions. This resulted in 3664 patients, with 2179 in the pre-implementation group and 1485 in the post-implementation group. The higher volume in the pre group reflects the early occurrence of influenza season in our area during the study period, along with our generally busier time in late fall compared to winter.

The analysis was performed as a likelihood ratio chi-square analysis using SAS (Cary, NC) software.

Results

The analysis demonstrated that physicians were, by and large, following recommendations consistent with policies of the American College of Emergency Physicians regarding the management of elevated blood pressures, which do not mandate that patients with asymptomatic elevations of blood pressure receive medical intervention in the ED [12]. In our analysis, the percentage of patients discharged with elevated blood pressures actually increased from 7.5% to 9.9% following the intervention. Importantly, however, the percentage of patients discharged with low blood pressures decreased from 6.9% to 5.0% (P < 0.01).Tthe percent of patients discharged with an elevated heart rate, decreased from 58% in the pre alert group to 42% in the post alert group (P < 0.02).

Discussion

In our study, we used features of the EMR prospectively to affect discharge and then used the database functions of the EMR to assess the effectiveness of those efforts. Previous studies that have looked at the incidence of abnormal vital signs at discharge have been manual, retrospective reviews of records. We are not aware of any studies reporting the results of introducing an EMR alert to prospectively identify patients with abnormal vital signs prior to discharge

While we found that this intervention was successful in reducing clinically relevant abnormal vital signs at discharge, we have realized that the elevated blood pressure alert was unnecessary and we have eliminated it from the programming. We will revisit our strategy to determine if further reducing the high blood pressure alerts can lead to greater improvements in reducing the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs.

Future plans include a review of the re-visit or hospitalization rate for patients discharged with abnormal vital signs. A companion study evaluating a similar approach to the care of children is under consideration. We are also considering including a field in the EMR for the clinician to document why they discharged a patient with abnormal vital signs.

Corresponding author: Jonathan E. Siff, MD 2500 MetroHealth Drive BG3-65 Cleveland, Ohio 44109 jsiff@metrohealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From Case Western Reserve University, MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe a computer-assisted process for reducing the number of patients discharged from the emergency department with abnormal vital signs.

- Methods: We devised a best practice alert in the Epic electronic medical record that triggers when the clinician attempts to print an after visit summary (discharge paperwork) at the time of discharge from the emergency department.

- Results: We saw no change in the percentage of patients discharged with elevated blood pressures, consistent with national recommendations. Removing that category of patients, we saw a decrease in the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs, primarily driven by a decrease in the percentage of patients discharged with tachycardia.

- Conclusion: A computer-assisted process can reduce the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs. Since based on national recommendations ED physicians do not address most elevated blood pressures in the ED, hypertension should not trigger an alert.

Abnormal vital signs in the emergency department (ED) have been associated with adverse outcomes [1,2]. While most patients discharged from the ED do well, some studies have found that the death rate within days to weeks post–ED discharge may be as high as 200 per 100,000 visits, although other studies have found a much lower rate [1]. A study by Sklar et al, although not specifically focused on vital signs at discharge, found that unexpected death within 7 days of ED discharge occurred at a rate of 30 per 100,000 patients. Abnormal vital signs, most commonly tachycardia, were present in 83% of cases [2].

In busy EDs, the combination of patient volume, frequent interruptions, and the intensity of tasks can result in deficiencies in vital sign monitoring [3–5] as well as abnormal vital signs not being recognized by the clinician at the time of patient discharge [6]. The importance of addressing this quality problem has been recognized. Prior efforts to address the problem have included nurses using manual methods to alert the physician to the presence of abnormal vital signs at the time of discharge [7]. Recommendations have been made to use electronic medical record (EMR) functions for prospectively addressing the problem of ED discharge with abnormal vital signs [8]. The utility of the EMR to identify potentially septic patients earlier and reduce mortality from sepsis via an algorithm that incorporated vital signs and other clinical crieria has been demonstrated [9,10]. In addition, automated vital signs advisories have been associated with increased survival on general hospital wards [11].

An adverse event that occurred at our institution prompted us to review this issue for our ED. We designed an EMR-assisted intervention to reduce the rate of patients discharged from the ED with abnormal vital signs.

Methods

Setting

Our ED is a busy, urban, Level 1 trauma center within a teaching facility. It sees over 100,000 patients per year and is segmented into resuscitation, high acuity, moderate acuity, and fast tract areas, in addition to the observation unit. Our organization uses the Epic (Madison, Wisconsin) electronic health record, which we have been using for over a decade.

Discharge Instructions—Old Process

In our ED, providers, attending physicians, residents and advance practice nurses enter and print their own discharge instructions, which are given to nursing staff to review with patients. Prior to the project, nurses were expected to notify a physician if they thought a vital sign was abnormal. Each nurse made independent decisions on what constituted a vital sign abnormality based on the patient’s condition and could communicate that to the provider at their discretion prior to discharge. This process created inconsistencies in care.

Development of Alert

We created an alert that appears within the provider workflow at the time the provider attempts to print discharge instructions. Based on literature review and operational leadership consensus, we set the parameters for abnormal vital signs (Table 1). We chose parameters to identify abnormalities important to

The alert displays when a user attempts to print discharge instructions on a patient whose last recorded vital signs are not all normal. The display informs that there are abnormal vital signs (Figure). Upon display of the alert, the user can click on the message, which would take them to the vital sign entry activity in the EMR, or they can proceed with printing by clicking the print button (not visible in the Figure). The alert is not a forcing function; the user can proceed with printing the discharge instructions without addressing the abnormality that triggered the alert.

Pre-Post Evaluation

We would have liked to have determined how often the abnormal vital signs alert triggered, how it was responded to, and whether the patient was subsequently discharged with normal vital signs; however, our system does not record these events. Instead, we used the system to compare the percentage of adult patients who were discharged with abnormal vital signs for 2 time periods: the period prior to our December 2014 implementation (1 Oct to 1 Dec 2014) and the post implementation period (15 Dec 2014 to 15 Feb 2015). Our presumption was that the use of the alert system would reduce the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs, including an abnormal pulse oximetry.

To conduct our analysis, we identified adult patients seen during the 2 time periods. We eliminated those patients who died, left without being seen, eloped, were admitted or were transferred to other institutions. This resulted in 3664 patients, with 2179 in the pre-implementation group and 1485 in the post-implementation group. The higher volume in the pre group reflects the early occurrence of influenza season in our area during the study period, along with our generally busier time in late fall compared to winter.

The analysis was performed as a likelihood ratio chi-square analysis using SAS (Cary, NC) software.

Results

The analysis demonstrated that physicians were, by and large, following recommendations consistent with policies of the American College of Emergency Physicians regarding the management of elevated blood pressures, which do not mandate that patients with asymptomatic elevations of blood pressure receive medical intervention in the ED [12]. In our analysis, the percentage of patients discharged with elevated blood pressures actually increased from 7.5% to 9.9% following the intervention. Importantly, however, the percentage of patients discharged with low blood pressures decreased from 6.9% to 5.0% (P < 0.01).Tthe percent of patients discharged with an elevated heart rate, decreased from 58% in the pre alert group to 42% in the post alert group (P < 0.02).

Discussion

In our study, we used features of the EMR prospectively to affect discharge and then used the database functions of the EMR to assess the effectiveness of those efforts. Previous studies that have looked at the incidence of abnormal vital signs at discharge have been manual, retrospective reviews of records. We are not aware of any studies reporting the results of introducing an EMR alert to prospectively identify patients with abnormal vital signs prior to discharge

While we found that this intervention was successful in reducing clinically relevant abnormal vital signs at discharge, we have realized that the elevated blood pressure alert was unnecessary and we have eliminated it from the programming. We will revisit our strategy to determine if further reducing the high blood pressure alerts can lead to greater improvements in reducing the percentage of patients discharged with abnormal vital signs.

Future plans include a review of the re-visit or hospitalization rate for patients discharged with abnormal vital signs. A companion study evaluating a similar approach to the care of children is under consideration. We are also considering including a field in the EMR for the clinician to document why they discharged a patient with abnormal vital signs.

Corresponding author: Jonathan E. Siff, MD 2500 MetroHealth Drive BG3-65 Cleveland, Ohio 44109 jsiff@metrohealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Gunnarsdottir OS, Rafnsson V. Death within 8 days after discharge to home from the emergency department. Eur J of Public Health 2008;18:522–6.

2. Sklar DP, Crandall CS, Loeliger E, et al. Unanticipated death after discharge home from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2007;49:735–45.

3. Johnson KD, Winkelman C, Burant CJ, et al. The factors that affect the frequency of vital sign monitoring in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2014;40:27–35.

4. Gravel J, Opatrny L, Gouin S. High rate of missing vital signs data at triage in a paediatric emergency department. Paediatr Child Health 2006;11:211–5.

5. Depinet HE, Iyer SB, Hornung R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on reassessment of children with critically abnormal vital signs. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:1116–20.

6. Hafner JW, Parrish SE, Hubler JR, et al. Repeat assessment of abnormal vital signs and patient re-examination in us emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48(4 Suppl):S66.

7. Domagala SE. Discharge vital signs: an enhancement to ED quality and patient outcomes. J Emerg Nursing 2009;35:138–40.

8. Welch S. Red flags: abnormal vital signs at discharge.Emerg Med News 2011:33;7–8.

9. Nguyen SQ, Mwakalindile E, Booth JS, et al. Automated electronic medical record sepsis detection in the emergency department. PeerJ 2014;2:e343.

10. Narayanan N, Gross AK, Pintens M, et al. Effect of an electronic medical record alert for severe sepsis among ED patients. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:185–8.

11. Bellomo R, Ackerman M, Bailey M, et al. A controlled trial of electronic automated advisory vital signs monitoring in general hospital wards. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2349–61.

12. Wolf SJ, Lo B, Smith MD, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients in the emergency department with asymptomatic elevated blood pressure. Ann Emerg Med 2013:62;59–68.

1. Gunnarsdottir OS, Rafnsson V. Death within 8 days after discharge to home from the emergency department. Eur J of Public Health 2008;18:522–6.

2. Sklar DP, Crandall CS, Loeliger E, et al. Unanticipated death after discharge home from the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2007;49:735–45.

3. Johnson KD, Winkelman C, Burant CJ, et al. The factors that affect the frequency of vital sign monitoring in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs 2014;40:27–35.

4. Gravel J, Opatrny L, Gouin S. High rate of missing vital signs data at triage in a paediatric emergency department. Paediatr Child Health 2006;11:211–5.

5. Depinet HE, Iyer SB, Hornung R, et al. The effect of emergency department crowding on reassessment of children with critically abnormal vital signs. Acad Emerg Med 2014;21:1116–20.

6. Hafner JW, Parrish SE, Hubler JR, et al. Repeat assessment of abnormal vital signs and patient re-examination in us emergency department patients. Ann Emerg Med 2006;48(4 Suppl):S66.

7. Domagala SE. Discharge vital signs: an enhancement to ED quality and patient outcomes. J Emerg Nursing 2009;35:138–40.

8. Welch S. Red flags: abnormal vital signs at discharge.Emerg Med News 2011:33;7–8.

9. Nguyen SQ, Mwakalindile E, Booth JS, et al. Automated electronic medical record sepsis detection in the emergency department. PeerJ 2014;2:e343.

10. Narayanan N, Gross AK, Pintens M, et al. Effect of an electronic medical record alert for severe sepsis among ED patients. Am J Emerg Med 2016;34:185–8.

11. Bellomo R, Ackerman M, Bailey M, et al. A controlled trial of electronic automated advisory vital signs monitoring in general hospital wards. Crit Care Med 2012;40:2349–61.

12. Wolf SJ, Lo B, Smith MD, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the evaluation and management of adult patients in the emergency department with asymptomatic elevated blood pressure. Ann Emerg Med 2013:62;59–68.

The Daily Safety Brief in a Safety Net Hospital: Development and Outcomes

From the MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the process for the creation and development of the Daily Safety Brief (DSB) in our safety net hospital.

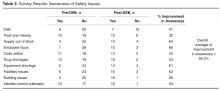

- Methods: We developed the DSB, a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. The average call length with 25 departments reporting is just 9.5 minutes.

- Results: Survey results reveal an overall average improvement in awareness among DSB participants about hospital safety issues. Average days to issue resolution is currently 2.3 days, with open issues tracked and reported on daily.

- Conclusion: The DSB has improved real-time communication and awareness about safety issues in our organization.

As health care organizations strive to ensure a culture of safety for patients and staff, they must also be able to demonstrate reliability in that culture. The concept of highly reliable organizations originated in aviation and military fields due to the high-stakes environment and need for rapid and effective communication across departments. High reliability in health care organizations is described by the Joint Commission as consistent excellence in quality and safety for every patient, every time [1].

Highly reliable organizations put systems in place that makes them resilient with methods that lead to consistent accomplishment of goals and strategies to avoid potentially catastrophic errors [2]. An integral component to success in all high reliability organizations is a method of “Plan-of-the-Day” meetings to keep staff apprised of critical updates throughout the health system impacting care delivery [3]. Leaders at MetroHealth Medical Center believed that a daily safety briefing would help support the hospital’s journey to high reliability. We developed the Daily Safety Brief (DSB), a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis [4]. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. This article will describe the development and implementation of the DSB in our hospital.

Setting

MetroHealth Medical Center is an academic medical center in Cleveland, OH, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University. Metrohealth is a public safety net hospital with 731 licensed beds and a total of 1,160,773 patient visits in 2014, with 27,933 inpatient stays and 106,000 emergency department (ED) visits. The staff includes 507 physicians, 374 resident physicians, and 1222 nurses.

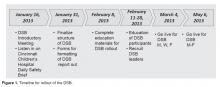

Program Development

As Metrohealth was contemplating the DSB, a group of senior leaders, including the chief medical officer, visited the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, which had a DSB process in place. Following that visit, a larger group of physicians and administrators from intake points, procedural areas, and ancillary departments were invited to listen in live to Cincinnati’s DSB. This turned out to be a pivotal step in gaining buy-in. The initial concerns from participants were that this would be another scheduled meeting in an already busy day. What we learned from listening in was that the DSB was conducted in a manner that was succinct and professional. Issues were identified without accusations or unrelated agendas. Following the call, participants discussed how impressed they were and clearly saw the value of the information that was shared. They began to brainstorm about what they could report that would be relevant to the audience.

It was determined that a leader and 2 facilitators would be assigned to each call. The role of the DSB leader is to trigger individual department report outs and to ensure follow-up on unresolved safety issues from the previous DSB. Leaders are recruited by senior leadership and need to be familiar with the effects that issues can have across the health care system. Leaders need to be able to ask pertinent questions, have the credibility to raise concerns, and have access to senior administration when they need to bypass usual administrative channels.

The role of the facilitators, who are all members of the Center for Quality, is to connect to the conference bridge line, to keep the DSB leader on task, and to record all departmental data and pertinent details of the DSB. The facilitators maintain the daily DSB document, which outlines the order in which departments are called to report and identifies for the leader any open items identified in the previous day’s DSB.

The Daily Safety Brief

Rollout

The DSB began 3 days per week on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 0830. The time was moved to 0800 since participants found the later time difficult as it fell in the middle of an hour, potentially conflicting with other meetings and preparation for the daily bed huddle. We recognized that many meetings began right at the start of the DSB. The CEO requested that all 0800 meetings begin with a call in to listen to the DSB. After 2 months, the frequency was increased to 5 days per week, Monday through Friday. The hospital trialed a weekend DSB, however, feedback from participants found this extremely difficult to attend due to leaner weekend staffing models and found that information shared was not impactful. In particular, items were identified on the weekend daily safety briefs but the staff needed to resolve those items were generally not available until Monday.

Refinements

Coaching occurred to help people be more succinct in sharing information that would impact other areas. Information that was relevant only internally to their department was streamlined. The participants were counseled to identify items that had potential impact on other departments or where other departments had resources that might improve operations.

After a year, participating departments requested the addition of the logistics and construction departments to the DSB. The addition of the logistics department offered the opportunity for clinical departments to communicate what equipment was needed to start the day and created the opportunity for logistics to close the feedback loop by giving an estimate on expected time of arrival of equipment. The addition of the construction department helped communicate issues that may impact the organization, and helps to coordinate care to minimally impact patients and operations.

Examples of Safety Improvements

The DSB keeps the departmental leadership aware of problems developing in all areas of the hospital. Upcoming safety risks are identified early so that plans can be put in place to ameliorate them. The expectation of the DSB leader is that a problem that isn’t readily solved during the DSB must be taken to senior administration for resolution. As an example, an issue involving delays in the purchase of a required neonatal ventilator was taken directly to the CEO by the DSB leader, resulting in completion of the purchase within days. Importantly, the requirement to report at the DSB leads to a preoccupation with risk and reporting and leads to transparency among interdependent departments.

Another issue effectively addressed by the DSB was when we received notification of a required mandatory power shutdown for an extended period of time. The local power company informed our facilities management department director that they discovered issues requiring urgent replacement of the transformer within 2 weeks. Facilities management reported this in the morning DSB. The DSB leader requested all stakeholders to stay on the call following completion of the DSB, and plans were set in motion to plan for the shutdown of power. The team agreed to conference call again at noon the same day to continue planning, and the affected building was prepared for the shutdown by the following day.

Another benefit of the DSB is illustrated by our inpatient psychiatry unit, which reports an acuity measure each day on a scale of 1 to 10. The MetroHealth Police Department utilizes the report to adjust their rounding schedule, with increased presence on days with high acuity, which has led to an improvement in morale among psychiatry unit staff.

Challenges and Solutions

Since these reports are available to a wide audience in the organization, it is important to assure the reporters that no repercussions will ensue from any information that they provide. Senior leadership was enlisted to communicate with their departments that no repercussions would occur from reporting. As an example, some managers reported to the DSB development team privately that their supervisors were concerned about reporting of staff shortages on the DSB. As the shortages had patient care implications and affected other clinical departments, the DSB development team met with the involved supervisors to address the need for open reporting. In fact, repeated reporting of shortages in one support department on the DSB resulted in that issue being taken to high levels of administration leading to an increase in their staffing levels.

Scheduling can be a challenge for DSB participants. Holding the DSB at 0800 has led some departments to delegate the reporting or information gathering. For the individual reporting departments, creating a reporting workflow was a challenge. The departments needed to ensure that their DSB report was ready to go by 0800. This timeline forced departments to improve their own interdepartmental communication structure. An unexpected benefit of this requirement is that some departments have created a morning huddle to share information, which has reportedly improved communication and morale. The ambulatory network created a separate shared database for clinics to post concerns meeting DSB reporting criteria. One designated staff member would access this collective information when preparing for the DSB report. While most departments have a senior manager providing their report, this is not a requirement. In many departments, that reporter varies from day to day, although consistently it is someone with some administrative or leadership role in the department.

Conference call technology presented the solution to the problem of acquiring a meeting space for a large group. The DSB is broadcast from one physical location, where the facilitators and leader convene. While this conference room is open to anyone who wants to attend in person, most departments choose to participate through the conference line. The DSB conference call is open to anyone in the organization to access. Typically 35 to 40 phones are accessing the line each DSB. Challenges included callers not muting their phones, creating distracting background noise, and callers placing their phones on hold, which prompted the hospital hold message to play continuously. Multiple repeated reminders via email and at the start of the DSB has rectified this issue for the most part, with occasional reminders made when the issue recurs.

Data Management

Initially, an Excel file was created with columns for each reporting department as well as each item they were asked to report on. This “running” file became cumbersome. Retrieving information on past issues was not automated. Therefore, we enlisted the help of a data analyst to create an Access database. When it was complete, this new database allowed us to save information by individual dates, query number of days to issue resolution, and create reports noting unresolved issues for the leader to reference. Many data points can be queried in the access database. Real-time reports are available at all times and updated with every data entry. The database is able to identify departments not on the daily call and trend information, ie, how many listeners were on the DSB, number of falls, forensic patients in house, number of patients awaiting admission from the ED, number of ambulatory visits scheduled each day, equipment needed, number of cardiac arrest calls, and number of neonatal resuscitations.

At the conclusion of the call, the DSB report is completed and posted to a shared website on the hospital intranet for the entire hospital to access and read. Feedback from participant indicated that they found it cumbersome to access this. The communications department was enlisted to enable easy access and staff can now access the DSB report from the front page of the hospital intranet.

Outcomes

Since initiation of our DSB, we have tracked the average number of minutes spent on each call. When calls began, the average time on the call was 12.4 minutes. With the evolution of the DSB and coaching managers in various departments, the average time on the call is now 9.5 minutes in 2015, despite additional reporting departments joining the DSB.

Summary

The DSB has become an important tool in creating and moving towards a culture of safety and high reliability within the MetroHealth System. Over time, processes have become organized and engrained in all departments. This format has allowed issues to be brought forward timely where immediate attention can be given to achieve resolution in a nonthreatening manner, improving transparency. The fluidity of the DSB allows it to be enhanced and modified as improvements and opportunities are identified in the organization. The DSB has provided opportunities to create situational awareness which allows a look forward to prevention and creates a proactive environment. The results of these efforts has made MetroHealth a safer place for patients, visitors, and employees.

Corresponding author: Anne M. Aulisio, MSN, aaulisio@metrohealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Available at www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org.

2. Gamble M. 5 traits of high reliability organizations: how to hardwire each in your organization. Becker’s Hospital Review 29 Apr 2013. Accessed at www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/5-traits-of-high-reliability-organizations-how-to-hardwire-each-in-your-organization.html.

3. Stockmeier C, Clapper C. Daily check-in for safety: from best practice to common practice. Patient Safety Qual Healthcare 2011:23. Accessed at psqh.com/daily-check-in-for-safety-from-best-practice-to-common-practice.

4. Creating situational awareness: a systems approach. In: Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events. Medical surge capacity: workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32859/.

5. TeamSTEPPS. Available at www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/index.html.

From the MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the process for the creation and development of the Daily Safety Brief (DSB) in our safety net hospital.

- Methods: We developed the DSB, a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. The average call length with 25 departments reporting is just 9.5 minutes.

- Results: Survey results reveal an overall average improvement in awareness among DSB participants about hospital safety issues. Average days to issue resolution is currently 2.3 days, with open issues tracked and reported on daily.

- Conclusion: The DSB has improved real-time communication and awareness about safety issues in our organization.

As health care organizations strive to ensure a culture of safety for patients and staff, they must also be able to demonstrate reliability in that culture. The concept of highly reliable organizations originated in aviation and military fields due to the high-stakes environment and need for rapid and effective communication across departments. High reliability in health care organizations is described by the Joint Commission as consistent excellence in quality and safety for every patient, every time [1].

Highly reliable organizations put systems in place that makes them resilient with methods that lead to consistent accomplishment of goals and strategies to avoid potentially catastrophic errors [2]. An integral component to success in all high reliability organizations is a method of “Plan-of-the-Day” meetings to keep staff apprised of critical updates throughout the health system impacting care delivery [3]. Leaders at MetroHealth Medical Center believed that a daily safety briefing would help support the hospital’s journey to high reliability. We developed the Daily Safety Brief (DSB), a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis [4]. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. This article will describe the development and implementation of the DSB in our hospital.

Setting

MetroHealth Medical Center is an academic medical center in Cleveland, OH, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University. Metrohealth is a public safety net hospital with 731 licensed beds and a total of 1,160,773 patient visits in 2014, with 27,933 inpatient stays and 106,000 emergency department (ED) visits. The staff includes 507 physicians, 374 resident physicians, and 1222 nurses.

Program Development

As Metrohealth was contemplating the DSB, a group of senior leaders, including the chief medical officer, visited the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, which had a DSB process in place. Following that visit, a larger group of physicians and administrators from intake points, procedural areas, and ancillary departments were invited to listen in live to Cincinnati’s DSB. This turned out to be a pivotal step in gaining buy-in. The initial concerns from participants were that this would be another scheduled meeting in an already busy day. What we learned from listening in was that the DSB was conducted in a manner that was succinct and professional. Issues were identified without accusations or unrelated agendas. Following the call, participants discussed how impressed they were and clearly saw the value of the information that was shared. They began to brainstorm about what they could report that would be relevant to the audience.

It was determined that a leader and 2 facilitators would be assigned to each call. The role of the DSB leader is to trigger individual department report outs and to ensure follow-up on unresolved safety issues from the previous DSB. Leaders are recruited by senior leadership and need to be familiar with the effects that issues can have across the health care system. Leaders need to be able to ask pertinent questions, have the credibility to raise concerns, and have access to senior administration when they need to bypass usual administrative channels.

The role of the facilitators, who are all members of the Center for Quality, is to connect to the conference bridge line, to keep the DSB leader on task, and to record all departmental data and pertinent details of the DSB. The facilitators maintain the daily DSB document, which outlines the order in which departments are called to report and identifies for the leader any open items identified in the previous day’s DSB.

The Daily Safety Brief

Rollout

The DSB began 3 days per week on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 0830. The time was moved to 0800 since participants found the later time difficult as it fell in the middle of an hour, potentially conflicting with other meetings and preparation for the daily bed huddle. We recognized that many meetings began right at the start of the DSB. The CEO requested that all 0800 meetings begin with a call in to listen to the DSB. After 2 months, the frequency was increased to 5 days per week, Monday through Friday. The hospital trialed a weekend DSB, however, feedback from participants found this extremely difficult to attend due to leaner weekend staffing models and found that information shared was not impactful. In particular, items were identified on the weekend daily safety briefs but the staff needed to resolve those items were generally not available until Monday.

Refinements

Coaching occurred to help people be more succinct in sharing information that would impact other areas. Information that was relevant only internally to their department was streamlined. The participants were counseled to identify items that had potential impact on other departments or where other departments had resources that might improve operations.

After a year, participating departments requested the addition of the logistics and construction departments to the DSB. The addition of the logistics department offered the opportunity for clinical departments to communicate what equipment was needed to start the day and created the opportunity for logistics to close the feedback loop by giving an estimate on expected time of arrival of equipment. The addition of the construction department helped communicate issues that may impact the organization, and helps to coordinate care to minimally impact patients and operations.

Examples of Safety Improvements

The DSB keeps the departmental leadership aware of problems developing in all areas of the hospital. Upcoming safety risks are identified early so that plans can be put in place to ameliorate them. The expectation of the DSB leader is that a problem that isn’t readily solved during the DSB must be taken to senior administration for resolution. As an example, an issue involving delays in the purchase of a required neonatal ventilator was taken directly to the CEO by the DSB leader, resulting in completion of the purchase within days. Importantly, the requirement to report at the DSB leads to a preoccupation with risk and reporting and leads to transparency among interdependent departments.

Another issue effectively addressed by the DSB was when we received notification of a required mandatory power shutdown for an extended period of time. The local power company informed our facilities management department director that they discovered issues requiring urgent replacement of the transformer within 2 weeks. Facilities management reported this in the morning DSB. The DSB leader requested all stakeholders to stay on the call following completion of the DSB, and plans were set in motion to plan for the shutdown of power. The team agreed to conference call again at noon the same day to continue planning, and the affected building was prepared for the shutdown by the following day.

Another benefit of the DSB is illustrated by our inpatient psychiatry unit, which reports an acuity measure each day on a scale of 1 to 10. The MetroHealth Police Department utilizes the report to adjust their rounding schedule, with increased presence on days with high acuity, which has led to an improvement in morale among psychiatry unit staff.

Challenges and Solutions

Since these reports are available to a wide audience in the organization, it is important to assure the reporters that no repercussions will ensue from any information that they provide. Senior leadership was enlisted to communicate with their departments that no repercussions would occur from reporting. As an example, some managers reported to the DSB development team privately that their supervisors were concerned about reporting of staff shortages on the DSB. As the shortages had patient care implications and affected other clinical departments, the DSB development team met with the involved supervisors to address the need for open reporting. In fact, repeated reporting of shortages in one support department on the DSB resulted in that issue being taken to high levels of administration leading to an increase in their staffing levels.

Scheduling can be a challenge for DSB participants. Holding the DSB at 0800 has led some departments to delegate the reporting or information gathering. For the individual reporting departments, creating a reporting workflow was a challenge. The departments needed to ensure that their DSB report was ready to go by 0800. This timeline forced departments to improve their own interdepartmental communication structure. An unexpected benefit of this requirement is that some departments have created a morning huddle to share information, which has reportedly improved communication and morale. The ambulatory network created a separate shared database for clinics to post concerns meeting DSB reporting criteria. One designated staff member would access this collective information when preparing for the DSB report. While most departments have a senior manager providing their report, this is not a requirement. In many departments, that reporter varies from day to day, although consistently it is someone with some administrative or leadership role in the department.

Conference call technology presented the solution to the problem of acquiring a meeting space for a large group. The DSB is broadcast from one physical location, where the facilitators and leader convene. While this conference room is open to anyone who wants to attend in person, most departments choose to participate through the conference line. The DSB conference call is open to anyone in the organization to access. Typically 35 to 40 phones are accessing the line each DSB. Challenges included callers not muting their phones, creating distracting background noise, and callers placing their phones on hold, which prompted the hospital hold message to play continuously. Multiple repeated reminders via email and at the start of the DSB has rectified this issue for the most part, with occasional reminders made when the issue recurs.

Data Management

Initially, an Excel file was created with columns for each reporting department as well as each item they were asked to report on. This “running” file became cumbersome. Retrieving information on past issues was not automated. Therefore, we enlisted the help of a data analyst to create an Access database. When it was complete, this new database allowed us to save information by individual dates, query number of days to issue resolution, and create reports noting unresolved issues for the leader to reference. Many data points can be queried in the access database. Real-time reports are available at all times and updated with every data entry. The database is able to identify departments not on the daily call and trend information, ie, how many listeners were on the DSB, number of falls, forensic patients in house, number of patients awaiting admission from the ED, number of ambulatory visits scheduled each day, equipment needed, number of cardiac arrest calls, and number of neonatal resuscitations.

At the conclusion of the call, the DSB report is completed and posted to a shared website on the hospital intranet for the entire hospital to access and read. Feedback from participant indicated that they found it cumbersome to access this. The communications department was enlisted to enable easy access and staff can now access the DSB report from the front page of the hospital intranet.

Outcomes

Since initiation of our DSB, we have tracked the average number of minutes spent on each call. When calls began, the average time on the call was 12.4 minutes. With the evolution of the DSB and coaching managers in various departments, the average time on the call is now 9.5 minutes in 2015, despite additional reporting departments joining the DSB.

Summary

The DSB has become an important tool in creating and moving towards a culture of safety and high reliability within the MetroHealth System. Over time, processes have become organized and engrained in all departments. This format has allowed issues to be brought forward timely where immediate attention can be given to achieve resolution in a nonthreatening manner, improving transparency. The fluidity of the DSB allows it to be enhanced and modified as improvements and opportunities are identified in the organization. The DSB has provided opportunities to create situational awareness which allows a look forward to prevention and creates a proactive environment. The results of these efforts has made MetroHealth a safer place for patients, visitors, and employees.

Corresponding author: Anne M. Aulisio, MSN, aaulisio@metrohealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH.

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the process for the creation and development of the Daily Safety Brief (DSB) in our safety net hospital.

- Methods: We developed the DSB, a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. The average call length with 25 departments reporting is just 9.5 minutes.

- Results: Survey results reveal an overall average improvement in awareness among DSB participants about hospital safety issues. Average days to issue resolution is currently 2.3 days, with open issues tracked and reported on daily.

- Conclusion: The DSB has improved real-time communication and awareness about safety issues in our organization.

As health care organizations strive to ensure a culture of safety for patients and staff, they must also be able to demonstrate reliability in that culture. The concept of highly reliable organizations originated in aviation and military fields due to the high-stakes environment and need for rapid and effective communication across departments. High reliability in health care organizations is described by the Joint Commission as consistent excellence in quality and safety for every patient, every time [1].

Highly reliable organizations put systems in place that makes them resilient with methods that lead to consistent accomplishment of goals and strategies to avoid potentially catastrophic errors [2]. An integral component to success in all high reliability organizations is a method of “Plan-of-the-Day” meetings to keep staff apprised of critical updates throughout the health system impacting care delivery [3]. Leaders at MetroHealth Medical Center believed that a daily safety briefing would help support the hospital’s journey to high reliability. We developed the Daily Safety Brief (DSB), a daily interdepartmental briefing intended to increase the safety of patients, employees, and visitors by improving communication and situational awareness. Situational awareness involves gathering the right information, analyzing it, and making predictions and projections based on the analysis [4]. Reporting issues while they are small oftentimes makes them easier to manage. This article will describe the development and implementation of the DSB in our hospital.

Setting

MetroHealth Medical Center is an academic medical center in Cleveland, OH, affiliated with Case Western Reserve University. Metrohealth is a public safety net hospital with 731 licensed beds and a total of 1,160,773 patient visits in 2014, with 27,933 inpatient stays and 106,000 emergency department (ED) visits. The staff includes 507 physicians, 374 resident physicians, and 1222 nurses.

Program Development

As Metrohealth was contemplating the DSB, a group of senior leaders, including the chief medical officer, visited the Cincinnati Children’s Hospital, which had a DSB process in place. Following that visit, a larger group of physicians and administrators from intake points, procedural areas, and ancillary departments were invited to listen in live to Cincinnati’s DSB. This turned out to be a pivotal step in gaining buy-in. The initial concerns from participants were that this would be another scheduled meeting in an already busy day. What we learned from listening in was that the DSB was conducted in a manner that was succinct and professional. Issues were identified without accusations or unrelated agendas. Following the call, participants discussed how impressed they were and clearly saw the value of the information that was shared. They began to brainstorm about what they could report that would be relevant to the audience.

It was determined that a leader and 2 facilitators would be assigned to each call. The role of the DSB leader is to trigger individual department report outs and to ensure follow-up on unresolved safety issues from the previous DSB. Leaders are recruited by senior leadership and need to be familiar with the effects that issues can have across the health care system. Leaders need to be able to ask pertinent questions, have the credibility to raise concerns, and have access to senior administration when they need to bypass usual administrative channels.

The role of the facilitators, who are all members of the Center for Quality, is to connect to the conference bridge line, to keep the DSB leader on task, and to record all departmental data and pertinent details of the DSB. The facilitators maintain the daily DSB document, which outlines the order in which departments are called to report and identifies for the leader any open items identified in the previous day’s DSB.

The Daily Safety Brief

Rollout

The DSB began 3 days per week on Monday, Wednesday and Friday at 0830. The time was moved to 0800 since participants found the later time difficult as it fell in the middle of an hour, potentially conflicting with other meetings and preparation for the daily bed huddle. We recognized that many meetings began right at the start of the DSB. The CEO requested that all 0800 meetings begin with a call in to listen to the DSB. After 2 months, the frequency was increased to 5 days per week, Monday through Friday. The hospital trialed a weekend DSB, however, feedback from participants found this extremely difficult to attend due to leaner weekend staffing models and found that information shared was not impactful. In particular, items were identified on the weekend daily safety briefs but the staff needed to resolve those items were generally not available until Monday.

Refinements

Coaching occurred to help people be more succinct in sharing information that would impact other areas. Information that was relevant only internally to their department was streamlined. The participants were counseled to identify items that had potential impact on other departments or where other departments had resources that might improve operations.

After a year, participating departments requested the addition of the logistics and construction departments to the DSB. The addition of the logistics department offered the opportunity for clinical departments to communicate what equipment was needed to start the day and created the opportunity for logistics to close the feedback loop by giving an estimate on expected time of arrival of equipment. The addition of the construction department helped communicate issues that may impact the organization, and helps to coordinate care to minimally impact patients and operations.

Examples of Safety Improvements

The DSB keeps the departmental leadership aware of problems developing in all areas of the hospital. Upcoming safety risks are identified early so that plans can be put in place to ameliorate them. The expectation of the DSB leader is that a problem that isn’t readily solved during the DSB must be taken to senior administration for resolution. As an example, an issue involving delays in the purchase of a required neonatal ventilator was taken directly to the CEO by the DSB leader, resulting in completion of the purchase within days. Importantly, the requirement to report at the DSB leads to a preoccupation with risk and reporting and leads to transparency among interdependent departments.

Another issue effectively addressed by the DSB was when we received notification of a required mandatory power shutdown for an extended period of time. The local power company informed our facilities management department director that they discovered issues requiring urgent replacement of the transformer within 2 weeks. Facilities management reported this in the morning DSB. The DSB leader requested all stakeholders to stay on the call following completion of the DSB, and plans were set in motion to plan for the shutdown of power. The team agreed to conference call again at noon the same day to continue planning, and the affected building was prepared for the shutdown by the following day.

Another benefit of the DSB is illustrated by our inpatient psychiatry unit, which reports an acuity measure each day on a scale of 1 to 10. The MetroHealth Police Department utilizes the report to adjust their rounding schedule, with increased presence on days with high acuity, which has led to an improvement in morale among psychiatry unit staff.

Challenges and Solutions

Since these reports are available to a wide audience in the organization, it is important to assure the reporters that no repercussions will ensue from any information that they provide. Senior leadership was enlisted to communicate with their departments that no repercussions would occur from reporting. As an example, some managers reported to the DSB development team privately that their supervisors were concerned about reporting of staff shortages on the DSB. As the shortages had patient care implications and affected other clinical departments, the DSB development team met with the involved supervisors to address the need for open reporting. In fact, repeated reporting of shortages in one support department on the DSB resulted in that issue being taken to high levels of administration leading to an increase in their staffing levels.

Scheduling can be a challenge for DSB participants. Holding the DSB at 0800 has led some departments to delegate the reporting or information gathering. For the individual reporting departments, creating a reporting workflow was a challenge. The departments needed to ensure that their DSB report was ready to go by 0800. This timeline forced departments to improve their own interdepartmental communication structure. An unexpected benefit of this requirement is that some departments have created a morning huddle to share information, which has reportedly improved communication and morale. The ambulatory network created a separate shared database for clinics to post concerns meeting DSB reporting criteria. One designated staff member would access this collective information when preparing for the DSB report. While most departments have a senior manager providing their report, this is not a requirement. In many departments, that reporter varies from day to day, although consistently it is someone with some administrative or leadership role in the department.

Conference call technology presented the solution to the problem of acquiring a meeting space for a large group. The DSB is broadcast from one physical location, where the facilitators and leader convene. While this conference room is open to anyone who wants to attend in person, most departments choose to participate through the conference line. The DSB conference call is open to anyone in the organization to access. Typically 35 to 40 phones are accessing the line each DSB. Challenges included callers not muting their phones, creating distracting background noise, and callers placing their phones on hold, which prompted the hospital hold message to play continuously. Multiple repeated reminders via email and at the start of the DSB has rectified this issue for the most part, with occasional reminders made when the issue recurs.

Data Management

Initially, an Excel file was created with columns for each reporting department as well as each item they were asked to report on. This “running” file became cumbersome. Retrieving information on past issues was not automated. Therefore, we enlisted the help of a data analyst to create an Access database. When it was complete, this new database allowed us to save information by individual dates, query number of days to issue resolution, and create reports noting unresolved issues for the leader to reference. Many data points can be queried in the access database. Real-time reports are available at all times and updated with every data entry. The database is able to identify departments not on the daily call and trend information, ie, how many listeners were on the DSB, number of falls, forensic patients in house, number of patients awaiting admission from the ED, number of ambulatory visits scheduled each day, equipment needed, number of cardiac arrest calls, and number of neonatal resuscitations.

At the conclusion of the call, the DSB report is completed and posted to a shared website on the hospital intranet for the entire hospital to access and read. Feedback from participant indicated that they found it cumbersome to access this. The communications department was enlisted to enable easy access and staff can now access the DSB report from the front page of the hospital intranet.

Outcomes

Since initiation of our DSB, we have tracked the average number of minutes spent on each call. When calls began, the average time on the call was 12.4 minutes. With the evolution of the DSB and coaching managers in various departments, the average time on the call is now 9.5 minutes in 2015, despite additional reporting departments joining the DSB.

Summary

The DSB has become an important tool in creating and moving towards a culture of safety and high reliability within the MetroHealth System. Over time, processes have become organized and engrained in all departments. This format has allowed issues to be brought forward timely where immediate attention can be given to achieve resolution in a nonthreatening manner, improving transparency. The fluidity of the DSB allows it to be enhanced and modified as improvements and opportunities are identified in the organization. The DSB has provided opportunities to create situational awareness which allows a look forward to prevention and creates a proactive environment. The results of these efforts has made MetroHealth a safer place for patients, visitors, and employees.

Corresponding author: Anne M. Aulisio, MSN, aaulisio@metrohealth.org.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Available at www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org.

2. Gamble M. 5 traits of high reliability organizations: how to hardwire each in your organization. Becker’s Hospital Review 29 Apr 2013. Accessed at www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/5-traits-of-high-reliability-organizations-how-to-hardwire-each-in-your-organization.html.

3. Stockmeier C, Clapper C. Daily check-in for safety: from best practice to common practice. Patient Safety Qual Healthcare 2011:23. Accessed at psqh.com/daily-check-in-for-safety-from-best-practice-to-common-practice.

4. Creating situational awareness: a systems approach. In: Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events. Medical surge capacity: workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32859/.

5. TeamSTEPPS. Available at www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/index.html.

1. Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare. Available at www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org.

2. Gamble M. 5 traits of high reliability organizations: how to hardwire each in your organization. Becker’s Hospital Review 29 Apr 2013. Accessed at www.beckershospitalreview.com/hospital-management-administration/5-traits-of-high-reliability-organizations-how-to-hardwire-each-in-your-organization.html.

3. Stockmeier C, Clapper C. Daily check-in for safety: from best practice to common practice. Patient Safety Qual Healthcare 2011:23. Accessed at psqh.com/daily-check-in-for-safety-from-best-practice-to-common-practice.

4. Creating situational awareness: a systems approach. In: Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Catastrophic Events. Medical surge capacity: workshop summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. Accessed at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32859/.

5. TeamSTEPPS. Available at www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/teamstepps/index.html.