User login

Dos and don’ts for handling common sling complications

Large-scale randomized trials have not only documented the efficacy of minimally invasive midurethral slings for stress urinary continence, they have also provided more adequate data on the incidence of complications. In practice, meanwhile, we are seeing more complications as the number of midurethral sling placements increases.

Often times, complications can be significantly more impactful than the original urinary incontinence. It is important to take the complications of sling placement seriously. Let patients know that their symptoms matter, and that there are ways to manage complications.

With more long-term data and experience, we have learned more about what to do, and what not to do, to prevent, diagnose, and manage the complications associated with midurethral slings. Here is my approach to the complications most commonly encountered, including bladder perforation, voiding dysfunction, erosion, pain, and recurrent stress urinary incontinence.

I will not address vascular injury in this article, but certainly, this is a surgical emergency that needs to be handled as such. As described in the February 2015 edition of Master Class on midurethral sling technique, accurate visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder during needle passage is an essential part of preventing vascular injuries during retropubic sling placement.

Bladder perforation

Bladder perforation has consistently been shown to be significantly more common with retropubic slings than with transobturator slings. Reported incidence has ranged from 0.8% to 34% for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedures, with the higher rates seen mainly in teaching institutions. Most commonly, the reported incidence is less than 10%.

Bladder perforation has no effect on the efficacy of the treatment, and no apparent long-term consequences, as long as the injury is identified. Especially with a retropubic sling, cystoscopy should be performed after both needles are placed but prior to advancing the needles all the way through the retropubic space. Simply withdrawing a needle will cause little bladder injury while retracting deployed mesh is significantly more consequential.

I recommend filling the bladder to approximately 300 cc, or to the point where you can see evidence of full distension such as flattened urethral orifices. This confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles or folds that can hide a trocar injury.

The first step upon recognition of a perforation is to stay calm. In the vast majority of cases, simply withdrawing the needle, replacing it, and verifying correct replacement will prevent any long-term consequences. On the other hand, you must be fully alert to the possibility that the needle wandered away from the pubic bone, and consequently may have entered a space such as the peritoneum. Suspicion for visceral injury should be increased.

Resist the temptation to replace the needle more laterally. This course correction is often an unhelpful instinct, because a more lateral replacement will not move the needle farther from the bladder; it will instead bring it closer to the iliac vessels. Vascular injuries resulting from the surgeon’s attempts at needle replacement are unfortunate, as a minor complication becomes a major one. The key is to be as distal as possible – as close to the pubic bone as possible – and not to replace the needles more laterally.

Postoperative drainage for 1-2 days may be considered, but there is nothing in the literature to require this, and many surgeons do not employ any sort of extra catheterization after surgery where perforation has been observed.

Voiding dysfunction

Some degree of voiding dysfunction is not uncommon in the short term, but when a patient is still unable to void normally or completely after several days, an evaluation is warranted. As with bladder perforation, reported incidence of voiding dysfunction has varied widely, from 2% to 45% with the newer midurethral slings. Generally, the need for surgical revision is about 2%.

There are two reasons for urinary retention: Insufficient contraction force in the bladder or too much resistance. If retention persists beyond a week – in the 7-10 day postop time period – I assess whether the problem is resulting from too much obstruction from the sling, some form of hypotonic bladder, other surgery performed in conjunction with sling placement, medications, or something else.

Difficulty in passing a small urethra catheter in the office may indicate excessive obstruction, for instance, and there may be indications on vaginal examination or through cystoscopy that the sling is too tight. A midurethral “speed bump,” or elevation at the midpoint, with either catheterization or the scope is consistent with over-correction.

Do not dilate or pull down on the sling with any kind of urethra dilator. The sling is more robust than the urethral mucosa, and we now appreciate that this practice is associated with urethral erosion.

If the problem is deemed to be excessive obstruction or over-resistance, and it is fewer than 10 days postop, the patient may be offered a minor revision; the original incision is reopened, the sling material is identified, and the sling arms (lateral to the urethra) are grasped with clamps. Gentle downward traction can loosen the sling.

The sling should be grasped laterally and not at the midpoint; some sling materials will stretch and fracture where the force is applied. A little bit of gentle downward traction (3-5 mm) will often give you the needed amount of space for relieving some of the obstruction.

Beyond 10 days postop, tissue in-growth makes such a sling adjustment difficult, if not impossible. At this point, I recommend transecting the entire sling in the midline.There is differing opinion about whether a portion of the mesh should be resected; I believe that such a resection is usually unnecessary, and that a simple midline release procedure is the best approach.

A study we performed more than a decade ago on surgical release of TVT showed that persistent post-TVT voiding dysfunction can be successfully managed with a simple midline release. Of 1,175 women who underwent TVT placement for stress urinary incontinence and/or intrinsic sphincter deficiency, 23 (1.9%) had persistent voiding dysfunction. All cases of impaired emptying were completely resolved with a release of the tape, and the majority remained cured in terms of their continence or went from “cured” to “improved” over baseline. Three patients (13%) had recurrence of stress incontinence (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:898-902).

We used to wait longer before revising the sling out of fear of losing the entire benefit of the sling. As it turns out, a simple midline release (leaving most, if not all, of the mesh in place) is usually just enough to treat the new complaint while still providing enough lateral support so that the patient retains most or all of the continence achieved with the sling.

Complaints of de novo urge incontinence, or overactive bladder, should be taken seriously. Urge incontinence has even more significant associations with depression and poor quality of life than stress incontinence. In the absence of retention, usual first-line therapies for overactive bladder can be employed, including anticholinergic medications, behavioral therapies, and physical therapy. Failing these interventions, my assessment for this complaint will be similar to that for retention; I’ll look for evidence of too much resistance, such as difficulty in passing a catheter, a “speed bump” cystoscopically, or an elevated pDet on pressure-flow studies, for instance.

If any of these are present, I usually offer sling release first. If, on the other hand, there is no evidence of over resistance in a patient who has de novo urge incontinence or overactive bladder and is refractory to conservative measures, a trial of sacral neuromodulation or botox injections is considered the next step.

Erosion

Erosion remains a difficult complication to understand. Long-term follow-up data show that it occurs after 3%-4% of sling placements, rather than 1% as originally believed. Data are inconsistent, but there probably is a slightly higher incidence of vaginal erosion with a transobturator sling, given more contact between the sling and the anterior vaginal wall.

There are hints in the literature that erosion may be related to technique – perhaps to the depth of dissection during surgery – but this is difficult to quantify. Moreover, many of the reported cases of erosion occur several years, or longer, after surgery. It is hard to blame surgical technique for such delayed erosion.

As we’ve seen with previous generations of mesh, there does not appear to be any window of time after which erosion is no longer a risk. We need to recognize that there is a medium- and long-term risk of erosion and appreciate its presenting symptoms: Recurrent urinary tract infection, pain with voiding, urgency, urinary incontinence, and microscopic hematuria of new onset.

Prevention may well entail preoperative estrogenization. The science looking at the effect of estrogen on sling placement is becoming more robust. While there are uncertainties, I believe that studies likely will show that topical estrogen in the preoperative and perioperative phases plays an important role in preventing erosion from occurring. Personally, I am using it much more than I was 10 years ago.

I like the convenience of the Vagifem tablet (Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, N.J.), and am reassured by data on systemic absorption with the 10-mcg dose, but any vaginal cream or compounded suppository can be used. I usually advise 4-6 weeks of preoperative preparation, with nightly use for 2 weeks followed by 2-3 nights per week thereafter. Smoking is also a likely risk factor. Data are not entirely consistent, but I believe we should provide counseling and encourage smoking cessation before the implant of mesh.

Management is dependent on when the erosion occurs or is recognized. When erosion occurs within 6 weeks post operatively, primary repair is an option. When erosion is detected after the 6-week window and is causing symptoms, a conservative trim of bristles poking through the vaginal mucosa is worth a try. I do not advise more than one such conservative trim, however, as repeated attempts and series of small resections can make the sling exceedingly difficult to remove if more complete resection is ultimately needed. After one unsuccessful trim, I usually remove the whole sling belly, or most of the vaginal part of the sling.

For slings made of type 1 macroporous mesh, resection of the retropubic or transobturator portions of the mesh usually is not required. In the more rare situation where those pelvic areas of the mesh are associated with pain, I favor a laparoscopic approach to the retropubic space to facilitate minimally invasive removal.

Postop pain, sling failure

Groin pain, or thigh pain, sometimes occurs after placement of a transobturator sling. As I discussed in the previous Master Class on midurethral sling technique, I have seen a significant decrease in groin pain in my patients – without any reduction in benefit – with the use of a shorter transobturator sling that does not leave mesh in the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

For persistent groin pain, I favor the use of trigger point injection. Sometimes one injection will impact the inflammatory cycle such that the patient derives long-term benefit. At other times, the trigger point injection will serve as a diagnostic; if pain returns after a period of benefit, I am inclined to resect that part of the mesh.

Pain inside the pelvis, especially on the pelvic sidewall (obturator or puborectalis complex) usually is related to mechanical tension. In my experience, this type of discomfort is slightly more likely to occur with the transobturator slings, which penetrate through the muscular pelvic sidewall and lead to more fibrosis and scar tissue formation.

In most cases of pain and discomfort, attempting to reproduce the patient’s symptoms by putting tension on particular parts of the sling during the office exam helps guide management. If I find that palpating or putting the sling on tension recreates her complaints, and conservative injections have provided temporary or inadequate relief, I usually advocate resecting the vaginal portion of the mesh to relieve that tension.

In cases of recurrent stress urinary incontinence (when the sling has failed), a TVT or repeat TVT is often warranted. The TVT sling has been demonstrated to work after nearly every other previous kind of anti-incontinence procedure, even after a previous retropubic sling. There is little data on mesh removal in such cases. I believe that unless a previously placed but failed sling is causing symptoms, there is no need to resect it. Mesh removal is significantly more traumatic than mesh placement, and in most cases it is not necessary.

Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Large-scale randomized trials have not only documented the efficacy of minimally invasive midurethral slings for stress urinary continence, they have also provided more adequate data on the incidence of complications. In practice, meanwhile, we are seeing more complications as the number of midurethral sling placements increases.

Often times, complications can be significantly more impactful than the original urinary incontinence. It is important to take the complications of sling placement seriously. Let patients know that their symptoms matter, and that there are ways to manage complications.

With more long-term data and experience, we have learned more about what to do, and what not to do, to prevent, diagnose, and manage the complications associated with midurethral slings. Here is my approach to the complications most commonly encountered, including bladder perforation, voiding dysfunction, erosion, pain, and recurrent stress urinary incontinence.

I will not address vascular injury in this article, but certainly, this is a surgical emergency that needs to be handled as such. As described in the February 2015 edition of Master Class on midurethral sling technique, accurate visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder during needle passage is an essential part of preventing vascular injuries during retropubic sling placement.

Bladder perforation

Bladder perforation has consistently been shown to be significantly more common with retropubic slings than with transobturator slings. Reported incidence has ranged from 0.8% to 34% for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedures, with the higher rates seen mainly in teaching institutions. Most commonly, the reported incidence is less than 10%.

Bladder perforation has no effect on the efficacy of the treatment, and no apparent long-term consequences, as long as the injury is identified. Especially with a retropubic sling, cystoscopy should be performed after both needles are placed but prior to advancing the needles all the way through the retropubic space. Simply withdrawing a needle will cause little bladder injury while retracting deployed mesh is significantly more consequential.

I recommend filling the bladder to approximately 300 cc, or to the point where you can see evidence of full distension such as flattened urethral orifices. This confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles or folds that can hide a trocar injury.

The first step upon recognition of a perforation is to stay calm. In the vast majority of cases, simply withdrawing the needle, replacing it, and verifying correct replacement will prevent any long-term consequences. On the other hand, you must be fully alert to the possibility that the needle wandered away from the pubic bone, and consequently may have entered a space such as the peritoneum. Suspicion for visceral injury should be increased.

Resist the temptation to replace the needle more laterally. This course correction is often an unhelpful instinct, because a more lateral replacement will not move the needle farther from the bladder; it will instead bring it closer to the iliac vessels. Vascular injuries resulting from the surgeon’s attempts at needle replacement are unfortunate, as a minor complication becomes a major one. The key is to be as distal as possible – as close to the pubic bone as possible – and not to replace the needles more laterally.

Postoperative drainage for 1-2 days may be considered, but there is nothing in the literature to require this, and many surgeons do not employ any sort of extra catheterization after surgery where perforation has been observed.

Voiding dysfunction

Some degree of voiding dysfunction is not uncommon in the short term, but when a patient is still unable to void normally or completely after several days, an evaluation is warranted. As with bladder perforation, reported incidence of voiding dysfunction has varied widely, from 2% to 45% with the newer midurethral slings. Generally, the need for surgical revision is about 2%.

There are two reasons for urinary retention: Insufficient contraction force in the bladder or too much resistance. If retention persists beyond a week – in the 7-10 day postop time period – I assess whether the problem is resulting from too much obstruction from the sling, some form of hypotonic bladder, other surgery performed in conjunction with sling placement, medications, or something else.

Difficulty in passing a small urethra catheter in the office may indicate excessive obstruction, for instance, and there may be indications on vaginal examination or through cystoscopy that the sling is too tight. A midurethral “speed bump,” or elevation at the midpoint, with either catheterization or the scope is consistent with over-correction.

Do not dilate or pull down on the sling with any kind of urethra dilator. The sling is more robust than the urethral mucosa, and we now appreciate that this practice is associated with urethral erosion.

If the problem is deemed to be excessive obstruction or over-resistance, and it is fewer than 10 days postop, the patient may be offered a minor revision; the original incision is reopened, the sling material is identified, and the sling arms (lateral to the urethra) are grasped with clamps. Gentle downward traction can loosen the sling.

The sling should be grasped laterally and not at the midpoint; some sling materials will stretch and fracture where the force is applied. A little bit of gentle downward traction (3-5 mm) will often give you the needed amount of space for relieving some of the obstruction.

Beyond 10 days postop, tissue in-growth makes such a sling adjustment difficult, if not impossible. At this point, I recommend transecting the entire sling in the midline.There is differing opinion about whether a portion of the mesh should be resected; I believe that such a resection is usually unnecessary, and that a simple midline release procedure is the best approach.

A study we performed more than a decade ago on surgical release of TVT showed that persistent post-TVT voiding dysfunction can be successfully managed with a simple midline release. Of 1,175 women who underwent TVT placement for stress urinary incontinence and/or intrinsic sphincter deficiency, 23 (1.9%) had persistent voiding dysfunction. All cases of impaired emptying were completely resolved with a release of the tape, and the majority remained cured in terms of their continence or went from “cured” to “improved” over baseline. Three patients (13%) had recurrence of stress incontinence (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:898-902).

We used to wait longer before revising the sling out of fear of losing the entire benefit of the sling. As it turns out, a simple midline release (leaving most, if not all, of the mesh in place) is usually just enough to treat the new complaint while still providing enough lateral support so that the patient retains most or all of the continence achieved with the sling.

Complaints of de novo urge incontinence, or overactive bladder, should be taken seriously. Urge incontinence has even more significant associations with depression and poor quality of life than stress incontinence. In the absence of retention, usual first-line therapies for overactive bladder can be employed, including anticholinergic medications, behavioral therapies, and physical therapy. Failing these interventions, my assessment for this complaint will be similar to that for retention; I’ll look for evidence of too much resistance, such as difficulty in passing a catheter, a “speed bump” cystoscopically, or an elevated pDet on pressure-flow studies, for instance.

If any of these are present, I usually offer sling release first. If, on the other hand, there is no evidence of over resistance in a patient who has de novo urge incontinence or overactive bladder and is refractory to conservative measures, a trial of sacral neuromodulation or botox injections is considered the next step.

Erosion

Erosion remains a difficult complication to understand. Long-term follow-up data show that it occurs after 3%-4% of sling placements, rather than 1% as originally believed. Data are inconsistent, but there probably is a slightly higher incidence of vaginal erosion with a transobturator sling, given more contact between the sling and the anterior vaginal wall.

There are hints in the literature that erosion may be related to technique – perhaps to the depth of dissection during surgery – but this is difficult to quantify. Moreover, many of the reported cases of erosion occur several years, or longer, after surgery. It is hard to blame surgical technique for such delayed erosion.

As we’ve seen with previous generations of mesh, there does not appear to be any window of time after which erosion is no longer a risk. We need to recognize that there is a medium- and long-term risk of erosion and appreciate its presenting symptoms: Recurrent urinary tract infection, pain with voiding, urgency, urinary incontinence, and microscopic hematuria of new onset.

Prevention may well entail preoperative estrogenization. The science looking at the effect of estrogen on sling placement is becoming more robust. While there are uncertainties, I believe that studies likely will show that topical estrogen in the preoperative and perioperative phases plays an important role in preventing erosion from occurring. Personally, I am using it much more than I was 10 years ago.

I like the convenience of the Vagifem tablet (Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, N.J.), and am reassured by data on systemic absorption with the 10-mcg dose, but any vaginal cream or compounded suppository can be used. I usually advise 4-6 weeks of preoperative preparation, with nightly use for 2 weeks followed by 2-3 nights per week thereafter. Smoking is also a likely risk factor. Data are not entirely consistent, but I believe we should provide counseling and encourage smoking cessation before the implant of mesh.

Management is dependent on when the erosion occurs or is recognized. When erosion occurs within 6 weeks post operatively, primary repair is an option. When erosion is detected after the 6-week window and is causing symptoms, a conservative trim of bristles poking through the vaginal mucosa is worth a try. I do not advise more than one such conservative trim, however, as repeated attempts and series of small resections can make the sling exceedingly difficult to remove if more complete resection is ultimately needed. After one unsuccessful trim, I usually remove the whole sling belly, or most of the vaginal part of the sling.

For slings made of type 1 macroporous mesh, resection of the retropubic or transobturator portions of the mesh usually is not required. In the more rare situation where those pelvic areas of the mesh are associated with pain, I favor a laparoscopic approach to the retropubic space to facilitate minimally invasive removal.

Postop pain, sling failure

Groin pain, or thigh pain, sometimes occurs after placement of a transobturator sling. As I discussed in the previous Master Class on midurethral sling technique, I have seen a significant decrease in groin pain in my patients – without any reduction in benefit – with the use of a shorter transobturator sling that does not leave mesh in the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

For persistent groin pain, I favor the use of trigger point injection. Sometimes one injection will impact the inflammatory cycle such that the patient derives long-term benefit. At other times, the trigger point injection will serve as a diagnostic; if pain returns after a period of benefit, I am inclined to resect that part of the mesh.

Pain inside the pelvis, especially on the pelvic sidewall (obturator or puborectalis complex) usually is related to mechanical tension. In my experience, this type of discomfort is slightly more likely to occur with the transobturator slings, which penetrate through the muscular pelvic sidewall and lead to more fibrosis and scar tissue formation.

In most cases of pain and discomfort, attempting to reproduce the patient’s symptoms by putting tension on particular parts of the sling during the office exam helps guide management. If I find that palpating or putting the sling on tension recreates her complaints, and conservative injections have provided temporary or inadequate relief, I usually advocate resecting the vaginal portion of the mesh to relieve that tension.

In cases of recurrent stress urinary incontinence (when the sling has failed), a TVT or repeat TVT is often warranted. The TVT sling has been demonstrated to work after nearly every other previous kind of anti-incontinence procedure, even after a previous retropubic sling. There is little data on mesh removal in such cases. I believe that unless a previously placed but failed sling is causing symptoms, there is no need to resect it. Mesh removal is significantly more traumatic than mesh placement, and in most cases it is not necessary.

Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Large-scale randomized trials have not only documented the efficacy of minimally invasive midurethral slings for stress urinary continence, they have also provided more adequate data on the incidence of complications. In practice, meanwhile, we are seeing more complications as the number of midurethral sling placements increases.

Often times, complications can be significantly more impactful than the original urinary incontinence. It is important to take the complications of sling placement seriously. Let patients know that their symptoms matter, and that there are ways to manage complications.

With more long-term data and experience, we have learned more about what to do, and what not to do, to prevent, diagnose, and manage the complications associated with midurethral slings. Here is my approach to the complications most commonly encountered, including bladder perforation, voiding dysfunction, erosion, pain, and recurrent stress urinary incontinence.

I will not address vascular injury in this article, but certainly, this is a surgical emergency that needs to be handled as such. As described in the February 2015 edition of Master Class on midurethral sling technique, accurate visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder during needle passage is an essential part of preventing vascular injuries during retropubic sling placement.

Bladder perforation

Bladder perforation has consistently been shown to be significantly more common with retropubic slings than with transobturator slings. Reported incidence has ranged from 0.8% to 34% for tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) procedures, with the higher rates seen mainly in teaching institutions. Most commonly, the reported incidence is less than 10%.

Bladder perforation has no effect on the efficacy of the treatment, and no apparent long-term consequences, as long as the injury is identified. Especially with a retropubic sling, cystoscopy should be performed after both needles are placed but prior to advancing the needles all the way through the retropubic space. Simply withdrawing a needle will cause little bladder injury while retracting deployed mesh is significantly more consequential.

I recommend filling the bladder to approximately 300 cc, or to the point where you can see evidence of full distension such as flattened urethral orifices. This confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles or folds that can hide a trocar injury.

The first step upon recognition of a perforation is to stay calm. In the vast majority of cases, simply withdrawing the needle, replacing it, and verifying correct replacement will prevent any long-term consequences. On the other hand, you must be fully alert to the possibility that the needle wandered away from the pubic bone, and consequently may have entered a space such as the peritoneum. Suspicion for visceral injury should be increased.

Resist the temptation to replace the needle more laterally. This course correction is often an unhelpful instinct, because a more lateral replacement will not move the needle farther from the bladder; it will instead bring it closer to the iliac vessels. Vascular injuries resulting from the surgeon’s attempts at needle replacement are unfortunate, as a minor complication becomes a major one. The key is to be as distal as possible – as close to the pubic bone as possible – and not to replace the needles more laterally.

Postoperative drainage for 1-2 days may be considered, but there is nothing in the literature to require this, and many surgeons do not employ any sort of extra catheterization after surgery where perforation has been observed.

Voiding dysfunction

Some degree of voiding dysfunction is not uncommon in the short term, but when a patient is still unable to void normally or completely after several days, an evaluation is warranted. As with bladder perforation, reported incidence of voiding dysfunction has varied widely, from 2% to 45% with the newer midurethral slings. Generally, the need for surgical revision is about 2%.

There are two reasons for urinary retention: Insufficient contraction force in the bladder or too much resistance. If retention persists beyond a week – in the 7-10 day postop time period – I assess whether the problem is resulting from too much obstruction from the sling, some form of hypotonic bladder, other surgery performed in conjunction with sling placement, medications, or something else.

Difficulty in passing a small urethra catheter in the office may indicate excessive obstruction, for instance, and there may be indications on vaginal examination or through cystoscopy that the sling is too tight. A midurethral “speed bump,” or elevation at the midpoint, with either catheterization or the scope is consistent with over-correction.

Do not dilate or pull down on the sling with any kind of urethra dilator. The sling is more robust than the urethral mucosa, and we now appreciate that this practice is associated with urethral erosion.

If the problem is deemed to be excessive obstruction or over-resistance, and it is fewer than 10 days postop, the patient may be offered a minor revision; the original incision is reopened, the sling material is identified, and the sling arms (lateral to the urethra) are grasped with clamps. Gentle downward traction can loosen the sling.

The sling should be grasped laterally and not at the midpoint; some sling materials will stretch and fracture where the force is applied. A little bit of gentle downward traction (3-5 mm) will often give you the needed amount of space for relieving some of the obstruction.

Beyond 10 days postop, tissue in-growth makes such a sling adjustment difficult, if not impossible. At this point, I recommend transecting the entire sling in the midline.There is differing opinion about whether a portion of the mesh should be resected; I believe that such a resection is usually unnecessary, and that a simple midline release procedure is the best approach.

A study we performed more than a decade ago on surgical release of TVT showed that persistent post-TVT voiding dysfunction can be successfully managed with a simple midline release. Of 1,175 women who underwent TVT placement for stress urinary incontinence and/or intrinsic sphincter deficiency, 23 (1.9%) had persistent voiding dysfunction. All cases of impaired emptying were completely resolved with a release of the tape, and the majority remained cured in terms of their continence or went from “cured” to “improved” over baseline. Three patients (13%) had recurrence of stress incontinence (Obstet. Gynecol. 2002;100:898-902).

We used to wait longer before revising the sling out of fear of losing the entire benefit of the sling. As it turns out, a simple midline release (leaving most, if not all, of the mesh in place) is usually just enough to treat the new complaint while still providing enough lateral support so that the patient retains most or all of the continence achieved with the sling.

Complaints of de novo urge incontinence, or overactive bladder, should be taken seriously. Urge incontinence has even more significant associations with depression and poor quality of life than stress incontinence. In the absence of retention, usual first-line therapies for overactive bladder can be employed, including anticholinergic medications, behavioral therapies, and physical therapy. Failing these interventions, my assessment for this complaint will be similar to that for retention; I’ll look for evidence of too much resistance, such as difficulty in passing a catheter, a “speed bump” cystoscopically, or an elevated pDet on pressure-flow studies, for instance.

If any of these are present, I usually offer sling release first. If, on the other hand, there is no evidence of over resistance in a patient who has de novo urge incontinence or overactive bladder and is refractory to conservative measures, a trial of sacral neuromodulation or botox injections is considered the next step.

Erosion

Erosion remains a difficult complication to understand. Long-term follow-up data show that it occurs after 3%-4% of sling placements, rather than 1% as originally believed. Data are inconsistent, but there probably is a slightly higher incidence of vaginal erosion with a transobturator sling, given more contact between the sling and the anterior vaginal wall.

There are hints in the literature that erosion may be related to technique – perhaps to the depth of dissection during surgery – but this is difficult to quantify. Moreover, many of the reported cases of erosion occur several years, or longer, after surgery. It is hard to blame surgical technique for such delayed erosion.

As we’ve seen with previous generations of mesh, there does not appear to be any window of time after which erosion is no longer a risk. We need to recognize that there is a medium- and long-term risk of erosion and appreciate its presenting symptoms: Recurrent urinary tract infection, pain with voiding, urgency, urinary incontinence, and microscopic hematuria of new onset.

Prevention may well entail preoperative estrogenization. The science looking at the effect of estrogen on sling placement is becoming more robust. While there are uncertainties, I believe that studies likely will show that topical estrogen in the preoperative and perioperative phases plays an important role in preventing erosion from occurring. Personally, I am using it much more than I was 10 years ago.

I like the convenience of the Vagifem tablet (Novo Nordisk Inc., Plainsboro, N.J.), and am reassured by data on systemic absorption with the 10-mcg dose, but any vaginal cream or compounded suppository can be used. I usually advise 4-6 weeks of preoperative preparation, with nightly use for 2 weeks followed by 2-3 nights per week thereafter. Smoking is also a likely risk factor. Data are not entirely consistent, but I believe we should provide counseling and encourage smoking cessation before the implant of mesh.

Management is dependent on when the erosion occurs or is recognized. When erosion occurs within 6 weeks post operatively, primary repair is an option. When erosion is detected after the 6-week window and is causing symptoms, a conservative trim of bristles poking through the vaginal mucosa is worth a try. I do not advise more than one such conservative trim, however, as repeated attempts and series of small resections can make the sling exceedingly difficult to remove if more complete resection is ultimately needed. After one unsuccessful trim, I usually remove the whole sling belly, or most of the vaginal part of the sling.

For slings made of type 1 macroporous mesh, resection of the retropubic or transobturator portions of the mesh usually is not required. In the more rare situation where those pelvic areas of the mesh are associated with pain, I favor a laparoscopic approach to the retropubic space to facilitate minimally invasive removal.

Postop pain, sling failure

Groin pain, or thigh pain, sometimes occurs after placement of a transobturator sling. As I discussed in the previous Master Class on midurethral sling technique, I have seen a significant decrease in groin pain in my patients – without any reduction in benefit – with the use of a shorter transobturator sling that does not leave mesh in the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

For persistent groin pain, I favor the use of trigger point injection. Sometimes one injection will impact the inflammatory cycle such that the patient derives long-term benefit. At other times, the trigger point injection will serve as a diagnostic; if pain returns after a period of benefit, I am inclined to resect that part of the mesh.

Pain inside the pelvis, especially on the pelvic sidewall (obturator or puborectalis complex) usually is related to mechanical tension. In my experience, this type of discomfort is slightly more likely to occur with the transobturator slings, which penetrate through the muscular pelvic sidewall and lead to more fibrosis and scar tissue formation.

In most cases of pain and discomfort, attempting to reproduce the patient’s symptoms by putting tension on particular parts of the sling during the office exam helps guide management. If I find that palpating or putting the sling on tension recreates her complaints, and conservative injections have provided temporary or inadequate relief, I usually advocate resecting the vaginal portion of the mesh to relieve that tension.

In cases of recurrent stress urinary incontinence (when the sling has failed), a TVT or repeat TVT is often warranted. The TVT sling has been demonstrated to work after nearly every other previous kind of anti-incontinence procedure, even after a previous retropubic sling. There is little data on mesh removal in such cases. I believe that unless a previously placed but failed sling is causing symptoms, there is no need to resect it. Mesh removal is significantly more traumatic than mesh placement, and in most cases it is not necessary.

Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

Expert tips on retropubic vs. transobturator sling approaches

Midurethral slings – both retropubic and transobturator – have been extensively studied and have evolved to become standard therapies for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. The two approaches utilize different routes for sling delivery, but in many other respects, they are similar. Improvements in technique are continually being developed. In this column, Dr. Sokol and Dr. Rardin share key parts of their technique and give their pearls of advice for midurethral sling surgery.

Dr. Sokol’s retropubic approach

I use newer retropubic midurethral slings with smaller trocars that have evolved from first-generation tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) slings. The slings I prefer are placed in a bottom-up fashion, with curved needles passed from a small vaginal incision up through the retropubic space to exit through two suprapubic incisions.

I find it helpful to place patients in a high lithotomy position with the legs supported in candy cane stirrups rather than Allen-type stirrups; sling placement is a short procedure with minimal to no risk of neuropathy.

To precisely identify the midurethral point, I use a 16-FR Foley catheter. When the catheter balloon is filled with 10 mm of fluid and gently pulled back, the urethrovesical junction can be identified. Then, by looking at the urethral meatus relative to the bladder neck, I can mark the midpoint between the two.

The suprapubic exit points are marked at two finger-widths lateral to the midline, just above the pubic symphysis. For precise identification of these points, the Foley catheter may be pulled up exactly midline (with the collection bag detached), and the two finger-widths measured on either side. I also aim for the ipsilateral shoulder, imagining a straight line from the urethral meatus to the ipsilateral shoulder on each side. Together, these measurements and visual cues serve as a good safety check.

With two Allis clamps, the vaginal wall on either side of the midline is grasped transversely at the level of the midurethral mark. The clamps will sit a couple of centimeters apart so that the midurethral point can be visualized. This helps to stabilize and elevate the midurethra.

To safely and efficiently develop a paraurethral passage, I perform a hydrodissection and hemostatic injection at the level of the midurethra using a control top 10-cc syringe with a 22-gauge needle. I find that dilute vasopressin saline solution affords better hemostasis than does a dilute lidocaine epinephrine solution, though I use dilute lidocaine if the sling is being done under local anesthesia.

The needle is inserted into a full thickness of skin, to a point shy of the urethra, and 10 cc is rapidly injected. The vaginal epithelium will appear blanched and will balloon out, like a white marble. The process basically lifts the vaginal skin away from the urethra itself, not only creating hemostasis but also providing a zone of safety to help avoid a urethral injury.

With a second syringe identical to the first, I inject 5 cc on each side of the midurethral point, aiming precisely at the underside of the pubic bone toward the ipsilateral shoulder. This creates a hydrodissected tunnel around each side of the midurethra. With a final syringe, I then inject 5 cc on each side suprapubically at my marked exit points.

With a #15 blade scalpel, I make two very small “poke” incisions transversely at the suprapubic sites. The suburethral incision is larger – just over a centimeter – and is made through a full thickness of skin under the area of hydrodissection, but not so deep as to injure the urethra. To finish development of the paraurethral passage, I pass standard Metzenbaum scissors through each hydrodissected tunnel until I feel the underside of the pubic bone, but no further.

For sling placement (after ensuring the bladder is completely empty), I lower the table such that my arm will be at a right angle to pass the sling while standing.

With my index finger underneath the pubic bone, the trocar tip, with the attached sling, is advanced with my thumb directly toward the ipsilateral shoulder just until it pops through the retropubic space. The depth of the trocar tip can be palpated with the index finger of the same hand, which is positioned just below the pelvic bone.

After the sling “pops” into the retropubic space, I remove my hand from the vagina and place it on the abdominal wall at the ipsilateral suprapubic poke site. In one smooth pass, I hug the pubic bone and advance the sling, again aiming directly and consistently at the shoulder. The trocar handle stays steady, never deviating in any direction. Cystoscopy is performed after the sling is placed on both sides to ensure bladder and urethral integrity.

For tensioning, I raise the table back up and, after reinserting the Foley catheter and a Sims retractor, I place my finger in the middle of the sling and pull the suprapubic ends of the sling up until my finger rests right under the urethra.

I then remove the vaginal clamps and use Metzenbaum scissors as a spacer between the sling and the urethra. With the scissors parallel to and right under the Foley catheter, at the same angle as the urethra, I tighten the sling and remove the plastic sheaths.

Dr. Sokol’s transobturator (TOT) approach

I most often use an outside-in sling. I utilize the same patient positioning and identify the midurethral point in the same way as with the retropubic approach.

On the thigh, I identify the adductor longus tendon as well as a little soft spot or depression just beneath the tendon and lateral to the descending ischial pubic ramus. With my thumb on the soft spot, I can actually grasp the adductor longus tendon between my thumb and index finger. This spot, which is also approximately at the level of the clitoris, marks the entry point for sling placement. It is the thinnest point between the groin and the vagina at the level of the midurethra.

I perform a similar hydrodissection under the urethra as I do in a retropubic procedure, though instead of injecting 5 cc’s to the underside of the pubic symphysis on each side, I instead inject toward the obturator internus muscles. I then inject my final syringe of dilute vasopressin saline solution at the groin poke incision sites, directed toward the projected trocar path, as opposed to suprapubically.

After the full-thickness vaginal incision is made with the scalpel, the dissection is performed sharply with Metzenbaum scissors and is more like the dissection done for cystocele repair than for a retropubic sling. Rather than a poke, the midurethral incision is long enough – about 1.5 cm – for me to reach a finger behind the obturator internus muscle after having sharply dissected the suburethral tissue and fascia. The angle of the dissection is more lateral than for a retropubic sling, toward the underside of the descending ischiopubic ramus and obturator internus muscle.

To place the sling, I have one hand with an index finger in the midurethral tunnel under the obturator internus muscle to protect the urethra. The thumb of that same hand is used to push the helical trocar straight through the thigh poke incision with the handle starting at a 35-degree angle from vertical. The trocar tip is pushed until it can no longer go straight and is ready to be tightly turned around the descending ischiopubic ramus with the opposite hand. A distinct pop can be felt as the trocar tip advances through the obturator membrane and muscles. As the tip is advanced, the angle of the trocar is rotated from 35 degrees to vertical, almost perpendicular to the floor. At this point, the tip of the trocar should be guided out of the midurethral tunnel against the opposite index finger.

I utilize the same technique for tensioning a TOT sling as I do the retropubic sling.

Dr. Rardin’s retropubic approach

I continue to use the original TVT sling with a 5-mm stainless steel, mechanically cut trocar and reusable handle. The newer slender needles may advance with less pressure, but I worry about them bending during passage. I feel more assured and comfortable using the older trocars.

I perform retropubic hydrodissection with a spinal needle using a top-down approach. With 40 cc of a very dilute solution of bupivacaine (Marcaine) with epinephrine on each side of the urethra, I create columns of hydrodissected space. Studies are inconsistent about the benefits of hydrodissection, but theoretically, it decreases the risk of bladder injury by pushing the bladder away from the pubic bone, creates effective hemostasis, and can provide analgesia that will be on board when the patient wakes up.

I bring the spinal needle down behind the pubic bone to the location of the urethral incision site, with my finger in the vagina, so I can feel the tip of the needle next to the urethra/Foley catheter. For each side, I will inject 20 cc of the solution in this location, and the other 20 cc as I withdraw the needle upward.

For trocar passage, some surgeons are taught to advance the trocar until a pop is felt, then drop the handle and push upward. I view the maneuver as a consistent, smooth arch; for every degree that I advance the trocar, I drop the handle slightly in order to maintain contact with the back of the pubic bone throughout the pass. I continuously and simultaneously drop the handle and advance the trocar. Contact with the back of the pubic bone is maintained with a slight pulling on the back end of the trocar handle, while the forward hand pushes the trocar upward.

The target that I visualize for a retropubic pass is the patient’s ipsilateral shoulder. A cadaver study showed that if you aim as far lateral as the patient’s outstretched elbow, you can enter the iliac vasculature (Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;101:933-6).

If the patient is draped such that I cannot see the ipsilateral shoulder, I ask the anesthesia team to show me. I have also identified and marked the suprapubic points about 2-3 cm from each other on either side of the midline just about the pubic symphysis, but I consider the broader anatomic picture and purposeful visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder to be an essential part of safe technique. In general, it is safer to be more medial than more lateral for the needle passage.

I continue to use a rigid catheter guide to deflect the bladder neck while passing the needles.

Cystoscopy is performed after both needles are placed but not yet pulled through. I fill the bladder until the ureteral orifices appear flattened, which confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles.

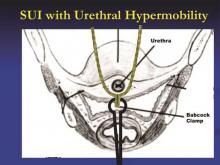

The technique I utilize for adjusting the tension of the TVT sling was taught to me by Dr. Peter L. Rosenblatt of Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Mass. At the midline of the sling, I advance the sheaths just enough so that I can grasp a 2-3 mm “knuckle” of the midportion of the sling with a Babcock clamp. I then pull the sling ends until the Babcock comes into gentle contact with the suburethral tissue. The sheaths encasing the sling are then removed and the Babcock clamp is released to assure a tension-free deployment.

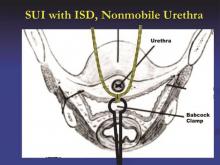

The amount of tape that is pinched with the Babcock – the size of the “knuckle” – determines the tension. For a patient with a more profound problem, such as intrinsic sphincter deficiency or a lack or urethral hypermobility, I will grasp a smaller knuckle.

These steps ensure that the midportion of the tape will not tighten or become deformed under tension. Rather than use a spacer, I like to protect the midportion of the tape and prevent it from being stretched. I find that the approach is reproducible and results in a reliable amount of space between the urethra and sling when the procedure is completed.

Dr. Rardin’s TOT approach

I employ an inside-out technique to the TOT procedure, and I utilize devices with segment of mesh that is shorter – only about 13 cm in length – than the original full-length mesh used in many TOT procedures. Once placed, the ends of the mesh penetrate the obturator membrane and obturator externus but not the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

In a study we presented last year at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons meeting, the shortened tape reduced postoperative groin pain, compared with full-length TOT tape without any reduction in subjective benefit. It appears that with shortened tape, we are anchoring the sling in tissues that provide critical support while avoiding the muscles that relate to the inner thigh/groin pain experienced by some patients. Effectiveness was not reduced, compared with full-length TOT slings.

These shortened slings are distinct from a single-incision sling, which is basically pushed into place. We still pass the needle all the way through a vaginal incision and out through the obturator foramen, and we pull the sling into place as we would any other TOT sling. The difference is that we’re not leaving any mesh in the groin.

I prefer an inside-out approach for two reasons: I always feel that I have more control over where a needle enters than where it exits, and precision is important with suburethral slings. Secondly, the dissection tunnel created for an inside-out pass is much smaller than the tunnel that must be dissected for an outside-in approach. In theory, less dissection means less devascularization, less denervation, and less opportunity for erosion.

Hydrodissection for TOT slings is more minimal and involves less fluid than does hydrodissection for retropubic slings, mainly because we do not want to anesthetize the obturator nerve. I pass the spinal needle from the outside in. At the start, prior to making any incisions, it is important to identify the arcus tendineus, a linear thickening of the superior fascia that is sometimes called the “white line.” This is where the sulcus is affixed to the sidewall. I will be sure to penetrate the sidewall at or above the level of the arcus.

With the TOT approach, the likelihood of bladder injury is so low that I usually drive the trocars all the way through prior to cystoscopy, as opposed to leaving the needles in place as I do with the retropubic approach.

Tensioning is achieved in the same manner, by using the Babcock clamp to avoid distortion of the critical part of the mesh while creating the space needed given the patient’s clinical scenario. It is worth remembering, at this point, that overall risks for retention appear to be lower for obturator slings, compared with retropubic slings.

I place most of my patients receiving retropubic slings in dorsal lithotomy position; but for obturator sling placement, I favor a few degrees into higher lithotomy because this pulls the obturator neurovascular bundle a little further out of the path of the needle.

Dr. Sokol reported that he owns stock in Pelvalon and is a clinical adviser to that company. He also is a national principal investigator for American Medical Systems and the recipient of research grants from Acell and several other companies. Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures. To view a video related to this article, go to SurgeryU at aagl.org/obgyn-news.

Midurethral slings – both retropubic and transobturator – have been extensively studied and have evolved to become standard therapies for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. The two approaches utilize different routes for sling delivery, but in many other respects, they are similar. Improvements in technique are continually being developed. In this column, Dr. Sokol and Dr. Rardin share key parts of their technique and give their pearls of advice for midurethral sling surgery.

Dr. Sokol’s retropubic approach

I use newer retropubic midurethral slings with smaller trocars that have evolved from first-generation tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) slings. The slings I prefer are placed in a bottom-up fashion, with curved needles passed from a small vaginal incision up through the retropubic space to exit through two suprapubic incisions.

I find it helpful to place patients in a high lithotomy position with the legs supported in candy cane stirrups rather than Allen-type stirrups; sling placement is a short procedure with minimal to no risk of neuropathy.

To precisely identify the midurethral point, I use a 16-FR Foley catheter. When the catheter balloon is filled with 10 mm of fluid and gently pulled back, the urethrovesical junction can be identified. Then, by looking at the urethral meatus relative to the bladder neck, I can mark the midpoint between the two.

The suprapubic exit points are marked at two finger-widths lateral to the midline, just above the pubic symphysis. For precise identification of these points, the Foley catheter may be pulled up exactly midline (with the collection bag detached), and the two finger-widths measured on either side. I also aim for the ipsilateral shoulder, imagining a straight line from the urethral meatus to the ipsilateral shoulder on each side. Together, these measurements and visual cues serve as a good safety check.

With two Allis clamps, the vaginal wall on either side of the midline is grasped transversely at the level of the midurethral mark. The clamps will sit a couple of centimeters apart so that the midurethral point can be visualized. This helps to stabilize and elevate the midurethra.

To safely and efficiently develop a paraurethral passage, I perform a hydrodissection and hemostatic injection at the level of the midurethra using a control top 10-cc syringe with a 22-gauge needle. I find that dilute vasopressin saline solution affords better hemostasis than does a dilute lidocaine epinephrine solution, though I use dilute lidocaine if the sling is being done under local anesthesia.

The needle is inserted into a full thickness of skin, to a point shy of the urethra, and 10 cc is rapidly injected. The vaginal epithelium will appear blanched and will balloon out, like a white marble. The process basically lifts the vaginal skin away from the urethra itself, not only creating hemostasis but also providing a zone of safety to help avoid a urethral injury.

With a second syringe identical to the first, I inject 5 cc on each side of the midurethral point, aiming precisely at the underside of the pubic bone toward the ipsilateral shoulder. This creates a hydrodissected tunnel around each side of the midurethra. With a final syringe, I then inject 5 cc on each side suprapubically at my marked exit points.

With a #15 blade scalpel, I make two very small “poke” incisions transversely at the suprapubic sites. The suburethral incision is larger – just over a centimeter – and is made through a full thickness of skin under the area of hydrodissection, but not so deep as to injure the urethra. To finish development of the paraurethral passage, I pass standard Metzenbaum scissors through each hydrodissected tunnel until I feel the underside of the pubic bone, but no further.

For sling placement (after ensuring the bladder is completely empty), I lower the table such that my arm will be at a right angle to pass the sling while standing.

With my index finger underneath the pubic bone, the trocar tip, with the attached sling, is advanced with my thumb directly toward the ipsilateral shoulder just until it pops through the retropubic space. The depth of the trocar tip can be palpated with the index finger of the same hand, which is positioned just below the pelvic bone.

After the sling “pops” into the retropubic space, I remove my hand from the vagina and place it on the abdominal wall at the ipsilateral suprapubic poke site. In one smooth pass, I hug the pubic bone and advance the sling, again aiming directly and consistently at the shoulder. The trocar handle stays steady, never deviating in any direction. Cystoscopy is performed after the sling is placed on both sides to ensure bladder and urethral integrity.

For tensioning, I raise the table back up and, after reinserting the Foley catheter and a Sims retractor, I place my finger in the middle of the sling and pull the suprapubic ends of the sling up until my finger rests right under the urethra.

I then remove the vaginal clamps and use Metzenbaum scissors as a spacer between the sling and the urethra. With the scissors parallel to and right under the Foley catheter, at the same angle as the urethra, I tighten the sling and remove the plastic sheaths.

Dr. Sokol’s transobturator (TOT) approach

I most often use an outside-in sling. I utilize the same patient positioning and identify the midurethral point in the same way as with the retropubic approach.

On the thigh, I identify the adductor longus tendon as well as a little soft spot or depression just beneath the tendon and lateral to the descending ischial pubic ramus. With my thumb on the soft spot, I can actually grasp the adductor longus tendon between my thumb and index finger. This spot, which is also approximately at the level of the clitoris, marks the entry point for sling placement. It is the thinnest point between the groin and the vagina at the level of the midurethra.

I perform a similar hydrodissection under the urethra as I do in a retropubic procedure, though instead of injecting 5 cc’s to the underside of the pubic symphysis on each side, I instead inject toward the obturator internus muscles. I then inject my final syringe of dilute vasopressin saline solution at the groin poke incision sites, directed toward the projected trocar path, as opposed to suprapubically.

After the full-thickness vaginal incision is made with the scalpel, the dissection is performed sharply with Metzenbaum scissors and is more like the dissection done for cystocele repair than for a retropubic sling. Rather than a poke, the midurethral incision is long enough – about 1.5 cm – for me to reach a finger behind the obturator internus muscle after having sharply dissected the suburethral tissue and fascia. The angle of the dissection is more lateral than for a retropubic sling, toward the underside of the descending ischiopubic ramus and obturator internus muscle.

To place the sling, I have one hand with an index finger in the midurethral tunnel under the obturator internus muscle to protect the urethra. The thumb of that same hand is used to push the helical trocar straight through the thigh poke incision with the handle starting at a 35-degree angle from vertical. The trocar tip is pushed until it can no longer go straight and is ready to be tightly turned around the descending ischiopubic ramus with the opposite hand. A distinct pop can be felt as the trocar tip advances through the obturator membrane and muscles. As the tip is advanced, the angle of the trocar is rotated from 35 degrees to vertical, almost perpendicular to the floor. At this point, the tip of the trocar should be guided out of the midurethral tunnel against the opposite index finger.

I utilize the same technique for tensioning a TOT sling as I do the retropubic sling.

Dr. Rardin’s retropubic approach

I continue to use the original TVT sling with a 5-mm stainless steel, mechanically cut trocar and reusable handle. The newer slender needles may advance with less pressure, but I worry about them bending during passage. I feel more assured and comfortable using the older trocars.

I perform retropubic hydrodissection with a spinal needle using a top-down approach. With 40 cc of a very dilute solution of bupivacaine (Marcaine) with epinephrine on each side of the urethra, I create columns of hydrodissected space. Studies are inconsistent about the benefits of hydrodissection, but theoretically, it decreases the risk of bladder injury by pushing the bladder away from the pubic bone, creates effective hemostasis, and can provide analgesia that will be on board when the patient wakes up.

I bring the spinal needle down behind the pubic bone to the location of the urethral incision site, with my finger in the vagina, so I can feel the tip of the needle next to the urethra/Foley catheter. For each side, I will inject 20 cc of the solution in this location, and the other 20 cc as I withdraw the needle upward.

For trocar passage, some surgeons are taught to advance the trocar until a pop is felt, then drop the handle and push upward. I view the maneuver as a consistent, smooth arch; for every degree that I advance the trocar, I drop the handle slightly in order to maintain contact with the back of the pubic bone throughout the pass. I continuously and simultaneously drop the handle and advance the trocar. Contact with the back of the pubic bone is maintained with a slight pulling on the back end of the trocar handle, while the forward hand pushes the trocar upward.

The target that I visualize for a retropubic pass is the patient’s ipsilateral shoulder. A cadaver study showed that if you aim as far lateral as the patient’s outstretched elbow, you can enter the iliac vasculature (Obstet. Gynecol. 2003;101:933-6).

If the patient is draped such that I cannot see the ipsilateral shoulder, I ask the anesthesia team to show me. I have also identified and marked the suprapubic points about 2-3 cm from each other on either side of the midline just about the pubic symphysis, but I consider the broader anatomic picture and purposeful visualization toward the ipsilateral shoulder to be an essential part of safe technique. In general, it is safer to be more medial than more lateral for the needle passage.

I continue to use a rigid catheter guide to deflect the bladder neck while passing the needles.

Cystoscopy is performed after both needles are placed but not yet pulled through. I fill the bladder until the ureteral orifices appear flattened, which confirms that the bladder is under enough distension to preclude any mucosal wrinkles.

The technique I utilize for adjusting the tension of the TVT sling was taught to me by Dr. Peter L. Rosenblatt of Mt. Auburn Hospital in Cambridge, Mass. At the midline of the sling, I advance the sheaths just enough so that I can grasp a 2-3 mm “knuckle” of the midportion of the sling with a Babcock clamp. I then pull the sling ends until the Babcock comes into gentle contact with the suburethral tissue. The sheaths encasing the sling are then removed and the Babcock clamp is released to assure a tension-free deployment.

The amount of tape that is pinched with the Babcock – the size of the “knuckle” – determines the tension. For a patient with a more profound problem, such as intrinsic sphincter deficiency or a lack or urethral hypermobility, I will grasp a smaller knuckle.

These steps ensure that the midportion of the tape will not tighten or become deformed under tension. Rather than use a spacer, I like to protect the midportion of the tape and prevent it from being stretched. I find that the approach is reproducible and results in a reliable amount of space between the urethra and sling when the procedure is completed.

Dr. Rardin’s TOT approach

I employ an inside-out technique to the TOT procedure, and I utilize devices with segment of mesh that is shorter – only about 13 cm in length – than the original full-length mesh used in many TOT procedures. Once placed, the ends of the mesh penetrate the obturator membrane and obturator externus but not the adductor compartment of the thigh and groin.

In a study we presented last year at the annual meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons meeting, the shortened tape reduced postoperative groin pain, compared with full-length TOT tape without any reduction in subjective benefit. It appears that with shortened tape, we are anchoring the sling in tissues that provide critical support while avoiding the muscles that relate to the inner thigh/groin pain experienced by some patients. Effectiveness was not reduced, compared with full-length TOT slings.

These shortened slings are distinct from a single-incision sling, which is basically pushed into place. We still pass the needle all the way through a vaginal incision and out through the obturator foramen, and we pull the sling into place as we would any other TOT sling. The difference is that we’re not leaving any mesh in the groin.

I prefer an inside-out approach for two reasons: I always feel that I have more control over where a needle enters than where it exits, and precision is important with suburethral slings. Secondly, the dissection tunnel created for an inside-out pass is much smaller than the tunnel that must be dissected for an outside-in approach. In theory, less dissection means less devascularization, less denervation, and less opportunity for erosion.

Hydrodissection for TOT slings is more minimal and involves less fluid than does hydrodissection for retropubic slings, mainly because we do not want to anesthetize the obturator nerve. I pass the spinal needle from the outside in. At the start, prior to making any incisions, it is important to identify the arcus tendineus, a linear thickening of the superior fascia that is sometimes called the “white line.” This is where the sulcus is affixed to the sidewall. I will be sure to penetrate the sidewall at or above the level of the arcus.

With the TOT approach, the likelihood of bladder injury is so low that I usually drive the trocars all the way through prior to cystoscopy, as opposed to leaving the needles in place as I do with the retropubic approach.

Tensioning is achieved in the same manner, by using the Babcock clamp to avoid distortion of the critical part of the mesh while creating the space needed given the patient’s clinical scenario. It is worth remembering, at this point, that overall risks for retention appear to be lower for obturator slings, compared with retropubic slings.

I place most of my patients receiving retropubic slings in dorsal lithotomy position; but for obturator sling placement, I favor a few degrees into higher lithotomy because this pulls the obturator neurovascular bundle a little further out of the path of the needle.

Dr. Sokol reported that he owns stock in Pelvalon and is a clinical adviser to that company. He also is a national principal investigator for American Medical Systems and the recipient of research grants from Acell and several other companies. Dr. Rardin reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures. To view a video related to this article, go to SurgeryU at aagl.org/obgyn-news.

Midurethral slings – both retropubic and transobturator – have been extensively studied and have evolved to become standard therapies for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. The two approaches utilize different routes for sling delivery, but in many other respects, they are similar. Improvements in technique are continually being developed. In this column, Dr. Sokol and Dr. Rardin share key parts of their technique and give their pearls of advice for midurethral sling surgery.

Dr. Sokol’s retropubic approach

I use newer retropubic midurethral slings with smaller trocars that have evolved from first-generation tension-free vaginal tape (TVT) slings. The slings I prefer are placed in a bottom-up fashion, with curved needles passed from a small vaginal incision up through the retropubic space to exit through two suprapubic incisions.

I find it helpful to place patients in a high lithotomy position with the legs supported in candy cane stirrups rather than Allen-type stirrups; sling placement is a short procedure with minimal to no risk of neuropathy.

To precisely identify the midurethral point, I use a 16-FR Foley catheter. When the catheter balloon is filled with 10 mm of fluid and gently pulled back, the urethrovesical junction can be identified. Then, by looking at the urethral meatus relative to the bladder neck, I can mark the midpoint between the two.

The suprapubic exit points are marked at two finger-widths lateral to the midline, just above the pubic symphysis. For precise identification of these points, the Foley catheter may be pulled up exactly midline (with the collection bag detached), and the two finger-widths measured on either side. I also aim for the ipsilateral shoulder, imagining a straight line from the urethral meatus to the ipsilateral shoulder on each side. Together, these measurements and visual cues serve as a good safety check.

With two Allis clamps, the vaginal wall on either side of the midline is grasped transversely at the level of the midurethral mark. The clamps will sit a couple of centimeters apart so that the midurethral point can be visualized. This helps to stabilize and elevate the midurethra.

To safely and efficiently develop a paraurethral passage, I perform a hydrodissection and hemostatic injection at the level of the midurethra using a control top 10-cc syringe with a 22-gauge needle. I find that dilute vasopressin saline solution affords better hemostasis than does a dilute lidocaine epinephrine solution, though I use dilute lidocaine if the sling is being done under local anesthesia.

The needle is inserted into a full thickness of skin, to a point shy of the urethra, and 10 cc is rapidly injected. The vaginal epithelium will appear blanched and will balloon out, like a white marble. The process basically lifts the vaginal skin away from the urethra itself, not only creating hemostasis but also providing a zone of safety to help avoid a urethral injury.

With a second syringe identical to the first, I inject 5 cc on each side of the midurethral point, aiming precisely at the underside of the pubic bone toward the ipsilateral shoulder. This creates a hydrodissected tunnel around each side of the midurethra. With a final syringe, I then inject 5 cc on each side suprapubically at my marked exit points.

With a #15 blade scalpel, I make two very small “poke” incisions transversely at the suprapubic sites. The suburethral incision is larger – just over a centimeter – and is made through a full thickness of skin under the area of hydrodissection, but not so deep as to injure the urethra. To finish development of the paraurethral passage, I pass standard Metzenbaum scissors through each hydrodissected tunnel until I feel the underside of the pubic bone, but no further.

For sling placement (after ensuring the bladder is completely empty), I lower the table such that my arm will be at a right angle to pass the sling while standing.

With my index finger underneath the pubic bone, the trocar tip, with the attached sling, is advanced with my thumb directly toward the ipsilateral shoulder just until it pops through the retropubic space. The depth of the trocar tip can be palpated with the index finger of the same hand, which is positioned just below the pelvic bone.

After the sling “pops” into the retropubic space, I remove my hand from the vagina and place it on the abdominal wall at the ipsilateral suprapubic poke site. In one smooth pass, I hug the pubic bone and advance the sling, again aiming directly and consistently at the shoulder. The trocar handle stays steady, never deviating in any direction. Cystoscopy is performed after the sling is placed on both sides to ensure bladder and urethral integrity.

For tensioning, I raise the table back up and, after reinserting the Foley catheter and a Sims retractor, I place my finger in the middle of the sling and pull the suprapubic ends of the sling up until my finger rests right under the urethra.

I then remove the vaginal clamps and use Metzenbaum scissors as a spacer between the sling and the urethra. With the scissors parallel to and right under the Foley catheter, at the same angle as the urethra, I tighten the sling and remove the plastic sheaths.

Dr. Sokol’s transobturator (TOT) approach

I most often use an outside-in sling. I utilize the same patient positioning and identify the midurethral point in the same way as with the retropubic approach.

On the thigh, I identify the adductor longus tendon as well as a little soft spot or depression just beneath the tendon and lateral to the descending ischial pubic ramus. With my thumb on the soft spot, I can actually grasp the adductor longus tendon between my thumb and index finger. This spot, which is also approximately at the level of the clitoris, marks the entry point for sling placement. It is the thinnest point between the groin and the vagina at the level of the midurethra.

I perform a similar hydrodissection under the urethra as I do in a retropubic procedure, though instead of injecting 5 cc’s to the underside of the pubic symphysis on each side, I instead inject toward the obturator internus muscles. I then inject my final syringe of dilute vasopressin saline solution at the groin poke incision sites, directed toward the projected trocar path, as opposed to suprapubically.

After the full-thickness vaginal incision is made with the scalpel, the dissection is performed sharply with Metzenbaum scissors and is more like the dissection done for cystocele repair than for a retropubic sling. Rather than a poke, the midurethral incision is long enough – about 1.5 cm – for me to reach a finger behind the obturator internus muscle after having sharply dissected the suburethral tissue and fascia. The angle of the dissection is more lateral than for a retropubic sling, toward the underside of the descending ischiopubic ramus and obturator internus muscle.

To place the sling, I have one hand with an index finger in the midurethral tunnel under the obturator internus muscle to protect the urethra. The thumb of that same hand is used to push the helical trocar straight through the thigh poke incision with the handle starting at a 35-degree angle from vertical. The trocar tip is pushed until it can no longer go straight and is ready to be tightly turned around the descending ischiopubic ramus with the opposite hand. A distinct pop can be felt as the trocar tip advances through the obturator membrane and muscles. As the tip is advanced, the angle of the trocar is rotated from 35 degrees to vertical, almost perpendicular to the floor. At this point, the tip of the trocar should be guided out of the midurethral tunnel against the opposite index finger.

I utilize the same technique for tensioning a TOT sling as I do the retropubic sling.

Dr. Rardin’s retropubic approach

I continue to use the original TVT sling with a 5-mm stainless steel, mechanically cut trocar and reusable handle. The newer slender needles may advance with less pressure, but I worry about them bending during passage. I feel more assured and comfortable using the older trocars.

I perform retropubic hydrodissection with a spinal needle using a top-down approach. With 40 cc of a very dilute solution of bupivacaine (Marcaine) with epinephrine on each side of the urethra, I create columns of hydrodissected space. Studies are inconsistent about the benefits of hydrodissection, but theoretically, it decreases the risk of bladder injury by pushing the bladder away from the pubic bone, creates effective hemostasis, and can provide analgesia that will be on board when the patient wakes up.