User login

Unrecognized placenta accreta spectrum: Intraoperative management

CASE Concerning finding on repeat CD

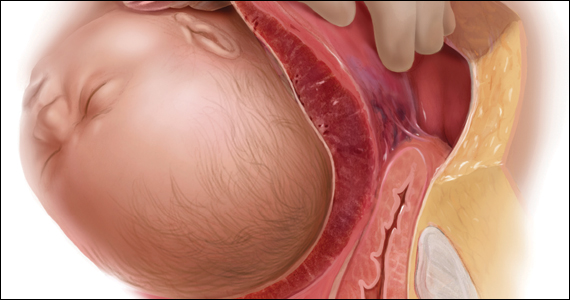

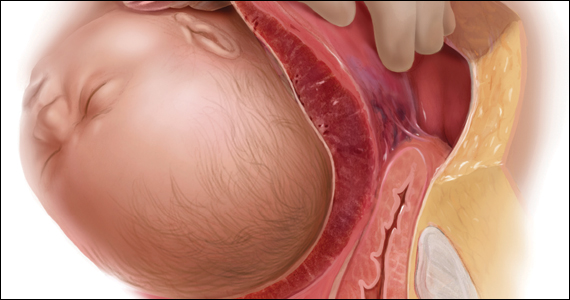

A 30-year-old woman with a history of 1 prior cesarean delivery (CD) presents to labor and delivery at 38 weeks of gestation with symptoms of mild cramping. Her prenatal care was uncomplicated. The covering team made a decision to proceed with a repeat CD. A Pfannenstiel incision is made to enter the abdomen, and inspection of the lower uterine segment is concerning for a placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) (FIGURE).

What would be your next steps?

Placenta accreta spectrum describes the range of disorders of placental implantation, including placenta accreta, increta, and percreta. PAS is a significant cause of severe maternal morbidity and mortality, primarily due to massive hemorrhage at the time of delivery. The incidence of PAS continues to rise along with the CD rate. The authors of a recent meta-analysis reported a pooled prevalence rate of 1 in 588 women.1 Notably, in women with PAS, the rate of hysterectomy is 52.2%, and the transfusion-dependent hemorrhage rate is 46.9%.1

Ideally, PAS should be diagnosed or at least suspected antenatally during prenatal ultrasonography, leading to delivery planning by a multidisciplinary team.2 The presence of a multidisciplinary team—in addition to the primary obstetric and surgical teams—composed of experienced anesthesiologists, a blood bank able to respond to massive transfusion needs, critical care specialists, and interventional radiologists is associated with improved outcomes.3-5

Occasionally, a patient is found to have an advanced PAS (increta or percreta) at the time of delivery. In these situations, it is paramount that the appropriate resources be assembled as expeditiously as possible to optimize maternal outcomes. Surgical management can be challenging even for experienced pelvic surgeons, and appropriate resuscitation cannot be provided by a single anesthesiologist working alone. A cavalier attitude of proceeding with the delivery “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences, including maternal death.

In this article, we review the important steps to take when faced with the unexpected situation of a PAS at the time of CD.

Continue to: Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team...

Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team

Once the diagnosis of an advanced PAS is suspected, the first step is to stop and request the presence of your institution’s multidisciplinary surgical team. This team typically includes a maternal-fetal specialist or, if not available, an experienced obstetrician, and an expert pelvic surgeon, which varies by institution (gynecologic oncologist, trauma surgeon, urologist, urogynecologist, vascular surgeon). An interventional radiology team is an additional useful resource that can assist with the control of pelvic hemorrhage using embolization techniques.

In our opinion, it is not appropriate to have a surgical backup team available only as needed at a certain distance from the hospital or even in the building. Because of the acuity and magnitude of bleeding that can occur in a short time, the most appropriate approach is to have your surgical team scrubbed and ready to assist or take over the procedure immediately if indicated.

Additional support staff also may be required. A single circulating nurse may not be sufficient, and available nursing staff may need to be called. The surgical technician scrubbed on the case may be familiar only with uncomplicated CDs and can be overwhelmed during a PAS case. Having a more experienced surgical technologist can optimize the availability of the appropriate instruments for the surgical team.

If a multidisciplinary surgical team with PAS management expertise is not available at your institution and the patient is stable, it is appropriate to consider transferring her to the nearest center that can meet the high-risk needs of this situation.6

Prepare for resuscitation

While you are calling your multidisciplinary team members, implement plans for resuscitation by notifying the anesthesiologist about the PAS findings. This will allow the gathering of needed resources that may include calling on additional anesthesiologists with experience in high-risk obstetrics, trauma, or critical care.

Placing large-bore intravenous lines or a central line to allow rapid transfusion is essential. Strongly consider inserting an arterial line for hemodynamic monitoring and intraoperative blood draws to monitor blood loss, blood gases, electrolytes, and coagulation parameters, which can guide resuscitative efforts and replacement therapies.

Simultaneously, inform the blood bank to prepare blood and blood products for possible activation of a massive transfusion protocol. It is imperative to have the products available in the operating room (OR) prior to proceeding with the surgery. Our current practice is to have 10 units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma available in the OR for all our prenatally diagnosed electively planned PAS cases.

Optimize exposure of the surgical field

Appropriate exposure of the surgical field is essential and should include exposure of the uterine fundus and the pelvic sidewalls. The uterine incision should avoid the placenta; typically it is placed at the level of the uterine fundus. Exposure of the pelvic sidewalls is needed to open the retroperitoneum and identify the ureter and the iliac vessels.

Vertical extension of the fascial incision probably will be needed to achieve appropriate exposure. Although at times this can be done without a concomitant vertical skin incision, often an inverted T incision is required. Be mindful that PAS is a life-threatening condition and that aesthetics are not a priority. After extending the fascial incision, adequate exposure can be achieved with any of the commonly used retractors or wound protectors (depending on institutional availability and surgeon preference) or by the surgical assistants using body wall retractors.

We routinely place the patient in lithotomy position. This allows us to monitor for vaginal bleeding (often a site of unrecognized massive hemorrhage) during the surgery, facilitate retrograde bladder filling, and provide a vaginal access to the pelvis. In addition, the lithotomy position allows for cystoscopy and placement of ureteral stents, which can be performed before starting the surgery to help prevent urinary tract injuries or at the end of the procedure in case one is suspected.7

Continue to: Performing the hysterectomy...

Performing the hysterectomy

A complete review of all surgical techniques for managing PAS is beyond the scope of this article. However, we briefly cover important procedural steps and offer suggestions on how to minimize the risk of bleeding.

In our experience. The areas with the highest risk of massive bleeding that can be difficult to control include the pelvic sidewall when there is lateral extension of the PAS, the vesicouterine space, and placenta previa vaginally. Be mindful of these areas at risk and have a plan in place in case of bleeding.

Uterine incision

Avoid the placenta when making the uterine incision, which is typically done in the fundal part of the uterus. Cut and tie the cord and return it to the uterine cavity. Close the incision in a single layer. Use of a surgical stapler can be used for the hysterotomy and can decrease the amount of blood loss.8

Superior attachments of the uterus

The superior attachments of the uterus include the round ligament, the utero-ovarian ligament, and the fallopian tubes. With meticulous dissection, develop an avascular space underneath these structures and, in turn, individually divide and suture ligate; this is typically achieved with minimal blood loss.

In addition, isolate the engorged veins of the broad ligament and divide them in a similar fashion.

In our experience. Use of a vessel-sealing device can facilitate division of all the former structures. Simply excise the fallopian tubes with the vessel-sealing device either at this time or after the uterus is removed.

Pelvic sidewall

Once the superior attachments of the uterus have been divided, the next step involves exposing the pelvic sidewall structures, that is, the ureter and the pelvic vessels. Expose the ureter from the pelvic brim to the level of the uterine artery. The hypogastric artery is exposed as well in this process and the pararectal space developed.

When the PAS has extended laterally, perform stepwise division of the lateral attachments of the placenta to the pelvic sidewall using a combination of electrocautery, hemoclips, and the vessel-sealing device. In laterally extended PAS cases, it often is necessary to divide the uterine artery either at its origin or at the level of the ureter to allow for the completion of the separation of the placenta from the pelvic sidewall.

In our experience. During this lateral dissection, significant bleeding may be encountered from the neovascular network that has developed in the pelvic sidewall. The bleeding may be diffuse and difficult to control with the methods described above. In this situation, we have found that placing hemostatic agents in this area and packing the sidewall with laparotomy pads can achieve hemostasis in most cases, thus allowing the surgery to proceed.

1. Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team. If required resources are not available at your institution and the patient is stable, consider transferring her to the nearest center of expertise

2. Prepare for resuscitation: Have blood products available in the operating room and optimize IV access and arterial line

3. Optimize exposure of the surgical field: place in lithotomy position, extend fascial incision, perform hysterotomy to avoid the placenta, and expose pelvic sidewall and ureters

4. Be mindful of likely sources of massive bleeding: pelvic sidewall, bladder/vesicouterine space, and/or placenta previa vaginally

5. Proceed with meticulous dissection to minimize the risk of hemorrhage, retrograde fill the bladder, be mindful of the utility of packing

6. Be prepared to move to an expeditious hysterectomy in case of massive bleeding

Continue to: Bladder dissection...

Bladder dissection

The next critical part of the surgery involves developing the vesicovaginal space to mobilize the bladder. Prior to initiating the bladder dissection, we routinely retrograde fill the bladder with 180 to 240 mL of saline mixed with methylene blue. This delineates the superior edge of the bladder and indicates the appropriate level to start the dissection. Then slowly develop the vesicouterine space using a combination of electrocautery and a vessel-sealing device until the bladder is mobilized to the level of the anterior vaginal wall. Many vascular connections are encountered at that level, and meticulous dissection and patience is required to systematically divide them all.

In our experience. This part of the surgery presents several challenges. The bladder wall may be invaded by the placenta, which will lead to an increased risk of bleeding and cystotomy during the dissection. In these cases, it might be preferable to create an intentional cystotomy to guide the dissection; at times, a limited excision of the involved bladder wall may be required. In other cases, even in the absence of bladder wall invasion, the bladder may be densely adherent to the uterine wall (usually due to a history of prior CDs), and bladder mobilization may be complicated by bleeding from the neovascular network that has developed between the placenta and bladder.

Uterine arteries and cervix

Once the placenta is separated from its lateral attachments and the bladder is mobilized, the next steps are similar to those in a standard abdominal hysterectomy. If the uterine arteries were not yet divided during the pelvic sidewall dissection, they are clamped, divided, and suture ligated at the level of the uterine isthmus. The decision whether to perform a supracervical or total hysterectomy depends on the level of cervical involvement by the placenta, surgeon preference, anatomic distortion, and bleeding from the cervix and anterior vaginal wall.

Responding to massive bleeding

Not uncommonly, and despite the best efforts to avoid it, massive bleeding may develop from the areas at risk as noted above. If the bleeding is significant and originates from multiple areas (including vaginal bleeding from placenta previa), we recommend proceeding with an expeditious hysterectomy to remove the specimen, and then reassess the pelvic field for hemostatic control and any organ damage that may have occurred.

The challenge of PAS

Surgical management of PAS is one the most challenging procedures in pelvic surgery. Successful outcomes require a multidisciplinary team approach and an experienced team dedicated to the management of this condition.9 By contrast, proceeding “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences in terms of maternal morbidity and mortality. ●

- Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Gronbeck L, et al. Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:208-218.

- Society of Gynecologic Oncology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:B2-B16.

- Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):331-337.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:218.e1-9.

- Collins SL, Alemdar B, van Beekhuizen HJ, et al; International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of abnormally invasive placenta: recommendations from the International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:511-526.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:561-568.

- Tam Tam KB, Dozier J, Martin JN Jr. Approaches to reduce urinary tract injury during management of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:329-334.

- Belfort MA, Shamshiraz AA, Fox K. Minimizing blood loss at cesarean-hysterectomy for placenta previa percreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:78.e1-78.e2.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Erfani H, et al. Multidisciplinary team learning in the management of the morbidly adherent placenta: outcome improvements over time. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:612.e1-612.e5.

CASE Concerning finding on repeat CD

A 30-year-old woman with a history of 1 prior cesarean delivery (CD) presents to labor and delivery at 38 weeks of gestation with symptoms of mild cramping. Her prenatal care was uncomplicated. The covering team made a decision to proceed with a repeat CD. A Pfannenstiel incision is made to enter the abdomen, and inspection of the lower uterine segment is concerning for a placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) (FIGURE).

What would be your next steps?

Placenta accreta spectrum describes the range of disorders of placental implantation, including placenta accreta, increta, and percreta. PAS is a significant cause of severe maternal morbidity and mortality, primarily due to massive hemorrhage at the time of delivery. The incidence of PAS continues to rise along with the CD rate. The authors of a recent meta-analysis reported a pooled prevalence rate of 1 in 588 women.1 Notably, in women with PAS, the rate of hysterectomy is 52.2%, and the transfusion-dependent hemorrhage rate is 46.9%.1

Ideally, PAS should be diagnosed or at least suspected antenatally during prenatal ultrasonography, leading to delivery planning by a multidisciplinary team.2 The presence of a multidisciplinary team—in addition to the primary obstetric and surgical teams—composed of experienced anesthesiologists, a blood bank able to respond to massive transfusion needs, critical care specialists, and interventional radiologists is associated with improved outcomes.3-5

Occasionally, a patient is found to have an advanced PAS (increta or percreta) at the time of delivery. In these situations, it is paramount that the appropriate resources be assembled as expeditiously as possible to optimize maternal outcomes. Surgical management can be challenging even for experienced pelvic surgeons, and appropriate resuscitation cannot be provided by a single anesthesiologist working alone. A cavalier attitude of proceeding with the delivery “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences, including maternal death.

In this article, we review the important steps to take when faced with the unexpected situation of a PAS at the time of CD.

Continue to: Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team...

Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team

Once the diagnosis of an advanced PAS is suspected, the first step is to stop and request the presence of your institution’s multidisciplinary surgical team. This team typically includes a maternal-fetal specialist or, if not available, an experienced obstetrician, and an expert pelvic surgeon, which varies by institution (gynecologic oncologist, trauma surgeon, urologist, urogynecologist, vascular surgeon). An interventional radiology team is an additional useful resource that can assist with the control of pelvic hemorrhage using embolization techniques.

In our opinion, it is not appropriate to have a surgical backup team available only as needed at a certain distance from the hospital or even in the building. Because of the acuity and magnitude of bleeding that can occur in a short time, the most appropriate approach is to have your surgical team scrubbed and ready to assist or take over the procedure immediately if indicated.

Additional support staff also may be required. A single circulating nurse may not be sufficient, and available nursing staff may need to be called. The surgical technician scrubbed on the case may be familiar only with uncomplicated CDs and can be overwhelmed during a PAS case. Having a more experienced surgical technologist can optimize the availability of the appropriate instruments for the surgical team.

If a multidisciplinary surgical team with PAS management expertise is not available at your institution and the patient is stable, it is appropriate to consider transferring her to the nearest center that can meet the high-risk needs of this situation.6

Prepare for resuscitation

While you are calling your multidisciplinary team members, implement plans for resuscitation by notifying the anesthesiologist about the PAS findings. This will allow the gathering of needed resources that may include calling on additional anesthesiologists with experience in high-risk obstetrics, trauma, or critical care.

Placing large-bore intravenous lines or a central line to allow rapid transfusion is essential. Strongly consider inserting an arterial line for hemodynamic monitoring and intraoperative blood draws to monitor blood loss, blood gases, electrolytes, and coagulation parameters, which can guide resuscitative efforts and replacement therapies.

Simultaneously, inform the blood bank to prepare blood and blood products for possible activation of a massive transfusion protocol. It is imperative to have the products available in the operating room (OR) prior to proceeding with the surgery. Our current practice is to have 10 units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma available in the OR for all our prenatally diagnosed electively planned PAS cases.

Optimize exposure of the surgical field

Appropriate exposure of the surgical field is essential and should include exposure of the uterine fundus and the pelvic sidewalls. The uterine incision should avoid the placenta; typically it is placed at the level of the uterine fundus. Exposure of the pelvic sidewalls is needed to open the retroperitoneum and identify the ureter and the iliac vessels.

Vertical extension of the fascial incision probably will be needed to achieve appropriate exposure. Although at times this can be done without a concomitant vertical skin incision, often an inverted T incision is required. Be mindful that PAS is a life-threatening condition and that aesthetics are not a priority. After extending the fascial incision, adequate exposure can be achieved with any of the commonly used retractors or wound protectors (depending on institutional availability and surgeon preference) or by the surgical assistants using body wall retractors.

We routinely place the patient in lithotomy position. This allows us to monitor for vaginal bleeding (often a site of unrecognized massive hemorrhage) during the surgery, facilitate retrograde bladder filling, and provide a vaginal access to the pelvis. In addition, the lithotomy position allows for cystoscopy and placement of ureteral stents, which can be performed before starting the surgery to help prevent urinary tract injuries or at the end of the procedure in case one is suspected.7

Continue to: Performing the hysterectomy...

Performing the hysterectomy

A complete review of all surgical techniques for managing PAS is beyond the scope of this article. However, we briefly cover important procedural steps and offer suggestions on how to minimize the risk of bleeding.

In our experience. The areas with the highest risk of massive bleeding that can be difficult to control include the pelvic sidewall when there is lateral extension of the PAS, the vesicouterine space, and placenta previa vaginally. Be mindful of these areas at risk and have a plan in place in case of bleeding.

Uterine incision

Avoid the placenta when making the uterine incision, which is typically done in the fundal part of the uterus. Cut and tie the cord and return it to the uterine cavity. Close the incision in a single layer. Use of a surgical stapler can be used for the hysterotomy and can decrease the amount of blood loss.8

Superior attachments of the uterus

The superior attachments of the uterus include the round ligament, the utero-ovarian ligament, and the fallopian tubes. With meticulous dissection, develop an avascular space underneath these structures and, in turn, individually divide and suture ligate; this is typically achieved with minimal blood loss.

In addition, isolate the engorged veins of the broad ligament and divide them in a similar fashion.

In our experience. Use of a vessel-sealing device can facilitate division of all the former structures. Simply excise the fallopian tubes with the vessel-sealing device either at this time or after the uterus is removed.

Pelvic sidewall

Once the superior attachments of the uterus have been divided, the next step involves exposing the pelvic sidewall structures, that is, the ureter and the pelvic vessels. Expose the ureter from the pelvic brim to the level of the uterine artery. The hypogastric artery is exposed as well in this process and the pararectal space developed.

When the PAS has extended laterally, perform stepwise division of the lateral attachments of the placenta to the pelvic sidewall using a combination of electrocautery, hemoclips, and the vessel-sealing device. In laterally extended PAS cases, it often is necessary to divide the uterine artery either at its origin or at the level of the ureter to allow for the completion of the separation of the placenta from the pelvic sidewall.

In our experience. During this lateral dissection, significant bleeding may be encountered from the neovascular network that has developed in the pelvic sidewall. The bleeding may be diffuse and difficult to control with the methods described above. In this situation, we have found that placing hemostatic agents in this area and packing the sidewall with laparotomy pads can achieve hemostasis in most cases, thus allowing the surgery to proceed.

1. Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team. If required resources are not available at your institution and the patient is stable, consider transferring her to the nearest center of expertise

2. Prepare for resuscitation: Have blood products available in the operating room and optimize IV access and arterial line

3. Optimize exposure of the surgical field: place in lithotomy position, extend fascial incision, perform hysterotomy to avoid the placenta, and expose pelvic sidewall and ureters

4. Be mindful of likely sources of massive bleeding: pelvic sidewall, bladder/vesicouterine space, and/or placenta previa vaginally

5. Proceed with meticulous dissection to minimize the risk of hemorrhage, retrograde fill the bladder, be mindful of the utility of packing

6. Be prepared to move to an expeditious hysterectomy in case of massive bleeding

Continue to: Bladder dissection...

Bladder dissection

The next critical part of the surgery involves developing the vesicovaginal space to mobilize the bladder. Prior to initiating the bladder dissection, we routinely retrograde fill the bladder with 180 to 240 mL of saline mixed with methylene blue. This delineates the superior edge of the bladder and indicates the appropriate level to start the dissection. Then slowly develop the vesicouterine space using a combination of electrocautery and a vessel-sealing device until the bladder is mobilized to the level of the anterior vaginal wall. Many vascular connections are encountered at that level, and meticulous dissection and patience is required to systematically divide them all.

In our experience. This part of the surgery presents several challenges. The bladder wall may be invaded by the placenta, which will lead to an increased risk of bleeding and cystotomy during the dissection. In these cases, it might be preferable to create an intentional cystotomy to guide the dissection; at times, a limited excision of the involved bladder wall may be required. In other cases, even in the absence of bladder wall invasion, the bladder may be densely adherent to the uterine wall (usually due to a history of prior CDs), and bladder mobilization may be complicated by bleeding from the neovascular network that has developed between the placenta and bladder.

Uterine arteries and cervix

Once the placenta is separated from its lateral attachments and the bladder is mobilized, the next steps are similar to those in a standard abdominal hysterectomy. If the uterine arteries were not yet divided during the pelvic sidewall dissection, they are clamped, divided, and suture ligated at the level of the uterine isthmus. The decision whether to perform a supracervical or total hysterectomy depends on the level of cervical involvement by the placenta, surgeon preference, anatomic distortion, and bleeding from the cervix and anterior vaginal wall.

Responding to massive bleeding

Not uncommonly, and despite the best efforts to avoid it, massive bleeding may develop from the areas at risk as noted above. If the bleeding is significant and originates from multiple areas (including vaginal bleeding from placenta previa), we recommend proceeding with an expeditious hysterectomy to remove the specimen, and then reassess the pelvic field for hemostatic control and any organ damage that may have occurred.

The challenge of PAS

Surgical management of PAS is one the most challenging procedures in pelvic surgery. Successful outcomes require a multidisciplinary team approach and an experienced team dedicated to the management of this condition.9 By contrast, proceeding “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences in terms of maternal morbidity and mortality. ●

CASE Concerning finding on repeat CD

A 30-year-old woman with a history of 1 prior cesarean delivery (CD) presents to labor and delivery at 38 weeks of gestation with symptoms of mild cramping. Her prenatal care was uncomplicated. The covering team made a decision to proceed with a repeat CD. A Pfannenstiel incision is made to enter the abdomen, and inspection of the lower uterine segment is concerning for a placenta accreta spectrum (PAS) (FIGURE).

What would be your next steps?

Placenta accreta spectrum describes the range of disorders of placental implantation, including placenta accreta, increta, and percreta. PAS is a significant cause of severe maternal morbidity and mortality, primarily due to massive hemorrhage at the time of delivery. The incidence of PAS continues to rise along with the CD rate. The authors of a recent meta-analysis reported a pooled prevalence rate of 1 in 588 women.1 Notably, in women with PAS, the rate of hysterectomy is 52.2%, and the transfusion-dependent hemorrhage rate is 46.9%.1

Ideally, PAS should be diagnosed or at least suspected antenatally during prenatal ultrasonography, leading to delivery planning by a multidisciplinary team.2 The presence of a multidisciplinary team—in addition to the primary obstetric and surgical teams—composed of experienced anesthesiologists, a blood bank able to respond to massive transfusion needs, critical care specialists, and interventional radiologists is associated with improved outcomes.3-5

Occasionally, a patient is found to have an advanced PAS (increta or percreta) at the time of delivery. In these situations, it is paramount that the appropriate resources be assembled as expeditiously as possible to optimize maternal outcomes. Surgical management can be challenging even for experienced pelvic surgeons, and appropriate resuscitation cannot be provided by a single anesthesiologist working alone. A cavalier attitude of proceeding with the delivery “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences, including maternal death.

In this article, we review the important steps to take when faced with the unexpected situation of a PAS at the time of CD.

Continue to: Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team...

Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team

Once the diagnosis of an advanced PAS is suspected, the first step is to stop and request the presence of your institution’s multidisciplinary surgical team. This team typically includes a maternal-fetal specialist or, if not available, an experienced obstetrician, and an expert pelvic surgeon, which varies by institution (gynecologic oncologist, trauma surgeon, urologist, urogynecologist, vascular surgeon). An interventional radiology team is an additional useful resource that can assist with the control of pelvic hemorrhage using embolization techniques.

In our opinion, it is not appropriate to have a surgical backup team available only as needed at a certain distance from the hospital or even in the building. Because of the acuity and magnitude of bleeding that can occur in a short time, the most appropriate approach is to have your surgical team scrubbed and ready to assist or take over the procedure immediately if indicated.

Additional support staff also may be required. A single circulating nurse may not be sufficient, and available nursing staff may need to be called. The surgical technician scrubbed on the case may be familiar only with uncomplicated CDs and can be overwhelmed during a PAS case. Having a more experienced surgical technologist can optimize the availability of the appropriate instruments for the surgical team.

If a multidisciplinary surgical team with PAS management expertise is not available at your institution and the patient is stable, it is appropriate to consider transferring her to the nearest center that can meet the high-risk needs of this situation.6

Prepare for resuscitation

While you are calling your multidisciplinary team members, implement plans for resuscitation by notifying the anesthesiologist about the PAS findings. This will allow the gathering of needed resources that may include calling on additional anesthesiologists with experience in high-risk obstetrics, trauma, or critical care.

Placing large-bore intravenous lines or a central line to allow rapid transfusion is essential. Strongly consider inserting an arterial line for hemodynamic monitoring and intraoperative blood draws to monitor blood loss, blood gases, electrolytes, and coagulation parameters, which can guide resuscitative efforts and replacement therapies.

Simultaneously, inform the blood bank to prepare blood and blood products for possible activation of a massive transfusion protocol. It is imperative to have the products available in the operating room (OR) prior to proceeding with the surgery. Our current practice is to have 10 units of packed red blood cells and fresh frozen plasma available in the OR for all our prenatally diagnosed electively planned PAS cases.

Optimize exposure of the surgical field

Appropriate exposure of the surgical field is essential and should include exposure of the uterine fundus and the pelvic sidewalls. The uterine incision should avoid the placenta; typically it is placed at the level of the uterine fundus. Exposure of the pelvic sidewalls is needed to open the retroperitoneum and identify the ureter and the iliac vessels.

Vertical extension of the fascial incision probably will be needed to achieve appropriate exposure. Although at times this can be done without a concomitant vertical skin incision, often an inverted T incision is required. Be mindful that PAS is a life-threatening condition and that aesthetics are not a priority. After extending the fascial incision, adequate exposure can be achieved with any of the commonly used retractors or wound protectors (depending on institutional availability and surgeon preference) or by the surgical assistants using body wall retractors.

We routinely place the patient in lithotomy position. This allows us to monitor for vaginal bleeding (often a site of unrecognized massive hemorrhage) during the surgery, facilitate retrograde bladder filling, and provide a vaginal access to the pelvis. In addition, the lithotomy position allows for cystoscopy and placement of ureteral stents, which can be performed before starting the surgery to help prevent urinary tract injuries or at the end of the procedure in case one is suspected.7

Continue to: Performing the hysterectomy...

Performing the hysterectomy

A complete review of all surgical techniques for managing PAS is beyond the scope of this article. However, we briefly cover important procedural steps and offer suggestions on how to minimize the risk of bleeding.

In our experience. The areas with the highest risk of massive bleeding that can be difficult to control include the pelvic sidewall when there is lateral extension of the PAS, the vesicouterine space, and placenta previa vaginally. Be mindful of these areas at risk and have a plan in place in case of bleeding.

Uterine incision

Avoid the placenta when making the uterine incision, which is typically done in the fundal part of the uterus. Cut and tie the cord and return it to the uterine cavity. Close the incision in a single layer. Use of a surgical stapler can be used for the hysterotomy and can decrease the amount of blood loss.8

Superior attachments of the uterus

The superior attachments of the uterus include the round ligament, the utero-ovarian ligament, and the fallopian tubes. With meticulous dissection, develop an avascular space underneath these structures and, in turn, individually divide and suture ligate; this is typically achieved with minimal blood loss.

In addition, isolate the engorged veins of the broad ligament and divide them in a similar fashion.

In our experience. Use of a vessel-sealing device can facilitate division of all the former structures. Simply excise the fallopian tubes with the vessel-sealing device either at this time or after the uterus is removed.

Pelvic sidewall

Once the superior attachments of the uterus have been divided, the next step involves exposing the pelvic sidewall structures, that is, the ureter and the pelvic vessels. Expose the ureter from the pelvic brim to the level of the uterine artery. The hypogastric artery is exposed as well in this process and the pararectal space developed.

When the PAS has extended laterally, perform stepwise division of the lateral attachments of the placenta to the pelvic sidewall using a combination of electrocautery, hemoclips, and the vessel-sealing device. In laterally extended PAS cases, it often is necessary to divide the uterine artery either at its origin or at the level of the ureter to allow for the completion of the separation of the placenta from the pelvic sidewall.

In our experience. During this lateral dissection, significant bleeding may be encountered from the neovascular network that has developed in the pelvic sidewall. The bleeding may be diffuse and difficult to control with the methods described above. In this situation, we have found that placing hemostatic agents in this area and packing the sidewall with laparotomy pads can achieve hemostasis in most cases, thus allowing the surgery to proceed.

1. Stop and collect your multidisciplinary team. If required resources are not available at your institution and the patient is stable, consider transferring her to the nearest center of expertise

2. Prepare for resuscitation: Have blood products available in the operating room and optimize IV access and arterial line

3. Optimize exposure of the surgical field: place in lithotomy position, extend fascial incision, perform hysterotomy to avoid the placenta, and expose pelvic sidewall and ureters

4. Be mindful of likely sources of massive bleeding: pelvic sidewall, bladder/vesicouterine space, and/or placenta previa vaginally

5. Proceed with meticulous dissection to minimize the risk of hemorrhage, retrograde fill the bladder, be mindful of the utility of packing

6. Be prepared to move to an expeditious hysterectomy in case of massive bleeding

Continue to: Bladder dissection...

Bladder dissection

The next critical part of the surgery involves developing the vesicovaginal space to mobilize the bladder. Prior to initiating the bladder dissection, we routinely retrograde fill the bladder with 180 to 240 mL of saline mixed with methylene blue. This delineates the superior edge of the bladder and indicates the appropriate level to start the dissection. Then slowly develop the vesicouterine space using a combination of electrocautery and a vessel-sealing device until the bladder is mobilized to the level of the anterior vaginal wall. Many vascular connections are encountered at that level, and meticulous dissection and patience is required to systematically divide them all.

In our experience. This part of the surgery presents several challenges. The bladder wall may be invaded by the placenta, which will lead to an increased risk of bleeding and cystotomy during the dissection. In these cases, it might be preferable to create an intentional cystotomy to guide the dissection; at times, a limited excision of the involved bladder wall may be required. In other cases, even in the absence of bladder wall invasion, the bladder may be densely adherent to the uterine wall (usually due to a history of prior CDs), and bladder mobilization may be complicated by bleeding from the neovascular network that has developed between the placenta and bladder.

Uterine arteries and cervix

Once the placenta is separated from its lateral attachments and the bladder is mobilized, the next steps are similar to those in a standard abdominal hysterectomy. If the uterine arteries were not yet divided during the pelvic sidewall dissection, they are clamped, divided, and suture ligated at the level of the uterine isthmus. The decision whether to perform a supracervical or total hysterectomy depends on the level of cervical involvement by the placenta, surgeon preference, anatomic distortion, and bleeding from the cervix and anterior vaginal wall.

Responding to massive bleeding

Not uncommonly, and despite the best efforts to avoid it, massive bleeding may develop from the areas at risk as noted above. If the bleeding is significant and originates from multiple areas (including vaginal bleeding from placenta previa), we recommend proceeding with an expeditious hysterectomy to remove the specimen, and then reassess the pelvic field for hemostatic control and any organ damage that may have occurred.

The challenge of PAS

Surgical management of PAS is one the most challenging procedures in pelvic surgery. Successful outcomes require a multidisciplinary team approach and an experienced team dedicated to the management of this condition.9 By contrast, proceeding “as usual” in the face of an unexpected PAS situation can lead to disastrous consequences in terms of maternal morbidity and mortality. ●

- Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Gronbeck L, et al. Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:208-218.

- Society of Gynecologic Oncology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:B2-B16.

- Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):331-337.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:218.e1-9.

- Collins SL, Alemdar B, van Beekhuizen HJ, et al; International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of abnormally invasive placenta: recommendations from the International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:511-526.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:561-568.

- Tam Tam KB, Dozier J, Martin JN Jr. Approaches to reduce urinary tract injury during management of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:329-334.

- Belfort MA, Shamshiraz AA, Fox K. Minimizing blood loss at cesarean-hysterectomy for placenta previa percreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:78.e1-78.e2.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Erfani H, et al. Multidisciplinary team learning in the management of the morbidly adherent placenta: outcome improvements over time. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:612.e1-612.e5.

- Jauniaux E, Bunce C, Gronbeck L, et al. Prevalence and main outcomes of placenta accreta spectrum: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;221:208-218.

- Society of Gynecologic Oncology, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine, et al. Placenta accreta spectrum. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219:B2-B16.

- Eller AG, Bennett MA, Sharshiner M, et al. Maternal morbidity in cases of placenta accreta managed by a multidisciplinary care team compared with standard obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117(2 pt 1):331-337.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Salmanian B, et al. Maternal morbidity in patients with morbidly adherent placenta treated with and without a standardized multidisciplinary approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:218.e1-9.

- Collins SL, Alemdar B, van Beekhuizen HJ, et al; International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Evidence-based guidelines for the management of abnormally invasive placenta: recommendations from the International Society for Abnormally Invasive Placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2019;220:511-526.

- Silver RM, Fox KA, Barton JR, et al. Center of excellence for placenta accreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:561-568.

- Tam Tam KB, Dozier J, Martin JN Jr. Approaches to reduce urinary tract injury during management of placenta accreta, increta, and percreta: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2012;25:329-334.

- Belfort MA, Shamshiraz AA, Fox K. Minimizing blood loss at cesarean-hysterectomy for placenta previa percreta. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:78.e1-78.e2.

- Shamshirsaz AA, Fox KA, Erfani H, et al. Multidisciplinary team learning in the management of the morbidly adherent placenta: outcome improvements over time. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2017;216:612.e1-612.e5.

2019 Update on gynecologic cancer

Of the major developments in 2018 that changed practice in gynecologic oncology, we highlight 3 here.

First, a trial on the use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for patients with ovarian cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated an overall survival benefit of 12 months for patients treated with HIPEC. Second, a trial on polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors as maintenance therapy after adjuvant chemotherapy showed that women with a BRCA mutation had a progression-free survival benefit of nearly 3 years. Third, the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer trial revealed a significant decrease in survival in women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy compared with those who had the traditional open approach. In addition, a retrospective study that analyzed information from large cancer databases showed that national survival rates decreased for patients with cervical cancer as the use of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy rose.

In this Update, we summarize the major findings of these trials, provide background on treatment strategies, and discuss how our practice as cancer specialists has changed in light of these studies' findings.

HIPEC improves overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer—by a lot

Van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:230-240.

In the United States, women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer typically are treated with primary cytoreductive (debulking) surgery followed by platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy. The goal of cytoreductive surgery is the resection of all grossly visible tumor. While associated with favorable oncologic outcomes, cytoreductive surgery also is accompanied by significant morbidity, and surgery is not always feasible.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has emerged as an alternative treatment strategy to primary cytoreductive surgery. Women treated with NACT typically undergo 3 to 4 cycles of platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy, receive interval cytoreduction, and then are treated with an additional 3 to 4 cycles of chemotherapy postoperatively. Several large, randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that survival is similar for women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer treated with either primary cytoreduction or NACT.1,2 Importantly, perioperative morbidity is substantially lower with NACT and the rate of complete tumor resection is improved. Use of NACT for ovarian cancer has increased substantially in recent years.3

Rationale for intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy has long been utilized in the treatment of ovarian cancer.4 Given that the abdomen is the most common site of metastatic spread for ovarian cancer, there is a strong rationale for direct infusion of chemotherapy into the abdominal cavity. Several early trials showed that adjuvant IP chemotherapy improves survival compared with intravenous chemotherapy alone.5,6 Yet complete adoption of IP chemotherapy has been limited by evidence of moderately increased toxicities, such as pain, infections, and bowel obstructions, as well as IP catheter complications.5,7

Heated IP chemotherapy for recurrent ovarian cancer

More recently, interest has focused on HIPEC. In this approach, chemotherapy is heated to 42°C and administered into the abdominal cavity immediately after cytoreductive surgery; a temperature of 40°C to 41°C is maintained for total perfusion over a 90-minute period. The increased temperature induces apoptosis and protein degeneration, leading to greater penetration by the chemotherapy along peritoneal surfaces.8

For ovarian cancer, HIPEC has been explored in a number of small studies, predominately for women with recurrent disease.9 These studies demonstrated that HIPEC increased toxicities with gastrointestinal and renal complications but improved overall and disease-free survival.

HIPEC for primary treatment

Van Driel and colleagues explored the safety and efficacy of HIPEC for the primary treatment of ovarian cancer.10 In their multicenter trial, the authors sought to determine if there was a survival benefit with HIPEC in patients with stage III ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer treated with NACT. Eligible participants initially were treated with 3 cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Two-hundred forty-five patients who had a response or stable disease were then randomly assigned to undergo either interval cytoreductive surgery alone or surgery with HIPEC using cisplatin. Both groups received 3 additional cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel after surgery.

Results. Treatment with HIPEC was associated with a 3.5-month improvement in recurrence-free survival compared with surgery alone (14.2 vs 10.7 months) and a 12-month improvement in overall survival (45.7 vs 33.9 months). After a median follow-up of 4.7 years, 62% of patients in the surgery group and 50% of the patients in the HIPEC group had died.

Adverse events. Rates of grade 3 and 4 adverse events were similar for both treatment arms (25% in the surgery group vs 27% in the HIPEC plus surgery group), and there was no significant difference in hospital length of stay (8 vs 10 days, which included a mandatory 1-night stay in the intensive care unit for HIPEC-treated patients).

For carefully selected women with advanced ovarian cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, HIPEC at the time of interval cytoreductive surgery may improve survival by a year.

Continue to: PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer...

PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer, especially for women with a BRCA mutation

Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest malignancy affecting women in the United States. While patients are likely to respond to their initial chemotherapy and surgery, there is a significant risk for cancer recurrence, from which the high mortality rates arise.

Maintenance therapy has considerable potential for preventing recurrences. Based on the results of a large Gynecologic Oncology Group study,11 in 2017 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bevacizumab for use in combination with and following standard carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for women with advanced ovarian cancer. In the trial, maintenance therapy with 10 months of bevacizumab improved progression-free survival by 4 months; however, it did not improve overall survival, and adverse events included bowel perforations and hypertension.11 Alternative targets for maintenance therapy to prevent or minimize the risk of recurrence in women with ovarian cancer have been actively investigated.

PARP inhibitors work by damaging cancer cell DNA

PARP is a key enzyme that repairs DNA damage within cells. Drugs that inhibit PARP trap this enzyme at the site of single-strand breaks, disrupting single-strand repair and inducing double-strand breaks. Since the homologous recombination pathway used to repair double-strand DNA breaks does not function in BRCA-mutated tissues, PARP inhibitors ultimately induce targeted DNA damage and apoptosis in both germline and somatic BRCA mutation carriers.12

In the United States, 3 PARP inhibitors (olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib) are FDA approved as maintenance therapy for use in women with recurrent ovarian cancer that had responded completely or partially to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status. PARP inhibitors also have been approved for treatment of advanced ovarian cancer in BRCA mutation carriers who have received 3 or more lines of platinum-based chemotherapy. Because of their efficacy in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer, there is great interest in using PARP inhibitors earlier in the disease course.

Olaparib is effective in women with BRCA mutations

In an international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial, Moore and colleagues sought to determine the efficacy of the PARP inhibitor olaparib administered as maintenance therapy in women with germline or somatic BRCA mutations.13 Women were eligible if they had BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations with newly diagnosed advanced (stage III or IV) ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer and a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy after cytoreduction.

Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio, with 260 participants receiving twice daily olaparib and 131 receiving placebo.

Results. After 41 months of follow-up, the disease-free survival rate was 60% in the olaparib group, compared with 27% in the placebo arm. Progression-free survival was 36 months longer in the olaparib maintenance group than in the placebo group.

Adverse events. While 21% of women treated with olaparib experienced serious adverse events (compared with 12% in the placebo group), most were related to anemia. Acute myeloid leukemia occurred in 3 (1%) of the 260 patients receiving olaparib.

For women with deleterious BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations, administering PARP inhibitors as a maintenance therapy following primary treatment with the standard platinum-based chemotherapy improves progression-free survival by at least 3 years.

Continue to: Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

For various procedures, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is associated with decreased blood loss, shorter postoperative stay, and decreased postoperative complications and readmission rates. In oncology, MIS has demonstrated equivalent outcomes compared with open procedures for colorectal and endometrial cancers.14,15

Increasing use of MIS in cervical cancer

For patients with cervical cancer, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy has more favorable perioperative outcomes, less morbidity, and decreased costs than open radical hysterectomy.16-20 However, many of the studies used to justify these benefits were small, lacked adequate follow-up, and were not adequately powered to detect a true survival difference. Some trials compared contemporary MIS enrollees to historical open surgery controls, who may have had more advanced-stage disease and may have been treated with different adjuvant chemoradiation.

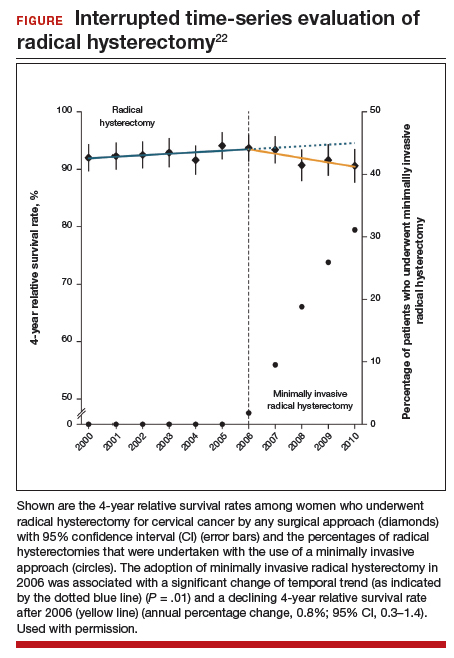

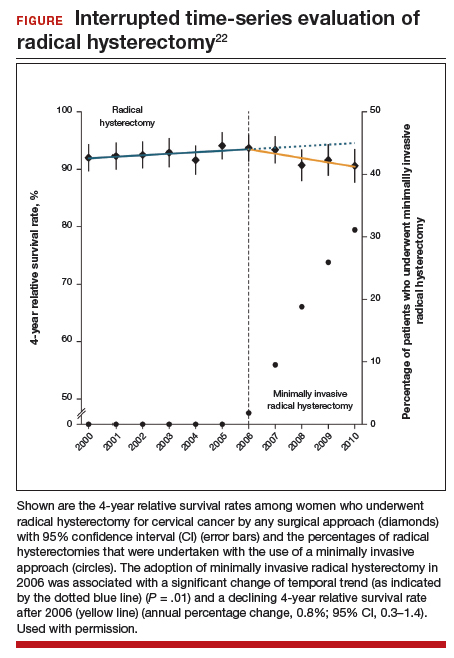

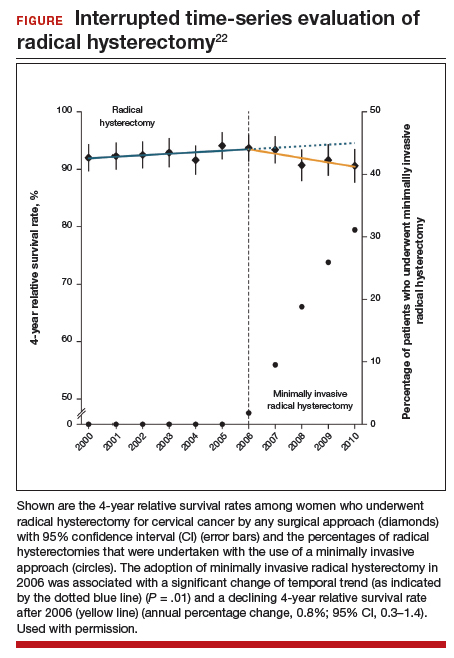

Despite these major limitations, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy became an acceptable—and often preferable—alternative to open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. This acceptance was written into National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines,21 and minimally invasive radical hysterectomy rapidly gained popularity, increasing from 1.8% in 2006 to 31% in 2010.22

Randomized trial revealed surprising findings

Ramirez and colleagues recently published the results of the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial, a randomized controlled trial that compared open with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy in women with stage IA1-IB1 cervical cancer.23 The study was designed as a noninferiority trial in which researchers set a threshold of -7.2% for how much worse the survival of MIS patients could be compared with open surgery before MIS could be declared an inferior treatment. A total of 631 patients were enrolled at 33 centers worldwide. After an interim analysis demonstrated a safety signal in the MIS radical hysterectomy cohort, the study was closed before completion of enrollment.

Overall, 91% of patients randomly assigned to treatment had stage IB1 tumors. At the time of analysis, nearly 60% of enrollees had survival data at 4.5 years to provide adequate power for full analysis.

Results. Disease-free survival (the time from randomization to recurrence or death from cervical cancer) was 86.0% in the MIS group and 96.5% in the open hysterectomy group. At 4.5 years, 27 MIS patients had recurrent disease, compared with 7 patients who underwent abdominal radical hysterectomy. There were 14 cancer-related deaths in the MIS group, compared with 2 in the open group.

Three-year disease-free survival was 91.2% in the MIS group versus 97.1% in the abdominal radical hysterectomy group (hazard ratio, 3.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-8.58) The overall 3-year survival was 93.8% in the MIS group, compared with 99.0% in the open group.23

Retrospective cohort study had similar results

Concurrent with publication of the LACC trial results, Melamed and colleagues published an observational study on the safety of MIS radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer.22 They used data from the National Cancer Database to examine 2,461 women with stage IA2-IB1 cervical cancer who underwent radical hysterectomy from 2010 to 2013. Approximately half of the women (49.8%) underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy.

Results. After a median follow-up of 45 months, the 4-year mortality rate was 9.1% among women who underwent MIS radical hysterectomy, compared with 5.3% for those who had an abdominal radical hysterectomy.

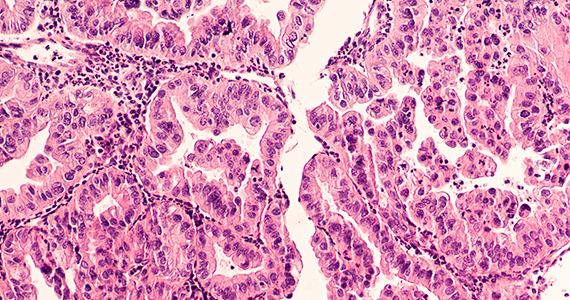

Using the complimentary Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry dataset, the authors examined population-level trends in use of MIS radical hysterectomy and survival. From 2000 to 2006, when MIS radical hysterectomy was rarely utilized, 4-year survival for cervical cancer was relatively stable. After adoption of MIS radical hysterectomy in 2006, 4-year relative survival declined by 0.8% annually for cervical cancer (FIGURE).22

Both a randomized controlled trial and a large observational study demonstrated decreased survival for women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy. Use of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy should be used with caution in women with early-stage cervical cancer.

- Vergote I, Trope CG, Amant F, et al; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Gynaecological Cancer Group; NCIC Clinical Trials Group. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943-953.

- Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386:249-257.

- Melamed A, Hinchcliff EM, Clemmer JT, et al. Trends in the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer in the United States. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:236-240.

- Markman M. Intraperitoneal antineoplastic drug delivery: rationale and results. Lancet Oncol. 2003;4:277-283.

- Markman M, Bundy BN, Alberts DS, et al. Phase III trial of standard-dose intravenous cisplatin plus paclitaxel versus moderately high-dose carboplatin followed by intravenous paclitaxel and intraperitoneal cisplatin in small-volume stage III ovarian carcinoma: an intergroup study of the Gynecologic Oncology Group, Southwestern Oncology Group, and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:1001-1007.

- Armstrong DK, Bundy B, Wenzel L, et al; Gynecologic Oncology Group. Intraperitoneal cisplatin and paclitaxel in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:34-43.

- Alberts DS, Liu PY, Hannigan EV, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide versus intravenous cisplatin plus intravenous cyclophosphamide for stage III ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1950-1955.

- van de Vaart PJ, van der Vange N, Zoetmulder FA, et al. Intraperitoneal cisplatin with regional hyperthermia in advanced ovarian cancer: pharmacokinetics and cisplatin-DNA adduct formation in patients and ovarian cancer cell lines. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:148-154.

- Bakrin N, Cotte E, Golfier F, et al. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for persistent and recurrent advanced ovarian carcinoma: a multicenter, prospective study of 246 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:4052-4058.

- van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:230-240.

- Burger RA, Brady MF, Bookman MA, et al; Gynecologic Oncology Group. Incorporation of bevacizumab in the primary treatment of ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2473-2483.

- Farmer H, McCabe N, Lord CJ, et al. Targeting the DNA repair defect in BRCA mutant cells as a therapeutic strategy. Nature. 2005;434:917-921.

- Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

- Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, et al. Recurrence and survival after random assignment to laparoscopy versus laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group LAP2 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:695-700.

- Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Therapy Study Group, Nelson H, Sargent DJ, et al. A comparison of laparoscopically assisted and open colectomy for colon cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2050-2059.

- Lee EJ, Kang H, Kim DH. A comparative study of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy with radical abdominal hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2011;156:83-86.

- Malzoni M, Tinelli R, Cosentino F, et al. Total laparoscopic radical hysterectomy versus abdominal radical hysterectomy with lymphadenectomy in patients with early cervical cancer: our experience. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:1316-1323.

- Nam JH, Park JY, Kim DY, et al. Laparoscopic versus open radical hysterectomy in early-stage cervical cancer: long-term survival outcomes in a matched cohort study. Ann Oncol. 2012;23:903-911.

- Obermair A, Gebski V, Frumovitz M, et al. A phase III randomized clinical trial comparing laparoscopic or robotic radical hysterectomy with abdominal radical hysterectomy in patients with early stage cervical cancer. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15:584-588.

- Mendivil AA, Rettenmaier MA, Abaid LN, et al. Survival rate comparisons amongst cervical cancer patients treated with an open, robotic-assisted or laparoscopic radical hysterectomy: a five year experience. Surg Oncol. 2016;25:66-71.

- National Comprehensive Care Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: cervical cancer, version 1.2018. http://oncolife.com.ua/doc/nccn/Cervical_Cancer.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2019.

- Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

- Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Of the major developments in 2018 that changed practice in gynecologic oncology, we highlight 3 here.

First, a trial on the use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for patients with ovarian cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated an overall survival benefit of 12 months for patients treated with HIPEC. Second, a trial on polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors as maintenance therapy after adjuvant chemotherapy showed that women with a BRCA mutation had a progression-free survival benefit of nearly 3 years. Third, the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer trial revealed a significant decrease in survival in women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy compared with those who had the traditional open approach. In addition, a retrospective study that analyzed information from large cancer databases showed that national survival rates decreased for patients with cervical cancer as the use of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy rose.

In this Update, we summarize the major findings of these trials, provide background on treatment strategies, and discuss how our practice as cancer specialists has changed in light of these studies' findings.

HIPEC improves overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer—by a lot

Van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:230-240.

In the United States, women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer typically are treated with primary cytoreductive (debulking) surgery followed by platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy. The goal of cytoreductive surgery is the resection of all grossly visible tumor. While associated with favorable oncologic outcomes, cytoreductive surgery also is accompanied by significant morbidity, and surgery is not always feasible.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has emerged as an alternative treatment strategy to primary cytoreductive surgery. Women treated with NACT typically undergo 3 to 4 cycles of platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy, receive interval cytoreduction, and then are treated with an additional 3 to 4 cycles of chemotherapy postoperatively. Several large, randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that survival is similar for women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer treated with either primary cytoreduction or NACT.1,2 Importantly, perioperative morbidity is substantially lower with NACT and the rate of complete tumor resection is improved. Use of NACT for ovarian cancer has increased substantially in recent years.3

Rationale for intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy has long been utilized in the treatment of ovarian cancer.4 Given that the abdomen is the most common site of metastatic spread for ovarian cancer, there is a strong rationale for direct infusion of chemotherapy into the abdominal cavity. Several early trials showed that adjuvant IP chemotherapy improves survival compared with intravenous chemotherapy alone.5,6 Yet complete adoption of IP chemotherapy has been limited by evidence of moderately increased toxicities, such as pain, infections, and bowel obstructions, as well as IP catheter complications.5,7

Heated IP chemotherapy for recurrent ovarian cancer

More recently, interest has focused on HIPEC. In this approach, chemotherapy is heated to 42°C and administered into the abdominal cavity immediately after cytoreductive surgery; a temperature of 40°C to 41°C is maintained for total perfusion over a 90-minute period. The increased temperature induces apoptosis and protein degeneration, leading to greater penetration by the chemotherapy along peritoneal surfaces.8

For ovarian cancer, HIPEC has been explored in a number of small studies, predominately for women with recurrent disease.9 These studies demonstrated that HIPEC increased toxicities with gastrointestinal and renal complications but improved overall and disease-free survival.

HIPEC for primary treatment

Van Driel and colleagues explored the safety and efficacy of HIPEC for the primary treatment of ovarian cancer.10 In their multicenter trial, the authors sought to determine if there was a survival benefit with HIPEC in patients with stage III ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer treated with NACT. Eligible participants initially were treated with 3 cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Two-hundred forty-five patients who had a response or stable disease were then randomly assigned to undergo either interval cytoreductive surgery alone or surgery with HIPEC using cisplatin. Both groups received 3 additional cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel after surgery.

Results. Treatment with HIPEC was associated with a 3.5-month improvement in recurrence-free survival compared with surgery alone (14.2 vs 10.7 months) and a 12-month improvement in overall survival (45.7 vs 33.9 months). After a median follow-up of 4.7 years, 62% of patients in the surgery group and 50% of the patients in the HIPEC group had died.

Adverse events. Rates of grade 3 and 4 adverse events were similar for both treatment arms (25% in the surgery group vs 27% in the HIPEC plus surgery group), and there was no significant difference in hospital length of stay (8 vs 10 days, which included a mandatory 1-night stay in the intensive care unit for HIPEC-treated patients).

For carefully selected women with advanced ovarian cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, HIPEC at the time of interval cytoreductive surgery may improve survival by a year.

Continue to: PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer...

PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer, especially for women with a BRCA mutation

Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest malignancy affecting women in the United States. While patients are likely to respond to their initial chemotherapy and surgery, there is a significant risk for cancer recurrence, from which the high mortality rates arise.

Maintenance therapy has considerable potential for preventing recurrences. Based on the results of a large Gynecologic Oncology Group study,11 in 2017 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bevacizumab for use in combination with and following standard carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for women with advanced ovarian cancer. In the trial, maintenance therapy with 10 months of bevacizumab improved progression-free survival by 4 months; however, it did not improve overall survival, and adverse events included bowel perforations and hypertension.11 Alternative targets for maintenance therapy to prevent or minimize the risk of recurrence in women with ovarian cancer have been actively investigated.

PARP inhibitors work by damaging cancer cell DNA

PARP is a key enzyme that repairs DNA damage within cells. Drugs that inhibit PARP trap this enzyme at the site of single-strand breaks, disrupting single-strand repair and inducing double-strand breaks. Since the homologous recombination pathway used to repair double-strand DNA breaks does not function in BRCA-mutated tissues, PARP inhibitors ultimately induce targeted DNA damage and apoptosis in both germline and somatic BRCA mutation carriers.12

In the United States, 3 PARP inhibitors (olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib) are FDA approved as maintenance therapy for use in women with recurrent ovarian cancer that had responded completely or partially to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status. PARP inhibitors also have been approved for treatment of advanced ovarian cancer in BRCA mutation carriers who have received 3 or more lines of platinum-based chemotherapy. Because of their efficacy in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer, there is great interest in using PARP inhibitors earlier in the disease course.

Olaparib is effective in women with BRCA mutations

In an international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial, Moore and colleagues sought to determine the efficacy of the PARP inhibitor olaparib administered as maintenance therapy in women with germline or somatic BRCA mutations.13 Women were eligible if they had BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations with newly diagnosed advanced (stage III or IV) ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer and a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy after cytoreduction.

Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio, with 260 participants receiving twice daily olaparib and 131 receiving placebo.

Results. After 41 months of follow-up, the disease-free survival rate was 60% in the olaparib group, compared with 27% in the placebo arm. Progression-free survival was 36 months longer in the olaparib maintenance group than in the placebo group.

Adverse events. While 21% of women treated with olaparib experienced serious adverse events (compared with 12% in the placebo group), most were related to anemia. Acute myeloid leukemia occurred in 3 (1%) of the 260 patients receiving olaparib.

For women with deleterious BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations, administering PARP inhibitors as a maintenance therapy following primary treatment with the standard platinum-based chemotherapy improves progression-free survival by at least 3 years.

Continue to: Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

For various procedures, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is associated with decreased blood loss, shorter postoperative stay, and decreased postoperative complications and readmission rates. In oncology, MIS has demonstrated equivalent outcomes compared with open procedures for colorectal and endometrial cancers.14,15

Increasing use of MIS in cervical cancer

For patients with cervical cancer, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy has more favorable perioperative outcomes, less morbidity, and decreased costs than open radical hysterectomy.16-20 However, many of the studies used to justify these benefits were small, lacked adequate follow-up, and were not adequately powered to detect a true survival difference. Some trials compared contemporary MIS enrollees to historical open surgery controls, who may have had more advanced-stage disease and may have been treated with different adjuvant chemoradiation.

Despite these major limitations, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy became an acceptable—and often preferable—alternative to open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. This acceptance was written into National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines,21 and minimally invasive radical hysterectomy rapidly gained popularity, increasing from 1.8% in 2006 to 31% in 2010.22

Randomized trial revealed surprising findings

Ramirez and colleagues recently published the results of the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial, a randomized controlled trial that compared open with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy in women with stage IA1-IB1 cervical cancer.23 The study was designed as a noninferiority trial in which researchers set a threshold of -7.2% for how much worse the survival of MIS patients could be compared with open surgery before MIS could be declared an inferior treatment. A total of 631 patients were enrolled at 33 centers worldwide. After an interim analysis demonstrated a safety signal in the MIS radical hysterectomy cohort, the study was closed before completion of enrollment.

Overall, 91% of patients randomly assigned to treatment had stage IB1 tumors. At the time of analysis, nearly 60% of enrollees had survival data at 4.5 years to provide adequate power for full analysis.

Results. Disease-free survival (the time from randomization to recurrence or death from cervical cancer) was 86.0% in the MIS group and 96.5% in the open hysterectomy group. At 4.5 years, 27 MIS patients had recurrent disease, compared with 7 patients who underwent abdominal radical hysterectomy. There were 14 cancer-related deaths in the MIS group, compared with 2 in the open group.

Three-year disease-free survival was 91.2% in the MIS group versus 97.1% in the abdominal radical hysterectomy group (hazard ratio, 3.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-8.58) The overall 3-year survival was 93.8% in the MIS group, compared with 99.0% in the open group.23

Retrospective cohort study had similar results

Concurrent with publication of the LACC trial results, Melamed and colleagues published an observational study on the safety of MIS radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer.22 They used data from the National Cancer Database to examine 2,461 women with stage IA2-IB1 cervical cancer who underwent radical hysterectomy from 2010 to 2013. Approximately half of the women (49.8%) underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy.

Results. After a median follow-up of 45 months, the 4-year mortality rate was 9.1% among women who underwent MIS radical hysterectomy, compared with 5.3% for those who had an abdominal radical hysterectomy.

Using the complimentary Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry dataset, the authors examined population-level trends in use of MIS radical hysterectomy and survival. From 2000 to 2006, when MIS radical hysterectomy was rarely utilized, 4-year survival for cervical cancer was relatively stable. After adoption of MIS radical hysterectomy in 2006, 4-year relative survival declined by 0.8% annually for cervical cancer (FIGURE).22

Both a randomized controlled trial and a large observational study demonstrated decreased survival for women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy. Use of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy should be used with caution in women with early-stage cervical cancer.

Of the major developments in 2018 that changed practice in gynecologic oncology, we highlight 3 here.