User login

After 62 years, her husband is a ‘stranger’

Presenting symptoms: Marital memories

Ms. A, age 83, has been experiencing increasing confusion, agitation, and memory loss across 4 to 5 years. Family members say her memory loss has become prominent within the last year. She can no longer cook, manage her finances, shop, or perform other basic activities. At times she does not recognize her husband of 62 years and needs help with bathing and grooming.

Ms. A’s Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score is 18, indicating moderate dementia. She exhibits disorientation, diminished short-term memory, impaired attention including apraxia, and executive dysfunction. Her Geriatric Depression Scale (15-item short form) score indicates normal mood.

A neurologic exam reveals mild parkinsonism, including mild bilateral upper-extremity cogwheeltype rigidity and questionable frontal release signs including a possible mild bilateral grasp reflex. No snout reflex was seen.

This presentation suggests Ms. A has:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Lewy body dementia

- or vascular dementia

The authors’ observations:

Differentiating among Alzheimer’s, Lewy body, and vascular dementias is important (Table 1), as their treatments and clinical courses differ.

The initial workup’s goal is to diagnose a reversible medical condition that may be hastening cognitive decline. Brain imaging (CT or MRI) can uncover cerebrovascular disease, subdural hematomas, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, tumors, or other cerebral diseases. Laboratory tests can reveal systemic conditions such as hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, hypercalcemia, neurosyphilis, or HIV infection.1

Table 1

Differences in Alzheimer’s, Lewy body, and vascular dementias

| Alzheimer’s dementia | Lewy body dementia | Vascular dementia |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual onset and chronic cognitive decline Memory difficulty combined with apraxia, aphasia, agnosia, or executive dysfunction | Cognitive, memory changes with one or more of the following:

| Early findings often include depression or personality changes, plus incontinence and gait disorder |

| Psychosis common in middle to late stages | Visual hallucinations, other psychoses in early stages Periods of marked delirium, “sundowning” | Temporal relationship between stroke and dementia onset, but variability in course |

| Day-to-day cognitive performance stable | Cognitive performance fluctuates during early stages. | Day-to-day cognitive performance stable |

| Parkinsonism not apparent in early stages, may present in middle to late stages | Parkinsonism in early stages Tremor not common | Gait disorder and parkinsonism common, especially with basal ganglia infarcts |

| Neurologic signs present in late stages | Exquisite sensitivity to neuroleptic therapy | Increased sensitivity to neuroleptics |

| Cannot be explained as vascular or mixed-type dementia | Cannot be explained as vascular or mixed-type dementia | Imaging necessary to document cerebrovascular disease |

With a thorough history and laboratory testing, a diagnosis of “probable” AD can be as much as 85% accurate. Probable AD is characterized by progressive gradual decline of cognitive functions affecting memory and at least one other domain including executive dysfunction, apraxia, aphasia, and/or agnosia. These deficits must cause significant functional impairment.

Neurologic test results may support AD diagnosis after ruling out reversible causes of dementia. Neuropsychological testing can provide valuable early information when subtle findings cannot be ascertained on clinical screening. (For a listing of neuropsychological tests, see this article at currentpsychiatry.com.)

Diagnosis: An unpredictable patient

Ms. A received a CBC; comprehensive metabolic panel; urinalysis; screens for rapid plasma reagin, B12, folate, and homocysteine levels; and a brain MRI. Hemoglobin and serum albumin were mildly depressed, reflecting early malnutrition. MRI showed generalized cerebral atrophy. Significant vascular disease was not identified.

Ms. A was diagnosed as having probable Alzheimer’s-type dementia based on the test results and the fact that her cognition was steadily declining. Other explanatory mechanisms were absent. She did not exhibit hallucinatory psychosis or fluctuating consciousness, which would signal Lewy body dementia.

Table 2

Medications for treating agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia

| Drug | Supporting evidence | Recommended dosage (mg/d)* | Rationale | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants | ||||

| Carbamazepine | Tariot et al2 | 200 to 1,200 mg/d in divided doses | Commonly used for impulse control disorders | Agranulocytosis, hyponatremia, liver toxicity (all rare) |

| Divalproex | Loy and Tariot3 | 250 to 2,000 mg/d | Increasing evidence points to neuroprotective qualities | Possible white blood cell suppression, liver toxicity, pancreatitis (all rare) |

| Gabapentin | Roane et al4 | 100 to 1,200 mg/d | Safe in patients with hepatic dysfunction | Scant data on use in Alzheimer’s disease |

| Lamotrigine | Tekin et al5 | Start at 25 mg/d; titrate slowly to 50 to 200 mg/d | Possibly neuroprotective via N-methyl-D-aspartate mechanism | Rapid titration may cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| Atypical antipsychotics | ||||

| Olanzapine | Street et al6 | 2.5 to 10 mg/d | Sedating effects may aid sleep | Anticholinergic effects may increase confusion, compound cognitive deficit |

| Quetiapine | Tariot et al7 | 25 to 300 mg/d | Tolerable Sedating effects may aid sleep | Watch for orthostasis, especially at higher dosages |

| Risperidone | DeVane et al8 | 0.25 to 3 mg/d | Strong data support use | High orthostatic potential, possible extrapyramidal symptoms with higher dosages |

| Ziprasidone | None | Oral:20to80mgbid IM: 10 to 20 mg, maximum 40 mg over 24 hours | Effective in managing agitation | No controlled trials, case reports in AD-associated agitation |

| SSRIs | ||||

| Citalopram | Pollock et al9 | 10 to 40 mg/d | Minimal CYP-2D6 inhibition | Effect may take 2 to 4 weeks |

| Sertraline | Lyketsos et al10 | 25 to 200 mg/d | Minimal CYP-2D6 inhibition | Effect may take 2 to 4 weeks |

| * No specific, widely accepted dosing guidelines exist for patients age > 65, but this group often does not tolerate higher dosages. | ||||

| SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||||

| IM: Intramuscula | ||||

The psychiatrist started galantamine, 4 mg bid, and vitamin E, 400 IU bid, to maximize her cognition and attempt to slow her functional decline. Ms. A, who was in an assisted living facility when we evaluated her, was transferred to the facility’s nursing section shortly afterward.

At follow-up 3 weeks later, Ms. A’s behavior improved moderately, but she remained unpredictable and intermittently agitated. Staff reported that she was physically assaulting caregivers two to three times weekly.

Which medication(s) would you use to control Ms. A’s agitation and paranoia?

- an SSRI

- a mood stabilizer

- an atypical antipsychotic

- a combination or two or more of these drug classes

The authors’ observations

Aside from controlling agitation, medication treatment in AD should slow cognitive decline, improve behavior, help the patient perform daily activities, and delay nursing home placement.

- Watch for drug-drug interactions. Many patients with AD also are taking medications for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, arthritis, and other medical comorbidities.

- Start low and go slow. Older patients generally do not tolerate rapid dos-ing adjustments as well as younger patients (Table 2).

SSRIS. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors increase serotonin at the synaptic terminal. Serotonin has long been associated with impulsivity and aggression, and decreased 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid, a metabolite of serotonin, has been found in violent criminals and in psychiatric patients who have demonstrated inward or outward aggression.11

SSRIs generally are tolerable, safe, effective, and have little cholinergic blockade. Citalopram and sertraline minimally inhibit the cytochrome P-450 2D6 isoenzyme and have lower proteinbinding affinities than fluoxetine or paroxetine. Thus, citalopram and sertraline are less likely to alter therapeutic levels of highly bound medications through displacement of either drug’s protein-bound portion.10

Anticonvulsants with mood-stabilizing effects are another option. Reasonably strong data support use of divalproex for managing agitation in AD, either as a first-line agent or as an adjunct after failed SSRI therapy. Unlike other anticonvulsants, divalproex also may be neuroprotective.3

Divalproex, however, is associated with white blood cell suppression, significant liver toxicity, and pancreatitis, although these effects are rare.13 Monitor white blood cell counts and liver enzymes early in treatment, even if divalproex blood levels below the standard reference range produce a response.14

Though not studied specifically for treating agitation in AD, carbamazepine has demonstrated significant short-term efficacy in treating dementia-related agitation and aggression.2 Scant data support use of gabapentin or lamotrigine in Alzheimer’s dementia, but these agents are often used to manage agitation in other disorders.

Atypical antipsychotics. Psychosis usually occurs in middle-to-late-stage AD but can occur at any point. If psychosis occurs early, rule out Lewy body dementia.15

Choose an atypical antipsychotic that exhibits rapid dopamine receptor dissociation constants to reduce the risk of extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and cognitive decline with prolonged use. Quetiapine has shown efficacy for treating behavioral problems in Alzheimer’s and Lewy body dementia,7 and its sedating effects may help regulate sleep-wake cycles.

Data support use of olanzapine for agitation in AD,6 but watch for anticholinergic effects including worsening of cognition. Fast-dissolving olanzapine and risperidone oral wafers may help circumvent dosing difficulties in patients who cannot swallow—or will not take—their medication. Intramuscular olanzapine and ziprasidone have shown efficacy in treating acute agitation, but no systematic studies have examined their use in agitation secondary to dementia.

Recent data suggest a modestly increased risk of cerebrovascular accidents in AD patients taking atypicals compared with placebo, but the absolute rate of such events remains low.

Treatment: 3 months of stability

Ms. A’s galantamine dosage was increased to 8 mg bid and sertraline—25 mg/d for 7 days, then 50 mg/d—was added in an effort to better control her agitation, but the behavior continued unabated for 2 weeks. Divalproex, 125 mg bid titrated over 4 weeks to 750 mg/d, was added. Still, her agitation persisted.

Over the next 4 to 6 weeks, Ms. A showed signs of psychosis, often talking to herself and occasionally reporting “people attacking me.” She became paranoid toward members of her church, who she said were “trying to hurt” her. The paranoia intensified her agitation and disrupted her sleep. Physical examination was unremarkable, as were chest X-ray and urinalysis.

Sertraline and divalproex were gradually discontinued. Quetiapine—25 mg nightly, titrated across 2 weeks to 150 mg nightly—was started. Ms. A’s agitation and psychosis decreased with quetiapine titration, and her sleep improved. Her paranoid delusions remained but no longer impeded functioning or prompted a violent reaction.

Then after remaining stable for about 3 months, Ms. A’s paranoid delusions worsened and her agitation increased.

What treatment options are available at this point?

The authors’ observations

Treating agitation and delaying nursing home placement for patients with AD is challenging. When faced with inadequate or no response, consider less-conventional alternatives.

Vitamin E and selegiline were found separately to postpone functional decline in ambulatory patients with moderately severe AD, but the agents given together were less effective than either agent alone.16

Use of methylphenidate,17 buspirone,18 clonazepam,19 zolpidem,20 and—most recently— memantine21 for AD-related agitation also has been described.

Continued treatment: Medication changes

Quetiapine was increased to 350 mg nightly across 4 weeks, resulting in mild to moderate improvement. The higher dosage did not significantly worsen rigidity or motor function, and Ms. A tolerated the increased dosage without clinical orthostasis.

Memantine was added to address Ms. A’s agitation and preserve function. The agent was started at 5 mg/d and titrated across 4 weeks to 10 mg bid.

On clinical exam, Ms. A was more calm and directable and required less intervention. Her paranoia also decreased, allowing improved interaction with family, caregivers, and others. Ms. A remains stable on memantine, 10 mg bid; galantamine, 8 mg; quetiapine, 350 mg nightly; and vitamin E, 400 IU bid. Her cognitive ability has gradually declined over the past 18 months, as evidenced by her most recent MMSE score of 16/30.

Related resources

- Cummings JL. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors in clinical practice: evidence-based recommendations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:131-45.

- Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center, a service of the National Institute on Aging. http://www.alzheimers.org.

- Paleacu D, Mazeh D, Mirecki I, et al. Donepezil for the treatment of behavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 2002;25:313-7.

- Tariot PN, Loy R, Ryan JM, et al. Mood stabilizers in Alzheimer’s disease: symptomatic and neuroprotective rationales. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2002;54:1567-77.

Drug brand names

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex • Depakote, DepakoteER

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Galantamine • Reminyl

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Memantine • Namenda

- Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone wafers • RisperdalM-Tabs

- Rivastigmine • Exelon

- Selegiline • Eldepryl

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosure

Dr. Goforth is a speaker for Pfizer Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals, and BristolMyers Squibb Co., and has received grant support from Pfizer Inc. He has also received support from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry through the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Dr. Rao is a speaker for Pfizer Inc.

Drs. Raval and Ruth report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Askin-Edgar S, White KE, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric aspects of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementing illnesses. In: Textbook of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences (4th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002.

2. Tariot PN, Erb R, Podgorski CA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of carbamazepine for agitation and aggression in dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:54-61.

3. Loy R, Tariot PN. Neuroprotective properties of valproate: potential benefit for AD and tauopathies. J Mol Neurosci 2002;19:303-7.

4. Roane DM, Feinberg TE, Meckler L, et al. Treatment of dementiaassociated agitation with gabapentin. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000;12:40-3.

5. Tekin S, Aykut-Bingol C, Tanridag T, Aktan S. Antiglutamatergic therapy in Alzheimer’s disease—effects of lamotrigine. J Neural Transm 1998;105:295-303.

6. Street JS, Clark WS, Kadam DL, et al. Long-term efficacy of olanzapine in the control of psychotic and behavioral symptoms in nursing home patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16(suppl 1):S62-S70.

7. Tariot PN, Ismail MS. Use of quetiapine in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(suppl 13):21-6.

8. DeVane CL, Mintzer J. Risperidone in the management of psychiatric and neurodegenerative disease in the elderly: an update. Psychopharmacol Bull 2003;37:116-32.

9. Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. Comparison of citalopram, perphenazine, and placebo for the acute treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances in hospitalized, demented patients. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:460-5.

10. Lyketsos CG, DelCampo L, Steinberg M, et al. Treating depression in Alzheimer disease: efficacy and safety of sertraline therapy, and the benefits of depression reduction: the DIADS. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:737-46.

11. Swann AC. Neuroreceptor mechanisms of aggression and its treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 4):26-35.

12. Olin JT, Schneider LS, Katz IR, et al. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;10:125-8.

13. Physician’sdesk reference(58thed). Montvale, NJ:Thomson PDR,2004.

14. Porsteinsson AP, Tariot PN, Erb R, Gaile S. An open trial of valproate for agitation in geriatric neuropsychiatric disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;5:344-51.

15. Assal F, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in the dementias. Curr Opin Neurol 2002;15:445-50.

16. Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, et al. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1216-22.

17. Kittur S, Hauser P. Improvement of sleep and behavior by methylphenidate in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1116-7.

18. Salzman C. Treatment of the agitation of late-life psychosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Psychiatry 2001;16(suppl 1):25s-28s.

19. Ginsburg ML. Clonazepam for agitated patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Can J Psychiatry 1991;36:237-8.

20. Jackson CW, Pitner JK, Mintzer JE. Zolpidem for the treatment of agitation in elderly demented patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:372-3.

21. Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler A, et al. Memantine Study Group. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1333-41.

Presenting symptoms: Marital memories

Ms. A, age 83, has been experiencing increasing confusion, agitation, and memory loss across 4 to 5 years. Family members say her memory loss has become prominent within the last year. She can no longer cook, manage her finances, shop, or perform other basic activities. At times she does not recognize her husband of 62 years and needs help with bathing and grooming.

Ms. A’s Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score is 18, indicating moderate dementia. She exhibits disorientation, diminished short-term memory, impaired attention including apraxia, and executive dysfunction. Her Geriatric Depression Scale (15-item short form) score indicates normal mood.

A neurologic exam reveals mild parkinsonism, including mild bilateral upper-extremity cogwheeltype rigidity and questionable frontal release signs including a possible mild bilateral grasp reflex. No snout reflex was seen.

This presentation suggests Ms. A has:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Lewy body dementia

- or vascular dementia

The authors’ observations:

Differentiating among Alzheimer’s, Lewy body, and vascular dementias is important (Table 1), as their treatments and clinical courses differ.

The initial workup’s goal is to diagnose a reversible medical condition that may be hastening cognitive decline. Brain imaging (CT or MRI) can uncover cerebrovascular disease, subdural hematomas, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, tumors, or other cerebral diseases. Laboratory tests can reveal systemic conditions such as hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, hypercalcemia, neurosyphilis, or HIV infection.1

Table 1

Differences in Alzheimer’s, Lewy body, and vascular dementias

| Alzheimer’s dementia | Lewy body dementia | Vascular dementia |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual onset and chronic cognitive decline Memory difficulty combined with apraxia, aphasia, agnosia, or executive dysfunction | Cognitive, memory changes with one or more of the following:

| Early findings often include depression or personality changes, plus incontinence and gait disorder |

| Psychosis common in middle to late stages | Visual hallucinations, other psychoses in early stages Periods of marked delirium, “sundowning” | Temporal relationship between stroke and dementia onset, but variability in course |

| Day-to-day cognitive performance stable | Cognitive performance fluctuates during early stages. | Day-to-day cognitive performance stable |

| Parkinsonism not apparent in early stages, may present in middle to late stages | Parkinsonism in early stages Tremor not common | Gait disorder and parkinsonism common, especially with basal ganglia infarcts |

| Neurologic signs present in late stages | Exquisite sensitivity to neuroleptic therapy | Increased sensitivity to neuroleptics |

| Cannot be explained as vascular or mixed-type dementia | Cannot be explained as vascular or mixed-type dementia | Imaging necessary to document cerebrovascular disease |

With a thorough history and laboratory testing, a diagnosis of “probable” AD can be as much as 85% accurate. Probable AD is characterized by progressive gradual decline of cognitive functions affecting memory and at least one other domain including executive dysfunction, apraxia, aphasia, and/or agnosia. These deficits must cause significant functional impairment.

Neurologic test results may support AD diagnosis after ruling out reversible causes of dementia. Neuropsychological testing can provide valuable early information when subtle findings cannot be ascertained on clinical screening. (For a listing of neuropsychological tests, see this article at currentpsychiatry.com.)

Diagnosis: An unpredictable patient

Ms. A received a CBC; comprehensive metabolic panel; urinalysis; screens for rapid plasma reagin, B12, folate, and homocysteine levels; and a brain MRI. Hemoglobin and serum albumin were mildly depressed, reflecting early malnutrition. MRI showed generalized cerebral atrophy. Significant vascular disease was not identified.

Ms. A was diagnosed as having probable Alzheimer’s-type dementia based on the test results and the fact that her cognition was steadily declining. Other explanatory mechanisms were absent. She did not exhibit hallucinatory psychosis or fluctuating consciousness, which would signal Lewy body dementia.

Table 2

Medications for treating agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia

| Drug | Supporting evidence | Recommended dosage (mg/d)* | Rationale | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants | ||||

| Carbamazepine | Tariot et al2 | 200 to 1,200 mg/d in divided doses | Commonly used for impulse control disorders | Agranulocytosis, hyponatremia, liver toxicity (all rare) |

| Divalproex | Loy and Tariot3 | 250 to 2,000 mg/d | Increasing evidence points to neuroprotective qualities | Possible white blood cell suppression, liver toxicity, pancreatitis (all rare) |

| Gabapentin | Roane et al4 | 100 to 1,200 mg/d | Safe in patients with hepatic dysfunction | Scant data on use in Alzheimer’s disease |

| Lamotrigine | Tekin et al5 | Start at 25 mg/d; titrate slowly to 50 to 200 mg/d | Possibly neuroprotective via N-methyl-D-aspartate mechanism | Rapid titration may cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| Atypical antipsychotics | ||||

| Olanzapine | Street et al6 | 2.5 to 10 mg/d | Sedating effects may aid sleep | Anticholinergic effects may increase confusion, compound cognitive deficit |

| Quetiapine | Tariot et al7 | 25 to 300 mg/d | Tolerable Sedating effects may aid sleep | Watch for orthostasis, especially at higher dosages |

| Risperidone | DeVane et al8 | 0.25 to 3 mg/d | Strong data support use | High orthostatic potential, possible extrapyramidal symptoms with higher dosages |

| Ziprasidone | None | Oral:20to80mgbid IM: 10 to 20 mg, maximum 40 mg over 24 hours | Effective in managing agitation | No controlled trials, case reports in AD-associated agitation |

| SSRIs | ||||

| Citalopram | Pollock et al9 | 10 to 40 mg/d | Minimal CYP-2D6 inhibition | Effect may take 2 to 4 weeks |

| Sertraline | Lyketsos et al10 | 25 to 200 mg/d | Minimal CYP-2D6 inhibition | Effect may take 2 to 4 weeks |

| * No specific, widely accepted dosing guidelines exist for patients age > 65, but this group often does not tolerate higher dosages. | ||||

| SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||||

| IM: Intramuscula | ||||

The psychiatrist started galantamine, 4 mg bid, and vitamin E, 400 IU bid, to maximize her cognition and attempt to slow her functional decline. Ms. A, who was in an assisted living facility when we evaluated her, was transferred to the facility’s nursing section shortly afterward.

At follow-up 3 weeks later, Ms. A’s behavior improved moderately, but she remained unpredictable and intermittently agitated. Staff reported that she was physically assaulting caregivers two to three times weekly.

Which medication(s) would you use to control Ms. A’s agitation and paranoia?

- an SSRI

- a mood stabilizer

- an atypical antipsychotic

- a combination or two or more of these drug classes

The authors’ observations

Aside from controlling agitation, medication treatment in AD should slow cognitive decline, improve behavior, help the patient perform daily activities, and delay nursing home placement.

- Watch for drug-drug interactions. Many patients with AD also are taking medications for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, arthritis, and other medical comorbidities.

- Start low and go slow. Older patients generally do not tolerate rapid dos-ing adjustments as well as younger patients (Table 2).

SSRIS. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors increase serotonin at the synaptic terminal. Serotonin has long been associated with impulsivity and aggression, and decreased 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid, a metabolite of serotonin, has been found in violent criminals and in psychiatric patients who have demonstrated inward or outward aggression.11

SSRIs generally are tolerable, safe, effective, and have little cholinergic blockade. Citalopram and sertraline minimally inhibit the cytochrome P-450 2D6 isoenzyme and have lower proteinbinding affinities than fluoxetine or paroxetine. Thus, citalopram and sertraline are less likely to alter therapeutic levels of highly bound medications through displacement of either drug’s protein-bound portion.10

Anticonvulsants with mood-stabilizing effects are another option. Reasonably strong data support use of divalproex for managing agitation in AD, either as a first-line agent or as an adjunct after failed SSRI therapy. Unlike other anticonvulsants, divalproex also may be neuroprotective.3

Divalproex, however, is associated with white blood cell suppression, significant liver toxicity, and pancreatitis, although these effects are rare.13 Monitor white blood cell counts and liver enzymes early in treatment, even if divalproex blood levels below the standard reference range produce a response.14

Though not studied specifically for treating agitation in AD, carbamazepine has demonstrated significant short-term efficacy in treating dementia-related agitation and aggression.2 Scant data support use of gabapentin or lamotrigine in Alzheimer’s dementia, but these agents are often used to manage agitation in other disorders.

Atypical antipsychotics. Psychosis usually occurs in middle-to-late-stage AD but can occur at any point. If psychosis occurs early, rule out Lewy body dementia.15

Choose an atypical antipsychotic that exhibits rapid dopamine receptor dissociation constants to reduce the risk of extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and cognitive decline with prolonged use. Quetiapine has shown efficacy for treating behavioral problems in Alzheimer’s and Lewy body dementia,7 and its sedating effects may help regulate sleep-wake cycles.

Data support use of olanzapine for agitation in AD,6 but watch for anticholinergic effects including worsening of cognition. Fast-dissolving olanzapine and risperidone oral wafers may help circumvent dosing difficulties in patients who cannot swallow—or will not take—their medication. Intramuscular olanzapine and ziprasidone have shown efficacy in treating acute agitation, but no systematic studies have examined their use in agitation secondary to dementia.

Recent data suggest a modestly increased risk of cerebrovascular accidents in AD patients taking atypicals compared with placebo, but the absolute rate of such events remains low.

Treatment: 3 months of stability

Ms. A’s galantamine dosage was increased to 8 mg bid and sertraline—25 mg/d for 7 days, then 50 mg/d—was added in an effort to better control her agitation, but the behavior continued unabated for 2 weeks. Divalproex, 125 mg bid titrated over 4 weeks to 750 mg/d, was added. Still, her agitation persisted.

Over the next 4 to 6 weeks, Ms. A showed signs of psychosis, often talking to herself and occasionally reporting “people attacking me.” She became paranoid toward members of her church, who she said were “trying to hurt” her. The paranoia intensified her agitation and disrupted her sleep. Physical examination was unremarkable, as were chest X-ray and urinalysis.

Sertraline and divalproex were gradually discontinued. Quetiapine—25 mg nightly, titrated across 2 weeks to 150 mg nightly—was started. Ms. A’s agitation and psychosis decreased with quetiapine titration, and her sleep improved. Her paranoid delusions remained but no longer impeded functioning or prompted a violent reaction.

Then after remaining stable for about 3 months, Ms. A’s paranoid delusions worsened and her agitation increased.

What treatment options are available at this point?

The authors’ observations

Treating agitation and delaying nursing home placement for patients with AD is challenging. When faced with inadequate or no response, consider less-conventional alternatives.

Vitamin E and selegiline were found separately to postpone functional decline in ambulatory patients with moderately severe AD, but the agents given together were less effective than either agent alone.16

Use of methylphenidate,17 buspirone,18 clonazepam,19 zolpidem,20 and—most recently— memantine21 for AD-related agitation also has been described.

Continued treatment: Medication changes

Quetiapine was increased to 350 mg nightly across 4 weeks, resulting in mild to moderate improvement. The higher dosage did not significantly worsen rigidity or motor function, and Ms. A tolerated the increased dosage without clinical orthostasis.

Memantine was added to address Ms. A’s agitation and preserve function. The agent was started at 5 mg/d and titrated across 4 weeks to 10 mg bid.

On clinical exam, Ms. A was more calm and directable and required less intervention. Her paranoia also decreased, allowing improved interaction with family, caregivers, and others. Ms. A remains stable on memantine, 10 mg bid; galantamine, 8 mg; quetiapine, 350 mg nightly; and vitamin E, 400 IU bid. Her cognitive ability has gradually declined over the past 18 months, as evidenced by her most recent MMSE score of 16/30.

Related resources

- Cummings JL. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors in clinical practice: evidence-based recommendations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:131-45.

- Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center, a service of the National Institute on Aging. http://www.alzheimers.org.

- Paleacu D, Mazeh D, Mirecki I, et al. Donepezil for the treatment of behavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 2002;25:313-7.

- Tariot PN, Loy R, Ryan JM, et al. Mood stabilizers in Alzheimer’s disease: symptomatic and neuroprotective rationales. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2002;54:1567-77.

Drug brand names

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex • Depakote, DepakoteER

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Galantamine • Reminyl

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Memantine • Namenda

- Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone wafers • RisperdalM-Tabs

- Rivastigmine • Exelon

- Selegiline • Eldepryl

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosure

Dr. Goforth is a speaker for Pfizer Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals, and BristolMyers Squibb Co., and has received grant support from Pfizer Inc. He has also received support from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry through the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Dr. Rao is a speaker for Pfizer Inc.

Drs. Raval and Ruth report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Presenting symptoms: Marital memories

Ms. A, age 83, has been experiencing increasing confusion, agitation, and memory loss across 4 to 5 years. Family members say her memory loss has become prominent within the last year. She can no longer cook, manage her finances, shop, or perform other basic activities. At times she does not recognize her husband of 62 years and needs help with bathing and grooming.

Ms. A’s Folstein Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score is 18, indicating moderate dementia. She exhibits disorientation, diminished short-term memory, impaired attention including apraxia, and executive dysfunction. Her Geriatric Depression Scale (15-item short form) score indicates normal mood.

A neurologic exam reveals mild parkinsonism, including mild bilateral upper-extremity cogwheeltype rigidity and questionable frontal release signs including a possible mild bilateral grasp reflex. No snout reflex was seen.

This presentation suggests Ms. A has:

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Lewy body dementia

- or vascular dementia

The authors’ observations:

Differentiating among Alzheimer’s, Lewy body, and vascular dementias is important (Table 1), as their treatments and clinical courses differ.

The initial workup’s goal is to diagnose a reversible medical condition that may be hastening cognitive decline. Brain imaging (CT or MRI) can uncover cerebrovascular disease, subdural hematomas, normal-pressure hydrocephalus, tumors, or other cerebral diseases. Laboratory tests can reveal systemic conditions such as hypothyroidism, vitamin B12 deficiency, hypercalcemia, neurosyphilis, or HIV infection.1

Table 1

Differences in Alzheimer’s, Lewy body, and vascular dementias

| Alzheimer’s dementia | Lewy body dementia | Vascular dementia |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual onset and chronic cognitive decline Memory difficulty combined with apraxia, aphasia, agnosia, or executive dysfunction | Cognitive, memory changes with one or more of the following:

| Early findings often include depression or personality changes, plus incontinence and gait disorder |

| Psychosis common in middle to late stages | Visual hallucinations, other psychoses in early stages Periods of marked delirium, “sundowning” | Temporal relationship between stroke and dementia onset, but variability in course |

| Day-to-day cognitive performance stable | Cognitive performance fluctuates during early stages. | Day-to-day cognitive performance stable |

| Parkinsonism not apparent in early stages, may present in middle to late stages | Parkinsonism in early stages Tremor not common | Gait disorder and parkinsonism common, especially with basal ganglia infarcts |

| Neurologic signs present in late stages | Exquisite sensitivity to neuroleptic therapy | Increased sensitivity to neuroleptics |

| Cannot be explained as vascular or mixed-type dementia | Cannot be explained as vascular or mixed-type dementia | Imaging necessary to document cerebrovascular disease |

With a thorough history and laboratory testing, a diagnosis of “probable” AD can be as much as 85% accurate. Probable AD is characterized by progressive gradual decline of cognitive functions affecting memory and at least one other domain including executive dysfunction, apraxia, aphasia, and/or agnosia. These deficits must cause significant functional impairment.

Neurologic test results may support AD diagnosis after ruling out reversible causes of dementia. Neuropsychological testing can provide valuable early information when subtle findings cannot be ascertained on clinical screening. (For a listing of neuropsychological tests, see this article at currentpsychiatry.com.)

Diagnosis: An unpredictable patient

Ms. A received a CBC; comprehensive metabolic panel; urinalysis; screens for rapid plasma reagin, B12, folate, and homocysteine levels; and a brain MRI. Hemoglobin and serum albumin were mildly depressed, reflecting early malnutrition. MRI showed generalized cerebral atrophy. Significant vascular disease was not identified.

Ms. A was diagnosed as having probable Alzheimer’s-type dementia based on the test results and the fact that her cognition was steadily declining. Other explanatory mechanisms were absent. She did not exhibit hallucinatory psychosis or fluctuating consciousness, which would signal Lewy body dementia.

Table 2

Medications for treating agitation in Alzheimer’s dementia

| Drug | Supporting evidence | Recommended dosage (mg/d)* | Rationale | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anticonvulsants | ||||

| Carbamazepine | Tariot et al2 | 200 to 1,200 mg/d in divided doses | Commonly used for impulse control disorders | Agranulocytosis, hyponatremia, liver toxicity (all rare) |

| Divalproex | Loy and Tariot3 | 250 to 2,000 mg/d | Increasing evidence points to neuroprotective qualities | Possible white blood cell suppression, liver toxicity, pancreatitis (all rare) |

| Gabapentin | Roane et al4 | 100 to 1,200 mg/d | Safe in patients with hepatic dysfunction | Scant data on use in Alzheimer’s disease |

| Lamotrigine | Tekin et al5 | Start at 25 mg/d; titrate slowly to 50 to 200 mg/d | Possibly neuroprotective via N-methyl-D-aspartate mechanism | Rapid titration may cause Stevens-Johnson syndrome |

| Atypical antipsychotics | ||||

| Olanzapine | Street et al6 | 2.5 to 10 mg/d | Sedating effects may aid sleep | Anticholinergic effects may increase confusion, compound cognitive deficit |

| Quetiapine | Tariot et al7 | 25 to 300 mg/d | Tolerable Sedating effects may aid sleep | Watch for orthostasis, especially at higher dosages |

| Risperidone | DeVane et al8 | 0.25 to 3 mg/d | Strong data support use | High orthostatic potential, possible extrapyramidal symptoms with higher dosages |

| Ziprasidone | None | Oral:20to80mgbid IM: 10 to 20 mg, maximum 40 mg over 24 hours | Effective in managing agitation | No controlled trials, case reports in AD-associated agitation |

| SSRIs | ||||

| Citalopram | Pollock et al9 | 10 to 40 mg/d | Minimal CYP-2D6 inhibition | Effect may take 2 to 4 weeks |

| Sertraline | Lyketsos et al10 | 25 to 200 mg/d | Minimal CYP-2D6 inhibition | Effect may take 2 to 4 weeks |

| * No specific, widely accepted dosing guidelines exist for patients age > 65, but this group often does not tolerate higher dosages. | ||||

| SSRI: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | ||||

| IM: Intramuscula | ||||

The psychiatrist started galantamine, 4 mg bid, and vitamin E, 400 IU bid, to maximize her cognition and attempt to slow her functional decline. Ms. A, who was in an assisted living facility when we evaluated her, was transferred to the facility’s nursing section shortly afterward.

At follow-up 3 weeks later, Ms. A’s behavior improved moderately, but she remained unpredictable and intermittently agitated. Staff reported that she was physically assaulting caregivers two to three times weekly.

Which medication(s) would you use to control Ms. A’s agitation and paranoia?

- an SSRI

- a mood stabilizer

- an atypical antipsychotic

- a combination or two or more of these drug classes

The authors’ observations

Aside from controlling agitation, medication treatment in AD should slow cognitive decline, improve behavior, help the patient perform daily activities, and delay nursing home placement.

- Watch for drug-drug interactions. Many patients with AD also are taking medications for hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, arthritis, and other medical comorbidities.

- Start low and go slow. Older patients generally do not tolerate rapid dos-ing adjustments as well as younger patients (Table 2).

SSRIS. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors increase serotonin at the synaptic terminal. Serotonin has long been associated with impulsivity and aggression, and decreased 5-hydroxyindole acetic acid, a metabolite of serotonin, has been found in violent criminals and in psychiatric patients who have demonstrated inward or outward aggression.11

SSRIs generally are tolerable, safe, effective, and have little cholinergic blockade. Citalopram and sertraline minimally inhibit the cytochrome P-450 2D6 isoenzyme and have lower proteinbinding affinities than fluoxetine or paroxetine. Thus, citalopram and sertraline are less likely to alter therapeutic levels of highly bound medications through displacement of either drug’s protein-bound portion.10

Anticonvulsants with mood-stabilizing effects are another option. Reasonably strong data support use of divalproex for managing agitation in AD, either as a first-line agent or as an adjunct after failed SSRI therapy. Unlike other anticonvulsants, divalproex also may be neuroprotective.3

Divalproex, however, is associated with white blood cell suppression, significant liver toxicity, and pancreatitis, although these effects are rare.13 Monitor white blood cell counts and liver enzymes early in treatment, even if divalproex blood levels below the standard reference range produce a response.14

Though not studied specifically for treating agitation in AD, carbamazepine has demonstrated significant short-term efficacy in treating dementia-related agitation and aggression.2 Scant data support use of gabapentin or lamotrigine in Alzheimer’s dementia, but these agents are often used to manage agitation in other disorders.

Atypical antipsychotics. Psychosis usually occurs in middle-to-late-stage AD but can occur at any point. If psychosis occurs early, rule out Lewy body dementia.15

Choose an atypical antipsychotic that exhibits rapid dopamine receptor dissociation constants to reduce the risk of extrapyramidal symptoms, tardive dyskinesia, and cognitive decline with prolonged use. Quetiapine has shown efficacy for treating behavioral problems in Alzheimer’s and Lewy body dementia,7 and its sedating effects may help regulate sleep-wake cycles.

Data support use of olanzapine for agitation in AD,6 but watch for anticholinergic effects including worsening of cognition. Fast-dissolving olanzapine and risperidone oral wafers may help circumvent dosing difficulties in patients who cannot swallow—or will not take—their medication. Intramuscular olanzapine and ziprasidone have shown efficacy in treating acute agitation, but no systematic studies have examined their use in agitation secondary to dementia.

Recent data suggest a modestly increased risk of cerebrovascular accidents in AD patients taking atypicals compared with placebo, but the absolute rate of such events remains low.

Treatment: 3 months of stability

Ms. A’s galantamine dosage was increased to 8 mg bid and sertraline—25 mg/d for 7 days, then 50 mg/d—was added in an effort to better control her agitation, but the behavior continued unabated for 2 weeks. Divalproex, 125 mg bid titrated over 4 weeks to 750 mg/d, was added. Still, her agitation persisted.

Over the next 4 to 6 weeks, Ms. A showed signs of psychosis, often talking to herself and occasionally reporting “people attacking me.” She became paranoid toward members of her church, who she said were “trying to hurt” her. The paranoia intensified her agitation and disrupted her sleep. Physical examination was unremarkable, as were chest X-ray and urinalysis.

Sertraline and divalproex were gradually discontinued. Quetiapine—25 mg nightly, titrated across 2 weeks to 150 mg nightly—was started. Ms. A’s agitation and psychosis decreased with quetiapine titration, and her sleep improved. Her paranoid delusions remained but no longer impeded functioning or prompted a violent reaction.

Then after remaining stable for about 3 months, Ms. A’s paranoid delusions worsened and her agitation increased.

What treatment options are available at this point?

The authors’ observations

Treating agitation and delaying nursing home placement for patients with AD is challenging. When faced with inadequate or no response, consider less-conventional alternatives.

Vitamin E and selegiline were found separately to postpone functional decline in ambulatory patients with moderately severe AD, but the agents given together were less effective than either agent alone.16

Use of methylphenidate,17 buspirone,18 clonazepam,19 zolpidem,20 and—most recently— memantine21 for AD-related agitation also has been described.

Continued treatment: Medication changes

Quetiapine was increased to 350 mg nightly across 4 weeks, resulting in mild to moderate improvement. The higher dosage did not significantly worsen rigidity or motor function, and Ms. A tolerated the increased dosage without clinical orthostasis.

Memantine was added to address Ms. A’s agitation and preserve function. The agent was started at 5 mg/d and titrated across 4 weeks to 10 mg bid.

On clinical exam, Ms. A was more calm and directable and required less intervention. Her paranoia also decreased, allowing improved interaction with family, caregivers, and others. Ms. A remains stable on memantine, 10 mg bid; galantamine, 8 mg; quetiapine, 350 mg nightly; and vitamin E, 400 IU bid. Her cognitive ability has gradually declined over the past 18 months, as evidenced by her most recent MMSE score of 16/30.

Related resources

- Cummings JL. Use of cholinesterase inhibitors in clinical practice: evidence-based recommendations. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003; 11:131-45.

- Alzheimer’s Disease Education and Referral Center, a service of the National Institute on Aging. http://www.alzheimers.org.

- Paleacu D, Mazeh D, Mirecki I, et al. Donepezil for the treatment of behavioral symptoms in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol 2002;25:313-7.

- Tariot PN, Loy R, Ryan JM, et al. Mood stabilizers in Alzheimer’s disease: symptomatic and neuroprotective rationales. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 2002;54:1567-77.

Drug brand names

- Buspirone • BuSpar

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clonazepam • Klonopin

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex • Depakote, DepakoteER

- Fluoxetine • Prozac

- Gabapentin • Neurontin

- Galantamine • Reminyl

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Memantine • Namenda

- Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Oxcarbazepine • Trileptal

- Paroxetine • Paxil

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone wafers • RisperdalM-Tabs

- Rivastigmine • Exelon

- Selegiline • Eldepryl

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

- Zolpidem • Ambien

Disclosure

Dr. Goforth is a speaker for Pfizer Inc., Forest Pharmaceuticals, and BristolMyers Squibb Co., and has received grant support from Pfizer Inc. He has also received support from the Bristol-Myers Squibb Fellowship in Geriatric Psychiatry through the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry.

Dr. Rao is a speaker for Pfizer Inc.

Drs. Raval and Ruth report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Askin-Edgar S, White KE, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric aspects of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementing illnesses. In: Textbook of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences (4th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002.

2. Tariot PN, Erb R, Podgorski CA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of carbamazepine for agitation and aggression in dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:54-61.

3. Loy R, Tariot PN. Neuroprotective properties of valproate: potential benefit for AD and tauopathies. J Mol Neurosci 2002;19:303-7.

4. Roane DM, Feinberg TE, Meckler L, et al. Treatment of dementiaassociated agitation with gabapentin. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000;12:40-3.

5. Tekin S, Aykut-Bingol C, Tanridag T, Aktan S. Antiglutamatergic therapy in Alzheimer’s disease—effects of lamotrigine. J Neural Transm 1998;105:295-303.

6. Street JS, Clark WS, Kadam DL, et al. Long-term efficacy of olanzapine in the control of psychotic and behavioral symptoms in nursing home patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16(suppl 1):S62-S70.

7. Tariot PN, Ismail MS. Use of quetiapine in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(suppl 13):21-6.

8. DeVane CL, Mintzer J. Risperidone in the management of psychiatric and neurodegenerative disease in the elderly: an update. Psychopharmacol Bull 2003;37:116-32.

9. Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. Comparison of citalopram, perphenazine, and placebo for the acute treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances in hospitalized, demented patients. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:460-5.

10. Lyketsos CG, DelCampo L, Steinberg M, et al. Treating depression in Alzheimer disease: efficacy and safety of sertraline therapy, and the benefits of depression reduction: the DIADS. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:737-46.

11. Swann AC. Neuroreceptor mechanisms of aggression and its treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 4):26-35.

12. Olin JT, Schneider LS, Katz IR, et al. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;10:125-8.

13. Physician’sdesk reference(58thed). Montvale, NJ:Thomson PDR,2004.

14. Porsteinsson AP, Tariot PN, Erb R, Gaile S. An open trial of valproate for agitation in geriatric neuropsychiatric disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;5:344-51.

15. Assal F, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in the dementias. Curr Opin Neurol 2002;15:445-50.

16. Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, et al. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1216-22.

17. Kittur S, Hauser P. Improvement of sleep and behavior by methylphenidate in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1116-7.

18. Salzman C. Treatment of the agitation of late-life psychosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Psychiatry 2001;16(suppl 1):25s-28s.

19. Ginsburg ML. Clonazepam for agitated patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Can J Psychiatry 1991;36:237-8.

20. Jackson CW, Pitner JK, Mintzer JE. Zolpidem for the treatment of agitation in elderly demented patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:372-3.

21. Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler A, et al. Memantine Study Group. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1333-41.

1. Askin-Edgar S, White KE, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric aspects of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementing illnesses. In: Textbook of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences (4th ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2002.

2. Tariot PN, Erb R, Podgorski CA, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of carbamazepine for agitation and aggression in dementia. Am J Psychiatry 1998;155:54-61.

3. Loy R, Tariot PN. Neuroprotective properties of valproate: potential benefit for AD and tauopathies. J Mol Neurosci 2002;19:303-7.

4. Roane DM, Feinberg TE, Meckler L, et al. Treatment of dementiaassociated agitation with gabapentin. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci 2000;12:40-3.

5. Tekin S, Aykut-Bingol C, Tanridag T, Aktan S. Antiglutamatergic therapy in Alzheimer’s disease—effects of lamotrigine. J Neural Transm 1998;105:295-303.

6. Street JS, Clark WS, Kadam DL, et al. Long-term efficacy of olanzapine in the control of psychotic and behavioral symptoms in nursing home patients with Alzheimer’s dementia. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2001;16(suppl 1):S62-S70.

7. Tariot PN, Ismail MS. Use of quetiapine in elderly patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2002;63(suppl 13):21-6.

8. DeVane CL, Mintzer J. Risperidone in the management of psychiatric and neurodegenerative disease in the elderly: an update. Psychopharmacol Bull 2003;37:116-32.

9. Pollock BG, Mulsant BH, Rosen J, et al. Comparison of citalopram, perphenazine, and placebo for the acute treatment of psychosis and behavioral disturbances in hospitalized, demented patients. Am J Psychiatry 2002;159:460-5.

10. Lyketsos CG, DelCampo L, Steinberg M, et al. Treating depression in Alzheimer disease: efficacy and safety of sertraline therapy, and the benefits of depression reduction: the DIADS. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003;60:737-46.

11. Swann AC. Neuroreceptor mechanisms of aggression and its treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64(suppl 4):26-35.

12. Olin JT, Schneider LS, Katz IR, et al. Provisional diagnostic criteria for depression of Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2002;10:125-8.

13. Physician’sdesk reference(58thed). Montvale, NJ:Thomson PDR,2004.

14. Porsteinsson AP, Tariot PN, Erb R, Gaile S. An open trial of valproate for agitation in geriatric neuropsychiatric disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 1997;5:344-51.

15. Assal F, Cummings JL. Neuropsychiatric symptoms in the dementias. Curr Opin Neurol 2002;15:445-50.

16. Sano M, Ernesto C, Thomas RG, et al. A controlled trial of selegiline, alpha-tocopherol, or both as treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. The Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study. N Engl J Med 1997;336:1216-22.

17. Kittur S, Hauser P. Improvement of sleep and behavior by methylphenidate in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry 1999;156:1116-7.

18. Salzman C. Treatment of the agitation of late-life psychosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Eur Psychiatry 2001;16(suppl 1):25s-28s.

19. Ginsburg ML. Clonazepam for agitated patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Can J Psychiatry 1991;36:237-8.

20. Jackson CW, Pitner JK, Mintzer JE. Zolpidem for the treatment of agitation in elderly demented patients. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:372-3.

21. Reisberg B, Doody R, Stoffler A, et al. Memantine Study Group. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s disease. N Engl J Med 2003;348:1333-41.

Clozapine therapy: Timing is everything

HISTORY: Six years of psychosis

Ms. G, age 37, has had paranoid schizophrenia f or 6 years, resulting in numerous hospitalizations and continuous outpatient follow-up. Her family is supportive and supervises her when she’s not hospitalized.

Though fluent in English, Ms. G—a Polish immigrant—speaks primarily in her native tongue during psychotic episodes and becomes increasingly paranoid toward neighbors. As her condition degenerates, she hears her late father’s voice criticizing her. Because of marked social withdrawal and isolation, she cannot maintain basic interpersonal skills or live independently. Her psychosis, apathy, avolition, withdrawal, and lack of focus have persisted despite trials of numerous antipsychotics, including olanzapine, 25 mg nightly for 1 month, and quetiapine, 300 mg bid for 3 weeks.

What are the drug therapy options for this patient?

The authors’ observations

“Treatment-refractory” schizophrenia has numerous definitions. One that is widely accepted but cumbersome—used in the multicenter clozapine trial1 —requires a 5-year absence of periods of good functioning in patients taking an antipsychotic at dosages equivalent to chlorpromazine, 1,000 mg/d. In that time, the patient must have received two or more antipsychotic classes for at least 6 weeks each without achieving significant relief. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) score must be at least 45, with item scores of moderate severity for two or more of the following:

- disorganization

- suspiciousness

- hallucinatory behavior

- unusual thought content.

The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Scale score must be at least 4 (moderately ill). Also, a 6-week trial of haloperidol, with a mean dosage of 60 mg/d:

- must fail to decrease the BPRS score by 20% or to below 35

- or must fail to decrease the CGI severity score to 3 (mildly ill).1

In 1990, an international study group defined treatment-refractory schizophrenia as “the presence of ongoing psychotic symptoms with substantial functional disability and/or behavioral deviances that persist in well-diagnosed persons with schizophrenia despite reasonable and customary pharmacological and psychosocial treatment that has been provided for an adequate period.”2 This definition is far more useful to clinical practice and also considers psychosocial function. Seven levels of treatment response and resistance were suggested, based on presence of positive and negative symptoms, personal and social functioning, and CGI scores.2

Meltzer3 proposed that any person not returning to his or her highest premorbid level of functioning with a tolerable antipsychotic be considered refractory and thus a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

Ms. G’s illness meets the definition of treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Her CGI score at baseline was 5—severely ill—and several medication trials at sufficient dosages failed to control her positive or negative symptoms. Upon psychotic decompensation, she required prolonged hospitalization and could no longer live independently or work. At this point, she is a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

TREATMENT: Starting clozapine

Ms. G was started on clozapine, 25 mg at night, titrated to 300 mg at bedtime.

Two weeks later, her paranoia and auditory hallucinations diminished, her interpersonal relationships improved, she was less withdrawn, her thoughts became more organized, and her range of affect expanded. She functioned at her highest level since her initial presentation based on clinical observation and family reports. Her CGI Global Improvement score at this point was 2 (much improved).

Ms. G. continued to take clozapine, 300 mg/d, for 2 years while undergoing weekly blood tests for white blood cell counts (WBC) with differentials. She did not require hospitalization for schizophrenia during this time, and her WBC count averaged between 4,000 and 4,500/mm3, well within the normal range of 3,500 to 12,000/mm3.

Then one day—after maintaining a relatively stable WBC for several weeks—a blood test revealed a WBC of 2,700/mm3. Ms. G exhibited no objective signs of immunosuppression, such as fever or infection. Still, the psychiatrist immediately discontinued clozapine.

Was the treating psychiatrist justified in immediately stopping clozapine after one low WBC reading?

The authors’ observations

Leukopenia, defined as a WBC <3,000/mm3, and agranulocytosis, defined as an absolute neutrophil count <500/mm3, are well-documented adverse reactions to clozapine. Early data on clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases prior to 1989 suggest that up to 32% were fatal,4 but relatively few cases have occurred since the Clozaril National Registry was instituted in 1977.4,5 Between 1977 and 1997, 585 clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases were reported in the United States; 19 of these were fatal, suggesting a mortality rate of 3.2% and attesting to the effectiveness of FDA-mandated WBC testing. During this period, 150,409 patients received clozapine.4

The agranulocytosis risk does not appear to be dose-related but declines substantially after the 10th week. Three out of 1,000 patients who take clozapine for 1 year are likely to develop agranulocytosis at the 3- to 6-month mark.4 Although the incidence continues to drop after month 6, it never reaches zero.4-6

Table

Life-threatening effects of clozapine and their reported frequency of occurrence

| Adverse effect | Incidence rate among clozapine users |

|---|---|

| Agranulocytosis | 3/1000 person years* at 6 months |

| Hepatitis | Less than 1% |

| Hyperglycemia with ketoacidosis | Unknown, case reports |

| Myocarditis | 5.0-96.6 cases/100,000 patient years |

| Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | Unknown, several case reports |

| Orthostasis with cardiac collapse | 1/3,000 cases |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1/3,450 person years |

| Seizures | 5% after 1 year of therapy |

| * Person year = 1 person taking medication for 1 year | |

| Source: Clozaril prescribing information. In: Physicians’ Desk Reference (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003. | |

Other severe adverse effects of clozapine include myocarditis associated with cardiac failure, orthostatic hypotension with circulatory collapse, and rhabdomyolysis (Table).4,7 Leukocytosis and eosinophilia are generally transient and self-limited but may predict agranulocytosis.8,9 The risk of seizure occurs most commonly at dosages greater than 500 mg/d.4

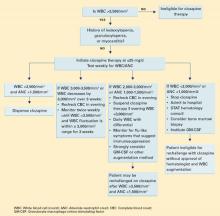

Given these potentially fatal effects, the authors’ treatment guidelines call for potential suspension of clozapine therapy when the WBC is consistently <3,000 mm3 (Algorithm).

CONTINUED TREATMENT: A difficult decision

Ms. G was switched to quetiapine, 100 mg nightly, titrated to 800 mg/d in divided doses.

Approximately 3 weeks later, Ms. G was hospitalized for renewed severe paranoia and command-type auditory hallucinations accompanied by prominent mood lability, avolition, and thought disorganization. During her 7-week hospitalization, she underwent sequential and sometimes overlapping trials of:

- ziprasidone, 160 mg bid

- risperidone, 3 mg bid

- trifluoperazine, 3 mg bid

- haloperidol, 10 mg bid

- divalproex sodium, 500 mg bid

- and carbamazepine, 400 mg bid.

None of these trials significantly improved her psychosis or mood.

At this point, the treating psychiatrists faced a difficult but clear decision: Ms. G was rechallenged on clozapine, 25 mg nightly, titrated again to 300 mg nightly. After she provided informed consent, her WBC was monitored twice daily—morning and evening—for agranulocytosis and to examine WBC patterns. Her average daily WBC counts were 4,200/mm3 in the morning and 5,500/mm3 at night. No physical signs of agranulocytosis emerged.

One week after restarting clozapine, Ms. G became less paranoid and socially more appropriate. Her thought process became increasingly organized, and after 4 weeks she reached her baseline status based upon family reports and the clinician’s CGI Global Improvement rating of 2 (much improved). Her auditory hallucinations resolved, and she was discharged to her family’s care.

Twice-daily blood testing was stopped at discharge. Ms. G continues to take clozapine and receives blood tests every 2 weeks, with no apparent signs of agranulocytosis.

Algorithm Suggested guidelines for managing WBC counts during clozapine therapy

Two treatments for clozapine-dependent agranulocytosis have been described.

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a glycoprotein that has been shown to stimulate proliferation of precursor cells in bone marrow and their differentiation into granulocytes and macrophages. Researchers have reported that GM-CSF treatment allows patients to continue taking clozapine after an episode of severe neutropenia.10-12

- Lithium salts have been reported to exploit the natural leukocytosis observed with lithium to counter clozapine-related leukopenia.13 Use of lithium to displace white blood cells has been debated, and anecdotal evidence suggests that combining lithium with clozapine may increase the chance of seizure and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.4 Still, cases reported by Adityanjee and Blier suggest that lithium augmentation is cost-effective and efficacious.14,15

How could Ms. G’s doctors have avoided stopping her clozapine therapy and her subsequent decompensation?

The authors’ observations

Aggressive blood testing and cessation of clozapine therapy are indicated when onset of granulocytopenia and agranulocytosis are suspected. Even with early detection and discontinuation, the chance of infectious disease poses a danger for up to 4 weeks until WBC levels return to normal.4

Given Ms. G’s lack of response to other antipsychotics, however, we had to consider resuming clozapine therapy. Studies have described agranulocytosis management strategies that may allow patients to keep taking clozapine despite low WBC counts (Box).

We also considered the timing of Ms. G’s blood test that showed a WBC count <2,700/mm3. Ahokas16 suggests that evening WBC counts are significantly higher than those taken in the morning and that granulocytes fluctuate in a diurnal pattern. Ms. G’s evening WBC counts were on average 1,300/mm3 higher than morning levels. Allowing for this diurnal variation and comparing evening blood samples could have averted the interruption in Ms. G’s clozapine therapy and prevented relapse in a patient with highly treatment-refractory schizophrenia.

Related resources

- Chong SA, Remington G. Clozapine augmentation: safety and efficacy. Schizophr Bull 2000;26:421-40.

- Emsley R, Oosthuizen P. The new and evolving pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;26:141-63.

- Barnas C, Zwierzina H, Hummer M, Sperner-Unterweger B, Stern A, Fleischhacker WW. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) treatment of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry 1992;53:245-7.

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- GM-CSF—Filgrastim • Neupogen

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid, others

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Trifluoperazine • Stelazine

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

Dr. Rao is a speaker for Pfizer Inc.

Drs. Goforth, Raval, and Sharma report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment resistant schizophrenic: a double blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:789-96.

2. Brenner HD, Dencker SJ, Goldstein MJ, et al. Defining treatment refractoriness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1990;16:551-61.

3. Meltzer HY. Clozapine: is another view valid? Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:821-5.

4. Clozaril prescribing information. In: Physicians’ Desk Reference. (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003.

5. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:162-7.

6. Honigfeld G. Effects of the clozapine national registry system on incidence of deaths related to agranulocytosis. Psychiatr Serv 1996;47:52-6.

7. Scelsa SN, Simpson DM, McQuistion HL, et al. Clozapineinduced myotoxicity in patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Neurology 1996;47:1518-23.

8. Ames D, Wirshing WC, Baker RW, et al. Predictive value of eosinophilia for neutropenia during clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:579-81.

9. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ. Do white-cell count spikes predict agranulocytosis in clozapine recipients? Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31:311-14.

10. Sperner-Unterweger B, Czeipek I, Gaggl S, et al. Treatment of severe clozapine-induced neutropenia with granulocyte colonystimulating factor (G-CSF). Remission despite continuous treatment with clozapine. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172:82-4.

11. Chengappa KN, Gopalani A, Haught MK, et al. The treatment of clozapine-associated agranulocytosis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:111-21.

12. Lamberti JS, Bellnier TJ, Schwarzkopf SB, Schneider E. Filgrastim treatment of three patients with clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56:256-9.

13. Boshes RA, Manschreck TC, Desrosiers J, et al. Initiation of clozapine therapy in a patient with preexisting leukopenia: a discussion of the rationale of current treatment options. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2001;13:233-7.

14. Adityanjee. Modification of clozapine-induced leukopenia and neutropenia with lithium carbonate. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:648-9.

15. Blier P, Slater S, Measham T, et al. Lithium and clozapine-induced neutropenia/agranulocytosis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;13:137-40.

16. Ahokas A, Elonen E. Circadian rhythm of white blood cells during clozapine treatment. Psychopharmacology 1999;144:301-2.

HISTORY: Six years of psychosis

Ms. G, age 37, has had paranoid schizophrenia f or 6 years, resulting in numerous hospitalizations and continuous outpatient follow-up. Her family is supportive and supervises her when she’s not hospitalized.

Though fluent in English, Ms. G—a Polish immigrant—speaks primarily in her native tongue during psychotic episodes and becomes increasingly paranoid toward neighbors. As her condition degenerates, she hears her late father’s voice criticizing her. Because of marked social withdrawal and isolation, she cannot maintain basic interpersonal skills or live independently. Her psychosis, apathy, avolition, withdrawal, and lack of focus have persisted despite trials of numerous antipsychotics, including olanzapine, 25 mg nightly for 1 month, and quetiapine, 300 mg bid for 3 weeks.

What are the drug therapy options for this patient?

The authors’ observations

“Treatment-refractory” schizophrenia has numerous definitions. One that is widely accepted but cumbersome—used in the multicenter clozapine trial1 —requires a 5-year absence of periods of good functioning in patients taking an antipsychotic at dosages equivalent to chlorpromazine, 1,000 mg/d. In that time, the patient must have received two or more antipsychotic classes for at least 6 weeks each without achieving significant relief. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) score must be at least 45, with item scores of moderate severity for two or more of the following:

- disorganization

- suspiciousness

- hallucinatory behavior

- unusual thought content.

The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Scale score must be at least 4 (moderately ill). Also, a 6-week trial of haloperidol, with a mean dosage of 60 mg/d:

- must fail to decrease the BPRS score by 20% or to below 35

- or must fail to decrease the CGI severity score to 3 (mildly ill).1

In 1990, an international study group defined treatment-refractory schizophrenia as “the presence of ongoing psychotic symptoms with substantial functional disability and/or behavioral deviances that persist in well-diagnosed persons with schizophrenia despite reasonable and customary pharmacological and psychosocial treatment that has been provided for an adequate period.”2 This definition is far more useful to clinical practice and also considers psychosocial function. Seven levels of treatment response and resistance were suggested, based on presence of positive and negative symptoms, personal and social functioning, and CGI scores.2

Meltzer3 proposed that any person not returning to his or her highest premorbid level of functioning with a tolerable antipsychotic be considered refractory and thus a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

Ms. G’s illness meets the definition of treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Her CGI score at baseline was 5—severely ill—and several medication trials at sufficient dosages failed to control her positive or negative symptoms. Upon psychotic decompensation, she required prolonged hospitalization and could no longer live independently or work. At this point, she is a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

TREATMENT: Starting clozapine

Ms. G was started on clozapine, 25 mg at night, titrated to 300 mg at bedtime.

Two weeks later, her paranoia and auditory hallucinations diminished, her interpersonal relationships improved, she was less withdrawn, her thoughts became more organized, and her range of affect expanded. She functioned at her highest level since her initial presentation based on clinical observation and family reports. Her CGI Global Improvement score at this point was 2 (much improved).

Ms. G. continued to take clozapine, 300 mg/d, for 2 years while undergoing weekly blood tests for white blood cell counts (WBC) with differentials. She did not require hospitalization for schizophrenia during this time, and her WBC count averaged between 4,000 and 4,500/mm3, well within the normal range of 3,500 to 12,000/mm3.

Then one day—after maintaining a relatively stable WBC for several weeks—a blood test revealed a WBC of 2,700/mm3. Ms. G exhibited no objective signs of immunosuppression, such as fever or infection. Still, the psychiatrist immediately discontinued clozapine.

Was the treating psychiatrist justified in immediately stopping clozapine after one low WBC reading?

The authors’ observations

Leukopenia, defined as a WBC <3,000/mm3, and agranulocytosis, defined as an absolute neutrophil count <500/mm3, are well-documented adverse reactions to clozapine. Early data on clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases prior to 1989 suggest that up to 32% were fatal,4 but relatively few cases have occurred since the Clozaril National Registry was instituted in 1977.4,5 Between 1977 and 1997, 585 clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases were reported in the United States; 19 of these were fatal, suggesting a mortality rate of 3.2% and attesting to the effectiveness of FDA-mandated WBC testing. During this period, 150,409 patients received clozapine.4

The agranulocytosis risk does not appear to be dose-related but declines substantially after the 10th week. Three out of 1,000 patients who take clozapine for 1 year are likely to develop agranulocytosis at the 3- to 6-month mark.4 Although the incidence continues to drop after month 6, it never reaches zero.4-6

Table

Life-threatening effects of clozapine and their reported frequency of occurrence

| Adverse effect | Incidence rate among clozapine users |

|---|---|

| Agranulocytosis | 3/1000 person years* at 6 months |

| Hepatitis | Less than 1% |

| Hyperglycemia with ketoacidosis | Unknown, case reports |

| Myocarditis | 5.0-96.6 cases/100,000 patient years |

| Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | Unknown, several case reports |

| Orthostasis with cardiac collapse | 1/3,000 cases |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1/3,450 person years |

| Seizures | 5% after 1 year of therapy |

| * Person year = 1 person taking medication for 1 year | |

| Source: Clozaril prescribing information. In: Physicians’ Desk Reference (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003. | |

Other severe adverse effects of clozapine include myocarditis associated with cardiac failure, orthostatic hypotension with circulatory collapse, and rhabdomyolysis (Table).4,7 Leukocytosis and eosinophilia are generally transient and self-limited but may predict agranulocytosis.8,9 The risk of seizure occurs most commonly at dosages greater than 500 mg/d.4

Given these potentially fatal effects, the authors’ treatment guidelines call for potential suspension of clozapine therapy when the WBC is consistently <3,000 mm3 (Algorithm).

CONTINUED TREATMENT: A difficult decision

Ms. G was switched to quetiapine, 100 mg nightly, titrated to 800 mg/d in divided doses.

Approximately 3 weeks later, Ms. G was hospitalized for renewed severe paranoia and command-type auditory hallucinations accompanied by prominent mood lability, avolition, and thought disorganization. During her 7-week hospitalization, she underwent sequential and sometimes overlapping trials of:

- ziprasidone, 160 mg bid

- risperidone, 3 mg bid

- trifluoperazine, 3 mg bid

- haloperidol, 10 mg bid

- divalproex sodium, 500 mg bid

- and carbamazepine, 400 mg bid.

None of these trials significantly improved her psychosis or mood.

At this point, the treating psychiatrists faced a difficult but clear decision: Ms. G was rechallenged on clozapine, 25 mg nightly, titrated again to 300 mg nightly. After she provided informed consent, her WBC was monitored twice daily—morning and evening—for agranulocytosis and to examine WBC patterns. Her average daily WBC counts were 4,200/mm3 in the morning and 5,500/mm3 at night. No physical signs of agranulocytosis emerged.

One week after restarting clozapine, Ms. G became less paranoid and socially more appropriate. Her thought process became increasingly organized, and after 4 weeks she reached her baseline status based upon family reports and the clinician’s CGI Global Improvement rating of 2 (much improved). Her auditory hallucinations resolved, and she was discharged to her family’s care.

Twice-daily blood testing was stopped at discharge. Ms. G continues to take clozapine and receives blood tests every 2 weeks, with no apparent signs of agranulocytosis.

Algorithm Suggested guidelines for managing WBC counts during clozapine therapy

Two treatments for clozapine-dependent agranulocytosis have been described.

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a glycoprotein that has been shown to stimulate proliferation of precursor cells in bone marrow and their differentiation into granulocytes and macrophages. Researchers have reported that GM-CSF treatment allows patients to continue taking clozapine after an episode of severe neutropenia.10-12