User login

Clozapine therapy: Timing is everything

HISTORY: Six years of psychosis

Ms. G, age 37, has had paranoid schizophrenia f or 6 years, resulting in numerous hospitalizations and continuous outpatient follow-up. Her family is supportive and supervises her when she’s not hospitalized.

Though fluent in English, Ms. G—a Polish immigrant—speaks primarily in her native tongue during psychotic episodes and becomes increasingly paranoid toward neighbors. As her condition degenerates, she hears her late father’s voice criticizing her. Because of marked social withdrawal and isolation, she cannot maintain basic interpersonal skills or live independently. Her psychosis, apathy, avolition, withdrawal, and lack of focus have persisted despite trials of numerous antipsychotics, including olanzapine, 25 mg nightly for 1 month, and quetiapine, 300 mg bid for 3 weeks.

What are the drug therapy options for this patient?

The authors’ observations

“Treatment-refractory” schizophrenia has numerous definitions. One that is widely accepted but cumbersome—used in the multicenter clozapine trial1 —requires a 5-year absence of periods of good functioning in patients taking an antipsychotic at dosages equivalent to chlorpromazine, 1,000 mg/d. In that time, the patient must have received two or more antipsychotic classes for at least 6 weeks each without achieving significant relief. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) score must be at least 45, with item scores of moderate severity for two or more of the following:

- disorganization

- suspiciousness

- hallucinatory behavior

- unusual thought content.

The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Scale score must be at least 4 (moderately ill). Also, a 6-week trial of haloperidol, with a mean dosage of 60 mg/d:

- must fail to decrease the BPRS score by 20% or to below 35

- or must fail to decrease the CGI severity score to 3 (mildly ill).1

In 1990, an international study group defined treatment-refractory schizophrenia as “the presence of ongoing psychotic symptoms with substantial functional disability and/or behavioral deviances that persist in well-diagnosed persons with schizophrenia despite reasonable and customary pharmacological and psychosocial treatment that has been provided for an adequate period.”2 This definition is far more useful to clinical practice and also considers psychosocial function. Seven levels of treatment response and resistance were suggested, based on presence of positive and negative symptoms, personal and social functioning, and CGI scores.2

Meltzer3 proposed that any person not returning to his or her highest premorbid level of functioning with a tolerable antipsychotic be considered refractory and thus a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

Ms. G’s illness meets the definition of treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Her CGI score at baseline was 5—severely ill—and several medication trials at sufficient dosages failed to control her positive or negative symptoms. Upon psychotic decompensation, she required prolonged hospitalization and could no longer live independently or work. At this point, she is a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

TREATMENT: Starting clozapine

Ms. G was started on clozapine, 25 mg at night, titrated to 300 mg at bedtime.

Two weeks later, her paranoia and auditory hallucinations diminished, her interpersonal relationships improved, she was less withdrawn, her thoughts became more organized, and her range of affect expanded. She functioned at her highest level since her initial presentation based on clinical observation and family reports. Her CGI Global Improvement score at this point was 2 (much improved).

Ms. G. continued to take clozapine, 300 mg/d, for 2 years while undergoing weekly blood tests for white blood cell counts (WBC) with differentials. She did not require hospitalization for schizophrenia during this time, and her WBC count averaged between 4,000 and 4,500/mm3, well within the normal range of 3,500 to 12,000/mm3.

Then one day—after maintaining a relatively stable WBC for several weeks—a blood test revealed a WBC of 2,700/mm3. Ms. G exhibited no objective signs of immunosuppression, such as fever or infection. Still, the psychiatrist immediately discontinued clozapine.

Was the treating psychiatrist justified in immediately stopping clozapine after one low WBC reading?

The authors’ observations

Leukopenia, defined as a WBC <3,000/mm3, and agranulocytosis, defined as an absolute neutrophil count <500/mm3, are well-documented adverse reactions to clozapine. Early data on clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases prior to 1989 suggest that up to 32% were fatal,4 but relatively few cases have occurred since the Clozaril National Registry was instituted in 1977.4,5 Between 1977 and 1997, 585 clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases were reported in the United States; 19 of these were fatal, suggesting a mortality rate of 3.2% and attesting to the effectiveness of FDA-mandated WBC testing. During this period, 150,409 patients received clozapine.4

The agranulocytosis risk does not appear to be dose-related but declines substantially after the 10th week. Three out of 1,000 patients who take clozapine for 1 year are likely to develop agranulocytosis at the 3- to 6-month mark.4 Although the incidence continues to drop after month 6, it never reaches zero.4-6

Table

Life-threatening effects of clozapine and their reported frequency of occurrence

| Adverse effect | Incidence rate among clozapine users |

|---|---|

| Agranulocytosis | 3/1000 person years* at 6 months |

| Hepatitis | Less than 1% |

| Hyperglycemia with ketoacidosis | Unknown, case reports |

| Myocarditis | 5.0-96.6 cases/100,000 patient years |

| Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | Unknown, several case reports |

| Orthostasis with cardiac collapse | 1/3,000 cases |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1/3,450 person years |

| Seizures | 5% after 1 year of therapy |

| * Person year = 1 person taking medication for 1 year | |

| Source: Clozaril prescribing information. In: Physicians’ Desk Reference (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003. | |

Other severe adverse effects of clozapine include myocarditis associated with cardiac failure, orthostatic hypotension with circulatory collapse, and rhabdomyolysis (Table).4,7 Leukocytosis and eosinophilia are generally transient and self-limited but may predict agranulocytosis.8,9 The risk of seizure occurs most commonly at dosages greater than 500 mg/d.4

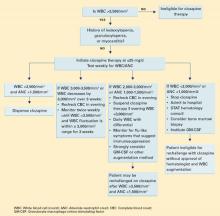

Given these potentially fatal effects, the authors’ treatment guidelines call for potential suspension of clozapine therapy when the WBC is consistently <3,000 mm3 (Algorithm).

CONTINUED TREATMENT: A difficult decision

Ms. G was switched to quetiapine, 100 mg nightly, titrated to 800 mg/d in divided doses.

Approximately 3 weeks later, Ms. G was hospitalized for renewed severe paranoia and command-type auditory hallucinations accompanied by prominent mood lability, avolition, and thought disorganization. During her 7-week hospitalization, she underwent sequential and sometimes overlapping trials of:

- ziprasidone, 160 mg bid

- risperidone, 3 mg bid

- trifluoperazine, 3 mg bid

- haloperidol, 10 mg bid

- divalproex sodium, 500 mg bid

- and carbamazepine, 400 mg bid.

None of these trials significantly improved her psychosis or mood.

At this point, the treating psychiatrists faced a difficult but clear decision: Ms. G was rechallenged on clozapine, 25 mg nightly, titrated again to 300 mg nightly. After she provided informed consent, her WBC was monitored twice daily—morning and evening—for agranulocytosis and to examine WBC patterns. Her average daily WBC counts were 4,200/mm3 in the morning and 5,500/mm3 at night. No physical signs of agranulocytosis emerged.

One week after restarting clozapine, Ms. G became less paranoid and socially more appropriate. Her thought process became increasingly organized, and after 4 weeks she reached her baseline status based upon family reports and the clinician’s CGI Global Improvement rating of 2 (much improved). Her auditory hallucinations resolved, and she was discharged to her family’s care.

Twice-daily blood testing was stopped at discharge. Ms. G continues to take clozapine and receives blood tests every 2 weeks, with no apparent signs of agranulocytosis.

Algorithm Suggested guidelines for managing WBC counts during clozapine therapy

Two treatments for clozapine-dependent agranulocytosis have been described.

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a glycoprotein that has been shown to stimulate proliferation of precursor cells in bone marrow and their differentiation into granulocytes and macrophages. Researchers have reported that GM-CSF treatment allows patients to continue taking clozapine after an episode of severe neutropenia.10-12

- Lithium salts have been reported to exploit the natural leukocytosis observed with lithium to counter clozapine-related leukopenia.13 Use of lithium to displace white blood cells has been debated, and anecdotal evidence suggests that combining lithium with clozapine may increase the chance of seizure and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.4 Still, cases reported by Adityanjee and Blier suggest that lithium augmentation is cost-effective and efficacious.14,15

How could Ms. G’s doctors have avoided stopping her clozapine therapy and her subsequent decompensation?

The authors’ observations

Aggressive blood testing and cessation of clozapine therapy are indicated when onset of granulocytopenia and agranulocytosis are suspected. Even with early detection and discontinuation, the chance of infectious disease poses a danger for up to 4 weeks until WBC levels return to normal.4

Given Ms. G’s lack of response to other antipsychotics, however, we had to consider resuming clozapine therapy. Studies have described agranulocytosis management strategies that may allow patients to keep taking clozapine despite low WBC counts (Box).

We also considered the timing of Ms. G’s blood test that showed a WBC count <2,700/mm3. Ahokas16 suggests that evening WBC counts are significantly higher than those taken in the morning and that granulocytes fluctuate in a diurnal pattern. Ms. G’s evening WBC counts were on average 1,300/mm3 higher than morning levels. Allowing for this diurnal variation and comparing evening blood samples could have averted the interruption in Ms. G’s clozapine therapy and prevented relapse in a patient with highly treatment-refractory schizophrenia.

Related resources

- Chong SA, Remington G. Clozapine augmentation: safety and efficacy. Schizophr Bull 2000;26:421-40.

- Emsley R, Oosthuizen P. The new and evolving pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;26:141-63.

- Barnas C, Zwierzina H, Hummer M, Sperner-Unterweger B, Stern A, Fleischhacker WW. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) treatment of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry 1992;53:245-7.

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- GM-CSF—Filgrastim • Neupogen

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid, others

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Trifluoperazine • Stelazine

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

Dr. Rao is a speaker for Pfizer Inc.

Drs. Goforth, Raval, and Sharma report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment resistant schizophrenic: a double blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:789-96.

2. Brenner HD, Dencker SJ, Goldstein MJ, et al. Defining treatment refractoriness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1990;16:551-61.

3. Meltzer HY. Clozapine: is another view valid? Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:821-5.

4. Clozaril prescribing information. In: Physicians’ Desk Reference. (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003.

5. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:162-7.

6. Honigfeld G. Effects of the clozapine national registry system on incidence of deaths related to agranulocytosis. Psychiatr Serv 1996;47:52-6.

7. Scelsa SN, Simpson DM, McQuistion HL, et al. Clozapineinduced myotoxicity in patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Neurology 1996;47:1518-23.

8. Ames D, Wirshing WC, Baker RW, et al. Predictive value of eosinophilia for neutropenia during clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:579-81.

9. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ. Do white-cell count spikes predict agranulocytosis in clozapine recipients? Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31:311-14.

10. Sperner-Unterweger B, Czeipek I, Gaggl S, et al. Treatment of severe clozapine-induced neutropenia with granulocyte colonystimulating factor (G-CSF). Remission despite continuous treatment with clozapine. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172:82-4.

11. Chengappa KN, Gopalani A, Haught MK, et al. The treatment of clozapine-associated agranulocytosis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:111-21.

12. Lamberti JS, Bellnier TJ, Schwarzkopf SB, Schneider E. Filgrastim treatment of three patients with clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56:256-9.

13. Boshes RA, Manschreck TC, Desrosiers J, et al. Initiation of clozapine therapy in a patient with preexisting leukopenia: a discussion of the rationale of current treatment options. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2001;13:233-7.

14. Adityanjee. Modification of clozapine-induced leukopenia and neutropenia with lithium carbonate. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:648-9.

15. Blier P, Slater S, Measham T, et al. Lithium and clozapine-induced neutropenia/agranulocytosis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;13:137-40.

16. Ahokas A, Elonen E. Circadian rhythm of white blood cells during clozapine treatment. Psychopharmacology 1999;144:301-2.

HISTORY: Six years of psychosis

Ms. G, age 37, has had paranoid schizophrenia f or 6 years, resulting in numerous hospitalizations and continuous outpatient follow-up. Her family is supportive and supervises her when she’s not hospitalized.

Though fluent in English, Ms. G—a Polish immigrant—speaks primarily in her native tongue during psychotic episodes and becomes increasingly paranoid toward neighbors. As her condition degenerates, she hears her late father’s voice criticizing her. Because of marked social withdrawal and isolation, she cannot maintain basic interpersonal skills or live independently. Her psychosis, apathy, avolition, withdrawal, and lack of focus have persisted despite trials of numerous antipsychotics, including olanzapine, 25 mg nightly for 1 month, and quetiapine, 300 mg bid for 3 weeks.

What are the drug therapy options for this patient?

The authors’ observations

“Treatment-refractory” schizophrenia has numerous definitions. One that is widely accepted but cumbersome—used in the multicenter clozapine trial1 —requires a 5-year absence of periods of good functioning in patients taking an antipsychotic at dosages equivalent to chlorpromazine, 1,000 mg/d. In that time, the patient must have received two or more antipsychotic classes for at least 6 weeks each without achieving significant relief. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) score must be at least 45, with item scores of moderate severity for two or more of the following:

- disorganization

- suspiciousness

- hallucinatory behavior

- unusual thought content.

The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Scale score must be at least 4 (moderately ill). Also, a 6-week trial of haloperidol, with a mean dosage of 60 mg/d:

- must fail to decrease the BPRS score by 20% or to below 35

- or must fail to decrease the CGI severity score to 3 (mildly ill).1

In 1990, an international study group defined treatment-refractory schizophrenia as “the presence of ongoing psychotic symptoms with substantial functional disability and/or behavioral deviances that persist in well-diagnosed persons with schizophrenia despite reasonable and customary pharmacological and psychosocial treatment that has been provided for an adequate period.”2 This definition is far more useful to clinical practice and also considers psychosocial function. Seven levels of treatment response and resistance were suggested, based on presence of positive and negative symptoms, personal and social functioning, and CGI scores.2

Meltzer3 proposed that any person not returning to his or her highest premorbid level of functioning with a tolerable antipsychotic be considered refractory and thus a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

Ms. G’s illness meets the definition of treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Her CGI score at baseline was 5—severely ill—and several medication trials at sufficient dosages failed to control her positive or negative symptoms. Upon psychotic decompensation, she required prolonged hospitalization and could no longer live independently or work. At this point, she is a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

TREATMENT: Starting clozapine

Ms. G was started on clozapine, 25 mg at night, titrated to 300 mg at bedtime.

Two weeks later, her paranoia and auditory hallucinations diminished, her interpersonal relationships improved, she was less withdrawn, her thoughts became more organized, and her range of affect expanded. She functioned at her highest level since her initial presentation based on clinical observation and family reports. Her CGI Global Improvement score at this point was 2 (much improved).

Ms. G. continued to take clozapine, 300 mg/d, for 2 years while undergoing weekly blood tests for white blood cell counts (WBC) with differentials. She did not require hospitalization for schizophrenia during this time, and her WBC count averaged between 4,000 and 4,500/mm3, well within the normal range of 3,500 to 12,000/mm3.

Then one day—after maintaining a relatively stable WBC for several weeks—a blood test revealed a WBC of 2,700/mm3. Ms. G exhibited no objective signs of immunosuppression, such as fever or infection. Still, the psychiatrist immediately discontinued clozapine.

Was the treating psychiatrist justified in immediately stopping clozapine after one low WBC reading?

The authors’ observations

Leukopenia, defined as a WBC <3,000/mm3, and agranulocytosis, defined as an absolute neutrophil count <500/mm3, are well-documented adverse reactions to clozapine. Early data on clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases prior to 1989 suggest that up to 32% were fatal,4 but relatively few cases have occurred since the Clozaril National Registry was instituted in 1977.4,5 Between 1977 and 1997, 585 clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases were reported in the United States; 19 of these were fatal, suggesting a mortality rate of 3.2% and attesting to the effectiveness of FDA-mandated WBC testing. During this period, 150,409 patients received clozapine.4

The agranulocytosis risk does not appear to be dose-related but declines substantially after the 10th week. Three out of 1,000 patients who take clozapine for 1 year are likely to develop agranulocytosis at the 3- to 6-month mark.4 Although the incidence continues to drop after month 6, it never reaches zero.4-6

Table

Life-threatening effects of clozapine and their reported frequency of occurrence

| Adverse effect | Incidence rate among clozapine users |

|---|---|

| Agranulocytosis | 3/1000 person years* at 6 months |

| Hepatitis | Less than 1% |

| Hyperglycemia with ketoacidosis | Unknown, case reports |

| Myocarditis | 5.0-96.6 cases/100,000 patient years |

| Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | Unknown, several case reports |

| Orthostasis with cardiac collapse | 1/3,000 cases |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1/3,450 person years |

| Seizures | 5% after 1 year of therapy |

| * Person year = 1 person taking medication for 1 year | |

| Source: Clozaril prescribing information. In: Physicians’ Desk Reference (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003. | |

Other severe adverse effects of clozapine include myocarditis associated with cardiac failure, orthostatic hypotension with circulatory collapse, and rhabdomyolysis (Table).4,7 Leukocytosis and eosinophilia are generally transient and self-limited but may predict agranulocytosis.8,9 The risk of seizure occurs most commonly at dosages greater than 500 mg/d.4

Given these potentially fatal effects, the authors’ treatment guidelines call for potential suspension of clozapine therapy when the WBC is consistently <3,000 mm3 (Algorithm).

CONTINUED TREATMENT: A difficult decision

Ms. G was switched to quetiapine, 100 mg nightly, titrated to 800 mg/d in divided doses.

Approximately 3 weeks later, Ms. G was hospitalized for renewed severe paranoia and command-type auditory hallucinations accompanied by prominent mood lability, avolition, and thought disorganization. During her 7-week hospitalization, she underwent sequential and sometimes overlapping trials of:

- ziprasidone, 160 mg bid

- risperidone, 3 mg bid

- trifluoperazine, 3 mg bid

- haloperidol, 10 mg bid

- divalproex sodium, 500 mg bid

- and carbamazepine, 400 mg bid.

None of these trials significantly improved her psychosis or mood.

At this point, the treating psychiatrists faced a difficult but clear decision: Ms. G was rechallenged on clozapine, 25 mg nightly, titrated again to 300 mg nightly. After she provided informed consent, her WBC was monitored twice daily—morning and evening—for agranulocytosis and to examine WBC patterns. Her average daily WBC counts were 4,200/mm3 in the morning and 5,500/mm3 at night. No physical signs of agranulocytosis emerged.

One week after restarting clozapine, Ms. G became less paranoid and socially more appropriate. Her thought process became increasingly organized, and after 4 weeks she reached her baseline status based upon family reports and the clinician’s CGI Global Improvement rating of 2 (much improved). Her auditory hallucinations resolved, and she was discharged to her family’s care.

Twice-daily blood testing was stopped at discharge. Ms. G continues to take clozapine and receives blood tests every 2 weeks, with no apparent signs of agranulocytosis.

Algorithm Suggested guidelines for managing WBC counts during clozapine therapy

Two treatments for clozapine-dependent agranulocytosis have been described.

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a glycoprotein that has been shown to stimulate proliferation of precursor cells in bone marrow and their differentiation into granulocytes and macrophages. Researchers have reported that GM-CSF treatment allows patients to continue taking clozapine after an episode of severe neutropenia.10-12

- Lithium salts have been reported to exploit the natural leukocytosis observed with lithium to counter clozapine-related leukopenia.13 Use of lithium to displace white blood cells has been debated, and anecdotal evidence suggests that combining lithium with clozapine may increase the chance of seizure and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.4 Still, cases reported by Adityanjee and Blier suggest that lithium augmentation is cost-effective and efficacious.14,15

How could Ms. G’s doctors have avoided stopping her clozapine therapy and her subsequent decompensation?

The authors’ observations

Aggressive blood testing and cessation of clozapine therapy are indicated when onset of granulocytopenia and agranulocytosis are suspected. Even with early detection and discontinuation, the chance of infectious disease poses a danger for up to 4 weeks until WBC levels return to normal.4

Given Ms. G’s lack of response to other antipsychotics, however, we had to consider resuming clozapine therapy. Studies have described agranulocytosis management strategies that may allow patients to keep taking clozapine despite low WBC counts (Box).

We also considered the timing of Ms. G’s blood test that showed a WBC count <2,700/mm3. Ahokas16 suggests that evening WBC counts are significantly higher than those taken in the morning and that granulocytes fluctuate in a diurnal pattern. Ms. G’s evening WBC counts were on average 1,300/mm3 higher than morning levels. Allowing for this diurnal variation and comparing evening blood samples could have averted the interruption in Ms. G’s clozapine therapy and prevented relapse in a patient with highly treatment-refractory schizophrenia.

Related resources

- Chong SA, Remington G. Clozapine augmentation: safety and efficacy. Schizophr Bull 2000;26:421-40.

- Emsley R, Oosthuizen P. The new and evolving pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;26:141-63.

- Barnas C, Zwierzina H, Hummer M, Sperner-Unterweger B, Stern A, Fleischhacker WW. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) treatment of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry 1992;53:245-7.

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- GM-CSF—Filgrastim • Neupogen

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid, others

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Trifluoperazine • Stelazine

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

Dr. Rao is a speaker for Pfizer Inc.

Drs. Goforth, Raval, and Sharma report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

HISTORY: Six years of psychosis

Ms. G, age 37, has had paranoid schizophrenia f or 6 years, resulting in numerous hospitalizations and continuous outpatient follow-up. Her family is supportive and supervises her when she’s not hospitalized.

Though fluent in English, Ms. G—a Polish immigrant—speaks primarily in her native tongue during psychotic episodes and becomes increasingly paranoid toward neighbors. As her condition degenerates, she hears her late father’s voice criticizing her. Because of marked social withdrawal and isolation, she cannot maintain basic interpersonal skills or live independently. Her psychosis, apathy, avolition, withdrawal, and lack of focus have persisted despite trials of numerous antipsychotics, including olanzapine, 25 mg nightly for 1 month, and quetiapine, 300 mg bid for 3 weeks.

What are the drug therapy options for this patient?

The authors’ observations

“Treatment-refractory” schizophrenia has numerous definitions. One that is widely accepted but cumbersome—used in the multicenter clozapine trial1 —requires a 5-year absence of periods of good functioning in patients taking an antipsychotic at dosages equivalent to chlorpromazine, 1,000 mg/d. In that time, the patient must have received two or more antipsychotic classes for at least 6 weeks each without achieving significant relief. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) score must be at least 45, with item scores of moderate severity for two or more of the following:

- disorganization

- suspiciousness

- hallucinatory behavior

- unusual thought content.

The Clinical Global Impression (CGI) Scale score must be at least 4 (moderately ill). Also, a 6-week trial of haloperidol, with a mean dosage of 60 mg/d:

- must fail to decrease the BPRS score by 20% or to below 35

- or must fail to decrease the CGI severity score to 3 (mildly ill).1

In 1990, an international study group defined treatment-refractory schizophrenia as “the presence of ongoing psychotic symptoms with substantial functional disability and/or behavioral deviances that persist in well-diagnosed persons with schizophrenia despite reasonable and customary pharmacological and psychosocial treatment that has been provided for an adequate period.”2 This definition is far more useful to clinical practice and also considers psychosocial function. Seven levels of treatment response and resistance were suggested, based on presence of positive and negative symptoms, personal and social functioning, and CGI scores.2

Meltzer3 proposed that any person not returning to his or her highest premorbid level of functioning with a tolerable antipsychotic be considered refractory and thus a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

Ms. G’s illness meets the definition of treatment-refractory schizophrenia. Her CGI score at baseline was 5—severely ill—and several medication trials at sufficient dosages failed to control her positive or negative symptoms. Upon psychotic decompensation, she required prolonged hospitalization and could no longer live independently or work. At this point, she is a possible candidate for clozapine therapy.

TREATMENT: Starting clozapine

Ms. G was started on clozapine, 25 mg at night, titrated to 300 mg at bedtime.

Two weeks later, her paranoia and auditory hallucinations diminished, her interpersonal relationships improved, she was less withdrawn, her thoughts became more organized, and her range of affect expanded. She functioned at her highest level since her initial presentation based on clinical observation and family reports. Her CGI Global Improvement score at this point was 2 (much improved).

Ms. G. continued to take clozapine, 300 mg/d, for 2 years while undergoing weekly blood tests for white blood cell counts (WBC) with differentials. She did not require hospitalization for schizophrenia during this time, and her WBC count averaged between 4,000 and 4,500/mm3, well within the normal range of 3,500 to 12,000/mm3.

Then one day—after maintaining a relatively stable WBC for several weeks—a blood test revealed a WBC of 2,700/mm3. Ms. G exhibited no objective signs of immunosuppression, such as fever or infection. Still, the psychiatrist immediately discontinued clozapine.

Was the treating psychiatrist justified in immediately stopping clozapine after one low WBC reading?

The authors’ observations

Leukopenia, defined as a WBC <3,000/mm3, and agranulocytosis, defined as an absolute neutrophil count <500/mm3, are well-documented adverse reactions to clozapine. Early data on clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases prior to 1989 suggest that up to 32% were fatal,4 but relatively few cases have occurred since the Clozaril National Registry was instituted in 1977.4,5 Between 1977 and 1997, 585 clozapine-associated agranulocytosis cases were reported in the United States; 19 of these were fatal, suggesting a mortality rate of 3.2% and attesting to the effectiveness of FDA-mandated WBC testing. During this period, 150,409 patients received clozapine.4

The agranulocytosis risk does not appear to be dose-related but declines substantially after the 10th week. Three out of 1,000 patients who take clozapine for 1 year are likely to develop agranulocytosis at the 3- to 6-month mark.4 Although the incidence continues to drop after month 6, it never reaches zero.4-6

Table

Life-threatening effects of clozapine and their reported frequency of occurrence

| Adverse effect | Incidence rate among clozapine users |

|---|---|

| Agranulocytosis | 3/1000 person years* at 6 months |

| Hepatitis | Less than 1% |

| Hyperglycemia with ketoacidosis | Unknown, case reports |

| Myocarditis | 5.0-96.6 cases/100,000 patient years |

| Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | Unknown, several case reports |

| Orthostasis with cardiac collapse | 1/3,000 cases |

| Pulmonary embolism | 1/3,450 person years |

| Seizures | 5% after 1 year of therapy |

| * Person year = 1 person taking medication for 1 year | |

| Source: Clozaril prescribing information. In: Physicians’ Desk Reference (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003. | |

Other severe adverse effects of clozapine include myocarditis associated with cardiac failure, orthostatic hypotension with circulatory collapse, and rhabdomyolysis (Table).4,7 Leukocytosis and eosinophilia are generally transient and self-limited but may predict agranulocytosis.8,9 The risk of seizure occurs most commonly at dosages greater than 500 mg/d.4

Given these potentially fatal effects, the authors’ treatment guidelines call for potential suspension of clozapine therapy when the WBC is consistently <3,000 mm3 (Algorithm).

CONTINUED TREATMENT: A difficult decision

Ms. G was switched to quetiapine, 100 mg nightly, titrated to 800 mg/d in divided doses.

Approximately 3 weeks later, Ms. G was hospitalized for renewed severe paranoia and command-type auditory hallucinations accompanied by prominent mood lability, avolition, and thought disorganization. During her 7-week hospitalization, she underwent sequential and sometimes overlapping trials of:

- ziprasidone, 160 mg bid

- risperidone, 3 mg bid

- trifluoperazine, 3 mg bid

- haloperidol, 10 mg bid

- divalproex sodium, 500 mg bid

- and carbamazepine, 400 mg bid.

None of these trials significantly improved her psychosis or mood.

At this point, the treating psychiatrists faced a difficult but clear decision: Ms. G was rechallenged on clozapine, 25 mg nightly, titrated again to 300 mg nightly. After she provided informed consent, her WBC was monitored twice daily—morning and evening—for agranulocytosis and to examine WBC patterns. Her average daily WBC counts were 4,200/mm3 in the morning and 5,500/mm3 at night. No physical signs of agranulocytosis emerged.

One week after restarting clozapine, Ms. G became less paranoid and socially more appropriate. Her thought process became increasingly organized, and after 4 weeks she reached her baseline status based upon family reports and the clinician’s CGI Global Improvement rating of 2 (much improved). Her auditory hallucinations resolved, and she was discharged to her family’s care.

Twice-daily blood testing was stopped at discharge. Ms. G continues to take clozapine and receives blood tests every 2 weeks, with no apparent signs of agranulocytosis.

Algorithm Suggested guidelines for managing WBC counts during clozapine therapy

Two treatments for clozapine-dependent agranulocytosis have been described.

- Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) is a glycoprotein that has been shown to stimulate proliferation of precursor cells in bone marrow and their differentiation into granulocytes and macrophages. Researchers have reported that GM-CSF treatment allows patients to continue taking clozapine after an episode of severe neutropenia.10-12

- Lithium salts have been reported to exploit the natural leukocytosis observed with lithium to counter clozapine-related leukopenia.13 Use of lithium to displace white blood cells has been debated, and anecdotal evidence suggests that combining lithium with clozapine may increase the chance of seizure and neuroleptic malignant syndrome.4 Still, cases reported by Adityanjee and Blier suggest that lithium augmentation is cost-effective and efficacious.14,15

How could Ms. G’s doctors have avoided stopping her clozapine therapy and her subsequent decompensation?

The authors’ observations

Aggressive blood testing and cessation of clozapine therapy are indicated when onset of granulocytopenia and agranulocytosis are suspected. Even with early detection and discontinuation, the chance of infectious disease poses a danger for up to 4 weeks until WBC levels return to normal.4

Given Ms. G’s lack of response to other antipsychotics, however, we had to consider resuming clozapine therapy. Studies have described agranulocytosis management strategies that may allow patients to keep taking clozapine despite low WBC counts (Box).

We also considered the timing of Ms. G’s blood test that showed a WBC count <2,700/mm3. Ahokas16 suggests that evening WBC counts are significantly higher than those taken in the morning and that granulocytes fluctuate in a diurnal pattern. Ms. G’s evening WBC counts were on average 1,300/mm3 higher than morning levels. Allowing for this diurnal variation and comparing evening blood samples could have averted the interruption in Ms. G’s clozapine therapy and prevented relapse in a patient with highly treatment-refractory schizophrenia.

Related resources

- Chong SA, Remington G. Clozapine augmentation: safety and efficacy. Schizophr Bull 2000;26:421-40.

- Emsley R, Oosthuizen P. The new and evolving pharmacotherapy of schizophrenia. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2003;26:141-63.

- Barnas C, Zwierzina H, Hummer M, Sperner-Unterweger B, Stern A, Fleischhacker WW. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) treatment of clozapine-induced agranulocytosis: a case report. J Clin Psychiatry 1992;53:245-7.

Drug brand names

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Divalproex sodium • Depakote

- GM-CSF—Filgrastim • Neupogen

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid, others

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Trifluoperazine • Stelazine

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

Dr. Rao is a speaker for Pfizer Inc.

Drs. Goforth, Raval, and Sharma report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment resistant schizophrenic: a double blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:789-96.

2. Brenner HD, Dencker SJ, Goldstein MJ, et al. Defining treatment refractoriness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1990;16:551-61.

3. Meltzer HY. Clozapine: is another view valid? Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:821-5.

4. Clozaril prescribing information. In: Physicians’ Desk Reference. (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003.

5. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:162-7.

6. Honigfeld G. Effects of the clozapine national registry system on incidence of deaths related to agranulocytosis. Psychiatr Serv 1996;47:52-6.

7. Scelsa SN, Simpson DM, McQuistion HL, et al. Clozapineinduced myotoxicity in patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Neurology 1996;47:1518-23.

8. Ames D, Wirshing WC, Baker RW, et al. Predictive value of eosinophilia for neutropenia during clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:579-81.

9. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ. Do white-cell count spikes predict agranulocytosis in clozapine recipients? Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31:311-14.

10. Sperner-Unterweger B, Czeipek I, Gaggl S, et al. Treatment of severe clozapine-induced neutropenia with granulocyte colonystimulating factor (G-CSF). Remission despite continuous treatment with clozapine. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172:82-4.

11. Chengappa KN, Gopalani A, Haught MK, et al. The treatment of clozapine-associated agranulocytosis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:111-21.

12. Lamberti JS, Bellnier TJ, Schwarzkopf SB, Schneider E. Filgrastim treatment of three patients with clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56:256-9.

13. Boshes RA, Manschreck TC, Desrosiers J, et al. Initiation of clozapine therapy in a patient with preexisting leukopenia: a discussion of the rationale of current treatment options. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2001;13:233-7.

14. Adityanjee. Modification of clozapine-induced leukopenia and neutropenia with lithium carbonate. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:648-9.

15. Blier P, Slater S, Measham T, et al. Lithium and clozapine-induced neutropenia/agranulocytosis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;13:137-40.

16. Ahokas A, Elonen E. Circadian rhythm of white blood cells during clozapine treatment. Psychopharmacology 1999;144:301-2.

1. Kane J, Honigfeld G, Singer J, Meltzer H. Clozapine for the treatment resistant schizophrenic: a double blind comparison with chlorpromazine. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1988;45:789-96.

2. Brenner HD, Dencker SJ, Goldstein MJ, et al. Defining treatment refractoriness in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 1990;16:551-61.

3. Meltzer HY. Clozapine: is another view valid? Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:821-5.

4. Clozaril prescribing information. In: Physicians’ Desk Reference. (57th ed). Montvale, NJ: Thomson Healthcare, 2003.

5. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ, et al. Clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. Incidence and risk factors in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:162-7.

6. Honigfeld G. Effects of the clozapine national registry system on incidence of deaths related to agranulocytosis. Psychiatr Serv 1996;47:52-6.

7. Scelsa SN, Simpson DM, McQuistion HL, et al. Clozapineinduced myotoxicity in patients with chronic psychotic disorders. Neurology 1996;47:1518-23.

8. Ames D, Wirshing WC, Baker RW, et al. Predictive value of eosinophilia for neutropenia during clozapine treatment. J Clin Psychiatry 1996;57:579-81.

9. Alvir JM, Lieberman JA, Safferman AZ. Do white-cell count spikes predict agranulocytosis in clozapine recipients? Psychopharmacol Bull 1995;31:311-14.

10. Sperner-Unterweger B, Czeipek I, Gaggl S, et al. Treatment of severe clozapine-induced neutropenia with granulocyte colonystimulating factor (G-CSF). Remission despite continuous treatment with clozapine. Br J Psychiatry 1998;172:82-4.

11. Chengappa KN, Gopalani A, Haught MK, et al. The treatment of clozapine-associated agranulocytosis with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF). Psychopharmacol Bull 1996;32:111-21.

12. Lamberti JS, Bellnier TJ, Schwarzkopf SB, Schneider E. Filgrastim treatment of three patients with clozapine-induced agranulocytosis. J Clin Psychiatry 1995;56:256-9.

13. Boshes RA, Manschreck TC, Desrosiers J, et al. Initiation of clozapine therapy in a patient with preexisting leukopenia: a discussion of the rationale of current treatment options. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2001;13:233-7.

14. Adityanjee. Modification of clozapine-induced leukopenia and neutropenia with lithium carbonate. Am J Psychiatry 1995;152:648-9.

15. Blier P, Slater S, Measham T, et al. Lithium and clozapine-induced neutropenia/agranulocytosis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1998;13:137-40.

16. Ahokas A, Elonen E. Circadian rhythm of white blood cells during clozapine treatment. Psychopharmacology 1999;144:301-2.