User login

Asymptomatic Soft Tumor on the Forearm

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

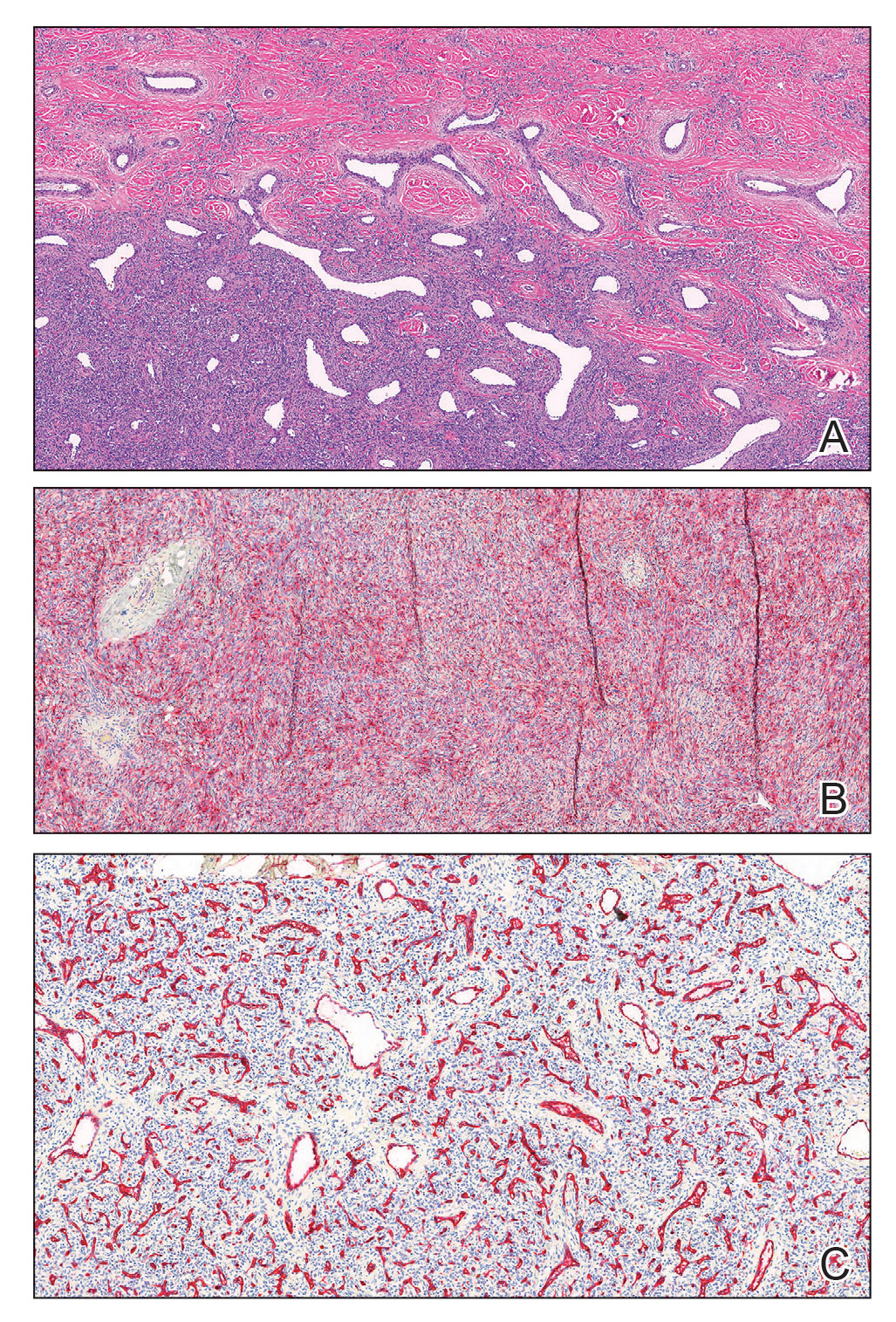

A shave biopsy of the entire tumor was performed at the initial visit. Histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a fibrohistiocytic infiltrate containing cleftlike cavernous spaces lined by epithelial cells (Figure, A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed factor XIIIa expression on fibrohistiocytic cells (Figure, B). CD34 was expressed on vascular endothelial cells, but it failed to highlight the fibrohistiocytic space (Figure, C). Overall, these findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma. The lesion healed without complications, and the patient was counseled on the risk for recurrence. He was offered localized excision but opted for conservative management without excision and close follow-up and monitoring.

Dermatofibromas are common benign cutaneous nodules that often are asymptomatic and occur on the extremities. Dermatofibromas also are known as cutaneous fibrous histiocytomas and have numerous histologic variants. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma (also called aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) is a rare histologic variant of dermatofibroma presenting as a slow-growing exophytic tumor that can be purple, red, brown, or blue. Although classic dermatofibromas typically constitute a straightforward diagnosis, aneurysmal dermatofibromas often are more challenging to clinically differentiate from other cutaneous neoplasms. Additionally, due to the exophytic nature and larger size (0.5–4.0 cm), aneurysmal dermatofibromas do not exhibit the characteristic dimple (Fitzpatrick) sign found in many dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are 10 times more likely to recur than classic dermatofibromas.1-4

Aneurysmal dermatofibromas can mimic other cutaneous neoplasms, some indolent and others more aggressive. Similar to aneurysmal dermatofibromas, solitary neurofibromas and nevi lipomatosus can appear as asymptomatic exophytic nodules with a similar spectrum of color and indolent clinical courses. In nevus lipomatosus, the dermis is almost entirely replaced by mature adipose tissue.5 Solitary neurofibromas represent a proliferation of neuromesenchymal cells with haphazardly arranged, wavy nuclei characteristic of nerve cells.6 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans can be distinguished from aneurysmal dermatofibroma by lack of factor XIIIa expression and diffuse positivity for CD34.7 Finally, aneurysmal dermatofibromas may resemble vascular tumors such as nodular Kaposi sarcoma. Kaposi sarcoma can be differentiated from an aneurysmal dermatofibroma by the presence of characteristic vascular wrapping, the absence of fibrohistiocytic cells, and expression of human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1.1,8 Although aneurysmal dermatofibromas are of low malignant potential, they are associated with a higher rate of recurrence compared to common dermatofibromas.9 Definitive treatment involves complete excision with follow-up to ensure no signs of recurrence.10 Incomplete excision can increase the likelihood of recurrence, especially for larger aneurysmal dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are one of the subtypes of dermatofibromas that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Han et al2 found that 77.8% of aneurysmal dermatofibromas extended into subcutaneous tissue. Recognizing the clinical and pathological features of this rare subtype of dermatofibroma can aid dermatologists in appropriate recognition and management.

- Burr DM, Peterson WA, Peterson MW. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath. June 2018;40. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/jaocd/contents/volume40/40-04.pdf

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JHK, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Morariu SH, Suciu M, Vartolomei MD, et al. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma mimicking both clinical and dermoscopic malignant melanoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1221-1224.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CDM. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Pujani M, Choudhury M, Garg T, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis: a rare cutaneous hamartoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:109-110.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Kandal S, Ozmen S, Demir HY, et al. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: a rare variant of dermatofibroma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2050-2051.

- Hornick JL. Cutaneous soft tissue tumors: how do we make sense of fibrous and “fibrohistiocytic” tumors with confusing names and similar appearances? Mod Pathol. 2020;33:56-65.

- Das A, Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, et al. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma presenting as a giant acrochordon on thigh. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:436.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

A shave biopsy of the entire tumor was performed at the initial visit. Histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a fibrohistiocytic infiltrate containing cleftlike cavernous spaces lined by epithelial cells (Figure, A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed factor XIIIa expression on fibrohistiocytic cells (Figure, B). CD34 was expressed on vascular endothelial cells, but it failed to highlight the fibrohistiocytic space (Figure, C). Overall, these findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma. The lesion healed without complications, and the patient was counseled on the risk for recurrence. He was offered localized excision but opted for conservative management without excision and close follow-up and monitoring.

Dermatofibromas are common benign cutaneous nodules that often are asymptomatic and occur on the extremities. Dermatofibromas also are known as cutaneous fibrous histiocytomas and have numerous histologic variants. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma (also called aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) is a rare histologic variant of dermatofibroma presenting as a slow-growing exophytic tumor that can be purple, red, brown, or blue. Although classic dermatofibromas typically constitute a straightforward diagnosis, aneurysmal dermatofibromas often are more challenging to clinically differentiate from other cutaneous neoplasms. Additionally, due to the exophytic nature and larger size (0.5–4.0 cm), aneurysmal dermatofibromas do not exhibit the characteristic dimple (Fitzpatrick) sign found in many dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are 10 times more likely to recur than classic dermatofibromas.1-4

Aneurysmal dermatofibromas can mimic other cutaneous neoplasms, some indolent and others more aggressive. Similar to aneurysmal dermatofibromas, solitary neurofibromas and nevi lipomatosus can appear as asymptomatic exophytic nodules with a similar spectrum of color and indolent clinical courses. In nevus lipomatosus, the dermis is almost entirely replaced by mature adipose tissue.5 Solitary neurofibromas represent a proliferation of neuromesenchymal cells with haphazardly arranged, wavy nuclei characteristic of nerve cells.6 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans can be distinguished from aneurysmal dermatofibroma by lack of factor XIIIa expression and diffuse positivity for CD34.7 Finally, aneurysmal dermatofibromas may resemble vascular tumors such as nodular Kaposi sarcoma. Kaposi sarcoma can be differentiated from an aneurysmal dermatofibroma by the presence of characteristic vascular wrapping, the absence of fibrohistiocytic cells, and expression of human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1.1,8 Although aneurysmal dermatofibromas are of low malignant potential, they are associated with a higher rate of recurrence compared to common dermatofibromas.9 Definitive treatment involves complete excision with follow-up to ensure no signs of recurrence.10 Incomplete excision can increase the likelihood of recurrence, especially for larger aneurysmal dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are one of the subtypes of dermatofibromas that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Han et al2 found that 77.8% of aneurysmal dermatofibromas extended into subcutaneous tissue. Recognizing the clinical and pathological features of this rare subtype of dermatofibroma can aid dermatologists in appropriate recognition and management.

The Diagnosis: Aneurysmal Dermatofibroma

A shave biopsy of the entire tumor was performed at the initial visit. Histologic examination with hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed a fibrohistiocytic infiltrate containing cleftlike cavernous spaces lined by epithelial cells (Figure, A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed factor XIIIa expression on fibrohistiocytic cells (Figure, B). CD34 was expressed on vascular endothelial cells, but it failed to highlight the fibrohistiocytic space (Figure, C). Overall, these findings supported the diagnosis of aneurysmal dermatofibroma. The lesion healed without complications, and the patient was counseled on the risk for recurrence. He was offered localized excision but opted for conservative management without excision and close follow-up and monitoring.

Dermatofibromas are common benign cutaneous nodules that often are asymptomatic and occur on the extremities. Dermatofibromas also are known as cutaneous fibrous histiocytomas and have numerous histologic variants. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma (also called aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma) is a rare histologic variant of dermatofibroma presenting as a slow-growing exophytic tumor that can be purple, red, brown, or blue. Although classic dermatofibromas typically constitute a straightforward diagnosis, aneurysmal dermatofibromas often are more challenging to clinically differentiate from other cutaneous neoplasms. Additionally, due to the exophytic nature and larger size (0.5–4.0 cm), aneurysmal dermatofibromas do not exhibit the characteristic dimple (Fitzpatrick) sign found in many dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are 10 times more likely to recur than classic dermatofibromas.1-4

Aneurysmal dermatofibromas can mimic other cutaneous neoplasms, some indolent and others more aggressive. Similar to aneurysmal dermatofibromas, solitary neurofibromas and nevi lipomatosus can appear as asymptomatic exophytic nodules with a similar spectrum of color and indolent clinical courses. In nevus lipomatosus, the dermis is almost entirely replaced by mature adipose tissue.5 Solitary neurofibromas represent a proliferation of neuromesenchymal cells with haphazardly arranged, wavy nuclei characteristic of nerve cells.6 Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans can be distinguished from aneurysmal dermatofibroma by lack of factor XIIIa expression and diffuse positivity for CD34.7 Finally, aneurysmal dermatofibromas may resemble vascular tumors such as nodular Kaposi sarcoma. Kaposi sarcoma can be differentiated from an aneurysmal dermatofibroma by the presence of characteristic vascular wrapping, the absence of fibrohistiocytic cells, and expression of human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1.1,8 Although aneurysmal dermatofibromas are of low malignant potential, they are associated with a higher rate of recurrence compared to common dermatofibromas.9 Definitive treatment involves complete excision with follow-up to ensure no signs of recurrence.10 Incomplete excision can increase the likelihood of recurrence, especially for larger aneurysmal dermatofibromas. Aneurysmal dermatofibromas are one of the subtypes of dermatofibromas that may extend into the subcutaneous tissue. Han et al2 found that 77.8% of aneurysmal dermatofibromas extended into subcutaneous tissue. Recognizing the clinical and pathological features of this rare subtype of dermatofibroma can aid dermatologists in appropriate recognition and management.

- Burr DM, Peterson WA, Peterson MW. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath. June 2018;40. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/jaocd/contents/volume40/40-04.pdf

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JHK, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Morariu SH, Suciu M, Vartolomei MD, et al. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma mimicking both clinical and dermoscopic malignant melanoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1221-1224.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CDM. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Pujani M, Choudhury M, Garg T, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis: a rare cutaneous hamartoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:109-110.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Kandal S, Ozmen S, Demir HY, et al. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: a rare variant of dermatofibroma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2050-2051.

- Hornick JL. Cutaneous soft tissue tumors: how do we make sense of fibrous and “fibrohistiocytic” tumors with confusing names and similar appearances? Mod Pathol. 2020;33:56-65.

- Das A, Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, et al. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma presenting as a giant acrochordon on thigh. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:436.

- Burr DM, Peterson WA, Peterson MW. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma: a case report and review of the literature. J Am Osteopath. June 2018;40. Accessed February 14, 2023. https://cdn.ymaws.com/www.aocd.org/resource/resmgr/jaocd/contents/volume40/40-04.pdf

- Han TY, Chang HS, Lee JHK, et al. A clinical and histopathological study of 122 cases of dermatofibroma (benign fibrous histiocytoma). Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:185-192.

- Morariu SH, Suciu M, Vartolomei MD, et al. Aneurysmal dermatofibroma mimicking both clinical and dermoscopic malignant melanoma and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2014;55:1221-1224.

- Calonje E, Fletcher CDM. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma: clinicopathological analysis of 40 cases of a tumour frequently misdiagnosed as a vascular neoplasm. Histopathology. 1995;26:323-331.

- Pujani M, Choudhury M, Garg T, et al. Nevus lipomatosus superficialis: a rare cutaneous hamartoma. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5:109-110.

- Strike SA, Puhaindran ME. Nerve tumors of the upper extremity. Clin Plast Surg. 2019;46:347-350.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Farhood AI. Dermatofibroma and dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans: differential expression of CD34 and factor XIIIa. Am J Dermatopathol. 1994;16:573-574.

- Kandal S, Ozmen S, Demir HY, et al. Aneurysmal fibrous histiocytoma of the skin: a rare variant of dermatofibroma. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:2050-2051.

- Hornick JL. Cutaneous soft tissue tumors: how do we make sense of fibrous and “fibrohistiocytic” tumors with confusing names and similar appearances? Mod Pathol. 2020;33:56-65.

- Das A, Das A, Bandyopadhyay D, et al. Aneurysmal benign fibrous histiocytoma presenting as a giant acrochordon on thigh. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:436.

A 43-year-old Black man with no notable medical history presented to our clinic with a progressively enlarging tumor on the right forearm of 12 months’ duration. Despite its progressive growth, the tumor was asymptomatic. Physical examination of the right forearm revealed a 3.7×3.0-cm, well-circumscribed, exophytic tumor with a mildly erythematous hue, scaly surface, and rubbery consistency. There was no surrounding erythema, edema, localized lymphadenopathy, or concurrent lymphedema.

Recurrent Pruritic Multifocal Erythematous Rash

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy demonstrated overlying acanthosis, focal spongiosis, and exocytosis. There also was proliferation and thickening of superficial capillaries and papillary fibrosis (Figure, A). There was a mixed interstitial and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils (Figure, A and B). Occasional flame figures were identified (Figure, C).

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, was first described in 1971 by Wells1 as a recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Rarely reported worldwide, this chronic relapsing condition is characterized by a pronounced eosinophilic infiltrate of the dermis resembling urticaria or cellulitis.2 The exact etiology has not been elucidated; however, links to certain medications, vaccines, exaggerated arthropod reactions, infections, and malignancies have been documented.3

Wells syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion and lacks a predictable dermatologic presentation, thereby mandating focused clinical follow-up as well as correlation with histopathology findings. Although the classic histologic hallmark of Wells syndrome is scattered flame figures, this finding is not specific and can be found in other hypereosinophilic conditions.2 Clinical manifestations most often consist of 2 distinct phases: an initial painful burning or pruritic sensation, followed by the development of erythematous and edematous dermal plaques that may heal with slight hyperpigmentation over 4 to 8 weeks. A case series of 19 patients demonstrated variants of Wells syndrome, with an annular granuloma-like appearance found primarily in adults and the signature plaque-type appearance predominating in children.4

Acute urticaria is characterized by pruritic erythematous wheals secondary to a histamine-mediated response brought on by a variety of triggers, typically allergic and self-resolving within 24 hours. When such lesions last longer than 24 hours, biopsy should be performed to exclude urticarial vasculitis, which is characterized by a burning or painful sensation rather than pruritis, in addition to dermal neutrophilia and perivascular infiltrate on histology. Erythema migrans of Lyme disease begins at the site of a tick bite, evolving from a red macule to an expanding targetoid lesion and typically is not pruritic. Infectious cellulitis presents with warm, tender, and poorly defined erythematous patches; can progress rapidly; and is accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fevers, malaise, and lymphadenopathy.

Best evidence favors the use of moderate- to high-dose corticosteroids as first-line treatment.5 The use of tumor necrosis factor blockers, various immunomodulating agents, and combination therapy with levocetirizine and hydroxyzine have demonstrated variable levels of efficacy, albeit often followed by high rates of relapse with drug discontinuation.6

- Wells GC. Recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:46-56.

- Aberer W, Konrad K, Wolff K. Wells' syndrome is a distinctive disease entity and not a histologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:105-114.

- Kaufmann D, Pichler W, Beer JH. Severe episode of high fever with rash, lymphadenopathy, neutropenia, and eosinophilia after minocycline therapy for acne. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1983-1984.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Ferreli C, Pinna AL, Atzori L, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Well's syndrome): a new case description. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:41-45.

- Cormerais M, Poizeau F, Darrieux L, et al. Wells' syndrome mimicking facial cellulitis: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:117-122.

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy demonstrated overlying acanthosis, focal spongiosis, and exocytosis. There also was proliferation and thickening of superficial capillaries and papillary fibrosis (Figure, A). There was a mixed interstitial and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils (Figure, A and B). Occasional flame figures were identified (Figure, C).

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, was first described in 1971 by Wells1 as a recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Rarely reported worldwide, this chronic relapsing condition is characterized by a pronounced eosinophilic infiltrate of the dermis resembling urticaria or cellulitis.2 The exact etiology has not been elucidated; however, links to certain medications, vaccines, exaggerated arthropod reactions, infections, and malignancies have been documented.3

Wells syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion and lacks a predictable dermatologic presentation, thereby mandating focused clinical follow-up as well as correlation with histopathology findings. Although the classic histologic hallmark of Wells syndrome is scattered flame figures, this finding is not specific and can be found in other hypereosinophilic conditions.2 Clinical manifestations most often consist of 2 distinct phases: an initial painful burning or pruritic sensation, followed by the development of erythematous and edematous dermal plaques that may heal with slight hyperpigmentation over 4 to 8 weeks. A case series of 19 patients demonstrated variants of Wells syndrome, with an annular granuloma-like appearance found primarily in adults and the signature plaque-type appearance predominating in children.4

Acute urticaria is characterized by pruritic erythematous wheals secondary to a histamine-mediated response brought on by a variety of triggers, typically allergic and self-resolving within 24 hours. When such lesions last longer than 24 hours, biopsy should be performed to exclude urticarial vasculitis, which is characterized by a burning or painful sensation rather than pruritis, in addition to dermal neutrophilia and perivascular infiltrate on histology. Erythema migrans of Lyme disease begins at the site of a tick bite, evolving from a red macule to an expanding targetoid lesion and typically is not pruritic. Infectious cellulitis presents with warm, tender, and poorly defined erythematous patches; can progress rapidly; and is accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fevers, malaise, and lymphadenopathy.

Best evidence favors the use of moderate- to high-dose corticosteroids as first-line treatment.5 The use of tumor necrosis factor blockers, various immunomodulating agents, and combination therapy with levocetirizine and hydroxyzine have demonstrated variable levels of efficacy, albeit often followed by high rates of relapse with drug discontinuation.6

The Diagnosis: Wells Syndrome

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy demonstrated overlying acanthosis, focal spongiosis, and exocytosis. There also was proliferation and thickening of superficial capillaries and papillary fibrosis (Figure, A). There was a mixed interstitial and perivascular inflammatory infiltrate consisting of lymphocytes, histiocytes, plasma cells, and eosinophils (Figure, A and B). Occasional flame figures were identified (Figure, C).

Wells syndrome, also known as eosinophilic cellulitis, was first described in 1971 by Wells1 as a recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Rarely reported worldwide, this chronic relapsing condition is characterized by a pronounced eosinophilic infiltrate of the dermis resembling urticaria or cellulitis.2 The exact etiology has not been elucidated; however, links to certain medications, vaccines, exaggerated arthropod reactions, infections, and malignancies have been documented.3

Wells syndrome is a diagnosis of exclusion and lacks a predictable dermatologic presentation, thereby mandating focused clinical follow-up as well as correlation with histopathology findings. Although the classic histologic hallmark of Wells syndrome is scattered flame figures, this finding is not specific and can be found in other hypereosinophilic conditions.2 Clinical manifestations most often consist of 2 distinct phases: an initial painful burning or pruritic sensation, followed by the development of erythematous and edematous dermal plaques that may heal with slight hyperpigmentation over 4 to 8 weeks. A case series of 19 patients demonstrated variants of Wells syndrome, with an annular granuloma-like appearance found primarily in adults and the signature plaque-type appearance predominating in children.4

Acute urticaria is characterized by pruritic erythematous wheals secondary to a histamine-mediated response brought on by a variety of triggers, typically allergic and self-resolving within 24 hours. When such lesions last longer than 24 hours, biopsy should be performed to exclude urticarial vasculitis, which is characterized by a burning or painful sensation rather than pruritis, in addition to dermal neutrophilia and perivascular infiltrate on histology. Erythema migrans of Lyme disease begins at the site of a tick bite, evolving from a red macule to an expanding targetoid lesion and typically is not pruritic. Infectious cellulitis presents with warm, tender, and poorly defined erythematous patches; can progress rapidly; and is accompanied by systemic symptoms such as fevers, malaise, and lymphadenopathy.

Best evidence favors the use of moderate- to high-dose corticosteroids as first-line treatment.5 The use of tumor necrosis factor blockers, various immunomodulating agents, and combination therapy with levocetirizine and hydroxyzine have demonstrated variable levels of efficacy, albeit often followed by high rates of relapse with drug discontinuation.6

- Wells GC. Recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:46-56.

- Aberer W, Konrad K, Wolff K. Wells' syndrome is a distinctive disease entity and not a histologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:105-114.

- Kaufmann D, Pichler W, Beer JH. Severe episode of high fever with rash, lymphadenopathy, neutropenia, and eosinophilia after minocycline therapy for acne. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1983-1984.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Ferreli C, Pinna AL, Atzori L, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Well's syndrome): a new case description. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:41-45.

- Cormerais M, Poizeau F, Darrieux L, et al. Wells' syndrome mimicking facial cellulitis: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:117-122.

- Wells GC. Recurrent granulomatous dermatitis with eosinophilia. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:46-56.

- Aberer W, Konrad K, Wolff K. Wells' syndrome is a distinctive disease entity and not a histologic diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18:105-114.

- Kaufmann D, Pichler W, Beer JH. Severe episode of high fever with rash, lymphadenopathy, neutropenia, and eosinophilia after minocycline therapy for acne. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1983-1984.

- Caputo R, Marzano AV, Vezzoli P, et al. Wells syndrome in adults and children: a report of 19 cases. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:1157-1161.

- Ferreli C, Pinna AL, Atzori L, et al. Eosinophilic cellulitis (Well's syndrome): a new case description. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 1999;13:41-45.

- Cormerais M, Poizeau F, Darrieux L, et al. Wells' syndrome mimicking facial cellulitis: a report of two cases. Case Rep Dermatol. 2015;7:117-122.

A 60-year-old man with a history of hyperlipidemia developed acute onset of an intensely pruritic and painful burning rash on the dorsal aspect of the left forearm of 8 days' duration. The patient described the rash as red and warm. It measured 2 cm at inception and peaked at 12 cm 6 months later when the patient presented. These symptoms resolved without therapeutic intervention.

Over the ensuing 6 months, he experienced 13 self-limited episodes of erythematous indurated cutaneous streaks, usually with proximal migration on the arms along with involvement of the posterior thorax and right leg. Five months prior to the onset of the initial rash, the patient had discontinued ezetimibe to treat hyperlipidemia due to swelling of the lips and tongue. He also reported that he regularly hunted in upstate Pennsylvania but reported no history of arthropod or animal bites. The patient did not take prescription or over-the-counter medications, and he denied the presence of fever, night sweats, fatigue, adenopathy, anorexia, weight loss, diarrhea, joint pain or swelling, or illicit drug use. Lyme titers, complete blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and comprehensive metabolic panel were within reference range. A punch biopsy was performed.