User login

Evaluation of an Enhanced Discharge Summary Template: Building a Better Handoff Document

From the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Abstract

- Objective: To design and implement an enhanced discharge summary for use by internal medicine providers and evaluate its impact.

- Methods. Pre/post-intervention study in which discharge summaries created in the 3 months before (n = 57) and 3 months after (n = 57) introduction of an enhanced discharge summary template were assessed using a 24-item scoring instrument. Measures evaluated included a composite discharge summary quality score, individual content item scores, global rating score, redundant documentation of consultants and procedures, documentation of non-active conditions, discharge summary word count, and time to completion. Physician satisfaction with the enhanced discharge summary was evaluated by survey.

- Results: The composite discharge summary quality score increased following the intervention (19.07 vs. 13.37, P < 0.001). Ten items showed improved documentation, including documented need for follow-up tests, cognitive status, code status, and communication with the next provider. The global rating score improved from 3.04 to 3.46 (P = 0.01). Discharge summary word count decreased from 717 to 701 (P = 0.002), with no change in the time to discharge summary completion. Surveyed physicians reported improved satisfaction with the enhanced discharge summary compared with the prior template.

- Conclusion: An enhanced discharge summary, designed to serve as a handoff between inpatient and outpatient providers, improved quality without negative effects on document length, time to completion, or physician satisfaction.

Patient safety is often compromised during the transition period following an acute hospitalization. Half of patients may experience an error related to discontinuity of care between inpatient and outpatient providers [1], frequently resulting in preventable adverse events [2,3]. The discharge summary document serves as the primary and often only method of communication between inpatient and outpatient providers [4,5]. Despite its intended purpose, the discharge summary is frequently unavailable at the time of post-discharge clinic visits [4,6,7]. Even when available, the traditional discharge summary may have limited effectiveness as a handoff document due to disorganization or excessive length [8–11].

The Joint Commission requires that a minimum set of elements are documented in every discharge summary, including reason for hospitalization, significant findings, procedures and treatment provided, discharge condition, patient and family instructions, and medication reconciliation [12]. Unfortunately, the required components fail to address many of the complexities encountered in the discharge process and have not adapted to changes in health care delivery. Discharge summary elements related to patients’ future care plans are often inaccurate or omitted [13], including pending diagnostic tests [14–17], recommended outpatient evaluations [18], pertinent discharge condition information [19], and medication changes [1,20,21].

In 2007, the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference made recommendations to address quality gaps in care transitions from inpatient to outpatient settings. This policy statement recommended the adoption of standard discharge summary templates and provided guidance on the addition of specific data elements, including patients’ preferences and goals and clear delineation of care responsibility during the transition period [22]. The use of note templates within the electronic health record (EHR) may help prevent omission of certain data elements [23,24], but inclusion of higher-level management information may require that health providers rethink the function and structure of the discharge summary. Rather than a “captain’s log” narrative of inpatient events, the discharge summary should be considered a handoff document, meant to communicate “a strategic plan for future care. . .lessons learned. . .unresolved issues, and include a projection of how the author believes patients’ clinical condition will evolve over time” [25].

We created and implemented an evidence-based, enhanced discharge summary template to serve as a practical handoff document between inpatient and outpatient providers. This article reports on the evaluation of the enhanced discharge summary in comparison to a traditional discharge summary template.

Methods

Setting

The intervention took place within the inpatient internal medicine service at a 621-bed academic medical center. The internal medicine service includes teaching and non-teaching teams that collectively discharge approximately 4700 patients per year. Approximately 40 staff physicians and 75 residents per year rotate on the inpatient service. The hospital system uses an EHR that supports all clinical activities, including documentation and physician order entry. The EHR also automatically faxes discharge summaries to the primary care physician (PCP) of record when finalized by the inpatient provider. Prior to the intervention, a default discharge summary template was used throughout the hospital system. No formal education on discharge summary composition was provided to inpatient providers or residents prior to this project. This research project was approved by the university institutional review board and was performed without external funding.

Template Redesign

The project was initiated by 2 hospital medicine physicians (CJS and MB) who recruited volunteer representatives from key stakeholder groups to participate in a quality improvement project. The final template redesign team was made up of 4 hospital medicine physicians, 2 ambulatory clinic physicians, 1 internal medicine chief resident, and 1 second-year internal medicine house officer. Two of the physicians (MB and AV) were the departmental EHR champions, serving as the liaisons between providers and EHR technology support/administration. Hospital administration provided analytics and EHR build-support. The team created an enhanced discharge summary template based on recommendations from professional societies [22,26] and published literature [25,27]. We made 4 key changes to the existing discharge summary template.

First, we added a section to the template that listed information crucial to follow-up care needs: tests needed after discharge and provider responsible for follow-up, pending labs at the time of discharge and provider responsible for follow-up, and follow-up appointment information. Provider feedback suggested these elements were frequently omitted or difficult to locate within the body of the discharge summary, so this section was prioritized at the top of the template. To stress the importance of direct communication, we added a heading asking for documentation of contact with the PCP.

Second, in recognition of the increasingly complicated condition of many of our discharging patients, we introduced subheadings and menus that addressed specific elements of patient condition, including cognitive status, indwelling lines and catheters, and activity level at discharge.

Third, a menu-supported section on advance care planning was added that included both code status and an outline of goals-of-care discussions that occurred during the hospitalization.

Finally, we made the template well-organized and succinct. The stand-alone diagnosis list from the pre-intervention template was eliminated and incorporated as part of the problem-based hospital course. In addition, EHR enhancements were introduced to minimize repetition in the lists of consultants, procedures, and chronic medical conditions. We added discrete, prioritized headings with drop down menus and minimized redundancies found in the prior generic template. For example, auto-populated information in the prior default discharge summary included redundant and clinically irrelevant consultants (eg, multiple listings for pharmacy consultation), procedures (eg, recurring hemodialysis encounters), and stable, chronic conditions (eg, hyperlipidemia) that lengthened the discharge summary without adding to its function as a handoff document.

The template was pilot-tested for 2 weeks with teaching and non-teaching teams. A focus group of 5 inpatient providers gave feedback via semi-structured interviews. The research team also solicited unstructured feedback from hospital medicine providers during a required standing administrative meeting. These suggestions informed revisions to the enhanced discharge summary, which was then made the default option for all internal medicine providers.

Education

A 30-minute educational session was developed and delivered by the authors. The objectives of the didactic portion were to describe how discharge summaries can impact patient care, understand how discharge summaries serve as a handoff document, list the components of an effective discharge summary, and describe strategies to avoid common errors in writing discharge summaries. The session included a review of pertinent literature [1,12,13,21], an outline of discharge summary best-practices [22,25], and an introduction to the new template. Trainers reviewed strategies for keeping the discharge summary concise, including using problem-based formatting, focusing on active hospital problems, and eliminating unnecessary or redundant information. Participants were encouraged to complete their discharge summaries and directly contact outpatient providers within 24 hours of discharge. Following the didactic session, participants critically reviewed an example discharge summary and discussed what was done well, what was done poorly, and what strategies they would have used to make it a more effective handoff document. Residents rotating on the inpatient internal medicine services received the education during their mandatory monthly orientation. Faculty physicians were provided the education at a required section meeting.

Quality Scoring of Discharge Summaries and Analysis

To evaluate the quality of discharge summaries, we developed a scoring instrument to measure inclusion of 24 key elements (Table 1). The scoring instrument (available from the authors) was pilot tested by 4 general internal medicine physicians on 5 sample discharge summaries. After independent scoring, this group met with members of the research team to provide feedback. Iterative revisions were made to the scoring instrument until scorers reached consensus in their understanding and application of the scoring instrument. Each discharge summary received a quality score from 0 to 24, based on the number of elements found to be present. Secondary quality metrics included a global quality rating using a 1 to 5 scale (described in Results); frequency of redundant documentation of consultants and procedures; frequency of documentation of non-active, chronic conditions; the length of the discharge summary (total word count); and time to completion.

We analyzed a sample of discharge summaries completed during the 3-month period prior to the intervention and the 3-month period following the intervention. A non-stratified random technique was employed by an independent party to generate discharge summary samples from the EHR. Living patients discharged from the internal medicine services after an inpatient admission of at least 48 hours were eligible for inclusion. Each discharge summary was scored by 2 general internal medicine physicians. Each scoring dyad comprised one of the authors paired with a volunteer non–research team member who scored discharge summaries independently. Discordant results were examined by the dyad and settled by consensus.

Physician Survey

We surveyed inpatient and outpatient physicians to determine their views about discharge summaries and their views about the template before and after the intervention. Respondents were asked to indicate to what degree they agreed with statements using a 5-point Likert scale. An email containing a consent cover letter and a link to an anonymous online survey was sent to residents rotating on internal medicine services during the study period and all hospital medicine faculty. Outpatient providers affiliated with the hospital system were sent the survey if they had received at least 5 discharge summaries from the internal medicine services over the preceding 6 months. Post-intervention surveys were timed to capture responses after an adequate exposure to the enhanced discharge summary template. Inpatient physicians were re-surveyed 3 months after introduction of the enhanced discharge summary and outpatient providers were re-surveyed after 1 year.

Statistical Analysis

We reviewed 10 pre-intervention discharge summaries to estimate baseline discharge summary quality scores. Anticipating a two-fold improvement following the intervention [24], we calculated a goal sample size of 108 discharge summaries (54 pre- and 54 post-intervention) assuming alpha of 0.05 and 80% power using a two-tailed chi-square test. Expecting that some discharge summaries may not meet our inclusion criteria, 114 summaries (57 pre- and 57 post-intervention) were included in the final sample. All analyses were performed on Stata v10.1 (StataCorp; College Station, TX).

For discharge summary quality scoring, inter-rater reliability was measured by calculating the kappa statistic and percent agreement for scoring elements. Chi-square analysis was used to compare individual scoring elements before and after the intervention when the sample size was 5 or greater. Fisher’s exact test was used when the sample size was less than 5. Counts, including number of inactive diagnoses, redundant consults, redundant procedures, and total words were compared using univariate Poisson regression. Wilcoxon rank sum analysis was utilized to compare pre-intervention to post-intervention composite scores and global scores. Patient and provider characteristics were compared using the t-test, chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or Wilcoxon rank sum, as appropriate.

For the surveys, pre-intervention and post-intervention matched pairs were compared. Likert score responses were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Results

Discharge Summary Quality Scores

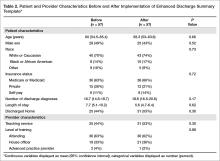

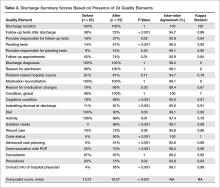

Characteristics of the pre- and post-intervention discharge summaries are displayed in Table 2. Both samples were similar with respect to patient demographics, length of stay, medical complexity, and provider characteristics. The mean composite discharge summary quality score improved from 13.4 at baseline to 19.1 in the post-intervention sample (P < 0.001) (Table 3). Ten of 24 quality elements exhibited significant improvement following the intervention, but 3 items were documented less often after the intervention (Table 3).

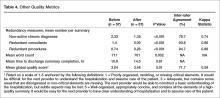

The global rating of discharge summary quality improved from 3.04 to 3.46 (P = 0.010) (Table 4). Documentation of superfluous and redundant information decreased in the 3 areas evaluated: number of non-active, chronic diagnoses (2.33 to 1.35, P < 0.001), redundant consults (1.4 to 0.09, P < 0.001), and redundant procedures (0.74 to 0.26, P < 0.001). Inter-rater reliability was generally high for individual items, although kappa score was not calculable in one case and scores of zero were obtained for 3 highly concordant items. Inter-rater reliability was moderate for global rating (kappa = 0.59). The overall length of discharge summaries decreased from 717 to 701 words (P = 0.002). There was no significant change in time to discharge summary completion following the intervention (10.9 hours pre-intervention vs. 14.5 post-intervention, P = 0.605) (Table 4).

Survey Results

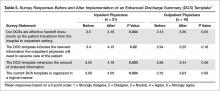

The inpatient provider response rate for the pre-intervention survey was 51/86 (59%) and 33/65 (51%) for the post-intervention survey, resulting in 21 paired responses. House officers represented the majority of paired respondents (14/21, 66%) with hospitalist faculty making up the remainder. Among outpatient physicians, the pre-intervention response rate was 19/25 (76%) and the post-intervention rate was 20/25 (80%), resulting in 16 paired responses. Half (8/16) of outpatient physicians provided only outpatient care, the other half practicing in a traditional model, providing both inpatient and outpatient care. Nearly half (7/16) had been in practice for over 15 years. Inpatient physicians’ agreement with all 4 statements related to discharge summary quality improved, including their perception of discharge summary effectiveness as a handoff document (P = 0.004). Inpatient providers estimated that the enhanced discharge summary took significantly less time to complete (19.3 vs. 24.6 minutes, P = 0.043). Outpatient providers’ perceptions of discharge summary quality trended toward improvement but did not reach statistical significance (Table 5).

Discussion

We found that a restructured note template in combination with physician education can improve discharge summary quality without sacrificing timeliness of note completion, document length, or physician satisfaction. The Joint Commission requires that discharge summaries include condition at discharge, but global assessments such as “good” or “stable” provide little clinically meaningful information to the next provider. Through our enhanced discharge summary we were able to significantly improve communication of several more specific elements relevant to discharge condition, including cognitive status. Similar to prior studies [7,13], cognitive condition was rarely documented prior to our intervention, but improved to 88% after introduction of the enhanced discharge summary. This is especially important, as we found that 25% of the post-intervention patients had a cognitive deficit at discharge. This information is critical for the next provider, who assumes responsibility for monitoring the patient’s trajectory.

Similarly, we improved the inclusion of patient preferences regarding advanced care planning. Whereas code status was rarely included the pre-intervention discharge summaries, we found that 1 in 5 patients in the post-intervention group did not want cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Beyond code status, we were also able to improve documentation of other advanced care conversations, such as end-of-life planning and power-of-attorney assignment. These conversations are increasingly common in the inpatient setting [28] but inconsistently documented [29,30].

To encourage inpatient-outpatient provider communication, the enhanced discharge summary template prompted documentation of communication with the PCP, with a resultant improvement from 25% to 72% (P < 0.001). The template also increased documentation of contact information for the hospital provider from 4% to 95% (P < 0.001). This improvement is notable, as hospital and outpatient physicians communicate infrequently [4,5], despite the fact that direct, “high-touch” communication is often preferred [10,11].

Our intervention builds upon prior research [23,24,31] through its deliberate focus on template formatting, evaluation of comprehensive clinical data elements using clearly defined scoring criteria, inclusion of teaching and non-teaching inpatient services, and assessment of inpatient and outpatient provider satisfaction. By restructuring the enhanced discharge summary template, we were able to improve documentation of clinical information, patient preferences, and physician communication, while keeping notes concise, prioritized, and timely. This restructuring included re-ordering information within the note, adding clear headings, devising intuitive drop-down menus, and removing unnecessary information. The amount of redundant information, document length, and perceived time required to write the discharge summary improved in the post-intervention period. Finally, our intervention was carried out with few resources and without financial incentives.

Although we found overall improvements following our intervention, there were several notable exceptions. Three content areas that were routinely documented in the pre-intervention period showed significant declines in the post-intervention phase: diet, activity, and procedures. Additionally, despite improvements in the post-intervention group, certain elements continued to be unreliably communicated in the discharge summary. Sporadic inclusion of pending tests (47%) was a particularly concerning finding. One possible explanation is that the addition of new elements and a focus on concise documentation encouraged physicians to skip or delete these areas of the enhanced discharge summary. It is also possible that reliance on drop-down menus and manual text entry, rather than auto-populated data, contributed to these deficits. As organizations re-design their electronic note templates, they should consider different content importing options [32] based on local institutional needs, culture, and EHR capabilities [33].

This study had several limitations. It was conducted at a single academic institution, so findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Although the magnitude and specificity of many of the measured outcomes suggests they were caused by the intervention, our pre/post study design cannot rule out the possibility that time-varying factors other than the intervention may have influenced our findings. We also used a novel scoring instrument, as a psychometrically tested discharge summary scoring instrument was not available at the time of the study [34]. Because it was based on similar concepts and evidence, the scoring instrument mirrored the data elements included in the intervention, which may have biased our results away from the null. However, the global rating score, which provided an overall appraisal of discharge summary quality unrelated to specific elements of the intervention, also showed significant improvement following the intervention. The distinct formatting of pre- and post-intervention templates meant that scorers were not blinded, thus making social desirability bias a possibility. We attempted to minimize the risk for bias by having all discharge summaries scored by 2 scorers, including one physician who was not a member of the research team. Small sample sizes, particularly with regard to the outpatient survey, may have contributed to type II errors. Additionally, although the discharge summary education was delivered during required meetings, we did not track attendance, so we were unable analyze for differences between providers who received the education and those that did not. Finally, while we evaluated discharge summaries for inclusion of key information, we did not perform chart reviews or contact PCPs to confirm the accuracy of documented information. Future study should evaluate the sustainability of our intervention and its impact on patient-level outcomes.

In conclusion, we found that revising our electronic template to better function as a handoff document could improve discharge summary quality. While most content areas evaluated showed improvement, there were several elements that were negatively impacted. Hospitals should be deliberate when reformatting their discharge summary templates so as to balance the need for efficient, manageable template navigation with accurate, complete, and necessary information.

Corresponding author: Christopher J. Smith, MD, 986430 Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE 68198-6430 Email: csmithj@unmc.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:646–51.

2. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:161–7.

3. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:317–23.

4. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007;297:831–41.

5. Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:381–6.

6. van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:186-92.

7. Horwitz LI, Jenq GY, Brewster UC, et al. Comprehensive quality of discharge summaries at an academic medical center. J Hosp Med 2013;8:436–43.

8. van Walraven C, Rokosh E. What is necessary for high-quality discharge summaries? Am J Med Qual 1999;14:160–9.

9. van Walraven C, Duke SM, Weinberg AL, Wells PS. Standardized or narrative discharge summaries. Which do family physicians prefer? Can Fam Physician 1998;44:62–9.

10. Sheu L, Fung K, Mourad M, et al. We need to talk: Primary care provider communication at discharge in the era of a shared electronic medical record. J Hosp Med 2015;10:307–10.

11. Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:417–24.

12. Kind AJH, Smith MA. Documentation of mandated discharge summary components in transitions from acute to subacute care. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Keyes MA, Grady ML, editors. Advances in patient safety: new directions and alternative approaches (Vol 2: Culture and Redesign). Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research; 2008.

13. Kind AJ, Thorpe CT, Sattin JA, et al. Provider characteristics, clinical-work processes and their relationship to discharge summary quality for sub-acute care patients. J Gen Intern Med 2012;27:78–84.

14. Roy CL, Poon EG, Karson AS, et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med 2005;143:121–8.

15. Were MC, Li X, Kesterson J, et al. Adequacy of hospital discharge summaries in documenting tests with pending results and outpatient follow-up providers. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:1002–6.

16. Walz SE, Smith M, Cox E, et al. Pending laboratory tests and the hospital discharge summary in patients discharged to sub-acute care. J Gen Intern Med 2011;26:393–8.

17. Kantor MA, Evans KH, Shieh L. Pending studies at hospital discharge: a pre-post analysis of an electronic medical record tool to improve communication at hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:312–8.

18. Moore C, McGinn T, Halm E. Tying up loose ends: discharging patients with unresolved medical issues. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:1305–11.

19. Al-Damluji MS, Dzara K, Hodshon B, et al. Hospital variation in quality of discharge summaries for patients hospitalized with heart failure exacerbation. Circulation Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2015;8:77–86.

20. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Raha D, Min SJ. Posthospital medication discrepancies: prevalence and contributing factors. Arch Intern Med 2005;165:1842–7.

21. Lindquist LA, Yamahiro A, Garrett A, et al. Primary care physician communication at hospital discharge reduces medication discrepancies. J Hosp Med 2013;8:672–7.

22. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of care consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. J Hosp Med 2009;4:364–70.

23. O’Leary KJ, Liebovitz DM, Feinglass J, et al. Creating a better discharge summary: improvement in quality and timeliness using an electronic discharge summary. J Hosp Med 2009;4:219–25.

24. Bischoff K, Goel A, Hollander H, et al. The Housestaff Incentive Program: improving the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries by engaging residents in quality improvement. BMJ Qual Safety 2013;22:768–74.

25. Lenert LA, Sakaguchi FH, Weir CR. Rethinking the discharge summary: a focus on handoff communication. Acad Med 2014;89:393–8.

26. Halasyamani L, Kripalani S, Coleman E, et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients--development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med 2006;1:354–60.

27. Kripalani S, Jackson AT, Schnipper JL, Coleman EA. Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med 2007;2:314–23.

28. Huijberts S, Buurman BM, de Rooij SE. End-of-life care during and after an acute hospitalization in older patients with cancer, end-stage organ failure, or frailty: A sub-analysis of a prospective cohort study. Palliat Med 2016;30:75–82.

29. Butler J, Binney Z, Kalogeropoulos A, et al. Advance directives among hospitalized patients with heart failure. JACC Heart Fail 2015;3:112–21.

30. Oulton J, Rhodes SM, Howe C, et al. Advance directives for older adults in the emergency department: a systematic review. J Palliat Med 2015;18:500–5.

31. Shaikh U, Slee C. Triple duty: integrating graduate medical education with maintenance of board certification to improve clinician communication at hospital discharge. J Grad Med Educ 2015;7:462–5.

32. Weis JM, Levy PC. Copy, paste, and cloned notes in electronic health records: prevalence, benefits, risks, and best practice recommendations. Chest 2014;145:632–8.

33. Dixon DR. The behavioral side of information technology. Int J Med Inform 1999;56:117–23.

34. Hommos MS, Kuperman EF, Kamath A, Kreiter CD. The development and evaluation of a novel instrument assessing residents’ discharge summaries. Acad Med 2017;92:550–5.

From the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Abstract

- Objective: To design and implement an enhanced discharge summary for use by internal medicine providers and evaluate its impact.

- Methods. Pre/post-intervention study in which discharge summaries created in the 3 months before (n = 57) and 3 months after (n = 57) introduction of an enhanced discharge summary template were assessed using a 24-item scoring instrument. Measures evaluated included a composite discharge summary quality score, individual content item scores, global rating score, redundant documentation of consultants and procedures, documentation of non-active conditions, discharge summary word count, and time to completion. Physician satisfaction with the enhanced discharge summary was evaluated by survey.

- Results: The composite discharge summary quality score increased following the intervention (19.07 vs. 13.37, P < 0.001). Ten items showed improved documentation, including documented need for follow-up tests, cognitive status, code status, and communication with the next provider. The global rating score improved from 3.04 to 3.46 (P = 0.01). Discharge summary word count decreased from 717 to 701 (P = 0.002), with no change in the time to discharge summary completion. Surveyed physicians reported improved satisfaction with the enhanced discharge summary compared with the prior template.

- Conclusion: An enhanced discharge summary, designed to serve as a handoff between inpatient and outpatient providers, improved quality without negative effects on document length, time to completion, or physician satisfaction.

Patient safety is often compromised during the transition period following an acute hospitalization. Half of patients may experience an error related to discontinuity of care between inpatient and outpatient providers [1], frequently resulting in preventable adverse events [2,3]. The discharge summary document serves as the primary and often only method of communication between inpatient and outpatient providers [4,5]. Despite its intended purpose, the discharge summary is frequently unavailable at the time of post-discharge clinic visits [4,6,7]. Even when available, the traditional discharge summary may have limited effectiveness as a handoff document due to disorganization or excessive length [8–11].

The Joint Commission requires that a minimum set of elements are documented in every discharge summary, including reason for hospitalization, significant findings, procedures and treatment provided, discharge condition, patient and family instructions, and medication reconciliation [12]. Unfortunately, the required components fail to address many of the complexities encountered in the discharge process and have not adapted to changes in health care delivery. Discharge summary elements related to patients’ future care plans are often inaccurate or omitted [13], including pending diagnostic tests [14–17], recommended outpatient evaluations [18], pertinent discharge condition information [19], and medication changes [1,20,21].

In 2007, the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference made recommendations to address quality gaps in care transitions from inpatient to outpatient settings. This policy statement recommended the adoption of standard discharge summary templates and provided guidance on the addition of specific data elements, including patients’ preferences and goals and clear delineation of care responsibility during the transition period [22]. The use of note templates within the electronic health record (EHR) may help prevent omission of certain data elements [23,24], but inclusion of higher-level management information may require that health providers rethink the function and structure of the discharge summary. Rather than a “captain’s log” narrative of inpatient events, the discharge summary should be considered a handoff document, meant to communicate “a strategic plan for future care. . .lessons learned. . .unresolved issues, and include a projection of how the author believes patients’ clinical condition will evolve over time” [25].

We created and implemented an evidence-based, enhanced discharge summary template to serve as a practical handoff document between inpatient and outpatient providers. This article reports on the evaluation of the enhanced discharge summary in comparison to a traditional discharge summary template.

Methods

Setting

The intervention took place within the inpatient internal medicine service at a 621-bed academic medical center. The internal medicine service includes teaching and non-teaching teams that collectively discharge approximately 4700 patients per year. Approximately 40 staff physicians and 75 residents per year rotate on the inpatient service. The hospital system uses an EHR that supports all clinical activities, including documentation and physician order entry. The EHR also automatically faxes discharge summaries to the primary care physician (PCP) of record when finalized by the inpatient provider. Prior to the intervention, a default discharge summary template was used throughout the hospital system. No formal education on discharge summary composition was provided to inpatient providers or residents prior to this project. This research project was approved by the university institutional review board and was performed without external funding.

Template Redesign

The project was initiated by 2 hospital medicine physicians (CJS and MB) who recruited volunteer representatives from key stakeholder groups to participate in a quality improvement project. The final template redesign team was made up of 4 hospital medicine physicians, 2 ambulatory clinic physicians, 1 internal medicine chief resident, and 1 second-year internal medicine house officer. Two of the physicians (MB and AV) were the departmental EHR champions, serving as the liaisons between providers and EHR technology support/administration. Hospital administration provided analytics and EHR build-support. The team created an enhanced discharge summary template based on recommendations from professional societies [22,26] and published literature [25,27]. We made 4 key changes to the existing discharge summary template.

First, we added a section to the template that listed information crucial to follow-up care needs: tests needed after discharge and provider responsible for follow-up, pending labs at the time of discharge and provider responsible for follow-up, and follow-up appointment information. Provider feedback suggested these elements were frequently omitted or difficult to locate within the body of the discharge summary, so this section was prioritized at the top of the template. To stress the importance of direct communication, we added a heading asking for documentation of contact with the PCP.

Second, in recognition of the increasingly complicated condition of many of our discharging patients, we introduced subheadings and menus that addressed specific elements of patient condition, including cognitive status, indwelling lines and catheters, and activity level at discharge.

Third, a menu-supported section on advance care planning was added that included both code status and an outline of goals-of-care discussions that occurred during the hospitalization.

Finally, we made the template well-organized and succinct. The stand-alone diagnosis list from the pre-intervention template was eliminated and incorporated as part of the problem-based hospital course. In addition, EHR enhancements were introduced to minimize repetition in the lists of consultants, procedures, and chronic medical conditions. We added discrete, prioritized headings with drop down menus and minimized redundancies found in the prior generic template. For example, auto-populated information in the prior default discharge summary included redundant and clinically irrelevant consultants (eg, multiple listings for pharmacy consultation), procedures (eg, recurring hemodialysis encounters), and stable, chronic conditions (eg, hyperlipidemia) that lengthened the discharge summary without adding to its function as a handoff document.

The template was pilot-tested for 2 weeks with teaching and non-teaching teams. A focus group of 5 inpatient providers gave feedback via semi-structured interviews. The research team also solicited unstructured feedback from hospital medicine providers during a required standing administrative meeting. These suggestions informed revisions to the enhanced discharge summary, which was then made the default option for all internal medicine providers.

Education

A 30-minute educational session was developed and delivered by the authors. The objectives of the didactic portion were to describe how discharge summaries can impact patient care, understand how discharge summaries serve as a handoff document, list the components of an effective discharge summary, and describe strategies to avoid common errors in writing discharge summaries. The session included a review of pertinent literature [1,12,13,21], an outline of discharge summary best-practices [22,25], and an introduction to the new template. Trainers reviewed strategies for keeping the discharge summary concise, including using problem-based formatting, focusing on active hospital problems, and eliminating unnecessary or redundant information. Participants were encouraged to complete their discharge summaries and directly contact outpatient providers within 24 hours of discharge. Following the didactic session, participants critically reviewed an example discharge summary and discussed what was done well, what was done poorly, and what strategies they would have used to make it a more effective handoff document. Residents rotating on the inpatient internal medicine services received the education during their mandatory monthly orientation. Faculty physicians were provided the education at a required section meeting.

Quality Scoring of Discharge Summaries and Analysis

To evaluate the quality of discharge summaries, we developed a scoring instrument to measure inclusion of 24 key elements (Table 1). The scoring instrument (available from the authors) was pilot tested by 4 general internal medicine physicians on 5 sample discharge summaries. After independent scoring, this group met with members of the research team to provide feedback. Iterative revisions were made to the scoring instrument until scorers reached consensus in their understanding and application of the scoring instrument. Each discharge summary received a quality score from 0 to 24, based on the number of elements found to be present. Secondary quality metrics included a global quality rating using a 1 to 5 scale (described in Results); frequency of redundant documentation of consultants and procedures; frequency of documentation of non-active, chronic conditions; the length of the discharge summary (total word count); and time to completion.

We analyzed a sample of discharge summaries completed during the 3-month period prior to the intervention and the 3-month period following the intervention. A non-stratified random technique was employed by an independent party to generate discharge summary samples from the EHR. Living patients discharged from the internal medicine services after an inpatient admission of at least 48 hours were eligible for inclusion. Each discharge summary was scored by 2 general internal medicine physicians. Each scoring dyad comprised one of the authors paired with a volunteer non–research team member who scored discharge summaries independently. Discordant results were examined by the dyad and settled by consensus.

Physician Survey

We surveyed inpatient and outpatient physicians to determine their views about discharge summaries and their views about the template before and after the intervention. Respondents were asked to indicate to what degree they agreed with statements using a 5-point Likert scale. An email containing a consent cover letter and a link to an anonymous online survey was sent to residents rotating on internal medicine services during the study period and all hospital medicine faculty. Outpatient providers affiliated with the hospital system were sent the survey if they had received at least 5 discharge summaries from the internal medicine services over the preceding 6 months. Post-intervention surveys were timed to capture responses after an adequate exposure to the enhanced discharge summary template. Inpatient physicians were re-surveyed 3 months after introduction of the enhanced discharge summary and outpatient providers were re-surveyed after 1 year.

Statistical Analysis

We reviewed 10 pre-intervention discharge summaries to estimate baseline discharge summary quality scores. Anticipating a two-fold improvement following the intervention [24], we calculated a goal sample size of 108 discharge summaries (54 pre- and 54 post-intervention) assuming alpha of 0.05 and 80% power using a two-tailed chi-square test. Expecting that some discharge summaries may not meet our inclusion criteria, 114 summaries (57 pre- and 57 post-intervention) were included in the final sample. All analyses were performed on Stata v10.1 (StataCorp; College Station, TX).

For discharge summary quality scoring, inter-rater reliability was measured by calculating the kappa statistic and percent agreement for scoring elements. Chi-square analysis was used to compare individual scoring elements before and after the intervention when the sample size was 5 or greater. Fisher’s exact test was used when the sample size was less than 5. Counts, including number of inactive diagnoses, redundant consults, redundant procedures, and total words were compared using univariate Poisson regression. Wilcoxon rank sum analysis was utilized to compare pre-intervention to post-intervention composite scores and global scores. Patient and provider characteristics were compared using the t-test, chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or Wilcoxon rank sum, as appropriate.

For the surveys, pre-intervention and post-intervention matched pairs were compared. Likert score responses were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Results

Discharge Summary Quality Scores

Characteristics of the pre- and post-intervention discharge summaries are displayed in Table 2. Both samples were similar with respect to patient demographics, length of stay, medical complexity, and provider characteristics. The mean composite discharge summary quality score improved from 13.4 at baseline to 19.1 in the post-intervention sample (P < 0.001) (Table 3). Ten of 24 quality elements exhibited significant improvement following the intervention, but 3 items were documented less often after the intervention (Table 3).

The global rating of discharge summary quality improved from 3.04 to 3.46 (P = 0.010) (Table 4). Documentation of superfluous and redundant information decreased in the 3 areas evaluated: number of non-active, chronic diagnoses (2.33 to 1.35, P < 0.001), redundant consults (1.4 to 0.09, P < 0.001), and redundant procedures (0.74 to 0.26, P < 0.001). Inter-rater reliability was generally high for individual items, although kappa score was not calculable in one case and scores of zero were obtained for 3 highly concordant items. Inter-rater reliability was moderate for global rating (kappa = 0.59). The overall length of discharge summaries decreased from 717 to 701 words (P = 0.002). There was no significant change in time to discharge summary completion following the intervention (10.9 hours pre-intervention vs. 14.5 post-intervention, P = 0.605) (Table 4).

Survey Results

The inpatient provider response rate for the pre-intervention survey was 51/86 (59%) and 33/65 (51%) for the post-intervention survey, resulting in 21 paired responses. House officers represented the majority of paired respondents (14/21, 66%) with hospitalist faculty making up the remainder. Among outpatient physicians, the pre-intervention response rate was 19/25 (76%) and the post-intervention rate was 20/25 (80%), resulting in 16 paired responses. Half (8/16) of outpatient physicians provided only outpatient care, the other half practicing in a traditional model, providing both inpatient and outpatient care. Nearly half (7/16) had been in practice for over 15 years. Inpatient physicians’ agreement with all 4 statements related to discharge summary quality improved, including their perception of discharge summary effectiveness as a handoff document (P = 0.004). Inpatient providers estimated that the enhanced discharge summary took significantly less time to complete (19.3 vs. 24.6 minutes, P = 0.043). Outpatient providers’ perceptions of discharge summary quality trended toward improvement but did not reach statistical significance (Table 5).

Discussion

We found that a restructured note template in combination with physician education can improve discharge summary quality without sacrificing timeliness of note completion, document length, or physician satisfaction. The Joint Commission requires that discharge summaries include condition at discharge, but global assessments such as “good” or “stable” provide little clinically meaningful information to the next provider. Through our enhanced discharge summary we were able to significantly improve communication of several more specific elements relevant to discharge condition, including cognitive status. Similar to prior studies [7,13], cognitive condition was rarely documented prior to our intervention, but improved to 88% after introduction of the enhanced discharge summary. This is especially important, as we found that 25% of the post-intervention patients had a cognitive deficit at discharge. This information is critical for the next provider, who assumes responsibility for monitoring the patient’s trajectory.

Similarly, we improved the inclusion of patient preferences regarding advanced care planning. Whereas code status was rarely included the pre-intervention discharge summaries, we found that 1 in 5 patients in the post-intervention group did not want cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Beyond code status, we were also able to improve documentation of other advanced care conversations, such as end-of-life planning and power-of-attorney assignment. These conversations are increasingly common in the inpatient setting [28] but inconsistently documented [29,30].

To encourage inpatient-outpatient provider communication, the enhanced discharge summary template prompted documentation of communication with the PCP, with a resultant improvement from 25% to 72% (P < 0.001). The template also increased documentation of contact information for the hospital provider from 4% to 95% (P < 0.001). This improvement is notable, as hospital and outpatient physicians communicate infrequently [4,5], despite the fact that direct, “high-touch” communication is often preferred [10,11].

Our intervention builds upon prior research [23,24,31] through its deliberate focus on template formatting, evaluation of comprehensive clinical data elements using clearly defined scoring criteria, inclusion of teaching and non-teaching inpatient services, and assessment of inpatient and outpatient provider satisfaction. By restructuring the enhanced discharge summary template, we were able to improve documentation of clinical information, patient preferences, and physician communication, while keeping notes concise, prioritized, and timely. This restructuring included re-ordering information within the note, adding clear headings, devising intuitive drop-down menus, and removing unnecessary information. The amount of redundant information, document length, and perceived time required to write the discharge summary improved in the post-intervention period. Finally, our intervention was carried out with few resources and without financial incentives.

Although we found overall improvements following our intervention, there were several notable exceptions. Three content areas that were routinely documented in the pre-intervention period showed significant declines in the post-intervention phase: diet, activity, and procedures. Additionally, despite improvements in the post-intervention group, certain elements continued to be unreliably communicated in the discharge summary. Sporadic inclusion of pending tests (47%) was a particularly concerning finding. One possible explanation is that the addition of new elements and a focus on concise documentation encouraged physicians to skip or delete these areas of the enhanced discharge summary. It is also possible that reliance on drop-down menus and manual text entry, rather than auto-populated data, contributed to these deficits. As organizations re-design their electronic note templates, they should consider different content importing options [32] based on local institutional needs, culture, and EHR capabilities [33].

This study had several limitations. It was conducted at a single academic institution, so findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Although the magnitude and specificity of many of the measured outcomes suggests they were caused by the intervention, our pre/post study design cannot rule out the possibility that time-varying factors other than the intervention may have influenced our findings. We also used a novel scoring instrument, as a psychometrically tested discharge summary scoring instrument was not available at the time of the study [34]. Because it was based on similar concepts and evidence, the scoring instrument mirrored the data elements included in the intervention, which may have biased our results away from the null. However, the global rating score, which provided an overall appraisal of discharge summary quality unrelated to specific elements of the intervention, also showed significant improvement following the intervention. The distinct formatting of pre- and post-intervention templates meant that scorers were not blinded, thus making social desirability bias a possibility. We attempted to minimize the risk for bias by having all discharge summaries scored by 2 scorers, including one physician who was not a member of the research team. Small sample sizes, particularly with regard to the outpatient survey, may have contributed to type II errors. Additionally, although the discharge summary education was delivered during required meetings, we did not track attendance, so we were unable analyze for differences between providers who received the education and those that did not. Finally, while we evaluated discharge summaries for inclusion of key information, we did not perform chart reviews or contact PCPs to confirm the accuracy of documented information. Future study should evaluate the sustainability of our intervention and its impact on patient-level outcomes.

In conclusion, we found that revising our electronic template to better function as a handoff document could improve discharge summary quality. While most content areas evaluated showed improvement, there were several elements that were negatively impacted. Hospitals should be deliberate when reformatting their discharge summary templates so as to balance the need for efficient, manageable template navigation with accurate, complete, and necessary information.

Corresponding author: Christopher J. Smith, MD, 986430 Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE 68198-6430 Email: csmithj@unmc.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Internal Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE.

Abstract

- Objective: To design and implement an enhanced discharge summary for use by internal medicine providers and evaluate its impact.

- Methods. Pre/post-intervention study in which discharge summaries created in the 3 months before (n = 57) and 3 months after (n = 57) introduction of an enhanced discharge summary template were assessed using a 24-item scoring instrument. Measures evaluated included a composite discharge summary quality score, individual content item scores, global rating score, redundant documentation of consultants and procedures, documentation of non-active conditions, discharge summary word count, and time to completion. Physician satisfaction with the enhanced discharge summary was evaluated by survey.

- Results: The composite discharge summary quality score increased following the intervention (19.07 vs. 13.37, P < 0.001). Ten items showed improved documentation, including documented need for follow-up tests, cognitive status, code status, and communication with the next provider. The global rating score improved from 3.04 to 3.46 (P = 0.01). Discharge summary word count decreased from 717 to 701 (P = 0.002), with no change in the time to discharge summary completion. Surveyed physicians reported improved satisfaction with the enhanced discharge summary compared with the prior template.

- Conclusion: An enhanced discharge summary, designed to serve as a handoff between inpatient and outpatient providers, improved quality without negative effects on document length, time to completion, or physician satisfaction.

Patient safety is often compromised during the transition period following an acute hospitalization. Half of patients may experience an error related to discontinuity of care between inpatient and outpatient providers [1], frequently resulting in preventable adverse events [2,3]. The discharge summary document serves as the primary and often only method of communication between inpatient and outpatient providers [4,5]. Despite its intended purpose, the discharge summary is frequently unavailable at the time of post-discharge clinic visits [4,6,7]. Even when available, the traditional discharge summary may have limited effectiveness as a handoff document due to disorganization or excessive length [8–11].

The Joint Commission requires that a minimum set of elements are documented in every discharge summary, including reason for hospitalization, significant findings, procedures and treatment provided, discharge condition, patient and family instructions, and medication reconciliation [12]. Unfortunately, the required components fail to address many of the complexities encountered in the discharge process and have not adapted to changes in health care delivery. Discharge summary elements related to patients’ future care plans are often inaccurate or omitted [13], including pending diagnostic tests [14–17], recommended outpatient evaluations [18], pertinent discharge condition information [19], and medication changes [1,20,21].

In 2007, the Transitions of Care Consensus Conference made recommendations to address quality gaps in care transitions from inpatient to outpatient settings. This policy statement recommended the adoption of standard discharge summary templates and provided guidance on the addition of specific data elements, including patients’ preferences and goals and clear delineation of care responsibility during the transition period [22]. The use of note templates within the electronic health record (EHR) may help prevent omission of certain data elements [23,24], but inclusion of higher-level management information may require that health providers rethink the function and structure of the discharge summary. Rather than a “captain’s log” narrative of inpatient events, the discharge summary should be considered a handoff document, meant to communicate “a strategic plan for future care. . .lessons learned. . .unresolved issues, and include a projection of how the author believes patients’ clinical condition will evolve over time” [25].

We created and implemented an evidence-based, enhanced discharge summary template to serve as a practical handoff document between inpatient and outpatient providers. This article reports on the evaluation of the enhanced discharge summary in comparison to a traditional discharge summary template.

Methods

Setting

The intervention took place within the inpatient internal medicine service at a 621-bed academic medical center. The internal medicine service includes teaching and non-teaching teams that collectively discharge approximately 4700 patients per year. Approximately 40 staff physicians and 75 residents per year rotate on the inpatient service. The hospital system uses an EHR that supports all clinical activities, including documentation and physician order entry. The EHR also automatically faxes discharge summaries to the primary care physician (PCP) of record when finalized by the inpatient provider. Prior to the intervention, a default discharge summary template was used throughout the hospital system. No formal education on discharge summary composition was provided to inpatient providers or residents prior to this project. This research project was approved by the university institutional review board and was performed without external funding.

Template Redesign

The project was initiated by 2 hospital medicine physicians (CJS and MB) who recruited volunteer representatives from key stakeholder groups to participate in a quality improvement project. The final template redesign team was made up of 4 hospital medicine physicians, 2 ambulatory clinic physicians, 1 internal medicine chief resident, and 1 second-year internal medicine house officer. Two of the physicians (MB and AV) were the departmental EHR champions, serving as the liaisons between providers and EHR technology support/administration. Hospital administration provided analytics and EHR build-support. The team created an enhanced discharge summary template based on recommendations from professional societies [22,26] and published literature [25,27]. We made 4 key changes to the existing discharge summary template.

First, we added a section to the template that listed information crucial to follow-up care needs: tests needed after discharge and provider responsible for follow-up, pending labs at the time of discharge and provider responsible for follow-up, and follow-up appointment information. Provider feedback suggested these elements were frequently omitted or difficult to locate within the body of the discharge summary, so this section was prioritized at the top of the template. To stress the importance of direct communication, we added a heading asking for documentation of contact with the PCP.

Second, in recognition of the increasingly complicated condition of many of our discharging patients, we introduced subheadings and menus that addressed specific elements of patient condition, including cognitive status, indwelling lines and catheters, and activity level at discharge.

Third, a menu-supported section on advance care planning was added that included both code status and an outline of goals-of-care discussions that occurred during the hospitalization.

Finally, we made the template well-organized and succinct. The stand-alone diagnosis list from the pre-intervention template was eliminated and incorporated as part of the problem-based hospital course. In addition, EHR enhancements were introduced to minimize repetition in the lists of consultants, procedures, and chronic medical conditions. We added discrete, prioritized headings with drop down menus and minimized redundancies found in the prior generic template. For example, auto-populated information in the prior default discharge summary included redundant and clinically irrelevant consultants (eg, multiple listings for pharmacy consultation), procedures (eg, recurring hemodialysis encounters), and stable, chronic conditions (eg, hyperlipidemia) that lengthened the discharge summary without adding to its function as a handoff document.

The template was pilot-tested for 2 weeks with teaching and non-teaching teams. A focus group of 5 inpatient providers gave feedback via semi-structured interviews. The research team also solicited unstructured feedback from hospital medicine providers during a required standing administrative meeting. These suggestions informed revisions to the enhanced discharge summary, which was then made the default option for all internal medicine providers.

Education

A 30-minute educational session was developed and delivered by the authors. The objectives of the didactic portion were to describe how discharge summaries can impact patient care, understand how discharge summaries serve as a handoff document, list the components of an effective discharge summary, and describe strategies to avoid common errors in writing discharge summaries. The session included a review of pertinent literature [1,12,13,21], an outline of discharge summary best-practices [22,25], and an introduction to the new template. Trainers reviewed strategies for keeping the discharge summary concise, including using problem-based formatting, focusing on active hospital problems, and eliminating unnecessary or redundant information. Participants were encouraged to complete their discharge summaries and directly contact outpatient providers within 24 hours of discharge. Following the didactic session, participants critically reviewed an example discharge summary and discussed what was done well, what was done poorly, and what strategies they would have used to make it a more effective handoff document. Residents rotating on the inpatient internal medicine services received the education during their mandatory monthly orientation. Faculty physicians were provided the education at a required section meeting.

Quality Scoring of Discharge Summaries and Analysis

To evaluate the quality of discharge summaries, we developed a scoring instrument to measure inclusion of 24 key elements (Table 1). The scoring instrument (available from the authors) was pilot tested by 4 general internal medicine physicians on 5 sample discharge summaries. After independent scoring, this group met with members of the research team to provide feedback. Iterative revisions were made to the scoring instrument until scorers reached consensus in their understanding and application of the scoring instrument. Each discharge summary received a quality score from 0 to 24, based on the number of elements found to be present. Secondary quality metrics included a global quality rating using a 1 to 5 scale (described in Results); frequency of redundant documentation of consultants and procedures; frequency of documentation of non-active, chronic conditions; the length of the discharge summary (total word count); and time to completion.

We analyzed a sample of discharge summaries completed during the 3-month period prior to the intervention and the 3-month period following the intervention. A non-stratified random technique was employed by an independent party to generate discharge summary samples from the EHR. Living patients discharged from the internal medicine services after an inpatient admission of at least 48 hours were eligible for inclusion. Each discharge summary was scored by 2 general internal medicine physicians. Each scoring dyad comprised one of the authors paired with a volunteer non–research team member who scored discharge summaries independently. Discordant results were examined by the dyad and settled by consensus.

Physician Survey

We surveyed inpatient and outpatient physicians to determine their views about discharge summaries and their views about the template before and after the intervention. Respondents were asked to indicate to what degree they agreed with statements using a 5-point Likert scale. An email containing a consent cover letter and a link to an anonymous online survey was sent to residents rotating on internal medicine services during the study period and all hospital medicine faculty. Outpatient providers affiliated with the hospital system were sent the survey if they had received at least 5 discharge summaries from the internal medicine services over the preceding 6 months. Post-intervention surveys were timed to capture responses after an adequate exposure to the enhanced discharge summary template. Inpatient physicians were re-surveyed 3 months after introduction of the enhanced discharge summary and outpatient providers were re-surveyed after 1 year.

Statistical Analysis

We reviewed 10 pre-intervention discharge summaries to estimate baseline discharge summary quality scores. Anticipating a two-fold improvement following the intervention [24], we calculated a goal sample size of 108 discharge summaries (54 pre- and 54 post-intervention) assuming alpha of 0.05 and 80% power using a two-tailed chi-square test. Expecting that some discharge summaries may not meet our inclusion criteria, 114 summaries (57 pre- and 57 post-intervention) were included in the final sample. All analyses were performed on Stata v10.1 (StataCorp; College Station, TX).

For discharge summary quality scoring, inter-rater reliability was measured by calculating the kappa statistic and percent agreement for scoring elements. Chi-square analysis was used to compare individual scoring elements before and after the intervention when the sample size was 5 or greater. Fisher’s exact test was used when the sample size was less than 5. Counts, including number of inactive diagnoses, redundant consults, redundant procedures, and total words were compared using univariate Poisson regression. Wilcoxon rank sum analysis was utilized to compare pre-intervention to post-intervention composite scores and global scores. Patient and provider characteristics were compared using the t-test, chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, or Wilcoxon rank sum, as appropriate.

For the surveys, pre-intervention and post-intervention matched pairs were compared. Likert score responses were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

Results

Discharge Summary Quality Scores

Characteristics of the pre- and post-intervention discharge summaries are displayed in Table 2. Both samples were similar with respect to patient demographics, length of stay, medical complexity, and provider characteristics. The mean composite discharge summary quality score improved from 13.4 at baseline to 19.1 in the post-intervention sample (P < 0.001) (Table 3). Ten of 24 quality elements exhibited significant improvement following the intervention, but 3 items were documented less often after the intervention (Table 3).

The global rating of discharge summary quality improved from 3.04 to 3.46 (P = 0.010) (Table 4). Documentation of superfluous and redundant information decreased in the 3 areas evaluated: number of non-active, chronic diagnoses (2.33 to 1.35, P < 0.001), redundant consults (1.4 to 0.09, P < 0.001), and redundant procedures (0.74 to 0.26, P < 0.001). Inter-rater reliability was generally high for individual items, although kappa score was not calculable in one case and scores of zero were obtained for 3 highly concordant items. Inter-rater reliability was moderate for global rating (kappa = 0.59). The overall length of discharge summaries decreased from 717 to 701 words (P = 0.002). There was no significant change in time to discharge summary completion following the intervention (10.9 hours pre-intervention vs. 14.5 post-intervention, P = 0.605) (Table 4).

Survey Results

The inpatient provider response rate for the pre-intervention survey was 51/86 (59%) and 33/65 (51%) for the post-intervention survey, resulting in 21 paired responses. House officers represented the majority of paired respondents (14/21, 66%) with hospitalist faculty making up the remainder. Among outpatient physicians, the pre-intervention response rate was 19/25 (76%) and the post-intervention rate was 20/25 (80%), resulting in 16 paired responses. Half (8/16) of outpatient physicians provided only outpatient care, the other half practicing in a traditional model, providing both inpatient and outpatient care. Nearly half (7/16) had been in practice for over 15 years. Inpatient physicians’ agreement with all 4 statements related to discharge summary quality improved, including their perception of discharge summary effectiveness as a handoff document (P = 0.004). Inpatient providers estimated that the enhanced discharge summary took significantly less time to complete (19.3 vs. 24.6 minutes, P = 0.043). Outpatient providers’ perceptions of discharge summary quality trended toward improvement but did not reach statistical significance (Table 5).

Discussion

We found that a restructured note template in combination with physician education can improve discharge summary quality without sacrificing timeliness of note completion, document length, or physician satisfaction. The Joint Commission requires that discharge summaries include condition at discharge, but global assessments such as “good” or “stable” provide little clinically meaningful information to the next provider. Through our enhanced discharge summary we were able to significantly improve communication of several more specific elements relevant to discharge condition, including cognitive status. Similar to prior studies [7,13], cognitive condition was rarely documented prior to our intervention, but improved to 88% after introduction of the enhanced discharge summary. This is especially important, as we found that 25% of the post-intervention patients had a cognitive deficit at discharge. This information is critical for the next provider, who assumes responsibility for monitoring the patient’s trajectory.

Similarly, we improved the inclusion of patient preferences regarding advanced care planning. Whereas code status was rarely included the pre-intervention discharge summaries, we found that 1 in 5 patients in the post-intervention group did not want cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Beyond code status, we were also able to improve documentation of other advanced care conversations, such as end-of-life planning and power-of-attorney assignment. These conversations are increasingly common in the inpatient setting [28] but inconsistently documented [29,30].

To encourage inpatient-outpatient provider communication, the enhanced discharge summary template prompted documentation of communication with the PCP, with a resultant improvement from 25% to 72% (P < 0.001). The template also increased documentation of contact information for the hospital provider from 4% to 95% (P < 0.001). This improvement is notable, as hospital and outpatient physicians communicate infrequently [4,5], despite the fact that direct, “high-touch” communication is often preferred [10,11].

Our intervention builds upon prior research [23,24,31] through its deliberate focus on template formatting, evaluation of comprehensive clinical data elements using clearly defined scoring criteria, inclusion of teaching and non-teaching inpatient services, and assessment of inpatient and outpatient provider satisfaction. By restructuring the enhanced discharge summary template, we were able to improve documentation of clinical information, patient preferences, and physician communication, while keeping notes concise, prioritized, and timely. This restructuring included re-ordering information within the note, adding clear headings, devising intuitive drop-down menus, and removing unnecessary information. The amount of redundant information, document length, and perceived time required to write the discharge summary improved in the post-intervention period. Finally, our intervention was carried out with few resources and without financial incentives.

Although we found overall improvements following our intervention, there were several notable exceptions. Three content areas that were routinely documented in the pre-intervention period showed significant declines in the post-intervention phase: diet, activity, and procedures. Additionally, despite improvements in the post-intervention group, certain elements continued to be unreliably communicated in the discharge summary. Sporadic inclusion of pending tests (47%) was a particularly concerning finding. One possible explanation is that the addition of new elements and a focus on concise documentation encouraged physicians to skip or delete these areas of the enhanced discharge summary. It is also possible that reliance on drop-down menus and manual text entry, rather than auto-populated data, contributed to these deficits. As organizations re-design their electronic note templates, they should consider different content importing options [32] based on local institutional needs, culture, and EHR capabilities [33].

This study had several limitations. It was conducted at a single academic institution, so findings may not be generalizable to other settings. Although the magnitude and specificity of many of the measured outcomes suggests they were caused by the intervention, our pre/post study design cannot rule out the possibility that time-varying factors other than the intervention may have influenced our findings. We also used a novel scoring instrument, as a psychometrically tested discharge summary scoring instrument was not available at the time of the study [34]. Because it was based on similar concepts and evidence, the scoring instrument mirrored the data elements included in the intervention, which may have biased our results away from the null. However, the global rating score, which provided an overall appraisal of discharge summary quality unrelated to specific elements of the intervention, also showed significant improvement following the intervention. The distinct formatting of pre- and post-intervention templates meant that scorers were not blinded, thus making social desirability bias a possibility. We attempted to minimize the risk for bias by having all discharge summaries scored by 2 scorers, including one physician who was not a member of the research team. Small sample sizes, particularly with regard to the outpatient survey, may have contributed to type II errors. Additionally, although the discharge summary education was delivered during required meetings, we did not track attendance, so we were unable analyze for differences between providers who received the education and those that did not. Finally, while we evaluated discharge summaries for inclusion of key information, we did not perform chart reviews or contact PCPs to confirm the accuracy of documented information. Future study should evaluate the sustainability of our intervention and its impact on patient-level outcomes.

In conclusion, we found that revising our electronic template to better function as a handoff document could improve discharge summary quality. While most content areas evaluated showed improvement, there were several elements that were negatively impacted. Hospitals should be deliberate when reformatting their discharge summary templates so as to balance the need for efficient, manageable template navigation with accurate, complete, and necessary information.

Corresponding author: Christopher J. Smith, MD, 986430 Nebraska Medical Center Omaha, NE 68198-6430 Email: csmithj@unmc.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med 2003;18:646–51.

2. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med 2003;138:161–7.

3. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, et al. Adverse drug events occurring following hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med 2005;20:317–23.

4. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, et al. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA 2007;297:831–41.

5. Bell CM, Schnipper JL, Auerbach AD, et al. Association of communication between hospital-based physicians and primary care providers with patient outcomes. J Gen Intern Med 2009;24:381–6.

6. van Walraven C, Seth R, Austin PC, Laupacis A. Effect of discharge summary availability during post-discharge visits on hospital readmission. J Gen Intern Med 2002;17:186-92.

7. Horwitz LI, Jenq GY, Brewster UC, et al. Comprehensive quality of discharge summaries at an academic medical center. J Hosp Med 2013;8:436–43.

8. van Walraven C, Rokosh E. What is necessary for high-quality discharge summaries? Am J Med Qual 1999;14:160–9.

9. van Walraven C, Duke SM, Weinberg AL, Wells PS. Standardized or narrative discharge summaries. Which do family physicians prefer? Can Fam Physician 1998;44:62–9.

10. Sheu L, Fung K, Mourad M, et al. We need to talk: Primary care provider communication at discharge in the era of a shared electronic medical record. J Hosp Med 2015;10:307–10.

11. Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med 2015;30:417–24.