User login

Epidemiology and Impact of Knee Injuries in Major and Minor League Baseball Players

Injuries among professional baseball players have been on the rise for several years.1,2 From 1989 to 1999, the number of disabled list (DL) reports increased 38% (266 to 367 annual reports),1 and a similar increase in injury rates was noted from the 2002 to the 2008 seasons (37%).2 These injuries have important implications for future injury risk and time away from play. Identifying these injuries and determining correlates and risk factors is important for targeted prevention efforts.

Several studies have explored the prevalence of upper extremity injuries in professional and collegiate baseball players;2-4 however, detailed epidemiology of knee injuries in Major League Baseball (MLB) and Minor League Baseball (MiLB) players is lacking. Much more is known about the prevalence, treatment, and outcomes of knee injuries in other professional sporting organizations, such as the National Basketball Association (NBA), National Football League (NFL), and National Hockey League (NHL).4-12 A recent meta-analysis exploring injuries in professional athletes found that studies on lower extremity injuries comprised approximately 12% of the literature reporting injuries in MLB players.4 In other professional leagues, publications on lower extremity injuries comprise approximately 56% of the sports medicine literature in the NFL, 54% in the NBA, and 62% in the NHL.4 Since few studies have investigated lower extremity injuries among professional baseball players, there is an opportunity for additional research to guide evidence-based prevention strategies.

A better understanding of the nature of these injuries is one of the first steps towards developing targeted injury prevention programs and treatment algorithms. The study of injury epidemiology among professional baseball players has been aided by the creation of an injury tracking system initiated by the MLB, its minor league affiliates, and the Major League Baseball Players Association.5,13,14 This surveillance system allows for the tracking of medical histories and injuries to players as they move across major and minor league organizations. Similar systems have been utilized in the National Collegiate Athletic Association and other professional sports organizations.3,15-17 A unique advantage of the MLB surveillance system is the required participation of all major and minor league teams, which allows for investigation of the entire population of players rather than simply a sample of players from select teams. This system has propelled an effort to identify injury patterns as a means of developing appropriate targets for potential preventative measures.5

The purpose of this descriptive epidemiologic study is to better understand the distribution and characteristics of knee injuries in these elite athletes by reporting on all knee injuries occurring over a span of 4 seasons (2011-2014). Additionally, this study seeks to characterize the impact of these injuries by analyzing the time required for return to play and the treatments rendered (surgical and nonsurgical).

Materials and Methods

After approval from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board, detailed data regarding knee injuries in both MLB and MiLB baseball players were extracted from the de-identified MLB Health and Injury Tracking System (HITS). The HITS database is a centralized database that contains data on injuries from an electronic medical record (EMR). All players provided consent to have their data included in this EMR. HITS system captures injuries reported by the athletic trainers for all professional baseball players from 30 MLB clubs and their 230 minor league affiliates. Additional details on this population of professional baseball players have been published elsewhere.5 Only injuries that result in time out of play (≥1 day missed) are included in the database, and they are logged with basic information such as region of the body, diagnosis, date, player position, activity leading to injury, and general treatment. Any injury that affects participation in any aspect of baseball-related activity (eg, game, practice, warm-up, conditioning, weight training) is captured in HITS.

All baseball-related knee injuries occurring during the 2011-2014 seasons that resulted in time out of sport were included in the study. These injuries were identified based on the Sports Medicine Diagnostic Coding System (SMDCS) to capture injuries by diagnostic groups.18 Knee injuries were included if they occurred during spring training, regular season, or postseason play. Offseason injuries were not included. Injury events that were classified as “season-ending” were not included in the analysis of days missed because many of these players may not have been cleared to play until the beginning of the following season. To determine the proportion of knee injuries during the study period, all injuries were included for comparative purposes (subdivided based on 30 anatomic regions or types).

For each knee injury, a number of variables were analyzed, including diagnosis, level of play (MLB vs. MiLB), age, player position at the time of injury (pitcher, catcher, infield, outfield, base runner, or batter), field location where the injury occurred (home plate, pitcher’s mound, infield, outfield, foul territory or bullpen, or other), mechanism of injury, days missed, and treatment rendered (conservative vs surgical). The classification used to describe the mechanism of injury consisted of contact with ball, contact with ground, contact with another player, contact with another object, or noncontact.

Statistical Analysis Epidemiologic data are presented with descriptive statistics such as mean, median, frequency, and percentage where appropriate. When comparing player age, days missed, and surgical vs nonsurgical treatment between MLB and MiLB players, t-tests and tests for difference in proportions were applied as appropriate. Statistical significance was established for P values < .05.

The distribution of days missed for the variables considered was often skewed to the right (ie, days missed mostly concentrated on the low to moderate number of days, with fewer values in the much higher days missed range), even after excluding the season-ending injuries; hence the mean (or average) days missed was often larger than the median days missed. Reporting the median would allow for a robust estimate of the expected number of days missed, but would down weight those instances when knee injuries result in much longer missed days, as reflected by the mean. Because of the importance of the days missed measure for professional baseball, both the mean and median are presented.

In order to estimate exposure, the average number of players per team per game was calculated based on analysis of regular season game participation via box scores. This average number over a season, multiplied by the number of team games at each professional level of baseball, was used as an estimate of athlete exposures in order to provide rates comparable to those of other injury surveillance systems. Injury rates were reported as injuries per 1000 athlete-exposures (AE) for those knee injuries that occurred during the regular season. It should be noted that the number of regular season knee injuries and the subsequent AE rates are based on injuries that were deemed work-related during the regular season. This does not necessarily only include injuries occurring during the course of a game, but injuries in game preparation as well. Due to the variations in spring training games and fluctuating rosters, an exposure rate could not be calculated for spring training knee injuries.

RESULTS

Overall Summary

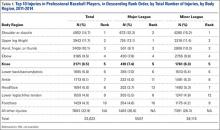

Of the 30 general body regions/systems included in the HITS database, injuries to the knee were the fifth most common reason for days missed in all of professional baseball from 2011-2014 (Table 1). Injuries to the knee represented 6.5% of the nearly 34,000 injuries sustained during the study period. Knee injuries were the fifth most common reason for time out of play for players in both the MiLB and MLB.

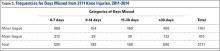

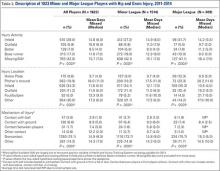

A total of 2171 isolated knee injuries resulted in time out of sport for professional baseball players (Table 2). Of these, 410 (19%) occurred in MLB players and 1761 (81%) occurred in MiLB players. MLB players were older than MiLB players at the time of injury (29.5 vs 22.8 years, respectively). Overall mean number of days missed was 16.2 days per knee injury, with MLB players missing an approximately 7 days more per injury than MiLB athletes (21.8 vs. 14.9 days respectively; P = .001).Over the course of the 4 seasons, a total of 30,449 days were missed due to knee injuries in professional baseball, giving an average rate of 7612 days lost per season. Surgery was performed for 263 (12.1%) of the 2171 knee injuries, with a greater proportion of MLB players requiring surgery than MiLB players (17.3% vs 10.9%) (P < .001). With respect to number of days missed per injury, 26% of knee injuries in the minor leagues resulted in greater than 30 days missed, while this number rose to 32% for knee injuries in MLB players (Table 3).

For regular season games, it was estimated that there were 1,197,738 MiLB and 276,608 MLB AE, respectively, over the course of the 4 seasons (2011-2014). The overall knee injury rate across both the MiLB and MLB was 1.2 per 1000 AE, based on the subset of 308 and 1473 regular season knee injuries in MiLB and MLB, respectively. The rate of knee injury was similar and not significantly different between the MiLB and MLB (1.2 per 1000 AE in the MiLB and 1.1 per 1000 AE in the MLB).

Characteristics of Injuries

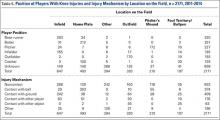

When considering the position of the player during injury, defensive players were most frequently injured (n = 742, 56.5%), with pitchers (n = 227, 17.3%), infielders (n =193, 14.7%), outfielders (n = 193, 14.7%), and catchers (n = 129, 9.8%) sustaining injuries in decreasing frequency. Injuries while on offense (n = 571, 43.5%) were most frequent in base runners (n = 320, 24.4%) followed by batters (n = 251, 19.1%) (Table 4). Injuries while on defense occurring in infielders and catchers resulted in the longest period of time away from play (average of 22.4 and 20.8 days missed, respectively), while those occurring in batters resulted in the least average days missed (8.9 days).

The most common field location for knee injuries to occur was the infield, which was responsible for n = 647 (29.8%) of the total knee injuries (Table 4). This was followed by home plate (n = 493, 22.7%), other locations outside those specified (n = 394, 18.1%), outfield (n = 320, 14.7%), pitcher’s mound (n = 210, 9.7%), and foul territory or the bullpen (n = 107, 4.9%). Of the knee injuries with a specified location, those occurring in foul territory or the bullpen resulted in the highest mean days missed (18.4), while those occurring at home plate resulted in the least mean days missed (13.4 days).

When analyzed by mechanism of injury, noncontact injuries (n = 953, 43.9%) were more common than being hit with the ball (n = 374, 17.2%), striking the ground (n = 409, 18.8%), other mechanisms not listed (n = 196, 9%), contact with another player (n = 176, 8.1%), or contact with other objects (n = 63, 2.9%) (Table 4). Noncontact injuries and player to player collisions resulted in the greatest number of missed days (21.6 and 17.1 days, respectively) while being struck by the ball resulted in the least mean days missed (5.1).

Of the n = 493 knee injuries occurring at home plate, n = 212 (43%) occurred to the batter, n = 100 (20%) to the catcher, n = 34 (6.9%) to base runners, and n = 7 (1.4%) to pitchers (Table 5). The majority of knee injuries in the infield occurred to base runners (n = 283, 43.7%). Player-to-player collisions at home plate were responsible for 51 (2.3%) knee injuries, while 163 (24%) were noncontact injuries and 376 (56%) were the result of a player being hit by the ball (Table 5).

Injury Diagnosis

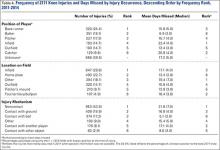

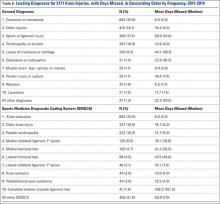

By diagnosis, the most common knee injuries observed were contusions or hematomas (n = 662, 30.5%), other injuries (n = 415, 19.1%), sprains or ligament injuries (n = 380, 17.5%), tendinopathies or bursitis (n = 367, 16.9%), and meniscal or cartilage injury (n = 200, 9.2%) (Table 6). Injuries resulting in the greatest mean number of days missed included meniscal or cartilage injuries (44 days), sprains or ligament injuries (30 days), or dislocations (22 days).

Based on specific SMDCS descriptors, the most frequent knee injuries reported were contusion (n = 662, 30.5%), patella tendinopathy (n = 222, 10.2%), and meniscal tears (n = 200, 9.2%) (Table 6). Complete anterior cruciate ligament tears, although infrequent, were responsible for the greatest mean days missed (156.2 days). This was followed by lateral meniscus tears (47.5 days) and medial meniscus tears (41.2 days). Knee contusions, although very common, resulted in the least number of days missed (6.0 days).

Discussion

Although much is known about knee injuries in other professional athletic leagues, little is known about knee injuries in professional baseball players.2-4 The majority of epidemiologic studies regarding baseball players at any level emphasizes the study of shoulder and elbow injuries.3,4,19 Since the implementation of the electronic medical record and the HITS database in professional baseball, there has been increased effort to document injuries that have received less attention in the existing literature. Understanding the epidemiology of these injuries is important for the development of targeted prevention efforts.

Prior studies of injuries in professional baseball relied on data captured by the publicly available DL. Posner and colleagues2 provide one of the most comprehensive reports on MLB injuries in a report utilizing DL assignment data over a period of 7 seasons.They demonstrated that knee injuries were responsible for 7.7% (12.5% for fielders and 3.7% for pitchers) of assignments to the DL. The current study utilized a comprehensive surveillance and builds on this existing knowledge. The present study found similar trends to Posner and colleagues2 in that knee injuries were responsible for 6.5% of injuries in professional baseball players that resulted in missed games. From the 2002 season to the 2008 season, knee injuries were the fifth most common reason MLB players were placed on the DL,2 and the current study indicates that they remain the fifth most common reason for missed time from play based on the HITS data. Since the prevalence of these injuries have remained constant since the 2002 season, efforts to better understand these injuries are warranted in order to identify strategies to prevent them. These analyses have generated important data towards achieving this understanding.

As with most injuries in professional sports, goals for treatment are aimed at maximizing patient function and performance while minimizing time out of play. For the 2011-2014 professional baseball seasons, a total of 2171 players sustained knee injuries and missed an average of 16.2 days per injury. Knee injuries were responsible for a total of 7612 days of missed work for MLB and MiLB players per season (30,449 days over the 4-season study period). This is equivalent to a total of 20.9 years of players’ time lost in professional baseball per season over the last 4 years. The implications of this amount of time away from sport are significant, and further study should be targeted at prevention of these injuries and optimizing return to play times.

When attempting to reduce the burden of knee injuries in professional baseball, it may prove beneficial to first understand how the injuries occur, where on the field, and who is at greatest risk. From 2011 to 2014, nearly 44% of knee injuries occurred by noncontact mechanisms. Among all locations on the field where knee injuries occurred, those occurring in the infield were responsible for the greatest mean days missed. The players who seem to be at greatest risk for knee injuries appear to be base runners. These data suggest the need for prevention efforts targeting base runners and infield players, as well as players in MiLB, where the largest number of injuries occurred.

Recently, playing rules implemented by MLB after consultation with players have focused on reducing the number of player-to-player collisions at home plate in an attempt to decrease the injury burden to catchers and base runners.20 This present analysis suggests that this rule change may also reduce the occurrence of knee injuries, as player collisions at home plate were responsible for a total of 51 knee injuries during the study period. The impact of this rule change on injury rates should also be explored. Interestingly, of the 51 knees injuries occurring due to contact at home plate, 23 occurred in 2011, and only 2 occurred in 2014—the first year of the new rule. Additional areas that resulted in high numbers of knee injuries were player-to-player contact in the infield and player contact with the ground in the infield.

Attempting to reduce injury burden and time out of play related to knee injuries in professional baseball players will likely prove to be a difficult task. In order to generate meaningful improvement, a comprehensive approach that involves players, management, trainers, therapists, and physicians will likely be required. As the first report of the epidemiology of knee injuries in professional baseball players, this study is one important step in that process. The strengths of this study are its comprehensive nature that analyzes injuries from an entire population of players on more than 200 teams over a 3-year period. Also, this research is strengthened by its focus on one particular region of the body that has received limited attention in the empirical literature, but represents a significant source of lost time during the baseball season.

There are some limitations to this study. As with any injury surveillance system, there is the possibility that not all cases were captured. Additionally, since the surveillance system is based on data from multiple teams, data entry discrepancy is possible; however, the presence of dropdown boxes and systematic definitions for injuries reduces this risk. Finally, this study did not investigate the various treatments for knee injuries beyond whether or not the injury required surgery. Since this was the first comprehensive exploration of knee injuries in professional baseball, future studies are needed to explore additional facets including outcomes related to treatment, return to play, and performance.

Conclusion

Knee injuries represent 6.5% of all injuries in professional baseball, occurring at a rate of 1.3 per 1000 AE. The burden of these injuries is significant for professional baseball players. This study fills a critical gap in sports injury research by contributing to the knowledge about the effect of knee injuries in professional baseball. It also provides an important foundation for future epidemiologic inquiry to identify modifiable risk factors and interventions that may reduce the impact of these injuries in athletes.

1. Conte S, Requa RK, Garrick JG. Disability days in major league baseball. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):431-436.

2. Posner M, Cameron KL, Wolf JM, Belmont PJ Jr, Owens BD. Epidemiology of Major League Baseball injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(8):1676-1680.

3. Dick R, Sauers EL, Agel J, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men’s baseball injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988-1989 through 2003-2004. J Athletic Training. 2007;42(2):183-193.

4. Makhni EC, Buza JA, Byram I, Ahmad CS. Sports reporting: A comprehensive review of the medical literature regarding North American professional sports. Phys Sportsmed. 2014;42(2):154-162.

5. Ahmad CS, Dick RW, Snell E, et al. Major and Minor League Baseball hamstring injuries: epidemiologic findings from the Major League Baseball Injury Surveillance System. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(6):1464-1470.

6. Aune KT, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, Cain EL Jr. Return to play after partial lateral meniscectomy in National Football League Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1865-1872.

7. Brophy RH, Gill CS, Lyman S, Barnes RP, Rodeo SA, Warren RF. Effect of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and meniscectomy on length of career in National Football League athletes: a case control study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2102-2107.

8. Brophy RH, Rodeo SA, Barnes RP, Powell JW, Warren RF. Knee articular cartilage injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and treatment approach by team physicians. J Knee Surg. 2009;22(4):331-338.

9. Cerynik DL, Lewullis GE, Joves BC, Palmer MP, Tom JA. Outcomes of microfracture in professional basketball players. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(9):1135-1139.

10. Hershman EB, Anderson R, Bergfeld JA, et al; National Football League Injury and Safety Panel. An analysis of specific lower extremity injury rates on grass and FieldTurf playing surfaces in National Football League Games: 2000-2009 seasons. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2200-2205.

11. Namdari S, Baldwin K, Anakwenze O, Park MJ, Huffman GR, Sennett BJ. Results and performance after microfracture in National Basketball Association athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):943-948.

12. Yeh PC, Starkey C, Lombardo S, Vitti G, Kharrazi FD. Epidemiology of isolated meniscal injury and its effect on performance in athletes from the National Basketball Association. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):589-594.

13. Pollack KM, D’Angelo J, Green G, et al. Developing and implementing major league baseball’s health and injury tracking system. Am J Epidem. (accepted), 2016.

14. Green GA, Pollack KM, D’Angelo J, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in major and Minor League Baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1118-1126.

15. Dick R, Agel J, Marshall SW. National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System commentaries: introduction and methods. J Athletic Training. 2007;42(2):173-182.

16. Pellman EJ, Viano DC, Casson IR, Arfken C, Feuer H. Concussion in professional football players returning to the same game—part 7. Neurosurg. 2005;56(1):79-90.

17. Stevens ST, Lassonde M, De Beaumont L, Keenan JP. The effect of visors on head and facial injury in national hockey league players. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9(3):238-242.

18. Meeuwisse WH, Wiley JP. The sport medicine diagnostic coding system. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(3):205-207.

19. Mcfarland EG, Wasik M. Epidemiology of collegiate baseball injuries. Clin J Sport Med. 1998;8(1):10-13.

20. Hagen P. New rule on home-plate collisions put into effect. Major League Baseball website. http://m.mlb.com/news/article/68267610/mlb-institutes-new-rule-on-home-plate-collisions. Accessed December 5, 2014.

Injuries among professional baseball players have been on the rise for several years.1,2 From 1989 to 1999, the number of disabled list (DL) reports increased 38% (266 to 367 annual reports),1 and a similar increase in injury rates was noted from the 2002 to the 2008 seasons (37%).2 These injuries have important implications for future injury risk and time away from play. Identifying these injuries and determining correlates and risk factors is important for targeted prevention efforts.

Several studies have explored the prevalence of upper extremity injuries in professional and collegiate baseball players;2-4 however, detailed epidemiology of knee injuries in Major League Baseball (MLB) and Minor League Baseball (MiLB) players is lacking. Much more is known about the prevalence, treatment, and outcomes of knee injuries in other professional sporting organizations, such as the National Basketball Association (NBA), National Football League (NFL), and National Hockey League (NHL).4-12 A recent meta-analysis exploring injuries in professional athletes found that studies on lower extremity injuries comprised approximately 12% of the literature reporting injuries in MLB players.4 In other professional leagues, publications on lower extremity injuries comprise approximately 56% of the sports medicine literature in the NFL, 54% in the NBA, and 62% in the NHL.4 Since few studies have investigated lower extremity injuries among professional baseball players, there is an opportunity for additional research to guide evidence-based prevention strategies.

A better understanding of the nature of these injuries is one of the first steps towards developing targeted injury prevention programs and treatment algorithms. The study of injury epidemiology among professional baseball players has been aided by the creation of an injury tracking system initiated by the MLB, its minor league affiliates, and the Major League Baseball Players Association.5,13,14 This surveillance system allows for the tracking of medical histories and injuries to players as they move across major and minor league organizations. Similar systems have been utilized in the National Collegiate Athletic Association and other professional sports organizations.3,15-17 A unique advantage of the MLB surveillance system is the required participation of all major and minor league teams, which allows for investigation of the entire population of players rather than simply a sample of players from select teams. This system has propelled an effort to identify injury patterns as a means of developing appropriate targets for potential preventative measures.5

The purpose of this descriptive epidemiologic study is to better understand the distribution and characteristics of knee injuries in these elite athletes by reporting on all knee injuries occurring over a span of 4 seasons (2011-2014). Additionally, this study seeks to characterize the impact of these injuries by analyzing the time required for return to play and the treatments rendered (surgical and nonsurgical).

Materials and Methods

After approval from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board, detailed data regarding knee injuries in both MLB and MiLB baseball players were extracted from the de-identified MLB Health and Injury Tracking System (HITS). The HITS database is a centralized database that contains data on injuries from an electronic medical record (EMR). All players provided consent to have their data included in this EMR. HITS system captures injuries reported by the athletic trainers for all professional baseball players from 30 MLB clubs and their 230 minor league affiliates. Additional details on this population of professional baseball players have been published elsewhere.5 Only injuries that result in time out of play (≥1 day missed) are included in the database, and they are logged with basic information such as region of the body, diagnosis, date, player position, activity leading to injury, and general treatment. Any injury that affects participation in any aspect of baseball-related activity (eg, game, practice, warm-up, conditioning, weight training) is captured in HITS.

All baseball-related knee injuries occurring during the 2011-2014 seasons that resulted in time out of sport were included in the study. These injuries were identified based on the Sports Medicine Diagnostic Coding System (SMDCS) to capture injuries by diagnostic groups.18 Knee injuries were included if they occurred during spring training, regular season, or postseason play. Offseason injuries were not included. Injury events that were classified as “season-ending” were not included in the analysis of days missed because many of these players may not have been cleared to play until the beginning of the following season. To determine the proportion of knee injuries during the study period, all injuries were included for comparative purposes (subdivided based on 30 anatomic regions or types).

For each knee injury, a number of variables were analyzed, including diagnosis, level of play (MLB vs. MiLB), age, player position at the time of injury (pitcher, catcher, infield, outfield, base runner, or batter), field location where the injury occurred (home plate, pitcher’s mound, infield, outfield, foul territory or bullpen, or other), mechanism of injury, days missed, and treatment rendered (conservative vs surgical). The classification used to describe the mechanism of injury consisted of contact with ball, contact with ground, contact with another player, contact with another object, or noncontact.

Statistical Analysis Epidemiologic data are presented with descriptive statistics such as mean, median, frequency, and percentage where appropriate. When comparing player age, days missed, and surgical vs nonsurgical treatment between MLB and MiLB players, t-tests and tests for difference in proportions were applied as appropriate. Statistical significance was established for P values < .05.

The distribution of days missed for the variables considered was often skewed to the right (ie, days missed mostly concentrated on the low to moderate number of days, with fewer values in the much higher days missed range), even after excluding the season-ending injuries; hence the mean (or average) days missed was often larger than the median days missed. Reporting the median would allow for a robust estimate of the expected number of days missed, but would down weight those instances when knee injuries result in much longer missed days, as reflected by the mean. Because of the importance of the days missed measure for professional baseball, both the mean and median are presented.

In order to estimate exposure, the average number of players per team per game was calculated based on analysis of regular season game participation via box scores. This average number over a season, multiplied by the number of team games at each professional level of baseball, was used as an estimate of athlete exposures in order to provide rates comparable to those of other injury surveillance systems. Injury rates were reported as injuries per 1000 athlete-exposures (AE) for those knee injuries that occurred during the regular season. It should be noted that the number of regular season knee injuries and the subsequent AE rates are based on injuries that were deemed work-related during the regular season. This does not necessarily only include injuries occurring during the course of a game, but injuries in game preparation as well. Due to the variations in spring training games and fluctuating rosters, an exposure rate could not be calculated for spring training knee injuries.

RESULTS

Overall Summary

Of the 30 general body regions/systems included in the HITS database, injuries to the knee were the fifth most common reason for days missed in all of professional baseball from 2011-2014 (Table 1). Injuries to the knee represented 6.5% of the nearly 34,000 injuries sustained during the study period. Knee injuries were the fifth most common reason for time out of play for players in both the MiLB and MLB.

A total of 2171 isolated knee injuries resulted in time out of sport for professional baseball players (Table 2). Of these, 410 (19%) occurred in MLB players and 1761 (81%) occurred in MiLB players. MLB players were older than MiLB players at the time of injury (29.5 vs 22.8 years, respectively). Overall mean number of days missed was 16.2 days per knee injury, with MLB players missing an approximately 7 days more per injury than MiLB athletes (21.8 vs. 14.9 days respectively; P = .001).Over the course of the 4 seasons, a total of 30,449 days were missed due to knee injuries in professional baseball, giving an average rate of 7612 days lost per season. Surgery was performed for 263 (12.1%) of the 2171 knee injuries, with a greater proportion of MLB players requiring surgery than MiLB players (17.3% vs 10.9%) (P < .001). With respect to number of days missed per injury, 26% of knee injuries in the minor leagues resulted in greater than 30 days missed, while this number rose to 32% for knee injuries in MLB players (Table 3).

For regular season games, it was estimated that there were 1,197,738 MiLB and 276,608 MLB AE, respectively, over the course of the 4 seasons (2011-2014). The overall knee injury rate across both the MiLB and MLB was 1.2 per 1000 AE, based on the subset of 308 and 1473 regular season knee injuries in MiLB and MLB, respectively. The rate of knee injury was similar and not significantly different between the MiLB and MLB (1.2 per 1000 AE in the MiLB and 1.1 per 1000 AE in the MLB).

Characteristics of Injuries

When considering the position of the player during injury, defensive players were most frequently injured (n = 742, 56.5%), with pitchers (n = 227, 17.3%), infielders (n =193, 14.7%), outfielders (n = 193, 14.7%), and catchers (n = 129, 9.8%) sustaining injuries in decreasing frequency. Injuries while on offense (n = 571, 43.5%) were most frequent in base runners (n = 320, 24.4%) followed by batters (n = 251, 19.1%) (Table 4). Injuries while on defense occurring in infielders and catchers resulted in the longest period of time away from play (average of 22.4 and 20.8 days missed, respectively), while those occurring in batters resulted in the least average days missed (8.9 days).

The most common field location for knee injuries to occur was the infield, which was responsible for n = 647 (29.8%) of the total knee injuries (Table 4). This was followed by home plate (n = 493, 22.7%), other locations outside those specified (n = 394, 18.1%), outfield (n = 320, 14.7%), pitcher’s mound (n = 210, 9.7%), and foul territory or the bullpen (n = 107, 4.9%). Of the knee injuries with a specified location, those occurring in foul territory or the bullpen resulted in the highest mean days missed (18.4), while those occurring at home plate resulted in the least mean days missed (13.4 days).

When analyzed by mechanism of injury, noncontact injuries (n = 953, 43.9%) were more common than being hit with the ball (n = 374, 17.2%), striking the ground (n = 409, 18.8%), other mechanisms not listed (n = 196, 9%), contact with another player (n = 176, 8.1%), or contact with other objects (n = 63, 2.9%) (Table 4). Noncontact injuries and player to player collisions resulted in the greatest number of missed days (21.6 and 17.1 days, respectively) while being struck by the ball resulted in the least mean days missed (5.1).

Of the n = 493 knee injuries occurring at home plate, n = 212 (43%) occurred to the batter, n = 100 (20%) to the catcher, n = 34 (6.9%) to base runners, and n = 7 (1.4%) to pitchers (Table 5). The majority of knee injuries in the infield occurred to base runners (n = 283, 43.7%). Player-to-player collisions at home plate were responsible for 51 (2.3%) knee injuries, while 163 (24%) were noncontact injuries and 376 (56%) were the result of a player being hit by the ball (Table 5).

Injury Diagnosis

By diagnosis, the most common knee injuries observed were contusions or hematomas (n = 662, 30.5%), other injuries (n = 415, 19.1%), sprains or ligament injuries (n = 380, 17.5%), tendinopathies or bursitis (n = 367, 16.9%), and meniscal or cartilage injury (n = 200, 9.2%) (Table 6). Injuries resulting in the greatest mean number of days missed included meniscal or cartilage injuries (44 days), sprains or ligament injuries (30 days), or dislocations (22 days).

Based on specific SMDCS descriptors, the most frequent knee injuries reported were contusion (n = 662, 30.5%), patella tendinopathy (n = 222, 10.2%), and meniscal tears (n = 200, 9.2%) (Table 6). Complete anterior cruciate ligament tears, although infrequent, were responsible for the greatest mean days missed (156.2 days). This was followed by lateral meniscus tears (47.5 days) and medial meniscus tears (41.2 days). Knee contusions, although very common, resulted in the least number of days missed (6.0 days).

Discussion

Although much is known about knee injuries in other professional athletic leagues, little is known about knee injuries in professional baseball players.2-4 The majority of epidemiologic studies regarding baseball players at any level emphasizes the study of shoulder and elbow injuries.3,4,19 Since the implementation of the electronic medical record and the HITS database in professional baseball, there has been increased effort to document injuries that have received less attention in the existing literature. Understanding the epidemiology of these injuries is important for the development of targeted prevention efforts.

Prior studies of injuries in professional baseball relied on data captured by the publicly available DL. Posner and colleagues2 provide one of the most comprehensive reports on MLB injuries in a report utilizing DL assignment data over a period of 7 seasons.They demonstrated that knee injuries were responsible for 7.7% (12.5% for fielders and 3.7% for pitchers) of assignments to the DL. The current study utilized a comprehensive surveillance and builds on this existing knowledge. The present study found similar trends to Posner and colleagues2 in that knee injuries were responsible for 6.5% of injuries in professional baseball players that resulted in missed games. From the 2002 season to the 2008 season, knee injuries were the fifth most common reason MLB players were placed on the DL,2 and the current study indicates that they remain the fifth most common reason for missed time from play based on the HITS data. Since the prevalence of these injuries have remained constant since the 2002 season, efforts to better understand these injuries are warranted in order to identify strategies to prevent them. These analyses have generated important data towards achieving this understanding.

As with most injuries in professional sports, goals for treatment are aimed at maximizing patient function and performance while minimizing time out of play. For the 2011-2014 professional baseball seasons, a total of 2171 players sustained knee injuries and missed an average of 16.2 days per injury. Knee injuries were responsible for a total of 7612 days of missed work for MLB and MiLB players per season (30,449 days over the 4-season study period). This is equivalent to a total of 20.9 years of players’ time lost in professional baseball per season over the last 4 years. The implications of this amount of time away from sport are significant, and further study should be targeted at prevention of these injuries and optimizing return to play times.

When attempting to reduce the burden of knee injuries in professional baseball, it may prove beneficial to first understand how the injuries occur, where on the field, and who is at greatest risk. From 2011 to 2014, nearly 44% of knee injuries occurred by noncontact mechanisms. Among all locations on the field where knee injuries occurred, those occurring in the infield were responsible for the greatest mean days missed. The players who seem to be at greatest risk for knee injuries appear to be base runners. These data suggest the need for prevention efforts targeting base runners and infield players, as well as players in MiLB, where the largest number of injuries occurred.

Recently, playing rules implemented by MLB after consultation with players have focused on reducing the number of player-to-player collisions at home plate in an attempt to decrease the injury burden to catchers and base runners.20 This present analysis suggests that this rule change may also reduce the occurrence of knee injuries, as player collisions at home plate were responsible for a total of 51 knee injuries during the study period. The impact of this rule change on injury rates should also be explored. Interestingly, of the 51 knees injuries occurring due to contact at home plate, 23 occurred in 2011, and only 2 occurred in 2014—the first year of the new rule. Additional areas that resulted in high numbers of knee injuries were player-to-player contact in the infield and player contact with the ground in the infield.

Attempting to reduce injury burden and time out of play related to knee injuries in professional baseball players will likely prove to be a difficult task. In order to generate meaningful improvement, a comprehensive approach that involves players, management, trainers, therapists, and physicians will likely be required. As the first report of the epidemiology of knee injuries in professional baseball players, this study is one important step in that process. The strengths of this study are its comprehensive nature that analyzes injuries from an entire population of players on more than 200 teams over a 3-year period. Also, this research is strengthened by its focus on one particular region of the body that has received limited attention in the empirical literature, but represents a significant source of lost time during the baseball season.

There are some limitations to this study. As with any injury surveillance system, there is the possibility that not all cases were captured. Additionally, since the surveillance system is based on data from multiple teams, data entry discrepancy is possible; however, the presence of dropdown boxes and systematic definitions for injuries reduces this risk. Finally, this study did not investigate the various treatments for knee injuries beyond whether or not the injury required surgery. Since this was the first comprehensive exploration of knee injuries in professional baseball, future studies are needed to explore additional facets including outcomes related to treatment, return to play, and performance.

Conclusion

Knee injuries represent 6.5% of all injuries in professional baseball, occurring at a rate of 1.3 per 1000 AE. The burden of these injuries is significant for professional baseball players. This study fills a critical gap in sports injury research by contributing to the knowledge about the effect of knee injuries in professional baseball. It also provides an important foundation for future epidemiologic inquiry to identify modifiable risk factors and interventions that may reduce the impact of these injuries in athletes.

Injuries among professional baseball players have been on the rise for several years.1,2 From 1989 to 1999, the number of disabled list (DL) reports increased 38% (266 to 367 annual reports),1 and a similar increase in injury rates was noted from the 2002 to the 2008 seasons (37%).2 These injuries have important implications for future injury risk and time away from play. Identifying these injuries and determining correlates and risk factors is important for targeted prevention efforts.

Several studies have explored the prevalence of upper extremity injuries in professional and collegiate baseball players;2-4 however, detailed epidemiology of knee injuries in Major League Baseball (MLB) and Minor League Baseball (MiLB) players is lacking. Much more is known about the prevalence, treatment, and outcomes of knee injuries in other professional sporting organizations, such as the National Basketball Association (NBA), National Football League (NFL), and National Hockey League (NHL).4-12 A recent meta-analysis exploring injuries in professional athletes found that studies on lower extremity injuries comprised approximately 12% of the literature reporting injuries in MLB players.4 In other professional leagues, publications on lower extremity injuries comprise approximately 56% of the sports medicine literature in the NFL, 54% in the NBA, and 62% in the NHL.4 Since few studies have investigated lower extremity injuries among professional baseball players, there is an opportunity for additional research to guide evidence-based prevention strategies.

A better understanding of the nature of these injuries is one of the first steps towards developing targeted injury prevention programs and treatment algorithms. The study of injury epidemiology among professional baseball players has been aided by the creation of an injury tracking system initiated by the MLB, its minor league affiliates, and the Major League Baseball Players Association.5,13,14 This surveillance system allows for the tracking of medical histories and injuries to players as they move across major and minor league organizations. Similar systems have been utilized in the National Collegiate Athletic Association and other professional sports organizations.3,15-17 A unique advantage of the MLB surveillance system is the required participation of all major and minor league teams, which allows for investigation of the entire population of players rather than simply a sample of players from select teams. This system has propelled an effort to identify injury patterns as a means of developing appropriate targets for potential preventative measures.5

The purpose of this descriptive epidemiologic study is to better understand the distribution and characteristics of knee injuries in these elite athletes by reporting on all knee injuries occurring over a span of 4 seasons (2011-2014). Additionally, this study seeks to characterize the impact of these injuries by analyzing the time required for return to play and the treatments rendered (surgical and nonsurgical).

Materials and Methods

After approval from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board, detailed data regarding knee injuries in both MLB and MiLB baseball players were extracted from the de-identified MLB Health and Injury Tracking System (HITS). The HITS database is a centralized database that contains data on injuries from an electronic medical record (EMR). All players provided consent to have their data included in this EMR. HITS system captures injuries reported by the athletic trainers for all professional baseball players from 30 MLB clubs and their 230 minor league affiliates. Additional details on this population of professional baseball players have been published elsewhere.5 Only injuries that result in time out of play (≥1 day missed) are included in the database, and they are logged with basic information such as region of the body, diagnosis, date, player position, activity leading to injury, and general treatment. Any injury that affects participation in any aspect of baseball-related activity (eg, game, practice, warm-up, conditioning, weight training) is captured in HITS.

All baseball-related knee injuries occurring during the 2011-2014 seasons that resulted in time out of sport were included in the study. These injuries were identified based on the Sports Medicine Diagnostic Coding System (SMDCS) to capture injuries by diagnostic groups.18 Knee injuries were included if they occurred during spring training, regular season, or postseason play. Offseason injuries were not included. Injury events that were classified as “season-ending” were not included in the analysis of days missed because many of these players may not have been cleared to play until the beginning of the following season. To determine the proportion of knee injuries during the study period, all injuries were included for comparative purposes (subdivided based on 30 anatomic regions or types).

For each knee injury, a number of variables were analyzed, including diagnosis, level of play (MLB vs. MiLB), age, player position at the time of injury (pitcher, catcher, infield, outfield, base runner, or batter), field location where the injury occurred (home plate, pitcher’s mound, infield, outfield, foul territory or bullpen, or other), mechanism of injury, days missed, and treatment rendered (conservative vs surgical). The classification used to describe the mechanism of injury consisted of contact with ball, contact with ground, contact with another player, contact with another object, or noncontact.

Statistical Analysis Epidemiologic data are presented with descriptive statistics such as mean, median, frequency, and percentage where appropriate. When comparing player age, days missed, and surgical vs nonsurgical treatment between MLB and MiLB players, t-tests and tests for difference in proportions were applied as appropriate. Statistical significance was established for P values < .05.

The distribution of days missed for the variables considered was often skewed to the right (ie, days missed mostly concentrated on the low to moderate number of days, with fewer values in the much higher days missed range), even after excluding the season-ending injuries; hence the mean (or average) days missed was often larger than the median days missed. Reporting the median would allow for a robust estimate of the expected number of days missed, but would down weight those instances when knee injuries result in much longer missed days, as reflected by the mean. Because of the importance of the days missed measure for professional baseball, both the mean and median are presented.

In order to estimate exposure, the average number of players per team per game was calculated based on analysis of regular season game participation via box scores. This average number over a season, multiplied by the number of team games at each professional level of baseball, was used as an estimate of athlete exposures in order to provide rates comparable to those of other injury surveillance systems. Injury rates were reported as injuries per 1000 athlete-exposures (AE) for those knee injuries that occurred during the regular season. It should be noted that the number of regular season knee injuries and the subsequent AE rates are based on injuries that were deemed work-related during the regular season. This does not necessarily only include injuries occurring during the course of a game, but injuries in game preparation as well. Due to the variations in spring training games and fluctuating rosters, an exposure rate could not be calculated for spring training knee injuries.

RESULTS

Overall Summary

Of the 30 general body regions/systems included in the HITS database, injuries to the knee were the fifth most common reason for days missed in all of professional baseball from 2011-2014 (Table 1). Injuries to the knee represented 6.5% of the nearly 34,000 injuries sustained during the study period. Knee injuries were the fifth most common reason for time out of play for players in both the MiLB and MLB.

A total of 2171 isolated knee injuries resulted in time out of sport for professional baseball players (Table 2). Of these, 410 (19%) occurred in MLB players and 1761 (81%) occurred in MiLB players. MLB players were older than MiLB players at the time of injury (29.5 vs 22.8 years, respectively). Overall mean number of days missed was 16.2 days per knee injury, with MLB players missing an approximately 7 days more per injury than MiLB athletes (21.8 vs. 14.9 days respectively; P = .001).Over the course of the 4 seasons, a total of 30,449 days were missed due to knee injuries in professional baseball, giving an average rate of 7612 days lost per season. Surgery was performed for 263 (12.1%) of the 2171 knee injuries, with a greater proportion of MLB players requiring surgery than MiLB players (17.3% vs 10.9%) (P < .001). With respect to number of days missed per injury, 26% of knee injuries in the minor leagues resulted in greater than 30 days missed, while this number rose to 32% for knee injuries in MLB players (Table 3).

For regular season games, it was estimated that there were 1,197,738 MiLB and 276,608 MLB AE, respectively, over the course of the 4 seasons (2011-2014). The overall knee injury rate across both the MiLB and MLB was 1.2 per 1000 AE, based on the subset of 308 and 1473 regular season knee injuries in MiLB and MLB, respectively. The rate of knee injury was similar and not significantly different between the MiLB and MLB (1.2 per 1000 AE in the MiLB and 1.1 per 1000 AE in the MLB).

Characteristics of Injuries

When considering the position of the player during injury, defensive players were most frequently injured (n = 742, 56.5%), with pitchers (n = 227, 17.3%), infielders (n =193, 14.7%), outfielders (n = 193, 14.7%), and catchers (n = 129, 9.8%) sustaining injuries in decreasing frequency. Injuries while on offense (n = 571, 43.5%) were most frequent in base runners (n = 320, 24.4%) followed by batters (n = 251, 19.1%) (Table 4). Injuries while on defense occurring in infielders and catchers resulted in the longest period of time away from play (average of 22.4 and 20.8 days missed, respectively), while those occurring in batters resulted in the least average days missed (8.9 days).

The most common field location for knee injuries to occur was the infield, which was responsible for n = 647 (29.8%) of the total knee injuries (Table 4). This was followed by home plate (n = 493, 22.7%), other locations outside those specified (n = 394, 18.1%), outfield (n = 320, 14.7%), pitcher’s mound (n = 210, 9.7%), and foul territory or the bullpen (n = 107, 4.9%). Of the knee injuries with a specified location, those occurring in foul territory or the bullpen resulted in the highest mean days missed (18.4), while those occurring at home plate resulted in the least mean days missed (13.4 days).

When analyzed by mechanism of injury, noncontact injuries (n = 953, 43.9%) were more common than being hit with the ball (n = 374, 17.2%), striking the ground (n = 409, 18.8%), other mechanisms not listed (n = 196, 9%), contact with another player (n = 176, 8.1%), or contact with other objects (n = 63, 2.9%) (Table 4). Noncontact injuries and player to player collisions resulted in the greatest number of missed days (21.6 and 17.1 days, respectively) while being struck by the ball resulted in the least mean days missed (5.1).

Of the n = 493 knee injuries occurring at home plate, n = 212 (43%) occurred to the batter, n = 100 (20%) to the catcher, n = 34 (6.9%) to base runners, and n = 7 (1.4%) to pitchers (Table 5). The majority of knee injuries in the infield occurred to base runners (n = 283, 43.7%). Player-to-player collisions at home plate were responsible for 51 (2.3%) knee injuries, while 163 (24%) were noncontact injuries and 376 (56%) were the result of a player being hit by the ball (Table 5).

Injury Diagnosis

By diagnosis, the most common knee injuries observed were contusions or hematomas (n = 662, 30.5%), other injuries (n = 415, 19.1%), sprains or ligament injuries (n = 380, 17.5%), tendinopathies or bursitis (n = 367, 16.9%), and meniscal or cartilage injury (n = 200, 9.2%) (Table 6). Injuries resulting in the greatest mean number of days missed included meniscal or cartilage injuries (44 days), sprains or ligament injuries (30 days), or dislocations (22 days).

Based on specific SMDCS descriptors, the most frequent knee injuries reported were contusion (n = 662, 30.5%), patella tendinopathy (n = 222, 10.2%), and meniscal tears (n = 200, 9.2%) (Table 6). Complete anterior cruciate ligament tears, although infrequent, were responsible for the greatest mean days missed (156.2 days). This was followed by lateral meniscus tears (47.5 days) and medial meniscus tears (41.2 days). Knee contusions, although very common, resulted in the least number of days missed (6.0 days).

Discussion

Although much is known about knee injuries in other professional athletic leagues, little is known about knee injuries in professional baseball players.2-4 The majority of epidemiologic studies regarding baseball players at any level emphasizes the study of shoulder and elbow injuries.3,4,19 Since the implementation of the electronic medical record and the HITS database in professional baseball, there has been increased effort to document injuries that have received less attention in the existing literature. Understanding the epidemiology of these injuries is important for the development of targeted prevention efforts.

Prior studies of injuries in professional baseball relied on data captured by the publicly available DL. Posner and colleagues2 provide one of the most comprehensive reports on MLB injuries in a report utilizing DL assignment data over a period of 7 seasons.They demonstrated that knee injuries were responsible for 7.7% (12.5% for fielders and 3.7% for pitchers) of assignments to the DL. The current study utilized a comprehensive surveillance and builds on this existing knowledge. The present study found similar trends to Posner and colleagues2 in that knee injuries were responsible for 6.5% of injuries in professional baseball players that resulted in missed games. From the 2002 season to the 2008 season, knee injuries were the fifth most common reason MLB players were placed on the DL,2 and the current study indicates that they remain the fifth most common reason for missed time from play based on the HITS data. Since the prevalence of these injuries have remained constant since the 2002 season, efforts to better understand these injuries are warranted in order to identify strategies to prevent them. These analyses have generated important data towards achieving this understanding.

As with most injuries in professional sports, goals for treatment are aimed at maximizing patient function and performance while minimizing time out of play. For the 2011-2014 professional baseball seasons, a total of 2171 players sustained knee injuries and missed an average of 16.2 days per injury. Knee injuries were responsible for a total of 7612 days of missed work for MLB and MiLB players per season (30,449 days over the 4-season study period). This is equivalent to a total of 20.9 years of players’ time lost in professional baseball per season over the last 4 years. The implications of this amount of time away from sport are significant, and further study should be targeted at prevention of these injuries and optimizing return to play times.

When attempting to reduce the burden of knee injuries in professional baseball, it may prove beneficial to first understand how the injuries occur, where on the field, and who is at greatest risk. From 2011 to 2014, nearly 44% of knee injuries occurred by noncontact mechanisms. Among all locations on the field where knee injuries occurred, those occurring in the infield were responsible for the greatest mean days missed. The players who seem to be at greatest risk for knee injuries appear to be base runners. These data suggest the need for prevention efforts targeting base runners and infield players, as well as players in MiLB, where the largest number of injuries occurred.

Recently, playing rules implemented by MLB after consultation with players have focused on reducing the number of player-to-player collisions at home plate in an attempt to decrease the injury burden to catchers and base runners.20 This present analysis suggests that this rule change may also reduce the occurrence of knee injuries, as player collisions at home plate were responsible for a total of 51 knee injuries during the study period. The impact of this rule change on injury rates should also be explored. Interestingly, of the 51 knees injuries occurring due to contact at home plate, 23 occurred in 2011, and only 2 occurred in 2014—the first year of the new rule. Additional areas that resulted in high numbers of knee injuries were player-to-player contact in the infield and player contact with the ground in the infield.

Attempting to reduce injury burden and time out of play related to knee injuries in professional baseball players will likely prove to be a difficult task. In order to generate meaningful improvement, a comprehensive approach that involves players, management, trainers, therapists, and physicians will likely be required. As the first report of the epidemiology of knee injuries in professional baseball players, this study is one important step in that process. The strengths of this study are its comprehensive nature that analyzes injuries from an entire population of players on more than 200 teams over a 3-year period. Also, this research is strengthened by its focus on one particular region of the body that has received limited attention in the empirical literature, but represents a significant source of lost time during the baseball season.

There are some limitations to this study. As with any injury surveillance system, there is the possibility that not all cases were captured. Additionally, since the surveillance system is based on data from multiple teams, data entry discrepancy is possible; however, the presence of dropdown boxes and systematic definitions for injuries reduces this risk. Finally, this study did not investigate the various treatments for knee injuries beyond whether or not the injury required surgery. Since this was the first comprehensive exploration of knee injuries in professional baseball, future studies are needed to explore additional facets including outcomes related to treatment, return to play, and performance.

Conclusion

Knee injuries represent 6.5% of all injuries in professional baseball, occurring at a rate of 1.3 per 1000 AE. The burden of these injuries is significant for professional baseball players. This study fills a critical gap in sports injury research by contributing to the knowledge about the effect of knee injuries in professional baseball. It also provides an important foundation for future epidemiologic inquiry to identify modifiable risk factors and interventions that may reduce the impact of these injuries in athletes.

1. Conte S, Requa RK, Garrick JG. Disability days in major league baseball. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):431-436.

2. Posner M, Cameron KL, Wolf JM, Belmont PJ Jr, Owens BD. Epidemiology of Major League Baseball injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(8):1676-1680.

3. Dick R, Sauers EL, Agel J, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men’s baseball injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988-1989 through 2003-2004. J Athletic Training. 2007;42(2):183-193.

4. Makhni EC, Buza JA, Byram I, Ahmad CS. Sports reporting: A comprehensive review of the medical literature regarding North American professional sports. Phys Sportsmed. 2014;42(2):154-162.

5. Ahmad CS, Dick RW, Snell E, et al. Major and Minor League Baseball hamstring injuries: epidemiologic findings from the Major League Baseball Injury Surveillance System. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(6):1464-1470.

6. Aune KT, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, Cain EL Jr. Return to play after partial lateral meniscectomy in National Football League Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1865-1872.

7. Brophy RH, Gill CS, Lyman S, Barnes RP, Rodeo SA, Warren RF. Effect of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and meniscectomy on length of career in National Football League athletes: a case control study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2102-2107.

8. Brophy RH, Rodeo SA, Barnes RP, Powell JW, Warren RF. Knee articular cartilage injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and treatment approach by team physicians. J Knee Surg. 2009;22(4):331-338.

9. Cerynik DL, Lewullis GE, Joves BC, Palmer MP, Tom JA. Outcomes of microfracture in professional basketball players. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(9):1135-1139.

10. Hershman EB, Anderson R, Bergfeld JA, et al; National Football League Injury and Safety Panel. An analysis of specific lower extremity injury rates on grass and FieldTurf playing surfaces in National Football League Games: 2000-2009 seasons. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2200-2205.

11. Namdari S, Baldwin K, Anakwenze O, Park MJ, Huffman GR, Sennett BJ. Results and performance after microfracture in National Basketball Association athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):943-948.

12. Yeh PC, Starkey C, Lombardo S, Vitti G, Kharrazi FD. Epidemiology of isolated meniscal injury and its effect on performance in athletes from the National Basketball Association. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):589-594.

13. Pollack KM, D’Angelo J, Green G, et al. Developing and implementing major league baseball’s health and injury tracking system. Am J Epidem. (accepted), 2016.

14. Green GA, Pollack KM, D’Angelo J, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in major and Minor League Baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1118-1126.

15. Dick R, Agel J, Marshall SW. National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System commentaries: introduction and methods. J Athletic Training. 2007;42(2):173-182.

16. Pellman EJ, Viano DC, Casson IR, Arfken C, Feuer H. Concussion in professional football players returning to the same game—part 7. Neurosurg. 2005;56(1):79-90.

17. Stevens ST, Lassonde M, De Beaumont L, Keenan JP. The effect of visors on head and facial injury in national hockey league players. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9(3):238-242.

18. Meeuwisse WH, Wiley JP. The sport medicine diagnostic coding system. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(3):205-207.

19. Mcfarland EG, Wasik M. Epidemiology of collegiate baseball injuries. Clin J Sport Med. 1998;8(1):10-13.

20. Hagen P. New rule on home-plate collisions put into effect. Major League Baseball website. http://m.mlb.com/news/article/68267610/mlb-institutes-new-rule-on-home-plate-collisions. Accessed December 5, 2014.

1. Conte S, Requa RK, Garrick JG. Disability days in major league baseball. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(4):431-436.

2. Posner M, Cameron KL, Wolf JM, Belmont PJ Jr, Owens BD. Epidemiology of Major League Baseball injuries. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(8):1676-1680.

3. Dick R, Sauers EL, Agel J, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate men’s baseball injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988-1989 through 2003-2004. J Athletic Training. 2007;42(2):183-193.

4. Makhni EC, Buza JA, Byram I, Ahmad CS. Sports reporting: A comprehensive review of the medical literature regarding North American professional sports. Phys Sportsmed. 2014;42(2):154-162.

5. Ahmad CS, Dick RW, Snell E, et al. Major and Minor League Baseball hamstring injuries: epidemiologic findings from the Major League Baseball Injury Surveillance System. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(6):1464-1470.

6. Aune KT, Andrews JR, Dugas JR, Cain EL Jr. Return to play after partial lateral meniscectomy in National Football League Athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2014;42(8):1865-1872.

7. Brophy RH, Gill CS, Lyman S, Barnes RP, Rodeo SA, Warren RF. Effect of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction and meniscectomy on length of career in National Football League athletes: a case control study. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2102-2107.

8. Brophy RH, Rodeo SA, Barnes RP, Powell JW, Warren RF. Knee articular cartilage injuries in the National Football League: epidemiology and treatment approach by team physicians. J Knee Surg. 2009;22(4):331-338.

9. Cerynik DL, Lewullis GE, Joves BC, Palmer MP, Tom JA. Outcomes of microfracture in professional basketball players. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2009;17(9):1135-1139.

10. Hershman EB, Anderson R, Bergfeld JA, et al; National Football League Injury and Safety Panel. An analysis of specific lower extremity injury rates on grass and FieldTurf playing surfaces in National Football League Games: 2000-2009 seasons. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(10):2200-2205.

11. Namdari S, Baldwin K, Anakwenze O, Park MJ, Huffman GR, Sennett BJ. Results and performance after microfracture in National Basketball Association athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(5):943-948.

12. Yeh PC, Starkey C, Lombardo S, Vitti G, Kharrazi FD. Epidemiology of isolated meniscal injury and its effect on performance in athletes from the National Basketball Association. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):589-594.

13. Pollack KM, D’Angelo J, Green G, et al. Developing and implementing major league baseball’s health and injury tracking system. Am J Epidem. (accepted), 2016.

14. Green GA, Pollack KM, D’Angelo J, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury in major and Minor League Baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43(5):1118-1126.

15. Dick R, Agel J, Marshall SW. National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System commentaries: introduction and methods. J Athletic Training. 2007;42(2):173-182.

16. Pellman EJ, Viano DC, Casson IR, Arfken C, Feuer H. Concussion in professional football players returning to the same game—part 7. Neurosurg. 2005;56(1):79-90.

17. Stevens ST, Lassonde M, De Beaumont L, Keenan JP. The effect of visors on head and facial injury in national hockey league players. J Sci Med Sport. 2006;9(3):238-242.

18. Meeuwisse WH, Wiley JP. The sport medicine diagnostic coding system. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(3):205-207.

19. Mcfarland EG, Wasik M. Epidemiology of collegiate baseball injuries. Clin J Sport Med. 1998;8(1):10-13.

20. Hagen P. New rule on home-plate collisions put into effect. Major League Baseball website. http://m.mlb.com/news/article/68267610/mlb-institutes-new-rule-on-home-plate-collisions. Accessed December 5, 2014.

The Epidemiology of Hip and Groin Injuries in Professional Baseball Players

Injuries around the hip and groin occurring in professional baseball players can present as muscle strains, avulsions, contusions, hip subluxations or dislocations, femoroacetabular impingement (FAI) causing labral tears or chondral defects, and athletic pubalgia.1-9 Several recent articles have reported on the epidemiology of musculoskeletal injuries in Major League Baseball (MLB) players4,8,10 but with little attention to injuries to the hip and groin, likely because prior studies show only a 6.3% overall incidence for these injuries, much less than the more commonly discussed shoulder or elbow injuries.8 Despite the lower proportion of hip and groin injuries overall, these injuries lead to a relatively long period of disability for the players and often have a high rate of recurrence.4,8,9

The important contribution of hip mechanics and the surrounding muscular function in the kinetic chain during overhead athletic activities, such as a tennis serve or throwing, has recently been discussed.11,12 In sports requiring overhead activities, trunk rotation is a key component to generating force, and hip internal and external rotation is necessary for this trunk rotation to occur.12,13 Alterations in hip morphology causing constrained motion, as seen in FAI, may predispose an overhead throwing athlete to intra-articular injury such as labral tears or chondral injuries, or to a compensatory movement pattern causing an extra-articular soft tissue injury about the hip.12 Decreased hip range of motion may also lead to increased forces across the upper extremity during the throwing motion, which puts the shoulder and elbow at increased risk of injury.12

Increased awareness of hip and groin injuries, advances in diagnostic imaging, and an understanding of the relationship between the throwing motion in baseball and hip mechanics have improved our ability to appropriately identify and treat athletes with injuries of the hip and groin. Several studies on hip and groin injuries in elite athletes treated both operatively and nonoperatively have reported a high rate of return to sport.3,7,14-19 A systematic review on return to sport following hip arthroscopy for intra-articular pathology associated with FAI showed a 95% return to sport rate and a 92% rate of return to pre-injury level of play in a subgroup of professional athletes in 9 studies.20

Despite the large body of literature on upper extremity injuries, there is no study specifically focusing on the epidemiology of hip and groin injuries in MLB or Minor League Baseball (MiLB) players. The incidence of all injuries in professional baseball players has steadily increased over the last 2 decades,8 and the reported incidence of hip and groin injuries will likely increase as well. The current incidence of this injury, the positions most at risk, the mechanism of injury, and the time to return to sport are important to understand given the large number of players who participate in baseball not only at a professional level, but also at an amateur level, where this information may also be applicable. This information could improve our efforts at prevention and rehabilitation of these injuries, and can guide efforts to counsel and train players at high risk of a hip or groin injury. To address this gap in the literature, the purpose of this study was to describe the epidemiology of hip and groin injuries in MLB and MiLB players from 2011 to 2014.

Materials and Methods

Population and Sample

US MLB is comprised of the major and minor leagues. The major leagues are divided into 30 clubs, with 25 active players, for a total of 750 active players. Each club has a 40-man roster consisting of 25 active players and up to 15 additional players who are either not active or optioned to the minor leagues. The minor leagues are comprised of a network of over 200 clubs that are each affiliated with a major league club, and organized by geography and level of play. The minor leagues consist of roughly 7500 players, of whom about 6500 are actively playing at any given time. The entire population of players in the MLB who sustained a hip or groin injury over the study period was eligible for this study.

Data

The MLB’s Health and Injury Tracking System (HITS) is a centralized database that contains the de-identified medical data from the electronic medical record (EMR) system. Data on all injuries are entered into the EMR by each team’s certified athletic trainer. An injury is defined as any physical complaint sustained by a player that affects or limits participation in any aspect of baseball-related activity (eg, game, practice, warm-up, conditioning, weight training). The data extracted from HITS only relates to injuries that resulted in lost game time for a player and that occurred during spring training, regular season, or postseason play; off-season injuries were not included. Injury events that were classified as “season-ending” were not included in the analysis of assessing days missed because many of these players may not have been cleared to play until the beginning of the following season. For each injury, data were collected on the diagnosis, body part, activity, location, and date of injury.

Materials and Methods

Hip and groin injuries were defined as cases having a body region variable classified as “hip/groin” or a Sports Medicine Diagnostic Coding System (SMDCS) that included any “adductor” or “hernia” or “hip pointer” labels. Cases categorized as inguinal and femoral hernia (n = 26) and testicular contusions (n = 87) were excluded. Characteristics about each hip and groin injury were also extracted from HITS. These variables included level of play, player position (activity at the time of injury), field location, injury mechanism, chronicity of the injury, and days missed. Chronicity of the injury was documented as acute, overuse, or undetermined. For level of play, the injury event was categorized as the league in which the game was played when the injury occurred. Players were excluded if they had an unknown level of play or were in the amateur league. The injuries of the hip and groin were further classified as intra-articular and extra-articular. Treatment for each injury was characterized as surgical or nonsurgical, and correlated with days missed for each type of injury.

Statistical Analysis

Data for the 2011-2014 seasons were combined, and results presented for all players and separately for MiLB and MLB. Frequencies and comparative analyses for hip and groin injuries were performed across the aforementioned injury characteristics. The distribution of days missed for the variables considered was often skewed to the right, even after excluding the season-ending injuries; hence, the mean days missed was often larger than the median days missed. Reporting the median would allow for a robust estimate of the expected number of days missed, but would down weight those instances when hip and groin injuries result in much longer missed days, as reflected by the mean. Because of the importance of the days missed measure for professional baseball, both the mean and median are presented. Chi-square tests were used to test the hypothesis of equal proportions between the various categories of hip and groin characteristics, with statistical significance determined at the P = .05 level.

In order to estimate exposure, the average number of players per team per game was calculated based on analysis of regular season game participation via box scores that are publicly available. This average number over a season, multiplied by the number of team games at each professional level of baseball, was used as an estimate of athlete exposures in order to provide rates comparable to those of other injury surveillance systems. Injury rates were reported as injuries per 1000 athlete-exposures (AE) for those hip and groin injuries that occurred during the regular season. It should be noted that the number of regular season hip and groin injuries and the subsequent AE rates are based on injuries that were deemed work-related during the regular season. This does not necessarily only include injuries occurring during the course of a game, but injuries in game preparation as well. Due to the variations in spring training games and fluctuating rosters, an exposure rate could not be calculated for spring training hip and groin injuries.

Data analysis was performed in the R statistical computing Environment (R Core Team 2014). Study procedures were approved by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Results

Overall Summary

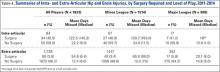

A total of 1823 hip and groin injuries occurred from 2011-2014, with 83% occurring in MiLB and 17% occurring in MLB (Table 1). There were 1146 acute injuries, 252 overuse injuries, and 425 injuries of undetermined chronicity. The average age of players experiencing a hip and groin injury in MiLB was 22.9 years compared to 29.7 years in MLB. Of the 1514 hip and groin injuries in MiLB, 76 (5.0%) required surgery and of the 309 hip and groin injuries in MLB, 24 (7.8%) required surgery. Compared to league-wide injury events, hip and groin injuries ranked 6th highest in prevalence in MiLB and 8th highest in prevalence in MLB, accounting for 5.4% and 5.6%, respectively, of the 28,116 MiLB and 5507 MLB injury events that occurred between 2011-2014.

For regular season games, it was estimated that there were 1,197,738 MiLB and 276,608 MLB AE from 2011-2014. The overall hip and groin rate across both MLB and MiLB was 1.2 per 1000 AE, based on the 238 and 1152 regular season hip and groin injuries in MLB and MiLB, respectively. The rate of hip and groin injury was 1.5 times more likely in MiLB than in MLB (P < .0001) (rate of 1.26 per 1000 AE in MiLB and 0.86 per 1000 AE in MLB).

Characteristics of Injuries