User login

Choosing the best technique for vaginal vault prolapse

- Look for vault prolapse in any woman who has an advanced degree of vaginal prolapse.

- Goals of surgery: to normalize support of all anatomic compartments; alleviate clinical symptoms; and optimize sexual, bowel, and bladder function.

- If sexual function is critical to the patient, a sacrocolpopexy should be the primary surgical option.

- Preoperative low-dose estrogen cream is crucial in most postmenopausal women.

Identifying vault prolapse can be difficult in a woman with extensive vaginal prolapse, and operative failure is likely if support to the apex is not restored.

Because this condition is so challenging to identify, many women undergoing anterior and/or posterior colporrhaphy likely have undiagnosed vault prolapse. This may contribute to the 29.2% rate of reoperation in women who undergo pelvic floor reconstructive procedures.1

This article reviews the anatomy of apical support, tells how to identify vaginal vault prolapse during the physical exam, and outlines effective surgical options—both vaginal and abdominal—for its correction. We focus on accurate pelvic assessment as the basis for planning the surgery.

Vaginal stability is fragile

The stability of vaginal anatomy is precarious, since it depends on a series of interrelationships between both dynamic and static structures. When the relationships between the ligaments and fascia at the vaginal apex or vault are impaired, vault prolapse ensues.

Thanks to cadaveric and radiographic studies, our understanding of the complexities of vaginal anatomy has improved considerably; still, the area of vaginal support we least understand is the coalescence of ligaments and fascia at the vaginal apex or vault.

Grade II prolapse, at least, in 64.8%

An analysis of Women’s Health Initiative enrollees with an intact uterus found that 64.8% had at least grade II prolapse (ie, leading edge of prolapse at –1 to +1 cm from the hymen) according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q).2 Approximately 8% of enrollees had a point D (vaginal apex) of greater than –6 cm, suggesting some degree of vault prolapse.

Hysterectomy appears to contribute. The incidence is about 1% at 3 years; 5% at 17 years.3

In the United States, approximately 30,000 vaginal vault repairs were performed in 1999.

Normal support structure

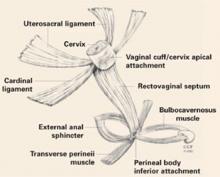

Several support structures coalesce at the vaginal apex. If the cervix is present, it serves as an obvious strong attachment site (FIGURE 1). In hysterectomized women, the structures may lack a strong attachment site, resulting in weakness and prolapse.

FIGURE 1 Vaginal support system

The coalescence of both sets of ligaments forms the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex at the vaginal apex, which is likely crucial to vault support. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

2 sets of ligaments determine support

Uterosacral ligaments—peritoneal and fibromuscular tissue bands extending from the vaginal apex to the sacrum—are the principal support for the vaginal apex, despite their apparent lack of strength.

The role of the cardinal ligaments—which extend laterally from the apex to the pelvic sidewall, adjacent to the ischial spine—is less clear. Since they lie proximal to the ureters, restoring vault support by shortening or reattaching them to the apex is a less attractive option.

The coalescence of these 2 sets of ligaments forms the complex that likely maintains vault support.

In hysterectomized women, locating the attachment of this complex to the vaginal cuff (seen on the exam as apical “dimples”) is key to identifying vault prolapse.

New view of cystoceles, rectoceles

The fibromuscular tissue layer underlying the vaginal epithelium envelops the entire vaginal canal, extending from apex to perineum and from arcus tendineus to arcus tendineus.

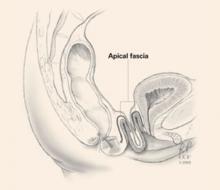

As the aponeurosis does for the abdominal wall, the endopelvic fascia maintains integrity of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. If the fascial layer detaches from the vaginal apex, a true hernia can develop in the form of an enterocele—anterior or posterior—further weakening vault integrity (FIGURE 2).

Reconstructive surgeons are beginning to view cystoceles and rectoceles as a detachment of the endopelvic fascia from the vaginal apex. Thus, it is critical to restore anterior and posterior vaginal wall fascial integrity from apex to perineum by reattaching the endogenous fascia to the vaginal apex, or by placing a biologic or synthetic graft.

FIGURE 2 Apical defects contribute to vault prolapse

Vault prolapse is often associated with defects of the apical fascia, represented here by dark lines, which must be addressed during vault reconstruction. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Specific technique, tools to help identify prolapse

Any patient with an advanced degree of vaginal prolapse should be assessed for vault prolapse using a careful, structured pelvic exam. In many cases, this can be difficult, even if the uterus is present.

Necessary tools include a bivalved speculum and a right-angle retractor, or the posterior blade of another gynecologic speculum.

When the uterus is present

An exteriorized cervix does not necessarily mean vault prolapse; this may occur with substantial cervical hypertrophy, while the apex remains well supported (FIGURE 3).

Exam technique. Place the right-angle speculum blade in the posterior fornix, inserting it to its full extent, and ask the patient to perform a Valsalva maneuver. If vault prolapse is present, the uterus will descend further as the speculum is slowly removed; reinsertion of the speculum will resuspend the uterus. If the vault is well supported, the cervix will remain in place despite Valsalva efforts.

Assess the degree of vault prolapse during this examination, to determine whether a McCall culdoplasty will restore vault support.

If uterine suspension is performed in a woman with substantial cervical hypertrophy, cervical prolapse may persist, necessitating partial amputation (Manchester procedure).

FIGURE 3 Exteriorized cervix does not necessarily mean vault prolapse

Cervical prolapse may be associated with vault prolapse (left) or simply represent cervical hypertrophy without vault prolapse (right). Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

In the hysterectomized patient

The goal of physical exam is to identify the apical scar tissue (cuff) resultant from the hysterectomy. In most women, the cuff is visible as a transverse band of tissue firmer than the adjacent vaginal walls. If the woman has extensive prolapse, the tissue is stretched and thus not as obvious.

Exam technique. Use a bivalved speculum to visualize the apex. In women with extensive prolapse, redundant vaginal tissue may impede visualization. Fortunately, the sites of previous attachment of the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex can usually be identified as “dimples” on either side of the midline at the cuff (FIGURE 4).

Use both right-angle speculum blades, or 1 blade along the anterior vaginal wall and the index and middle fingers of your other hand along the posterior vaginal wall, to identify the dimples. Then place the tip of the speculum between the dimples, elevate the vault while the patient performs a Valsalva effort, and determine the degree of vault prolapse. This can be confirmed by digital exam by identifying the dimples by tact and elevating them to their ipsilateral ischial spines.

FIGURE 4 Identifying the vault in the hysterectomized patient

Posthysterectomy vault prolapse can be identified by looking for “dimples” at the apex, which represent sites of previous uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex attachment. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Which exam findings point to which technique?

The importance of accurate pelvic assessment is impossible to overemphasize. Besides determining the degree and type of prolapse present, the exam enhances surgical planning. Fascial tears or defects are usually identifiable during careful vaginal exam as areas of sudden change in the thickness of the vaginal wall.

By the end of the pelvic exam, we usually have developed a surgical plan for the prolapse repair, pending urodynamic assessment to determine the best anti-incontinence procedure, if necessary.

What are the surgical goals?

Objectives are to normalize support of all anatomic compartments; alleviate clinical symptoms; and optimize sexual, bowel, and bladder function—without precipitating new support or functional problems.

Abdominal versus vaginal approach

Most surgeons prefer a vaginal approach to pelvic reconstruction. However, this decision should be based on the patient’s individual variables.

If sexual function is critical to the patient, a sacrocolpopexy should be the primary option. Note that age does not always predict the importance of sexual function.

Vaginal length. If the vaginal apex (dimples) reaches the ischial spines with ease, a vaginal procedure should suffice. If it does not reach the spines, or extends far above, an abdominal sacrocolpopexy or obliterative procedure may more be appropriate.

Previous reconstructive procedures. Keep in mind that the area around the sacral promontory, or sacrospinous ligaments, may be difficult or risky to reach due to scarring and fibrosis. This is doubly important in this age of commonplace graft use.

Large paravaginal defects. Vaginal repairs can be technically difficult, and long-term outcomes have not been reported. An abdominal approach is probably better if substantial paravaginal defects are present.

Medical comorbidities. Use a vaginal or obliterative procedure under regional anesthesia if the patient is medically delicate or elderly.

Tissue quality usually improves with preoperative local estrogen, but large fascial defects adjacent to the cuff or perineum may require graft reinforcement.

Colorectal dysfunction frequently coexists in women with vault prolapse. Thus, a woman with extensive rectal prolapse should probably undergo concomitant Ripstein rectopexy and sacrocolpopexy, or a perineal proctosigmoidectomy and vaginal-approach vault suspension.

Careful and consistent preparation

Surgical success depends in great part on developing a clear understanding of anatomic defects and urodynamic dysfunction during the preoperative evaluation, to determine the most appropriate procedures.

Tissue preparation with low-dose estrogen

cream (1 g, two nights per week) is crucial for most postmenopausal women.

Obtain medical clearance, and optimize

perioperative safety by using spinal anesthesia, antiembolism stockings, and prophylactic intravenous antibiotics.

Retain vaginal packing at least 24 hours to prevent stress on sutures due to coughing or vomiting.

Advise patients in advance that, for 6 weeks after surgery, they must avoid overexertion and lifting more than 5 lb.

After 6 weeks, we restart estrogen cream and prescribe routine, daily Kegel exercise.

Vaginal procedures

McCall/Mayo culdoplasty

This involves plicating the uterosacral ligaments in the midline while reefing the peritoneum in the cul-de-sac, resulting in posterior culdoplasty. It usually is performed at the time of vaginal hysterectomy using nonabsorbable sutures to incorporate both uterosacral ligaments, intervening cul-desac peritoneum, and full-thickness apical vaginal mucosa. Multiple sutures may be required if prolapse is extensive.

Generally, we try to place our uppermost suture on the uterosacral ligaments at a distance from the cuff equal to the amount of vault prolapse (POP-Q: TVL minus point D [point C if uterus is absent]).

Be careful not to injure or kink the ureters when placing the suture through the uterosacral ligaments, as the ureters lie 1 to 2 cm lateral at the level of the cervix. We recommend cystoscopy with visualization of ureteral patency.

Success rates are high, but objective long-term data is scant.4,5

Uterosacral ligament suspension

Excellent anatomic outcomes have been described when the uterosacral ligaments are reattached to the vaginal apex (similar to the McCall technique).6,7 The physiologic nature of this technique makes it very attractive. It involves opening the vaginal wall from anterior to posterior over the apical defect, and identifying the pubocervical fascia, rectovaginal fascia, and uterosacral ligaments.

Technique. Place 1 permanent 1-0 suture and 1 delayed absorbable 1-0 suture in the posteromedial aspect of each uterosacral ligament 1 to 2 cm proximal and medial to each ischial spine. Then place 1 arm of each permanent suture through the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia, and 1 arm of each delayed absorbable suture through the same tissue, also incorporating the vaginal epithelium. After repairing all additional defects, tie the sutures to suspend the vault.

When prolapse is extensive, redundant peritoneum can hinder identification of the uterosacral ligaments.

Success rates are 87% to 90%, but ureteral injury is a limiting factor, with rates as high as 11%. Therefore, cystoscopy is essential. Long-term data are lacking.

Iliococcygeus suspension

This safe and simple procedure involves elevating the vaginal apex to the iliococcygeus muscles along the lateral pelvic sidewall. This can be done without a vaginal incision by placing a monofilament permanent suture (polypropylene) full thickness through the vaginal wall into the muscle uni-or bilaterally.

Candidates should not be sexually active, as there will be a suture knot in the vagina. The procedure may be useful in elderly patients for whom complete restoration of vaginal anatomy is not a goal. It also can be performed as a salvage operation in women with suboptimal vault support and good distal vaginal anatomy. In addition, it can be performed following posterior vaginal wall dissection with entry into the pararectal space.

Technique. Place the sutures into the fascia overlying the iliococcygeus muscle, anterior to the ischial spine and inferior to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, and incorporate the pubocervical fascia anteriorly and the rectovaginal fascia posteriorly.

Success rates. Shull reported a 95% cure rate of the apical compartment among 42 women, at 6 weeks to 5 years.8 However, the prolapse at other sites was 14%. A randomized trial comparing this procedure to sacrospinous fixation demonstrated similar satisfactory outcomes.9

Sacrospinous ligament fixation

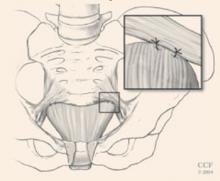

Probably the most commonly performed apical suspension procedure from the vaginal approach is fixation of the apex to the sacrospinous ligaments. Although many describe unilateral fixation, we advocate bilateral fixation to avoid lateral deviation of the vaginal axis (FIGURE 5).

Technique. After entering the pararectal space through a posterior vaginal wall dissection, identify the sacrospinous ligaments and place 2 nonabsorbable sutures through each ligament, rather than around it, as the pudendal vessels pass behind it.

Place the first suture 2 cm medial to the ischial spine, and the second suture 1 cm medial to the first. Then pass each suture through the underside of the vaginal apex—in the midline if the procedure is done unilaterally and under each apex if it is bilateral. When tied, the sutures suspend the vaginal apex by approximating it to the ligament, ideally without a suture bridge.

We use CV-2 GoreTex (WL Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, Ariz) sutures passed through the ligaments with a Miya hook, and we reinforce the underside of the vaginal apex with a rectangular piece of Prolene mesh (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) if the mucosa is thinned.

Success rates are 70% to 97%.10,11 A significant concern is the nonanatomic posterior axial deflection of the vagina. Many investigators have reported an anterior compartment prolapse rate of up to 20% after fixation, likely secondary to increased force on the anterior compartment with increases in abdominal pressure. This is especially likely if a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure is performed.

Other complications include hemorrhage, vaginal shortening, sexual dysfunction, and buttock pain.

FIGURE 5 Bilateral sacrospinous fixation avoids lateral vaginal deviation

With bilateral fixation of the vault to the sacrospinous ligaments, the vaginal axis is more horizontal. It may be reinforced to enhance longevity. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Posterior IVS vault suspension

This novel, minimally invasive technique uses the posterior intravaginal slingplasty (Posterior IVS; Tyco/US Surgical, Norwalk, Conn). First described as infracoccygeal sacropexy, it was introduced as an outpatient procedure in Australia. Concerns about postoperative vaginal length and risk of rectal injury led to poor acceptance. The procedure was modified by a few US surgeons to enhance safety and vaginal length.

Technique. Enter the pararectal space in a fashion similar to that of sacrospinous fixation. A specially designed tunneler device delivers a multifilament polypropylene tape through bilateral perianal incisions. Secure the tape to the vaginal apex, and adjust it to provide vault support.

We modified this procedure to create neoligaments analogous to cardinal ligaments, by directing the tunneler through the iliococcygeus muscles in close proximity to the ischial spines and arcus tendineus. The resultant vaginal axis is physiologic, and vaginal length is normalized.

By combining this technique with perineoplasty and attaching the rectovaginal and pubocervical fascia to the tape, all levels of pelvic support are repaired once the vault is positioned by pulling on the perianal tape ends.

The new Apogee technique (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, Minn) uses a similar perianal approach with monofilament polypropylene mesh.

Success rates. Preliminary success rates are 88% to 100%, and complication rates are minimal.12 Vaginal length averages 7 to 8 cm. Most initially reported complications involved graft erosion or rejection; shifting from nylon to polypropylene graft material reduced this problem.

Abdominal procedures

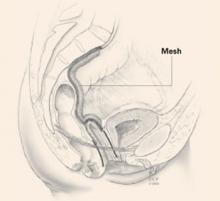

Sacral colpopexy

Considered the gold standard, the sacral colpopexy vaginal vault suspension technique has a consistent cure rate above 90%.13 It may be the ideal procedure for pelvic floor muscle weakness and/or attenuated fascia with multiple defects, for women for whom optimal sexual function is critical, and for those with other indications for abdominal surgery.

A graft is placed between the vagina and the sacral promontory to restore vaginal support (FIGURE 6). Materials have included autologous and synthetic materials. We use polypropylene mesh because of its high tensile strength, biocompatibility, low infection rate, and low incidence of erosion. Biologic grafts such as cadaveric fascia lata have increased failure rates due to graft breakdown.

The resultant vaginal axis is the most physiologic of all vault reconstructive procedures. This procedure appears to have the best longevity of all vault suspension procedures. It can be performed laparo-scopically at selected centers.

Technique. First, access the presacral space overlying the sacral promontory, taking care not to disturb the presacral and middle sacral vessels. We perform this step first to avoid potential periosteal tissue contamination. We routinely use 2 bone anchors to secure the mesh—making sterility imperative. Bone anchors reduce periosteal tissue trauma and decrease risk of potentially life-threatening hemorrhage.

Mobilize the bladder from the anterior vaginal apex. Repair any apical fascial defects, restoring continuity of the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia, which often detach from the apex. Using 2-0 Prolene sutures, suture the y-shaped graft to both the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, incorporating all fascial edges.

Culdoplasty follows; this obliterates the cul-de-sac to prevent subsequent enterocele formation.

Next, place the graft in a tension-free manner, creating a suspensory bridge from the apex to the sacral promontory. Irrigate copiously. Close the peritoneum over the graft along its entire length.

Follow with any anti-incontinence and paravaginal support procedures as well as posterior colporrhaphy as needed.14,15

Major complications include hemorrhage, usually involving periosteal perforators along the sacrum. Graft erosion may affect up to 5% to 7% of sacral colpopexies.

FIGURE 6 Mesh bridge aids vault suspension

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with a mesh bridge from the vaginal apex to the sacral promontory. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Uterosacral ligament suspension

In this procedure, which can be performed open or laparoscopically, the remnants of the uterosacral ligaments suspend the vaginal apex. The laparoscopic procedure is simple, especially if the uterus is in place.

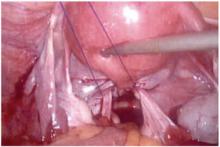

Technique. Identify the course of the ureters in relation to the ligaments, and use nonabsorbable sutures to incorporate both of the uterosacral ligaments, peritoneum, and the vaginal apex—including the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia (FIGURE 7).

Place multiple sutures (include the posterior vaginal wall) to obliterate the cul-de-sac and prevent enterocele development.

Success rates. Long-term data are minimal, but outcomes should be similar to the vaginal-approach culdoplasty.

FIGURE 7 Suspension from uterosacral ligaments

Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament suspension incorporating both uterosacral ligaments and cervix or vaginal cuff.

Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Obliterative procedures

LeForte colpocleisis or colpectomy/vaginectomy are the simplest treatments for advanced prolapse in elderly women who are not—and will not be—sexually active.16

We prefer the LeForte colpocleisis, in which rectangular segments of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls are denuded of their epithelium, followed by approximation of the rectangles to one another.

Success rates exceed 95%, and safety is maintained if spinal anesthesia is used in conjunction with a high perineoplasty.

Dr. Biller reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Davila reports research support from AMS and Tyco/US Surgical. He also serves as a consultant to AMS, and as a speaker for AMS and Tyco/US Surgical.

1. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

2. Nygaard I, Bradley C, Brandt D, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: Prevalence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:489-497.

3. Thakar R, Stanton S. Management of genital prolapse. BMJ. 2002;324:1258-1262.

4. McCall ML. Posterior culdoplasty: surgical correction of enterocele during vaginal hysterectomy. A preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol. 1957;10:595-602.

5. Webb MJ, Aronson MP, et al. Posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse: primary repair in 693 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:281-285.

6. Shull BL, Bachofen C, et al. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1365-1374.

7. Barber MD, Visco AG, et al. Bilateral uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension with site specific endopelvic fascia defect repair for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1402-1411.

8. Shull BL, Capen CV, et al. Bilateral attachment of the vaginal cuff to iliococcygeus fascia: an effective method of cuff suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1669-1677.

9. Maher CF, Murray CJ, et al. Iliococcygeus or sacrospinous fixation for vaginal vault prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:40-44.

10. Morley G, DeLancey JO. Sacrospinous ligament fixation for eversion of the vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:872.-

11. Shull BL, Capen CV, et al. Preoperative and postoperative analysis of site-specific pelvic support defects in 81 women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1764-1771.

12. Davila GW, Miller D. Vaginal vault suspension using the Posterior IVS technique. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2004;10:S39.-

13. Addison WA, Bump RC, et al. Sacral colpopexy is the preferred treatment for vaginal vault prolapse in selected patients. J Gynecol Tech. 1996;2:69-74.

14. Kohli N, Walsh PM, et al. Mesh erosion after abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:999-1004.

15. Visco AG, Weidner AC, et al. Vaginal mesh erosion after abdominal sacral colpopexy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:297-302.

16. Neimark M, Davila GW, Kopka SL. LeForte colpocleisis: a feasible treatment option for pelvic organ prolapse in the elderly woman. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2003;9:1-7.

- Look for vault prolapse in any woman who has an advanced degree of vaginal prolapse.

- Goals of surgery: to normalize support of all anatomic compartments; alleviate clinical symptoms; and optimize sexual, bowel, and bladder function.

- If sexual function is critical to the patient, a sacrocolpopexy should be the primary surgical option.

- Preoperative low-dose estrogen cream is crucial in most postmenopausal women.

Identifying vault prolapse can be difficult in a woman with extensive vaginal prolapse, and operative failure is likely if support to the apex is not restored.

Because this condition is so challenging to identify, many women undergoing anterior and/or posterior colporrhaphy likely have undiagnosed vault prolapse. This may contribute to the 29.2% rate of reoperation in women who undergo pelvic floor reconstructive procedures.1

This article reviews the anatomy of apical support, tells how to identify vaginal vault prolapse during the physical exam, and outlines effective surgical options—both vaginal and abdominal—for its correction. We focus on accurate pelvic assessment as the basis for planning the surgery.

Vaginal stability is fragile

The stability of vaginal anatomy is precarious, since it depends on a series of interrelationships between both dynamic and static structures. When the relationships between the ligaments and fascia at the vaginal apex or vault are impaired, vault prolapse ensues.

Thanks to cadaveric and radiographic studies, our understanding of the complexities of vaginal anatomy has improved considerably; still, the area of vaginal support we least understand is the coalescence of ligaments and fascia at the vaginal apex or vault.

Grade II prolapse, at least, in 64.8%

An analysis of Women’s Health Initiative enrollees with an intact uterus found that 64.8% had at least grade II prolapse (ie, leading edge of prolapse at –1 to +1 cm from the hymen) according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q).2 Approximately 8% of enrollees had a point D (vaginal apex) of greater than –6 cm, suggesting some degree of vault prolapse.

Hysterectomy appears to contribute. The incidence is about 1% at 3 years; 5% at 17 years.3

In the United States, approximately 30,000 vaginal vault repairs were performed in 1999.

Normal support structure

Several support structures coalesce at the vaginal apex. If the cervix is present, it serves as an obvious strong attachment site (FIGURE 1). In hysterectomized women, the structures may lack a strong attachment site, resulting in weakness and prolapse.

FIGURE 1 Vaginal support system

The coalescence of both sets of ligaments forms the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex at the vaginal apex, which is likely crucial to vault support. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

2 sets of ligaments determine support

Uterosacral ligaments—peritoneal and fibromuscular tissue bands extending from the vaginal apex to the sacrum—are the principal support for the vaginal apex, despite their apparent lack of strength.

The role of the cardinal ligaments—which extend laterally from the apex to the pelvic sidewall, adjacent to the ischial spine—is less clear. Since they lie proximal to the ureters, restoring vault support by shortening or reattaching them to the apex is a less attractive option.

The coalescence of these 2 sets of ligaments forms the complex that likely maintains vault support.

In hysterectomized women, locating the attachment of this complex to the vaginal cuff (seen on the exam as apical “dimples”) is key to identifying vault prolapse.

New view of cystoceles, rectoceles

The fibromuscular tissue layer underlying the vaginal epithelium envelops the entire vaginal canal, extending from apex to perineum and from arcus tendineus to arcus tendineus.

As the aponeurosis does for the abdominal wall, the endopelvic fascia maintains integrity of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. If the fascial layer detaches from the vaginal apex, a true hernia can develop in the form of an enterocele—anterior or posterior—further weakening vault integrity (FIGURE 2).

Reconstructive surgeons are beginning to view cystoceles and rectoceles as a detachment of the endopelvic fascia from the vaginal apex. Thus, it is critical to restore anterior and posterior vaginal wall fascial integrity from apex to perineum by reattaching the endogenous fascia to the vaginal apex, or by placing a biologic or synthetic graft.

FIGURE 2 Apical defects contribute to vault prolapse

Vault prolapse is often associated with defects of the apical fascia, represented here by dark lines, which must be addressed during vault reconstruction. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Specific technique, tools to help identify prolapse

Any patient with an advanced degree of vaginal prolapse should be assessed for vault prolapse using a careful, structured pelvic exam. In many cases, this can be difficult, even if the uterus is present.

Necessary tools include a bivalved speculum and a right-angle retractor, or the posterior blade of another gynecologic speculum.

When the uterus is present

An exteriorized cervix does not necessarily mean vault prolapse; this may occur with substantial cervical hypertrophy, while the apex remains well supported (FIGURE 3).

Exam technique. Place the right-angle speculum blade in the posterior fornix, inserting it to its full extent, and ask the patient to perform a Valsalva maneuver. If vault prolapse is present, the uterus will descend further as the speculum is slowly removed; reinsertion of the speculum will resuspend the uterus. If the vault is well supported, the cervix will remain in place despite Valsalva efforts.

Assess the degree of vault prolapse during this examination, to determine whether a McCall culdoplasty will restore vault support.

If uterine suspension is performed in a woman with substantial cervical hypertrophy, cervical prolapse may persist, necessitating partial amputation (Manchester procedure).

FIGURE 3 Exteriorized cervix does not necessarily mean vault prolapse

Cervical prolapse may be associated with vault prolapse (left) or simply represent cervical hypertrophy without vault prolapse (right). Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

In the hysterectomized patient

The goal of physical exam is to identify the apical scar tissue (cuff) resultant from the hysterectomy. In most women, the cuff is visible as a transverse band of tissue firmer than the adjacent vaginal walls. If the woman has extensive prolapse, the tissue is stretched and thus not as obvious.

Exam technique. Use a bivalved speculum to visualize the apex. In women with extensive prolapse, redundant vaginal tissue may impede visualization. Fortunately, the sites of previous attachment of the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex can usually be identified as “dimples” on either side of the midline at the cuff (FIGURE 4).

Use both right-angle speculum blades, or 1 blade along the anterior vaginal wall and the index and middle fingers of your other hand along the posterior vaginal wall, to identify the dimples. Then place the tip of the speculum between the dimples, elevate the vault while the patient performs a Valsalva effort, and determine the degree of vault prolapse. This can be confirmed by digital exam by identifying the dimples by tact and elevating them to their ipsilateral ischial spines.

FIGURE 4 Identifying the vault in the hysterectomized patient

Posthysterectomy vault prolapse can be identified by looking for “dimples” at the apex, which represent sites of previous uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex attachment. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Which exam findings point to which technique?

The importance of accurate pelvic assessment is impossible to overemphasize. Besides determining the degree and type of prolapse present, the exam enhances surgical planning. Fascial tears or defects are usually identifiable during careful vaginal exam as areas of sudden change in the thickness of the vaginal wall.

By the end of the pelvic exam, we usually have developed a surgical plan for the prolapse repair, pending urodynamic assessment to determine the best anti-incontinence procedure, if necessary.

What are the surgical goals?

Objectives are to normalize support of all anatomic compartments; alleviate clinical symptoms; and optimize sexual, bowel, and bladder function—without precipitating new support or functional problems.

Abdominal versus vaginal approach

Most surgeons prefer a vaginal approach to pelvic reconstruction. However, this decision should be based on the patient’s individual variables.

If sexual function is critical to the patient, a sacrocolpopexy should be the primary option. Note that age does not always predict the importance of sexual function.

Vaginal length. If the vaginal apex (dimples) reaches the ischial spines with ease, a vaginal procedure should suffice. If it does not reach the spines, or extends far above, an abdominal sacrocolpopexy or obliterative procedure may more be appropriate.

Previous reconstructive procedures. Keep in mind that the area around the sacral promontory, or sacrospinous ligaments, may be difficult or risky to reach due to scarring and fibrosis. This is doubly important in this age of commonplace graft use.

Large paravaginal defects. Vaginal repairs can be technically difficult, and long-term outcomes have not been reported. An abdominal approach is probably better if substantial paravaginal defects are present.

Medical comorbidities. Use a vaginal or obliterative procedure under regional anesthesia if the patient is medically delicate or elderly.

Tissue quality usually improves with preoperative local estrogen, but large fascial defects adjacent to the cuff or perineum may require graft reinforcement.

Colorectal dysfunction frequently coexists in women with vault prolapse. Thus, a woman with extensive rectal prolapse should probably undergo concomitant Ripstein rectopexy and sacrocolpopexy, or a perineal proctosigmoidectomy and vaginal-approach vault suspension.

Careful and consistent preparation

Surgical success depends in great part on developing a clear understanding of anatomic defects and urodynamic dysfunction during the preoperative evaluation, to determine the most appropriate procedures.

Tissue preparation with low-dose estrogen

cream (1 g, two nights per week) is crucial for most postmenopausal women.

Obtain medical clearance, and optimize

perioperative safety by using spinal anesthesia, antiembolism stockings, and prophylactic intravenous antibiotics.

Retain vaginal packing at least 24 hours to prevent stress on sutures due to coughing or vomiting.

Advise patients in advance that, for 6 weeks after surgery, they must avoid overexertion and lifting more than 5 lb.

After 6 weeks, we restart estrogen cream and prescribe routine, daily Kegel exercise.

Vaginal procedures

McCall/Mayo culdoplasty

This involves plicating the uterosacral ligaments in the midline while reefing the peritoneum in the cul-de-sac, resulting in posterior culdoplasty. It usually is performed at the time of vaginal hysterectomy using nonabsorbable sutures to incorporate both uterosacral ligaments, intervening cul-desac peritoneum, and full-thickness apical vaginal mucosa. Multiple sutures may be required if prolapse is extensive.

Generally, we try to place our uppermost suture on the uterosacral ligaments at a distance from the cuff equal to the amount of vault prolapse (POP-Q: TVL minus point D [point C if uterus is absent]).

Be careful not to injure or kink the ureters when placing the suture through the uterosacral ligaments, as the ureters lie 1 to 2 cm lateral at the level of the cervix. We recommend cystoscopy with visualization of ureteral patency.

Success rates are high, but objective long-term data is scant.4,5

Uterosacral ligament suspension

Excellent anatomic outcomes have been described when the uterosacral ligaments are reattached to the vaginal apex (similar to the McCall technique).6,7 The physiologic nature of this technique makes it very attractive. It involves opening the vaginal wall from anterior to posterior over the apical defect, and identifying the pubocervical fascia, rectovaginal fascia, and uterosacral ligaments.

Technique. Place 1 permanent 1-0 suture and 1 delayed absorbable 1-0 suture in the posteromedial aspect of each uterosacral ligament 1 to 2 cm proximal and medial to each ischial spine. Then place 1 arm of each permanent suture through the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia, and 1 arm of each delayed absorbable suture through the same tissue, also incorporating the vaginal epithelium. After repairing all additional defects, tie the sutures to suspend the vault.

When prolapse is extensive, redundant peritoneum can hinder identification of the uterosacral ligaments.

Success rates are 87% to 90%, but ureteral injury is a limiting factor, with rates as high as 11%. Therefore, cystoscopy is essential. Long-term data are lacking.

Iliococcygeus suspension

This safe and simple procedure involves elevating the vaginal apex to the iliococcygeus muscles along the lateral pelvic sidewall. This can be done without a vaginal incision by placing a monofilament permanent suture (polypropylene) full thickness through the vaginal wall into the muscle uni-or bilaterally.

Candidates should not be sexually active, as there will be a suture knot in the vagina. The procedure may be useful in elderly patients for whom complete restoration of vaginal anatomy is not a goal. It also can be performed as a salvage operation in women with suboptimal vault support and good distal vaginal anatomy. In addition, it can be performed following posterior vaginal wall dissection with entry into the pararectal space.

Technique. Place the sutures into the fascia overlying the iliococcygeus muscle, anterior to the ischial spine and inferior to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, and incorporate the pubocervical fascia anteriorly and the rectovaginal fascia posteriorly.

Success rates. Shull reported a 95% cure rate of the apical compartment among 42 women, at 6 weeks to 5 years.8 However, the prolapse at other sites was 14%. A randomized trial comparing this procedure to sacrospinous fixation demonstrated similar satisfactory outcomes.9

Sacrospinous ligament fixation

Probably the most commonly performed apical suspension procedure from the vaginal approach is fixation of the apex to the sacrospinous ligaments. Although many describe unilateral fixation, we advocate bilateral fixation to avoid lateral deviation of the vaginal axis (FIGURE 5).

Technique. After entering the pararectal space through a posterior vaginal wall dissection, identify the sacrospinous ligaments and place 2 nonabsorbable sutures through each ligament, rather than around it, as the pudendal vessels pass behind it.

Place the first suture 2 cm medial to the ischial spine, and the second suture 1 cm medial to the first. Then pass each suture through the underside of the vaginal apex—in the midline if the procedure is done unilaterally and under each apex if it is bilateral. When tied, the sutures suspend the vaginal apex by approximating it to the ligament, ideally without a suture bridge.

We use CV-2 GoreTex (WL Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, Ariz) sutures passed through the ligaments with a Miya hook, and we reinforce the underside of the vaginal apex with a rectangular piece of Prolene mesh (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) if the mucosa is thinned.

Success rates are 70% to 97%.10,11 A significant concern is the nonanatomic posterior axial deflection of the vagina. Many investigators have reported an anterior compartment prolapse rate of up to 20% after fixation, likely secondary to increased force on the anterior compartment with increases in abdominal pressure. This is especially likely if a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure is performed.

Other complications include hemorrhage, vaginal shortening, sexual dysfunction, and buttock pain.

FIGURE 5 Bilateral sacrospinous fixation avoids lateral vaginal deviation

With bilateral fixation of the vault to the sacrospinous ligaments, the vaginal axis is more horizontal. It may be reinforced to enhance longevity. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Posterior IVS vault suspension

This novel, minimally invasive technique uses the posterior intravaginal slingplasty (Posterior IVS; Tyco/US Surgical, Norwalk, Conn). First described as infracoccygeal sacropexy, it was introduced as an outpatient procedure in Australia. Concerns about postoperative vaginal length and risk of rectal injury led to poor acceptance. The procedure was modified by a few US surgeons to enhance safety and vaginal length.

Technique. Enter the pararectal space in a fashion similar to that of sacrospinous fixation. A specially designed tunneler device delivers a multifilament polypropylene tape through bilateral perianal incisions. Secure the tape to the vaginal apex, and adjust it to provide vault support.

We modified this procedure to create neoligaments analogous to cardinal ligaments, by directing the tunneler through the iliococcygeus muscles in close proximity to the ischial spines and arcus tendineus. The resultant vaginal axis is physiologic, and vaginal length is normalized.

By combining this technique with perineoplasty and attaching the rectovaginal and pubocervical fascia to the tape, all levels of pelvic support are repaired once the vault is positioned by pulling on the perianal tape ends.

The new Apogee technique (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, Minn) uses a similar perianal approach with monofilament polypropylene mesh.

Success rates. Preliminary success rates are 88% to 100%, and complication rates are minimal.12 Vaginal length averages 7 to 8 cm. Most initially reported complications involved graft erosion or rejection; shifting from nylon to polypropylene graft material reduced this problem.

Abdominal procedures

Sacral colpopexy

Considered the gold standard, the sacral colpopexy vaginal vault suspension technique has a consistent cure rate above 90%.13 It may be the ideal procedure for pelvic floor muscle weakness and/or attenuated fascia with multiple defects, for women for whom optimal sexual function is critical, and for those with other indications for abdominal surgery.

A graft is placed between the vagina and the sacral promontory to restore vaginal support (FIGURE 6). Materials have included autologous and synthetic materials. We use polypropylene mesh because of its high tensile strength, biocompatibility, low infection rate, and low incidence of erosion. Biologic grafts such as cadaveric fascia lata have increased failure rates due to graft breakdown.

The resultant vaginal axis is the most physiologic of all vault reconstructive procedures. This procedure appears to have the best longevity of all vault suspension procedures. It can be performed laparo-scopically at selected centers.

Technique. First, access the presacral space overlying the sacral promontory, taking care not to disturb the presacral and middle sacral vessels. We perform this step first to avoid potential periosteal tissue contamination. We routinely use 2 bone anchors to secure the mesh—making sterility imperative. Bone anchors reduce periosteal tissue trauma and decrease risk of potentially life-threatening hemorrhage.

Mobilize the bladder from the anterior vaginal apex. Repair any apical fascial defects, restoring continuity of the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia, which often detach from the apex. Using 2-0 Prolene sutures, suture the y-shaped graft to both the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, incorporating all fascial edges.

Culdoplasty follows; this obliterates the cul-de-sac to prevent subsequent enterocele formation.

Next, place the graft in a tension-free manner, creating a suspensory bridge from the apex to the sacral promontory. Irrigate copiously. Close the peritoneum over the graft along its entire length.

Follow with any anti-incontinence and paravaginal support procedures as well as posterior colporrhaphy as needed.14,15

Major complications include hemorrhage, usually involving periosteal perforators along the sacrum. Graft erosion may affect up to 5% to 7% of sacral colpopexies.

FIGURE 6 Mesh bridge aids vault suspension

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with a mesh bridge from the vaginal apex to the sacral promontory. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Uterosacral ligament suspension

In this procedure, which can be performed open or laparoscopically, the remnants of the uterosacral ligaments suspend the vaginal apex. The laparoscopic procedure is simple, especially if the uterus is in place.

Technique. Identify the course of the ureters in relation to the ligaments, and use nonabsorbable sutures to incorporate both of the uterosacral ligaments, peritoneum, and the vaginal apex—including the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia (FIGURE 7).

Place multiple sutures (include the posterior vaginal wall) to obliterate the cul-de-sac and prevent enterocele development.

Success rates. Long-term data are minimal, but outcomes should be similar to the vaginal-approach culdoplasty.

FIGURE 7 Suspension from uterosacral ligaments

Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament suspension incorporating both uterosacral ligaments and cervix or vaginal cuff.

Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Obliterative procedures

LeForte colpocleisis or colpectomy/vaginectomy are the simplest treatments for advanced prolapse in elderly women who are not—and will not be—sexually active.16

We prefer the LeForte colpocleisis, in which rectangular segments of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls are denuded of their epithelium, followed by approximation of the rectangles to one another.

Success rates exceed 95%, and safety is maintained if spinal anesthesia is used in conjunction with a high perineoplasty.

Dr. Biller reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Davila reports research support from AMS and Tyco/US Surgical. He also serves as a consultant to AMS, and as a speaker for AMS and Tyco/US Surgical.

- Look for vault prolapse in any woman who has an advanced degree of vaginal prolapse.

- Goals of surgery: to normalize support of all anatomic compartments; alleviate clinical symptoms; and optimize sexual, bowel, and bladder function.

- If sexual function is critical to the patient, a sacrocolpopexy should be the primary surgical option.

- Preoperative low-dose estrogen cream is crucial in most postmenopausal women.

Identifying vault prolapse can be difficult in a woman with extensive vaginal prolapse, and operative failure is likely if support to the apex is not restored.

Because this condition is so challenging to identify, many women undergoing anterior and/or posterior colporrhaphy likely have undiagnosed vault prolapse. This may contribute to the 29.2% rate of reoperation in women who undergo pelvic floor reconstructive procedures.1

This article reviews the anatomy of apical support, tells how to identify vaginal vault prolapse during the physical exam, and outlines effective surgical options—both vaginal and abdominal—for its correction. We focus on accurate pelvic assessment as the basis for planning the surgery.

Vaginal stability is fragile

The stability of vaginal anatomy is precarious, since it depends on a series of interrelationships between both dynamic and static structures. When the relationships between the ligaments and fascia at the vaginal apex or vault are impaired, vault prolapse ensues.

Thanks to cadaveric and radiographic studies, our understanding of the complexities of vaginal anatomy has improved considerably; still, the area of vaginal support we least understand is the coalescence of ligaments and fascia at the vaginal apex or vault.

Grade II prolapse, at least, in 64.8%

An analysis of Women’s Health Initiative enrollees with an intact uterus found that 64.8% had at least grade II prolapse (ie, leading edge of prolapse at –1 to +1 cm from the hymen) according to the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q).2 Approximately 8% of enrollees had a point D (vaginal apex) of greater than –6 cm, suggesting some degree of vault prolapse.

Hysterectomy appears to contribute. The incidence is about 1% at 3 years; 5% at 17 years.3

In the United States, approximately 30,000 vaginal vault repairs were performed in 1999.

Normal support structure

Several support structures coalesce at the vaginal apex. If the cervix is present, it serves as an obvious strong attachment site (FIGURE 1). In hysterectomized women, the structures may lack a strong attachment site, resulting in weakness and prolapse.

FIGURE 1 Vaginal support system

The coalescence of both sets of ligaments forms the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex at the vaginal apex, which is likely crucial to vault support. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

2 sets of ligaments determine support

Uterosacral ligaments—peritoneal and fibromuscular tissue bands extending from the vaginal apex to the sacrum—are the principal support for the vaginal apex, despite their apparent lack of strength.

The role of the cardinal ligaments—which extend laterally from the apex to the pelvic sidewall, adjacent to the ischial spine—is less clear. Since they lie proximal to the ureters, restoring vault support by shortening or reattaching them to the apex is a less attractive option.

The coalescence of these 2 sets of ligaments forms the complex that likely maintains vault support.

In hysterectomized women, locating the attachment of this complex to the vaginal cuff (seen on the exam as apical “dimples”) is key to identifying vault prolapse.

New view of cystoceles, rectoceles

The fibromuscular tissue layer underlying the vaginal epithelium envelops the entire vaginal canal, extending from apex to perineum and from arcus tendineus to arcus tendineus.

As the aponeurosis does for the abdominal wall, the endopelvic fascia maintains integrity of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls. If the fascial layer detaches from the vaginal apex, a true hernia can develop in the form of an enterocele—anterior or posterior—further weakening vault integrity (FIGURE 2).

Reconstructive surgeons are beginning to view cystoceles and rectoceles as a detachment of the endopelvic fascia from the vaginal apex. Thus, it is critical to restore anterior and posterior vaginal wall fascial integrity from apex to perineum by reattaching the endogenous fascia to the vaginal apex, or by placing a biologic or synthetic graft.

FIGURE 2 Apical defects contribute to vault prolapse

Vault prolapse is often associated with defects of the apical fascia, represented here by dark lines, which must be addressed during vault reconstruction. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Specific technique, tools to help identify prolapse

Any patient with an advanced degree of vaginal prolapse should be assessed for vault prolapse using a careful, structured pelvic exam. In many cases, this can be difficult, even if the uterus is present.

Necessary tools include a bivalved speculum and a right-angle retractor, or the posterior blade of another gynecologic speculum.

When the uterus is present

An exteriorized cervix does not necessarily mean vault prolapse; this may occur with substantial cervical hypertrophy, while the apex remains well supported (FIGURE 3).

Exam technique. Place the right-angle speculum blade in the posterior fornix, inserting it to its full extent, and ask the patient to perform a Valsalva maneuver. If vault prolapse is present, the uterus will descend further as the speculum is slowly removed; reinsertion of the speculum will resuspend the uterus. If the vault is well supported, the cervix will remain in place despite Valsalva efforts.

Assess the degree of vault prolapse during this examination, to determine whether a McCall culdoplasty will restore vault support.

If uterine suspension is performed in a woman with substantial cervical hypertrophy, cervical prolapse may persist, necessitating partial amputation (Manchester procedure).

FIGURE 3 Exteriorized cervix does not necessarily mean vault prolapse

Cervical prolapse may be associated with vault prolapse (left) or simply represent cervical hypertrophy without vault prolapse (right). Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

In the hysterectomized patient

The goal of physical exam is to identify the apical scar tissue (cuff) resultant from the hysterectomy. In most women, the cuff is visible as a transverse band of tissue firmer than the adjacent vaginal walls. If the woman has extensive prolapse, the tissue is stretched and thus not as obvious.

Exam technique. Use a bivalved speculum to visualize the apex. In women with extensive prolapse, redundant vaginal tissue may impede visualization. Fortunately, the sites of previous attachment of the uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex can usually be identified as “dimples” on either side of the midline at the cuff (FIGURE 4).

Use both right-angle speculum blades, or 1 blade along the anterior vaginal wall and the index and middle fingers of your other hand along the posterior vaginal wall, to identify the dimples. Then place the tip of the speculum between the dimples, elevate the vault while the patient performs a Valsalva effort, and determine the degree of vault prolapse. This can be confirmed by digital exam by identifying the dimples by tact and elevating them to their ipsilateral ischial spines.

FIGURE 4 Identifying the vault in the hysterectomized patient

Posthysterectomy vault prolapse can be identified by looking for “dimples” at the apex, which represent sites of previous uterosacral-cardinal ligament complex attachment. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Which exam findings point to which technique?

The importance of accurate pelvic assessment is impossible to overemphasize. Besides determining the degree and type of prolapse present, the exam enhances surgical planning. Fascial tears or defects are usually identifiable during careful vaginal exam as areas of sudden change in the thickness of the vaginal wall.

By the end of the pelvic exam, we usually have developed a surgical plan for the prolapse repair, pending urodynamic assessment to determine the best anti-incontinence procedure, if necessary.

What are the surgical goals?

Objectives are to normalize support of all anatomic compartments; alleviate clinical symptoms; and optimize sexual, bowel, and bladder function—without precipitating new support or functional problems.

Abdominal versus vaginal approach

Most surgeons prefer a vaginal approach to pelvic reconstruction. However, this decision should be based on the patient’s individual variables.

If sexual function is critical to the patient, a sacrocolpopexy should be the primary option. Note that age does not always predict the importance of sexual function.

Vaginal length. If the vaginal apex (dimples) reaches the ischial spines with ease, a vaginal procedure should suffice. If it does not reach the spines, or extends far above, an abdominal sacrocolpopexy or obliterative procedure may more be appropriate.

Previous reconstructive procedures. Keep in mind that the area around the sacral promontory, or sacrospinous ligaments, may be difficult or risky to reach due to scarring and fibrosis. This is doubly important in this age of commonplace graft use.

Large paravaginal defects. Vaginal repairs can be technically difficult, and long-term outcomes have not been reported. An abdominal approach is probably better if substantial paravaginal defects are present.

Medical comorbidities. Use a vaginal or obliterative procedure under regional anesthesia if the patient is medically delicate or elderly.

Tissue quality usually improves with preoperative local estrogen, but large fascial defects adjacent to the cuff or perineum may require graft reinforcement.

Colorectal dysfunction frequently coexists in women with vault prolapse. Thus, a woman with extensive rectal prolapse should probably undergo concomitant Ripstein rectopexy and sacrocolpopexy, or a perineal proctosigmoidectomy and vaginal-approach vault suspension.

Careful and consistent preparation

Surgical success depends in great part on developing a clear understanding of anatomic defects and urodynamic dysfunction during the preoperative evaluation, to determine the most appropriate procedures.

Tissue preparation with low-dose estrogen

cream (1 g, two nights per week) is crucial for most postmenopausal women.

Obtain medical clearance, and optimize

perioperative safety by using spinal anesthesia, antiembolism stockings, and prophylactic intravenous antibiotics.

Retain vaginal packing at least 24 hours to prevent stress on sutures due to coughing or vomiting.

Advise patients in advance that, for 6 weeks after surgery, they must avoid overexertion and lifting more than 5 lb.

After 6 weeks, we restart estrogen cream and prescribe routine, daily Kegel exercise.

Vaginal procedures

McCall/Mayo culdoplasty

This involves plicating the uterosacral ligaments in the midline while reefing the peritoneum in the cul-de-sac, resulting in posterior culdoplasty. It usually is performed at the time of vaginal hysterectomy using nonabsorbable sutures to incorporate both uterosacral ligaments, intervening cul-desac peritoneum, and full-thickness apical vaginal mucosa. Multiple sutures may be required if prolapse is extensive.

Generally, we try to place our uppermost suture on the uterosacral ligaments at a distance from the cuff equal to the amount of vault prolapse (POP-Q: TVL minus point D [point C if uterus is absent]).

Be careful not to injure or kink the ureters when placing the suture through the uterosacral ligaments, as the ureters lie 1 to 2 cm lateral at the level of the cervix. We recommend cystoscopy with visualization of ureteral patency.

Success rates are high, but objective long-term data is scant.4,5

Uterosacral ligament suspension

Excellent anatomic outcomes have been described when the uterosacral ligaments are reattached to the vaginal apex (similar to the McCall technique).6,7 The physiologic nature of this technique makes it very attractive. It involves opening the vaginal wall from anterior to posterior over the apical defect, and identifying the pubocervical fascia, rectovaginal fascia, and uterosacral ligaments.

Technique. Place 1 permanent 1-0 suture and 1 delayed absorbable 1-0 suture in the posteromedial aspect of each uterosacral ligament 1 to 2 cm proximal and medial to each ischial spine. Then place 1 arm of each permanent suture through the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia, and 1 arm of each delayed absorbable suture through the same tissue, also incorporating the vaginal epithelium. After repairing all additional defects, tie the sutures to suspend the vault.

When prolapse is extensive, redundant peritoneum can hinder identification of the uterosacral ligaments.

Success rates are 87% to 90%, but ureteral injury is a limiting factor, with rates as high as 11%. Therefore, cystoscopy is essential. Long-term data are lacking.

Iliococcygeus suspension

This safe and simple procedure involves elevating the vaginal apex to the iliococcygeus muscles along the lateral pelvic sidewall. This can be done without a vaginal incision by placing a monofilament permanent suture (polypropylene) full thickness through the vaginal wall into the muscle uni-or bilaterally.

Candidates should not be sexually active, as there will be a suture knot in the vagina. The procedure may be useful in elderly patients for whom complete restoration of vaginal anatomy is not a goal. It also can be performed as a salvage operation in women with suboptimal vault support and good distal vaginal anatomy. In addition, it can be performed following posterior vaginal wall dissection with entry into the pararectal space.

Technique. Place the sutures into the fascia overlying the iliococcygeus muscle, anterior to the ischial spine and inferior to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis, and incorporate the pubocervical fascia anteriorly and the rectovaginal fascia posteriorly.

Success rates. Shull reported a 95% cure rate of the apical compartment among 42 women, at 6 weeks to 5 years.8 However, the prolapse at other sites was 14%. A randomized trial comparing this procedure to sacrospinous fixation demonstrated similar satisfactory outcomes.9

Sacrospinous ligament fixation

Probably the most commonly performed apical suspension procedure from the vaginal approach is fixation of the apex to the sacrospinous ligaments. Although many describe unilateral fixation, we advocate bilateral fixation to avoid lateral deviation of the vaginal axis (FIGURE 5).

Technique. After entering the pararectal space through a posterior vaginal wall dissection, identify the sacrospinous ligaments and place 2 nonabsorbable sutures through each ligament, rather than around it, as the pudendal vessels pass behind it.

Place the first suture 2 cm medial to the ischial spine, and the second suture 1 cm medial to the first. Then pass each suture through the underside of the vaginal apex—in the midline if the procedure is done unilaterally and under each apex if it is bilateral. When tied, the sutures suspend the vaginal apex by approximating it to the ligament, ideally without a suture bridge.

We use CV-2 GoreTex (WL Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, Ariz) sutures passed through the ligaments with a Miya hook, and we reinforce the underside of the vaginal apex with a rectangular piece of Prolene mesh (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ) if the mucosa is thinned.

Success rates are 70% to 97%.10,11 A significant concern is the nonanatomic posterior axial deflection of the vagina. Many investigators have reported an anterior compartment prolapse rate of up to 20% after fixation, likely secondary to increased force on the anterior compartment with increases in abdominal pressure. This is especially likely if a concomitant anti-incontinence procedure is performed.

Other complications include hemorrhage, vaginal shortening, sexual dysfunction, and buttock pain.

FIGURE 5 Bilateral sacrospinous fixation avoids lateral vaginal deviation

With bilateral fixation of the vault to the sacrospinous ligaments, the vaginal axis is more horizontal. It may be reinforced to enhance longevity. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Posterior IVS vault suspension

This novel, minimally invasive technique uses the posterior intravaginal slingplasty (Posterior IVS; Tyco/US Surgical, Norwalk, Conn). First described as infracoccygeal sacropexy, it was introduced as an outpatient procedure in Australia. Concerns about postoperative vaginal length and risk of rectal injury led to poor acceptance. The procedure was modified by a few US surgeons to enhance safety and vaginal length.

Technique. Enter the pararectal space in a fashion similar to that of sacrospinous fixation. A specially designed tunneler device delivers a multifilament polypropylene tape through bilateral perianal incisions. Secure the tape to the vaginal apex, and adjust it to provide vault support.

We modified this procedure to create neoligaments analogous to cardinal ligaments, by directing the tunneler through the iliococcygeus muscles in close proximity to the ischial spines and arcus tendineus. The resultant vaginal axis is physiologic, and vaginal length is normalized.

By combining this technique with perineoplasty and attaching the rectovaginal and pubocervical fascia to the tape, all levels of pelvic support are repaired once the vault is positioned by pulling on the perianal tape ends.

The new Apogee technique (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, Minn) uses a similar perianal approach with monofilament polypropylene mesh.

Success rates. Preliminary success rates are 88% to 100%, and complication rates are minimal.12 Vaginal length averages 7 to 8 cm. Most initially reported complications involved graft erosion or rejection; shifting from nylon to polypropylene graft material reduced this problem.

Abdominal procedures

Sacral colpopexy

Considered the gold standard, the sacral colpopexy vaginal vault suspension technique has a consistent cure rate above 90%.13 It may be the ideal procedure for pelvic floor muscle weakness and/or attenuated fascia with multiple defects, for women for whom optimal sexual function is critical, and for those with other indications for abdominal surgery.

A graft is placed between the vagina and the sacral promontory to restore vaginal support (FIGURE 6). Materials have included autologous and synthetic materials. We use polypropylene mesh because of its high tensile strength, biocompatibility, low infection rate, and low incidence of erosion. Biologic grafts such as cadaveric fascia lata have increased failure rates due to graft breakdown.

The resultant vaginal axis is the most physiologic of all vault reconstructive procedures. This procedure appears to have the best longevity of all vault suspension procedures. It can be performed laparo-scopically at selected centers.

Technique. First, access the presacral space overlying the sacral promontory, taking care not to disturb the presacral and middle sacral vessels. We perform this step first to avoid potential periosteal tissue contamination. We routinely use 2 bone anchors to secure the mesh—making sterility imperative. Bone anchors reduce periosteal tissue trauma and decrease risk of potentially life-threatening hemorrhage.

Mobilize the bladder from the anterior vaginal apex. Repair any apical fascial defects, restoring continuity of the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia, which often detach from the apex. Using 2-0 Prolene sutures, suture the y-shaped graft to both the anterior and posterior vaginal walls, incorporating all fascial edges.

Culdoplasty follows; this obliterates the cul-de-sac to prevent subsequent enterocele formation.

Next, place the graft in a tension-free manner, creating a suspensory bridge from the apex to the sacral promontory. Irrigate copiously. Close the peritoneum over the graft along its entire length.

Follow with any anti-incontinence and paravaginal support procedures as well as posterior colporrhaphy as needed.14,15

Major complications include hemorrhage, usually involving periosteal perforators along the sacrum. Graft erosion may affect up to 5% to 7% of sacral colpopexies.

FIGURE 6 Mesh bridge aids vault suspension

Abdominal sacrocolpopexy with a mesh bridge from the vaginal apex to the sacral promontory. Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Uterosacral ligament suspension

In this procedure, which can be performed open or laparoscopically, the remnants of the uterosacral ligaments suspend the vaginal apex. The laparoscopic procedure is simple, especially if the uterus is in place.

Technique. Identify the course of the ureters in relation to the ligaments, and use nonabsorbable sutures to incorporate both of the uterosacral ligaments, peritoneum, and the vaginal apex—including the pubocervical and rectovaginal fascia (FIGURE 7).

Place multiple sutures (include the posterior vaginal wall) to obliterate the cul-de-sac and prevent enterocele development.

Success rates. Long-term data are minimal, but outcomes should be similar to the vaginal-approach culdoplasty.

FIGURE 7 Suspension from uterosacral ligaments

Laparoscopic uterosacral ligament suspension incorporating both uterosacral ligaments and cervix or vaginal cuff.

Reprinted with permission of The Cleveland Clinic Foundation.

Obliterative procedures

LeForte colpocleisis or colpectomy/vaginectomy are the simplest treatments for advanced prolapse in elderly women who are not—and will not be—sexually active.16

We prefer the LeForte colpocleisis, in which rectangular segments of the anterior and posterior vaginal walls are denuded of their epithelium, followed by approximation of the rectangles to one another.

Success rates exceed 95%, and safety is maintained if spinal anesthesia is used in conjunction with a high perineoplasty.

Dr. Biller reports no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Davila reports research support from AMS and Tyco/US Surgical. He also serves as a consultant to AMS, and as a speaker for AMS and Tyco/US Surgical.

1. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

2. Nygaard I, Bradley C, Brandt D, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: Prevalence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:489-497.

3. Thakar R, Stanton S. Management of genital prolapse. BMJ. 2002;324:1258-1262.

4. McCall ML. Posterior culdoplasty: surgical correction of enterocele during vaginal hysterectomy. A preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol. 1957;10:595-602.

5. Webb MJ, Aronson MP, et al. Posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse: primary repair in 693 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:281-285.

6. Shull BL, Bachofen C, et al. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1365-1374.

7. Barber MD, Visco AG, et al. Bilateral uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension with site specific endopelvic fascia defect repair for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1402-1411.

8. Shull BL, Capen CV, et al. Bilateral attachment of the vaginal cuff to iliococcygeus fascia: an effective method of cuff suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1669-1677.

9. Maher CF, Murray CJ, et al. Iliococcygeus or sacrospinous fixation for vaginal vault prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:40-44.

10. Morley G, DeLancey JO. Sacrospinous ligament fixation for eversion of the vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:872.-

11. Shull BL, Capen CV, et al. Preoperative and postoperative analysis of site-specific pelvic support defects in 81 women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1764-1771.

12. Davila GW, Miller D. Vaginal vault suspension using the Posterior IVS technique. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2004;10:S39.-

13. Addison WA, Bump RC, et al. Sacral colpopexy is the preferred treatment for vaginal vault prolapse in selected patients. J Gynecol Tech. 1996;2:69-74.

14. Kohli N, Walsh PM, et al. Mesh erosion after abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:999-1004.

15. Visco AG, Weidner AC, et al. Vaginal mesh erosion after abdominal sacral colpopexy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:297-302.

16. Neimark M, Davila GW, Kopka SL. LeForte colpocleisis: a feasible treatment option for pelvic organ prolapse in the elderly woman. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2003;9:1-7.

1. Olsen AL, Smith VJ, et al. Epidemiology of surgically managed pelvic organ prolapse and urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:501-506.

2. Nygaard I, Bradley C, Brandt D, et al. Pelvic organ prolapse in older women: Prevalence and risk factors. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:489-497.

3. Thakar R, Stanton S. Management of genital prolapse. BMJ. 2002;324:1258-1262.

4. McCall ML. Posterior culdoplasty: surgical correction of enterocele during vaginal hysterectomy. A preliminary report. Obstet Gynecol. 1957;10:595-602.

5. Webb MJ, Aronson MP, et al. Posthysterectomy vaginal vault prolapse: primary repair in 693 patients. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:281-285.

6. Shull BL, Bachofen C, et al. A transvaginal approach to repair of apical and other associated sites of pelvic organ prolapse with uterosacral ligaments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1365-1374.

7. Barber MD, Visco AG, et al. Bilateral uterosacral ligament vaginal vault suspension with site specific endopelvic fascia defect repair for treatment of pelvic organ prolapse. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1402-1411.

8. Shull BL, Capen CV, et al. Bilateral attachment of the vaginal cuff to iliococcygeus fascia: an effective method of cuff suspension. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:1669-1677.

9. Maher CF, Murray CJ, et al. Iliococcygeus or sacrospinous fixation for vaginal vault prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:40-44.

10. Morley G, DeLancey JO. Sacrospinous ligament fixation for eversion of the vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:872.-

11. Shull BL, Capen CV, et al. Preoperative and postoperative analysis of site-specific pelvic support defects in 81 women treated with sacrospinous ligament suspension and pelvic reconstruction. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1764-1771.

12. Davila GW, Miller D. Vaginal vault suspension using the Posterior IVS technique. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2004;10:S39.-

13. Addison WA, Bump RC, et al. Sacral colpopexy is the preferred treatment for vaginal vault prolapse in selected patients. J Gynecol Tech. 1996;2:69-74.

14. Kohli N, Walsh PM, et al. Mesh erosion after abdominal sacrocolpopexy. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:999-1004.

15. Visco AG, Weidner AC, et al. Vaginal mesh erosion after abdominal sacral colpopexy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:297-302.

16. Neimark M, Davila GW, Kopka SL. LeForte colpocleisis: a feasible treatment option for pelvic organ prolapse in the elderly woman. J Pelvic Med Surg. 2003;9:1-7.