User login

Does urodynamic testing before surgery for stress incontinence improve outcomes?

URINARY PROBLEMS?

CLICK HERE to access 8 other articles about treating urinary incontinence and urinary tract infections, published in OBG Management in 2012.

Nager and colleagues conducted their trial to determine whether urodynamic testing is necessary before midurethral sling surgery for simple, “garden-variety” stress urinary incontinence (SUI). In their trial, 630 women were randomly assigned to undergo office evaluation with urodynamic tests (n = 315) or office evaluation only (n = 315). Surgical treatment was successful in 76.9% of women in the urodynamic-testing group and in 77.2% of women in the office evaluation-only group (95% confidence interval [CI], –7.5 to 6.9) as long as 1 year after surgery. There were no significant differences between groups in quality of life, patient satisfaction, and other secondary measures of incontinence severity. Investigators concluded that preoperative office evaluation (positive stress test, urethral hypermobility, normal postvoid residual, and negative urinalysis) is not inferior to urodynamic testing.

Should these findings come as a surprise to pelvic surgeons? Retropubic and transobturator slings are associated with very low morbidity and high efficacy. Studies already have demonstrated that, in simple SUI, these slings produce similar outcomes.1 So there is some consensus that urodynamic testing may be unnecessary prior to placement of a midurethral sling for simple SUI. This study lends credence to that notion.

Outcome measures: Focused enough?

The primary outcome measures used in this trial were not designed primarily to assess the severity of SUI. Investigators employed the Urogenital Distress Inventory, which focuses mostly on irritative bladder symptoms and includes only one question about the presence and impact of SUI. They also utilized the Patient Global Impression of Improvement, a global scale related to incontinence in general. Other tests—such as standardized stress tests, pad tests, and bladder diaries—are more specific in the evaluation of SUI severity. Nager and colleagues used these measures themselves in an earlier exploration of the role of urodynamics in predicting sling failure.2

Moreover, in the current study, urodynamic testing did not include a measurement of urethral closure pressure, which has been strongly correlated with success after Burch colposuspension and retropubic and transobturator sling procedures. This test would have added valuable data.

Another shortcoming was the lack of uniformity in the sling procedures that were selected. Most experts believe that retropubic and transobturator slings have unique mechanistic characteristics that do not allow them to be interchangeable. Investigators should have selected a single sling approach.

Is a 77% success rate acceptable to most patients?

SUI represents a continuum of disease severity, and various studies have demonstrated a higher success rate for retropubic slings than for the transobturator approach when sphincteric function is impaired. At our center, we utilize urodynamic parameters to identify women who may achieve a higher continence rate with a retropubic sling.3

Retropubic slings are not appropriate for all patients with SUI. Although the risk of serious complications, such as retropubic hematoma or bowel perforation, is very low, complications sometimes do occur and are related to surgical volumes. For this reason, transobturator slings, which carry minimal associated risks, play a key role in the management of garden-variety SUI.

Indications for multichannel urodynamic testing

|

Don’t throw away your urodynamic equipment just yet. Many patients have complex incontinence symptoms or other indications for urodynamic testing (TABLE). In addition, a clear understanding of urgency symptoms and voiding dysfunction can be very useful during preoperative counseling of patients who are scheduled to undergo sling surgery. Significant urgency is likely to persist postoperatively, and voiding difficulties may worsen after a sling procedure, especially if a retropubic sling is used.

G. WILLY DAVILA, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (Update, December 2012)

1. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

2. Nager CW, Siris L, Litman HJ, et al. Baseline urodynamic predictors of treatment failure 1 year after midurethral sling surgery. J Urol. 2011;186:597-603.

3. Guerette NL, Bena JF, Davila GW. Transobturator slings for stress incontinence: using urodynamic parameters to predict outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19(1):97-102.

URINARY PROBLEMS?

CLICK HERE to access 8 other articles about treating urinary incontinence and urinary tract infections, published in OBG Management in 2012.

Nager and colleagues conducted their trial to determine whether urodynamic testing is necessary before midurethral sling surgery for simple, “garden-variety” stress urinary incontinence (SUI). In their trial, 630 women were randomly assigned to undergo office evaluation with urodynamic tests (n = 315) or office evaluation only (n = 315). Surgical treatment was successful in 76.9% of women in the urodynamic-testing group and in 77.2% of women in the office evaluation-only group (95% confidence interval [CI], –7.5 to 6.9) as long as 1 year after surgery. There were no significant differences between groups in quality of life, patient satisfaction, and other secondary measures of incontinence severity. Investigators concluded that preoperative office evaluation (positive stress test, urethral hypermobility, normal postvoid residual, and negative urinalysis) is not inferior to urodynamic testing.

Should these findings come as a surprise to pelvic surgeons? Retropubic and transobturator slings are associated with very low morbidity and high efficacy. Studies already have demonstrated that, in simple SUI, these slings produce similar outcomes.1 So there is some consensus that urodynamic testing may be unnecessary prior to placement of a midurethral sling for simple SUI. This study lends credence to that notion.

Outcome measures: Focused enough?

The primary outcome measures used in this trial were not designed primarily to assess the severity of SUI. Investigators employed the Urogenital Distress Inventory, which focuses mostly on irritative bladder symptoms and includes only one question about the presence and impact of SUI. They also utilized the Patient Global Impression of Improvement, a global scale related to incontinence in general. Other tests—such as standardized stress tests, pad tests, and bladder diaries—are more specific in the evaluation of SUI severity. Nager and colleagues used these measures themselves in an earlier exploration of the role of urodynamics in predicting sling failure.2

Moreover, in the current study, urodynamic testing did not include a measurement of urethral closure pressure, which has been strongly correlated with success after Burch colposuspension and retropubic and transobturator sling procedures. This test would have added valuable data.

Another shortcoming was the lack of uniformity in the sling procedures that were selected. Most experts believe that retropubic and transobturator slings have unique mechanistic characteristics that do not allow them to be interchangeable. Investigators should have selected a single sling approach.

Is a 77% success rate acceptable to most patients?

SUI represents a continuum of disease severity, and various studies have demonstrated a higher success rate for retropubic slings than for the transobturator approach when sphincteric function is impaired. At our center, we utilize urodynamic parameters to identify women who may achieve a higher continence rate with a retropubic sling.3

Retropubic slings are not appropriate for all patients with SUI. Although the risk of serious complications, such as retropubic hematoma or bowel perforation, is very low, complications sometimes do occur and are related to surgical volumes. For this reason, transobturator slings, which carry minimal associated risks, play a key role in the management of garden-variety SUI.

Indications for multichannel urodynamic testing

|

Don’t throw away your urodynamic equipment just yet. Many patients have complex incontinence symptoms or other indications for urodynamic testing (TABLE). In addition, a clear understanding of urgency symptoms and voiding dysfunction can be very useful during preoperative counseling of patients who are scheduled to undergo sling surgery. Significant urgency is likely to persist postoperatively, and voiding difficulties may worsen after a sling procedure, especially if a retropubic sling is used.

G. WILLY DAVILA, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (Update, December 2012)

URINARY PROBLEMS?

CLICK HERE to access 8 other articles about treating urinary incontinence and urinary tract infections, published in OBG Management in 2012.

Nager and colleagues conducted their trial to determine whether urodynamic testing is necessary before midurethral sling surgery for simple, “garden-variety” stress urinary incontinence (SUI). In their trial, 630 women were randomly assigned to undergo office evaluation with urodynamic tests (n = 315) or office evaluation only (n = 315). Surgical treatment was successful in 76.9% of women in the urodynamic-testing group and in 77.2% of women in the office evaluation-only group (95% confidence interval [CI], –7.5 to 6.9) as long as 1 year after surgery. There were no significant differences between groups in quality of life, patient satisfaction, and other secondary measures of incontinence severity. Investigators concluded that preoperative office evaluation (positive stress test, urethral hypermobility, normal postvoid residual, and negative urinalysis) is not inferior to urodynamic testing.

Should these findings come as a surprise to pelvic surgeons? Retropubic and transobturator slings are associated with very low morbidity and high efficacy. Studies already have demonstrated that, in simple SUI, these slings produce similar outcomes.1 So there is some consensus that urodynamic testing may be unnecessary prior to placement of a midurethral sling for simple SUI. This study lends credence to that notion.

Outcome measures: Focused enough?

The primary outcome measures used in this trial were not designed primarily to assess the severity of SUI. Investigators employed the Urogenital Distress Inventory, which focuses mostly on irritative bladder symptoms and includes only one question about the presence and impact of SUI. They also utilized the Patient Global Impression of Improvement, a global scale related to incontinence in general. Other tests—such as standardized stress tests, pad tests, and bladder diaries—are more specific in the evaluation of SUI severity. Nager and colleagues used these measures themselves in an earlier exploration of the role of urodynamics in predicting sling failure.2

Moreover, in the current study, urodynamic testing did not include a measurement of urethral closure pressure, which has been strongly correlated with success after Burch colposuspension and retropubic and transobturator sling procedures. This test would have added valuable data.

Another shortcoming was the lack of uniformity in the sling procedures that were selected. Most experts believe that retropubic and transobturator slings have unique mechanistic characteristics that do not allow them to be interchangeable. Investigators should have selected a single sling approach.

Is a 77% success rate acceptable to most patients?

SUI represents a continuum of disease severity, and various studies have demonstrated a higher success rate for retropubic slings than for the transobturator approach when sphincteric function is impaired. At our center, we utilize urodynamic parameters to identify women who may achieve a higher continence rate with a retropubic sling.3

Retropubic slings are not appropriate for all patients with SUI. Although the risk of serious complications, such as retropubic hematoma or bowel perforation, is very low, complications sometimes do occur and are related to surgical volumes. For this reason, transobturator slings, which carry minimal associated risks, play a key role in the management of garden-variety SUI.

Indications for multichannel urodynamic testing

|

Don’t throw away your urodynamic equipment just yet. Many patients have complex incontinence symptoms or other indications for urodynamic testing (TABLE). In addition, a clear understanding of urgency symptoms and voiding dysfunction can be very useful during preoperative counseling of patients who are scheduled to undergo sling surgery. Significant urgency is likely to persist postoperatively, and voiding difficulties may worsen after a sling procedure, especially if a retropubic sling is used.

G. WILLY DAVILA, MD

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

Urinary incontinence

Karen L. Noblett, MD, MAS, and Stephanie A. Jacobs, MD (Update, December 2012)

1. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

2. Nager CW, Siris L, Litman HJ, et al. Baseline urodynamic predictors of treatment failure 1 year after midurethral sling surgery. J Urol. 2011;186:597-603.

3. Guerette NL, Bena JF, Davila GW. Transobturator slings for stress incontinence: using urodynamic parameters to predict outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19(1):97-102.

1. Barber MD, Kleeman S, Karram MM, et al. Transobturator tape compared with tension-free vaginal tape for the treatment of stress urinary incontinence. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(3):611-621.

2. Nager CW, Siris L, Litman HJ, et al. Baseline urodynamic predictors of treatment failure 1 year after midurethral sling surgery. J Urol. 2011;186:597-603.

3. Guerette NL, Bena JF, Davila GW. Transobturator slings for stress incontinence: using urodynamic parameters to predict outcomes. Int Urogynecol J. 2008;19(1):97-102.

Take this simplified approach to correcting exposure of vaginal mesh

CASE: Pain during intercourse, well after mesh implantation

Your patient, 61 years old, para 3, has come to your office by referral with a complaint of dyspareunia. The history includes placement of a synthetic vaginal mesh kit 14 months earlier for prolapse.

The medical record shows that the referring physician performed a “mesh excision” 1 year after the original procedure.

The woman reports that she is “very frustrated” that she is still dealing with this problem so long after the original procedure.

On examination, you note a 2.5-cm diameter area of exposed mesh in the anterior vagina, with healthy surrounding tissue and without inflammation or purulence (FIGURE 1). You are unable to reproduce her complaint of pain on vaginal examination.

What options can you offer to this woman? And will those options meet her therapeutic expectations?

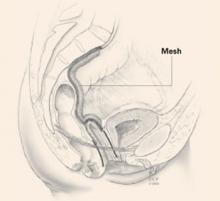

FIGURE 1 Examination of your referred patient: Mesh is noticeably exposedThe recent increase in the use of mesh grafts to reconstruct pelvic anatomy has been directed mainly at improving surgical outcomes. Yet, at the same time, gynecologic surgeons find themselves facing a rise in associated complications of such surgery that they did not see previously.

Among the most troublesome and concerning of those complications are 1) exposure of mesh through the vaginal epithelium and 2) contraction or hardening of mesh (or both) that can result in dyspareunia and chronic pelvic pain. Other, rare complications include infection and fistula.

Our goal in this article is to address the management of graft-healing abnormalities in which a segment of the mesh is palpable or visible, or both, within the vaginal canal. Our focus is on simple abnormalities that can be managed by most generalist gynecologists; to be clear, more complex abnormalities, and those that provoke more serious or lasting symptoms, belong under the care of a specialist.

A recent shift in terminology is significant

Early on, this complication was called “erosion” as understanding of the mechanism of its development grew, however, terminology applied to the problem has changed.

In fact, mesh itself very rarely erodes into the vagina or an underlying viscus. Instead, the complication occurs most commonly as a result of disruption of a suture line—most likely the result of a hematoma or localized inflammation that develops postoperatively.

“Exposure” (our preference here) and “extrusion” are now the recommended terms, based on a consensus terminology document published this year jointly by the International Urogynecological Association and the International Continence Society.1

Exposure of implanted mesh is considered a “simple” healing abnormality because it typically

- occurs along the suture line and early in the course of healing

- is not associated with infection of the graft.2

The typical physical appearance is one of visible mesh along an open suture line without granulation tissue or purulence—again, see FIGURE 1. The mesh is firmly adherent to the vaginal epithelial edges and underlying fascia.

The reported incidence of mesh exposures—in regard to currently used meshes, which are all Type-1, monofilament, macroporous polypropylene grafts—is approximately 10% but as high as 15% to 20% in some reported series.3,4 The higher rates of exposure are usually seen in series in which some patients have had a synthetic graft implanted as an overlay to fascial midline plication. When the graft is implanted in the subfascial layer of the vaginal wall (i.e., without midline plication), however, the reported rate of exposure falls—to 5% to 10%.5-7

Recommendations for management

Initially, recommendations for “erosion” management were based on concerns about underlying mesh infection or rejection, and included a need to remove the entire graft. That recommendation still applies to multifilament, microporous grafts that present with inflammatory infiltrates, granulation tissue, and purulence. Although these kinds of grafts (known as “Type-2/3 grafts”—e.g., GoreTex, IVS) have not been marketed for pelvic reconstruction over the past 3 to 5 years, their behavior post-implantation is less predictable—and patients who have delayed healing abnormalities are, therefore, still being seen. It’s fortunate that development of an overlying biofilm prevents tissue incorporation into these types of graft, allowing them to be removed easily.

Exposures related to Type-1 mesh—currently used in pelvic reconstruction—that occur without surrounding infection do not require extensive removal. Rather, they can be managed conservatively or, when necessary, with outpatient surgery. In patients who are not sexually active, exposures are usually asymptomatic; they might only be observed by the physician on vaginal examination and are amenable to simple monitoring. In sexually active patients, exposure of Type-1 mesh usually results in dyspareunia or a complaint that the partner “can feel the mesh.” Depending on the size and the nature of symptoms and the extent of the defect, these commonly seen exposures can be managed by following a simple algorithm.

Palpable or visible mesh fibrils can be trimmed in the office; they might even respond to local estrogen alone. Consider these options if the patient displays vaginal atrophy.

Typically, vaginal estrogen is prescribed as 1 g nightly for 2 weeks and then 1 g two or three nights a week. Re-examine the patient in 3 months; if symptoms of mesh exposure persist, it’s unlikely that continued conservative therapy will be successful, and outpatient surgery is recommended.

When exposure is asymptomatic, you can simply monitor the condition for 3 to 6 months; if complaints or findings arise, consider intervention.

Small (<0.5 cm in diameter) exposures can also be managed in the office, including excision of exposed mesh and local estrogen. If the exposure is easily reachable, we recommend grasping the exposed area with pick-ups or a hemostat and with gentle traction, using Metzenbaum scissors to trim exposed mesh as close to the vaginal epithelium as possible. Local topical or injected anesthesia may be needed. Bleeding should be minimal because no dissection is necessary. Silver nitrate can be applied for any minor bleeding. Larger (0.5–4.0 cm) exposures are unlikely to heal on their own. They require outpatient excision in the operating room.

Preoperative tissue preparation with local estrogen is key to successful repair of these exposures. Vaginal estrogen increases blood flow to the epithelium; as tissue becomes well-estrogenized, risk of recurrence diminishes.

The technique we employ includes:

- circumferential infiltration of vaginal epithelium surrounding the exposed mesh with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine

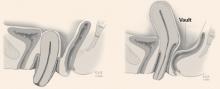

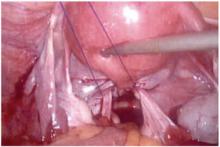

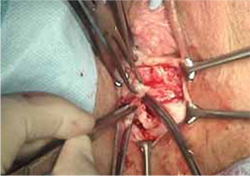

- sharp circumscription of the area of exposure, using a scalpel, with a 0.5-cm margin of vaginal epithelium (FIGURE 2)

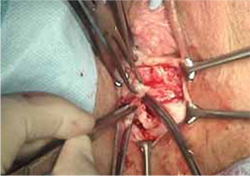

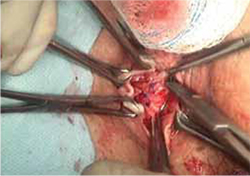

- wide dissection, with undermining and mobilization of surrounding healthy vaginal epithelium around the exposure (FIGURE 3)

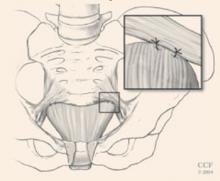

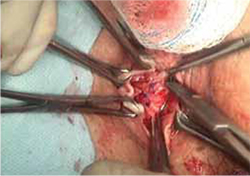

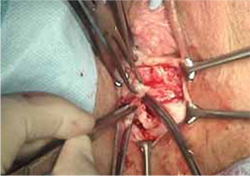

- excision of the exposed mesh and attached vaginal mucosa, with careful dissection of the mesh off underlying tissues with Metzenbaum scissors—being careful to avoid injury to underlying bladder or rectum (FIGURE 4)

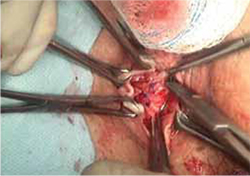

- reapproximation of mesh edges, using 2-0 polypropylene suture to close the resulting defect so that prolapse does not recur (FIGURE 5)

- closing of the previously mobilized vaginal epithelium with 2-0 Vicryl suture, without tension, to cover the reapproximated mesh edges—after irrigation and assurance of adequate hemostasis (FIGURE 6).

FIGURE 2 Incision of vaginal epithelium

Allow for a 0.5-cm margin.

FIGURE 3 Undermining and mobilization of epithelium

Perform wide dissection.

FIGURE 4 Dissection of mesh from underlying tissue

Keep clear of underlying bladder and rectum!

FIGURE 5 Reapproximation of edges to re-establish support

Our choice of suture is 2-0 polypropylene.

FIGURE 6 Irrigation of vaginal epithelium, followed by closure

Before you close, ensure that hemostasis is adequate.The choice of closure—vertical or horizontal—depends on the nature of the original defect.

You can watch a video of this technique that we’ve provided.

Several cautions should be taken with this technique, including:

- avoiding narrowing the vaginal canal

- minimizing trauma to healthy vaginal epithelium that will be used for closure

- maintaining hemostasis to avoid formation of hematomas.

Largest (>4 cm) exposures are likely the result of devascularized sloughing of vaginal epithelium. They are, fortunately, uncommon.

It’s unlikely that, after excision of exposed mesh, the vaginal epithelial edges can be approximated without significantly narrowing or shortening the vaginal canal. Proposed techniques for managing these large exposures include covering the defect with a biologic graft, such as small intestinal submucosa, to allow epithelium to re-grow. Regrettably, prolapse is likely to recur in the unprotected area that results.

Contraction and localized pain

Hardening and contraction typically occur along the fixation arms of the mesh. These complications might result from mesh shrinkage or from mesh being placed too tight, so to speak, at implantation. Rarely does the entire implanted mesh contract.

Severe mesh contraction can result in localized pain and de novo dyspareunia. Symptoms usually resolve after identification of the painful area and removal of the involved mesh segment.8

Diagnostic maneuver. In-office trigger-point injection of bupivacaine with triamcinolone is useful to accurately identify the location of pain that is causing dyspareunia. After injection, the patient is asked to return home and resume sexual intercourse; if dyspareunia diminishes significantly, surgical removal of the involved mesh segment is likely to ameliorate symptoms.

If dyspareunia persists after injection, however, the problem either 1) originates in a different location along the graft or 2) may not be related to the mesh—that is, it may be introital pain or preexisting vaginal pain.

The findings of trigger-point injection and a subsequent trial of sexual intercourse are useful for counseling the patient and developing realistic expectations that surgery will be successful.

Management note: Mesh contraction should be managed by a surgeon who is experienced in extensive deep pelvic dissection, which is necessary to remove the mesh arms.

Chronic pain

Diffuse vaginal pain after mesh implantation is unusual; typically, the patient’s report of pain has been preceded by recognition of another, underlying pelvic pain syndrome. Management of such pain is controversial, and many patients will not be satisfied until the entire graft is removed. Whether such drastic intervention actually resolves the pain is unclear; again, work with the patient to create realistic expectations before surgery—including the risk that prolapse will recur and that reoperation will be necessary.

Management note: An existing pelvic pain syndrome should be considered a relative contraindication to implantation of mesh.

Infection of the graft

Rarely, infection has been reported after implantation of Type-1 mesh—the result of either multi-microbial colonization or isolated infection by Bacteriodes melaninogenicus, Actinomyces spp, or Staphylococcus aureus. Untreated preoperative bacterial vaginitis is likely the underlying cause, and should be considered a contraindication to mesh implantation.

Typically, these patients complain of vaginal discharge and bleeding early postoperatively. Vaginal exposure of the mesh results from local inflammation and necrosis of tissue.

Management note: In these cases, it is necessary to 1) prescribe antimicrobial therapy that covers gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria and 2) undertake surgical removal of the exposed mesh, as we outlined above.9

Visceral erosion or fistula

Many experts believe that what is recorded as “erosion” of synthetic mesh into bladder or rectum is, in fact, a result of unrecognized visceral perforation at original implantation. This is a rare complication of mesh implantation.

Patients who experience mesh erosion into the bladder may have lower urinary-tract symptoms (LUTS) of urgency, frequency, dysuria, and hematuria. Any patient who reports de novo LUTS in the early postoperative period after a vaginal mesh procedure should receive office cystourethroscopy to ensure that no foreign body is present in the bladder or urethra.

Management note: Operative cystourethroscopy, with removal of exposed mesh, is the management of choice when mesh is found in the bladder or urethra.

Patients who have constant urinary or fecal incontinence immediately after surgery should be evaluated for vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistula.

The presence of any of these complications necessitates removal of the involved mesh in its entirety, with concomitant repair of fistula. Typically, the procedures are performed by a specialist.

Our experience with correcting simple mesh exposures

During the past year at our tertiary referral center, 26 patients have undergone mesh revision because of exposure, using the technique we described above (FIGURE 2-6). The problem resolved in all; none had persistent dyspareunia. Many of these patients had already undergone attempts at correction of the exposure elsewhere—mostly, in the office, using techniques appropriate for that setting. Prolapse has not recurred in the 10 patients who required reapproximation of mesh edges because of a defect >2.5 cm.

CASE RESOLVED: Treatment, improvement

Under your care, the patient undergoes simplified outpatient excision of the exposed area of mesh. Mesh edges are reapproximated to support the resulting 3-cm defect.

At a 12-week postop visit, you note complete resolution of the exposure and normal vaginal caliber. The patient continues to apply estrogen cream and reports sustained improvement in sexual function.

- Preoperatively, prepare the vaginal epithelium with local estrogen cream (recommended dosage: 1 g, two nights every week for a trial of at least 6 weeks)

- Use hydrodissection to facilitate placement of the graft deep to the vaginal epithelial fibromuscular fascial layer

- Do not place a synthetic mesh as an overlay to a midline fascial plication

- Be fastidious about hemostasis

- Close the vaginal epithelium without tension

- Leave vaginal packing in place for 24 hours

- Consider using biologic grafts when appropriate (as an overlay to midline plication when used on the anterior vaginal wall).

For simple presentations, success is within reach

Simple mesh exposure can (as in the case we described) be managed by most gynecologists, utilizing the simple stepwise approach that we outlined above (for additional tips based on our experience, see “Pearls for avoiding mesh exposures”). In the case of more significant symptoms, de novo dyspareunia, visceral erosion, or fistula, however, referral to a specialist is warranted.

Transvaginal mesh surgery reduces pelvic organ prolapse

But dyspareunia may develop in premenopausal women

Transvaginal mesh (TVM) surgery is effective in treating pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in both pre- and postmenopausal women but dyspareunia may worsen in premenopausal women, according to a study published online May 23 in the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

Cheng-Yu Long, MD, PhD, from Kaohsiung Medical University in Taiwan, and colleagues compared the changes in sexual function of premenopausal and postmenopausal women after TVM surgery. A total of 68 sexually active women, categorized as premenopausal (36) and postmenopausal (32), with symptomatic POP stages II to IV were referred for TVM surgery. Preoperative and postoperative assessments included pelvic examination using the POP quantification (POP-Q) system, and completing the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7).

The investigators found significant improvement in the POP-Q analysis at points Aa, Ba, C, Ap, and Bp in both groups but not in total vaginal length. The UDI-6 and IIQ-7 scores decreased significantly after TVM surgery. The dyspareunia domain score decreased significantly after surgery only in the premenopausal group. Reports of diminished scores of the dyspareunia domain and total scores were more common among women in the premenopausal group, but there were no significant differences in FSFI domains or total scores between the groups.

Copyright © 2011 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of prosthesis (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2011;22(1):3-15.

2. Davila GW, Drutz H, Deprest J. Clinical implications of the biology of grafts: conclusions of the 2005 IUGA Grafts Roundtable. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17(suppl 1):S51-55.

3. Iglesia CB, Sokol AI, Sokol ER, et al. Vaginal mesh for prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 1):293-303.

4. Hiltunen R, Nieminen K, Takala T, et al. Low-weight polypropylene mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 2):455-462.

5. Fatton B, Amblard J, Debodiance P, Cosson M, Jacquetin B. Transvaginal repair of genital prolapse: preliminary results of a new tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift technique)—a case series multicentric study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(7):743-752.

6. Diwadkar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, Maher C, Jelovsek JE. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2):367-373.

7. Nguyen JN, Burchette RJ. Outcome after anterior vaginal prolapse repair: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):891-898.

8. Feiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition clinical presentation, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 2):325-330.

9. Athanasiou S, Matthaiou DK, Falagas ME. Vaginal mesh infection due to Bacteroides melaninogenicus: a case report of another emerging foreign body related infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38(11-12):1108-1110.

CASE: Pain during intercourse, well after mesh implantation

Your patient, 61 years old, para 3, has come to your office by referral with a complaint of dyspareunia. The history includes placement of a synthetic vaginal mesh kit 14 months earlier for prolapse.

The medical record shows that the referring physician performed a “mesh excision” 1 year after the original procedure.

The woman reports that she is “very frustrated” that she is still dealing with this problem so long after the original procedure.

On examination, you note a 2.5-cm diameter area of exposed mesh in the anterior vagina, with healthy surrounding tissue and without inflammation or purulence (FIGURE 1). You are unable to reproduce her complaint of pain on vaginal examination.

What options can you offer to this woman? And will those options meet her therapeutic expectations?

FIGURE 1 Examination of your referred patient: Mesh is noticeably exposedThe recent increase in the use of mesh grafts to reconstruct pelvic anatomy has been directed mainly at improving surgical outcomes. Yet, at the same time, gynecologic surgeons find themselves facing a rise in associated complications of such surgery that they did not see previously.

Among the most troublesome and concerning of those complications are 1) exposure of mesh through the vaginal epithelium and 2) contraction or hardening of mesh (or both) that can result in dyspareunia and chronic pelvic pain. Other, rare complications include infection and fistula.

Our goal in this article is to address the management of graft-healing abnormalities in which a segment of the mesh is palpable or visible, or both, within the vaginal canal. Our focus is on simple abnormalities that can be managed by most generalist gynecologists; to be clear, more complex abnormalities, and those that provoke more serious or lasting symptoms, belong under the care of a specialist.

A recent shift in terminology is significant

Early on, this complication was called “erosion” as understanding of the mechanism of its development grew, however, terminology applied to the problem has changed.

In fact, mesh itself very rarely erodes into the vagina or an underlying viscus. Instead, the complication occurs most commonly as a result of disruption of a suture line—most likely the result of a hematoma or localized inflammation that develops postoperatively.

“Exposure” (our preference here) and “extrusion” are now the recommended terms, based on a consensus terminology document published this year jointly by the International Urogynecological Association and the International Continence Society.1

Exposure of implanted mesh is considered a “simple” healing abnormality because it typically

- occurs along the suture line and early in the course of healing

- is not associated with infection of the graft.2

The typical physical appearance is one of visible mesh along an open suture line without granulation tissue or purulence—again, see FIGURE 1. The mesh is firmly adherent to the vaginal epithelial edges and underlying fascia.

The reported incidence of mesh exposures—in regard to currently used meshes, which are all Type-1, monofilament, macroporous polypropylene grafts—is approximately 10% but as high as 15% to 20% in some reported series.3,4 The higher rates of exposure are usually seen in series in which some patients have had a synthetic graft implanted as an overlay to fascial midline plication. When the graft is implanted in the subfascial layer of the vaginal wall (i.e., without midline plication), however, the reported rate of exposure falls—to 5% to 10%.5-7

Recommendations for management

Initially, recommendations for “erosion” management were based on concerns about underlying mesh infection or rejection, and included a need to remove the entire graft. That recommendation still applies to multifilament, microporous grafts that present with inflammatory infiltrates, granulation tissue, and purulence. Although these kinds of grafts (known as “Type-2/3 grafts”—e.g., GoreTex, IVS) have not been marketed for pelvic reconstruction over the past 3 to 5 years, their behavior post-implantation is less predictable—and patients who have delayed healing abnormalities are, therefore, still being seen. It’s fortunate that development of an overlying biofilm prevents tissue incorporation into these types of graft, allowing them to be removed easily.

Exposures related to Type-1 mesh—currently used in pelvic reconstruction—that occur without surrounding infection do not require extensive removal. Rather, they can be managed conservatively or, when necessary, with outpatient surgery. In patients who are not sexually active, exposures are usually asymptomatic; they might only be observed by the physician on vaginal examination and are amenable to simple monitoring. In sexually active patients, exposure of Type-1 mesh usually results in dyspareunia or a complaint that the partner “can feel the mesh.” Depending on the size and the nature of symptoms and the extent of the defect, these commonly seen exposures can be managed by following a simple algorithm.

Palpable or visible mesh fibrils can be trimmed in the office; they might even respond to local estrogen alone. Consider these options if the patient displays vaginal atrophy.

Typically, vaginal estrogen is prescribed as 1 g nightly for 2 weeks and then 1 g two or three nights a week. Re-examine the patient in 3 months; if symptoms of mesh exposure persist, it’s unlikely that continued conservative therapy will be successful, and outpatient surgery is recommended.

When exposure is asymptomatic, you can simply monitor the condition for 3 to 6 months; if complaints or findings arise, consider intervention.

Small (<0.5 cm in diameter) exposures can also be managed in the office, including excision of exposed mesh and local estrogen. If the exposure is easily reachable, we recommend grasping the exposed area with pick-ups or a hemostat and with gentle traction, using Metzenbaum scissors to trim exposed mesh as close to the vaginal epithelium as possible. Local topical or injected anesthesia may be needed. Bleeding should be minimal because no dissection is necessary. Silver nitrate can be applied for any minor bleeding. Larger (0.5–4.0 cm) exposures are unlikely to heal on their own. They require outpatient excision in the operating room.

Preoperative tissue preparation with local estrogen is key to successful repair of these exposures. Vaginal estrogen increases blood flow to the epithelium; as tissue becomes well-estrogenized, risk of recurrence diminishes.

The technique we employ includes:

- circumferential infiltration of vaginal epithelium surrounding the exposed mesh with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine

- sharp circumscription of the area of exposure, using a scalpel, with a 0.5-cm margin of vaginal epithelium (FIGURE 2)

- wide dissection, with undermining and mobilization of surrounding healthy vaginal epithelium around the exposure (FIGURE 3)

- excision of the exposed mesh and attached vaginal mucosa, with careful dissection of the mesh off underlying tissues with Metzenbaum scissors—being careful to avoid injury to underlying bladder or rectum (FIGURE 4)

- reapproximation of mesh edges, using 2-0 polypropylene suture to close the resulting defect so that prolapse does not recur (FIGURE 5)

- closing of the previously mobilized vaginal epithelium with 2-0 Vicryl suture, without tension, to cover the reapproximated mesh edges—after irrigation and assurance of adequate hemostasis (FIGURE 6).

FIGURE 2 Incision of vaginal epithelium

Allow for a 0.5-cm margin.

FIGURE 3 Undermining and mobilization of epithelium

Perform wide dissection.

FIGURE 4 Dissection of mesh from underlying tissue

Keep clear of underlying bladder and rectum!

FIGURE 5 Reapproximation of edges to re-establish support

Our choice of suture is 2-0 polypropylene.

FIGURE 6 Irrigation of vaginal epithelium, followed by closure

Before you close, ensure that hemostasis is adequate.The choice of closure—vertical or horizontal—depends on the nature of the original defect.

You can watch a video of this technique that we’ve provided.

Several cautions should be taken with this technique, including:

- avoiding narrowing the vaginal canal

- minimizing trauma to healthy vaginal epithelium that will be used for closure

- maintaining hemostasis to avoid formation of hematomas.

Largest (>4 cm) exposures are likely the result of devascularized sloughing of vaginal epithelium. They are, fortunately, uncommon.

It’s unlikely that, after excision of exposed mesh, the vaginal epithelial edges can be approximated without significantly narrowing or shortening the vaginal canal. Proposed techniques for managing these large exposures include covering the defect with a biologic graft, such as small intestinal submucosa, to allow epithelium to re-grow. Regrettably, prolapse is likely to recur in the unprotected area that results.

Contraction and localized pain

Hardening and contraction typically occur along the fixation arms of the mesh. These complications might result from mesh shrinkage or from mesh being placed too tight, so to speak, at implantation. Rarely does the entire implanted mesh contract.

Severe mesh contraction can result in localized pain and de novo dyspareunia. Symptoms usually resolve after identification of the painful area and removal of the involved mesh segment.8

Diagnostic maneuver. In-office trigger-point injection of bupivacaine with triamcinolone is useful to accurately identify the location of pain that is causing dyspareunia. After injection, the patient is asked to return home and resume sexual intercourse; if dyspareunia diminishes significantly, surgical removal of the involved mesh segment is likely to ameliorate symptoms.

If dyspareunia persists after injection, however, the problem either 1) originates in a different location along the graft or 2) may not be related to the mesh—that is, it may be introital pain or preexisting vaginal pain.

The findings of trigger-point injection and a subsequent trial of sexual intercourse are useful for counseling the patient and developing realistic expectations that surgery will be successful.

Management note: Mesh contraction should be managed by a surgeon who is experienced in extensive deep pelvic dissection, which is necessary to remove the mesh arms.

Chronic pain

Diffuse vaginal pain after mesh implantation is unusual; typically, the patient’s report of pain has been preceded by recognition of another, underlying pelvic pain syndrome. Management of such pain is controversial, and many patients will not be satisfied until the entire graft is removed. Whether such drastic intervention actually resolves the pain is unclear; again, work with the patient to create realistic expectations before surgery—including the risk that prolapse will recur and that reoperation will be necessary.

Management note: An existing pelvic pain syndrome should be considered a relative contraindication to implantation of mesh.

Infection of the graft

Rarely, infection has been reported after implantation of Type-1 mesh—the result of either multi-microbial colonization or isolated infection by Bacteriodes melaninogenicus, Actinomyces spp, or Staphylococcus aureus. Untreated preoperative bacterial vaginitis is likely the underlying cause, and should be considered a contraindication to mesh implantation.

Typically, these patients complain of vaginal discharge and bleeding early postoperatively. Vaginal exposure of the mesh results from local inflammation and necrosis of tissue.

Management note: In these cases, it is necessary to 1) prescribe antimicrobial therapy that covers gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria and 2) undertake surgical removal of the exposed mesh, as we outlined above.9

Visceral erosion or fistula

Many experts believe that what is recorded as “erosion” of synthetic mesh into bladder or rectum is, in fact, a result of unrecognized visceral perforation at original implantation. This is a rare complication of mesh implantation.

Patients who experience mesh erosion into the bladder may have lower urinary-tract symptoms (LUTS) of urgency, frequency, dysuria, and hematuria. Any patient who reports de novo LUTS in the early postoperative period after a vaginal mesh procedure should receive office cystourethroscopy to ensure that no foreign body is present in the bladder or urethra.

Management note: Operative cystourethroscopy, with removal of exposed mesh, is the management of choice when mesh is found in the bladder or urethra.

Patients who have constant urinary or fecal incontinence immediately after surgery should be evaluated for vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistula.

The presence of any of these complications necessitates removal of the involved mesh in its entirety, with concomitant repair of fistula. Typically, the procedures are performed by a specialist.

Our experience with correcting simple mesh exposures

During the past year at our tertiary referral center, 26 patients have undergone mesh revision because of exposure, using the technique we described above (FIGURE 2-6). The problem resolved in all; none had persistent dyspareunia. Many of these patients had already undergone attempts at correction of the exposure elsewhere—mostly, in the office, using techniques appropriate for that setting. Prolapse has not recurred in the 10 patients who required reapproximation of mesh edges because of a defect >2.5 cm.

CASE RESOLVED: Treatment, improvement

Under your care, the patient undergoes simplified outpatient excision of the exposed area of mesh. Mesh edges are reapproximated to support the resulting 3-cm defect.

At a 12-week postop visit, you note complete resolution of the exposure and normal vaginal caliber. The patient continues to apply estrogen cream and reports sustained improvement in sexual function.

- Preoperatively, prepare the vaginal epithelium with local estrogen cream (recommended dosage: 1 g, two nights every week for a trial of at least 6 weeks)

- Use hydrodissection to facilitate placement of the graft deep to the vaginal epithelial fibromuscular fascial layer

- Do not place a synthetic mesh as an overlay to a midline fascial plication

- Be fastidious about hemostasis

- Close the vaginal epithelium without tension

- Leave vaginal packing in place for 24 hours

- Consider using biologic grafts when appropriate (as an overlay to midline plication when used on the anterior vaginal wall).

For simple presentations, success is within reach

Simple mesh exposure can (as in the case we described) be managed by most gynecologists, utilizing the simple stepwise approach that we outlined above (for additional tips based on our experience, see “Pearls for avoiding mesh exposures”). In the case of more significant symptoms, de novo dyspareunia, visceral erosion, or fistula, however, referral to a specialist is warranted.

Transvaginal mesh surgery reduces pelvic organ prolapse

But dyspareunia may develop in premenopausal women

Transvaginal mesh (TVM) surgery is effective in treating pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in both pre- and postmenopausal women but dyspareunia may worsen in premenopausal women, according to a study published online May 23 in the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

Cheng-Yu Long, MD, PhD, from Kaohsiung Medical University in Taiwan, and colleagues compared the changes in sexual function of premenopausal and postmenopausal women after TVM surgery. A total of 68 sexually active women, categorized as premenopausal (36) and postmenopausal (32), with symptomatic POP stages II to IV were referred for TVM surgery. Preoperative and postoperative assessments included pelvic examination using the POP quantification (POP-Q) system, and completing the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7).

The investigators found significant improvement in the POP-Q analysis at points Aa, Ba, C, Ap, and Bp in both groups but not in total vaginal length. The UDI-6 and IIQ-7 scores decreased significantly after TVM surgery. The dyspareunia domain score decreased significantly after surgery only in the premenopausal group. Reports of diminished scores of the dyspareunia domain and total scores were more common among women in the premenopausal group, but there were no significant differences in FSFI domains or total scores between the groups.

Copyright © 2011 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CASE: Pain during intercourse, well after mesh implantation

Your patient, 61 years old, para 3, has come to your office by referral with a complaint of dyspareunia. The history includes placement of a synthetic vaginal mesh kit 14 months earlier for prolapse.

The medical record shows that the referring physician performed a “mesh excision” 1 year after the original procedure.

The woman reports that she is “very frustrated” that she is still dealing with this problem so long after the original procedure.

On examination, you note a 2.5-cm diameter area of exposed mesh in the anterior vagina, with healthy surrounding tissue and without inflammation or purulence (FIGURE 1). You are unable to reproduce her complaint of pain on vaginal examination.

What options can you offer to this woman? And will those options meet her therapeutic expectations?

FIGURE 1 Examination of your referred patient: Mesh is noticeably exposedThe recent increase in the use of mesh grafts to reconstruct pelvic anatomy has been directed mainly at improving surgical outcomes. Yet, at the same time, gynecologic surgeons find themselves facing a rise in associated complications of such surgery that they did not see previously.

Among the most troublesome and concerning of those complications are 1) exposure of mesh through the vaginal epithelium and 2) contraction or hardening of mesh (or both) that can result in dyspareunia and chronic pelvic pain. Other, rare complications include infection and fistula.

Our goal in this article is to address the management of graft-healing abnormalities in which a segment of the mesh is palpable or visible, or both, within the vaginal canal. Our focus is on simple abnormalities that can be managed by most generalist gynecologists; to be clear, more complex abnormalities, and those that provoke more serious or lasting symptoms, belong under the care of a specialist.

A recent shift in terminology is significant

Early on, this complication was called “erosion” as understanding of the mechanism of its development grew, however, terminology applied to the problem has changed.

In fact, mesh itself very rarely erodes into the vagina or an underlying viscus. Instead, the complication occurs most commonly as a result of disruption of a suture line—most likely the result of a hematoma or localized inflammation that develops postoperatively.

“Exposure” (our preference here) and “extrusion” are now the recommended terms, based on a consensus terminology document published this year jointly by the International Urogynecological Association and the International Continence Society.1

Exposure of implanted mesh is considered a “simple” healing abnormality because it typically

- occurs along the suture line and early in the course of healing

- is not associated with infection of the graft.2

The typical physical appearance is one of visible mesh along an open suture line without granulation tissue or purulence—again, see FIGURE 1. The mesh is firmly adherent to the vaginal epithelial edges and underlying fascia.

The reported incidence of mesh exposures—in regard to currently used meshes, which are all Type-1, monofilament, macroporous polypropylene grafts—is approximately 10% but as high as 15% to 20% in some reported series.3,4 The higher rates of exposure are usually seen in series in which some patients have had a synthetic graft implanted as an overlay to fascial midline plication. When the graft is implanted in the subfascial layer of the vaginal wall (i.e., without midline plication), however, the reported rate of exposure falls—to 5% to 10%.5-7

Recommendations for management

Initially, recommendations for “erosion” management were based on concerns about underlying mesh infection or rejection, and included a need to remove the entire graft. That recommendation still applies to multifilament, microporous grafts that present with inflammatory infiltrates, granulation tissue, and purulence. Although these kinds of grafts (known as “Type-2/3 grafts”—e.g., GoreTex, IVS) have not been marketed for pelvic reconstruction over the past 3 to 5 years, their behavior post-implantation is less predictable—and patients who have delayed healing abnormalities are, therefore, still being seen. It’s fortunate that development of an overlying biofilm prevents tissue incorporation into these types of graft, allowing them to be removed easily.

Exposures related to Type-1 mesh—currently used in pelvic reconstruction—that occur without surrounding infection do not require extensive removal. Rather, they can be managed conservatively or, when necessary, with outpatient surgery. In patients who are not sexually active, exposures are usually asymptomatic; they might only be observed by the physician on vaginal examination and are amenable to simple monitoring. In sexually active patients, exposure of Type-1 mesh usually results in dyspareunia or a complaint that the partner “can feel the mesh.” Depending on the size and the nature of symptoms and the extent of the defect, these commonly seen exposures can be managed by following a simple algorithm.

Palpable or visible mesh fibrils can be trimmed in the office; they might even respond to local estrogen alone. Consider these options if the patient displays vaginal atrophy.

Typically, vaginal estrogen is prescribed as 1 g nightly for 2 weeks and then 1 g two or three nights a week. Re-examine the patient in 3 months; if symptoms of mesh exposure persist, it’s unlikely that continued conservative therapy will be successful, and outpatient surgery is recommended.

When exposure is asymptomatic, you can simply monitor the condition for 3 to 6 months; if complaints or findings arise, consider intervention.

Small (<0.5 cm in diameter) exposures can also be managed in the office, including excision of exposed mesh and local estrogen. If the exposure is easily reachable, we recommend grasping the exposed area with pick-ups or a hemostat and with gentle traction, using Metzenbaum scissors to trim exposed mesh as close to the vaginal epithelium as possible. Local topical or injected anesthesia may be needed. Bleeding should be minimal because no dissection is necessary. Silver nitrate can be applied for any minor bleeding. Larger (0.5–4.0 cm) exposures are unlikely to heal on their own. They require outpatient excision in the operating room.

Preoperative tissue preparation with local estrogen is key to successful repair of these exposures. Vaginal estrogen increases blood flow to the epithelium; as tissue becomes well-estrogenized, risk of recurrence diminishes.

The technique we employ includes:

- circumferential infiltration of vaginal epithelium surrounding the exposed mesh with 1% lidocaine with epinephrine

- sharp circumscription of the area of exposure, using a scalpel, with a 0.5-cm margin of vaginal epithelium (FIGURE 2)

- wide dissection, with undermining and mobilization of surrounding healthy vaginal epithelium around the exposure (FIGURE 3)

- excision of the exposed mesh and attached vaginal mucosa, with careful dissection of the mesh off underlying tissues with Metzenbaum scissors—being careful to avoid injury to underlying bladder or rectum (FIGURE 4)

- reapproximation of mesh edges, using 2-0 polypropylene suture to close the resulting defect so that prolapse does not recur (FIGURE 5)

- closing of the previously mobilized vaginal epithelium with 2-0 Vicryl suture, without tension, to cover the reapproximated mesh edges—after irrigation and assurance of adequate hemostasis (FIGURE 6).

FIGURE 2 Incision of vaginal epithelium

Allow for a 0.5-cm margin.

FIGURE 3 Undermining and mobilization of epithelium

Perform wide dissection.

FIGURE 4 Dissection of mesh from underlying tissue

Keep clear of underlying bladder and rectum!

FIGURE 5 Reapproximation of edges to re-establish support

Our choice of suture is 2-0 polypropylene.

FIGURE 6 Irrigation of vaginal epithelium, followed by closure

Before you close, ensure that hemostasis is adequate.The choice of closure—vertical or horizontal—depends on the nature of the original defect.

You can watch a video of this technique that we’ve provided.

Several cautions should be taken with this technique, including:

- avoiding narrowing the vaginal canal

- minimizing trauma to healthy vaginal epithelium that will be used for closure

- maintaining hemostasis to avoid formation of hematomas.

Largest (>4 cm) exposures are likely the result of devascularized sloughing of vaginal epithelium. They are, fortunately, uncommon.

It’s unlikely that, after excision of exposed mesh, the vaginal epithelial edges can be approximated without significantly narrowing or shortening the vaginal canal. Proposed techniques for managing these large exposures include covering the defect with a biologic graft, such as small intestinal submucosa, to allow epithelium to re-grow. Regrettably, prolapse is likely to recur in the unprotected area that results.

Contraction and localized pain

Hardening and contraction typically occur along the fixation arms of the mesh. These complications might result from mesh shrinkage or from mesh being placed too tight, so to speak, at implantation. Rarely does the entire implanted mesh contract.

Severe mesh contraction can result in localized pain and de novo dyspareunia. Symptoms usually resolve after identification of the painful area and removal of the involved mesh segment.8

Diagnostic maneuver. In-office trigger-point injection of bupivacaine with triamcinolone is useful to accurately identify the location of pain that is causing dyspareunia. After injection, the patient is asked to return home and resume sexual intercourse; if dyspareunia diminishes significantly, surgical removal of the involved mesh segment is likely to ameliorate symptoms.

If dyspareunia persists after injection, however, the problem either 1) originates in a different location along the graft or 2) may not be related to the mesh—that is, it may be introital pain or preexisting vaginal pain.

The findings of trigger-point injection and a subsequent trial of sexual intercourse are useful for counseling the patient and developing realistic expectations that surgery will be successful.

Management note: Mesh contraction should be managed by a surgeon who is experienced in extensive deep pelvic dissection, which is necessary to remove the mesh arms.

Chronic pain

Diffuse vaginal pain after mesh implantation is unusual; typically, the patient’s report of pain has been preceded by recognition of another, underlying pelvic pain syndrome. Management of such pain is controversial, and many patients will not be satisfied until the entire graft is removed. Whether such drastic intervention actually resolves the pain is unclear; again, work with the patient to create realistic expectations before surgery—including the risk that prolapse will recur and that reoperation will be necessary.

Management note: An existing pelvic pain syndrome should be considered a relative contraindication to implantation of mesh.

Infection of the graft

Rarely, infection has been reported after implantation of Type-1 mesh—the result of either multi-microbial colonization or isolated infection by Bacteriodes melaninogenicus, Actinomyces spp, or Staphylococcus aureus. Untreated preoperative bacterial vaginitis is likely the underlying cause, and should be considered a contraindication to mesh implantation.

Typically, these patients complain of vaginal discharge and bleeding early postoperatively. Vaginal exposure of the mesh results from local inflammation and necrosis of tissue.

Management note: In these cases, it is necessary to 1) prescribe antimicrobial therapy that covers gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria and 2) undertake surgical removal of the exposed mesh, as we outlined above.9

Visceral erosion or fistula

Many experts believe that what is recorded as “erosion” of synthetic mesh into bladder or rectum is, in fact, a result of unrecognized visceral perforation at original implantation. This is a rare complication of mesh implantation.

Patients who experience mesh erosion into the bladder may have lower urinary-tract symptoms (LUTS) of urgency, frequency, dysuria, and hematuria. Any patient who reports de novo LUTS in the early postoperative period after a vaginal mesh procedure should receive office cystourethroscopy to ensure that no foreign body is present in the bladder or urethra.

Management note: Operative cystourethroscopy, with removal of exposed mesh, is the management of choice when mesh is found in the bladder or urethra.

Patients who have constant urinary or fecal incontinence immediately after surgery should be evaluated for vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistula.

The presence of any of these complications necessitates removal of the involved mesh in its entirety, with concomitant repair of fistula. Typically, the procedures are performed by a specialist.

Our experience with correcting simple mesh exposures

During the past year at our tertiary referral center, 26 patients have undergone mesh revision because of exposure, using the technique we described above (FIGURE 2-6). The problem resolved in all; none had persistent dyspareunia. Many of these patients had already undergone attempts at correction of the exposure elsewhere—mostly, in the office, using techniques appropriate for that setting. Prolapse has not recurred in the 10 patients who required reapproximation of mesh edges because of a defect >2.5 cm.

CASE RESOLVED: Treatment, improvement

Under your care, the patient undergoes simplified outpatient excision of the exposed area of mesh. Mesh edges are reapproximated to support the resulting 3-cm defect.

At a 12-week postop visit, you note complete resolution of the exposure and normal vaginal caliber. The patient continues to apply estrogen cream and reports sustained improvement in sexual function.

- Preoperatively, prepare the vaginal epithelium with local estrogen cream (recommended dosage: 1 g, two nights every week for a trial of at least 6 weeks)

- Use hydrodissection to facilitate placement of the graft deep to the vaginal epithelial fibromuscular fascial layer

- Do not place a synthetic mesh as an overlay to a midline fascial plication

- Be fastidious about hemostasis

- Close the vaginal epithelium without tension

- Leave vaginal packing in place for 24 hours

- Consider using biologic grafts when appropriate (as an overlay to midline plication when used on the anterior vaginal wall).

For simple presentations, success is within reach

Simple mesh exposure can (as in the case we described) be managed by most gynecologists, utilizing the simple stepwise approach that we outlined above (for additional tips based on our experience, see “Pearls for avoiding mesh exposures”). In the case of more significant symptoms, de novo dyspareunia, visceral erosion, or fistula, however, referral to a specialist is warranted.

Transvaginal mesh surgery reduces pelvic organ prolapse

But dyspareunia may develop in premenopausal women

Transvaginal mesh (TVM) surgery is effective in treating pelvic organ prolapse (POP) in both pre- and postmenopausal women but dyspareunia may worsen in premenopausal women, according to a study published online May 23 in the Journal of Sexual Medicine.

Cheng-Yu Long, MD, PhD, from Kaohsiung Medical University in Taiwan, and colleagues compared the changes in sexual function of premenopausal and postmenopausal women after TVM surgery. A total of 68 sexually active women, categorized as premenopausal (36) and postmenopausal (32), with symptomatic POP stages II to IV were referred for TVM surgery. Preoperative and postoperative assessments included pelvic examination using the POP quantification (POP-Q) system, and completing the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI), Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI-6), and Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ-7).

The investigators found significant improvement in the POP-Q analysis at points Aa, Ba, C, Ap, and Bp in both groups but not in total vaginal length. The UDI-6 and IIQ-7 scores decreased significantly after TVM surgery. The dyspareunia domain score decreased significantly after surgery only in the premenopausal group. Reports of diminished scores of the dyspareunia domain and total scores were more common among women in the premenopausal group, but there were no significant differences in FSFI domains or total scores between the groups.

Copyright © 2011 HealthDay. All rights reserved.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of prosthesis (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2011;22(1):3-15.

2. Davila GW, Drutz H, Deprest J. Clinical implications of the biology of grafts: conclusions of the 2005 IUGA Grafts Roundtable. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17(suppl 1):S51-55.

3. Iglesia CB, Sokol AI, Sokol ER, et al. Vaginal mesh for prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 1):293-303.

4. Hiltunen R, Nieminen K, Takala T, et al. Low-weight polypropylene mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 2):455-462.

5. Fatton B, Amblard J, Debodiance P, Cosson M, Jacquetin B. Transvaginal repair of genital prolapse: preliminary results of a new tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift technique)—a case series multicentric study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(7):743-752.

6. Diwadkar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, Maher C, Jelovsek JE. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2):367-373.

7. Nguyen JN, Burchette RJ. Outcome after anterior vaginal prolapse repair: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):891-898.

8. Feiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition clinical presentation, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 2):325-330.

9. Athanasiou S, Matthaiou DK, Falagas ME. Vaginal mesh infection due to Bacteroides melaninogenicus: a case report of another emerging foreign body related infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38(11-12):1108-1110.

1. Haylen BT, Freeman RM, Swift SE, et al. An International Urogynecological Association (IUGA)/International Continence Society (ICS) joint terminology and classification of the complications related directly to the insertion of prosthesis (meshes, implants, tapes) and grafts in female pelvic floor surgery. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2011;22(1):3-15.

2. Davila GW, Drutz H, Deprest J. Clinical implications of the biology of grafts: conclusions of the 2005 IUGA Grafts Roundtable. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2006;17(suppl 1):S51-55.

3. Iglesia CB, Sokol AI, Sokol ER, et al. Vaginal mesh for prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;116(2 pt 1):293-303.

4. Hiltunen R, Nieminen K, Takala T, et al. Low-weight polypropylene mesh for anterior vaginal wall prolapse: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(2 pt 2):455-462.

5. Fatton B, Amblard J, Debodiance P, Cosson M, Jacquetin B. Transvaginal repair of genital prolapse: preliminary results of a new tension-free vaginal mesh (Prolift technique)—a case series multicentric study. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2007;18(7):743-752.

6. Diwadkar GB, Barber MD, Feiner B, Maher C, Jelovsek JE. Complication and reoperation rates after apical vaginal prolapse surgical repair. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(2):367-373.

7. Nguyen JN, Burchette RJ. Outcome after anterior vaginal prolapse repair: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111(4):891-898.

8. Feiner B, Maher C. Vaginal mesh contraction: definition clinical presentation, and management. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115(2 pt 2):325-330.

9. Athanasiou S, Matthaiou DK, Falagas ME. Vaginal mesh infection due to Bacteroides melaninogenicus: a case report of another emerging foreign body related infection. Scand J Infect Dis. 2006;38(11-12):1108-1110.

Pessary and pelvic floor exercises for incontinence—are two better than one?

Because we will all be seeing more patients with stress urinary incontinence and other urogynecologic issues, it is critical that we keep abreast of the treatment options available—and their relative effectiveness.1

In this exploration of nonsurgical approaches to stress incontinence, Richter and colleagues started with the premise that a combination of instructed pelvic floor exercises and an incontinence pessary would be better than either treatment alone. They (very appropriately) designated the following as primary outcome measures:

- patient-reported improvement

- symptoms of stress incontinence

- patient satisfaction, as measured using validated instruments.

As reported above, combination therapy did not prove to be superior to single-modality intervention. And although behavioral therapy was superior to a pessary at 3 months, by 12 months the modalities were roughly equivalent, and only about half of patients were still using the prescribed therapy: pessary (45%) or pelvic floor exercises (57%).

This is not a real-world study

Most women who have stress incontinence and who select nonsurgical therapy choose only one option—pelvic floor exercises (if very motivated), a vaginal pessary or other device (if not so motivated), or another conservative option such as radiofrequency therapy (if even less motivated). In this study, women enrolled in behavioral therapy paid four visits (at roughly 2-week intervals) to approved “interventionists,” who instructed them in the technique for pelvic floor exercise and explained other skills and strategies to prevent urge and stress incontinence.

Many women find it difficult to attend the four to eight physiotherapy sessions that are necessary for behavioral intervention and are unwilling to devote 1 year to a therapy that they don’t find effective early on. (Physiotherapy is effective but requires a motivated patient.) Other women dislike inserting a vaginal device on a regular basis. 2

What’s more, very safe minimally invasive slings are available that offer more definitive therapy to patients who have stress incontinence. That said, a sling procedure should not be undertaken lightly. Patient selection should be based on preoperative testing, including an assessment of urethral function, for the transobturator sling.3 A retropubic sling requires a greater degree of expertise to tension appropriately but is suitable for a wider range of severity, including intrinsic sphincteric deficiency. The role of single-incision slings is unclear.

Bottom line: individualize care

The authors’ concluding statements are right on the money: “Individualization of care should continue to be the cornerstone of our approach to [stress incontinent] patients.” These women have several effective options available. We should help them make an educated choice based on symptom severity, lifestyle, and willingness to enroll in self-help intervention versus surgical therapy.

Many patients seek to avoid surgery, either because they believe that their stress incontinence is not severe enough to warrant it, or because they are unwilling to take the 6 to 8 weeks of relative inactivity required for the sling to settle in.

In the absence of approved pharmacotherapy for stress incontinence, I tell patients that they 1) can expect their symptoms to become worse over time and 2) should designate a period of time for a trial of conservative therapy—usually, 3 months. If their condition has not improved to their satisfaction over that period, I recommend that they identify a 6-week window during which they can avoid the gym and the golf course, as well as sexual activity, to allow for unstressed healing from a sling procedure.—G. WILLY DAVILA, MD

1. Wu JM, Hundley AF, Fulton RG, Myers ER. Forecasting the prevalence of pelvic floor disorders in US women: 2010 to 2050. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(6):1278-1283.

2. Davila GW, Bernier F. Multimodality pelvic physiotherapy treatment of urinary incontinence in adult women. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 1995;6(4):187-194.

3. Guerette N, Bena J, Davila GW. Transobturator slings for stress incontinence: using urodynamic parameters to predict outcomes. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct. 2008;19(1):97-102.

Because we will all be seeing more patients with stress urinary incontinence and other urogynecologic issues, it is critical that we keep abreast of the treatment options available—and their relative effectiveness.1

In this exploration of nonsurgical approaches to stress incontinence, Richter and colleagues started with the premise that a combination of instructed pelvic floor exercises and an incontinence pessary would be better than either treatment alone. They (very appropriately) designated the following as primary outcome measures:

- patient-reported improvement

- symptoms of stress incontinence

- patient satisfaction, as measured using validated instruments.

As reported above, combination therapy did not prove to be superior to single-modality intervention. And although behavioral therapy was superior to a pessary at 3 months, by 12 months the modalities were roughly equivalent, and only about half of patients were still using the prescribed therapy: pessary (45%) or pelvic floor exercises (57%).

This is not a real-world study

Most women who have stress incontinence and who select nonsurgical therapy choose only one option—pelvic floor exercises (if very motivated), a vaginal pessary or other device (if not so motivated), or another conservative option such as radiofrequency therapy (if even less motivated). In this study, women enrolled in behavioral therapy paid four visits (at roughly 2-week intervals) to approved “interventionists,” who instructed them in the technique for pelvic floor exercise and explained other skills and strategies to prevent urge and stress incontinence.

Many women find it difficult to attend the four to eight physiotherapy sessions that are necessary for behavioral intervention and are unwilling to devote 1 year to a therapy that they don’t find effective early on. (Physiotherapy is effective but requires a motivated patient.) Other women dislike inserting a vaginal device on a regular basis. 2

What’s more, very safe minimally invasive slings are available that offer more definitive therapy to patients who have stress incontinence. That said, a sling procedure should not be undertaken lightly. Patient selection should be based on preoperative testing, including an assessment of urethral function, for the transobturator sling.3 A retropubic sling requires a greater degree of expertise to tension appropriately but is suitable for a wider range of severity, including intrinsic sphincteric deficiency. The role of single-incision slings is unclear.

Bottom line: individualize care

The authors’ concluding statements are right on the money: “Individualization of care should continue to be the cornerstone of our approach to [stress incontinent] patients.” These women have several effective options available. We should help them make an educated choice based on symptom severity, lifestyle, and willingness to enroll in self-help intervention versus surgical therapy.

Many patients seek to avoid surgery, either because they believe that their stress incontinence is not severe enough to warrant it, or because they are unwilling to take the 6 to 8 weeks of relative inactivity required for the sling to settle in.

In the absence of approved pharmacotherapy for stress incontinence, I tell patients that they 1) can expect their symptoms to become worse over time and 2) should designate a period of time for a trial of conservative therapy—usually, 3 months. If their condition has not improved to their satisfaction over that period, I recommend that they identify a 6-week window during which they can avoid the gym and the golf course, as well as sexual activity, to allow for unstressed healing from a sling procedure.—G. WILLY DAVILA, MD