User login

Can genetics predict risk for alcohol dependence?

Children of alcoholics have a 40% to 60% increased risk of developing severe alcohol-related problems1—a harsh legacy recognized for >30 years. Now, as the result of rapidly growing evidence, we can explain in greater detail why alcoholism runs in families when discussing alcohol dependence with patients.

Individuals vary in response to medications and substances of abuse, and genetic research is revealing the heritable origins. Numerous genetic variations are known to influence response to alcohol, as well as alcoholism’s pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment. Pieces are still missing from this complex picture, but investigators are identifying possible risk factors for alcoholism and matching potential responders with treatments such as naltrexone and acamprosate.

This article provides a progress report on contemporary genetic research of alcoholism. Our goal is to inform your clinical practice by describing:

- new understandings of the genetics of alcoholism

- how researchers identify relationships between genetic variations and clinical/behavioral phenomena

- practical implications of this knowledge.

Genetic variations and risk of addiction

No single gene appears to cause alcoholism. Many genetic variations that accumulated during evolution likely contribute to individual differences in response to alcohol and susceptibility to developing alcohol-related problems. A growing number of genetic variations have been associated with increased alcohol tolerance, consumption, and other related phenotypes.

Like other addictive substances, alcohol triggers pharmacodynamic effects by interacting with a variety of molecular targets (Figure 1).2 These target proteins in turn interact with specific signaling proteins and trigger responses in complex functional pathways. Genetic variations may affect the structure of genes coding for proteins that constitute pathways involved in alcohol’s effects on target proteins (pharmacodynamics) or its metabolism (pharmacokinetics). If such variations alter the production, function, or stability of these proteins, the pathway’s function also may be altered and produce behavioral phenotypes—such as high or low sensitivity to alcohol’s effects.

Alcoholism-related phenotypes. DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria include some but not all of the multiple phenotypes within alcoholism’s clinical presentation. Researchers in the Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA)3 identified chromosome regions linked to alcoholism-related phenotypes, including:

- alcohol dependence4

- later age of drinking onset and increased harm avoidance5

- alcoholism and depression6

- alcohol sensitivity7

- alcohol consumption.8

To identify genes of interest within these chromosome regions, researchers used transitional phenotypes (endophenotypes) that “lie on the pathway between genes and disease,”9,10 and allowed them to characterize the neural systems affected by gene risk variants.11 As a result, they found associations among variations in the GABRA2 gene, (encoding the alpha-2 subunit of the GABAA receptor), specific brain oscillations (electrophysiologic endophenotype), and predisposition to alcohol dependence.12,13 By this same strategy, researchers discovered an association between the endophenotype (low-level of response to alcohol) and some genotypes, including at least 1 short allele of the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4.14

Figure 1

Known molecular targets for alcohol and other drugs of abuse

Effects of drugs of abuse (black arrows) influence intracellular signaling pathways (blue arrows) to produce immediate and long-term changes in cell function.

cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; GABAA: gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor; Gi, Gs, Gq: G proteins (heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins) MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; N-cholino receptor: nicotinic cholinoreceptor; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; PKA: protein kinase A

Source: Created for CURRENT PSYCHIATRY from information in reference 2

Alcohol metabolism

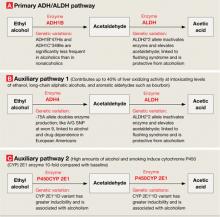

Alcohol is metabolized to acetic acid through primary and auxiliary pathways involving alcohol and acetaldehyde dehydrogenases (ADH/ALDH) and the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (cytochrome P-450 [CYP] 2E1)15 (Figure 2). Auxiliary pathways become involved when the primary pathway is overwhelmed by the amount of alcohol needed to be metabolized. Catalase and fatty acid ethyl ester synthases play a minor role under normal conditions but may be implicated in alcohol-induced organ damage.16

ADH/ALDH pathway. From one individual to another, the ability to metabolize ethyl alcohol varies up to 3- to 4-fold.17 In European and Amerindian samples, a genetic link has been identified between alcoholism and the 4q21-23 region on chromosome 4.18 This region contains a cluster of 7 genes encoding for alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH), including 3 Class I genes—ADH1A, ADH1B, and ADH1C—coding for the corresponding proteins that play a major role in alcohol metabolism.19 In eastern Asian samples, alleles encoding high activity enzymes (ADH1B*47His and ADH1C*349Ile) are significantly less frequent in alcoholics compared with nonalcoholic controls.20

Mitochondrial ALDH2 protein plays the central role in acetaldehyde metabolism and is highly expressed in the liver, stomach, and other tissues—including the brain.21 The ALDH2*2 gene variant encodes for a catalytically inactive enzyme, thus inhibiting acetaldehyde metabolism and causing a facial flushing reaction.22 The ALDH2*2 allele has a relatively high frequency in Asians but also is found in other populations.23 Meta-analyses of published data indicate that possessing either of the variant alleles in the ADH1B and ALDH2 genes is protective against alcohol dependence in Asians.24

The ADH4 enzyme catalyzes oxidation or reduction of numerous substrates—including long-chain aliphatic alcohols and aromatic aldehydes—and becomes involved in alcohol metabolism at moderate to high concentrations. The -75A allele of the ADH4 gene has promoter activity more than twice that of the -75C allele and significantly affects its expression.25 This substitution in the promoter region, as well as A/G SNP (rs1042364)—a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)—at exon 9, has been associated with an increased risk for alcohol and drug dependence in European Americans.26

Finally, variations in the ADH7 gene may play a protective role against alcoholism through epistatic effects.27

The CYP 2E1 pathway has low initial catalytic efficiency compared with the ADH/ALDH pathway, but it may metabolize alcohol up to 10 times faster after chronic alcohol consumption or cigarette smoking and accounts for metabolic tolerance.28 CYP 2E1 is involved in metabolizing both alcohol and acetaldehyde.29 The CYP 2E1*1D polymorphism has been associated with greater inducibility as well as alcohol and nicotine dependence.30

Thus, linkage and association studies support the association of phenotypes related to alcohol response and dependence with variations in genes that code for proteins involved in alcohol’s pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic effects. Each of these findings is important, but conceptual models organizing them all and explaining their role in alcohol’s effects and predisposition to alcoholism have yet to be constructed.

Figure 2

Genetic variations that affect alcohol metabolism pathways

Genetic variations affect the efficiency of primary and auxiliary pathways by which ethyl alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde and acetic acid. Auxiliary pathways become involved when the primary pathway is overwhelmed by the amount of alcohol to be metabolized.

ADH: alcohol dehydrogenase; ALDH: acetaldehyde dehydrogenase; P450CYP 2E1: cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily E, polypeptide 1; A/G SNP: adenine/guanine single nucleotide polymorphism

Phenotype-genotype relationships

Alcohol—unlike most other addictive substances—does not have a specific receptor and is believed to act by disturbing the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission in the neural system. Consequently, researchers explore relationships between genetics and alcohol-related problems using 2 approaches:

- Forward genetics (discovering disease-related genes via genome-wide studies and then studying their function; examples include linkage and genome-wide association studies [GWAS]).

- Reverse genetics (testing whether candidate genes and polymorphisms identified in animal studies as relevant for biological effects also exist in humans and are relevant to the phenotype).31

When searching for relationships between genotypes and phenotypes, both approaches must take into account a framework of functional anatomic and physiologic connections (Figure 3).

Linkage studies. The goal of linkage studies is to find a link between a phenotypic variation (ideally a measurable trait, such as number of drinks necessary for intoxication) and the chromosomal marker expected to be in the vicinity of the disease-specific gene variation. An advantage of linkage studies is that they can be started without knowing specific DNA sequences. Their limitations include:

- limited power when applied to complex diseases such as alcoholism

- they do not yield gene-specific information

- their success is highly dependent on family members’ willingness to participate.

Association studies. Candidate gene-based association studies are designed to directly test a potential association between the phenotype of interest and a known genomic sequence variation. This approach provides adequate power to study variations with modest effects and allows use of DNA from unrelated individuals. The candidate gene approach has revealed associations between specific genomic variations and phenotypes related to alcohol misuse and alcoholism (Table).

Like linkage studies, association studies have their own challenges and limitations, such as:

- historically high false-positive rates

- confounding risks (allele frequencies may vary because of ethnic stratification rather than disease predisposition).

To address these challenges, researchers must carefully choose behavioral, physiologic, or intermediate phenotypes and genotype variations, as well as control subjects and sample sizes. Replication studies are necessary to rule out false-positive associations. In fact, only some of the findings depicted in the Table—those related to GABRA2 and GABRA6 and few other genes—have been replicated.

Genome-wide association studies are a powerful new method for studying relationships between genomic variability and behavior. With GWAS, thousands of DNA samples can be scanned for thousands of SNPs throughout the human genome, with the goal of identifying variations that modestly increase the risk of developing common diseases.

Unlike the candidate gene approach—which focuses on preselected genomic variations—GWAS scans the whole genome and may identify unexpected susceptibility factors. Unlike the family-based linkage approach, GWAS is not limited to specific families and can address all recombination events in a population.

Challenges are associated with GWAS, however, and include:

- need for substantial numbers (2,000 to 5,000) of rigorously described cases and matched controls

- need for accurate, high-throughput genotyping technologies and sophisticated algorithms for analyzing data

- risk of high false-positive rates related to multiple testing

- inability to scan 100% of the genome, which may lead to false-negative findings.

Table

Examples of gene variations related to alcohol misuse and alcoholism phenotypes

| Phenotype | Gene variation(s) |

|---|---|

| Related to alcohol misuse | |

| Low response/high tolerance to alcohol | L allele of serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) and Ser385 allele of alpha-6 subunit of GABAA receptor gene (GABRA6) in adolescents and healthy adult men;a,b 600G allele of alpha-2 subunit of GABAA receptor gene (GABRA2) in healthy social drinkersc |

| Cue-related craving for alcohol | 118G allele of opioid μ-receptor gene (OMPR) and L allele of dopamine receptor type 4 gene (DRD4) in young problem drinkersd,e |

| Binge drinking | S allele of serotonin transporter gene in college students; combination of SS genotype of serotonin transporter gene and HH genotype of MAOA gene in young womenf |

| Related to alcoholism | |

| Alcohol dependence | Two common haplotypes of GABRA2 geneg |

| Liver cirrhosis in alcoholics | -238A allele of tumor necrosis factor gene (TNFA)h |

| Protects against withdrawal symptoms in alcoholics | -141C Del variant of the dopamine receptor type 2 gene (DRD2)i |

| Associated with delirium tremens | 8 genetic polymorphisms in 3 candidate genes involved in the dopamine transmission (DRD2, DRD3, and SLC6A3), 1 gene involved in the glutamate pathway (GRIK3), 1 neuropeptide gene (BDNF), and 1 cannabinoid gene (CNR1)j |

| Associated with alcohol withdrawal seizures | 9 repeat allele of dopamine transporter (SLC6A3); 10 repeat allele of tyrosine hydroxylase gene (TH); Ser9 allele of dopamine receptor type 3 gene (DRD3); SS genotype of serotonin transporter gene; 2108A allele in NR1 subunit of NMDA receptor gene (GRIN1)k-m |

| GABAA: gamma-aminobutyric acid A; MAOA: monoamine oxidase A; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate | |

| Source: Click here to view references | |

Figure 3

2 ways to seek relationships between genes and behavior

Researchers use ‘forward’ and ‘reverse’ genetics to connect behavioral phenotypes with predisposing genotypes. Each approach must consider intermediary functional anatomic and physiologic levels (black box), as shown in this conceptual framework.

DA: dopamine; EEG: electroencephalography; 5-HT: serotonin; LTD: long-term depression; LTP: long-term potentiation; RNA: ribonucleic acid; SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms; VNTRs: variable number tandem (triplet) repeats

Clinical implications

Genomic research is increasing our understanding of alcohol’s pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions and of potential genetic associations with alcoholic phenotypes. These insights may lead to discovery of new therapies to compensate for specific physiologic and behavioral dysfunctions. For example, medications with pharmacologic profiles complimentary to addiction-related physiologic/behavioral deficits might be designed in the future.

Likewise, new understandings about genetic variability may allow us to predict an individual’s ability to tolerate and respond to existing medications used to treat alcohol dependence. For example, in studies of alcoholic and nonalcoholic subjects:

- Individuals with the 118G variant allele of the μ-opioid receptor may experience a stronger subjective response to alcohol and respond more robustly to naltrexone treatment than do carriers of the more common 118A allele.32

- Persons with a functional variation in the DRD4 gene (7 repeat allele–DRD4L) coding for type 4 dopamine receptor reported greater euphoria and reward while drinking alcohol and reduced alcohol consumption during 12-week treatment with olanzapine, a DRD2/DRD4 blocker.33

Applying this approach to the study of acamprosate has been difficult because of uncertainty about which protein molecules it targets. Variation in the Per2 gene (coding for protein involved in the circadian cycle) has been shown to be associated with brain glutamate levels, alcohol consumption, and the effects of acamprosate, although these interactions require further investigation.34

Pharmacogenomics of alcoholism treatment is in a very early stage of development. Findings require replication in different clinical samples and functional analysis. At the same time, if the reported association between the μ-opioid receptor genetic variation and naltrexone’s treatment efficacy is confirmed, this finding could help to guide clinical practice. Studies of genomic predictors of other medications’ efficacy and tolerability for alcoholism treatment would be expected to follow.

Related resources

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA). www.niaaa.nih.gov (search NIAAA-funded collaborative research programs).

- Dick DM, Jones K, Saccone N, et al. Endophenotypes successfully lead to gene identification: results from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Behav Genet 2006;36(1):112-26.

Drug brand names

- Acamprosate • Campral

- Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the S.C. Johnson Genomic of Addictions Program. The authors thank Ms. Barbara Hall for expert technical assistance in preparing this manuscript.

1. Schuckit MA, Goodwin DA, Winokur G. A study of alcoholism in half siblings. Am J Psychiatry 1972;128(9):1132-6.

2. Nestler E. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 2001;2(2):119-28.

3. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA). Available at: http://zork.wustl.edu/niaaa. Accessed January 28, 2008.

4. Foroud T, Edenberg HJ, Goate A, et al. Alcoholism susceptibility loci: confirmation studies in a replicate sample and further mapping. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000;24(7):933-45.

5. Dick DM, Nurnberger J, Jr, Edenberg HJ, et al. Suggestive linkage on chromosome 1 for a quantitative alcohol-related phenotype. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2002;26(10):1453-60.

6. Nurnberger JI, Jr, Foroud T, Flury L, et al. Evidence for a locus on chromosome 1 that influences vulnerability to alcoholism and affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(5):718-24.

7. Schuckit MA, Edenberg HJ, Kalmijn J, et al. A genome-wide search for genes that relate to a low level of response to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25(3):323-9.

8. Saccone NL, Kwon JM, Corbett J, et al. A genome screen of maximum number of drinks as an alcoholism phenotype. Am J Med Genet 2000;96(5):632-7.

9. Gottesman II, Shields J. Schizophrenia and genetics;a twin study vantage point. New York, NY: Academic Press;1972.

10. Rieder RO, Gershon ES. Genetic strategies in biological psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978;35(7):866-73.

11. Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR. Intermediate phenotypes and genetic mechanisms of psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006;7(10):818-27.

12. Dick DM, Jones K, Saccone N, et al. Endophenotypes successfully lead to gene identification: results from the Collaborative Study on Genetics of Alcoholism. Behav Genet 2006;36(1):112-26.

13. Edenberg HJ, Dick DM, Xuei X, et al. Variations in GABRA2, encoding the alpha 2 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor, are associated with alcohol dependence and with brain oscillations. Am J Hum Genet 2004;74(4):705-14.

14. Hinckers AS, Laucht M, Schmidt MH, et al. Low level of response to alcohol as associated with serotonin transporter genotype and high alcohol intake in adolescents. Biol Psychiatry 2006;60(3):282-7.

15. Ramchandani VA, Bosron WF, Li TK. Research advances in ethanol metabolism. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2001;49(9):676-82.

16. Beckemeier ME, Bora PS. Fatty acid ethyl esters: potentially toxic products of myocardial ethanol metabolism. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1998;30(11):2487-94.

17. Li TK, Yin SJ, Crabb DW, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on alcohol metabolism in humans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25(1):136-44.

18. Long JC, Knowler WC, Hanson RL, et al. Evidence for genetic linkage to alcohol dependence on chromosomes 4 and 11 from an autosome-wide scan in an American Indian population. Am J Med Genet 1998;81(3):216-21.

19. Edenberg HJ. Regulation of the mammalian alcohol dehydrogenase genes. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 2000;64:295-341.

20. Osier M, Pakstis A, Soodyall H, et al. A global perspective on genetic variation at the ADH genes reveals unusual patterns of linkage disequilibrium and diversity. Am J Hum Genet 2002;71(1):84-99.

21. Yoshida A, Rzhetsky A, Hsu LC, Chang C. Human aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family. Eur J Biochem 1998;251(3):549-57.

22. Harada S, Agarwal DP, Goedde HW. Aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency as a cause of facial flashing reaction to alcohol in Japanese. Lancet 1981;2(8253):982.-

23. Goedde HW, Agarwal DP, Fritze G, et al. Distribution of ADH2 and ALDH2 genotypes in different populations. Hum Genet 1992;88(3):344-6.

24. Luczak SE, Glatt SJ, Wall TJ. Meta-analyses of ALDH2 and ADH1B with alcohol dependence in Asians. Psychol Bull 2006;132(4):607-21.

25. Edenberg HJ, Jerome RE, Li M. Polymorphism of the human alcohol dehydrogenase 4 (ADH4) promoter affects gene expression. Pharmacogenetics 1999;9(1):25-30.

26. Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, et al. ADH4 gene variation is associated with alcohol dependence and drug dependence in European Americans: results from HWD tests and case-control association studies. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31(5):1085-95.

27. Osier MV, Lu RB, Pakstis AJ, et al. Possible epistatic role of ADH7 in the protection against alcoholism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2004;126(1):19-22.

28. Lieber CS. Microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system (MEOS): the first 30 years (1968-1998)—a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999;23(6):991-1007.

29. Kunitoh S, Imaoka S, Hiroi T, et al. Acetaldehyde as well as ethanol is metabolized by human CYP2E1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997;280(2):527-32.

30. Howard LA, Ahluwalia JS, Lin SK, et al. CYP2E1*1D regulatory polymorphism: association with alcohol and nicotine dependence [erratum in Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(7):441-2]. Pharmacogenetics 2003;13(6):321-8.

31. Risch NJ. Searching for genetic determinants in the new millennium. Nature 2000;405(6788):847-56.

32. Oslin DW, Berrettini W, Kranzler HR, et al. A functional polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor gene is associated with naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003;28:1546-52.

33. Hutchison KE, Ray L, Sandman E, et al. The effect of olanzapine on craving and alcohol consumption. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31(6):1310-7.

34. Spanagel R, Pendyala G, Abarca C, et al. The clock gene Per2 influences the glutamatergic system and modulates alcohol consumption. Nat Med 2005;11(1):35-42.

Children of alcoholics have a 40% to 60% increased risk of developing severe alcohol-related problems1—a harsh legacy recognized for >30 years. Now, as the result of rapidly growing evidence, we can explain in greater detail why alcoholism runs in families when discussing alcohol dependence with patients.

Individuals vary in response to medications and substances of abuse, and genetic research is revealing the heritable origins. Numerous genetic variations are known to influence response to alcohol, as well as alcoholism’s pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment. Pieces are still missing from this complex picture, but investigators are identifying possible risk factors for alcoholism and matching potential responders with treatments such as naltrexone and acamprosate.

This article provides a progress report on contemporary genetic research of alcoholism. Our goal is to inform your clinical practice by describing:

- new understandings of the genetics of alcoholism

- how researchers identify relationships between genetic variations and clinical/behavioral phenomena

- practical implications of this knowledge.

Genetic variations and risk of addiction

No single gene appears to cause alcoholism. Many genetic variations that accumulated during evolution likely contribute to individual differences in response to alcohol and susceptibility to developing alcohol-related problems. A growing number of genetic variations have been associated with increased alcohol tolerance, consumption, and other related phenotypes.

Like other addictive substances, alcohol triggers pharmacodynamic effects by interacting with a variety of molecular targets (Figure 1).2 These target proteins in turn interact with specific signaling proteins and trigger responses in complex functional pathways. Genetic variations may affect the structure of genes coding for proteins that constitute pathways involved in alcohol’s effects on target proteins (pharmacodynamics) or its metabolism (pharmacokinetics). If such variations alter the production, function, or stability of these proteins, the pathway’s function also may be altered and produce behavioral phenotypes—such as high or low sensitivity to alcohol’s effects.

Alcoholism-related phenotypes. DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria include some but not all of the multiple phenotypes within alcoholism’s clinical presentation. Researchers in the Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA)3 identified chromosome regions linked to alcoholism-related phenotypes, including:

- alcohol dependence4

- later age of drinking onset and increased harm avoidance5

- alcoholism and depression6

- alcohol sensitivity7

- alcohol consumption.8

To identify genes of interest within these chromosome regions, researchers used transitional phenotypes (endophenotypes) that “lie on the pathway between genes and disease,”9,10 and allowed them to characterize the neural systems affected by gene risk variants.11 As a result, they found associations among variations in the GABRA2 gene, (encoding the alpha-2 subunit of the GABAA receptor), specific brain oscillations (electrophysiologic endophenotype), and predisposition to alcohol dependence.12,13 By this same strategy, researchers discovered an association between the endophenotype (low-level of response to alcohol) and some genotypes, including at least 1 short allele of the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4.14

Figure 1

Known molecular targets for alcohol and other drugs of abuse

Effects of drugs of abuse (black arrows) influence intracellular signaling pathways (blue arrows) to produce immediate and long-term changes in cell function.

cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; GABAA: gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor; Gi, Gs, Gq: G proteins (heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins) MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; N-cholino receptor: nicotinic cholinoreceptor; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; PKA: protein kinase A

Source: Created for CURRENT PSYCHIATRY from information in reference 2

Alcohol metabolism

Alcohol is metabolized to acetic acid through primary and auxiliary pathways involving alcohol and acetaldehyde dehydrogenases (ADH/ALDH) and the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (cytochrome P-450 [CYP] 2E1)15 (Figure 2). Auxiliary pathways become involved when the primary pathway is overwhelmed by the amount of alcohol needed to be metabolized. Catalase and fatty acid ethyl ester synthases play a minor role under normal conditions but may be implicated in alcohol-induced organ damage.16

ADH/ALDH pathway. From one individual to another, the ability to metabolize ethyl alcohol varies up to 3- to 4-fold.17 In European and Amerindian samples, a genetic link has been identified between alcoholism and the 4q21-23 region on chromosome 4.18 This region contains a cluster of 7 genes encoding for alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH), including 3 Class I genes—ADH1A, ADH1B, and ADH1C—coding for the corresponding proteins that play a major role in alcohol metabolism.19 In eastern Asian samples, alleles encoding high activity enzymes (ADH1B*47His and ADH1C*349Ile) are significantly less frequent in alcoholics compared with nonalcoholic controls.20

Mitochondrial ALDH2 protein plays the central role in acetaldehyde metabolism and is highly expressed in the liver, stomach, and other tissues—including the brain.21 The ALDH2*2 gene variant encodes for a catalytically inactive enzyme, thus inhibiting acetaldehyde metabolism and causing a facial flushing reaction.22 The ALDH2*2 allele has a relatively high frequency in Asians but also is found in other populations.23 Meta-analyses of published data indicate that possessing either of the variant alleles in the ADH1B and ALDH2 genes is protective against alcohol dependence in Asians.24

The ADH4 enzyme catalyzes oxidation or reduction of numerous substrates—including long-chain aliphatic alcohols and aromatic aldehydes—and becomes involved in alcohol metabolism at moderate to high concentrations. The -75A allele of the ADH4 gene has promoter activity more than twice that of the -75C allele and significantly affects its expression.25 This substitution in the promoter region, as well as A/G SNP (rs1042364)—a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)—at exon 9, has been associated with an increased risk for alcohol and drug dependence in European Americans.26

Finally, variations in the ADH7 gene may play a protective role against alcoholism through epistatic effects.27

The CYP 2E1 pathway has low initial catalytic efficiency compared with the ADH/ALDH pathway, but it may metabolize alcohol up to 10 times faster after chronic alcohol consumption or cigarette smoking and accounts for metabolic tolerance.28 CYP 2E1 is involved in metabolizing both alcohol and acetaldehyde.29 The CYP 2E1*1D polymorphism has been associated with greater inducibility as well as alcohol and nicotine dependence.30

Thus, linkage and association studies support the association of phenotypes related to alcohol response and dependence with variations in genes that code for proteins involved in alcohol’s pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic effects. Each of these findings is important, but conceptual models organizing them all and explaining their role in alcohol’s effects and predisposition to alcoholism have yet to be constructed.

Figure 2

Genetic variations that affect alcohol metabolism pathways

Genetic variations affect the efficiency of primary and auxiliary pathways by which ethyl alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde and acetic acid. Auxiliary pathways become involved when the primary pathway is overwhelmed by the amount of alcohol to be metabolized.

ADH: alcohol dehydrogenase; ALDH: acetaldehyde dehydrogenase; P450CYP 2E1: cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily E, polypeptide 1; A/G SNP: adenine/guanine single nucleotide polymorphism

Phenotype-genotype relationships

Alcohol—unlike most other addictive substances—does not have a specific receptor and is believed to act by disturbing the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission in the neural system. Consequently, researchers explore relationships between genetics and alcohol-related problems using 2 approaches:

- Forward genetics (discovering disease-related genes via genome-wide studies and then studying their function; examples include linkage and genome-wide association studies [GWAS]).

- Reverse genetics (testing whether candidate genes and polymorphisms identified in animal studies as relevant for biological effects also exist in humans and are relevant to the phenotype).31

When searching for relationships between genotypes and phenotypes, both approaches must take into account a framework of functional anatomic and physiologic connections (Figure 3).

Linkage studies. The goal of linkage studies is to find a link between a phenotypic variation (ideally a measurable trait, such as number of drinks necessary for intoxication) and the chromosomal marker expected to be in the vicinity of the disease-specific gene variation. An advantage of linkage studies is that they can be started without knowing specific DNA sequences. Their limitations include:

- limited power when applied to complex diseases such as alcoholism

- they do not yield gene-specific information

- their success is highly dependent on family members’ willingness to participate.

Association studies. Candidate gene-based association studies are designed to directly test a potential association between the phenotype of interest and a known genomic sequence variation. This approach provides adequate power to study variations with modest effects and allows use of DNA from unrelated individuals. The candidate gene approach has revealed associations between specific genomic variations and phenotypes related to alcohol misuse and alcoholism (Table).

Like linkage studies, association studies have their own challenges and limitations, such as:

- historically high false-positive rates

- confounding risks (allele frequencies may vary because of ethnic stratification rather than disease predisposition).

To address these challenges, researchers must carefully choose behavioral, physiologic, or intermediate phenotypes and genotype variations, as well as control subjects and sample sizes. Replication studies are necessary to rule out false-positive associations. In fact, only some of the findings depicted in the Table—those related to GABRA2 and GABRA6 and few other genes—have been replicated.

Genome-wide association studies are a powerful new method for studying relationships between genomic variability and behavior. With GWAS, thousands of DNA samples can be scanned for thousands of SNPs throughout the human genome, with the goal of identifying variations that modestly increase the risk of developing common diseases.

Unlike the candidate gene approach—which focuses on preselected genomic variations—GWAS scans the whole genome and may identify unexpected susceptibility factors. Unlike the family-based linkage approach, GWAS is not limited to specific families and can address all recombination events in a population.

Challenges are associated with GWAS, however, and include:

- need for substantial numbers (2,000 to 5,000) of rigorously described cases and matched controls

- need for accurate, high-throughput genotyping technologies and sophisticated algorithms for analyzing data

- risk of high false-positive rates related to multiple testing

- inability to scan 100% of the genome, which may lead to false-negative findings.

Table

Examples of gene variations related to alcohol misuse and alcoholism phenotypes

| Phenotype | Gene variation(s) |

|---|---|

| Related to alcohol misuse | |

| Low response/high tolerance to alcohol | L allele of serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) and Ser385 allele of alpha-6 subunit of GABAA receptor gene (GABRA6) in adolescents and healthy adult men;a,b 600G allele of alpha-2 subunit of GABAA receptor gene (GABRA2) in healthy social drinkersc |

| Cue-related craving for alcohol | 118G allele of opioid μ-receptor gene (OMPR) and L allele of dopamine receptor type 4 gene (DRD4) in young problem drinkersd,e |

| Binge drinking | S allele of serotonin transporter gene in college students; combination of SS genotype of serotonin transporter gene and HH genotype of MAOA gene in young womenf |

| Related to alcoholism | |

| Alcohol dependence | Two common haplotypes of GABRA2 geneg |

| Liver cirrhosis in alcoholics | -238A allele of tumor necrosis factor gene (TNFA)h |

| Protects against withdrawal symptoms in alcoholics | -141C Del variant of the dopamine receptor type 2 gene (DRD2)i |

| Associated with delirium tremens | 8 genetic polymorphisms in 3 candidate genes involved in the dopamine transmission (DRD2, DRD3, and SLC6A3), 1 gene involved in the glutamate pathway (GRIK3), 1 neuropeptide gene (BDNF), and 1 cannabinoid gene (CNR1)j |

| Associated with alcohol withdrawal seizures | 9 repeat allele of dopamine transporter (SLC6A3); 10 repeat allele of tyrosine hydroxylase gene (TH); Ser9 allele of dopamine receptor type 3 gene (DRD3); SS genotype of serotonin transporter gene; 2108A allele in NR1 subunit of NMDA receptor gene (GRIN1)k-m |

| GABAA: gamma-aminobutyric acid A; MAOA: monoamine oxidase A; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate | |

| Source: Click here to view references | |

Figure 3

2 ways to seek relationships between genes and behavior

Researchers use ‘forward’ and ‘reverse’ genetics to connect behavioral phenotypes with predisposing genotypes. Each approach must consider intermediary functional anatomic and physiologic levels (black box), as shown in this conceptual framework.

DA: dopamine; EEG: electroencephalography; 5-HT: serotonin; LTD: long-term depression; LTP: long-term potentiation; RNA: ribonucleic acid; SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms; VNTRs: variable number tandem (triplet) repeats

Clinical implications

Genomic research is increasing our understanding of alcohol’s pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions and of potential genetic associations with alcoholic phenotypes. These insights may lead to discovery of new therapies to compensate for specific physiologic and behavioral dysfunctions. For example, medications with pharmacologic profiles complimentary to addiction-related physiologic/behavioral deficits might be designed in the future.

Likewise, new understandings about genetic variability may allow us to predict an individual’s ability to tolerate and respond to existing medications used to treat alcohol dependence. For example, in studies of alcoholic and nonalcoholic subjects:

- Individuals with the 118G variant allele of the μ-opioid receptor may experience a stronger subjective response to alcohol and respond more robustly to naltrexone treatment than do carriers of the more common 118A allele.32

- Persons with a functional variation in the DRD4 gene (7 repeat allele–DRD4L) coding for type 4 dopamine receptor reported greater euphoria and reward while drinking alcohol and reduced alcohol consumption during 12-week treatment with olanzapine, a DRD2/DRD4 blocker.33

Applying this approach to the study of acamprosate has been difficult because of uncertainty about which protein molecules it targets. Variation in the Per2 gene (coding for protein involved in the circadian cycle) has been shown to be associated with brain glutamate levels, alcohol consumption, and the effects of acamprosate, although these interactions require further investigation.34

Pharmacogenomics of alcoholism treatment is in a very early stage of development. Findings require replication in different clinical samples and functional analysis. At the same time, if the reported association between the μ-opioid receptor genetic variation and naltrexone’s treatment efficacy is confirmed, this finding could help to guide clinical practice. Studies of genomic predictors of other medications’ efficacy and tolerability for alcoholism treatment would be expected to follow.

Related resources

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA). www.niaaa.nih.gov (search NIAAA-funded collaborative research programs).

- Dick DM, Jones K, Saccone N, et al. Endophenotypes successfully lead to gene identification: results from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Behav Genet 2006;36(1):112-26.

Drug brand names

- Acamprosate • Campral

- Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the S.C. Johnson Genomic of Addictions Program. The authors thank Ms. Barbara Hall for expert technical assistance in preparing this manuscript.

Children of alcoholics have a 40% to 60% increased risk of developing severe alcohol-related problems1—a harsh legacy recognized for >30 years. Now, as the result of rapidly growing evidence, we can explain in greater detail why alcoholism runs in families when discussing alcohol dependence with patients.

Individuals vary in response to medications and substances of abuse, and genetic research is revealing the heritable origins. Numerous genetic variations are known to influence response to alcohol, as well as alcoholism’s pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, and treatment. Pieces are still missing from this complex picture, but investigators are identifying possible risk factors for alcoholism and matching potential responders with treatments such as naltrexone and acamprosate.

This article provides a progress report on contemporary genetic research of alcoholism. Our goal is to inform your clinical practice by describing:

- new understandings of the genetics of alcoholism

- how researchers identify relationships between genetic variations and clinical/behavioral phenomena

- practical implications of this knowledge.

Genetic variations and risk of addiction

No single gene appears to cause alcoholism. Many genetic variations that accumulated during evolution likely contribute to individual differences in response to alcohol and susceptibility to developing alcohol-related problems. A growing number of genetic variations have been associated with increased alcohol tolerance, consumption, and other related phenotypes.

Like other addictive substances, alcohol triggers pharmacodynamic effects by interacting with a variety of molecular targets (Figure 1).2 These target proteins in turn interact with specific signaling proteins and trigger responses in complex functional pathways. Genetic variations may affect the structure of genes coding for proteins that constitute pathways involved in alcohol’s effects on target proteins (pharmacodynamics) or its metabolism (pharmacokinetics). If such variations alter the production, function, or stability of these proteins, the pathway’s function also may be altered and produce behavioral phenotypes—such as high or low sensitivity to alcohol’s effects.

Alcoholism-related phenotypes. DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria include some but not all of the multiple phenotypes within alcoholism’s clinical presentation. Researchers in the Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA)3 identified chromosome regions linked to alcoholism-related phenotypes, including:

- alcohol dependence4

- later age of drinking onset and increased harm avoidance5

- alcoholism and depression6

- alcohol sensitivity7

- alcohol consumption.8

To identify genes of interest within these chromosome regions, researchers used transitional phenotypes (endophenotypes) that “lie on the pathway between genes and disease,”9,10 and allowed them to characterize the neural systems affected by gene risk variants.11 As a result, they found associations among variations in the GABRA2 gene, (encoding the alpha-2 subunit of the GABAA receptor), specific brain oscillations (electrophysiologic endophenotype), and predisposition to alcohol dependence.12,13 By this same strategy, researchers discovered an association between the endophenotype (low-level of response to alcohol) and some genotypes, including at least 1 short allele of the serotonin transporter gene SLC6A4.14

Figure 1

Known molecular targets for alcohol and other drugs of abuse

Effects of drugs of abuse (black arrows) influence intracellular signaling pathways (blue arrows) to produce immediate and long-term changes in cell function.

cAMP: cyclic adenosine monophosphate; GABAA: gamma-aminobutyric acid A receptor; Gi, Gs, Gq: G proteins (heterotrimeric guanine nucleotide-binding proteins) MAPK: mitogen-activated protein kinase; N-cholino receptor: nicotinic cholinoreceptor; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; PKA: protein kinase A

Source: Created for CURRENT PSYCHIATRY from information in reference 2

Alcohol metabolism

Alcohol is metabolized to acetic acid through primary and auxiliary pathways involving alcohol and acetaldehyde dehydrogenases (ADH/ALDH) and the microsomal ethanol oxidizing system (cytochrome P-450 [CYP] 2E1)15 (Figure 2). Auxiliary pathways become involved when the primary pathway is overwhelmed by the amount of alcohol needed to be metabolized. Catalase and fatty acid ethyl ester synthases play a minor role under normal conditions but may be implicated in alcohol-induced organ damage.16

ADH/ALDH pathway. From one individual to another, the ability to metabolize ethyl alcohol varies up to 3- to 4-fold.17 In European and Amerindian samples, a genetic link has been identified between alcoholism and the 4q21-23 region on chromosome 4.18 This region contains a cluster of 7 genes encoding for alcohol dehydrogenases (ADH), including 3 Class I genes—ADH1A, ADH1B, and ADH1C—coding for the corresponding proteins that play a major role in alcohol metabolism.19 In eastern Asian samples, alleles encoding high activity enzymes (ADH1B*47His and ADH1C*349Ile) are significantly less frequent in alcoholics compared with nonalcoholic controls.20

Mitochondrial ALDH2 protein plays the central role in acetaldehyde metabolism and is highly expressed in the liver, stomach, and other tissues—including the brain.21 The ALDH2*2 gene variant encodes for a catalytically inactive enzyme, thus inhibiting acetaldehyde metabolism and causing a facial flushing reaction.22 The ALDH2*2 allele has a relatively high frequency in Asians but also is found in other populations.23 Meta-analyses of published data indicate that possessing either of the variant alleles in the ADH1B and ALDH2 genes is protective against alcohol dependence in Asians.24

The ADH4 enzyme catalyzes oxidation or reduction of numerous substrates—including long-chain aliphatic alcohols and aromatic aldehydes—and becomes involved in alcohol metabolism at moderate to high concentrations. The -75A allele of the ADH4 gene has promoter activity more than twice that of the -75C allele and significantly affects its expression.25 This substitution in the promoter region, as well as A/G SNP (rs1042364)—a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)—at exon 9, has been associated with an increased risk for alcohol and drug dependence in European Americans.26

Finally, variations in the ADH7 gene may play a protective role against alcoholism through epistatic effects.27

The CYP 2E1 pathway has low initial catalytic efficiency compared with the ADH/ALDH pathway, but it may metabolize alcohol up to 10 times faster after chronic alcohol consumption or cigarette smoking and accounts for metabolic tolerance.28 CYP 2E1 is involved in metabolizing both alcohol and acetaldehyde.29 The CYP 2E1*1D polymorphism has been associated with greater inducibility as well as alcohol and nicotine dependence.30

Thus, linkage and association studies support the association of phenotypes related to alcohol response and dependence with variations in genes that code for proteins involved in alcohol’s pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic effects. Each of these findings is important, but conceptual models organizing them all and explaining their role in alcohol’s effects and predisposition to alcoholism have yet to be constructed.

Figure 2

Genetic variations that affect alcohol metabolism pathways

Genetic variations affect the efficiency of primary and auxiliary pathways by which ethyl alcohol is metabolized to acetaldehyde and acetic acid. Auxiliary pathways become involved when the primary pathway is overwhelmed by the amount of alcohol to be metabolized.

ADH: alcohol dehydrogenase; ALDH: acetaldehyde dehydrogenase; P450CYP 2E1: cytochrome P450, family 2, subfamily E, polypeptide 1; A/G SNP: adenine/guanine single nucleotide polymorphism

Phenotype-genotype relationships

Alcohol—unlike most other addictive substances—does not have a specific receptor and is believed to act by disturbing the balance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmission in the neural system. Consequently, researchers explore relationships between genetics and alcohol-related problems using 2 approaches:

- Forward genetics (discovering disease-related genes via genome-wide studies and then studying their function; examples include linkage and genome-wide association studies [GWAS]).

- Reverse genetics (testing whether candidate genes and polymorphisms identified in animal studies as relevant for biological effects also exist in humans and are relevant to the phenotype).31

When searching for relationships between genotypes and phenotypes, both approaches must take into account a framework of functional anatomic and physiologic connections (Figure 3).

Linkage studies. The goal of linkage studies is to find a link between a phenotypic variation (ideally a measurable trait, such as number of drinks necessary for intoxication) and the chromosomal marker expected to be in the vicinity of the disease-specific gene variation. An advantage of linkage studies is that they can be started without knowing specific DNA sequences. Their limitations include:

- limited power when applied to complex diseases such as alcoholism

- they do not yield gene-specific information

- their success is highly dependent on family members’ willingness to participate.

Association studies. Candidate gene-based association studies are designed to directly test a potential association between the phenotype of interest and a known genomic sequence variation. This approach provides adequate power to study variations with modest effects and allows use of DNA from unrelated individuals. The candidate gene approach has revealed associations between specific genomic variations and phenotypes related to alcohol misuse and alcoholism (Table).

Like linkage studies, association studies have their own challenges and limitations, such as:

- historically high false-positive rates

- confounding risks (allele frequencies may vary because of ethnic stratification rather than disease predisposition).

To address these challenges, researchers must carefully choose behavioral, physiologic, or intermediate phenotypes and genotype variations, as well as control subjects and sample sizes. Replication studies are necessary to rule out false-positive associations. In fact, only some of the findings depicted in the Table—those related to GABRA2 and GABRA6 and few other genes—have been replicated.

Genome-wide association studies are a powerful new method for studying relationships between genomic variability and behavior. With GWAS, thousands of DNA samples can be scanned for thousands of SNPs throughout the human genome, with the goal of identifying variations that modestly increase the risk of developing common diseases.

Unlike the candidate gene approach—which focuses on preselected genomic variations—GWAS scans the whole genome and may identify unexpected susceptibility factors. Unlike the family-based linkage approach, GWAS is not limited to specific families and can address all recombination events in a population.

Challenges are associated with GWAS, however, and include:

- need for substantial numbers (2,000 to 5,000) of rigorously described cases and matched controls

- need for accurate, high-throughput genotyping technologies and sophisticated algorithms for analyzing data

- risk of high false-positive rates related to multiple testing

- inability to scan 100% of the genome, which may lead to false-negative findings.

Table

Examples of gene variations related to alcohol misuse and alcoholism phenotypes

| Phenotype | Gene variation(s) |

|---|---|

| Related to alcohol misuse | |

| Low response/high tolerance to alcohol | L allele of serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) and Ser385 allele of alpha-6 subunit of GABAA receptor gene (GABRA6) in adolescents and healthy adult men;a,b 600G allele of alpha-2 subunit of GABAA receptor gene (GABRA2) in healthy social drinkersc |

| Cue-related craving for alcohol | 118G allele of opioid μ-receptor gene (OMPR) and L allele of dopamine receptor type 4 gene (DRD4) in young problem drinkersd,e |

| Binge drinking | S allele of serotonin transporter gene in college students; combination of SS genotype of serotonin transporter gene and HH genotype of MAOA gene in young womenf |

| Related to alcoholism | |

| Alcohol dependence | Two common haplotypes of GABRA2 geneg |

| Liver cirrhosis in alcoholics | -238A allele of tumor necrosis factor gene (TNFA)h |

| Protects against withdrawal symptoms in alcoholics | -141C Del variant of the dopamine receptor type 2 gene (DRD2)i |

| Associated with delirium tremens | 8 genetic polymorphisms in 3 candidate genes involved in the dopamine transmission (DRD2, DRD3, and SLC6A3), 1 gene involved in the glutamate pathway (GRIK3), 1 neuropeptide gene (BDNF), and 1 cannabinoid gene (CNR1)j |

| Associated with alcohol withdrawal seizures | 9 repeat allele of dopamine transporter (SLC6A3); 10 repeat allele of tyrosine hydroxylase gene (TH); Ser9 allele of dopamine receptor type 3 gene (DRD3); SS genotype of serotonin transporter gene; 2108A allele in NR1 subunit of NMDA receptor gene (GRIN1)k-m |

| GABAA: gamma-aminobutyric acid A; MAOA: monoamine oxidase A; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate | |

| Source: Click here to view references | |

Figure 3

2 ways to seek relationships between genes and behavior

Researchers use ‘forward’ and ‘reverse’ genetics to connect behavioral phenotypes with predisposing genotypes. Each approach must consider intermediary functional anatomic and physiologic levels (black box), as shown in this conceptual framework.

DA: dopamine; EEG: electroencephalography; 5-HT: serotonin; LTD: long-term depression; LTP: long-term potentiation; RNA: ribonucleic acid; SNPs: single nucleotide polymorphisms; VNTRs: variable number tandem (triplet) repeats

Clinical implications

Genomic research is increasing our understanding of alcohol’s pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic interactions and of potential genetic associations with alcoholic phenotypes. These insights may lead to discovery of new therapies to compensate for specific physiologic and behavioral dysfunctions. For example, medications with pharmacologic profiles complimentary to addiction-related physiologic/behavioral deficits might be designed in the future.

Likewise, new understandings about genetic variability may allow us to predict an individual’s ability to tolerate and respond to existing medications used to treat alcohol dependence. For example, in studies of alcoholic and nonalcoholic subjects:

- Individuals with the 118G variant allele of the μ-opioid receptor may experience a stronger subjective response to alcohol and respond more robustly to naltrexone treatment than do carriers of the more common 118A allele.32

- Persons with a functional variation in the DRD4 gene (7 repeat allele–DRD4L) coding for type 4 dopamine receptor reported greater euphoria and reward while drinking alcohol and reduced alcohol consumption during 12-week treatment with olanzapine, a DRD2/DRD4 blocker.33

Applying this approach to the study of acamprosate has been difficult because of uncertainty about which protein molecules it targets. Variation in the Per2 gene (coding for protein involved in the circadian cycle) has been shown to be associated with brain glutamate levels, alcohol consumption, and the effects of acamprosate, although these interactions require further investigation.34

Pharmacogenomics of alcoholism treatment is in a very early stage of development. Findings require replication in different clinical samples and functional analysis. At the same time, if the reported association between the μ-opioid receptor genetic variation and naltrexone’s treatment efficacy is confirmed, this finding could help to guide clinical practice. Studies of genomic predictors of other medications’ efficacy and tolerability for alcoholism treatment would be expected to follow.

Related resources

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA). www.niaaa.nih.gov (search NIAAA-funded collaborative research programs).

- Dick DM, Jones K, Saccone N, et al. Endophenotypes successfully lead to gene identification: results from the Collaborative Study on the Genetics of Alcoholism. Behav Genet 2006;36(1):112-26.

Drug brand names

- Acamprosate • Campral

- Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Disclosure

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by the S.C. Johnson Genomic of Addictions Program. The authors thank Ms. Barbara Hall for expert technical assistance in preparing this manuscript.

1. Schuckit MA, Goodwin DA, Winokur G. A study of alcoholism in half siblings. Am J Psychiatry 1972;128(9):1132-6.

2. Nestler E. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 2001;2(2):119-28.

3. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA). Available at: http://zork.wustl.edu/niaaa. Accessed January 28, 2008.

4. Foroud T, Edenberg HJ, Goate A, et al. Alcoholism susceptibility loci: confirmation studies in a replicate sample and further mapping. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000;24(7):933-45.

5. Dick DM, Nurnberger J, Jr, Edenberg HJ, et al. Suggestive linkage on chromosome 1 for a quantitative alcohol-related phenotype. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2002;26(10):1453-60.

6. Nurnberger JI, Jr, Foroud T, Flury L, et al. Evidence for a locus on chromosome 1 that influences vulnerability to alcoholism and affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(5):718-24.

7. Schuckit MA, Edenberg HJ, Kalmijn J, et al. A genome-wide search for genes that relate to a low level of response to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25(3):323-9.

8. Saccone NL, Kwon JM, Corbett J, et al. A genome screen of maximum number of drinks as an alcoholism phenotype. Am J Med Genet 2000;96(5):632-7.

9. Gottesman II, Shields J. Schizophrenia and genetics;a twin study vantage point. New York, NY: Academic Press;1972.

10. Rieder RO, Gershon ES. Genetic strategies in biological psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978;35(7):866-73.

11. Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR. Intermediate phenotypes and genetic mechanisms of psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006;7(10):818-27.

12. Dick DM, Jones K, Saccone N, et al. Endophenotypes successfully lead to gene identification: results from the Collaborative Study on Genetics of Alcoholism. Behav Genet 2006;36(1):112-26.

13. Edenberg HJ, Dick DM, Xuei X, et al. Variations in GABRA2, encoding the alpha 2 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor, are associated with alcohol dependence and with brain oscillations. Am J Hum Genet 2004;74(4):705-14.

14. Hinckers AS, Laucht M, Schmidt MH, et al. Low level of response to alcohol as associated with serotonin transporter genotype and high alcohol intake in adolescents. Biol Psychiatry 2006;60(3):282-7.

15. Ramchandani VA, Bosron WF, Li TK. Research advances in ethanol metabolism. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2001;49(9):676-82.

16. Beckemeier ME, Bora PS. Fatty acid ethyl esters: potentially toxic products of myocardial ethanol metabolism. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1998;30(11):2487-94.

17. Li TK, Yin SJ, Crabb DW, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on alcohol metabolism in humans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25(1):136-44.

18. Long JC, Knowler WC, Hanson RL, et al. Evidence for genetic linkage to alcohol dependence on chromosomes 4 and 11 from an autosome-wide scan in an American Indian population. Am J Med Genet 1998;81(3):216-21.

19. Edenberg HJ. Regulation of the mammalian alcohol dehydrogenase genes. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 2000;64:295-341.

20. Osier M, Pakstis A, Soodyall H, et al. A global perspective on genetic variation at the ADH genes reveals unusual patterns of linkage disequilibrium and diversity. Am J Hum Genet 2002;71(1):84-99.

21. Yoshida A, Rzhetsky A, Hsu LC, Chang C. Human aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family. Eur J Biochem 1998;251(3):549-57.

22. Harada S, Agarwal DP, Goedde HW. Aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency as a cause of facial flashing reaction to alcohol in Japanese. Lancet 1981;2(8253):982.-

23. Goedde HW, Agarwal DP, Fritze G, et al. Distribution of ADH2 and ALDH2 genotypes in different populations. Hum Genet 1992;88(3):344-6.

24. Luczak SE, Glatt SJ, Wall TJ. Meta-analyses of ALDH2 and ADH1B with alcohol dependence in Asians. Psychol Bull 2006;132(4):607-21.

25. Edenberg HJ, Jerome RE, Li M. Polymorphism of the human alcohol dehydrogenase 4 (ADH4) promoter affects gene expression. Pharmacogenetics 1999;9(1):25-30.

26. Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, et al. ADH4 gene variation is associated with alcohol dependence and drug dependence in European Americans: results from HWD tests and case-control association studies. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31(5):1085-95.

27. Osier MV, Lu RB, Pakstis AJ, et al. Possible epistatic role of ADH7 in the protection against alcoholism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2004;126(1):19-22.

28. Lieber CS. Microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system (MEOS): the first 30 years (1968-1998)—a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999;23(6):991-1007.

29. Kunitoh S, Imaoka S, Hiroi T, et al. Acetaldehyde as well as ethanol is metabolized by human CYP2E1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997;280(2):527-32.

30. Howard LA, Ahluwalia JS, Lin SK, et al. CYP2E1*1D regulatory polymorphism: association with alcohol and nicotine dependence [erratum in Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(7):441-2]. Pharmacogenetics 2003;13(6):321-8.

31. Risch NJ. Searching for genetic determinants in the new millennium. Nature 2000;405(6788):847-56.

32. Oslin DW, Berrettini W, Kranzler HR, et al. A functional polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor gene is associated with naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003;28:1546-52.

33. Hutchison KE, Ray L, Sandman E, et al. The effect of olanzapine on craving and alcohol consumption. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31(6):1310-7.

34. Spanagel R, Pendyala G, Abarca C, et al. The clock gene Per2 influences the glutamatergic system and modulates alcohol consumption. Nat Med 2005;11(1):35-42.

1. Schuckit MA, Goodwin DA, Winokur G. A study of alcoholism in half siblings. Am J Psychiatry 1972;128(9):1132-6.

2. Nestler E. Molecular basis of long-term plasticity underlying addiction. Nat Rev Neurosci 2001;2(2):119-28.

3. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA). Available at: http://zork.wustl.edu/niaaa. Accessed January 28, 2008.

4. Foroud T, Edenberg HJ, Goate A, et al. Alcoholism susceptibility loci: confirmation studies in a replicate sample and further mapping. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2000;24(7):933-45.

5. Dick DM, Nurnberger J, Jr, Edenberg HJ, et al. Suggestive linkage on chromosome 1 for a quantitative alcohol-related phenotype. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2002;26(10):1453-60.

6. Nurnberger JI, Jr, Foroud T, Flury L, et al. Evidence for a locus on chromosome 1 that influences vulnerability to alcoholism and affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158(5):718-24.

7. Schuckit MA, Edenberg HJ, Kalmijn J, et al. A genome-wide search for genes that relate to a low level of response to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25(3):323-9.

8. Saccone NL, Kwon JM, Corbett J, et al. A genome screen of maximum number of drinks as an alcoholism phenotype. Am J Med Genet 2000;96(5):632-7.

9. Gottesman II, Shields J. Schizophrenia and genetics;a twin study vantage point. New York, NY: Academic Press;1972.

10. Rieder RO, Gershon ES. Genetic strategies in biological psychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978;35(7):866-73.

11. Meyer-Lindenberg A, Weinberger DR. Intermediate phenotypes and genetic mechanisms of psychiatric disorders. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006;7(10):818-27.

12. Dick DM, Jones K, Saccone N, et al. Endophenotypes successfully lead to gene identification: results from the Collaborative Study on Genetics of Alcoholism. Behav Genet 2006;36(1):112-26.

13. Edenberg HJ, Dick DM, Xuei X, et al. Variations in GABRA2, encoding the alpha 2 subunit of the GABA(A) receptor, are associated with alcohol dependence and with brain oscillations. Am J Hum Genet 2004;74(4):705-14.

14. Hinckers AS, Laucht M, Schmidt MH, et al. Low level of response to alcohol as associated with serotonin transporter genotype and high alcohol intake in adolescents. Biol Psychiatry 2006;60(3):282-7.

15. Ramchandani VA, Bosron WF, Li TK. Research advances in ethanol metabolism. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2001;49(9):676-82.

16. Beckemeier ME, Bora PS. Fatty acid ethyl esters: potentially toxic products of myocardial ethanol metabolism. J Mol Cell Cardiol 1998;30(11):2487-94.

17. Li TK, Yin SJ, Crabb DW, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on alcohol metabolism in humans. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 2001;25(1):136-44.

18. Long JC, Knowler WC, Hanson RL, et al. Evidence for genetic linkage to alcohol dependence on chromosomes 4 and 11 from an autosome-wide scan in an American Indian population. Am J Med Genet 1998;81(3):216-21.

19. Edenberg HJ. Regulation of the mammalian alcohol dehydrogenase genes. Prog Nucleic Acid Res Mol Biol 2000;64:295-341.

20. Osier M, Pakstis A, Soodyall H, et al. A global perspective on genetic variation at the ADH genes reveals unusual patterns of linkage disequilibrium and diversity. Am J Hum Genet 2002;71(1):84-99.

21. Yoshida A, Rzhetsky A, Hsu LC, Chang C. Human aldehyde dehydrogenase gene family. Eur J Biochem 1998;251(3):549-57.

22. Harada S, Agarwal DP, Goedde HW. Aldehyde dehydrogenase deficiency as a cause of facial flashing reaction to alcohol in Japanese. Lancet 1981;2(8253):982.-

23. Goedde HW, Agarwal DP, Fritze G, et al. Distribution of ADH2 and ALDH2 genotypes in different populations. Hum Genet 1992;88(3):344-6.

24. Luczak SE, Glatt SJ, Wall TJ. Meta-analyses of ALDH2 and ADH1B with alcohol dependence in Asians. Psychol Bull 2006;132(4):607-21.

25. Edenberg HJ, Jerome RE, Li M. Polymorphism of the human alcohol dehydrogenase 4 (ADH4) promoter affects gene expression. Pharmacogenetics 1999;9(1):25-30.

26. Luo X, Kranzler HR, Zuo L, et al. ADH4 gene variation is associated with alcohol dependence and drug dependence in European Americans: results from HWD tests and case-control association studies. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31(5):1085-95.

27. Osier MV, Lu RB, Pakstis AJ, et al. Possible epistatic role of ADH7 in the protection against alcoholism. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet 2004;126(1):19-22.

28. Lieber CS. Microsomal ethanol-oxidizing system (MEOS): the first 30 years (1968-1998)—a review. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 1999;23(6):991-1007.

29. Kunitoh S, Imaoka S, Hiroi T, et al. Acetaldehyde as well as ethanol is metabolized by human CYP2E1. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 1997;280(2):527-32.

30. Howard LA, Ahluwalia JS, Lin SK, et al. CYP2E1*1D regulatory polymorphism: association with alcohol and nicotine dependence [erratum in Pharmacogenetics. 2003;13(7):441-2]. Pharmacogenetics 2003;13(6):321-8.

31. Risch NJ. Searching for genetic determinants in the new millennium. Nature 2000;405(6788):847-56.

32. Oslin DW, Berrettini W, Kranzler HR, et al. A functional polymorphism of the mu-opioid receptor gene is associated with naltrexone response in alcohol-dependent patients. Neuropsychopharmacology 2003;28:1546-52.

33. Hutchison KE, Ray L, Sandman E, et al. The effect of olanzapine on craving and alcohol consumption. Neuropsychopharmacology 2006;31(6):1310-7.

34. Spanagel R, Pendyala G, Abarca C, et al. The clock gene Per2 influences the glutamatergic system and modulates alcohol consumption. Nat Med 2005;11(1):35-42.

Practice, not malpractice: 3 clinical habits to reduce liability risk

Psychiatrists’ risk of malpractice liability1 is broadening as courts consider the uncertainties of off-label prescribing, telemedicine, and confidentiality. Juries are holding mental health practitioners responsible for harm done both to and by psychiatric patients.

How you keep medical records, communicate with patients and colleagues, and arrange consultations can reduce your malpractice risk (Box 1).4-9 We offer recommendations based on court decisions and other evidence for managing:

- traditional risks—such as patient violence and suicide, adverse drug reactions, sex with patients, faulty termination of treatment, and supervisory and consultative relationships4

- newer risks—such as recovered memory, off-label prescribing, practice guidelines, and e-mail and confidentiality.

1. Keep thorough medical records

The most powerful defense against a malpractice suit is a well-documented chart. It can often prevent a malpractice suit by providing evidence that the physician adequately evaluated the available information and made good-faith efforts with his or her best judgment. Juries are typically forgiving of mistakes made in this context.4,5

Write legibly, and sign and date all entries. Try to think out loud in the chart. By outlining your thoughts about differential diagnosis, risks and benefits, and treatment options, you can help a jury understand your decision-making process and show that you carefully evaluated the situation. When documenting difficult cases, for example, imagine a plaintiff’s attorney reading your notes to a jury.6

2. Communicate freely with patients

Careful interaction with patients and their families can also prevent lawsuits. Communicating includes preparing patients for what to expect during treatment sessions, encouraging feedback, and even using humor.7 Freely sharing treatment information with patients can build a sense of mutual decision-making and responsibility.8 Acknowledging treatment limitations and deflating unrealistic expectations can also protect you.

Patients who file malpractice suits are often seeking an apology or expression of regret from their physicians. It is appropriate and prudent to admit and apologize for minor errors. It is also appropriate to express condolence over what both sides agree is a severe, negative outcome.9 Expressing sympathy is not equivalent to admitting wrongdoing.

3. Seek consultation as needed

Discussing difficult or ambiguous cases with peers, supervisors, or legal staff can help shield you from liability. For example:

- Second opinions may help you make difficult clinical decisions.

- Peers and supervisors may provide useful suggestions to improve patient care.

- Legal staff can give advice regarding liability.

The fact that you sought consultation can be used in court as evidence against negligence, as it shows you tried to ensure appropriate care for your patient.9

This article describes general guidelines and is not intended to constitute legal advice. All practitioners have a responsibility to know the laws of the jurisdictions in which they practice.

PREVENTING PATIENT VIOLENCE

The case that opened Pandora’s box. Prosenjit Poddar, a student at the University of California at Berkeley, was infatuated with coed Tanya Tarasoff and told his psychologist he intended to kill her. The psychologist notified his psychiatric supervisor and called campus police.

The psychologist told police Poddar was dangerous to himself and others. He stated that he would sign an emergency hold if they would bring Poddar to the hospital.

The police apprehended Poddar but released him. Poddar dropped out of therapy and 2 months later fatally stabbed Ms. Tarasoff.

Ms. Tarasoff’s parents sued those who treated Poddar and the University of California.2 After a complicated legal course, the California Supreme Court ruled that once a therapist determines—or should have determined—that a patient poses a serious danger of violence to others, “he bears a duty to exercise reasonable care to protect the foreseeable victim of that danger.”3

The 1976 Tarasoff ruling has become a national standard of practice, leading to numerous other patient violence lawsuits. In these cases, psychiatrists are most likely to be found liable when recently released inpatients commit violent acts, particularly if the physician had reason to know the patient was dangerous and failed to take adequate precautions or appropriately assess the patient.4

Wider interpretations. Cases in several states have extended the Tarasoff ruling. In at least two cases, this standard has been applied when the patient threatened no specific victim before committing violence:

- A New Jersey court (McIntosh v. Milano, 1979) found a psychiatrist liable for malpractice on grounds that a therapist has a duty to protect society, just as a doctor must protect society by reporting carriers of dangerous diseases.

- A Nebraska court (Lipari v. Sears, Roebuck, and Co., 1980) held that physicians have a duty to protect—even if the specific identity of victims is unknown—so long as the physician should know that the patient presents an unreasonable risk of harm to others.2

Auto accidents. Tarasoff liability also has been extended to auto accidents. In Washington state (Petersen v. Washington, 1983), a psychiatrist was held liable for injuries to victims of an accident caused by a psychiatric patient. The court ruled that the psychiatrist had a duty to take reasonable precautions to protect any foreseeable persons from being endangered by the patient.

In a similar case in Wisconsin (Schuster and Schuster v. Altenberg, et al., 1988), the court ruled that damages could be awarded to anyone whose harm could have been prevented had the physician practiced according to professional standards.2

Other extensions include cases such as Naidu v. Laird, 1988, in which patient violence occurred more than 5 months after hospitalization.2 Vermont has extended the Tarasoff precedent to property destruction by psychiatric patients.10

Recommendation. Most states require a psychiatrist to protect against only specific threats to identifiable victims.10 To defend yourself against a Tarasoff-type suit, you must show that you:

- carefully assessed the patient’s risk for violence

- provided appropriate care

- and took appropriate precautions.

The most protective evidence is a medical record documenting that you thoroughly assessed a patient for risk of violence (Table).4,11

If you are unsure about how to manage a patient you believe may be dangerous to himself or others, consult with supervisors, peers, and legal advisors. Many states have Tarasoff-like statutes that specify the conditions that require action and the appropriate actions.

In states without specific statutes, options that generally satisfy Tarasoff requirements include hospitalizing the patient, notifying authorities, and/or warning the potential victim.10 As the Tarasoff case demonstrated, notifying authorities may not substitute for warning or hospitalizing.2

SUICIDE RISK? DOCUMENT CAREFULLY

Patient suicide accounts for one-fifth of claims covered by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) insurance plan.

In court, key points of challenge to a physician’s judgment in a suicide case include the admission evaluation and any status changes. Thorough risk assessment includes carefully reviewing existing records, evaluating risk factors for suicide, and seeking advice from colleagues or supervisors when appropriate.4

Recommendation. Document for every inpatient admission, discharge, or status change that the patient’s risk for suicide was assessed. List risk factors, protective factors, and risk for self-harm.

Explicitly address in the patient’s chart any comments about suicidality (such as heard by nursing staff).9 Document your rationale for medical decisions and orders, consistently follow unit policies, and explain risks and benefits of hospitalization to patients and their families.

Before discharge, schedule appropriate follow-up and make reasonable efforts to ensure medication adherence.4

SEX WITH PATIENTS IS UNPROTECTED

Sexual involvement with patients is indefensible and uncontestable in malpractice cases. Even so, up to 9% of male therapists and 3% of female therapists report in surveys that they have had sexual interaction with their patients.4

In 1985 the APA excluded sex with patients from its malpractice insurance coverage. Courts generally consider a treatment to be within the standard of care if a respectable minority of physicians consider it to be appropriate. Sex with patients is considered an absolute deviation from the standard of care, and no respectable minority of practitioners supports this practice. Because patients are substantially harmed, sex with patients is considered prima facie malpractice.12

Table

Is this patient dangerous? Risk factors for violence

| Psychiatric |

|

| Demographic |

|

| Socioeconomic |

|

WHEN MEDICATIONS CAUSE HARM

Adverse drug reactions—particularly tardive dyskinesia (TD)—are a source of significant losses in malpractice cases. Multimillion-dollar awards have been granted, especially when neuroleptic antipsychotics have been given in excessive dosages without proper monitoring.13

Informed consent has been a particularly difficult issue with the use of neuroleptic medications. Many doctors worry that patients who fear developing TD will not take prescribed neuroleptics. A study of North Carolina psychiatrists in the 1980s revealed that only 30% mentioned TD when telling their patients about neuroleptics’ possible side effects.13

The fact that a patient develops TD while taking an antipsychotic does not establish grounds for malpractice; a valid malpractice suit must also establish negligence. Negligence could include failing to obtain appropriate informed consent or continuing to prescribe an antipsychotic without adequately examining the patient.4

Informed consent does not require a patient to fully understand everything about a medication. The patient must understand the information a reasonable patient would want to know. Obvious misunderstandings must be corrected.

Recommendation. Consider informed consent a process, rather than one event—especially when you give neuroleptics for acute psychotic episodes. You can establish, review, and refresh consent in follow-up visits as medications help patients become more coherent and organized.