User login

Enhancing the Communication Skills of Critical Care Nurses: Focus on Prognosis and Goals of Care Discussions

From the University of California Irvine Health/Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Orange, CA (Ms. Boyle) and the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, San Francisco, CA (Dr. Anderson).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe components of a unique interactive workshop focusing on the enhancement of critical care nurses’ communication skills within the realm of prognosis and goals of care discussions with family members and physicians.

- Methods: A series of one-day workshops were offered to critical care nurses practicing in the 5 University of California hospital settings. After workshop attendance, nurse participants were followed by workshop facilitators in their units to ensure new communication skills were being integrated into practice and to problem solve if barriers were met.

- Results: Improvement in nurses’ self-confidence in engaging in these discussions was seen. This confidence was sustained months following workshop participation.

- Conclusion: The combination of critical care nurse workshop participation that involved skill enhancement through role-playing, in combination with clinical follow-up with attendees, resulted in positive affirmation of nurse communication skills specific to prognosis and goals of care discussions with family members and physicians.

There is increasing evidence that in the absence of quality communication between professional caregivers and those they care for, negative outcomes may prevail, such as reduced patient/family satisfaction, lower health status awareness, and a decreased sense of being cared about and cared for [1–5]. Communication skill competency is a critical corollary of nursing practice. In the intensive care unit (ICU) setting, patients and families have cited skilled communication as a core element of high-quality care [3,6]. Proficiency in this realm enhances nurses’ understanding of the patient and family’s encounter with health care and provides a vehicle to gather information, inform, teach, and offer emotional support. Additionally, it identifies values, goals, health care preferences, worries and concerns, and facilitates the nurses’ coordination of care [7]. Despite this skill’s importance, however, it is generally not taught in basic education and until recently has been overlooked as a key competency [8,9].

Skilled communication in palliative and end-of-life care is pivotal for discussing prognosis and care planning. In the acute care setting this is particularly relevant as the majority of Americans die in hospitals versus their preferred site of home [10]. Additionally, 1 in 5 Americans die during or shortly after receiving care in an ICU [11]. Hence, while the ICU is a setting in which intensive effort to save lives is employed, it is also a setting where death frequently occurs. The complexity and highly emotive nature of critical care often results in family needs for information and support not being met [12]. A number of reasons for this occurrence have been proposed. In this paper, we will delineate barriers to critical care nurses’ involvement in prognosis and goals of care discussions, identify why nurse involvement in this communication is needed, describe a unique workshop exemplar with a sample role play that characterizes the workshop, and offer recommendations for colleagues interested in replicating similar education offerings.

Barriers to Communication

In the ICU, the sheer number of professionals families interact with may cause confusion. In particular, numerous medical consultants commonly offer opposing opinions. Additionally, each specialist may provide information that focuses on their area of expertise such that the “big picture” is not relayed to the patient and family. Emotional discomfort on the part of the health professional around discussions of poor prognosis, goals of care, and code status may prompt limiting discussion time with patients and families and even the avoidance of interpersonal exchanges [13–15]. Health professionals have also reported concern that end-of-life discussions will increase patient distress [16]. Among health care professionals, the subject of mortality may prompt personal anxiety, trigger unresolved grief, or fear that they will “become emotional” in front of the patient/family [7]. Lack of knowledge about cultural and religious norms has been cited as a barrier, as has time constraints [17,18]. Most frequently, inadequate or absent communication skill training is noted as a significant barrier [19,20]. Many ICU nurses also report feeling marginalized due their exclusion from goals of care and decision-making discussions with patients and families they know well [21,22].

Nurses As Key Palliative Care Communicators

Education efforts that foster communication proficiency during serious illness have traditionally focused on training physicians. Recently, nursing has become a focus of communication skill enhancement in recognition of nurses’ intense and protracted interactions with patients and families in the acute care setting. Nurses are the ‘constant’ in the patient and family’s journey through the fragmented health care system [21,23]. They often have the best knowledge of, and strongest relationship with, the family and often have had extensive discussions with them about their loved one’s status [24]. Nurses are aware of the patients’ symptom experiences and are privy to valuable information about the concerns and priorities of patients and families [12]. Additionally, having the most continuous presence, nurses have seen and heard interactions with clinicians from numerous disciplines. Nurses are the most visible, constant resource for patient and family education, information and support, and thus they perceive one of their most important roles to be that of advocate for the patient and family [20,21].

Communication Training Programs for Critical Care Nurses

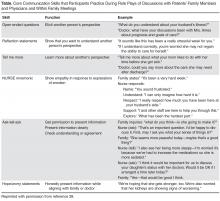

Education is critical to enhance communication skills within palliative care [7,15,17,20,21,24]. The preferred teaching style within this realm is role play, where skills can be practiced and the affective component of engaging in sensitive discussions can be addressed [25–27]. Role play also demonstrates firsthand the importance of nonverbal communication (eg, body language, proximity, use of gestures, tone of voice) [7,20] and facilitates nurses’ gaining a sense of comfort with wordless communication [18].

Communication skills training programs have been designed to provide bedside critical care nurses with the tools they need to be active participants in discussions of prognosis, goals of care, and palliative care with families and physicians [27,28]. These programs have demonstrated improvement in nurses’ confidence to engage in key palliative care-related discussions. Essential elements of these programs include (1) delineation of the role of the bedside nurse in palliative care communication; (2) presentation and learner-centered practice of communication skills using role play; and (3) a reflection session focused on self-care and sustainability.

Across the 5 academic University of California medical centers (San Francisco, Davis, Los Angeles, Irvine, and San Diego), a communication training program based on this work has been implemented [29]. The one-day workshop, entitled IMPACT-ICU (Integrating Multidisciplinary Palliative Care into the ICU), has taught a total of 527 critical care nurses across the 5 centers. In addition to classroom training, the IMPACT-ICU program also includes proactive specialty palliative nursing support for bedside nurses by facilitating the availability of palliative care advanced practice nurses and nurse educators resources. This support helps nurses to apply the skills learned in the workshop in their practice. During rounds at the bedside, the nurse resources coach the bedside staff on the “how” and “when” of addressing palliative care needs. Education and support on a range of topics are offered, including clarifying goals and interventions provided by palliative care teams, the specifics of how to provide family emotional support and delivery of understandable information, the assessment and management of symptoms distress, and the nurses’ role in organizing and participating in family meetings. Case-specific consultations are also offered that address how to interface with resistant medical staff. The importance of nurse documentation of these varied exchanges is also emphasized.

IMPACT-ICU Workshop

A maximum of 15 nurses participate in each 8-hour workshop. The session begins with introductions and small group discussions about what the participants perceive to be the greatest barriers to goals of care discussions and fostering patient/family decision-making in the ICU. Participants are also asked to reflect on what they want to learn as a result of their workshop attendance.

A short didactic session then reviews the definition of palliative care and its core components, addresses the nurses’ role in communication within palliative care, a social worker’s perspective of what it is like to be a family member in the ICU, and the outline of the day. This includes delineation of expectations for involvement within the role plays and the various roles to be enacted. An emphasis is placed on the workshop being a safe place to explore and trial skills with the support of colleagues, and that practice is the optimum way to integrate communication expertise into the nurses’ skill set.

The “4 Cs” serves as the instructional basis for nurse communication skill enhancement [27]. This model outlines 4 key nursing roles in optimizing communication within palliative care:

Convening: Making sure multidisciplinary patient/family/clinician communication occurs.

Checking: Identifying the patient and family needs for information; ensuring that patients and families clearly receive desired information; ensuring that clinicians understand patient and family perspectives.

Caring: Naming emotions and responding to feeling.

Continuing: Following up after discussions to clarify and reinforce information and provide support.

Sample Role Play

Facilitator: So our first role play is focused on eliciting patient and family perspectives and needs. I need a learner and someone to play the role of the family member.

Learner: I’ll give it a try.

Facilitator: Lisa, you’re going to do great. Who wants to play the family member?

Workshop Participant: I’ll do it.

Facilitator: So Mary (who has agreed to play the role of the wife), why don’t you read us the scenario. (She reads it out loud to the group).

Facilitator: Lisa, as the nurse, I want you to look at your guide and tell me what your goal is for this conversation with Mrs. Ames and then which skill you want to practice.

Learner: I think I want to try eliciting the patient and family’s needs for information and I’ll try “Tell Me More” statements.

Facilitator: Alright. So remember Lisa, if you feel the conversation isn’t going well, you can call a “time out.” I can do this as well if I feel you need to start over. I’ll also call a time out when I feel you have met your goal. Sound OK? Mary, do you have any questions playing the part of Mrs. Ames?

Wife Role: Well, how hard should I make this for her? Should I be one of those “difficult” family members?

Facilitator: Our goal here is not to “stump” you or make it particularly difficult. We want you to try out these skills and get a sense of your “comfort zone.” So let’s start with some basic communication skills, OK?

Wife Role: Alright.

Facilitator: Why don’t we set the stage, such that Lisa, you are Mr. Ames’ nurse assessing him at the start of your shift, when Mrs. Ames enters. This is the first time you have taken care of him. The night nurse has told you that he has been requiring increasing ventilator support and his renal function is declining. Per Mrs. Ames’ request, the night nurse called her to let her know how he was doing and Mrs. Ames told her she would be in shortly.

Wife Role: (nervously enters the room and grasps her husband’s hand and looks at the nurse). How’s he doing? Is he better? The night nurse called me and I was so worried I rushed over here.

Learner: (Turns to Mrs. Ames and extends her hand). Are you Mrs. Ames? I’m Lisa and I am going to be taking care of Mr. Ames today. Let me just finish my assessment and how about we talk then? Will that be OK? It will be just a few minutes.

Wife Role: Alright, I’ll be in the waiting area but please come get me as soon as you can.

Learner: I will. (Nurse then shortly comes into the waiting area and asks Mrs. Ames to come back into the ICU where she invites her to sit just outside Mr. Ames’ room). Mrs. Ames, how are you doing? This must be so stressful for you, having your husband in the ICU.

Wife Role: It’s awful. He’s never been in the hospital before this and look at him, all hooked up to machines. I’m so worried. He seems to be getting worse instead of better.

Learner: What’s your understanding of what is going on?

Wife Role: I really don’t know. One doctor comes in and says one thing and then another comes in and tells me the opposite. I’m so confused I don’t know what to think.

Learner: Would having a better idea of his condition from the doctors who are treating him help you have a better understanding?

Wife Role: Oh, yes, but they always seem in such a hurry.

Learner: What exactly would you like to know?

Wife: Well, I want to know when he can get off that breathing machine because we have been planning to go to our son’s house for Thanksgiving.

Facilitator: Time out. Lisa, did you meet your conversation goal?

Learner: Um, I’m not sure, I guess so.

Facilitator: (Turns to Observers). What do you think, did she meet her goal?

Observer: Yes, she determined Mrs. Ames’ need for more information and she asked her what she wanted to know exactly.

Facilitator: What else did we see Lisa do to enhance communication with Mrs. Ames?

Observer: Well, when Mrs. Ames rushed into the room and asked her for information, Lisa didn’t just jump in and spout out values for the ventilator and his output. She took the time to introduce herself and de-escalate Mrs. Ames’ anxiety and she followed up on her promise to come get her in the waiting room as soon as she could.

Facilitator: Why do you think was important?

Observer: It helps establish trust.

Facilitator: Did Lisa use the skill she wanted to try out?

Observer: Yes.

Facilitator: How do you know? What did you hear her say?

Observer: She said, “What’s your understanding of what is going on with Mr. Ames?”

Facilitator: Absolutely. Great job, Lisa. And who wants to take a guess at how long Lisa’s exchange with Mrs. Ames took?

Observer: Less than two minutes?

Facilitator: That’s right. So just as you consider how long it takes, and how proficient you are, in starting an IV or inserting a Foley catheter, when you have a goal in mind and have practiced the skills to do it well, any skill can be mastered.

Feedback

Participants in the workshops uniformly report an enhanced sense of self-confidence in their palliative care communication skills as a result of their participation [29]. Key to the success of the workshop is the ongoing contact by the workshop facilitators with participants. Rounding is routinely planned such that each participant is visited weekly by a workshop facilitator in their clinical area to determine if the bedside nurse has practiced the new skills and if so, how the interaction transpired. Positive feedback is given for attempts to engage in new behaviors and participants are reminded that with any new skill, repetitive trials are necessary to foster success.

Lessons Learned and Next Steps

One of our major lessons learned was recognizing that it was difficult for many critical care nurses to practice the new communication skills. Nurses are trained to fix problems and perform medico-technical tasks; “listening” has not always been recognized as real work [18]. We needed to reinforce that skills like eliciting another’s perspective or making reflection statements are equally important to those associated with behavioral/technical proficiency.

While our program has been successful, we recognize that the next step in fostering ideal palliative care communication is to provide education within an interdisciplinary context. We recommend that colleagues interested in replicating this or a similar education intervention, survey nurse participants prior to and following workshop participation to measure attitudes, self confidence and perceived barriers over time [30]. We hope to translate our positive experience into a program that engages multiple professionals in the enhancement of optimum palliative care communication proficiency.

Corresponding author: Deborah A. Boyle MSN, RN, AOCNS, Department of Nursing Quality, Research and Education, University of California, Irvine Health, 101 The City Drive, Bldg 22A, Room 3104, Orange, CA 92868.

1. Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, et al. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest 2012;142:128–33.

2. Osborn TR, Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, et al. Identifying elements of ICU care that families report as important but unsatisfactory: decision-making, control and ICU atmosphere. Chest 2012;142:1185–92.

3. Nelson JE, Puntillo K, Pronovost PJ, et al. In their own words: patients and families define high-quality palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2010;38:808–18.

4. Nels W, Gabrijel S, Kiss S, et al. Communication skill training significantly improves lung cancer patients understanding. J Palliat Care Med 2014;4:182.

5. Van Vliet LM, Epstein AS. Current state of the art and science of patient-clinician communication in progressive disease: patients’ need to know and feel known. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3474-8.

6. Troug RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end of life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 2008;36:953–63.

7. Dahlin CM, Wittenberg E. Communication in palliative care. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice J, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014:81–109.

8. Baer L, Weinstein E. Improving oncology nurses’ communication skills for difficult conversations. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2013;17:E45–E51.

9. Treece PD. Communication in the intensive care unit about end of life care. AACN Adv Crit Care 2007;18:406–14.

10. Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end of life care at the last place of care. JAMA 2004;291:88–92.

11. Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICU End-of-Life Peer Group. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med 2004;32:638–43.

12. Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med 2007;35:422–9.

13. Back AL, Trinidad SB, Hopley EK, Edwards KA. Reframing the goals of care conversation: “We’re in a different place.” J Palliat Med 2014;17:1010–24.

14. Aslakson RA, Wyskiel R, Thornton I, et al. Nurse perceived barriers to effective communication regarding prognosis and optimal end of life care for surgical ICU patients: a qualitative exploration. J Palliat Med 2012;15:910–5.

15. Erickson J. Bedside nurse involvement in end of life decision-making. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2013;32:65–8.

16. Bernacki RE, Block SD for the American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003.

17. You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al. Barriers to goals of care discussion with ‘seriously’ ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:549–56.

18. Strang S, Henoch I, Danielson E, et al. Communication about existential issues with patients close to death: nurses’ reflections on content, process, and meaning. Psychooncology 2014;23:562–8.

19. Slatore CG, Hensen L, Gauzine L, et al. Communication by nurses in the intensive care unit: qualitative analysis of domains in patient-centered care. Am J Crit Care 2012;21:410–8.

20. Wittenberg-Lyles E, Goldsmith J, Platt CS. Palliative care communication. Sem Oncol Nurs 2014;30:280–6.

21. Fox MY. Improving communication with patients and families in the ICU: palliative care strategies for intensive care unit nurses. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2014;16:93–8.

22. Beckstrand RL, Callister LC, Kirchhoff KT. Providing a ‘good death’: critical care nurses’ suggestions for improving end of life care. Am J Crit Care 2006;15:38–45.

23. Peereboom K, Coyle N. Facilitating goals of care discus.sions for patients with life-limiting disease: communication strategies for nurses. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2012; 14:251–8.

24. Nelson JE, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, et al. Integrating palliative care in the ICU: the nurse in the leading role. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2011;13:89–94.

25. Jors K, Seibel K, Bardenheuer H, et al. Education in end of life care: what do experienced professionals find important? J Cancer Educ 2015 March 15.

26. Roze des Ordons AL, Sharma N, Heyland DK, et al. Strategies for effective goals of care discussions and decision-making: perspective from a multi-centre survey of Canadian hospital-based health care providers. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:38.

27. Krimshtein NS, Luhrs CA, Puntillo KA, et al. Training nurses for interdisciplinary communication with families in the ICU. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1325–32.

28. Milic MM, Puntillo K, Turner K, et al. Communicating with patients’ families and physicians about prognosis and goals of care. Am J Crit Care 2015;24:e56–e64.

29. Anderson W, Puntillo K, Barbour S, et al. The IMPACT-ICU Project: expanding palliative care nursing across University of California Centers ICUs to advance palliative care. Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) national seminar. Nov 7–9, 2013. Dallas, TX.

30. Anderson WG, Puntillo K, Boyle D, et al. ICU bedside nurses’ involvement in palliative care communication: a multicenter survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. In press.

From the University of California Irvine Health/Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Orange, CA (Ms. Boyle) and the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, San Francisco, CA (Dr. Anderson).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe components of a unique interactive workshop focusing on the enhancement of critical care nurses’ communication skills within the realm of prognosis and goals of care discussions with family members and physicians.

- Methods: A series of one-day workshops were offered to critical care nurses practicing in the 5 University of California hospital settings. After workshop attendance, nurse participants were followed by workshop facilitators in their units to ensure new communication skills were being integrated into practice and to problem solve if barriers were met.

- Results: Improvement in nurses’ self-confidence in engaging in these discussions was seen. This confidence was sustained months following workshop participation.

- Conclusion: The combination of critical care nurse workshop participation that involved skill enhancement through role-playing, in combination with clinical follow-up with attendees, resulted in positive affirmation of nurse communication skills specific to prognosis and goals of care discussions with family members and physicians.

There is increasing evidence that in the absence of quality communication between professional caregivers and those they care for, negative outcomes may prevail, such as reduced patient/family satisfaction, lower health status awareness, and a decreased sense of being cared about and cared for [1–5]. Communication skill competency is a critical corollary of nursing practice. In the intensive care unit (ICU) setting, patients and families have cited skilled communication as a core element of high-quality care [3,6]. Proficiency in this realm enhances nurses’ understanding of the patient and family’s encounter with health care and provides a vehicle to gather information, inform, teach, and offer emotional support. Additionally, it identifies values, goals, health care preferences, worries and concerns, and facilitates the nurses’ coordination of care [7]. Despite this skill’s importance, however, it is generally not taught in basic education and until recently has been overlooked as a key competency [8,9].

Skilled communication in palliative and end-of-life care is pivotal for discussing prognosis and care planning. In the acute care setting this is particularly relevant as the majority of Americans die in hospitals versus their preferred site of home [10]. Additionally, 1 in 5 Americans die during or shortly after receiving care in an ICU [11]. Hence, while the ICU is a setting in which intensive effort to save lives is employed, it is also a setting where death frequently occurs. The complexity and highly emotive nature of critical care often results in family needs for information and support not being met [12]. A number of reasons for this occurrence have been proposed. In this paper, we will delineate barriers to critical care nurses’ involvement in prognosis and goals of care discussions, identify why nurse involvement in this communication is needed, describe a unique workshop exemplar with a sample role play that characterizes the workshop, and offer recommendations for colleagues interested in replicating similar education offerings.

Barriers to Communication

In the ICU, the sheer number of professionals families interact with may cause confusion. In particular, numerous medical consultants commonly offer opposing opinions. Additionally, each specialist may provide information that focuses on their area of expertise such that the “big picture” is not relayed to the patient and family. Emotional discomfort on the part of the health professional around discussions of poor prognosis, goals of care, and code status may prompt limiting discussion time with patients and families and even the avoidance of interpersonal exchanges [13–15]. Health professionals have also reported concern that end-of-life discussions will increase patient distress [16]. Among health care professionals, the subject of mortality may prompt personal anxiety, trigger unresolved grief, or fear that they will “become emotional” in front of the patient/family [7]. Lack of knowledge about cultural and religious norms has been cited as a barrier, as has time constraints [17,18]. Most frequently, inadequate or absent communication skill training is noted as a significant barrier [19,20]. Many ICU nurses also report feeling marginalized due their exclusion from goals of care and decision-making discussions with patients and families they know well [21,22].

Nurses As Key Palliative Care Communicators

Education efforts that foster communication proficiency during serious illness have traditionally focused on training physicians. Recently, nursing has become a focus of communication skill enhancement in recognition of nurses’ intense and protracted interactions with patients and families in the acute care setting. Nurses are the ‘constant’ in the patient and family’s journey through the fragmented health care system [21,23]. They often have the best knowledge of, and strongest relationship with, the family and often have had extensive discussions with them about their loved one’s status [24]. Nurses are aware of the patients’ symptom experiences and are privy to valuable information about the concerns and priorities of patients and families [12]. Additionally, having the most continuous presence, nurses have seen and heard interactions with clinicians from numerous disciplines. Nurses are the most visible, constant resource for patient and family education, information and support, and thus they perceive one of their most important roles to be that of advocate for the patient and family [20,21].

Communication Training Programs for Critical Care Nurses

Education is critical to enhance communication skills within palliative care [7,15,17,20,21,24]. The preferred teaching style within this realm is role play, where skills can be practiced and the affective component of engaging in sensitive discussions can be addressed [25–27]. Role play also demonstrates firsthand the importance of nonverbal communication (eg, body language, proximity, use of gestures, tone of voice) [7,20] and facilitates nurses’ gaining a sense of comfort with wordless communication [18].

Communication skills training programs have been designed to provide bedside critical care nurses with the tools they need to be active participants in discussions of prognosis, goals of care, and palliative care with families and physicians [27,28]. These programs have demonstrated improvement in nurses’ confidence to engage in key palliative care-related discussions. Essential elements of these programs include (1) delineation of the role of the bedside nurse in palliative care communication; (2) presentation and learner-centered practice of communication skills using role play; and (3) a reflection session focused on self-care and sustainability.

Across the 5 academic University of California medical centers (San Francisco, Davis, Los Angeles, Irvine, and San Diego), a communication training program based on this work has been implemented [29]. The one-day workshop, entitled IMPACT-ICU (Integrating Multidisciplinary Palliative Care into the ICU), has taught a total of 527 critical care nurses across the 5 centers. In addition to classroom training, the IMPACT-ICU program also includes proactive specialty palliative nursing support for bedside nurses by facilitating the availability of palliative care advanced practice nurses and nurse educators resources. This support helps nurses to apply the skills learned in the workshop in their practice. During rounds at the bedside, the nurse resources coach the bedside staff on the “how” and “when” of addressing palliative care needs. Education and support on a range of topics are offered, including clarifying goals and interventions provided by palliative care teams, the specifics of how to provide family emotional support and delivery of understandable information, the assessment and management of symptoms distress, and the nurses’ role in organizing and participating in family meetings. Case-specific consultations are also offered that address how to interface with resistant medical staff. The importance of nurse documentation of these varied exchanges is also emphasized.

IMPACT-ICU Workshop

A maximum of 15 nurses participate in each 8-hour workshop. The session begins with introductions and small group discussions about what the participants perceive to be the greatest barriers to goals of care discussions and fostering patient/family decision-making in the ICU. Participants are also asked to reflect on what they want to learn as a result of their workshop attendance.

A short didactic session then reviews the definition of palliative care and its core components, addresses the nurses’ role in communication within palliative care, a social worker’s perspective of what it is like to be a family member in the ICU, and the outline of the day. This includes delineation of expectations for involvement within the role plays and the various roles to be enacted. An emphasis is placed on the workshop being a safe place to explore and trial skills with the support of colleagues, and that practice is the optimum way to integrate communication expertise into the nurses’ skill set.

The “4 Cs” serves as the instructional basis for nurse communication skill enhancement [27]. This model outlines 4 key nursing roles in optimizing communication within palliative care:

Convening: Making sure multidisciplinary patient/family/clinician communication occurs.

Checking: Identifying the patient and family needs for information; ensuring that patients and families clearly receive desired information; ensuring that clinicians understand patient and family perspectives.

Caring: Naming emotions and responding to feeling.

Continuing: Following up after discussions to clarify and reinforce information and provide support.

Sample Role Play

Facilitator: So our first role play is focused on eliciting patient and family perspectives and needs. I need a learner and someone to play the role of the family member.

Learner: I’ll give it a try.

Facilitator: Lisa, you’re going to do great. Who wants to play the family member?

Workshop Participant: I’ll do it.

Facilitator: So Mary (who has agreed to play the role of the wife), why don’t you read us the scenario. (She reads it out loud to the group).

Facilitator: Lisa, as the nurse, I want you to look at your guide and tell me what your goal is for this conversation with Mrs. Ames and then which skill you want to practice.

Learner: I think I want to try eliciting the patient and family’s needs for information and I’ll try “Tell Me More” statements.

Facilitator: Alright. So remember Lisa, if you feel the conversation isn’t going well, you can call a “time out.” I can do this as well if I feel you need to start over. I’ll also call a time out when I feel you have met your goal. Sound OK? Mary, do you have any questions playing the part of Mrs. Ames?

Wife Role: Well, how hard should I make this for her? Should I be one of those “difficult” family members?

Facilitator: Our goal here is not to “stump” you or make it particularly difficult. We want you to try out these skills and get a sense of your “comfort zone.” So let’s start with some basic communication skills, OK?

Wife Role: Alright.

Facilitator: Why don’t we set the stage, such that Lisa, you are Mr. Ames’ nurse assessing him at the start of your shift, when Mrs. Ames enters. This is the first time you have taken care of him. The night nurse has told you that he has been requiring increasing ventilator support and his renal function is declining. Per Mrs. Ames’ request, the night nurse called her to let her know how he was doing and Mrs. Ames told her she would be in shortly.

Wife Role: (nervously enters the room and grasps her husband’s hand and looks at the nurse). How’s he doing? Is he better? The night nurse called me and I was so worried I rushed over here.

Learner: (Turns to Mrs. Ames and extends her hand). Are you Mrs. Ames? I’m Lisa and I am going to be taking care of Mr. Ames today. Let me just finish my assessment and how about we talk then? Will that be OK? It will be just a few minutes.

Wife Role: Alright, I’ll be in the waiting area but please come get me as soon as you can.

Learner: I will. (Nurse then shortly comes into the waiting area and asks Mrs. Ames to come back into the ICU where she invites her to sit just outside Mr. Ames’ room). Mrs. Ames, how are you doing? This must be so stressful for you, having your husband in the ICU.

Wife Role: It’s awful. He’s never been in the hospital before this and look at him, all hooked up to machines. I’m so worried. He seems to be getting worse instead of better.

Learner: What’s your understanding of what is going on?

Wife Role: I really don’t know. One doctor comes in and says one thing and then another comes in and tells me the opposite. I’m so confused I don’t know what to think.

Learner: Would having a better idea of his condition from the doctors who are treating him help you have a better understanding?

Wife Role: Oh, yes, but they always seem in such a hurry.

Learner: What exactly would you like to know?

Wife: Well, I want to know when he can get off that breathing machine because we have been planning to go to our son’s house for Thanksgiving.

Facilitator: Time out. Lisa, did you meet your conversation goal?

Learner: Um, I’m not sure, I guess so.

Facilitator: (Turns to Observers). What do you think, did she meet her goal?

Observer: Yes, she determined Mrs. Ames’ need for more information and she asked her what she wanted to know exactly.

Facilitator: What else did we see Lisa do to enhance communication with Mrs. Ames?

Observer: Well, when Mrs. Ames rushed into the room and asked her for information, Lisa didn’t just jump in and spout out values for the ventilator and his output. She took the time to introduce herself and de-escalate Mrs. Ames’ anxiety and she followed up on her promise to come get her in the waiting room as soon as she could.

Facilitator: Why do you think was important?

Observer: It helps establish trust.

Facilitator: Did Lisa use the skill she wanted to try out?

Observer: Yes.

Facilitator: How do you know? What did you hear her say?

Observer: She said, “What’s your understanding of what is going on with Mr. Ames?”

Facilitator: Absolutely. Great job, Lisa. And who wants to take a guess at how long Lisa’s exchange with Mrs. Ames took?

Observer: Less than two minutes?

Facilitator: That’s right. So just as you consider how long it takes, and how proficient you are, in starting an IV or inserting a Foley catheter, when you have a goal in mind and have practiced the skills to do it well, any skill can be mastered.

Feedback

Participants in the workshops uniformly report an enhanced sense of self-confidence in their palliative care communication skills as a result of their participation [29]. Key to the success of the workshop is the ongoing contact by the workshop facilitators with participants. Rounding is routinely planned such that each participant is visited weekly by a workshop facilitator in their clinical area to determine if the bedside nurse has practiced the new skills and if so, how the interaction transpired. Positive feedback is given for attempts to engage in new behaviors and participants are reminded that with any new skill, repetitive trials are necessary to foster success.

Lessons Learned and Next Steps

One of our major lessons learned was recognizing that it was difficult for many critical care nurses to practice the new communication skills. Nurses are trained to fix problems and perform medico-technical tasks; “listening” has not always been recognized as real work [18]. We needed to reinforce that skills like eliciting another’s perspective or making reflection statements are equally important to those associated with behavioral/technical proficiency.

While our program has been successful, we recognize that the next step in fostering ideal palliative care communication is to provide education within an interdisciplinary context. We recommend that colleagues interested in replicating this or a similar education intervention, survey nurse participants prior to and following workshop participation to measure attitudes, self confidence and perceived barriers over time [30]. We hope to translate our positive experience into a program that engages multiple professionals in the enhancement of optimum palliative care communication proficiency.

Corresponding author: Deborah A. Boyle MSN, RN, AOCNS, Department of Nursing Quality, Research and Education, University of California, Irvine Health, 101 The City Drive, Bldg 22A, Room 3104, Orange, CA 92868.

From the University of California Irvine Health/Chao Family Comprehensive Cancer Center Orange, CA (Ms. Boyle) and the University of California San Francisco Medical Center, San Francisco, CA (Dr. Anderson).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe components of a unique interactive workshop focusing on the enhancement of critical care nurses’ communication skills within the realm of prognosis and goals of care discussions with family members and physicians.

- Methods: A series of one-day workshops were offered to critical care nurses practicing in the 5 University of California hospital settings. After workshop attendance, nurse participants were followed by workshop facilitators in their units to ensure new communication skills were being integrated into practice and to problem solve if barriers were met.

- Results: Improvement in nurses’ self-confidence in engaging in these discussions was seen. This confidence was sustained months following workshop participation.

- Conclusion: The combination of critical care nurse workshop participation that involved skill enhancement through role-playing, in combination with clinical follow-up with attendees, resulted in positive affirmation of nurse communication skills specific to prognosis and goals of care discussions with family members and physicians.

There is increasing evidence that in the absence of quality communication between professional caregivers and those they care for, negative outcomes may prevail, such as reduced patient/family satisfaction, lower health status awareness, and a decreased sense of being cared about and cared for [1–5]. Communication skill competency is a critical corollary of nursing practice. In the intensive care unit (ICU) setting, patients and families have cited skilled communication as a core element of high-quality care [3,6]. Proficiency in this realm enhances nurses’ understanding of the patient and family’s encounter with health care and provides a vehicle to gather information, inform, teach, and offer emotional support. Additionally, it identifies values, goals, health care preferences, worries and concerns, and facilitates the nurses’ coordination of care [7]. Despite this skill’s importance, however, it is generally not taught in basic education and until recently has been overlooked as a key competency [8,9].

Skilled communication in palliative and end-of-life care is pivotal for discussing prognosis and care planning. In the acute care setting this is particularly relevant as the majority of Americans die in hospitals versus their preferred site of home [10]. Additionally, 1 in 5 Americans die during or shortly after receiving care in an ICU [11]. Hence, while the ICU is a setting in which intensive effort to save lives is employed, it is also a setting where death frequently occurs. The complexity and highly emotive nature of critical care often results in family needs for information and support not being met [12]. A number of reasons for this occurrence have been proposed. In this paper, we will delineate barriers to critical care nurses’ involvement in prognosis and goals of care discussions, identify why nurse involvement in this communication is needed, describe a unique workshop exemplar with a sample role play that characterizes the workshop, and offer recommendations for colleagues interested in replicating similar education offerings.

Barriers to Communication

In the ICU, the sheer number of professionals families interact with may cause confusion. In particular, numerous medical consultants commonly offer opposing opinions. Additionally, each specialist may provide information that focuses on their area of expertise such that the “big picture” is not relayed to the patient and family. Emotional discomfort on the part of the health professional around discussions of poor prognosis, goals of care, and code status may prompt limiting discussion time with patients and families and even the avoidance of interpersonal exchanges [13–15]. Health professionals have also reported concern that end-of-life discussions will increase patient distress [16]. Among health care professionals, the subject of mortality may prompt personal anxiety, trigger unresolved grief, or fear that they will “become emotional” in front of the patient/family [7]. Lack of knowledge about cultural and religious norms has been cited as a barrier, as has time constraints [17,18]. Most frequently, inadequate or absent communication skill training is noted as a significant barrier [19,20]. Many ICU nurses also report feeling marginalized due their exclusion from goals of care and decision-making discussions with patients and families they know well [21,22].

Nurses As Key Palliative Care Communicators

Education efforts that foster communication proficiency during serious illness have traditionally focused on training physicians. Recently, nursing has become a focus of communication skill enhancement in recognition of nurses’ intense and protracted interactions with patients and families in the acute care setting. Nurses are the ‘constant’ in the patient and family’s journey through the fragmented health care system [21,23]. They often have the best knowledge of, and strongest relationship with, the family and often have had extensive discussions with them about their loved one’s status [24]. Nurses are aware of the patients’ symptom experiences and are privy to valuable information about the concerns and priorities of patients and families [12]. Additionally, having the most continuous presence, nurses have seen and heard interactions with clinicians from numerous disciplines. Nurses are the most visible, constant resource for patient and family education, information and support, and thus they perceive one of their most important roles to be that of advocate for the patient and family [20,21].

Communication Training Programs for Critical Care Nurses

Education is critical to enhance communication skills within palliative care [7,15,17,20,21,24]. The preferred teaching style within this realm is role play, where skills can be practiced and the affective component of engaging in sensitive discussions can be addressed [25–27]. Role play also demonstrates firsthand the importance of nonverbal communication (eg, body language, proximity, use of gestures, tone of voice) [7,20] and facilitates nurses’ gaining a sense of comfort with wordless communication [18].

Communication skills training programs have been designed to provide bedside critical care nurses with the tools they need to be active participants in discussions of prognosis, goals of care, and palliative care with families and physicians [27,28]. These programs have demonstrated improvement in nurses’ confidence to engage in key palliative care-related discussions. Essential elements of these programs include (1) delineation of the role of the bedside nurse in palliative care communication; (2) presentation and learner-centered practice of communication skills using role play; and (3) a reflection session focused on self-care and sustainability.

Across the 5 academic University of California medical centers (San Francisco, Davis, Los Angeles, Irvine, and San Diego), a communication training program based on this work has been implemented [29]. The one-day workshop, entitled IMPACT-ICU (Integrating Multidisciplinary Palliative Care into the ICU), has taught a total of 527 critical care nurses across the 5 centers. In addition to classroom training, the IMPACT-ICU program also includes proactive specialty palliative nursing support for bedside nurses by facilitating the availability of palliative care advanced practice nurses and nurse educators resources. This support helps nurses to apply the skills learned in the workshop in their practice. During rounds at the bedside, the nurse resources coach the bedside staff on the “how” and “when” of addressing palliative care needs. Education and support on a range of topics are offered, including clarifying goals and interventions provided by palliative care teams, the specifics of how to provide family emotional support and delivery of understandable information, the assessment and management of symptoms distress, and the nurses’ role in organizing and participating in family meetings. Case-specific consultations are also offered that address how to interface with resistant medical staff. The importance of nurse documentation of these varied exchanges is also emphasized.

IMPACT-ICU Workshop

A maximum of 15 nurses participate in each 8-hour workshop. The session begins with introductions and small group discussions about what the participants perceive to be the greatest barriers to goals of care discussions and fostering patient/family decision-making in the ICU. Participants are also asked to reflect on what they want to learn as a result of their workshop attendance.

A short didactic session then reviews the definition of palliative care and its core components, addresses the nurses’ role in communication within palliative care, a social worker’s perspective of what it is like to be a family member in the ICU, and the outline of the day. This includes delineation of expectations for involvement within the role plays and the various roles to be enacted. An emphasis is placed on the workshop being a safe place to explore and trial skills with the support of colleagues, and that practice is the optimum way to integrate communication expertise into the nurses’ skill set.

The “4 Cs” serves as the instructional basis for nurse communication skill enhancement [27]. This model outlines 4 key nursing roles in optimizing communication within palliative care:

Convening: Making sure multidisciplinary patient/family/clinician communication occurs.

Checking: Identifying the patient and family needs for information; ensuring that patients and families clearly receive desired information; ensuring that clinicians understand patient and family perspectives.

Caring: Naming emotions and responding to feeling.

Continuing: Following up after discussions to clarify and reinforce information and provide support.

Sample Role Play

Facilitator: So our first role play is focused on eliciting patient and family perspectives and needs. I need a learner and someone to play the role of the family member.

Learner: I’ll give it a try.

Facilitator: Lisa, you’re going to do great. Who wants to play the family member?

Workshop Participant: I’ll do it.

Facilitator: So Mary (who has agreed to play the role of the wife), why don’t you read us the scenario. (She reads it out loud to the group).

Facilitator: Lisa, as the nurse, I want you to look at your guide and tell me what your goal is for this conversation with Mrs. Ames and then which skill you want to practice.

Learner: I think I want to try eliciting the patient and family’s needs for information and I’ll try “Tell Me More” statements.

Facilitator: Alright. So remember Lisa, if you feel the conversation isn’t going well, you can call a “time out.” I can do this as well if I feel you need to start over. I’ll also call a time out when I feel you have met your goal. Sound OK? Mary, do you have any questions playing the part of Mrs. Ames?

Wife Role: Well, how hard should I make this for her? Should I be one of those “difficult” family members?

Facilitator: Our goal here is not to “stump” you or make it particularly difficult. We want you to try out these skills and get a sense of your “comfort zone.” So let’s start with some basic communication skills, OK?

Wife Role: Alright.

Facilitator: Why don’t we set the stage, such that Lisa, you are Mr. Ames’ nurse assessing him at the start of your shift, when Mrs. Ames enters. This is the first time you have taken care of him. The night nurse has told you that he has been requiring increasing ventilator support and his renal function is declining. Per Mrs. Ames’ request, the night nurse called her to let her know how he was doing and Mrs. Ames told her she would be in shortly.

Wife Role: (nervously enters the room and grasps her husband’s hand and looks at the nurse). How’s he doing? Is he better? The night nurse called me and I was so worried I rushed over here.

Learner: (Turns to Mrs. Ames and extends her hand). Are you Mrs. Ames? I’m Lisa and I am going to be taking care of Mr. Ames today. Let me just finish my assessment and how about we talk then? Will that be OK? It will be just a few minutes.

Wife Role: Alright, I’ll be in the waiting area but please come get me as soon as you can.

Learner: I will. (Nurse then shortly comes into the waiting area and asks Mrs. Ames to come back into the ICU where she invites her to sit just outside Mr. Ames’ room). Mrs. Ames, how are you doing? This must be so stressful for you, having your husband in the ICU.

Wife Role: It’s awful. He’s never been in the hospital before this and look at him, all hooked up to machines. I’m so worried. He seems to be getting worse instead of better.

Learner: What’s your understanding of what is going on?

Wife Role: I really don’t know. One doctor comes in and says one thing and then another comes in and tells me the opposite. I’m so confused I don’t know what to think.

Learner: Would having a better idea of his condition from the doctors who are treating him help you have a better understanding?

Wife Role: Oh, yes, but they always seem in such a hurry.

Learner: What exactly would you like to know?

Wife: Well, I want to know when he can get off that breathing machine because we have been planning to go to our son’s house for Thanksgiving.

Facilitator: Time out. Lisa, did you meet your conversation goal?

Learner: Um, I’m not sure, I guess so.

Facilitator: (Turns to Observers). What do you think, did she meet her goal?

Observer: Yes, she determined Mrs. Ames’ need for more information and she asked her what she wanted to know exactly.

Facilitator: What else did we see Lisa do to enhance communication with Mrs. Ames?

Observer: Well, when Mrs. Ames rushed into the room and asked her for information, Lisa didn’t just jump in and spout out values for the ventilator and his output. She took the time to introduce herself and de-escalate Mrs. Ames’ anxiety and she followed up on her promise to come get her in the waiting room as soon as she could.

Facilitator: Why do you think was important?

Observer: It helps establish trust.

Facilitator: Did Lisa use the skill she wanted to try out?

Observer: Yes.

Facilitator: How do you know? What did you hear her say?

Observer: She said, “What’s your understanding of what is going on with Mr. Ames?”

Facilitator: Absolutely. Great job, Lisa. And who wants to take a guess at how long Lisa’s exchange with Mrs. Ames took?

Observer: Less than two minutes?

Facilitator: That’s right. So just as you consider how long it takes, and how proficient you are, in starting an IV or inserting a Foley catheter, when you have a goal in mind and have practiced the skills to do it well, any skill can be mastered.

Feedback

Participants in the workshops uniformly report an enhanced sense of self-confidence in their palliative care communication skills as a result of their participation [29]. Key to the success of the workshop is the ongoing contact by the workshop facilitators with participants. Rounding is routinely planned such that each participant is visited weekly by a workshop facilitator in their clinical area to determine if the bedside nurse has practiced the new skills and if so, how the interaction transpired. Positive feedback is given for attempts to engage in new behaviors and participants are reminded that with any new skill, repetitive trials are necessary to foster success.

Lessons Learned and Next Steps

One of our major lessons learned was recognizing that it was difficult for many critical care nurses to practice the new communication skills. Nurses are trained to fix problems and perform medico-technical tasks; “listening” has not always been recognized as real work [18]. We needed to reinforce that skills like eliciting another’s perspective or making reflection statements are equally important to those associated with behavioral/technical proficiency.

While our program has been successful, we recognize that the next step in fostering ideal palliative care communication is to provide education within an interdisciplinary context. We recommend that colleagues interested in replicating this or a similar education intervention, survey nurse participants prior to and following workshop participation to measure attitudes, self confidence and perceived barriers over time [30]. We hope to translate our positive experience into a program that engages multiple professionals in the enhancement of optimum palliative care communication proficiency.

Corresponding author: Deborah A. Boyle MSN, RN, AOCNS, Department of Nursing Quality, Research and Education, University of California, Irvine Health, 101 The City Drive, Bldg 22A, Room 3104, Orange, CA 92868.

1. Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, et al. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest 2012;142:128–33.

2. Osborn TR, Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, et al. Identifying elements of ICU care that families report as important but unsatisfactory: decision-making, control and ICU atmosphere. Chest 2012;142:1185–92.

3. Nelson JE, Puntillo K, Pronovost PJ, et al. In their own words: patients and families define high-quality palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2010;38:808–18.

4. Nels W, Gabrijel S, Kiss S, et al. Communication skill training significantly improves lung cancer patients understanding. J Palliat Care Med 2014;4:182.

5. Van Vliet LM, Epstein AS. Current state of the art and science of patient-clinician communication in progressive disease: patients’ need to know and feel known. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3474-8.

6. Troug RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end of life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 2008;36:953–63.

7. Dahlin CM, Wittenberg E. Communication in palliative care. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice J, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014:81–109.

8. Baer L, Weinstein E. Improving oncology nurses’ communication skills for difficult conversations. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2013;17:E45–E51.

9. Treece PD. Communication in the intensive care unit about end of life care. AACN Adv Crit Care 2007;18:406–14.

10. Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end of life care at the last place of care. JAMA 2004;291:88–92.

11. Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICU End-of-Life Peer Group. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med 2004;32:638–43.

12. Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med 2007;35:422–9.

13. Back AL, Trinidad SB, Hopley EK, Edwards KA. Reframing the goals of care conversation: “We’re in a different place.” J Palliat Med 2014;17:1010–24.

14. Aslakson RA, Wyskiel R, Thornton I, et al. Nurse perceived barriers to effective communication regarding prognosis and optimal end of life care for surgical ICU patients: a qualitative exploration. J Palliat Med 2012;15:910–5.

15. Erickson J. Bedside nurse involvement in end of life decision-making. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2013;32:65–8.

16. Bernacki RE, Block SD for the American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003.

17. You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al. Barriers to goals of care discussion with ‘seriously’ ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:549–56.

18. Strang S, Henoch I, Danielson E, et al. Communication about existential issues with patients close to death: nurses’ reflections on content, process, and meaning. Psychooncology 2014;23:562–8.

19. Slatore CG, Hensen L, Gauzine L, et al. Communication by nurses in the intensive care unit: qualitative analysis of domains in patient-centered care. Am J Crit Care 2012;21:410–8.

20. Wittenberg-Lyles E, Goldsmith J, Platt CS. Palliative care communication. Sem Oncol Nurs 2014;30:280–6.

21. Fox MY. Improving communication with patients and families in the ICU: palliative care strategies for intensive care unit nurses. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2014;16:93–8.

22. Beckstrand RL, Callister LC, Kirchhoff KT. Providing a ‘good death’: critical care nurses’ suggestions for improving end of life care. Am J Crit Care 2006;15:38–45.

23. Peereboom K, Coyle N. Facilitating goals of care discus.sions for patients with life-limiting disease: communication strategies for nurses. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2012; 14:251–8.

24. Nelson JE, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, et al. Integrating palliative care in the ICU: the nurse in the leading role. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2011;13:89–94.

25. Jors K, Seibel K, Bardenheuer H, et al. Education in end of life care: what do experienced professionals find important? J Cancer Educ 2015 March 15.

26. Roze des Ordons AL, Sharma N, Heyland DK, et al. Strategies for effective goals of care discussions and decision-making: perspective from a multi-centre survey of Canadian hospital-based health care providers. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:38.

27. Krimshtein NS, Luhrs CA, Puntillo KA, et al. Training nurses for interdisciplinary communication with families in the ICU. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1325–32.

28. Milic MM, Puntillo K, Turner K, et al. Communicating with patients’ families and physicians about prognosis and goals of care. Am J Crit Care 2015;24:e56–e64.

29. Anderson W, Puntillo K, Barbour S, et al. The IMPACT-ICU Project: expanding palliative care nursing across University of California Centers ICUs to advance palliative care. Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) national seminar. Nov 7–9, 2013. Dallas, TX.

30. Anderson WG, Puntillo K, Boyle D, et al. ICU bedside nurses’ involvement in palliative care communication: a multicenter survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. In press.

1. Leung JM, Udris EM, Uman J, et al. The effect of end-of-life discussions on perceived quality of care and health status among patients with COPD. Chest 2012;142:128–33.

2. Osborn TR, Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, et al. Identifying elements of ICU care that families report as important but unsatisfactory: decision-making, control and ICU atmosphere. Chest 2012;142:1185–92.

3. Nelson JE, Puntillo K, Pronovost PJ, et al. In their own words: patients and families define high-quality palliative care in the ICU. Crit Care Med 2010;38:808–18.

4. Nels W, Gabrijel S, Kiss S, et al. Communication skill training significantly improves lung cancer patients understanding. J Palliat Care Med 2014;4:182.

5. Van Vliet LM, Epstein AS. Current state of the art and science of patient-clinician communication in progressive disease: patients’ need to know and feel known. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3474-8.

6. Troug RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end of life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 2008;36:953–63.

7. Dahlin CM, Wittenberg E. Communication in palliative care. In: Ferrell BR, Coyle N, Paice J, editors. Oxford textbook of palliative nursing. 4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2014:81–109.

8. Baer L, Weinstein E. Improving oncology nurses’ communication skills for difficult conversations. Clin J Oncol Nurs 2013;17:E45–E51.

9. Treece PD. Communication in the intensive care unit about end of life care. AACN Adv Crit Care 2007;18:406–14.

10. Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end of life care at the last place of care. JAMA 2004;291:88–92.

11. Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Robert Wood Johnson Foundation ICU End-of-Life Peer Group. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: an epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med 2004;32:638–43.

12. Hamric AB, Blackhall LJ. Nurse-physician perspectives on the care of dying patients in intensive care units: collaboration, moral distress, and ethical climate. Crit Care Med 2007;35:422–9.

13. Back AL, Trinidad SB, Hopley EK, Edwards KA. Reframing the goals of care conversation: “We’re in a different place.” J Palliat Med 2014;17:1010–24.

14. Aslakson RA, Wyskiel R, Thornton I, et al. Nurse perceived barriers to effective communication regarding prognosis and optimal end of life care for surgical ICU patients: a qualitative exploration. J Palliat Med 2012;15:910–5.

15. Erickson J. Bedside nurse involvement in end of life decision-making. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2013;32:65–8.

16. Bernacki RE, Block SD for the American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med 2014;174:1994–2003.

17. You JJ, Downar J, Fowler RA, et al. Barriers to goals of care discussion with ‘seriously’ ill hospitalized patients and their families: a multicenter survey of clinicians. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:549–56.

18. Strang S, Henoch I, Danielson E, et al. Communication about existential issues with patients close to death: nurses’ reflections on content, process, and meaning. Psychooncology 2014;23:562–8.

19. Slatore CG, Hensen L, Gauzine L, et al. Communication by nurses in the intensive care unit: qualitative analysis of domains in patient-centered care. Am J Crit Care 2012;21:410–8.

20. Wittenberg-Lyles E, Goldsmith J, Platt CS. Palliative care communication. Sem Oncol Nurs 2014;30:280–6.

21. Fox MY. Improving communication with patients and families in the ICU: palliative care strategies for intensive care unit nurses. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2014;16:93–8.

22. Beckstrand RL, Callister LC, Kirchhoff KT. Providing a ‘good death’: critical care nurses’ suggestions for improving end of life care. Am J Crit Care 2006;15:38–45.

23. Peereboom K, Coyle N. Facilitating goals of care discus.sions for patients with life-limiting disease: communication strategies for nurses. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2012; 14:251–8.

24. Nelson JE, Cortez TB, Curtis JR, et al. Integrating palliative care in the ICU: the nurse in the leading role. J Hospice Palliat Nurs 2011;13:89–94.

25. Jors K, Seibel K, Bardenheuer H, et al. Education in end of life care: what do experienced professionals find important? J Cancer Educ 2015 March 15.

26. Roze des Ordons AL, Sharma N, Heyland DK, et al. Strategies for effective goals of care discussions and decision-making: perspective from a multi-centre survey of Canadian hospital-based health care providers. BMC Palliat Care 2015;14:38.

27. Krimshtein NS, Luhrs CA, Puntillo KA, et al. Training nurses for interdisciplinary communication with families in the ICU. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1325–32.

28. Milic MM, Puntillo K, Turner K, et al. Communicating with patients’ families and physicians about prognosis and goals of care. Am J Crit Care 2015;24:e56–e64.

29. Anderson W, Puntillo K, Barbour S, et al. The IMPACT-ICU Project: expanding palliative care nursing across University of California Centers ICUs to advance palliative care. Center to Advance Palliative Care (CAPC) national seminar. Nov 7–9, 2013. Dallas, TX.

30. Anderson WG, Puntillo K, Boyle D, et al. ICU bedside nurses’ involvement in palliative care communication: a multicenter survey. J Pain Symptom Manage. In press.