User login

Erythematous patches with keratotic annular borders on the glans penis

A 31-year-old man presented to the emergency department with meatal inflammation, dysuria, and mucopurulent penile discharge, diagnosed as urethritis and treated empirically with levofloxacin. He was referred to the genitourinary medicine clinic for a full screening for sexually transmitted disease. The results were negative.

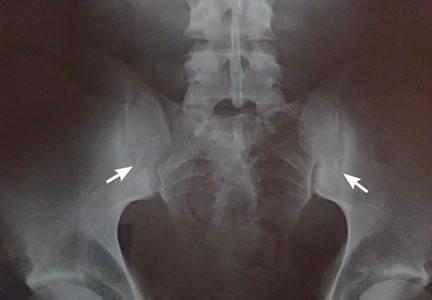

Two months later, he returned with pain and redness in his left eye and inflammatory lumbar pain. The glans penis had small pustules that ruptured, leaving painless superficial erosions that coalesced to form a serpiginous pattern (Figure 1). Radiography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed features of grade 3 bilateral sacroiliitis (Figure 2): subchondral sclerosis of both sacral and iliac articular margins (predominantly on the iliac side), erosions, reduced articular space, widening of the joint space, and incipient ankylosis. A diagnosis of reactive arthritis was made based on the presence of urethritis, ocular symptoms, circinate balanitis, and radiologic evidence of sacroiliitis. In addition, the chronic inflammatory back pain and bilateral sacroiliitis indicated developing ankylosing spondylitis according to the modified New York criteria.

Our patient’s circinate balanitis resolved with hydrocortisone cream, and treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug brought improvement of the joint symptoms.

THE MANY FEATURES OF REACTIVE ARTHRITIS

The American Rheumatology Association diagnostic criteria for reactive arthritis include asymmetric arthritis that lasts at least 1 month and at least one of the following symptoms: urethritis, inflammatory eye disease, mouth ulcers, circinate balanitis, and radiographic evidence of sarcoiliitis, periostitis, or heel spurs.1,2

Keratoderma blennorrhagicum is another extra-articular manifestation. These symptoms typically start within 1 to 6 weeks after urogenital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or gastrointestinal infection with Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, or Campylobacter species.1–3

There is great variation in the severity, number, and timing of clinical features in reactive arthritis. The diagnosis can be difficult because only about one-third of patients show the complete classic triad (conjunctivitis, urethritis, arthritis). HLA-B27 positivity is associated with more frequent skin lesions and axial involvement.4,5

- Wu IB, Schwartz RA. Reiter’s syndrome: the classic triad and more. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59:113–121.

- Koga T, Miyashita T, Watanabe T, et al. Reactive arthritis which occurred one year after acute chlamydial urethritis. Intern Med 2008; 47:663–666.

- Carter JD. Treating reactive arthritis: insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2010; 2:45–54.

- Willkens RF, Arnett FC, Bitter T, et al. Reiter’s syndrome: evaluation of preliminary criteria for definite disease. Arthritis Rheum 1981; 24:844–849.

- Bakkour W, Chularojanamontri L, Motta L, Chalmers RJ. Successful use of dapsone for the management of circinate balanitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014; 39:333–335.

A 31-year-old man presented to the emergency department with meatal inflammation, dysuria, and mucopurulent penile discharge, diagnosed as urethritis and treated empirically with levofloxacin. He was referred to the genitourinary medicine clinic for a full screening for sexually transmitted disease. The results were negative.

Two months later, he returned with pain and redness in his left eye and inflammatory lumbar pain. The glans penis had small pustules that ruptured, leaving painless superficial erosions that coalesced to form a serpiginous pattern (Figure 1). Radiography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed features of grade 3 bilateral sacroiliitis (Figure 2): subchondral sclerosis of both sacral and iliac articular margins (predominantly on the iliac side), erosions, reduced articular space, widening of the joint space, and incipient ankylosis. A diagnosis of reactive arthritis was made based on the presence of urethritis, ocular symptoms, circinate balanitis, and radiologic evidence of sacroiliitis. In addition, the chronic inflammatory back pain and bilateral sacroiliitis indicated developing ankylosing spondylitis according to the modified New York criteria.

Our patient’s circinate balanitis resolved with hydrocortisone cream, and treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug brought improvement of the joint symptoms.

THE MANY FEATURES OF REACTIVE ARTHRITIS

The American Rheumatology Association diagnostic criteria for reactive arthritis include asymmetric arthritis that lasts at least 1 month and at least one of the following symptoms: urethritis, inflammatory eye disease, mouth ulcers, circinate balanitis, and radiographic evidence of sarcoiliitis, periostitis, or heel spurs.1,2

Keratoderma blennorrhagicum is another extra-articular manifestation. These symptoms typically start within 1 to 6 weeks after urogenital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or gastrointestinal infection with Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, or Campylobacter species.1–3

There is great variation in the severity, number, and timing of clinical features in reactive arthritis. The diagnosis can be difficult because only about one-third of patients show the complete classic triad (conjunctivitis, urethritis, arthritis). HLA-B27 positivity is associated with more frequent skin lesions and axial involvement.4,5

A 31-year-old man presented to the emergency department with meatal inflammation, dysuria, and mucopurulent penile discharge, diagnosed as urethritis and treated empirically with levofloxacin. He was referred to the genitourinary medicine clinic for a full screening for sexually transmitted disease. The results were negative.

Two months later, he returned with pain and redness in his left eye and inflammatory lumbar pain. The glans penis had small pustules that ruptured, leaving painless superficial erosions that coalesced to form a serpiginous pattern (Figure 1). Radiography and magnetic resonance imaging revealed features of grade 3 bilateral sacroiliitis (Figure 2): subchondral sclerosis of both sacral and iliac articular margins (predominantly on the iliac side), erosions, reduced articular space, widening of the joint space, and incipient ankylosis. A diagnosis of reactive arthritis was made based on the presence of urethritis, ocular symptoms, circinate balanitis, and radiologic evidence of sacroiliitis. In addition, the chronic inflammatory back pain and bilateral sacroiliitis indicated developing ankylosing spondylitis according to the modified New York criteria.

Our patient’s circinate balanitis resolved with hydrocortisone cream, and treatment with a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug brought improvement of the joint symptoms.

THE MANY FEATURES OF REACTIVE ARTHRITIS

The American Rheumatology Association diagnostic criteria for reactive arthritis include asymmetric arthritis that lasts at least 1 month and at least one of the following symptoms: urethritis, inflammatory eye disease, mouth ulcers, circinate balanitis, and radiographic evidence of sarcoiliitis, periostitis, or heel spurs.1,2

Keratoderma blennorrhagicum is another extra-articular manifestation. These symptoms typically start within 1 to 6 weeks after urogenital infection with Chlamydia trachomatis or gastrointestinal infection with Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, or Campylobacter species.1–3

There is great variation in the severity, number, and timing of clinical features in reactive arthritis. The diagnosis can be difficult because only about one-third of patients show the complete classic triad (conjunctivitis, urethritis, arthritis). HLA-B27 positivity is associated with more frequent skin lesions and axial involvement.4,5

- Wu IB, Schwartz RA. Reiter’s syndrome: the classic triad and more. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59:113–121.

- Koga T, Miyashita T, Watanabe T, et al. Reactive arthritis which occurred one year after acute chlamydial urethritis. Intern Med 2008; 47:663–666.

- Carter JD. Treating reactive arthritis: insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2010; 2:45–54.

- Willkens RF, Arnett FC, Bitter T, et al. Reiter’s syndrome: evaluation of preliminary criteria for definite disease. Arthritis Rheum 1981; 24:844–849.

- Bakkour W, Chularojanamontri L, Motta L, Chalmers RJ. Successful use of dapsone for the management of circinate balanitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014; 39:333–335.

- Wu IB, Schwartz RA. Reiter’s syndrome: the classic triad and more. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008; 59:113–121.

- Koga T, Miyashita T, Watanabe T, et al. Reactive arthritis which occurred one year after acute chlamydial urethritis. Intern Med 2008; 47:663–666.

- Carter JD. Treating reactive arthritis: insights for the clinician. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2010; 2:45–54.

- Willkens RF, Arnett FC, Bitter T, et al. Reiter’s syndrome: evaluation of preliminary criteria for definite disease. Arthritis Rheum 1981; 24:844–849.

- Bakkour W, Chularojanamontri L, Motta L, Chalmers RJ. Successful use of dapsone for the management of circinate balanitis. Clin Exp Dermatol 2014; 39:333–335.

Erythema and atrophy on the tongue

A 26-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department with a 6-month history of a painful burning sensation on the tongue. Examination revealed a reddish, atrophic area on the dorsum of the tongue (Figure 1).

She had been treated unsuccessfully with topical antifungal drugs (clotrimazole and nystatin) for a presumed diagnosis of oral candidiasis. Otherwise, her medical history was notable only for occasional episodes of epigastric pain. She did not smoke or drink alcohol.

Fungal culture and oral exfoliative cytology studies were negative.

Laboratory results:

- Red blood cell count 3.9 × 1012/L (reference range 4.2–5.4)

- Hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL (12–16)

- Mean corpuscular volume 92 fL (80–99)

- Mean corpuscular hemoglobin 29 pg (27–34)

- Iron 14 μg/dL (37–145),

- Vitamin B12 119 pg/dL (250–900)

- Zinc 33 μg/dL (66–110)

- Serum gastric parietal cell antibody positive

- Serum creatinine and liver enzyme tests were normal.

Biopsy of the gastric mucosa revealed severe atrophic gastritis, so the possibility of atrophy related to gastroesophageal reflux was considered. But the laboratory results and the patient’s presentation pointed to iron deficiency and pernicious anemia (due to deficiency of vitamin B12). Zinc deficiency is associated with oral burning but not atrophic glossitis.

Based on the patient’s symptoms and the testing results, she was given the diagnosis of atrophic glossitis. She was treated with oral iron supplementation, intramuscular injections of vitamin B12, and oral zinc supplementation. The glossitis resolved, and the gastric symptoms improved within 2 months, thus supporting our diagnosis of atrophic glossitis.

ATROPHIC GLOSSITIS

The diagnosis of abnormalities of the tongue requires a thorough history, including onset and duration, antecedent symptoms, and tobacco and alcohol use. Examination of tongue morphology is also important.1 Tongue abnormalities related to tobacco use and to alcohol use include leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucosal fibrosis, lichen planus, and oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Atrophic glossitis is often linked to an underlying nutritional deficiency of iron, folic acid, vitamin B12, riboflavin, or niacin, although other nutritional deficiencies can be implicated. As noted, zinc deficiency can cause oral burning but not atrophic glossitis, and it resolves with correction of the underlying deficiency.2 Cobalamin deficiency is the main cause of atrophic glossitis.

As our patient’s presentation illustrated, oral symptoms can be multifactorial. Oral conditions may be an early clinical manifestation of a nutritional deficiency, but they can also reflect an alteration of the gastric mucosa3; a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection; neoplastic disease; autoimmune disease; endocrine disorder; local mechanical trauma; exposure to an irritant; or an allergic reaction.2

- Reamy BV, Derby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician 2010; 81:627–634.

- Chi AC, Neville BW, Krayer JW, Gonsalves WC. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician 2010; 82:1381–1388.

- Sun A, Lin HP, Wang YP, Chiang CP. Significant association of deficiency of hemoglobin, iron and vitamin B12, high homocysteine level, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity with atrophic glossitis. J Oral Pathol Med 2012; 41:500–504.

A 26-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department with a 6-month history of a painful burning sensation on the tongue. Examination revealed a reddish, atrophic area on the dorsum of the tongue (Figure 1).

She had been treated unsuccessfully with topical antifungal drugs (clotrimazole and nystatin) for a presumed diagnosis of oral candidiasis. Otherwise, her medical history was notable only for occasional episodes of epigastric pain. She did not smoke or drink alcohol.

Fungal culture and oral exfoliative cytology studies were negative.

Laboratory results:

- Red blood cell count 3.9 × 1012/L (reference range 4.2–5.4)

- Hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL (12–16)

- Mean corpuscular volume 92 fL (80–99)

- Mean corpuscular hemoglobin 29 pg (27–34)

- Iron 14 μg/dL (37–145),

- Vitamin B12 119 pg/dL (250–900)

- Zinc 33 μg/dL (66–110)

- Serum gastric parietal cell antibody positive

- Serum creatinine and liver enzyme tests were normal.

Biopsy of the gastric mucosa revealed severe atrophic gastritis, so the possibility of atrophy related to gastroesophageal reflux was considered. But the laboratory results and the patient’s presentation pointed to iron deficiency and pernicious anemia (due to deficiency of vitamin B12). Zinc deficiency is associated with oral burning but not atrophic glossitis.

Based on the patient’s symptoms and the testing results, she was given the diagnosis of atrophic glossitis. She was treated with oral iron supplementation, intramuscular injections of vitamin B12, and oral zinc supplementation. The glossitis resolved, and the gastric symptoms improved within 2 months, thus supporting our diagnosis of atrophic glossitis.

ATROPHIC GLOSSITIS

The diagnosis of abnormalities of the tongue requires a thorough history, including onset and duration, antecedent symptoms, and tobacco and alcohol use. Examination of tongue morphology is also important.1 Tongue abnormalities related to tobacco use and to alcohol use include leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucosal fibrosis, lichen planus, and oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Atrophic glossitis is often linked to an underlying nutritional deficiency of iron, folic acid, vitamin B12, riboflavin, or niacin, although other nutritional deficiencies can be implicated. As noted, zinc deficiency can cause oral burning but not atrophic glossitis, and it resolves with correction of the underlying deficiency.2 Cobalamin deficiency is the main cause of atrophic glossitis.

As our patient’s presentation illustrated, oral symptoms can be multifactorial. Oral conditions may be an early clinical manifestation of a nutritional deficiency, but they can also reflect an alteration of the gastric mucosa3; a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection; neoplastic disease; autoimmune disease; endocrine disorder; local mechanical trauma; exposure to an irritant; or an allergic reaction.2

A 26-year-old woman was referred to the dermatology department with a 6-month history of a painful burning sensation on the tongue. Examination revealed a reddish, atrophic area on the dorsum of the tongue (Figure 1).

She had been treated unsuccessfully with topical antifungal drugs (clotrimazole and nystatin) for a presumed diagnosis of oral candidiasis. Otherwise, her medical history was notable only for occasional episodes of epigastric pain. She did not smoke or drink alcohol.

Fungal culture and oral exfoliative cytology studies were negative.

Laboratory results:

- Red blood cell count 3.9 × 1012/L (reference range 4.2–5.4)

- Hemoglobin 11.3 g/dL (12–16)

- Mean corpuscular volume 92 fL (80–99)

- Mean corpuscular hemoglobin 29 pg (27–34)

- Iron 14 μg/dL (37–145),

- Vitamin B12 119 pg/dL (250–900)

- Zinc 33 μg/dL (66–110)

- Serum gastric parietal cell antibody positive

- Serum creatinine and liver enzyme tests were normal.

Biopsy of the gastric mucosa revealed severe atrophic gastritis, so the possibility of atrophy related to gastroesophageal reflux was considered. But the laboratory results and the patient’s presentation pointed to iron deficiency and pernicious anemia (due to deficiency of vitamin B12). Zinc deficiency is associated with oral burning but not atrophic glossitis.

Based on the patient’s symptoms and the testing results, she was given the diagnosis of atrophic glossitis. She was treated with oral iron supplementation, intramuscular injections of vitamin B12, and oral zinc supplementation. The glossitis resolved, and the gastric symptoms improved within 2 months, thus supporting our diagnosis of atrophic glossitis.

ATROPHIC GLOSSITIS

The diagnosis of abnormalities of the tongue requires a thorough history, including onset and duration, antecedent symptoms, and tobacco and alcohol use. Examination of tongue morphology is also important.1 Tongue abnormalities related to tobacco use and to alcohol use include leukoplakia, erythroplakia, oral submucosal fibrosis, lichen planus, and oral squamous cell carcinoma.

Atrophic glossitis is often linked to an underlying nutritional deficiency of iron, folic acid, vitamin B12, riboflavin, or niacin, although other nutritional deficiencies can be implicated. As noted, zinc deficiency can cause oral burning but not atrophic glossitis, and it resolves with correction of the underlying deficiency.2 Cobalamin deficiency is the main cause of atrophic glossitis.

As our patient’s presentation illustrated, oral symptoms can be multifactorial. Oral conditions may be an early clinical manifestation of a nutritional deficiency, but they can also reflect an alteration of the gastric mucosa3; a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection; neoplastic disease; autoimmune disease; endocrine disorder; local mechanical trauma; exposure to an irritant; or an allergic reaction.2

- Reamy BV, Derby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician 2010; 81:627–634.

- Chi AC, Neville BW, Krayer JW, Gonsalves WC. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician 2010; 82:1381–1388.

- Sun A, Lin HP, Wang YP, Chiang CP. Significant association of deficiency of hemoglobin, iron and vitamin B12, high homocysteine level, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity with atrophic glossitis. J Oral Pathol Med 2012; 41:500–504.

- Reamy BV, Derby R, Bunt CW. Common tongue conditions in primary care. Am Fam Physician 2010; 81:627–634.

- Chi AC, Neville BW, Krayer JW, Gonsalves WC. Oral manifestations of systemic disease. Am Fam Physician 2010; 82:1381–1388.

- Sun A, Lin HP, Wang YP, Chiang CP. Significant association of deficiency of hemoglobin, iron and vitamin B12, high homocysteine level, and gastric parietal cell antibody positivity with atrophic glossitis. J Oral Pathol Med 2012; 41:500–504.