User login

Desquamating pustular rash

A 66-year-old man presented with burning pain and erythema over the left axilla, and pustules that had ruptured and crusted over. The rash also involved the right axilla, trunk, abdomen, and face.

He said the symptoms had developed 3 days after starting to use ciprofloxacin eye drops for eye redness and purulent discharge that had been diagnosed as bacterial conjunctivitis. He was taking no other new medications. He was afebrile.

The ciprofloxacin drops were stopped. The skin lesions were treated with emollients, topical steroids, and topical mupirocin. Improvement was noted 3 days into the hospitalization, as the lesions started to crust over and dry up and no new lesions were forming. The conjunctivitis improved with topical bacitracin ointment and prednisolone drops.

ACUTE GENERALIZED EXANTHEMATOUS PUSTULOSIS

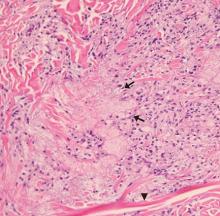

The differential diagnosis of drug-related acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis includes Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pustular psoriasis, folliculitis, and varicella infection. The characteristic features of the rash and lesions and the temporal relationship between the start of ciprofloxacin eye drops and the development of symptoms, combined with rapid resolution of symptoms within days after discontinuing the drops, accompanied by skin biopsy study showing diffuse spongiosis with scattered eosinophils and a subcorneal pustule, confirmed the diagnosis of AGEP.

Key features of AGEP include numerous small, sterile, nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background with associated fever and sometimes neutrophilia and eosinophilia.1 It usually begins on the face or in the intertriginous areas and then spreads to the trunk and lower limbs with rare mucosal involvement.1 It can be associated with viral infections, but most reported cases are related to drug reactions.2

Our patient’s case was unusual because AGEP triggered by topical medications is rarely reported, especially with ophthalmic medications.3 Drugs most commonly implicated are antibiotics including penicillins, sulfonamides, and quinolones, but other drugs such as terbinafine, diltiazem, and hydroxychloroquine have also been associated.2

AGEP may present with extensive skin desquamation, as in our patient, sometimes with bullae formation and skin sloughing manifesting as AGEP with overlapping toxic epidermal necrolysis.4

Diagnosis entails a careful review of medications, attention to lesion morphology, compatible disease course, and a high index of suspicion. Treatment is supportive and consists of stopping the offending agent, wound care, and antipyretics. Evidence for the use of steroids is weak.5

TAKE-HOME POINTS

AGEP should be considered in sudden-onset pustular desquamating erythematous rash related to use of a new medication. It is important to be aware that topical and ophthalmic medications are possible triggers. A thorough medication review should be done. Antibiotics are the most commonly implicated medications. An alternative medication should be tried. Treatment is supportive, as the condition is usually self-limiting once the offending medication is discontinued. Rarely, extensive desquamation and bullae formation may occur, which may be a manifestation of overlap features with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, Brochez L. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts. Eur J Dermatol 2010; 20(4):425–433. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.0932

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case–control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol 2007; 157(5):989–996. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08156.x

- Beltran C, Vergier B, Doutre MS, Beylot C, Beylot-Barry M. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical application of Algipan. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2009; 136(10):709–712. French. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2008.10.042

- Peermohamed S, Haber RM. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis simulating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 2011; 147(6):697–701. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.147

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17(8). pii:E1214. doi:10.3390/ijms17081214

A 66-year-old man presented with burning pain and erythema over the left axilla, and pustules that had ruptured and crusted over. The rash also involved the right axilla, trunk, abdomen, and face.

He said the symptoms had developed 3 days after starting to use ciprofloxacin eye drops for eye redness and purulent discharge that had been diagnosed as bacterial conjunctivitis. He was taking no other new medications. He was afebrile.

The ciprofloxacin drops were stopped. The skin lesions were treated with emollients, topical steroids, and topical mupirocin. Improvement was noted 3 days into the hospitalization, as the lesions started to crust over and dry up and no new lesions were forming. The conjunctivitis improved with topical bacitracin ointment and prednisolone drops.

ACUTE GENERALIZED EXANTHEMATOUS PUSTULOSIS

The differential diagnosis of drug-related acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis includes Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pustular psoriasis, folliculitis, and varicella infection. The characteristic features of the rash and lesions and the temporal relationship between the start of ciprofloxacin eye drops and the development of symptoms, combined with rapid resolution of symptoms within days after discontinuing the drops, accompanied by skin biopsy study showing diffuse spongiosis with scattered eosinophils and a subcorneal pustule, confirmed the diagnosis of AGEP.

Key features of AGEP include numerous small, sterile, nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background with associated fever and sometimes neutrophilia and eosinophilia.1 It usually begins on the face or in the intertriginous areas and then spreads to the trunk and lower limbs with rare mucosal involvement.1 It can be associated with viral infections, but most reported cases are related to drug reactions.2

Our patient’s case was unusual because AGEP triggered by topical medications is rarely reported, especially with ophthalmic medications.3 Drugs most commonly implicated are antibiotics including penicillins, sulfonamides, and quinolones, but other drugs such as terbinafine, diltiazem, and hydroxychloroquine have also been associated.2

AGEP may present with extensive skin desquamation, as in our patient, sometimes with bullae formation and skin sloughing manifesting as AGEP with overlapping toxic epidermal necrolysis.4

Diagnosis entails a careful review of medications, attention to lesion morphology, compatible disease course, and a high index of suspicion. Treatment is supportive and consists of stopping the offending agent, wound care, and antipyretics. Evidence for the use of steroids is weak.5

TAKE-HOME POINTS

AGEP should be considered in sudden-onset pustular desquamating erythematous rash related to use of a new medication. It is important to be aware that topical and ophthalmic medications are possible triggers. A thorough medication review should be done. Antibiotics are the most commonly implicated medications. An alternative medication should be tried. Treatment is supportive, as the condition is usually self-limiting once the offending medication is discontinued. Rarely, extensive desquamation and bullae formation may occur, which may be a manifestation of overlap features with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

A 66-year-old man presented with burning pain and erythema over the left axilla, and pustules that had ruptured and crusted over. The rash also involved the right axilla, trunk, abdomen, and face.

He said the symptoms had developed 3 days after starting to use ciprofloxacin eye drops for eye redness and purulent discharge that had been diagnosed as bacterial conjunctivitis. He was taking no other new medications. He was afebrile.

The ciprofloxacin drops were stopped. The skin lesions were treated with emollients, topical steroids, and topical mupirocin. Improvement was noted 3 days into the hospitalization, as the lesions started to crust over and dry up and no new lesions were forming. The conjunctivitis improved with topical bacitracin ointment and prednisolone drops.

ACUTE GENERALIZED EXANTHEMATOUS PUSTULOSIS

The differential diagnosis of drug-related acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis includes Stevens-Johnson syndrome, pustular psoriasis, folliculitis, and varicella infection. The characteristic features of the rash and lesions and the temporal relationship between the start of ciprofloxacin eye drops and the development of symptoms, combined with rapid resolution of symptoms within days after discontinuing the drops, accompanied by skin biopsy study showing diffuse spongiosis with scattered eosinophils and a subcorneal pustule, confirmed the diagnosis of AGEP.

Key features of AGEP include numerous small, sterile, nonfollicular pustules on an erythematous background with associated fever and sometimes neutrophilia and eosinophilia.1 It usually begins on the face or in the intertriginous areas and then spreads to the trunk and lower limbs with rare mucosal involvement.1 It can be associated with viral infections, but most reported cases are related to drug reactions.2

Our patient’s case was unusual because AGEP triggered by topical medications is rarely reported, especially with ophthalmic medications.3 Drugs most commonly implicated are antibiotics including penicillins, sulfonamides, and quinolones, but other drugs such as terbinafine, diltiazem, and hydroxychloroquine have also been associated.2

AGEP may present with extensive skin desquamation, as in our patient, sometimes with bullae formation and skin sloughing manifesting as AGEP with overlapping toxic epidermal necrolysis.4

Diagnosis entails a careful review of medications, attention to lesion morphology, compatible disease course, and a high index of suspicion. Treatment is supportive and consists of stopping the offending agent, wound care, and antipyretics. Evidence for the use of steroids is weak.5

TAKE-HOME POINTS

AGEP should be considered in sudden-onset pustular desquamating erythematous rash related to use of a new medication. It is important to be aware that topical and ophthalmic medications are possible triggers. A thorough medication review should be done. Antibiotics are the most commonly implicated medications. An alternative medication should be tried. Treatment is supportive, as the condition is usually self-limiting once the offending medication is discontinued. Rarely, extensive desquamation and bullae formation may occur, which may be a manifestation of overlap features with toxic epidermal necrolysis.

- Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, Brochez L. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts. Eur J Dermatol 2010; 20(4):425–433. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.0932

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case–control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol 2007; 157(5):989–996. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08156.x

- Beltran C, Vergier B, Doutre MS, Beylot C, Beylot-Barry M. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical application of Algipan. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2009; 136(10):709–712. French. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2008.10.042

- Peermohamed S, Haber RM. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis simulating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 2011; 147(6):697–701. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.147

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17(8). pii:E1214. doi:10.3390/ijms17081214

- Speeckaert MM, Speeckaert R, Lambert J, Brochez L. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: an overview of the clinical, immunological and diagnostic concepts. Eur J Dermatol 2010; 20(4):425–433. doi:10.1684/ejd.2010.0932

- Sidoroff A, Dunant A, Viboud C, et al. Risk factors for acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP)—results of a multinational case–control study (EuroSCAR). Br J Dermatol 2007; 157(5):989–996. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.08156.x

- Beltran C, Vergier B, Doutre MS, Beylot C, Beylot-Barry M. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis induced by topical application of Algipan. Ann Dermatol Venereol 2009; 136(10):709–712. French. doi:10.1016/j.annder.2008.10.042

- Peermohamed S, Haber RM. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis simulating toxic epidermal necrolysis: a case report and review of the literature. Arch Dermatol 2011; 147(6):697–701. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2011.147

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: pathogenesis, genetic background, clinical variants and therapy. Int J Mol Sci 2016; 17(8). pii:E1214. doi:10.3390/ijms17081214

Fissured tongue

A 43-year-old man presented with a 3-week history of halitosis. He was also concerned about the irregular appearance of his tongue, which he had noticed over the past 3 years. He had no history of wearing dentures or of any skin disorder.

A BROAD DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Fissured tongue (scrotal tongue, plicated tongue, lingua plicata) is a common normal variant of the tongue surface with a male preponderance and a reported prevalence of 10% to 20% in the general population, and the incidence increases strikingly with age.1

The cause is not known, but familial clustering is seen, and a polygenic or autosomal dominant hereditary component is presumed.1

The condition may be associated with removable dentures, geographic tongue, pernicious anemia, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, acromegaly, macroglossia, oral-facial-digital syndrome type I, Pierre Robin syndrome, Down syndrome, and Melkersson Rosenthal syndrome.2 It is usually asymptomatic, but if the fissures are deep, food may become lodged in them, resulting in tongue inflammation, burning sensation, and halitosis.1

Typically, fissures of varying depth extending to the margin are apparent on the dorsal surface of the tongue. The condition is confined to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, which is of ectodermal origin. Histologically, the epithelium, lamina propria, and musculature are all involved in the formation of the fissures.3 The deeper fissures may lack filliform papillae due to bacterial inflammation.3 The diagnosis is clinical, and treatment includes reassurance, advice on good oral hygiene, and tongue cleansing.1

- Feil ND, Filippi A. Frequency of fissured tongue (lingua plicata) as a function of age. Swiss Dent J 2016; 126(10):886–897. German. pmid:27808348

- Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS 3rd. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol 2016; 34(4):458–469. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.018

- Kullaa-Mikkonen A, Sorvari T. Lingua fissurata: a clinical, stereomicroscopic and histopathological study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1986; 15(5):525–533. pmid:3097176

A 43-year-old man presented with a 3-week history of halitosis. He was also concerned about the irregular appearance of his tongue, which he had noticed over the past 3 years. He had no history of wearing dentures or of any skin disorder.

A BROAD DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Fissured tongue (scrotal tongue, plicated tongue, lingua plicata) is a common normal variant of the tongue surface with a male preponderance and a reported prevalence of 10% to 20% in the general population, and the incidence increases strikingly with age.1

The cause is not known, but familial clustering is seen, and a polygenic or autosomal dominant hereditary component is presumed.1

The condition may be associated with removable dentures, geographic tongue, pernicious anemia, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, acromegaly, macroglossia, oral-facial-digital syndrome type I, Pierre Robin syndrome, Down syndrome, and Melkersson Rosenthal syndrome.2 It is usually asymptomatic, but if the fissures are deep, food may become lodged in them, resulting in tongue inflammation, burning sensation, and halitosis.1

Typically, fissures of varying depth extending to the margin are apparent on the dorsal surface of the tongue. The condition is confined to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, which is of ectodermal origin. Histologically, the epithelium, lamina propria, and musculature are all involved in the formation of the fissures.3 The deeper fissures may lack filliform papillae due to bacterial inflammation.3 The diagnosis is clinical, and treatment includes reassurance, advice on good oral hygiene, and tongue cleansing.1

A 43-year-old man presented with a 3-week history of halitosis. He was also concerned about the irregular appearance of his tongue, which he had noticed over the past 3 years. He had no history of wearing dentures or of any skin disorder.

A BROAD DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Fissured tongue (scrotal tongue, plicated tongue, lingua plicata) is a common normal variant of the tongue surface with a male preponderance and a reported prevalence of 10% to 20% in the general population, and the incidence increases strikingly with age.1

The cause is not known, but familial clustering is seen, and a polygenic or autosomal dominant hereditary component is presumed.1

The condition may be associated with removable dentures, geographic tongue, pernicious anemia, Sjögren syndrome, psoriasis, acromegaly, macroglossia, oral-facial-digital syndrome type I, Pierre Robin syndrome, Down syndrome, and Melkersson Rosenthal syndrome.2 It is usually asymptomatic, but if the fissures are deep, food may become lodged in them, resulting in tongue inflammation, burning sensation, and halitosis.1

Typically, fissures of varying depth extending to the margin are apparent on the dorsal surface of the tongue. The condition is confined to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue, which is of ectodermal origin. Histologically, the epithelium, lamina propria, and musculature are all involved in the formation of the fissures.3 The deeper fissures may lack filliform papillae due to bacterial inflammation.3 The diagnosis is clinical, and treatment includes reassurance, advice on good oral hygiene, and tongue cleansing.1

- Feil ND, Filippi A. Frequency of fissured tongue (lingua plicata) as a function of age. Swiss Dent J 2016; 126(10):886–897. German. pmid:27808348

- Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS 3rd. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol 2016; 34(4):458–469. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.018

- Kullaa-Mikkonen A, Sorvari T. Lingua fissurata: a clinical, stereomicroscopic and histopathological study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1986; 15(5):525–533. pmid:3097176

- Feil ND, Filippi A. Frequency of fissured tongue (lingua plicata) as a function of age. Swiss Dent J 2016; 126(10):886–897. German. pmid:27808348

- Mangold AR, Torgerson RR, Rogers RS 3rd. Diseases of the tongue. Clin Dermatol 2016; 34(4):458–469. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.018

- Kullaa-Mikkonen A, Sorvari T. Lingua fissurata: a clinical, stereomicroscopic and histopathological study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1986; 15(5):525–533. pmid:3097176

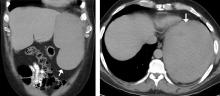

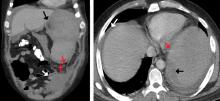

Atraumatic splenic rupture in acute myeloid leukemia

A 50-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a complex karyotype was admitted to the hospital with several days of dull, left-sided abdominal pain. His most recent bone marrow biopsy showed 30% blasts, and immunophenotyping was suggestive of persistent AML (CD13+, CD34+, CD117+, CD33+, CD7+, MPO–). He was on treatment with venetoclax and cytarabine after induction therapy had failed.

On admission, his heart rate was 101 beats per minute and his blood pressure was 122/85 mm Hg. Abdominal examination revealed mild distention, hepatomegaly, and previously known massive splenomegaly, with the splenic tip extending to the umbilicus, and mild tenderness.

Results of laboratory testing revealed persistent pancytopenia:

- Hemoglobin level 6.8 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Total white blood cell count 0.8 × 109/L (4.5–11.0)

- Platelet count 8 × 109/L (150–400).

The next day, he developed severe, acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain. A check of vital signs showed worsening sinus tachycardia at 132 beats per minute and a drop in blood pressure to 90/56 mm Hg. He had worsening diffuse abdominal tenderness with sluggish bowel sounds. His hemoglobin concentration was 6.4 g/dL and platelet count 12 × 109/L.

He received supportive transfusions of blood products. Surgical exploration was deemed risky, given his overall condition and severe thrombocytopenia. Splenic angiography showed no evidence of pseudoaneurysm or focal contrast extravasation. He underwent empiric embolization of the midsplenic artery, after which his hemodynamic status stabilized. He died 4 weeks later of acute respiratory failure from pneumonia.

SPLENIC RUPTURE IN AML

Atraumatic splenic rupture is rare but potentially life-threatening, especially if the diagnosis is delayed. Conditions that can cause splenomegaly and predispose to rupture include infection (infectious mononucleosis, malaria), malignant hematologic disorders (leukemia, lymphoma), other neoplasms, and amyloidosis.1

The literature includes a few reports of splenic rupture in patients with AML.2–4 The proposed mechanisms include bleeding from infarction sites or tumor foci, dysregulated hemostasis, and leukostasis.

The classic presentation of splenic rupture is acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain associated with hypotension and decreasing hemoglobin levels. CT of the abdomen is confirmatory, and resuscitation with crystalloids and blood products is a vital initial step in management. Choice of treatment depends on the patient’s surgical risk and hemodynamic status; options include conservative medical management, splenic artery embolization, and exploratory laparotomy.

In patients with AML and splenomegaly presenting with acute abdominal pain, clinicians need to be aware of this potential hematologic emergency.

- Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg 2009; 96(10):1114–1121. doi:10.1002/bjs.6737

- Gardner JA, Bao L, Ornstein DL. Spontaneous splenic rupture in acute myeloid leukemia with mixed-lineage leukemia gene rearrangement. Med Rep Case Stud 2016; 1:119. doi:10.4172/2572-5130.1000119

- Zeidan AM, Mitchell M, Khatri R, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture during induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2014; 55(1):209–212. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.796060

- Fahmi Y, Elabbasi T, Khaiz D, et al. Splenic spontaneous rupture associated with acute myeloïd leukemia: report of a case and literature review. Surgery Curr Res 2014; 4:170. doi:10.4172/2161-1076.1000170

A 50-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a complex karyotype was admitted to the hospital with several days of dull, left-sided abdominal pain. His most recent bone marrow biopsy showed 30% blasts, and immunophenotyping was suggestive of persistent AML (CD13+, CD34+, CD117+, CD33+, CD7+, MPO–). He was on treatment with venetoclax and cytarabine after induction therapy had failed.

On admission, his heart rate was 101 beats per minute and his blood pressure was 122/85 mm Hg. Abdominal examination revealed mild distention, hepatomegaly, and previously known massive splenomegaly, with the splenic tip extending to the umbilicus, and mild tenderness.

Results of laboratory testing revealed persistent pancytopenia:

- Hemoglobin level 6.8 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Total white blood cell count 0.8 × 109/L (4.5–11.0)

- Platelet count 8 × 109/L (150–400).

The next day, he developed severe, acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain. A check of vital signs showed worsening sinus tachycardia at 132 beats per minute and a drop in blood pressure to 90/56 mm Hg. He had worsening diffuse abdominal tenderness with sluggish bowel sounds. His hemoglobin concentration was 6.4 g/dL and platelet count 12 × 109/L.

He received supportive transfusions of blood products. Surgical exploration was deemed risky, given his overall condition and severe thrombocytopenia. Splenic angiography showed no evidence of pseudoaneurysm or focal contrast extravasation. He underwent empiric embolization of the midsplenic artery, after which his hemodynamic status stabilized. He died 4 weeks later of acute respiratory failure from pneumonia.

SPLENIC RUPTURE IN AML

Atraumatic splenic rupture is rare but potentially life-threatening, especially if the diagnosis is delayed. Conditions that can cause splenomegaly and predispose to rupture include infection (infectious mononucleosis, malaria), malignant hematologic disorders (leukemia, lymphoma), other neoplasms, and amyloidosis.1

The literature includes a few reports of splenic rupture in patients with AML.2–4 The proposed mechanisms include bleeding from infarction sites or tumor foci, dysregulated hemostasis, and leukostasis.

The classic presentation of splenic rupture is acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain associated with hypotension and decreasing hemoglobin levels. CT of the abdomen is confirmatory, and resuscitation with crystalloids and blood products is a vital initial step in management. Choice of treatment depends on the patient’s surgical risk and hemodynamic status; options include conservative medical management, splenic artery embolization, and exploratory laparotomy.

In patients with AML and splenomegaly presenting with acute abdominal pain, clinicians need to be aware of this potential hematologic emergency.

A 50-year-old man with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) with a complex karyotype was admitted to the hospital with several days of dull, left-sided abdominal pain. His most recent bone marrow biopsy showed 30% blasts, and immunophenotyping was suggestive of persistent AML (CD13+, CD34+, CD117+, CD33+, CD7+, MPO–). He was on treatment with venetoclax and cytarabine after induction therapy had failed.

On admission, his heart rate was 101 beats per minute and his blood pressure was 122/85 mm Hg. Abdominal examination revealed mild distention, hepatomegaly, and previously known massive splenomegaly, with the splenic tip extending to the umbilicus, and mild tenderness.

Results of laboratory testing revealed persistent pancytopenia:

- Hemoglobin level 6.8 g/dL (reference range 13.0–17.0)

- Total white blood cell count 0.8 × 109/L (4.5–11.0)

- Platelet count 8 × 109/L (150–400).

The next day, he developed severe, acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain. A check of vital signs showed worsening sinus tachycardia at 132 beats per minute and a drop in blood pressure to 90/56 mm Hg. He had worsening diffuse abdominal tenderness with sluggish bowel sounds. His hemoglobin concentration was 6.4 g/dL and platelet count 12 × 109/L.

He received supportive transfusions of blood products. Surgical exploration was deemed risky, given his overall condition and severe thrombocytopenia. Splenic angiography showed no evidence of pseudoaneurysm or focal contrast extravasation. He underwent empiric embolization of the midsplenic artery, after which his hemodynamic status stabilized. He died 4 weeks later of acute respiratory failure from pneumonia.

SPLENIC RUPTURE IN AML

Atraumatic splenic rupture is rare but potentially life-threatening, especially if the diagnosis is delayed. Conditions that can cause splenomegaly and predispose to rupture include infection (infectious mononucleosis, malaria), malignant hematologic disorders (leukemia, lymphoma), other neoplasms, and amyloidosis.1

The literature includes a few reports of splenic rupture in patients with AML.2–4 The proposed mechanisms include bleeding from infarction sites or tumor foci, dysregulated hemostasis, and leukostasis.

The classic presentation of splenic rupture is acute-onset left-sided abdominal pain associated with hypotension and decreasing hemoglobin levels. CT of the abdomen is confirmatory, and resuscitation with crystalloids and blood products is a vital initial step in management. Choice of treatment depends on the patient’s surgical risk and hemodynamic status; options include conservative medical management, splenic artery embolization, and exploratory laparotomy.

In patients with AML and splenomegaly presenting with acute abdominal pain, clinicians need to be aware of this potential hematologic emergency.

- Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg 2009; 96(10):1114–1121. doi:10.1002/bjs.6737

- Gardner JA, Bao L, Ornstein DL. Spontaneous splenic rupture in acute myeloid leukemia with mixed-lineage leukemia gene rearrangement. Med Rep Case Stud 2016; 1:119. doi:10.4172/2572-5130.1000119

- Zeidan AM, Mitchell M, Khatri R, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture during induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2014; 55(1):209–212. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.796060

- Fahmi Y, Elabbasi T, Khaiz D, et al. Splenic spontaneous rupture associated with acute myeloïd leukemia: report of a case and literature review. Surgery Curr Res 2014; 4:170. doi:10.4172/2161-1076.1000170

- Renzulli P, Hostettler A, Schoepfer AM, Gloor B, Candinas D. Systematic review of atraumatic splenic rupture. Br J Surg 2009; 96(10):1114–1121. doi:10.1002/bjs.6737

- Gardner JA, Bao L, Ornstein DL. Spontaneous splenic rupture in acute myeloid leukemia with mixed-lineage leukemia gene rearrangement. Med Rep Case Stud 2016; 1:119. doi:10.4172/2572-5130.1000119

- Zeidan AM, Mitchell M, Khatri R, et al. Spontaneous splenic rupture during induction chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma 2014; 55(1):209–212. doi:10.3109/10428194.2013.796060

- Fahmi Y, Elabbasi T, Khaiz D, et al. Splenic spontaneous rupture associated with acute myeloïd leukemia: report of a case and literature review. Surgery Curr Res 2014; 4:170. doi:10.4172/2161-1076.1000170

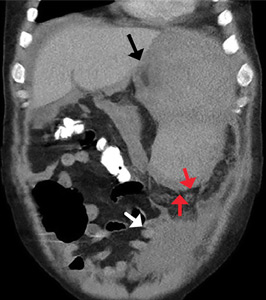

Vulvar and gluteal manifestations of Crohn disease

A 37-year-old woman presented with recurring painful swelling and erythema of the vulva over the last year. Despite a series of negative vaginal cultures, she was prescribed multiple courses of antifungal and antibacterial treatments, while her symptoms continued to worsen. She had no other relevant medical history except for occasional diarrhea and abdominal cramping, which were attributed to irritable bowel syndrome.

CROHN DISEASE OUTSIDE THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Crohn disease primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract but is associated with extraintestinal manifestations (in the oral cavity, eyes, skin, and joints) in up to 45% of patients.1

The most common mucocutaneous manifestations are granulomatous lesions that extend directly from the gastrointestinal tract, including perianal and peristomal skin tags, fistulas, and perineal ulcerations. In most cases, the onset of cutaneous manifestations follows intestinal disease, but vulvar Crohn disease may precede gastrointestinal symptoms in approximately 25% of patients, with the average age at onset in the mid-30s.1

The pathogenesis of vulvar Crohn disease remains unclear. One theory involves production of immune complexes from the gastrointestinal tract and a possible T-lymphocyte-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction.2

The diagnosis of vulvar Crohn disease should be considered in a patient who has vulvar pain, edema, and ulcerations not otherwise explained, whether or not gastrointestinal Crohn disease is present. The diagnosis is established with clinical history and characteristic histopathology on biopsy. Multiple biopsies may be needed, and early endoscopy is recommended to establish the diagnosis. The histologic features include noncaseating and nonnecrotizing granulomatous dermatitis or vulvitis with occasional reports of eosinophilic infiltrates and necrobiosis.5,6 An imaging study such as ultrasonography is sometimes used to differentiate between a specific cutaneous manifestation of Crohn disease and its complications such as perianal fistula or abscess.

Clinical vulvar lesions are nonspecific, and those of Crohn disease are frequently mistaken for infectious, inflammatory, or traumatic vulvitis. Diagnostic biopsy for histologic analysis is warranted.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, Gravante G, Giordano P. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg 2010; 8(1):2–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.012

- Siroy A, Wasman J. Metastatic Crohn disease: a rare cutaneous entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136(3):329–332. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0666-RS

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Selim MA. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol 2011; 33(6):588–593. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31820a2635

- Amankwah Y, Haefner H. Vulvar edema. Dermatol Clin 2010; 28(4):765–777. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.08.001

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a histopathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2008; 35(5):457–461. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00849.x

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol 1996; 132(8):928–932.

A 37-year-old woman presented with recurring painful swelling and erythema of the vulva over the last year. Despite a series of negative vaginal cultures, she was prescribed multiple courses of antifungal and antibacterial treatments, while her symptoms continued to worsen. She had no other relevant medical history except for occasional diarrhea and abdominal cramping, which were attributed to irritable bowel syndrome.

CROHN DISEASE OUTSIDE THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Crohn disease primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract but is associated with extraintestinal manifestations (in the oral cavity, eyes, skin, and joints) in up to 45% of patients.1

The most common mucocutaneous manifestations are granulomatous lesions that extend directly from the gastrointestinal tract, including perianal and peristomal skin tags, fistulas, and perineal ulcerations. In most cases, the onset of cutaneous manifestations follows intestinal disease, but vulvar Crohn disease may precede gastrointestinal symptoms in approximately 25% of patients, with the average age at onset in the mid-30s.1

The pathogenesis of vulvar Crohn disease remains unclear. One theory involves production of immune complexes from the gastrointestinal tract and a possible T-lymphocyte-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction.2

The diagnosis of vulvar Crohn disease should be considered in a patient who has vulvar pain, edema, and ulcerations not otherwise explained, whether or not gastrointestinal Crohn disease is present. The diagnosis is established with clinical history and characteristic histopathology on biopsy. Multiple biopsies may be needed, and early endoscopy is recommended to establish the diagnosis. The histologic features include noncaseating and nonnecrotizing granulomatous dermatitis or vulvitis with occasional reports of eosinophilic infiltrates and necrobiosis.5,6 An imaging study such as ultrasonography is sometimes used to differentiate between a specific cutaneous manifestation of Crohn disease and its complications such as perianal fistula or abscess.

Clinical vulvar lesions are nonspecific, and those of Crohn disease are frequently mistaken for infectious, inflammatory, or traumatic vulvitis. Diagnostic biopsy for histologic analysis is warranted.

A 37-year-old woman presented with recurring painful swelling and erythema of the vulva over the last year. Despite a series of negative vaginal cultures, she was prescribed multiple courses of antifungal and antibacterial treatments, while her symptoms continued to worsen. She had no other relevant medical history except for occasional diarrhea and abdominal cramping, which were attributed to irritable bowel syndrome.

CROHN DISEASE OUTSIDE THE GASTROINTESTINAL TRACT

Crohn disease primarily affects the gastrointestinal tract but is associated with extraintestinal manifestations (in the oral cavity, eyes, skin, and joints) in up to 45% of patients.1

The most common mucocutaneous manifestations are granulomatous lesions that extend directly from the gastrointestinal tract, including perianal and peristomal skin tags, fistulas, and perineal ulcerations. In most cases, the onset of cutaneous manifestations follows intestinal disease, but vulvar Crohn disease may precede gastrointestinal symptoms in approximately 25% of patients, with the average age at onset in the mid-30s.1

The pathogenesis of vulvar Crohn disease remains unclear. One theory involves production of immune complexes from the gastrointestinal tract and a possible T-lymphocyte-mediated type IV hypersensitivity reaction.2

The diagnosis of vulvar Crohn disease should be considered in a patient who has vulvar pain, edema, and ulcerations not otherwise explained, whether or not gastrointestinal Crohn disease is present. The diagnosis is established with clinical history and characteristic histopathology on biopsy. Multiple biopsies may be needed, and early endoscopy is recommended to establish the diagnosis. The histologic features include noncaseating and nonnecrotizing granulomatous dermatitis or vulvitis with occasional reports of eosinophilic infiltrates and necrobiosis.5,6 An imaging study such as ultrasonography is sometimes used to differentiate between a specific cutaneous manifestation of Crohn disease and its complications such as perianal fistula or abscess.

Clinical vulvar lesions are nonspecific, and those of Crohn disease are frequently mistaken for infectious, inflammatory, or traumatic vulvitis. Diagnostic biopsy for histologic analysis is warranted.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, Gravante G, Giordano P. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg 2010; 8(1):2–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.012

- Siroy A, Wasman J. Metastatic Crohn disease: a rare cutaneous entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136(3):329–332. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0666-RS

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Selim MA. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol 2011; 33(6):588–593. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31820a2635

- Amankwah Y, Haefner H. Vulvar edema. Dermatol Clin 2010; 28(4):765–777. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.08.001

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a histopathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2008; 35(5):457–461. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00849.x

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol 1996; 132(8):928–932.

- Andreani SM, Ratnasingham K, Dang HH, Gravante G, Giordano P. Crohn’s disease of the vulva. Int J Surg 2010; 8(1):2–5. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2009.09.012

- Siroy A, Wasman J. Metastatic Crohn disease: a rare cutaneous entity. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2012; 136(3):329–332. doi:10.5858/arpa.2010-0666-RS

- Foo WC, Papalas JA, Robboy SJ, Selim MA. Vulvar manifestations of Crohn’s disease. Am J Dermatopathol 2011; 33(6):588–593. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31820a2635

- Amankwah Y, Haefner H. Vulvar edema. Dermatol Clin 2010; 28(4):765–777. doi:10.1016/j.det.2010.08.001

- Emanuel PO, Phelps RG. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: a histopathologic study of 12 cases. J Cutan Pathol 2008; 35(5):457–461. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00849.x

- Hackzell-Bradley M, Hedblad MA, Stephansson EA. Metastatic Crohn’s disease: report of 3 cases with special reference to histopathologic findings. Arch Dermatol 1996; 132(8):928–932.

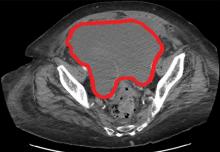

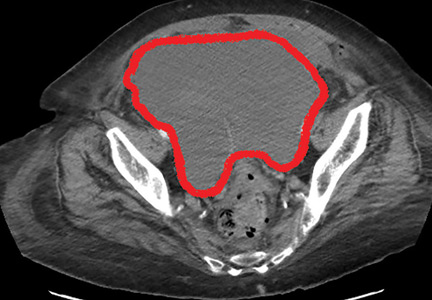

A complication of enoxaparin injection

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and palpitations and was found to have atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Medical therapy with drug therapy and cardioversion proved ineffective. She then underwent atrioventricular node ablation and placement of a pacemaker.

At the time of admission, anticoagulation was started with full-dose enoxaparin, injected subcutaneously on the left side of the abdominal wall, as her CHA2DS2-VASc score (http://chadvasc.org) was 5, due to age, female sex, and history of heart failure and hypertension.

Four days after admission, she reported lower abdominal pain, and her urine output was minimal. A bladder scan showed more than 500 mL of residual urine. She was hemodynamically stable, but physical examination revealed mild abdominal distention and tenderness in the suprapubic region. Laboratory testing showed a sharp rise in serum creatinine and a drop in hematocrit.

The patient was initially managed conservatively with serial physical examinations, monitoring of the hematocrit, serial imaging studies, and discontinuation of anticoagulation, but the pain and anuria persisted. Repeat computed tomography 15 days after admission showed that the hematoma had expanded, and she now had hydronephrosis on the right side as well, requiring urologic intervention with bilateral nephrostomy tube placement.

The size of the hematoma was evaluated with serial abdominal and pelvic examinations. After several days, her urine output had improved, the nephrostomy tubes were removed, and she was discharged.

RECTUS SHEATH HEMATOMA

Our patient had a giant pelvic hematoma, probably arising from the rectus sheath. This uncommon problem can arise from trauma, anticoagulation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure, but it can also occur spontaneously.1

In rectus sheath hematoma, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery is injured at its insertion into the rectus abdominis muscle. Symptoms arise if bleeding does not stop spontaneously from a tamponade effect.2

We speculate that in our patient, deep injection of enoxaparin into the abdominal wall injured the inferior epigastric artery, which started the hematoma, and the bleeding was exacerbated by the anticoagulation effect of the enoxaparin.

Another form of pelvic hematoma is retroperitoneal. It is most commonly caused by trauma but can occur due to rupture of the aorta, compression from tumors, or, infrequently, anticoagulation therapy.3

The role of anticoagulation

Spontaneous pelvic hematoma is usually missed as a cause of abdominal pain in patients on anticoagulation therapy and is mistaken for common acute conditions such as ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis, ovarian cyst torsion, and tumor.4 It usually develops within 5 days of starting anticoagulation therapy. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the hematoma and are best diagnosed with abdominal computed tomography, with sensitivity as high as 100%.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management, reserved for patients in stable condition, includes temporarily stopping and reevaluating the risks and benefits of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents, giving blood transfusions, and controlling pain. If conservative measures fail, options are arterial embolization, stent grafting, and blood vessel ligation.5 If these measures fail, patients should undergo surgical evacuation of the hematoma and ligation of bleeding vessels.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Subcutaneous injections, especially of anticoagulants, into the abdominal wall can increase the risk of hematoma. Other risk factors are older age, female sex, and thin body habitus with less abdominal fat.7 Healthcare professionals should avoid deep injections into the abdomen and should counsel patients and their caregivers about this, as well. The deltoid region could be a safer alternative.

- Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006; 85(2):105–110. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a

- Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015; 13:267–271. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015

- Haq MM, Taimur SDM, Khan SR, Rahman MA. Retroperitoneal hematoma following enoxaparin treatment in an elderly woman—a case report. Cardiovasc J 2010; 3(1):94–97. doi:10.3329/cardio.v3i1.6434

- Luhmann A, Williams EV. Rectus sheath hematoma: a series of unfortunate events. World J Surg 2006; 30(11):2050–2055. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0702-9

- Pace F, Colombo GM, Del Vecchio LR, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and fatal spontaneous extraperitoneal hematoma in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012; 12(1):172–174. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00742.x

- Velicki L, Cemerlic-Adic N, Bogdanovic D, Mrdanin T. Rectus sheath haematoma: enoxaparin-related complication. Acta Clin Belg 2013; 68(2):147–149. doi:10.2143/ACB.68.2.3213

- Sheth HS, Kumar R, DiNella J, Janov C, Kaldas H, Smith RE. Evaluation of risk factors for rectus sheath hematoma. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016; 22(3):292–296. doi:10.1177/1076029614553024

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and palpitations and was found to have atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Medical therapy with drug therapy and cardioversion proved ineffective. She then underwent atrioventricular node ablation and placement of a pacemaker.

At the time of admission, anticoagulation was started with full-dose enoxaparin, injected subcutaneously on the left side of the abdominal wall, as her CHA2DS2-VASc score (http://chadvasc.org) was 5, due to age, female sex, and history of heart failure and hypertension.

Four days after admission, she reported lower abdominal pain, and her urine output was minimal. A bladder scan showed more than 500 mL of residual urine. She was hemodynamically stable, but physical examination revealed mild abdominal distention and tenderness in the suprapubic region. Laboratory testing showed a sharp rise in serum creatinine and a drop in hematocrit.

The patient was initially managed conservatively with serial physical examinations, monitoring of the hematocrit, serial imaging studies, and discontinuation of anticoagulation, but the pain and anuria persisted. Repeat computed tomography 15 days after admission showed that the hematoma had expanded, and she now had hydronephrosis on the right side as well, requiring urologic intervention with bilateral nephrostomy tube placement.

The size of the hematoma was evaluated with serial abdominal and pelvic examinations. After several days, her urine output had improved, the nephrostomy tubes were removed, and she was discharged.

RECTUS SHEATH HEMATOMA

Our patient had a giant pelvic hematoma, probably arising from the rectus sheath. This uncommon problem can arise from trauma, anticoagulation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure, but it can also occur spontaneously.1

In rectus sheath hematoma, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery is injured at its insertion into the rectus abdominis muscle. Symptoms arise if bleeding does not stop spontaneously from a tamponade effect.2

We speculate that in our patient, deep injection of enoxaparin into the abdominal wall injured the inferior epigastric artery, which started the hematoma, and the bleeding was exacerbated by the anticoagulation effect of the enoxaparin.

Another form of pelvic hematoma is retroperitoneal. It is most commonly caused by trauma but can occur due to rupture of the aorta, compression from tumors, or, infrequently, anticoagulation therapy.3

The role of anticoagulation

Spontaneous pelvic hematoma is usually missed as a cause of abdominal pain in patients on anticoagulation therapy and is mistaken for common acute conditions such as ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis, ovarian cyst torsion, and tumor.4 It usually develops within 5 days of starting anticoagulation therapy. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the hematoma and are best diagnosed with abdominal computed tomography, with sensitivity as high as 100%.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management, reserved for patients in stable condition, includes temporarily stopping and reevaluating the risks and benefits of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents, giving blood transfusions, and controlling pain. If conservative measures fail, options are arterial embolization, stent grafting, and blood vessel ligation.5 If these measures fail, patients should undergo surgical evacuation of the hematoma and ligation of bleeding vessels.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Subcutaneous injections, especially of anticoagulants, into the abdominal wall can increase the risk of hematoma. Other risk factors are older age, female sex, and thin body habitus with less abdominal fat.7 Healthcare professionals should avoid deep injections into the abdomen and should counsel patients and their caregivers about this, as well. The deltoid region could be a safer alternative.

A 78-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with shortness of breath and palpitations and was found to have atrial fibrillation with rapid ventricular response. Medical therapy with drug therapy and cardioversion proved ineffective. She then underwent atrioventricular node ablation and placement of a pacemaker.

At the time of admission, anticoagulation was started with full-dose enoxaparin, injected subcutaneously on the left side of the abdominal wall, as her CHA2DS2-VASc score (http://chadvasc.org) was 5, due to age, female sex, and history of heart failure and hypertension.

Four days after admission, she reported lower abdominal pain, and her urine output was minimal. A bladder scan showed more than 500 mL of residual urine. She was hemodynamically stable, but physical examination revealed mild abdominal distention and tenderness in the suprapubic region. Laboratory testing showed a sharp rise in serum creatinine and a drop in hematocrit.

The patient was initially managed conservatively with serial physical examinations, monitoring of the hematocrit, serial imaging studies, and discontinuation of anticoagulation, but the pain and anuria persisted. Repeat computed tomography 15 days after admission showed that the hematoma had expanded, and she now had hydronephrosis on the right side as well, requiring urologic intervention with bilateral nephrostomy tube placement.

The size of the hematoma was evaluated with serial abdominal and pelvic examinations. After several days, her urine output had improved, the nephrostomy tubes were removed, and she was discharged.

RECTUS SHEATH HEMATOMA

Our patient had a giant pelvic hematoma, probably arising from the rectus sheath. This uncommon problem can arise from trauma, anticoagulation, or increased intra-abdominal pressure, but it can also occur spontaneously.1

In rectus sheath hematoma, a branch of the inferior epigastric artery is injured at its insertion into the rectus abdominis muscle. Symptoms arise if bleeding does not stop spontaneously from a tamponade effect.2

We speculate that in our patient, deep injection of enoxaparin into the abdominal wall injured the inferior epigastric artery, which started the hematoma, and the bleeding was exacerbated by the anticoagulation effect of the enoxaparin.

Another form of pelvic hematoma is retroperitoneal. It is most commonly caused by trauma but can occur due to rupture of the aorta, compression from tumors, or, infrequently, anticoagulation therapy.3

The role of anticoagulation

Spontaneous pelvic hematoma is usually missed as a cause of abdominal pain in patients on anticoagulation therapy and is mistaken for common acute conditions such as ulcer, diverticulitis, appendicitis, ovarian cyst torsion, and tumor.4 It usually develops within 5 days of starting anticoagulation therapy. Symptoms vary depending on the location of the hematoma and are best diagnosed with abdominal computed tomography, with sensitivity as high as 100%.

MANAGEMENT

Conservative management, reserved for patients in stable condition, includes temporarily stopping and reevaluating the risks and benefits of anticoagulation and antiplatelet agents, giving blood transfusions, and controlling pain. If conservative measures fail, options are arterial embolization, stent grafting, and blood vessel ligation.5 If these measures fail, patients should undergo surgical evacuation of the hematoma and ligation of bleeding vessels.6

TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

Subcutaneous injections, especially of anticoagulants, into the abdominal wall can increase the risk of hematoma. Other risk factors are older age, female sex, and thin body habitus with less abdominal fat.7 Healthcare professionals should avoid deep injections into the abdomen and should counsel patients and their caregivers about this, as well. The deltoid region could be a safer alternative.

- Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006; 85(2):105–110. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a

- Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015; 13:267–271. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015

- Haq MM, Taimur SDM, Khan SR, Rahman MA. Retroperitoneal hematoma following enoxaparin treatment in an elderly woman—a case report. Cardiovasc J 2010; 3(1):94–97. doi:10.3329/cardio.v3i1.6434

- Luhmann A, Williams EV. Rectus sheath hematoma: a series of unfortunate events. World J Surg 2006; 30(11):2050–2055. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0702-9

- Pace F, Colombo GM, Del Vecchio LR, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and fatal spontaneous extraperitoneal hematoma in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012; 12(1):172–174. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00742.x

- Velicki L, Cemerlic-Adic N, Bogdanovic D, Mrdanin T. Rectus sheath haematoma: enoxaparin-related complication. Acta Clin Belg 2013; 68(2):147–149. doi:10.2143/ACB.68.2.3213

- Sheth HS, Kumar R, DiNella J, Janov C, Kaldas H, Smith RE. Evaluation of risk factors for rectus sheath hematoma. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016; 22(3):292–296. doi:10.1177/1076029614553024

- Cherry WB, Mueller PS. Rectus sheath hematoma: review of 126 cases at a single institution. Medicine (Baltimore) 2006; 85(2):105–110. doi:10.1097/01.md.0000216818.13067.5a

- Hatjipetrou A, Anyfantakis D, Kastanakis M. Rectus sheath hematoma: a review of the literature. Int J Surg 2015; 13:267–271. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.12.015

- Haq MM, Taimur SDM, Khan SR, Rahman MA. Retroperitoneal hematoma following enoxaparin treatment in an elderly woman—a case report. Cardiovasc J 2010; 3(1):94–97. doi:10.3329/cardio.v3i1.6434

- Luhmann A, Williams EV. Rectus sheath hematoma: a series of unfortunate events. World J Surg 2006; 30(11):2050–2055. doi:10.1007/s00268-005-0702-9

- Pace F, Colombo GM, Del Vecchio LR, et al. Low molecular weight heparin and fatal spontaneous extraperitoneal hematoma in the elderly. Geriatr Gerontol Int 2012; 12(1):172–174. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0594.2011.00742.x

- Velicki L, Cemerlic-Adic N, Bogdanovic D, Mrdanin T. Rectus sheath haematoma: enoxaparin-related complication. Acta Clin Belg 2013; 68(2):147–149. doi:10.2143/ACB.68.2.3213

- Sheth HS, Kumar R, DiNella J, Janov C, Kaldas H, Smith RE. Evaluation of risk factors for rectus sheath hematoma. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2016; 22(3):292–296. doi:10.1177/1076029614553024

Diabetic dyslipidemia with eruptive xanthoma

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

A workup for secondary causes of hypertriglyceridemia was negative for hypothyroidism and nephrotic syndrome. She was currently taking no medications. She had no family history of dyslipidemia, and she denied alcohol consumption.

Based on the patient’s presentation, history, and the results of laboratory testing and skin biopsy, the diagnosis was eruptive xanthoma.

A RESULT OF ELEVATED TRIGLYCERIDES

Eruptive xanthoma is associated with elevation of chylomicrons and triglycerides.1 Hyperlipidemia that causes eruptive xanthoma may be familial (ie, due to a primary genetic defect) or secondary to another disease, or both.

Types of primary hypertriglyceridemia include elevated chylomicrons (Frederickson classification type I), elevated very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) (Frederickson type IV), and elevation of both chylomicrons and VLDL (Frederickson type V).2,3 Hypertriglyceridemia may also be secondary to obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, excess ethanol ingestion, and medicines such as retinoids and estrogens.2,3

Lesions of eruptive xanthoma are yellowish papules 2 to 5 mm in diameter surrounded by an erythematous border. They are formed by clusters of foamy cells caused by phagocytosis of macrophages as a consequence of increased accumulations of intracellular lipids. The most common sites are the buttocks, extensor surfaces of the arms, and the back.4

Eruptive xanthoma occurs with markedly elevated triglyceride levels (ie, > 1,000 mg/dL),5 with an estimated prevalence of 18 cases per 100,000 people (< 0.02%).6 Diagnosis is usually established through the clinical history, physical examination, and prompt laboratory confirmation of hypertriglyceridemia. Skin biopsy is rarely if ever needed.

RECOGNIZE AND TREAT PROMPTLY TO AVOID FURTHER COMPLICATIONS

Severe hypertriglyceridemia poses an increased risk of acute pancreatitis. Early recognition and medical treatment in our patient prevented serious complications.

Treatment of eruptive xanthoma includes identifying the underlying cause of hypertriglyceridemia and commencing lifestyle modifications that include weight reduction, aerobic exercise, a strict low-fat diet with avoidance of simple carbohydrates and alcohol,7 and drug therapy.

The patient’s treatment plan

Although HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) have a modest triglyceride-lowering effect and are useful to modify cardiovascular risk, fibric acid derivatives (eg, gemfibrozil, fenofibrate) are the first-line therapy.8 Omega-3 fatty acids, statins, or niacin may be added if necessary.8

Our patient’s uncontrolled glycemia caused marked hypertriglyceridemia, perhaps from a decrease in lipoprotein lipase activity in adipose tissue and muscle. Lifestyle modifications, glucose-lowering agents (metformin, glimepiride), and fenofibrate were prescribed. She was also advised to seek medical attention if she developed upper-abdominal pain, which could be a symptom of pancreatitis.

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213

- Flynn PD, Burns T, Breathnach S, Cox N, Griffiths C. Xanthomas and abnormalities of lipid metabolism and storage. In: Rook’s Textbook of Dermatology. 8th ed. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2010.

- Breckenridge WC, Alaupovic P, Cox DW, Little JA. Apolipoprotein and lipoprotein concentrations in familial apolipoprotein C-II deficiency. Atherosclerosis 1982; 44(2):223–235. pmid:7138621

- Santamarina-Fojo S. The familial chylomicronemia syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1998; 27(3):551–567. pmid:9785052

- Melmed S, Polonsky KS, Larsen PR, Kronenberg H. Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. 13th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2016.

- Zak A, Zeman M, Slaby A, Vecka M. Xanthomas: clinical and pathophysiological relations. Biomed Pap Med Fac Univ Palacky Olomouc Czech Repub 2014; 158(2):181–188. doi:10.5507/bp.2014.016

- Leaf DA. Chylomicronemia and the chylomicronemia syndrome: a practical approach to management. Am J Med 2008; 121(1):10–12. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.10.004

- Hegele RA, Ginsberg HN, Chapman MJ, et al; European Atherosclerosis Society Consensus Panel. The polygenic nature of hypertriglyceridaemia: implications for definition, diagnosis, and management. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2014; 2(8):655–666. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70191-8

- Berglund L, Brunzell JD, Goldberg AC, et al; Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of hypertriglyceridemia: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97(9):2969–2989. doi:10.1210/jc.2011-3213