User login

High-Grade Ovarian Serous Carcinoma Presenting as Androgenetic Alopecia

To the Editor:

Female pattern hair loss is common, and the literature suggests that up to 56% of women experience hair thinning in their lifetime, with increased prevalence in older women.1 Pathophysiology is incompletely understood and involves the nonscarring progressive miniaturization of hair follicles, causing decreased production of terminal hairs relative to more delicate vellus hairs. Because vellus hairs have a shorter anagen growth phase than terminal hairs, hair loss is expedited. Androgen excess, when present, hastens the process by inducing early transition of hair follicles from the anagen phase to the senescent telogen phase. Serum testosterone levels are within reference range in most female patients with hair loss, suggesting the presence of additional contributing factors.2

Given the high prevalence of female pattern hair loss and the harm of overlooking androgen excess and an androgen-secreting neoplasm, dermatologists must recognize indications for further evaluation. Additional signs of hyperandrogenism, such as menstrual irregularities, acne, hirsutism, anabolic appearance, voice deepening, and clitoromegaly, are reasons for concern.3 Elevated serum androgen levels also should raise suspicion of malignancy. Historically, a total testosterone level above 200 ng/dL or a dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) level greater than 700 µg/dL prompted evaluation for a tumor.4 More recent studies show that tumor-induced increases in serum androgen levels are highly variable, challenging the utility of these cutoffs.5

A 70-year-old woman presented with hair loss over the last 12 years with accentuated thinning on the frontal and vertex scalp. The patient’s primary care physician previously made a diagnosis of androgenetic alopecia and recommended topical minoxidil. Although the patient had a history of excess facial and body hair since young adulthood, she noted a progressive increase in the density of chest and back hair, prominent coarsening of the texture of the facial and body hair, and new facial acne in the last 3 years. Prior to these changes, the density and texture of the scalp and body hair had been stable for many years.

Although other postmenopausal females in the patient’s family displayed patterned hair loss, they did not possess coarse and dense hair on the face and trunk. Her family history was notable for ovarian cancer in her mother (in her 70s) and breast cancer in her maternal grandmother (in her 80s).

A review of systems was notable only for decreased energy. Physical examination revealed a well-appearing older woman with coarse terminal hair growth on the cheeks, submental chin, neck, chest, back, and forearms. Scalp examination indicated diffusely decreased hair density, most marked over the vertex, crown, and frontal scalp, without scale, erythema, or loss of follicular ostia (Figure 1).

Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated levels of total testosterone (106 ng/dL [reference range, <40 ng/dL]) and free testosterone (32.9 pg/mL [reference range, 1.8–10.4 pg/mL]) but a DHEA-S level within reference range, suggesting an ovarian source of androgen excess. The CA-125 level was elevated (89 U/mL [reference range, <39 U/mL]).

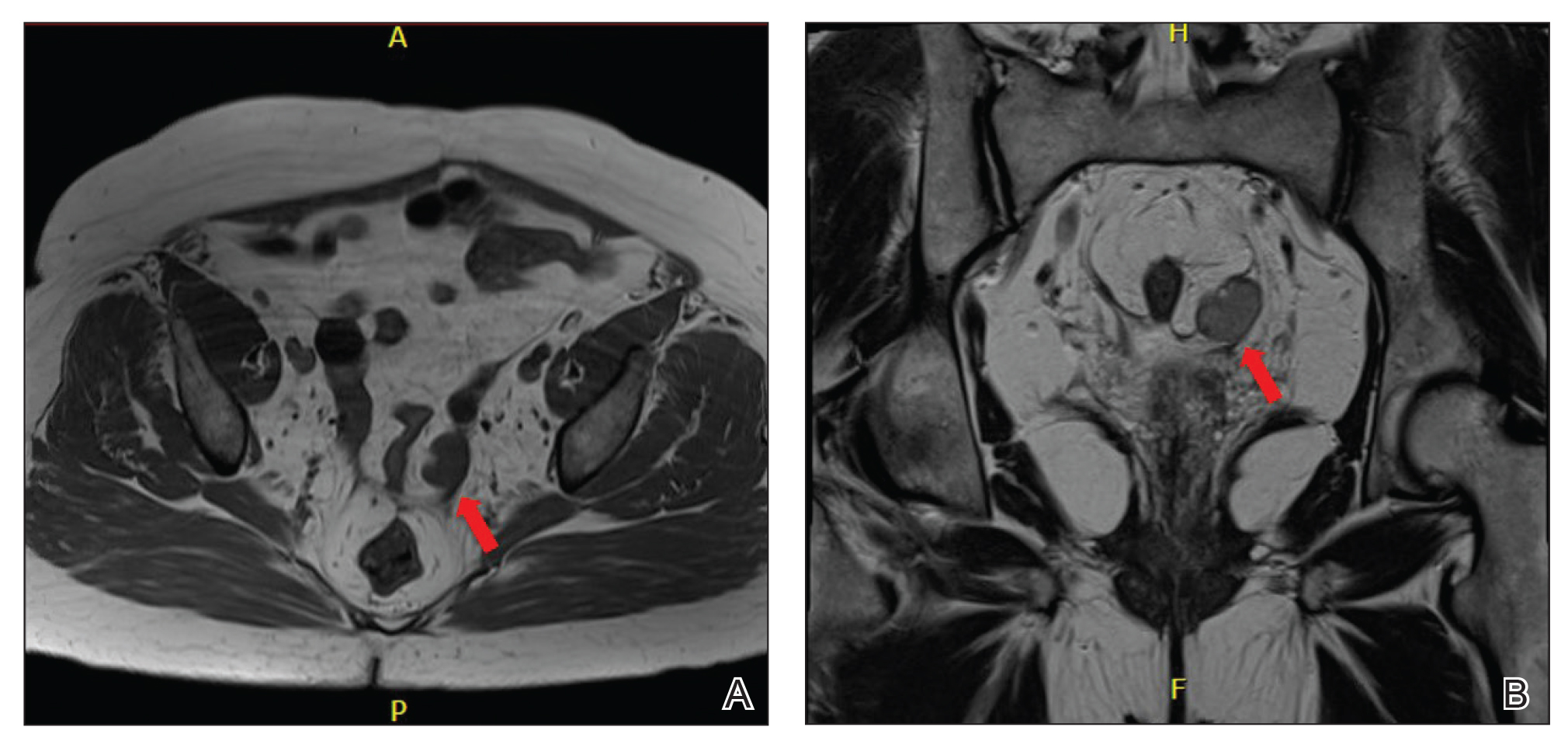

Pelvic ultrasonography was suspicious for an ovarian pathology. Follow-up pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a 2.5-cm mass abutting the left ovary (Figure 2). The patient was given a diagnosis of stage IIIA high-grade ovarian serous carcinoma with lymph node involvement. Other notable findings from the workup included a BRCA2 mutation and concurrent renal cell carcinoma. After bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, partial nephrectomy, and chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel, the testosterone level returned to within reference range and remained stable for the next 2 years of follow-up.

Female pattern hair loss is common in postmenopausal women and is a frequent concern in patients presenting to dermatology. Although most cases of androgenetic alopecia are isolated or secondary to benign conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome or nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a small minority(<1% of women presenting with signs of hyperandrogenism) have an androgen-secreting tumor.6

Rapid onset or worsening of clinical hyperandrogenism, as seen in our patient, should raise concern for pathology; serum total testosterone and DHEA-S levels should be evaluated. Abnormally elevated serum androgens are associated with malignancy; however, there is variability in the recommended cutoff levels to prompt suspicion for an androgen-producing tumor and further workup in postmenopausal women.7 In the case of testosterone elevation, classic teaching designates a testosterone level greater than 200 ng/dL as the appropriate threshold for concern, but this level is now debated. In a series of women with hyperandrogenism referred to a center for suspicion of an androgen-secreting tumor, those with a tumor had, on average, a significantly higher (260 ng/dL) testosterone level than women who had other causes (90 ng/dL)(P<.05).6 The authors of that study proposed a cutoff of 1.4 ng/mL because women in their series who had a tumor were 8.4 times more likely to have a testosterone level of 1.4 ng/mL or higher than women without a tumor. However, this cutoff was only 92% sensitive and 70% specific.6 The degree of androgen elevation is highly variable in both tumorous and benign pathologies with notable overlap, challenging the notion of a clear cutoff.

Imaging is indicated for a patient presenting with both clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism. Patients with an isolated testosterone level elevation can be evaluated with transvaginal ultrasonography; however, detection and characterization of malignancies is highly dependent on the skill of the examiner.8,9 The higher sensitivity and specificity of pelvic MRI reduces the likelihood of missing a malignancy and unnecessary surgery. Tumors too small to be visualized by MRI rarely are malignant.10

Sex cord-stromal cell tumors, despite representing fewer than 10% of ovarian tumors, are responsible for the majority of androgen-secreting malignancies. Our patient presented with clinical hyperandrogenism with an elevated testosterone level in the setting of a serous ovarian carcinoma, which is an epithelial neoplasm. Epithelial tumors are the most common type of ovarian tumor and typically are nonfunctional, though they have been reported to cause hyperandrogenism through indirect mechanisms. It is thought that both benign and malignant epithelial tumors can induce stromal hyperplasia or luteinization, leading to an increase in androgen levels.6

Due to the high prevalence of androgenetic alopecia and hirsutism in aging women, identification of androgen-secreting neoplasms by clinical presentation is challenging. A wide range of serum testosterone levels is possible at presentation, which complicates diagnosis. This case highlights the importance of correlating clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism in raising suspicion of malignancy in older women presenting with hair loss.

- Carmina E, Azziz R, Bergfeld W, et al. Female pattern hair loss and androgen excess: a report from the multidisciplinary androgen excess and PCOS committee. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:2875-2891.

- Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:e9860.

- Rothman MS, Wierman ME. How should postmenopausal androgen excess be evaluated? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;75:160-164.

- Derksen J, Nagesser SK, Meinders AE, et al. Identification of virilizing adrenal tumors in hirsute women. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:968-973.

- Kaltsas GA, Isidori AM, Kola BP, et al. The value of the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test in the differential diagnosis of hyperandrogenism in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2634-2643.

- Sarfati J, Bachelot A, Coussieu C, et al; Study Group Hyperandrogenism in Postmenopausal Women. Impact of clinical, hormonal, radiological, immunohistochemical studies on the diagnosis of postmenopausal hyperandrogenism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165:779-788.

- Glintborg D, Altinok ML, Petersen KR, et al. Total testosterone levels are often more than three times elevated in patients with androgen-secreting tumours. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2014204797.

- Iyer VR, Lee SI. MRI, CT, and PET/CT for ovarian cancer detection and adnexal lesion characterization. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:311-321.

- Rauh-Hain JA, Krivak TC, Del Carmen MG, et al. Ovarian cancer screening and early detection in the general population. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;4:15-21.

- Horta M, Cunha TM. Sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary: a comprehensive review and update for radiologists. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2015;21:277-286.

To the Editor:

Female pattern hair loss is common, and the literature suggests that up to 56% of women experience hair thinning in their lifetime, with increased prevalence in older women.1 Pathophysiology is incompletely understood and involves the nonscarring progressive miniaturization of hair follicles, causing decreased production of terminal hairs relative to more delicate vellus hairs. Because vellus hairs have a shorter anagen growth phase than terminal hairs, hair loss is expedited. Androgen excess, when present, hastens the process by inducing early transition of hair follicles from the anagen phase to the senescent telogen phase. Serum testosterone levels are within reference range in most female patients with hair loss, suggesting the presence of additional contributing factors.2

Given the high prevalence of female pattern hair loss and the harm of overlooking androgen excess and an androgen-secreting neoplasm, dermatologists must recognize indications for further evaluation. Additional signs of hyperandrogenism, such as menstrual irregularities, acne, hirsutism, anabolic appearance, voice deepening, and clitoromegaly, are reasons for concern.3 Elevated serum androgen levels also should raise suspicion of malignancy. Historically, a total testosterone level above 200 ng/dL or a dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) level greater than 700 µg/dL prompted evaluation for a tumor.4 More recent studies show that tumor-induced increases in serum androgen levels are highly variable, challenging the utility of these cutoffs.5

A 70-year-old woman presented with hair loss over the last 12 years with accentuated thinning on the frontal and vertex scalp. The patient’s primary care physician previously made a diagnosis of androgenetic alopecia and recommended topical minoxidil. Although the patient had a history of excess facial and body hair since young adulthood, she noted a progressive increase in the density of chest and back hair, prominent coarsening of the texture of the facial and body hair, and new facial acne in the last 3 years. Prior to these changes, the density and texture of the scalp and body hair had been stable for many years.

Although other postmenopausal females in the patient’s family displayed patterned hair loss, they did not possess coarse and dense hair on the face and trunk. Her family history was notable for ovarian cancer in her mother (in her 70s) and breast cancer in her maternal grandmother (in her 80s).

A review of systems was notable only for decreased energy. Physical examination revealed a well-appearing older woman with coarse terminal hair growth on the cheeks, submental chin, neck, chest, back, and forearms. Scalp examination indicated diffusely decreased hair density, most marked over the vertex, crown, and frontal scalp, without scale, erythema, or loss of follicular ostia (Figure 1).

Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated levels of total testosterone (106 ng/dL [reference range, <40 ng/dL]) and free testosterone (32.9 pg/mL [reference range, 1.8–10.4 pg/mL]) but a DHEA-S level within reference range, suggesting an ovarian source of androgen excess. The CA-125 level was elevated (89 U/mL [reference range, <39 U/mL]).

Pelvic ultrasonography was suspicious for an ovarian pathology. Follow-up pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a 2.5-cm mass abutting the left ovary (Figure 2). The patient was given a diagnosis of stage IIIA high-grade ovarian serous carcinoma with lymph node involvement. Other notable findings from the workup included a BRCA2 mutation and concurrent renal cell carcinoma. After bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, partial nephrectomy, and chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel, the testosterone level returned to within reference range and remained stable for the next 2 years of follow-up.

Female pattern hair loss is common in postmenopausal women and is a frequent concern in patients presenting to dermatology. Although most cases of androgenetic alopecia are isolated or secondary to benign conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome or nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a small minority(<1% of women presenting with signs of hyperandrogenism) have an androgen-secreting tumor.6

Rapid onset or worsening of clinical hyperandrogenism, as seen in our patient, should raise concern for pathology; serum total testosterone and DHEA-S levels should be evaluated. Abnormally elevated serum androgens are associated with malignancy; however, there is variability in the recommended cutoff levels to prompt suspicion for an androgen-producing tumor and further workup in postmenopausal women.7 In the case of testosterone elevation, classic teaching designates a testosterone level greater than 200 ng/dL as the appropriate threshold for concern, but this level is now debated. In a series of women with hyperandrogenism referred to a center for suspicion of an androgen-secreting tumor, those with a tumor had, on average, a significantly higher (260 ng/dL) testosterone level than women who had other causes (90 ng/dL)(P<.05).6 The authors of that study proposed a cutoff of 1.4 ng/mL because women in their series who had a tumor were 8.4 times more likely to have a testosterone level of 1.4 ng/mL or higher than women without a tumor. However, this cutoff was only 92% sensitive and 70% specific.6 The degree of androgen elevation is highly variable in both tumorous and benign pathologies with notable overlap, challenging the notion of a clear cutoff.

Imaging is indicated for a patient presenting with both clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism. Patients with an isolated testosterone level elevation can be evaluated with transvaginal ultrasonography; however, detection and characterization of malignancies is highly dependent on the skill of the examiner.8,9 The higher sensitivity and specificity of pelvic MRI reduces the likelihood of missing a malignancy and unnecessary surgery. Tumors too small to be visualized by MRI rarely are malignant.10

Sex cord-stromal cell tumors, despite representing fewer than 10% of ovarian tumors, are responsible for the majority of androgen-secreting malignancies. Our patient presented with clinical hyperandrogenism with an elevated testosterone level in the setting of a serous ovarian carcinoma, which is an epithelial neoplasm. Epithelial tumors are the most common type of ovarian tumor and typically are nonfunctional, though they have been reported to cause hyperandrogenism through indirect mechanisms. It is thought that both benign and malignant epithelial tumors can induce stromal hyperplasia or luteinization, leading to an increase in androgen levels.6

Due to the high prevalence of androgenetic alopecia and hirsutism in aging women, identification of androgen-secreting neoplasms by clinical presentation is challenging. A wide range of serum testosterone levels is possible at presentation, which complicates diagnosis. This case highlights the importance of correlating clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism in raising suspicion of malignancy in older women presenting with hair loss.

To the Editor:

Female pattern hair loss is common, and the literature suggests that up to 56% of women experience hair thinning in their lifetime, with increased prevalence in older women.1 Pathophysiology is incompletely understood and involves the nonscarring progressive miniaturization of hair follicles, causing decreased production of terminal hairs relative to more delicate vellus hairs. Because vellus hairs have a shorter anagen growth phase than terminal hairs, hair loss is expedited. Androgen excess, when present, hastens the process by inducing early transition of hair follicles from the anagen phase to the senescent telogen phase. Serum testosterone levels are within reference range in most female patients with hair loss, suggesting the presence of additional contributing factors.2

Given the high prevalence of female pattern hair loss and the harm of overlooking androgen excess and an androgen-secreting neoplasm, dermatologists must recognize indications for further evaluation. Additional signs of hyperandrogenism, such as menstrual irregularities, acne, hirsutism, anabolic appearance, voice deepening, and clitoromegaly, are reasons for concern.3 Elevated serum androgen levels also should raise suspicion of malignancy. Historically, a total testosterone level above 200 ng/dL or a dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S) level greater than 700 µg/dL prompted evaluation for a tumor.4 More recent studies show that tumor-induced increases in serum androgen levels are highly variable, challenging the utility of these cutoffs.5

A 70-year-old woman presented with hair loss over the last 12 years with accentuated thinning on the frontal and vertex scalp. The patient’s primary care physician previously made a diagnosis of androgenetic alopecia and recommended topical minoxidil. Although the patient had a history of excess facial and body hair since young adulthood, she noted a progressive increase in the density of chest and back hair, prominent coarsening of the texture of the facial and body hair, and new facial acne in the last 3 years. Prior to these changes, the density and texture of the scalp and body hair had been stable for many years.

Although other postmenopausal females in the patient’s family displayed patterned hair loss, they did not possess coarse and dense hair on the face and trunk. Her family history was notable for ovarian cancer in her mother (in her 70s) and breast cancer in her maternal grandmother (in her 80s).

A review of systems was notable only for decreased energy. Physical examination revealed a well-appearing older woman with coarse terminal hair growth on the cheeks, submental chin, neck, chest, back, and forearms. Scalp examination indicated diffusely decreased hair density, most marked over the vertex, crown, and frontal scalp, without scale, erythema, or loss of follicular ostia (Figure 1).

Laboratory evaluation revealed elevated levels of total testosterone (106 ng/dL [reference range, <40 ng/dL]) and free testosterone (32.9 pg/mL [reference range, 1.8–10.4 pg/mL]) but a DHEA-S level within reference range, suggesting an ovarian source of androgen excess. The CA-125 level was elevated (89 U/mL [reference range, <39 U/mL]).

Pelvic ultrasonography was suspicious for an ovarian pathology. Follow-up pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a 2.5-cm mass abutting the left ovary (Figure 2). The patient was given a diagnosis of stage IIIA high-grade ovarian serous carcinoma with lymph node involvement. Other notable findings from the workup included a BRCA2 mutation and concurrent renal cell carcinoma. After bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, partial nephrectomy, and chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel, the testosterone level returned to within reference range and remained stable for the next 2 years of follow-up.

Female pattern hair loss is common in postmenopausal women and is a frequent concern in patients presenting to dermatology. Although most cases of androgenetic alopecia are isolated or secondary to benign conditions, such as polycystic ovary syndrome or nonclassic congenital adrenal hyperplasia, a small minority(<1% of women presenting with signs of hyperandrogenism) have an androgen-secreting tumor.6

Rapid onset or worsening of clinical hyperandrogenism, as seen in our patient, should raise concern for pathology; serum total testosterone and DHEA-S levels should be evaluated. Abnormally elevated serum androgens are associated with malignancy; however, there is variability in the recommended cutoff levels to prompt suspicion for an androgen-producing tumor and further workup in postmenopausal women.7 In the case of testosterone elevation, classic teaching designates a testosterone level greater than 200 ng/dL as the appropriate threshold for concern, but this level is now debated. In a series of women with hyperandrogenism referred to a center for suspicion of an androgen-secreting tumor, those with a tumor had, on average, a significantly higher (260 ng/dL) testosterone level than women who had other causes (90 ng/dL)(P<.05).6 The authors of that study proposed a cutoff of 1.4 ng/mL because women in their series who had a tumor were 8.4 times more likely to have a testosterone level of 1.4 ng/mL or higher than women without a tumor. However, this cutoff was only 92% sensitive and 70% specific.6 The degree of androgen elevation is highly variable in both tumorous and benign pathologies with notable overlap, challenging the notion of a clear cutoff.

Imaging is indicated for a patient presenting with both clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism. Patients with an isolated testosterone level elevation can be evaluated with transvaginal ultrasonography; however, detection and characterization of malignancies is highly dependent on the skill of the examiner.8,9 The higher sensitivity and specificity of pelvic MRI reduces the likelihood of missing a malignancy and unnecessary surgery. Tumors too small to be visualized by MRI rarely are malignant.10

Sex cord-stromal cell tumors, despite representing fewer than 10% of ovarian tumors, are responsible for the majority of androgen-secreting malignancies. Our patient presented with clinical hyperandrogenism with an elevated testosterone level in the setting of a serous ovarian carcinoma, which is an epithelial neoplasm. Epithelial tumors are the most common type of ovarian tumor and typically are nonfunctional, though they have been reported to cause hyperandrogenism through indirect mechanisms. It is thought that both benign and malignant epithelial tumors can induce stromal hyperplasia or luteinization, leading to an increase in androgen levels.6

Due to the high prevalence of androgenetic alopecia and hirsutism in aging women, identification of androgen-secreting neoplasms by clinical presentation is challenging. A wide range of serum testosterone levels is possible at presentation, which complicates diagnosis. This case highlights the importance of correlating clinical and biochemical hyperandrogenism in raising suspicion of malignancy in older women presenting with hair loss.

- Carmina E, Azziz R, Bergfeld W, et al. Female pattern hair loss and androgen excess: a report from the multidisciplinary androgen excess and PCOS committee. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:2875-2891.

- Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:e9860.

- Rothman MS, Wierman ME. How should postmenopausal androgen excess be evaluated? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;75:160-164.

- Derksen J, Nagesser SK, Meinders AE, et al. Identification of virilizing adrenal tumors in hirsute women. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:968-973.

- Kaltsas GA, Isidori AM, Kola BP, et al. The value of the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test in the differential diagnosis of hyperandrogenism in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2634-2643.

- Sarfati J, Bachelot A, Coussieu C, et al; Study Group Hyperandrogenism in Postmenopausal Women. Impact of clinical, hormonal, radiological, immunohistochemical studies on the diagnosis of postmenopausal hyperandrogenism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165:779-788.

- Glintborg D, Altinok ML, Petersen KR, et al. Total testosterone levels are often more than three times elevated in patients with androgen-secreting tumours. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2014204797.

- Iyer VR, Lee SI. MRI, CT, and PET/CT for ovarian cancer detection and adnexal lesion characterization. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:311-321.

- Rauh-Hain JA, Krivak TC, Del Carmen MG, et al. Ovarian cancer screening and early detection in the general population. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;4:15-21.

- Horta M, Cunha TM. Sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary: a comprehensive review and update for radiologists. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2015;21:277-286.

- Carmina E, Azziz R, Bergfeld W, et al. Female pattern hair loss and androgen excess: a report from the multidisciplinary androgen excess and PCOS committee. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:2875-2891.

- Herskovitz I, Tosti A. Female pattern hair loss. Int J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;11:e9860.

- Rothman MS, Wierman ME. How should postmenopausal androgen excess be evaluated? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2011;75:160-164.

- Derksen J, Nagesser SK, Meinders AE, et al. Identification of virilizing adrenal tumors in hirsute women. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:968-973.

- Kaltsas GA, Isidori AM, Kola BP, et al. The value of the low-dose dexamethasone suppression test in the differential diagnosis of hyperandrogenism in women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:2634-2643.

- Sarfati J, Bachelot A, Coussieu C, et al; Study Group Hyperandrogenism in Postmenopausal Women. Impact of clinical, hormonal, radiological, immunohistochemical studies on the diagnosis of postmenopausal hyperandrogenism. Eur J Endocrinol. 2011;165:779-788.

- Glintborg D, Altinok ML, Petersen KR, et al. Total testosterone levels are often more than three times elevated in patients with androgen-secreting tumours. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2014204797.

- Iyer VR, Lee SI. MRI, CT, and PET/CT for ovarian cancer detection and adnexal lesion characterization. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:311-321.

- Rauh-Hain JA, Krivak TC, Del Carmen MG, et al. Ovarian cancer screening and early detection in the general population. Rev Obstet Gynecol. 2011;4:15-21.

- Horta M, Cunha TM. Sex cord-stromal tumors of the ovary: a comprehensive review and update for radiologists. Diagn Interv Radiol. 2015;21:277-286.

Practice Points

- Laboratory assessment for possible androgen excess should be performed in patients with female pattern hair loss and include baseline serum total testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate.

- Rapid onset or worsening of clinical hyperandrogenism should raise suspicion of malignancy.

- Transvaginal ultrasonography and possible pelvic magnetic resonance imaging are indicated for patients with clinical hyperandrogenism and an isolated testosterone level elevation.

Miscommunication With Dermatology Patients: Are We Speaking the Same Language?

I was a third-year medical student, dutifully reviewing discharge instructions with a patient and her family. The patient’s adult daughter asked, “What about that diet you put her on?” As they looked at me quizzically, I looked back equally confused, until it clicked: We needed to talk about the word diet. In everyday conversation, diet generally is understood to mean restriction of food to lose weight, which is what the family hoped would be prescribed for their obese family member. I needed to tell them that I was sorry for the misunderstanding. If they overheard us “ordering a diet,” we simply meant providing trays of hospital food.

We become so familiar with the language of our profession that we do not remember it may be foreign to our patients. In dermatology, we are aware that our specialty is full of esoteric jargon and complex concepts that need to be carefully explained to our patients in simpler terms. But since that incident in medical school, I have been interested in the more insidious potential misunderstandings that can arise from words as seemingly simple as diet. There are many examples in dermatology, particularly in the way we prescribe topical therapy and use trade names.

Topical Therapy

Instructions for systemic medications may be as simple as “take 1 pill twice daily.” Prescriptions for topical medications can be written with an equally simple patient signature such as “apply twice daily to affected area,” but the simplicity is deceptive. The direction to “apply” may seem intuitive to the prescriber, but we do not always specify the amount. Sunscreen, for example, is notoriously underapplied when the actual amount of product needed for protection is not demonstrated.1 One study of new dermatology patients given a prescription for a new topical medication found that the majority of patients underdosed.2

Determination of an “affected area,” regardless of whether the site is indicated, can be even less straightforward. In acne treatment, the affected area is the whole region prone to acne breakouts, whereas in psoriasis it may be discrete psoriatic plaques. We may believe our explanations are perfectly clear, but we have all seen patients spot treating their acne or psoriasis patients covering entire territories of normal skin with topical steroids, despite our education. One study of eczema action plans found that there was considerable variability in the way different providers described disease flares that require treatment. For example, redness was only used as a descriptor of an eczema flare in 68.2% of eczema action plans studied.3 Ensuring our patients understand our criteria for skin requiring topical treatment may mean the difference between treatment success and failure and also may help to avoid unnecessary side effects.

Adherence to topical medication regimens is poor, and inadequate patient education is only one factor.4,5 One study found that more than one-third of new prescriptions for topical medications were never even filled.6 However, improving our communication about application of topical drugs is one way we must address the complicated issue of adherence.

Trade Names

In dermatology, we often use trade names to refer to our medications, even if we do not intend to reference the brand name of the drug specifically. We may tell a patient to use Lidex (Medicis Pharmaceutical Corporation) for her hands but then send an escript to her pharmacy for fluocinonide. Trade names are designed to roll off the tongue, in contrast to the unwieldy, clumsily long generic names assigned to many of our medications.

Substituting trade names may facilitate more natural conversation to promote patient understanding in some cases; however, there are pitfalls associated with this habit. First, we may be doing our patients a disservice if we do not clarify when it would be acceptable to substitute with the generic when the medication is available over-the-counter. If we decide to treat with Rogaine (Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc) but do not suggest the option of purchasing the generic minoxidil, the patient could be unnecessarily overpaying for a brand name by following our instructions.

Conversely, there are scenarios in which the use of a brand name is actually not specific enough. A patient once told me she was using Differin (Galderma Laboratories, LP) as discussed at her prior visit, but she revealed she was washing it off after application. I initially assumed she misunderstood that adapalene was a gel to be applied and left on. After additional questioning, however, it became clear that she purchased the Differin gentle cleanser, a nonmedicated facial wash, rather than the retinoid we had intended for her. I had not considered that Differin would market an entire line of skin care products but now realize we must be cautious using Differin and adapalene interchangeably. Other examples include popular over-the-counter antihistamine brands such as Allegra (Chattem, a Sanofi company) or Benadryl (Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc) that market multiple products with different active ingredients.

Final Thoughts

The smooth transfer of information between physician and patient is key to a healthy therapeutic relationship. In residency and throughout our careers, we will continue to develop and refine our communication skills to best serve our patients. We should pay particular attention to the unexpected and surprising ways in which we fail to adequately communicate, make note of these patterns, and share with our colleagues so that we can all learn from our collective experiences.

- Schneider, J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Storm A, Benfeldt E, Andersen SE, et al. A prospective study of patient adherence to topical treatments: 95% of patients underdose. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:975-980.

- Stringer T, Yin HS, Gittler J, et al. The readability, suitability, and content features of eczema action plans in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:800-807.

- Hougeir FG, Cook-Bolden FE, Rodriguez D, et al. Critical considerations on optimizing topical corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8(suppl 1):S2-S14.

- Savary J, Ortonne JP, Aractingi S. The right dose in the right place: an overview of current prescription, instruction and application modalities for topical psoriasis treatments. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:14-17.

- Storm A, Anderson SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

I was a third-year medical student, dutifully reviewing discharge instructions with a patient and her family. The patient’s adult daughter asked, “What about that diet you put her on?” As they looked at me quizzically, I looked back equally confused, until it clicked: We needed to talk about the word diet. In everyday conversation, diet generally is understood to mean restriction of food to lose weight, which is what the family hoped would be prescribed for their obese family member. I needed to tell them that I was sorry for the misunderstanding. If they overheard us “ordering a diet,” we simply meant providing trays of hospital food.

We become so familiar with the language of our profession that we do not remember it may be foreign to our patients. In dermatology, we are aware that our specialty is full of esoteric jargon and complex concepts that need to be carefully explained to our patients in simpler terms. But since that incident in medical school, I have been interested in the more insidious potential misunderstandings that can arise from words as seemingly simple as diet. There are many examples in dermatology, particularly in the way we prescribe topical therapy and use trade names.

Topical Therapy

Instructions for systemic medications may be as simple as “take 1 pill twice daily.” Prescriptions for topical medications can be written with an equally simple patient signature such as “apply twice daily to affected area,” but the simplicity is deceptive. The direction to “apply” may seem intuitive to the prescriber, but we do not always specify the amount. Sunscreen, for example, is notoriously underapplied when the actual amount of product needed for protection is not demonstrated.1 One study of new dermatology patients given a prescription for a new topical medication found that the majority of patients underdosed.2

Determination of an “affected area,” regardless of whether the site is indicated, can be even less straightforward. In acne treatment, the affected area is the whole region prone to acne breakouts, whereas in psoriasis it may be discrete psoriatic plaques. We may believe our explanations are perfectly clear, but we have all seen patients spot treating their acne or psoriasis patients covering entire territories of normal skin with topical steroids, despite our education. One study of eczema action plans found that there was considerable variability in the way different providers described disease flares that require treatment. For example, redness was only used as a descriptor of an eczema flare in 68.2% of eczema action plans studied.3 Ensuring our patients understand our criteria for skin requiring topical treatment may mean the difference between treatment success and failure and also may help to avoid unnecessary side effects.

Adherence to topical medication regimens is poor, and inadequate patient education is only one factor.4,5 One study found that more than one-third of new prescriptions for topical medications were never even filled.6 However, improving our communication about application of topical drugs is one way we must address the complicated issue of adherence.

Trade Names

In dermatology, we often use trade names to refer to our medications, even if we do not intend to reference the brand name of the drug specifically. We may tell a patient to use Lidex (Medicis Pharmaceutical Corporation) for her hands but then send an escript to her pharmacy for fluocinonide. Trade names are designed to roll off the tongue, in contrast to the unwieldy, clumsily long generic names assigned to many of our medications.

Substituting trade names may facilitate more natural conversation to promote patient understanding in some cases; however, there are pitfalls associated with this habit. First, we may be doing our patients a disservice if we do not clarify when it would be acceptable to substitute with the generic when the medication is available over-the-counter. If we decide to treat with Rogaine (Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc) but do not suggest the option of purchasing the generic minoxidil, the patient could be unnecessarily overpaying for a brand name by following our instructions.

Conversely, there are scenarios in which the use of a brand name is actually not specific enough. A patient once told me she was using Differin (Galderma Laboratories, LP) as discussed at her prior visit, but she revealed she was washing it off after application. I initially assumed she misunderstood that adapalene was a gel to be applied and left on. After additional questioning, however, it became clear that she purchased the Differin gentle cleanser, a nonmedicated facial wash, rather than the retinoid we had intended for her. I had not considered that Differin would market an entire line of skin care products but now realize we must be cautious using Differin and adapalene interchangeably. Other examples include popular over-the-counter antihistamine brands such as Allegra (Chattem, a Sanofi company) or Benadryl (Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc) that market multiple products with different active ingredients.

Final Thoughts

The smooth transfer of information between physician and patient is key to a healthy therapeutic relationship. In residency and throughout our careers, we will continue to develop and refine our communication skills to best serve our patients. We should pay particular attention to the unexpected and surprising ways in which we fail to adequately communicate, make note of these patterns, and share with our colleagues so that we can all learn from our collective experiences.

I was a third-year medical student, dutifully reviewing discharge instructions with a patient and her family. The patient’s adult daughter asked, “What about that diet you put her on?” As they looked at me quizzically, I looked back equally confused, until it clicked: We needed to talk about the word diet. In everyday conversation, diet generally is understood to mean restriction of food to lose weight, which is what the family hoped would be prescribed for their obese family member. I needed to tell them that I was sorry for the misunderstanding. If they overheard us “ordering a diet,” we simply meant providing trays of hospital food.

We become so familiar with the language of our profession that we do not remember it may be foreign to our patients. In dermatology, we are aware that our specialty is full of esoteric jargon and complex concepts that need to be carefully explained to our patients in simpler terms. But since that incident in medical school, I have been interested in the more insidious potential misunderstandings that can arise from words as seemingly simple as diet. There are many examples in dermatology, particularly in the way we prescribe topical therapy and use trade names.

Topical Therapy

Instructions for systemic medications may be as simple as “take 1 pill twice daily.” Prescriptions for topical medications can be written with an equally simple patient signature such as “apply twice daily to affected area,” but the simplicity is deceptive. The direction to “apply” may seem intuitive to the prescriber, but we do not always specify the amount. Sunscreen, for example, is notoriously underapplied when the actual amount of product needed for protection is not demonstrated.1 One study of new dermatology patients given a prescription for a new topical medication found that the majority of patients underdosed.2

Determination of an “affected area,” regardless of whether the site is indicated, can be even less straightforward. In acne treatment, the affected area is the whole region prone to acne breakouts, whereas in psoriasis it may be discrete psoriatic plaques. We may believe our explanations are perfectly clear, but we have all seen patients spot treating their acne or psoriasis patients covering entire territories of normal skin with topical steroids, despite our education. One study of eczema action plans found that there was considerable variability in the way different providers described disease flares that require treatment. For example, redness was only used as a descriptor of an eczema flare in 68.2% of eczema action plans studied.3 Ensuring our patients understand our criteria for skin requiring topical treatment may mean the difference between treatment success and failure and also may help to avoid unnecessary side effects.

Adherence to topical medication regimens is poor, and inadequate patient education is only one factor.4,5 One study found that more than one-third of new prescriptions for topical medications were never even filled.6 However, improving our communication about application of topical drugs is one way we must address the complicated issue of adherence.

Trade Names

In dermatology, we often use trade names to refer to our medications, even if we do not intend to reference the brand name of the drug specifically. We may tell a patient to use Lidex (Medicis Pharmaceutical Corporation) for her hands but then send an escript to her pharmacy for fluocinonide. Trade names are designed to roll off the tongue, in contrast to the unwieldy, clumsily long generic names assigned to many of our medications.

Substituting trade names may facilitate more natural conversation to promote patient understanding in some cases; however, there are pitfalls associated with this habit. First, we may be doing our patients a disservice if we do not clarify when it would be acceptable to substitute with the generic when the medication is available over-the-counter. If we decide to treat with Rogaine (Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc) but do not suggest the option of purchasing the generic minoxidil, the patient could be unnecessarily overpaying for a brand name by following our instructions.

Conversely, there are scenarios in which the use of a brand name is actually not specific enough. A patient once told me she was using Differin (Galderma Laboratories, LP) as discussed at her prior visit, but she revealed she was washing it off after application. I initially assumed she misunderstood that adapalene was a gel to be applied and left on. After additional questioning, however, it became clear that she purchased the Differin gentle cleanser, a nonmedicated facial wash, rather than the retinoid we had intended for her. I had not considered that Differin would market an entire line of skin care products but now realize we must be cautious using Differin and adapalene interchangeably. Other examples include popular over-the-counter antihistamine brands such as Allegra (Chattem, a Sanofi company) or Benadryl (Johnson & Johnson Consumer Inc) that market multiple products with different active ingredients.

Final Thoughts

The smooth transfer of information between physician and patient is key to a healthy therapeutic relationship. In residency and throughout our careers, we will continue to develop and refine our communication skills to best serve our patients. We should pay particular attention to the unexpected and surprising ways in which we fail to adequately communicate, make note of these patterns, and share with our colleagues so that we can all learn from our collective experiences.

- Schneider, J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Storm A, Benfeldt E, Andersen SE, et al. A prospective study of patient adherence to topical treatments: 95% of patients underdose. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:975-980.

- Stringer T, Yin HS, Gittler J, et al. The readability, suitability, and content features of eczema action plans in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:800-807.

- Hougeir FG, Cook-Bolden FE, Rodriguez D, et al. Critical considerations on optimizing topical corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8(suppl 1):S2-S14.

- Savary J, Ortonne JP, Aractingi S. The right dose in the right place: an overview of current prescription, instruction and application modalities for topical psoriasis treatments. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:14-17.

- Storm A, Anderson SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

- Schneider, J. The teaspoon rule of applying sunscreen. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:838-839.

- Storm A, Benfeldt E, Andersen SE, et al. A prospective study of patient adherence to topical treatments: 95% of patients underdose. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:975-980.

- Stringer T, Yin HS, Gittler J, et al. The readability, suitability, and content features of eczema action plans in the United States. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35:800-807.

- Hougeir FG, Cook-Bolden FE, Rodriguez D, et al. Critical considerations on optimizing topical corticosteroid therapy. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2015;8(suppl 1):S2-S14.

- Savary J, Ortonne JP, Aractingi S. The right dose in the right place: an overview of current prescription, instruction and application modalities for topical psoriasis treatments. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2005;19:14-17.

- Storm A, Anderson SE, Benfeldt E, et al. One in 3 prescriptions are never redeemed: primary nonadherence in an outpatient clinic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:27-33.

Resident Pearl

- It is not just the esoteric jargon and complex pathophysiologic concepts in dermatology that can challenge effective communication with our patients. We face potential for misunderstanding even in situations that may seem straightforward. Vigilance in avoiding ambiguity in all our exchanges with patients can help foster therapeutic relationships and optimize patient care.