User login

Implant Designs in Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty

Before 1990, a considerable number of revisions were performed, largely for implant-associated failures, in the first few years after index primary knee arthroplasties.1,2 Since then, surgeons, manufacturers, and hospitals have collaborated to improve implant designs, techniques, and care guidelines.3,4 Despite the substantial improvements in designs, which led to implant longevity of more than 15 years in many cases, these devices still have limited life spans. Large studies have estimated that the risk for revision required after primary knee arthroplasty ranges from as low as 5% at 15 years to up to 9% at 10 years.4,5

The surgical goals of revision total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are to obtain stable fixation of the prosthesis to host bone, to obtain a stable range of motion compatible with the patient’s activities of daily living, and to achieve these goals while using the smallest amount of prosthetic augments and constraint so that the soft tissues may share in load transfer.6 As prosthetic constraint increases, the soft tissues participate less in load sharing, and increasing stresses are put on the implant–bone interface, which further increases the risk for early implant loosening.7 Hence, as characteristics of a revision implant become more constrained, there is often a higher rate of aseptic loosening expected.8

Controversy remains regarding the ideal implant type for revision TKA. To ensure the success of revision surgery and to reduce the risks for postoperative dissatisfaction, complications, and re-revision, orthopedists must understand the types of revision implant designs available, particularly as each has its own indications and potential complications.

In this article, we review the classification systems used for revision TKA as well as the types of prosthetic designs that can be used: posterior stabilized, nonlinked constrained, rotating hinge, and modular segmental.

1. Classification of bone loss and soft-tissue integrity

To further understand revision TKA, we must consider the complexity level of these cases, particularly by evaluating degree of bone loss and soft-tissue deficiency. The most accepted way to assess bone loss both before and during surgery is to use the AORI (Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute) classification system.9 Bone loss can be classified into 3 types: I, in which metaphyseal bone is intact and small bone defects do not compromise component stability; II, in which metaphyseal bone is damaged and cancellous bone loss requires cement fill, augments, or bone graft; and III, in which metaphyseal bone is deficient, and lost bone comprises a major portion of condyle or plateau and occasionally requires bone grafts or custom implants (Table 1). These patterns of bone loss are occasionally associated with detachment of the collateral ligament or patellar tendon.

In addition to understanding bone loss in revision TKA, surgeons must be aware of soft-tissue deficiencies (eg, collateral ligaments, extensor mechanism), which also influence type and amount of prosthesis constraint. Specifically, constraint choice depends on amount of bone loss and on the condition of stabilizing tissues, such as the collateral ligaments. Under conditions of minimal bone loss and intact peripheral ligaments, a less constrained device, such as a primary posterior stabilized system, can be considered. When ligaments are present but insufficient, a semiconstrained device is recommended. In the presence of medial collateral ligament attenuation or complete medial or lateral collateral ligament dysfunction, a fully constrained prosthesis is required.8 Therefore, amount of bone loss or soft-tissue deficiency often dictates which prosthesis to use.

For radiographic classification, the Knee Society roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system10 has been implemented to allow for uniform reporting of radiographic results and to ensure adequate preoperative planning and postoperative assessment of component alignment. This system incorporates the evaluation of alignment in the coronal, sagittal, and patellofemoral planes and assesses radiolucency using zones dividing the implant–bone interface into segments to allow for easier classification of areas of lucency. More recently, a modified version of the Knee Society system was constructed.11 This modification simplifies zone classifications and accommodates more complex revision knee designs and stem extensions.

2. Posterior stabilized designs

Cruciate-retaining prostheses are seldom applicable in the revision TKA setting because of frequent damage to the posterior cruciate ligament, except in the case of simple polyethylene exchanges or, potentially, revisions of failed unicompartmental TKAs. Thus, posterior stabilized designs are the first-line choice for revision TKA (Figure 1). These prostheses are indicated only when the posterior cruciate ligament is incompetent and in the setting of adequate flexion and extension and medial and lateral collateral ligament balancing.

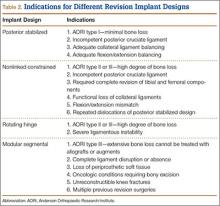

However, studies have shown that posterior stabilized TKAs have a limited role in revision TKAs, as the amount of ligamentous and bony damage is often underestimated in these patients, and use of a primary implant in a revision setting often requires additional augments, all of which may have contributed to the high failure rate. Thus, this design should be used only when the patient has adequate bone stock (AORI type I) and collateral ligament tension. This situation further emphasizes the importance of performing intraoperative testing for ligamentous balance and bone deficit evaluation in order to determine the most appropriate implant (Table 2).

3. Nonlinked constrained designs

Nonlinked constrained (condylar constrained) designs are the devices most commonly used for revision TKAs (>50% of revision knees). These prostheses provide increased articular constraint, which is required in patients with persistent instability, despite appropriate soft-tissue balancing. Increased articular constraint allows for more knee stability by providing progressive varus-valgus, coronal, and rotational stability with the aid of taller and wider tibial posts.12 Specifically, these implants incorporate a tibial post that fits closely between the femoral condyles, allowing for less motion compared with a standard posterior stabilized design.12

In addition, these designs may be used with augments, stems, and allografts when bone loss is more substantial. In particular, stem extensions allow for load distribution to the diaphyseal regions of the tibia and femur and thereby aid in reducing the increased stress at the bone–implant interface, which is a common concern with these implants. However, these extensions cost more, require intramedullary invasion, and are associated with higher rates of leg and thigh pain.12

These prostheses are often implicated in cases involving a high degree of bone loss (eg, AORI type II or III). They are ideally used in cases in which complete revision of both tibial and femoral components is needed and are indicated in cases of incompetent posterior cruciate ligament, partial functional loss of medial or lateral collateral ligaments, or flexion-extension mismatch.13 Furthermore, use of a constrained prosthesis is recommended in the setting of varus or valgus instability, or repeated dislocations of a posterior stabilized design (Table 2).

Ten-year survivorship ranges from 85% to 96%, but this is substantially lower than the 95% to 96% for condylar constrained prostheses used in primary TKAs.14-17 Moreover, the large discrepancy between survivorship of primary TKA and revision TKA with a constrained prosthesis further affirms that the complexity of revision surgery, rather than the prosthesis used, may have more deleterious effects on outcomes. However, surgeons must be aware that increased constraint leads to increased stress on the prosthetic interfaces with associated aseptic loosening and early failure, and this continues to be a legitimate concern.

4. Rotating hinge designs

Many patients who undergo revision TKA can be managed with a posterior stabilizing or nonlinked constrained design. However, in patients who present with severe ligamentous instability and bone loss (AORI type II or III), a rotating hinge prostheses, or highly constrained device, is often recommended (Figure 2).18 By using a rotating mobile-bearing platform, this prosthesis permits axial rotation through a metal-reinforced polyethylene-post articulation in the tibial tray. In addition, it involves use of modular diaphyseal-engaging stems and diaphyseal sleeves, which allow for the bypass of bony defects and areas of bone loss (Table 2).

However, the rigid biomechanics of hinged prostheses is associated with increased risk for aseptic loosening (aseptic 10-year survival, 60%-80%), imparted by the transfer of stresses across the bone. The higher risk for early loosening, osteolysis, and excessive wear—caused by the highly restricted biomechanics of early generations of fixed hinged designs—has led to the development of new devices with mobile mechanics. Prosthetic designs have been improved with an added rotational axis to reduce torsional stress, a patellar resurfacing option, and better stem fixation and patellofemoral kinematics. Overall, these are aimed to improve rates of instability and aseptic loosening, with promising results demonstrated in the literature.

5. Modular segmental arthroplasty designs

Segmental arthroplasty prostheses, which typically are end-of-the-line revision TKA options, are applicable only in cases of extensive bone loss (more than can be treated with allografts or augments; AORI type 3), complete ligamentous disruption/absence, loss of periprosthetic soft tissue, and multiple previous revision procedures (Figure 3). Despite the limited indications for these prostheses, they yield quick return to function without graft nonunion or resorption, and they augment ingrowth/ongrowth. Furthermore, the next surgical option could be fusion or amputation. When failures were specifically evaluated for aseptic loosening across 4 studies, the survival rate ranged from 83% to 99.5%, with the most frequent complication being infection (up to 33% in one series).6,19-21

The major roles for segmental arthroplasty prostheses in primary TKAs are in the setting of oncologic conditions that require bony excision, or unreconstuctable fractures about the knee. Used after ancillary metastatic disease, these prostheses demonstrate positive results, according to several reports.22,23 In the setting of revision TKA, however, these prostheses should be used only when other surgical options are unfeasible, given the high risk for infection and the re-revision rates. Currently, revision TKAs with tumor prostheses have a high failure rate (up to 50%) because of the extensive surgery and the lack of bony and soft-tissue support (Table 2).

Conclusion

Orthopedists performing revision TKAs must consider bone stock and remaining ligament stability. In particular, they should choose implants for least constraint and adequate knee stability, as these are essential in minimizing the stresses on the implant–bone interface. Ultimately, functional outcomes, survivorship, and postoperative satisfaction determine the success of these designs. However, predictors of outcomes of revision surgery are often multifactorial, and surgeons must also consider procedure complexity and patient-specific characteristics.

1. Fehring TK, Odum S, Griffin WL, Mason JB, Nadaud M. Early failures in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:315-318.

2. Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7-13.

3. Schroer WC, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, et al. Why are total knees failing today? Etiology of total knee revision in 2010 and 2011. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 suppl):116-119.

4. Kim TK. CORR Insights(®): risk factors for revision within 10 years of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1208-1209.

5. Sheng PY, Jämsen E, Lehto MU, Konttinen YT, Pajamäki J, Halonen P. Revision total knee arthroplasty with the Total Condylar III system in inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1222-1224.

6. Haas SB, Insall JN, Montgomery W 3rd, Windsor RE. Revision total knee arthroplasty with use of modular components with stems inserted without cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(11):1700-1707.

7. Dennis DA. A stepwise approach to revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(4 suppl 1):32-38.

8. Vasso M, Beaufils P, Schiavone Panni A. Constraint choice in revision knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013;37(7):1279-1284.

9. Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Bone loss with revision total knee arthroplasty: defect classification and alternatives for reconstruction. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:167-175.

10. Ewald FC. The Knee Society total knee arthroplasty roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248:9-12.

11. Meneghini RM, Mont MA, Backstein DB, Bourne RB, Dennis DA, Scuderi GR. Development of a modern Knee Society radiographic evaluation system and methodology for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(12):2311-2314.

12. Nam D, Umunna BP, Cross MB, Reinhardt KR, Duggal S, Cornell CN. Clinical results and failure mechanisms of a nonmodular constrained knee without stem extensions. HSS J. 2012;8(2):96-102.

13. Lombardi AV Jr, Berend KR. The role of implant constraint in revision TKA: striking the balance. Orthopedics. 2006;29(9):847-849.

14. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Results of a second-generation constrained condylar prosthesis in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1228-1231.

15. Bae DK, Song SJ, Heo DB, Lee SH, Song WJ. Long-term survival rate of implants and modes of failure after revision total knee arthroplasty by a single surgeon. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1130-1134.

16. Wilke BK, Wagner ER, Trousdale RT. Long-term survival of semi-constrained total knee arthroplasty for revision surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):1005-1008.

17. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Ten-year survival and clinical results of constrained components in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6):803-808.

18. Jones RE. Total knee arthroplasty with modular rotating-platform hinge. Orthopedics. 2006;29(9 suppl):S80-S82.

19. Korim MT, Esler CN, Reddy VR, Ashford RU. A systematic review of endoprosthetic replacement for non-tumour indications around the knee joint. The Knee. 2013;20:367-375.

20. Hofmann AA, Goldberg T, Tanner AM, Kurtin SM. Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty using an articulating spacer: 2- to 12-year experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(430):125-131.

21. Peters CL, Erickson J, Kloepper RG, Mohr RA. Revision total knee arthroplasty with modular components inserted with metaphyseal cement and stems without cement. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:302-308.

22. Pala E, Trovarelli G, Calabro T, Angelini A, Abati CN, Ruggieri P. Survival of modern knee tumor megaprostheses: failures, functional results, and a comparative statistical analysis. Clinical Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:891-899.

23. Angelini A, Henderson E, Trovarelli G, Ruggieri P. Is there a role for knee arthrodesis with modular endoprostheses for tumor and revision of failed endoprostheses? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(10):3326-3335.

Before 1990, a considerable number of revisions were performed, largely for implant-associated failures, in the first few years after index primary knee arthroplasties.1,2 Since then, surgeons, manufacturers, and hospitals have collaborated to improve implant designs, techniques, and care guidelines.3,4 Despite the substantial improvements in designs, which led to implant longevity of more than 15 years in many cases, these devices still have limited life spans. Large studies have estimated that the risk for revision required after primary knee arthroplasty ranges from as low as 5% at 15 years to up to 9% at 10 years.4,5

The surgical goals of revision total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are to obtain stable fixation of the prosthesis to host bone, to obtain a stable range of motion compatible with the patient’s activities of daily living, and to achieve these goals while using the smallest amount of prosthetic augments and constraint so that the soft tissues may share in load transfer.6 As prosthetic constraint increases, the soft tissues participate less in load sharing, and increasing stresses are put on the implant–bone interface, which further increases the risk for early implant loosening.7 Hence, as characteristics of a revision implant become more constrained, there is often a higher rate of aseptic loosening expected.8

Controversy remains regarding the ideal implant type for revision TKA. To ensure the success of revision surgery and to reduce the risks for postoperative dissatisfaction, complications, and re-revision, orthopedists must understand the types of revision implant designs available, particularly as each has its own indications and potential complications.

In this article, we review the classification systems used for revision TKA as well as the types of prosthetic designs that can be used: posterior stabilized, nonlinked constrained, rotating hinge, and modular segmental.

1. Classification of bone loss and soft-tissue integrity

To further understand revision TKA, we must consider the complexity level of these cases, particularly by evaluating degree of bone loss and soft-tissue deficiency. The most accepted way to assess bone loss both before and during surgery is to use the AORI (Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute) classification system.9 Bone loss can be classified into 3 types: I, in which metaphyseal bone is intact and small bone defects do not compromise component stability; II, in which metaphyseal bone is damaged and cancellous bone loss requires cement fill, augments, or bone graft; and III, in which metaphyseal bone is deficient, and lost bone comprises a major portion of condyle or plateau and occasionally requires bone grafts or custom implants (Table 1). These patterns of bone loss are occasionally associated with detachment of the collateral ligament or patellar tendon.

In addition to understanding bone loss in revision TKA, surgeons must be aware of soft-tissue deficiencies (eg, collateral ligaments, extensor mechanism), which also influence type and amount of prosthesis constraint. Specifically, constraint choice depends on amount of bone loss and on the condition of stabilizing tissues, such as the collateral ligaments. Under conditions of minimal bone loss and intact peripheral ligaments, a less constrained device, such as a primary posterior stabilized system, can be considered. When ligaments are present but insufficient, a semiconstrained device is recommended. In the presence of medial collateral ligament attenuation or complete medial or lateral collateral ligament dysfunction, a fully constrained prosthesis is required.8 Therefore, amount of bone loss or soft-tissue deficiency often dictates which prosthesis to use.

For radiographic classification, the Knee Society roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system10 has been implemented to allow for uniform reporting of radiographic results and to ensure adequate preoperative planning and postoperative assessment of component alignment. This system incorporates the evaluation of alignment in the coronal, sagittal, and patellofemoral planes and assesses radiolucency using zones dividing the implant–bone interface into segments to allow for easier classification of areas of lucency. More recently, a modified version of the Knee Society system was constructed.11 This modification simplifies zone classifications and accommodates more complex revision knee designs and stem extensions.

2. Posterior stabilized designs

Cruciate-retaining prostheses are seldom applicable in the revision TKA setting because of frequent damage to the posterior cruciate ligament, except in the case of simple polyethylene exchanges or, potentially, revisions of failed unicompartmental TKAs. Thus, posterior stabilized designs are the first-line choice for revision TKA (Figure 1). These prostheses are indicated only when the posterior cruciate ligament is incompetent and in the setting of adequate flexion and extension and medial and lateral collateral ligament balancing.

However, studies have shown that posterior stabilized TKAs have a limited role in revision TKAs, as the amount of ligamentous and bony damage is often underestimated in these patients, and use of a primary implant in a revision setting often requires additional augments, all of which may have contributed to the high failure rate. Thus, this design should be used only when the patient has adequate bone stock (AORI type I) and collateral ligament tension. This situation further emphasizes the importance of performing intraoperative testing for ligamentous balance and bone deficit evaluation in order to determine the most appropriate implant (Table 2).

3. Nonlinked constrained designs

Nonlinked constrained (condylar constrained) designs are the devices most commonly used for revision TKAs (>50% of revision knees). These prostheses provide increased articular constraint, which is required in patients with persistent instability, despite appropriate soft-tissue balancing. Increased articular constraint allows for more knee stability by providing progressive varus-valgus, coronal, and rotational stability with the aid of taller and wider tibial posts.12 Specifically, these implants incorporate a tibial post that fits closely between the femoral condyles, allowing for less motion compared with a standard posterior stabilized design.12

In addition, these designs may be used with augments, stems, and allografts when bone loss is more substantial. In particular, stem extensions allow for load distribution to the diaphyseal regions of the tibia and femur and thereby aid in reducing the increased stress at the bone–implant interface, which is a common concern with these implants. However, these extensions cost more, require intramedullary invasion, and are associated with higher rates of leg and thigh pain.12

These prostheses are often implicated in cases involving a high degree of bone loss (eg, AORI type II or III). They are ideally used in cases in which complete revision of both tibial and femoral components is needed and are indicated in cases of incompetent posterior cruciate ligament, partial functional loss of medial or lateral collateral ligaments, or flexion-extension mismatch.13 Furthermore, use of a constrained prosthesis is recommended in the setting of varus or valgus instability, or repeated dislocations of a posterior stabilized design (Table 2).

Ten-year survivorship ranges from 85% to 96%, but this is substantially lower than the 95% to 96% for condylar constrained prostheses used in primary TKAs.14-17 Moreover, the large discrepancy between survivorship of primary TKA and revision TKA with a constrained prosthesis further affirms that the complexity of revision surgery, rather than the prosthesis used, may have more deleterious effects on outcomes. However, surgeons must be aware that increased constraint leads to increased stress on the prosthetic interfaces with associated aseptic loosening and early failure, and this continues to be a legitimate concern.

4. Rotating hinge designs

Many patients who undergo revision TKA can be managed with a posterior stabilizing or nonlinked constrained design. However, in patients who present with severe ligamentous instability and bone loss (AORI type II or III), a rotating hinge prostheses, or highly constrained device, is often recommended (Figure 2).18 By using a rotating mobile-bearing platform, this prosthesis permits axial rotation through a metal-reinforced polyethylene-post articulation in the tibial tray. In addition, it involves use of modular diaphyseal-engaging stems and diaphyseal sleeves, which allow for the bypass of bony defects and areas of bone loss (Table 2).

However, the rigid biomechanics of hinged prostheses is associated with increased risk for aseptic loosening (aseptic 10-year survival, 60%-80%), imparted by the transfer of stresses across the bone. The higher risk for early loosening, osteolysis, and excessive wear—caused by the highly restricted biomechanics of early generations of fixed hinged designs—has led to the development of new devices with mobile mechanics. Prosthetic designs have been improved with an added rotational axis to reduce torsional stress, a patellar resurfacing option, and better stem fixation and patellofemoral kinematics. Overall, these are aimed to improve rates of instability and aseptic loosening, with promising results demonstrated in the literature.

5. Modular segmental arthroplasty designs

Segmental arthroplasty prostheses, which typically are end-of-the-line revision TKA options, are applicable only in cases of extensive bone loss (more than can be treated with allografts or augments; AORI type 3), complete ligamentous disruption/absence, loss of periprosthetic soft tissue, and multiple previous revision procedures (Figure 3). Despite the limited indications for these prostheses, they yield quick return to function without graft nonunion or resorption, and they augment ingrowth/ongrowth. Furthermore, the next surgical option could be fusion or amputation. When failures were specifically evaluated for aseptic loosening across 4 studies, the survival rate ranged from 83% to 99.5%, with the most frequent complication being infection (up to 33% in one series).6,19-21

The major roles for segmental arthroplasty prostheses in primary TKAs are in the setting of oncologic conditions that require bony excision, or unreconstuctable fractures about the knee. Used after ancillary metastatic disease, these prostheses demonstrate positive results, according to several reports.22,23 In the setting of revision TKA, however, these prostheses should be used only when other surgical options are unfeasible, given the high risk for infection and the re-revision rates. Currently, revision TKAs with tumor prostheses have a high failure rate (up to 50%) because of the extensive surgery and the lack of bony and soft-tissue support (Table 2).

Conclusion

Orthopedists performing revision TKAs must consider bone stock and remaining ligament stability. In particular, they should choose implants for least constraint and adequate knee stability, as these are essential in minimizing the stresses on the implant–bone interface. Ultimately, functional outcomes, survivorship, and postoperative satisfaction determine the success of these designs. However, predictors of outcomes of revision surgery are often multifactorial, and surgeons must also consider procedure complexity and patient-specific characteristics.

Before 1990, a considerable number of revisions were performed, largely for implant-associated failures, in the first few years after index primary knee arthroplasties.1,2 Since then, surgeons, manufacturers, and hospitals have collaborated to improve implant designs, techniques, and care guidelines.3,4 Despite the substantial improvements in designs, which led to implant longevity of more than 15 years in many cases, these devices still have limited life spans. Large studies have estimated that the risk for revision required after primary knee arthroplasty ranges from as low as 5% at 15 years to up to 9% at 10 years.4,5

The surgical goals of revision total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are to obtain stable fixation of the prosthesis to host bone, to obtain a stable range of motion compatible with the patient’s activities of daily living, and to achieve these goals while using the smallest amount of prosthetic augments and constraint so that the soft tissues may share in load transfer.6 As prosthetic constraint increases, the soft tissues participate less in load sharing, and increasing stresses are put on the implant–bone interface, which further increases the risk for early implant loosening.7 Hence, as characteristics of a revision implant become more constrained, there is often a higher rate of aseptic loosening expected.8

Controversy remains regarding the ideal implant type for revision TKA. To ensure the success of revision surgery and to reduce the risks for postoperative dissatisfaction, complications, and re-revision, orthopedists must understand the types of revision implant designs available, particularly as each has its own indications and potential complications.

In this article, we review the classification systems used for revision TKA as well as the types of prosthetic designs that can be used: posterior stabilized, nonlinked constrained, rotating hinge, and modular segmental.

1. Classification of bone loss and soft-tissue integrity

To further understand revision TKA, we must consider the complexity level of these cases, particularly by evaluating degree of bone loss and soft-tissue deficiency. The most accepted way to assess bone loss both before and during surgery is to use the AORI (Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute) classification system.9 Bone loss can be classified into 3 types: I, in which metaphyseal bone is intact and small bone defects do not compromise component stability; II, in which metaphyseal bone is damaged and cancellous bone loss requires cement fill, augments, or bone graft; and III, in which metaphyseal bone is deficient, and lost bone comprises a major portion of condyle or plateau and occasionally requires bone grafts or custom implants (Table 1). These patterns of bone loss are occasionally associated with detachment of the collateral ligament or patellar tendon.

In addition to understanding bone loss in revision TKA, surgeons must be aware of soft-tissue deficiencies (eg, collateral ligaments, extensor mechanism), which also influence type and amount of prosthesis constraint. Specifically, constraint choice depends on amount of bone loss and on the condition of stabilizing tissues, such as the collateral ligaments. Under conditions of minimal bone loss and intact peripheral ligaments, a less constrained device, such as a primary posterior stabilized system, can be considered. When ligaments are present but insufficient, a semiconstrained device is recommended. In the presence of medial collateral ligament attenuation or complete medial or lateral collateral ligament dysfunction, a fully constrained prosthesis is required.8 Therefore, amount of bone loss or soft-tissue deficiency often dictates which prosthesis to use.

For radiographic classification, the Knee Society roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system10 has been implemented to allow for uniform reporting of radiographic results and to ensure adequate preoperative planning and postoperative assessment of component alignment. This system incorporates the evaluation of alignment in the coronal, sagittal, and patellofemoral planes and assesses radiolucency using zones dividing the implant–bone interface into segments to allow for easier classification of areas of lucency. More recently, a modified version of the Knee Society system was constructed.11 This modification simplifies zone classifications and accommodates more complex revision knee designs and stem extensions.

2. Posterior stabilized designs

Cruciate-retaining prostheses are seldom applicable in the revision TKA setting because of frequent damage to the posterior cruciate ligament, except in the case of simple polyethylene exchanges or, potentially, revisions of failed unicompartmental TKAs. Thus, posterior stabilized designs are the first-line choice for revision TKA (Figure 1). These prostheses are indicated only when the posterior cruciate ligament is incompetent and in the setting of adequate flexion and extension and medial and lateral collateral ligament balancing.

However, studies have shown that posterior stabilized TKAs have a limited role in revision TKAs, as the amount of ligamentous and bony damage is often underestimated in these patients, and use of a primary implant in a revision setting often requires additional augments, all of which may have contributed to the high failure rate. Thus, this design should be used only when the patient has adequate bone stock (AORI type I) and collateral ligament tension. This situation further emphasizes the importance of performing intraoperative testing for ligamentous balance and bone deficit evaluation in order to determine the most appropriate implant (Table 2).

3. Nonlinked constrained designs

Nonlinked constrained (condylar constrained) designs are the devices most commonly used for revision TKAs (>50% of revision knees). These prostheses provide increased articular constraint, which is required in patients with persistent instability, despite appropriate soft-tissue balancing. Increased articular constraint allows for more knee stability by providing progressive varus-valgus, coronal, and rotational stability with the aid of taller and wider tibial posts.12 Specifically, these implants incorporate a tibial post that fits closely between the femoral condyles, allowing for less motion compared with a standard posterior stabilized design.12

In addition, these designs may be used with augments, stems, and allografts when bone loss is more substantial. In particular, stem extensions allow for load distribution to the diaphyseal regions of the tibia and femur and thereby aid in reducing the increased stress at the bone–implant interface, which is a common concern with these implants. However, these extensions cost more, require intramedullary invasion, and are associated with higher rates of leg and thigh pain.12

These prostheses are often implicated in cases involving a high degree of bone loss (eg, AORI type II or III). They are ideally used in cases in which complete revision of both tibial and femoral components is needed and are indicated in cases of incompetent posterior cruciate ligament, partial functional loss of medial or lateral collateral ligaments, or flexion-extension mismatch.13 Furthermore, use of a constrained prosthesis is recommended in the setting of varus or valgus instability, or repeated dislocations of a posterior stabilized design (Table 2).

Ten-year survivorship ranges from 85% to 96%, but this is substantially lower than the 95% to 96% for condylar constrained prostheses used in primary TKAs.14-17 Moreover, the large discrepancy between survivorship of primary TKA and revision TKA with a constrained prosthesis further affirms that the complexity of revision surgery, rather than the prosthesis used, may have more deleterious effects on outcomes. However, surgeons must be aware that increased constraint leads to increased stress on the prosthetic interfaces with associated aseptic loosening and early failure, and this continues to be a legitimate concern.

4. Rotating hinge designs

Many patients who undergo revision TKA can be managed with a posterior stabilizing or nonlinked constrained design. However, in patients who present with severe ligamentous instability and bone loss (AORI type II or III), a rotating hinge prostheses, or highly constrained device, is often recommended (Figure 2).18 By using a rotating mobile-bearing platform, this prosthesis permits axial rotation through a metal-reinforced polyethylene-post articulation in the tibial tray. In addition, it involves use of modular diaphyseal-engaging stems and diaphyseal sleeves, which allow for the bypass of bony defects and areas of bone loss (Table 2).

However, the rigid biomechanics of hinged prostheses is associated with increased risk for aseptic loosening (aseptic 10-year survival, 60%-80%), imparted by the transfer of stresses across the bone. The higher risk for early loosening, osteolysis, and excessive wear—caused by the highly restricted biomechanics of early generations of fixed hinged designs—has led to the development of new devices with mobile mechanics. Prosthetic designs have been improved with an added rotational axis to reduce torsional stress, a patellar resurfacing option, and better stem fixation and patellofemoral kinematics. Overall, these are aimed to improve rates of instability and aseptic loosening, with promising results demonstrated in the literature.

5. Modular segmental arthroplasty designs

Segmental arthroplasty prostheses, which typically are end-of-the-line revision TKA options, are applicable only in cases of extensive bone loss (more than can be treated with allografts or augments; AORI type 3), complete ligamentous disruption/absence, loss of periprosthetic soft tissue, and multiple previous revision procedures (Figure 3). Despite the limited indications for these prostheses, they yield quick return to function without graft nonunion or resorption, and they augment ingrowth/ongrowth. Furthermore, the next surgical option could be fusion or amputation. When failures were specifically evaluated for aseptic loosening across 4 studies, the survival rate ranged from 83% to 99.5%, with the most frequent complication being infection (up to 33% in one series).6,19-21

The major roles for segmental arthroplasty prostheses in primary TKAs are in the setting of oncologic conditions that require bony excision, or unreconstuctable fractures about the knee. Used after ancillary metastatic disease, these prostheses demonstrate positive results, according to several reports.22,23 In the setting of revision TKA, however, these prostheses should be used only when other surgical options are unfeasible, given the high risk for infection and the re-revision rates. Currently, revision TKAs with tumor prostheses have a high failure rate (up to 50%) because of the extensive surgery and the lack of bony and soft-tissue support (Table 2).

Conclusion

Orthopedists performing revision TKAs must consider bone stock and remaining ligament stability. In particular, they should choose implants for least constraint and adequate knee stability, as these are essential in minimizing the stresses on the implant–bone interface. Ultimately, functional outcomes, survivorship, and postoperative satisfaction determine the success of these designs. However, predictors of outcomes of revision surgery are often multifactorial, and surgeons must also consider procedure complexity and patient-specific characteristics.

1. Fehring TK, Odum S, Griffin WL, Mason JB, Nadaud M. Early failures in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:315-318.

2. Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7-13.

3. Schroer WC, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, et al. Why are total knees failing today? Etiology of total knee revision in 2010 and 2011. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 suppl):116-119.

4. Kim TK. CORR Insights(®): risk factors for revision within 10 years of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1208-1209.

5. Sheng PY, Jämsen E, Lehto MU, Konttinen YT, Pajamäki J, Halonen P. Revision total knee arthroplasty with the Total Condylar III system in inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1222-1224.

6. Haas SB, Insall JN, Montgomery W 3rd, Windsor RE. Revision total knee arthroplasty with use of modular components with stems inserted without cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(11):1700-1707.

7. Dennis DA. A stepwise approach to revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(4 suppl 1):32-38.

8. Vasso M, Beaufils P, Schiavone Panni A. Constraint choice in revision knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013;37(7):1279-1284.

9. Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Bone loss with revision total knee arthroplasty: defect classification and alternatives for reconstruction. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:167-175.

10. Ewald FC. The Knee Society total knee arthroplasty roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248:9-12.

11. Meneghini RM, Mont MA, Backstein DB, Bourne RB, Dennis DA, Scuderi GR. Development of a modern Knee Society radiographic evaluation system and methodology for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(12):2311-2314.

12. Nam D, Umunna BP, Cross MB, Reinhardt KR, Duggal S, Cornell CN. Clinical results and failure mechanisms of a nonmodular constrained knee without stem extensions. HSS J. 2012;8(2):96-102.

13. Lombardi AV Jr, Berend KR. The role of implant constraint in revision TKA: striking the balance. Orthopedics. 2006;29(9):847-849.

14. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Results of a second-generation constrained condylar prosthesis in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1228-1231.

15. Bae DK, Song SJ, Heo DB, Lee SH, Song WJ. Long-term survival rate of implants and modes of failure after revision total knee arthroplasty by a single surgeon. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1130-1134.

16. Wilke BK, Wagner ER, Trousdale RT. Long-term survival of semi-constrained total knee arthroplasty for revision surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):1005-1008.

17. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Ten-year survival and clinical results of constrained components in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6):803-808.

18. Jones RE. Total knee arthroplasty with modular rotating-platform hinge. Orthopedics. 2006;29(9 suppl):S80-S82.

19. Korim MT, Esler CN, Reddy VR, Ashford RU. A systematic review of endoprosthetic replacement for non-tumour indications around the knee joint. The Knee. 2013;20:367-375.

20. Hofmann AA, Goldberg T, Tanner AM, Kurtin SM. Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty using an articulating spacer: 2- to 12-year experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(430):125-131.

21. Peters CL, Erickson J, Kloepper RG, Mohr RA. Revision total knee arthroplasty with modular components inserted with metaphyseal cement and stems without cement. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:302-308.

22. Pala E, Trovarelli G, Calabro T, Angelini A, Abati CN, Ruggieri P. Survival of modern knee tumor megaprostheses: failures, functional results, and a comparative statistical analysis. Clinical Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:891-899.

23. Angelini A, Henderson E, Trovarelli G, Ruggieri P. Is there a role for knee arthrodesis with modular endoprostheses for tumor and revision of failed endoprostheses? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(10):3326-3335.

1. Fehring TK, Odum S, Griffin WL, Mason JB, Nadaud M. Early failures in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;392:315-318.

2. Sharkey PF, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, Shastri S, Jacoby SM. Insall Award paper. Why are total knee arthroplasties failing today? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;404:7-13.

3. Schroer WC, Berend KR, Lombardi AV, et al. Why are total knees failing today? Etiology of total knee revision in 2010 and 2011. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(8 suppl):116-119.

4. Kim TK. CORR Insights(®): risk factors for revision within 10 years of total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(4):1208-1209.

5. Sheng PY, Jämsen E, Lehto MU, Konttinen YT, Pajamäki J, Halonen P. Revision total knee arthroplasty with the Total Condylar III system in inflammatory arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(9):1222-1224.

6. Haas SB, Insall JN, Montgomery W 3rd, Windsor RE. Revision total knee arthroplasty with use of modular components with stems inserted without cement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(11):1700-1707.

7. Dennis DA. A stepwise approach to revision total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22(4 suppl 1):32-38.

8. Vasso M, Beaufils P, Schiavone Panni A. Constraint choice in revision knee arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2013;37(7):1279-1284.

9. Engh GA, Ammeen DJ. Bone loss with revision total knee arthroplasty: defect classification and alternatives for reconstruction. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:167-175.

10. Ewald FC. The Knee Society total knee arthroplasty roentgenographic evaluation and scoring system. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;248:9-12.

11. Meneghini RM, Mont MA, Backstein DB, Bourne RB, Dennis DA, Scuderi GR. Development of a modern Knee Society radiographic evaluation system and methodology for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30(12):2311-2314.

12. Nam D, Umunna BP, Cross MB, Reinhardt KR, Duggal S, Cornell CN. Clinical results and failure mechanisms of a nonmodular constrained knee without stem extensions. HSS J. 2012;8(2):96-102.

13. Lombardi AV Jr, Berend KR. The role of implant constraint in revision TKA: striking the balance. Orthopedics. 2006;29(9):847-849.

14. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Results of a second-generation constrained condylar prosthesis in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2011;26(8):1228-1231.

15. Bae DK, Song SJ, Heo DB, Lee SH, Song WJ. Long-term survival rate of implants and modes of failure after revision total knee arthroplasty by a single surgeon. J Arthroplasty. 2013;28(7):1130-1134.

16. Wilke BK, Wagner ER, Trousdale RT. Long-term survival of semi-constrained total knee arthroplasty for revision surgery. J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(5):1005-1008.

17. Lachiewicz PF, Soileau ES. Ten-year survival and clinical results of constrained components in primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(6):803-808.

18. Jones RE. Total knee arthroplasty with modular rotating-platform hinge. Orthopedics. 2006;29(9 suppl):S80-S82.

19. Korim MT, Esler CN, Reddy VR, Ashford RU. A systematic review of endoprosthetic replacement for non-tumour indications around the knee joint. The Knee. 2013;20:367-375.

20. Hofmann AA, Goldberg T, Tanner AM, Kurtin SM. Treatment of infected total knee arthroplasty using an articulating spacer: 2- to 12-year experience. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;(430):125-131.

21. Peters CL, Erickson J, Kloepper RG, Mohr RA. Revision total knee arthroplasty with modular components inserted with metaphyseal cement and stems without cement. J Arthroplasty. 2005;20:302-308.

22. Pala E, Trovarelli G, Calabro T, Angelini A, Abati CN, Ruggieri P. Survival of modern knee tumor megaprostheses: failures, functional results, and a comparative statistical analysis. Clinical Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:891-899.

23. Angelini A, Henderson E, Trovarelli G, Ruggieri P. Is there a role for knee arthrodesis with modular endoprostheses for tumor and revision of failed endoprostheses? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471(10):3326-3335.

The Value of National and Hospital Registries

Following Dr. Sarmiento’s commentary, “Orthopedic Registries: Second Thoughts,” we agree that it is important and appropriate to question the value of any new additions to the orthopedic field, and registries are no exception. We thank Dr. Sarmiento for his comments on the viability of registries and the need for continued critical evaluation. Before joint registries, however, we had to rely on small-cohort analyses to assess outcomes and complications. Now, national and hospital registries, specifically joint registries, may be an invaluable source of information for orthopedic surgeons, patients, health care administrators, regulators, and implant suppliers.1,2

Contrary to Dr. Sarmiento’s belief that registry data results are likely to have been reported in the literature, it is difficult to refute the value of recent years’ registry data in helping surgeons shape their practice. For example, according to Lewallen and Etkin,3 the National Joint Registry of England and Wales information has provided orthopedic surgeons with crucial findings regarding the outcomes of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties. Using the England and Wales registry data from more than 400,000 primary total hip arthroplasties, Smith and colleagues4 noted that metal-on-metal stemmed articulations led to poor implant survival, particularly in young women with large-diameter heads, and indicated these articulations should not be used. Australian registry data on metal-on-metal devices and reports of failure rates up to 11%5 led one manufacturer to recall its implants.6 In addition, the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register evaluated survival rates and reasons for revision for 7 types of cemented primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) between 1994 and 2009.7 Data on more than 17,000 primary TKAs allowed Plate and colleagues8 to confidently determine that aseptic loosening was related to certain TKA designs. Using registry information, they identified patients at risk for dislocation in total hip arthroplasty and concluded that large-diameter femoral head articulations could reduce dislocation rates.

Obtaining such large cohorts of patients in individual studies is not only difficult but highly unlikely. Unlike registry data, these studies are often impractical in evaluating factors of low incidence, such as revision rates, as it is often difficult to find significant differences in small populations.9 Furthermore, these controlled trials homogenize patients—using exclusion and inclusion criteria to eliminate potential confounders—and thus poorly represent the heterogeneity of a typical hospital’s patient population.10 Although the literature may indeed have alluded to such complications, only a database as extensive as a registry can allow us to fully comprehend the outcomes of particular implants and devices.

Dr. Sarmiento points to the AO Swiss Fracture Registry as being of little benefit and raises the concern that the American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR) may follow with the same results. However, realizing a registry’s benefits may take time and the gradual accumulation of data. Supporting this, Hübschle and colleagues11 recently used AO Swiss Fracture Registry data to validate use of balloon kyphoplasty for vertebral compression fractures and concluded that the technique is safe and effective in reducing pain—thus possibly providing the federal office with the evidence needed for reimbursement for this intervention. Therefore, this registry is now providing useful information.

We can never truly know the veracity of participating surgeons, but it is naïve to assume that this issue arises only vis-à-vis registries. If we were to debate the ethical and professional standards of colleagues in our field, such questions could extend to all studies performed, even peer-reviewed studies. Therefore, we do not think this is reason to exclude the patient data and outcomes found in registries. We must emphasize that ultimately registry data are often most useful in highlighting trends and determining triggers for further study rather than in arriving at conclusions.1 In particular, registry data may be used in cohort studies that evaluate the risk factors for and incidence of certain outcomes. Focused higher-level interventional studies can then follow the trends observed.1 However, registry data are also valuable on their own, when higher-level, randomized controlled trials may be impractical or unethical.12

Dr. Sarmiento refers to corrupt relationships between companies and orthopedists as “representing a widespread loss of professionalism in our ranks.” Despite a US Justice Department investigation into these relationships, only a few doctors were found to have had inappropriate relationships.13 In addition, the investigation and prosecution of companies led to an agreement requiring federal monitoring and new corporate compliance procedures, which should ensure stricter adherence to regulations.14 We do not believe this should undermine the value of registries and the work that has been contributed by thousands of surgeons hoping to improve the field of orthopedics. In addition, concerns about the influence of well-known individuals may be better directed at individual institution–based research, particularly as these specific authors also often have conflicts of interest that may skew the presentation of results. The strength of registry data is in providing collective data and large samples from a multitude of surgeons rather than from just high-volume surgeons, and therefore registry data provide a better overall picture of patients and their procedures.15 Furthermore, trends observed in national registries in countries such as New Zealand16 may aid in effectively reducing the revision rate, possibly up to 10%.17 If a US national joint registry is marginally as effective, then we may see considerable savings for our health care services.17,18

We wholeheartedly agree that a yearly review of registries may be constructive. Dr. Sarmiento suggests an annual publication summarizing peer-reviewed articles and the opportunity for orthopedists to decide for themselves what treatments to choose based on reports from independent investigators. Although this sounds feasible, it would be difficult to decide which articles should be selected as pertinent for this type of publication. Any selection would be biased, and not all studies with high-level evidence are necessarily important or relevant. Therefore, selecting what is most appropriate to cite is not without its difficulties. We appreciate that there are problems in standardizing data reporting among registries. However, to improve interregistry collaboration, the US Food and Drug Administration is sponsoring the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries (ICOR) to facilitate data presentation.19 ICOR aims to increase cooperation, standardize analyses, and improve reporting, which will only strengthen the data available to us. Such efforts will ultimately enhance coordination and international collaboration among registries.15 In addition, incorporating patient-reported outcomes into our national registry will aid in quantifying arthroplasty outcomes from the patient’s perspective and will continue to improve total joint arthroplasties.20

Overall, this debate is useful and highly relevant in highlighting potential issues with registries. Although registries are not without their flaws, like all aspects of orthopedics they are ever evolving, and they must be continually modified and improved. However, disregard for the potential value of AJRR, which has benefits for orthopedists and patients alike, is premature. Once again, we thank Dr. Sarmiento for starting this discussion, which will allow us to continue to evaluate and improve our registries.

1. Konan S, Haddad FS. Joint registries: a Ptolemaic model of data interpretation? Bone Joint J Br. 2013;95(12):1585-1586.

2. Banerjee S, Cafri G, Isaacs AJ, et al. A distributed health data network analysis of survival outcomes: the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(suppl 1):7-11.

3. Lewallen DG, Etkin CD. The need for a national total joint registry. Orthop Nurs. 2013;32(1):4-5.

4. Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom AW; National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1199-1204.

5. de Steiger RN, Hang JR, Miller LN, Graves SE, Davidson DC. Five-year results of the ASR XL Acetabular System and the ASR Hip Resurfacing System: an analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2287-2293.

6. Hug KT, Watters TS, Vail TP, Bolognesi MP. The withdrawn ASR™ THA and hip resurfacing systems: how have our patients fared over 1 to 6 years? Clin Orthop. 2013;471(2):430-438.

7. Gøthesen O, Espehaug B, Havelin L, et al. Survival rates and causes of revision in cemented primary total knee replacement: a report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994–2009. Bone Joint J Br. 2013;95(5):636-642.

8. Plate JF, Seyler TM, Stroh DA, Issa K, Akbar M, Mont MA. Risk of dislocation using large- vs. small-diameter femoral heads in total hip arthroplasty. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:553.

9. Daruwalla ZJ, Wong KL, Pillay KR, Leong KM, Murphy DP. Does ageing Singapore need an electronic database of hip fracture patients? The value and role of a national joint registry and an electronic database of intertrochanteric and femoral neck fractures. Singapore Med J. 2014;55(5):287-288.

10. Rasmussen JV, Olsen BS, Fevang BT, et al. A review of national shoulder and elbow joint replacement registries. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1328-1335.

11. Hübschle L, Borgström F, Olafsson G, et al. Real-life results of balloon kyphoplasty for vertebral compression fractures from the SWISSspine registry. Spine J. 2014;14(9):2063-2077.

12. Ahn H, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Schemitsch EH. The use of hospital registries in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(suppl 3):68-72.

13. Youngstrom N. Swept up in major medical device case, physician pays $650,000 to settle kickback charges. AIS Health Business Daily. May 3, 2010.

14. Five companies in hip and knee replacement industry avoid prosecution by agreeing to compliance rules and monitoring [press release]. US Department of Justice website. http://www.justice.gov/usao/nj/Press/files/pdffiles/Older/hips0927.rel.pdf. Published September 27, 2007. Accessed February 19, 2015.

15. Namba RS, Inacio MC, Paxton EW, Robertsson O, Graves SE. The role of registry data in the evaluation of mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(suppl 3):48-50.

16. Insull PJ, Cobbett H, Frampton CM, Munro JT. The use of a lipped acetabular liner decreases the rate of revision for instability after total hip replacement: a study using data from the New Zealand Joint Registry. Bone Joint J Br. 2014;96(7):884-888.

17. Rankin EA. AJRR: becoming a national US joint registry. Orthopedics. 2013;36(3):175-176.

18. American Joint Replacement Registry website. https://teamwork.aaos.org/ajrr/SitePages/About%20Us.aspx. Accessed February 19, 2015.

19. International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries website. http://www.icor-initiative.org. Accessed February 19, 2015.

20. Franklin PD, Harrold L, Ayers DC. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes in total joint arthroplasty registries: challenges and opportunities. Clin Orthop. 2013;471(11):3482-3488.

Following Dr. Sarmiento’s commentary, “Orthopedic Registries: Second Thoughts,” we agree that it is important and appropriate to question the value of any new additions to the orthopedic field, and registries are no exception. We thank Dr. Sarmiento for his comments on the viability of registries and the need for continued critical evaluation. Before joint registries, however, we had to rely on small-cohort analyses to assess outcomes and complications. Now, national and hospital registries, specifically joint registries, may be an invaluable source of information for orthopedic surgeons, patients, health care administrators, regulators, and implant suppliers.1,2

Contrary to Dr. Sarmiento’s belief that registry data results are likely to have been reported in the literature, it is difficult to refute the value of recent years’ registry data in helping surgeons shape their practice. For example, according to Lewallen and Etkin,3 the National Joint Registry of England and Wales information has provided orthopedic surgeons with crucial findings regarding the outcomes of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties. Using the England and Wales registry data from more than 400,000 primary total hip arthroplasties, Smith and colleagues4 noted that metal-on-metal stemmed articulations led to poor implant survival, particularly in young women with large-diameter heads, and indicated these articulations should not be used. Australian registry data on metal-on-metal devices and reports of failure rates up to 11%5 led one manufacturer to recall its implants.6 In addition, the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register evaluated survival rates and reasons for revision for 7 types of cemented primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) between 1994 and 2009.7 Data on more than 17,000 primary TKAs allowed Plate and colleagues8 to confidently determine that aseptic loosening was related to certain TKA designs. Using registry information, they identified patients at risk for dislocation in total hip arthroplasty and concluded that large-diameter femoral head articulations could reduce dislocation rates.

Obtaining such large cohorts of patients in individual studies is not only difficult but highly unlikely. Unlike registry data, these studies are often impractical in evaluating factors of low incidence, such as revision rates, as it is often difficult to find significant differences in small populations.9 Furthermore, these controlled trials homogenize patients—using exclusion and inclusion criteria to eliminate potential confounders—and thus poorly represent the heterogeneity of a typical hospital’s patient population.10 Although the literature may indeed have alluded to such complications, only a database as extensive as a registry can allow us to fully comprehend the outcomes of particular implants and devices.

Dr. Sarmiento points to the AO Swiss Fracture Registry as being of little benefit and raises the concern that the American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR) may follow with the same results. However, realizing a registry’s benefits may take time and the gradual accumulation of data. Supporting this, Hübschle and colleagues11 recently used AO Swiss Fracture Registry data to validate use of balloon kyphoplasty for vertebral compression fractures and concluded that the technique is safe and effective in reducing pain—thus possibly providing the federal office with the evidence needed for reimbursement for this intervention. Therefore, this registry is now providing useful information.

We can never truly know the veracity of participating surgeons, but it is naïve to assume that this issue arises only vis-à-vis registries. If we were to debate the ethical and professional standards of colleagues in our field, such questions could extend to all studies performed, even peer-reviewed studies. Therefore, we do not think this is reason to exclude the patient data and outcomes found in registries. We must emphasize that ultimately registry data are often most useful in highlighting trends and determining triggers for further study rather than in arriving at conclusions.1 In particular, registry data may be used in cohort studies that evaluate the risk factors for and incidence of certain outcomes. Focused higher-level interventional studies can then follow the trends observed.1 However, registry data are also valuable on their own, when higher-level, randomized controlled trials may be impractical or unethical.12

Dr. Sarmiento refers to corrupt relationships between companies and orthopedists as “representing a widespread loss of professionalism in our ranks.” Despite a US Justice Department investigation into these relationships, only a few doctors were found to have had inappropriate relationships.13 In addition, the investigation and prosecution of companies led to an agreement requiring federal monitoring and new corporate compliance procedures, which should ensure stricter adherence to regulations.14 We do not believe this should undermine the value of registries and the work that has been contributed by thousands of surgeons hoping to improve the field of orthopedics. In addition, concerns about the influence of well-known individuals may be better directed at individual institution–based research, particularly as these specific authors also often have conflicts of interest that may skew the presentation of results. The strength of registry data is in providing collective data and large samples from a multitude of surgeons rather than from just high-volume surgeons, and therefore registry data provide a better overall picture of patients and their procedures.15 Furthermore, trends observed in national registries in countries such as New Zealand16 may aid in effectively reducing the revision rate, possibly up to 10%.17 If a US national joint registry is marginally as effective, then we may see considerable savings for our health care services.17,18

We wholeheartedly agree that a yearly review of registries may be constructive. Dr. Sarmiento suggests an annual publication summarizing peer-reviewed articles and the opportunity for orthopedists to decide for themselves what treatments to choose based on reports from independent investigators. Although this sounds feasible, it would be difficult to decide which articles should be selected as pertinent for this type of publication. Any selection would be biased, and not all studies with high-level evidence are necessarily important or relevant. Therefore, selecting what is most appropriate to cite is not without its difficulties. We appreciate that there are problems in standardizing data reporting among registries. However, to improve interregistry collaboration, the US Food and Drug Administration is sponsoring the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries (ICOR) to facilitate data presentation.19 ICOR aims to increase cooperation, standardize analyses, and improve reporting, which will only strengthen the data available to us. Such efforts will ultimately enhance coordination and international collaboration among registries.15 In addition, incorporating patient-reported outcomes into our national registry will aid in quantifying arthroplasty outcomes from the patient’s perspective and will continue to improve total joint arthroplasties.20

Overall, this debate is useful and highly relevant in highlighting potential issues with registries. Although registries are not without their flaws, like all aspects of orthopedics they are ever evolving, and they must be continually modified and improved. However, disregard for the potential value of AJRR, which has benefits for orthopedists and patients alike, is premature. Once again, we thank Dr. Sarmiento for starting this discussion, which will allow us to continue to evaluate and improve our registries.

Following Dr. Sarmiento’s commentary, “Orthopedic Registries: Second Thoughts,” we agree that it is important and appropriate to question the value of any new additions to the orthopedic field, and registries are no exception. We thank Dr. Sarmiento for his comments on the viability of registries and the need for continued critical evaluation. Before joint registries, however, we had to rely on small-cohort analyses to assess outcomes and complications. Now, national and hospital registries, specifically joint registries, may be an invaluable source of information for orthopedic surgeons, patients, health care administrators, regulators, and implant suppliers.1,2

Contrary to Dr. Sarmiento’s belief that registry data results are likely to have been reported in the literature, it is difficult to refute the value of recent years’ registry data in helping surgeons shape their practice. For example, according to Lewallen and Etkin,3 the National Joint Registry of England and Wales information has provided orthopedic surgeons with crucial findings regarding the outcomes of metal-on-metal hip arthroplasties. Using the England and Wales registry data from more than 400,000 primary total hip arthroplasties, Smith and colleagues4 noted that metal-on-metal stemmed articulations led to poor implant survival, particularly in young women with large-diameter heads, and indicated these articulations should not be used. Australian registry data on metal-on-metal devices and reports of failure rates up to 11%5 led one manufacturer to recall its implants.6 In addition, the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register evaluated survival rates and reasons for revision for 7 types of cemented primary total knee arthroplasty (TKA) between 1994 and 2009.7 Data on more than 17,000 primary TKAs allowed Plate and colleagues8 to confidently determine that aseptic loosening was related to certain TKA designs. Using registry information, they identified patients at risk for dislocation in total hip arthroplasty and concluded that large-diameter femoral head articulations could reduce dislocation rates.

Obtaining such large cohorts of patients in individual studies is not only difficult but highly unlikely. Unlike registry data, these studies are often impractical in evaluating factors of low incidence, such as revision rates, as it is often difficult to find significant differences in small populations.9 Furthermore, these controlled trials homogenize patients—using exclusion and inclusion criteria to eliminate potential confounders—and thus poorly represent the heterogeneity of a typical hospital’s patient population.10 Although the literature may indeed have alluded to such complications, only a database as extensive as a registry can allow us to fully comprehend the outcomes of particular implants and devices.

Dr. Sarmiento points to the AO Swiss Fracture Registry as being of little benefit and raises the concern that the American Joint Replacement Registry (AJRR) may follow with the same results. However, realizing a registry’s benefits may take time and the gradual accumulation of data. Supporting this, Hübschle and colleagues11 recently used AO Swiss Fracture Registry data to validate use of balloon kyphoplasty for vertebral compression fractures and concluded that the technique is safe and effective in reducing pain—thus possibly providing the federal office with the evidence needed for reimbursement for this intervention. Therefore, this registry is now providing useful information.

We can never truly know the veracity of participating surgeons, but it is naïve to assume that this issue arises only vis-à-vis registries. If we were to debate the ethical and professional standards of colleagues in our field, such questions could extend to all studies performed, even peer-reviewed studies. Therefore, we do not think this is reason to exclude the patient data and outcomes found in registries. We must emphasize that ultimately registry data are often most useful in highlighting trends and determining triggers for further study rather than in arriving at conclusions.1 In particular, registry data may be used in cohort studies that evaluate the risk factors for and incidence of certain outcomes. Focused higher-level interventional studies can then follow the trends observed.1 However, registry data are also valuable on their own, when higher-level, randomized controlled trials may be impractical or unethical.12

Dr. Sarmiento refers to corrupt relationships between companies and orthopedists as “representing a widespread loss of professionalism in our ranks.” Despite a US Justice Department investigation into these relationships, only a few doctors were found to have had inappropriate relationships.13 In addition, the investigation and prosecution of companies led to an agreement requiring federal monitoring and new corporate compliance procedures, which should ensure stricter adherence to regulations.14 We do not believe this should undermine the value of registries and the work that has been contributed by thousands of surgeons hoping to improve the field of orthopedics. In addition, concerns about the influence of well-known individuals may be better directed at individual institution–based research, particularly as these specific authors also often have conflicts of interest that may skew the presentation of results. The strength of registry data is in providing collective data and large samples from a multitude of surgeons rather than from just high-volume surgeons, and therefore registry data provide a better overall picture of patients and their procedures.15 Furthermore, trends observed in national registries in countries such as New Zealand16 may aid in effectively reducing the revision rate, possibly up to 10%.17 If a US national joint registry is marginally as effective, then we may see considerable savings for our health care services.17,18

We wholeheartedly agree that a yearly review of registries may be constructive. Dr. Sarmiento suggests an annual publication summarizing peer-reviewed articles and the opportunity for orthopedists to decide for themselves what treatments to choose based on reports from independent investigators. Although this sounds feasible, it would be difficult to decide which articles should be selected as pertinent for this type of publication. Any selection would be biased, and not all studies with high-level evidence are necessarily important or relevant. Therefore, selecting what is most appropriate to cite is not without its difficulties. We appreciate that there are problems in standardizing data reporting among registries. However, to improve interregistry collaboration, the US Food and Drug Administration is sponsoring the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries (ICOR) to facilitate data presentation.19 ICOR aims to increase cooperation, standardize analyses, and improve reporting, which will only strengthen the data available to us. Such efforts will ultimately enhance coordination and international collaboration among registries.15 In addition, incorporating patient-reported outcomes into our national registry will aid in quantifying arthroplasty outcomes from the patient’s perspective and will continue to improve total joint arthroplasties.20

Overall, this debate is useful and highly relevant in highlighting potential issues with registries. Although registries are not without their flaws, like all aspects of orthopedics they are ever evolving, and they must be continually modified and improved. However, disregard for the potential value of AJRR, which has benefits for orthopedists and patients alike, is premature. Once again, we thank Dr. Sarmiento for starting this discussion, which will allow us to continue to evaluate and improve our registries.

1. Konan S, Haddad FS. Joint registries: a Ptolemaic model of data interpretation? Bone Joint J Br. 2013;95(12):1585-1586.

2. Banerjee S, Cafri G, Isaacs AJ, et al. A distributed health data network analysis of survival outcomes: the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(suppl 1):7-11.

3. Lewallen DG, Etkin CD. The need for a national total joint registry. Orthop Nurs. 2013;32(1):4-5.

4. Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom AW; National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1199-1204.

5. de Steiger RN, Hang JR, Miller LN, Graves SE, Davidson DC. Five-year results of the ASR XL Acetabular System and the ASR Hip Resurfacing System: an analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2287-2293.

6. Hug KT, Watters TS, Vail TP, Bolognesi MP. The withdrawn ASR™ THA and hip resurfacing systems: how have our patients fared over 1 to 6 years? Clin Orthop. 2013;471(2):430-438.

7. Gøthesen O, Espehaug B, Havelin L, et al. Survival rates and causes of revision in cemented primary total knee replacement: a report from the Norwegian Arthroplasty Register 1994–2009. Bone Joint J Br. 2013;95(5):636-642.

8. Plate JF, Seyler TM, Stroh DA, Issa K, Akbar M, Mont MA. Risk of dislocation using large- vs. small-diameter femoral heads in total hip arthroplasty. BMC Res Notes. 2012;5:553.

9. Daruwalla ZJ, Wong KL, Pillay KR, Leong KM, Murphy DP. Does ageing Singapore need an electronic database of hip fracture patients? The value and role of a national joint registry and an electronic database of intertrochanteric and femoral neck fractures. Singapore Med J. 2014;55(5):287-288.

10. Rasmussen JV, Olsen BS, Fevang BT, et al. A review of national shoulder and elbow joint replacement registries. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(10):1328-1335.

11. Hübschle L, Borgström F, Olafsson G, et al. Real-life results of balloon kyphoplasty for vertebral compression fractures from the SWISSspine registry. Spine J. 2014;14(9):2063-2077.

12. Ahn H, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM, Schemitsch EH. The use of hospital registries in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(suppl 3):68-72.

13. Youngstrom N. Swept up in major medical device case, physician pays $650,000 to settle kickback charges. AIS Health Business Daily. May 3, 2010.

14. Five companies in hip and knee replacement industry avoid prosecution by agreeing to compliance rules and monitoring [press release]. US Department of Justice website. http://www.justice.gov/usao/nj/Press/files/pdffiles/Older/hips0927.rel.pdf. Published September 27, 2007. Accessed February 19, 2015.

15. Namba RS, Inacio MC, Paxton EW, Robertsson O, Graves SE. The role of registry data in the evaluation of mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(suppl 3):48-50.

16. Insull PJ, Cobbett H, Frampton CM, Munro JT. The use of a lipped acetabular liner decreases the rate of revision for instability after total hip replacement: a study using data from the New Zealand Joint Registry. Bone Joint J Br. 2014;96(7):884-888.

17. Rankin EA. AJRR: becoming a national US joint registry. Orthopedics. 2013;36(3):175-176.

18. American Joint Replacement Registry website. https://teamwork.aaos.org/ajrr/SitePages/About%20Us.aspx. Accessed February 19, 2015.

19. International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries website. http://www.icor-initiative.org. Accessed February 19, 2015.

20. Franklin PD, Harrold L, Ayers DC. Incorporating patient-reported outcomes in total joint arthroplasty registries: challenges and opportunities. Clin Orthop. 2013;471(11):3482-3488.

1. Konan S, Haddad FS. Joint registries: a Ptolemaic model of data interpretation? Bone Joint J Br. 2013;95(12):1585-1586.

2. Banerjee S, Cafri G, Isaacs AJ, et al. A distributed health data network analysis of survival outcomes: the International Consortium of Orthopaedic Registries perspective. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(suppl 1):7-11.

3. Lewallen DG, Etkin CD. The need for a national total joint registry. Orthop Nurs. 2013;32(1):4-5.

4. Smith AJ, Dieppe P, Vernon K, Porter M, Blom AW; National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Failure rates of stemmed metal-on-metal hip replacements: analysis of data from the National Joint Registry of England and Wales. Lancet. 2012;379(9822):1199-1204.

5. de Steiger RN, Hang JR, Miller LN, Graves SE, Davidson DC. Five-year results of the ASR XL Acetabular System and the ASR Hip Resurfacing System: an analysis from the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2287-2293.

6. Hug KT, Watters TS, Vail TP, Bolognesi MP. The withdrawn ASR™ THA and hip resurfacing systems: how have our patients fared over 1 to 6 years? Clin Orthop. 2013;471(2):430-438.