User login

Development and Evaluation of a Geriatric Mood Management Program

More older adults suffer from depression in a VHA setting (11%) than those in non-VHA settings (1%-5%).1 Depression and anxiety are evaluated less often in older adults and undertreated compared with younger adults.2-4 Unfortunately, older adults with depression and anxiety are vulnerable to suicide and disability; and they more frequently use medical services, such as the emergency department compared with older adults without these conditions.5-7

However, pharmacologic and behavioral treatments for late-life mood and anxiety disorders are available and are effective.8 These findings raise important questions about improving access to mental health care for older veterans with mood disorders. The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) fulfills one GRECC mission of carrying out transformative clinical demonstration projects by developing programs to address geriatric mood disorders.

The VHA has successfully implemented the nationwide integration of mental health management into primary care settings.9 To design and implement these programs locally, in 2007, all VHAs were invited to submit proposals related to mental health primary care integration. Local sites were given flexibility in their use of different evidence-based models for delivery of this integrated care.

Collaborative Models

Three models of mental health integration into primary care were adopted within VHA. All have resulted in improved patient outcomes.9 The co-located model places a behavioral health specialist within the same setting as primary care providers (PCPs), who shares in the evaluation, treatment planning, and monitoring of mental health outcomes. In the care management model, care managers facilitate evaluation and maintain communication with PCPs, but are not co-located with the PCPs. The third model is a blended model in which both a behavioral health specialist and a care manager may be involved in the management of mental health care. The care management model resulted in better participation in the evaluation and engagement in pharmacotherapy by older veterans in 2 VHA medical centers.10

Persistent Barriers for Older Veterans

The mental health-primary care integration initiative laid important foundations for improving access to mental health care. To provide a truly veteran-centered care option, however, programs require monitoring and analysis of the factors that impact care delivery and access. A recent evaluation of a local integration program, using a co-located model (ie, Primary Care Behavioral Health [PCBH]), demonstrated that there were several factors affecting older veterans’ access to mental health treatment.11 Older veterans with depression were less receptive to a mental health referral; 62% of older veterans refused mental health referrals compared with 32% of younger veterans who refused. Older veterans were less likely to complete at least 1 mental health clinic appointment, which was due in part to clinic location. All veterans were more likely to follow up with a mental health referral if first seen by the PCBH staff vs a referral by PCPs.

Geriatric-Specific Modifications to PCBH

The VAPAHCS GRECC, collaborating with the outpatient psychiatry service and the PCBH, sought to improve current mental health services for older veterans. Several barriers were identified: (1) limitations in types of interventions available to older veterans in the current PCBH and mental health programs; (2) the PCBH staff required geriatrics training, as recommended by the American Psychological Association12; and (3) resistance to receiving care in mental health clinics located several miles from the primary care setting. Therefore, a new pilot program was planned to address these barriers.

The Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care provided the funding for the initial program costs, and in September 2010, the Geriatric Primary Care Behavioral Health program (Geri-PCBH) was launched. The GRECC staff worked closely with the PCBH staff to offer a new service tailored to older veterans’ specific needs, which addressed the previously described program limitations.

Geri-PCBH Program

The Geri-PCBH program is a blended collaborative care model that provides outpatient-based mental health evaluation and treatment of mood disorders for older (aged ≥ 65 years) veterans. It is co-located with PCBH and PCPs within the primary care setting. The program extends PCBH services by providing psychotherapy that is contextually modified for older veterans. Older veterans may present with different therapy concerns than do younger veterans, such as caregiving, death of loved ones, and numerous and chronic medical illnesses. Illnesses may result in polypharmacy, giving rise to the need for understanding potential medication interactions in providing pharmacotherapy.

Within the program, geriatrics-trained psychologists and social workers offer psychotherapy. In addition, a geriatrician with expertise in polypharmacy offers pharmacotherapy. Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or both are offered and initiated following evaluation and discussion with the veteran. Veterans are either referred by the PCBH staff because they screened positive for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [PHQ-2] ≥ 2) during a regularly scheduled primary care clinic appointment or they are directly referred by primary care physicians for suspected mood problems. Veterans are then contacted immediately by a staff member for a baseline assessment appointment with a geriatrician and one of the therapists. The type of treatment and goals of therapy are determined during the initial meeting. The program is a training site for psychology and social work interns, to increase their geriatric mental health training.

Evaluation and Results

To determine improvements compared to PCBH program outcomes, the patients who attended the initial Geri-PCBH evaluation/intake appointment were tracked. A total of 79 older veterans were referred (average age, 82.7 years; range, aged 66-96 years); 14 veterans were ineligible due to significant cognitive impairment or lack of depressive symptoms. Compared with the 38% rate of attendance at intake for mental health referrals in the PCBH program, the Geri-PCBH program demonstrated a 90% attendance rate at the initial evaluation appointment. Fifty-five older veterans enrolled and received therapy: 39 received only psychotherapy, 14 received psychotherapy and antidepressant therapy, and 2 received only antidepressant therapy. Over the first 2 years of the program, 2 senior therapists and 5 trainees were able to see 53 patients for an average of 7 sessions per patient, which translated to about 14% of each therapist’s time.

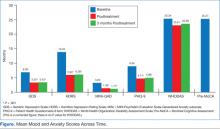

To determine the impact on patients, measures of depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS]; Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form [GDS-SF]; and Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Item [PHQ-9]), anxiety (Mini Psychiatric Evaluation Scale-Generalized Anxiety subscale [MINI-GAD]), overall distress (clinical global inventory), and functional status (12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale [WHODAS]) were administered at baseline, posttreatment, and 3 months posttreatment. The veterans demonstrated a significant decrease (> 50% decline on mood symptoms) on the HDRS, GDS, PHQ-9, and MINI-GAD subscale, which were all sustained 3 months posttreatment (Figure).

Although the overall disability score did not improve, the percentage of older veterans reporting “bad” or “moderate” health decreased (pre = 42%; post = 31.1%; 3-month follow-up = 20.9%); while those reporting “good” or “very good” health increased (pre = 58%; post = 65.7%; 3-month follow-up = 79.2%) by the 3-month follow-up. Veterans also reported very high satisfaction rates with the program overall (Mean = 30, standard deviation = 2.03; anchors for measure: 0 = not satisfied; 32 = highly satisfied).

Patient Testimonials

“Not in my wildest dreams did I think I’d ever share, on this level, my personal, past and present life…You have been so helpful and allowed me to move forward with pride and self respect.”

“It makes you feel a lot better. I enjoy life more now than I used to. That first time that [my therapist and I] talked, she convinced me just a change in attitude was a big thing. And since I changed my attitude and started listening to people, it’s made a heck of a difference.”

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of the Geri-PCBH evaluation demonstrated improvements in acceptance by older veterans with depression of mental health referrals and in increased access to treatment. The program addressed several identified barriers, such as having a more accessible location, offering treatment by experienced geriatrics-trained providers, and providing a range of mental health services tailored to older veterans’ needs. These factors may have increased older veterans’ willingness to attend mental health referrals to the Geri-PCBH program. Having initial assessments done soon after initial referral (usually < 2 weeks) and calling patients personally to explain the program and make appointments likely improved referral acceptance.

There are some limits to implementing this program in other settings related to variability in staffing, infrastructure, and resources available. The project is currently sustained with the present staff, with the goal of expanding services by telehealth technology to disseminate the program to older veterans in rural settings.

The VHA has made impressive strides toward improving the lives of older veterans with depression and anxiety. The program described here provides an example of how quality improvement efforts, which take into account the specific needs of the older veteran, can lead to a dramatic impact on the services offered and more importantly on veterans’ mental health and functional abilities.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with funding by the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care T21T Fund-10/11 060B2 and resources and use of facilities at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System in Palo Alto, California.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Blow FC, Owen RE. Specialty care for veterans with depression in the VHA 2002 national registry report. Ann Arbor, MI: VHA Health Services Research and Development; 2003.

2. Fischer LR, Wei F, Solberg LI, Rush WA, Heinrich RL. Treatment of elderly and other adult patients for depression in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(11):1554-1562.

3. Stanley MA, Roberts RE, Bourland SL, Novy DM. Anxiety disorders among older primary care patients. J Clin Geropsychology. 2001;7(2):105-116.

4. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629-640.

5. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):193-204.

6. Pérés K, Jagger C, Matthews FE; MRC CFAS. Impact of late-life self-reported emotional problems on disability-free life expectancy: Results from the MRC cognitive function and ageing study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(6):643-649.

7. Lee BW, Conwell Y, Shah MN, Barker WH, Delavan RL, Friedman B. Major depression and emergency medical services utilization in community-dwelling elderly persons with disabilities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1276-1282.

8. Small GW. Treatment of geriatric depression. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8(suppl 1):32-42.

9. Post EP, Van Stone WW. Veterans health administration primary care-mental health integration initiative. N C Med J. 2008;69(1):49-52.

10. Mavandadi S, Klaus JR, Oslin DW. Age group differences among veterans enrolled in a clinical service for behavioral health issues in primary care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(3):205-214.

11. Lindley S, Cacciapaglia H, Noronha D, Carlson E, Schatzberg A. Monitoring mental health treatment acceptance and initial treatment adherence in veterans: Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom versus other veterans of other eras. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1208:104-113.

12. American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychological practice with older adults. American Psychologist. 2004;59(4):236-260.

More older adults suffer from depression in a VHA setting (11%) than those in non-VHA settings (1%-5%).1 Depression and anxiety are evaluated less often in older adults and undertreated compared with younger adults.2-4 Unfortunately, older adults with depression and anxiety are vulnerable to suicide and disability; and they more frequently use medical services, such as the emergency department compared with older adults without these conditions.5-7

However, pharmacologic and behavioral treatments for late-life mood and anxiety disorders are available and are effective.8 These findings raise important questions about improving access to mental health care for older veterans with mood disorders. The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) fulfills one GRECC mission of carrying out transformative clinical demonstration projects by developing programs to address geriatric mood disorders.

The VHA has successfully implemented the nationwide integration of mental health management into primary care settings.9 To design and implement these programs locally, in 2007, all VHAs were invited to submit proposals related to mental health primary care integration. Local sites were given flexibility in their use of different evidence-based models for delivery of this integrated care.

Collaborative Models

Three models of mental health integration into primary care were adopted within VHA. All have resulted in improved patient outcomes.9 The co-located model places a behavioral health specialist within the same setting as primary care providers (PCPs), who shares in the evaluation, treatment planning, and monitoring of mental health outcomes. In the care management model, care managers facilitate evaluation and maintain communication with PCPs, but are not co-located with the PCPs. The third model is a blended model in which both a behavioral health specialist and a care manager may be involved in the management of mental health care. The care management model resulted in better participation in the evaluation and engagement in pharmacotherapy by older veterans in 2 VHA medical centers.10

Persistent Barriers for Older Veterans

The mental health-primary care integration initiative laid important foundations for improving access to mental health care. To provide a truly veteran-centered care option, however, programs require monitoring and analysis of the factors that impact care delivery and access. A recent evaluation of a local integration program, using a co-located model (ie, Primary Care Behavioral Health [PCBH]), demonstrated that there were several factors affecting older veterans’ access to mental health treatment.11 Older veterans with depression were less receptive to a mental health referral; 62% of older veterans refused mental health referrals compared with 32% of younger veterans who refused. Older veterans were less likely to complete at least 1 mental health clinic appointment, which was due in part to clinic location. All veterans were more likely to follow up with a mental health referral if first seen by the PCBH staff vs a referral by PCPs.

Geriatric-Specific Modifications to PCBH

The VAPAHCS GRECC, collaborating with the outpatient psychiatry service and the PCBH, sought to improve current mental health services for older veterans. Several barriers were identified: (1) limitations in types of interventions available to older veterans in the current PCBH and mental health programs; (2) the PCBH staff required geriatrics training, as recommended by the American Psychological Association12; and (3) resistance to receiving care in mental health clinics located several miles from the primary care setting. Therefore, a new pilot program was planned to address these barriers.

The Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care provided the funding for the initial program costs, and in September 2010, the Geriatric Primary Care Behavioral Health program (Geri-PCBH) was launched. The GRECC staff worked closely with the PCBH staff to offer a new service tailored to older veterans’ specific needs, which addressed the previously described program limitations.

Geri-PCBH Program

The Geri-PCBH program is a blended collaborative care model that provides outpatient-based mental health evaluation and treatment of mood disorders for older (aged ≥ 65 years) veterans. It is co-located with PCBH and PCPs within the primary care setting. The program extends PCBH services by providing psychotherapy that is contextually modified for older veterans. Older veterans may present with different therapy concerns than do younger veterans, such as caregiving, death of loved ones, and numerous and chronic medical illnesses. Illnesses may result in polypharmacy, giving rise to the need for understanding potential medication interactions in providing pharmacotherapy.

Within the program, geriatrics-trained psychologists and social workers offer psychotherapy. In addition, a geriatrician with expertise in polypharmacy offers pharmacotherapy. Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or both are offered and initiated following evaluation and discussion with the veteran. Veterans are either referred by the PCBH staff because they screened positive for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [PHQ-2] ≥ 2) during a regularly scheduled primary care clinic appointment or they are directly referred by primary care physicians for suspected mood problems. Veterans are then contacted immediately by a staff member for a baseline assessment appointment with a geriatrician and one of the therapists. The type of treatment and goals of therapy are determined during the initial meeting. The program is a training site for psychology and social work interns, to increase their geriatric mental health training.

Evaluation and Results

To determine improvements compared to PCBH program outcomes, the patients who attended the initial Geri-PCBH evaluation/intake appointment were tracked. A total of 79 older veterans were referred (average age, 82.7 years; range, aged 66-96 years); 14 veterans were ineligible due to significant cognitive impairment or lack of depressive symptoms. Compared with the 38% rate of attendance at intake for mental health referrals in the PCBH program, the Geri-PCBH program demonstrated a 90% attendance rate at the initial evaluation appointment. Fifty-five older veterans enrolled and received therapy: 39 received only psychotherapy, 14 received psychotherapy and antidepressant therapy, and 2 received only antidepressant therapy. Over the first 2 years of the program, 2 senior therapists and 5 trainees were able to see 53 patients for an average of 7 sessions per patient, which translated to about 14% of each therapist’s time.

To determine the impact on patients, measures of depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS]; Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form [GDS-SF]; and Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Item [PHQ-9]), anxiety (Mini Psychiatric Evaluation Scale-Generalized Anxiety subscale [MINI-GAD]), overall distress (clinical global inventory), and functional status (12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale [WHODAS]) were administered at baseline, posttreatment, and 3 months posttreatment. The veterans demonstrated a significant decrease (> 50% decline on mood symptoms) on the HDRS, GDS, PHQ-9, and MINI-GAD subscale, which were all sustained 3 months posttreatment (Figure).

Although the overall disability score did not improve, the percentage of older veterans reporting “bad” or “moderate” health decreased (pre = 42%; post = 31.1%; 3-month follow-up = 20.9%); while those reporting “good” or “very good” health increased (pre = 58%; post = 65.7%; 3-month follow-up = 79.2%) by the 3-month follow-up. Veterans also reported very high satisfaction rates with the program overall (Mean = 30, standard deviation = 2.03; anchors for measure: 0 = not satisfied; 32 = highly satisfied).

Patient Testimonials

“Not in my wildest dreams did I think I’d ever share, on this level, my personal, past and present life…You have been so helpful and allowed me to move forward with pride and self respect.”

“It makes you feel a lot better. I enjoy life more now than I used to. That first time that [my therapist and I] talked, she convinced me just a change in attitude was a big thing. And since I changed my attitude and started listening to people, it’s made a heck of a difference.”

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of the Geri-PCBH evaluation demonstrated improvements in acceptance by older veterans with depression of mental health referrals and in increased access to treatment. The program addressed several identified barriers, such as having a more accessible location, offering treatment by experienced geriatrics-trained providers, and providing a range of mental health services tailored to older veterans’ needs. These factors may have increased older veterans’ willingness to attend mental health referrals to the Geri-PCBH program. Having initial assessments done soon after initial referral (usually < 2 weeks) and calling patients personally to explain the program and make appointments likely improved referral acceptance.

There are some limits to implementing this program in other settings related to variability in staffing, infrastructure, and resources available. The project is currently sustained with the present staff, with the goal of expanding services by telehealth technology to disseminate the program to older veterans in rural settings.

The VHA has made impressive strides toward improving the lives of older veterans with depression and anxiety. The program described here provides an example of how quality improvement efforts, which take into account the specific needs of the older veteran, can lead to a dramatic impact on the services offered and more importantly on veterans’ mental health and functional abilities.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with funding by the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care T21T Fund-10/11 060B2 and resources and use of facilities at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System in Palo Alto, California.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

More older adults suffer from depression in a VHA setting (11%) than those in non-VHA settings (1%-5%).1 Depression and anxiety are evaluated less often in older adults and undertreated compared with younger adults.2-4 Unfortunately, older adults with depression and anxiety are vulnerable to suicide and disability; and they more frequently use medical services, such as the emergency department compared with older adults without these conditions.5-7

However, pharmacologic and behavioral treatments for late-life mood and anxiety disorders are available and are effective.8 These findings raise important questions about improving access to mental health care for older veterans with mood disorders. The VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Geriatric Research Education and Clinical Center (GRECC) fulfills one GRECC mission of carrying out transformative clinical demonstration projects by developing programs to address geriatric mood disorders.

The VHA has successfully implemented the nationwide integration of mental health management into primary care settings.9 To design and implement these programs locally, in 2007, all VHAs were invited to submit proposals related to mental health primary care integration. Local sites were given flexibility in their use of different evidence-based models for delivery of this integrated care.

Collaborative Models

Three models of mental health integration into primary care were adopted within VHA. All have resulted in improved patient outcomes.9 The co-located model places a behavioral health specialist within the same setting as primary care providers (PCPs), who shares in the evaluation, treatment planning, and monitoring of mental health outcomes. In the care management model, care managers facilitate evaluation and maintain communication with PCPs, but are not co-located with the PCPs. The third model is a blended model in which both a behavioral health specialist and a care manager may be involved in the management of mental health care. The care management model resulted in better participation in the evaluation and engagement in pharmacotherapy by older veterans in 2 VHA medical centers.10

Persistent Barriers for Older Veterans

The mental health-primary care integration initiative laid important foundations for improving access to mental health care. To provide a truly veteran-centered care option, however, programs require monitoring and analysis of the factors that impact care delivery and access. A recent evaluation of a local integration program, using a co-located model (ie, Primary Care Behavioral Health [PCBH]), demonstrated that there were several factors affecting older veterans’ access to mental health treatment.11 Older veterans with depression were less receptive to a mental health referral; 62% of older veterans refused mental health referrals compared with 32% of younger veterans who refused. Older veterans were less likely to complete at least 1 mental health clinic appointment, which was due in part to clinic location. All veterans were more likely to follow up with a mental health referral if first seen by the PCBH staff vs a referral by PCPs.

Geriatric-Specific Modifications to PCBH

The VAPAHCS GRECC, collaborating with the outpatient psychiatry service and the PCBH, sought to improve current mental health services for older veterans. Several barriers were identified: (1) limitations in types of interventions available to older veterans in the current PCBH and mental health programs; (2) the PCBH staff required geriatrics training, as recommended by the American Psychological Association12; and (3) resistance to receiving care in mental health clinics located several miles from the primary care setting. Therefore, a new pilot program was planned to address these barriers.

The Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care provided the funding for the initial program costs, and in September 2010, the Geriatric Primary Care Behavioral Health program (Geri-PCBH) was launched. The GRECC staff worked closely with the PCBH staff to offer a new service tailored to older veterans’ specific needs, which addressed the previously described program limitations.

Geri-PCBH Program

The Geri-PCBH program is a blended collaborative care model that provides outpatient-based mental health evaluation and treatment of mood disorders for older (aged ≥ 65 years) veterans. It is co-located with PCBH and PCPs within the primary care setting. The program extends PCBH services by providing psychotherapy that is contextually modified for older veterans. Older veterans may present with different therapy concerns than do younger veterans, such as caregiving, death of loved ones, and numerous and chronic medical illnesses. Illnesses may result in polypharmacy, giving rise to the need for understanding potential medication interactions in providing pharmacotherapy.

Within the program, geriatrics-trained psychologists and social workers offer psychotherapy. In addition, a geriatrician with expertise in polypharmacy offers pharmacotherapy. Psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, or both are offered and initiated following evaluation and discussion with the veteran. Veterans are either referred by the PCBH staff because they screened positive for depression (Patient Health Questionnaire-2 [PHQ-2] ≥ 2) during a regularly scheduled primary care clinic appointment or they are directly referred by primary care physicians for suspected mood problems. Veterans are then contacted immediately by a staff member for a baseline assessment appointment with a geriatrician and one of the therapists. The type of treatment and goals of therapy are determined during the initial meeting. The program is a training site for psychology and social work interns, to increase their geriatric mental health training.

Evaluation and Results

To determine improvements compared to PCBH program outcomes, the patients who attended the initial Geri-PCBH evaluation/intake appointment were tracked. A total of 79 older veterans were referred (average age, 82.7 years; range, aged 66-96 years); 14 veterans were ineligible due to significant cognitive impairment or lack of depressive symptoms. Compared with the 38% rate of attendance at intake for mental health referrals in the PCBH program, the Geri-PCBH program demonstrated a 90% attendance rate at the initial evaluation appointment. Fifty-five older veterans enrolled and received therapy: 39 received only psychotherapy, 14 received psychotherapy and antidepressant therapy, and 2 received only antidepressant therapy. Over the first 2 years of the program, 2 senior therapists and 5 trainees were able to see 53 patients for an average of 7 sessions per patient, which translated to about 14% of each therapist’s time.

To determine the impact on patients, measures of depression (Hamilton Depression Rating Scale [HDRS]; Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form [GDS-SF]; and Patient Health Questionnaire 9 Item [PHQ-9]), anxiety (Mini Psychiatric Evaluation Scale-Generalized Anxiety subscale [MINI-GAD]), overall distress (clinical global inventory), and functional status (12-item World Health Organization Disability Assessment Scale [WHODAS]) were administered at baseline, posttreatment, and 3 months posttreatment. The veterans demonstrated a significant decrease (> 50% decline on mood symptoms) on the HDRS, GDS, PHQ-9, and MINI-GAD subscale, which were all sustained 3 months posttreatment (Figure).

Although the overall disability score did not improve, the percentage of older veterans reporting “bad” or “moderate” health decreased (pre = 42%; post = 31.1%; 3-month follow-up = 20.9%); while those reporting “good” or “very good” health increased (pre = 58%; post = 65.7%; 3-month follow-up = 79.2%) by the 3-month follow-up. Veterans also reported very high satisfaction rates with the program overall (Mean = 30, standard deviation = 2.03; anchors for measure: 0 = not satisfied; 32 = highly satisfied).

Patient Testimonials

“Not in my wildest dreams did I think I’d ever share, on this level, my personal, past and present life…You have been so helpful and allowed me to move forward with pride and self respect.”

“It makes you feel a lot better. I enjoy life more now than I used to. That first time that [my therapist and I] talked, she convinced me just a change in attitude was a big thing. And since I changed my attitude and started listening to people, it’s made a heck of a difference.”

Discussion and Conclusion

The results of the Geri-PCBH evaluation demonstrated improvements in acceptance by older veterans with depression of mental health referrals and in increased access to treatment. The program addressed several identified barriers, such as having a more accessible location, offering treatment by experienced geriatrics-trained providers, and providing a range of mental health services tailored to older veterans’ needs. These factors may have increased older veterans’ willingness to attend mental health referrals to the Geri-PCBH program. Having initial assessments done soon after initial referral (usually < 2 weeks) and calling patients personally to explain the program and make appointments likely improved referral acceptance.

There are some limits to implementing this program in other settings related to variability in staffing, infrastructure, and resources available. The project is currently sustained with the present staff, with the goal of expanding services by telehealth technology to disseminate the program to older veterans in rural settings.

The VHA has made impressive strides toward improving the lives of older veterans with depression and anxiety. The program described here provides an example of how quality improvement efforts, which take into account the specific needs of the older veteran, can lead to a dramatic impact on the services offered and more importantly on veterans’ mental health and functional abilities.

Acknowledgements

This material is the result of work supported with funding by the Office of Geriatrics and Extended Care T21T Fund-10/11 060B2 and resources and use of facilities at the VA Palo Alto Health Care System in Palo Alto, California.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Blow FC, Owen RE. Specialty care for veterans with depression in the VHA 2002 national registry report. Ann Arbor, MI: VHA Health Services Research and Development; 2003.

2. Fischer LR, Wei F, Solberg LI, Rush WA, Heinrich RL. Treatment of elderly and other adult patients for depression in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(11):1554-1562.

3. Stanley MA, Roberts RE, Bourland SL, Novy DM. Anxiety disorders among older primary care patients. J Clin Geropsychology. 2001;7(2):105-116.

4. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629-640.

5. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):193-204.

6. Pérés K, Jagger C, Matthews FE; MRC CFAS. Impact of late-life self-reported emotional problems on disability-free life expectancy: Results from the MRC cognitive function and ageing study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(6):643-649.

7. Lee BW, Conwell Y, Shah MN, Barker WH, Delavan RL, Friedman B. Major depression and emergency medical services utilization in community-dwelling elderly persons with disabilities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1276-1282.

8. Small GW. Treatment of geriatric depression. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8(suppl 1):32-42.

9. Post EP, Van Stone WW. Veterans health administration primary care-mental health integration initiative. N C Med J. 2008;69(1):49-52.

10. Mavandadi S, Klaus JR, Oslin DW. Age group differences among veterans enrolled in a clinical service for behavioral health issues in primary care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(3):205-214.

11. Lindley S, Cacciapaglia H, Noronha D, Carlson E, Schatzberg A. Monitoring mental health treatment acceptance and initial treatment adherence in veterans: Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom versus other veterans of other eras. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1208:104-113.

12. American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychological practice with older adults. American Psychologist. 2004;59(4):236-260.

1. Blow FC, Owen RE. Specialty care for veterans with depression in the VHA 2002 national registry report. Ann Arbor, MI: VHA Health Services Research and Development; 2003.

2. Fischer LR, Wei F, Solberg LI, Rush WA, Heinrich RL. Treatment of elderly and other adult patients for depression in primary care. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(11):1554-1562.

3. Stanley MA, Roberts RE, Bourland SL, Novy DM. Anxiety disorders among older primary care patients. J Clin Geropsychology. 2001;7(2):105-116.

4. Wang PS, Lane M, Olfson M, Pincus HA, Wells KB, Kessler RC. Twelve-month use of mental health services in the United States: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):629-640.

5. Conwell Y, Duberstein PR, Caine ED. Risk factors for suicide in later life. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52(3):193-204.

6. Pérés K, Jagger C, Matthews FE; MRC CFAS. Impact of late-life self-reported emotional problems on disability-free life expectancy: Results from the MRC cognitive function and ageing study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(6):643-649.

7. Lee BW, Conwell Y, Shah MN, Barker WH, Delavan RL, Friedman B. Major depression and emergency medical services utilization in community-dwelling elderly persons with disabilities. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(12):1276-1282.

8. Small GW. Treatment of geriatric depression. Depress Anxiety. 1998;8(suppl 1):32-42.

9. Post EP, Van Stone WW. Veterans health administration primary care-mental health integration initiative. N C Med J. 2008;69(1):49-52.

10. Mavandadi S, Klaus JR, Oslin DW. Age group differences among veterans enrolled in a clinical service for behavioral health issues in primary care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2012;20(3):205-214.

11. Lindley S, Cacciapaglia H, Noronha D, Carlson E, Schatzberg A. Monitoring mental health treatment acceptance and initial treatment adherence in veterans: Veterans of Operations Enduring Freedom and Iraqi Freedom versus other veterans of other eras. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1208:104-113.

12. American Psychological Association. Guidelines for psychological practice with older adults. American Psychologist. 2004;59(4):236-260.