User login

Overreliance on subspecialty in a case of endocarditis

Story

DB was a 20-year-old woman who presented to her primary care physician (PCP) with fever and myalgias. Her past medical history was significant for open heart surgery 3 years earlier for ventricular myxoma and aortic valve repair. Her temperature in the office was 39.1 C. Her examination was otherwise unremarkable. An influenza swab was negative. Cultures were drawn and DB was sent home with instructions to increase her fluids and use acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. Two days later, 2 out of 2 preliminary blood cultures were reported positive for coagulase-negative, gram positive cocci in clusters. DB was referred to the hospital where she was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist.

Dr. Hospitalist performed a history and physical and noted an impression of sepsis from subacute bacterial endocarditis. He initiated intravenous vancomycin and ceftriaxone, repeated blood cultures, ordered an echocardiogram, and obtained an infectious disease (ID) consult. On hospital day 2, the ID consultant documented that DB had positive blood cultures for coagulase-negative staphylococci but no true evidence of sepsis. She was noted to be afebrile with a normal white blood cell count. Although the echocardiogram was pending, the ID consultant recommended that intravenous antibiotics be discontinued and that she was safe to be discharged home with follow-up blood cultures in 1 week. Later that day, the echocardiogram found a thickened aortic valve with an increased density that suggested possible vegetation.

On the morning of hospital day 3, DB had a Tmax (time to maximum plasma concentration) of 38.8 C overnight. The repeat blood cultures drawn on admission showed no growth to date. Dr. Hospitalist stopped the intravenous antibiotics and discharged DB to home. Unknown to Dr. Hospitalist at the time, the original cultures drawn at the PCP’s office were finalized as Staphylococcus lugdunensis.

One week later, DB followed up with her PCP. She continued to have fevers, myalgias, and fatigue. Blood cultures were obtained and reported the following day as 2 out of 2 positive for S. lugdunensis. DB once again returned to the hospital and was started on intravenous antibiotics. Two days into her second hospital stay, DB complained of feeling hot. She sat up in the bed and then went unconscious. After almost 2 hours of resuscitation, DB was pronounced dead. An autopsy was performed and identified the cause of death as bacterial endocarditis (S. lugdunensis) with massive vegetations and aortic valve rupture.

Complaint

DB’s mother immediately brought a claim against Dr. Hospitalist and the ID consultant from the first hospital stay. The complaint alleged that DB was inappropriately discharged from the first hospitalization without ongoing intravenous antibiotic therapy. As a result, DB missed 8 days of antibiotic treatment allowing her untreated infection to irreversibly damage her heart. The complaint further alleged that this gap in treatment was the proximate cause of DB’s death.

Scientific principles

Staphylococcus lugdunensis is a coagulase-negative staphylococcus (CNS). Like other CNS, S. lugdunensis in humans ranges from a harmless skin commensal to a life-threatening pathogen (as with infective endocarditis). Unlike other CNS, however, S. lugdunensis can cause severe disease reminiscent of the virulent infections frequently attributable to S. aureus. S. lugdunensis endocarditis is an aggressive infection that affects native valves with greater frequency than prosthetic valves in contrast to other CNS. S. lugdunensis native valve endocarditis is typically community acquired and is associated with a high rate of complications and death.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The only defense that Dr. Hospitalist offered was that he relied on his subspecialty consultant. Dr. Hospitalist argued that he was a generalist and not an expert in endocarditis or CNS. As a result, he followed the recommendations of the ID consultant and he further argued that he had the right to do so.

The plaintiff countered essentially countered with "Would you jump off the roof of a building just because someone told you to?" argument. In this case, the positive blood cultures, the history of aortic valve repair, and the suggestive echocardiogram were indisputable facts. Discovery in this case confirmed that Dr. Hospitalist never spoke with the ID consultant at any point during the first hospital stay.

Plaintiff experts argued that Dr. Hospitalist was a board-certified internist practicing hospital-based internal medicine and as such, he had or should have had the requisite knowledge, skills, and attitudes to evaluate, diagnose, and treat endocarditis. In this case, it appeared that Dr. Hospitalist "blindly" followed the recommendations of the ID consultant without considering all the evidence at hand. Plaintiff experts argued that in this situation, the standard of care required that Dr. Hospitalist question the plan of care outlined by his consultant. Had he done so, it is likely that both Dr. Hospitalist and the infectious disease consultant would have learned that the original blood cultures grew S. lugdunensis and antibiotics would never have been discontinued.

Conclusion

As the attending physicians of record, hospitalists carry the ultimate responsibility for the discharge decision. It is common to ask subspecialty consultants their opinion regarding stability for discharge and/or the need for ongoing hospital therapy. Yet, it is important for all hospitalists to remember that the consultant recommendations are just opinions that must be weighed against all the other evidence currently available. It is also helpful to have and document verbal discussions with consultants when discharge decisions are being made (and partially relied upon) with their subspecialty input.

The ID consultant in this case settled almost immediately with DB’s family. Dr. Hospitalist defended himself a little longer, but ultimately settled this case with the plaintiff for an undisclosed amount.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

Story

DB was a 20-year-old woman who presented to her primary care physician (PCP) with fever and myalgias. Her past medical history was significant for open heart surgery 3 years earlier for ventricular myxoma and aortic valve repair. Her temperature in the office was 39.1 C. Her examination was otherwise unremarkable. An influenza swab was negative. Cultures were drawn and DB was sent home with instructions to increase her fluids and use acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. Two days later, 2 out of 2 preliminary blood cultures were reported positive for coagulase-negative, gram positive cocci in clusters. DB was referred to the hospital where she was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist.

Dr. Hospitalist performed a history and physical and noted an impression of sepsis from subacute bacterial endocarditis. He initiated intravenous vancomycin and ceftriaxone, repeated blood cultures, ordered an echocardiogram, and obtained an infectious disease (ID) consult. On hospital day 2, the ID consultant documented that DB had positive blood cultures for coagulase-negative staphylococci but no true evidence of sepsis. She was noted to be afebrile with a normal white blood cell count. Although the echocardiogram was pending, the ID consultant recommended that intravenous antibiotics be discontinued and that she was safe to be discharged home with follow-up blood cultures in 1 week. Later that day, the echocardiogram found a thickened aortic valve with an increased density that suggested possible vegetation.

On the morning of hospital day 3, DB had a Tmax (time to maximum plasma concentration) of 38.8 C overnight. The repeat blood cultures drawn on admission showed no growth to date. Dr. Hospitalist stopped the intravenous antibiotics and discharged DB to home. Unknown to Dr. Hospitalist at the time, the original cultures drawn at the PCP’s office were finalized as Staphylococcus lugdunensis.

One week later, DB followed up with her PCP. She continued to have fevers, myalgias, and fatigue. Blood cultures were obtained and reported the following day as 2 out of 2 positive for S. lugdunensis. DB once again returned to the hospital and was started on intravenous antibiotics. Two days into her second hospital stay, DB complained of feeling hot. She sat up in the bed and then went unconscious. After almost 2 hours of resuscitation, DB was pronounced dead. An autopsy was performed and identified the cause of death as bacterial endocarditis (S. lugdunensis) with massive vegetations and aortic valve rupture.

Complaint

DB’s mother immediately brought a claim against Dr. Hospitalist and the ID consultant from the first hospital stay. The complaint alleged that DB was inappropriately discharged from the first hospitalization without ongoing intravenous antibiotic therapy. As a result, DB missed 8 days of antibiotic treatment allowing her untreated infection to irreversibly damage her heart. The complaint further alleged that this gap in treatment was the proximate cause of DB’s death.

Scientific principles

Staphylococcus lugdunensis is a coagulase-negative staphylococcus (CNS). Like other CNS, S. lugdunensis in humans ranges from a harmless skin commensal to a life-threatening pathogen (as with infective endocarditis). Unlike other CNS, however, S. lugdunensis can cause severe disease reminiscent of the virulent infections frequently attributable to S. aureus. S. lugdunensis endocarditis is an aggressive infection that affects native valves with greater frequency than prosthetic valves in contrast to other CNS. S. lugdunensis native valve endocarditis is typically community acquired and is associated with a high rate of complications and death.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The only defense that Dr. Hospitalist offered was that he relied on his subspecialty consultant. Dr. Hospitalist argued that he was a generalist and not an expert in endocarditis or CNS. As a result, he followed the recommendations of the ID consultant and he further argued that he had the right to do so.

The plaintiff countered essentially countered with "Would you jump off the roof of a building just because someone told you to?" argument. In this case, the positive blood cultures, the history of aortic valve repair, and the suggestive echocardiogram were indisputable facts. Discovery in this case confirmed that Dr. Hospitalist never spoke with the ID consultant at any point during the first hospital stay.

Plaintiff experts argued that Dr. Hospitalist was a board-certified internist practicing hospital-based internal medicine and as such, he had or should have had the requisite knowledge, skills, and attitudes to evaluate, diagnose, and treat endocarditis. In this case, it appeared that Dr. Hospitalist "blindly" followed the recommendations of the ID consultant without considering all the evidence at hand. Plaintiff experts argued that in this situation, the standard of care required that Dr. Hospitalist question the plan of care outlined by his consultant. Had he done so, it is likely that both Dr. Hospitalist and the infectious disease consultant would have learned that the original blood cultures grew S. lugdunensis and antibiotics would never have been discontinued.

Conclusion

As the attending physicians of record, hospitalists carry the ultimate responsibility for the discharge decision. It is common to ask subspecialty consultants their opinion regarding stability for discharge and/or the need for ongoing hospital therapy. Yet, it is important for all hospitalists to remember that the consultant recommendations are just opinions that must be weighed against all the other evidence currently available. It is also helpful to have and document verbal discussions with consultants when discharge decisions are being made (and partially relied upon) with their subspecialty input.

The ID consultant in this case settled almost immediately with DB’s family. Dr. Hospitalist defended himself a little longer, but ultimately settled this case with the plaintiff for an undisclosed amount.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

Story

DB was a 20-year-old woman who presented to her primary care physician (PCP) with fever and myalgias. Her past medical history was significant for open heart surgery 3 years earlier for ventricular myxoma and aortic valve repair. Her temperature in the office was 39.1 C. Her examination was otherwise unremarkable. An influenza swab was negative. Cultures were drawn and DB was sent home with instructions to increase her fluids and use acetaminophen and ibuprofen as needed. Two days later, 2 out of 2 preliminary blood cultures were reported positive for coagulase-negative, gram positive cocci in clusters. DB was referred to the hospital where she was admitted by Dr. Hospitalist.

Dr. Hospitalist performed a history and physical and noted an impression of sepsis from subacute bacterial endocarditis. He initiated intravenous vancomycin and ceftriaxone, repeated blood cultures, ordered an echocardiogram, and obtained an infectious disease (ID) consult. On hospital day 2, the ID consultant documented that DB had positive blood cultures for coagulase-negative staphylococci but no true evidence of sepsis. She was noted to be afebrile with a normal white blood cell count. Although the echocardiogram was pending, the ID consultant recommended that intravenous antibiotics be discontinued and that she was safe to be discharged home with follow-up blood cultures in 1 week. Later that day, the echocardiogram found a thickened aortic valve with an increased density that suggested possible vegetation.

On the morning of hospital day 3, DB had a Tmax (time to maximum plasma concentration) of 38.8 C overnight. The repeat blood cultures drawn on admission showed no growth to date. Dr. Hospitalist stopped the intravenous antibiotics and discharged DB to home. Unknown to Dr. Hospitalist at the time, the original cultures drawn at the PCP’s office were finalized as Staphylococcus lugdunensis.

One week later, DB followed up with her PCP. She continued to have fevers, myalgias, and fatigue. Blood cultures were obtained and reported the following day as 2 out of 2 positive for S. lugdunensis. DB once again returned to the hospital and was started on intravenous antibiotics. Two days into her second hospital stay, DB complained of feeling hot. She sat up in the bed and then went unconscious. After almost 2 hours of resuscitation, DB was pronounced dead. An autopsy was performed and identified the cause of death as bacterial endocarditis (S. lugdunensis) with massive vegetations and aortic valve rupture.

Complaint

DB’s mother immediately brought a claim against Dr. Hospitalist and the ID consultant from the first hospital stay. The complaint alleged that DB was inappropriately discharged from the first hospitalization without ongoing intravenous antibiotic therapy. As a result, DB missed 8 days of antibiotic treatment allowing her untreated infection to irreversibly damage her heart. The complaint further alleged that this gap in treatment was the proximate cause of DB’s death.

Scientific principles

Staphylococcus lugdunensis is a coagulase-negative staphylococcus (CNS). Like other CNS, S. lugdunensis in humans ranges from a harmless skin commensal to a life-threatening pathogen (as with infective endocarditis). Unlike other CNS, however, S. lugdunensis can cause severe disease reminiscent of the virulent infections frequently attributable to S. aureus. S. lugdunensis endocarditis is an aggressive infection that affects native valves with greater frequency than prosthetic valves in contrast to other CNS. S. lugdunensis native valve endocarditis is typically community acquired and is associated with a high rate of complications and death.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The only defense that Dr. Hospitalist offered was that he relied on his subspecialty consultant. Dr. Hospitalist argued that he was a generalist and not an expert in endocarditis or CNS. As a result, he followed the recommendations of the ID consultant and he further argued that he had the right to do so.

The plaintiff countered essentially countered with "Would you jump off the roof of a building just because someone told you to?" argument. In this case, the positive blood cultures, the history of aortic valve repair, and the suggestive echocardiogram were indisputable facts. Discovery in this case confirmed that Dr. Hospitalist never spoke with the ID consultant at any point during the first hospital stay.

Plaintiff experts argued that Dr. Hospitalist was a board-certified internist practicing hospital-based internal medicine and as such, he had or should have had the requisite knowledge, skills, and attitudes to evaluate, diagnose, and treat endocarditis. In this case, it appeared that Dr. Hospitalist "blindly" followed the recommendations of the ID consultant without considering all the evidence at hand. Plaintiff experts argued that in this situation, the standard of care required that Dr. Hospitalist question the plan of care outlined by his consultant. Had he done so, it is likely that both Dr. Hospitalist and the infectious disease consultant would have learned that the original blood cultures grew S. lugdunensis and antibiotics would never have been discontinued.

Conclusion

As the attending physicians of record, hospitalists carry the ultimate responsibility for the discharge decision. It is common to ask subspecialty consultants their opinion regarding stability for discharge and/or the need for ongoing hospital therapy. Yet, it is important for all hospitalists to remember that the consultant recommendations are just opinions that must be weighed against all the other evidence currently available. It is also helpful to have and document verbal discussions with consultants when discharge decisions are being made (and partially relied upon) with their subspecialty input.

The ID consultant in this case settled almost immediately with DB’s family. Dr. Hospitalist defended himself a little longer, but ultimately settled this case with the plaintiff for an undisclosed amount.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system.

A paralyzed patient with two stories in the chart

Story

BF was a 44-year-old man with essential hypertension who was admitted to the hospital with intractable low back pain and urinary retention. No antecedent trauma was reported. He was seen in the ED three times in the preceding week for similar complaints. In each case, he had relief with intravenous analgesia, but the symptoms quickly returned.

Prior to his admission he had lumbar radiography as well as an MRI of the lumbar spine. Plain films were unremarkable, but the MRI showed a potentially significant L4-L5 foraminal stenosis on the left and L5-S1 foraminal stenosis on the right. Neurosurgery (NS) reviewed the MRI and did not feel operative intervention was indicated. A bladder catheter was inserted in the ED for urinary retention. He was subsequently admitted to Dr. Hospitalist, who initiated medical treatment. Dr. Hospitalist’s admission impression:

"44 yo with low back pain and sciatica from foraminal stenosis. There is no neurologic compromise. The urinary retention is probably due to narcotic effects. This was discussed with neurosurgery from the ED. The patient will be admitted for observation, pain control, and physical therapy."

The following day, Dr. Hospitalist noted that BF’s pain was controlled but that he had weakness in his left foot. Dr. Hospitalist contacted NS and was reassured that if BF’s symptoms were improving with respect to pain, numbness, and/or weakness, then neurologic compromise was unlikely. Over the next 2 days, Dr. Hospitalist documented subjective improvement in BF’s pain with 4+/5 left lower extremity (LLE) strength.

On hospital day 4, BF was unable to move his legs. Dr. Hospitalist transferred BF later that day to a nearby hospital with on-site NS. An MRI performed there demonstrated a large T9-L5 epidural abscess. Despite emergent neurosurgical decompression, BF remained permanently paralyzed below the umbilicus.

Complaint

BF was naturally distraught with his paralysis. He claimed that he told everyone that he had numbness and weakness in both his legs from the very start and that nobody did anything to help him until it was too late. Expert review of the medical record found the following entries on the day of admission:

RN day note: "Patient complains of bilateral LE numbness, weak plantar, and dorsiflexion of LLE."

Physical therapy note: "Bilateral leg paresthesias from the waist down; absent anterior tibialis motor function; quadriceps weakness on the left."

Occupational therapy note: "Patient has sensation symptoms that are not reported in chart from prior MD evaluation."

Despite daily documentation by Dr. Hospitalist that BF was improving, chart entries by the nursing staff and the therapists on day 2 suggested the opposite.

On day 3, Dr. Hospitalist acknowledged that the low back pain had been better until the previous night. However, the strength was unchanged, and he was "still a little bit numb." A physical therapy note written 1 hour after Dr. Hospitalist examined BF and charted 4+/5 strength reported "slideboard transfers required due to inability to stand."

Scientific principles

Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) requires prompt recognition and proper management to avoid potentially disastrous complications. The classical diagnostic triad consists of fever, spinal pain, and neurologic deficits. Untreated abscesses will cause symptoms that progress in a typical sequence: 1) back pain, which is often focal and severe, 2) root pain, described as "shooting" or "electric shocks" in the distribution of the affected nerve root, 3) motor weakness, sensory changes, and bladder or bowel dysfunction, and then 4) paralysis. Once paralysis develops, it may quickly become irreversible.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Defense experts reinforced that SEA was a rare diagnosis and that Dr. Hospitalist appropriately performed a comprehensive admission H+P with a review of all prior ED visits and radiographic studies, and further examined BF daily and discussed BF’s case with a neurosurgical specialist who provided reassurance that no serious spinal pathology existed. Dr. Hospitalist testified that BF’s exam was dependent on patient participation and, although at times inconsistent, it suggested gradual improvement in his condition. Dr. Hospitalist also testified that he was not fully aware of the RN and therapist impressions at the time, but he trusted his own evaluations as being most accurate.

Plaintiff experts had a hard time reconciling the two conflicting stories in the chart. Additional chart review revealed that on day 2, Dr. Hospitalist inexplicably ordered a CRP and ESR that were both elevated (14.5 mg/dL and 80 mm/hr, respectively) but were never mentioned in the progress notes – nor was the rationale for ordering the studies or an impression of the results. Dr. Hospitalist testified he had no memory of ordering the studies. Moreover, the discharge summary authored by Dr. Hospitalist prior to BF transfer was contradictory to his own progress note documentation:

Hospitalist note, day 2: "There is less pain, actually no pain. The numbness or lack of sensation is improved. The ability to move his left leg is also improved; however, it is still difficult to move it and not because of pain."

Discharge summary: "There were no unifying localizing findings to suggest spinal cord compromise, and much of his symptoms may be related to pain. ... there has been no real progress made in terms of controlling his pain."

Taking all the evidence in aggregate, the plaintiff experts were critical that Dr. Hospitalist seemed unaware of the full range of patient symptoms, the laboratory evidence for an inflammatory process, the reliance on a specialist who never examined the patient, and the inadvertent or intentional chart contradictions.

Conclusion

Charting is one of the four "Cs" in reducing medicolegal risk (charting, competence, compassion, and communication). In this case, the charting by Dr. Hospitalist appeared appropriate on the surface, but inadvertently or intentionally hid the entire clinical picture. The difference in documentation between hospitalist and the RN/therapy notes in this case seems hard to explain, but various health care providers may reasonably see and chart diverse findings and impressions. However, the conflicting documentation between several of Dr. Hospitalist’s own notes severely damaged his credibility.

This case was settled for an undisclosed amount in favor of the plaintiff.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read earlier columns online at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Story

BF was a 44-year-old man with essential hypertension who was admitted to the hospital with intractable low back pain and urinary retention. No antecedent trauma was reported. He was seen in the ED three times in the preceding week for similar complaints. In each case, he had relief with intravenous analgesia, but the symptoms quickly returned.

Prior to his admission he had lumbar radiography as well as an MRI of the lumbar spine. Plain films were unremarkable, but the MRI showed a potentially significant L4-L5 foraminal stenosis on the left and L5-S1 foraminal stenosis on the right. Neurosurgery (NS) reviewed the MRI and did not feel operative intervention was indicated. A bladder catheter was inserted in the ED for urinary retention. He was subsequently admitted to Dr. Hospitalist, who initiated medical treatment. Dr. Hospitalist’s admission impression:

"44 yo with low back pain and sciatica from foraminal stenosis. There is no neurologic compromise. The urinary retention is probably due to narcotic effects. This was discussed with neurosurgery from the ED. The patient will be admitted for observation, pain control, and physical therapy."

The following day, Dr. Hospitalist noted that BF’s pain was controlled but that he had weakness in his left foot. Dr. Hospitalist contacted NS and was reassured that if BF’s symptoms were improving with respect to pain, numbness, and/or weakness, then neurologic compromise was unlikely. Over the next 2 days, Dr. Hospitalist documented subjective improvement in BF’s pain with 4+/5 left lower extremity (LLE) strength.

On hospital day 4, BF was unable to move his legs. Dr. Hospitalist transferred BF later that day to a nearby hospital with on-site NS. An MRI performed there demonstrated a large T9-L5 epidural abscess. Despite emergent neurosurgical decompression, BF remained permanently paralyzed below the umbilicus.

Complaint

BF was naturally distraught with his paralysis. He claimed that he told everyone that he had numbness and weakness in both his legs from the very start and that nobody did anything to help him until it was too late. Expert review of the medical record found the following entries on the day of admission:

RN day note: "Patient complains of bilateral LE numbness, weak plantar, and dorsiflexion of LLE."

Physical therapy note: "Bilateral leg paresthesias from the waist down; absent anterior tibialis motor function; quadriceps weakness on the left."

Occupational therapy note: "Patient has sensation symptoms that are not reported in chart from prior MD evaluation."

Despite daily documentation by Dr. Hospitalist that BF was improving, chart entries by the nursing staff and the therapists on day 2 suggested the opposite.

On day 3, Dr. Hospitalist acknowledged that the low back pain had been better until the previous night. However, the strength was unchanged, and he was "still a little bit numb." A physical therapy note written 1 hour after Dr. Hospitalist examined BF and charted 4+/5 strength reported "slideboard transfers required due to inability to stand."

Scientific principles

Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) requires prompt recognition and proper management to avoid potentially disastrous complications. The classical diagnostic triad consists of fever, spinal pain, and neurologic deficits. Untreated abscesses will cause symptoms that progress in a typical sequence: 1) back pain, which is often focal and severe, 2) root pain, described as "shooting" or "electric shocks" in the distribution of the affected nerve root, 3) motor weakness, sensory changes, and bladder or bowel dysfunction, and then 4) paralysis. Once paralysis develops, it may quickly become irreversible.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Defense experts reinforced that SEA was a rare diagnosis and that Dr. Hospitalist appropriately performed a comprehensive admission H+P with a review of all prior ED visits and radiographic studies, and further examined BF daily and discussed BF’s case with a neurosurgical specialist who provided reassurance that no serious spinal pathology existed. Dr. Hospitalist testified that BF’s exam was dependent on patient participation and, although at times inconsistent, it suggested gradual improvement in his condition. Dr. Hospitalist also testified that he was not fully aware of the RN and therapist impressions at the time, but he trusted his own evaluations as being most accurate.

Plaintiff experts had a hard time reconciling the two conflicting stories in the chart. Additional chart review revealed that on day 2, Dr. Hospitalist inexplicably ordered a CRP and ESR that were both elevated (14.5 mg/dL and 80 mm/hr, respectively) but were never mentioned in the progress notes – nor was the rationale for ordering the studies or an impression of the results. Dr. Hospitalist testified he had no memory of ordering the studies. Moreover, the discharge summary authored by Dr. Hospitalist prior to BF transfer was contradictory to his own progress note documentation:

Hospitalist note, day 2: "There is less pain, actually no pain. The numbness or lack of sensation is improved. The ability to move his left leg is also improved; however, it is still difficult to move it and not because of pain."

Discharge summary: "There were no unifying localizing findings to suggest spinal cord compromise, and much of his symptoms may be related to pain. ... there has been no real progress made in terms of controlling his pain."

Taking all the evidence in aggregate, the plaintiff experts were critical that Dr. Hospitalist seemed unaware of the full range of patient symptoms, the laboratory evidence for an inflammatory process, the reliance on a specialist who never examined the patient, and the inadvertent or intentional chart contradictions.

Conclusion

Charting is one of the four "Cs" in reducing medicolegal risk (charting, competence, compassion, and communication). In this case, the charting by Dr. Hospitalist appeared appropriate on the surface, but inadvertently or intentionally hid the entire clinical picture. The difference in documentation between hospitalist and the RN/therapy notes in this case seems hard to explain, but various health care providers may reasonably see and chart diverse findings and impressions. However, the conflicting documentation between several of Dr. Hospitalist’s own notes severely damaged his credibility.

This case was settled for an undisclosed amount in favor of the plaintiff.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read earlier columns online at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Story

BF was a 44-year-old man with essential hypertension who was admitted to the hospital with intractable low back pain and urinary retention. No antecedent trauma was reported. He was seen in the ED three times in the preceding week for similar complaints. In each case, he had relief with intravenous analgesia, but the symptoms quickly returned.

Prior to his admission he had lumbar radiography as well as an MRI of the lumbar spine. Plain films were unremarkable, but the MRI showed a potentially significant L4-L5 foraminal stenosis on the left and L5-S1 foraminal stenosis on the right. Neurosurgery (NS) reviewed the MRI and did not feel operative intervention was indicated. A bladder catheter was inserted in the ED for urinary retention. He was subsequently admitted to Dr. Hospitalist, who initiated medical treatment. Dr. Hospitalist’s admission impression:

"44 yo with low back pain and sciatica from foraminal stenosis. There is no neurologic compromise. The urinary retention is probably due to narcotic effects. This was discussed with neurosurgery from the ED. The patient will be admitted for observation, pain control, and physical therapy."

The following day, Dr. Hospitalist noted that BF’s pain was controlled but that he had weakness in his left foot. Dr. Hospitalist contacted NS and was reassured that if BF’s symptoms were improving with respect to pain, numbness, and/or weakness, then neurologic compromise was unlikely. Over the next 2 days, Dr. Hospitalist documented subjective improvement in BF’s pain with 4+/5 left lower extremity (LLE) strength.

On hospital day 4, BF was unable to move his legs. Dr. Hospitalist transferred BF later that day to a nearby hospital with on-site NS. An MRI performed there demonstrated a large T9-L5 epidural abscess. Despite emergent neurosurgical decompression, BF remained permanently paralyzed below the umbilicus.

Complaint

BF was naturally distraught with his paralysis. He claimed that he told everyone that he had numbness and weakness in both his legs from the very start and that nobody did anything to help him until it was too late. Expert review of the medical record found the following entries on the day of admission:

RN day note: "Patient complains of bilateral LE numbness, weak plantar, and dorsiflexion of LLE."

Physical therapy note: "Bilateral leg paresthesias from the waist down; absent anterior tibialis motor function; quadriceps weakness on the left."

Occupational therapy note: "Patient has sensation symptoms that are not reported in chart from prior MD evaluation."

Despite daily documentation by Dr. Hospitalist that BF was improving, chart entries by the nursing staff and the therapists on day 2 suggested the opposite.

On day 3, Dr. Hospitalist acknowledged that the low back pain had been better until the previous night. However, the strength was unchanged, and he was "still a little bit numb." A physical therapy note written 1 hour after Dr. Hospitalist examined BF and charted 4+/5 strength reported "slideboard transfers required due to inability to stand."

Scientific principles

Spinal epidural abscess (SEA) requires prompt recognition and proper management to avoid potentially disastrous complications. The classical diagnostic triad consists of fever, spinal pain, and neurologic deficits. Untreated abscesses will cause symptoms that progress in a typical sequence: 1) back pain, which is often focal and severe, 2) root pain, described as "shooting" or "electric shocks" in the distribution of the affected nerve root, 3) motor weakness, sensory changes, and bladder or bowel dysfunction, and then 4) paralysis. Once paralysis develops, it may quickly become irreversible.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

Defense experts reinforced that SEA was a rare diagnosis and that Dr. Hospitalist appropriately performed a comprehensive admission H+P with a review of all prior ED visits and radiographic studies, and further examined BF daily and discussed BF’s case with a neurosurgical specialist who provided reassurance that no serious spinal pathology existed. Dr. Hospitalist testified that BF’s exam was dependent on patient participation and, although at times inconsistent, it suggested gradual improvement in his condition. Dr. Hospitalist also testified that he was not fully aware of the RN and therapist impressions at the time, but he trusted his own evaluations as being most accurate.

Plaintiff experts had a hard time reconciling the two conflicting stories in the chart. Additional chart review revealed that on day 2, Dr. Hospitalist inexplicably ordered a CRP and ESR that were both elevated (14.5 mg/dL and 80 mm/hr, respectively) but were never mentioned in the progress notes – nor was the rationale for ordering the studies or an impression of the results. Dr. Hospitalist testified he had no memory of ordering the studies. Moreover, the discharge summary authored by Dr. Hospitalist prior to BF transfer was contradictory to his own progress note documentation:

Hospitalist note, day 2: "There is less pain, actually no pain. The numbness or lack of sensation is improved. The ability to move his left leg is also improved; however, it is still difficult to move it and not because of pain."

Discharge summary: "There were no unifying localizing findings to suggest spinal cord compromise, and much of his symptoms may be related to pain. ... there has been no real progress made in terms of controlling his pain."

Taking all the evidence in aggregate, the plaintiff experts were critical that Dr. Hospitalist seemed unaware of the full range of patient symptoms, the laboratory evidence for an inflammatory process, the reliance on a specialist who never examined the patient, and the inadvertent or intentional chart contradictions.

Conclusion

Charting is one of the four "Cs" in reducing medicolegal risk (charting, competence, compassion, and communication). In this case, the charting by Dr. Hospitalist appeared appropriate on the surface, but inadvertently or intentionally hid the entire clinical picture. The difference in documentation between hospitalist and the RN/therapy notes in this case seems hard to explain, but various health care providers may reasonably see and chart diverse findings and impressions. However, the conflicting documentation between several of Dr. Hospitalist’s own notes severely damaged his credibility.

This case was settled for an undisclosed amount in favor of the plaintiff.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has been involved in peer review both within and outside the legal system. Read earlier columns online at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Medicolegal Lessons: A question of duty

Story

ML was an 83-year-old woman who presented from her assisted-living facility to her local emergency room with abdominal pain.

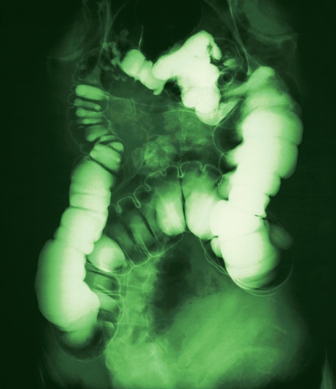

She described acute-onset epigastric pain within minutes of her evening meal. The pain was rated 5 out of 10 and was associated with some nausea but no emesis. ML had a past medical history of irritable bowel symptoms along with diverticulosis, but she was otherwise healthy and took no regular medications except for occasional loperamide. Her CBC, amylase, lipase, and chemistry panels were normal. CT scan of the abdomen showed mildly dilated loops of small bowel.

ML was admitted to the hospital by her family physician, who consulted a gastroenterologist the following morning. The gastroenterologist concluded that ML was most likely suffering from food intolerance and recommended bowel rest and observation.

ML continued to have the pain and was unable to advance her diet. On hospital day 2, the GI consultant noted that ML’s abdomen was soft and nondistended, but he ordered an acute abdominal series and requested to be called with the results. The study was not completed until 5:30 p.m. Later that evening during a routine chart check, ML’s nurse noted that the acute abdominal series had been completed, but not read. She paged the hospitalist on call to review the film so that she could contact the GI consultant pursuant to his order.

Dr. Hospitalist reviewed the film and called the nurse back to report that the film showed no free air but the colon was dilated. The nurse subsequently called the GI consultant and relayed the information. No new orders were received.

At 7 a.m. on hospital day 3, ML developed mental status changes. Her abdomen was now noted to be distended with rigidity. ML was evaluated by her family physician and the GI consultant.

A surgical consult was obtained along with further imaging, which confirmed a small bowel obstruction (SBO) with massively dilated small bowel. Morning labs also showed acute kidney injury. Formal radiology review of the abdominal series looked at by Dr. Hospitalist established the presence of significant small bowel dilatation highly concerning for SBO. ML was transferred to a larger hospital where she eventually underwent an exploratory laparotomy for perforated bowel. Following a tumultuous postoperative course including dialysis, ML expired 1 month later.

Complaint

ML’s daughter was a pediatrician at a major teaching institution nearby. She was frustrated that the original CT showed dilated small bowel and that the conclusion of her treating doctors was that her mother was suffering from "food intolerance." Together with her father, they filed suit against the hospital, the GI consultant, and Dr. Hospitalist.

ML’s family alleged that ML had small bowel obstruction from the start and should have had surgical involvement soon enough to intervene before she ultimately perforated her bowel. Surgical repair prior to perforation would have significantly changed ML’s outcome.

They further alleged that Dr. Hospitalist was negligent in her review of the abdominal radiographs and she had a duty to see and examine ML, communicate directly with the GI consultant, and obtain a STAT surgical consult.

Scientific principles

Small bowel obstruction occurs when the normal flow of intestinal contents is interrupted, and it is usually confirmed by plain abdominal radiography.

The most frequent causes are postoperative adhesions and hernias, which cause extrinsic compression of the intestine. Obstruction leads to dilation of the stomach and small intestine proximal to the blockage, while distal to the blockage the bowel will decompress as luminal contents are passed. Symptoms include obstipation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. As the small bowel dilates, its blood flow can be compromised, leading to strangulation and sepsis.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable sign or symptom differentiating patients with strangulation or impending strangulation from those in whom surgery will not be necessary.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

For the night in question, Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she had two roles and only one of them involved ML.

First, Dr. Hospitalist was responsible for admissions and cross-coverage for her own group’s patients at night. ML was not a patient of Dr. Hospitalist or her group. ML was being cared for by her own family physician and his practice group 24/7.

Second, Dr. Hospitalist was the hospital’s overnight "house doctor" for codes, IV access, radiology "wet reads," and other emergencies. It was in this capacity that Dr. Hospitalist was contacted. Dr. Hospitalist was not a radiologist. As a house doctor, Dr. Hospitalist would be expected to look for serious and life-threatening findings and to rule out the presence of free air. Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she was never asked to see ML by the attending physician or even by the nurse.

The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist had a duty to question the nurse regarding ML’s condition and, because of the evidence for obstruction on the film, see ML for an assessment. The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist’s misinterpretation of the film (i.e., colon dilatation in the face of obvious small bowel dilatation) represented gross incompetence.

Dr. Hospitalist testified that she had no memory of ML, this case, or what she may or may not have told the nurse that night. ML’s medical record confirms that Dr. Hospitalist wrote no orders or charted any notes on her. The only documentation of Dr. Hospitalist’s "wet read" was in ML’s nursing notes.

The GI consultant testified that he had no memory of his call from the nurse with the radiograph results. The nurse testified that she wouldn’t have written "colon dilatation" if Dr. Hospitalist had told her it was small bowel.

Conclusion

The "house doc" role typically encompasses a limited scope of responsibility. But all physicians carry a professional duty to the patients that we become involved with.

By performing a "wet read" on a film of ML, Dr. Hospitalist established a doctor-patient relationship. It would have been prudent for Dr. Hospitalist to record her film interpretation herself (thus creating an opportunity for brief chart review), and to call the GI consultant with the information instead of relying on the nurse. A 1-minute conversation between Dr. Hospitalist and the GI consultant may have led to further intervention by either party.

Ultimately this case was resolved for an undisclosed amount. In the "house doc" role, Dr. Hospitalist was functioning as an employee of the hospital (despite being an independent contractor), and there were hospital care issues independent of Dr. Hospitalist. However, Dr. Hospitalist could have avoided her role in this suit with better documentation and communication.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. Read earlier columns online at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Medicolegal Review has the opportunity to become the morbidity and mortality conference of the modern era. Each month, this column presents a case vignette that explores some aspect of medicine and the applicable standard of care.

The more we share in our collective failures, the less likely we are to repeat those same mistakes.

Medicolegal Review has the opportunity to become the morbidity and mortality conference of the modern era. Each month, this column presents a case vignette that explores some aspect of medicine and the applicable standard of care.

The more we share in our collective failures, the less likely we are to repeat those same mistakes.

Medicolegal Review has the opportunity to become the morbidity and mortality conference of the modern era. Each month, this column presents a case vignette that explores some aspect of medicine and the applicable standard of care.

The more we share in our collective failures, the less likely we are to repeat those same mistakes.

Story

ML was an 83-year-old woman who presented from her assisted-living facility to her local emergency room with abdominal pain.

She described acute-onset epigastric pain within minutes of her evening meal. The pain was rated 5 out of 10 and was associated with some nausea but no emesis. ML had a past medical history of irritable bowel symptoms along with diverticulosis, but she was otherwise healthy and took no regular medications except for occasional loperamide. Her CBC, amylase, lipase, and chemistry panels were normal. CT scan of the abdomen showed mildly dilated loops of small bowel.

ML was admitted to the hospital by her family physician, who consulted a gastroenterologist the following morning. The gastroenterologist concluded that ML was most likely suffering from food intolerance and recommended bowel rest and observation.

ML continued to have the pain and was unable to advance her diet. On hospital day 2, the GI consultant noted that ML’s abdomen was soft and nondistended, but he ordered an acute abdominal series and requested to be called with the results. The study was not completed until 5:30 p.m. Later that evening during a routine chart check, ML’s nurse noted that the acute abdominal series had been completed, but not read. She paged the hospitalist on call to review the film so that she could contact the GI consultant pursuant to his order.

Dr. Hospitalist reviewed the film and called the nurse back to report that the film showed no free air but the colon was dilated. The nurse subsequently called the GI consultant and relayed the information. No new orders were received.

At 7 a.m. on hospital day 3, ML developed mental status changes. Her abdomen was now noted to be distended with rigidity. ML was evaluated by her family physician and the GI consultant.

A surgical consult was obtained along with further imaging, which confirmed a small bowel obstruction (SBO) with massively dilated small bowel. Morning labs also showed acute kidney injury. Formal radiology review of the abdominal series looked at by Dr. Hospitalist established the presence of significant small bowel dilatation highly concerning for SBO. ML was transferred to a larger hospital where she eventually underwent an exploratory laparotomy for perforated bowel. Following a tumultuous postoperative course including dialysis, ML expired 1 month later.

Complaint

ML’s daughter was a pediatrician at a major teaching institution nearby. She was frustrated that the original CT showed dilated small bowel and that the conclusion of her treating doctors was that her mother was suffering from "food intolerance." Together with her father, they filed suit against the hospital, the GI consultant, and Dr. Hospitalist.

ML’s family alleged that ML had small bowel obstruction from the start and should have had surgical involvement soon enough to intervene before she ultimately perforated her bowel. Surgical repair prior to perforation would have significantly changed ML’s outcome.

They further alleged that Dr. Hospitalist was negligent in her review of the abdominal radiographs and she had a duty to see and examine ML, communicate directly with the GI consultant, and obtain a STAT surgical consult.

Scientific principles

Small bowel obstruction occurs when the normal flow of intestinal contents is interrupted, and it is usually confirmed by plain abdominal radiography.

The most frequent causes are postoperative adhesions and hernias, which cause extrinsic compression of the intestine. Obstruction leads to dilation of the stomach and small intestine proximal to the blockage, while distal to the blockage the bowel will decompress as luminal contents are passed. Symptoms include obstipation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. As the small bowel dilates, its blood flow can be compromised, leading to strangulation and sepsis.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable sign or symptom differentiating patients with strangulation or impending strangulation from those in whom surgery will not be necessary.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

For the night in question, Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she had two roles and only one of them involved ML.

First, Dr. Hospitalist was responsible for admissions and cross-coverage for her own group’s patients at night. ML was not a patient of Dr. Hospitalist or her group. ML was being cared for by her own family physician and his practice group 24/7.

Second, Dr. Hospitalist was the hospital’s overnight "house doctor" for codes, IV access, radiology "wet reads," and other emergencies. It was in this capacity that Dr. Hospitalist was contacted. Dr. Hospitalist was not a radiologist. As a house doctor, Dr. Hospitalist would be expected to look for serious and life-threatening findings and to rule out the presence of free air. Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she was never asked to see ML by the attending physician or even by the nurse.

The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist had a duty to question the nurse regarding ML’s condition and, because of the evidence for obstruction on the film, see ML for an assessment. The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist’s misinterpretation of the film (i.e., colon dilatation in the face of obvious small bowel dilatation) represented gross incompetence.

Dr. Hospitalist testified that she had no memory of ML, this case, or what she may or may not have told the nurse that night. ML’s medical record confirms that Dr. Hospitalist wrote no orders or charted any notes on her. The only documentation of Dr. Hospitalist’s "wet read" was in ML’s nursing notes.

The GI consultant testified that he had no memory of his call from the nurse with the radiograph results. The nurse testified that she wouldn’t have written "colon dilatation" if Dr. Hospitalist had told her it was small bowel.

Conclusion

The "house doc" role typically encompasses a limited scope of responsibility. But all physicians carry a professional duty to the patients that we become involved with.

By performing a "wet read" on a film of ML, Dr. Hospitalist established a doctor-patient relationship. It would have been prudent for Dr. Hospitalist to record her film interpretation herself (thus creating an opportunity for brief chart review), and to call the GI consultant with the information instead of relying on the nurse. A 1-minute conversation between Dr. Hospitalist and the GI consultant may have led to further intervention by either party.

Ultimately this case was resolved for an undisclosed amount. In the "house doc" role, Dr. Hospitalist was functioning as an employee of the hospital (despite being an independent contractor), and there were hospital care issues independent of Dr. Hospitalist. However, Dr. Hospitalist could have avoided her role in this suit with better documentation and communication.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. Read earlier columns online at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

Story

ML was an 83-year-old woman who presented from her assisted-living facility to her local emergency room with abdominal pain.

She described acute-onset epigastric pain within minutes of her evening meal. The pain was rated 5 out of 10 and was associated with some nausea but no emesis. ML had a past medical history of irritable bowel symptoms along with diverticulosis, but she was otherwise healthy and took no regular medications except for occasional loperamide. Her CBC, amylase, lipase, and chemistry panels were normal. CT scan of the abdomen showed mildly dilated loops of small bowel.

ML was admitted to the hospital by her family physician, who consulted a gastroenterologist the following morning. The gastroenterologist concluded that ML was most likely suffering from food intolerance and recommended bowel rest and observation.

ML continued to have the pain and was unable to advance her diet. On hospital day 2, the GI consultant noted that ML’s abdomen was soft and nondistended, but he ordered an acute abdominal series and requested to be called with the results. The study was not completed until 5:30 p.m. Later that evening during a routine chart check, ML’s nurse noted that the acute abdominal series had been completed, but not read. She paged the hospitalist on call to review the film so that she could contact the GI consultant pursuant to his order.

Dr. Hospitalist reviewed the film and called the nurse back to report that the film showed no free air but the colon was dilated. The nurse subsequently called the GI consultant and relayed the information. No new orders were received.

At 7 a.m. on hospital day 3, ML developed mental status changes. Her abdomen was now noted to be distended with rigidity. ML was evaluated by her family physician and the GI consultant.

A surgical consult was obtained along with further imaging, which confirmed a small bowel obstruction (SBO) with massively dilated small bowel. Morning labs also showed acute kidney injury. Formal radiology review of the abdominal series looked at by Dr. Hospitalist established the presence of significant small bowel dilatation highly concerning for SBO. ML was transferred to a larger hospital where she eventually underwent an exploratory laparotomy for perforated bowel. Following a tumultuous postoperative course including dialysis, ML expired 1 month later.

Complaint

ML’s daughter was a pediatrician at a major teaching institution nearby. She was frustrated that the original CT showed dilated small bowel and that the conclusion of her treating doctors was that her mother was suffering from "food intolerance." Together with her father, they filed suit against the hospital, the GI consultant, and Dr. Hospitalist.

ML’s family alleged that ML had small bowel obstruction from the start and should have had surgical involvement soon enough to intervene before she ultimately perforated her bowel. Surgical repair prior to perforation would have significantly changed ML’s outcome.

They further alleged that Dr. Hospitalist was negligent in her review of the abdominal radiographs and she had a duty to see and examine ML, communicate directly with the GI consultant, and obtain a STAT surgical consult.

Scientific principles

Small bowel obstruction occurs when the normal flow of intestinal contents is interrupted, and it is usually confirmed by plain abdominal radiography.

The most frequent causes are postoperative adhesions and hernias, which cause extrinsic compression of the intestine. Obstruction leads to dilation of the stomach and small intestine proximal to the blockage, while distal to the blockage the bowel will decompress as luminal contents are passed. Symptoms include obstipation, nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. As the small bowel dilates, its blood flow can be compromised, leading to strangulation and sepsis.

Unfortunately, there is no reliable sign or symptom differentiating patients with strangulation or impending strangulation from those in whom surgery will not be necessary.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

For the night in question, Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she had two roles and only one of them involved ML.

First, Dr. Hospitalist was responsible for admissions and cross-coverage for her own group’s patients at night. ML was not a patient of Dr. Hospitalist or her group. ML was being cared for by her own family physician and his practice group 24/7.

Second, Dr. Hospitalist was the hospital’s overnight "house doctor" for codes, IV access, radiology "wet reads," and other emergencies. It was in this capacity that Dr. Hospitalist was contacted. Dr. Hospitalist was not a radiologist. As a house doctor, Dr. Hospitalist would be expected to look for serious and life-threatening findings and to rule out the presence of free air. Dr. Hospitalist asserted that she was never asked to see ML by the attending physician or even by the nurse.

The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist had a duty to question the nurse regarding ML’s condition and, because of the evidence for obstruction on the film, see ML for an assessment. The family argued that Dr. Hospitalist’s misinterpretation of the film (i.e., colon dilatation in the face of obvious small bowel dilatation) represented gross incompetence.

Dr. Hospitalist testified that she had no memory of ML, this case, or what she may or may not have told the nurse that night. ML’s medical record confirms that Dr. Hospitalist wrote no orders or charted any notes on her. The only documentation of Dr. Hospitalist’s "wet read" was in ML’s nursing notes.

The GI consultant testified that he had no memory of his call from the nurse with the radiograph results. The nurse testified that she wouldn’t have written "colon dilatation" if Dr. Hospitalist had told her it was small bowel.

Conclusion

The "house doc" role typically encompasses a limited scope of responsibility. But all physicians carry a professional duty to the patients that we become involved with.

By performing a "wet read" on a film of ML, Dr. Hospitalist established a doctor-patient relationship. It would have been prudent for Dr. Hospitalist to record her film interpretation herself (thus creating an opportunity for brief chart review), and to call the GI consultant with the information instead of relying on the nurse. A 1-minute conversation between Dr. Hospitalist and the GI consultant may have led to further intervention by either party.

Ultimately this case was resolved for an undisclosed amount. In the "house doc" role, Dr. Hospitalist was functioning as an employee of the hospital (despite being an independent contractor), and there were hospital care issues independent of Dr. Hospitalist. However, Dr. Hospitalist could have avoided her role in this suit with better documentation and communication.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. Read earlier columns online at ehospitalistnews.com/Lessons.

VTE and a debatable dose

Mr. SS was a 48-year-old man who presented to the emergency department with complaints of right calf and ankle swelling for 1 day associated with mild shortness of breath. Lower extremity ultrasound quickly confirmed an acute right femoral and popliteal deep vein thrombosis. CT angiogram of the chest was negative for pulmonary embolus (PE). Two weeks earlier, Mr. SS had suffered a traumatic right intertrochanteric hip fracture when he fell off a ladder at home. At that time, he underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the right hip without complication. He was discharged home on warfarin for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis. At the time of his return to the hospital, his INR was 1.4 and his current level of activity was touch toe weight-bearing of the right leg.

The ED physician paged the hospitalist on call, who was already at home for the evening. Following a telephone discussion, Mr. SS was given 7.5 mg of subcutaneous fondaparinux (Arixtra) in the ED. Mr. SS was then transferred up to the regular nursing floor and admitted by a house doctor employed by the hospital. The house doctor continued the fondaparinux at a dose of 7.5mg daily.

At approximately 10 a.m. the following day, Mr. SS was up in the bathroom. He became acutely short of breath and called out for help. Before he could return to bed, he was noted to be ashen in appearance, and he lost consciousness along with his pulse and respirations. A code blue was called, but despite more than an hour of resuscitation, Mr. SS expired. An autopsy was performed and confirmed a large saddle pulmonary embolism as the cause of death. The hospitalist on call never saw Mr. SS before he died.

Complaint

Mr. SS was an English professor at the local university. He left behind a wife and four children. A relation in the medical field reviewed the records and discovered that Mr. SS only received 7.5 mg of fondaparinux despite the fact that Mr. SS weighed more than 100 kg (265 pounds). The Food and Drug Administration–approved dose of Arixtra for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism is based on tertile of weight (5 mg if less than 50 kg; 7.5 mg if between 50-100 kg; and 10 mg if more than 100 kg). The complaint alleged that Mr. SS was underdosed and therefore needlessly developed a pulmonary embolism. Had Mr. SS received the FDA-approved dose of fondaparinux based on his weight, he would be alive and well today.

The complaint was filed against the ED physician, the hospitalist on call, and the house doctor.

Scientific principles

Outcome studies confirm that the vast majority of patients (more than 95%) who receive adequate anticoagulation in the setting of acute venous thromboembolism (DVT/PE) will be alive at discharge, 30 days, and at 1 year. In fact, of all the variables possibly associated with VTE recurrence, the only one demonstrated by logistic regression to be statistically significant with respect to VTE recurrence is the failure to achieve and maintain adequate anticoagulation. Properly conducted phase II dose ranging studies with Arixtra (REMBRANDT) ultimately led to the tertile weight-based dosing regimen that was studied in the phase III trial (MATISSE) that led to Arixtra’s FDA approval and the recommendations for dosing in the Arixtra package insert.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The defense argued that the dosing recommendations in the Arixtra package insert were guidelines and not in and of themselves the standard of care. Mr. SS did not have a normal INR on presentation and the defense argued it was reasonable clinical judgment on behalf of the providers involved to use that dose that best balanced efficacy and safety. The defense further argued that based on the timing of the PE (approximately 12 hours after the 7.5 mg fondaparinux dose), Mr. SS should have been in a therapeutic range in regard to drug concentration.

In other words, Mr. SS still would have had more drug in his body 12 hours after a 7.5-mg dose than he would at 24 hours following a 10-mg dose. As such, Mr. SS would have had a fatal PE regardless. The plaintiff attacked the clinical judgment defense as unreasonable. There simply was no reason not to use the proven and recommended dose for SS. To do anything less was unnecessary experimentation on Mr. SS by the physicians involved.

Ironically, during deposition testimony, the hospitalist on call confirmed that he never discussed the Arixtra dose with the ED physician. He further testified that had he known that the ED physician was only going to give 7.5 mg, he would have increased the dose to 10 mg himself.

Conclusion

It is commonplace for hospitalists to discuss admission plans of care with our ED colleagues. Rarely, however, do we have such discussions with the same granularity as if we were writing the actual orders ourselves. It is important to remember that if we rely on our ED colleagues (or a house doctor) to fulfill our responsibilities in that regard, we can get trapped by a clinical judgment decision that doesn’t really match what we would have done under the same circumstances. The hospitalist in this case never even saw Mr. SS and he didn’t write the Arixtra order, yet he was deemed culpable for the outcome. Based on deposition testimony, it was readily apparent that the ED physician simply did not know the appropriate Arixtra dosing schedule for a patient weighing more than 100 kg. The jury, however, was ultimately persuaded by the defense arguments and returned a full defense verdict in this case.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has relationships with oral anticoagulant makers Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi Sankyo.

Mr. SS was a 48-year-old man who presented to the emergency department with complaints of right calf and ankle swelling for 1 day associated with mild shortness of breath. Lower extremity ultrasound quickly confirmed an acute right femoral and popliteal deep vein thrombosis. CT angiogram of the chest was negative for pulmonary embolus (PE). Two weeks earlier, Mr. SS had suffered a traumatic right intertrochanteric hip fracture when he fell off a ladder at home. At that time, he underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the right hip without complication. He was discharged home on warfarin for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis. At the time of his return to the hospital, his INR was 1.4 and his current level of activity was touch toe weight-bearing of the right leg.

The ED physician paged the hospitalist on call, who was already at home for the evening. Following a telephone discussion, Mr. SS was given 7.5 mg of subcutaneous fondaparinux (Arixtra) in the ED. Mr. SS was then transferred up to the regular nursing floor and admitted by a house doctor employed by the hospital. The house doctor continued the fondaparinux at a dose of 7.5mg daily.

At approximately 10 a.m. the following day, Mr. SS was up in the bathroom. He became acutely short of breath and called out for help. Before he could return to bed, he was noted to be ashen in appearance, and he lost consciousness along with his pulse and respirations. A code blue was called, but despite more than an hour of resuscitation, Mr. SS expired. An autopsy was performed and confirmed a large saddle pulmonary embolism as the cause of death. The hospitalist on call never saw Mr. SS before he died.

Complaint

Mr. SS was an English professor at the local university. He left behind a wife and four children. A relation in the medical field reviewed the records and discovered that Mr. SS only received 7.5 mg of fondaparinux despite the fact that Mr. SS weighed more than 100 kg (265 pounds). The Food and Drug Administration–approved dose of Arixtra for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism is based on tertile of weight (5 mg if less than 50 kg; 7.5 mg if between 50-100 kg; and 10 mg if more than 100 kg). The complaint alleged that Mr. SS was underdosed and therefore needlessly developed a pulmonary embolism. Had Mr. SS received the FDA-approved dose of fondaparinux based on his weight, he would be alive and well today.

The complaint was filed against the ED physician, the hospitalist on call, and the house doctor.

Scientific principles

Outcome studies confirm that the vast majority of patients (more than 95%) who receive adequate anticoagulation in the setting of acute venous thromboembolism (DVT/PE) will be alive at discharge, 30 days, and at 1 year. In fact, of all the variables possibly associated with VTE recurrence, the only one demonstrated by logistic regression to be statistically significant with respect to VTE recurrence is the failure to achieve and maintain adequate anticoagulation. Properly conducted phase II dose ranging studies with Arixtra (REMBRANDT) ultimately led to the tertile weight-based dosing regimen that was studied in the phase III trial (MATISSE) that led to Arixtra’s FDA approval and the recommendations for dosing in the Arixtra package insert.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The defense argued that the dosing recommendations in the Arixtra package insert were guidelines and not in and of themselves the standard of care. Mr. SS did not have a normal INR on presentation and the defense argued it was reasonable clinical judgment on behalf of the providers involved to use that dose that best balanced efficacy and safety. The defense further argued that based on the timing of the PE (approximately 12 hours after the 7.5 mg fondaparinux dose), Mr. SS should have been in a therapeutic range in regard to drug concentration.

In other words, Mr. SS still would have had more drug in his body 12 hours after a 7.5-mg dose than he would at 24 hours following a 10-mg dose. As such, Mr. SS would have had a fatal PE regardless. The plaintiff attacked the clinical judgment defense as unreasonable. There simply was no reason not to use the proven and recommended dose for SS. To do anything less was unnecessary experimentation on Mr. SS by the physicians involved.

Ironically, during deposition testimony, the hospitalist on call confirmed that he never discussed the Arixtra dose with the ED physician. He further testified that had he known that the ED physician was only going to give 7.5 mg, he would have increased the dose to 10 mg himself.

Conclusion

It is commonplace for hospitalists to discuss admission plans of care with our ED colleagues. Rarely, however, do we have such discussions with the same granularity as if we were writing the actual orders ourselves. It is important to remember that if we rely on our ED colleagues (or a house doctor) to fulfill our responsibilities in that regard, we can get trapped by a clinical judgment decision that doesn’t really match what we would have done under the same circumstances. The hospitalist in this case never even saw Mr. SS and he didn’t write the Arixtra order, yet he was deemed culpable for the outcome. Based on deposition testimony, it was readily apparent that the ED physician simply did not know the appropriate Arixtra dosing schedule for a patient weighing more than 100 kg. The jury, however, was ultimately persuaded by the defense arguments and returned a full defense verdict in this case.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has relationships with oral anticoagulant makers Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi Sankyo.

Mr. SS was a 48-year-old man who presented to the emergency department with complaints of right calf and ankle swelling for 1 day associated with mild shortness of breath. Lower extremity ultrasound quickly confirmed an acute right femoral and popliteal deep vein thrombosis. CT angiogram of the chest was negative for pulmonary embolus (PE). Two weeks earlier, Mr. SS had suffered a traumatic right intertrochanteric hip fracture when he fell off a ladder at home. At that time, he underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the right hip without complication. He was discharged home on warfarin for venous thromboembolism (VTE) prophylaxis. At the time of his return to the hospital, his INR was 1.4 and his current level of activity was touch toe weight-bearing of the right leg.

The ED physician paged the hospitalist on call, who was already at home for the evening. Following a telephone discussion, Mr. SS was given 7.5 mg of subcutaneous fondaparinux (Arixtra) in the ED. Mr. SS was then transferred up to the regular nursing floor and admitted by a house doctor employed by the hospital. The house doctor continued the fondaparinux at a dose of 7.5mg daily.

At approximately 10 a.m. the following day, Mr. SS was up in the bathroom. He became acutely short of breath and called out for help. Before he could return to bed, he was noted to be ashen in appearance, and he lost consciousness along with his pulse and respirations. A code blue was called, but despite more than an hour of resuscitation, Mr. SS expired. An autopsy was performed and confirmed a large saddle pulmonary embolism as the cause of death. The hospitalist on call never saw Mr. SS before he died.

Complaint

Mr. SS was an English professor at the local university. He left behind a wife and four children. A relation in the medical field reviewed the records and discovered that Mr. SS only received 7.5 mg of fondaparinux despite the fact that Mr. SS weighed more than 100 kg (265 pounds). The Food and Drug Administration–approved dose of Arixtra for the treatment of acute venous thromboembolism is based on tertile of weight (5 mg if less than 50 kg; 7.5 mg if between 50-100 kg; and 10 mg if more than 100 kg). The complaint alleged that Mr. SS was underdosed and therefore needlessly developed a pulmonary embolism. Had Mr. SS received the FDA-approved dose of fondaparinux based on his weight, he would be alive and well today.

The complaint was filed against the ED physician, the hospitalist on call, and the house doctor.

Scientific principles

Outcome studies confirm that the vast majority of patients (more than 95%) who receive adequate anticoagulation in the setting of acute venous thromboembolism (DVT/PE) will be alive at discharge, 30 days, and at 1 year. In fact, of all the variables possibly associated with VTE recurrence, the only one demonstrated by logistic regression to be statistically significant with respect to VTE recurrence is the failure to achieve and maintain adequate anticoagulation. Properly conducted phase II dose ranging studies with Arixtra (REMBRANDT) ultimately led to the tertile weight-based dosing regimen that was studied in the phase III trial (MATISSE) that led to Arixtra’s FDA approval and the recommendations for dosing in the Arixtra package insert.

Complaint rebuttal and discussion

The defense argued that the dosing recommendations in the Arixtra package insert were guidelines and not in and of themselves the standard of care. Mr. SS did not have a normal INR on presentation and the defense argued it was reasonable clinical judgment on behalf of the providers involved to use that dose that best balanced efficacy and safety. The defense further argued that based on the timing of the PE (approximately 12 hours after the 7.5 mg fondaparinux dose), Mr. SS should have been in a therapeutic range in regard to drug concentration.

In other words, Mr. SS still would have had more drug in his body 12 hours after a 7.5-mg dose than he would at 24 hours following a 10-mg dose. As such, Mr. SS would have had a fatal PE regardless. The plaintiff attacked the clinical judgment defense as unreasonable. There simply was no reason not to use the proven and recommended dose for SS. To do anything less was unnecessary experimentation on Mr. SS by the physicians involved.

Ironically, during deposition testimony, the hospitalist on call confirmed that he never discussed the Arixtra dose with the ED physician. He further testified that had he known that the ED physician was only going to give 7.5 mg, he would have increased the dose to 10 mg himself.

Conclusion

It is commonplace for hospitalists to discuss admission plans of care with our ED colleagues. Rarely, however, do we have such discussions with the same granularity as if we were writing the actual orders ourselves. It is important to remember that if we rely on our ED colleagues (or a house doctor) to fulfill our responsibilities in that regard, we can get trapped by a clinical judgment decision that doesn’t really match what we would have done under the same circumstances. The hospitalist in this case never even saw Mr. SS and he didn’t write the Arixtra order, yet he was deemed culpable for the outcome. Based on deposition testimony, it was readily apparent that the ED physician simply did not know the appropriate Arixtra dosing schedule for a patient weighing more than 100 kg. The jury, however, was ultimately persuaded by the defense arguments and returned a full defense verdict in this case.

Dr. Michota is director of academic affairs in the hospital medicine department at the Cleveland Clinic and medical editor of Hospitalist News. He has relationships with oral anticoagulant makers Janssen, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Daiichi Sankyo.