User login

Patient, Caregiver, and Clinician Perspectives on Expectations for Home Healthcare after Discharge: A Qualitative Case Study

Patients who are discharged from the hospital with home healthcare (HHC) are older, sicker, and more likely to be readmitted to the hospital than patients discharged home without HHC.1-3 Communication between clinicians in different settings is a key factor in successful transitions. In prior work, we focused on communication between primary care providers, hospitalists, and HHC nurses to inform efforts to improve care transitions.4,5 In one study, HHC nurses described that patients frequently have expectations beyond the scope of what skilled HHC provides,5 which prompted us to also question experiences of patients and caregivers after discharge with skilled HHC (eg, nursing and physical therapy).

In a prior qualitative study by Foust and colleagues, HHC patients and caregivers described disparate experiences around preparation for hospital discharge—patients expressed knowing about the timing and plans for discharge, and the caregivers frequently felt left out of this discussion.6 In other studies, caregivers of recently discharged patients have described feeling excluded from interactions with clinicians both before and after discharge.7,8 In another recent qualitative study, caregivers described uncertainty about their role compared with the HHC role in caring for the patient.9

As of 2016, a majority of states had passed the Caregiver Advise, Record, and Enable (CARE) Act, which requires hospitals to (1) record a family caregiver in the medical record, (2) inform this caregiver about discharge, and (3) deliver instructions with education about medical tasks that they will need to complete after discharge.10

METHODS

Study Design

In this qualitative descriptive case study, we interviewed HHC patients, an involved caregiver, and the HHC clinician completing the first HHC visit within 7-14 days following hospital discharge. We chose this timeframe to allow patients to receive one or more HHC visits following hospital discharge.

Population

- >65 years old,12 eligibility was initially limited to patients

- >65 years old. Due to recruitment challenges, the age range was broadened to

- >50 years old in October 2017.

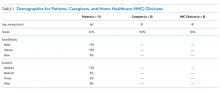

Because our goal was to better understand the experience of general medicine patients with multiple comorbidities, we recruited patients from one general medicine unit at an academic hospital in Colorado. Patients on this unit were screened for eligibility Monday-Friday (excluding weekends and holidays) based on research assistant availability.

Criteria included are as follows: HHC referral, three or more comorbidities, resides in the community prior to admission (ie, not in a facility), cognitively intact, English speaking, and able to identify a caregiver participating in their care. Eligible patients were approached for written consent prior to discharge to allow us to contact them 7-14 days after discharge for an interview by phone or in their home, per their preference. At the time of consent, patients provided contact information for their informal caregiver. Caregiver eligibility criteria included the following: age ≥18 years and provides caregiving at least one hour a week before hospital discharge. HHC clinicians approached for interviews had completed the first HHC visit for the patient following discharge. Both caregivers and HHC clinicians provided verbal consent for interviews. All participants received a $25 gift card for participation in the study.

Framework and Data Collection

Our interview guides were organized by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Care Coordination Framework, an approach we have taken in prior work.4,5,13 We added questions about patient preparation and self-management support to build on findings from a prior study with HHC nurses and on prior work by Coleman and colleagues.5,14 Sample questions from the interview guides for patients, caregivers, and HHC clinicians within key analysis domains are included in Appendix 1. The patient and caregiver interviews were completed by an individual with prior experience in social work and healthcare (SS). The HHC clinician interviews were completed by either this individual (SS) or a physician-researcher with experience in qualitative methods (CJ). Patients and caregivers could choose to be interviewed individually or together. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Patient interviews lasted an average of 43 minutes, caregiver interviews an average of 41 minutes, and HHC clinician interviews an average of 25 minutes

We observed the two main themes of clear and unclear expectations for HHC after discharge. Clear expectations occur when the patient and/or caregiver have expectations for HHC that align with the services they receive. Unclear expectations occur when the patient and/or caregiver expectations are either uncertain or misaligned with the services they receive. Although not all interviews yielded codes about clear or unclear expectations, patients described clear expectations in five cases and unclear expectations in another five cases.

In nine cases with more than one perspective available, expectations were compared within cases and found to be clear (three cases), unclear (three cases), or discordant (three cases) across perspectives. For the discordant cases, the description of clear and unclear expectations differed between patients and either their caregiver or their HHC clinician. Patients and caregivers with clear expectations for HHC frequently described prior experiences with skilled HHC or work experience within the healthcare field. In most cases with unclear expectations, the patient and caregiver did not have prior experience with HHC. In addition, the desire for assistance with personal care for patients such as showering and housekeeping was described by caregivers with unclear expectations. The results are organized into clear, unclear, and discordant expectations from the perspectives of patients, caregivers, and HHC clinicians within cases.

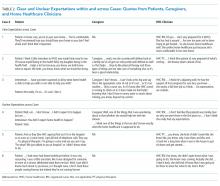

Clear Expectations within Cases

Clear expectations for HHC were identified across perspectives in three cases, with sample quotes provided in Table 2. In the case of patient 1, the patient and HHC nurse had known each other for over two years because the patient had a wound requiring long-term HHC services. A caregiver did not complete an interview in this case. With patient 2, the patient, caregiver, and HHC physical therapist (PT) all describe that the patient had clear expectations for HHC. In this case, the patient and caregiver describe feeling prepared because of previously receiving HHC, prior work experience in the healthcare field, and a caregiver with experience working in HHC. In the case of patient 3, the patient had previously received HHC from the same HHC nurse.

Unclear Expectations across Cases

For the three cases in which unclear expectations were described across perspectives, two of the patients described being new to HHC, with representative quotes in Table 2. Patient 4 and her caregiver are new to HHC and describe unclear expectations for both the HHC referral and the HHC role, which was also noted by the HHC clinician. Of note, the caregiver for patient 4 further described that she was unable to be present for the first HHC visit. In the case of patient 5, although the patient had previously received HHC, the patient describes not knowing why the HHC PT needs to see her after discharge, which is also noted by the HHC PT. Finally, both patient 6 and her HHC PT describe that the patient was not sure about their expectations for HHC and that HHC was a new experience for them.

Discordant Expectation Clarity across Cases

In three of the cases, the description of clear and unclear expectations was discrepant across roles. In case 7, the caregiver and patient are new to HHC and express different perspectives about expectations for HHC. The HHC clinician, in this case, did not complete an interview. The caregiver describes not being present for the first HHC visit and no awareness that the patient was being discharged with HHC:

Caregiver: Well, we didn’t even know she had home health until she got home.

The same caregiver also expresses unclear expectations for HHC:

Caregiver: It’s pretty cloudy. They (the HHC clinicians) don’t help her with her laundry, they don’t help with the housekeeping, they don’t help… with her showers so somebody is there when she showers. They don’t do anything. The only two things like I said is the…home healthcare comes in on Wednesdays to see what she needs and then the therapy comes in one day a week.

However, the patient expresses more clear expectations that are being met by HHC.

Patient: They (HHC) have met my expectations. They come in twice a week. They do vitals, take vitals and discuss with me, you know, what my feelings are, how I’m doing and I know they have met my expectations.

In case 8, although the patient describes knowing about the HHC PT involvement in her care, she expresses some unclear expectations about an HHC nurse after discharge.

Patient: As far as home health, I didn’t have a real …plan there at the hospital… They knew about (the HHC PT) coming once a week but as far as, you know, a nurse coming by to check on me, no.

However, the HHC PT describes feeling that the patient had clear expectations for HHC after discharge:

Interviewer: Can you reflect on whether she was prepared to receive home healthcare?

HHC PT: Yeah, she was ready.

Interviewer: …do you feel like she was prepared to know what to expect from you?

HHC PT: Yeah, but I think that comes from being a previous patient also.

Finally, in case 9, the patient describes clear expectations for HHC even though they were new to HHC:

Patient: …I knew what the PT was going to do and …I still need her because I’ve lost so much weight so she’s been really good, instrumental, at giving me exercises… Occupational therapist…she’s going to teach me how to shave, she’s going to teach me how to get ready for the day.

The HHC PT describes that although the patient knew the PT role, they reflect that the patient may have been somewhat unclear about expectations for the first HHC visit:

HHC PT: He knew all that it entailed with the exception of he didn’t really know what the first day was going to be like and the first day I don’t usually do treatment because it does take a long time to get all the paperwork signed, to do the evaluation and the fact that it takes two hours to do that note.

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative case study with HHC patients, caregivers, and clinicians, the participants described varying levels of expectation clarity for HHC after discharge. We triangulated across and within cases and found three cases with clear expectations and three cases with unclear expectations for HHC across perspectives. In three additional cases, we found discordant expectations across perspectives: patients and HHC clinician expectations differed in two of the cases and a patient and caregiver differed in one case. Of interest, in all three cases of clear expectations across perspectives, the patients and/or caregivers had prior HHC or healthcare work experience. In contrast,

Prior studies in this area have included a qualitative study HHC patients, caregivers, and clinicians by Foust and colleagues in which multiple caregivers described finding out about the discharge from the patient or other caregivers, rather than being actively engaged by clinicians.6 In another recent qualitative study by Arbaje and colleagues, a majority of caregivers described “mismatched expectations” about HHC services, in which caregivers

When caregivers have unclear expectations for HHC, they could be expressing the need for more support after hospital discharge, which suggests an active role for hospital teams to assess and address additional support needs with the patients and caregivers. For example, if the patient or caregiver request additional personal care services, a home health aide could help to reduce caregiver burden and improve the support network for the patient. In a prior study in which patients were asked what would help them to make informed decisions about postacute care options, the patients described wanting to receive practical information that could describe how it would apply to their specific situation and perceived needs.18 To provide this for patients and caregivers, it would follow that hospitals could provide information about skilled HHC nursing and therapies and information about services that could meet additional needs, such as home health aides.

Limitations of this study include that it was a small qualitative case study of patients, caregivers, and HHC clinicians from one medical unit at one academic medical center. Most patients in this study had Medicare insurance, were 65 years and older, white, and female.

In conclusion, to improve care transitions for HHC patients and their caregivers, emphasizing engagement of caregivers is key to ensure that they are educated about HHC, provided with additional support as needed, and included in initial HHC visits once the patients are at home. Even though patients and caregivers with prior HHC experience often had clear expectations for HHC, a strategy to uniformly engage caregivers across a range of experience can ensure caregivers have all the information and support needed to optimize care transitions to HHC.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Christine Jones is supported by grant number K08HS024569 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Jason Falvey was supported by grant F31AG056069 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health and is currently supported by T32AG019134. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Jones CD, Wald HL, Boxer RS, et al. Characteristics associated with home health care referrals at hospital discharge: results from the 2012 National Inpatient Sample. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(2):879-894. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773. PubMed

2. Avalere Health. Home Health Chartbook 2015: Prepared for the Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation. 2016.

3. Hospital Compare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Accessed May 1, 2017.

4. Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):417-424. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3056-x. PubMed

5. Jones CD, Jones J, Richard A, et al. “Connecting the dots”: a qualitative study of home health nurse perspectives on coordinating care for recently discharged patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(10):1114-1121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4104-0. PubMed

6. Foust JB, Vuckovic N, Henriquez E. Hospital to home health care transition: patient, caregiver, and clinician perspectives. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(2):194-212. doi: 10.1177/0193945911400448. PubMed

7. Blair J, Volpe M, Aggarwal B. Challenges, needs, and experiences of recently hospitalized cardiac patients and their informal caregivers. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29(1):29-37. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182784123. PubMed

8. Coleman EA, Roman SP. Family caregivers’ experiences during transitions out of hospital. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):12-21. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460117.83437.b3. PubMed

9. Arbaje AI, Hughes A, Werner N, et al. Information management goals and process failures during home visits for middle-aged and older adults receiving skilled home healthcare services after hospital discharge: a multisite, qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008163. PubMed

10. Coleman EA. Family caregivers as partners in care transitions: the caregiver advise record and enable act. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):883-885. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2637. PubMed

11. Jones AL, Harris-Kojetin L, Valverde R. Characteristics and use of home health care by men and women aged 65 and over. Natl Health Stat Report. 2012(52):1-7. PubMed

12. Tian W. An all-payer view of hospital discharge to postacute care, 2013. HCUP Statistical Brief #205. Rockville, Maryland; 2016. PubMed

13. McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Rockville, Maryland; 2007. PubMed

14. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Eilertsen TB, Thiare JN, Kramer AM. Development and testing of a measure designed to assess the quality of care transitions. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2:e02. doi: 10.5334/ijic.60. PubMed

15. Jones J, Nowels CT, Sudore R, Ahluwalia S, Bekelman DB. The future as a series of transitions: qualitative study of heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(2):176-182. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3085-5. PubMed

16. Lum HD, Jones J, Lahoff D, et al. Unique challenges of hospice for patients with heart failure: a qualitative study of hospice clinicians. Am Heart J. 2015;170(3):524-530 e523. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.06.019. PubMed

17. Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):269-281. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.30. PubMed

18. Sefcik JS, Nock RH, Flores EJ, et al. Patient preferences for information on post-acute care services. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2016;9(4):175-182. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20160120-01. PubMed

19. Coleman EA, Roman SP, Hall KA, Min SJ. Enhancing the care transitions intervention protocol to better address the needs of family caregivers. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):2-11. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460118.60567.fe. PubMed

Patients who are discharged from the hospital with home healthcare (HHC) are older, sicker, and more likely to be readmitted to the hospital than patients discharged home without HHC.1-3 Communication between clinicians in different settings is a key factor in successful transitions. In prior work, we focused on communication between primary care providers, hospitalists, and HHC nurses to inform efforts to improve care transitions.4,5 In one study, HHC nurses described that patients frequently have expectations beyond the scope of what skilled HHC provides,5 which prompted us to also question experiences of patients and caregivers after discharge with skilled HHC (eg, nursing and physical therapy).

In a prior qualitative study by Foust and colleagues, HHC patients and caregivers described disparate experiences around preparation for hospital discharge—patients expressed knowing about the timing and plans for discharge, and the caregivers frequently felt left out of this discussion.6 In other studies, caregivers of recently discharged patients have described feeling excluded from interactions with clinicians both before and after discharge.7,8 In another recent qualitative study, caregivers described uncertainty about their role compared with the HHC role in caring for the patient.9

As of 2016, a majority of states had passed the Caregiver Advise, Record, and Enable (CARE) Act, which requires hospitals to (1) record a family caregiver in the medical record, (2) inform this caregiver about discharge, and (3) deliver instructions with education about medical tasks that they will need to complete after discharge.10

METHODS

Study Design

In this qualitative descriptive case study, we interviewed HHC patients, an involved caregiver, and the HHC clinician completing the first HHC visit within 7-14 days following hospital discharge. We chose this timeframe to allow patients to receive one or more HHC visits following hospital discharge.

Population

- >65 years old,12 eligibility was initially limited to patients

- >65 years old. Due to recruitment challenges, the age range was broadened to

- >50 years old in October 2017.

Because our goal was to better understand the experience of general medicine patients with multiple comorbidities, we recruited patients from one general medicine unit at an academic hospital in Colorado. Patients on this unit were screened for eligibility Monday-Friday (excluding weekends and holidays) based on research assistant availability.

Criteria included are as follows: HHC referral, three or more comorbidities, resides in the community prior to admission (ie, not in a facility), cognitively intact, English speaking, and able to identify a caregiver participating in their care. Eligible patients were approached for written consent prior to discharge to allow us to contact them 7-14 days after discharge for an interview by phone or in their home, per their preference. At the time of consent, patients provided contact information for their informal caregiver. Caregiver eligibility criteria included the following: age ≥18 years and provides caregiving at least one hour a week before hospital discharge. HHC clinicians approached for interviews had completed the first HHC visit for the patient following discharge. Both caregivers and HHC clinicians provided verbal consent for interviews. All participants received a $25 gift card for participation in the study.

Framework and Data Collection

Our interview guides were organized by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Care Coordination Framework, an approach we have taken in prior work.4,5,13 We added questions about patient preparation and self-management support to build on findings from a prior study with HHC nurses and on prior work by Coleman and colleagues.5,14 Sample questions from the interview guides for patients, caregivers, and HHC clinicians within key analysis domains are included in Appendix 1. The patient and caregiver interviews were completed by an individual with prior experience in social work and healthcare (SS). The HHC clinician interviews were completed by either this individual (SS) or a physician-researcher with experience in qualitative methods (CJ). Patients and caregivers could choose to be interviewed individually or together. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Patient interviews lasted an average of 43 minutes, caregiver interviews an average of 41 minutes, and HHC clinician interviews an average of 25 minutes

We observed the two main themes of clear and unclear expectations for HHC after discharge. Clear expectations occur when the patient and/or caregiver have expectations for HHC that align with the services they receive. Unclear expectations occur when the patient and/or caregiver expectations are either uncertain or misaligned with the services they receive. Although not all interviews yielded codes about clear or unclear expectations, patients described clear expectations in five cases and unclear expectations in another five cases.

In nine cases with more than one perspective available, expectations were compared within cases and found to be clear (three cases), unclear (three cases), or discordant (three cases) across perspectives. For the discordant cases, the description of clear and unclear expectations differed between patients and either their caregiver or their HHC clinician. Patients and caregivers with clear expectations for HHC frequently described prior experiences with skilled HHC or work experience within the healthcare field. In most cases with unclear expectations, the patient and caregiver did not have prior experience with HHC. In addition, the desire for assistance with personal care for patients such as showering and housekeeping was described by caregivers with unclear expectations. The results are organized into clear, unclear, and discordant expectations from the perspectives of patients, caregivers, and HHC clinicians within cases.

Clear Expectations within Cases

Clear expectations for HHC were identified across perspectives in three cases, with sample quotes provided in Table 2. In the case of patient 1, the patient and HHC nurse had known each other for over two years because the patient had a wound requiring long-term HHC services. A caregiver did not complete an interview in this case. With patient 2, the patient, caregiver, and HHC physical therapist (PT) all describe that the patient had clear expectations for HHC. In this case, the patient and caregiver describe feeling prepared because of previously receiving HHC, prior work experience in the healthcare field, and a caregiver with experience working in HHC. In the case of patient 3, the patient had previously received HHC from the same HHC nurse.

Unclear Expectations across Cases

For the three cases in which unclear expectations were described across perspectives, two of the patients described being new to HHC, with representative quotes in Table 2. Patient 4 and her caregiver are new to HHC and describe unclear expectations for both the HHC referral and the HHC role, which was also noted by the HHC clinician. Of note, the caregiver for patient 4 further described that she was unable to be present for the first HHC visit. In the case of patient 5, although the patient had previously received HHC, the patient describes not knowing why the HHC PT needs to see her after discharge, which is also noted by the HHC PT. Finally, both patient 6 and her HHC PT describe that the patient was not sure about their expectations for HHC and that HHC was a new experience for them.

Discordant Expectation Clarity across Cases

In three of the cases, the description of clear and unclear expectations was discrepant across roles. In case 7, the caregiver and patient are new to HHC and express different perspectives about expectations for HHC. The HHC clinician, in this case, did not complete an interview. The caregiver describes not being present for the first HHC visit and no awareness that the patient was being discharged with HHC:

Caregiver: Well, we didn’t even know she had home health until she got home.

The same caregiver also expresses unclear expectations for HHC:

Caregiver: It’s pretty cloudy. They (the HHC clinicians) don’t help her with her laundry, they don’t help with the housekeeping, they don’t help… with her showers so somebody is there when she showers. They don’t do anything. The only two things like I said is the…home healthcare comes in on Wednesdays to see what she needs and then the therapy comes in one day a week.

However, the patient expresses more clear expectations that are being met by HHC.

Patient: They (HHC) have met my expectations. They come in twice a week. They do vitals, take vitals and discuss with me, you know, what my feelings are, how I’m doing and I know they have met my expectations.

In case 8, although the patient describes knowing about the HHC PT involvement in her care, she expresses some unclear expectations about an HHC nurse after discharge.

Patient: As far as home health, I didn’t have a real …plan there at the hospital… They knew about (the HHC PT) coming once a week but as far as, you know, a nurse coming by to check on me, no.

However, the HHC PT describes feeling that the patient had clear expectations for HHC after discharge:

Interviewer: Can you reflect on whether she was prepared to receive home healthcare?

HHC PT: Yeah, she was ready.

Interviewer: …do you feel like she was prepared to know what to expect from you?

HHC PT: Yeah, but I think that comes from being a previous patient also.

Finally, in case 9, the patient describes clear expectations for HHC even though they were new to HHC:

Patient: …I knew what the PT was going to do and …I still need her because I’ve lost so much weight so she’s been really good, instrumental, at giving me exercises… Occupational therapist…she’s going to teach me how to shave, she’s going to teach me how to get ready for the day.

The HHC PT describes that although the patient knew the PT role, they reflect that the patient may have been somewhat unclear about expectations for the first HHC visit:

HHC PT: He knew all that it entailed with the exception of he didn’t really know what the first day was going to be like and the first day I don’t usually do treatment because it does take a long time to get all the paperwork signed, to do the evaluation and the fact that it takes two hours to do that note.

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative case study with HHC patients, caregivers, and clinicians, the participants described varying levels of expectation clarity for HHC after discharge. We triangulated across and within cases and found three cases with clear expectations and three cases with unclear expectations for HHC across perspectives. In three additional cases, we found discordant expectations across perspectives: patients and HHC clinician expectations differed in two of the cases and a patient and caregiver differed in one case. Of interest, in all three cases of clear expectations across perspectives, the patients and/or caregivers had prior HHC or healthcare work experience. In contrast,

Prior studies in this area have included a qualitative study HHC patients, caregivers, and clinicians by Foust and colleagues in which multiple caregivers described finding out about the discharge from the patient or other caregivers, rather than being actively engaged by clinicians.6 In another recent qualitative study by Arbaje and colleagues, a majority of caregivers described “mismatched expectations” about HHC services, in which caregivers

When caregivers have unclear expectations for HHC, they could be expressing the need for more support after hospital discharge, which suggests an active role for hospital teams to assess and address additional support needs with the patients and caregivers. For example, if the patient or caregiver request additional personal care services, a home health aide could help to reduce caregiver burden and improve the support network for the patient. In a prior study in which patients were asked what would help them to make informed decisions about postacute care options, the patients described wanting to receive practical information that could describe how it would apply to their specific situation and perceived needs.18 To provide this for patients and caregivers, it would follow that hospitals could provide information about skilled HHC nursing and therapies and information about services that could meet additional needs, such as home health aides.

Limitations of this study include that it was a small qualitative case study of patients, caregivers, and HHC clinicians from one medical unit at one academic medical center. Most patients in this study had Medicare insurance, were 65 years and older, white, and female.

In conclusion, to improve care transitions for HHC patients and their caregivers, emphasizing engagement of caregivers is key to ensure that they are educated about HHC, provided with additional support as needed, and included in initial HHC visits once the patients are at home. Even though patients and caregivers with prior HHC experience often had clear expectations for HHC, a strategy to uniformly engage caregivers across a range of experience can ensure caregivers have all the information and support needed to optimize care transitions to HHC.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Christine Jones is supported by grant number K08HS024569 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Jason Falvey was supported by grant F31AG056069 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health and is currently supported by T32AG019134. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the National Institutes of Health.

Patients who are discharged from the hospital with home healthcare (HHC) are older, sicker, and more likely to be readmitted to the hospital than patients discharged home without HHC.1-3 Communication between clinicians in different settings is a key factor in successful transitions. In prior work, we focused on communication between primary care providers, hospitalists, and HHC nurses to inform efforts to improve care transitions.4,5 In one study, HHC nurses described that patients frequently have expectations beyond the scope of what skilled HHC provides,5 which prompted us to also question experiences of patients and caregivers after discharge with skilled HHC (eg, nursing and physical therapy).

In a prior qualitative study by Foust and colleagues, HHC patients and caregivers described disparate experiences around preparation for hospital discharge—patients expressed knowing about the timing and plans for discharge, and the caregivers frequently felt left out of this discussion.6 In other studies, caregivers of recently discharged patients have described feeling excluded from interactions with clinicians both before and after discharge.7,8 In another recent qualitative study, caregivers described uncertainty about their role compared with the HHC role in caring for the patient.9

As of 2016, a majority of states had passed the Caregiver Advise, Record, and Enable (CARE) Act, which requires hospitals to (1) record a family caregiver in the medical record, (2) inform this caregiver about discharge, and (3) deliver instructions with education about medical tasks that they will need to complete after discharge.10

METHODS

Study Design

In this qualitative descriptive case study, we interviewed HHC patients, an involved caregiver, and the HHC clinician completing the first HHC visit within 7-14 days following hospital discharge. We chose this timeframe to allow patients to receive one or more HHC visits following hospital discharge.

Population

- >65 years old,12 eligibility was initially limited to patients

- >65 years old. Due to recruitment challenges, the age range was broadened to

- >50 years old in October 2017.

Because our goal was to better understand the experience of general medicine patients with multiple comorbidities, we recruited patients from one general medicine unit at an academic hospital in Colorado. Patients on this unit were screened for eligibility Monday-Friday (excluding weekends and holidays) based on research assistant availability.

Criteria included are as follows: HHC referral, three or more comorbidities, resides in the community prior to admission (ie, not in a facility), cognitively intact, English speaking, and able to identify a caregiver participating in their care. Eligible patients were approached for written consent prior to discharge to allow us to contact them 7-14 days after discharge for an interview by phone or in their home, per their preference. At the time of consent, patients provided contact information for their informal caregiver. Caregiver eligibility criteria included the following: age ≥18 years and provides caregiving at least one hour a week before hospital discharge. HHC clinicians approached for interviews had completed the first HHC visit for the patient following discharge. Both caregivers and HHC clinicians provided verbal consent for interviews. All participants received a $25 gift card for participation in the study.

Framework and Data Collection

Our interview guides were organized by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Care Coordination Framework, an approach we have taken in prior work.4,5,13 We added questions about patient preparation and self-management support to build on findings from a prior study with HHC nurses and on prior work by Coleman and colleagues.5,14 Sample questions from the interview guides for patients, caregivers, and HHC clinicians within key analysis domains are included in Appendix 1. The patient and caregiver interviews were completed by an individual with prior experience in social work and healthcare (SS). The HHC clinician interviews were completed by either this individual (SS) or a physician-researcher with experience in qualitative methods (CJ). Patients and caregivers could choose to be interviewed individually or together. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Patient interviews lasted an average of 43 minutes, caregiver interviews an average of 41 minutes, and HHC clinician interviews an average of 25 minutes

We observed the two main themes of clear and unclear expectations for HHC after discharge. Clear expectations occur when the patient and/or caregiver have expectations for HHC that align with the services they receive. Unclear expectations occur when the patient and/or caregiver expectations are either uncertain or misaligned with the services they receive. Although not all interviews yielded codes about clear or unclear expectations, patients described clear expectations in five cases and unclear expectations in another five cases.

In nine cases with more than one perspective available, expectations were compared within cases and found to be clear (three cases), unclear (three cases), or discordant (three cases) across perspectives. For the discordant cases, the description of clear and unclear expectations differed between patients and either their caregiver or their HHC clinician. Patients and caregivers with clear expectations for HHC frequently described prior experiences with skilled HHC or work experience within the healthcare field. In most cases with unclear expectations, the patient and caregiver did not have prior experience with HHC. In addition, the desire for assistance with personal care for patients such as showering and housekeeping was described by caregivers with unclear expectations. The results are organized into clear, unclear, and discordant expectations from the perspectives of patients, caregivers, and HHC clinicians within cases.

Clear Expectations within Cases

Clear expectations for HHC were identified across perspectives in three cases, with sample quotes provided in Table 2. In the case of patient 1, the patient and HHC nurse had known each other for over two years because the patient had a wound requiring long-term HHC services. A caregiver did not complete an interview in this case. With patient 2, the patient, caregiver, and HHC physical therapist (PT) all describe that the patient had clear expectations for HHC. In this case, the patient and caregiver describe feeling prepared because of previously receiving HHC, prior work experience in the healthcare field, and a caregiver with experience working in HHC. In the case of patient 3, the patient had previously received HHC from the same HHC nurse.

Unclear Expectations across Cases

For the three cases in which unclear expectations were described across perspectives, two of the patients described being new to HHC, with representative quotes in Table 2. Patient 4 and her caregiver are new to HHC and describe unclear expectations for both the HHC referral and the HHC role, which was also noted by the HHC clinician. Of note, the caregiver for patient 4 further described that she was unable to be present for the first HHC visit. In the case of patient 5, although the patient had previously received HHC, the patient describes not knowing why the HHC PT needs to see her after discharge, which is also noted by the HHC PT. Finally, both patient 6 and her HHC PT describe that the patient was not sure about their expectations for HHC and that HHC was a new experience for them.

Discordant Expectation Clarity across Cases

In three of the cases, the description of clear and unclear expectations was discrepant across roles. In case 7, the caregiver and patient are new to HHC and express different perspectives about expectations for HHC. The HHC clinician, in this case, did not complete an interview. The caregiver describes not being present for the first HHC visit and no awareness that the patient was being discharged with HHC:

Caregiver: Well, we didn’t even know she had home health until she got home.

The same caregiver also expresses unclear expectations for HHC:

Caregiver: It’s pretty cloudy. They (the HHC clinicians) don’t help her with her laundry, they don’t help with the housekeeping, they don’t help… with her showers so somebody is there when she showers. They don’t do anything. The only two things like I said is the…home healthcare comes in on Wednesdays to see what she needs and then the therapy comes in one day a week.

However, the patient expresses more clear expectations that are being met by HHC.

Patient: They (HHC) have met my expectations. They come in twice a week. They do vitals, take vitals and discuss with me, you know, what my feelings are, how I’m doing and I know they have met my expectations.

In case 8, although the patient describes knowing about the HHC PT involvement in her care, she expresses some unclear expectations about an HHC nurse after discharge.

Patient: As far as home health, I didn’t have a real …plan there at the hospital… They knew about (the HHC PT) coming once a week but as far as, you know, a nurse coming by to check on me, no.

However, the HHC PT describes feeling that the patient had clear expectations for HHC after discharge:

Interviewer: Can you reflect on whether she was prepared to receive home healthcare?

HHC PT: Yeah, she was ready.

Interviewer: …do you feel like she was prepared to know what to expect from you?

HHC PT: Yeah, but I think that comes from being a previous patient also.

Finally, in case 9, the patient describes clear expectations for HHC even though they were new to HHC:

Patient: …I knew what the PT was going to do and …I still need her because I’ve lost so much weight so she’s been really good, instrumental, at giving me exercises… Occupational therapist…she’s going to teach me how to shave, she’s going to teach me how to get ready for the day.

The HHC PT describes that although the patient knew the PT role, they reflect that the patient may have been somewhat unclear about expectations for the first HHC visit:

HHC PT: He knew all that it entailed with the exception of he didn’t really know what the first day was going to be like and the first day I don’t usually do treatment because it does take a long time to get all the paperwork signed, to do the evaluation and the fact that it takes two hours to do that note.

DISCUSSION

In this qualitative case study with HHC patients, caregivers, and clinicians, the participants described varying levels of expectation clarity for HHC after discharge. We triangulated across and within cases and found three cases with clear expectations and three cases with unclear expectations for HHC across perspectives. In three additional cases, we found discordant expectations across perspectives: patients and HHC clinician expectations differed in two of the cases and a patient and caregiver differed in one case. Of interest, in all three cases of clear expectations across perspectives, the patients and/or caregivers had prior HHC or healthcare work experience. In contrast,

Prior studies in this area have included a qualitative study HHC patients, caregivers, and clinicians by Foust and colleagues in which multiple caregivers described finding out about the discharge from the patient or other caregivers, rather than being actively engaged by clinicians.6 In another recent qualitative study by Arbaje and colleagues, a majority of caregivers described “mismatched expectations” about HHC services, in which caregivers

When caregivers have unclear expectations for HHC, they could be expressing the need for more support after hospital discharge, which suggests an active role for hospital teams to assess and address additional support needs with the patients and caregivers. For example, if the patient or caregiver request additional personal care services, a home health aide could help to reduce caregiver burden and improve the support network for the patient. In a prior study in which patients were asked what would help them to make informed decisions about postacute care options, the patients described wanting to receive practical information that could describe how it would apply to their specific situation and perceived needs.18 To provide this for patients and caregivers, it would follow that hospitals could provide information about skilled HHC nursing and therapies and information about services that could meet additional needs, such as home health aides.

Limitations of this study include that it was a small qualitative case study of patients, caregivers, and HHC clinicians from one medical unit at one academic medical center. Most patients in this study had Medicare insurance, were 65 years and older, white, and female.

In conclusion, to improve care transitions for HHC patients and their caregivers, emphasizing engagement of caregivers is key to ensure that they are educated about HHC, provided with additional support as needed, and included in initial HHC visits once the patients are at home. Even though patients and caregivers with prior HHC experience often had clear expectations for HHC, a strategy to uniformly engage caregivers across a range of experience can ensure caregivers have all the information and support needed to optimize care transitions to HHC.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Christine Jones is supported by grant number K08HS024569 from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Jason Falvey was supported by grant F31AG056069 from the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health and is currently supported by T32AG019134. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Jones CD, Wald HL, Boxer RS, et al. Characteristics associated with home health care referrals at hospital discharge: results from the 2012 National Inpatient Sample. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(2):879-894. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773. PubMed

2. Avalere Health. Home Health Chartbook 2015: Prepared for the Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation. 2016.

3. Hospital Compare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Accessed May 1, 2017.

4. Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):417-424. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3056-x. PubMed

5. Jones CD, Jones J, Richard A, et al. “Connecting the dots”: a qualitative study of home health nurse perspectives on coordinating care for recently discharged patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(10):1114-1121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4104-0. PubMed

6. Foust JB, Vuckovic N, Henriquez E. Hospital to home health care transition: patient, caregiver, and clinician perspectives. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(2):194-212. doi: 10.1177/0193945911400448. PubMed

7. Blair J, Volpe M, Aggarwal B. Challenges, needs, and experiences of recently hospitalized cardiac patients and their informal caregivers. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29(1):29-37. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182784123. PubMed

8. Coleman EA, Roman SP. Family caregivers’ experiences during transitions out of hospital. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):12-21. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460117.83437.b3. PubMed

9. Arbaje AI, Hughes A, Werner N, et al. Information management goals and process failures during home visits for middle-aged and older adults receiving skilled home healthcare services after hospital discharge: a multisite, qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008163. PubMed

10. Coleman EA. Family caregivers as partners in care transitions: the caregiver advise record and enable act. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):883-885. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2637. PubMed

11. Jones AL, Harris-Kojetin L, Valverde R. Characteristics and use of home health care by men and women aged 65 and over. Natl Health Stat Report. 2012(52):1-7. PubMed

12. Tian W. An all-payer view of hospital discharge to postacute care, 2013. HCUP Statistical Brief #205. Rockville, Maryland; 2016. PubMed

13. McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Rockville, Maryland; 2007. PubMed

14. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Eilertsen TB, Thiare JN, Kramer AM. Development and testing of a measure designed to assess the quality of care transitions. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2:e02. doi: 10.5334/ijic.60. PubMed

15. Jones J, Nowels CT, Sudore R, Ahluwalia S, Bekelman DB. The future as a series of transitions: qualitative study of heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(2):176-182. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3085-5. PubMed

16. Lum HD, Jones J, Lahoff D, et al. Unique challenges of hospice for patients with heart failure: a qualitative study of hospice clinicians. Am Heart J. 2015;170(3):524-530 e523. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.06.019. PubMed

17. Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):269-281. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.30. PubMed

18. Sefcik JS, Nock RH, Flores EJ, et al. Patient preferences for information on post-acute care services. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2016;9(4):175-182. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20160120-01. PubMed

19. Coleman EA, Roman SP, Hall KA, Min SJ. Enhancing the care transitions intervention protocol to better address the needs of family caregivers. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):2-11. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460118.60567.fe. PubMed

1. Jones CD, Wald HL, Boxer RS, et al. Characteristics associated with home health care referrals at hospital discharge: results from the 2012 National Inpatient Sample. Health Serv Res. 2017;52(2):879-894. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773. PubMed

2. Avalere Health. Home Health Chartbook 2015: Prepared for the Alliance for Home Health Quality and Innovation. 2016.

3. Hospital Compare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Accessed May 1, 2017.

4. Jones CD, Vu MB, O’Donnell CM, et al. A failure to communicate: a qualitative exploration of care coordination between hospitalists and primary care providers around patient hospitalizations. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(4):417-424. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3056-x. PubMed

5. Jones CD, Jones J, Richard A, et al. “Connecting the dots”: a qualitative study of home health nurse perspectives on coordinating care for recently discharged patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(10):1114-1121. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4104-0. PubMed

6. Foust JB, Vuckovic N, Henriquez E. Hospital to home health care transition: patient, caregiver, and clinician perspectives. West J Nurs Res. 2012;34(2):194-212. doi: 10.1177/0193945911400448. PubMed

7. Blair J, Volpe M, Aggarwal B. Challenges, needs, and experiences of recently hospitalized cardiac patients and their informal caregivers. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2014;29(1):29-37. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3182784123. PubMed

8. Coleman EA, Roman SP. Family caregivers’ experiences during transitions out of hospital. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):12-21. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460117.83437.b3. PubMed

9. Arbaje AI, Hughes A, Werner N, et al. Information management goals and process failures during home visits for middle-aged and older adults receiving skilled home healthcare services after hospital discharge: a multisite, qualitative study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2018-008163. PubMed

10. Coleman EA. Family caregivers as partners in care transitions: the caregiver advise record and enable act. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(12):883-885. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2637. PubMed

11. Jones AL, Harris-Kojetin L, Valverde R. Characteristics and use of home health care by men and women aged 65 and over. Natl Health Stat Report. 2012(52):1-7. PubMed

12. Tian W. An all-payer view of hospital discharge to postacute care, 2013. HCUP Statistical Brief #205. Rockville, Maryland; 2016. PubMed

13. McDonald KM, Sundaram V, Bravata DM, et al. Closing the Quality Gap: A Critical Analysis of Quality Improvement Strategies (Vol. 7: Care Coordination). Rockville, Maryland; 2007. PubMed

14. Coleman EA, Smith JD, Frank JC, Eilertsen TB, Thiare JN, Kramer AM. Development and testing of a measure designed to assess the quality of care transitions. Int J Integr Care. 2002;2:e02. doi: 10.5334/ijic.60. PubMed

15. Jones J, Nowels CT, Sudore R, Ahluwalia S, Bekelman DB. The future as a series of transitions: qualitative study of heart failure patients and their informal caregivers. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(2):176-182. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3085-5. PubMed

16. Lum HD, Jones J, Lahoff D, et al. Unique challenges of hospice for patients with heart failure: a qualitative study of hospice clinicians. Am Heart J. 2015;170(3):524-530 e523. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.06.019. PubMed

17. Kerr C, Nixon A, Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10(3):269-281. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.30. PubMed

18. Sefcik JS, Nock RH, Flores EJ, et al. Patient preferences for information on post-acute care services. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2016;9(4):175-182. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20160120-01. PubMed

19. Coleman EA, Roman SP, Hall KA, Min SJ. Enhancing the care transitions intervention protocol to better address the needs of family caregivers. J Healthc Qual. 2015;37(1):2-11. doi: 10.1097/01.JHQ.0000460118.60567.fe. PubMed

© 2019 Society of Hospital Medicine