User login

Emergency Imaging: What is the suspected diagnosis? Is additional imaging necessary, and if so, why?

A 25-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented with low-back pain that radiated down into his right thigh. The patient stated the pain began 1 week earlier when he was lifting weights and had increased in severity to the point where he was no longer able to walk or stand up straight. He had taken nonprescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but received no significant relief.

Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were obtained; representative anteroposterior (AP) and lateral images are shown above (Figures 1 and 2).

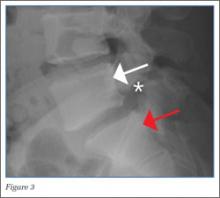

The lateral view of the lumbar spine demonstrates mild anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 with the posterior cortex of L5 (white arrow, Figure 3) anterior to the posterior cortex of S1 (red arrow, Figure 3). Normally, the posterior cortices of the adjacent vertebral bodies should align. Lucency is also noted in the region of the pars interarticularis (white asterisk, Figure 3). The combination of anterolisthesis and this lucency in a young patient suggests the diagnosis of spondylolysis (pars defect).

The pathophysiology of spondylolysis is still uncertain. Two theories have been proposed—underlying dysplastic pars interarticularis versus repetitive microtrauma resulting in stress factors are the two proposed underlying mechanism. If patients are genetically predisposed, underlying dysplasia probably contributes to the pathology, while microtrauma triggers the actual defect.2 Most patients respond well with conservative management.

When evaluating for spondylolysis, AP, lateral, 45-degree right and left oblique views, and collimated lateral views of the lumbosacral spine should be obtained. With this five-view study, up to 96.5% of pars defect can be identified.

In the general population, if spondylolysis is suspected and radiographs are negative, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and/or single-photon emission computed tomography bone scintigraphy can be used for further evaluation.4,5 In this case, the diagnosis was made based on radiographic imaging, and the patient was discharged with a scheduled follow-up with an orthopedic surgeon.

Dr Salama is a resident of radiology, resident of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Belfi is an assistant professor of radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College New York; and an assistant attending radiologist, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Belfi LM, Ortiz AO, Katz DS. Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(24):E907-E910. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000245947.31473.0a.

- Foreman P, Griessenauer CJ, Watanabe K, et al. L5 spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis: a comprehensive review with an anatomic focus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(2):209-216. doi:10.1007/s00381-012-1942-2.

- Amato M, Totty WG, Gilula LA. Spondylolysis of the lumbar spine: demonstration of defects and laminal fragmentation. Radiology. 1984;153(3):627-629.

- Saraste H, Nilsson B, Broström LA, et al. Relationship between radiological and clinical variables in spondylolysis. Int Orthop. 1984;8(3):163-174. doi:10.1007/BF00269912.

- Lee JH, Ehara S, Tamakawa Y, Shimamura T. Spondylolysis of the upper lumbar spine: Radiological features. Clin Imaging. 1999;23(6):389-393. doi:10.1016/S0899-7071(99)00158-8.

A 25-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented with low-back pain that radiated down into his right thigh. The patient stated the pain began 1 week earlier when he was lifting weights and had increased in severity to the point where he was no longer able to walk or stand up straight. He had taken nonprescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but received no significant relief.

Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were obtained; representative anteroposterior (AP) and lateral images are shown above (Figures 1 and 2).

The lateral view of the lumbar spine demonstrates mild anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 with the posterior cortex of L5 (white arrow, Figure 3) anterior to the posterior cortex of S1 (red arrow, Figure 3). Normally, the posterior cortices of the adjacent vertebral bodies should align. Lucency is also noted in the region of the pars interarticularis (white asterisk, Figure 3). The combination of anterolisthesis and this lucency in a young patient suggests the diagnosis of spondylolysis (pars defect).

The pathophysiology of spondylolysis is still uncertain. Two theories have been proposed—underlying dysplastic pars interarticularis versus repetitive microtrauma resulting in stress factors are the two proposed underlying mechanism. If patients are genetically predisposed, underlying dysplasia probably contributes to the pathology, while microtrauma triggers the actual defect.2 Most patients respond well with conservative management.

When evaluating for spondylolysis, AP, lateral, 45-degree right and left oblique views, and collimated lateral views of the lumbosacral spine should be obtained. With this five-view study, up to 96.5% of pars defect can be identified.

In the general population, if spondylolysis is suspected and radiographs are negative, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and/or single-photon emission computed tomography bone scintigraphy can be used for further evaluation.4,5 In this case, the diagnosis was made based on radiographic imaging, and the patient was discharged with a scheduled follow-up with an orthopedic surgeon.

Dr Salama is a resident of radiology, resident of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Belfi is an assistant professor of radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College New York; and an assistant attending radiologist, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

A 25-year-old man with no significant past medical history presented with low-back pain that radiated down into his right thigh. The patient stated the pain began 1 week earlier when he was lifting weights and had increased in severity to the point where he was no longer able to walk or stand up straight. He had taken nonprescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs but received no significant relief.

Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were obtained; representative anteroposterior (AP) and lateral images are shown above (Figures 1 and 2).

The lateral view of the lumbar spine demonstrates mild anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 with the posterior cortex of L5 (white arrow, Figure 3) anterior to the posterior cortex of S1 (red arrow, Figure 3). Normally, the posterior cortices of the adjacent vertebral bodies should align. Lucency is also noted in the region of the pars interarticularis (white asterisk, Figure 3). The combination of anterolisthesis and this lucency in a young patient suggests the diagnosis of spondylolysis (pars defect).

The pathophysiology of spondylolysis is still uncertain. Two theories have been proposed—underlying dysplastic pars interarticularis versus repetitive microtrauma resulting in stress factors are the two proposed underlying mechanism. If patients are genetically predisposed, underlying dysplasia probably contributes to the pathology, while microtrauma triggers the actual defect.2 Most patients respond well with conservative management.

When evaluating for spondylolysis, AP, lateral, 45-degree right and left oblique views, and collimated lateral views of the lumbosacral spine should be obtained. With this five-view study, up to 96.5% of pars defect can be identified.

In the general population, if spondylolysis is suspected and radiographs are negative, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography, and/or single-photon emission computed tomography bone scintigraphy can be used for further evaluation.4,5 In this case, the diagnosis was made based on radiographic imaging, and the patient was discharged with a scheduled follow-up with an orthopedic surgeon.

Dr Salama is a resident of radiology, resident of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Belfi is an assistant professor of radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College New York; and an assistant attending radiologist, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center, New York. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology, New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. He is associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Belfi LM, Ortiz AO, Katz DS. Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(24):E907-E910. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000245947.31473.0a.

- Foreman P, Griessenauer CJ, Watanabe K, et al. L5 spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis: a comprehensive review with an anatomic focus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(2):209-216. doi:10.1007/s00381-012-1942-2.

- Amato M, Totty WG, Gilula LA. Spondylolysis of the lumbar spine: demonstration of defects and laminal fragmentation. Radiology. 1984;153(3):627-629.

- Saraste H, Nilsson B, Broström LA, et al. Relationship between radiological and clinical variables in spondylolysis. Int Orthop. 1984;8(3):163-174. doi:10.1007/BF00269912.

- Lee JH, Ehara S, Tamakawa Y, Shimamura T. Spondylolysis of the upper lumbar spine: Radiological features. Clin Imaging. 1999;23(6):389-393. doi:10.1016/S0899-7071(99)00158-8.

- Belfi LM, Ortiz AO, Katz DS. Computed tomography evaluation of spondylolysis and spondylolisthesis in asymptomatic patients. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2006;31(24):E907-E910. doi:10.1097/01.brs.0000245947.31473.0a.

- Foreman P, Griessenauer CJ, Watanabe K, et al. L5 spondylolysis/spondylolisthesis: a comprehensive review with an anatomic focus. Childs Nerv Syst. 2013;29(2):209-216. doi:10.1007/s00381-012-1942-2.

- Amato M, Totty WG, Gilula LA. Spondylolysis of the lumbar spine: demonstration of defects and laminal fragmentation. Radiology. 1984;153(3):627-629.

- Saraste H, Nilsson B, Broström LA, et al. Relationship between radiological and clinical variables in spondylolysis. Int Orthop. 1984;8(3):163-174. doi:10.1007/BF00269912.

- Lee JH, Ehara S, Tamakawa Y, Shimamura T. Spondylolysis of the upper lumbar spine: Radiological features. Clin Imaging. 1999;23(6):389-393. doi:10.1016/S0899-7071(99)00158-8.