User login

Emotional blunting in patients taking antidepressants

When used to treat anxiety or depressive disorders, antidepressants can cause a variety of adverse effects, including emotional blunting. Emotional blunting has been described as emotional numbness, indifference, decreased responsiveness, or numbing. In a study of 669 patients who had been receiving antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], or other antidepressants), 46% said they had experienced emotional blunting.1 A 2019 study found that approximately one-third of patients with unipolar depression or bipolar depression stopped taking their antidepressant due to emotional blunting.2

Historically, there has been difficulty parsing out emotional blunting (a general decrease of all range of emotions) from anhedonia (a restriction of positive emotions). Additionally, some researchers have questioned if the blunting of emotions is part of depressive symptomatology. In a study of 38 adults, most felt able to differentiate emotional blunting due to antidepressants by considering the resolution of other depressive symptoms and timeline of onset.3

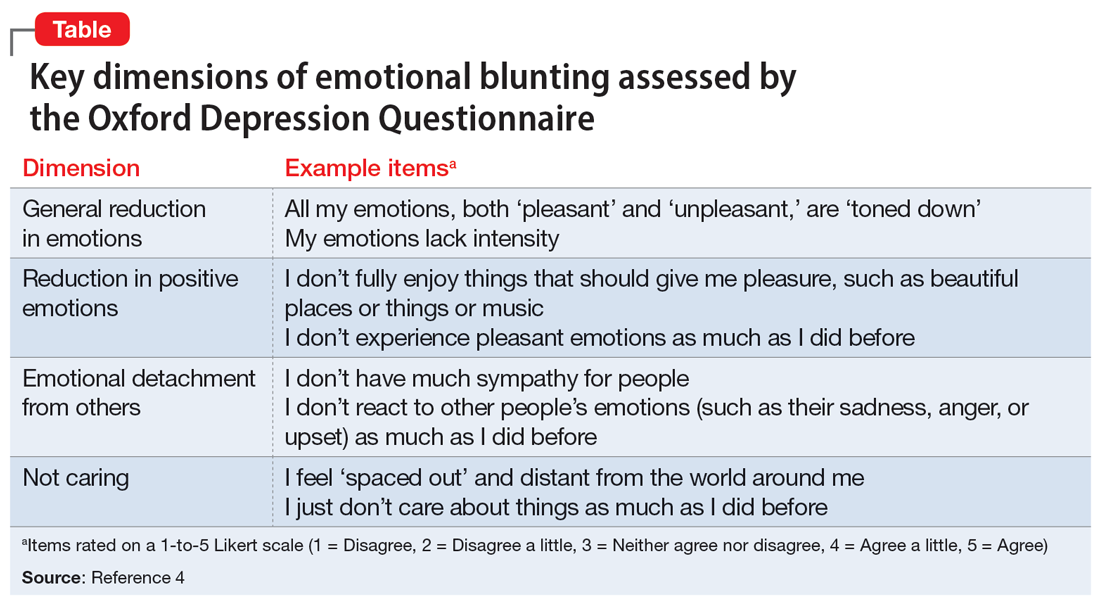

A significant limitation has been how clinicians measure or assess emotional blunting. The Oxford Depression Questionnaire (ODQ), previously known as the Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants, was created based on a qualitative survey of patients who endorsed emotional blunting.4 A validated scale, the ODQ divides emotional blunting into 4 dimensions:

- general reduction in emotions

- reduction in positive emotions

- emotional detachment from others

- not caring.4

The sections of ODQ focus on exploring specific aspects of patients’ emotional experiences, comparing experiences in the past week to before the development of illness/emotional blunting, and patients’ opinions about antidepressants. Example statements from the ODQ (Table4) may help clinicians better understand and explore emotional blunting with their patients.

There are 2 leading theories behind the mechanism of emotional blunting on antidepressants, both focused on serotonin. The first theory offers that SSRIs alter frontal lobe activity through serotonergic effects. The second theory is focused on the downward effects of serotonin on dopamine in reward pathways.5

Treatment options: Limited evidence

Data on how to address antidepressant-induced emotional blunting are limited and based largely on case reports. One open-label study (N = 143) found that patients experiencing emotional blunting while taking SSRIs and SNRIs who were switched to vortioxetine had a statistically significant decrease in ODQ total score; 50% reported no emotional blunting.6 Options to address emotional blunting include decreasing the antidepressant dose, augmenting with or switching to another agent, or considering other treatments such as neuromodulation.5 Further research is necessary to clarify which intervention is best.

Clinicians will encounter emotional blunting in patients who are taking antidepressants. It is important to recognize and address these symptoms to help improve patients’ adherence and overall quality of life.

1. Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, et al. Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: a survey among depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:31-35.

2. Rosenblat JD, Simon GE, Sachs GS, et al. Treatment effectiveness and tolerability outcomes that are most important to individuals with bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:116-120.

3. Price J, Cole V, Goodwin GM. Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):211-217.

4. Price J, Cole V, Doll H, et al. The Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants (OQuESA): development, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(1):66-74.

5. Ma H, Cai M, Wang H. Emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder: a brief non-systematic review of current research. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:792960. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.792960

6. Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, et al. Effectiveness of vortioxetine on emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:472-479.

When used to treat anxiety or depressive disorders, antidepressants can cause a variety of adverse effects, including emotional blunting. Emotional blunting has been described as emotional numbness, indifference, decreased responsiveness, or numbing. In a study of 669 patients who had been receiving antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], or other antidepressants), 46% said they had experienced emotional blunting.1 A 2019 study found that approximately one-third of patients with unipolar depression or bipolar depression stopped taking their antidepressant due to emotional blunting.2

Historically, there has been difficulty parsing out emotional blunting (a general decrease of all range of emotions) from anhedonia (a restriction of positive emotions). Additionally, some researchers have questioned if the blunting of emotions is part of depressive symptomatology. In a study of 38 adults, most felt able to differentiate emotional blunting due to antidepressants by considering the resolution of other depressive symptoms and timeline of onset.3

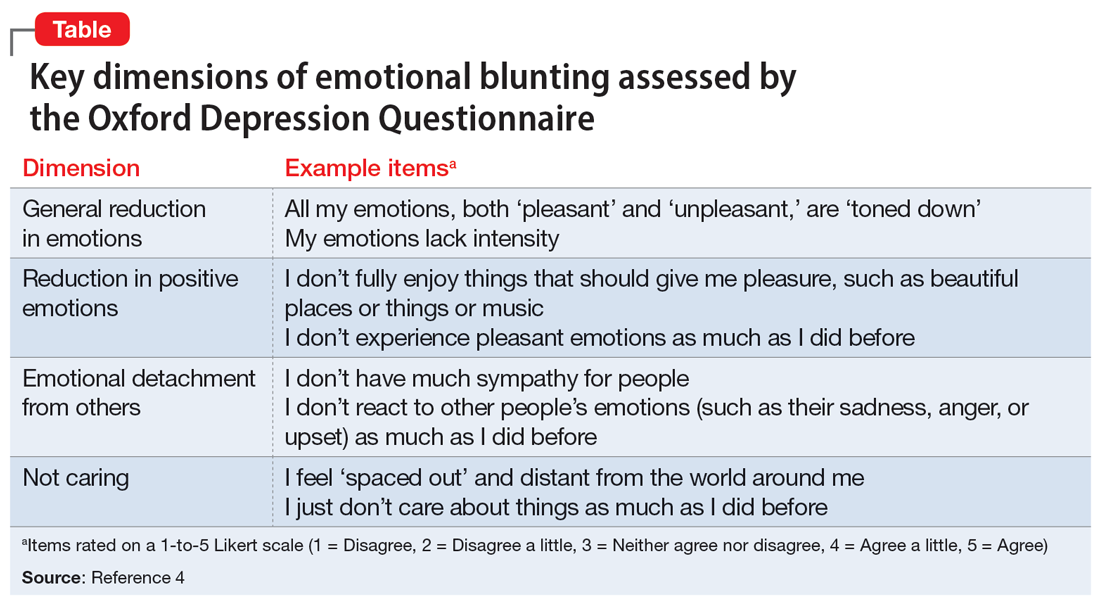

A significant limitation has been how clinicians measure or assess emotional blunting. The Oxford Depression Questionnaire (ODQ), previously known as the Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants, was created based on a qualitative survey of patients who endorsed emotional blunting.4 A validated scale, the ODQ divides emotional blunting into 4 dimensions:

- general reduction in emotions

- reduction in positive emotions

- emotional detachment from others

- not caring.4

The sections of ODQ focus on exploring specific aspects of patients’ emotional experiences, comparing experiences in the past week to before the development of illness/emotional blunting, and patients’ opinions about antidepressants. Example statements from the ODQ (Table4) may help clinicians better understand and explore emotional blunting with their patients.

There are 2 leading theories behind the mechanism of emotional blunting on antidepressants, both focused on serotonin. The first theory offers that SSRIs alter frontal lobe activity through serotonergic effects. The second theory is focused on the downward effects of serotonin on dopamine in reward pathways.5

Treatment options: Limited evidence

Data on how to address antidepressant-induced emotional blunting are limited and based largely on case reports. One open-label study (N = 143) found that patients experiencing emotional blunting while taking SSRIs and SNRIs who were switched to vortioxetine had a statistically significant decrease in ODQ total score; 50% reported no emotional blunting.6 Options to address emotional blunting include decreasing the antidepressant dose, augmenting with or switching to another agent, or considering other treatments such as neuromodulation.5 Further research is necessary to clarify which intervention is best.

Clinicians will encounter emotional blunting in patients who are taking antidepressants. It is important to recognize and address these symptoms to help improve patients’ adherence and overall quality of life.

When used to treat anxiety or depressive disorders, antidepressants can cause a variety of adverse effects, including emotional blunting. Emotional blunting has been described as emotional numbness, indifference, decreased responsiveness, or numbing. In a study of 669 patients who had been receiving antidepressants (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs], serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors [SNRIs], or other antidepressants), 46% said they had experienced emotional blunting.1 A 2019 study found that approximately one-third of patients with unipolar depression or bipolar depression stopped taking their antidepressant due to emotional blunting.2

Historically, there has been difficulty parsing out emotional blunting (a general decrease of all range of emotions) from anhedonia (a restriction of positive emotions). Additionally, some researchers have questioned if the blunting of emotions is part of depressive symptomatology. In a study of 38 adults, most felt able to differentiate emotional blunting due to antidepressants by considering the resolution of other depressive symptoms and timeline of onset.3

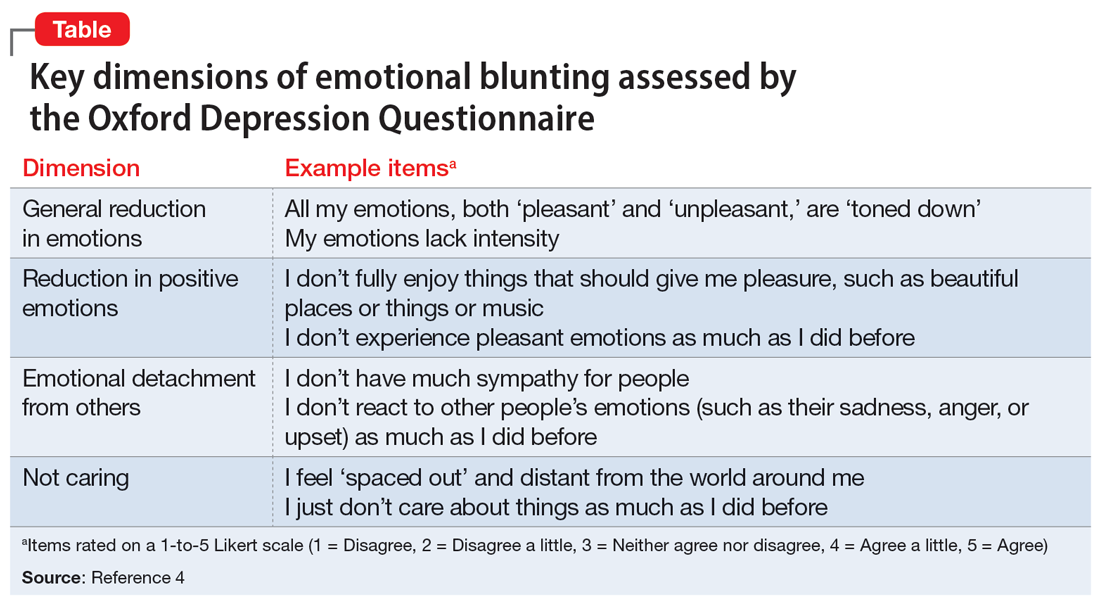

A significant limitation has been how clinicians measure or assess emotional blunting. The Oxford Depression Questionnaire (ODQ), previously known as the Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants, was created based on a qualitative survey of patients who endorsed emotional blunting.4 A validated scale, the ODQ divides emotional blunting into 4 dimensions:

- general reduction in emotions

- reduction in positive emotions

- emotional detachment from others

- not caring.4

The sections of ODQ focus on exploring specific aspects of patients’ emotional experiences, comparing experiences in the past week to before the development of illness/emotional blunting, and patients’ opinions about antidepressants. Example statements from the ODQ (Table4) may help clinicians better understand and explore emotional blunting with their patients.

There are 2 leading theories behind the mechanism of emotional blunting on antidepressants, both focused on serotonin. The first theory offers that SSRIs alter frontal lobe activity through serotonergic effects. The second theory is focused on the downward effects of serotonin on dopamine in reward pathways.5

Treatment options: Limited evidence

Data on how to address antidepressant-induced emotional blunting are limited and based largely on case reports. One open-label study (N = 143) found that patients experiencing emotional blunting while taking SSRIs and SNRIs who were switched to vortioxetine had a statistically significant decrease in ODQ total score; 50% reported no emotional blunting.6 Options to address emotional blunting include decreasing the antidepressant dose, augmenting with or switching to another agent, or considering other treatments such as neuromodulation.5 Further research is necessary to clarify which intervention is best.

Clinicians will encounter emotional blunting in patients who are taking antidepressants. It is important to recognize and address these symptoms to help improve patients’ adherence and overall quality of life.

1. Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, et al. Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: a survey among depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:31-35.

2. Rosenblat JD, Simon GE, Sachs GS, et al. Treatment effectiveness and tolerability outcomes that are most important to individuals with bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:116-120.

3. Price J, Cole V, Goodwin GM. Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):211-217.

4. Price J, Cole V, Doll H, et al. The Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants (OQuESA): development, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(1):66-74.

5. Ma H, Cai M, Wang H. Emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder: a brief non-systematic review of current research. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:792960. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.792960

6. Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, et al. Effectiveness of vortioxetine on emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:472-479.

1. Goodwin GM, Price J, De Bodinat C, et al. Emotional blunting with antidepressant treatments: a survey among depressed patients. J Affect Disord. 2017;221:31-35.

2. Rosenblat JD, Simon GE, Sachs GS, et al. Treatment effectiveness and tolerability outcomes that are most important to individuals with bipolar and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2019;243:116-120.

3. Price J, Cole V, Goodwin GM. Emotional side-effects of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: qualitative study. Br J Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):211-217.

4. Price J, Cole V, Doll H, et al. The Oxford Questionnaire on the Emotional Side-effects of Antidepressants (OQuESA): development, validity, reliability and sensitivity to change. J Affect Disord. 2012;140(1):66-74.

5. Ma H, Cai M, Wang H. Emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder: a brief non-systematic review of current research. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:792960. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2021.792960

6. Fagiolini A, Florea I, Loft H, et al. Effectiveness of vortioxetine on emotional blunting in patients with major depressive disorder with inadequate response to SSRI/SNRI treatment. J Affect Disord. 2021;283:472-479.

When a patient wants to stop taking their antipsychotic: Be ‘A SPORT’

For patients with schizophrenia, adherence to antipsychotic treatment reduces the rate of relapse of psychosis, lowers the rate of rehospitalization, and reduces the severity of illness.1 Despite this, patients may want to discontinue their medications for multiple reasons, including limited insight, adverse effects, or a negative attitude toward medication.1 Understanding a patient’s reason for wanting to discontinue their antipsychotic is critical to providing patient-centered care, building the therapeutic alliance, and offering potential solutions.

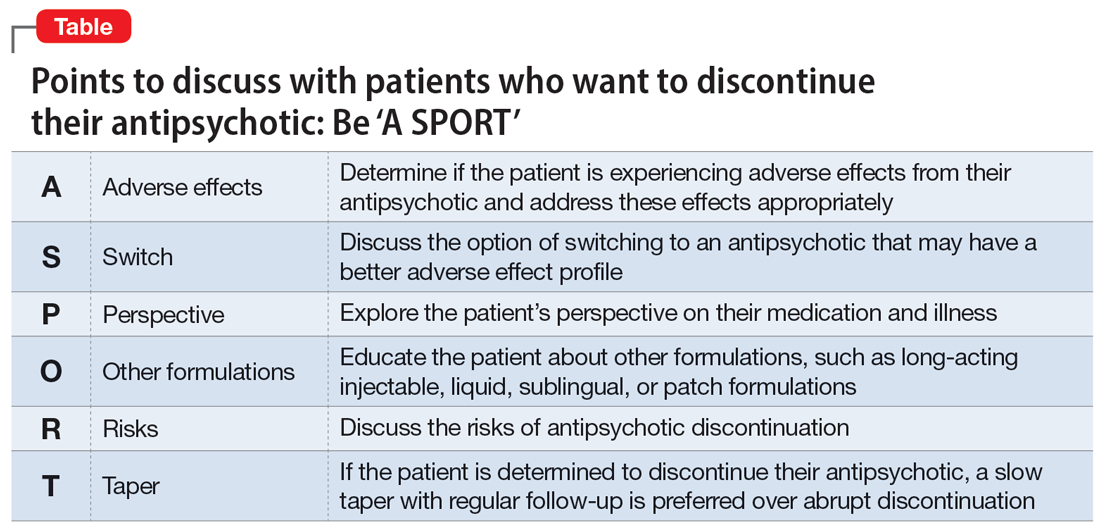

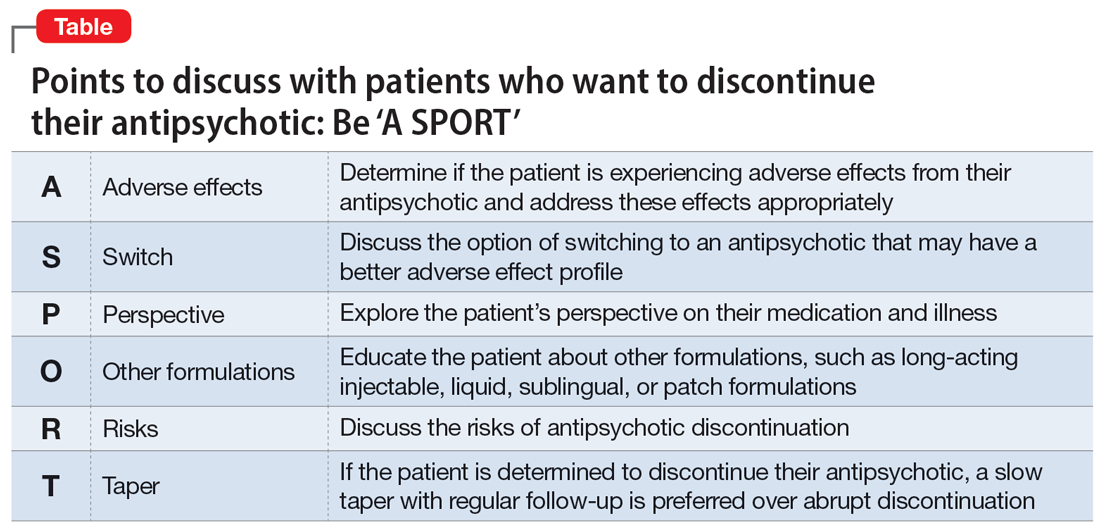

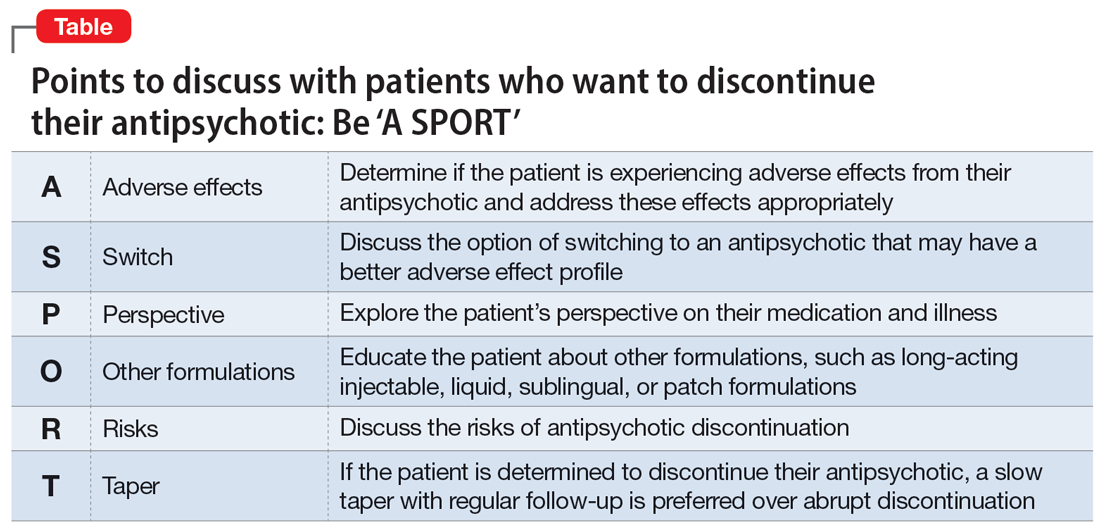

Clinicians can recall the mnemonic “A SPORT” (Table) to help ensure they have a thorough discussion with patients about the risks of discontinuation and potential solutions.

Points to cover

First, explore and acknowledge if a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, which may be causing them to have a negative attitude toward medications. If a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, offer interventions to mitigate those effects, such as adding an anticholinergic agent to address extrapyramidal symptoms. Decreasing the antipsychotic dosage might reduce the adverse effects burden while still optimizing the benefits from the antipsychotic. Additionally, switching to an alternate medication with a more favorable adverse effect profile may be an option. Whether the patient is experiencing intolerable adverse effects or just has a negative view of their prescribed antipsychotic, it is important to discuss switching medications.

Identifying patient attitudes and their general perspective toward their medication and illness is key. Similarly, a patient’s impaired insight into their mental illness has been associated with treatment discontinuation.2 A strong therapeutic alliance with your patient is of the utmost importance in these situations.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are useful clinical tools for patients who struggle to adhere to oral medications. Educating patients and caregivers about other formulations—namely LAIs—can help clarify any misconceptions they may have. One study found that patients who were prescribed oral antipsychotics thought LAIs would be painful, have worse adverse effects, and would not be beneficial in preventing relapse.3 In addition to LAIs, other formulations of antipsychotic medications, such as patches, sublingual tablets, or liquids, may be an option.

For patients to be able to provide informed consent regarding the decision to discontinue their antipsychotic, it is important to educate them about the risks of not taking an antipsychotic, such as an increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and poor outcomes. Explain that patients with first-episode psychosis who achieve remission of symptoms while taking an antipsychotic can remain in remission with continued treatment, but there is a 5-fold increased risk of relapse when discontinuing an antipsychotic during first-episode psychosis.4

Lastly, despite discussing the risks and benefits, if a patient is determined to discontinue their antipsychotic, we recommend a slow taper of medication rather than abrupt discontinuation. Research has shown that more than one-half of patients who abruptly discontinue an antipsychotic experience withdrawal symptoms, including (but not limited to) nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and headaches, as well as anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia.5 These symptoms may occur within 4 weeks after discontinuation.5 While there are no clear guidelines on deprescribing antipsychotics, it is best to individualize the taper based on patient response. Family and caregiver involvement, close follow-up, and symptom monitoring should be integrated into the tapering process.6

1. Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherenc. 2017;11:449-468. doi:10.2147/PPA.S124658

2. Kim J, Ozzoude M, Nakajima S, et al. Insight and medication adherence in schizophrenia: an analysis of the CATIE trial. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107634. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.05.011

3. Sugawara N, Kudo S, Ishioka M, et al. Attitudes toward long-acting injectable antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:205-211. doi:10.2147/NDT.S188337

4. Winton-Brown TT, Elanjithara T, Power P, et al. Five-fold increased risk of relapse following breaks in antipsychotic treatment of first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2017;179:50-56. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.029

5. Brandt L, Bschor T, Henssler J, et al. Antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569912. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569912

6. Gupta S, Cahill JD, Miller R. Deprescribing antipsychotics: a guide for clinicians. BJPsych Advances. 2018;24(5):295-302. doi:10.1192/bja.2018.2

For patients with schizophrenia, adherence to antipsychotic treatment reduces the rate of relapse of psychosis, lowers the rate of rehospitalization, and reduces the severity of illness.1 Despite this, patients may want to discontinue their medications for multiple reasons, including limited insight, adverse effects, or a negative attitude toward medication.1 Understanding a patient’s reason for wanting to discontinue their antipsychotic is critical to providing patient-centered care, building the therapeutic alliance, and offering potential solutions.

Clinicians can recall the mnemonic “A SPORT” (Table) to help ensure they have a thorough discussion with patients about the risks of discontinuation and potential solutions.

Points to cover

First, explore and acknowledge if a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, which may be causing them to have a negative attitude toward medications. If a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, offer interventions to mitigate those effects, such as adding an anticholinergic agent to address extrapyramidal symptoms. Decreasing the antipsychotic dosage might reduce the adverse effects burden while still optimizing the benefits from the antipsychotic. Additionally, switching to an alternate medication with a more favorable adverse effect profile may be an option. Whether the patient is experiencing intolerable adverse effects or just has a negative view of their prescribed antipsychotic, it is important to discuss switching medications.

Identifying patient attitudes and their general perspective toward their medication and illness is key. Similarly, a patient’s impaired insight into their mental illness has been associated with treatment discontinuation.2 A strong therapeutic alliance with your patient is of the utmost importance in these situations.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are useful clinical tools for patients who struggle to adhere to oral medications. Educating patients and caregivers about other formulations—namely LAIs—can help clarify any misconceptions they may have. One study found that patients who were prescribed oral antipsychotics thought LAIs would be painful, have worse adverse effects, and would not be beneficial in preventing relapse.3 In addition to LAIs, other formulations of antipsychotic medications, such as patches, sublingual tablets, or liquids, may be an option.

For patients to be able to provide informed consent regarding the decision to discontinue their antipsychotic, it is important to educate them about the risks of not taking an antipsychotic, such as an increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and poor outcomes. Explain that patients with first-episode psychosis who achieve remission of symptoms while taking an antipsychotic can remain in remission with continued treatment, but there is a 5-fold increased risk of relapse when discontinuing an antipsychotic during first-episode psychosis.4

Lastly, despite discussing the risks and benefits, if a patient is determined to discontinue their antipsychotic, we recommend a slow taper of medication rather than abrupt discontinuation. Research has shown that more than one-half of patients who abruptly discontinue an antipsychotic experience withdrawal symptoms, including (but not limited to) nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and headaches, as well as anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia.5 These symptoms may occur within 4 weeks after discontinuation.5 While there are no clear guidelines on deprescribing antipsychotics, it is best to individualize the taper based on patient response. Family and caregiver involvement, close follow-up, and symptom monitoring should be integrated into the tapering process.6

For patients with schizophrenia, adherence to antipsychotic treatment reduces the rate of relapse of psychosis, lowers the rate of rehospitalization, and reduces the severity of illness.1 Despite this, patients may want to discontinue their medications for multiple reasons, including limited insight, adverse effects, or a negative attitude toward medication.1 Understanding a patient’s reason for wanting to discontinue their antipsychotic is critical to providing patient-centered care, building the therapeutic alliance, and offering potential solutions.

Clinicians can recall the mnemonic “A SPORT” (Table) to help ensure they have a thorough discussion with patients about the risks of discontinuation and potential solutions.

Points to cover

First, explore and acknowledge if a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, which may be causing them to have a negative attitude toward medications. If a patient is experiencing adverse effects from their antipsychotic, offer interventions to mitigate those effects, such as adding an anticholinergic agent to address extrapyramidal symptoms. Decreasing the antipsychotic dosage might reduce the adverse effects burden while still optimizing the benefits from the antipsychotic. Additionally, switching to an alternate medication with a more favorable adverse effect profile may be an option. Whether the patient is experiencing intolerable adverse effects or just has a negative view of their prescribed antipsychotic, it is important to discuss switching medications.

Identifying patient attitudes and their general perspective toward their medication and illness is key. Similarly, a patient’s impaired insight into their mental illness has been associated with treatment discontinuation.2 A strong therapeutic alliance with your patient is of the utmost importance in these situations.

Long-acting injectable antipsychotics (LAIs) are useful clinical tools for patients who struggle to adhere to oral medications. Educating patients and caregivers about other formulations—namely LAIs—can help clarify any misconceptions they may have. One study found that patients who were prescribed oral antipsychotics thought LAIs would be painful, have worse adverse effects, and would not be beneficial in preventing relapse.3 In addition to LAIs, other formulations of antipsychotic medications, such as patches, sublingual tablets, or liquids, may be an option.

For patients to be able to provide informed consent regarding the decision to discontinue their antipsychotic, it is important to educate them about the risks of not taking an antipsychotic, such as an increased risk of relapse, hospitalization, and poor outcomes. Explain that patients with first-episode psychosis who achieve remission of symptoms while taking an antipsychotic can remain in remission with continued treatment, but there is a 5-fold increased risk of relapse when discontinuing an antipsychotic during first-episode psychosis.4

Lastly, despite discussing the risks and benefits, if a patient is determined to discontinue their antipsychotic, we recommend a slow taper of medication rather than abrupt discontinuation. Research has shown that more than one-half of patients who abruptly discontinue an antipsychotic experience withdrawal symptoms, including (but not limited to) nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and headaches, as well as anxiety, restlessness, and insomnia.5 These symptoms may occur within 4 weeks after discontinuation.5 While there are no clear guidelines on deprescribing antipsychotics, it is best to individualize the taper based on patient response. Family and caregiver involvement, close follow-up, and symptom monitoring should be integrated into the tapering process.6

1. Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherenc. 2017;11:449-468. doi:10.2147/PPA.S124658

2. Kim J, Ozzoude M, Nakajima S, et al. Insight and medication adherence in schizophrenia: an analysis of the CATIE trial. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107634. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.05.011

3. Sugawara N, Kudo S, Ishioka M, et al. Attitudes toward long-acting injectable antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:205-211. doi:10.2147/NDT.S188337

4. Winton-Brown TT, Elanjithara T, Power P, et al. Five-fold increased risk of relapse following breaks in antipsychotic treatment of first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2017;179:50-56. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.029

5. Brandt L, Bschor T, Henssler J, et al. Antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569912. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569912

6. Gupta S, Cahill JD, Miller R. Deprescribing antipsychotics: a guide for clinicians. BJPsych Advances. 2018;24(5):295-302. doi:10.1192/bja.2018.2

1. Velligan DI, Sajatovic M, Hatch A, et al. Why do psychiatric patients stop antipsychotic medication? A systematic review of reasons for nonadherence to medication in patients with serious mental illness. Patient Prefer Adherenc. 2017;11:449-468. doi:10.2147/PPA.S124658

2. Kim J, Ozzoude M, Nakajima S, et al. Insight and medication adherence in schizophrenia: an analysis of the CATIE trial. Neuropharmacology. 2020;168:107634. doi:10.1016/j.neuropharm.2019.05.011

3. Sugawara N, Kudo S, Ishioka M, et al. Attitudes toward long-acting injectable antipsychotics among patients with schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:205-211. doi:10.2147/NDT.S188337

4. Winton-Brown TT, Elanjithara T, Power P, et al. Five-fold increased risk of relapse following breaks in antipsychotic treatment of first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res. 2017;179:50-56. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2016.09.029

5. Brandt L, Bschor T, Henssler J, et al. Antipsychotic withdrawal symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:569912. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.569912

6. Gupta S, Cahill JD, Miller R. Deprescribing antipsychotics: a guide for clinicians. BJPsych Advances. 2018;24(5):295-302. doi:10.1192/bja.2018.2