User login

Endoscopic management of duodenal and ampullary adenomas

Duodenal polyps are a relatively rare entity with a reported incidence of 0.3%-4.6%.1 There are three major types of duodenal adenomas: sporadic, nonampullary duodenal adenomas (SNDAs), adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome, and ampullary adenomas. It is important to distinguish between the different types of duodenal polyps as the management may differ depending on the etiology.

SNDAs constitute <10% of all duodenal polyps, most commonly located in the second portion of the duodenum, and up to 85% have been shown to have malignant transformation over time.2 Most of the studies of SNDAs are small series, and there are no consensus guidelines for management. Villous features increase malignancy risk, thus resection of SNDAs is advised.3-7 It has also been shown that 72% of patients with SNDAs also have colon polyps,8 and therefore these patients should be up to date on colonoscopy screening.

Ampullary adenomas are less common, but up to half may be associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and some may be surveyed.9 However, those that are larger than 10 mm or have villous features may raise concern for malignancy with up to half harboring small foci of adenocarcinoma.10,11 These require ERCP with ampullectomy. For the purposes of this paper, we will focus on endoscopic resection of SNDAs and ampullary adenomas.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of duodenal polyps can be technically challenging. There are considerations specific to the duodenum: thin muscle layer, increased motility, and significant vascular supply including two major arterial supplies – the gastroduodenal artery from the celiac branch and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery from the superior mesenteric artery. These factors may explain higher reported rates of perforation and bleeding compared to colon EMR.

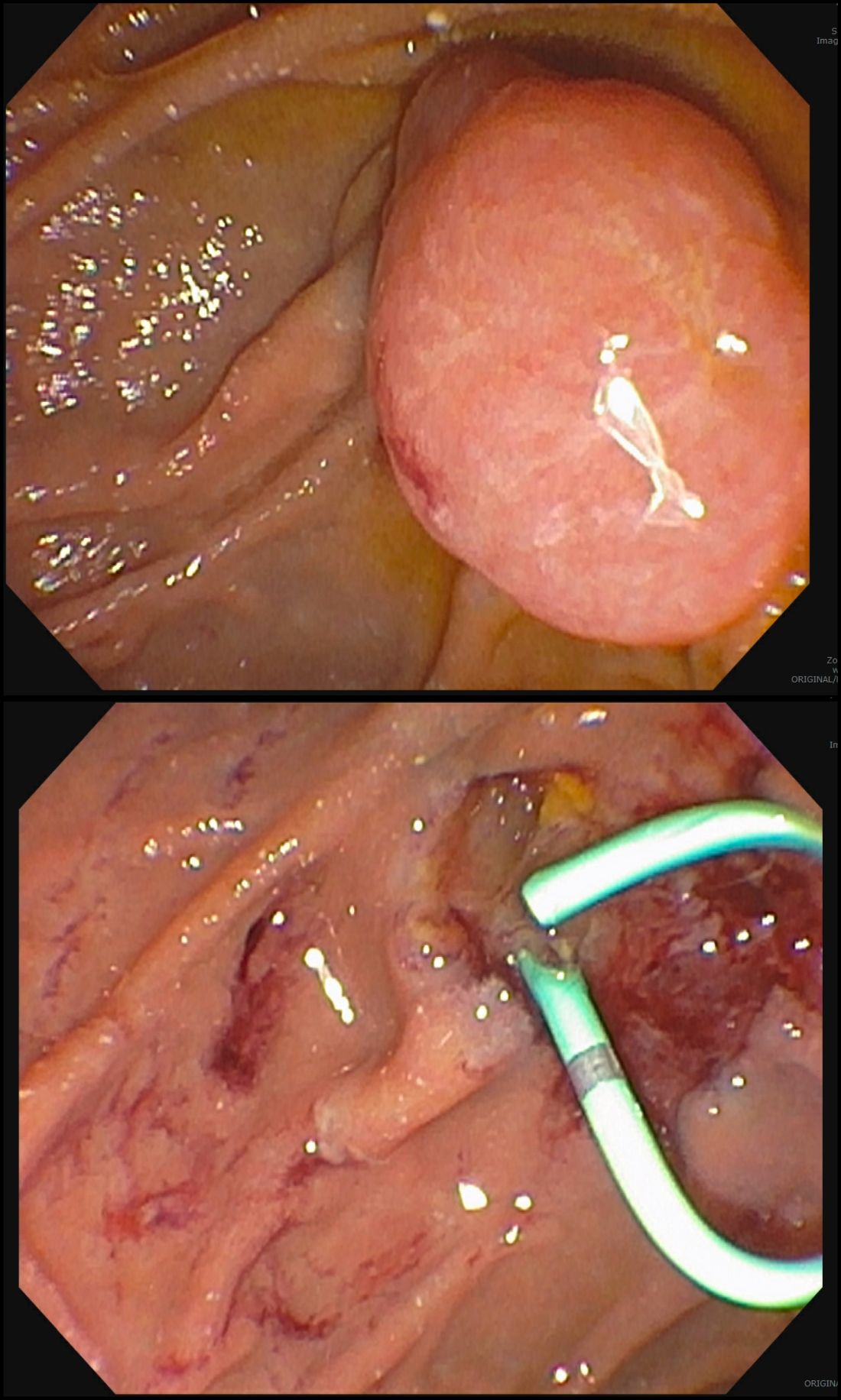

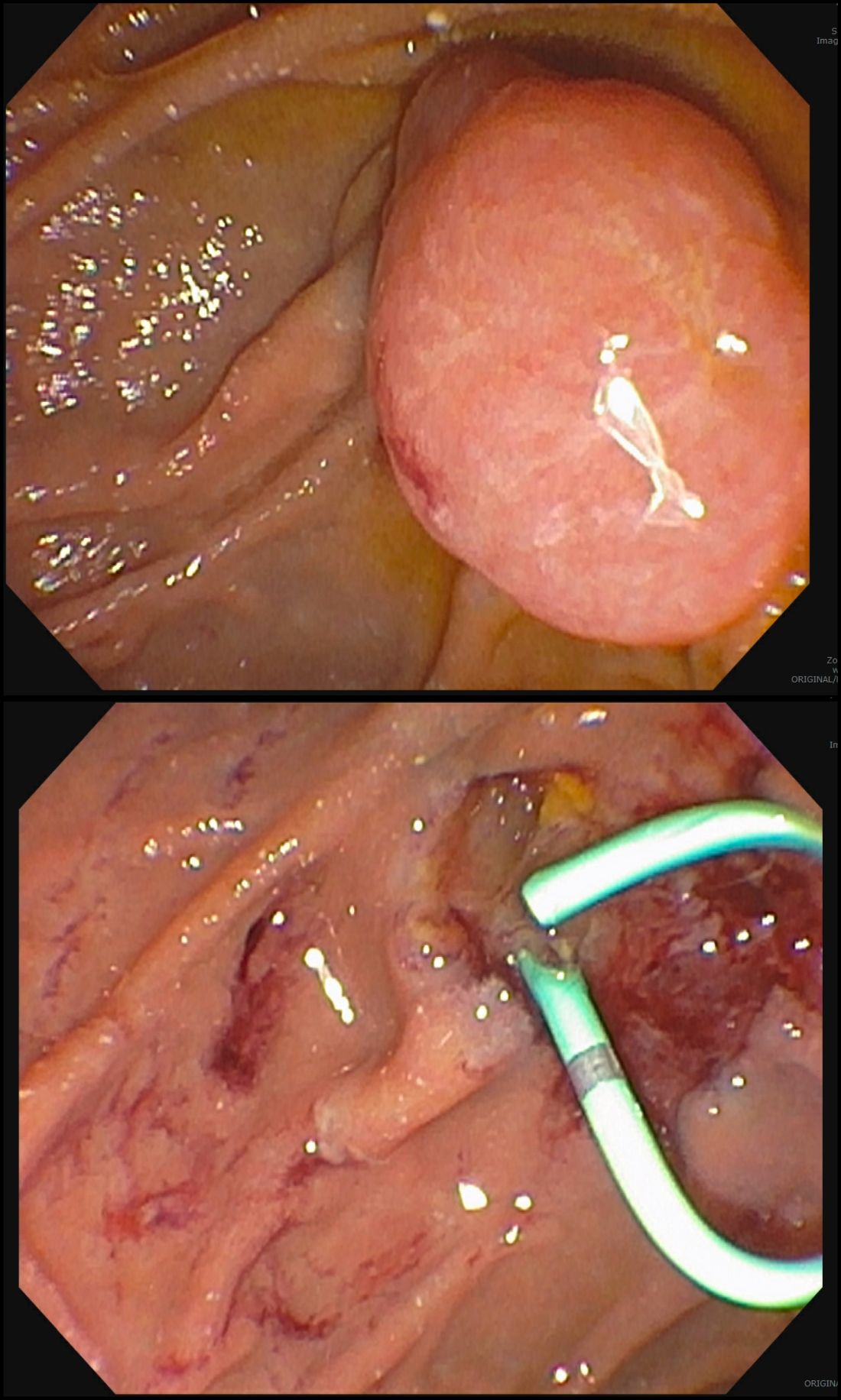

After a detailed inspection is performed to define the duodenal polyp in terms of size, location, and position relative to the ampulla, a submucosal injection is performed using a dye solution. Once adequate lift is achieved, the lesion is resected using stiff monofilament snares. If possible, resection sites are closed with hemostatic clips, although their utility in preventing delayed complications may be less than that in the colon because of increased motility causing them to become dislodged more easily. We avoid using snares larger than 2 cm given increased risk of perforation. Intraprocedural bleeding may be controlled with coagulation graspers on soft coagulation setting; using a bipolar electrocoagulation therapy or argon plasma coagulation is avoided, as these have been shown to increase rates of complications. Figure 1 provides examples of duodenal adenomas that have been resected.

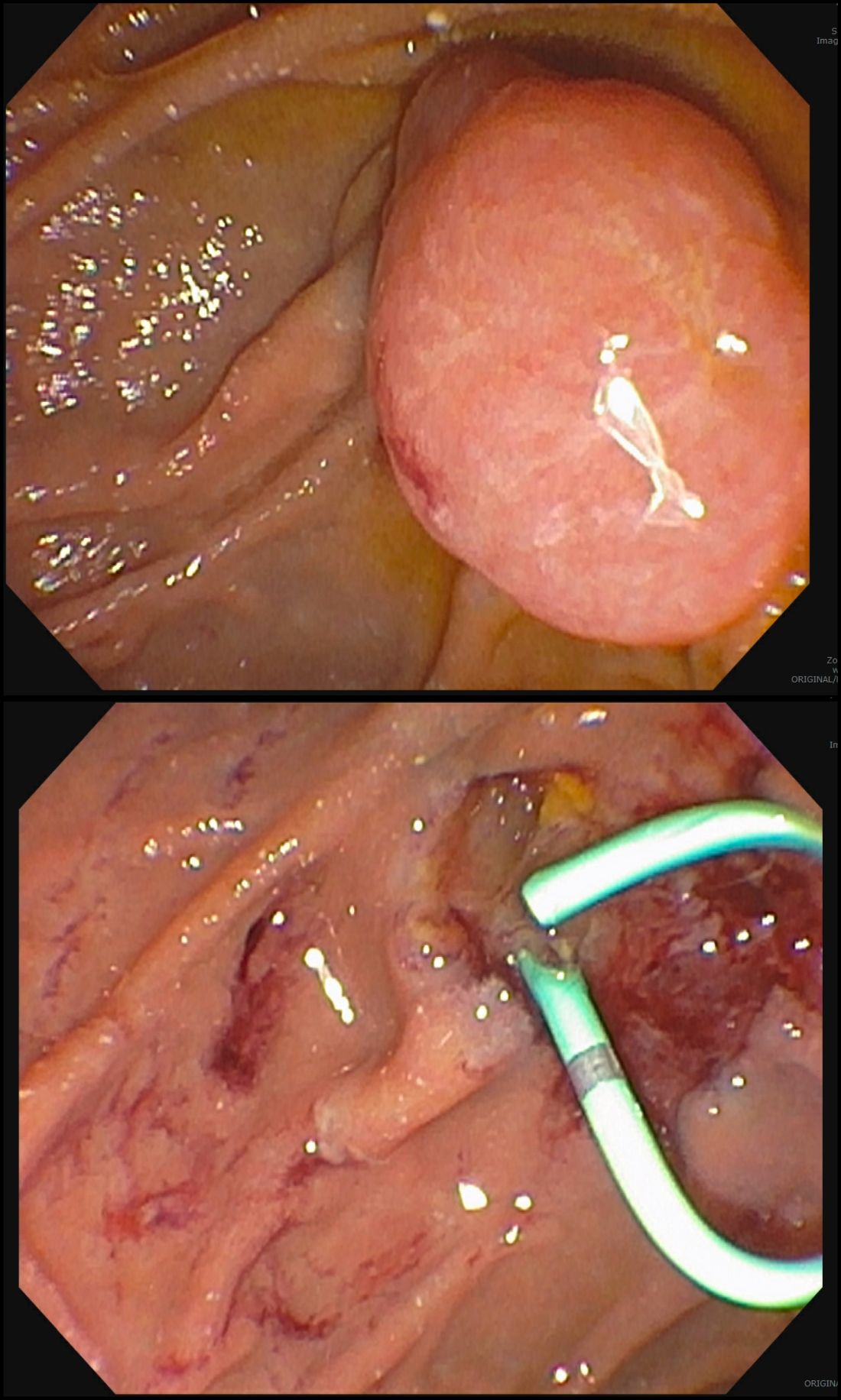

The ampullectomy technique is slightly different from duodenal EMRs and carries the additional risk of pancreatitis.12,13 In our opinion, there is low utility for submucosal injection unless there is a laterally spreading component onto the duodenal wall, as injection of the ampulla itself does not lift well and simply distorts views. Typically, both the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct are injected with contrast, and we typically perform a biliary sphincterotomy prior to ampullectomy. Based on endoscopist preference, one can also leave a guide wire in the pancreatic duct (PD) and pass the snare over it to perform resection to maintain access for a subsequent stent placement. This technique has the advantage of never losing pancreatic duct access, which can occur after resection from edema or bleeding and allows easy PD stent placement. The snare should be opened in a line corresponding to the long axis of the mound with the snare tip anchored above the apex of the papilla and snare opened and drawn down over the papilla. After resection, the PD must be stented to minimize pancreatitis risk.14 Figure 2 shows an ampullary adenoma pre and post EMR, with a PD stent.

Recurrence of duodenal adenomas, both SNDAs and ampullary, can be quite high, with reports up to 39%.15-18 Risk factors include histology and size, but interestingly were not shown to be associated with en-bloc resection.15,19 On the other hand, intraprocedural bleeding also occurs in up to 43% of patients and is associated with size, number of resections, and procedure time.20 Per 2015 ASGE Standards of Practice, duodenal lesions warrant short follow-up at 3- to 6-month intervals given high recurrence rates, then at 6- to 12-month intervals for 2-5 years thereafter.21

When a duodenal polyp is detected, it is important to determine which type of adenoma it is to guide management. There are various techniques utilized to perform duodenal EMR and ampullectomy with some highlighted in this article. It is important to understand how to recognize, prevent, and manage associated adverse events, as well as to have a surveillance plan given the risk of recurrence.

Dr. Kim has no disclosures. Dr. Siddiqui has financial relationships with Boston Scientific (research support, consulting fees, speaking honoraria); Cook, Medtronic, ConMed (consulting fees, speaking honoraria); and Pinnacle Biologic, Ovesco (speaking honoraria).

Dr. Kim is a GI fellow, section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of internal medicine, University of Chicago. Dr. Siddiqui is a professor of medicine and the director of the Center for Endoscopic Research and Therapeutics (CERT), section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of internal medicine, University of Chicago.

References

1. Jepsen JM et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. Jun 1994;29(6):483-7.

2. Sellner F. Cancer. 1990 Aug 15;66(4):702-15.

3. Witteman BJ et al. Neth J Med. 1993 Feb;42(1-2):5-11.

4. Reddy RR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981 Jun;3(2):139-47.

5. Sakorafas GH et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000 Apr;35(4):337-44.

6. Galandiuk S et al. Ann Surg. 1988 Mar;207(3):234-9.

7. Farnell MB et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000 Jan-Feb;4(1):13-21, discussion 22-3.

8. Apel D et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004 Sep;60(3):397-9.

9. Kashiwagi H et al. Lancet. 1994 Dec 3;344(8936):1582.

10. Clary BM et al. Surgery. 2000 Jun;127(6):628-33.

11. Posner S et al. Surgery. 2000 Oct;128(4):694-701.

12. Harewood GC et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005 Sep;62(3):367-70.

13. Chini P et al. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Dec 16;3(12):241-7.

14. Chang WI et al. Gut Liver. May 2014;8(3):306-12.

15. Hoibian S et al. Ann Gastroenterol. 2021;34(2):169-176. doi: 10.20524/aog.2021.0581.

16. Kakushima N et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep 21;20(35):12501-8.

17. Lienert A and Bagshaw PF. ANZ J Surg. 2007 May;77(5):371-3.

18. Singh A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Oct;84(4):700-8.

19. Tomizawa Y and Ginsberg GG. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 May;87(5):1270-8.

20. Klein A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Oct;84(4):688-96.

21. Chathadi KV et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Nov;82(5):773-81.

Duodenal polyps are a relatively rare entity with a reported incidence of 0.3%-4.6%.1 There are three major types of duodenal adenomas: sporadic, nonampullary duodenal adenomas (SNDAs), adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome, and ampullary adenomas. It is important to distinguish between the different types of duodenal polyps as the management may differ depending on the etiology.

SNDAs constitute <10% of all duodenal polyps, most commonly located in the second portion of the duodenum, and up to 85% have been shown to have malignant transformation over time.2 Most of the studies of SNDAs are small series, and there are no consensus guidelines for management. Villous features increase malignancy risk, thus resection of SNDAs is advised.3-7 It has also been shown that 72% of patients with SNDAs also have colon polyps,8 and therefore these patients should be up to date on colonoscopy screening.

Ampullary adenomas are less common, but up to half may be associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and some may be surveyed.9 However, those that are larger than 10 mm or have villous features may raise concern for malignancy with up to half harboring small foci of adenocarcinoma.10,11 These require ERCP with ampullectomy. For the purposes of this paper, we will focus on endoscopic resection of SNDAs and ampullary adenomas.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of duodenal polyps can be technically challenging. There are considerations specific to the duodenum: thin muscle layer, increased motility, and significant vascular supply including two major arterial supplies – the gastroduodenal artery from the celiac branch and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery from the superior mesenteric artery. These factors may explain higher reported rates of perforation and bleeding compared to colon EMR.

After a detailed inspection is performed to define the duodenal polyp in terms of size, location, and position relative to the ampulla, a submucosal injection is performed using a dye solution. Once adequate lift is achieved, the lesion is resected using stiff monofilament snares. If possible, resection sites are closed with hemostatic clips, although their utility in preventing delayed complications may be less than that in the colon because of increased motility causing them to become dislodged more easily. We avoid using snares larger than 2 cm given increased risk of perforation. Intraprocedural bleeding may be controlled with coagulation graspers on soft coagulation setting; using a bipolar electrocoagulation therapy or argon plasma coagulation is avoided, as these have been shown to increase rates of complications. Figure 1 provides examples of duodenal adenomas that have been resected.

The ampullectomy technique is slightly different from duodenal EMRs and carries the additional risk of pancreatitis.12,13 In our opinion, there is low utility for submucosal injection unless there is a laterally spreading component onto the duodenal wall, as injection of the ampulla itself does not lift well and simply distorts views. Typically, both the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct are injected with contrast, and we typically perform a biliary sphincterotomy prior to ampullectomy. Based on endoscopist preference, one can also leave a guide wire in the pancreatic duct (PD) and pass the snare over it to perform resection to maintain access for a subsequent stent placement. This technique has the advantage of never losing pancreatic duct access, which can occur after resection from edema or bleeding and allows easy PD stent placement. The snare should be opened in a line corresponding to the long axis of the mound with the snare tip anchored above the apex of the papilla and snare opened and drawn down over the papilla. After resection, the PD must be stented to minimize pancreatitis risk.14 Figure 2 shows an ampullary adenoma pre and post EMR, with a PD stent.

Recurrence of duodenal adenomas, both SNDAs and ampullary, can be quite high, with reports up to 39%.15-18 Risk factors include histology and size, but interestingly were not shown to be associated with en-bloc resection.15,19 On the other hand, intraprocedural bleeding also occurs in up to 43% of patients and is associated with size, number of resections, and procedure time.20 Per 2015 ASGE Standards of Practice, duodenal lesions warrant short follow-up at 3- to 6-month intervals given high recurrence rates, then at 6- to 12-month intervals for 2-5 years thereafter.21

When a duodenal polyp is detected, it is important to determine which type of adenoma it is to guide management. There are various techniques utilized to perform duodenal EMR and ampullectomy with some highlighted in this article. It is important to understand how to recognize, prevent, and manage associated adverse events, as well as to have a surveillance plan given the risk of recurrence.

Dr. Kim has no disclosures. Dr. Siddiqui has financial relationships with Boston Scientific (research support, consulting fees, speaking honoraria); Cook, Medtronic, ConMed (consulting fees, speaking honoraria); and Pinnacle Biologic, Ovesco (speaking honoraria).

Dr. Kim is a GI fellow, section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of internal medicine, University of Chicago. Dr. Siddiqui is a professor of medicine and the director of the Center for Endoscopic Research and Therapeutics (CERT), section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of internal medicine, University of Chicago.

References

1. Jepsen JM et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. Jun 1994;29(6):483-7.

2. Sellner F. Cancer. 1990 Aug 15;66(4):702-15.

3. Witteman BJ et al. Neth J Med. 1993 Feb;42(1-2):5-11.

4. Reddy RR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981 Jun;3(2):139-47.

5. Sakorafas GH et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000 Apr;35(4):337-44.

6. Galandiuk S et al. Ann Surg. 1988 Mar;207(3):234-9.

7. Farnell MB et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000 Jan-Feb;4(1):13-21, discussion 22-3.

8. Apel D et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004 Sep;60(3):397-9.

9. Kashiwagi H et al. Lancet. 1994 Dec 3;344(8936):1582.

10. Clary BM et al. Surgery. 2000 Jun;127(6):628-33.

11. Posner S et al. Surgery. 2000 Oct;128(4):694-701.

12. Harewood GC et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005 Sep;62(3):367-70.

13. Chini P et al. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Dec 16;3(12):241-7.

14. Chang WI et al. Gut Liver. May 2014;8(3):306-12.

15. Hoibian S et al. Ann Gastroenterol. 2021;34(2):169-176. doi: 10.20524/aog.2021.0581.

16. Kakushima N et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep 21;20(35):12501-8.

17. Lienert A and Bagshaw PF. ANZ J Surg. 2007 May;77(5):371-3.

18. Singh A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Oct;84(4):700-8.

19. Tomizawa Y and Ginsberg GG. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 May;87(5):1270-8.

20. Klein A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Oct;84(4):688-96.

21. Chathadi KV et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Nov;82(5):773-81.

Duodenal polyps are a relatively rare entity with a reported incidence of 0.3%-4.6%.1 There are three major types of duodenal adenomas: sporadic, nonampullary duodenal adenomas (SNDAs), adenomas in familial adenomatous polyposis syndrome, and ampullary adenomas. It is important to distinguish between the different types of duodenal polyps as the management may differ depending on the etiology.

SNDAs constitute <10% of all duodenal polyps, most commonly located in the second portion of the duodenum, and up to 85% have been shown to have malignant transformation over time.2 Most of the studies of SNDAs are small series, and there are no consensus guidelines for management. Villous features increase malignancy risk, thus resection of SNDAs is advised.3-7 It has also been shown that 72% of patients with SNDAs also have colon polyps,8 and therefore these patients should be up to date on colonoscopy screening.

Ampullary adenomas are less common, but up to half may be associated with familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP), and some may be surveyed.9 However, those that are larger than 10 mm or have villous features may raise concern for malignancy with up to half harboring small foci of adenocarcinoma.10,11 These require ERCP with ampullectomy. For the purposes of this paper, we will focus on endoscopic resection of SNDAs and ampullary adenomas.

Endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR) of duodenal polyps can be technically challenging. There are considerations specific to the duodenum: thin muscle layer, increased motility, and significant vascular supply including two major arterial supplies – the gastroduodenal artery from the celiac branch and the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery from the superior mesenteric artery. These factors may explain higher reported rates of perforation and bleeding compared to colon EMR.

After a detailed inspection is performed to define the duodenal polyp in terms of size, location, and position relative to the ampulla, a submucosal injection is performed using a dye solution. Once adequate lift is achieved, the lesion is resected using stiff monofilament snares. If possible, resection sites are closed with hemostatic clips, although their utility in preventing delayed complications may be less than that in the colon because of increased motility causing them to become dislodged more easily. We avoid using snares larger than 2 cm given increased risk of perforation. Intraprocedural bleeding may be controlled with coagulation graspers on soft coagulation setting; using a bipolar electrocoagulation therapy or argon plasma coagulation is avoided, as these have been shown to increase rates of complications. Figure 1 provides examples of duodenal adenomas that have been resected.

The ampullectomy technique is slightly different from duodenal EMRs and carries the additional risk of pancreatitis.12,13 In our opinion, there is low utility for submucosal injection unless there is a laterally spreading component onto the duodenal wall, as injection of the ampulla itself does not lift well and simply distorts views. Typically, both the common bile duct and the pancreatic duct are injected with contrast, and we typically perform a biliary sphincterotomy prior to ampullectomy. Based on endoscopist preference, one can also leave a guide wire in the pancreatic duct (PD) and pass the snare over it to perform resection to maintain access for a subsequent stent placement. This technique has the advantage of never losing pancreatic duct access, which can occur after resection from edema or bleeding and allows easy PD stent placement. The snare should be opened in a line corresponding to the long axis of the mound with the snare tip anchored above the apex of the papilla and snare opened and drawn down over the papilla. After resection, the PD must be stented to minimize pancreatitis risk.14 Figure 2 shows an ampullary adenoma pre and post EMR, with a PD stent.

Recurrence of duodenal adenomas, both SNDAs and ampullary, can be quite high, with reports up to 39%.15-18 Risk factors include histology and size, but interestingly were not shown to be associated with en-bloc resection.15,19 On the other hand, intraprocedural bleeding also occurs in up to 43% of patients and is associated with size, number of resections, and procedure time.20 Per 2015 ASGE Standards of Practice, duodenal lesions warrant short follow-up at 3- to 6-month intervals given high recurrence rates, then at 6- to 12-month intervals for 2-5 years thereafter.21

When a duodenal polyp is detected, it is important to determine which type of adenoma it is to guide management. There are various techniques utilized to perform duodenal EMR and ampullectomy with some highlighted in this article. It is important to understand how to recognize, prevent, and manage associated adverse events, as well as to have a surveillance plan given the risk of recurrence.

Dr. Kim has no disclosures. Dr. Siddiqui has financial relationships with Boston Scientific (research support, consulting fees, speaking honoraria); Cook, Medtronic, ConMed (consulting fees, speaking honoraria); and Pinnacle Biologic, Ovesco (speaking honoraria).

Dr. Kim is a GI fellow, section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of internal medicine, University of Chicago. Dr. Siddiqui is a professor of medicine and the director of the Center for Endoscopic Research and Therapeutics (CERT), section of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition, department of internal medicine, University of Chicago.

References

1. Jepsen JM et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. Jun 1994;29(6):483-7.

2. Sellner F. Cancer. 1990 Aug 15;66(4):702-15.

3. Witteman BJ et al. Neth J Med. 1993 Feb;42(1-2):5-11.

4. Reddy RR et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1981 Jun;3(2):139-47.

5. Sakorafas GH et al. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2000 Apr;35(4):337-44.

6. Galandiuk S et al. Ann Surg. 1988 Mar;207(3):234-9.

7. Farnell MB et al. J Gastrointest Surg. 2000 Jan-Feb;4(1):13-21, discussion 22-3.

8. Apel D et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004 Sep;60(3):397-9.

9. Kashiwagi H et al. Lancet. 1994 Dec 3;344(8936):1582.

10. Clary BM et al. Surgery. 2000 Jun;127(6):628-33.

11. Posner S et al. Surgery. 2000 Oct;128(4):694-701.

12. Harewood GC et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005 Sep;62(3):367-70.

13. Chini P et al. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Dec 16;3(12):241-7.

14. Chang WI et al. Gut Liver. May 2014;8(3):306-12.

15. Hoibian S et al. Ann Gastroenterol. 2021;34(2):169-176. doi: 10.20524/aog.2021.0581.

16. Kakushima N et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep 21;20(35):12501-8.

17. Lienert A and Bagshaw PF. ANZ J Surg. 2007 May;77(5):371-3.

18. Singh A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Oct;84(4):700-8.

19. Tomizawa Y and Ginsberg GG. Gastrointest Endosc. 2018 May;87(5):1270-8.

20. Klein A et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2016 Oct;84(4):688-96.

21. Chathadi KV et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Nov;82(5):773-81.