User login

When to recommend cognitive behavioral therapy

› Tell patients who are potential candidates for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that it has been demonstrated to be effective in treating anxiety and trauma-related disorders. A

› Motivate patients by pointing out that CBT is short-term therapy that is cost-effective and has the potential to be more beneficial than medication. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Darla S, a 42-year-old being treated for gastrointestinal (GI) distress, has undergone multiple tests over the course of the year, including a colonoscopy, an endoscopy, and a food allergy work-up. All had negative results. Medication trials—with proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists, and prokinetics, among others—have not brought her any relief. The patient recently began taking sertraline 200 mg/d, which seemed to be helping. But on her latest visit, Ms. S requests a prescription for a sleeping pill. When asked what’s been keeping her up, the patient confides that she recently began having nightmares relating to a sexual assault that occurred several years ago.

If Ms. S were your patient, what would you recommend?

Family physicians (FPs) often encounter patients who are experiencing psychological distress, particularly anxiety.1 This may become evident when you’re treating one problem, such as low back pain or GI distress, but come to realize that anxiety is a key contributing factor or cause. Or you may discover that an anxiety or trauma-related disorder is complicating or interfering with treatment—preventing a patient with heart disease from quitting smoking, exercising regularly, or following a heart-healthy diet, for example.

Psychotropic medication is an option in such cases, of course. But the drugs often have adverse effects or interact with other medications the patient is taking, and their effects typically last only as long as the course of treatment. Being familiar with effective nonpharmacologic treatments—most notably, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—will help you provide such patients with optimal care.

Advantages. CBT has several advantages that supportive counseling, traditional psychotherapy, and other nonpharmacologic treatments for psychological disorders do not: It is time-limited, typically lasting 9 to 12 weeks; skill-based; and goal-oriented. It also has a large amount of data to support it.2-4

Chances are you are familiar with the basic elements of CBT—challenging problematic beliefs, ensuring an increase in pleasant activities, and providing extended exposure to places or activities that trigger avoidance and/or arousal so that these responses are gradually diminished.2 However, there is not one single model of CBT. Rather, there are specific protocols for the conditions included in this review (TABLE 1).5

But before we get to the protocols, let’s first look at the evidence.

Meta-analyses demonstrate efficacy and effectiveness

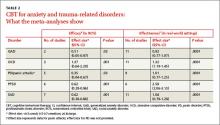

Multiple studies and meta-analyses have consistently found CBT to reduce symptoms associated with anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Foremost among them are a metaanalysis by Hofmann and Smits6 of randomized placebo-controlled studies that assessed CBT’s efficacy and a meta-analysis by Stewart and Chambless7 that focused instead on effectiveness studies—ie, those assessing CBT in less-controlled, real-world practice. The findings are highlighted in TABLE 2.6,7

A 2012 review of meta-analyses of CBT8 for a broader range of psychological disorders found it to be more effective in treating generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder (PD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and social anxiety disorder (SAD) than control conditions, such as placebo, and often more effective than other treatments. Notably, CBT was shown to be more effective than relaxation therapy for PD, more effective in the long term than psychopharmacology for SAD, and more effective than supportive counseling for PTSD.

Cognitive processing and exposure therapy for PTSD

Two types of CBT have been found to be particularly effective in treating PTSD: cognitive processing therapy and exposure therapy. Each has specific protocols, although treatment often has some components of each.9

Cognitive processing therapy, a firstline treatment for PTSD, was initially developed for the treatment of rape victims,10 but has been found to be effective in treating combat-related PTSD, as well.11 It incorporates the core elements of cognitive therapy—identifying false or unhelpful trauma-related thoughts, then evaluating the evidence for and against them so the patient learns to consider whether these problematic thoughts are the result of cognitive bias or error and develop more realistic and/or useful thoughts. Cognitive processing therapy, however, focuses primarily on issues of safety, danger, and trust relating to patients’ views of themselves, others, and the world. Patients are asked to write, and then read, a narrative of the trauma they endured to help them challenge troubling thoughts about it.10

A woman undergoing treatment for PTSD relating to a sexual assault, for example, may initially think, “All men are bad.” Challenging this thought by examining evidence for and against it may help her replace it with the more realistic belief that some—but not all—men are bad.

Exposure therapy, which is also a firstline treatment for PTSD,12-14 involves presenting the frightening stimuli to patients in a safe environment so that they can learn a new way of responding.9 If a patient is afraid of a specific location because she was assaulted there, for instance, slowly exposing her to the site while ensuring her safety can help her anxiety diminish. Depending on the circumstances, exposure may be conducted in vivo (tangible stimuli), achieved through mental imagery (of a combat zone where an improvised explosive device detonated, for example), or both.

Prolonged exposure has been shown to be very effective in treating PTSD resulting from a variety of traumatic events. Other aspects of treatment include education about the disorder and breathing retraining to reduce arousal and increase the patient’s ability to relax.15

Generalized anxiety disorder: Worry exposure and relaxation

CBT for GAD has 5 components:

- education about the disorder

- cognitive restructuring

- progressive muscle relaxation

- worry exposure

- in vivo exposure.

Relaxation training is a crucial part of treatment for GAD, perhaps more so than for other anxiety disorders.16 Cognitive restructuring is vital, as well. This involves the use of the Socratic means of questioning, asking “Tell me what you mean by ‘horrible,’” for example, and “What about that is of most concern to you?”

Worry exposure occurs by instructing the patient to engage in prolonged worry about one particular topic, rather than jumping from one worrisome subject to another. The single focus reduces the distress that worry causes, thereby decreasing the time spent worrying.17 As treatment progresses, the patient is taught to set aside a specific time to worry. Worrying outside of the designated “worry time” is not allowed.18,19

Panic disorder: Recognizing what's behind physical symptoms

Treatment for PD combines education about the disorder, cognitive restructuring, and exposure.

Education helps the patient understand the reason the increased arousal response occurs at seemingly random times—recognizing that he or she is interpreting normal physiological sensations negatively, for example, and that the physical response is the body’s way of protecting itself.

Cognitive restructuring helps patients reformulate their view of the relationship between physical symptoms and panic attacks. An individual might learn to interpret a rapid heart rate as an indication that his heart is working harder and getting stronger, for instance, rather than as a symptom of cardiovascular distress.

Interoceptive exposure therapy teaches patients to identify their internal physical cues (eg, shortness of breath, shakiness, and tachycardia) and then deliberately induce them—by breathing through a straw, climbing a flight of stairs, or spinning in a chair, for example. With repeated exposure, patients learn that the physical sensations are not dangerous, and the anxiety associated with them decreases.

In vivo exposure involves the creation of a “fear hierarchy” of places and activities that the patient avoids due to fear of having a panic attack, then gradually exposing him or her to them.18,20

Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Exposure and response

Exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the primary treatment for OCD. However, this seemingly straightforward behavioral treatment can be very challenging to implement because the compulsion that reduces a patient’s anxiety may be a mental act—silently repeating a number or phrase until the distress is released, for example—and thus unobservable.

Treatment consists of first helping the patient recognize his or her recurrent thoughts, behaviors, or mental acts, then identifying triggers for these compulsions. Next, the patient is gradually exposed to these triggers without being allowed to engage in the compulsive response that typically follows.21,22 For example, a clinician may have a patient obsessed with germs pick objects out of the trash during a therapy session but not allow hand washing afterwards or repeatedly write or say a number or word that normally elicits compulsive behavior but prevent the patient from engaging in it.

Social anxiety disorder: Group therapy

Group therapy, in which the group setting itself becomes a type of exposure, is a very effective treatment for SAD.23 This can be challenging, however, as patients with this disorder may be less likely to seek treatment if they know they will be put into a group. Individual treatment is another option for patients with SAD, and can be equally effective.24

Cognitive restructuring of anxiety-provoking thoughts (eg, “Everyone will think I’m stupid”) and exposure to social situations and cues that patients with this disorder typically avoid are other key components of treatment.25,26 Exposure often occurs outside of the therapy setting. Patients may be instructed to go to a cafeteria and have lunch alone without looking at their phone or reading a book, for instance, or to go to a coffee shop and strike up a conversation with someone of the opposite sex while in line. Exposures within the therapeutic setting may involve associates of the therapist to help create an anxiety-provoking environment—eg, having a patient give an impromptu speech in front of an attractive associate of the opposite sex.

Where psychopharmacology fits in

While CBT is clearly a viable alternative to medication, psychopharmacology is sometimes indicated for anxiety or trauma-related disorders, depending on the diagnosis and on whether psychotherapy is ongoing.27 Evidence shows that specific types of drugs are effective for treating some anxiety-related disorders, while other medications may worsen symptoms (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of PD, while benzodiazepines are contraindicated for patients with PTSD).27-29 Other research has found that a combined approach (psychotherapy plus medication) can be effective for the treatment of some anxiety disorders, including OCD.30 Although the combination may initially assist patients in their efforts to manage troublesome symptoms, in some cases it may limit the gains made from CBT.31

Talking to patients about CBT

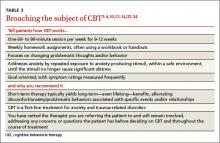

In discussing treatment options with patients with anxiety or trauma-related disorders (TABLE 3),2-4,10,12-14,32-34 it is important to note that psychotherapy—and particularly CBT—may be more cost-effective and have longerlasting effects than medication.32-34 Explain that it is a short-term treatment (typically lasting 9 to 12 weeks) but has been found to have long-term results.2-4,6,7 Point out, too, that patients who engage in CBT are likely to learn new skills, some of which may last a lifetime—and do not have to worry about adverse effects or potential drug-drug interactions as they would if they opted for psychopharmacology instead.

Finally, tell patients that you have vetted the practitioners you refer patients to and that you will continue to see them while they undergo treatment to ensure that the CBT is progressing well and following the established protocol.

CASE › Ms. S’s primary care physician considers prescribing alprazolam, but is concerned because this anti-anxiety medication can be habit-forming. Noting that although the patient is already taking sertraline, her distress related to the trauma appears to be worsening, the doctor suggests Ms. S try CBT. He explains that CBT is time-limited but has been found to have substantial long-lasting benefits for women who, like her, have been victims of sexual assault. The physician also tells Ms. S that CBT follows a specific protocol that typically consists of 9 to 12 weekly sessions; includes homework assignments and often follows a manual; is goal-oriented and measurable; and focuses on changing present behavior, thoughts, and feelings.

When Ms. S agrees to a referral, her physician assures her that he has vetted the practitioner and asks her to come in after 12 weeks of CBT so he can monitor her progress.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott Coffey, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; scoffey@umc.edu

1. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317-325.

2. Beck JS. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Basics and Beyond. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

3. Dobson KS, ed. Handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002.

4. Hollon SD, Beck AT. Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In: Bergin AE, Garfield SL, eds. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1994:428-466.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:621-632.

7. Stewart RE, Chambless DL. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:595-606.

8. Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, et al. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Ther Res. 2012;36:427-440.

9. Cahill SP, Rothbaum BO, Resick PA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, et al, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009:139-222.

10. Resick PA, Schnicke M. Cognitive Processing Therapy for Rape Victims: A Treatment Manual. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993.

11. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, et al. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:898-907.

12. Bisson J, Andrew M. Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD003388.

13. Bisson JI, Ehlers A, Matthews R, et al. Psychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:97-104.

14. Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, et al. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:635-641.

15. Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO. Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences Therapist Guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

16. Borkovec T, Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive- behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:611-619.

17. Provencher MD, Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R. Efficacy of problemsolving training and cognitive exposure in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a case replication series. Cognitive Behav Pract. 2004;11:404-414.

18. Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Worry: Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

19. Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Worry: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

20. Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic: Therapist Guide. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

21. Foa EB, Yadin E, Lichner TK. Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

22. Yazdin E, Foa EB, Kuchner TK. Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

23. Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Hope DA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment: Description, case presentation, and empirical support. In: Stein MB, ed. Social Phobia: Clinical and Research Perspectives. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995:293-321.

24. Stangier U, Heidenreich T, Peitz M, et al. Cognitive therapy for social phobia: individual versus group treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:991-1007.

25. Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Turk CL. Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

26. Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Turk CL. Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach: Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

27. Ravindran LN, Stein MB. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders: a review of progress. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;7:839-854.

28. Bernardy NC. The role of benzodiazepines in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD Res Q. 2013;23:1-9.

29. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, et al, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

30. Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, et al. Randomized, placebocontrolled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:151-161.

31. Otto MW, Smits JAJ, Reese HE. Combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for mood and anxiety disorders in adults: Review and analysis. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract. 2005;12:72-86.

32. Antonuccio DO, Thomas M, Danton WG. A cost-effectiveness analysis of cognitive behavior therapy and fluoxetine (prozac) in the treatment of depression. Behav Ther. 1997;28:187-210.

33. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:2529-2536.

34. Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH, et al. Cognitive behavioral and pharmacological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1997;28:285-305.

› Tell patients who are potential candidates for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that it has been demonstrated to be effective in treating anxiety and trauma-related disorders. A

› Motivate patients by pointing out that CBT is short-term therapy that is cost-effective and has the potential to be more beneficial than medication. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Darla S, a 42-year-old being treated for gastrointestinal (GI) distress, has undergone multiple tests over the course of the year, including a colonoscopy, an endoscopy, and a food allergy work-up. All had negative results. Medication trials—with proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists, and prokinetics, among others—have not brought her any relief. The patient recently began taking sertraline 200 mg/d, which seemed to be helping. But on her latest visit, Ms. S requests a prescription for a sleeping pill. When asked what’s been keeping her up, the patient confides that she recently began having nightmares relating to a sexual assault that occurred several years ago.

If Ms. S were your patient, what would you recommend?

Family physicians (FPs) often encounter patients who are experiencing psychological distress, particularly anxiety.1 This may become evident when you’re treating one problem, such as low back pain or GI distress, but come to realize that anxiety is a key contributing factor or cause. Or you may discover that an anxiety or trauma-related disorder is complicating or interfering with treatment—preventing a patient with heart disease from quitting smoking, exercising regularly, or following a heart-healthy diet, for example.

Psychotropic medication is an option in such cases, of course. But the drugs often have adverse effects or interact with other medications the patient is taking, and their effects typically last only as long as the course of treatment. Being familiar with effective nonpharmacologic treatments—most notably, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—will help you provide such patients with optimal care.

Advantages. CBT has several advantages that supportive counseling, traditional psychotherapy, and other nonpharmacologic treatments for psychological disorders do not: It is time-limited, typically lasting 9 to 12 weeks; skill-based; and goal-oriented. It also has a large amount of data to support it.2-4

Chances are you are familiar with the basic elements of CBT—challenging problematic beliefs, ensuring an increase in pleasant activities, and providing extended exposure to places or activities that trigger avoidance and/or arousal so that these responses are gradually diminished.2 However, there is not one single model of CBT. Rather, there are specific protocols for the conditions included in this review (TABLE 1).5

But before we get to the protocols, let’s first look at the evidence.

Meta-analyses demonstrate efficacy and effectiveness

Multiple studies and meta-analyses have consistently found CBT to reduce symptoms associated with anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Foremost among them are a metaanalysis by Hofmann and Smits6 of randomized placebo-controlled studies that assessed CBT’s efficacy and a meta-analysis by Stewart and Chambless7 that focused instead on effectiveness studies—ie, those assessing CBT in less-controlled, real-world practice. The findings are highlighted in TABLE 2.6,7

A 2012 review of meta-analyses of CBT8 for a broader range of psychological disorders found it to be more effective in treating generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder (PD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and social anxiety disorder (SAD) than control conditions, such as placebo, and often more effective than other treatments. Notably, CBT was shown to be more effective than relaxation therapy for PD, more effective in the long term than psychopharmacology for SAD, and more effective than supportive counseling for PTSD.

Cognitive processing and exposure therapy for PTSD

Two types of CBT have been found to be particularly effective in treating PTSD: cognitive processing therapy and exposure therapy. Each has specific protocols, although treatment often has some components of each.9

Cognitive processing therapy, a firstline treatment for PTSD, was initially developed for the treatment of rape victims,10 but has been found to be effective in treating combat-related PTSD, as well.11 It incorporates the core elements of cognitive therapy—identifying false or unhelpful trauma-related thoughts, then evaluating the evidence for and against them so the patient learns to consider whether these problematic thoughts are the result of cognitive bias or error and develop more realistic and/or useful thoughts. Cognitive processing therapy, however, focuses primarily on issues of safety, danger, and trust relating to patients’ views of themselves, others, and the world. Patients are asked to write, and then read, a narrative of the trauma they endured to help them challenge troubling thoughts about it.10

A woman undergoing treatment for PTSD relating to a sexual assault, for example, may initially think, “All men are bad.” Challenging this thought by examining evidence for and against it may help her replace it with the more realistic belief that some—but not all—men are bad.

Exposure therapy, which is also a firstline treatment for PTSD,12-14 involves presenting the frightening stimuli to patients in a safe environment so that they can learn a new way of responding.9 If a patient is afraid of a specific location because she was assaulted there, for instance, slowly exposing her to the site while ensuring her safety can help her anxiety diminish. Depending on the circumstances, exposure may be conducted in vivo (tangible stimuli), achieved through mental imagery (of a combat zone where an improvised explosive device detonated, for example), or both.

Prolonged exposure has been shown to be very effective in treating PTSD resulting from a variety of traumatic events. Other aspects of treatment include education about the disorder and breathing retraining to reduce arousal and increase the patient’s ability to relax.15

Generalized anxiety disorder: Worry exposure and relaxation

CBT for GAD has 5 components:

- education about the disorder

- cognitive restructuring

- progressive muscle relaxation

- worry exposure

- in vivo exposure.

Relaxation training is a crucial part of treatment for GAD, perhaps more so than for other anxiety disorders.16 Cognitive restructuring is vital, as well. This involves the use of the Socratic means of questioning, asking “Tell me what you mean by ‘horrible,’” for example, and “What about that is of most concern to you?”

Worry exposure occurs by instructing the patient to engage in prolonged worry about one particular topic, rather than jumping from one worrisome subject to another. The single focus reduces the distress that worry causes, thereby decreasing the time spent worrying.17 As treatment progresses, the patient is taught to set aside a specific time to worry. Worrying outside of the designated “worry time” is not allowed.18,19

Panic disorder: Recognizing what's behind physical symptoms

Treatment for PD combines education about the disorder, cognitive restructuring, and exposure.

Education helps the patient understand the reason the increased arousal response occurs at seemingly random times—recognizing that he or she is interpreting normal physiological sensations negatively, for example, and that the physical response is the body’s way of protecting itself.

Cognitive restructuring helps patients reformulate their view of the relationship between physical symptoms and panic attacks. An individual might learn to interpret a rapid heart rate as an indication that his heart is working harder and getting stronger, for instance, rather than as a symptom of cardiovascular distress.

Interoceptive exposure therapy teaches patients to identify their internal physical cues (eg, shortness of breath, shakiness, and tachycardia) and then deliberately induce them—by breathing through a straw, climbing a flight of stairs, or spinning in a chair, for example. With repeated exposure, patients learn that the physical sensations are not dangerous, and the anxiety associated with them decreases.

In vivo exposure involves the creation of a “fear hierarchy” of places and activities that the patient avoids due to fear of having a panic attack, then gradually exposing him or her to them.18,20

Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Exposure and response

Exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the primary treatment for OCD. However, this seemingly straightforward behavioral treatment can be very challenging to implement because the compulsion that reduces a patient’s anxiety may be a mental act—silently repeating a number or phrase until the distress is released, for example—and thus unobservable.

Treatment consists of first helping the patient recognize his or her recurrent thoughts, behaviors, or mental acts, then identifying triggers for these compulsions. Next, the patient is gradually exposed to these triggers without being allowed to engage in the compulsive response that typically follows.21,22 For example, a clinician may have a patient obsessed with germs pick objects out of the trash during a therapy session but not allow hand washing afterwards or repeatedly write or say a number or word that normally elicits compulsive behavior but prevent the patient from engaging in it.

Social anxiety disorder: Group therapy

Group therapy, in which the group setting itself becomes a type of exposure, is a very effective treatment for SAD.23 This can be challenging, however, as patients with this disorder may be less likely to seek treatment if they know they will be put into a group. Individual treatment is another option for patients with SAD, and can be equally effective.24

Cognitive restructuring of anxiety-provoking thoughts (eg, “Everyone will think I’m stupid”) and exposure to social situations and cues that patients with this disorder typically avoid are other key components of treatment.25,26 Exposure often occurs outside of the therapy setting. Patients may be instructed to go to a cafeteria and have lunch alone without looking at their phone or reading a book, for instance, or to go to a coffee shop and strike up a conversation with someone of the opposite sex while in line. Exposures within the therapeutic setting may involve associates of the therapist to help create an anxiety-provoking environment—eg, having a patient give an impromptu speech in front of an attractive associate of the opposite sex.

Where psychopharmacology fits in

While CBT is clearly a viable alternative to medication, psychopharmacology is sometimes indicated for anxiety or trauma-related disorders, depending on the diagnosis and on whether psychotherapy is ongoing.27 Evidence shows that specific types of drugs are effective for treating some anxiety-related disorders, while other medications may worsen symptoms (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of PD, while benzodiazepines are contraindicated for patients with PTSD).27-29 Other research has found that a combined approach (psychotherapy plus medication) can be effective for the treatment of some anxiety disorders, including OCD.30 Although the combination may initially assist patients in their efforts to manage troublesome symptoms, in some cases it may limit the gains made from CBT.31

Talking to patients about CBT

In discussing treatment options with patients with anxiety or trauma-related disorders (TABLE 3),2-4,10,12-14,32-34 it is important to note that psychotherapy—and particularly CBT—may be more cost-effective and have longerlasting effects than medication.32-34 Explain that it is a short-term treatment (typically lasting 9 to 12 weeks) but has been found to have long-term results.2-4,6,7 Point out, too, that patients who engage in CBT are likely to learn new skills, some of which may last a lifetime—and do not have to worry about adverse effects or potential drug-drug interactions as they would if they opted for psychopharmacology instead.

Finally, tell patients that you have vetted the practitioners you refer patients to and that you will continue to see them while they undergo treatment to ensure that the CBT is progressing well and following the established protocol.

CASE › Ms. S’s primary care physician considers prescribing alprazolam, but is concerned because this anti-anxiety medication can be habit-forming. Noting that although the patient is already taking sertraline, her distress related to the trauma appears to be worsening, the doctor suggests Ms. S try CBT. He explains that CBT is time-limited but has been found to have substantial long-lasting benefits for women who, like her, have been victims of sexual assault. The physician also tells Ms. S that CBT follows a specific protocol that typically consists of 9 to 12 weekly sessions; includes homework assignments and often follows a manual; is goal-oriented and measurable; and focuses on changing present behavior, thoughts, and feelings.

When Ms. S agrees to a referral, her physician assures her that he has vetted the practitioner and asks her to come in after 12 weeks of CBT so he can monitor her progress.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott Coffey, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; scoffey@umc.edu

› Tell patients who are potential candidates for cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) that it has been demonstrated to be effective in treating anxiety and trauma-related disorders. A

› Motivate patients by pointing out that CBT is short-term therapy that is cost-effective and has the potential to be more beneficial than medication. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Darla S, a 42-year-old being treated for gastrointestinal (GI) distress, has undergone multiple tests over the course of the year, including a colonoscopy, an endoscopy, and a food allergy work-up. All had negative results. Medication trials—with proton pump inhibitors, H2 receptor antagonists, and prokinetics, among others—have not brought her any relief. The patient recently began taking sertraline 200 mg/d, which seemed to be helping. But on her latest visit, Ms. S requests a prescription for a sleeping pill. When asked what’s been keeping her up, the patient confides that she recently began having nightmares relating to a sexual assault that occurred several years ago.

If Ms. S were your patient, what would you recommend?

Family physicians (FPs) often encounter patients who are experiencing psychological distress, particularly anxiety.1 This may become evident when you’re treating one problem, such as low back pain or GI distress, but come to realize that anxiety is a key contributing factor or cause. Or you may discover that an anxiety or trauma-related disorder is complicating or interfering with treatment—preventing a patient with heart disease from quitting smoking, exercising regularly, or following a heart-healthy diet, for example.

Psychotropic medication is an option in such cases, of course. But the drugs often have adverse effects or interact with other medications the patient is taking, and their effects typically last only as long as the course of treatment. Being familiar with effective nonpharmacologic treatments—most notably, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)—will help you provide such patients with optimal care.

Advantages. CBT has several advantages that supportive counseling, traditional psychotherapy, and other nonpharmacologic treatments for psychological disorders do not: It is time-limited, typically lasting 9 to 12 weeks; skill-based; and goal-oriented. It also has a large amount of data to support it.2-4

Chances are you are familiar with the basic elements of CBT—challenging problematic beliefs, ensuring an increase in pleasant activities, and providing extended exposure to places or activities that trigger avoidance and/or arousal so that these responses are gradually diminished.2 However, there is not one single model of CBT. Rather, there are specific protocols for the conditions included in this review (TABLE 1).5

But before we get to the protocols, let’s first look at the evidence.

Meta-analyses demonstrate efficacy and effectiveness

Multiple studies and meta-analyses have consistently found CBT to reduce symptoms associated with anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Foremost among them are a metaanalysis by Hofmann and Smits6 of randomized placebo-controlled studies that assessed CBT’s efficacy and a meta-analysis by Stewart and Chambless7 that focused instead on effectiveness studies—ie, those assessing CBT in less-controlled, real-world practice. The findings are highlighted in TABLE 2.6,7

A 2012 review of meta-analyses of CBT8 for a broader range of psychological disorders found it to be more effective in treating generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), panic disorder (PD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and social anxiety disorder (SAD) than control conditions, such as placebo, and often more effective than other treatments. Notably, CBT was shown to be more effective than relaxation therapy for PD, more effective in the long term than psychopharmacology for SAD, and more effective than supportive counseling for PTSD.

Cognitive processing and exposure therapy for PTSD

Two types of CBT have been found to be particularly effective in treating PTSD: cognitive processing therapy and exposure therapy. Each has specific protocols, although treatment often has some components of each.9

Cognitive processing therapy, a firstline treatment for PTSD, was initially developed for the treatment of rape victims,10 but has been found to be effective in treating combat-related PTSD, as well.11 It incorporates the core elements of cognitive therapy—identifying false or unhelpful trauma-related thoughts, then evaluating the evidence for and against them so the patient learns to consider whether these problematic thoughts are the result of cognitive bias or error and develop more realistic and/or useful thoughts. Cognitive processing therapy, however, focuses primarily on issues of safety, danger, and trust relating to patients’ views of themselves, others, and the world. Patients are asked to write, and then read, a narrative of the trauma they endured to help them challenge troubling thoughts about it.10

A woman undergoing treatment for PTSD relating to a sexual assault, for example, may initially think, “All men are bad.” Challenging this thought by examining evidence for and against it may help her replace it with the more realistic belief that some—but not all—men are bad.

Exposure therapy, which is also a firstline treatment for PTSD,12-14 involves presenting the frightening stimuli to patients in a safe environment so that they can learn a new way of responding.9 If a patient is afraid of a specific location because she was assaulted there, for instance, slowly exposing her to the site while ensuring her safety can help her anxiety diminish. Depending on the circumstances, exposure may be conducted in vivo (tangible stimuli), achieved through mental imagery (of a combat zone where an improvised explosive device detonated, for example), or both.

Prolonged exposure has been shown to be very effective in treating PTSD resulting from a variety of traumatic events. Other aspects of treatment include education about the disorder and breathing retraining to reduce arousal and increase the patient’s ability to relax.15

Generalized anxiety disorder: Worry exposure and relaxation

CBT for GAD has 5 components:

- education about the disorder

- cognitive restructuring

- progressive muscle relaxation

- worry exposure

- in vivo exposure.

Relaxation training is a crucial part of treatment for GAD, perhaps more so than for other anxiety disorders.16 Cognitive restructuring is vital, as well. This involves the use of the Socratic means of questioning, asking “Tell me what you mean by ‘horrible,’” for example, and “What about that is of most concern to you?”

Worry exposure occurs by instructing the patient to engage in prolonged worry about one particular topic, rather than jumping from one worrisome subject to another. The single focus reduces the distress that worry causes, thereby decreasing the time spent worrying.17 As treatment progresses, the patient is taught to set aside a specific time to worry. Worrying outside of the designated “worry time” is not allowed.18,19

Panic disorder: Recognizing what's behind physical symptoms

Treatment for PD combines education about the disorder, cognitive restructuring, and exposure.

Education helps the patient understand the reason the increased arousal response occurs at seemingly random times—recognizing that he or she is interpreting normal physiological sensations negatively, for example, and that the physical response is the body’s way of protecting itself.

Cognitive restructuring helps patients reformulate their view of the relationship between physical symptoms and panic attacks. An individual might learn to interpret a rapid heart rate as an indication that his heart is working harder and getting stronger, for instance, rather than as a symptom of cardiovascular distress.

Interoceptive exposure therapy teaches patients to identify their internal physical cues (eg, shortness of breath, shakiness, and tachycardia) and then deliberately induce them—by breathing through a straw, climbing a flight of stairs, or spinning in a chair, for example. With repeated exposure, patients learn that the physical sensations are not dangerous, and the anxiety associated with them decreases.

In vivo exposure involves the creation of a “fear hierarchy” of places and activities that the patient avoids due to fear of having a panic attack, then gradually exposing him or her to them.18,20

Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Exposure and response

Exposure and response prevention (ERP) is the primary treatment for OCD. However, this seemingly straightforward behavioral treatment can be very challenging to implement because the compulsion that reduces a patient’s anxiety may be a mental act—silently repeating a number or phrase until the distress is released, for example—and thus unobservable.

Treatment consists of first helping the patient recognize his or her recurrent thoughts, behaviors, or mental acts, then identifying triggers for these compulsions. Next, the patient is gradually exposed to these triggers without being allowed to engage in the compulsive response that typically follows.21,22 For example, a clinician may have a patient obsessed with germs pick objects out of the trash during a therapy session but not allow hand washing afterwards or repeatedly write or say a number or word that normally elicits compulsive behavior but prevent the patient from engaging in it.

Social anxiety disorder: Group therapy

Group therapy, in which the group setting itself becomes a type of exposure, is a very effective treatment for SAD.23 This can be challenging, however, as patients with this disorder may be less likely to seek treatment if they know they will be put into a group. Individual treatment is another option for patients with SAD, and can be equally effective.24

Cognitive restructuring of anxiety-provoking thoughts (eg, “Everyone will think I’m stupid”) and exposure to social situations and cues that patients with this disorder typically avoid are other key components of treatment.25,26 Exposure often occurs outside of the therapy setting. Patients may be instructed to go to a cafeteria and have lunch alone without looking at their phone or reading a book, for instance, or to go to a coffee shop and strike up a conversation with someone of the opposite sex while in line. Exposures within the therapeutic setting may involve associates of the therapist to help create an anxiety-provoking environment—eg, having a patient give an impromptu speech in front of an attractive associate of the opposite sex.

Where psychopharmacology fits in

While CBT is clearly a viable alternative to medication, psychopharmacology is sometimes indicated for anxiety or trauma-related disorders, depending on the diagnosis and on whether psychotherapy is ongoing.27 Evidence shows that specific types of drugs are effective for treating some anxiety-related disorders, while other medications may worsen symptoms (eg, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have demonstrated effectiveness in the treatment of PD, while benzodiazepines are contraindicated for patients with PTSD).27-29 Other research has found that a combined approach (psychotherapy plus medication) can be effective for the treatment of some anxiety disorders, including OCD.30 Although the combination may initially assist patients in their efforts to manage troublesome symptoms, in some cases it may limit the gains made from CBT.31

Talking to patients about CBT

In discussing treatment options with patients with anxiety or trauma-related disorders (TABLE 3),2-4,10,12-14,32-34 it is important to note that psychotherapy—and particularly CBT—may be more cost-effective and have longerlasting effects than medication.32-34 Explain that it is a short-term treatment (typically lasting 9 to 12 weeks) but has been found to have long-term results.2-4,6,7 Point out, too, that patients who engage in CBT are likely to learn new skills, some of which may last a lifetime—and do not have to worry about adverse effects or potential drug-drug interactions as they would if they opted for psychopharmacology instead.

Finally, tell patients that you have vetted the practitioners you refer patients to and that you will continue to see them while they undergo treatment to ensure that the CBT is progressing well and following the established protocol.

CASE › Ms. S’s primary care physician considers prescribing alprazolam, but is concerned because this anti-anxiety medication can be habit-forming. Noting that although the patient is already taking sertraline, her distress related to the trauma appears to be worsening, the doctor suggests Ms. S try CBT. He explains that CBT is time-limited but has been found to have substantial long-lasting benefits for women who, like her, have been victims of sexual assault. The physician also tells Ms. S that CBT follows a specific protocol that typically consists of 9 to 12 weekly sessions; includes homework assignments and often follows a manual; is goal-oriented and measurable; and focuses on changing present behavior, thoughts, and feelings.

When Ms. S agrees to a referral, her physician assures her that he has vetted the practitioner and asks her to come in after 12 weeks of CBT so he can monitor her progress.

CORRESPONDENCE

Scott Coffey, PhD, Department of Psychiatry and Human Behavior, University of Mississippi Medical Center, 2500 North State Street, Jackson, MS 39216; scoffey@umc.edu

1. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317-325.

2. Beck JS. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Basics and Beyond. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

3. Dobson KS, ed. Handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002.

4. Hollon SD, Beck AT. Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In: Bergin AE, Garfield SL, eds. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1994:428-466.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:621-632.

7. Stewart RE, Chambless DL. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:595-606.

8. Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, et al. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Ther Res. 2012;36:427-440.

9. Cahill SP, Rothbaum BO, Resick PA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, et al, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009:139-222.

10. Resick PA, Schnicke M. Cognitive Processing Therapy for Rape Victims: A Treatment Manual. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993.

11. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, et al. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:898-907.

12. Bisson J, Andrew M. Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD003388.

13. Bisson JI, Ehlers A, Matthews R, et al. Psychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:97-104.

14. Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, et al. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:635-641.

15. Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO. Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences Therapist Guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

16. Borkovec T, Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive- behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:611-619.

17. Provencher MD, Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R. Efficacy of problemsolving training and cognitive exposure in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a case replication series. Cognitive Behav Pract. 2004;11:404-414.

18. Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Worry: Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

19. Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Worry: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

20. Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic: Therapist Guide. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

21. Foa EB, Yadin E, Lichner TK. Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

22. Yazdin E, Foa EB, Kuchner TK. Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

23. Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Hope DA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment: Description, case presentation, and empirical support. In: Stein MB, ed. Social Phobia: Clinical and Research Perspectives. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995:293-321.

24. Stangier U, Heidenreich T, Peitz M, et al. Cognitive therapy for social phobia: individual versus group treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:991-1007.

25. Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Turk CL. Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

26. Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Turk CL. Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach: Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

27. Ravindran LN, Stein MB. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders: a review of progress. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;7:839-854.

28. Bernardy NC. The role of benzodiazepines in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD Res Q. 2013;23:1-9.

29. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, et al, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

30. Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, et al. Randomized, placebocontrolled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:151-161.

31. Otto MW, Smits JAJ, Reese HE. Combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for mood and anxiety disorders in adults: Review and analysis. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract. 2005;12:72-86.

32. Antonuccio DO, Thomas M, Danton WG. A cost-effectiveness analysis of cognitive behavior therapy and fluoxetine (prozac) in the treatment of depression. Behav Ther. 1997;28:187-210.

33. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:2529-2536.

34. Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH, et al. Cognitive behavioral and pharmacological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1997;28:285-305.

1. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146:317-325.

2. Beck JS. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy: Basics and Beyond. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

3. Dobson KS, ed. Handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002.

4. Hollon SD, Beck AT. Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies. In: Bergin AE, Garfield SL, eds. Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change. 4th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 1994:428-466.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

6. Hofmann SG, Smits JA. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders: a meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:621-632.

7. Stewart RE, Chambless DL. Cognitive–behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders in clinical practice: a meta-analysis of effectiveness studies. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:595-606.

8. Hofmann SG, Asnaani A, Vonk IJ, et al. The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cognitive Ther Res. 2012;36:427-440.

9. Cahill SP, Rothbaum BO, Resick PA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for adults. In: Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, et al, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009:139-222.

10. Resick PA, Schnicke M. Cognitive Processing Therapy for Rape Victims: A Treatment Manual. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993.

11. Monson CM, Schnurr PP, Resick PA, et al. Cognitive processing therapy for veterans with military-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:898-907.

12. Bisson J, Andrew M. Psychological treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD003388.

13. Bisson JI, Ehlers A, Matthews R, et al. Psychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:97-104.

14. Powers MB, Halpern JM, Ferenschak MP, et al. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30:635-641.

15. Foa EB, Hembree EA, Rothbaum BO. Prolonged Exposure Therapy for PTSD: Emotional Processing of Traumatic Experiences Therapist Guide. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

16. Borkovec T, Costello E. Efficacy of applied relaxation and cognitive- behavioral therapy in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61:611-619.

17. Provencher MD, Dugas MJ, Ladouceur R. Efficacy of problemsolving training and cognitive exposure in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a case replication series. Cognitive Behav Pract. 2004;11:404-414.

18. Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Worry: Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

19. Zinbarg RE, Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Worry: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2006.

20. Craske MG, Barlow DH. Mastery of Your Anxiety and Panic: Therapist Guide. 4th ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007.

21. Foa EB, Yadin E, Lichner TK. Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

22. Yazdin E, Foa EB, Kuchner TK. Exposure and Response (Ritual) Prevention for Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2012.

23. Heimberg RG, Juster HR, Hope DA, et al. Cognitive-behavioral group treatment: Description, case presentation, and empirical support. In: Stein MB, ed. Social Phobia: Clinical and Research Perspectives. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1995:293-321.

24. Stangier U, Heidenreich T, Peitz M, et al. Cognitive therapy for social phobia: individual versus group treatment. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:991-1007.

25. Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Turk CL. Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach: Therapist Guide. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

26. Hope DA, Heimberg RG, Turk CL. Managing Social Anxiety: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Approach: Workbook. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

27. Ravindran LN, Stein MB. The pharmacologic treatment of anxiety disorders: a review of progress. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;7:839-854.

28. Bernardy NC. The role of benzodiazepines in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PTSD Res Q. 2013;23:1-9.

29. Foa EB, Keane TM, Friedman MJ, et al, eds. Effective Treatments for PTSD: Practice Guidelines from the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2009.

30. Foa EB, Liebowitz MR, Kozak MJ, et al. Randomized, placebocontrolled trial of exposure and ritual prevention, clomipramine, and their combination in the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:151-161.

31. Otto MW, Smits JAJ, Reese HE. Combined psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for mood and anxiety disorders in adults: Review and analysis. Clin Psychol: Sci Pract. 2005;12:72-86.

32. Antonuccio DO, Thomas M, Danton WG. A cost-effectiveness analysis of cognitive behavior therapy and fluoxetine (prozac) in the treatment of depression. Behav Ther. 1997;28:187-210.

33. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283:2529-2536.

34. Gould RA, Otto MW, Pollack MH, et al. Cognitive behavioral and pharmacological treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary meta-analysis. Behav Ther. 1997;28:285-305.