User login

Will open power morcellation of uterine tissue remain an option during hysterectomy and myomectomy?

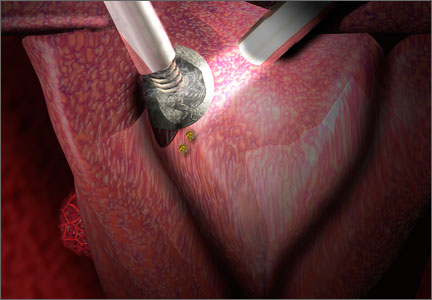

The use of power morcellation to remove the uterus or uterine tumors during hysterectomy and myomectomy has been in the limelight in 2014—particularly morcellation performed in an “open” fashion (without use of a protective bag). Concerns about the dispersion of tissue throughout the peritoneal cavity—including the risk of disseminating tissue from leiomyosarcoma, a rare but deadly cancer—have drawn statements from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the AAGL, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and others, cautioning against the use of open power morcellation in women with a known or suspected malignancy.

In February 2014, Robert L. Barbieri, MD, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, wrote about this concern for OBG Management in his capacity as editor in chief of the journal.

“When used to treat tumors presumed to be fibroids, open power morcellation is associated with an increased risk of dispersing benign myoma tissue and occult malignant leiomyosarcoma tissue throughout the abdominal cavity,” he wrote.1 “Dispersion of benign myoma tissue may result in the growth of fibroids on the peritoneal surface, omentum, and bowel, causing abdominal and pelvic pain and necessitating reoperation. Dispersion of leiomyosarcoma tissue throughout the abdominal cavity may result in a Stage I cancer being upstaged to a Stage IV malignancy, requiring additional surgery and chemotherapy. In cases in which open power morcellation causes the upstaging of a leiomyosarcoma, the death rate is increased.”1

Not surprisingly, the numerous statements and warnings since then have led to some confusion in the specialty about the safest course of action for tissue extraction during hysterectomy and myomectomy in women with a large uterus.

To explore the options more deeply and address the future of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in women’s health, OBG Management invited two experts to comment: Ray A. Wertheim, MD, Director of the AAGL Center of Excellence Minimally Invasive Gynecology Program at Inova Fair Oaks Hospital in Fairfax, Virginia, and Harry Reich, MD, widely known as the first surgeon to perform laparoscopic hysterectomy, among other achievements. Both Dr. Wertheim and Dr. Reich were members of the AAGL Tissue Extraction Task Force.

In this Q&A, Dr. Wertheim and Dr. Reich discuss:

- options for tissue extraction going forward

- the importance of continuing to offer minimally invasive surgical approaches to patients

- the need to educate surgeons about the safest approaches to tissue extraction.

Both surgeons believe that power morcellation should remain an option for selected cases, though neither performs the technique himself. Both surgeons also believe that minimally invasive approaches to hysterectomy and myomectomy are here to stay and should continue to be utilized whenever possible.

AAGL convened an impartial expert panel

OBG Management: Dr. Wertheim, could you tell us a little about the AAGL position statement on the use of power morcellation for uterine tissue extraction at hysterectomy or myomectomy, since you were on the task force that researched and wrote it?2 How does it compare with the ACOG and FDA statements on the use of power morcellation?

Dr. Wertheim: AAGL convened its task force to conduct a critical appraisal of the existing evidence related to the practice of uterine extraction in the setting of hysterectomy and myomectomy. Areas in need of further investigation also were identified.

The task force consisted of experts who had no conflicts, were not allowed to discuss or review findings with anyone, and were not reimbursed for their time. I’ve been practicing for almost 40 years in academic and private settings, and I found this group to be the brightest, most caring and compassionate group with whom I’ve ever worked. Our review is the most complete report to date, more comprehensive than the reports from the FDA, ACOG, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), and the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS).

Interestingly, AAGL, ACOG, SGO, and AUGS all reached the same conclusion: All existing methods of tissue extraction have benefits and risks that must be balanced.

OBG Management: How did the AAGL task force assess the evidence?

Dr. Wertheim: The quality of evidence and strength of recommendations were assessed using US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines. One of the problems we encountered was that there are very few good data on the issue of power morcellation for uterine tissue extraction, especially in regard to leiomyosarcoma. One needs to be careful making recommendations without good data.

At this time, we do not believe there is a single method of tissue extraction that can protect all patients. Therefore, all current methods should remain available. We believe that an understanding of the issues will allow surgeons, hospitals, and patients to make the appropriate informed choices regarding tissue extraction in individual patients undergoing uterine surgery.

How to manage tissue extraction going forward

OBG Management: The FDA will convene another meeting on power morcellation July 10 and 11. Regardless of its final decision, what should the gynecologic specialty be doing to avoid disseminating uterine tissue in the peritoneal cavity, particularly leiomyosarcoma?

Dr. Wertheim: Yes, AAGL will be at the FDA’s July hearing because we are the experts. MIS is a wonderful advancement in women’s health care. All surgical specialties are moving toward MIS. Our challenge is to perform it as safely as possible, given the current data and instrumentation available.

In regard to leiomyosarcoma, because we lack the ability to accurately make the diagnosis preoperatively, we’ve identified risk factors that should be taken into consideration. Risk factors include advanced age, history of radiation or tamoxifen use, black race, hereditary leiomyomatosis, renal cell carcinoma syndrome, and survival of childhood retinoblastoma.

At this time, we have specimen-retrieval bags that can be used with power morcellation. However, it takes skill to be able to place a large specimen inside a bag without injuring surrounding organs due to limited visibility.

OBG Management: How should we go about educating surgeons about MIS alternatives to open power morcellation?

Education, at the hospital and national level, is in the works

Dr. Wertheim: In my hospital, we are mentoring surgeons to help them gain the new skills needed. In addition, Dr. Reich and I, along with Albert Steren, MD, a minimally invasive surgeon from Rockville, Maryland, are hosting an educational dinner meeting on tissue extraction on July 24 in northern Virginia. I plan to give a grand rounds presentation on tissue extraction for hospitals in northern Virginia and also would like to offer a course in the near future. I’m also hoping that we’ll be able to offer courses around the country before the annual AAGL meeting this November, since this is such a pressing issue.

At the annual AAGL meeting, the subject will be discussed at length, with an emphasis on identifying risk factors and conducting appropriate preoperative testing, with workshops likely to teach the skills needed to perform these surgeries as safely as possible.

Why a return to reliance on laparotomy would be unwise

OBG Management: Given all the concerns expressed recently about open power morcellation, do you think some surgeons will revert to abdominal hysterectomy rather than rely on MIS? Would such a move be safer than power morcellation?

Dr. Wertheim: That would be a disaster for women. Very reliable data have shown that MIS is safer than open surgery, with much quicker recovery. Almost all of my patients are discharged within 3 hours after surgery, and most no longer require pain medications other than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) by postoperative day 2. They’re usually back to work within 2 weeks.

We have worked long and hard to develop skills and instrumentation required to perform MIS safely—but nothing replaces good judgment. In some cases, laparotomy or conversion to a laparotomy may be indicated.

New instrumentation is needed and is being developed. In the meantime, my personal bias is to rule out risk factors for malignancy and continue to morcellate with a scalpel, preferably inside a bag. After all, we know that with open power morcellation, fragments and cells are usually left behind regardless of inspection and irrigation. These fragments may cause leiomyomatosis, endometriosis, bowel obstruction, sepsis, and possible dissemination of tumor fragments. Moreover, morcellation into small fragments complicates the pathologist’s ability to give an accurate report. The use of open power morcellation also subjects the patient to a risk of damage to surrounding organs—usually due to the surgeon’s inexperience.

As I have said before, our challenge is to perform these surgeries using the safest techniques possible, given the current data and instrumentation.

OBG Management: Dr. Reich, you have a unique perspective on this issue, since you pioneered laparoscopic hysterectomy. How has uterine tissue extraction evolved since then? Do you think open power morcellation should remain an option?

Dr. Reich: Uterine tissue extraction has not evolved. The terms “laparoscopic hysterectomy” and “total laparoscopic hysterectomy” imply vaginal extraction using a scalpel, not abdominal extraction using a morcellator. Unfortunately there is no substitute for hard work using a #10 blade on a long handle and special vaginal retraction tools.

In 1983, I made a decision to stop performing laparotomy for all gynecologic procedures, including hysterectomy, myomectomy, urology, oncology, abscesses, extensive adhesions, and rectovaginal endometriosis. I was an accomplished vaginal surgeon at that time, as well as a one-handed laparoscopic surgeon, operating while looking through the scope with one eye.

Interest in a laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy began with my presentations about laparoscopic hysterectomy in January 1988. At that time I had over 10 years of experience doing what is now called laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy.

I wrote extensively about specimen removal using a scalpel before electronic power morcellators were available. Since then, I have asked those using power morcellators to stop calling their operation a laparoscopic hysterectomy, as it has more in common with an abdominal-extraction hysterectomy.

I have never advocated removing the uterus using power morcellators, and I still believe that most specimens can be removed vaginally without the spray of pieces of the specimen around the peritoneal cavity that occurs with power morcellation. This goes for hysterectomy involving a large uterus, myomectomy through a culdotomy incision, and removal of the uterine fundus after supracervical hysterectomy. (It is irresponsible to use expensive power morcellation to remove small supracervical hysterectomy specimens.) It is time to get back to learning and teaching vaginal morcellation, although I readily admit it is time consuming.

Nevertheless, I believe power morcellation should remain an option. Recent laparoscopic fellowship trainees know only this technique, which is still better than a return to mutilation by laparotomy.

Gynecology is a frustrating profession—30 years of MIS as a sideshow. General surgery has rapidly adopted a laparoscopic approach to most operations, after gynecologists taught them. Today the majority of gynecologists do not do advanced laparoscopic surgery and would love to get back to open incision laparotomy for their operations. We cannot go back.

OBG Management: Dr. Wertheim and Dr. Reich, do your personal views of the morcellation issue differ at all from the official views of professional societies?

Dr. Wertheim: Yes. However, before I share them, I’d like to emphasize that the views I’m about to express are mine and mine only, not those of the AAGL or its task force.

The issue of uterine extraction is a highly emotional and political issue, about which there are few good data.

Abundant Level 1 data strongly support a vaginal or laparoscopic approach for benign hysterectomy when possible. ACOG and AAGL have issued position papers supporting these approaches for benign hysterectomies. Gynecologic surgeons and other surgical specialists have embraced MIS because it is safer, offers faster recovery, produces less postoperative pain, and has fewer complications than open surgery. However, AAGL has maintained for several years that morcellation is contraindicated in cases where uterine malignancy is either known or suspected.

The dilemma with open power morcellation is that even with our best diagnostic tools, the rare uterine sarcoma cannot always be definitively ruled out preoperatively. Endometrial cancer usually can be diagnosed before surgery. However, rare subtypes such as sarcomas are more difficult to reliably diagnose preoperatively, and risk factors for uterine sarcomas are not nearly as well understood as those for endometrial cancer.

I do agree with the FDA’s cautionary statement, which pointedly prohibits power morcellation for women with suspected precancer or known cancer of the gynecologic organs.3 However, the AAGL task force critically reviewed about 120 articles, including the studies assessed by the FDA. Concerns arose regarding the FDA’s interpretation of the data. Due to a number of deficiencies in these studies, some of the conclusions of the FDA may not be completely accurate. The studies analyzed by the FDA were not stratified by risk factors for sarcoma and were not necessarily performed in a setting of reproductive-aged women with presumed fibroids.

Dr. Reich: Here are my personal views about the sarcoma problem and I am sure they differ from the official views of the professional societies:

- Laparoscopic hysterectomy should always mean vaginal extraction unless a less disfiguring site can be discovered; power morcellation implies minilaparotomy and should be renamed to reflect that fact.

- Power morcellation must be differentiated from vaginal and minilaparotomy scalpel morcellation, especially in the media. Vaginal hysterectomy has entailed vaginal scalpel morcellation with successful outcomes for more than 100 years.

- Remember that most gynecologic cancers are approached using the laparoscope today. This certainly includes cervical and endometrial cancer and some ovarian cancers. (For example, one of my neighbors is a 25-year survivor of laparoscopically treated bilateral ovarian cancer who refused laparotomy!)

- I have removed sarcomas by vaginal morcellation during laparoscopic hysterectomy and laparoscopic myomectomy with no late sequelae. In fact, most cervical cancer surgery is done by laparoscopic surgery today. And even an open laparotomy hysterectomy can spread a sarcoma.

- The current morcellation debate arose when a single case of disseminated leiomyosarcoma became highly publicized. It involved a prominent physician whose leiomyosarcoma was unknown to her initial surgeon, and the malignancy was upstaged after the use of power morcellation during hysterectomy. After this case was covered in the media, other cases began to be reported in the lay press as well, some of which predated the publicized case. The truth is, regrettably, that sarcomas carry poor prognoses even when specimens are removed intact. And we don’t know much about the sarcoma that started this debate. Was it mild or aggressive? How many mitotic figures were there per high-powered field? And what was found macroscopically and microscopically at the subsequent laparotomy? We on the AAGL task force do not know the answers to these questions, although at least some of these variables are reported in other published cases. And because this case is likely to have a powerful effect on MIS in our country and the rest of the world, it is my opinion that we need to know these details.

What is your preferred surgical approach?

OBG Management: Do you perform open power morcellation in selected patients?

Dr. Wertheim: Even though I have performed morcellation with a scalpel transvaginally or through a mini-laparotomy incision for many years, I have never used open power morcellation because of the risk of leaving behind benign or malignant tissue fragments. Morcellation with a scalpel is easily learned and can be performed as quickly as power morcellation. Morcellation with a scalpel produces much larger pieces than with power morcellation. This probably markedly decreases the loss of fragments. I cannot make a definitive statement regarding cell loss, however. Until we have improved instrumentation and are better able to make a preoperative diagnosis of sarcoma, I’m going to rule out risk factors identified by the AAGL task force, do the appropriate work-up, and continue to morcellate with a scalpel, placing the specimen in a bag, if technically possible.

Dr. Reich: As I mentioned, I am a vaginal scalpel morcellator. I tried power morcellation when it first was developed but was never a fan. The same techniques used for vaginal extraction using a coring maneuver can be used abdominally through the umbilicus or a 1- or 2-cm trocar site.

What should the FDA’s next move be?

OBG Management: Care to make any predictions about the FDA’s final decision?

Dr. Wertheim: This has become a highly emotional and controversial issue with little good existing data. During the preoperative visit, this issue should be discussed with the patient using clear, lay-friendly language. Having said that, I also do not believe we should hide behind informed consent. The FDA has a responsibility to keep the public safe. If open power morcellation is allowed to continue, there will be another morcellated sarcoma or complications from retained benign tissue fragments. I doubt the FDA can live with this. I believe the risk factors identified by the AAGL task force should be ruled out, the appropriate workup done and then, if power morcellation is performed, it should be done inside a bag. In addition, I think the FDA should require that complications be reported and recorded in a registry.

Dr. Reich: I disagree. The FDA has to back off. It’s important to note that this is an American problem, as the rest of the world cannot afford power morcellators. The data are not in yet. The decision about what kind of hysterectomy is performed will be made by the “informed” patient, who undoubtedly will be very afraid to have MIS because of the surrounding negative publicity. We must do a better job of promoting the advantages of a minimally invasive approach.

OBG Management: Thank you both for your time and expertise.

Dr. Wertheim: Thank you for giving us the opportunity to express our opinions regarding this highly emotional and controversial issue.

Tell us what you think!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about this or other current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Share your thoughts by sending a letter to obg@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

1. Barbieri RL. Benefits and pitfalls of open power morcellation of uterine fibroids. OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):10–15.

2. The Tissue Extraction Task Force, AAGL. AAGL Position Statement: Morcellation During Uterine Tissue Extraction. http://www.aagl.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Tissue_Extraction_TFR.pdf. Accessed June 13, 014.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic Uterine Power Morcellation in Hysterectomy and Myomectomy. FDA Safety Communication. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm393576.htm. Published April 17, 2014. Accessed June 13, 2014.

The use of power morcellation to remove the uterus or uterine tumors during hysterectomy and myomectomy has been in the limelight in 2014—particularly morcellation performed in an “open” fashion (without use of a protective bag). Concerns about the dispersion of tissue throughout the peritoneal cavity—including the risk of disseminating tissue from leiomyosarcoma, a rare but deadly cancer—have drawn statements from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the AAGL, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and others, cautioning against the use of open power morcellation in women with a known or suspected malignancy.

In February 2014, Robert L. Barbieri, MD, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, wrote about this concern for OBG Management in his capacity as editor in chief of the journal.

“When used to treat tumors presumed to be fibroids, open power morcellation is associated with an increased risk of dispersing benign myoma tissue and occult malignant leiomyosarcoma tissue throughout the abdominal cavity,” he wrote.1 “Dispersion of benign myoma tissue may result in the growth of fibroids on the peritoneal surface, omentum, and bowel, causing abdominal and pelvic pain and necessitating reoperation. Dispersion of leiomyosarcoma tissue throughout the abdominal cavity may result in a Stage I cancer being upstaged to a Stage IV malignancy, requiring additional surgery and chemotherapy. In cases in which open power morcellation causes the upstaging of a leiomyosarcoma, the death rate is increased.”1

Not surprisingly, the numerous statements and warnings since then have led to some confusion in the specialty about the safest course of action for tissue extraction during hysterectomy and myomectomy in women with a large uterus.

To explore the options more deeply and address the future of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in women’s health, OBG Management invited two experts to comment: Ray A. Wertheim, MD, Director of the AAGL Center of Excellence Minimally Invasive Gynecology Program at Inova Fair Oaks Hospital in Fairfax, Virginia, and Harry Reich, MD, widely known as the first surgeon to perform laparoscopic hysterectomy, among other achievements. Both Dr. Wertheim and Dr. Reich were members of the AAGL Tissue Extraction Task Force.

In this Q&A, Dr. Wertheim and Dr. Reich discuss:

- options for tissue extraction going forward

- the importance of continuing to offer minimally invasive surgical approaches to patients

- the need to educate surgeons about the safest approaches to tissue extraction.

Both surgeons believe that power morcellation should remain an option for selected cases, though neither performs the technique himself. Both surgeons also believe that minimally invasive approaches to hysterectomy and myomectomy are here to stay and should continue to be utilized whenever possible.

AAGL convened an impartial expert panel

OBG Management: Dr. Wertheim, could you tell us a little about the AAGL position statement on the use of power morcellation for uterine tissue extraction at hysterectomy or myomectomy, since you were on the task force that researched and wrote it?2 How does it compare with the ACOG and FDA statements on the use of power morcellation?

Dr. Wertheim: AAGL convened its task force to conduct a critical appraisal of the existing evidence related to the practice of uterine extraction in the setting of hysterectomy and myomectomy. Areas in need of further investigation also were identified.

The task force consisted of experts who had no conflicts, were not allowed to discuss or review findings with anyone, and were not reimbursed for their time. I’ve been practicing for almost 40 years in academic and private settings, and I found this group to be the brightest, most caring and compassionate group with whom I’ve ever worked. Our review is the most complete report to date, more comprehensive than the reports from the FDA, ACOG, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), and the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS).

Interestingly, AAGL, ACOG, SGO, and AUGS all reached the same conclusion: All existing methods of tissue extraction have benefits and risks that must be balanced.

OBG Management: How did the AAGL task force assess the evidence?

Dr. Wertheim: The quality of evidence and strength of recommendations were assessed using US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines. One of the problems we encountered was that there are very few good data on the issue of power morcellation for uterine tissue extraction, especially in regard to leiomyosarcoma. One needs to be careful making recommendations without good data.

At this time, we do not believe there is a single method of tissue extraction that can protect all patients. Therefore, all current methods should remain available. We believe that an understanding of the issues will allow surgeons, hospitals, and patients to make the appropriate informed choices regarding tissue extraction in individual patients undergoing uterine surgery.

How to manage tissue extraction going forward

OBG Management: The FDA will convene another meeting on power morcellation July 10 and 11. Regardless of its final decision, what should the gynecologic specialty be doing to avoid disseminating uterine tissue in the peritoneal cavity, particularly leiomyosarcoma?

Dr. Wertheim: Yes, AAGL will be at the FDA’s July hearing because we are the experts. MIS is a wonderful advancement in women’s health care. All surgical specialties are moving toward MIS. Our challenge is to perform it as safely as possible, given the current data and instrumentation available.

In regard to leiomyosarcoma, because we lack the ability to accurately make the diagnosis preoperatively, we’ve identified risk factors that should be taken into consideration. Risk factors include advanced age, history of radiation or tamoxifen use, black race, hereditary leiomyomatosis, renal cell carcinoma syndrome, and survival of childhood retinoblastoma.

At this time, we have specimen-retrieval bags that can be used with power morcellation. However, it takes skill to be able to place a large specimen inside a bag without injuring surrounding organs due to limited visibility.

OBG Management: How should we go about educating surgeons about MIS alternatives to open power morcellation?

Education, at the hospital and national level, is in the works

Dr. Wertheim: In my hospital, we are mentoring surgeons to help them gain the new skills needed. In addition, Dr. Reich and I, along with Albert Steren, MD, a minimally invasive surgeon from Rockville, Maryland, are hosting an educational dinner meeting on tissue extraction on July 24 in northern Virginia. I plan to give a grand rounds presentation on tissue extraction for hospitals in northern Virginia and also would like to offer a course in the near future. I’m also hoping that we’ll be able to offer courses around the country before the annual AAGL meeting this November, since this is such a pressing issue.

At the annual AAGL meeting, the subject will be discussed at length, with an emphasis on identifying risk factors and conducting appropriate preoperative testing, with workshops likely to teach the skills needed to perform these surgeries as safely as possible.

Why a return to reliance on laparotomy would be unwise

OBG Management: Given all the concerns expressed recently about open power morcellation, do you think some surgeons will revert to abdominal hysterectomy rather than rely on MIS? Would such a move be safer than power morcellation?

Dr. Wertheim: That would be a disaster for women. Very reliable data have shown that MIS is safer than open surgery, with much quicker recovery. Almost all of my patients are discharged within 3 hours after surgery, and most no longer require pain medications other than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) by postoperative day 2. They’re usually back to work within 2 weeks.

We have worked long and hard to develop skills and instrumentation required to perform MIS safely—but nothing replaces good judgment. In some cases, laparotomy or conversion to a laparotomy may be indicated.

New instrumentation is needed and is being developed. In the meantime, my personal bias is to rule out risk factors for malignancy and continue to morcellate with a scalpel, preferably inside a bag. After all, we know that with open power morcellation, fragments and cells are usually left behind regardless of inspection and irrigation. These fragments may cause leiomyomatosis, endometriosis, bowel obstruction, sepsis, and possible dissemination of tumor fragments. Moreover, morcellation into small fragments complicates the pathologist’s ability to give an accurate report. The use of open power morcellation also subjects the patient to a risk of damage to surrounding organs—usually due to the surgeon’s inexperience.

As I have said before, our challenge is to perform these surgeries using the safest techniques possible, given the current data and instrumentation.

OBG Management: Dr. Reich, you have a unique perspective on this issue, since you pioneered laparoscopic hysterectomy. How has uterine tissue extraction evolved since then? Do you think open power morcellation should remain an option?

Dr. Reich: Uterine tissue extraction has not evolved. The terms “laparoscopic hysterectomy” and “total laparoscopic hysterectomy” imply vaginal extraction using a scalpel, not abdominal extraction using a morcellator. Unfortunately there is no substitute for hard work using a #10 blade on a long handle and special vaginal retraction tools.

In 1983, I made a decision to stop performing laparotomy for all gynecologic procedures, including hysterectomy, myomectomy, urology, oncology, abscesses, extensive adhesions, and rectovaginal endometriosis. I was an accomplished vaginal surgeon at that time, as well as a one-handed laparoscopic surgeon, operating while looking through the scope with one eye.

Interest in a laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy began with my presentations about laparoscopic hysterectomy in January 1988. At that time I had over 10 years of experience doing what is now called laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy.

I wrote extensively about specimen removal using a scalpel before electronic power morcellators were available. Since then, I have asked those using power morcellators to stop calling their operation a laparoscopic hysterectomy, as it has more in common with an abdominal-extraction hysterectomy.

I have never advocated removing the uterus using power morcellators, and I still believe that most specimens can be removed vaginally without the spray of pieces of the specimen around the peritoneal cavity that occurs with power morcellation. This goes for hysterectomy involving a large uterus, myomectomy through a culdotomy incision, and removal of the uterine fundus after supracervical hysterectomy. (It is irresponsible to use expensive power morcellation to remove small supracervical hysterectomy specimens.) It is time to get back to learning and teaching vaginal morcellation, although I readily admit it is time consuming.

Nevertheless, I believe power morcellation should remain an option. Recent laparoscopic fellowship trainees know only this technique, which is still better than a return to mutilation by laparotomy.

Gynecology is a frustrating profession—30 years of MIS as a sideshow. General surgery has rapidly adopted a laparoscopic approach to most operations, after gynecologists taught them. Today the majority of gynecologists do not do advanced laparoscopic surgery and would love to get back to open incision laparotomy for their operations. We cannot go back.

OBG Management: Dr. Wertheim and Dr. Reich, do your personal views of the morcellation issue differ at all from the official views of professional societies?

Dr. Wertheim: Yes. However, before I share them, I’d like to emphasize that the views I’m about to express are mine and mine only, not those of the AAGL or its task force.

The issue of uterine extraction is a highly emotional and political issue, about which there are few good data.

Abundant Level 1 data strongly support a vaginal or laparoscopic approach for benign hysterectomy when possible. ACOG and AAGL have issued position papers supporting these approaches for benign hysterectomies. Gynecologic surgeons and other surgical specialists have embraced MIS because it is safer, offers faster recovery, produces less postoperative pain, and has fewer complications than open surgery. However, AAGL has maintained for several years that morcellation is contraindicated in cases where uterine malignancy is either known or suspected.

The dilemma with open power morcellation is that even with our best diagnostic tools, the rare uterine sarcoma cannot always be definitively ruled out preoperatively. Endometrial cancer usually can be diagnosed before surgery. However, rare subtypes such as sarcomas are more difficult to reliably diagnose preoperatively, and risk factors for uterine sarcomas are not nearly as well understood as those for endometrial cancer.

I do agree with the FDA’s cautionary statement, which pointedly prohibits power morcellation for women with suspected precancer or known cancer of the gynecologic organs.3 However, the AAGL task force critically reviewed about 120 articles, including the studies assessed by the FDA. Concerns arose regarding the FDA’s interpretation of the data. Due to a number of deficiencies in these studies, some of the conclusions of the FDA may not be completely accurate. The studies analyzed by the FDA were not stratified by risk factors for sarcoma and were not necessarily performed in a setting of reproductive-aged women with presumed fibroids.

Dr. Reich: Here are my personal views about the sarcoma problem and I am sure they differ from the official views of the professional societies:

- Laparoscopic hysterectomy should always mean vaginal extraction unless a less disfiguring site can be discovered; power morcellation implies minilaparotomy and should be renamed to reflect that fact.

- Power morcellation must be differentiated from vaginal and minilaparotomy scalpel morcellation, especially in the media. Vaginal hysterectomy has entailed vaginal scalpel morcellation with successful outcomes for more than 100 years.

- Remember that most gynecologic cancers are approached using the laparoscope today. This certainly includes cervical and endometrial cancer and some ovarian cancers. (For example, one of my neighbors is a 25-year survivor of laparoscopically treated bilateral ovarian cancer who refused laparotomy!)

- I have removed sarcomas by vaginal morcellation during laparoscopic hysterectomy and laparoscopic myomectomy with no late sequelae. In fact, most cervical cancer surgery is done by laparoscopic surgery today. And even an open laparotomy hysterectomy can spread a sarcoma.

- The current morcellation debate arose when a single case of disseminated leiomyosarcoma became highly publicized. It involved a prominent physician whose leiomyosarcoma was unknown to her initial surgeon, and the malignancy was upstaged after the use of power morcellation during hysterectomy. After this case was covered in the media, other cases began to be reported in the lay press as well, some of which predated the publicized case. The truth is, regrettably, that sarcomas carry poor prognoses even when specimens are removed intact. And we don’t know much about the sarcoma that started this debate. Was it mild or aggressive? How many mitotic figures were there per high-powered field? And what was found macroscopically and microscopically at the subsequent laparotomy? We on the AAGL task force do not know the answers to these questions, although at least some of these variables are reported in other published cases. And because this case is likely to have a powerful effect on MIS in our country and the rest of the world, it is my opinion that we need to know these details.

What is your preferred surgical approach?

OBG Management: Do you perform open power morcellation in selected patients?

Dr. Wertheim: Even though I have performed morcellation with a scalpel transvaginally or through a mini-laparotomy incision for many years, I have never used open power morcellation because of the risk of leaving behind benign or malignant tissue fragments. Morcellation with a scalpel is easily learned and can be performed as quickly as power morcellation. Morcellation with a scalpel produces much larger pieces than with power morcellation. This probably markedly decreases the loss of fragments. I cannot make a definitive statement regarding cell loss, however. Until we have improved instrumentation and are better able to make a preoperative diagnosis of sarcoma, I’m going to rule out risk factors identified by the AAGL task force, do the appropriate work-up, and continue to morcellate with a scalpel, placing the specimen in a bag, if technically possible.

Dr. Reich: As I mentioned, I am a vaginal scalpel morcellator. I tried power morcellation when it first was developed but was never a fan. The same techniques used for vaginal extraction using a coring maneuver can be used abdominally through the umbilicus or a 1- or 2-cm trocar site.

What should the FDA’s next move be?

OBG Management: Care to make any predictions about the FDA’s final decision?

Dr. Wertheim: This has become a highly emotional and controversial issue with little good existing data. During the preoperative visit, this issue should be discussed with the patient using clear, lay-friendly language. Having said that, I also do not believe we should hide behind informed consent. The FDA has a responsibility to keep the public safe. If open power morcellation is allowed to continue, there will be another morcellated sarcoma or complications from retained benign tissue fragments. I doubt the FDA can live with this. I believe the risk factors identified by the AAGL task force should be ruled out, the appropriate workup done and then, if power morcellation is performed, it should be done inside a bag. In addition, I think the FDA should require that complications be reported and recorded in a registry.

Dr. Reich: I disagree. The FDA has to back off. It’s important to note that this is an American problem, as the rest of the world cannot afford power morcellators. The data are not in yet. The decision about what kind of hysterectomy is performed will be made by the “informed” patient, who undoubtedly will be very afraid to have MIS because of the surrounding negative publicity. We must do a better job of promoting the advantages of a minimally invasive approach.

OBG Management: Thank you both for your time and expertise.

Dr. Wertheim: Thank you for giving us the opportunity to express our opinions regarding this highly emotional and controversial issue.

Tell us what you think!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about this or other current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Share your thoughts by sending a letter to obg@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

The use of power morcellation to remove the uterus or uterine tumors during hysterectomy and myomectomy has been in the limelight in 2014—particularly morcellation performed in an “open” fashion (without use of a protective bag). Concerns about the dispersion of tissue throughout the peritoneal cavity—including the risk of disseminating tissue from leiomyosarcoma, a rare but deadly cancer—have drawn statements from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the AAGL, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and others, cautioning against the use of open power morcellation in women with a known or suspected malignancy.

In February 2014, Robert L. Barbieri, MD, chair of obstetrics and gynecology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, wrote about this concern for OBG Management in his capacity as editor in chief of the journal.

“When used to treat tumors presumed to be fibroids, open power morcellation is associated with an increased risk of dispersing benign myoma tissue and occult malignant leiomyosarcoma tissue throughout the abdominal cavity,” he wrote.1 “Dispersion of benign myoma tissue may result in the growth of fibroids on the peritoneal surface, omentum, and bowel, causing abdominal and pelvic pain and necessitating reoperation. Dispersion of leiomyosarcoma tissue throughout the abdominal cavity may result in a Stage I cancer being upstaged to a Stage IV malignancy, requiring additional surgery and chemotherapy. In cases in which open power morcellation causes the upstaging of a leiomyosarcoma, the death rate is increased.”1

Not surprisingly, the numerous statements and warnings since then have led to some confusion in the specialty about the safest course of action for tissue extraction during hysterectomy and myomectomy in women with a large uterus.

To explore the options more deeply and address the future of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) in women’s health, OBG Management invited two experts to comment: Ray A. Wertheim, MD, Director of the AAGL Center of Excellence Minimally Invasive Gynecology Program at Inova Fair Oaks Hospital in Fairfax, Virginia, and Harry Reich, MD, widely known as the first surgeon to perform laparoscopic hysterectomy, among other achievements. Both Dr. Wertheim and Dr. Reich were members of the AAGL Tissue Extraction Task Force.

In this Q&A, Dr. Wertheim and Dr. Reich discuss:

- options for tissue extraction going forward

- the importance of continuing to offer minimally invasive surgical approaches to patients

- the need to educate surgeons about the safest approaches to tissue extraction.

Both surgeons believe that power morcellation should remain an option for selected cases, though neither performs the technique himself. Both surgeons also believe that minimally invasive approaches to hysterectomy and myomectomy are here to stay and should continue to be utilized whenever possible.

AAGL convened an impartial expert panel

OBG Management: Dr. Wertheim, could you tell us a little about the AAGL position statement on the use of power morcellation for uterine tissue extraction at hysterectomy or myomectomy, since you were on the task force that researched and wrote it?2 How does it compare with the ACOG and FDA statements on the use of power morcellation?

Dr. Wertheim: AAGL convened its task force to conduct a critical appraisal of the existing evidence related to the practice of uterine extraction in the setting of hysterectomy and myomectomy. Areas in need of further investigation also were identified.

The task force consisted of experts who had no conflicts, were not allowed to discuss or review findings with anyone, and were not reimbursed for their time. I’ve been practicing for almost 40 years in academic and private settings, and I found this group to be the brightest, most caring and compassionate group with whom I’ve ever worked. Our review is the most complete report to date, more comprehensive than the reports from the FDA, ACOG, the Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO), and the American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS).

Interestingly, AAGL, ACOG, SGO, and AUGS all reached the same conclusion: All existing methods of tissue extraction have benefits and risks that must be balanced.

OBG Management: How did the AAGL task force assess the evidence?

Dr. Wertheim: The quality of evidence and strength of recommendations were assessed using US Preventive Services Task Force guidelines. One of the problems we encountered was that there are very few good data on the issue of power morcellation for uterine tissue extraction, especially in regard to leiomyosarcoma. One needs to be careful making recommendations without good data.

At this time, we do not believe there is a single method of tissue extraction that can protect all patients. Therefore, all current methods should remain available. We believe that an understanding of the issues will allow surgeons, hospitals, and patients to make the appropriate informed choices regarding tissue extraction in individual patients undergoing uterine surgery.

How to manage tissue extraction going forward

OBG Management: The FDA will convene another meeting on power morcellation July 10 and 11. Regardless of its final decision, what should the gynecologic specialty be doing to avoid disseminating uterine tissue in the peritoneal cavity, particularly leiomyosarcoma?

Dr. Wertheim: Yes, AAGL will be at the FDA’s July hearing because we are the experts. MIS is a wonderful advancement in women’s health care. All surgical specialties are moving toward MIS. Our challenge is to perform it as safely as possible, given the current data and instrumentation available.

In regard to leiomyosarcoma, because we lack the ability to accurately make the diagnosis preoperatively, we’ve identified risk factors that should be taken into consideration. Risk factors include advanced age, history of radiation or tamoxifen use, black race, hereditary leiomyomatosis, renal cell carcinoma syndrome, and survival of childhood retinoblastoma.

At this time, we have specimen-retrieval bags that can be used with power morcellation. However, it takes skill to be able to place a large specimen inside a bag without injuring surrounding organs due to limited visibility.

OBG Management: How should we go about educating surgeons about MIS alternatives to open power morcellation?

Education, at the hospital and national level, is in the works

Dr. Wertheim: In my hospital, we are mentoring surgeons to help them gain the new skills needed. In addition, Dr. Reich and I, along with Albert Steren, MD, a minimally invasive surgeon from Rockville, Maryland, are hosting an educational dinner meeting on tissue extraction on July 24 in northern Virginia. I plan to give a grand rounds presentation on tissue extraction for hospitals in northern Virginia and also would like to offer a course in the near future. I’m also hoping that we’ll be able to offer courses around the country before the annual AAGL meeting this November, since this is such a pressing issue.

At the annual AAGL meeting, the subject will be discussed at length, with an emphasis on identifying risk factors and conducting appropriate preoperative testing, with workshops likely to teach the skills needed to perform these surgeries as safely as possible.

Why a return to reliance on laparotomy would be unwise

OBG Management: Given all the concerns expressed recently about open power morcellation, do you think some surgeons will revert to abdominal hysterectomy rather than rely on MIS? Would such a move be safer than power morcellation?

Dr. Wertheim: That would be a disaster for women. Very reliable data have shown that MIS is safer than open surgery, with much quicker recovery. Almost all of my patients are discharged within 3 hours after surgery, and most no longer require pain medications other than nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) by postoperative day 2. They’re usually back to work within 2 weeks.

We have worked long and hard to develop skills and instrumentation required to perform MIS safely—but nothing replaces good judgment. In some cases, laparotomy or conversion to a laparotomy may be indicated.

New instrumentation is needed and is being developed. In the meantime, my personal bias is to rule out risk factors for malignancy and continue to morcellate with a scalpel, preferably inside a bag. After all, we know that with open power morcellation, fragments and cells are usually left behind regardless of inspection and irrigation. These fragments may cause leiomyomatosis, endometriosis, bowel obstruction, sepsis, and possible dissemination of tumor fragments. Moreover, morcellation into small fragments complicates the pathologist’s ability to give an accurate report. The use of open power morcellation also subjects the patient to a risk of damage to surrounding organs—usually due to the surgeon’s inexperience.

As I have said before, our challenge is to perform these surgeries using the safest techniques possible, given the current data and instrumentation.

OBG Management: Dr. Reich, you have a unique perspective on this issue, since you pioneered laparoscopic hysterectomy. How has uterine tissue extraction evolved since then? Do you think open power morcellation should remain an option?

Dr. Reich: Uterine tissue extraction has not evolved. The terms “laparoscopic hysterectomy” and “total laparoscopic hysterectomy” imply vaginal extraction using a scalpel, not abdominal extraction using a morcellator. Unfortunately there is no substitute for hard work using a #10 blade on a long handle and special vaginal retraction tools.

In 1983, I made a decision to stop performing laparotomy for all gynecologic procedures, including hysterectomy, myomectomy, urology, oncology, abscesses, extensive adhesions, and rectovaginal endometriosis. I was an accomplished vaginal surgeon at that time, as well as a one-handed laparoscopic surgeon, operating while looking through the scope with one eye.

Interest in a laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy began with my presentations about laparoscopic hysterectomy in January 1988. At that time I had over 10 years of experience doing what is now called laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy.

I wrote extensively about specimen removal using a scalpel before electronic power morcellators were available. Since then, I have asked those using power morcellators to stop calling their operation a laparoscopic hysterectomy, as it has more in common with an abdominal-extraction hysterectomy.

I have never advocated removing the uterus using power morcellators, and I still believe that most specimens can be removed vaginally without the spray of pieces of the specimen around the peritoneal cavity that occurs with power morcellation. This goes for hysterectomy involving a large uterus, myomectomy through a culdotomy incision, and removal of the uterine fundus after supracervical hysterectomy. (It is irresponsible to use expensive power morcellation to remove small supracervical hysterectomy specimens.) It is time to get back to learning and teaching vaginal morcellation, although I readily admit it is time consuming.

Nevertheless, I believe power morcellation should remain an option. Recent laparoscopic fellowship trainees know only this technique, which is still better than a return to mutilation by laparotomy.

Gynecology is a frustrating profession—30 years of MIS as a sideshow. General surgery has rapidly adopted a laparoscopic approach to most operations, after gynecologists taught them. Today the majority of gynecologists do not do advanced laparoscopic surgery and would love to get back to open incision laparotomy for their operations. We cannot go back.

OBG Management: Dr. Wertheim and Dr. Reich, do your personal views of the morcellation issue differ at all from the official views of professional societies?

Dr. Wertheim: Yes. However, before I share them, I’d like to emphasize that the views I’m about to express are mine and mine only, not those of the AAGL or its task force.

The issue of uterine extraction is a highly emotional and political issue, about which there are few good data.

Abundant Level 1 data strongly support a vaginal or laparoscopic approach for benign hysterectomy when possible. ACOG and AAGL have issued position papers supporting these approaches for benign hysterectomies. Gynecologic surgeons and other surgical specialists have embraced MIS because it is safer, offers faster recovery, produces less postoperative pain, and has fewer complications than open surgery. However, AAGL has maintained for several years that morcellation is contraindicated in cases where uterine malignancy is either known or suspected.

The dilemma with open power morcellation is that even with our best diagnostic tools, the rare uterine sarcoma cannot always be definitively ruled out preoperatively. Endometrial cancer usually can be diagnosed before surgery. However, rare subtypes such as sarcomas are more difficult to reliably diagnose preoperatively, and risk factors for uterine sarcomas are not nearly as well understood as those for endometrial cancer.

I do agree with the FDA’s cautionary statement, which pointedly prohibits power morcellation for women with suspected precancer or known cancer of the gynecologic organs.3 However, the AAGL task force critically reviewed about 120 articles, including the studies assessed by the FDA. Concerns arose regarding the FDA’s interpretation of the data. Due to a number of deficiencies in these studies, some of the conclusions of the FDA may not be completely accurate. The studies analyzed by the FDA were not stratified by risk factors for sarcoma and were not necessarily performed in a setting of reproductive-aged women with presumed fibroids.

Dr. Reich: Here are my personal views about the sarcoma problem and I am sure they differ from the official views of the professional societies:

- Laparoscopic hysterectomy should always mean vaginal extraction unless a less disfiguring site can be discovered; power morcellation implies minilaparotomy and should be renamed to reflect that fact.

- Power morcellation must be differentiated from vaginal and minilaparotomy scalpel morcellation, especially in the media. Vaginal hysterectomy has entailed vaginal scalpel morcellation with successful outcomes for more than 100 years.

- Remember that most gynecologic cancers are approached using the laparoscope today. This certainly includes cervical and endometrial cancer and some ovarian cancers. (For example, one of my neighbors is a 25-year survivor of laparoscopically treated bilateral ovarian cancer who refused laparotomy!)

- I have removed sarcomas by vaginal morcellation during laparoscopic hysterectomy and laparoscopic myomectomy with no late sequelae. In fact, most cervical cancer surgery is done by laparoscopic surgery today. And even an open laparotomy hysterectomy can spread a sarcoma.

- The current morcellation debate arose when a single case of disseminated leiomyosarcoma became highly publicized. It involved a prominent physician whose leiomyosarcoma was unknown to her initial surgeon, and the malignancy was upstaged after the use of power morcellation during hysterectomy. After this case was covered in the media, other cases began to be reported in the lay press as well, some of which predated the publicized case. The truth is, regrettably, that sarcomas carry poor prognoses even when specimens are removed intact. And we don’t know much about the sarcoma that started this debate. Was it mild or aggressive? How many mitotic figures were there per high-powered field? And what was found macroscopically and microscopically at the subsequent laparotomy? We on the AAGL task force do not know the answers to these questions, although at least some of these variables are reported in other published cases. And because this case is likely to have a powerful effect on MIS in our country and the rest of the world, it is my opinion that we need to know these details.

What is your preferred surgical approach?

OBG Management: Do you perform open power morcellation in selected patients?

Dr. Wertheim: Even though I have performed morcellation with a scalpel transvaginally or through a mini-laparotomy incision for many years, I have never used open power morcellation because of the risk of leaving behind benign or malignant tissue fragments. Morcellation with a scalpel is easily learned and can be performed as quickly as power morcellation. Morcellation with a scalpel produces much larger pieces than with power morcellation. This probably markedly decreases the loss of fragments. I cannot make a definitive statement regarding cell loss, however. Until we have improved instrumentation and are better able to make a preoperative diagnosis of sarcoma, I’m going to rule out risk factors identified by the AAGL task force, do the appropriate work-up, and continue to morcellate with a scalpel, placing the specimen in a bag, if technically possible.

Dr. Reich: As I mentioned, I am a vaginal scalpel morcellator. I tried power morcellation when it first was developed but was never a fan. The same techniques used for vaginal extraction using a coring maneuver can be used abdominally through the umbilicus or a 1- or 2-cm trocar site.

What should the FDA’s next move be?

OBG Management: Care to make any predictions about the FDA’s final decision?

Dr. Wertheim: This has become a highly emotional and controversial issue with little good existing data. During the preoperative visit, this issue should be discussed with the patient using clear, lay-friendly language. Having said that, I also do not believe we should hide behind informed consent. The FDA has a responsibility to keep the public safe. If open power morcellation is allowed to continue, there will be another morcellated sarcoma or complications from retained benign tissue fragments. I doubt the FDA can live with this. I believe the risk factors identified by the AAGL task force should be ruled out, the appropriate workup done and then, if power morcellation is performed, it should be done inside a bag. In addition, I think the FDA should require that complications be reported and recorded in a registry.

Dr. Reich: I disagree. The FDA has to back off. It’s important to note that this is an American problem, as the rest of the world cannot afford power morcellators. The data are not in yet. The decision about what kind of hysterectomy is performed will be made by the “informed” patient, who undoubtedly will be very afraid to have MIS because of the surrounding negative publicity. We must do a better job of promoting the advantages of a minimally invasive approach.

OBG Management: Thank you both for your time and expertise.

Dr. Wertheim: Thank you for giving us the opportunity to express our opinions regarding this highly emotional and controversial issue.

Tell us what you think!

Drop us a line and let us know what you think about this or other current articles, which topics you'd like to see covered in future issues, and what challenges you face in daily practice. Share your thoughts by sending a letter to obg@frontlinemedcom.com. Please include the city and state in which you practice. Stay in touch! Your feedback is important to us!

1. Barbieri RL. Benefits and pitfalls of open power morcellation of uterine fibroids. OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):10–15.

2. The Tissue Extraction Task Force, AAGL. AAGL Position Statement: Morcellation During Uterine Tissue Extraction. http://www.aagl.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Tissue_Extraction_TFR.pdf. Accessed June 13, 014.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic Uterine Power Morcellation in Hysterectomy and Myomectomy. FDA Safety Communication. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm393576.htm. Published April 17, 2014. Accessed June 13, 2014.

1. Barbieri RL. Benefits and pitfalls of open power morcellation of uterine fibroids. OBG Manag. 2014;26(2):10–15.

2. The Tissue Extraction Task Force, AAGL. AAGL Position Statement: Morcellation During Uterine Tissue Extraction. http://www.aagl.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/Tissue_Extraction_TFR.pdf. Accessed June 13, 014.

3. US Food and Drug Administration. Laparoscopic Uterine Power Morcellation in Hysterectomy and Myomectomy. FDA Safety Communication. http://www.fda.gov/medicaldevices/safety/alertsandnotices/ucm393576.htm. Published April 17, 2014. Accessed June 13, 2014.

Visit the Morcellation Topic Collection Page for additional articles, videos, and audiocasts.

Perspective: Specialty Needs to Re-Examine Approach to Endometriosis Surgery

Endometriosis experts diagnose endometriosis by excision biopsy of suspected lesions, but a reluctance to biopsy by many ob.gyns., who make the diagnosis visually by laparoscopy, means a distortion of results. A diagnosis of endometriosis should require a positive excisional biopsy documenting endometrial glands/stroma at laparoscopy.

Papers in the literature using visual documentation of endometriosis are worthless. Yes, I am saying that most papers on the medical and/or surgical treatment of endometriosis without biopsy are worthless. Many women with a clinical or visual diagnosis of endometriosis without biopsy do not have endometriosis; they are more likely being treated for “hemosiderin-laden macrophages,” the normal product of retrograde menstruation.

In most cases of severe endometriosis, the endometriosis – surrounded by scar tissue – can be palpated in the office using a simple rectovaginal examination. These areas are usually very tender to palpation, and this tenderness is used to direct the surgeon to the area to be removed. Postoperative examination (3-6 months after surgery) should be pain free if the appropriate area was excised.

Unfortunately, many women who undergo multiple “endometriosis” laparoscopies actually have minimal disease. Surgeons will typically perform diagnostic laparoscopy without biopsy followed by 6 months of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist treatment followed by another “diagnostic” laparoscopy. This is what I call “cashectomy” – extracting cash from the patient without any long-term benefit because the disease remains. The concept that endometriosis comes back is often a good excuse for poor treatment. What is called recurrent disease is really persistent disease that was never treated in the first place.

If this paints a depressing picture about the state of endometriosis diagnosis and treatment in the United States, believe me, it should. But surgeons alone are not to blame. The lawyers and the managed care insurance system have contributed. I was able to surgically treat extensive endometriosis over the past 30 years only because I did not participate within the managed care insurance system.

Over time, two distinct groups of laparoscopic surgeons have evolved: a very large cluster doing it for diagnosis and minimal treatment and a much smaller elite segment doing it for optimum treatment.

Here’s a brief summary of my surgical approach. Many women with extensive endometriosis have had multiple abdominal incision laparotomies that result in adhesions of small bowel stuck to the undersurface of the anterior abdominal wall. Thus, the first part of many endometriosis operations is to release small-bowel adhesions from the anterior abdominal wall to see the pelvic organs. The next step is to separate all pelvic organs including the ovaries, uterus, cervix, upper vagina, and rectum. The last step is to excise the endometriosis.

Symptomatic endometriosis is surrounded by fibrotic scar tissue from the repetitive longstanding inflammatory response. This scar tissue containing the endometriotic glands is excised from inside the ovaries, the posterior cervix and vagina, the rectum, and the uterosacral ligaments (and ureters if necessary). Rectal resection, discoid or complete, is done if the endometriosis penetrates the rectal and/or rectosigmoid wall. I use 2,000 cc of Ringer’s lactate to separate the operated-upon organs during early healing. I do not use GnRH agonists.

There are no fewer than 37 CPT codes to report a hysterectomy. But there are no codes to report an extensive endometriosis operation like the one I just described.

Most operations to effectively excise extensive deep fibrotic endometriosis take 3-4 hours. But the poor reimbursement available for complex endometriosis surgery and the high legal risk means that few gynecologists will want to acquire the skills to perform these operations. Instead, many in our profession consider it acceptable to diagnose endometriosis without biopsy proof and then perform laparoscopy with minimal treatment of the deep lesions. This should no longer be acceptable to our patients.

We need to develop proper guidelines for endometriosis diagnosis and treatment. Medical treatment cure rates are near zero, regardless of disease stage, and act mainly to suppress endometrial gland and stroma activity. Extensive endometriosis surgery, often involving excising rectal lesions, is the most difficult surgery a gynecologist encounters, more difficult than cancer surgery in most cases. But endometriosis is not cancer. It is a chronic inflammatory response to hormonally activated cells with resultant fibromuscular encapsulation.

I believe that the development of endometriosis subspecialty centers with gynecologic surgeons trained to excise bowel, bladder, and ureteral lesions is long past due in this country.

Dr. Reich, who performed the first laparoscopic hysterectomy, is a past president of both the International Society of Gynecologic Endoscopists and the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. He is currently an adviser to the Endometriosis Foundation of America. Dr. Reich has a financial interest in Apple Medical, which developed a trocar. E-mail him at obnews@elsevier.com.

Body text goes here

Body text goes here

Body text goes here

Endometriosis experts diagnose endometriosis by excision biopsy of suspected lesions, but a reluctance to biopsy by many ob.gyns., who make the diagnosis visually by laparoscopy, means a distortion of results. A diagnosis of endometriosis should require a positive excisional biopsy documenting endometrial glands/stroma at laparoscopy.

Papers in the literature using visual documentation of endometriosis are worthless. Yes, I am saying that most papers on the medical and/or surgical treatment of endometriosis without biopsy are worthless. Many women with a clinical or visual diagnosis of endometriosis without biopsy do not have endometriosis; they are more likely being treated for “hemosiderin-laden macrophages,” the normal product of retrograde menstruation.

In most cases of severe endometriosis, the endometriosis – surrounded by scar tissue – can be palpated in the office using a simple rectovaginal examination. These areas are usually very tender to palpation, and this tenderness is used to direct the surgeon to the area to be removed. Postoperative examination (3-6 months after surgery) should be pain free if the appropriate area was excised.

Unfortunately, many women who undergo multiple “endometriosis” laparoscopies actually have minimal disease. Surgeons will typically perform diagnostic laparoscopy without biopsy followed by 6 months of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist treatment followed by another “diagnostic” laparoscopy. This is what I call “cashectomy” – extracting cash from the patient without any long-term benefit because the disease remains. The concept that endometriosis comes back is often a good excuse for poor treatment. What is called recurrent disease is really persistent disease that was never treated in the first place.

If this paints a depressing picture about the state of endometriosis diagnosis and treatment in the United States, believe me, it should. But surgeons alone are not to blame. The lawyers and the managed care insurance system have contributed. I was able to surgically treat extensive endometriosis over the past 30 years only because I did not participate within the managed care insurance system.

Over time, two distinct groups of laparoscopic surgeons have evolved: a very large cluster doing it for diagnosis and minimal treatment and a much smaller elite segment doing it for optimum treatment.

Here’s a brief summary of my surgical approach. Many women with extensive endometriosis have had multiple abdominal incision laparotomies that result in adhesions of small bowel stuck to the undersurface of the anterior abdominal wall. Thus, the first part of many endometriosis operations is to release small-bowel adhesions from the anterior abdominal wall to see the pelvic organs. The next step is to separate all pelvic organs including the ovaries, uterus, cervix, upper vagina, and rectum. The last step is to excise the endometriosis.

Symptomatic endometriosis is surrounded by fibrotic scar tissue from the repetitive longstanding inflammatory response. This scar tissue containing the endometriotic glands is excised from inside the ovaries, the posterior cervix and vagina, the rectum, and the uterosacral ligaments (and ureters if necessary). Rectal resection, discoid or complete, is done if the endometriosis penetrates the rectal and/or rectosigmoid wall. I use 2,000 cc of Ringer’s lactate to separate the operated-upon organs during early healing. I do not use GnRH agonists.

There are no fewer than 37 CPT codes to report a hysterectomy. But there are no codes to report an extensive endometriosis operation like the one I just described.

Most operations to effectively excise extensive deep fibrotic endometriosis take 3-4 hours. But the poor reimbursement available for complex endometriosis surgery and the high legal risk means that few gynecologists will want to acquire the skills to perform these operations. Instead, many in our profession consider it acceptable to diagnose endometriosis without biopsy proof and then perform laparoscopy with minimal treatment of the deep lesions. This should no longer be acceptable to our patients.

We need to develop proper guidelines for endometriosis diagnosis and treatment. Medical treatment cure rates are near zero, regardless of disease stage, and act mainly to suppress endometrial gland and stroma activity. Extensive endometriosis surgery, often involving excising rectal lesions, is the most difficult surgery a gynecologist encounters, more difficult than cancer surgery in most cases. But endometriosis is not cancer. It is a chronic inflammatory response to hormonally activated cells with resultant fibromuscular encapsulation.

I believe that the development of endometriosis subspecialty centers with gynecologic surgeons trained to excise bowel, bladder, and ureteral lesions is long past due in this country.

Dr. Reich, who performed the first laparoscopic hysterectomy, is a past president of both the International Society of Gynecologic Endoscopists and the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. He is currently an adviser to the Endometriosis Foundation of America. Dr. Reich has a financial interest in Apple Medical, which developed a trocar. E-mail him at obnews@elsevier.com.

Endometriosis experts diagnose endometriosis by excision biopsy of suspected lesions, but a reluctance to biopsy by many ob.gyns., who make the diagnosis visually by laparoscopy, means a distortion of results. A diagnosis of endometriosis should require a positive excisional biopsy documenting endometrial glands/stroma at laparoscopy.

Papers in the literature using visual documentation of endometriosis are worthless. Yes, I am saying that most papers on the medical and/or surgical treatment of endometriosis without biopsy are worthless. Many women with a clinical or visual diagnosis of endometriosis without biopsy do not have endometriosis; they are more likely being treated for “hemosiderin-laden macrophages,” the normal product of retrograde menstruation.

In most cases of severe endometriosis, the endometriosis – surrounded by scar tissue – can be palpated in the office using a simple rectovaginal examination. These areas are usually very tender to palpation, and this tenderness is used to direct the surgeon to the area to be removed. Postoperative examination (3-6 months after surgery) should be pain free if the appropriate area was excised.

Unfortunately, many women who undergo multiple “endometriosis” laparoscopies actually have minimal disease. Surgeons will typically perform diagnostic laparoscopy without biopsy followed by 6 months of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist treatment followed by another “diagnostic” laparoscopy. This is what I call “cashectomy” – extracting cash from the patient without any long-term benefit because the disease remains. The concept that endometriosis comes back is often a good excuse for poor treatment. What is called recurrent disease is really persistent disease that was never treated in the first place.

If this paints a depressing picture about the state of endometriosis diagnosis and treatment in the United States, believe me, it should. But surgeons alone are not to blame. The lawyers and the managed care insurance system have contributed. I was able to surgically treat extensive endometriosis over the past 30 years only because I did not participate within the managed care insurance system.

Over time, two distinct groups of laparoscopic surgeons have evolved: a very large cluster doing it for diagnosis and minimal treatment and a much smaller elite segment doing it for optimum treatment.

Here’s a brief summary of my surgical approach. Many women with extensive endometriosis have had multiple abdominal incision laparotomies that result in adhesions of small bowel stuck to the undersurface of the anterior abdominal wall. Thus, the first part of many endometriosis operations is to release small-bowel adhesions from the anterior abdominal wall to see the pelvic organs. The next step is to separate all pelvic organs including the ovaries, uterus, cervix, upper vagina, and rectum. The last step is to excise the endometriosis.

Symptomatic endometriosis is surrounded by fibrotic scar tissue from the repetitive longstanding inflammatory response. This scar tissue containing the endometriotic glands is excised from inside the ovaries, the posterior cervix and vagina, the rectum, and the uterosacral ligaments (and ureters if necessary). Rectal resection, discoid or complete, is done if the endometriosis penetrates the rectal and/or rectosigmoid wall. I use 2,000 cc of Ringer’s lactate to separate the operated-upon organs during early healing. I do not use GnRH agonists.

There are no fewer than 37 CPT codes to report a hysterectomy. But there are no codes to report an extensive endometriosis operation like the one I just described.

Most operations to effectively excise extensive deep fibrotic endometriosis take 3-4 hours. But the poor reimbursement available for complex endometriosis surgery and the high legal risk means that few gynecologists will want to acquire the skills to perform these operations. Instead, many in our profession consider it acceptable to diagnose endometriosis without biopsy proof and then perform laparoscopy with minimal treatment of the deep lesions. This should no longer be acceptable to our patients.

We need to develop proper guidelines for endometriosis diagnosis and treatment. Medical treatment cure rates are near zero, regardless of disease stage, and act mainly to suppress endometrial gland and stroma activity. Extensive endometriosis surgery, often involving excising rectal lesions, is the most difficult surgery a gynecologist encounters, more difficult than cancer surgery in most cases. But endometriosis is not cancer. It is a chronic inflammatory response to hormonally activated cells with resultant fibromuscular encapsulation.

I believe that the development of endometriosis subspecialty centers with gynecologic surgeons trained to excise bowel, bladder, and ureteral lesions is long past due in this country.

Dr. Reich, who performed the first laparoscopic hysterectomy, is a past president of both the International Society of Gynecologic Endoscopists and the Society of Laparoendoscopic Surgeons. He is currently an adviser to the Endometriosis Foundation of America. Dr. Reich has a financial interest in Apple Medical, which developed a trocar. E-mail him at obnews@elsevier.com.

Major Finding: Text.

Data Source: Text.

Disclosures: Text.

Vessel-sealing reduces operative time, loss of blood

Objective

To compare blood loss and procedure time for vaginal hysterectomy using electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing versus sutures.

Results

Compared with sutures, vessel-sealing technology resulted in a 27% reduction in operative time and a 47% reduction in blood loss.

Methods

Sixty women scheduled to undergo vaginal hysterectomy in a single surgical practice were randomized to electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing or sutures for hemostasis.

Procedure time was measured from the initial mucosal injection to closure of the vaginal cuff with satisfactory hemostasis.

Blood loss was estimated by the anesthesia service.

The study was sponsored by Valleylab (Boulder, Colo), the manufacturer of the electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealer (LigaSure) used in the trial; both investigators had financial ties to the company.

Outcome

Mean procedure time was 39.1 minutes (range 22–93) for electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing and 53.6 minutes (range 37–160) for sutures.

Mean estimated blood loss was 68.9 mL (range 20–200) for electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing and 126.7 mL (range 25–600) for sutures.

Complication rates and length of stay did not differ by technique.

Expert Commentary

It took many years for the concept of bipolar desiccation for large vessel hemostasis to be accepted after I introduced the idea at the 1985 meeting of the American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists. The Kleppinger bipolar forceps I used (Richard Wolf, Rosemont, Ill) were developed for laparoscopic tubal sterilization. Bipolar desiccation for oophorectomy was considered too dangerous to be published in 1985-86; only a brief abstract of this presentation is in the medical literature.1

Since the 1988 introduction of laparoscopic hysterectomy using bipolar vessel sealing, bipolar desiccation has prevailed and has become the standard over later techniques, such as staples and sutures.2-4

High percentage of outpatient procedures. This study is remarkable not only because electrosurgical bipolar vessel sealing achieved a 27% reduction in operative time and a 47% reduction in blood loss, but also because 78% of the cases were outpatient.

I am pleased to see that bipolar techniques for vaginal hysterectomy are being so rapidly accepted (over 100 cases have been done at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, with minimal problems). This acceptance—coupled with the use of laparoscopic hysterectomy—should make abdominal hysterectomy a rare event in the future.