User login

Physician assistants in psychiatry: Helping to meet America’s mental health needs

“Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased, pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow, raze out the written troubles of the brain, and with some sweet oblivious antidote cleanse the stuffed bosom of that perilous stuff which weighs upon the heart?”

– William Shakespeare, Macbeth

For many years, the United States has been experiencing a shortage of psychiatrists. Currently, there are only 28,000 to 33,000 psychiatrists in active patient care practice in the United States.1,2 The lack of psychiatrists is pronounced in many areas of the country, including rural regions, some urban neighborhoods, and community health centers. In approximately half of US counties, there are no psychiatrists at all.3

While patients with mental illnesses often are treated in primary care settings, the need for qualified mental health clinicians remains acute. Two-thirds of primary care physicians report difficulty in referring patients for mental health care, due to the shortage of clinicians and long wait times for patients to be seen.4 In the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the shortage of qualified psychiatrists is even more acute, due to ongoing combat operations and an increased number of missions and manpower requirements to complete them, which also has increased veterans’ mental health needs during life after their service.5

The outlook for providing adequate numbers of psychiatrists in the future is even more concerning. Based on a population analysis, Satiani et al6 predicts an extreme shortage of psychiatrists for the next 30 years, with the availability of psychiatrists per population expected to reach an all-time low by 2024. Based on ratios from the Department of Health and Human Services, this would mean a shortage of 14,000 to 31,000 psychiatrists over the next 5 to 6 years alone. This is due primarily to the expected retirement of more than 25,000 psychiatrists age >55 during the next 5 years. With mental illness becoming the costliest medical condition in the United States, at $201 billion annually, the potential impact of this shortage is alarming.6

Addressing the shortage

Efforts aimed at increasing the number of psychiatrists, improving access to care, and improving efficiency of care have focused on expanding recruitment and training capacity in psychiatry residency programs, utilizing new models such as telepsychiatry and Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams, increasing the number of Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics, and embedding psychiatrists in large primary care practices.7 Another avenue for addressing the psychiatrist shortage has been the training and hiring of more advanced practice clinicians, including physician assistants (PAs) and

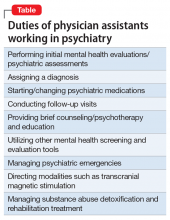

Physician assistants and NPs make up the largest group of non-physician mental health professionals who can prescribe medications. Physician assistant training is most closely aligned with the allopathic training model of physicians.9 Some typical duties of PAs working in a psychiatric setting are outlined in the Table.

How many PAs elect to specialize in psychiatry, compared with the percentage of physicians who choose psychiatry as a career? Data from the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) revealed that in 2018 there were 1,470 PAs working in psychiatry, or approximately 1.5% of all PAs in practice.10 In comparison, approximately 5% of physicians complete residency training in psychiatry.2

Continue to: Although the need for more...

Although the need for more mental health professionals—especially those who can prescribe—is well documented, PA practice in psychiatry has been underrepresented, with PAs choosing to work in the field at a rate just over one-fourth that of physicians. While there is no clear explanation for the lack of PAs in psychiatry, PA programs’ training model has been to produce generalist clinicians who can work in numerous settings, particularly primary care. However, during the past several decades, PA practice choice has shifted largely from primary care to specialty care. In 1974, an estimated 68.8% of PAs worked in primary care settings (family medicine/general practice, general internal medicine, and general pediatrics), while the remainder worked in specialty areas.11 In contrast, by 2018, only 25.8% of PAs worked in primary care settings.10 Despite more PAs choosing to work in medical specialties, the number choosing psychiatry remains very low. With the great need for well-trained mental health prescribers, the opportunity for growth in this area of medicine and increased salary incentive should serve as an impetus for PAs to consider psychiatry. Like their physician counterparts, PAs working in specialty areas of medicine tend to be paid more, sometimes substantially more.12

Training requirements

What is the level of training and experience for PAs who choose to work in psychiatry? Physician assistant program applicants generally come from a pre-med background with a Bachelor’s degree in a hard science, and often have medical experience as a nurse, paramedic, emergency medical technician, or other health profession. Physician assistants are trained in the same medical model of care as physicians, although their training is structured over an average 27-month cycle, with 1 year devoted to didactic education and 1 year or more devoted to clinical training.13 They are qualified to “go to work” soon after graduating and passing the NCCPA Physician Assistant National Certifying Examination (PANCE), and may require a state license. Upon graduation, PAs have received approximately 1,000 hours of didactic and 2,000 hours of clinical training across the general spectrum of medicine.

Physician assistants who choose to specialize in psychiatry may complete a residency/fellowship in psychiatry of approximately 1 year, and/or obtain the Certificate of Added Qualification (CAQ) in psychiatry from the NCCPA. Most PAs who work in psychiatry have done so through “on-the-job” training, where their knowledge and skills have expanded through working with their supervising physician(s) and gaining experience from their clinical practice and self-study. For many years, there were only 1 or 2 PA residency/fellowship opportunities in psychiatry in the United States for PAs wanting to acquire additional formal didactic and clinical knowledge and skills in psychiatry. Fortunately, there has been a growing number of PA residencies/fellowships in psychiatry. These programs are typically 1 year in length and can provide a PA who wants to specialize in psychiatry with an additional 300 to >500 didactic and 1,500 to 2,000 clinical hours of training in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of the spectrum of psychiatric conditions. Currently, there are 10 to 12 programs in the United States that offer this training to PAs, producing approximately 18 to 20 residency-trained psychiatric PAs each year. Almost one-half of PAs who are residency-trained in psychiatry are being trained in VA facilities and affiliated institutions sponsored by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Along with the PA’s basic education, the additional knowledge and skills acquired in residency prepare the PA to be a highly capable psychiatric clinician, with a combined 1,500 didactic and 4,000 clinical hours of training in general medicine plus psychiatry. The addition of the CAQ demonstrates the PA’s commitment to additional learning in psychiatry, as the added work experience requirements, the additional postgraduate continuing medical education requirements in psychiatry, and the psychiatry board exam clearly show dedication to a higher level of knowledge and skill in the specialty.

Because PAs have been trained as generalists who are able to work in any setting or specialty, they have a broad range of knowledge in medicine and surgery. This can be especially helpful when working in a psychiatric practice, where they can provide an added medical focus to patient care when needed. As more PAs are choosing to work in a specialty area for much or all of their practice, they are able to gain significant knowledge and skills in that specialty.

Getting more PAs into psychiatry

So what does the future hold for PAs in psychiatry? The increased need and opportunity in mental health will likely draw a higher percentage of PAs to this specialty. Hopefully, an increase in the number of PA psychiatry residencies or advanced mental health training opportunities, and the continued goal of obtaining the CAQ in psychiatry, will serve to increase the number of psychiatric PAs.14

Continue to: The NCCPA has also recognized...

The NCCPA has also recognized the importance of increasing PA knowledge and integration in mental health care by establishing a PArtners in Mental Health Steering Committee, composed of leaders from the largest PA organizations, including the American Academy of Physician Assistants, the Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant, the Physician Assistant Education Association, the Physician Assistant Foundation, and other PA and interprofessional members. The NCCPA’s PArtners in Mental Health Initiative: Stakeholders Report 2018 outlines an ongoing strategy to increase PA engagement in and awareness of mental health among the PA community and future providers via outreach to member organizations, state societies, PA programs, and those at the state and national level who legislate and reimburse PA services for mental health care.15 The Steering Committee’s recommendations include:

- enhancing PA educational approaches in mental health

- strengthening the PA practice environment to address mental health needs and foster integration

- promoting national campaigns to raise the profile of PAs addressing mental health across disciplines

- creating an organizational structure that incorporates current participants, offers backbone support to this movement, and plans for communication and financing.16

The role of PA educators

In the end, PA leaders and educators will play a substantial role in influencing future PAs to seek a career in psychiatry. Currently, psychiatry education varies among PA programs. Some offer robust didactic and clinical education and training, while other programs are limited in the number of hours of psychiatric didactic education, and may offer psychiatry clinical opportunities only in the context of a primary care setting, rather than in a dedicated psychiatric setting. Additionally, the mission of training PAs for generalist, primary care practice may limit many PAs from considering psychiatry because they do not necessarily view psychiatry as closely aligning with primary care generalist practice the way cardiology, pulmonology, gastroenterology, or other internal medicine specialties do.

In terms of PA postgraduate education, many PAs have completed residencies in surgical specialties or emergency medicine. Coincidentally, surgery and emergency medicine residencies are the most prolific of the postgraduate residency programs, adding a significant number of well-trained PAs to these specialties. The NCCPA also offers the CAQ for Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, Orthopedic Surgery, and Emergency Medicine, which may attract PAs into these specialties, with or without completing a residency.

Because the NCCPA also offers the CAQ in Psychiatry, it would be reasonable and attractive for PAs who complete a psychiatry residency to obtain this certification. In fact, the PA psychiatry residency at our own institution trains our residents to be fully prepared and board-eligible to take the CAQ in Psychiatry upon completing residency. To date, every PA residency graduate who has completed our program and taken the CAQ in Psychiatry exam has passed and been awarded the CAQ in Psychiatry. They have proven themselves to the program and the NCCPA, and have impressed their employers with their clinical abilities and medical knowledge.

For psychiatrists, the addition of a well-trained or willing-to-be-trained PA to the practice can provide an economic advantage and strong team partnership that ensures optimal care for patients in this time of shortage of skilled mental health clinicians. The need is clear and will continue. Physician assistant educators must provide adequate didactic and clinical training in psychiatry to PA students, and support students interested in pursuing a career path in this specialty. Physician assistant organizations must meet the challenge of increasing the number of PAs in psychiatry, and encourage the establishment of additional post-graduate residency programs in psychiatry for PAs. Lastly, more PAs need to be made aware that psychiatry is an in-demand specialty that offers broad autonomy and rewarding clinical work.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Physician assistants (PAs) who choose to specialize in psychiatry will find enormous opportunity, as the need for well-trained and knowledgeable mental health providers is acute. Those PAs who obtain additional training and/or certification in psychiatry will be highly valued and sought-after, with an abundance of job opportunities. Physician assistant programs should continue to improve didactic and clinical training for their students in psychiatry, and encourage increased numbers of PAs to consider psychiatry as a career path.

Related Resources

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Psychiatry Certificate of Added Qualifications. https://www.nccpa.net/psychiatry.

- Association of Physician Assistants in Psychiatry. http://psychpa.com/.

1. Japen B. Psychiatrist shortage escalates as U.S. mental health needs grow. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2018/02/25/psychiatrist-shortage-escalates-as-u-s-mental-health-needs-grow/. Published February 25, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. Active physicians in the largest specialties, 2017. Table 1.1. Number of active physicians in the largest specialties by major professional activity, 2017. www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492556/1-1-chart.html. Published December 2017. Accessed February 1, 2019.

3. Weiner S. Addressing the escalating psychiatrist shortage. Association of American Medical Colleges AAMCNews. https://news.aamc.org/patient-care/article/addressing-escalating-psychiatrist-shortage/. Published February 13, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

4. Cunningham P. Beyond parity: Primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Affairs. 2009;28(S1). https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. Accessed February 1, 2019.

5. Psychiatrist shortage felt nationwide - and in VA system. The Gazette. https://www.thegazette.com/subject/news/government/psychiatrist-shortage-felt-nationwide-x2014-and-in-va-system-20170813. Published August 13, 2017. Accessed February 1, 2019.

6. Satiani A, Niedermier J, Satiani B, et al. Projected workforce of psychiatrists in the United States: a population analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(6):710-713.

7. Levine D. What’s the answer to the shortage of mental health care providers? U.S. News & World Report. https://health.usnews.com/health-care/patient-advice/articles/2018-05-25/whats-the-answer-to-the-shortage-of-mental-health-care-providers. Published May 25, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

8. Martsolf GR, Barnes H, Richards MR, et al. Employment of advanced practice clinicians in physician practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):988-990.

9. Hass V. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners are not interchangeable. JAAPA. 2016;29(4):9-12.

10. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. 2018 Statistical profile of certified physician assistants by specialty. Annual report. https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2018StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPAsbySpecialty1.pdf. Published July 2019. Accessed February 1, 2019.

11. Larson EH, Hart LG. Growth and change in the physician assistant workforce in the United States, 1967-2000. J Allied Health. 2007;36(3):121-130.

12. Perna G. NPs and PAs are joining docs in specialty care. Physicians Practice. http://www.physicianspractice.com/staff-salary-survey/nps-and-pas-are-joining-docs-specialty-care. Published May 9, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2019.

13. Pasquini S. Does PA program length matter? The Physician Assistant Life. www.thepalife.com/does-pa-program-length-matter/. Accessed February 1, 2019.

14. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PAs in specialty practice. An analysis of need, growth and future. http://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/Whitepaper-PAsinSpecialtyPractice.pdf. Published October 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

15. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PArtners in Mental Health Initiative: Stakeholders Report 2018. http://www.nccpahealthfoundation.net/Portals/0/PDFs/PArtnersinMentalHealthInitiativeStakeholderReport2018.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

16. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PArtners in Mental Health Summit: proceedings and Recommendations. Leesburg, Virginia – June 4-6, 2017. https://www.nccpahealthfoundation.net/Portals/0/PDFs/SummitProceedings.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed August 7, 2019.

“Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased, pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow, raze out the written troubles of the brain, and with some sweet oblivious antidote cleanse the stuffed bosom of that perilous stuff which weighs upon the heart?”

– William Shakespeare, Macbeth

For many years, the United States has been experiencing a shortage of psychiatrists. Currently, there are only 28,000 to 33,000 psychiatrists in active patient care practice in the United States.1,2 The lack of psychiatrists is pronounced in many areas of the country, including rural regions, some urban neighborhoods, and community health centers. In approximately half of US counties, there are no psychiatrists at all.3

While patients with mental illnesses often are treated in primary care settings, the need for qualified mental health clinicians remains acute. Two-thirds of primary care physicians report difficulty in referring patients for mental health care, due to the shortage of clinicians and long wait times for patients to be seen.4 In the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the shortage of qualified psychiatrists is even more acute, due to ongoing combat operations and an increased number of missions and manpower requirements to complete them, which also has increased veterans’ mental health needs during life after their service.5

The outlook for providing adequate numbers of psychiatrists in the future is even more concerning. Based on a population analysis, Satiani et al6 predicts an extreme shortage of psychiatrists for the next 30 years, with the availability of psychiatrists per population expected to reach an all-time low by 2024. Based on ratios from the Department of Health and Human Services, this would mean a shortage of 14,000 to 31,000 psychiatrists over the next 5 to 6 years alone. This is due primarily to the expected retirement of more than 25,000 psychiatrists age >55 during the next 5 years. With mental illness becoming the costliest medical condition in the United States, at $201 billion annually, the potential impact of this shortage is alarming.6

Addressing the shortage

Efforts aimed at increasing the number of psychiatrists, improving access to care, and improving efficiency of care have focused on expanding recruitment and training capacity in psychiatry residency programs, utilizing new models such as telepsychiatry and Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams, increasing the number of Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics, and embedding psychiatrists in large primary care practices.7 Another avenue for addressing the psychiatrist shortage has been the training and hiring of more advanced practice clinicians, including physician assistants (PAs) and

Physician assistants and NPs make up the largest group of non-physician mental health professionals who can prescribe medications. Physician assistant training is most closely aligned with the allopathic training model of physicians.9 Some typical duties of PAs working in a psychiatric setting are outlined in the Table.

How many PAs elect to specialize in psychiatry, compared with the percentage of physicians who choose psychiatry as a career? Data from the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) revealed that in 2018 there were 1,470 PAs working in psychiatry, or approximately 1.5% of all PAs in practice.10 In comparison, approximately 5% of physicians complete residency training in psychiatry.2

Continue to: Although the need for more...

Although the need for more mental health professionals—especially those who can prescribe—is well documented, PA practice in psychiatry has been underrepresented, with PAs choosing to work in the field at a rate just over one-fourth that of physicians. While there is no clear explanation for the lack of PAs in psychiatry, PA programs’ training model has been to produce generalist clinicians who can work in numerous settings, particularly primary care. However, during the past several decades, PA practice choice has shifted largely from primary care to specialty care. In 1974, an estimated 68.8% of PAs worked in primary care settings (family medicine/general practice, general internal medicine, and general pediatrics), while the remainder worked in specialty areas.11 In contrast, by 2018, only 25.8% of PAs worked in primary care settings.10 Despite more PAs choosing to work in medical specialties, the number choosing psychiatry remains very low. With the great need for well-trained mental health prescribers, the opportunity for growth in this area of medicine and increased salary incentive should serve as an impetus for PAs to consider psychiatry. Like their physician counterparts, PAs working in specialty areas of medicine tend to be paid more, sometimes substantially more.12

Training requirements

What is the level of training and experience for PAs who choose to work in psychiatry? Physician assistant program applicants generally come from a pre-med background with a Bachelor’s degree in a hard science, and often have medical experience as a nurse, paramedic, emergency medical technician, or other health profession. Physician assistants are trained in the same medical model of care as physicians, although their training is structured over an average 27-month cycle, with 1 year devoted to didactic education and 1 year or more devoted to clinical training.13 They are qualified to “go to work” soon after graduating and passing the NCCPA Physician Assistant National Certifying Examination (PANCE), and may require a state license. Upon graduation, PAs have received approximately 1,000 hours of didactic and 2,000 hours of clinical training across the general spectrum of medicine.

Physician assistants who choose to specialize in psychiatry may complete a residency/fellowship in psychiatry of approximately 1 year, and/or obtain the Certificate of Added Qualification (CAQ) in psychiatry from the NCCPA. Most PAs who work in psychiatry have done so through “on-the-job” training, where their knowledge and skills have expanded through working with their supervising physician(s) and gaining experience from their clinical practice and self-study. For many years, there were only 1 or 2 PA residency/fellowship opportunities in psychiatry in the United States for PAs wanting to acquire additional formal didactic and clinical knowledge and skills in psychiatry. Fortunately, there has been a growing number of PA residencies/fellowships in psychiatry. These programs are typically 1 year in length and can provide a PA who wants to specialize in psychiatry with an additional 300 to >500 didactic and 1,500 to 2,000 clinical hours of training in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of the spectrum of psychiatric conditions. Currently, there are 10 to 12 programs in the United States that offer this training to PAs, producing approximately 18 to 20 residency-trained psychiatric PAs each year. Almost one-half of PAs who are residency-trained in psychiatry are being trained in VA facilities and affiliated institutions sponsored by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Along with the PA’s basic education, the additional knowledge and skills acquired in residency prepare the PA to be a highly capable psychiatric clinician, with a combined 1,500 didactic and 4,000 clinical hours of training in general medicine plus psychiatry. The addition of the CAQ demonstrates the PA’s commitment to additional learning in psychiatry, as the added work experience requirements, the additional postgraduate continuing medical education requirements in psychiatry, and the psychiatry board exam clearly show dedication to a higher level of knowledge and skill in the specialty.

Because PAs have been trained as generalists who are able to work in any setting or specialty, they have a broad range of knowledge in medicine and surgery. This can be especially helpful when working in a psychiatric practice, where they can provide an added medical focus to patient care when needed. As more PAs are choosing to work in a specialty area for much or all of their practice, they are able to gain significant knowledge and skills in that specialty.

Getting more PAs into psychiatry

So what does the future hold for PAs in psychiatry? The increased need and opportunity in mental health will likely draw a higher percentage of PAs to this specialty. Hopefully, an increase in the number of PA psychiatry residencies or advanced mental health training opportunities, and the continued goal of obtaining the CAQ in psychiatry, will serve to increase the number of psychiatric PAs.14

Continue to: The NCCPA has also recognized...

The NCCPA has also recognized the importance of increasing PA knowledge and integration in mental health care by establishing a PArtners in Mental Health Steering Committee, composed of leaders from the largest PA organizations, including the American Academy of Physician Assistants, the Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant, the Physician Assistant Education Association, the Physician Assistant Foundation, and other PA and interprofessional members. The NCCPA’s PArtners in Mental Health Initiative: Stakeholders Report 2018 outlines an ongoing strategy to increase PA engagement in and awareness of mental health among the PA community and future providers via outreach to member organizations, state societies, PA programs, and those at the state and national level who legislate and reimburse PA services for mental health care.15 The Steering Committee’s recommendations include:

- enhancing PA educational approaches in mental health

- strengthening the PA practice environment to address mental health needs and foster integration

- promoting national campaigns to raise the profile of PAs addressing mental health across disciplines

- creating an organizational structure that incorporates current participants, offers backbone support to this movement, and plans for communication and financing.16

The role of PA educators

In the end, PA leaders and educators will play a substantial role in influencing future PAs to seek a career in psychiatry. Currently, psychiatry education varies among PA programs. Some offer robust didactic and clinical education and training, while other programs are limited in the number of hours of psychiatric didactic education, and may offer psychiatry clinical opportunities only in the context of a primary care setting, rather than in a dedicated psychiatric setting. Additionally, the mission of training PAs for generalist, primary care practice may limit many PAs from considering psychiatry because they do not necessarily view psychiatry as closely aligning with primary care generalist practice the way cardiology, pulmonology, gastroenterology, or other internal medicine specialties do.

In terms of PA postgraduate education, many PAs have completed residencies in surgical specialties or emergency medicine. Coincidentally, surgery and emergency medicine residencies are the most prolific of the postgraduate residency programs, adding a significant number of well-trained PAs to these specialties. The NCCPA also offers the CAQ for Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, Orthopedic Surgery, and Emergency Medicine, which may attract PAs into these specialties, with or without completing a residency.

Because the NCCPA also offers the CAQ in Psychiatry, it would be reasonable and attractive for PAs who complete a psychiatry residency to obtain this certification. In fact, the PA psychiatry residency at our own institution trains our residents to be fully prepared and board-eligible to take the CAQ in Psychiatry upon completing residency. To date, every PA residency graduate who has completed our program and taken the CAQ in Psychiatry exam has passed and been awarded the CAQ in Psychiatry. They have proven themselves to the program and the NCCPA, and have impressed their employers with their clinical abilities and medical knowledge.

For psychiatrists, the addition of a well-trained or willing-to-be-trained PA to the practice can provide an economic advantage and strong team partnership that ensures optimal care for patients in this time of shortage of skilled mental health clinicians. The need is clear and will continue. Physician assistant educators must provide adequate didactic and clinical training in psychiatry to PA students, and support students interested in pursuing a career path in this specialty. Physician assistant organizations must meet the challenge of increasing the number of PAs in psychiatry, and encourage the establishment of additional post-graduate residency programs in psychiatry for PAs. Lastly, more PAs need to be made aware that psychiatry is an in-demand specialty that offers broad autonomy and rewarding clinical work.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Physician assistants (PAs) who choose to specialize in psychiatry will find enormous opportunity, as the need for well-trained and knowledgeable mental health providers is acute. Those PAs who obtain additional training and/or certification in psychiatry will be highly valued and sought-after, with an abundance of job opportunities. Physician assistant programs should continue to improve didactic and clinical training for their students in psychiatry, and encourage increased numbers of PAs to consider psychiatry as a career path.

Related Resources

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Psychiatry Certificate of Added Qualifications. https://www.nccpa.net/psychiatry.

- Association of Physician Assistants in Psychiatry. http://psychpa.com/.

“Canst thou not minister to a mind diseased, pluck from the memory a rooted sorrow, raze out the written troubles of the brain, and with some sweet oblivious antidote cleanse the stuffed bosom of that perilous stuff which weighs upon the heart?”

– William Shakespeare, Macbeth

For many years, the United States has been experiencing a shortage of psychiatrists. Currently, there are only 28,000 to 33,000 psychiatrists in active patient care practice in the United States.1,2 The lack of psychiatrists is pronounced in many areas of the country, including rural regions, some urban neighborhoods, and community health centers. In approximately half of US counties, there are no psychiatrists at all.3

While patients with mental illnesses often are treated in primary care settings, the need for qualified mental health clinicians remains acute. Two-thirds of primary care physicians report difficulty in referring patients for mental health care, due to the shortage of clinicians and long wait times for patients to be seen.4 In the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the shortage of qualified psychiatrists is even more acute, due to ongoing combat operations and an increased number of missions and manpower requirements to complete them, which also has increased veterans’ mental health needs during life after their service.5

The outlook for providing adequate numbers of psychiatrists in the future is even more concerning. Based on a population analysis, Satiani et al6 predicts an extreme shortage of psychiatrists for the next 30 years, with the availability of psychiatrists per population expected to reach an all-time low by 2024. Based on ratios from the Department of Health and Human Services, this would mean a shortage of 14,000 to 31,000 psychiatrists over the next 5 to 6 years alone. This is due primarily to the expected retirement of more than 25,000 psychiatrists age >55 during the next 5 years. With mental illness becoming the costliest medical condition in the United States, at $201 billion annually, the potential impact of this shortage is alarming.6

Addressing the shortage

Efforts aimed at increasing the number of psychiatrists, improving access to care, and improving efficiency of care have focused on expanding recruitment and training capacity in psychiatry residency programs, utilizing new models such as telepsychiatry and Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) teams, increasing the number of Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics, and embedding psychiatrists in large primary care practices.7 Another avenue for addressing the psychiatrist shortage has been the training and hiring of more advanced practice clinicians, including physician assistants (PAs) and

Physician assistants and NPs make up the largest group of non-physician mental health professionals who can prescribe medications. Physician assistant training is most closely aligned with the allopathic training model of physicians.9 Some typical duties of PAs working in a psychiatric setting are outlined in the Table.

How many PAs elect to specialize in psychiatry, compared with the percentage of physicians who choose psychiatry as a career? Data from the National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants (NCCPA) revealed that in 2018 there were 1,470 PAs working in psychiatry, or approximately 1.5% of all PAs in practice.10 In comparison, approximately 5% of physicians complete residency training in psychiatry.2

Continue to: Although the need for more...

Although the need for more mental health professionals—especially those who can prescribe—is well documented, PA practice in psychiatry has been underrepresented, with PAs choosing to work in the field at a rate just over one-fourth that of physicians. While there is no clear explanation for the lack of PAs in psychiatry, PA programs’ training model has been to produce generalist clinicians who can work in numerous settings, particularly primary care. However, during the past several decades, PA practice choice has shifted largely from primary care to specialty care. In 1974, an estimated 68.8% of PAs worked in primary care settings (family medicine/general practice, general internal medicine, and general pediatrics), while the remainder worked in specialty areas.11 In contrast, by 2018, only 25.8% of PAs worked in primary care settings.10 Despite more PAs choosing to work in medical specialties, the number choosing psychiatry remains very low. With the great need for well-trained mental health prescribers, the opportunity for growth in this area of medicine and increased salary incentive should serve as an impetus for PAs to consider psychiatry. Like their physician counterparts, PAs working in specialty areas of medicine tend to be paid more, sometimes substantially more.12

Training requirements

What is the level of training and experience for PAs who choose to work in psychiatry? Physician assistant program applicants generally come from a pre-med background with a Bachelor’s degree in a hard science, and often have medical experience as a nurse, paramedic, emergency medical technician, or other health profession. Physician assistants are trained in the same medical model of care as physicians, although their training is structured over an average 27-month cycle, with 1 year devoted to didactic education and 1 year or more devoted to clinical training.13 They are qualified to “go to work” soon after graduating and passing the NCCPA Physician Assistant National Certifying Examination (PANCE), and may require a state license. Upon graduation, PAs have received approximately 1,000 hours of didactic and 2,000 hours of clinical training across the general spectrum of medicine.

Physician assistants who choose to specialize in psychiatry may complete a residency/fellowship in psychiatry of approximately 1 year, and/or obtain the Certificate of Added Qualification (CAQ) in psychiatry from the NCCPA. Most PAs who work in psychiatry have done so through “on-the-job” training, where their knowledge and skills have expanded through working with their supervising physician(s) and gaining experience from their clinical practice and self-study. For many years, there were only 1 or 2 PA residency/fellowship opportunities in psychiatry in the United States for PAs wanting to acquire additional formal didactic and clinical knowledge and skills in psychiatry. Fortunately, there has been a growing number of PA residencies/fellowships in psychiatry. These programs are typically 1 year in length and can provide a PA who wants to specialize in psychiatry with an additional 300 to >500 didactic and 1,500 to 2,000 clinical hours of training in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of the spectrum of psychiatric conditions. Currently, there are 10 to 12 programs in the United States that offer this training to PAs, producing approximately 18 to 20 residency-trained psychiatric PAs each year. Almost one-half of PAs who are residency-trained in psychiatry are being trained in VA facilities and affiliated institutions sponsored by the VA Office of Academic Affiliations. Along with the PA’s basic education, the additional knowledge and skills acquired in residency prepare the PA to be a highly capable psychiatric clinician, with a combined 1,500 didactic and 4,000 clinical hours of training in general medicine plus psychiatry. The addition of the CAQ demonstrates the PA’s commitment to additional learning in psychiatry, as the added work experience requirements, the additional postgraduate continuing medical education requirements in psychiatry, and the psychiatry board exam clearly show dedication to a higher level of knowledge and skill in the specialty.

Because PAs have been trained as generalists who are able to work in any setting or specialty, they have a broad range of knowledge in medicine and surgery. This can be especially helpful when working in a psychiatric practice, where they can provide an added medical focus to patient care when needed. As more PAs are choosing to work in a specialty area for much or all of their practice, they are able to gain significant knowledge and skills in that specialty.

Getting more PAs into psychiatry

So what does the future hold for PAs in psychiatry? The increased need and opportunity in mental health will likely draw a higher percentage of PAs to this specialty. Hopefully, an increase in the number of PA psychiatry residencies or advanced mental health training opportunities, and the continued goal of obtaining the CAQ in psychiatry, will serve to increase the number of psychiatric PAs.14

Continue to: The NCCPA has also recognized...

The NCCPA has also recognized the importance of increasing PA knowledge and integration in mental health care by establishing a PArtners in Mental Health Steering Committee, composed of leaders from the largest PA organizations, including the American Academy of Physician Assistants, the Accreditation Review Commission on Education for the Physician Assistant, the Physician Assistant Education Association, the Physician Assistant Foundation, and other PA and interprofessional members. The NCCPA’s PArtners in Mental Health Initiative: Stakeholders Report 2018 outlines an ongoing strategy to increase PA engagement in and awareness of mental health among the PA community and future providers via outreach to member organizations, state societies, PA programs, and those at the state and national level who legislate and reimburse PA services for mental health care.15 The Steering Committee’s recommendations include:

- enhancing PA educational approaches in mental health

- strengthening the PA practice environment to address mental health needs and foster integration

- promoting national campaigns to raise the profile of PAs addressing mental health across disciplines

- creating an organizational structure that incorporates current participants, offers backbone support to this movement, and plans for communication and financing.16

The role of PA educators

In the end, PA leaders and educators will play a substantial role in influencing future PAs to seek a career in psychiatry. Currently, psychiatry education varies among PA programs. Some offer robust didactic and clinical education and training, while other programs are limited in the number of hours of psychiatric didactic education, and may offer psychiatry clinical opportunities only in the context of a primary care setting, rather than in a dedicated psychiatric setting. Additionally, the mission of training PAs for generalist, primary care practice may limit many PAs from considering psychiatry because they do not necessarily view psychiatry as closely aligning with primary care generalist practice the way cardiology, pulmonology, gastroenterology, or other internal medicine specialties do.

In terms of PA postgraduate education, many PAs have completed residencies in surgical specialties or emergency medicine. Coincidentally, surgery and emergency medicine residencies are the most prolific of the postgraduate residency programs, adding a significant number of well-trained PAs to these specialties. The NCCPA also offers the CAQ for Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, Orthopedic Surgery, and Emergency Medicine, which may attract PAs into these specialties, with or without completing a residency.

Because the NCCPA also offers the CAQ in Psychiatry, it would be reasonable and attractive for PAs who complete a psychiatry residency to obtain this certification. In fact, the PA psychiatry residency at our own institution trains our residents to be fully prepared and board-eligible to take the CAQ in Psychiatry upon completing residency. To date, every PA residency graduate who has completed our program and taken the CAQ in Psychiatry exam has passed and been awarded the CAQ in Psychiatry. They have proven themselves to the program and the NCCPA, and have impressed their employers with their clinical abilities and medical knowledge.

For psychiatrists, the addition of a well-trained or willing-to-be-trained PA to the practice can provide an economic advantage and strong team partnership that ensures optimal care for patients in this time of shortage of skilled mental health clinicians. The need is clear and will continue. Physician assistant educators must provide adequate didactic and clinical training in psychiatry to PA students, and support students interested in pursuing a career path in this specialty. Physician assistant organizations must meet the challenge of increasing the number of PAs in psychiatry, and encourage the establishment of additional post-graduate residency programs in psychiatry for PAs. Lastly, more PAs need to be made aware that psychiatry is an in-demand specialty that offers broad autonomy and rewarding clinical work.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Physician assistants (PAs) who choose to specialize in psychiatry will find enormous opportunity, as the need for well-trained and knowledgeable mental health providers is acute. Those PAs who obtain additional training and/or certification in psychiatry will be highly valued and sought-after, with an abundance of job opportunities. Physician assistant programs should continue to improve didactic and clinical training for their students in psychiatry, and encourage increased numbers of PAs to consider psychiatry as a career path.

Related Resources

- National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. Psychiatry Certificate of Added Qualifications. https://www.nccpa.net/psychiatry.

- Association of Physician Assistants in Psychiatry. http://psychpa.com/.

1. Japen B. Psychiatrist shortage escalates as U.S. mental health needs grow. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2018/02/25/psychiatrist-shortage-escalates-as-u-s-mental-health-needs-grow/. Published February 25, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. Active physicians in the largest specialties, 2017. Table 1.1. Number of active physicians in the largest specialties by major professional activity, 2017. www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492556/1-1-chart.html. Published December 2017. Accessed February 1, 2019.

3. Weiner S. Addressing the escalating psychiatrist shortage. Association of American Medical Colleges AAMCNews. https://news.aamc.org/patient-care/article/addressing-escalating-psychiatrist-shortage/. Published February 13, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

4. Cunningham P. Beyond parity: Primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Affairs. 2009;28(S1). https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. Accessed February 1, 2019.

5. Psychiatrist shortage felt nationwide - and in VA system. The Gazette. https://www.thegazette.com/subject/news/government/psychiatrist-shortage-felt-nationwide-x2014-and-in-va-system-20170813. Published August 13, 2017. Accessed February 1, 2019.

6. Satiani A, Niedermier J, Satiani B, et al. Projected workforce of psychiatrists in the United States: a population analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(6):710-713.

7. Levine D. What’s the answer to the shortage of mental health care providers? U.S. News & World Report. https://health.usnews.com/health-care/patient-advice/articles/2018-05-25/whats-the-answer-to-the-shortage-of-mental-health-care-providers. Published May 25, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

8. Martsolf GR, Barnes H, Richards MR, et al. Employment of advanced practice clinicians in physician practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):988-990.

9. Hass V. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners are not interchangeable. JAAPA. 2016;29(4):9-12.

10. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. 2018 Statistical profile of certified physician assistants by specialty. Annual report. https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2018StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPAsbySpecialty1.pdf. Published July 2019. Accessed February 1, 2019.

11. Larson EH, Hart LG. Growth and change in the physician assistant workforce in the United States, 1967-2000. J Allied Health. 2007;36(3):121-130.

12. Perna G. NPs and PAs are joining docs in specialty care. Physicians Practice. http://www.physicianspractice.com/staff-salary-survey/nps-and-pas-are-joining-docs-specialty-care. Published May 9, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2019.

13. Pasquini S. Does PA program length matter? The Physician Assistant Life. www.thepalife.com/does-pa-program-length-matter/. Accessed February 1, 2019.

14. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PAs in specialty practice. An analysis of need, growth and future. http://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/Whitepaper-PAsinSpecialtyPractice.pdf. Published October 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

15. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PArtners in Mental Health Initiative: Stakeholders Report 2018. http://www.nccpahealthfoundation.net/Portals/0/PDFs/PArtnersinMentalHealthInitiativeStakeholderReport2018.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

16. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PArtners in Mental Health Summit: proceedings and Recommendations. Leesburg, Virginia – June 4-6, 2017. https://www.nccpahealthfoundation.net/Portals/0/PDFs/SummitProceedings.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed August 7, 2019.

1. Japen B. Psychiatrist shortage escalates as U.S. mental health needs grow. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/brucejapsen/2018/02/25/psychiatrist-shortage-escalates-as-u-s-mental-health-needs-grow/. Published February 25, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

2. Association of American Medical Colleges. Active physicians in the largest specialties, 2017. Table 1.1. Number of active physicians in the largest specialties by major professional activity, 2017. www.aamc.org/data/workforce/reports/492556/1-1-chart.html. Published December 2017. Accessed February 1, 2019.

3. Weiner S. Addressing the escalating psychiatrist shortage. Association of American Medical Colleges AAMCNews. https://news.aamc.org/patient-care/article/addressing-escalating-psychiatrist-shortage/. Published February 13, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

4. Cunningham P. Beyond parity: Primary care physicians’ perspectives on access to mental health care. Health Affairs. 2009;28(S1). https://www.healthaffairs.org/doi/full/10.1377/hlthaff.28.3.w490. Accessed February 1, 2019.

5. Psychiatrist shortage felt nationwide - and in VA system. The Gazette. https://www.thegazette.com/subject/news/government/psychiatrist-shortage-felt-nationwide-x2014-and-in-va-system-20170813. Published August 13, 2017. Accessed February 1, 2019.

6. Satiani A, Niedermier J, Satiani B, et al. Projected workforce of psychiatrists in the United States: a population analysis. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(6):710-713.

7. Levine D. What’s the answer to the shortage of mental health care providers? U.S. News & World Report. https://health.usnews.com/health-care/patient-advice/articles/2018-05-25/whats-the-answer-to-the-shortage-of-mental-health-care-providers. Published May 25, 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

8. Martsolf GR, Barnes H, Richards MR, et al. Employment of advanced practice clinicians in physician practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(7):988-990.

9. Hass V. Physician assistants and nurse practitioners are not interchangeable. JAAPA. 2016;29(4):9-12.

10. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. 2018 Statistical profile of certified physician assistants by specialty. Annual report. https://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/2018StatisticalProfileofCertifiedPAsbySpecialty1.pdf. Published July 2019. Accessed February 1, 2019.

11. Larson EH, Hart LG. Growth and change in the physician assistant workforce in the United States, 1967-2000. J Allied Health. 2007;36(3):121-130.

12. Perna G. NPs and PAs are joining docs in specialty care. Physicians Practice. http://www.physicianspractice.com/staff-salary-survey/nps-and-pas-are-joining-docs-specialty-care. Published May 9, 2016. Accessed February 1, 2019.

13. Pasquini S. Does PA program length matter? The Physician Assistant Life. www.thepalife.com/does-pa-program-length-matter/. Accessed February 1, 2019.

14. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PAs in specialty practice. An analysis of need, growth and future. http://prodcmsstoragesa.blob.core.windows.net/uploads/files/Whitepaper-PAsinSpecialtyPractice.pdf. Published October 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

15. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PArtners in Mental Health Initiative: Stakeholders Report 2018. http://www.nccpahealthfoundation.net/Portals/0/PDFs/PArtnersinMentalHealthInitiativeStakeholderReport2018.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed February 1, 2019.

16. National Commission on Certification of Physician Assistants. PArtners in Mental Health Summit: proceedings and Recommendations. Leesburg, Virginia – June 4-6, 2017. https://www.nccpahealthfoundation.net/Portals/0/PDFs/SummitProceedings.pdf. Published 2017. Accessed August 7, 2019.