User login

Visual hallucinations: Differentiating psychiatric and neurologic causes

A visual hallucination is a visual percept experienced when awake that is not elicited by an external stimulus. Historically, hallucinations have been synonymous with psychiatric disease, most notably schizophrenia; however, over recent decades, hallucinations have been categorized based on their underlying etiology as psychodynamic (primary psychiatric), psychophysiologic (primary neurologic/structural), and psychobiochemical (neurotransmitter dysfunction).1 Presently, visual hallucinations are known to be caused by a wide variety of primary psychiatric, neurologic, ophthalmologic, and chemically-mediated conditions. Despite these causes, clinically differentiating the characteristics and qualities of visual hallucinations is often a lesser-known skillset among clinicians. The utility of this skillset is important for the clinician’s ability to differentiate the expected and unexpected characteristics of visual hallucinations in patients with both known and unknown neuropsychiatric conditions.

Though many primary psychiatric and neurologic conditions have been associated with and/or known to cause visual hallucinations, this review focuses on the following grouped causes:

- Primary psychiatric causes: psychiatric disorders with psychotic features and delirium; and

- Primary neurologic causes: neurodegenerative disease/dementias, seizure disorders, migraine disorders, vision loss, peduncular hallucinosis, and hypnagogic/hypnopompic phenomena.

Because the accepted definition of visual hallucinations excludes visual percepts elicited by external stimuli, drug-induced hallucinations would not qualify for either of these categories. Additionally, most studies reporting on the effects of drug-induced hallucinations did not control for underlying comorbid psychiatric conditions, dementia, or delirium, and thus the results cannot be attributed to the drug alone, nor is it possible to identify reliable trends in the properties of the hallucinations.2 The goals of this review are to characterize visual hallucinations experienced as a result of primary psychiatric and primary neurologic conditions and describe key grouping and differentiating features to help guide the diagnosis.

Visual hallucinations in the general population

A review of 6 studies (N = 42,519) reported that the prevalence of visual hallucinations in the general population is 7.3%.3 The prevalence decreases to 6% when visual hallucinations arising from physical illness or drug/chemical consumption are excluded. The prevalence of visual hallucinations in the general population has been associated with comorbid anxiety, stress, bereavement, and psychotic pathology.4,5 Regarding the age of occurrence of visual hallucinations in the general population, there appears to be a bimodal distribution.3 One peak appears in later adolescence and early adulthood, which corresponds with higher rates of psychosis, and another peak occurs late in life, which corresponds to a higher prevalence of neurodegenerative conditions and visual impairment.

Primary psychiatric causes

Most studies of visual hallucinations in primary psychiatric conditions have specifically evaluated patients with schizophrenia and mood disorders with psychotic features.6,7 In a review of 29 studies (N = 5,873) that specifically examined visual hallucinations in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, Waters et al3 found a wide range of reported prevalence (4% to 65%) and a weighted mean prevalence of 27%. In contrast, the prevalence of auditory hallucinations in these participants ranged from 25% to 86%, with a weighted mean of 59%.3

Hallucinations are a known but less common symptom of mood disorders that present with psychotic features.8 Waters et al3 also examined the prevalence of visual and auditory hallucinations in mood disorders (including mania, bipolar disorder, and depression) reported in 12 studies (N = 2,892).3 They found the prevalence of visual hallucinations in patients with mood disorders ranged from 6% to 27%, with a weighted mean of 15%, compared to the weighted mean of 28% who experienced auditory hallucinations. Visual hallucinations in primary psychiatric conditions are associated with more severe disease, longer hospitalizations, and poorer prognoses.9-11

Visual hallucinations of psychosis

In patients with psychotic symptoms, the characteristics of the visually hallucinated entity as well as the cognitive and emotional perception of the hallucinations are notably different than in patients with other, nonpsychiatric causes of visual hallucations.3

Continue to: Content and perceived physical properties

Content and perceived physical properties. Hallucinated entities are most often perceived as solid, 3-dimensional, well-detailed, life-sized people, animals, and objects (often fire) or events existing in the real world.3 The entity is almost always perceived as real, with accurate form and color, fine edges, and shadow; is often out of reach of the perceiver; and can be stationary or moving within the physical properties of the external environment.3

Timing and triggers. The temporal properties vary widely. Hallucinations can last from seconds to minutes and occur at any time of day, though by definition, they must occur while the individual is awake.3 Visual hallucinations in psychosis are more common during times of acute stress, strong emotions, and tiredness.3

Patient reaction and belief. Because of realistic qualities of the visual hallucination and the perception that it is real, patients commonly attempt to participate in some activity in relation to the hallucination, such as moving away from or attempting to interact with it.3 Additionally, patients usually perceive the hallucinated entity as uncontrollable, and are surprised when the entity appears or disappears. Though the content of the hallucination is usually impersonal, the meaning the patient attributes to the presence of the hallucinated entity is usually perceived as very personal and often requiring action. The hallucination may represent a harbinger, sign, or omen, and is often interpreted religiously or spiritually and accompanied by comorbid delusions.3

Visual hallucinations of delirium

Delirium is a syndrome of altered mentation—most notably consciousness, attention, and orientation—that occurs as a result of ≥1 metabolic, infectious, drug-induced, or other medical conditions and often manifests as an acute secondary psychotic illness.12 Multiple patient and environmental characteristics have been identified as risk factors for developing delirium, including multiple and/or severe medical illnesses, preexisting dementia, depression, advanced age, polypharmacy, having an indwelling urinary catheter, impaired sight or hearing, and low albumin levels.13-15 The development of delirium is significantly and positively associated with regular alcohol use, benzodiazepine withdrawal, and angiotensin receptor blocker and dopamine receptor agonist usage.15 Approximately 40% of patients with delirium have symptoms of psychosis, and in contrast to the hallucinations experienced by patients with schizophrenia, visual hallucinations are the most common type of hallucinations seen in delirium (27%).13 In a 2021 review that included 602 patients with delirium, Tachibana et al15 found that approximately 26% experienced hallucinations, 92% of which were visual hallucinations.

Content, perceived physical properties, and reaction. Because of the limited attention and cognitive function of patients with delirium, less is known about the content of their visual hallucinations. However, much like those with primary psychotic symptoms, patients with delirium often report seeing complex, normal-sized, concrete entities, most commonly people. Tachibana et al15 found that the hallucinated person is more often a stranger than a familiar person, but (rarely) may be an ethereal being such as a devil or ghost. The next most common visually hallucinated entities were creatures, most frequently insects and animals. Other common hallucinations were visions of events or objects, such as fires, falling ceilings, or water. Similar to those with primary psychotic illness such as schizophrenia, patients with delirium often experience emotional distress, anxiety, fear, and confusion in response to the hallucinated person, object, and/or event.15

Continue to: Primary neurologic causes

Primary neurologic causes

Visual hallucinations in neurodegenerative diseases

Patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson disease (PD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), or Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) commonly experience hallucinations as a feature of their condition. However, the true cause of these hallucinations often cannot be directly attributed to any specific pathophysiology because these patients often have multiple coexisting risk factors, such as advanced age, major depressive disorder, use of neuroactive medications, and co-occurring somatic illness. Though the prevalence of visual hallucinations varies widely between studies, with 15% to 40% reported in patients with PD, the prevalence roughly doubles in patients with PD-associated dementia (30% to 60%), and is reported by 60% to 90% of those with DLB.16-18 Hallucinations are generally thought to be less common in Alzheimer disease; such patients most commonly experience visual hallucinations, although the reported prevalence ranges widely (4% to 59%).19,20 Notably, similarly to hallucinations experienced in patients with delirium, and in contrast to those with psychosis, visual hallucinations are more common than auditory hallucinations in neurodegenerative diseases.20 Hallucinations are not common in individuals with CJD but are a key defining feature of the He

Content, perceived physical properties, and reaction. Similar to the visual hallucinations experienced by patients with psychosis or delirium, those experienced in patients with PD, DLB, or CJD are often complex, most commonly of people, followed by animals and objects. The presence of “passage hallucinations”—in which a person or animal is seen in a patient’s peripheral vision, but passes out of their visual field before the entity can be directly visualized—is common.20 Those with PD also commonly have visual hallucinations in which the form of an object appears distorted (dysmorphopsia) or the color of an object appears distorted (metachromatopsia), though these would better be classified as illusions because a real object is being perceived with distortion.22

Hallucinations are more common in the evening and at night. “Presence hallucinations” are a common type of hallucination that cannot be directly related to a specific sensory modality such as vision, though they are commonly described by patients with PD as a seen or perceived image (usually a person) that is not directly in the individual’s visual field.17 These presence hallucinations are often described as being behind the patient or in a visualized scene of what was about to happen. Before developing the dementia and myoclonus also seen in sporadic CJD, patients with the Heidenhain variant of CJD describe illusions such as metachromatopsia, dysmorphia, and micropsia that eventually develop into frank visual hallucinations, which have been poorly reported in medical literature.22,23 There are no generalizable trends in the temporal nature of visual hallucinations in patients with neurodegenerative diseases. In most cases of visual hallucinations in patients with PD and dementia, insight relating to the perception varies widely based on the patient’s cognitive status. Subsequently, patients’ reactions to the hallucinations also vary widely.

Visual hallucinations in epileptic seizures

Occipital lobe epilepsies represent 1% to 4.6% of all epilepsies; however, these represent 20% to 30% of benign childhood partial epilepsies.24,25 These are commonly associated with various types of visual hallucinations depending upon the location of the seizure onset within the occipital lobe. These are referred to as visual auras.26 Visual auras are classified into simple visual hallucinations, complex visual hallucinations, visual illusions, and ictal amaurosis (hemifield blindness or complete blindness).

Content, perceived physical properties, and reaction. Simple visual hallucinations are often described as brief, stereotypical flashing lights of various shapes and colors. These images may flicker, change shape, or take on a geometric or irregular pattern. Appearances can be repetitive and stereotyped, are often reported as moving horizontally from the periphery to the center of the visual field, and can spread to the entire visual field. Most often, these hallucinations occur for 5 to 30 seconds, and have no discernible provoking factors. Complex visual hallucinations consist of formed images of animals, people, or elaborate scenes. These are believed to reflect activation of a larger area of cortex in the temporo-parieto-occipital region, which is the visual association cortex. Very rarely, occipital lobe seizures can manifest with ictal amaurosis.24

Continue to: Simple visual auras...

Simple visual auras have a very high localizing value to the occipital lobe. The primary visual cortex (Brodmann area 17) is situated in the banks of calcarine fissure and activation of this region produces these simple hallucinations. If the hallucinations are consistently lateralized, the seizures are very likely to be coming from the contralateral occipital lobe.

Visual hallucinations in brain tumors

In general, a tumor anywhere along the optic path can produce visual hallucinations; however, the exact causal mechanism of the hallucinations is unknown. Moreover, tumors in different locations—namely the occipital lobes, temporal lobes, and frontal lobes—appear to produce visual hallucinations with substantially different characteristics.27-29 Further complicating the search for the mechanism of these hallucinations is the fact that tumors are epileptogenic. In addition, 36% to 48% of patients with brain tumors have mood symptoms (depression/mania), and 22% to 24% have psychotic symptoms (delusions/hallucinations); these symptoms are considerably location-dependent.30-32

Content and associated signs/symptoms. There are some grouped symptoms and/or hallucination characteristics associated with cerebral tumors in different lobes of the brain, though these symptoms are not specific. The visual hallucinations associated with brain tumors are typically confined to the field of vision that corresponds to the location of the tumor. Additionally, many such patients have a baseline visual field defect to some extent due to the tumor location.

In patients with occipital lobe tumors, visual hallucinations closely resemble those experienced in occipital lobe seizures, specifically bright flashes of light in colorful simple and complex shapes. Interestingly, those with occipital lobe tumors report xanthopsia, a form of chromatopsia in which objects in their field of view appear abnormally colored a yellowish shade.26,27

In patients with temporal lobe tumors, more complex visual hallucinations of people, objects, and events occurring around them are often accompanied by auditory hallucinations, olfactory hallucinations, and/or anosmia.28In those with frontal lobe tumors, similar complex visual hallucinations of people, objects, and events are seen, and olfactory hallucinations and/or anosmia are often experienced. However, these patients often have a lower likelihood of experiencing auditory hallucinations, and a higher likelihood of developing personality changes and depression than other psychotic symptoms. The visual hallucinations experienced in those with frontal lobe tumors are more likely to have violent content.29

Continue to: Visual hallucinations in migraine with aura

Visual hallucinations in migraine with aura

The estimated prevalence of migraine in the general population is 15% to 29%; 31% of those with migraine experience auras.33-35 Approximately 99% of those with migraine auras experience some type of associated visual phenomena.33,36 The pathophysiology of migraine is believed to be related to spreading cortical depression, in which a slowly propagating wave of neuroelectric depolarization travels over the cortex, followed by a depression of normal brain activity. Visual aura is thought to occur due to the resulting changes in cortical activity in the visual cortex; however, the exact electrophysiology of visual migraine aura is not entirely known.37,38 Though most patients with visual migraine aura experience simple visual hallucinations, complex hallucinations have been reported in the (very rare) cases of migraine coma and familial hemiplegic migraine.39

Content and associated signs/symptoms. The most common hallucinated entities reported by patients with migraine with aura are zigzag, flashing/sparkling, black and white curved figure(s) in the center of the visual field, commonly called a scintillating phosphene or scintillating scotoma.36 The perceived entity is often singular and gradually moves from the center to the periphery of the visual field. These visual hallucinations appear in front of all other objects in the visual field and do not interact with the environment or observer, or resemble or morph into any real-world objects, though they may change in contour, size, and color. The scintillating nature of the hallucination often resolves within minutes, usually leaving a scotoma, or area of vision loss, in the area, with resolution back to baseline vision within 1 hour. The straight, zigzag, and usually black-and-white nature of the scintillating phosphenes of migraine are in notable contrast to the colorful, often circular visual hallucinations experienced in patients with occipital lobe seizures.25

Visual hallucinations in peduncular hallucinosis

Peduncular hallucinosis is a syndrome of predominantly dreamlike visual hallucinations that occurs in the setting of lesions in the midbrain and/or thalamus.40 A recent review of the lesion etiology found that approximately 63% are caused by focal infarction and approximately 15% are caused by mass lesions; subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, and demyelination cause approximately 5% of cases each.40 Additionally, a review of the affected brainstem anatomy showed almost all lesions were found in the paramedian reticular formations of the midbrain and pons, with the vast majority of lesions affecting or adjacent to the oculomotor and raphe nuclei of the midbrain.39 Due to the commonly involved visual pathway, some researchers have suggested these hallucinations may be the result of a release phenomenon.39

Content and associated signs/symptoms. The visual hallucinations of peduncular hallucinosis usually start 1 to 5 days after the causal lesion forms, last several minutes to hours, and most stop after 1 to 3 weeks; however, cases of hallucinations lasting for years have been reported. These hallucinations have a diurnal pattern of usually appearing while the patient is resting in the evening and/or preparing for sleep. The characteristics of visual hallucinations vary widely from simple distortions in how real objects appear to colorful and vivid hallucinated events and people who can interact with the observer. The content of the visual hallucinations often changes in nature during the hallucination, or from one hallucination to the next. The hallucinated entities can be worldly or extraterrestrial. Once these patients fall asleep, they often have equally vivid and unusual dreams, with content similar to their visual hallucinations. Due to the anatomical involvement of the nigrostriatal pathway and oculomotor nuclei, co-occurring parkinsonism, ataxia, and oculomotor nerve palsy are common and can be a key clinical feature in establishing the diagnosis. Though patients with peduncular hallucinations commonly fear their hallucinations, they often eventually gain insight, which eases their anxiety.39

Other causes

Visual hallucinations in visual impairment

Visual hallucinations are a diagnostic requirement for Charles Bonnet syndrome, in which individuals with vision loss experience visual hallucinations in the corresponding field of vision loss.41 A lesion at any point in the visual pathway that produces visual loss can lead to Charles Bonnet syndrome; however, age-related macular degeneration is the most common cause.42 The hallucinations of Charles Bonnet syndrome are believed to be a release phenomenon, given the defective visual pathway and resultant dysfunction in visual processing. The prevalence of Charles Bonnet syndrome ranges widely by study. Larger studies report a prevalence of 11% to 27% in patients with age-related macular degeneration, depending on the severity of vision loss.43,44 Because there are many causes of Charles Bonnet syndrome, and because a recent study found that only 15% of patients with this syndrome told their eye care clinician and that 21% had not reported their hallucinatory symptoms to anyone, the true prevalence is unknown.42 Though the onset of visual hallucinations correlates with the onset of vision loss, there appears to be no association between the nature or complexity of the hallucinations and the severity or progression of the patient’s vision loss.45 Some studies have reported either the onset of or a higher frequency of visual hallucinations at a time of visual recovery (for example, treatment or exudative age-related macular degeneration), which suggests that hallucinations may be triggered by fluctuations in visual acuity.46,47 Additional risk factors for experiencing visual hallucinations in the setting of visual pathway deficit include a history of stroke, social isolation, poor cognitive function, poor lighting, and age ≥65.

Continue to: Content and associated signs/symptoms

Content and associated signs/symptoms. The visual hallucinations of patients with Charles Bonnet syndrome appear almost exclusively in the defective visual field. Images tend to be complex, colored, with moving parts, and appear in front of the patient. The hallucinations are usually of familiar or normal-appearing people or mundane objects, and as such, the patient often does not realize the hallucinated entity is not real. In patients without comorbid psychiatric disease, visual hallucinations are not accompanied by any other types of hallucinations. The most commonly hallucinated entities are people, followed by simple visual hallucinations of geometric patterns, and then by faces (natural or cartoon-like) and inanimate objects. Hallucinations most commonly occur daily or weekly, and upon waking. These hallucinations most often last several minutes, though they can last just a few seconds or for hours. Hallucinations are usually emotionally neutral, but most patients report feeling confused by their appearance and having a fear of underlying psychiatric disease. They often gain insight to the unreal nature of the hallucinations after counseling.48

Visual hallucinations at the sleep/wake interface

Hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations are fleeting perceptual experiences that occur while an individual is falling asleep or waking, respectively.49 Because by definition visual hallucinations occur while the individual is fully awake, categorizing hallucination-like experiences such as hypnagogia and hypnopompia is difficult, especially since these are similar to other states in which alterations in perception are expected (namely a dream state). They are commonly associated with sleep disorders such as narcolepsy, cataplexy, and sleep paralysis.50,51 In a study of 13,057 individuals in the general population, Ohayon et al4 found the overall prevalence of hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations was 24.8% (5.3% visual) and 6.6% (1.5% visual), respectively. Approximately one-third of participants reported having experienced ≥1 hallucinatory experience in their lifetime, regardless of being asleep or awake.4 There was a higher prevalence of hypnagogic/hypnopompic experiences among those who also reported daytime hallucinations or other psychotic features.

Content and associated signs/symptoms. Unfortunately, because of the frequent co-occurrence of sleep disorders and psychiatric conditions, as well as the general paucity of research, it is difficult to characterize the visual phenomenology of hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations. Some evidence suggests the nature of the perception of the objects hallucinated is substantially impacted by the presence of preexisting psychotic symptoms. Insight into the reality of these hallucinations also depends upon the presence of comorbid psychiatric disease. Hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations are often described as complex, colorful, vivid, and dream-like, as if the patient was in a “half sleep” state.52 They are usually described as highly detailed events involving people and/or animals, though they may be grotesque in nature. Perceived entities are often described as undergoing a transformation or being mobile in their environment. Rarely do these perceptions invoke emotion or change the patient’s beliefs. Hypnagogia/hypnopompia also often have an auditory or haptic component to them. Visual phenomena can either appear to take place within an alternative background environment or appear superimposed on the patient’s actual physical environment.

How to determine the cause

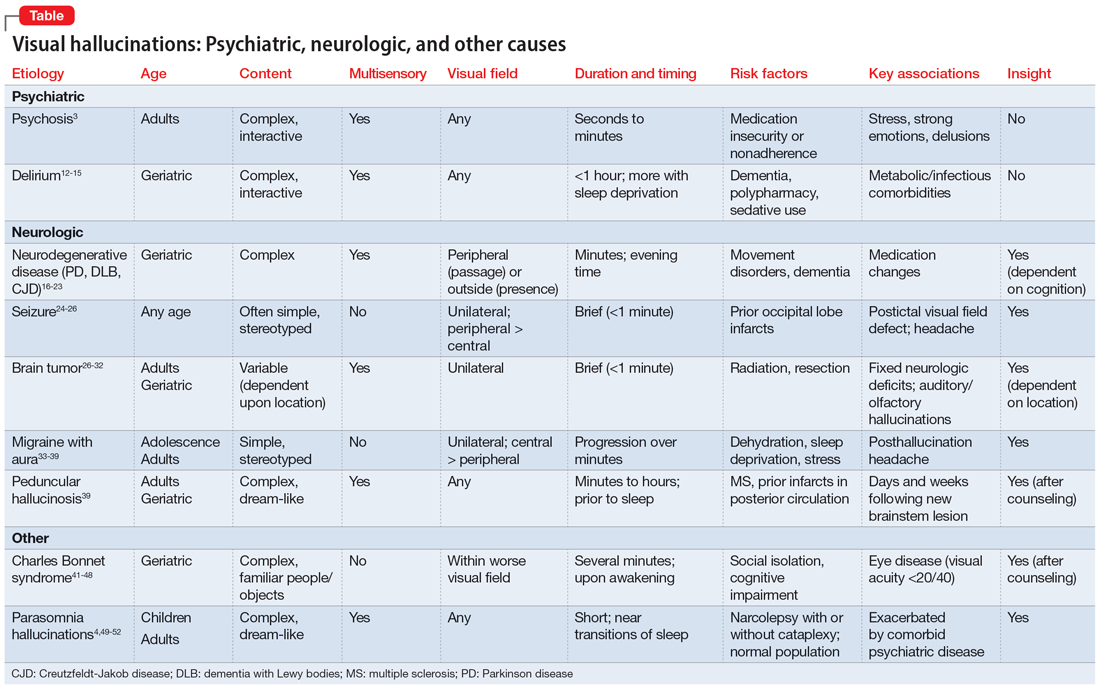

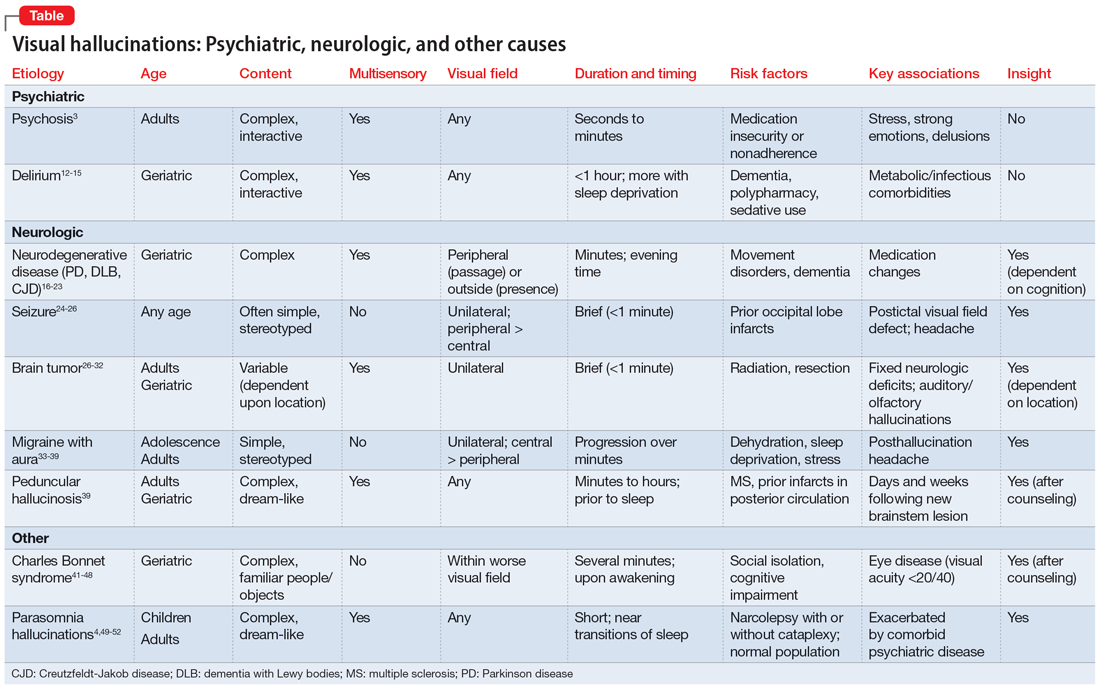

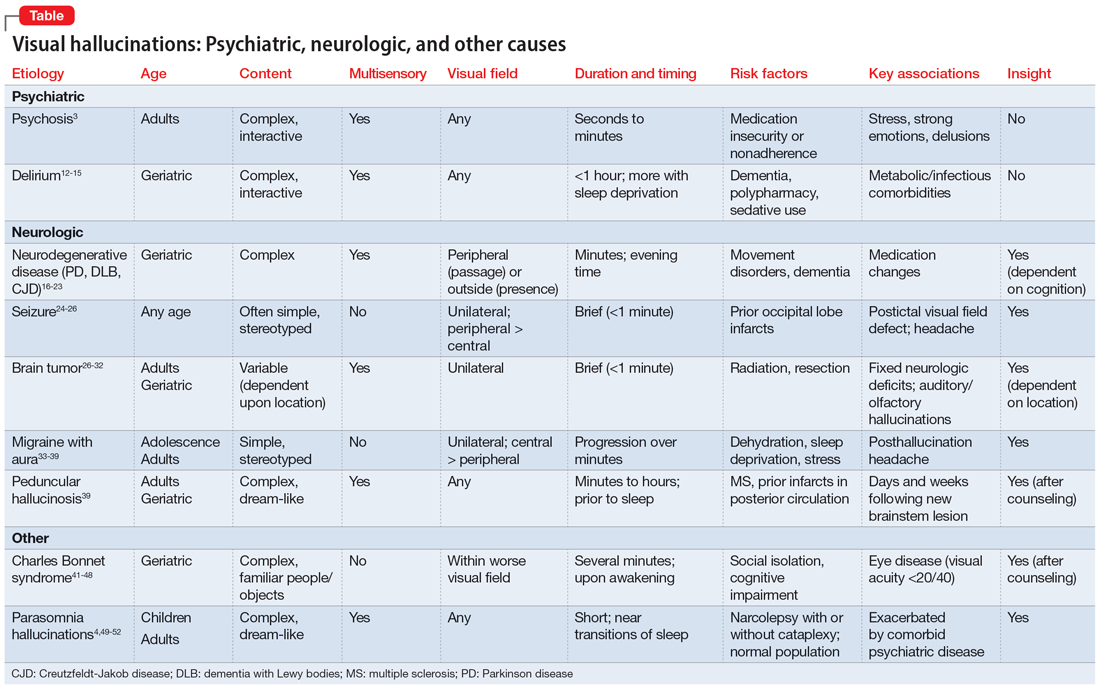

In many of the studies cited in this review, the participants had a considerable amount of psychiatric comorbidity, which makes it difficult to discriminate between pure neurologic and pure psychiatric causes of hallucinations. Though the visual content of the hallucinations (people, objects, shapes, lights) can help clinicians broadly differentiate causes, many other characteristics of both the hallucinations and the patient can help determine the cause (Table3,4,12-39,41-52). The most useful characteristics for discerning the etiology of an individual’s visual hallucinations are the patient’s age, the visual field in which the hallucination occurs, and the complexity/simplicity of the hallucination.

Patient age. Hallucinations associated with primary psychosis decrease with age. The average age of onset of migraine with aura is 21. Occipital lobe seizures occur in early childhood to age 40, but most commonly occur in the second decade.32,36 No trend in age can be reliably determined in individuals who experience hypnagogia/hypnopompia. In contrast, other potential causes of visual hallucinations, such as delirium, neurodegenerative disease, eye disease, and peduncular hallucinosis, are more commonly associated with advanced age.

Continue to: The visual field(s)

The visual field(s) in which the hallucination occurs can help differentiate possible causes in patients with seizure, brain tumor, migraine, or visual impairment. In patients with psychosis, delirium, peduncular hallucinosis, or hypnagogia/hypnopompia, hallucinations can occur in any visual field. Those with neurodegenerative disease, particularly PD, commonly describe seeing so-called passage hallucinations and presence hallucinations, which occur outside of the patient’s direct vision. Visual hallucinations associated with seizure are often unilateral (homonymous left or right hemifield), and contralateral to the affected neurologic structures in the visual neural pathway; they start in the left or right peripheral vision and gradually move to the central visual field. In hallucinations experienced by patients with brain tumors, the hallucinated entities typically appear on the visual field contralateral to the underlying tumor. Visual hallucinations seen in migraine often include a figure that moves from central vision to more lateral in the visual field. The visual hallucinations seen in eye disease (namely Charles Bonnet syndrome) are almost exclusively perceived in the visual fields affected by decreased visual acuity, though non-side-locked visual hallucinations are common in patients with age-related macular degeneration.

Content and complexity. The visual hallucinations perceived in those with psychosis, delirium, neurodegenerative disease, and sleep disorders are generally complex. These hallucinations tend to be of people, animals, scenes, or faces and include color and associated sound, with moving parts and interactivity with either the patient or the environment. These are in contrast to the simple visual hallucinations of visual cortex seizures, brain tumors, and migraine aura, which are often reported as brightly colored or black/white lights, flashes, and shapes, with or without associated auditory, olfactory, or somatic sensation. Furthermore, hallucinations due to seizure and brain tumor (also likely due to seizure) are often of brightly colored shapes and lights with curved edges, while patients with migraine more commonly report singular sparkling black/white objects with straight lines.

Bottom Line

Though there are no features known to be specific to only 1 cause of visual hallucinations, some characteristics of both the patient and the hallucinations can help direct the diagnostic differential. The most useful characteristics are the patient’s age, the visual field in which the hallucination occurs, and the complexity/ simplicity of the hallucination.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- O’Brien J, Taylor JP, Ballard C, et al. Visual hallucinations in neurological and ophthalmological disease: pathophysiology and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020; 91(5):512-519. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2019-322702

1. Asaad G, Shapiro B. Hallucinations: theoretical and clinical overview. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;143(9):1088-1097.

2. Taam MA, Boissieu P, Taam RA, et al. Drug-induced hallucination: a case/non-case study in the French Pharmacovigilance Database. Article in French. Eur J Psychiatry. 2015;29(1):21-31.

3. Waters F, Collerton D, Ffytche DH, et al. Visual hallucinations in the psychosis spectrum and comparative information from neurodegenerative disorders and disease. Schizophr Bull. 2014;40(Suppl 4):S233-S245.

4. Ohayon MM. Prevalence of hallucinations and their pathological associations in the general population. Psychiatry Res. 2000;97(2-3):153-164.

5. Rees WD. The hallucinations of widowhood. Br Med J. 1971;4(5778):37-41.

6. Delespaul P, deVries M, van Os J. Determinants of occurrence and recovery from hallucinations in daily life. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2002;37(3):97-104.

7. Gauntlett-Gilbert J, Kuipers E. Phenomenology of visual hallucinations in psychiatric conditions. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003;191(3):203-205.

8. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR. Manic Depressive Illness. Oxford University Press, Inc.; 1999.

9. Mueser KT, Bellack AS, Brady EU. Hallucinations in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;82(1):26-29.

10. McCabe MS, Fowler RC, Cadoret RJ, et al. Symptom differences in schizophrenia with good and bad prognosis. Am J Psychiatry. 1972;128(10):1239-1243.

11. Baethge C, Baldessarini RJ, Freudenthal K, et al. Hallucinations in bipolar disorder: characteristics and comparison to unipolar depression and schizophrenia. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7(2):136-145.

12. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

13. Ahmed S, Leurent B, Sampson EL. Risk factors for incident delirium among older people in acute hospital medical units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Age Ageing. 2014;43(3):326-333.

14. Webster R, Holroyd S. Prevalence of psychotic symptoms in delirium. Psychosomatics. 2000;41(6):519-522.

15. Tachibana M, Inada T, Ichida M, et al. Factors affecting hallucinations in patients with delirium. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):13005. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-92578-1

16. Fenelon G, Mahieux F, Huon R, et al. Hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease: prevalence, phenomenology and risk factors. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 4):733-745.

17. Papapetropoulos S, Argyriou AA, Ellul J. Factors associated with drug-induced visual hallucinations in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol. 2005;252(10):1223-1228.

18. Williams DR, Warren JD, Lees AJ. Using the presence of visual hallucinations to differentiate Parkinson’s disease from atypical parkinsonism. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79(6):652-655.

19. Linszen MMJ, Lemstra AW, Dauwan M, et al. Understanding hallucinations in probable Alzheimer’s disease: very low prevalence rates in a tertiary memory clinic. Alzheimers Dement (Amst). 2018;10:358-362.

20. Burghaus L, Eggers C, Timmermann L, et al. Hallucinations in neurodegenerative diseases. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2012;18(2):149-159.

21. Brar HK, Vaddigiri V, Scicutella A. Of illusions, hallucinations, and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (Heidenhain’s variant). J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;17(1):124-126.

22. Sasaki C, Yokoi K, Takahashi H, et al. Visual illusions in Parkinson’s disease: an interview survey of symptomatology. Psychogeriatrics. 2022;22(1):28-48.

23. Kropp S, Schulz-Schaeffer WJ, Finkenstaedt M, et al. The Heidenhain variant of Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56(1):55-61.

24. Taylor I, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF. Occipital epilepsies: identification of specific and newly recognized syndromes. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 4):753-769.

25. Caraballo R, Cersosimo R, Medina C, et al. Panayiotopoulos-type benign childhood occipital epilepsy: a prospective study. Neurology. 2000;5(8):1096-1100.

26. Chowdhury FA, Silva R, Whatley B, et al. Localisation in focal epilepsy: a practical guide. Practical Neurol. 2021;21(6):481-491.

27. Horrax G, Putnam TJ. Distortions of the visual fields in cases of brain tumour: the field defects and hallucinations produced by tumours of the occipital lobe. Brain. 1932;55(4):499-523.

28. Cushing H. Distortions of the visual fields in cases of brain tumor (6th paper): the field defects produced by temporal lobe lesions. Brain. 1922;44(4):341-396.

29. Fornazzari L, Farcnik K, Smith I, et al. Violent visual hallucinations and aggression in frontal lobe dysfunction: clinical manifestations of deep orbitofrontal foci. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1992;4(1):42-44.

30. Madhusoodanan S, Opler MGA, Moise D, et al. Brain tumor location and psychiatric symptoms: is there an association? A meta-analysis of published cases studies. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10(10):1529-1536.

31. Madhusoodanan S, Sinha A, Moise D. Brain tumors and psychiatric manifestations: a review and analysis. Poster presented at: The American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry Annual Meeting; March 10-13; 2006; San Juan, Puerto Rico.

32. Madhusoodanan S, Danan D, Moise D. Psychiatric manifestations of brain tumors/gliomas. Rivistica Medica. 2007;13(4):209-215.

33. Kirchmann M. Migraine with aura: new understanding from clinical epidemiological studies. Curr Opin Neurol. 2006;19:286-293.

34. Goadsby PJ, Lipton RB, Ferrari MD. Migraine: current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(4):257-270.

35. Waters WE, O’Connor PJ. Prevalence of migraine. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975;38(6):613-616.

36. Russell MB, Olesen J. A nosographic analysis of the migraine aura in a general population. Brain. 1996;119(Pt 2):355-361.

37. Cozzolino O, Marchese M, Trovato F, et al. Understanding spreading depression from headache to sudden unexpected death. Front Neurol. 2018;9:19.

38. Hadjikhani N, Sanchez del Rio M, Wu O, et al. Mechanisms of migraine aura revealed by functional MRI in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(8):4687-4692.

39. Manford M, Andermann F. Complex visual hallucinations. Clinical and neurobiological insights. Brain. 1998;121(Pt 10):1819-1840.

40. Galetta KM, Prasad S. Historical trends in the diagnosis of peduncular hallucinosis. J Neuroophthalmol. 2018;38(4):438-441.

41. Schadlu AP, Schadlu R, Shepherd JB III. Charles Bonnet syndrome: a review. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20(3):219-222.

42. Vukicevic M, Fitzmaurice K. Butterflies and black lace patterns: the prevalence and characteristics of Charles Bonnet hallucinations in an Australian population. Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008;36(7):659-665.

43. Teunisse RJ, Cruysberg JR, Verbeek A, et al. The Charles Bonnet syndrome: a large prospective study in the Netherlands. A study of the prevalence of the Charles Bonnet syndrome and associated factors in 500 patients attending the University Department of Ophthalmology at Nijmegen. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(2):254-257.

44. Holroyd S, Rabins PV, Finkelstein D, et al. Visual hallucination in patients with macular degeneration. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(12):1701-1706.

45. Khan JC, Shahid H, Thurlby DA, et al. Charles Bonnet syndrome in age-related macular degeneration: the nature and frequency of images in subjects with end-stage disease. Ophthalmic Epidemiol. 2008;15(3):202-208.

46. Cohen SY, Bulik A, Tadayoni R, et al. Visual hallucinations and Charles Bonnet syndrome after photodynamic therapy for age related macular degeneration. Br J Ophthalmol. 2003;87(8):977-979.

47. Meyer CH, Mennel S, Horle S, et al. Visual hallucinations after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab in vascular age-related macular degeneration. Am J Ophthalmol. 2007;143(1):169-170.

48. Jan T, Del Castillo J. Visual hallucinations: Charles Bonnet syndrome. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13(6):544-547. doi:10.5811/westjem.2012.7.12891

49. Foulkes D, Vogel G. Mental activity at sleep onset. J Abnorm Psychol. 1965;70:231-243.

50. Mitler MM, Hajdukovic R, Erman M, et al. Narcolepsy. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1990;7(1):93-118.

51. Nishino S. Clinical and neurobiological aspects of narcolepsy. Sleep Med. 2007;8(4):373-399.

52. Schultz SK, Miller DD, Oliver SE, et al. The life course of schizophrenia: age and symptom dimensions. Schizophr Res. 1997;23(1):15-23.

A visual hallucination is a visual percept experienced when awake that is not elicited by an external stimulus. Historically, hallucinations have been synonymous with psychiatric disease, most notably schizophrenia; however, over recent decades, hallucinations have been categorized based on their underlying etiology as psychodynamic (primary psychiatric), psychophysiologic (primary neurologic/structural), and psychobiochemical (neurotransmitter dysfunction).1 Presently, visual hallucinations are known to be caused by a wide variety of primary psychiatric, neurologic, ophthalmologic, and chemically-mediated conditions. Despite these causes, clinically differentiating the characteristics and qualities of visual hallucinations is often a lesser-known skillset among clinicians. The utility of this skillset is important for the clinician’s ability to differentiate the expected and unexpected characteristics of visual hallucinations in patients with both known and unknown neuropsychiatric conditions.

Though many primary psychiatric and neurologic conditions have been associated with and/or known to cause visual hallucinations, this review focuses on the following grouped causes:

- Primary psychiatric causes: psychiatric disorders with psychotic features and delirium; and

- Primary neurologic causes: neurodegenerative disease/dementias, seizure disorders, migraine disorders, vision loss, peduncular hallucinosis, and hypnagogic/hypnopompic phenomena.

Because the accepted definition of visual hallucinations excludes visual percepts elicited by external stimuli, drug-induced hallucinations would not qualify for either of these categories. Additionally, most studies reporting on the effects of drug-induced hallucinations did not control for underlying comorbid psychiatric conditions, dementia, or delirium, and thus the results cannot be attributed to the drug alone, nor is it possible to identify reliable trends in the properties of the hallucinations.2 The goals of this review are to characterize visual hallucinations experienced as a result of primary psychiatric and primary neurologic conditions and describe key grouping and differentiating features to help guide the diagnosis.

Visual hallucinations in the general population

A review of 6 studies (N = 42,519) reported that the prevalence of visual hallucinations in the general population is 7.3%.3 The prevalence decreases to 6% when visual hallucinations arising from physical illness or drug/chemical consumption are excluded. The prevalence of visual hallucinations in the general population has been associated with comorbid anxiety, stress, bereavement, and psychotic pathology.4,5 Regarding the age of occurrence of visual hallucinations in the general population, there appears to be a bimodal distribution.3 One peak appears in later adolescence and early adulthood, which corresponds with higher rates of psychosis, and another peak occurs late in life, which corresponds to a higher prevalence of neurodegenerative conditions and visual impairment.

Primary psychiatric causes

Most studies of visual hallucinations in primary psychiatric conditions have specifically evaluated patients with schizophrenia and mood disorders with psychotic features.6,7 In a review of 29 studies (N = 5,873) that specifically examined visual hallucinations in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, Waters et al3 found a wide range of reported prevalence (4% to 65%) and a weighted mean prevalence of 27%. In contrast, the prevalence of auditory hallucinations in these participants ranged from 25% to 86%, with a weighted mean of 59%.3

Hallucinations are a known but less common symptom of mood disorders that present with psychotic features.8 Waters et al3 also examined the prevalence of visual and auditory hallucinations in mood disorders (including mania, bipolar disorder, and depression) reported in 12 studies (N = 2,892).3 They found the prevalence of visual hallucinations in patients with mood disorders ranged from 6% to 27%, with a weighted mean of 15%, compared to the weighted mean of 28% who experienced auditory hallucinations. Visual hallucinations in primary psychiatric conditions are associated with more severe disease, longer hospitalizations, and poorer prognoses.9-11

Visual hallucinations of psychosis

In patients with psychotic symptoms, the characteristics of the visually hallucinated entity as well as the cognitive and emotional perception of the hallucinations are notably different than in patients with other, nonpsychiatric causes of visual hallucations.3

Continue to: Content and perceived physical properties

Content and perceived physical properties. Hallucinated entities are most often perceived as solid, 3-dimensional, well-detailed, life-sized people, animals, and objects (often fire) or events existing in the real world.3 The entity is almost always perceived as real, with accurate form and color, fine edges, and shadow; is often out of reach of the perceiver; and can be stationary or moving within the physical properties of the external environment.3

Timing and triggers. The temporal properties vary widely. Hallucinations can last from seconds to minutes and occur at any time of day, though by definition, they must occur while the individual is awake.3 Visual hallucinations in psychosis are more common during times of acute stress, strong emotions, and tiredness.3

Patient reaction and belief. Because of realistic qualities of the visual hallucination and the perception that it is real, patients commonly attempt to participate in some activity in relation to the hallucination, such as moving away from or attempting to interact with it.3 Additionally, patients usually perceive the hallucinated entity as uncontrollable, and are surprised when the entity appears or disappears. Though the content of the hallucination is usually impersonal, the meaning the patient attributes to the presence of the hallucinated entity is usually perceived as very personal and often requiring action. The hallucination may represent a harbinger, sign, or omen, and is often interpreted religiously or spiritually and accompanied by comorbid delusions.3

Visual hallucinations of delirium

Delirium is a syndrome of altered mentation—most notably consciousness, attention, and orientation—that occurs as a result of ≥1 metabolic, infectious, drug-induced, or other medical conditions and often manifests as an acute secondary psychotic illness.12 Multiple patient and environmental characteristics have been identified as risk factors for developing delirium, including multiple and/or severe medical illnesses, preexisting dementia, depression, advanced age, polypharmacy, having an indwelling urinary catheter, impaired sight or hearing, and low albumin levels.13-15 The development of delirium is significantly and positively associated with regular alcohol use, benzodiazepine withdrawal, and angiotensin receptor blocker and dopamine receptor agonist usage.15 Approximately 40% of patients with delirium have symptoms of psychosis, and in contrast to the hallucinations experienced by patients with schizophrenia, visual hallucinations are the most common type of hallucinations seen in delirium (27%).13 In a 2021 review that included 602 patients with delirium, Tachibana et al15 found that approximately 26% experienced hallucinations, 92% of which were visual hallucinations.

Content, perceived physical properties, and reaction. Because of the limited attention and cognitive function of patients with delirium, less is known about the content of their visual hallucinations. However, much like those with primary psychotic symptoms, patients with delirium often report seeing complex, normal-sized, concrete entities, most commonly people. Tachibana et al15 found that the hallucinated person is more often a stranger than a familiar person, but (rarely) may be an ethereal being such as a devil or ghost. The next most common visually hallucinated entities were creatures, most frequently insects and animals. Other common hallucinations were visions of events or objects, such as fires, falling ceilings, or water. Similar to those with primary psychotic illness such as schizophrenia, patients with delirium often experience emotional distress, anxiety, fear, and confusion in response to the hallucinated person, object, and/or event.15

Continue to: Primary neurologic causes

Primary neurologic causes

Visual hallucinations in neurodegenerative diseases

Patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson disease (PD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), or Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) commonly experience hallucinations as a feature of their condition. However, the true cause of these hallucinations often cannot be directly attributed to any specific pathophysiology because these patients often have multiple coexisting risk factors, such as advanced age, major depressive disorder, use of neuroactive medications, and co-occurring somatic illness. Though the prevalence of visual hallucinations varies widely between studies, with 15% to 40% reported in patients with PD, the prevalence roughly doubles in patients with PD-associated dementia (30% to 60%), and is reported by 60% to 90% of those with DLB.16-18 Hallucinations are generally thought to be less common in Alzheimer disease; such patients most commonly experience visual hallucinations, although the reported prevalence ranges widely (4% to 59%).19,20 Notably, similarly to hallucinations experienced in patients with delirium, and in contrast to those with psychosis, visual hallucinations are more common than auditory hallucinations in neurodegenerative diseases.20 Hallucinations are not common in individuals with CJD but are a key defining feature of the He

Content, perceived physical properties, and reaction. Similar to the visual hallucinations experienced by patients with psychosis or delirium, those experienced in patients with PD, DLB, or CJD are often complex, most commonly of people, followed by animals and objects. The presence of “passage hallucinations”—in which a person or animal is seen in a patient’s peripheral vision, but passes out of their visual field before the entity can be directly visualized—is common.20 Those with PD also commonly have visual hallucinations in which the form of an object appears distorted (dysmorphopsia) or the color of an object appears distorted (metachromatopsia), though these would better be classified as illusions because a real object is being perceived with distortion.22

Hallucinations are more common in the evening and at night. “Presence hallucinations” are a common type of hallucination that cannot be directly related to a specific sensory modality such as vision, though they are commonly described by patients with PD as a seen or perceived image (usually a person) that is not directly in the individual’s visual field.17 These presence hallucinations are often described as being behind the patient or in a visualized scene of what was about to happen. Before developing the dementia and myoclonus also seen in sporadic CJD, patients with the Heidenhain variant of CJD describe illusions such as metachromatopsia, dysmorphia, and micropsia that eventually develop into frank visual hallucinations, which have been poorly reported in medical literature.22,23 There are no generalizable trends in the temporal nature of visual hallucinations in patients with neurodegenerative diseases. In most cases of visual hallucinations in patients with PD and dementia, insight relating to the perception varies widely based on the patient’s cognitive status. Subsequently, patients’ reactions to the hallucinations also vary widely.

Visual hallucinations in epileptic seizures

Occipital lobe epilepsies represent 1% to 4.6% of all epilepsies; however, these represent 20% to 30% of benign childhood partial epilepsies.24,25 These are commonly associated with various types of visual hallucinations depending upon the location of the seizure onset within the occipital lobe. These are referred to as visual auras.26 Visual auras are classified into simple visual hallucinations, complex visual hallucinations, visual illusions, and ictal amaurosis (hemifield blindness or complete blindness).

Content, perceived physical properties, and reaction. Simple visual hallucinations are often described as brief, stereotypical flashing lights of various shapes and colors. These images may flicker, change shape, or take on a geometric or irregular pattern. Appearances can be repetitive and stereotyped, are often reported as moving horizontally from the periphery to the center of the visual field, and can spread to the entire visual field. Most often, these hallucinations occur for 5 to 30 seconds, and have no discernible provoking factors. Complex visual hallucinations consist of formed images of animals, people, or elaborate scenes. These are believed to reflect activation of a larger area of cortex in the temporo-parieto-occipital region, which is the visual association cortex. Very rarely, occipital lobe seizures can manifest with ictal amaurosis.24

Continue to: Simple visual auras...

Simple visual auras have a very high localizing value to the occipital lobe. The primary visual cortex (Brodmann area 17) is situated in the banks of calcarine fissure and activation of this region produces these simple hallucinations. If the hallucinations are consistently lateralized, the seizures are very likely to be coming from the contralateral occipital lobe.

Visual hallucinations in brain tumors

In general, a tumor anywhere along the optic path can produce visual hallucinations; however, the exact causal mechanism of the hallucinations is unknown. Moreover, tumors in different locations—namely the occipital lobes, temporal lobes, and frontal lobes—appear to produce visual hallucinations with substantially different characteristics.27-29 Further complicating the search for the mechanism of these hallucinations is the fact that tumors are epileptogenic. In addition, 36% to 48% of patients with brain tumors have mood symptoms (depression/mania), and 22% to 24% have psychotic symptoms (delusions/hallucinations); these symptoms are considerably location-dependent.30-32

Content and associated signs/symptoms. There are some grouped symptoms and/or hallucination characteristics associated with cerebral tumors in different lobes of the brain, though these symptoms are not specific. The visual hallucinations associated with brain tumors are typically confined to the field of vision that corresponds to the location of the tumor. Additionally, many such patients have a baseline visual field defect to some extent due to the tumor location.

In patients with occipital lobe tumors, visual hallucinations closely resemble those experienced in occipital lobe seizures, specifically bright flashes of light in colorful simple and complex shapes. Interestingly, those with occipital lobe tumors report xanthopsia, a form of chromatopsia in which objects in their field of view appear abnormally colored a yellowish shade.26,27

In patients with temporal lobe tumors, more complex visual hallucinations of people, objects, and events occurring around them are often accompanied by auditory hallucinations, olfactory hallucinations, and/or anosmia.28In those with frontal lobe tumors, similar complex visual hallucinations of people, objects, and events are seen, and olfactory hallucinations and/or anosmia are often experienced. However, these patients often have a lower likelihood of experiencing auditory hallucinations, and a higher likelihood of developing personality changes and depression than other psychotic symptoms. The visual hallucinations experienced in those with frontal lobe tumors are more likely to have violent content.29

Continue to: Visual hallucinations in migraine with aura

Visual hallucinations in migraine with aura

The estimated prevalence of migraine in the general population is 15% to 29%; 31% of those with migraine experience auras.33-35 Approximately 99% of those with migraine auras experience some type of associated visual phenomena.33,36 The pathophysiology of migraine is believed to be related to spreading cortical depression, in which a slowly propagating wave of neuroelectric depolarization travels over the cortex, followed by a depression of normal brain activity. Visual aura is thought to occur due to the resulting changes in cortical activity in the visual cortex; however, the exact electrophysiology of visual migraine aura is not entirely known.37,38 Though most patients with visual migraine aura experience simple visual hallucinations, complex hallucinations have been reported in the (very rare) cases of migraine coma and familial hemiplegic migraine.39

Content and associated signs/symptoms. The most common hallucinated entities reported by patients with migraine with aura are zigzag, flashing/sparkling, black and white curved figure(s) in the center of the visual field, commonly called a scintillating phosphene or scintillating scotoma.36 The perceived entity is often singular and gradually moves from the center to the periphery of the visual field. These visual hallucinations appear in front of all other objects in the visual field and do not interact with the environment or observer, or resemble or morph into any real-world objects, though they may change in contour, size, and color. The scintillating nature of the hallucination often resolves within minutes, usually leaving a scotoma, or area of vision loss, in the area, with resolution back to baseline vision within 1 hour. The straight, zigzag, and usually black-and-white nature of the scintillating phosphenes of migraine are in notable contrast to the colorful, often circular visual hallucinations experienced in patients with occipital lobe seizures.25

Visual hallucinations in peduncular hallucinosis

Peduncular hallucinosis is a syndrome of predominantly dreamlike visual hallucinations that occurs in the setting of lesions in the midbrain and/or thalamus.40 A recent review of the lesion etiology found that approximately 63% are caused by focal infarction and approximately 15% are caused by mass lesions; subarachnoid hemorrhage, intracerebral hemorrhage, and demyelination cause approximately 5% of cases each.40 Additionally, a review of the affected brainstem anatomy showed almost all lesions were found in the paramedian reticular formations of the midbrain and pons, with the vast majority of lesions affecting or adjacent to the oculomotor and raphe nuclei of the midbrain.39 Due to the commonly involved visual pathway, some researchers have suggested these hallucinations may be the result of a release phenomenon.39

Content and associated signs/symptoms. The visual hallucinations of peduncular hallucinosis usually start 1 to 5 days after the causal lesion forms, last several minutes to hours, and most stop after 1 to 3 weeks; however, cases of hallucinations lasting for years have been reported. These hallucinations have a diurnal pattern of usually appearing while the patient is resting in the evening and/or preparing for sleep. The characteristics of visual hallucinations vary widely from simple distortions in how real objects appear to colorful and vivid hallucinated events and people who can interact with the observer. The content of the visual hallucinations often changes in nature during the hallucination, or from one hallucination to the next. The hallucinated entities can be worldly or extraterrestrial. Once these patients fall asleep, they often have equally vivid and unusual dreams, with content similar to their visual hallucinations. Due to the anatomical involvement of the nigrostriatal pathway and oculomotor nuclei, co-occurring parkinsonism, ataxia, and oculomotor nerve palsy are common and can be a key clinical feature in establishing the diagnosis. Though patients with peduncular hallucinations commonly fear their hallucinations, they often eventually gain insight, which eases their anxiety.39

Other causes

Visual hallucinations in visual impairment

Visual hallucinations are a diagnostic requirement for Charles Bonnet syndrome, in which individuals with vision loss experience visual hallucinations in the corresponding field of vision loss.41 A lesion at any point in the visual pathway that produces visual loss can lead to Charles Bonnet syndrome; however, age-related macular degeneration is the most common cause.42 The hallucinations of Charles Bonnet syndrome are believed to be a release phenomenon, given the defective visual pathway and resultant dysfunction in visual processing. The prevalence of Charles Bonnet syndrome ranges widely by study. Larger studies report a prevalence of 11% to 27% in patients with age-related macular degeneration, depending on the severity of vision loss.43,44 Because there are many causes of Charles Bonnet syndrome, and because a recent study found that only 15% of patients with this syndrome told their eye care clinician and that 21% had not reported their hallucinatory symptoms to anyone, the true prevalence is unknown.42 Though the onset of visual hallucinations correlates with the onset of vision loss, there appears to be no association between the nature or complexity of the hallucinations and the severity or progression of the patient’s vision loss.45 Some studies have reported either the onset of or a higher frequency of visual hallucinations at a time of visual recovery (for example, treatment or exudative age-related macular degeneration), which suggests that hallucinations may be triggered by fluctuations in visual acuity.46,47 Additional risk factors for experiencing visual hallucinations in the setting of visual pathway deficit include a history of stroke, social isolation, poor cognitive function, poor lighting, and age ≥65.

Continue to: Content and associated signs/symptoms

Content and associated signs/symptoms. The visual hallucinations of patients with Charles Bonnet syndrome appear almost exclusively in the defective visual field. Images tend to be complex, colored, with moving parts, and appear in front of the patient. The hallucinations are usually of familiar or normal-appearing people or mundane objects, and as such, the patient often does not realize the hallucinated entity is not real. In patients without comorbid psychiatric disease, visual hallucinations are not accompanied by any other types of hallucinations. The most commonly hallucinated entities are people, followed by simple visual hallucinations of geometric patterns, and then by faces (natural or cartoon-like) and inanimate objects. Hallucinations most commonly occur daily or weekly, and upon waking. These hallucinations most often last several minutes, though they can last just a few seconds or for hours. Hallucinations are usually emotionally neutral, but most patients report feeling confused by their appearance and having a fear of underlying psychiatric disease. They often gain insight to the unreal nature of the hallucinations after counseling.48

Visual hallucinations at the sleep/wake interface

Hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations are fleeting perceptual experiences that occur while an individual is falling asleep or waking, respectively.49 Because by definition visual hallucinations occur while the individual is fully awake, categorizing hallucination-like experiences such as hypnagogia and hypnopompia is difficult, especially since these are similar to other states in which alterations in perception are expected (namely a dream state). They are commonly associated with sleep disorders such as narcolepsy, cataplexy, and sleep paralysis.50,51 In a study of 13,057 individuals in the general population, Ohayon et al4 found the overall prevalence of hypnagogic or hypnopompic hallucinations was 24.8% (5.3% visual) and 6.6% (1.5% visual), respectively. Approximately one-third of participants reported having experienced ≥1 hallucinatory experience in their lifetime, regardless of being asleep or awake.4 There was a higher prevalence of hypnagogic/hypnopompic experiences among those who also reported daytime hallucinations or other psychotic features.

Content and associated signs/symptoms. Unfortunately, because of the frequent co-occurrence of sleep disorders and psychiatric conditions, as well as the general paucity of research, it is difficult to characterize the visual phenomenology of hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations. Some evidence suggests the nature of the perception of the objects hallucinated is substantially impacted by the presence of preexisting psychotic symptoms. Insight into the reality of these hallucinations also depends upon the presence of comorbid psychiatric disease. Hypnagogic/hypnopompic hallucinations are often described as complex, colorful, vivid, and dream-like, as if the patient was in a “half sleep” state.52 They are usually described as highly detailed events involving people and/or animals, though they may be grotesque in nature. Perceived entities are often described as undergoing a transformation or being mobile in their environment. Rarely do these perceptions invoke emotion or change the patient’s beliefs. Hypnagogia/hypnopompia also often have an auditory or haptic component to them. Visual phenomena can either appear to take place within an alternative background environment or appear superimposed on the patient’s actual physical environment.

How to determine the cause

In many of the studies cited in this review, the participants had a considerable amount of psychiatric comorbidity, which makes it difficult to discriminate between pure neurologic and pure psychiatric causes of hallucinations. Though the visual content of the hallucinations (people, objects, shapes, lights) can help clinicians broadly differentiate causes, many other characteristics of both the hallucinations and the patient can help determine the cause (Table3,4,12-39,41-52). The most useful characteristics for discerning the etiology of an individual’s visual hallucinations are the patient’s age, the visual field in which the hallucination occurs, and the complexity/simplicity of the hallucination.

Patient age. Hallucinations associated with primary psychosis decrease with age. The average age of onset of migraine with aura is 21. Occipital lobe seizures occur in early childhood to age 40, but most commonly occur in the second decade.32,36 No trend in age can be reliably determined in individuals who experience hypnagogia/hypnopompia. In contrast, other potential causes of visual hallucinations, such as delirium, neurodegenerative disease, eye disease, and peduncular hallucinosis, are more commonly associated with advanced age.

Continue to: The visual field(s)

The visual field(s) in which the hallucination occurs can help differentiate possible causes in patients with seizure, brain tumor, migraine, or visual impairment. In patients with psychosis, delirium, peduncular hallucinosis, or hypnagogia/hypnopompia, hallucinations can occur in any visual field. Those with neurodegenerative disease, particularly PD, commonly describe seeing so-called passage hallucinations and presence hallucinations, which occur outside of the patient’s direct vision. Visual hallucinations associated with seizure are often unilateral (homonymous left or right hemifield), and contralateral to the affected neurologic structures in the visual neural pathway; they start in the left or right peripheral vision and gradually move to the central visual field. In hallucinations experienced by patients with brain tumors, the hallucinated entities typically appear on the visual field contralateral to the underlying tumor. Visual hallucinations seen in migraine often include a figure that moves from central vision to more lateral in the visual field. The visual hallucinations seen in eye disease (namely Charles Bonnet syndrome) are almost exclusively perceived in the visual fields affected by decreased visual acuity, though non-side-locked visual hallucinations are common in patients with age-related macular degeneration.

Content and complexity. The visual hallucinations perceived in those with psychosis, delirium, neurodegenerative disease, and sleep disorders are generally complex. These hallucinations tend to be of people, animals, scenes, or faces and include color and associated sound, with moving parts and interactivity with either the patient or the environment. These are in contrast to the simple visual hallucinations of visual cortex seizures, brain tumors, and migraine aura, which are often reported as brightly colored or black/white lights, flashes, and shapes, with or without associated auditory, olfactory, or somatic sensation. Furthermore, hallucinations due to seizure and brain tumor (also likely due to seizure) are often of brightly colored shapes and lights with curved edges, while patients with migraine more commonly report singular sparkling black/white objects with straight lines.

Bottom Line

Though there are no features known to be specific to only 1 cause of visual hallucinations, some characteristics of both the patient and the hallucinations can help direct the diagnostic differential. The most useful characteristics are the patient’s age, the visual field in which the hallucination occurs, and the complexity/ simplicity of the hallucination.

Related Resources

- Wang J, Patel D, Francois D. Elaborate hallucinations, but is it a psychotic disorder? Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(2):46-50. doi:10.12788/cp.0091

- O’Brien J, Taylor JP, Ballard C, et al. Visual hallucinations in neurological and ophthalmological disease: pathophysiology and management. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020; 91(5):512-519. doi:10.1136/jnnp-2019-322702

A visual hallucination is a visual percept experienced when awake that is not elicited by an external stimulus. Historically, hallucinations have been synonymous with psychiatric disease, most notably schizophrenia; however, over recent decades, hallucinations have been categorized based on their underlying etiology as psychodynamic (primary psychiatric), psychophysiologic (primary neurologic/structural), and psychobiochemical (neurotransmitter dysfunction).1 Presently, visual hallucinations are known to be caused by a wide variety of primary psychiatric, neurologic, ophthalmologic, and chemically-mediated conditions. Despite these causes, clinically differentiating the characteristics and qualities of visual hallucinations is often a lesser-known skillset among clinicians. The utility of this skillset is important for the clinician’s ability to differentiate the expected and unexpected characteristics of visual hallucinations in patients with both known and unknown neuropsychiatric conditions.

Though many primary psychiatric and neurologic conditions have been associated with and/or known to cause visual hallucinations, this review focuses on the following grouped causes:

- Primary psychiatric causes: psychiatric disorders with psychotic features and delirium; and

- Primary neurologic causes: neurodegenerative disease/dementias, seizure disorders, migraine disorders, vision loss, peduncular hallucinosis, and hypnagogic/hypnopompic phenomena.

Because the accepted definition of visual hallucinations excludes visual percepts elicited by external stimuli, drug-induced hallucinations would not qualify for either of these categories. Additionally, most studies reporting on the effects of drug-induced hallucinations did not control for underlying comorbid psychiatric conditions, dementia, or delirium, and thus the results cannot be attributed to the drug alone, nor is it possible to identify reliable trends in the properties of the hallucinations.2 The goals of this review are to characterize visual hallucinations experienced as a result of primary psychiatric and primary neurologic conditions and describe key grouping and differentiating features to help guide the diagnosis.

Visual hallucinations in the general population

A review of 6 studies (N = 42,519) reported that the prevalence of visual hallucinations in the general population is 7.3%.3 The prevalence decreases to 6% when visual hallucinations arising from physical illness or drug/chemical consumption are excluded. The prevalence of visual hallucinations in the general population has been associated with comorbid anxiety, stress, bereavement, and psychotic pathology.4,5 Regarding the age of occurrence of visual hallucinations in the general population, there appears to be a bimodal distribution.3 One peak appears in later adolescence and early adulthood, which corresponds with higher rates of psychosis, and another peak occurs late in life, which corresponds to a higher prevalence of neurodegenerative conditions and visual impairment.

Primary psychiatric causes

Most studies of visual hallucinations in primary psychiatric conditions have specifically evaluated patients with schizophrenia and mood disorders with psychotic features.6,7 In a review of 29 studies (N = 5,873) that specifically examined visual hallucinations in individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia, Waters et al3 found a wide range of reported prevalence (4% to 65%) and a weighted mean prevalence of 27%. In contrast, the prevalence of auditory hallucinations in these participants ranged from 25% to 86%, with a weighted mean of 59%.3

Hallucinations are a known but less common symptom of mood disorders that present with psychotic features.8 Waters et al3 also examined the prevalence of visual and auditory hallucinations in mood disorders (including mania, bipolar disorder, and depression) reported in 12 studies (N = 2,892).3 They found the prevalence of visual hallucinations in patients with mood disorders ranged from 6% to 27%, with a weighted mean of 15%, compared to the weighted mean of 28% who experienced auditory hallucinations. Visual hallucinations in primary psychiatric conditions are associated with more severe disease, longer hospitalizations, and poorer prognoses.9-11

Visual hallucinations of psychosis

In patients with psychotic symptoms, the characteristics of the visually hallucinated entity as well as the cognitive and emotional perception of the hallucinations are notably different than in patients with other, nonpsychiatric causes of visual hallucations.3

Continue to: Content and perceived physical properties

Content and perceived physical properties. Hallucinated entities are most often perceived as solid, 3-dimensional, well-detailed, life-sized people, animals, and objects (often fire) or events existing in the real world.3 The entity is almost always perceived as real, with accurate form and color, fine edges, and shadow; is often out of reach of the perceiver; and can be stationary or moving within the physical properties of the external environment.3

Timing and triggers. The temporal properties vary widely. Hallucinations can last from seconds to minutes and occur at any time of day, though by definition, they must occur while the individual is awake.3 Visual hallucinations in psychosis are more common during times of acute stress, strong emotions, and tiredness.3

Patient reaction and belief. Because of realistic qualities of the visual hallucination and the perception that it is real, patients commonly attempt to participate in some activity in relation to the hallucination, such as moving away from or attempting to interact with it.3 Additionally, patients usually perceive the hallucinated entity as uncontrollable, and are surprised when the entity appears or disappears. Though the content of the hallucination is usually impersonal, the meaning the patient attributes to the presence of the hallucinated entity is usually perceived as very personal and often requiring action. The hallucination may represent a harbinger, sign, or omen, and is often interpreted religiously or spiritually and accompanied by comorbid delusions.3

Visual hallucinations of delirium

Delirium is a syndrome of altered mentation—most notably consciousness, attention, and orientation—that occurs as a result of ≥1 metabolic, infectious, drug-induced, or other medical conditions and often manifests as an acute secondary psychotic illness.12 Multiple patient and environmental characteristics have been identified as risk factors for developing delirium, including multiple and/or severe medical illnesses, preexisting dementia, depression, advanced age, polypharmacy, having an indwelling urinary catheter, impaired sight or hearing, and low albumin levels.13-15 The development of delirium is significantly and positively associated with regular alcohol use, benzodiazepine withdrawal, and angiotensin receptor blocker and dopamine receptor agonist usage.15 Approximately 40% of patients with delirium have symptoms of psychosis, and in contrast to the hallucinations experienced by patients with schizophrenia, visual hallucinations are the most common type of hallucinations seen in delirium (27%).13 In a 2021 review that included 602 patients with delirium, Tachibana et al15 found that approximately 26% experienced hallucinations, 92% of which were visual hallucinations.

Content, perceived physical properties, and reaction. Because of the limited attention and cognitive function of patients with delirium, less is known about the content of their visual hallucinations. However, much like those with primary psychotic symptoms, patients with delirium often report seeing complex, normal-sized, concrete entities, most commonly people. Tachibana et al15 found that the hallucinated person is more often a stranger than a familiar person, but (rarely) may be an ethereal being such as a devil or ghost. The next most common visually hallucinated entities were creatures, most frequently insects and animals. Other common hallucinations were visions of events or objects, such as fires, falling ceilings, or water. Similar to those with primary psychotic illness such as schizophrenia, patients with delirium often experience emotional distress, anxiety, fear, and confusion in response to the hallucinated person, object, and/or event.15

Continue to: Primary neurologic causes

Primary neurologic causes

Visual hallucinations in neurodegenerative diseases

Patients with neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson disease (PD), dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), or Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD) commonly experience hallucinations as a feature of their condition. However, the true cause of these hallucinations often cannot be directly attributed to any specific pathophysiology because these patients often have multiple coexisting risk factors, such as advanced age, major depressive disorder, use of neuroactive medications, and co-occurring somatic illness. Though the prevalence of visual hallucinations varies widely between studies, with 15% to 40% reported in patients with PD, the prevalence roughly doubles in patients with PD-associated dementia (30% to 60%), and is reported by 60% to 90% of those with DLB.16-18 Hallucinations are generally thought to be less common in Alzheimer disease; such patients most commonly experience visual hallucinations, although the reported prevalence ranges widely (4% to 59%).19,20 Notably, similarly to hallucinations experienced in patients with delirium, and in contrast to those with psychosis, visual hallucinations are more common than auditory hallucinations in neurodegenerative diseases.20 Hallucinations are not common in individuals with CJD but are a key defining feature of the He

Content, perceived physical properties, and reaction. Similar to the visual hallucinations experienced by patients with psychosis or delirium, those experienced in patients with PD, DLB, or CJD are often complex, most commonly of people, followed by animals and objects. The presence of “passage hallucinations”—in which a person or animal is seen in a patient’s peripheral vision, but passes out of their visual field before the entity can be directly visualized—is common.20 Those with PD also commonly have visual hallucinations in which the form of an object appears distorted (dysmorphopsia) or the color of an object appears distorted (metachromatopsia), though these would better be classified as illusions because a real object is being perceived with distortion.22