User login

A Talking Map for Family Meetings in the Intensive Care Unit

From the Department of Neurology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC (Dr. McFarlin), the Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA (Dr. Tulsky), Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (Dr. Back), and Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Arnold).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the use of a cognitive map for navigating family meetings with surrogate decision makers of patients in an intensive care unit.

- Methods: Descriptive report and discussion using an illustrative case to outline the steps in the cognitive map.

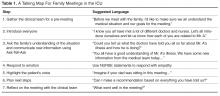

- Results: The use of cognitive maps has improved the ability of physicians to efficiently perform a specific communication skill. During a “goals of care” conversation, the cognitive map follows these steps: (1) Gather the clinical team for a pre-meeting, (2) Introduce everyone, (3) Use the “ask-tell-ask” strategy to communicate information, (4) Respond to emotion, (5) Highlight the patient’s voice, (6) Plan next steps, (7) Reflect on the meeting with the team. Providing this map of key communication skills will help faculty teach learners the core components of a family meeting.

- Conclusion: Practicing the behaviors demonstrated in the cognitive map may increase clinician skill during difficult conversations. Improving communication with surrogate decision makers will increase the support we offer to critically ill patients and their loved ones.

Key words: intensive care unit; communication; family meeting; critical illness; decision making; end of life care.

Family members of patients in the ICU value high-quality communication with the medical team. In fact, family members report that physicians’ communication skills are often more important than their medical skills [1]. Multiple professional societies, including the American Thoracic Society and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, define communication with families as a key component of high-quality critical care. Effective physician-patient communication improves measureable outcomes including decreased ICU length of stay [2] and may reduce distress amongst patients’ families [3]. The American College of Chest Physicians position statement on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Patients with Cardiopulmonary Diseases urges physicians to develop curricula that incorporate interpersonal communication skills into training [4].

Unfortunately, such high-quality communication is not the norm. Surrogate decision makers are often displeased with the frequency of communication, the limited availability of attending physicians, and report feeling excluded from discussions [5]. When family meetings do occur, surrogate decision makers report inadequate understanding of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plans [6].

Physicians also find family meetings difficult. Intensivists worry that high-quality family meetings are time consuming and difficult to do in a busy ICU [7]. Critical care fellows report not feeling adequately trained to conduct family meetings [8]. It makes sense that untrained clinicians would want to avoid a conversation that is emotionally charged, particularly if one is unsure how to respond effectively.

The Case of Mr. A

Thomas A. is a 79-year-old man admitted to the medical intensive care unit 7 days earlier with a large left middle cerebral artery territory infarction. Given his decreased mental status, on admission he was intubated for airway protection. He is awake but aphasic and unable to follow any commands or move his right side. The neurology consultants do not feel this will improve. He has significant secretions and episodes of hypoxia. He has also developed acute on chronic kidney injury and may need to start dialysis. The social worker explains that his need for dialysis limits his placement options and that he will not be able to be discharged to home. Given his lack of improvement the team is concerned he will need a tracheostomy and feeding tube placed in order to safely continue this level of care. A family meeting is arranged to understand Mr. A’s goals of care.

Talking Map Basics

Before each step is discussed in detail, some definitions are needed. “Family” can be defined as anyone important enough, biologically related or not, to be present at a conversation with a clinician [10]. Second, a “family meeting” is a planned event between the family and interdisciplinary members of the ICU team as well as any other health care providers who have been involved in the patient’s care. The meeting takes place in a private space and at a time that is scheduled with the families’ needs in mind. Thus it is different from having families present on rounds or one-off meetings with particular clinicians.

Goals of care meetings are typically held when, in the clinicians’ view, the current treatments are not achieving the previously stated goals. Thus, the meeting has 2 purposes: first, to give the family the bad news that the current plan is not working and second, to develop a new plan based on the patient’s values. The family’s job, as surrogate decision maker, is to provide information about what would be most important to the patient. The clinician’s job is to suggest treatment plans that have the best probability of matching the patient’s values.

Not all of these tasks need be done at once. Some families will not be able to move from hearing bad news to making a decision without having time to first reflect and grieve. Others will need to confer with other family members privately before deciding on a plan. In many cases, a time-limited trial may be the right option with a plan for subsequent meetings. Given this, we recommend checking in with the family between each step to ensure that they feel safe moving ahead. For example, one might ask “Is it OK if we talk about what happens next?”

Talking Map Steps in Detail

1. Gather the Clinical Team for a Pre-Meeting

ICU care involves a large interdisciplinary care team. A “meeting before the meeting” with the entire clinical team is an opportunity to reach consensus on prognosis and therapeutic options, share prior interactions with family, and determine goals for the family meeting. It is also helpful to clarify team members’ roles at the meeting and to choose a primary facilitator. All of this helps to ensure that the family receives a consistent message during the meeting. The pre-meeting is also an opportunity to ask a team member to observe the communication skills of the facilitator and be prepared to give feedback after the meeting.

At this time, the team should also create the proper environment for the family meeting. This includes a quiet room free of interruptions with ample seating, available tissues, and transferred pagers and cell phones.

The intensivist and bedside nurse should always be present at the family meeting, and it is best when the same attending can be at subsequent family meetings Their consistent dual presence provides the uniform communication from the team, can reduce anxiety in family members and the collaboration reduces ICU nurse and physician burnout [11]. For illnesses that involve a specific disease or organ system, it is important to have the specialist at the meeting who can provide the appropriate expertise.

The Pre-Meeting

A family meeting was scheduled in the family meeting room for 3 pm, after morning rounds. Thirty minutes prior to the meeting the medical team, including the MICU intensivist, the bedside nurse, the neurology attending who has been involved in the care, the case manager and 2 residents sat to discuss Mr. A’s care. The neurology team confirmed that this stroke was considered very large and would result in a level of disability that could only be cared for in a nursing home and would require both a tracheostomy and feeding tube for safe care. The bedside nurse relayed that the family had asked if Mr. A. would ever recover enough to get back to his home. The neurology team shared they did not expect much improvement at all. Given the worsening renal failure and need for dialysis the case manager reminded the team that Mr. A’s nursing home placements were limited. The team decided that the intensivist would lead the meeting as she had updated various family members on rounds for the past 4 days and would be on service for another week. The team decided that their goal for the meeting was to make sure the family understands that Mr. A’s several medical illnesses portend a poor prognosis. They recognized this may be breaking bad news to the family. They also wanted to better understand what Mr. A would have thought given this situation. The residents were asked to watch for the family’s responses when the team delivered the news.

2. Introduce Everyone

Each meeting should start with formal introductions. Even if most providers know most family members it is a polite way to start the meeting. Introducing each family member present and how they know the patient provides insight into how the family is constructed and makes decisions. For example, the entire family may defer to the daughter who introduces herself as a nurse. In other situations, although there is one legal decision maker, the family may explain that they make decisions by consensus.

Each member of the treating team should also introduce themselves. Even if the clinician has been working with the family, it is polite to be formal and give your name and role. Given the number of people the family sees every day, one should not assume that the family remembers all of the clinicians.

In teaching hospitals, providers should also help the family understand their level of training. Surrogates do not always understand the different roles or level of training between students, residents and fellows, advanced practice providers, consultants and their attending physicians. Uncertainty about the roles can lead to family members feeling as though they are receiving contradictory information. Family satisfaction decreases when multiple attending physicians are involved in a patient’s care [12]. When possible, a consistent presence among providers at family meetings is always best.

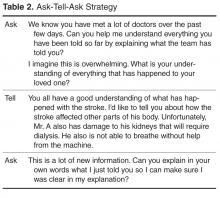

3. Ask the Family's Understanding of the Situation (Ask-Tell-Ask)

Asking the family to explain the situation in their own language reveals how well they understand the medical facts and helps the medical team determine what information will be most helpful to the family. An opening statement might be “We have all seen your dad and talked to many of his providers. It would help us all be on the same page if you can you tell me what the doctors are telling you?” Starting with the family’s understanding builds trust with the medical team as it creates an opportunity for the family to lead the meeting and indicates that the team is available to listen to their concerns. Asking surrogates for their understanding allows them to tell their story and not hear a reiteration of things they already know. Providing time for the family to share their perspective of the care elicits family’s concerns.

In a large meeting, ensure that all members of the family have an opportunity to communicate their concerns. Does a particular person do all of the talking? Are there individuals that do not speak at all? One way to further understand unspoken concerns during the meeting is to ask “I notice you have been quiet, what questions do you have that I can answer?” There may be several rounds of “asking” in order to ensure all the family members’ concerns are heard. Letting the family tell what they have heard helps the clinicians get a better idea of their health literacy. Do they explain information using technical data or jargon? Finally, as the family talks the clinicians can determine how surprising the “serious news” will be to them. For example, if the family says they know their dad is doing much worse and may die, the information to be delivered can be truncated. However if family incorrectly thinks their dad is doing better or is uncertain they will be much more surprised by the serious news.

After providing time for the family to express their understanding, tell them the information the team needs to communicate. When delivering serious news it is important to focus on the key 1 to 2 points you want the family to take away from the meeting. Typically when health care professionals talk to each other, they talk about every medical detail. Families find this amount of information overwhelming and are not sure what is most important, asking “So what does that mean?” Focusing on the “headline” helps the family focus on what you think the most important piece of information is. Studies suggest that what families most want to know is what the information means for the patient’s future and what treatments are possible. After delivering the new information, stop to allow the family space to think about what you said. If you are giving serious news, you will know they have heard what you said as they will get emotional (see next step).

Checking for understanding is the final “ask” in Ask-Tell-Ask. Begin by asking “What questions do you have?” Data in primary care has shown that patients are more likely to ask questions if you ask “what questions do you have” rather than “do you have any questions?” It is important to continue to ask this question until the family has asked all their questions. Often the family’s tough questions do not come until they get more comfortable and confident in the health care team. In cases where one family member is dominant it might also help to say “What questions do others have?” Next, using techniques like the “teach back” model the physician should check in to see what the family is taking away from the conversation. If a family understands, they can “teach back” the information accurately. This “ask” can be done in a way that does not make the family feel they are being tested: “I am not always clear when I communicate. Do you mind telling me back in your own words what you thought I said so I know we are on the same page?” This also provides an opportunity to answer any new questions that arise. Hearing the information directly from the family can allow the team to clarify any misconceptions and give insight into any emotional responses that the family might have.

4. Respond to Emotion

Discussing serious news in the ICU setting naturally leads to an emotional reaction. The clinician’s ability to notice emotional cues and respond with empathy is a key communication skill in family meetings [13]. Emotional reactions impede individual’s ability to process cognitive information and make it hard to think cognitively about what should be done next.

Physicians miss opportunities to respond to emotion in family meetings [14]. Missed opportunities lead to decreased family satisfaction and may lead to treatment decisions not consistent with the wishes of their loved ones. Empathic responses improve the family-clinician relationship and helps build trust and rapport [15]. Well- placed empathic statements may help surrogates disclose concerns that help the physician better understand the goals and values of the family and patient. Families also can more fully process cognitive information when their emotional responses have been attended to.

Physicians can develop the capacity to recognize and respond to the emotional cues family members are delivering. Intensivists should actively look for the emotions, the empathic opportunity, that are displayed by the family. This emotion is the “data” that will help lead to an empathic response. A family that just received bad news typically responds by showing emotion. Clues that emotions are present include: the family asking the same questions multiple times; using emotional words such as “sad” or “frustrated;” existential questions that do not have a cognitive answer such as “Why did God let this happen?;” or non-verbal cues like tears and hand wringing.

Sometimes the emotional responses are more difficult to recognize. Families may continue to ask for more cognitive information after hearing bad news. Someone keeps asking “Why did his kidney function worsen?” or “I thought the team said the chest x-ray looked better.” It is tempting to start answering these questions with more medical facts. However, if the question comes after bad news, it is usually an expression of frustration or sadness rather than a request for more information. Rather than giving information, it might help to acknowledge this by saying “I imagine this new is overwhelming.”

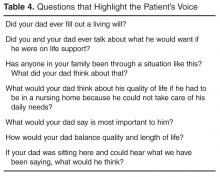

5. Highlight the Patient’s Voice

Family meetings are often used to develop new treatment plans (given that the old plans are not working). In these situations, it is essential to understand what the incapacitated patient would say if they were part of the family meeting. The surrogate’s primary role is to represent the patient’s voice. To do this, surrogates need assistance in applying their critically ill loved one’s thoughts and values to complex, possibly life limiting, situations. Surrogate decision makers struggle with the decisions’ emotional impact, as well as how to reconcile their desires with their loved one’s wishes [18]. This can lead them to make decisions that conflict with the loved one’s values [19] as well as emotional sequelae such as PTSD and depression [20].

As families reflect on their loved one’s values, conflicting desires will arise. For example, someone may have wanted to live as long as possible and also values independence. Or someone may value their ability to think clearly more than being physically well but would not want to be physically dependent on artificial life support. Exploring which values would be more important can help resolve these conflicts.

Clinicians should check for understanding while family members are identifying the values of their loved ones. Providing the family with a summary of what you have heard will help ensure a more accurate understanding of these crucial issues. A summary statement might be, “It sounds like you are saying your dad really valued his independence. He enjoyed being able to take care of his loved ones and himself. Is that right?”

6. Plan Next Steps

The family meeting serves to attend to family emotion and allow space to elicit patients’ values. Following a family meeting surrogate decision makers may be able to begin to consider the next steps in their loved one’s care. If bad news was delivered they may need space to adjust to a different future than they expected. Using an empathic statement of support “We will continue to make sure we communicate with you as we work together to plan next steps” will reassure a family that they have time and space to plan for the future.

Families vary regarding how much physician input they desire in planning next steps [21]. You can explicitly ask how the team can best help the family with decisions: “Some families like to hear the options for next steps from the team and make a decision, other families like to hear a recommendation from the team. What would be the most helpful for you?” Throughout the course of an illness a surrogate’s preference for decision making may change and clinicians should be responsive to those changing needs.

If the surrogate wants a clinician’s recommendation, 3 points are worth stressing. First, the recommendation should be personalized to this patient and his values. The goal is to reveal how the understanding of the patient’s values led to the treatment plan offered. Second, the recommendation should focus primarily on what will be done to achieve the patient’s values. Focusing on what the clinicians will do may help the family feel that the clinicians are still “trying” and not abandoning their loved one. In this case, the team will continue medical care that will help the patient regain/maintain independence. Only after talking about what will be done should the clinician point out that certain interventions will not achieve the patient’s goals and thus will not be done:

“It sounds like your father really valued his independence and that this illness has really taken that away. Knowing this, would it be helpful for me to make a recommendation for next steps?” “I think we should continue providing excellent medical care for your father in hopes he can get better and go home. One the other hand, if he gets worse, we should not use therapies such as CPR or dialysis that are unlikely to help him regain his independence.”

Finally, be concrete when planning next steps. If a time-limited trial of a therapy is proposed, make sure the family understands what a successful and unsuccessful trial will look like. Make plans to meet again on a specific date in order to ensure the family understands the progress being made. If a transition to comfort care is agreed upon, ensure support of the entire family during the next hours to days and offer services such as chaplaincy or child life specialists.

A family may not agree with the recommendation and back and forth discussion can help create a plan that is in line with their understanding of the illness. Rather than convincing, a clinician should keep an open mind about why they and the surrogate disagree. Do they have different views about the patient’s future? Did the medical team misunderstand the patient’s values? Are there emotional factors that inhibit the surrogate’s ability to attend to the discussion? It is only by learning where the disagreement is that a clinician can move the conversation forward.

A surrogate may ask about a therapy that is not beneficial or may increase distress to the patient. The use of “I wish” or “I worry” statements can be helpful at these points. These specific phrases recognize the surrogate’s desire to do more but also imply that the therapies are not helpful.

“I wish that his ability to communicate and tell you what he wants would get better with a little more time as well.”

“I worry that waiting 2 more weeks for improvement will actually cause complications to occur.”

7. Reflect

Family meetings have an impact on both the family and the medical team. Following the meeting, a short debriefing with the clinical team can be helpful. Summarizing the events of the meeting ensures clarity about the treatment plan going forward. It provides team members a chance to discuss conflicts that may have arisen. It allows the participants in the meeting to reflect on what communication skills they used and how they can improve their skills going forward.

Conclusion

Family meetings with surrogate decision makers must navigate multiple agendas of the family and providers. The goal of excellent communication with surrogates in an ICU should be to understand the patient’s goals and values and seek to make treatment plans that align with their perspective. This talking map provides a conceptual framework for physicians to guide a family through these conversations. The framework creates an opportunity to focus on the patient’s values and preferences for care while allowing space to attend to emotional responses to reduce the distress inherent in surrogate decision-making. Practicing the behaviors demonstrated in the talking map may increase clinician skill during difficult conversations. Improving communication with surrogate decision makers will increase the support we offer to critically ill patients and their loved ones.

Corresponding author: Jessica McFarlin, MD, jessmcfarlin@gmail.com.

Funding/support: Dr. Arnold receives support though the Leo H. Criep Chair in Patient Care.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Hickey M. What are the needs of families of critically ill patients? A review of the literature since 1976. Heart Lung 1990;19:401–15.

2. Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA, Barker LK, et al. Changing culture around end-of-life care in the trauma intensive care unit. J Trauma 2008;64:1587–93.

3. Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2007;356:469–78.

4. Selecky PA, Eliasson AH, Hall RI, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with cardiopulmonary diseases. Chest 2005;128:3599–610.

5. Henrich NJ, Dodek P, Heyland D, et al. Qualitative analysis of an intensive care unit family satisfaction survey. Crit Care Med 2011;39:1000–5.

6. Azoulet E, Chevret S, Leleu G, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med 2000;28:3044–9.

7. Curtis JR. Communicating about end-of-life care with patients and families in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin 2004;20:363–80.

8. Hope AA, Hsieh SJ, Howes JM, et al. Let’s talk critical. Development and evaluation of a communication skills training program for critical care fellows. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:505–11.

9. Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:453–60.

10. Vital Talk. Conduct a family conference. Accessed 27 June 2016 at www.vitaltalk.org/clinicians/family.

11. Kramer M, Schmalenberg C. Securing “good” nurse/physician relationships. Nurs Manage 2003;34:34–8.

12. Johnson D, Wilson M, Cavanaugh B, et al. Measuring the ability to meet family needs in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1998;26:266–71.

13. Back AL, Arnold RM. “Isn’t there anything more you can do?’’: when empathic statements work, and when they don’t. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1429–32.

14. Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:844–9.

15. Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;36:5748–52.

16. Back AL, Arnold RM, Tulsky JA. Mastering communication with seriously ill patients: balancing honesty with empathy and hope. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

17. Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:164–77.

18. Schenker Y, White D, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. “It hurts to know…and it helps”: exploring how surrogates in the ICU cope with prognostic information. J Palliat Med 2013;16:243–9.

19. Scheunemann LP, Arnold RM, White DB. The facilitated values history: helping surrogates make authentic decisions for incapacitated patients with advanced illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:480–6.

20. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:987–94.

21. White DB, Braddock CH, Bereknyei et al. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:461–7.

From the Department of Neurology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC (Dr. McFarlin), the Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA (Dr. Tulsky), Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (Dr. Back), and Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Arnold).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the use of a cognitive map for navigating family meetings with surrogate decision makers of patients in an intensive care unit.

- Methods: Descriptive report and discussion using an illustrative case to outline the steps in the cognitive map.

- Results: The use of cognitive maps has improved the ability of physicians to efficiently perform a specific communication skill. During a “goals of care” conversation, the cognitive map follows these steps: (1) Gather the clinical team for a pre-meeting, (2) Introduce everyone, (3) Use the “ask-tell-ask” strategy to communicate information, (4) Respond to emotion, (5) Highlight the patient’s voice, (6) Plan next steps, (7) Reflect on the meeting with the team. Providing this map of key communication skills will help faculty teach learners the core components of a family meeting.

- Conclusion: Practicing the behaviors demonstrated in the cognitive map may increase clinician skill during difficult conversations. Improving communication with surrogate decision makers will increase the support we offer to critically ill patients and their loved ones.

Key words: intensive care unit; communication; family meeting; critical illness; decision making; end of life care.

Family members of patients in the ICU value high-quality communication with the medical team. In fact, family members report that physicians’ communication skills are often more important than their medical skills [1]. Multiple professional societies, including the American Thoracic Society and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, define communication with families as a key component of high-quality critical care. Effective physician-patient communication improves measureable outcomes including decreased ICU length of stay [2] and may reduce distress amongst patients’ families [3]. The American College of Chest Physicians position statement on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Patients with Cardiopulmonary Diseases urges physicians to develop curricula that incorporate interpersonal communication skills into training [4].

Unfortunately, such high-quality communication is not the norm. Surrogate decision makers are often displeased with the frequency of communication, the limited availability of attending physicians, and report feeling excluded from discussions [5]. When family meetings do occur, surrogate decision makers report inadequate understanding of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plans [6].

Physicians also find family meetings difficult. Intensivists worry that high-quality family meetings are time consuming and difficult to do in a busy ICU [7]. Critical care fellows report not feeling adequately trained to conduct family meetings [8]. It makes sense that untrained clinicians would want to avoid a conversation that is emotionally charged, particularly if one is unsure how to respond effectively.

The Case of Mr. A

Thomas A. is a 79-year-old man admitted to the medical intensive care unit 7 days earlier with a large left middle cerebral artery territory infarction. Given his decreased mental status, on admission he was intubated for airway protection. He is awake but aphasic and unable to follow any commands or move his right side. The neurology consultants do not feel this will improve. He has significant secretions and episodes of hypoxia. He has also developed acute on chronic kidney injury and may need to start dialysis. The social worker explains that his need for dialysis limits his placement options and that he will not be able to be discharged to home. Given his lack of improvement the team is concerned he will need a tracheostomy and feeding tube placed in order to safely continue this level of care. A family meeting is arranged to understand Mr. A’s goals of care.

Talking Map Basics

Before each step is discussed in detail, some definitions are needed. “Family” can be defined as anyone important enough, biologically related or not, to be present at a conversation with a clinician [10]. Second, a “family meeting” is a planned event between the family and interdisciplinary members of the ICU team as well as any other health care providers who have been involved in the patient’s care. The meeting takes place in a private space and at a time that is scheduled with the families’ needs in mind. Thus it is different from having families present on rounds or one-off meetings with particular clinicians.

Goals of care meetings are typically held when, in the clinicians’ view, the current treatments are not achieving the previously stated goals. Thus, the meeting has 2 purposes: first, to give the family the bad news that the current plan is not working and second, to develop a new plan based on the patient’s values. The family’s job, as surrogate decision maker, is to provide information about what would be most important to the patient. The clinician’s job is to suggest treatment plans that have the best probability of matching the patient’s values.

Not all of these tasks need be done at once. Some families will not be able to move from hearing bad news to making a decision without having time to first reflect and grieve. Others will need to confer with other family members privately before deciding on a plan. In many cases, a time-limited trial may be the right option with a plan for subsequent meetings. Given this, we recommend checking in with the family between each step to ensure that they feel safe moving ahead. For example, one might ask “Is it OK if we talk about what happens next?”

Talking Map Steps in Detail

1. Gather the Clinical Team for a Pre-Meeting

ICU care involves a large interdisciplinary care team. A “meeting before the meeting” with the entire clinical team is an opportunity to reach consensus on prognosis and therapeutic options, share prior interactions with family, and determine goals for the family meeting. It is also helpful to clarify team members’ roles at the meeting and to choose a primary facilitator. All of this helps to ensure that the family receives a consistent message during the meeting. The pre-meeting is also an opportunity to ask a team member to observe the communication skills of the facilitator and be prepared to give feedback after the meeting.

At this time, the team should also create the proper environment for the family meeting. This includes a quiet room free of interruptions with ample seating, available tissues, and transferred pagers and cell phones.

The intensivist and bedside nurse should always be present at the family meeting, and it is best when the same attending can be at subsequent family meetings Their consistent dual presence provides the uniform communication from the team, can reduce anxiety in family members and the collaboration reduces ICU nurse and physician burnout [11]. For illnesses that involve a specific disease or organ system, it is important to have the specialist at the meeting who can provide the appropriate expertise.

The Pre-Meeting

A family meeting was scheduled in the family meeting room for 3 pm, after morning rounds. Thirty minutes prior to the meeting the medical team, including the MICU intensivist, the bedside nurse, the neurology attending who has been involved in the care, the case manager and 2 residents sat to discuss Mr. A’s care. The neurology team confirmed that this stroke was considered very large and would result in a level of disability that could only be cared for in a nursing home and would require both a tracheostomy and feeding tube for safe care. The bedside nurse relayed that the family had asked if Mr. A. would ever recover enough to get back to his home. The neurology team shared they did not expect much improvement at all. Given the worsening renal failure and need for dialysis the case manager reminded the team that Mr. A’s nursing home placements were limited. The team decided that the intensivist would lead the meeting as she had updated various family members on rounds for the past 4 days and would be on service for another week. The team decided that their goal for the meeting was to make sure the family understands that Mr. A’s several medical illnesses portend a poor prognosis. They recognized this may be breaking bad news to the family. They also wanted to better understand what Mr. A would have thought given this situation. The residents were asked to watch for the family’s responses when the team delivered the news.

2. Introduce Everyone

Each meeting should start with formal introductions. Even if most providers know most family members it is a polite way to start the meeting. Introducing each family member present and how they know the patient provides insight into how the family is constructed and makes decisions. For example, the entire family may defer to the daughter who introduces herself as a nurse. In other situations, although there is one legal decision maker, the family may explain that they make decisions by consensus.

Each member of the treating team should also introduce themselves. Even if the clinician has been working with the family, it is polite to be formal and give your name and role. Given the number of people the family sees every day, one should not assume that the family remembers all of the clinicians.

In teaching hospitals, providers should also help the family understand their level of training. Surrogates do not always understand the different roles or level of training between students, residents and fellows, advanced practice providers, consultants and their attending physicians. Uncertainty about the roles can lead to family members feeling as though they are receiving contradictory information. Family satisfaction decreases when multiple attending physicians are involved in a patient’s care [12]. When possible, a consistent presence among providers at family meetings is always best.

3. Ask the Family's Understanding of the Situation (Ask-Tell-Ask)

Asking the family to explain the situation in their own language reveals how well they understand the medical facts and helps the medical team determine what information will be most helpful to the family. An opening statement might be “We have all seen your dad and talked to many of his providers. It would help us all be on the same page if you can you tell me what the doctors are telling you?” Starting with the family’s understanding builds trust with the medical team as it creates an opportunity for the family to lead the meeting and indicates that the team is available to listen to their concerns. Asking surrogates for their understanding allows them to tell their story and not hear a reiteration of things they already know. Providing time for the family to share their perspective of the care elicits family’s concerns.

In a large meeting, ensure that all members of the family have an opportunity to communicate their concerns. Does a particular person do all of the talking? Are there individuals that do not speak at all? One way to further understand unspoken concerns during the meeting is to ask “I notice you have been quiet, what questions do you have that I can answer?” There may be several rounds of “asking” in order to ensure all the family members’ concerns are heard. Letting the family tell what they have heard helps the clinicians get a better idea of their health literacy. Do they explain information using technical data or jargon? Finally, as the family talks the clinicians can determine how surprising the “serious news” will be to them. For example, if the family says they know their dad is doing much worse and may die, the information to be delivered can be truncated. However if family incorrectly thinks their dad is doing better or is uncertain they will be much more surprised by the serious news.

After providing time for the family to express their understanding, tell them the information the team needs to communicate. When delivering serious news it is important to focus on the key 1 to 2 points you want the family to take away from the meeting. Typically when health care professionals talk to each other, they talk about every medical detail. Families find this amount of information overwhelming and are not sure what is most important, asking “So what does that mean?” Focusing on the “headline” helps the family focus on what you think the most important piece of information is. Studies suggest that what families most want to know is what the information means for the patient’s future and what treatments are possible. After delivering the new information, stop to allow the family space to think about what you said. If you are giving serious news, you will know they have heard what you said as they will get emotional (see next step).

Checking for understanding is the final “ask” in Ask-Tell-Ask. Begin by asking “What questions do you have?” Data in primary care has shown that patients are more likely to ask questions if you ask “what questions do you have” rather than “do you have any questions?” It is important to continue to ask this question until the family has asked all their questions. Often the family’s tough questions do not come until they get more comfortable and confident in the health care team. In cases where one family member is dominant it might also help to say “What questions do others have?” Next, using techniques like the “teach back” model the physician should check in to see what the family is taking away from the conversation. If a family understands, they can “teach back” the information accurately. This “ask” can be done in a way that does not make the family feel they are being tested: “I am not always clear when I communicate. Do you mind telling me back in your own words what you thought I said so I know we are on the same page?” This also provides an opportunity to answer any new questions that arise. Hearing the information directly from the family can allow the team to clarify any misconceptions and give insight into any emotional responses that the family might have.

4. Respond to Emotion

Discussing serious news in the ICU setting naturally leads to an emotional reaction. The clinician’s ability to notice emotional cues and respond with empathy is a key communication skill in family meetings [13]. Emotional reactions impede individual’s ability to process cognitive information and make it hard to think cognitively about what should be done next.

Physicians miss opportunities to respond to emotion in family meetings [14]. Missed opportunities lead to decreased family satisfaction and may lead to treatment decisions not consistent with the wishes of their loved ones. Empathic responses improve the family-clinician relationship and helps build trust and rapport [15]. Well- placed empathic statements may help surrogates disclose concerns that help the physician better understand the goals and values of the family and patient. Families also can more fully process cognitive information when their emotional responses have been attended to.

Physicians can develop the capacity to recognize and respond to the emotional cues family members are delivering. Intensivists should actively look for the emotions, the empathic opportunity, that are displayed by the family. This emotion is the “data” that will help lead to an empathic response. A family that just received bad news typically responds by showing emotion. Clues that emotions are present include: the family asking the same questions multiple times; using emotional words such as “sad” or “frustrated;” existential questions that do not have a cognitive answer such as “Why did God let this happen?;” or non-verbal cues like tears and hand wringing.

Sometimes the emotional responses are more difficult to recognize. Families may continue to ask for more cognitive information after hearing bad news. Someone keeps asking “Why did his kidney function worsen?” or “I thought the team said the chest x-ray looked better.” It is tempting to start answering these questions with more medical facts. However, if the question comes after bad news, it is usually an expression of frustration or sadness rather than a request for more information. Rather than giving information, it might help to acknowledge this by saying “I imagine this new is overwhelming.”

5. Highlight the Patient’s Voice

Family meetings are often used to develop new treatment plans (given that the old plans are not working). In these situations, it is essential to understand what the incapacitated patient would say if they were part of the family meeting. The surrogate’s primary role is to represent the patient’s voice. To do this, surrogates need assistance in applying their critically ill loved one’s thoughts and values to complex, possibly life limiting, situations. Surrogate decision makers struggle with the decisions’ emotional impact, as well as how to reconcile their desires with their loved one’s wishes [18]. This can lead them to make decisions that conflict with the loved one’s values [19] as well as emotional sequelae such as PTSD and depression [20].

As families reflect on their loved one’s values, conflicting desires will arise. For example, someone may have wanted to live as long as possible and also values independence. Or someone may value their ability to think clearly more than being physically well but would not want to be physically dependent on artificial life support. Exploring which values would be more important can help resolve these conflicts.

Clinicians should check for understanding while family members are identifying the values of their loved ones. Providing the family with a summary of what you have heard will help ensure a more accurate understanding of these crucial issues. A summary statement might be, “It sounds like you are saying your dad really valued his independence. He enjoyed being able to take care of his loved ones and himself. Is that right?”

6. Plan Next Steps

The family meeting serves to attend to family emotion and allow space to elicit patients’ values. Following a family meeting surrogate decision makers may be able to begin to consider the next steps in their loved one’s care. If bad news was delivered they may need space to adjust to a different future than they expected. Using an empathic statement of support “We will continue to make sure we communicate with you as we work together to plan next steps” will reassure a family that they have time and space to plan for the future.

Families vary regarding how much physician input they desire in planning next steps [21]. You can explicitly ask how the team can best help the family with decisions: “Some families like to hear the options for next steps from the team and make a decision, other families like to hear a recommendation from the team. What would be the most helpful for you?” Throughout the course of an illness a surrogate’s preference for decision making may change and clinicians should be responsive to those changing needs.

If the surrogate wants a clinician’s recommendation, 3 points are worth stressing. First, the recommendation should be personalized to this patient and his values. The goal is to reveal how the understanding of the patient’s values led to the treatment plan offered. Second, the recommendation should focus primarily on what will be done to achieve the patient’s values. Focusing on what the clinicians will do may help the family feel that the clinicians are still “trying” and not abandoning their loved one. In this case, the team will continue medical care that will help the patient regain/maintain independence. Only after talking about what will be done should the clinician point out that certain interventions will not achieve the patient’s goals and thus will not be done:

“It sounds like your father really valued his independence and that this illness has really taken that away. Knowing this, would it be helpful for me to make a recommendation for next steps?” “I think we should continue providing excellent medical care for your father in hopes he can get better and go home. One the other hand, if he gets worse, we should not use therapies such as CPR or dialysis that are unlikely to help him regain his independence.”

Finally, be concrete when planning next steps. If a time-limited trial of a therapy is proposed, make sure the family understands what a successful and unsuccessful trial will look like. Make plans to meet again on a specific date in order to ensure the family understands the progress being made. If a transition to comfort care is agreed upon, ensure support of the entire family during the next hours to days and offer services such as chaplaincy or child life specialists.

A family may not agree with the recommendation and back and forth discussion can help create a plan that is in line with their understanding of the illness. Rather than convincing, a clinician should keep an open mind about why they and the surrogate disagree. Do they have different views about the patient’s future? Did the medical team misunderstand the patient’s values? Are there emotional factors that inhibit the surrogate’s ability to attend to the discussion? It is only by learning where the disagreement is that a clinician can move the conversation forward.

A surrogate may ask about a therapy that is not beneficial or may increase distress to the patient. The use of “I wish” or “I worry” statements can be helpful at these points. These specific phrases recognize the surrogate’s desire to do more but also imply that the therapies are not helpful.

“I wish that his ability to communicate and tell you what he wants would get better with a little more time as well.”

“I worry that waiting 2 more weeks for improvement will actually cause complications to occur.”

7. Reflect

Family meetings have an impact on both the family and the medical team. Following the meeting, a short debriefing with the clinical team can be helpful. Summarizing the events of the meeting ensures clarity about the treatment plan going forward. It provides team members a chance to discuss conflicts that may have arisen. It allows the participants in the meeting to reflect on what communication skills they used and how they can improve their skills going forward.

Conclusion

Family meetings with surrogate decision makers must navigate multiple agendas of the family and providers. The goal of excellent communication with surrogates in an ICU should be to understand the patient’s goals and values and seek to make treatment plans that align with their perspective. This talking map provides a conceptual framework for physicians to guide a family through these conversations. The framework creates an opportunity to focus on the patient’s values and preferences for care while allowing space to attend to emotional responses to reduce the distress inherent in surrogate decision-making. Practicing the behaviors demonstrated in the talking map may increase clinician skill during difficult conversations. Improving communication with surrogate decision makers will increase the support we offer to critically ill patients and their loved ones.

Corresponding author: Jessica McFarlin, MD, jessmcfarlin@gmail.com.

Funding/support: Dr. Arnold receives support though the Leo H. Criep Chair in Patient Care.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Department of Neurology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC (Dr. McFarlin), the Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA (Dr. Tulsky), Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (Dr. Back), and Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Arnold).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the use of a cognitive map for navigating family meetings with surrogate decision makers of patients in an intensive care unit.

- Methods: Descriptive report and discussion using an illustrative case to outline the steps in the cognitive map.

- Results: The use of cognitive maps has improved the ability of physicians to efficiently perform a specific communication skill. During a “goals of care” conversation, the cognitive map follows these steps: (1) Gather the clinical team for a pre-meeting, (2) Introduce everyone, (3) Use the “ask-tell-ask” strategy to communicate information, (4) Respond to emotion, (5) Highlight the patient’s voice, (6) Plan next steps, (7) Reflect on the meeting with the team. Providing this map of key communication skills will help faculty teach learners the core components of a family meeting.

- Conclusion: Practicing the behaviors demonstrated in the cognitive map may increase clinician skill during difficult conversations. Improving communication with surrogate decision makers will increase the support we offer to critically ill patients and their loved ones.

Key words: intensive care unit; communication; family meeting; critical illness; decision making; end of life care.

Family members of patients in the ICU value high-quality communication with the medical team. In fact, family members report that physicians’ communication skills are often more important than their medical skills [1]. Multiple professional societies, including the American Thoracic Society and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, define communication with families as a key component of high-quality critical care. Effective physician-patient communication improves measureable outcomes including decreased ICU length of stay [2] and may reduce distress amongst patients’ families [3]. The American College of Chest Physicians position statement on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Patients with Cardiopulmonary Diseases urges physicians to develop curricula that incorporate interpersonal communication skills into training [4].

Unfortunately, such high-quality communication is not the norm. Surrogate decision makers are often displeased with the frequency of communication, the limited availability of attending physicians, and report feeling excluded from discussions [5]. When family meetings do occur, surrogate decision makers report inadequate understanding of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plans [6].

Physicians also find family meetings difficult. Intensivists worry that high-quality family meetings are time consuming and difficult to do in a busy ICU [7]. Critical care fellows report not feeling adequately trained to conduct family meetings [8]. It makes sense that untrained clinicians would want to avoid a conversation that is emotionally charged, particularly if one is unsure how to respond effectively.

The Case of Mr. A

Thomas A. is a 79-year-old man admitted to the medical intensive care unit 7 days earlier with a large left middle cerebral artery territory infarction. Given his decreased mental status, on admission he was intubated for airway protection. He is awake but aphasic and unable to follow any commands or move his right side. The neurology consultants do not feel this will improve. He has significant secretions and episodes of hypoxia. He has also developed acute on chronic kidney injury and may need to start dialysis. The social worker explains that his need for dialysis limits his placement options and that he will not be able to be discharged to home. Given his lack of improvement the team is concerned he will need a tracheostomy and feeding tube placed in order to safely continue this level of care. A family meeting is arranged to understand Mr. A’s goals of care.

Talking Map Basics

Before each step is discussed in detail, some definitions are needed. “Family” can be defined as anyone important enough, biologically related or not, to be present at a conversation with a clinician [10]. Second, a “family meeting” is a planned event between the family and interdisciplinary members of the ICU team as well as any other health care providers who have been involved in the patient’s care. The meeting takes place in a private space and at a time that is scheduled with the families’ needs in mind. Thus it is different from having families present on rounds or one-off meetings with particular clinicians.

Goals of care meetings are typically held when, in the clinicians’ view, the current treatments are not achieving the previously stated goals. Thus, the meeting has 2 purposes: first, to give the family the bad news that the current plan is not working and second, to develop a new plan based on the patient’s values. The family’s job, as surrogate decision maker, is to provide information about what would be most important to the patient. The clinician’s job is to suggest treatment plans that have the best probability of matching the patient’s values.

Not all of these tasks need be done at once. Some families will not be able to move from hearing bad news to making a decision without having time to first reflect and grieve. Others will need to confer with other family members privately before deciding on a plan. In many cases, a time-limited trial may be the right option with a plan for subsequent meetings. Given this, we recommend checking in with the family between each step to ensure that they feel safe moving ahead. For example, one might ask “Is it OK if we talk about what happens next?”

Talking Map Steps in Detail

1. Gather the Clinical Team for a Pre-Meeting

ICU care involves a large interdisciplinary care team. A “meeting before the meeting” with the entire clinical team is an opportunity to reach consensus on prognosis and therapeutic options, share prior interactions with family, and determine goals for the family meeting. It is also helpful to clarify team members’ roles at the meeting and to choose a primary facilitator. All of this helps to ensure that the family receives a consistent message during the meeting. The pre-meeting is also an opportunity to ask a team member to observe the communication skills of the facilitator and be prepared to give feedback after the meeting.

At this time, the team should also create the proper environment for the family meeting. This includes a quiet room free of interruptions with ample seating, available tissues, and transferred pagers and cell phones.

The intensivist and bedside nurse should always be present at the family meeting, and it is best when the same attending can be at subsequent family meetings Their consistent dual presence provides the uniform communication from the team, can reduce anxiety in family members and the collaboration reduces ICU nurse and physician burnout [11]. For illnesses that involve a specific disease or organ system, it is important to have the specialist at the meeting who can provide the appropriate expertise.

The Pre-Meeting

A family meeting was scheduled in the family meeting room for 3 pm, after morning rounds. Thirty minutes prior to the meeting the medical team, including the MICU intensivist, the bedside nurse, the neurology attending who has been involved in the care, the case manager and 2 residents sat to discuss Mr. A’s care. The neurology team confirmed that this stroke was considered very large and would result in a level of disability that could only be cared for in a nursing home and would require both a tracheostomy and feeding tube for safe care. The bedside nurse relayed that the family had asked if Mr. A. would ever recover enough to get back to his home. The neurology team shared they did not expect much improvement at all. Given the worsening renal failure and need for dialysis the case manager reminded the team that Mr. A’s nursing home placements were limited. The team decided that the intensivist would lead the meeting as she had updated various family members on rounds for the past 4 days and would be on service for another week. The team decided that their goal for the meeting was to make sure the family understands that Mr. A’s several medical illnesses portend a poor prognosis. They recognized this may be breaking bad news to the family. They also wanted to better understand what Mr. A would have thought given this situation. The residents were asked to watch for the family’s responses when the team delivered the news.

2. Introduce Everyone

Each meeting should start with formal introductions. Even if most providers know most family members it is a polite way to start the meeting. Introducing each family member present and how they know the patient provides insight into how the family is constructed and makes decisions. For example, the entire family may defer to the daughter who introduces herself as a nurse. In other situations, although there is one legal decision maker, the family may explain that they make decisions by consensus.

Each member of the treating team should also introduce themselves. Even if the clinician has been working with the family, it is polite to be formal and give your name and role. Given the number of people the family sees every day, one should not assume that the family remembers all of the clinicians.

In teaching hospitals, providers should also help the family understand their level of training. Surrogates do not always understand the different roles or level of training between students, residents and fellows, advanced practice providers, consultants and their attending physicians. Uncertainty about the roles can lead to family members feeling as though they are receiving contradictory information. Family satisfaction decreases when multiple attending physicians are involved in a patient’s care [12]. When possible, a consistent presence among providers at family meetings is always best.

3. Ask the Family's Understanding of the Situation (Ask-Tell-Ask)

Asking the family to explain the situation in their own language reveals how well they understand the medical facts and helps the medical team determine what information will be most helpful to the family. An opening statement might be “We have all seen your dad and talked to many of his providers. It would help us all be on the same page if you can you tell me what the doctors are telling you?” Starting with the family’s understanding builds trust with the medical team as it creates an opportunity for the family to lead the meeting and indicates that the team is available to listen to their concerns. Asking surrogates for their understanding allows them to tell their story and not hear a reiteration of things they already know. Providing time for the family to share their perspective of the care elicits family’s concerns.

In a large meeting, ensure that all members of the family have an opportunity to communicate their concerns. Does a particular person do all of the talking? Are there individuals that do not speak at all? One way to further understand unspoken concerns during the meeting is to ask “I notice you have been quiet, what questions do you have that I can answer?” There may be several rounds of “asking” in order to ensure all the family members’ concerns are heard. Letting the family tell what they have heard helps the clinicians get a better idea of their health literacy. Do they explain information using technical data or jargon? Finally, as the family talks the clinicians can determine how surprising the “serious news” will be to them. For example, if the family says they know their dad is doing much worse and may die, the information to be delivered can be truncated. However if family incorrectly thinks their dad is doing better or is uncertain they will be much more surprised by the serious news.

After providing time for the family to express their understanding, tell them the information the team needs to communicate. When delivering serious news it is important to focus on the key 1 to 2 points you want the family to take away from the meeting. Typically when health care professionals talk to each other, they talk about every medical detail. Families find this amount of information overwhelming and are not sure what is most important, asking “So what does that mean?” Focusing on the “headline” helps the family focus on what you think the most important piece of information is. Studies suggest that what families most want to know is what the information means for the patient’s future and what treatments are possible. After delivering the new information, stop to allow the family space to think about what you said. If you are giving serious news, you will know they have heard what you said as they will get emotional (see next step).

Checking for understanding is the final “ask” in Ask-Tell-Ask. Begin by asking “What questions do you have?” Data in primary care has shown that patients are more likely to ask questions if you ask “what questions do you have” rather than “do you have any questions?” It is important to continue to ask this question until the family has asked all their questions. Often the family’s tough questions do not come until they get more comfortable and confident in the health care team. In cases where one family member is dominant it might also help to say “What questions do others have?” Next, using techniques like the “teach back” model the physician should check in to see what the family is taking away from the conversation. If a family understands, they can “teach back” the information accurately. This “ask” can be done in a way that does not make the family feel they are being tested: “I am not always clear when I communicate. Do you mind telling me back in your own words what you thought I said so I know we are on the same page?” This also provides an opportunity to answer any new questions that arise. Hearing the information directly from the family can allow the team to clarify any misconceptions and give insight into any emotional responses that the family might have.

4. Respond to Emotion

Discussing serious news in the ICU setting naturally leads to an emotional reaction. The clinician’s ability to notice emotional cues and respond with empathy is a key communication skill in family meetings [13]. Emotional reactions impede individual’s ability to process cognitive information and make it hard to think cognitively about what should be done next.

Physicians miss opportunities to respond to emotion in family meetings [14]. Missed opportunities lead to decreased family satisfaction and may lead to treatment decisions not consistent with the wishes of their loved ones. Empathic responses improve the family-clinician relationship and helps build trust and rapport [15]. Well- placed empathic statements may help surrogates disclose concerns that help the physician better understand the goals and values of the family and patient. Families also can more fully process cognitive information when their emotional responses have been attended to.

Physicians can develop the capacity to recognize and respond to the emotional cues family members are delivering. Intensivists should actively look for the emotions, the empathic opportunity, that are displayed by the family. This emotion is the “data” that will help lead to an empathic response. A family that just received bad news typically responds by showing emotion. Clues that emotions are present include: the family asking the same questions multiple times; using emotional words such as “sad” or “frustrated;” existential questions that do not have a cognitive answer such as “Why did God let this happen?;” or non-verbal cues like tears and hand wringing.

Sometimes the emotional responses are more difficult to recognize. Families may continue to ask for more cognitive information after hearing bad news. Someone keeps asking “Why did his kidney function worsen?” or “I thought the team said the chest x-ray looked better.” It is tempting to start answering these questions with more medical facts. However, if the question comes after bad news, it is usually an expression of frustration or sadness rather than a request for more information. Rather than giving information, it might help to acknowledge this by saying “I imagine this new is overwhelming.”

5. Highlight the Patient’s Voice

Family meetings are often used to develop new treatment plans (given that the old plans are not working). In these situations, it is essential to understand what the incapacitated patient would say if they were part of the family meeting. The surrogate’s primary role is to represent the patient’s voice. To do this, surrogates need assistance in applying their critically ill loved one’s thoughts and values to complex, possibly life limiting, situations. Surrogate decision makers struggle with the decisions’ emotional impact, as well as how to reconcile their desires with their loved one’s wishes [18]. This can lead them to make decisions that conflict with the loved one’s values [19] as well as emotional sequelae such as PTSD and depression [20].

As families reflect on their loved one’s values, conflicting desires will arise. For example, someone may have wanted to live as long as possible and also values independence. Or someone may value their ability to think clearly more than being physically well but would not want to be physically dependent on artificial life support. Exploring which values would be more important can help resolve these conflicts.

Clinicians should check for understanding while family members are identifying the values of their loved ones. Providing the family with a summary of what you have heard will help ensure a more accurate understanding of these crucial issues. A summary statement might be, “It sounds like you are saying your dad really valued his independence. He enjoyed being able to take care of his loved ones and himself. Is that right?”

6. Plan Next Steps

The family meeting serves to attend to family emotion and allow space to elicit patients’ values. Following a family meeting surrogate decision makers may be able to begin to consider the next steps in their loved one’s care. If bad news was delivered they may need space to adjust to a different future than they expected. Using an empathic statement of support “We will continue to make sure we communicate with you as we work together to plan next steps” will reassure a family that they have time and space to plan for the future.

Families vary regarding how much physician input they desire in planning next steps [21]. You can explicitly ask how the team can best help the family with decisions: “Some families like to hear the options for next steps from the team and make a decision, other families like to hear a recommendation from the team. What would be the most helpful for you?” Throughout the course of an illness a surrogate’s preference for decision making may change and clinicians should be responsive to those changing needs.

If the surrogate wants a clinician’s recommendation, 3 points are worth stressing. First, the recommendation should be personalized to this patient and his values. The goal is to reveal how the understanding of the patient’s values led to the treatment plan offered. Second, the recommendation should focus primarily on what will be done to achieve the patient’s values. Focusing on what the clinicians will do may help the family feel that the clinicians are still “trying” and not abandoning their loved one. In this case, the team will continue medical care that will help the patient regain/maintain independence. Only after talking about what will be done should the clinician point out that certain interventions will not achieve the patient’s goals and thus will not be done:

“It sounds like your father really valued his independence and that this illness has really taken that away. Knowing this, would it be helpful for me to make a recommendation for next steps?” “I think we should continue providing excellent medical care for your father in hopes he can get better and go home. One the other hand, if he gets worse, we should not use therapies such as CPR or dialysis that are unlikely to help him regain his independence.”

Finally, be concrete when planning next steps. If a time-limited trial of a therapy is proposed, make sure the family understands what a successful and unsuccessful trial will look like. Make plans to meet again on a specific date in order to ensure the family understands the progress being made. If a transition to comfort care is agreed upon, ensure support of the entire family during the next hours to days and offer services such as chaplaincy or child life specialists.

A family may not agree with the recommendation and back and forth discussion can help create a plan that is in line with their understanding of the illness. Rather than convincing, a clinician should keep an open mind about why they and the surrogate disagree. Do they have different views about the patient’s future? Did the medical team misunderstand the patient’s values? Are there emotional factors that inhibit the surrogate’s ability to attend to the discussion? It is only by learning where the disagreement is that a clinician can move the conversation forward.

A surrogate may ask about a therapy that is not beneficial or may increase distress to the patient. The use of “I wish” or “I worry” statements can be helpful at these points. These specific phrases recognize the surrogate’s desire to do more but also imply that the therapies are not helpful.

“I wish that his ability to communicate and tell you what he wants would get better with a little more time as well.”

“I worry that waiting 2 more weeks for improvement will actually cause complications to occur.”

7. Reflect

Family meetings have an impact on both the family and the medical team. Following the meeting, a short debriefing with the clinical team can be helpful. Summarizing the events of the meeting ensures clarity about the treatment plan going forward. It provides team members a chance to discuss conflicts that may have arisen. It allows the participants in the meeting to reflect on what communication skills they used and how they can improve their skills going forward.

Conclusion

Family meetings with surrogate decision makers must navigate multiple agendas of the family and providers. The goal of excellent communication with surrogates in an ICU should be to understand the patient’s goals and values and seek to make treatment plans that align with their perspective. This talking map provides a conceptual framework for physicians to guide a family through these conversations. The framework creates an opportunity to focus on the patient’s values and preferences for care while allowing space to attend to emotional responses to reduce the distress inherent in surrogate decision-making. Practicing the behaviors demonstrated in the talking map may increase clinician skill during difficult conversations. Improving communication with surrogate decision makers will increase the support we offer to critically ill patients and their loved ones.

Corresponding author: Jessica McFarlin, MD, jessmcfarlin@gmail.com.

Funding/support: Dr. Arnold receives support though the Leo H. Criep Chair in Patient Care.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Hickey M. What are the needs of families of critically ill patients? A review of the literature since 1976. Heart Lung 1990;19:401–15.

2. Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA, Barker LK, et al. Changing culture around end-of-life care in the trauma intensive care unit. J Trauma 2008;64:1587–93.

3. Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2007;356:469–78.

4. Selecky PA, Eliasson AH, Hall RI, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with cardiopulmonary diseases. Chest 2005;128:3599–610.

5. Henrich NJ, Dodek P, Heyland D, et al. Qualitative analysis of an intensive care unit family satisfaction survey. Crit Care Med 2011;39:1000–5.

6. Azoulet E, Chevret S, Leleu G, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med 2000;28:3044–9.

7. Curtis JR. Communicating about end-of-life care with patients and families in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin 2004;20:363–80.

8. Hope AA, Hsieh SJ, Howes JM, et al. Let’s talk critical. Development and evaluation of a communication skills training program for critical care fellows. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2015;12:505–11.

9. Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Efficacy of communication skills training for giving bad news and discussing transitions to palliative care. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:453–60.

10. Vital Talk. Conduct a family conference. Accessed 27 June 2016 at www.vitaltalk.org/clinicians/family.

11. Kramer M, Schmalenberg C. Securing “good” nurse/physician relationships. Nurs Manage 2003;34:34–8.

12. Johnson D, Wilson M, Cavanaugh B, et al. Measuring the ability to meet family needs in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 1998;26:266–71.

13. Back AL, Arnold RM. “Isn’t there anything more you can do?’’: when empathic statements work, and when they don’t. J Palliat Med 2013;16:1429–32.

14. Curtis JR, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD. Missed opportunities during family conferences about end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:844–9.

15. Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol 2007;36:5748–52.

16. Back AL, Arnold RM, Tulsky JA. Mastering communication with seriously ill patients: balancing honesty with empathy and hope. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009.

17. Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin 2005;55:164–77.

18. Schenker Y, White D, Crowley-Matoka M, et al. “It hurts to know…and it helps”: exploring how surrogates in the ICU cope with prognostic information. J Palliat Med 2013;16:243–9.

19. Scheunemann LP, Arnold RM, White DB. The facilitated values history: helping surrogates make authentic decisions for incapacitated patients with advanced illness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2012;186:480–6.

20. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:987–94.

21. White DB, Braddock CH, Bereknyei et al. Toward shared decision making at the end of life in intensive care units: opportunities for improvement. Arch Intern Med 2007;167:461–7.

1. Hickey M. What are the needs of families of critically ill patients? A review of the literature since 1976. Heart Lung 1990;19:401–15.

2. Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA, Barker LK, et al. Changing culture around end-of-life care in the trauma intensive care unit. J Trauma 2008;64:1587–93.

3. Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med 2007;356:469–78.

4. Selecky PA, Eliasson AH, Hall RI, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with cardiopulmonary diseases. Chest 2005;128:3599–610.

5. Henrich NJ, Dodek P, Heyland D, et al. Qualitative analysis of an intensive care unit family satisfaction survey. Crit Care Med 2011;39:1000–5.

6. Azoulet E, Chevret S, Leleu G, et al. Half the families of intensive care unit patients experience inadequate communication with physicians. Crit Care Med 2000;28:3044–9.