User login

Associations of Physician Empathy with Patient Anxiety and Ratings of Communication in Hospital Admission Encounters

Admission to a hospital can be a stressful event,1,2 and patients report having many concerns at the time of hospital admission.3 Over the last 20 years, the United States has widely adopted the hospitalist model of inpatient care. Although this model has clear benefits, it also has the potential to contribute to patient stress, as hospitalized patients generally lack preexisting relationships with their inpatient physicians.4,5 In this changing hospital environment, defining and promoting effective medical communication has become an essential goal of both individual practitioners and medical centers.

Successful communication and strong therapeutic relationships with physicians support patients’ coping with illness-associated stress6,7 as well as promote adherence to medical treatment plans.8 Empathy serves as an important building block of patient-centered communication and encourages a strong therapeutic alliance.9 Studies from primary care, oncology, and intensive care unit (ICU) settings indicate that physician empathy is associated with decreased emotional distress,10,11 improved ratings of communication,12 and even better medical outcomes.13

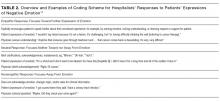

Prior work has shown that hospitalists, like other clinicians, underutilize empathy as a tool in their daily interactions with patients.14-16 Our prior qualitative analysis of audio-recorded hospitalist-patient admission encounters indicated that how hospitalists respond to patient expressions of negative emotion influences relationships with patients and alignment around care plans.17 To determine whether empathic communication is associated with patient-reported outcomes in the hospitalist model, we quantitatively analyzed coded admission encounters and survey data to examine the association between hospitalists’ responses to patient expressions of negative emotion (anxiety, sadness, and anger) and patient anxiety and ratings of communication. Given the often-limited time hospitalists have to complete admission encounters, we also examined the association between response to emotion and encounter length.

METHODS

We analyzed data collected as part of an observational study of hospitalist-patient communication during hospital admission encounters14 to assess the association between the way physicians responded to patient expressions of negative emotion and patient anxiety, ratings of communication in the encounter, and encounter length. We collected data between August 2008 and March 2009 on the general medical service at 2 urban hospitals that are part of an academic medical center. Participants were attending hospitalists (not physician trainees), and patients admitted under participating hospitalists’ care who were able to communicate verbally in English and provide informed consent for the study. The institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco approved the study; physician and patient participants provided written informed consent.

Enrollment and data collection has been described previously.17 Our cohort for this analysis included 76 patients of 27 physicians who completed encounter audio recordings and pre- and postencounter surveys. Following enrollment, patients completed a preencounter survey to collect demographic information and to measure their baseline anxiety via the State Anxiety Scale (STAI-S), which assesses transient anxious mood using 20 items answered on a 4-point scale for a final score range of 20 to 80.10,18,19 We timed and audio-recorded admission encounters. Encounter recordings were obtained solely from patient interactions with attending hospitalists and did not take into account the time patients may have spent with other physicians, including trainees. After the encounter, patients completed postencounter surveys, which included the STAI-S and patients’ ratings of communication during the encounter. To rate communication, patients responded to 7 items on a 0- to 10-point scale that were derived from previous work (Table 1)12,20,21; the anchors were “not at all” and “completely.” To identify patients with serious illness, which we used as a covariate in regression models, we asked physicians on a postencounter survey whether or not they “would be surprised by this patient’s death or admission to the ICU in the next year.”22

We considered physician as a clustering variable in the calculation of robust standard errors for all models. In addition, we included in each model covariates that were associated with the outcome at P ≤ 0.10, including patient gender, patient age, serious illness,22 preencounter anxiety, encounter length, and hospital. We considered P values < 0.05 to be statistically significant. We used Stata SE 13 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

We analyzed data from admission encounters with 76 patients (consent rate 63%) and 27 hospitalists (consent rate 91%). Their characteristics are shown in Table 3. Median encounter length was 19 minutes (mean 21 minutes, range 3-68). Patients expressed negative emotion in 190 instances across all encounters; median number of expressions per encounter was 1 (range 0-14). Hospitalists responded empathically to 32% (n = 61) of the patient expressions, neutrally to 43% (n = 81), and nonempathically to 25% (n = 48).

The STAI-S was normally distributed. The mean preencounter STAI-S score was 39 (standard deviation [SD] 8.9). Mean postencounter STAI-S score was 38 (SD 10.7). Mean change in anxiety over the course of the encounter, calculated as the postencounter minus preencounter mean was −1.2 (SD 7.6). Table 1 shows summary statistics for the patient ratings of communication items. All items were rated highly. Across the items, between 51% and 78% of patients rated the highest score of 10.

Across the range of frequencies of emotional expressions per encounter in our data set (0-14 expressions), each additional empathic hospitalist response was associated with a 1.65-point decrease in the STAI-S (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-2.82). We did not find significant associations between changes in the STAI-S and the number of neutral hospitalist responses (−0.65 per response; 95% CI, −1.67-0.37) or nonempathic hospitalist responses (0.61 per response; 95% CI, −0.88-2.10).

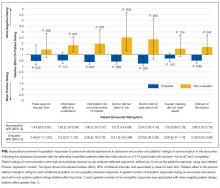

In addition, nonempathic responses were associated with more negative ratings of communication for 5 of the 7 items: ease of understanding information, covering points of interest, the doctor listening, the doctor caring, and trusting the doctor. For example, for the item “I felt this doctor cared about me,” each nonempathic hospitalist response was associated with a more than doubling of negative patient ratings (aRE: 2.3; 95% CI, 1.32-4.16). Neutral physician responses to patient expressions of negative emotion were associated with less negative patient ratings for 2 of the items: covering points of interest (aRE 0.68; 95% CI, 0.51-0.90) and trusting the doctor (aRE: 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.99).

We did not find a statistical association between encounter length and the number of empathic hospitalist responses in the encounter (percent change in encounter length per response [PC]: 1%; 95% CI, −8%-10%) or the number of nonempathic responses (PC: 18%; 95% CI, −2%-42%). We did find a statistically significant association between the number of neutral responses and encounter length (PC: 13%; 95% CI, 3%-24%), corresponding to 2.5 minutes of additional encounter time per neutral response for the median encounter length of 19 minutes.

DISCUSSION

Our study set out to measure how hospitalists responded to expressions of negative emotion during admission encounters with patients and how those responses correlated with patient anxiety, ratings of communication, and encounter length. We found that empathic responses were associated with diminishing patient anxiety after the visit, as well as with better ratings of several domains of hospitalist communication. Moreover, nonempathic responses to negative emotion were associated with more strongly negative ratings of hospitalist communication. Finally, while clinicians may worry that encouraging patients to speak further about emotion will result in excessive visit lengths, we did not find a statistical association between empathic responses and encounter duration. To our knowledge, this is the first study to indicate an association between empathy and patient anxiety and communication ratings within the hospitalist model, which is rapidly becoming the predominant model for providing inpatient care in the United States.4,5

As in oncologic care, anxiety is an emotion commonly confronted by clinicians meeting admitted medical patients for the first time. Studies show that not only do patient anxiety levels remain high throughout a hospital course, patients who experience higher levels of anxiety tend to stay longer in the hospital.1,2,27-30 But unlike oncologic care or other therapy provided in an outpatient setting, the hospitalist model does not facilitate “continuity” of care, or the ability to care for the same patients over a long period of time. This reality of inpatient care makes rapid, effective rapport-building critical to establishing strong physician-patient relationships. In this setting, a simple communication tool that is potentially able to reduce inpatients’ anxiety could have a meaningful impact on hospitalist-provided care and patient outcomes.

In terms of the magnitude of the effect of empathic responses, the clinical significance of a 1.65-point decrease in the STAI-S anxiety score is not precisely clear. A prior study that examined the effect of music therapy on anxiety levels in patients with cancer found an average anxiety reduction of approximately 9.5 units on the STAIS-S scale after sensitivity analysis, suggesting a rather large meaningful effect size.31 Given we found a reduction of 1.65 points for each empathic response, however, with a range of 0-14 negative emotions expressed over a median 19-minute encounter, there is opportunity for hospitalists to achieve a clinically significant decrease in patient anxiety during an admission encounter. The potential to reduce anxiety is extended further when we consider that the impact of an empathic response may apply not just to the admission encounter alone but also to numerous other patient-clinician interactions over the course of a hospitalization.

A healthy body of communication research supports the associations we found in our study between empathy and patient ratings of communication and physicians. Families in ICU conferences rate communication more positively when physicians express empathy,12 and a number of studies indicate an association between empathy and patient satisfaction in outpatient settings.8 Given the associations we found with negative ratings on the items in our study, promoting empathic responses to expressions of emotion and, more importantly, stressing avoidance of nonempathic responses may be relevant efforts in working to improve patient satisfaction scores on surveys reporting “top box” percentages, such as Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). More notably, evidence indicates that empathy has positive impacts beyond satisfaction surveys, such as adherence, better diagnostic and clinical outcomes, and strengthening of patient enablement.8Not all hospitalist responses to emotion were associated with patient ratings across the 7 communication items we assessed. For example, we did not find an association between how physicians responded to patient expressions of negative emotion and patient perception that enough time was spent in the visit or the degree to which talking with the doctor met a patient’s overall needs. It follows logically, and other research supports, that empathy would influence patient ratings of physician caring and trust,32 whereas other communication factors we were unable to measure (eg, physician body language, tone, and use of jargon and patient health literacy and primary language) may have a more significant association with patient ratings of the other items we assessed.

In considering the clinical application of our results, it is important to note that communication skills, including responding empathically to patient expressions of negative emotion, can be imparted through training in the same way as abdominal examination or electrocardiogram interpretation skills.33-35 However, training of hospitalists in communication skills requires time and some financial investment on the part of the physician, their hospital or group, or, ideally, both. Effective training methods, like those for other skill acquisition, involve learner-centered teaching and practicing skills with role-play and feedback.36 Given the importance of a learner-centered approach, learning would likely be better received and more effective if it was tailored to the specific needs and patient scenarios commonly encountered by hospitalist physicians. As these programs are developed, it will be important to assess the impact of any training on the patient-reported outcomes we assessed in this observational study, along with clinical outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. First, we were only able to evaluate whether hospitalists verbally responded to patient emotion and were thus not able to account for nonverbal empathy such as facial expressions, body language, or voice tone. Second, given our patient consent rate of 63%, patients who agreed to participate in the study may have had different opinions than those who declined to participate. Also, hospitalists and patients may have behaved differently as a result of being audio recorded. We only included patients who spoke English, and our patient population was predominately non-Hispanic white. Patients who spoke other languages or came from other cultural backgrounds may have had different responses. Third, we did not use a single validated scale for patient ratings of communication, and multiple analyses increase our risk of finding statistically significant associations by chance. The skewing of the communication rating items toward high scores may also have led to our results being driven by outliers, although the model we chose for analysis does penalize for this. Furthermore, our sample size was small, leading to wide CIs and potential for lack of statistical associations due to insufficient power. Our findings warrant replication in larger studies. Fourth, the setting of our study in an academic center may affect generalizability. Finally, the age of our data (collected between 2008 and 2009) is also a limitation. Given a recent focus on communication and patient experience since the initiation of HCAHPS feedback, a similar analysis of empathy and communication methods now may result in different outcomes.

In conclusion, our results suggest that enhancing hospitalists’ empathic responses to patient expressions of negative emotion could decrease patient anxiety and improve patients’ perceptions of (and thus possibly their relationships with) hospitalists, without sacrificing efficiency. Future work should focus on tailoring and implementing communication skills training programs for hospitalists and evaluating the impact of training on patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere thanks to the patients and physicians who participated in this study. Dr. Anderson was funded by the National Palliative Care Research Center and the University of California, San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute Career Development Program, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant number 5 KL2 RR024130-04. Project costs were funded by a grant from the University of California, San Francisco Academic Senate.

Disclosure

All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of this manuscript. This submission is not under review by any other publication. Wendy Anderson received funding for this project from the National Palliative Care Research Center, University of California San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NIH grant number 5KL2RR024130-04), and the University of San Francisco Academic Senate [From Section 2 of Author Disclosure Form]. Andy Auerbach has a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute research grant in development [From Section 3 of the Author Disclosure Form].

1. Walker FB, Novack DH, Kaiser DL, Knight A, Oblinger P. Anxiety and depression among medical and surgical patients nearing hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 1987;2(2):99-101. PubMed

2. Castillo MI, Cooke M, Macfarlane B, Aitken LM. Factors associated with anxiety in critically ill patients: A prospective observational cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;60:225-233. PubMed

3. Anderson WG, Winters K, Auerbach AD. Patient concerns at hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1399-1400. PubMed

4. Kuo Y-F, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102-1112. PubMed

5. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. PubMed

6. Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, et al. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: the Human Connection Scale. Cancer. 2009;115(14):3302-3311. PubMed

7. Huff NG, Nadig N, Ford DW, Cox CE. Therapeutic Alliance between the Caregivers of Critical Illness Survivors and Intensive Care Unit Clinicians. [published correction appears in Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(4):576]. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1646-1653. PubMed

8. Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):e76-e84. PubMed

9. Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267. PubMed

10. Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):371-379. PubMed

11. Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(17):1877-1884. PubMed

12. Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Goss CH, Curtis JR. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1679-1685. PubMed

13. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):359-364. PubMed

14. Anderson WG, Winters K, Arnold RM, Puntillo KA, White DB, Auerbach AD. Studying physician-patient communication in the acute care setting: the hospitalist rapport study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):275-279. PubMed

15. Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5748-5752. PubMed

16. Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277(8):678-682. PubMed

17. Adams K, Cimino JEW, Arnold RM, Anderson WG. Why should I talk about emotion? Communication patterns associated with physician discussion of patient expressions of negative emotion in hospital admission encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(1):44-50. PubMed

18. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63 Suppl 11:S467-S472. PubMed

19. Speilberger C, Ritterband L, Sydeman S, Reheiser E, Unger K. Assessment of emotional states and personality traits: measuring psychological vital signs. In: Butcher J, editor. Clinical personality assessment: practical approaches. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995.

20. Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36(5):728-739. PubMed

21. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987-994. PubMed

22. Lynn J. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Serving patients who may die soon and their families: the role of hospice and other services. JAMA. 2001;285(7):925-932. PubMed

23. Kennifer SL, Alexander SC, Pollak KI, et al. Negative emotions in cancer care: do oncologists’ responses depend on severity and type of emotion? Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(1):51-56. PubMed

24. Butow PN, Brown RF, Cogar S, Tattersall MHN, Dunn SM. Oncologists’ reactions to cancer patients’ verbal cues. Psychooncology. 2002;11(1):47-58. PubMed

25. Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA. 2000;284(8):1021-1027. PubMed

26. Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37-46.

27. Fulop G. Anxiety disorders in the general hospital setting. Psychiatr Med. 1990;8(3):187-195. PubMed

28. Gerson S, Mistry R, Bastani R, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety (MHI) following acute medical/surgical hospitalization and post-discharge psychiatric diagnoses (DSM) in 839 geriatric US veterans. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(12):1155-1167. PubMed

29. Kathol RG, Wenzel RP. Natural history of symptoms of depression and anxiety during inpatient treatment on general medicine wards. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(3):287-293. PubMed

30. Unsal A, Unaldi C, Baytemir C. Anxiety and depression levels of inpatients in the city centre of Kirşehir in Turkey. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(4):411-418. PubMed

31. Bradt J, Dileo C, Grocke D, Magill L. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. [Update appears in Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(8):CD006911] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD006911. PubMed

32. Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):237-251. PubMed

33. Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(9):593-601. PubMed

34. Bays AM, Engelberg RA, Back AL, et al. Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: evaluation of a small-group, simulated patient intervention. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(2):159-166. PubMed

35. Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al. Effect of a Patient-Centered Communication Intervention on Oncologist-Patient Communication, Quality of Life, and Health Care Utilization in Advanced Cancer: The VOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):92-100. PubMed

36. Berkhof M, van Rijssen HJ, Schellart AJM, Anema JR, van der Beek AJ. Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(2):152-162. PubMed

Admission to a hospital can be a stressful event,1,2 and patients report having many concerns at the time of hospital admission.3 Over the last 20 years, the United States has widely adopted the hospitalist model of inpatient care. Although this model has clear benefits, it also has the potential to contribute to patient stress, as hospitalized patients generally lack preexisting relationships with their inpatient physicians.4,5 In this changing hospital environment, defining and promoting effective medical communication has become an essential goal of both individual practitioners and medical centers.

Successful communication and strong therapeutic relationships with physicians support patients’ coping with illness-associated stress6,7 as well as promote adherence to medical treatment plans.8 Empathy serves as an important building block of patient-centered communication and encourages a strong therapeutic alliance.9 Studies from primary care, oncology, and intensive care unit (ICU) settings indicate that physician empathy is associated with decreased emotional distress,10,11 improved ratings of communication,12 and even better medical outcomes.13

Prior work has shown that hospitalists, like other clinicians, underutilize empathy as a tool in their daily interactions with patients.14-16 Our prior qualitative analysis of audio-recorded hospitalist-patient admission encounters indicated that how hospitalists respond to patient expressions of negative emotion influences relationships with patients and alignment around care plans.17 To determine whether empathic communication is associated with patient-reported outcomes in the hospitalist model, we quantitatively analyzed coded admission encounters and survey data to examine the association between hospitalists’ responses to patient expressions of negative emotion (anxiety, sadness, and anger) and patient anxiety and ratings of communication. Given the often-limited time hospitalists have to complete admission encounters, we also examined the association between response to emotion and encounter length.

METHODS

We analyzed data collected as part of an observational study of hospitalist-patient communication during hospital admission encounters14 to assess the association between the way physicians responded to patient expressions of negative emotion and patient anxiety, ratings of communication in the encounter, and encounter length. We collected data between August 2008 and March 2009 on the general medical service at 2 urban hospitals that are part of an academic medical center. Participants were attending hospitalists (not physician trainees), and patients admitted under participating hospitalists’ care who were able to communicate verbally in English and provide informed consent for the study. The institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco approved the study; physician and patient participants provided written informed consent.

Enrollment and data collection has been described previously.17 Our cohort for this analysis included 76 patients of 27 physicians who completed encounter audio recordings and pre- and postencounter surveys. Following enrollment, patients completed a preencounter survey to collect demographic information and to measure their baseline anxiety via the State Anxiety Scale (STAI-S), which assesses transient anxious mood using 20 items answered on a 4-point scale for a final score range of 20 to 80.10,18,19 We timed and audio-recorded admission encounters. Encounter recordings were obtained solely from patient interactions with attending hospitalists and did not take into account the time patients may have spent with other physicians, including trainees. After the encounter, patients completed postencounter surveys, which included the STAI-S and patients’ ratings of communication during the encounter. To rate communication, patients responded to 7 items on a 0- to 10-point scale that were derived from previous work (Table 1)12,20,21; the anchors were “not at all” and “completely.” To identify patients with serious illness, which we used as a covariate in regression models, we asked physicians on a postencounter survey whether or not they “would be surprised by this patient’s death or admission to the ICU in the next year.”22

We considered physician as a clustering variable in the calculation of robust standard errors for all models. In addition, we included in each model covariates that were associated with the outcome at P ≤ 0.10, including patient gender, patient age, serious illness,22 preencounter anxiety, encounter length, and hospital. We considered P values < 0.05 to be statistically significant. We used Stata SE 13 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

We analyzed data from admission encounters with 76 patients (consent rate 63%) and 27 hospitalists (consent rate 91%). Their characteristics are shown in Table 3. Median encounter length was 19 minutes (mean 21 minutes, range 3-68). Patients expressed negative emotion in 190 instances across all encounters; median number of expressions per encounter was 1 (range 0-14). Hospitalists responded empathically to 32% (n = 61) of the patient expressions, neutrally to 43% (n = 81), and nonempathically to 25% (n = 48).

The STAI-S was normally distributed. The mean preencounter STAI-S score was 39 (standard deviation [SD] 8.9). Mean postencounter STAI-S score was 38 (SD 10.7). Mean change in anxiety over the course of the encounter, calculated as the postencounter minus preencounter mean was −1.2 (SD 7.6). Table 1 shows summary statistics for the patient ratings of communication items. All items were rated highly. Across the items, between 51% and 78% of patients rated the highest score of 10.

Across the range of frequencies of emotional expressions per encounter in our data set (0-14 expressions), each additional empathic hospitalist response was associated with a 1.65-point decrease in the STAI-S (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-2.82). We did not find significant associations between changes in the STAI-S and the number of neutral hospitalist responses (−0.65 per response; 95% CI, −1.67-0.37) or nonempathic hospitalist responses (0.61 per response; 95% CI, −0.88-2.10).

In addition, nonempathic responses were associated with more negative ratings of communication for 5 of the 7 items: ease of understanding information, covering points of interest, the doctor listening, the doctor caring, and trusting the doctor. For example, for the item “I felt this doctor cared about me,” each nonempathic hospitalist response was associated with a more than doubling of negative patient ratings (aRE: 2.3; 95% CI, 1.32-4.16). Neutral physician responses to patient expressions of negative emotion were associated with less negative patient ratings for 2 of the items: covering points of interest (aRE 0.68; 95% CI, 0.51-0.90) and trusting the doctor (aRE: 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.99).

We did not find a statistical association between encounter length and the number of empathic hospitalist responses in the encounter (percent change in encounter length per response [PC]: 1%; 95% CI, −8%-10%) or the number of nonempathic responses (PC: 18%; 95% CI, −2%-42%). We did find a statistically significant association between the number of neutral responses and encounter length (PC: 13%; 95% CI, 3%-24%), corresponding to 2.5 minutes of additional encounter time per neutral response for the median encounter length of 19 minutes.

DISCUSSION

Our study set out to measure how hospitalists responded to expressions of negative emotion during admission encounters with patients and how those responses correlated with patient anxiety, ratings of communication, and encounter length. We found that empathic responses were associated with diminishing patient anxiety after the visit, as well as with better ratings of several domains of hospitalist communication. Moreover, nonempathic responses to negative emotion were associated with more strongly negative ratings of hospitalist communication. Finally, while clinicians may worry that encouraging patients to speak further about emotion will result in excessive visit lengths, we did not find a statistical association between empathic responses and encounter duration. To our knowledge, this is the first study to indicate an association between empathy and patient anxiety and communication ratings within the hospitalist model, which is rapidly becoming the predominant model for providing inpatient care in the United States.4,5

As in oncologic care, anxiety is an emotion commonly confronted by clinicians meeting admitted medical patients for the first time. Studies show that not only do patient anxiety levels remain high throughout a hospital course, patients who experience higher levels of anxiety tend to stay longer in the hospital.1,2,27-30 But unlike oncologic care or other therapy provided in an outpatient setting, the hospitalist model does not facilitate “continuity” of care, or the ability to care for the same patients over a long period of time. This reality of inpatient care makes rapid, effective rapport-building critical to establishing strong physician-patient relationships. In this setting, a simple communication tool that is potentially able to reduce inpatients’ anxiety could have a meaningful impact on hospitalist-provided care and patient outcomes.

In terms of the magnitude of the effect of empathic responses, the clinical significance of a 1.65-point decrease in the STAI-S anxiety score is not precisely clear. A prior study that examined the effect of music therapy on anxiety levels in patients with cancer found an average anxiety reduction of approximately 9.5 units on the STAIS-S scale after sensitivity analysis, suggesting a rather large meaningful effect size.31 Given we found a reduction of 1.65 points for each empathic response, however, with a range of 0-14 negative emotions expressed over a median 19-minute encounter, there is opportunity for hospitalists to achieve a clinically significant decrease in patient anxiety during an admission encounter. The potential to reduce anxiety is extended further when we consider that the impact of an empathic response may apply not just to the admission encounter alone but also to numerous other patient-clinician interactions over the course of a hospitalization.

A healthy body of communication research supports the associations we found in our study between empathy and patient ratings of communication and physicians. Families in ICU conferences rate communication more positively when physicians express empathy,12 and a number of studies indicate an association between empathy and patient satisfaction in outpatient settings.8 Given the associations we found with negative ratings on the items in our study, promoting empathic responses to expressions of emotion and, more importantly, stressing avoidance of nonempathic responses may be relevant efforts in working to improve patient satisfaction scores on surveys reporting “top box” percentages, such as Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). More notably, evidence indicates that empathy has positive impacts beyond satisfaction surveys, such as adherence, better diagnostic and clinical outcomes, and strengthening of patient enablement.8Not all hospitalist responses to emotion were associated with patient ratings across the 7 communication items we assessed. For example, we did not find an association between how physicians responded to patient expressions of negative emotion and patient perception that enough time was spent in the visit or the degree to which talking with the doctor met a patient’s overall needs. It follows logically, and other research supports, that empathy would influence patient ratings of physician caring and trust,32 whereas other communication factors we were unable to measure (eg, physician body language, tone, and use of jargon and patient health literacy and primary language) may have a more significant association with patient ratings of the other items we assessed.

In considering the clinical application of our results, it is important to note that communication skills, including responding empathically to patient expressions of negative emotion, can be imparted through training in the same way as abdominal examination or electrocardiogram interpretation skills.33-35 However, training of hospitalists in communication skills requires time and some financial investment on the part of the physician, their hospital or group, or, ideally, both. Effective training methods, like those for other skill acquisition, involve learner-centered teaching and practicing skills with role-play and feedback.36 Given the importance of a learner-centered approach, learning would likely be better received and more effective if it was tailored to the specific needs and patient scenarios commonly encountered by hospitalist physicians. As these programs are developed, it will be important to assess the impact of any training on the patient-reported outcomes we assessed in this observational study, along with clinical outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. First, we were only able to evaluate whether hospitalists verbally responded to patient emotion and were thus not able to account for nonverbal empathy such as facial expressions, body language, or voice tone. Second, given our patient consent rate of 63%, patients who agreed to participate in the study may have had different opinions than those who declined to participate. Also, hospitalists and patients may have behaved differently as a result of being audio recorded. We only included patients who spoke English, and our patient population was predominately non-Hispanic white. Patients who spoke other languages or came from other cultural backgrounds may have had different responses. Third, we did not use a single validated scale for patient ratings of communication, and multiple analyses increase our risk of finding statistically significant associations by chance. The skewing of the communication rating items toward high scores may also have led to our results being driven by outliers, although the model we chose for analysis does penalize for this. Furthermore, our sample size was small, leading to wide CIs and potential for lack of statistical associations due to insufficient power. Our findings warrant replication in larger studies. Fourth, the setting of our study in an academic center may affect generalizability. Finally, the age of our data (collected between 2008 and 2009) is also a limitation. Given a recent focus on communication and patient experience since the initiation of HCAHPS feedback, a similar analysis of empathy and communication methods now may result in different outcomes.

In conclusion, our results suggest that enhancing hospitalists’ empathic responses to patient expressions of negative emotion could decrease patient anxiety and improve patients’ perceptions of (and thus possibly their relationships with) hospitalists, without sacrificing efficiency. Future work should focus on tailoring and implementing communication skills training programs for hospitalists and evaluating the impact of training on patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere thanks to the patients and physicians who participated in this study. Dr. Anderson was funded by the National Palliative Care Research Center and the University of California, San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute Career Development Program, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant number 5 KL2 RR024130-04. Project costs were funded by a grant from the University of California, San Francisco Academic Senate.

Disclosure

All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of this manuscript. This submission is not under review by any other publication. Wendy Anderson received funding for this project from the National Palliative Care Research Center, University of California San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NIH grant number 5KL2RR024130-04), and the University of San Francisco Academic Senate [From Section 2 of Author Disclosure Form]. Andy Auerbach has a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute research grant in development [From Section 3 of the Author Disclosure Form].

Admission to a hospital can be a stressful event,1,2 and patients report having many concerns at the time of hospital admission.3 Over the last 20 years, the United States has widely adopted the hospitalist model of inpatient care. Although this model has clear benefits, it also has the potential to contribute to patient stress, as hospitalized patients generally lack preexisting relationships with their inpatient physicians.4,5 In this changing hospital environment, defining and promoting effective medical communication has become an essential goal of both individual practitioners and medical centers.

Successful communication and strong therapeutic relationships with physicians support patients’ coping with illness-associated stress6,7 as well as promote adherence to medical treatment plans.8 Empathy serves as an important building block of patient-centered communication and encourages a strong therapeutic alliance.9 Studies from primary care, oncology, and intensive care unit (ICU) settings indicate that physician empathy is associated with decreased emotional distress,10,11 improved ratings of communication,12 and even better medical outcomes.13

Prior work has shown that hospitalists, like other clinicians, underutilize empathy as a tool in their daily interactions with patients.14-16 Our prior qualitative analysis of audio-recorded hospitalist-patient admission encounters indicated that how hospitalists respond to patient expressions of negative emotion influences relationships with patients and alignment around care plans.17 To determine whether empathic communication is associated with patient-reported outcomes in the hospitalist model, we quantitatively analyzed coded admission encounters and survey data to examine the association between hospitalists’ responses to patient expressions of negative emotion (anxiety, sadness, and anger) and patient anxiety and ratings of communication. Given the often-limited time hospitalists have to complete admission encounters, we also examined the association between response to emotion and encounter length.

METHODS

We analyzed data collected as part of an observational study of hospitalist-patient communication during hospital admission encounters14 to assess the association between the way physicians responded to patient expressions of negative emotion and patient anxiety, ratings of communication in the encounter, and encounter length. We collected data between August 2008 and March 2009 on the general medical service at 2 urban hospitals that are part of an academic medical center. Participants were attending hospitalists (not physician trainees), and patients admitted under participating hospitalists’ care who were able to communicate verbally in English and provide informed consent for the study. The institutional review board at the University of California, San Francisco approved the study; physician and patient participants provided written informed consent.

Enrollment and data collection has been described previously.17 Our cohort for this analysis included 76 patients of 27 physicians who completed encounter audio recordings and pre- and postencounter surveys. Following enrollment, patients completed a preencounter survey to collect demographic information and to measure their baseline anxiety via the State Anxiety Scale (STAI-S), which assesses transient anxious mood using 20 items answered on a 4-point scale for a final score range of 20 to 80.10,18,19 We timed and audio-recorded admission encounters. Encounter recordings were obtained solely from patient interactions with attending hospitalists and did not take into account the time patients may have spent with other physicians, including trainees. After the encounter, patients completed postencounter surveys, which included the STAI-S and patients’ ratings of communication during the encounter. To rate communication, patients responded to 7 items on a 0- to 10-point scale that were derived from previous work (Table 1)12,20,21; the anchors were “not at all” and “completely.” To identify patients with serious illness, which we used as a covariate in regression models, we asked physicians on a postencounter survey whether or not they “would be surprised by this patient’s death or admission to the ICU in the next year.”22

We considered physician as a clustering variable in the calculation of robust standard errors for all models. In addition, we included in each model covariates that were associated with the outcome at P ≤ 0.10, including patient gender, patient age, serious illness,22 preencounter anxiety, encounter length, and hospital. We considered P values < 0.05 to be statistically significant. We used Stata SE 13 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) for all statistical analyses.

RESULTS

We analyzed data from admission encounters with 76 patients (consent rate 63%) and 27 hospitalists (consent rate 91%). Their characteristics are shown in Table 3. Median encounter length was 19 minutes (mean 21 minutes, range 3-68). Patients expressed negative emotion in 190 instances across all encounters; median number of expressions per encounter was 1 (range 0-14). Hospitalists responded empathically to 32% (n = 61) of the patient expressions, neutrally to 43% (n = 81), and nonempathically to 25% (n = 48).

The STAI-S was normally distributed. The mean preencounter STAI-S score was 39 (standard deviation [SD] 8.9). Mean postencounter STAI-S score was 38 (SD 10.7). Mean change in anxiety over the course of the encounter, calculated as the postencounter minus preencounter mean was −1.2 (SD 7.6). Table 1 shows summary statistics for the patient ratings of communication items. All items were rated highly. Across the items, between 51% and 78% of patients rated the highest score of 10.

Across the range of frequencies of emotional expressions per encounter in our data set (0-14 expressions), each additional empathic hospitalist response was associated with a 1.65-point decrease in the STAI-S (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.48-2.82). We did not find significant associations between changes in the STAI-S and the number of neutral hospitalist responses (−0.65 per response; 95% CI, −1.67-0.37) or nonempathic hospitalist responses (0.61 per response; 95% CI, −0.88-2.10).

In addition, nonempathic responses were associated with more negative ratings of communication for 5 of the 7 items: ease of understanding information, covering points of interest, the doctor listening, the doctor caring, and trusting the doctor. For example, for the item “I felt this doctor cared about me,” each nonempathic hospitalist response was associated with a more than doubling of negative patient ratings (aRE: 2.3; 95% CI, 1.32-4.16). Neutral physician responses to patient expressions of negative emotion were associated with less negative patient ratings for 2 of the items: covering points of interest (aRE 0.68; 95% CI, 0.51-0.90) and trusting the doctor (aRE: 0.86; 95% CI, 0.75-0.99).

We did not find a statistical association between encounter length and the number of empathic hospitalist responses in the encounter (percent change in encounter length per response [PC]: 1%; 95% CI, −8%-10%) or the number of nonempathic responses (PC: 18%; 95% CI, −2%-42%). We did find a statistically significant association between the number of neutral responses and encounter length (PC: 13%; 95% CI, 3%-24%), corresponding to 2.5 minutes of additional encounter time per neutral response for the median encounter length of 19 minutes.

DISCUSSION

Our study set out to measure how hospitalists responded to expressions of negative emotion during admission encounters with patients and how those responses correlated with patient anxiety, ratings of communication, and encounter length. We found that empathic responses were associated with diminishing patient anxiety after the visit, as well as with better ratings of several domains of hospitalist communication. Moreover, nonempathic responses to negative emotion were associated with more strongly negative ratings of hospitalist communication. Finally, while clinicians may worry that encouraging patients to speak further about emotion will result in excessive visit lengths, we did not find a statistical association between empathic responses and encounter duration. To our knowledge, this is the first study to indicate an association between empathy and patient anxiety and communication ratings within the hospitalist model, which is rapidly becoming the predominant model for providing inpatient care in the United States.4,5

As in oncologic care, anxiety is an emotion commonly confronted by clinicians meeting admitted medical patients for the first time. Studies show that not only do patient anxiety levels remain high throughout a hospital course, patients who experience higher levels of anxiety tend to stay longer in the hospital.1,2,27-30 But unlike oncologic care or other therapy provided in an outpatient setting, the hospitalist model does not facilitate “continuity” of care, or the ability to care for the same patients over a long period of time. This reality of inpatient care makes rapid, effective rapport-building critical to establishing strong physician-patient relationships. In this setting, a simple communication tool that is potentially able to reduce inpatients’ anxiety could have a meaningful impact on hospitalist-provided care and patient outcomes.

In terms of the magnitude of the effect of empathic responses, the clinical significance of a 1.65-point decrease in the STAI-S anxiety score is not precisely clear. A prior study that examined the effect of music therapy on anxiety levels in patients with cancer found an average anxiety reduction of approximately 9.5 units on the STAIS-S scale after sensitivity analysis, suggesting a rather large meaningful effect size.31 Given we found a reduction of 1.65 points for each empathic response, however, with a range of 0-14 negative emotions expressed over a median 19-minute encounter, there is opportunity for hospitalists to achieve a clinically significant decrease in patient anxiety during an admission encounter. The potential to reduce anxiety is extended further when we consider that the impact of an empathic response may apply not just to the admission encounter alone but also to numerous other patient-clinician interactions over the course of a hospitalization.

A healthy body of communication research supports the associations we found in our study between empathy and patient ratings of communication and physicians. Families in ICU conferences rate communication more positively when physicians express empathy,12 and a number of studies indicate an association between empathy and patient satisfaction in outpatient settings.8 Given the associations we found with negative ratings on the items in our study, promoting empathic responses to expressions of emotion and, more importantly, stressing avoidance of nonempathic responses may be relevant efforts in working to improve patient satisfaction scores on surveys reporting “top box” percentages, such as Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS). More notably, evidence indicates that empathy has positive impacts beyond satisfaction surveys, such as adherence, better diagnostic and clinical outcomes, and strengthening of patient enablement.8Not all hospitalist responses to emotion were associated with patient ratings across the 7 communication items we assessed. For example, we did not find an association between how physicians responded to patient expressions of negative emotion and patient perception that enough time was spent in the visit or the degree to which talking with the doctor met a patient’s overall needs. It follows logically, and other research supports, that empathy would influence patient ratings of physician caring and trust,32 whereas other communication factors we were unable to measure (eg, physician body language, tone, and use of jargon and patient health literacy and primary language) may have a more significant association with patient ratings of the other items we assessed.

In considering the clinical application of our results, it is important to note that communication skills, including responding empathically to patient expressions of negative emotion, can be imparted through training in the same way as abdominal examination or electrocardiogram interpretation skills.33-35 However, training of hospitalists in communication skills requires time and some financial investment on the part of the physician, their hospital or group, or, ideally, both. Effective training methods, like those for other skill acquisition, involve learner-centered teaching and practicing skills with role-play and feedback.36 Given the importance of a learner-centered approach, learning would likely be better received and more effective if it was tailored to the specific needs and patient scenarios commonly encountered by hospitalist physicians. As these programs are developed, it will be important to assess the impact of any training on the patient-reported outcomes we assessed in this observational study, along with clinical outcomes.

Our study has several limitations. First, we were only able to evaluate whether hospitalists verbally responded to patient emotion and were thus not able to account for nonverbal empathy such as facial expressions, body language, or voice tone. Second, given our patient consent rate of 63%, patients who agreed to participate in the study may have had different opinions than those who declined to participate. Also, hospitalists and patients may have behaved differently as a result of being audio recorded. We only included patients who spoke English, and our patient population was predominately non-Hispanic white. Patients who spoke other languages or came from other cultural backgrounds may have had different responses. Third, we did not use a single validated scale for patient ratings of communication, and multiple analyses increase our risk of finding statistically significant associations by chance. The skewing of the communication rating items toward high scores may also have led to our results being driven by outliers, although the model we chose for analysis does penalize for this. Furthermore, our sample size was small, leading to wide CIs and potential for lack of statistical associations due to insufficient power. Our findings warrant replication in larger studies. Fourth, the setting of our study in an academic center may affect generalizability. Finally, the age of our data (collected between 2008 and 2009) is also a limitation. Given a recent focus on communication and patient experience since the initiation of HCAHPS feedback, a similar analysis of empathy and communication methods now may result in different outcomes.

In conclusion, our results suggest that enhancing hospitalists’ empathic responses to patient expressions of negative emotion could decrease patient anxiety and improve patients’ perceptions of (and thus possibly their relationships with) hospitalists, without sacrificing efficiency. Future work should focus on tailoring and implementing communication skills training programs for hospitalists and evaluating the impact of training on patient outcomes.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their sincere thanks to the patients and physicians who participated in this study. Dr. Anderson was funded by the National Palliative Care Research Center and the University of California, San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute Career Development Program, National Institutes of Health (NIH) grant number 5 KL2 RR024130-04. Project costs were funded by a grant from the University of California, San Francisco Academic Senate.

Disclosure

All coauthors have seen and agree with the contents of this manuscript. This submission is not under review by any other publication. Wendy Anderson received funding for this project from the National Palliative Care Research Center, University of California San Francisco Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NIH grant number 5KL2RR024130-04), and the University of San Francisco Academic Senate [From Section 2 of Author Disclosure Form]. Andy Auerbach has a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute research grant in development [From Section 3 of the Author Disclosure Form].

1. Walker FB, Novack DH, Kaiser DL, Knight A, Oblinger P. Anxiety and depression among medical and surgical patients nearing hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 1987;2(2):99-101. PubMed

2. Castillo MI, Cooke M, Macfarlane B, Aitken LM. Factors associated with anxiety in critically ill patients: A prospective observational cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;60:225-233. PubMed

3. Anderson WG, Winters K, Auerbach AD. Patient concerns at hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1399-1400. PubMed

4. Kuo Y-F, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102-1112. PubMed

5. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. PubMed

6. Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, et al. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: the Human Connection Scale. Cancer. 2009;115(14):3302-3311. PubMed

7. Huff NG, Nadig N, Ford DW, Cox CE. Therapeutic Alliance between the Caregivers of Critical Illness Survivors and Intensive Care Unit Clinicians. [published correction appears in Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(4):576]. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1646-1653. PubMed

8. Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):e76-e84. PubMed

9. Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267. PubMed

10. Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):371-379. PubMed

11. Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(17):1877-1884. PubMed

12. Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Goss CH, Curtis JR. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1679-1685. PubMed

13. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):359-364. PubMed

14. Anderson WG, Winters K, Arnold RM, Puntillo KA, White DB, Auerbach AD. Studying physician-patient communication in the acute care setting: the hospitalist rapport study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):275-279. PubMed

15. Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5748-5752. PubMed

16. Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277(8):678-682. PubMed

17. Adams K, Cimino JEW, Arnold RM, Anderson WG. Why should I talk about emotion? Communication patterns associated with physician discussion of patient expressions of negative emotion in hospital admission encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(1):44-50. PubMed

18. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63 Suppl 11:S467-S472. PubMed

19. Speilberger C, Ritterband L, Sydeman S, Reheiser E, Unger K. Assessment of emotional states and personality traits: measuring psychological vital signs. In: Butcher J, editor. Clinical personality assessment: practical approaches. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995.

20. Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36(5):728-739. PubMed

21. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987-994. PubMed

22. Lynn J. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Serving patients who may die soon and their families: the role of hospice and other services. JAMA. 2001;285(7):925-932. PubMed

23. Kennifer SL, Alexander SC, Pollak KI, et al. Negative emotions in cancer care: do oncologists’ responses depend on severity and type of emotion? Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(1):51-56. PubMed

24. Butow PN, Brown RF, Cogar S, Tattersall MHN, Dunn SM. Oncologists’ reactions to cancer patients’ verbal cues. Psychooncology. 2002;11(1):47-58. PubMed

25. Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA. 2000;284(8):1021-1027. PubMed

26. Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37-46.

27. Fulop G. Anxiety disorders in the general hospital setting. Psychiatr Med. 1990;8(3):187-195. PubMed

28. Gerson S, Mistry R, Bastani R, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety (MHI) following acute medical/surgical hospitalization and post-discharge psychiatric diagnoses (DSM) in 839 geriatric US veterans. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(12):1155-1167. PubMed

29. Kathol RG, Wenzel RP. Natural history of symptoms of depression and anxiety during inpatient treatment on general medicine wards. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(3):287-293. PubMed

30. Unsal A, Unaldi C, Baytemir C. Anxiety and depression levels of inpatients in the city centre of Kirşehir in Turkey. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(4):411-418. PubMed

31. Bradt J, Dileo C, Grocke D, Magill L. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. [Update appears in Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(8):CD006911] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD006911. PubMed

32. Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):237-251. PubMed

33. Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(9):593-601. PubMed

34. Bays AM, Engelberg RA, Back AL, et al. Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: evaluation of a small-group, simulated patient intervention. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(2):159-166. PubMed

35. Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al. Effect of a Patient-Centered Communication Intervention on Oncologist-Patient Communication, Quality of Life, and Health Care Utilization in Advanced Cancer: The VOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):92-100. PubMed

36. Berkhof M, van Rijssen HJ, Schellart AJM, Anema JR, van der Beek AJ. Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(2):152-162. PubMed

1. Walker FB, Novack DH, Kaiser DL, Knight A, Oblinger P. Anxiety and depression among medical and surgical patients nearing hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 1987;2(2):99-101. PubMed

2. Castillo MI, Cooke M, Macfarlane B, Aitken LM. Factors associated with anxiety in critically ill patients: A prospective observational cohort study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2016;60:225-233. PubMed

3. Anderson WG, Winters K, Auerbach AD. Patient concerns at hospital admission. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(15):1399-1400. PubMed

4. Kuo Y-F, Sharma G, Freeman JL, Goodwin JS. Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102-1112. PubMed

5. Wachter RM, Goldman L. Zero to 50,000 - The 20th Anniversary of the Hospitalist. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(11):1009-1011. PubMed

6. Mack JW, Block SD, Nilsson M, et al. Measuring therapeutic alliance between oncologists and patients with advanced cancer: the Human Connection Scale. Cancer. 2009;115(14):3302-3311. PubMed

7. Huff NG, Nadig N, Ford DW, Cox CE. Therapeutic Alliance between the Caregivers of Critical Illness Survivors and Intensive Care Unit Clinicians. [published correction appears in Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(4):576]. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(11):1646-1653. PubMed

8. Derksen F, Bensing J, Lagro-Janssen A. Effectiveness of empathy in general practice: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63(606):e76-e84. PubMed

9. Dwamena F, Holmes-Rovner M, Gaulden CM, et al. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;12:CD003267. PubMed

10. Fogarty LA, Curbow BA, Wingard JR, McDonnell K, Somerfield MR. Can 40 seconds of compassion reduce patient anxiety? J Clin Oncol. 1999;17(1):371-379. PubMed

11. Roter DL, Hall JA, Kern DE, Barker LR, Cole KA, Roca RP. Improving physicians’ interviewing skills and reducing patients’ emotional distress. A randomized clinical trial. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155(17):1877-1884. PubMed

12. Stapleton RD, Engelberg RA, Wenrich MD, Goss CH, Curtis JR. Clinician statements and family satisfaction with family conferences in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(6):1679-1685. PubMed

13. Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):359-364. PubMed

14. Anderson WG, Winters K, Arnold RM, Puntillo KA, White DB, Auerbach AD. Studying physician-patient communication in the acute care setting: the hospitalist rapport study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(2):275-279. PubMed

15. Pollak KI, Arnold RM, Jeffreys AS, et al. Oncologist communication about emotion during visits with patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(36):5748-5752. PubMed

16. Suchman AL, Markakis K, Beckman HB, Frankel R. A model of empathic communication in the medical interview. JAMA. 1997;277(8):678-682. PubMed

17. Adams K, Cimino JEW, Arnold RM, Anderson WG. Why should I talk about emotion? Communication patterns associated with physician discussion of patient expressions of negative emotion in hospital admission encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89(1):44-50. PubMed

18. Julian LJ. Measures of anxiety: State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI), and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale-Anxiety (HADS-A). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63 Suppl 11:S467-S472. PubMed

19. Speilberger C, Ritterband L, Sydeman S, Reheiser E, Unger K. Assessment of emotional states and personality traits: measuring psychological vital signs. In: Butcher J, editor. Clinical personality assessment: practical approaches. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995.

20. Safran DG, Kosinski M, Tarlov AR, et al. The Primary Care Assessment Survey: tests of data quality and measurement performance. Med Care. 1998;36(5):728-739. PubMed

21. Azoulay E, Pochard F, Kentish-Barnes N, et al. Risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms in family members of intensive care unit patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171(9):987-994. PubMed

22. Lynn J. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Serving patients who may die soon and their families: the role of hospice and other services. JAMA. 2001;285(7):925-932. PubMed

23. Kennifer SL, Alexander SC, Pollak KI, et al. Negative emotions in cancer care: do oncologists’ responses depend on severity and type of emotion? Patient Educ Couns. 2009;76(1):51-56. PubMed

24. Butow PN, Brown RF, Cogar S, Tattersall MHN, Dunn SM. Oncologists’ reactions to cancer patients’ verbal cues. Psychooncology. 2002;11(1):47-58. PubMed

25. Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA. 2000;284(8):1021-1027. PubMed

26. Cohen J. A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educ Psychol Meas. 1960;20(1):37-46.

27. Fulop G. Anxiety disorders in the general hospital setting. Psychiatr Med. 1990;8(3):187-195. PubMed

28. Gerson S, Mistry R, Bastani R, et al. Symptoms of depression and anxiety (MHI) following acute medical/surgical hospitalization and post-discharge psychiatric diagnoses (DSM) in 839 geriatric US veterans. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;19(12):1155-1167. PubMed

29. Kathol RG, Wenzel RP. Natural history of symptoms of depression and anxiety during inpatient treatment on general medicine wards. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7(3):287-293. PubMed

30. Unsal A, Unaldi C, Baytemir C. Anxiety and depression levels of inpatients in the city centre of Kirşehir in Turkey. Int J Nurs Pract. 2011;17(4):411-418. PubMed

31. Bradt J, Dileo C, Grocke D, Magill L. Music interventions for improving psychological and physical outcomes in cancer patients. [Update appears in Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(8):CD006911] Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(8):CD006911. PubMed

32. Kim SS, Kaplowitz S, Johnston MV. The effects of physician empathy on patient satisfaction and compliance. Eval Health Prof. 2004;27(3):237-251. PubMed

33. Tulsky JA, Arnold RM, Alexander SC, et al. Enhancing communication between oncologists and patients with a computer-based training program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(9):593-601. PubMed

34. Bays AM, Engelberg RA, Back AL, et al. Interprofessional communication skills training for serious illness: evaluation of a small-group, simulated patient intervention. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(2):159-166. PubMed

35. Epstein RM, Duberstein PR, Fenton JJ, et al. Effect of a Patient-Centered Communication Intervention on Oncologist-Patient Communication, Quality of Life, and Health Care Utilization in Advanced Cancer: The VOICE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(1):92-100. PubMed

36. Berkhof M, van Rijssen HJ, Schellart AJM, Anema JR, van der Beek AJ. Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;84(2):152-162. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

A Talking Map for Family Meetings in the Intensive Care Unit

From the Department of Neurology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC (Dr. McFarlin), the Department of Psychosocial Oncology and Palliative Care, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA (Dr. Tulsky), Harborview Medical Center, University of Washington, Seattle, WA (Dr. Back), and Department of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA (Dr. Arnold).

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the use of a cognitive map for navigating family meetings with surrogate decision makers of patients in an intensive care unit.

- Methods: Descriptive report and discussion using an illustrative case to outline the steps in the cognitive map.

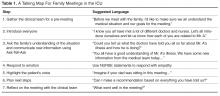

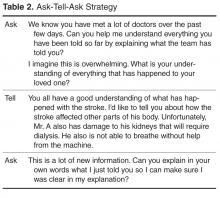

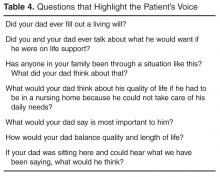

- Results: The use of cognitive maps has improved the ability of physicians to efficiently perform a specific communication skill. During a “goals of care” conversation, the cognitive map follows these steps: (1) Gather the clinical team for a pre-meeting, (2) Introduce everyone, (3) Use the “ask-tell-ask” strategy to communicate information, (4) Respond to emotion, (5) Highlight the patient’s voice, (6) Plan next steps, (7) Reflect on the meeting with the team. Providing this map of key communication skills will help faculty teach learners the core components of a family meeting.

- Conclusion: Practicing the behaviors demonstrated in the cognitive map may increase clinician skill during difficult conversations. Improving communication with surrogate decision makers will increase the support we offer to critically ill patients and their loved ones.

Key words: intensive care unit; communication; family meeting; critical illness; decision making; end of life care.

Family members of patients in the ICU value high-quality communication with the medical team. In fact, family members report that physicians’ communication skills are often more important than their medical skills [1]. Multiple professional societies, including the American Thoracic Society and the Society of Critical Care Medicine, define communication with families as a key component of high-quality critical care. Effective physician-patient communication improves measureable outcomes including decreased ICU length of stay [2] and may reduce distress amongst patients’ families [3]. The American College of Chest Physicians position statement on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Patients with Cardiopulmonary Diseases urges physicians to develop curricula that incorporate interpersonal communication skills into training [4].

Unfortunately, such high-quality communication is not the norm. Surrogate decision makers are often displeased with the frequency of communication, the limited availability of attending physicians, and report feeling excluded from discussions [5]. When family meetings do occur, surrogate decision makers report inadequate understanding of diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment plans [6].

Physicians also find family meetings difficult. Intensivists worry that high-quality family meetings are time consuming and difficult to do in a busy ICU [7]. Critical care fellows report not feeling adequately trained to conduct family meetings [8]. It makes sense that untrained clinicians would want to avoid a conversation that is emotionally charged, particularly if one is unsure how to respond effectively.

The Case of Mr. A

Thomas A. is a 79-year-old man admitted to the medical intensive care unit 7 days earlier with a large left middle cerebral artery territory infarction. Given his decreased mental status, on admission he was intubated for airway protection. He is awake but aphasic and unable to follow any commands or move his right side. The neurology consultants do not feel this will improve. He has significant secretions and episodes of hypoxia. He has also developed acute on chronic kidney injury and may need to start dialysis. The social worker explains that his need for dialysis limits his placement options and that he will not be able to be discharged to home. Given his lack of improvement the team is concerned he will need a tracheostomy and feeding tube placed in order to safely continue this level of care. A family meeting is arranged to understand Mr. A’s goals of care.

Talking Map Basics

Before each step is discussed in detail, some definitions are needed. “Family” can be defined as anyone important enough, biologically related or not, to be present at a conversation with a clinician [10]. Second, a “family meeting” is a planned event between the family and interdisciplinary members of the ICU team as well as any other health care providers who have been involved in the patient’s care. The meeting takes place in a private space and at a time that is scheduled with the families’ needs in mind. Thus it is different from having families present on rounds or one-off meetings with particular clinicians.

Goals of care meetings are typically held when, in the clinicians’ view, the current treatments are not achieving the previously stated goals. Thus, the meeting has 2 purposes: first, to give the family the bad news that the current plan is not working and second, to develop a new plan based on the patient’s values. The family’s job, as surrogate decision maker, is to provide information about what would be most important to the patient. The clinician’s job is to suggest treatment plans that have the best probability of matching the patient’s values.

Not all of these tasks need be done at once. Some families will not be able to move from hearing bad news to making a decision without having time to first reflect and grieve. Others will need to confer with other family members privately before deciding on a plan. In many cases, a time-limited trial may be the right option with a plan for subsequent meetings. Given this, we recommend checking in with the family between each step to ensure that they feel safe moving ahead. For example, one might ask “Is it OK if we talk about what happens next?”

Talking Map Steps in Detail

1. Gather the Clinical Team for a Pre-Meeting

ICU care involves a large interdisciplinary care team. A “meeting before the meeting” with the entire clinical team is an opportunity to reach consensus on prognosis and therapeutic options, share prior interactions with family, and determine goals for the family meeting. It is also helpful to clarify team members’ roles at the meeting and to choose a primary facilitator. All of this helps to ensure that the family receives a consistent message during the meeting. The pre-meeting is also an opportunity to ask a team member to observe the communication skills of the facilitator and be prepared to give feedback after the meeting.

At this time, the team should also create the proper environment for the family meeting. This includes a quiet room free of interruptions with ample seating, available tissues, and transferred pagers and cell phones.

The intensivist and bedside nurse should always be present at the family meeting, and it is best when the same attending can be at subsequent family meetings Their consistent dual presence provides the uniform communication from the team, can reduce anxiety in family members and the collaboration reduces ICU nurse and physician burnout [11]. For illnesses that involve a specific disease or organ system, it is important to have the specialist at the meeting who can provide the appropriate expertise.

The Pre-Meeting