User login

Assessment of Personal Medical History Knowledge in Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease: A Pilot Study

From the Departments of Psychology (Ms. Zhao, Drs. Russell, Wesley, and Porter) and Hematology (Mss. Johnson and Pullen, Dr. Hankins), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

Abstract

- Background: Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) are surviving into adulthood. Mastery of disease knowledge may facilitate treatment continuity in adult care.

- Objective: To assess the accuracy and extent of medical history knowledge among adolescents with SCD through the use of a personal health record (PHR) form.

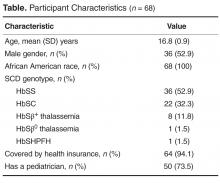

- Methods: 68 adolescent patients with SCD (52.9% male; mean age, 16.8 years; 100% African American) completed a PHR listing significant prior medical events (eg, disease complications, diagnostic evaluations, treatments). Responses were compared against participants’ electronic medical record. An agreement percentage was calculated to determine accuracy of knowledge.

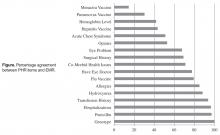

- Results: Most adolescents correctly reported their sickle cell genotype (100%), usage of penicillin (97.1%), prior hospitalizations (96.5%), history of prior blood transfusions (93.8%), usage of hydroxyurea (88.2%), and allergies (85.2%). Fewer adolescents accurately reported usage of opioids (52.9%), prior acute chest syndrome events (50.9%), baseline hemoglobin (41.8%), and hepatitis (43.3%), pneumovax (30.2%), and menactra (14.5%) vaccinations.

- Conclusion: Adolescents are aware of most but not all aspects of their medical history. The present findings can inform areas of knowledge deficits. Future targeted interventions for transition education and preparation may be tailored based on individual disease knowledge.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder characterized by abnormal sickle hemoglobin resulting in chronic hemolytic anemia and vaso-occlusion [1]. More than 95% of children with SCD in the United States survive into adulthood; however, young adults (YAs) are at risk for mortality shortly after transfer to adult health care [2–5]. Specifically, YAs with SCD (ages 18 to 30) have increased hospital utilization, emergency department visits, and mortality compared to other age-groups [4–7]. During this critical period, transition preparation that includes improving disease literacy and ensuring medical history knowledge may be necessary for optimal outcomes.

In the extant YA literature, significant gaps in medical history knowledge during the transition period were observed in pediatric cancer and inflammatory bowel disease patients [8,9]. YAs often require multidisciplinary management of their chronic disease complications [10]. Therefore, possessing comprehensive knowledge of personal health history may facilitate communication with different adult care providers and promote continuity of care. In the SCD transition literature, transition readiness measures have been developed to assess several aspects of knowledge, including medical and disease knowledge; however, these measures are primarily self-reported perceptions of knowledge and do not evaluate the accuracy of knowledge [11,12]. The current pilot study addresses this gap with the aim of assessing medical history knowledge accuracy in adolescents with SCD.

Methods

Participants

From March 2011 to January 2014, adolescents (aged 15–18 years) with SCD (any genotype) were approached during their regular health maintenance visits by hematology social workers. They were invited to complete the Personal Health Record (PHR) as an implementation effort of transition preparation within our pediatric SCD program.

Personal Health Record

The PHR was developed through literature review and discussions with area adult hematologists. The form was modeled after first visit intake forms used in adult hematology clinics. It was reviewed by the hematology medical team and the institution’s patient education committee. Prior to implementation, the form was piloted to obtain patient feedback on format and content. The PHR consists of 33 questions with 168 possible items/data points covering 12 domains: personal information (eg, contact information, SCD genotype), health provider information, personal health history (ie, health diagnoses), blood transfusion history, sickle cell pain events, hospitalization history in the previous year, diagnostic testing history (eg, laboratory tests), current medications, immunizations, advance directives, resource information (eg, disability benefits), and activities of daily living. Some questions required patients to check “Yes” or “No” (eg, “Have you been hospitalized in the past year? Have you received flu vaccine?”) while some required a written response (eg, “What medicines do you currently take?”).

Adolescents were instructed to complete the PHR independently without the help of their caregivers. After completing the form, the social worker reviewed the answers and/or asked participants’ perspectives about communicating health information to providers. A copy of the completed PHR was provided to the adolescent to promote continued education regarding medical history knowledge. The retrospective review of the PHR answers and participants’ characteristics was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of consent from participants.

Statistical Methods

PHR answers were compared with each individual’s electronic medical record (EMR) for accuracy of responses. PHR responses were considered accurate only if they matched the information in the EMR. PHR items absent in the EMR were not coded (inability to verify the accuracy of responses) to capture the most accurate depiction of adolescents’ medical history knowledge. Coding was checked by at least 2 coders for response accuracy. Due to lack of EMR information for certain items, we could not verify the accuracy of many PHR items. Therefore, only items with at least 75% of data verified (across all patients who completed the PHR) were included in subsequent analyses.

Using SPSS (version 18), an agreement percentage was calculated for each patient across verifiable items and used as the primary outcome measure of knowledge accuracy. We used t tests to investigate gender or genotype differences in medical history accuracy. To examine genotype differences, we stratified the sample by SCD genotype: HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia and HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia [13].

Results

Patient Characteristics

Knowledge Accuracy Among Adolescents with SCD

Seventeen items in 6 PHR domains had the highest number of data points (at least 75% verified), and therefore were the only items that could be analyzed. Analyzed items included information about sickle cell genotype, eye doctor care, comorbid health issues (eg, asthma), allergies, hospitalizations, surgeries, transfusions, acute chest syndrome (ACS) episodes, eye problems, baseline hemoglobin level, and vaccination history as well as adolescents’ knowledge of current medications, including hydroxyurea, penicillin, and opioid pain medications.

Gender was not significantly associated with overall accuracy (P = 0.36). A significant difference was found in sickle genotype such that individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 8.23; SD = 1.70) were more accurate reporters of their medical history than those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 7.14; SD = 1.75; t(65) = –2.59, P = 0.01). Specifically, those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype were significantly less accurate reporters of vaccination history (meningococcus t(60) = 3.55, P = 0.001; pneumococcus t(60) = 2.46, P = 0.02; hepatitis t(64) = 2.18, P = 0.03, eye problems t(62) = 3.62; P = 0.001, and surgical history t(62) = 2.14, P = 0.04).

Discussion

In the present study, we utilized the PHR to assess the accuracy of medical history knowledge of adolescents with SCD preparing to transition to adult care. Most adolescents were accurate reporters of important disease-relevant information (eg, genotype, transfusion history, hydroxyurea use), which may be a result of these topics being frequently discussed or recently encountered. For example, 97% of adolescents accurately reported penicillin use which may be related to our program’s emphasis on infection prevention education. However, disease knowledge of immunization history, prior ACS events, and opioid medication use might have been more difficult to recall due to the long interval from their occurrence until the completion of the PHR. Further, frequent changes in opioid medication use may have impacted the accuracy of adolescents’ answers with EMR data.

Individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype were more accurate reporters of their medical history, but the magnitude of difference was not large. These individuals tend to have fewer health issues and therefore less health information to recall, leading to higher accuracy. Furthermore, evidence demonstrates that individuals with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype are at greater risk for cerebrovascular events and subsequent cognitive deficits [14], leading to more memory deficits and difficulty understanding and retaining health information [15]. The results suggest that patient health literacy, or an individual’s capacity to understand basic health information [16], may be a mediating factor in assessing for transition readiness. This is especially important given SCD risk for cognitive deficits [17].

Only 17 PHR items were analyzed due to conservative selection of items. Thus the present findings are not representative of the entire medical history. Additionally, the accuracy of medical history knowledge results may be limited by conservatism with abstracting information from the EMR (PHR information was considered accurate if it matched the information found in their EMR). Finally, we did not systematically assess the feasibility and utility of the PHR; ongoing participant feedback would aid in improving the PHR tool and implementation. It would be important to validate the PHR in a larger sample. However, our study is the first to our knowledge to systematically evaluate medical history knowledge among youth with SCD.

Conclusion and Practice Implications

The present study demonstrates that use of the PHR during regular health maintenance visits can help identify gaps in knowledge among adolescents with SCD who are approaching transfer to adult care. Sufficient knowledge of one’s medical history is an important aspect in transition preparation as it can facilitate the communication of medical information, thereby ensuring continuity of care [18,19]. The PHR could be used to teach medical history knowledge, assess a patient’s level of transition readiness at different time points, and identify areas for further targeted intervention. Knowledge tools, such as the PHR, can be investigated prospectively to assess the association of disease literacy and clinical outcomes, serving as a possible predictive instrument for transition health outcomes.

Corresponding author: Jerlym S. Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Dept. of Psychology, 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail Stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02 (PI: Hankins).

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; analysis and interpretation of data, MSZ, KMR, JSP; drafting of article, MSZ, JSP; critical revision of the article, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; provision of study materials or patients, MJ, AP; statistical expertise, KMR; obtaining of funding, JSH; collection and assembly of data, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMR, KMW.

1. Quinn CT. Sickle cell disease in childhood: from newborn screening through transition to adult medical care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013;60:1363–81.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:S512–21.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. de Montalembert M, Guitton C. Transition from paediatric to adult care for patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2014;164:630–5.

5. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

6. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

7. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood Jr C. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

8. Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 2002:287:1832–9.

9. Hait EJ, Barendse RM, Arnold JH, et al. Transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: a survey of adult gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:61–5.

10. Kennedy A, Sawyer S. Transition from pediatric to adult services: are we getting it right? Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20:403–9.

11. Sobota A, Akinlonu A, Champigny M, et al. Self-reported transition readiness among young adults with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:389–94.

12. Treadwell M, Johnson S, Sisler I, et al. Development of a sickle cell disease readiness for transition assessment. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2016;28:193–201.

13. Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, et al. Pain characteristics and age-related pain trajectories in infants and young children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:291–6.

14. Venkataraman A, Adams RJ. Neurologic complications of sickle cell disease. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;120:1015–25.

15. Porter JS, Matthews CS, Carroll YM, et al. Genetic education and sickle cell disease: feasibility and efficacy of a program tailored to adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:572–7.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. 2015. Accessed 26 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/index.html.

17. Armstrong FD, Thompson Jr RJ, Wang W, et al. Cognitive functioning and brain magnetic resonance imaging in children with sickle cell disease. Neuropsychology Committee of the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatrics 1996;97:864–70.

18. Kanter J, Kruse-Jarres R. Management of sickle cell disease from childhood through adulthood. Blood Rev 2013;27:279–87.

19. Treadwell M, Telfair J, Gibson RW, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: establishing evidence-based practice and directions for research. Am J Hematol 2011;86:116–2.

From the Departments of Psychology (Ms. Zhao, Drs. Russell, Wesley, and Porter) and Hematology (Mss. Johnson and Pullen, Dr. Hankins), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

Abstract

- Background: Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) are surviving into adulthood. Mastery of disease knowledge may facilitate treatment continuity in adult care.

- Objective: To assess the accuracy and extent of medical history knowledge among adolescents with SCD through the use of a personal health record (PHR) form.

- Methods: 68 adolescent patients with SCD (52.9% male; mean age, 16.8 years; 100% African American) completed a PHR listing significant prior medical events (eg, disease complications, diagnostic evaluations, treatments). Responses were compared against participants’ electronic medical record. An agreement percentage was calculated to determine accuracy of knowledge.

- Results: Most adolescents correctly reported their sickle cell genotype (100%), usage of penicillin (97.1%), prior hospitalizations (96.5%), history of prior blood transfusions (93.8%), usage of hydroxyurea (88.2%), and allergies (85.2%). Fewer adolescents accurately reported usage of opioids (52.9%), prior acute chest syndrome events (50.9%), baseline hemoglobin (41.8%), and hepatitis (43.3%), pneumovax (30.2%), and menactra (14.5%) vaccinations.

- Conclusion: Adolescents are aware of most but not all aspects of their medical history. The present findings can inform areas of knowledge deficits. Future targeted interventions for transition education and preparation may be tailored based on individual disease knowledge.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder characterized by abnormal sickle hemoglobin resulting in chronic hemolytic anemia and vaso-occlusion [1]. More than 95% of children with SCD in the United States survive into adulthood; however, young adults (YAs) are at risk for mortality shortly after transfer to adult health care [2–5]. Specifically, YAs with SCD (ages 18 to 30) have increased hospital utilization, emergency department visits, and mortality compared to other age-groups [4–7]. During this critical period, transition preparation that includes improving disease literacy and ensuring medical history knowledge may be necessary for optimal outcomes.

In the extant YA literature, significant gaps in medical history knowledge during the transition period were observed in pediatric cancer and inflammatory bowel disease patients [8,9]. YAs often require multidisciplinary management of their chronic disease complications [10]. Therefore, possessing comprehensive knowledge of personal health history may facilitate communication with different adult care providers and promote continuity of care. In the SCD transition literature, transition readiness measures have been developed to assess several aspects of knowledge, including medical and disease knowledge; however, these measures are primarily self-reported perceptions of knowledge and do not evaluate the accuracy of knowledge [11,12]. The current pilot study addresses this gap with the aim of assessing medical history knowledge accuracy in adolescents with SCD.

Methods

Participants

From March 2011 to January 2014, adolescents (aged 15–18 years) with SCD (any genotype) were approached during their regular health maintenance visits by hematology social workers. They were invited to complete the Personal Health Record (PHR) as an implementation effort of transition preparation within our pediatric SCD program.

Personal Health Record

The PHR was developed through literature review and discussions with area adult hematologists. The form was modeled after first visit intake forms used in adult hematology clinics. It was reviewed by the hematology medical team and the institution’s patient education committee. Prior to implementation, the form was piloted to obtain patient feedback on format and content. The PHR consists of 33 questions with 168 possible items/data points covering 12 domains: personal information (eg, contact information, SCD genotype), health provider information, personal health history (ie, health diagnoses), blood transfusion history, sickle cell pain events, hospitalization history in the previous year, diagnostic testing history (eg, laboratory tests), current medications, immunizations, advance directives, resource information (eg, disability benefits), and activities of daily living. Some questions required patients to check “Yes” or “No” (eg, “Have you been hospitalized in the past year? Have you received flu vaccine?”) while some required a written response (eg, “What medicines do you currently take?”).

Adolescents were instructed to complete the PHR independently without the help of their caregivers. After completing the form, the social worker reviewed the answers and/or asked participants’ perspectives about communicating health information to providers. A copy of the completed PHR was provided to the adolescent to promote continued education regarding medical history knowledge. The retrospective review of the PHR answers and participants’ characteristics was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of consent from participants.

Statistical Methods

PHR answers were compared with each individual’s electronic medical record (EMR) for accuracy of responses. PHR responses were considered accurate only if they matched the information in the EMR. PHR items absent in the EMR were not coded (inability to verify the accuracy of responses) to capture the most accurate depiction of adolescents’ medical history knowledge. Coding was checked by at least 2 coders for response accuracy. Due to lack of EMR information for certain items, we could not verify the accuracy of many PHR items. Therefore, only items with at least 75% of data verified (across all patients who completed the PHR) were included in subsequent analyses.

Using SPSS (version 18), an agreement percentage was calculated for each patient across verifiable items and used as the primary outcome measure of knowledge accuracy. We used t tests to investigate gender or genotype differences in medical history accuracy. To examine genotype differences, we stratified the sample by SCD genotype: HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia and HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia [13].

Results

Patient Characteristics

Knowledge Accuracy Among Adolescents with SCD

Seventeen items in 6 PHR domains had the highest number of data points (at least 75% verified), and therefore were the only items that could be analyzed. Analyzed items included information about sickle cell genotype, eye doctor care, comorbid health issues (eg, asthma), allergies, hospitalizations, surgeries, transfusions, acute chest syndrome (ACS) episodes, eye problems, baseline hemoglobin level, and vaccination history as well as adolescents’ knowledge of current medications, including hydroxyurea, penicillin, and opioid pain medications.

Gender was not significantly associated with overall accuracy (P = 0.36). A significant difference was found in sickle genotype such that individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 8.23; SD = 1.70) were more accurate reporters of their medical history than those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 7.14; SD = 1.75; t(65) = –2.59, P = 0.01). Specifically, those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype were significantly less accurate reporters of vaccination history (meningococcus t(60) = 3.55, P = 0.001; pneumococcus t(60) = 2.46, P = 0.02; hepatitis t(64) = 2.18, P = 0.03, eye problems t(62) = 3.62; P = 0.001, and surgical history t(62) = 2.14, P = 0.04).

Discussion

In the present study, we utilized the PHR to assess the accuracy of medical history knowledge of adolescents with SCD preparing to transition to adult care. Most adolescents were accurate reporters of important disease-relevant information (eg, genotype, transfusion history, hydroxyurea use), which may be a result of these topics being frequently discussed or recently encountered. For example, 97% of adolescents accurately reported penicillin use which may be related to our program’s emphasis on infection prevention education. However, disease knowledge of immunization history, prior ACS events, and opioid medication use might have been more difficult to recall due to the long interval from their occurrence until the completion of the PHR. Further, frequent changes in opioid medication use may have impacted the accuracy of adolescents’ answers with EMR data.

Individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype were more accurate reporters of their medical history, but the magnitude of difference was not large. These individuals tend to have fewer health issues and therefore less health information to recall, leading to higher accuracy. Furthermore, evidence demonstrates that individuals with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype are at greater risk for cerebrovascular events and subsequent cognitive deficits [14], leading to more memory deficits and difficulty understanding and retaining health information [15]. The results suggest that patient health literacy, or an individual’s capacity to understand basic health information [16], may be a mediating factor in assessing for transition readiness. This is especially important given SCD risk for cognitive deficits [17].

Only 17 PHR items were analyzed due to conservative selection of items. Thus the present findings are not representative of the entire medical history. Additionally, the accuracy of medical history knowledge results may be limited by conservatism with abstracting information from the EMR (PHR information was considered accurate if it matched the information found in their EMR). Finally, we did not systematically assess the feasibility and utility of the PHR; ongoing participant feedback would aid in improving the PHR tool and implementation. It would be important to validate the PHR in a larger sample. However, our study is the first to our knowledge to systematically evaluate medical history knowledge among youth with SCD.

Conclusion and Practice Implications

The present study demonstrates that use of the PHR during regular health maintenance visits can help identify gaps in knowledge among adolescents with SCD who are approaching transfer to adult care. Sufficient knowledge of one’s medical history is an important aspect in transition preparation as it can facilitate the communication of medical information, thereby ensuring continuity of care [18,19]. The PHR could be used to teach medical history knowledge, assess a patient’s level of transition readiness at different time points, and identify areas for further targeted intervention. Knowledge tools, such as the PHR, can be investigated prospectively to assess the association of disease literacy and clinical outcomes, serving as a possible predictive instrument for transition health outcomes.

Corresponding author: Jerlym S. Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Dept. of Psychology, 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail Stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02 (PI: Hankins).

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; analysis and interpretation of data, MSZ, KMR, JSP; drafting of article, MSZ, JSP; critical revision of the article, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; provision of study materials or patients, MJ, AP; statistical expertise, KMR; obtaining of funding, JSH; collection and assembly of data, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMR, KMW.

From the Departments of Psychology (Ms. Zhao, Drs. Russell, Wesley, and Porter) and Hematology (Mss. Johnson and Pullen, Dr. Hankins), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

Abstract

- Background: Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) are surviving into adulthood. Mastery of disease knowledge may facilitate treatment continuity in adult care.

- Objective: To assess the accuracy and extent of medical history knowledge among adolescents with SCD through the use of a personal health record (PHR) form.

- Methods: 68 adolescent patients with SCD (52.9% male; mean age, 16.8 years; 100% African American) completed a PHR listing significant prior medical events (eg, disease complications, diagnostic evaluations, treatments). Responses were compared against participants’ electronic medical record. An agreement percentage was calculated to determine accuracy of knowledge.

- Results: Most adolescents correctly reported their sickle cell genotype (100%), usage of penicillin (97.1%), prior hospitalizations (96.5%), history of prior blood transfusions (93.8%), usage of hydroxyurea (88.2%), and allergies (85.2%). Fewer adolescents accurately reported usage of opioids (52.9%), prior acute chest syndrome events (50.9%), baseline hemoglobin (41.8%), and hepatitis (43.3%), pneumovax (30.2%), and menactra (14.5%) vaccinations.

- Conclusion: Adolescents are aware of most but not all aspects of their medical history. The present findings can inform areas of knowledge deficits. Future targeted interventions for transition education and preparation may be tailored based on individual disease knowledge.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder characterized by abnormal sickle hemoglobin resulting in chronic hemolytic anemia and vaso-occlusion [1]. More than 95% of children with SCD in the United States survive into adulthood; however, young adults (YAs) are at risk for mortality shortly after transfer to adult health care [2–5]. Specifically, YAs with SCD (ages 18 to 30) have increased hospital utilization, emergency department visits, and mortality compared to other age-groups [4–7]. During this critical period, transition preparation that includes improving disease literacy and ensuring medical history knowledge may be necessary for optimal outcomes.

In the extant YA literature, significant gaps in medical history knowledge during the transition period were observed in pediatric cancer and inflammatory bowel disease patients [8,9]. YAs often require multidisciplinary management of their chronic disease complications [10]. Therefore, possessing comprehensive knowledge of personal health history may facilitate communication with different adult care providers and promote continuity of care. In the SCD transition literature, transition readiness measures have been developed to assess several aspects of knowledge, including medical and disease knowledge; however, these measures are primarily self-reported perceptions of knowledge and do not evaluate the accuracy of knowledge [11,12]. The current pilot study addresses this gap with the aim of assessing medical history knowledge accuracy in adolescents with SCD.

Methods

Participants

From March 2011 to January 2014, adolescents (aged 15–18 years) with SCD (any genotype) were approached during their regular health maintenance visits by hematology social workers. They were invited to complete the Personal Health Record (PHR) as an implementation effort of transition preparation within our pediatric SCD program.

Personal Health Record

The PHR was developed through literature review and discussions with area adult hematologists. The form was modeled after first visit intake forms used in adult hematology clinics. It was reviewed by the hematology medical team and the institution’s patient education committee. Prior to implementation, the form was piloted to obtain patient feedback on format and content. The PHR consists of 33 questions with 168 possible items/data points covering 12 domains: personal information (eg, contact information, SCD genotype), health provider information, personal health history (ie, health diagnoses), blood transfusion history, sickle cell pain events, hospitalization history in the previous year, diagnostic testing history (eg, laboratory tests), current medications, immunizations, advance directives, resource information (eg, disability benefits), and activities of daily living. Some questions required patients to check “Yes” or “No” (eg, “Have you been hospitalized in the past year? Have you received flu vaccine?”) while some required a written response (eg, “What medicines do you currently take?”).

Adolescents were instructed to complete the PHR independently without the help of their caregivers. After completing the form, the social worker reviewed the answers and/or asked participants’ perspectives about communicating health information to providers. A copy of the completed PHR was provided to the adolescent to promote continued education regarding medical history knowledge. The retrospective review of the PHR answers and participants’ characteristics was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of consent from participants.

Statistical Methods

PHR answers were compared with each individual’s electronic medical record (EMR) for accuracy of responses. PHR responses were considered accurate only if they matched the information in the EMR. PHR items absent in the EMR were not coded (inability to verify the accuracy of responses) to capture the most accurate depiction of adolescents’ medical history knowledge. Coding was checked by at least 2 coders for response accuracy. Due to lack of EMR information for certain items, we could not verify the accuracy of many PHR items. Therefore, only items with at least 75% of data verified (across all patients who completed the PHR) were included in subsequent analyses.

Using SPSS (version 18), an agreement percentage was calculated for each patient across verifiable items and used as the primary outcome measure of knowledge accuracy. We used t tests to investigate gender or genotype differences in medical history accuracy. To examine genotype differences, we stratified the sample by SCD genotype: HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia and HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia [13].

Results

Patient Characteristics

Knowledge Accuracy Among Adolescents with SCD

Seventeen items in 6 PHR domains had the highest number of data points (at least 75% verified), and therefore were the only items that could be analyzed. Analyzed items included information about sickle cell genotype, eye doctor care, comorbid health issues (eg, asthma), allergies, hospitalizations, surgeries, transfusions, acute chest syndrome (ACS) episodes, eye problems, baseline hemoglobin level, and vaccination history as well as adolescents’ knowledge of current medications, including hydroxyurea, penicillin, and opioid pain medications.

Gender was not significantly associated with overall accuracy (P = 0.36). A significant difference was found in sickle genotype such that individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 8.23; SD = 1.70) were more accurate reporters of their medical history than those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 7.14; SD = 1.75; t(65) = –2.59, P = 0.01). Specifically, those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype were significantly less accurate reporters of vaccination history (meningococcus t(60) = 3.55, P = 0.001; pneumococcus t(60) = 2.46, P = 0.02; hepatitis t(64) = 2.18, P = 0.03, eye problems t(62) = 3.62; P = 0.001, and surgical history t(62) = 2.14, P = 0.04).

Discussion

In the present study, we utilized the PHR to assess the accuracy of medical history knowledge of adolescents with SCD preparing to transition to adult care. Most adolescents were accurate reporters of important disease-relevant information (eg, genotype, transfusion history, hydroxyurea use), which may be a result of these topics being frequently discussed or recently encountered. For example, 97% of adolescents accurately reported penicillin use which may be related to our program’s emphasis on infection prevention education. However, disease knowledge of immunization history, prior ACS events, and opioid medication use might have been more difficult to recall due to the long interval from their occurrence until the completion of the PHR. Further, frequent changes in opioid medication use may have impacted the accuracy of adolescents’ answers with EMR data.

Individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype were more accurate reporters of their medical history, but the magnitude of difference was not large. These individuals tend to have fewer health issues and therefore less health information to recall, leading to higher accuracy. Furthermore, evidence demonstrates that individuals with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype are at greater risk for cerebrovascular events and subsequent cognitive deficits [14], leading to more memory deficits and difficulty understanding and retaining health information [15]. The results suggest that patient health literacy, or an individual’s capacity to understand basic health information [16], may be a mediating factor in assessing for transition readiness. This is especially important given SCD risk for cognitive deficits [17].

Only 17 PHR items were analyzed due to conservative selection of items. Thus the present findings are not representative of the entire medical history. Additionally, the accuracy of medical history knowledge results may be limited by conservatism with abstracting information from the EMR (PHR information was considered accurate if it matched the information found in their EMR). Finally, we did not systematically assess the feasibility and utility of the PHR; ongoing participant feedback would aid in improving the PHR tool and implementation. It would be important to validate the PHR in a larger sample. However, our study is the first to our knowledge to systematically evaluate medical history knowledge among youth with SCD.

Conclusion and Practice Implications

The present study demonstrates that use of the PHR during regular health maintenance visits can help identify gaps in knowledge among adolescents with SCD who are approaching transfer to adult care. Sufficient knowledge of one’s medical history is an important aspect in transition preparation as it can facilitate the communication of medical information, thereby ensuring continuity of care [18,19]. The PHR could be used to teach medical history knowledge, assess a patient’s level of transition readiness at different time points, and identify areas for further targeted intervention. Knowledge tools, such as the PHR, can be investigated prospectively to assess the association of disease literacy and clinical outcomes, serving as a possible predictive instrument for transition health outcomes.

Corresponding author: Jerlym S. Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Dept. of Psychology, 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail Stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02 (PI: Hankins).

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; analysis and interpretation of data, MSZ, KMR, JSP; drafting of article, MSZ, JSP; critical revision of the article, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; provision of study materials or patients, MJ, AP; statistical expertise, KMR; obtaining of funding, JSH; collection and assembly of data, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMR, KMW.

1. Quinn CT. Sickle cell disease in childhood: from newborn screening through transition to adult medical care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013;60:1363–81.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:S512–21.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. de Montalembert M, Guitton C. Transition from paediatric to adult care for patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2014;164:630–5.

5. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

6. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

7. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood Jr C. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

8. Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 2002:287:1832–9.

9. Hait EJ, Barendse RM, Arnold JH, et al. Transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: a survey of adult gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:61–5.

10. Kennedy A, Sawyer S. Transition from pediatric to adult services: are we getting it right? Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20:403–9.

11. Sobota A, Akinlonu A, Champigny M, et al. Self-reported transition readiness among young adults with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:389–94.

12. Treadwell M, Johnson S, Sisler I, et al. Development of a sickle cell disease readiness for transition assessment. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2016;28:193–201.

13. Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, et al. Pain characteristics and age-related pain trajectories in infants and young children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:291–6.

14. Venkataraman A, Adams RJ. Neurologic complications of sickle cell disease. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;120:1015–25.

15. Porter JS, Matthews CS, Carroll YM, et al. Genetic education and sickle cell disease: feasibility and efficacy of a program tailored to adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:572–7.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. 2015. Accessed 26 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/index.html.

17. Armstrong FD, Thompson Jr RJ, Wang W, et al. Cognitive functioning and brain magnetic resonance imaging in children with sickle cell disease. Neuropsychology Committee of the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatrics 1996;97:864–70.

18. Kanter J, Kruse-Jarres R. Management of sickle cell disease from childhood through adulthood. Blood Rev 2013;27:279–87.

19. Treadwell M, Telfair J, Gibson RW, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: establishing evidence-based practice and directions for research. Am J Hematol 2011;86:116–2.

1. Quinn CT. Sickle cell disease in childhood: from newborn screening through transition to adult medical care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013;60:1363–81.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:S512–21.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. de Montalembert M, Guitton C. Transition from paediatric to adult care for patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2014;164:630–5.

5. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

6. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

7. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood Jr C. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

8. Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 2002:287:1832–9.

9. Hait EJ, Barendse RM, Arnold JH, et al. Transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: a survey of adult gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:61–5.

10. Kennedy A, Sawyer S. Transition from pediatric to adult services: are we getting it right? Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20:403–9.

11. Sobota A, Akinlonu A, Champigny M, et al. Self-reported transition readiness among young adults with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:389–94.

12. Treadwell M, Johnson S, Sisler I, et al. Development of a sickle cell disease readiness for transition assessment. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2016;28:193–201.

13. Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, et al. Pain characteristics and age-related pain trajectories in infants and young children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:291–6.

14. Venkataraman A, Adams RJ. Neurologic complications of sickle cell disease. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;120:1015–25.

15. Porter JS, Matthews CS, Carroll YM, et al. Genetic education and sickle cell disease: feasibility and efficacy of a program tailored to adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:572–7.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. 2015. Accessed 26 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/index.html.

17. Armstrong FD, Thompson Jr RJ, Wang W, et al. Cognitive functioning and brain magnetic resonance imaging in children with sickle cell disease. Neuropsychology Committee of the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatrics 1996;97:864–70.

18. Kanter J, Kruse-Jarres R. Management of sickle cell disease from childhood through adulthood. Blood Rev 2013;27:279–87.

19. Treadwell M, Telfair J, Gibson RW, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: establishing evidence-based practice and directions for research. Am J Hematol 2011;86:116–2.

Transition Readiness Assessment for Sickle Cell Patients: A Quality Improvement Project

From the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

This article is the fourth in our Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative series. See the related editorial by Oyeku et al in the February 2014 issue of JCOM. (—Ed.)

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to implement an assessment tool to evaluate transition readiness in youth with sickle cell disease (SCD).

- Methods: Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were run to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a provider-based transition readiness assessment.

- Results: Seventy-two adolescents aged 17 years (53% male) were assessed for transition readiness from August 2011 to June 2013. Results indicated that it is feasible for a provider transition readiness assessment (PTRA) tool to be integrated into a transition program. The newly created PTRA tool can inform the level of preparedness of adolescents with SCD during planning for adult transition.

- Conclusion: The PTRA tool may be helpful for planning and preparation of youth with SCD to successfully transition to adult care.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common genetic disorders in the world and is caused by a mutation producing the abnormal sickle hemoglobin. Patients with SCD are living longer and transitioning from pediatric to adult providers. However, the transition years are associated with high mortality [1–4], risk for increased utilization of emergency care, and underutilization of care maintenance visits [5,6]. Successful transition from pediatric care to adult care is critical in ensuring care continuity and optimal health [7]. Barriers to successful transition include lack of preparation for transition [8,9]. To address this limitation, transition programs have been created to help foster transition preparation and readiness.

Often, chronological age determines when SCD programs transfer patients to adult care; however, age is an inadequate measure of readiness. To determine the appropriate time for transition and to individualize the subsequent preparation and planning prior to transfer, an assessment of transition readiness is needed. A number of checklists exist in the unpublished literature (eg, on institution and program websites), and a few empirically tested transition readiness measures have been developed through literature review, semi-structured interviews, and pilot testing in patient samples [10–13]. The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) and TRxANSITION scale are non-disease-specific measures that assess self-management and advocacy skills of youth with special health care needs; the TRAQ is self-report whereas the TRxANSITION scale is provider-administered [10,11]. Disease-specific measures have been developed for pediatric kidney transplant recipients [12] and adolescents with cystic fibrosis [13]. Studies using these measures suggest that transition readiness is associated with age, gender, disease type, increased adolescent responsibility/decreased parental involvement, and adherence [10–12].

For patients with SCD, there is no well-validated measure available to assess transition readiness [14]. Telfair and colleagues developed a sickle cell transfer questionnaire that focused on transition concerns and feelings and suggestions for transition intervention programming from the perspective of adolescents, their primary caregivers, and adults with SCD [15]. In addition, McPherson and colleagues examined SCD transition readiness in 4 areas: prior thought about transition, knowledge about steps to transition, interest in learning more about the transition process, and perceived importance of continuing care with a hematologist as an adult provider [8]. They found that adolescents in general were not prepared for transition but that readiness improved with age [8]. Overall, most readiness measures have involved patient self-report or parent proxy report. No current readiness assessment scales incorporate the provider’s assessment, which could help better define the most appropriate next steps in education and preparation for the upcoming transfer to adult care.

The St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital SCD Transition to Adult Care program was started in 2007 and is a companion program to the SCD teen clinic, serving 250 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years. The transition program curriculum addresses all aspects of the transition process. Based on the curriculum components, St. Jude developed and implemented a transition readiness assessment tool to be completed by providers in the SCD transition program. In this article, we describe our use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to evaluate the utility and impact of the newly created SCD transition readiness assessment tool.

Methods

Transition Program

The transition program is directed by a multidisciplinary team; disciplines represented on the team are medical (hematologist, genetic educator, physician assistant, and nurse coordinators), psychosocial (social workers), emotional/cognitive (psychologists), and academic (academic coordinator). In the program, adolescents with SCD and their families are introduced to the concept of transition to adult care at the age of 12. Every 6 months from 12 to 18 years of age, members of the team address relevant topics with patients to increase patients’ disease knowledge and improve their disease self-management skills. Some of the program components include training in completing a personal health record (PHR), genetic education, academic planning, and independent living skills.

Needs Assessment

Prior to initiation of the project, members of the transition program met monthly to informally discuss the progress of patients who were approaching the age of transition to adult care. We found that adolescents did not appear to be ready or well prepared for transition, including not being aware of the various familial and psychosocial issues that needed to be addressed prior to the transfer to adult care. We realized that these discussions needed to occur earlier to allow more time for preparation and transition planning of the patient, family, and medical team. In addition, members of the team each has differing perspectives and did not have the same information with regard to existing familial and psychosocial issues. The discussions were necessary to ensure all team members had pertinent information to make informed decisions about the patient’s level of transition readiness. Finally, our criteria for readiness were not standardized or quantifiable. As a result, each patient discussion was lengthy, not structured, and not very informative. In 2011, a core group from the transition team attended a Health Resources Services Administration–sponsored Hemoglobinopathies Quality Improvement Workshop to receive training in QI processes. We decided to create a formal, quantitative, individualized assessment of patients’ progress toward transition at age 17.

Readiness Assessment Tool

The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was developed by the pediatric psychologist and pediatric neuropsychologist. Because the psychology service is set up to see patients referred by the medical team and is unable to see all patients coming to hematology clinic, the emotional/cognitive checklist is based on identifying previous utilization of psychological services including psychotherapy and cognitive testing and determining whether initiation of services is warranted. The academic domain checklist was developed by the academic coordinator who serves as a liaison between the medical team and the school system. This checklist assesses whether the adolescent is meeting high school graduation requirements, able to verbalize an educational/job training plan, on track with future planning (eg, completed required testing), knowledgeable about community educational services, and able to self-advocate (eg, apply for SSI benefits).

Items within each domain have equal value (ie, each question on the checklist is worth 1 point) and the sum of points yields the quantifiable assessment of how well patients are performing in each area of their health. Assessment meetings occur monthly when eligible patients are discussed. Domains are evaluated by the health care provider responsible for his/her own domain (eg, social worker completes the psychosocial domain, the academic coordinator completes the academic domain, etc.).

PDSA Methodology

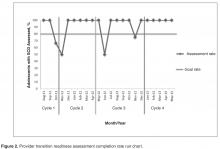

Cycle 1

The objective of the first cycle was to assess feasibility and acceptability of the assessment tool. Patients were assessed during the month of their 17th birthday. Fourteen out of 16 eligible patients (87.5%) were assessed: 1 patient was lost to follow-up, and 1 patient inadvertently was not included in the assessment due to an administrative error. Feedback from the first cycle revealed that some items on the emotional/cognitive domain checklist were not clearly defined, and there was some overlap with the psychosocial domain checklist. Additionally, some items were not readily assessed by psychology based on the structure of psychology services at the institution. Not all patients are seen by psychology; patients are referred to psychology by the team and appointments occur in the psychology clinic and were not well-integrated within the hematology clinic visit.

Cycle 2

The second cycle addressed some of the problems identified during Cycle 1. The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was revised to reflect psychology clinic utilization (psychotherapy and testing) and a section was added where team members could indicate individualized action plans. Seventeen patients out of 18 eligible patients were assessed (94.4%): 1 patient was lost to follow-up. At the conclusion of this cycle, we found that several patients had not completed certain transition program components, such as genetic education or their PHR. Therefore, we decided that we needed to indicate this and create a Plan of Action (POA) to ensure completion of program components. The POA indicated which components were outstanding, when these components would be completed, and when the team would discuss the patient again to track their progress with program components (eg, 6 months later).

Cycle 3

Following a few months using the assessment process, each member of the team provided feedback about their observations from the second cycle. The third cycle of the PDSA addressed some of the barriers identified in Cycle 2 by adding the POA and timeline for reassessment. With this information, the nurse case manager was able to identify and contact families who had significant gaps in the learning curriculum. Additionally, services such as psychological testing were scheduled in a timely manner to address academic problems and to provide rationale for accommodations and academic/vocational services before patients transferred care to the adult provider. With the number of assessed patients increasing, it was determined that a reliable tracking system to monitor progress was essential. Thus, a transition database was created to document the domain scores, individualized plan of action, and other components of the transition program, such as medical literacy quiz scores, completion of pre-transfer visits to adult providers, and completion of the PHR. During this cycle, 20 patients were assessed out of a total of 22 eligible patients (90.9%); 2 patients were lost to follow-up.

Cycle 4

This cycle is currently underway and comprises monthly assessments of eligible 17-year-old patients with SCD. From January 2013 to May 2013 we have assessed 100% of the eligible patients (21/21). All information obtained through the assessment tool is added to the transition database. Future adjustments and modifications are planned for this tool as we continue to evaluate its impact and value.

Discussion

The transition readiness assessment tool was developed to evaluate adolescent patients with SCD aged 17 years regarding their progress in the transition program and level of transition readiness. Most transition readiness measures available in the literature consider the patient and parent perspective but do not include the health care provider perspective or determine if the patient received the information necessary for successful transition. Our readiness assessment tool has been helpful in providing a structured and quantifiable means to identify at-risk patients and families prior to the transfer of care and revealing important gaps in transition planning. It also provides information in a timely manner about points of intervention to ensure patients receive adequate preparation and services (eg, psychological/neuropsychological testing). Additionally, monthly meetings are held during which the tool is scored and discussed, providing an opportunity for members of the transition team to examine patients’ progress toward transition readiness. Finally, completing an individualized tool in a multidisciplinary setting has the added benefit of encouraging increased staff collaboration and creating a venue for ongoing re-evaluation of the QI process.

We achieved our objective of completing the assessment tool for 80% of eligible patients throughout the cycles. The majority of our nonassessed patients was lost to follow-up and had not had a clinic visit in 2 to 3 years. Implementing the tool has provided us with an additional mechanism to verify transition eligibility and has afforded the transition program a systematic way to screen and track patients who are approaching the age of transition and who may have not been seen for an extended period of time. As with any large program following children with special health care and complex needs, the large volume of patients and their complexity may pose a challenge to the program, therefore having an additional tracking system in place may help mitigate possible losses to follow-up. In fact, since the implementation of tool, our team has been able to contact families and in some cases have reinstated services. As a by-product of tool implementation, we have implemented new policies to prevent extended losses to follow-up and patient attrition.

Limitations

A limitation of the assessment tool is that it does not incorporate the perspectives of the other stakeholders (adolescents, parents, adult providers). Further, some of the items in our tool are measuring utilization of services and not specifically transition readiness. As with most transition readiness measures, our provider tool does not have established reliability and validity [14]. We plan to test for reliability and validity once enough data and patient outcomes have been collected. Additionally, because of the small number of patients who have transferred to adult care since implementation of the tool, we did not examine the association between readiness scores and clinical outcomes, such as fulfillment of first adult provider visit and hospital utilization following transition to adult care. As we continue to assess adolescent patients and track their progress following transition, we will be able to examine these associations with a larger group.

Future Plans

Since the implementation of the tool in our program, we have realized that we may need to start assessing patients at an earlier age and perhaps multiple times throughout adolescence. Some of our patients have guardianship and conservatorship issues and require more time to discuss options with the family and put in place the appropriate support and assistance prior to the transfer of care. Further, patients that have low compliance to clinic appointments are not receiving all elements of the transition program curriculum and in turn have fewer opportunities to prepare for transition. To address some of our current limitations, we plan to incorporate a patient and parent readiness assessment and examine the associations between the provider assessment and patient information such as medical literacy quizzes, clinic compliance, and fulfillment of the first adult provider visit. Assessment from all 3 perspectives (patient, parent, and provider) will offer a 360-degree view of transition readiness perception which should improve our ability to identify at-risk families and tailor transition planning to address barriers to care. In addition, our future plans include development of a mechanism to inform patients and families about the domain scores and action plans following the transition readiness meetings and include scores into the electronic medical records. Finally, the readiness assessment tool has revealed some gaps in our transition educational curriculum. Most of our transition learning involves providing and evaluating information provided, but we are not systematically assessing actual acquired transition skills. We are in the process of developing and implementing skill-based learning for activities such as calling to make or reschedule an appointment with an adult provider, arranging transportation, etc.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the provider transition readiness assessment has been a helpful tool to monitor progress of adolescents with SCD towards readiness for transition. The QI methodology and PDSA cycle approach has not only allowed for testing, development, and implementation of the tool, but is also allowing ongoing systematic refinement of our instrument. This approach highlighted the psychosocial challenges of our families as they move toward the transfer of care, in addition to the need for more individualized planning. The next important step is to evaluate the validity and reliability of the measure so we can better evaluate the impact of transition programming on the transfer from pediatric to adult care. We found the PDSA cycle approach to be a framework that can efficiently and systematically improve the quality of care of transitioning patients with SCD and their families.

Corresponding author: Jerlym Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hosp., 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38(4 Suppl):S512–S521.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood C, Jr. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

5. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

6. Hemker BG, Brousseau DC, Yan K, et al. When children with sickle-cell disease become adults: lack of outpatient care leads to increased use of the emergency department. Am J Hematol 2011;86:863–5.

7. Jordan L, Swerdlow P, Coates TD. Systematic review of transition from adolescent to adult care in patients with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:165–9.

8. McPherson M, Thaniel L, Minniti CP. Transition of patients with sickle cell disease from pediatric to adult care: assessing patient readiness. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;52:838–41.

9. Lebensburger JD, Bemrich-Stolz CJ, Howard TH. Barriers in transition from pediatrics to adult medicine in sickle cell anemia. J Blood Med 2012;3:105–12.

10. Sawicki GS, Lukens-Bull K, Yin X, et al. Measuring the transition readiness of youth with special healthcare needs: validation of the TRAQ--Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire. J Pediatr Psychol 2011;36:160–71.

11. Ferris ME, Harward DH, Bickford K, et al. A clinical tool to measure the components of health-care transition from pediatric care to adult care: the UNC TR(x)ANSITION scale. Ren Fail 2012;34:744–53.

12. Gilleland J, Amaral S, Mee L, Blount R. Getting ready to leave: transition readiness in adolescent kidney transplant recipients. J Pediatr Psychol 2012;37:85–96.

13. Cappelli M, MacDonald NE, McGrath PJ. Assessment of readiness to transfer to adult care for adolescents with cystic fibrosis. Child Health Care 1989;18:218–24.

14. Stinson J, Kohut SA, Spiegel L, et al. A systematic review of transition readiness and transfer satisfaction measures for adolescents with chronic illness. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2013:1–16.

15. Telfair J, Myers J, Drezner S. Transfer as a component of the transition of adolescents with sickle cell disease to adult care: adolescent, adult, and parent perspectives. J Adolesc Health 1994;15:558–65.

16. Walley P, Gowland B. Completing the circle: from PD to PDSA. Int J Health Care Qual Assur Inc Leadersh Health Serv 2004;17:349–58.

From the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

This article is the fourth in our Hemoglobinopathy Learning Collaborative series. See the related editorial by Oyeku et al in the February 2014 issue of JCOM. (—Ed.)

Abstract

- Objective: To describe the use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to implement an assessment tool to evaluate transition readiness in youth with sickle cell disease (SCD).

- Methods: Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were run to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of a provider-based transition readiness assessment.

- Results: Seventy-two adolescents aged 17 years (53% male) were assessed for transition readiness from August 2011 to June 2013. Results indicated that it is feasible for a provider transition readiness assessment (PTRA) tool to be integrated into a transition program. The newly created PTRA tool can inform the level of preparedness of adolescents with SCD during planning for adult transition.

- Conclusion: The PTRA tool may be helpful for planning and preparation of youth with SCD to successfully transition to adult care.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is one of the most common genetic disorders in the world and is caused by a mutation producing the abnormal sickle hemoglobin. Patients with SCD are living longer and transitioning from pediatric to adult providers. However, the transition years are associated with high mortality [1–4], risk for increased utilization of emergency care, and underutilization of care maintenance visits [5,6]. Successful transition from pediatric care to adult care is critical in ensuring care continuity and optimal health [7]. Barriers to successful transition include lack of preparation for transition [8,9]. To address this limitation, transition programs have been created to help foster transition preparation and readiness.

Often, chronological age determines when SCD programs transfer patients to adult care; however, age is an inadequate measure of readiness. To determine the appropriate time for transition and to individualize the subsequent preparation and planning prior to transfer, an assessment of transition readiness is needed. A number of checklists exist in the unpublished literature (eg, on institution and program websites), and a few empirically tested transition readiness measures have been developed through literature review, semi-structured interviews, and pilot testing in patient samples [10–13]. The Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ) and TRxANSITION scale are non-disease-specific measures that assess self-management and advocacy skills of youth with special health care needs; the TRAQ is self-report whereas the TRxANSITION scale is provider-administered [10,11]. Disease-specific measures have been developed for pediatric kidney transplant recipients [12] and adolescents with cystic fibrosis [13]. Studies using these measures suggest that transition readiness is associated with age, gender, disease type, increased adolescent responsibility/decreased parental involvement, and adherence [10–12].

For patients with SCD, there is no well-validated measure available to assess transition readiness [14]. Telfair and colleagues developed a sickle cell transfer questionnaire that focused on transition concerns and feelings and suggestions for transition intervention programming from the perspective of adolescents, their primary caregivers, and adults with SCD [15]. In addition, McPherson and colleagues examined SCD transition readiness in 4 areas: prior thought about transition, knowledge about steps to transition, interest in learning more about the transition process, and perceived importance of continuing care with a hematologist as an adult provider [8]. They found that adolescents in general were not prepared for transition but that readiness improved with age [8]. Overall, most readiness measures have involved patient self-report or parent proxy report. No current readiness assessment scales incorporate the provider’s assessment, which could help better define the most appropriate next steps in education and preparation for the upcoming transfer to adult care.

The St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital SCD Transition to Adult Care program was started in 2007 and is a companion program to the SCD teen clinic, serving 250 adolescents aged 12 to 18 years. The transition program curriculum addresses all aspects of the transition process. Based on the curriculum components, St. Jude developed and implemented a transition readiness assessment tool to be completed by providers in the SCD transition program. In this article, we describe our use of quality improvement (QI) methodology to evaluate the utility and impact of the newly created SCD transition readiness assessment tool.

Methods

Transition Program

The transition program is directed by a multidisciplinary team; disciplines represented on the team are medical (hematologist, genetic educator, physician assistant, and nurse coordinators), psychosocial (social workers), emotional/cognitive (psychologists), and academic (academic coordinator). In the program, adolescents with SCD and their families are introduced to the concept of transition to adult care at the age of 12. Every 6 months from 12 to 18 years of age, members of the team address relevant topics with patients to increase patients’ disease knowledge and improve their disease self-management skills. Some of the program components include training in completing a personal health record (PHR), genetic education, academic planning, and independent living skills.

Needs Assessment

Prior to initiation of the project, members of the transition program met monthly to informally discuss the progress of patients who were approaching the age of transition to adult care. We found that adolescents did not appear to be ready or well prepared for transition, including not being aware of the various familial and psychosocial issues that needed to be addressed prior to the transfer to adult care. We realized that these discussions needed to occur earlier to allow more time for preparation and transition planning of the patient, family, and medical team. In addition, members of the team each has differing perspectives and did not have the same information with regard to existing familial and psychosocial issues. The discussions were necessary to ensure all team members had pertinent information to make informed decisions about the patient’s level of transition readiness. Finally, our criteria for readiness were not standardized or quantifiable. As a result, each patient discussion was lengthy, not structured, and not very informative. In 2011, a core group from the transition team attended a Health Resources Services Administration–sponsored Hemoglobinopathies Quality Improvement Workshop to receive training in QI processes. We decided to create a formal, quantitative, individualized assessment of patients’ progress toward transition at age 17.

Readiness Assessment Tool

The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was developed by the pediatric psychologist and pediatric neuropsychologist. Because the psychology service is set up to see patients referred by the medical team and is unable to see all patients coming to hematology clinic, the emotional/cognitive checklist is based on identifying previous utilization of psychological services including psychotherapy and cognitive testing and determining whether initiation of services is warranted. The academic domain checklist was developed by the academic coordinator who serves as a liaison between the medical team and the school system. This checklist assesses whether the adolescent is meeting high school graduation requirements, able to verbalize an educational/job training plan, on track with future planning (eg, completed required testing), knowledgeable about community educational services, and able to self-advocate (eg, apply for SSI benefits).

Items within each domain have equal value (ie, each question on the checklist is worth 1 point) and the sum of points yields the quantifiable assessment of how well patients are performing in each area of their health. Assessment meetings occur monthly when eligible patients are discussed. Domains are evaluated by the health care provider responsible for his/her own domain (eg, social worker completes the psychosocial domain, the academic coordinator completes the academic domain, etc.).

PDSA Methodology

Cycle 1

The objective of the first cycle was to assess feasibility and acceptability of the assessment tool. Patients were assessed during the month of their 17th birthday. Fourteen out of 16 eligible patients (87.5%) were assessed: 1 patient was lost to follow-up, and 1 patient inadvertently was not included in the assessment due to an administrative error. Feedback from the first cycle revealed that some items on the emotional/cognitive domain checklist were not clearly defined, and there was some overlap with the psychosocial domain checklist. Additionally, some items were not readily assessed by psychology based on the structure of psychology services at the institution. Not all patients are seen by psychology; patients are referred to psychology by the team and appointments occur in the psychology clinic and were not well-integrated within the hematology clinic visit.

Cycle 2

The second cycle addressed some of the problems identified during Cycle 1. The emotional/cognitive domain checklist was revised to reflect psychology clinic utilization (psychotherapy and testing) and a section was added where team members could indicate individualized action plans. Seventeen patients out of 18 eligible patients were assessed (94.4%): 1 patient was lost to follow-up. At the conclusion of this cycle, we found that several patients had not completed certain transition program components, such as genetic education or their PHR. Therefore, we decided that we needed to indicate this and create a Plan of Action (POA) to ensure completion of program components. The POA indicated which components were outstanding, when these components would be completed, and when the team would discuss the patient again to track their progress with program components (eg, 6 months later).

Cycle 3

Following a few months using the assessment process, each member of the team provided feedback about their observations from the second cycle. The third cycle of the PDSA addressed some of the barriers identified in Cycle 2 by adding the POA and timeline for reassessment. With this information, the nurse case manager was able to identify and contact families who had significant gaps in the learning curriculum. Additionally, services such as psychological testing were scheduled in a timely manner to address academic problems and to provide rationale for accommodations and academic/vocational services before patients transferred care to the adult provider. With the number of assessed patients increasing, it was determined that a reliable tracking system to monitor progress was essential. Thus, a transition database was created to document the domain scores, individualized plan of action, and other components of the transition program, such as medical literacy quiz scores, completion of pre-transfer visits to adult providers, and completion of the PHR. During this cycle, 20 patients were assessed out of a total of 22 eligible patients (90.9%); 2 patients were lost to follow-up.

Cycle 4

This cycle is currently underway and comprises monthly assessments of eligible 17-year-old patients with SCD. From January 2013 to May 2013 we have assessed 100% of the eligible patients (21/21). All information obtained through the assessment tool is added to the transition database. Future adjustments and modifications are planned for this tool as we continue to evaluate its impact and value.

Discussion

The transition readiness assessment tool was developed to evaluate adolescent patients with SCD aged 17 years regarding their progress in the transition program and level of transition readiness. Most transition readiness measures available in the literature consider the patient and parent perspective but do not include the health care provider perspective or determine if the patient received the information necessary for successful transition. Our readiness assessment tool has been helpful in providing a structured and quantifiable means to identify at-risk patients and families prior to the transfer of care and revealing important gaps in transition planning. It also provides information in a timely manner about points of intervention to ensure patients receive adequate preparation and services (eg, psychological/neuropsychological testing). Additionally, monthly meetings are held during which the tool is scored and discussed, providing an opportunity for members of the transition team to examine patients’ progress toward transition readiness. Finally, completing an individualized tool in a multidisciplinary setting has the added benefit of encouraging increased staff collaboration and creating a venue for ongoing re-evaluation of the QI process.