User login

Assessment of Personal Medical History Knowledge in Adolescents with Sickle Cell Disease: A Pilot Study

From the Departments of Psychology (Ms. Zhao, Drs. Russell, Wesley, and Porter) and Hematology (Mss. Johnson and Pullen, Dr. Hankins), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

Abstract

- Background: Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) are surviving into adulthood. Mastery of disease knowledge may facilitate treatment continuity in adult care.

- Objective: To assess the accuracy and extent of medical history knowledge among adolescents with SCD through the use of a personal health record (PHR) form.

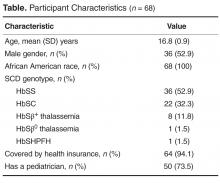

- Methods: 68 adolescent patients with SCD (52.9% male; mean age, 16.8 years; 100% African American) completed a PHR listing significant prior medical events (eg, disease complications, diagnostic evaluations, treatments). Responses were compared against participants’ electronic medical record. An agreement percentage was calculated to determine accuracy of knowledge.

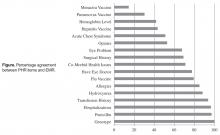

- Results: Most adolescents correctly reported their sickle cell genotype (100%), usage of penicillin (97.1%), prior hospitalizations (96.5%), history of prior blood transfusions (93.8%), usage of hydroxyurea (88.2%), and allergies (85.2%). Fewer adolescents accurately reported usage of opioids (52.9%), prior acute chest syndrome events (50.9%), baseline hemoglobin (41.8%), and hepatitis (43.3%), pneumovax (30.2%), and menactra (14.5%) vaccinations.

- Conclusion: Adolescents are aware of most but not all aspects of their medical history. The present findings can inform areas of knowledge deficits. Future targeted interventions for transition education and preparation may be tailored based on individual disease knowledge.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder characterized by abnormal sickle hemoglobin resulting in chronic hemolytic anemia and vaso-occlusion [1]. More than 95% of children with SCD in the United States survive into adulthood; however, young adults (YAs) are at risk for mortality shortly after transfer to adult health care [2–5]. Specifically, YAs with SCD (ages 18 to 30) have increased hospital utilization, emergency department visits, and mortality compared to other age-groups [4–7]. During this critical period, transition preparation that includes improving disease literacy and ensuring medical history knowledge may be necessary for optimal outcomes.

In the extant YA literature, significant gaps in medical history knowledge during the transition period were observed in pediatric cancer and inflammatory bowel disease patients [8,9]. YAs often require multidisciplinary management of their chronic disease complications [10]. Therefore, possessing comprehensive knowledge of personal health history may facilitate communication with different adult care providers and promote continuity of care. In the SCD transition literature, transition readiness measures have been developed to assess several aspects of knowledge, including medical and disease knowledge; however, these measures are primarily self-reported perceptions of knowledge and do not evaluate the accuracy of knowledge [11,12]. The current pilot study addresses this gap with the aim of assessing medical history knowledge accuracy in adolescents with SCD.

Methods

Participants

From March 2011 to January 2014, adolescents (aged 15–18 years) with SCD (any genotype) were approached during their regular health maintenance visits by hematology social workers. They were invited to complete the Personal Health Record (PHR) as an implementation effort of transition preparation within our pediatric SCD program.

Personal Health Record

The PHR was developed through literature review and discussions with area adult hematologists. The form was modeled after first visit intake forms used in adult hematology clinics. It was reviewed by the hematology medical team and the institution’s patient education committee. Prior to implementation, the form was piloted to obtain patient feedback on format and content. The PHR consists of 33 questions with 168 possible items/data points covering 12 domains: personal information (eg, contact information, SCD genotype), health provider information, personal health history (ie, health diagnoses), blood transfusion history, sickle cell pain events, hospitalization history in the previous year, diagnostic testing history (eg, laboratory tests), current medications, immunizations, advance directives, resource information (eg, disability benefits), and activities of daily living. Some questions required patients to check “Yes” or “No” (eg, “Have you been hospitalized in the past year? Have you received flu vaccine?”) while some required a written response (eg, “What medicines do you currently take?”).

Adolescents were instructed to complete the PHR independently without the help of their caregivers. After completing the form, the social worker reviewed the answers and/or asked participants’ perspectives about communicating health information to providers. A copy of the completed PHR was provided to the adolescent to promote continued education regarding medical history knowledge. The retrospective review of the PHR answers and participants’ characteristics was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of consent from participants.

Statistical Methods

PHR answers were compared with each individual’s electronic medical record (EMR) for accuracy of responses. PHR responses were considered accurate only if they matched the information in the EMR. PHR items absent in the EMR were not coded (inability to verify the accuracy of responses) to capture the most accurate depiction of adolescents’ medical history knowledge. Coding was checked by at least 2 coders for response accuracy. Due to lack of EMR information for certain items, we could not verify the accuracy of many PHR items. Therefore, only items with at least 75% of data verified (across all patients who completed the PHR) were included in subsequent analyses.

Using SPSS (version 18), an agreement percentage was calculated for each patient across verifiable items and used as the primary outcome measure of knowledge accuracy. We used t tests to investigate gender or genotype differences in medical history accuracy. To examine genotype differences, we stratified the sample by SCD genotype: HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia and HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia [13].

Results

Patient Characteristics

Knowledge Accuracy Among Adolescents with SCD

Seventeen items in 6 PHR domains had the highest number of data points (at least 75% verified), and therefore were the only items that could be analyzed. Analyzed items included information about sickle cell genotype, eye doctor care, comorbid health issues (eg, asthma), allergies, hospitalizations, surgeries, transfusions, acute chest syndrome (ACS) episodes, eye problems, baseline hemoglobin level, and vaccination history as well as adolescents’ knowledge of current medications, including hydroxyurea, penicillin, and opioid pain medications.

Gender was not significantly associated with overall accuracy (P = 0.36). A significant difference was found in sickle genotype such that individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 8.23; SD = 1.70) were more accurate reporters of their medical history than those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 7.14; SD = 1.75; t(65) = –2.59, P = 0.01). Specifically, those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype were significantly less accurate reporters of vaccination history (meningococcus t(60) = 3.55, P = 0.001; pneumococcus t(60) = 2.46, P = 0.02; hepatitis t(64) = 2.18, P = 0.03, eye problems t(62) = 3.62; P = 0.001, and surgical history t(62) = 2.14, P = 0.04).

Discussion

In the present study, we utilized the PHR to assess the accuracy of medical history knowledge of adolescents with SCD preparing to transition to adult care. Most adolescents were accurate reporters of important disease-relevant information (eg, genotype, transfusion history, hydroxyurea use), which may be a result of these topics being frequently discussed or recently encountered. For example, 97% of adolescents accurately reported penicillin use which may be related to our program’s emphasis on infection prevention education. However, disease knowledge of immunization history, prior ACS events, and opioid medication use might have been more difficult to recall due to the long interval from their occurrence until the completion of the PHR. Further, frequent changes in opioid medication use may have impacted the accuracy of adolescents’ answers with EMR data.

Individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype were more accurate reporters of their medical history, but the magnitude of difference was not large. These individuals tend to have fewer health issues and therefore less health information to recall, leading to higher accuracy. Furthermore, evidence demonstrates that individuals with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype are at greater risk for cerebrovascular events and subsequent cognitive deficits [14], leading to more memory deficits and difficulty understanding and retaining health information [15]. The results suggest that patient health literacy, or an individual’s capacity to understand basic health information [16], may be a mediating factor in assessing for transition readiness. This is especially important given SCD risk for cognitive deficits [17].

Only 17 PHR items were analyzed due to conservative selection of items. Thus the present findings are not representative of the entire medical history. Additionally, the accuracy of medical history knowledge results may be limited by conservatism with abstracting information from the EMR (PHR information was considered accurate if it matched the information found in their EMR). Finally, we did not systematically assess the feasibility and utility of the PHR; ongoing participant feedback would aid in improving the PHR tool and implementation. It would be important to validate the PHR in a larger sample. However, our study is the first to our knowledge to systematically evaluate medical history knowledge among youth with SCD.

Conclusion and Practice Implications

The present study demonstrates that use of the PHR during regular health maintenance visits can help identify gaps in knowledge among adolescents with SCD who are approaching transfer to adult care. Sufficient knowledge of one’s medical history is an important aspect in transition preparation as it can facilitate the communication of medical information, thereby ensuring continuity of care [18,19]. The PHR could be used to teach medical history knowledge, assess a patient’s level of transition readiness at different time points, and identify areas for further targeted intervention. Knowledge tools, such as the PHR, can be investigated prospectively to assess the association of disease literacy and clinical outcomes, serving as a possible predictive instrument for transition health outcomes.

Corresponding author: Jerlym S. Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Dept. of Psychology, 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail Stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02 (PI: Hankins).

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; analysis and interpretation of data, MSZ, KMR, JSP; drafting of article, MSZ, JSP; critical revision of the article, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; provision of study materials or patients, MJ, AP; statistical expertise, KMR; obtaining of funding, JSH; collection and assembly of data, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMR, KMW.

1. Quinn CT. Sickle cell disease in childhood: from newborn screening through transition to adult medical care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013;60:1363–81.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:S512–21.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. de Montalembert M, Guitton C. Transition from paediatric to adult care for patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2014;164:630–5.

5. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

6. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

7. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood Jr C. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

8. Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 2002:287:1832–9.

9. Hait EJ, Barendse RM, Arnold JH, et al. Transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: a survey of adult gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:61–5.

10. Kennedy A, Sawyer S. Transition from pediatric to adult services: are we getting it right? Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20:403–9.

11. Sobota A, Akinlonu A, Champigny M, et al. Self-reported transition readiness among young adults with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:389–94.

12. Treadwell M, Johnson S, Sisler I, et al. Development of a sickle cell disease readiness for transition assessment. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2016;28:193–201.

13. Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, et al. Pain characteristics and age-related pain trajectories in infants and young children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:291–6.

14. Venkataraman A, Adams RJ. Neurologic complications of sickle cell disease. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;120:1015–25.

15. Porter JS, Matthews CS, Carroll YM, et al. Genetic education and sickle cell disease: feasibility and efficacy of a program tailored to adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:572–7.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. 2015. Accessed 26 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/index.html.

17. Armstrong FD, Thompson Jr RJ, Wang W, et al. Cognitive functioning and brain magnetic resonance imaging in children with sickle cell disease. Neuropsychology Committee of the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatrics 1996;97:864–70.

18. Kanter J, Kruse-Jarres R. Management of sickle cell disease from childhood through adulthood. Blood Rev 2013;27:279–87.

19. Treadwell M, Telfair J, Gibson RW, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: establishing evidence-based practice and directions for research. Am J Hematol 2011;86:116–2.

From the Departments of Psychology (Ms. Zhao, Drs. Russell, Wesley, and Porter) and Hematology (Mss. Johnson and Pullen, Dr. Hankins), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

Abstract

- Background: Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) are surviving into adulthood. Mastery of disease knowledge may facilitate treatment continuity in adult care.

- Objective: To assess the accuracy and extent of medical history knowledge among adolescents with SCD through the use of a personal health record (PHR) form.

- Methods: 68 adolescent patients with SCD (52.9% male; mean age, 16.8 years; 100% African American) completed a PHR listing significant prior medical events (eg, disease complications, diagnostic evaluations, treatments). Responses were compared against participants’ electronic medical record. An agreement percentage was calculated to determine accuracy of knowledge.

- Results: Most adolescents correctly reported their sickle cell genotype (100%), usage of penicillin (97.1%), prior hospitalizations (96.5%), history of prior blood transfusions (93.8%), usage of hydroxyurea (88.2%), and allergies (85.2%). Fewer adolescents accurately reported usage of opioids (52.9%), prior acute chest syndrome events (50.9%), baseline hemoglobin (41.8%), and hepatitis (43.3%), pneumovax (30.2%), and menactra (14.5%) vaccinations.

- Conclusion: Adolescents are aware of most but not all aspects of their medical history. The present findings can inform areas of knowledge deficits. Future targeted interventions for transition education and preparation may be tailored based on individual disease knowledge.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder characterized by abnormal sickle hemoglobin resulting in chronic hemolytic anemia and vaso-occlusion [1]. More than 95% of children with SCD in the United States survive into adulthood; however, young adults (YAs) are at risk for mortality shortly after transfer to adult health care [2–5]. Specifically, YAs with SCD (ages 18 to 30) have increased hospital utilization, emergency department visits, and mortality compared to other age-groups [4–7]. During this critical period, transition preparation that includes improving disease literacy and ensuring medical history knowledge may be necessary for optimal outcomes.

In the extant YA literature, significant gaps in medical history knowledge during the transition period were observed in pediatric cancer and inflammatory bowel disease patients [8,9]. YAs often require multidisciplinary management of their chronic disease complications [10]. Therefore, possessing comprehensive knowledge of personal health history may facilitate communication with different adult care providers and promote continuity of care. In the SCD transition literature, transition readiness measures have been developed to assess several aspects of knowledge, including medical and disease knowledge; however, these measures are primarily self-reported perceptions of knowledge and do not evaluate the accuracy of knowledge [11,12]. The current pilot study addresses this gap with the aim of assessing medical history knowledge accuracy in adolescents with SCD.

Methods

Participants

From March 2011 to January 2014, adolescents (aged 15–18 years) with SCD (any genotype) were approached during their regular health maintenance visits by hematology social workers. They were invited to complete the Personal Health Record (PHR) as an implementation effort of transition preparation within our pediatric SCD program.

Personal Health Record

The PHR was developed through literature review and discussions with area adult hematologists. The form was modeled after first visit intake forms used in adult hematology clinics. It was reviewed by the hematology medical team and the institution’s patient education committee. Prior to implementation, the form was piloted to obtain patient feedback on format and content. The PHR consists of 33 questions with 168 possible items/data points covering 12 domains: personal information (eg, contact information, SCD genotype), health provider information, personal health history (ie, health diagnoses), blood transfusion history, sickle cell pain events, hospitalization history in the previous year, diagnostic testing history (eg, laboratory tests), current medications, immunizations, advance directives, resource information (eg, disability benefits), and activities of daily living. Some questions required patients to check “Yes” or “No” (eg, “Have you been hospitalized in the past year? Have you received flu vaccine?”) while some required a written response (eg, “What medicines do you currently take?”).

Adolescents were instructed to complete the PHR independently without the help of their caregivers. After completing the form, the social worker reviewed the answers and/or asked participants’ perspectives about communicating health information to providers. A copy of the completed PHR was provided to the adolescent to promote continued education regarding medical history knowledge. The retrospective review of the PHR answers and participants’ characteristics was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of consent from participants.

Statistical Methods

PHR answers were compared with each individual’s electronic medical record (EMR) for accuracy of responses. PHR responses were considered accurate only if they matched the information in the EMR. PHR items absent in the EMR were not coded (inability to verify the accuracy of responses) to capture the most accurate depiction of adolescents’ medical history knowledge. Coding was checked by at least 2 coders for response accuracy. Due to lack of EMR information for certain items, we could not verify the accuracy of many PHR items. Therefore, only items with at least 75% of data verified (across all patients who completed the PHR) were included in subsequent analyses.

Using SPSS (version 18), an agreement percentage was calculated for each patient across verifiable items and used as the primary outcome measure of knowledge accuracy. We used t tests to investigate gender or genotype differences in medical history accuracy. To examine genotype differences, we stratified the sample by SCD genotype: HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia and HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia [13].

Results

Patient Characteristics

Knowledge Accuracy Among Adolescents with SCD

Seventeen items in 6 PHR domains had the highest number of data points (at least 75% verified), and therefore were the only items that could be analyzed. Analyzed items included information about sickle cell genotype, eye doctor care, comorbid health issues (eg, asthma), allergies, hospitalizations, surgeries, transfusions, acute chest syndrome (ACS) episodes, eye problems, baseline hemoglobin level, and vaccination history as well as adolescents’ knowledge of current medications, including hydroxyurea, penicillin, and opioid pain medications.

Gender was not significantly associated with overall accuracy (P = 0.36). A significant difference was found in sickle genotype such that individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 8.23; SD = 1.70) were more accurate reporters of their medical history than those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 7.14; SD = 1.75; t(65) = –2.59, P = 0.01). Specifically, those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype were significantly less accurate reporters of vaccination history (meningococcus t(60) = 3.55, P = 0.001; pneumococcus t(60) = 2.46, P = 0.02; hepatitis t(64) = 2.18, P = 0.03, eye problems t(62) = 3.62; P = 0.001, and surgical history t(62) = 2.14, P = 0.04).

Discussion

In the present study, we utilized the PHR to assess the accuracy of medical history knowledge of adolescents with SCD preparing to transition to adult care. Most adolescents were accurate reporters of important disease-relevant information (eg, genotype, transfusion history, hydroxyurea use), which may be a result of these topics being frequently discussed or recently encountered. For example, 97% of adolescents accurately reported penicillin use which may be related to our program’s emphasis on infection prevention education. However, disease knowledge of immunization history, prior ACS events, and opioid medication use might have been more difficult to recall due to the long interval from their occurrence until the completion of the PHR. Further, frequent changes in opioid medication use may have impacted the accuracy of adolescents’ answers with EMR data.

Individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype were more accurate reporters of their medical history, but the magnitude of difference was not large. These individuals tend to have fewer health issues and therefore less health information to recall, leading to higher accuracy. Furthermore, evidence demonstrates that individuals with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype are at greater risk for cerebrovascular events and subsequent cognitive deficits [14], leading to more memory deficits and difficulty understanding and retaining health information [15]. The results suggest that patient health literacy, or an individual’s capacity to understand basic health information [16], may be a mediating factor in assessing for transition readiness. This is especially important given SCD risk for cognitive deficits [17].

Only 17 PHR items were analyzed due to conservative selection of items. Thus the present findings are not representative of the entire medical history. Additionally, the accuracy of medical history knowledge results may be limited by conservatism with abstracting information from the EMR (PHR information was considered accurate if it matched the information found in their EMR). Finally, we did not systematically assess the feasibility and utility of the PHR; ongoing participant feedback would aid in improving the PHR tool and implementation. It would be important to validate the PHR in a larger sample. However, our study is the first to our knowledge to systematically evaluate medical history knowledge among youth with SCD.

Conclusion and Practice Implications

The present study demonstrates that use of the PHR during regular health maintenance visits can help identify gaps in knowledge among adolescents with SCD who are approaching transfer to adult care. Sufficient knowledge of one’s medical history is an important aspect in transition preparation as it can facilitate the communication of medical information, thereby ensuring continuity of care [18,19]. The PHR could be used to teach medical history knowledge, assess a patient’s level of transition readiness at different time points, and identify areas for further targeted intervention. Knowledge tools, such as the PHR, can be investigated prospectively to assess the association of disease literacy and clinical outcomes, serving as a possible predictive instrument for transition health outcomes.

Corresponding author: Jerlym S. Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Dept. of Psychology, 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail Stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02 (PI: Hankins).

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; analysis and interpretation of data, MSZ, KMR, JSP; drafting of article, MSZ, JSP; critical revision of the article, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; provision of study materials or patients, MJ, AP; statistical expertise, KMR; obtaining of funding, JSH; collection and assembly of data, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMR, KMW.

From the Departments of Psychology (Ms. Zhao, Drs. Russell, Wesley, and Porter) and Hematology (Mss. Johnson and Pullen, Dr. Hankins), St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Memphis, TN.

Abstract

- Background: Children with sickle cell disease (SCD) are surviving into adulthood. Mastery of disease knowledge may facilitate treatment continuity in adult care.

- Objective: To assess the accuracy and extent of medical history knowledge among adolescents with SCD through the use of a personal health record (PHR) form.

- Methods: 68 adolescent patients with SCD (52.9% male; mean age, 16.8 years; 100% African American) completed a PHR listing significant prior medical events (eg, disease complications, diagnostic evaluations, treatments). Responses were compared against participants’ electronic medical record. An agreement percentage was calculated to determine accuracy of knowledge.

- Results: Most adolescents correctly reported their sickle cell genotype (100%), usage of penicillin (97.1%), prior hospitalizations (96.5%), history of prior blood transfusions (93.8%), usage of hydroxyurea (88.2%), and allergies (85.2%). Fewer adolescents accurately reported usage of opioids (52.9%), prior acute chest syndrome events (50.9%), baseline hemoglobin (41.8%), and hepatitis (43.3%), pneumovax (30.2%), and menactra (14.5%) vaccinations.

- Conclusion: Adolescents are aware of most but not all aspects of their medical history. The present findings can inform areas of knowledge deficits. Future targeted interventions for transition education and preparation may be tailored based on individual disease knowledge.

Sickle cell disease (SCD) is a genetic disorder characterized by abnormal sickle hemoglobin resulting in chronic hemolytic anemia and vaso-occlusion [1]. More than 95% of children with SCD in the United States survive into adulthood; however, young adults (YAs) are at risk for mortality shortly after transfer to adult health care [2–5]. Specifically, YAs with SCD (ages 18 to 30) have increased hospital utilization, emergency department visits, and mortality compared to other age-groups [4–7]. During this critical period, transition preparation that includes improving disease literacy and ensuring medical history knowledge may be necessary for optimal outcomes.

In the extant YA literature, significant gaps in medical history knowledge during the transition period were observed in pediatric cancer and inflammatory bowel disease patients [8,9]. YAs often require multidisciplinary management of their chronic disease complications [10]. Therefore, possessing comprehensive knowledge of personal health history may facilitate communication with different adult care providers and promote continuity of care. In the SCD transition literature, transition readiness measures have been developed to assess several aspects of knowledge, including medical and disease knowledge; however, these measures are primarily self-reported perceptions of knowledge and do not evaluate the accuracy of knowledge [11,12]. The current pilot study addresses this gap with the aim of assessing medical history knowledge accuracy in adolescents with SCD.

Methods

Participants

From March 2011 to January 2014, adolescents (aged 15–18 years) with SCD (any genotype) were approached during their regular health maintenance visits by hematology social workers. They were invited to complete the Personal Health Record (PHR) as an implementation effort of transition preparation within our pediatric SCD program.

Personal Health Record

The PHR was developed through literature review and discussions with area adult hematologists. The form was modeled after first visit intake forms used in adult hematology clinics. It was reviewed by the hematology medical team and the institution’s patient education committee. Prior to implementation, the form was piloted to obtain patient feedback on format and content. The PHR consists of 33 questions with 168 possible items/data points covering 12 domains: personal information (eg, contact information, SCD genotype), health provider information, personal health history (ie, health diagnoses), blood transfusion history, sickle cell pain events, hospitalization history in the previous year, diagnostic testing history (eg, laboratory tests), current medications, immunizations, advance directives, resource information (eg, disability benefits), and activities of daily living. Some questions required patients to check “Yes” or “No” (eg, “Have you been hospitalized in the past year? Have you received flu vaccine?”) while some required a written response (eg, “What medicines do you currently take?”).

Adolescents were instructed to complete the PHR independently without the help of their caregivers. After completing the form, the social worker reviewed the answers and/or asked participants’ perspectives about communicating health information to providers. A copy of the completed PHR was provided to the adolescent to promote continued education regarding medical history knowledge. The retrospective review of the PHR answers and participants’ characteristics was approved by the institutional review board with a waiver of consent from participants.

Statistical Methods

PHR answers were compared with each individual’s electronic medical record (EMR) for accuracy of responses. PHR responses were considered accurate only if they matched the information in the EMR. PHR items absent in the EMR were not coded (inability to verify the accuracy of responses) to capture the most accurate depiction of adolescents’ medical history knowledge. Coding was checked by at least 2 coders for response accuracy. Due to lack of EMR information for certain items, we could not verify the accuracy of many PHR items. Therefore, only items with at least 75% of data verified (across all patients who completed the PHR) were included in subsequent analyses.

Using SPSS (version 18), an agreement percentage was calculated for each patient across verifiable items and used as the primary outcome measure of knowledge accuracy. We used t tests to investigate gender or genotype differences in medical history accuracy. To examine genotype differences, we stratified the sample by SCD genotype: HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia and HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia [13].

Results

Patient Characteristics

Knowledge Accuracy Among Adolescents with SCD

Seventeen items in 6 PHR domains had the highest number of data points (at least 75% verified), and therefore were the only items that could be analyzed. Analyzed items included information about sickle cell genotype, eye doctor care, comorbid health issues (eg, asthma), allergies, hospitalizations, surgeries, transfusions, acute chest syndrome (ACS) episodes, eye problems, baseline hemoglobin level, and vaccination history as well as adolescents’ knowledge of current medications, including hydroxyurea, penicillin, and opioid pain medications.

Gender was not significantly associated with overall accuracy (P = 0.36). A significant difference was found in sickle genotype such that individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 8.23; SD = 1.70) were more accurate reporters of their medical history than those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype (mean number of items, 7.14; SD = 1.75; t(65) = –2.59, P = 0.01). Specifically, those with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype were significantly less accurate reporters of vaccination history (meningococcus t(60) = 3.55, P = 0.001; pneumococcus t(60) = 2.46, P = 0.02; hepatitis t(64) = 2.18, P = 0.03, eye problems t(62) = 3.62; P = 0.001, and surgical history t(62) = 2.14, P = 0.04).

Discussion

In the present study, we utilized the PHR to assess the accuracy of medical history knowledge of adolescents with SCD preparing to transition to adult care. Most adolescents were accurate reporters of important disease-relevant information (eg, genotype, transfusion history, hydroxyurea use), which may be a result of these topics being frequently discussed or recently encountered. For example, 97% of adolescents accurately reported penicillin use which may be related to our program’s emphasis on infection prevention education. However, disease knowledge of immunization history, prior ACS events, and opioid medication use might have been more difficult to recall due to the long interval from their occurrence until the completion of the PHR. Further, frequent changes in opioid medication use may have impacted the accuracy of adolescents’ answers with EMR data.

Individuals with HbSC/Sβ+ thalassemia genotype were more accurate reporters of their medical history, but the magnitude of difference was not large. These individuals tend to have fewer health issues and therefore less health information to recall, leading to higher accuracy. Furthermore, evidence demonstrates that individuals with HbSS/Sβ0 thalassemia genotype are at greater risk for cerebrovascular events and subsequent cognitive deficits [14], leading to more memory deficits and difficulty understanding and retaining health information [15]. The results suggest that patient health literacy, or an individual’s capacity to understand basic health information [16], may be a mediating factor in assessing for transition readiness. This is especially important given SCD risk for cognitive deficits [17].

Only 17 PHR items were analyzed due to conservative selection of items. Thus the present findings are not representative of the entire medical history. Additionally, the accuracy of medical history knowledge results may be limited by conservatism with abstracting information from the EMR (PHR information was considered accurate if it matched the information found in their EMR). Finally, we did not systematically assess the feasibility and utility of the PHR; ongoing participant feedback would aid in improving the PHR tool and implementation. It would be important to validate the PHR in a larger sample. However, our study is the first to our knowledge to systematically evaluate medical history knowledge among youth with SCD.

Conclusion and Practice Implications

The present study demonstrates that use of the PHR during regular health maintenance visits can help identify gaps in knowledge among adolescents with SCD who are approaching transfer to adult care. Sufficient knowledge of one’s medical history is an important aspect in transition preparation as it can facilitate the communication of medical information, thereby ensuring continuity of care [18,19]. The PHR could be used to teach medical history knowledge, assess a patient’s level of transition readiness at different time points, and identify areas for further targeted intervention. Knowledge tools, such as the PHR, can be investigated prospectively to assess the association of disease literacy and clinical outcomes, serving as a possible predictive instrument for transition health outcomes.

Corresponding author: Jerlym S. Porter, PhD, MPH, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, Dept. of Psychology, 262 Danny Thomas Pl., Mail Stop 740, Memphis, TN 38105, jerlym.porter@stjude.org.

Funding/support: This work was supported in part by HRSA grant 6 U1EMC19331-03-02 (PI: Hankins).

Financial disclosures: None.

Author contributions: conception and design, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; analysis and interpretation of data, MSZ, KMR, JSP; drafting of article, MSZ, JSP; critical revision of the article, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMW, JSH, JSP; provision of study materials or patients, MJ, AP; statistical expertise, KMR; obtaining of funding, JSH; collection and assembly of data, MSZ, MJ, AP, KMR, KMW.

1. Quinn CT. Sickle cell disease in childhood: from newborn screening through transition to adult medical care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013;60:1363–81.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:S512–21.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. de Montalembert M, Guitton C. Transition from paediatric to adult care for patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2014;164:630–5.

5. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

6. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

7. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood Jr C. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

8. Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 2002:287:1832–9.

9. Hait EJ, Barendse RM, Arnold JH, et al. Transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: a survey of adult gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:61–5.

10. Kennedy A, Sawyer S. Transition from pediatric to adult services: are we getting it right? Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20:403–9.

11. Sobota A, Akinlonu A, Champigny M, et al. Self-reported transition readiness among young adults with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:389–94.

12. Treadwell M, Johnson S, Sisler I, et al. Development of a sickle cell disease readiness for transition assessment. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2016;28:193–201.

13. Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, et al. Pain characteristics and age-related pain trajectories in infants and young children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:291–6.

14. Venkataraman A, Adams RJ. Neurologic complications of sickle cell disease. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;120:1015–25.

15. Porter JS, Matthews CS, Carroll YM, et al. Genetic education and sickle cell disease: feasibility and efficacy of a program tailored to adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:572–7.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. 2015. Accessed 26 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/index.html.

17. Armstrong FD, Thompson Jr RJ, Wang W, et al. Cognitive functioning and brain magnetic resonance imaging in children with sickle cell disease. Neuropsychology Committee of the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatrics 1996;97:864–70.

18. Kanter J, Kruse-Jarres R. Management of sickle cell disease from childhood through adulthood. Blood Rev 2013;27:279–87.

19. Treadwell M, Telfair J, Gibson RW, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: establishing evidence-based practice and directions for research. Am J Hematol 2011;86:116–2.

1. Quinn CT. Sickle cell disease in childhood: from newborn screening through transition to adult medical care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2013;60:1363–81.

2. Hassell KL. Population estimates of sickle cell disease in the U.S. Am J Prev Med 2010;38:S512–21.

3. Hamideh D, Alvarez O. Sickle cell disease related mortality in the United States (1999-2009). Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60:1482–6.

4. de Montalembert M, Guitton C. Transition from paediatric to adult care for patients with sickle cell disease. Br J Haematol 2014;164:630–5.

5. Quinn CT, Rogers ZR, McCavit TL, Buchanan GR. Improved survival of children and adolescents with sickle cell disease. Blood 2010;115:3447–52.

6. Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, et al. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA 2010;303:1288–94.

7. Lanzkron S, Carroll CP, Haywood Jr C. Mortality rates and age at death from sickle cell disease: U.S., 1979-2005. Public Health Rep 2013;128:110–6.

8. Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, et al. Childhood cancer survivors' knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA 2002:287:1832–9.

9. Hait EJ, Barendse RM, Arnold JH, et al. Transition of adolescents with inflammatory bowel disease from pediatric to adult care: a survey of adult gastroenterologists. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;48:61–5.

10. Kennedy A, Sawyer S. Transition from pediatric to adult services: are we getting it right? Curr Opin Pediatr 2008;20:403–9.

11. Sobota A, Akinlonu A, Champigny M, et al. Self-reported transition readiness among young adults with sickle cell disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:389–94.

12. Treadwell M, Johnson S, Sisler I, et al. Development of a sickle cell disease readiness for transition assessment. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2016;28:193–201.

13. Dampier C, Ely B, Brodecki D, et al. Pain characteristics and age-related pain trajectories in infants and young children with sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2014;61:291–6.

14. Venkataraman A, Adams RJ. Neurologic complications of sickle cell disease. Handb Clin Neurol 2014;120:1015–25.

15. Porter JS, Matthews CS, Carroll YM, et al. Genetic education and sickle cell disease: feasibility and efficacy of a program tailored to adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014;36:572–7.

16. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health literacy. 2015. Accessed 26 Oct 2015 at www.cdc.gov/healthliteracy/index.html.

17. Armstrong FD, Thompson Jr RJ, Wang W, et al. Cognitive functioning and brain magnetic resonance imaging in children with sickle cell disease. Neuropsychology Committee of the Cooperative Study of Sickle Cell Disease. Pediatrics 1996;97:864–70.

18. Kanter J, Kruse-Jarres R. Management of sickle cell disease from childhood through adulthood. Blood Rev 2013;27:279–87.

19. Treadwell M, Telfair J, Gibson RW, et al. Transition from pediatric to adult care in sickle cell disease: establishing evidence-based practice and directions for research. Am J Hematol 2011;86:116–2.