User login

Health Care Barriers and Quality of Life in Central Centrifugal Cicatricial Alopecia Patients

The etiology of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), a clinical and histological pattern of hair loss on the central scalp, has been well studied. This disease is chronic and progressive, with extensive follicular destruction and eventual burnout.1,2 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is most commonly seen in patients of African descent and has been shown to be 1 of the 5 most common dermatologic diagnoses in black patients.3,4 The top 5 dermatologic diagnoses within this population include acne vulgaris (28.4%), dyschromia (19.9%), eczema (9.1%), alopecia (8.3%), and seborrheic dermatitis (6.7%).4 The incidence rate of CCCA is estimated to be 5.6%.3,5 Most patients are women, with onset between the second and fourth decades of life.6

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia treatment efficacy is inversely correlated with disease duration. The primary goal of treatment is to prevent progression. Efforts are made to stimulate regrowth in areas that are not permanently scarred. When patients present with a substantial amount of scarring hair loss, dermatologists often are limited in their ability to achieve a cosmetically acceptable pattern of growth. Generally, hair is connected to a sense of self-worth in black women, and any type of hair loss has been shown to lead to frustration and decreased self-esteem.7 A 1994 study showed that 75% (44/58) of women with androgenetic alopecia had decreased self-esteem and 50% (29/58) had social challenges.8

The purpose of this pilot study was to determine the personal, historical, logistical, or environmental factors that preclude women from obtaining medical care for CCCA and to investigate how CCCA affects quality of life (QOL) and psychological well-being.

Methods

The investigators designed a survey study of adult, English-speaking, black women diagnosed with CCCA at the Northwestern University Department of Dermatology (Chicago, Illinois) between 2011 and 2017. Patients were selected from the electronic data warehouse compiled by the Department of Dermatology and were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: evaluated in the dermatology department between September 1, 2011, and September 30, 2017, by any faculty physician; diagnosed with CCCA; and aged 18 years or older. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English, as interpreters were not available. All patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria provided signed informed consent prior to participation. All surveys were disseminated in the office or via telephone from fall 2016 to spring 2017 and took 10 to 15 minutes to complete. The research was approved by the authors’ institutional review board (IRB ID STU00203449).

Survey Instrument

The

Data Analysis

Analyses were completed using data analysis software JMP Pro 13 from SAS and a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Continuous data were presented as mean, SD, median, minimum, and maximum. Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages. Nine QOL items were aggregated into a self-esteem category (questions 30–38).

Cronbach α, a statistical measure of internal consistency and how closely related items are in a group, was used to evaluate internal consistency reliability; values of 0.70 or greater indicate acceptable reliability.

Results

Of 501 individuals contacted, 34 completed the survey (7% completion rate). Nonrespondents included 7 who refused to participate and 460 who could not be contacted. All respondents self-identified as black women. Median age at time of survey administration was 46 years (range, 28–79 years); median age at CCCA diagnosis was 42 years (range, 15–73 years). Respondents did not significantly differ in age from nonrespondents (P=.46). The majority of respondents had an associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, or advanced degree of education (master of arts, doctor of medicine, doctor of jurisprudence, doctor of philosophy); however, 8 women reported completing some college, 1 reported completing high school, and 1 reported no schooling. Three respondents had no health insurance.

Initial Hair Loss Discovery

The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) were first to notice their hair loss, while 5 (15%) reported hairstylists as the initial observers. Twelve respondents (35%) initially went to a physician to learn why they were losing hair; 6 (18%) instead utilized hairstylists or the Internet. Fifteen women (44%) waited more than 1 month up to 6 months after noticing hair loss before seeing a physician instead of going immediately within a 4-week period, and 16 (47%) waited 1 year or more.

Nondermatologist Consultation

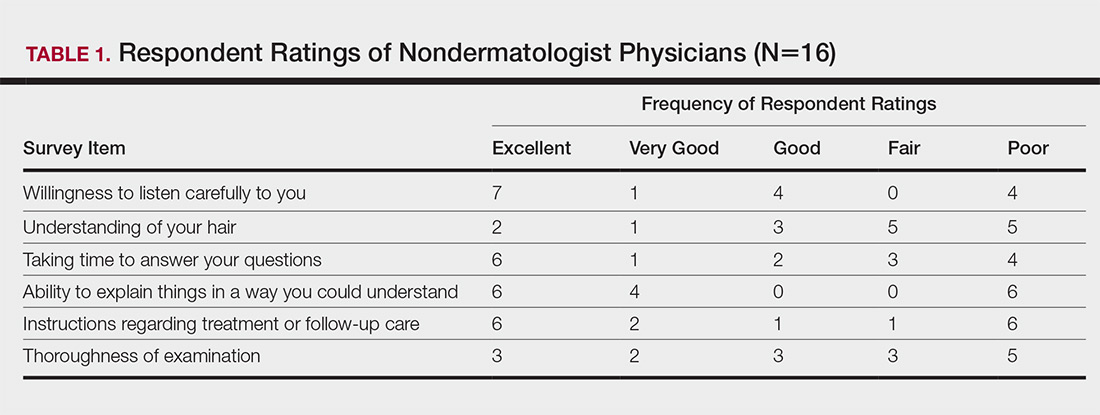

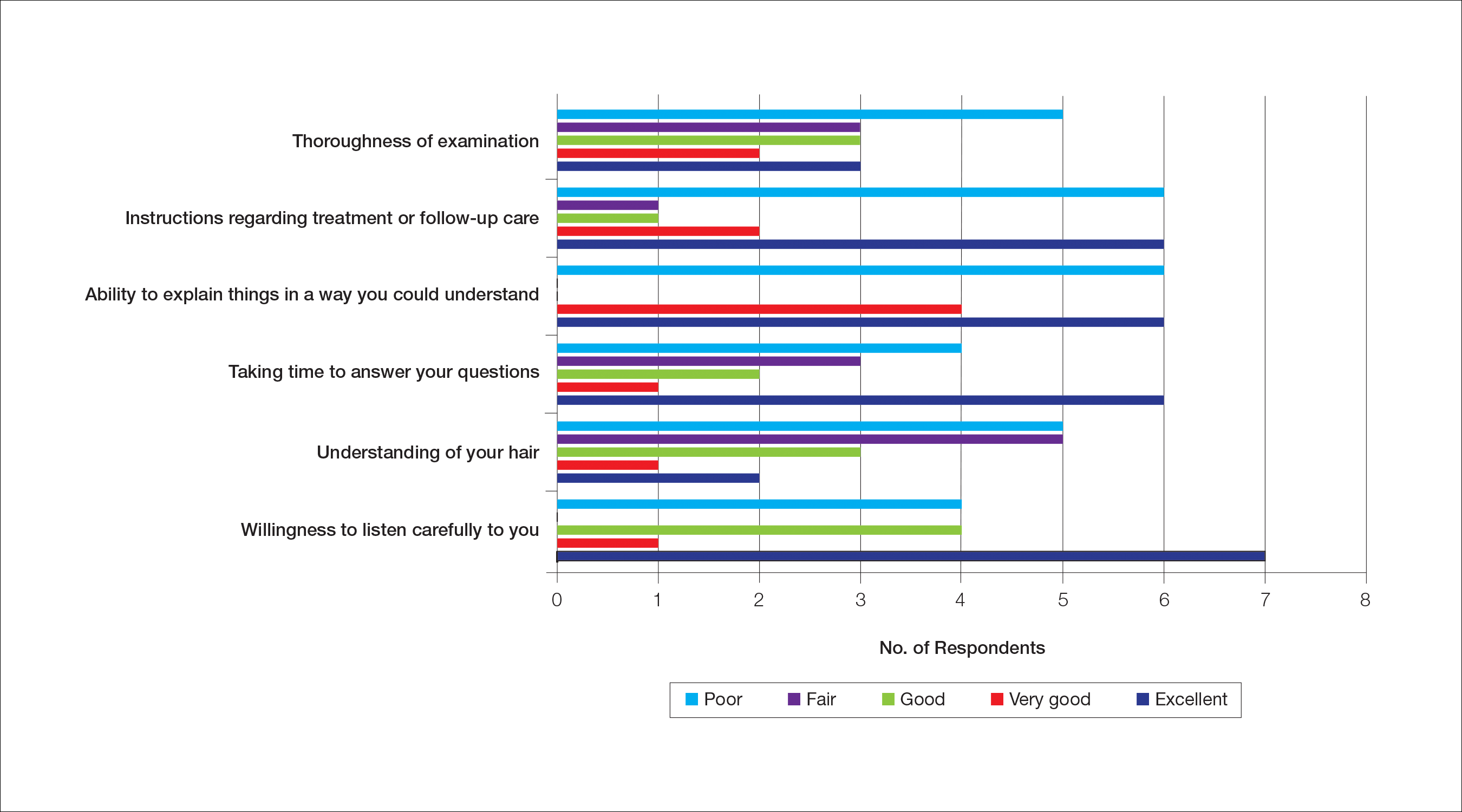

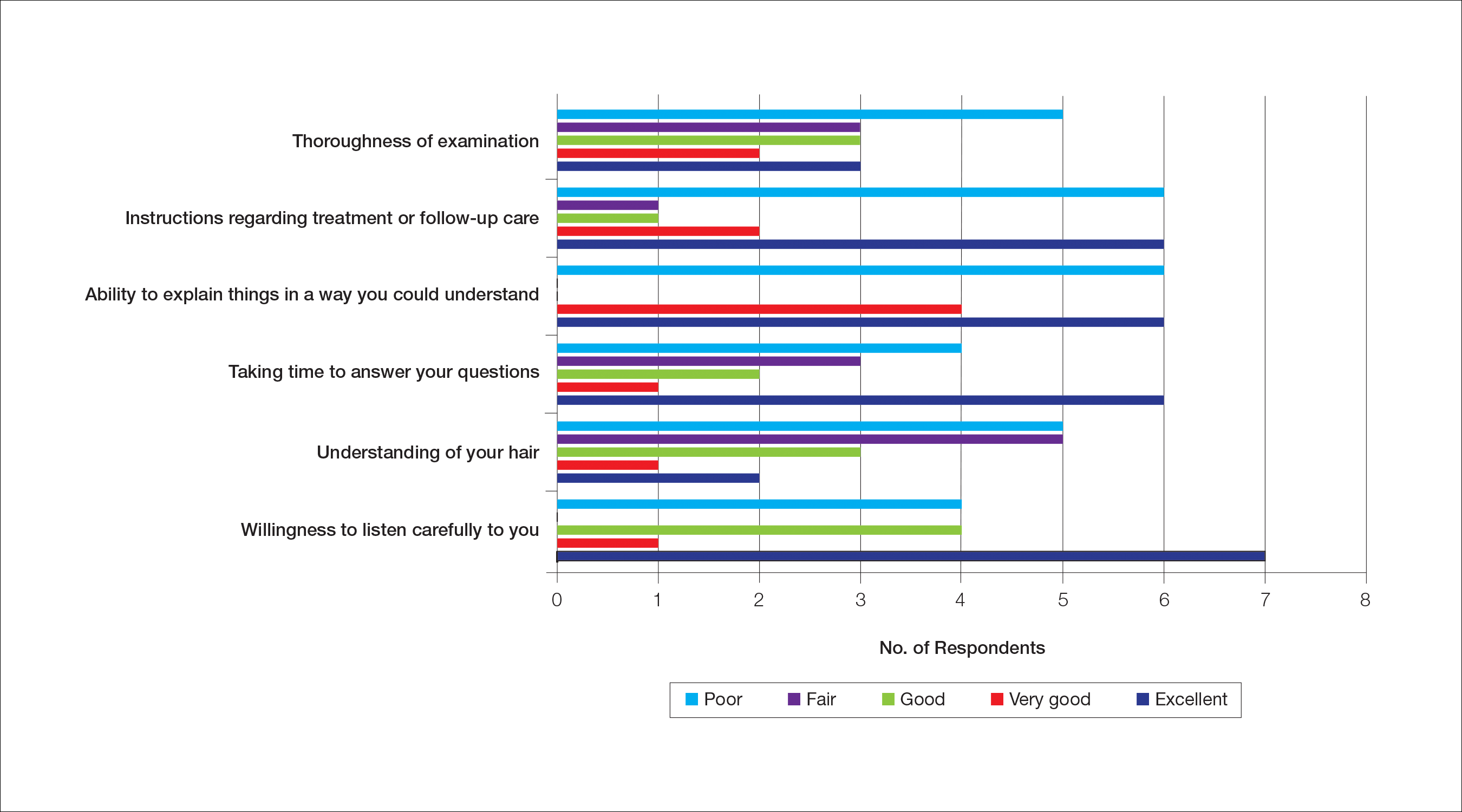

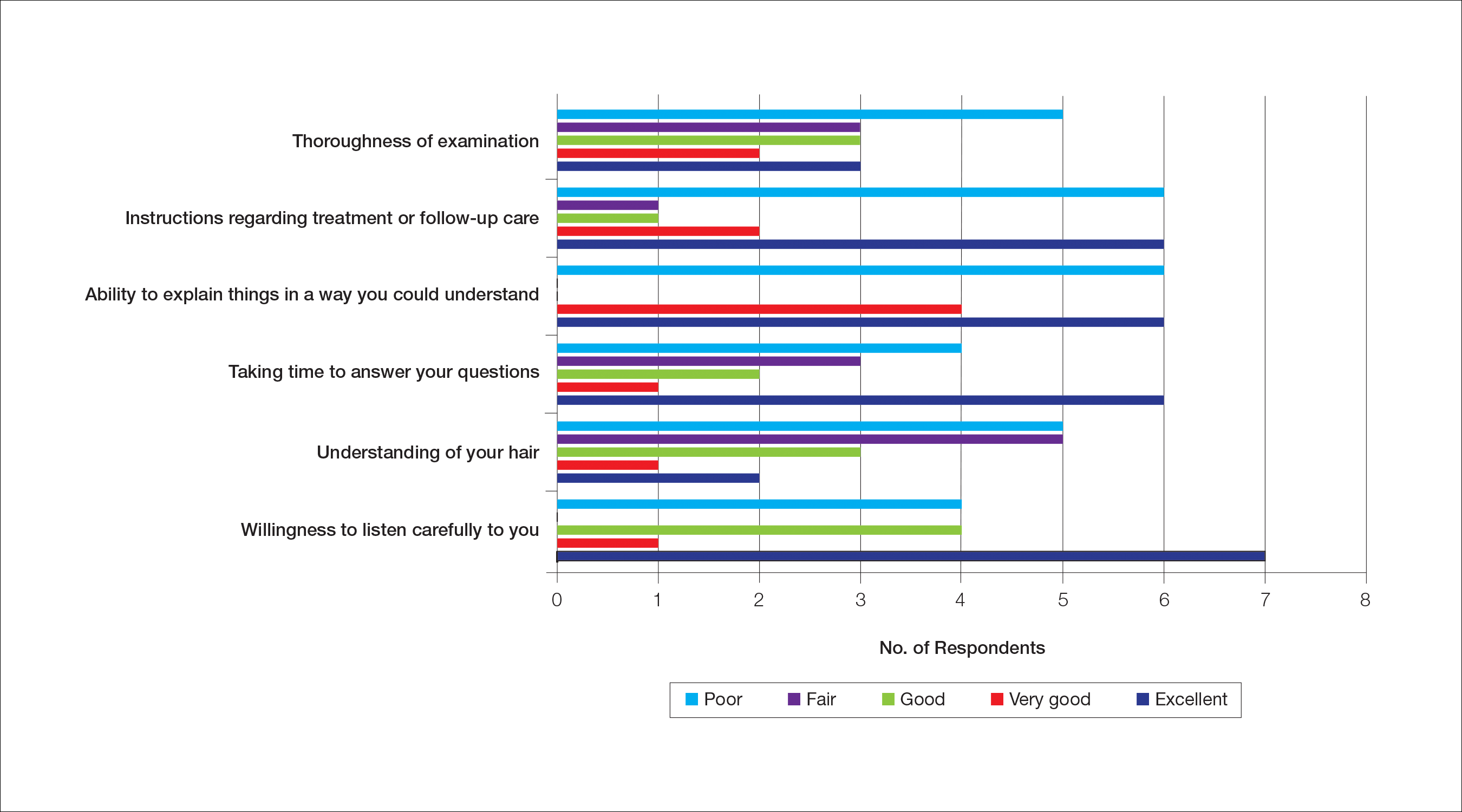

Almost half (16/34 [47%]) of the women went to a nondermatologist physician regarding their hair loss; of them, half (8/16 [50%]) reported their physician did not examine the scalp, 3 (19%) reported their physician offered a biopsy, and none of them reported that their physician diagnosed them with CCCA. The median patient rating of their nondermatologist physician interactions was good (3 on a 5-point scale). Table 1 and Figure 1 show responses to individual items.

Dermatologist Consultation

All 34 respondents presented to a dermatologist. The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) saw either 1 or 2 dermatologists for their hair loss. Three (9%) reported their dermatologist did not examine their scalp. Twelve respondents (35%) reported their dermatologist did not offer a biopsy. Twenty-one respondents (62%) reported a CCCA diagnosis from the first dermatologist they saw. Twenty-three respondents (68%) were diagnosed by dermatologists with expertise in hair disorders. Sixteen (47%) were diagnosed by dermatologists within a skin-of-color center. Fourteen (41%) initial dermatology consultations were race concordant.

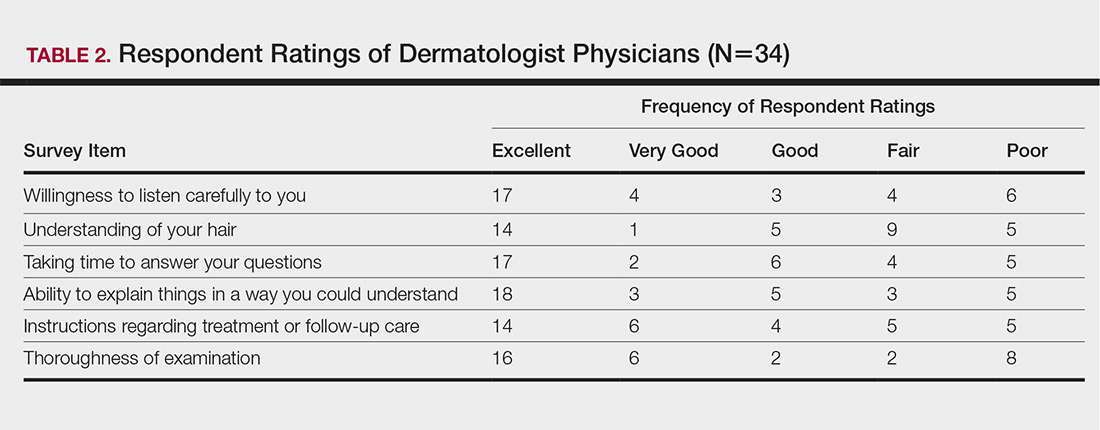

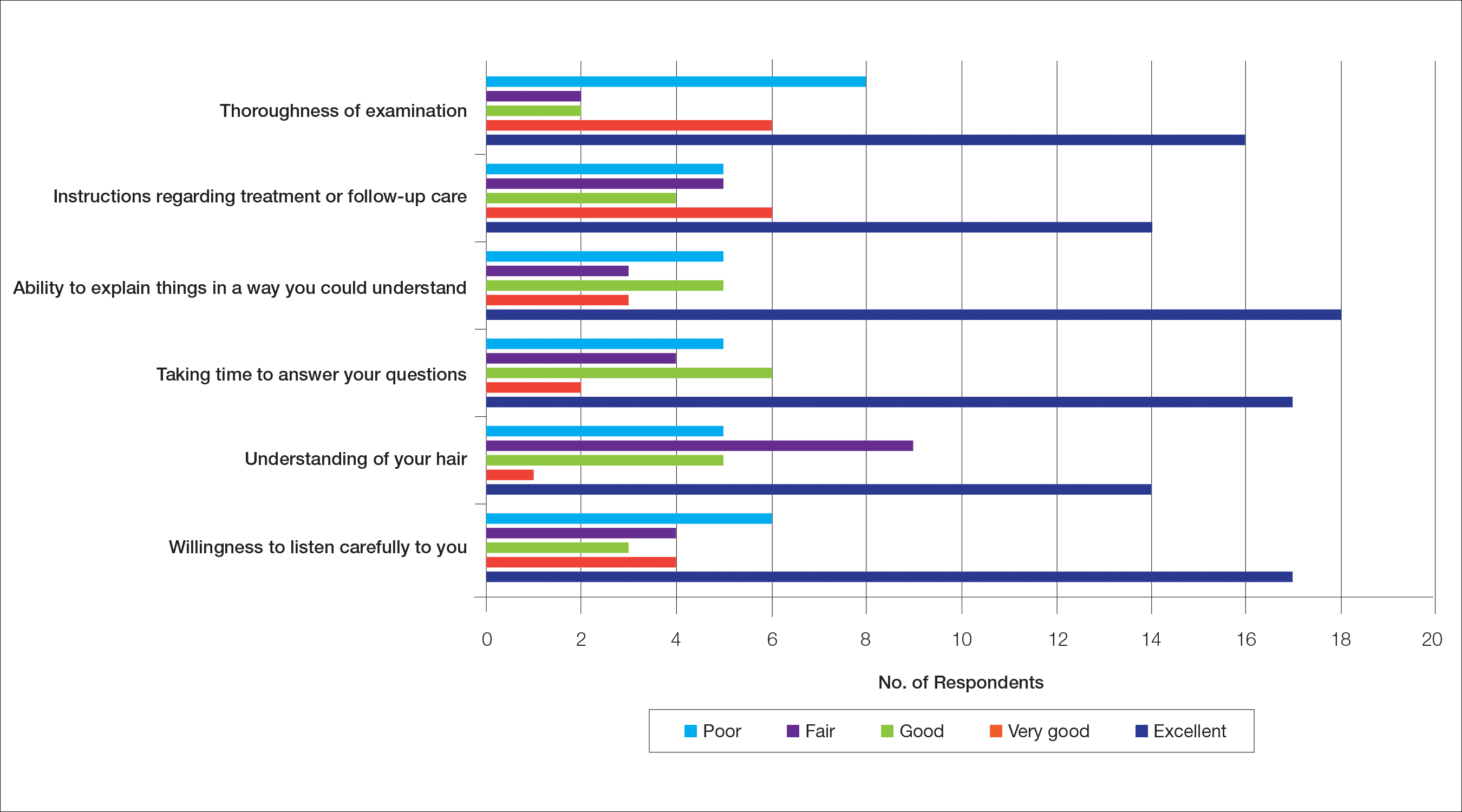

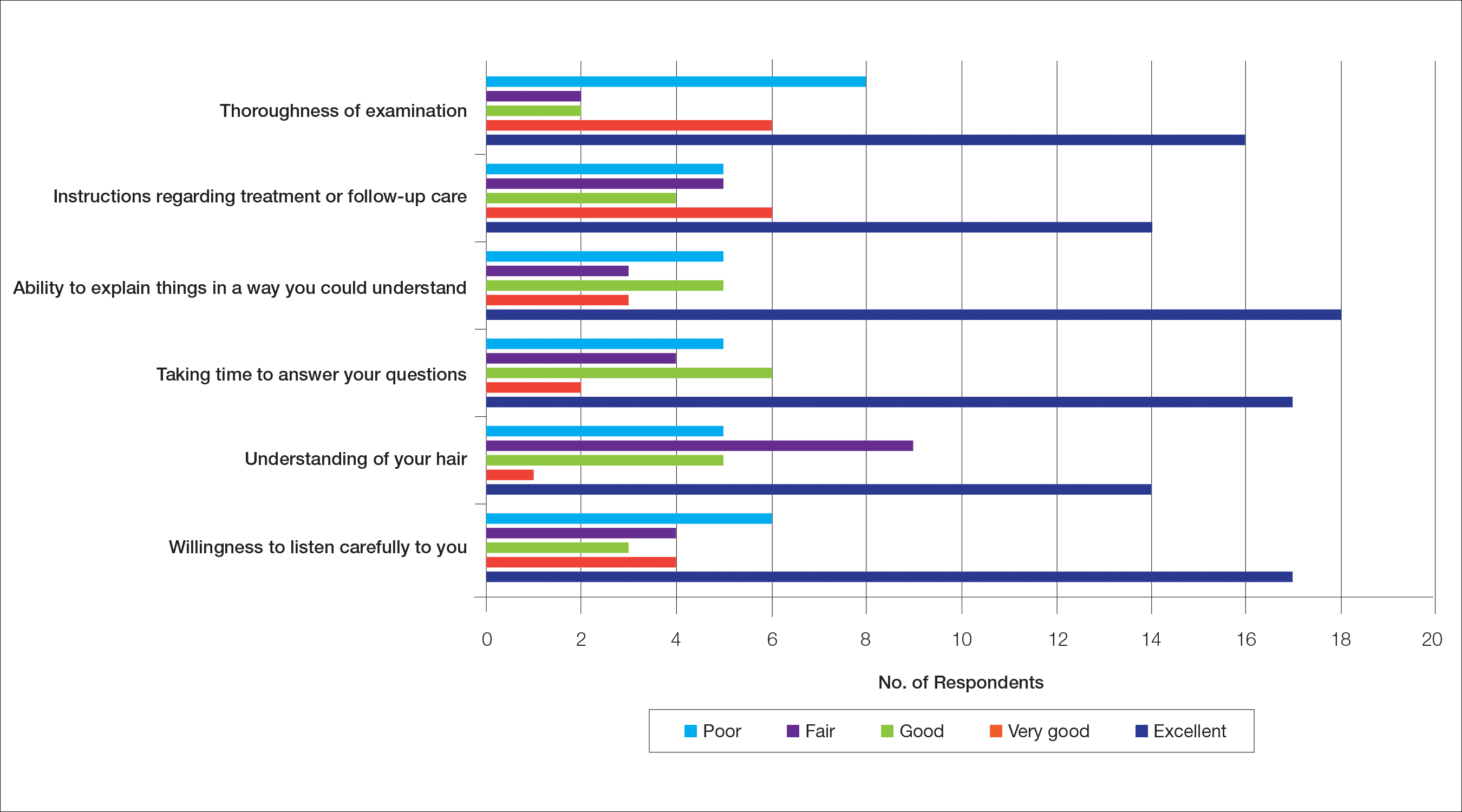

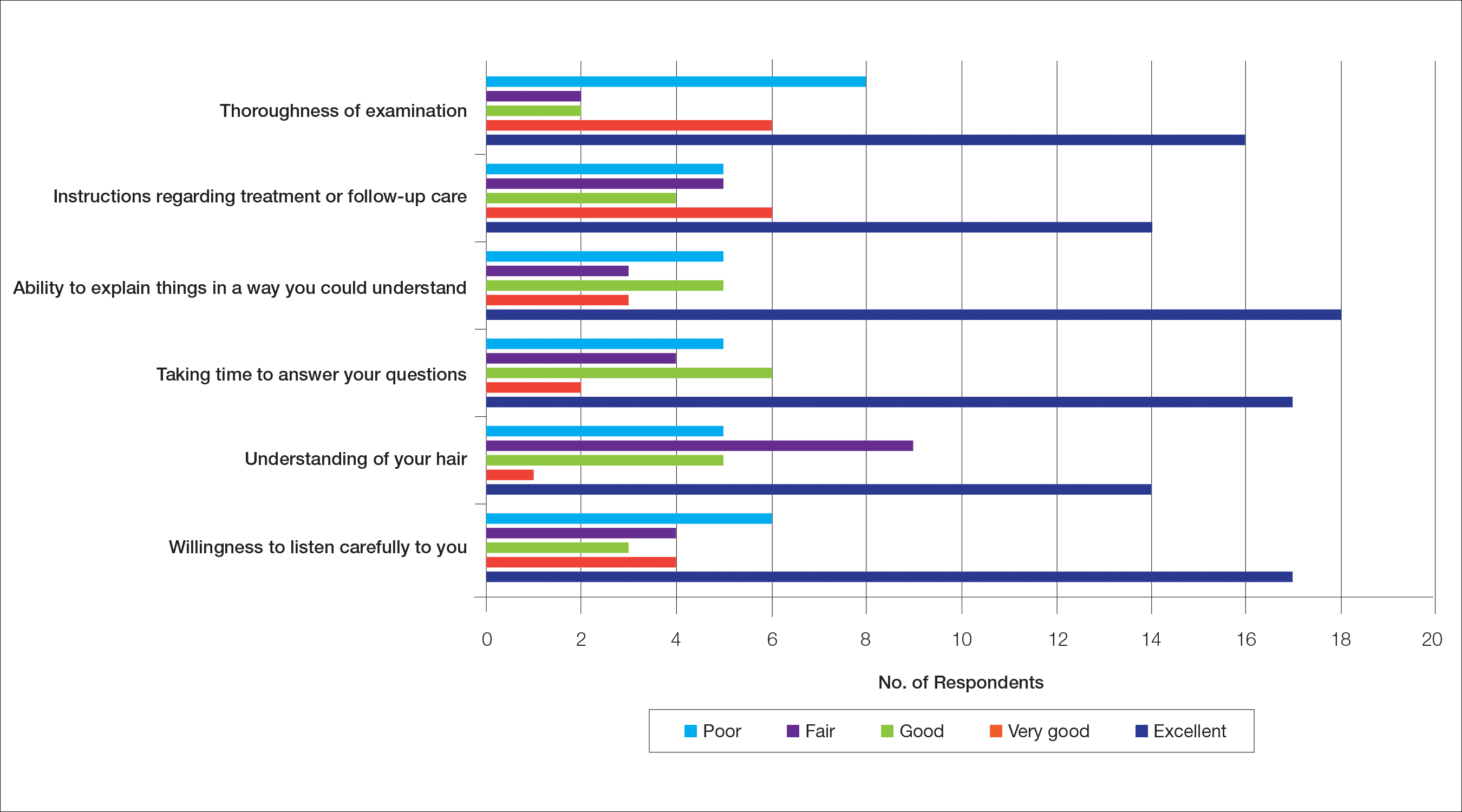

The median patient rating of their dermatologist interactions was excellent (5 on a 5-point scale). Table 2 and Figure 2 show responses to individual items. Respondents saw an average of 3 different providers, both dermatologists and otherwise.

Waiting to See a Dermatologist

Nearly all respondents (31/34 [91%]) recommended that other women with hair loss immediately go see a dermatologist.

Barriers to Care

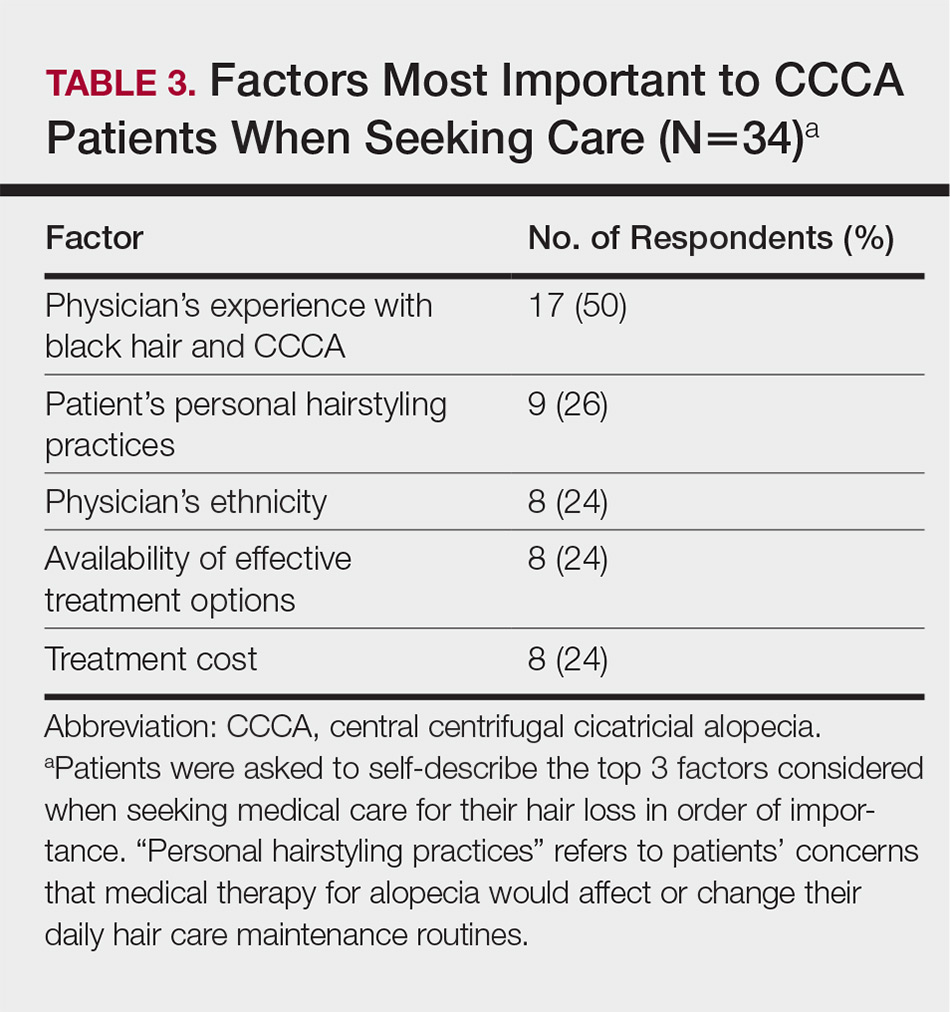

The top 5 factors reported as most important when initially seeking care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Table 3 shows frequency counts for these freely reported factors.

Quality of Life

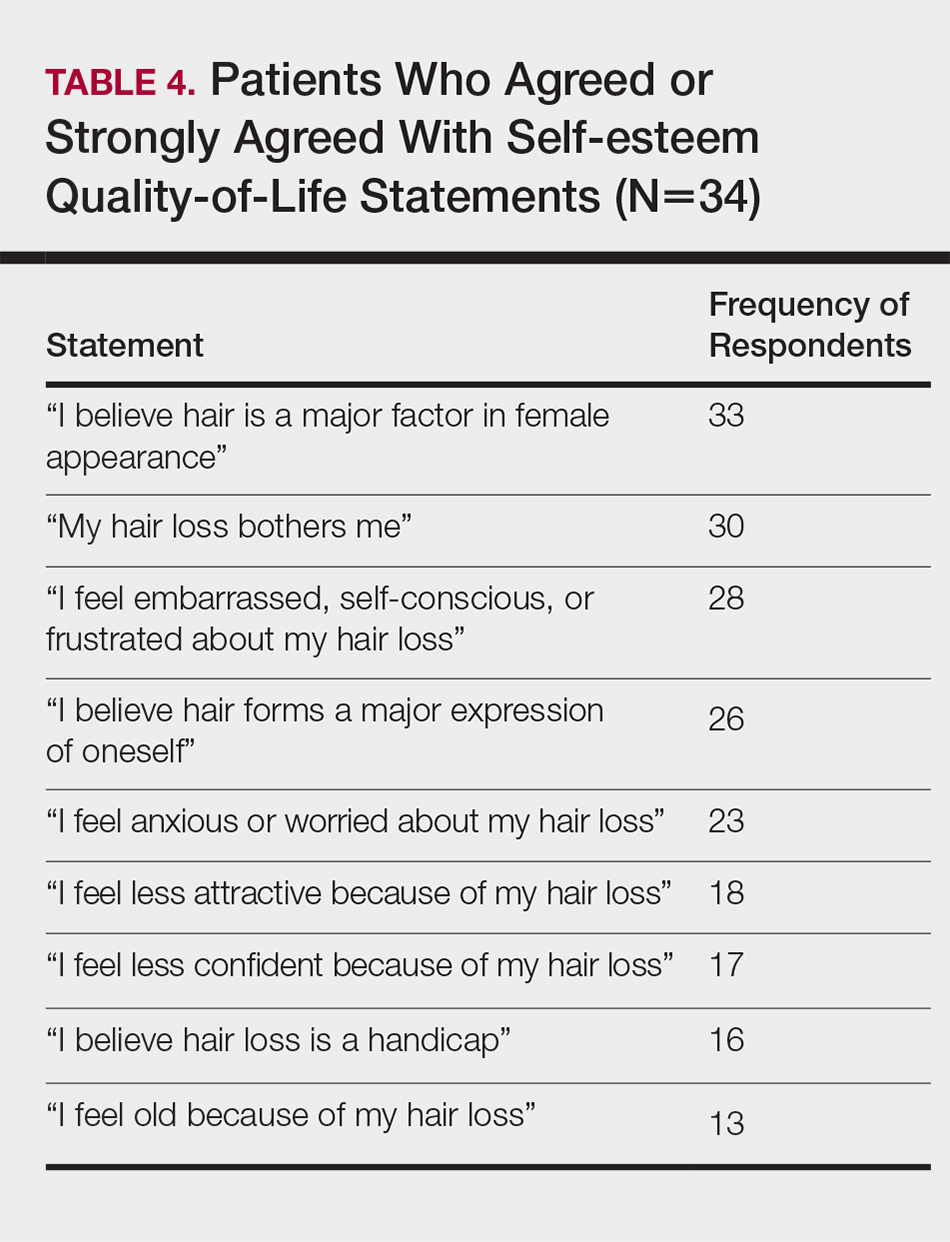

The median score on 9 aggregated self-esteem items was 4 on a 5-point scale, representing an agree response to statements such as “I feel embarrassed, self-conscious, or frustrated about my hair loss” (28/34 [82%]) and “My hair loss bothers me” (28/34 [82%])(Table 4). Cronbach α for self-esteem survey items was 0.7826.

For the nonaggregated items, many respondents strongly disagreed with statements pertaining to activities of daily living, including “I take care of where I sit or stand at social gatherings due to my hair loss” (18/34 [53%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to the grocery store” (29/34 [85%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to attend faith-based activities” (30/34 [88%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to exercise” (23/34 [68%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to work and/or school” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go out with a significant other” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to spend time with family” (27/34 [79%]), and “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to a hairstylist” (16/34 [47%]).

Comment

The majority of respondents were first to discover their hair loss. Harbingers of CCCA hair loss include paresthesia, tenderness, and itch,6 symptoms that are hard to ignore. Unfortunately, many patients notice hair thinning years after the scarring process has begun and a notable amount of hair has already been lost.6,9

Fifteen percent of respondents learned about their hair loss from their hairstylist. Women of African descent often maintain hairstyles that require frequent interactions with a hair care professional.7,10 As a result, hairstylists are at the forefront of early alopecia detection and are a valued resource in the black community. Open dialogue between dermatologists and hair care professionals could funnel women with hair loss into treatment before extensive damage.

Fifteen women (44%) recalled a waiting period of several months before seeking medical assistance, and 16 (47%) reported waiting 1 year or more. However, 91% of respondents indicated that women with hair loss should immediately see a physician for evaluation, thus patient experiences underscore the importance of early treatment. In our experience, many patients wait years before presenting to a physician. Some work with their hairstylists first to address the issue, while others do not realize how notable the loss has become. Some have a negative experience with one provider or are told there is nothing that can be done and then wait many years to see a second provider. Proper education of patients, physicians, and hairstylists is important in the identification and prompt treatment of this condition.

It is perhaps to be expected that patients rated interactions with dermatologists as excellent and very good more frequently than interactions with nondermatologists, which may be due to an absence of thorough hair evaluation with nondermatologists. Respondents reported that only half of nondermatologist providers actually examined their scalp during an initial encounter. However, both physician groups had the lowest frequencies of excellent and very good ratings on “understanding of your hair” (Tables 1 and 2). Patients with hair loss seek immediate answers, and often it is the specialist that can give them a firm diagnosis as opposed to a primary care provider. The fact that dermatologists and nondermatologists alike scored poorly on patient-perceived understanding of CCCA indicates an area for improvement within patient-physician interactions and physician knowledge.

The top 5 factors important to respondents when obtaining medical care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Patients with CCCA seeing dermatologists may discern a lack of experience with ethnic hair that leads patients to doubt their physicians’ ability to provide adequate care and decreased shared decision-making.11,12 These patient perceptions are not unfounded; a 2008 study showed that dermatology residents are not uniformly trained in diseases pertaining to patients with skin of color.13 Thus, incorporation of education on skin of color in dermatology training programs is critical.

Finally, hair loss patients often have concerns regarding how medical therapeutics could adversely affect personal hair care regimens, including washing and hairstyling practices. Current research demonstrates that patients consider treatment effectiveness and ability to be integrated into daily routines after establishing medical care.14 The present study shows that some CCCA patients contemplate how well a therapy will work before seeking medical care, demonstrating that patients continue to have these concerns after establishing medical care. Consideration of treatment effectiveness is important for both patients and providers, as there is minimal evidence behind current CCCA management practices. The ability for treatments to be easily integrated into daily hair care habits is important to maintain patient compliance.

Participants’ median self-esteem scores indicate the effect of CCCA on morale and self-perception. Items scrutinizing this construct had acceptable internal consistency reliability. It is interesting to note that activities of daily living were not impacted by hair loss. Examination of self-esteem is important in the alopecia population because the effect of hair loss on mental status is well documented.15-17 Low self-esteem has been reported as a prospective risk factor for clinical depression.18-20 In black patients, clinical depression rates surpass those of Hispanics and non-Hispanic white individuals.21 Dermatologists must consider the psychological status of all patients, particularly populations at risk for severe disease.

Limitations of this study include the small (34 participants) and mostly highly educated sample size, limited survey validity, and potential patient bias. Because many patients changed their address and/or telephone number in the time between CCCA diagnosis and the present study, we were left with a small pilot study, which minimizes the impact of our findings. Furthermore, our survey was created by a single expert’s opinion and modeling from preexisting alopecia questionnaires16; full validity procedures analyzing face, content, and criterion validity were not undertaken. Finally, the majority of respondents were patients of one of the study’s authors (S.S.L.P.), which could influence survey responses. The fact that some providers were hair experts and some were race concordant with their patients also could potentially affect the responses received, which was not analyzed in the present study. Future studies with more respondents from multiple providers would help clarify our preliminary findings.

Conclusion

Analysis of barriers to care and QOL in patients with skin of color is an essential addition to dermatologic discourse. Alopecia is particularly important to investigate, as prior research has found it to be one of the top 5 diagnoses made in patients with skin of color.3,4 Alopecia has been shown to negatively affect QOL.15,22,23 This study, although limited by small sample size, suggests CCCA also is a contributor to self-esteem challenges, similar to other forms of hair loss. Patient-physician interactions and personal hairstyling practices are prominent barriers to care for CCCA patients, demonstrating the need for quality education on skin of color and cultural competency in dermatology residencies across the country.

- Ogunleye TA, McMichael A, Olsen EA. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: what has been achieved, current clues for future research. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:173-181.

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342.

- Halder RM, Grimes PE, McLaurin CI, et al. Incidence of common dermatoses in a predominantly black dermatologic practice. Cutis. 1983;32:388, 390.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Olsen EA, Callender V, McMichael A, et al. Central hair loss in African American women: incidence and potential risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:245-252.

- Gathers RC, Lim HW. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:660-668.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African american women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Van Der Donk J, Hunfeld JA, Passchier J, et al. Quality of life and maladjustment associated with hair loss in women with alopecia androgenetica. Social Sci Med. 1994;38:159-163.

- Sperling LC, Sau P. The follicular degeneration syndrome in black patients. ‘hot comb alopecia’ revisited and revised. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:68-74.

- Gathers RC, Jankowski M, Eide M, et al. Hair grooming practices and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:574-578.

- Harvey VM, Ozoemena U, Paul J, et al. Patient-provider communication, concordance, and ratings of care in dermatology: results of a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22. pii: 13030/qt06j6p7gh.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Suchonwanit P, Hector CE, Bin Saif GA, et al. Factors affecting the severity of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E338-E343.

- Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. The effect of hair loss on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:137-139.

- Fabbrocini G, Panariello L, De Vita V, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a disease-specific questionnaire. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E276-E281.

- Ramos PM, Miot HA. Female pattern hair loss: a clinical and pathophysiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:529-543.

- Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:213-240.

- Steiger AE, Allemand M, Robins RW, et al. Low and decreasing self-esteem during adolescence predict adult depression two decades later. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:325-338.

- Wegener I, Geiser F, Alfter S, et al. Changes of explicitly and implicitly measured self-esteem in the treatment of major depression: evidence for implicit self-esteem compensation. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:57-67.

- Pratt LAB, Brody DJ. Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009-2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. NCHS Data Brief, No. 172. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db172.pdf. Published December 2014. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Schmidt S, Fischer TW, Chren MM, et al. Strategies of coping and quality of life in women with alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1038-1043.

- Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. Br Med J. 2005;331:951-953.

The etiology of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), a clinical and histological pattern of hair loss on the central scalp, has been well studied. This disease is chronic and progressive, with extensive follicular destruction and eventual burnout.1,2 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is most commonly seen in patients of African descent and has been shown to be 1 of the 5 most common dermatologic diagnoses in black patients.3,4 The top 5 dermatologic diagnoses within this population include acne vulgaris (28.4%), dyschromia (19.9%), eczema (9.1%), alopecia (8.3%), and seborrheic dermatitis (6.7%).4 The incidence rate of CCCA is estimated to be 5.6%.3,5 Most patients are women, with onset between the second and fourth decades of life.6

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia treatment efficacy is inversely correlated with disease duration. The primary goal of treatment is to prevent progression. Efforts are made to stimulate regrowth in areas that are not permanently scarred. When patients present with a substantial amount of scarring hair loss, dermatologists often are limited in their ability to achieve a cosmetically acceptable pattern of growth. Generally, hair is connected to a sense of self-worth in black women, and any type of hair loss has been shown to lead to frustration and decreased self-esteem.7 A 1994 study showed that 75% (44/58) of women with androgenetic alopecia had decreased self-esteem and 50% (29/58) had social challenges.8

The purpose of this pilot study was to determine the personal, historical, logistical, or environmental factors that preclude women from obtaining medical care for CCCA and to investigate how CCCA affects quality of life (QOL) and psychological well-being.

Methods

The investigators designed a survey study of adult, English-speaking, black women diagnosed with CCCA at the Northwestern University Department of Dermatology (Chicago, Illinois) between 2011 and 2017. Patients were selected from the electronic data warehouse compiled by the Department of Dermatology and were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: evaluated in the dermatology department between September 1, 2011, and September 30, 2017, by any faculty physician; diagnosed with CCCA; and aged 18 years or older. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English, as interpreters were not available. All patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria provided signed informed consent prior to participation. All surveys were disseminated in the office or via telephone from fall 2016 to spring 2017 and took 10 to 15 minutes to complete. The research was approved by the authors’ institutional review board (IRB ID STU00203449).

Survey Instrument

The

Data Analysis

Analyses were completed using data analysis software JMP Pro 13 from SAS and a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Continuous data were presented as mean, SD, median, minimum, and maximum. Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages. Nine QOL items were aggregated into a self-esteem category (questions 30–38).

Cronbach α, a statistical measure of internal consistency and how closely related items are in a group, was used to evaluate internal consistency reliability; values of 0.70 or greater indicate acceptable reliability.

Results

Of 501 individuals contacted, 34 completed the survey (7% completion rate). Nonrespondents included 7 who refused to participate and 460 who could not be contacted. All respondents self-identified as black women. Median age at time of survey administration was 46 years (range, 28–79 years); median age at CCCA diagnosis was 42 years (range, 15–73 years). Respondents did not significantly differ in age from nonrespondents (P=.46). The majority of respondents had an associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, or advanced degree of education (master of arts, doctor of medicine, doctor of jurisprudence, doctor of philosophy); however, 8 women reported completing some college, 1 reported completing high school, and 1 reported no schooling. Three respondents had no health insurance.

Initial Hair Loss Discovery

The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) were first to notice their hair loss, while 5 (15%) reported hairstylists as the initial observers. Twelve respondents (35%) initially went to a physician to learn why they were losing hair; 6 (18%) instead utilized hairstylists or the Internet. Fifteen women (44%) waited more than 1 month up to 6 months after noticing hair loss before seeing a physician instead of going immediately within a 4-week period, and 16 (47%) waited 1 year or more.

Nondermatologist Consultation

Almost half (16/34 [47%]) of the women went to a nondermatologist physician regarding their hair loss; of them, half (8/16 [50%]) reported their physician did not examine the scalp, 3 (19%) reported their physician offered a biopsy, and none of them reported that their physician diagnosed them with CCCA. The median patient rating of their nondermatologist physician interactions was good (3 on a 5-point scale). Table 1 and Figure 1 show responses to individual items.

Dermatologist Consultation

All 34 respondents presented to a dermatologist. The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) saw either 1 or 2 dermatologists for their hair loss. Three (9%) reported their dermatologist did not examine their scalp. Twelve respondents (35%) reported their dermatologist did not offer a biopsy. Twenty-one respondents (62%) reported a CCCA diagnosis from the first dermatologist they saw. Twenty-three respondents (68%) were diagnosed by dermatologists with expertise in hair disorders. Sixteen (47%) were diagnosed by dermatologists within a skin-of-color center. Fourteen (41%) initial dermatology consultations were race concordant.

The median patient rating of their dermatologist interactions was excellent (5 on a 5-point scale). Table 2 and Figure 2 show responses to individual items. Respondents saw an average of 3 different providers, both dermatologists and otherwise.

Waiting to See a Dermatologist

Nearly all respondents (31/34 [91%]) recommended that other women with hair loss immediately go see a dermatologist.

Barriers to Care

The top 5 factors reported as most important when initially seeking care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Table 3 shows frequency counts for these freely reported factors.

Quality of Life

The median score on 9 aggregated self-esteem items was 4 on a 5-point scale, representing an agree response to statements such as “I feel embarrassed, self-conscious, or frustrated about my hair loss” (28/34 [82%]) and “My hair loss bothers me” (28/34 [82%])(Table 4). Cronbach α for self-esteem survey items was 0.7826.

For the nonaggregated items, many respondents strongly disagreed with statements pertaining to activities of daily living, including “I take care of where I sit or stand at social gatherings due to my hair loss” (18/34 [53%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to the grocery store” (29/34 [85%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to attend faith-based activities” (30/34 [88%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to exercise” (23/34 [68%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to work and/or school” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go out with a significant other” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to spend time with family” (27/34 [79%]), and “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to a hairstylist” (16/34 [47%]).

Comment

The majority of respondents were first to discover their hair loss. Harbingers of CCCA hair loss include paresthesia, tenderness, and itch,6 symptoms that are hard to ignore. Unfortunately, many patients notice hair thinning years after the scarring process has begun and a notable amount of hair has already been lost.6,9

Fifteen percent of respondents learned about their hair loss from their hairstylist. Women of African descent often maintain hairstyles that require frequent interactions with a hair care professional.7,10 As a result, hairstylists are at the forefront of early alopecia detection and are a valued resource in the black community. Open dialogue between dermatologists and hair care professionals could funnel women with hair loss into treatment before extensive damage.

Fifteen women (44%) recalled a waiting period of several months before seeking medical assistance, and 16 (47%) reported waiting 1 year or more. However, 91% of respondents indicated that women with hair loss should immediately see a physician for evaluation, thus patient experiences underscore the importance of early treatment. In our experience, many patients wait years before presenting to a physician. Some work with their hairstylists first to address the issue, while others do not realize how notable the loss has become. Some have a negative experience with one provider or are told there is nothing that can be done and then wait many years to see a second provider. Proper education of patients, physicians, and hairstylists is important in the identification and prompt treatment of this condition.

It is perhaps to be expected that patients rated interactions with dermatologists as excellent and very good more frequently than interactions with nondermatologists, which may be due to an absence of thorough hair evaluation with nondermatologists. Respondents reported that only half of nondermatologist providers actually examined their scalp during an initial encounter. However, both physician groups had the lowest frequencies of excellent and very good ratings on “understanding of your hair” (Tables 1 and 2). Patients with hair loss seek immediate answers, and often it is the specialist that can give them a firm diagnosis as opposed to a primary care provider. The fact that dermatologists and nondermatologists alike scored poorly on patient-perceived understanding of CCCA indicates an area for improvement within patient-physician interactions and physician knowledge.

The top 5 factors important to respondents when obtaining medical care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Patients with CCCA seeing dermatologists may discern a lack of experience with ethnic hair that leads patients to doubt their physicians’ ability to provide adequate care and decreased shared decision-making.11,12 These patient perceptions are not unfounded; a 2008 study showed that dermatology residents are not uniformly trained in diseases pertaining to patients with skin of color.13 Thus, incorporation of education on skin of color in dermatology training programs is critical.

Finally, hair loss patients often have concerns regarding how medical therapeutics could adversely affect personal hair care regimens, including washing and hairstyling practices. Current research demonstrates that patients consider treatment effectiveness and ability to be integrated into daily routines after establishing medical care.14 The present study shows that some CCCA patients contemplate how well a therapy will work before seeking medical care, demonstrating that patients continue to have these concerns after establishing medical care. Consideration of treatment effectiveness is important for both patients and providers, as there is minimal evidence behind current CCCA management practices. The ability for treatments to be easily integrated into daily hair care habits is important to maintain patient compliance.

Participants’ median self-esteem scores indicate the effect of CCCA on morale and self-perception. Items scrutinizing this construct had acceptable internal consistency reliability. It is interesting to note that activities of daily living were not impacted by hair loss. Examination of self-esteem is important in the alopecia population because the effect of hair loss on mental status is well documented.15-17 Low self-esteem has been reported as a prospective risk factor for clinical depression.18-20 In black patients, clinical depression rates surpass those of Hispanics and non-Hispanic white individuals.21 Dermatologists must consider the psychological status of all patients, particularly populations at risk for severe disease.

Limitations of this study include the small (34 participants) and mostly highly educated sample size, limited survey validity, and potential patient bias. Because many patients changed their address and/or telephone number in the time between CCCA diagnosis and the present study, we were left with a small pilot study, which minimizes the impact of our findings. Furthermore, our survey was created by a single expert’s opinion and modeling from preexisting alopecia questionnaires16; full validity procedures analyzing face, content, and criterion validity were not undertaken. Finally, the majority of respondents were patients of one of the study’s authors (S.S.L.P.), which could influence survey responses. The fact that some providers were hair experts and some were race concordant with their patients also could potentially affect the responses received, which was not analyzed in the present study. Future studies with more respondents from multiple providers would help clarify our preliminary findings.

Conclusion

Analysis of barriers to care and QOL in patients with skin of color is an essential addition to dermatologic discourse. Alopecia is particularly important to investigate, as prior research has found it to be one of the top 5 diagnoses made in patients with skin of color.3,4 Alopecia has been shown to negatively affect QOL.15,22,23 This study, although limited by small sample size, suggests CCCA also is a contributor to self-esteem challenges, similar to other forms of hair loss. Patient-physician interactions and personal hairstyling practices are prominent barriers to care for CCCA patients, demonstrating the need for quality education on skin of color and cultural competency in dermatology residencies across the country.

The etiology of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA), a clinical and histological pattern of hair loss on the central scalp, has been well studied. This disease is chronic and progressive, with extensive follicular destruction and eventual burnout.1,2 Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia is most commonly seen in patients of African descent and has been shown to be 1 of the 5 most common dermatologic diagnoses in black patients.3,4 The top 5 dermatologic diagnoses within this population include acne vulgaris (28.4%), dyschromia (19.9%), eczema (9.1%), alopecia (8.3%), and seborrheic dermatitis (6.7%).4 The incidence rate of CCCA is estimated to be 5.6%.3,5 Most patients are women, with onset between the second and fourth decades of life.6

Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia treatment efficacy is inversely correlated with disease duration. The primary goal of treatment is to prevent progression. Efforts are made to stimulate regrowth in areas that are not permanently scarred. When patients present with a substantial amount of scarring hair loss, dermatologists often are limited in their ability to achieve a cosmetically acceptable pattern of growth. Generally, hair is connected to a sense of self-worth in black women, and any type of hair loss has been shown to lead to frustration and decreased self-esteem.7 A 1994 study showed that 75% (44/58) of women with androgenetic alopecia had decreased self-esteem and 50% (29/58) had social challenges.8

The purpose of this pilot study was to determine the personal, historical, logistical, or environmental factors that preclude women from obtaining medical care for CCCA and to investigate how CCCA affects quality of life (QOL) and psychological well-being.

Methods

The investigators designed a survey study of adult, English-speaking, black women diagnosed with CCCA at the Northwestern University Department of Dermatology (Chicago, Illinois) between 2011 and 2017. Patients were selected from the electronic data warehouse compiled by the Department of Dermatology and were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: evaluated in the dermatology department between September 1, 2011, and September 30, 2017, by any faculty physician; diagnosed with CCCA; and aged 18 years or older. Patients were excluded if they did not speak English, as interpreters were not available. All patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria provided signed informed consent prior to participation. All surveys were disseminated in the office or via telephone from fall 2016 to spring 2017 and took 10 to 15 minutes to complete. The research was approved by the authors’ institutional review board (IRB ID STU00203449).

Survey Instrument

The

Data Analysis

Analyses were completed using data analysis software JMP Pro 13 from SAS and a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet. Continuous data were presented as mean, SD, median, minimum, and maximum. Categorical data were presented as counts and percentages. Nine QOL items were aggregated into a self-esteem category (questions 30–38).

Cronbach α, a statistical measure of internal consistency and how closely related items are in a group, was used to evaluate internal consistency reliability; values of 0.70 or greater indicate acceptable reliability.

Results

Of 501 individuals contacted, 34 completed the survey (7% completion rate). Nonrespondents included 7 who refused to participate and 460 who could not be contacted. All respondents self-identified as black women. Median age at time of survey administration was 46 years (range, 28–79 years); median age at CCCA diagnosis was 42 years (range, 15–73 years). Respondents did not significantly differ in age from nonrespondents (P=.46). The majority of respondents had an associate’s degree, bachelor’s degree, or advanced degree of education (master of arts, doctor of medicine, doctor of jurisprudence, doctor of philosophy); however, 8 women reported completing some college, 1 reported completing high school, and 1 reported no schooling. Three respondents had no health insurance.

Initial Hair Loss Discovery

The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) were first to notice their hair loss, while 5 (15%) reported hairstylists as the initial observers. Twelve respondents (35%) initially went to a physician to learn why they were losing hair; 6 (18%) instead utilized hairstylists or the Internet. Fifteen women (44%) waited more than 1 month up to 6 months after noticing hair loss before seeing a physician instead of going immediately within a 4-week period, and 16 (47%) waited 1 year or more.

Nondermatologist Consultation

Almost half (16/34 [47%]) of the women went to a nondermatologist physician regarding their hair loss; of them, half (8/16 [50%]) reported their physician did not examine the scalp, 3 (19%) reported their physician offered a biopsy, and none of them reported that their physician diagnosed them with CCCA. The median patient rating of their nondermatologist physician interactions was good (3 on a 5-point scale). Table 1 and Figure 1 show responses to individual items.

Dermatologist Consultation

All 34 respondents presented to a dermatologist. The majority of respondents (22/34 [65%]) saw either 1 or 2 dermatologists for their hair loss. Three (9%) reported their dermatologist did not examine their scalp. Twelve respondents (35%) reported their dermatologist did not offer a biopsy. Twenty-one respondents (62%) reported a CCCA diagnosis from the first dermatologist they saw. Twenty-three respondents (68%) were diagnosed by dermatologists with expertise in hair disorders. Sixteen (47%) were diagnosed by dermatologists within a skin-of-color center. Fourteen (41%) initial dermatology consultations were race concordant.

The median patient rating of their dermatologist interactions was excellent (5 on a 5-point scale). Table 2 and Figure 2 show responses to individual items. Respondents saw an average of 3 different providers, both dermatologists and otherwise.

Waiting to See a Dermatologist

Nearly all respondents (31/34 [91%]) recommended that other women with hair loss immediately go see a dermatologist.

Barriers to Care

The top 5 factors reported as most important when initially seeking care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Table 3 shows frequency counts for these freely reported factors.

Quality of Life

The median score on 9 aggregated self-esteem items was 4 on a 5-point scale, representing an agree response to statements such as “I feel embarrassed, self-conscious, or frustrated about my hair loss” (28/34 [82%]) and “My hair loss bothers me” (28/34 [82%])(Table 4). Cronbach α for self-esteem survey items was 0.7826.

For the nonaggregated items, many respondents strongly disagreed with statements pertaining to activities of daily living, including “I take care of where I sit or stand at social gatherings due to my hair loss” (18/34 [53%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to the grocery store” (29/34 [85%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to attend faith-based activities” (30/34 [88%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to exercise” (23/34 [68%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to work and/or school” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go out with a significant other” (24/34 [71%]), “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to spend time with family” (27/34 [79%]), and “My hair loss makes it difficult for me to go to a hairstylist” (16/34 [47%]).

Comment

The majority of respondents were first to discover their hair loss. Harbingers of CCCA hair loss include paresthesia, tenderness, and itch,6 symptoms that are hard to ignore. Unfortunately, many patients notice hair thinning years after the scarring process has begun and a notable amount of hair has already been lost.6,9

Fifteen percent of respondents learned about their hair loss from their hairstylist. Women of African descent often maintain hairstyles that require frequent interactions with a hair care professional.7,10 As a result, hairstylists are at the forefront of early alopecia detection and are a valued resource in the black community. Open dialogue between dermatologists and hair care professionals could funnel women with hair loss into treatment before extensive damage.

Fifteen women (44%) recalled a waiting period of several months before seeking medical assistance, and 16 (47%) reported waiting 1 year or more. However, 91% of respondents indicated that women with hair loss should immediately see a physician for evaluation, thus patient experiences underscore the importance of early treatment. In our experience, many patients wait years before presenting to a physician. Some work with their hairstylists first to address the issue, while others do not realize how notable the loss has become. Some have a negative experience with one provider or are told there is nothing that can be done and then wait many years to see a second provider. Proper education of patients, physicians, and hairstylists is important in the identification and prompt treatment of this condition.

It is perhaps to be expected that patients rated interactions with dermatologists as excellent and very good more frequently than interactions with nondermatologists, which may be due to an absence of thorough hair evaluation with nondermatologists. Respondents reported that only half of nondermatologist providers actually examined their scalp during an initial encounter. However, both physician groups had the lowest frequencies of excellent and very good ratings on “understanding of your hair” (Tables 1 and 2). Patients with hair loss seek immediate answers, and often it is the specialist that can give them a firm diagnosis as opposed to a primary care provider. The fact that dermatologists and nondermatologists alike scored poorly on patient-perceived understanding of CCCA indicates an area for improvement within patient-physician interactions and physician knowledge.

The top 5 factors important to respondents when obtaining medical care included the physician’s experience with black hair and CCCA, the patient’s personal hairstyling practices, the physician’s ethnicity, availability of effective treatment options, and treatment cost. Patients with CCCA seeing dermatologists may discern a lack of experience with ethnic hair that leads patients to doubt their physicians’ ability to provide adequate care and decreased shared decision-making.11,12 These patient perceptions are not unfounded; a 2008 study showed that dermatology residents are not uniformly trained in diseases pertaining to patients with skin of color.13 Thus, incorporation of education on skin of color in dermatology training programs is critical.

Finally, hair loss patients often have concerns regarding how medical therapeutics could adversely affect personal hair care regimens, including washing and hairstyling practices. Current research demonstrates that patients consider treatment effectiveness and ability to be integrated into daily routines after establishing medical care.14 The present study shows that some CCCA patients contemplate how well a therapy will work before seeking medical care, demonstrating that patients continue to have these concerns after establishing medical care. Consideration of treatment effectiveness is important for both patients and providers, as there is minimal evidence behind current CCCA management practices. The ability for treatments to be easily integrated into daily hair care habits is important to maintain patient compliance.

Participants’ median self-esteem scores indicate the effect of CCCA on morale and self-perception. Items scrutinizing this construct had acceptable internal consistency reliability. It is interesting to note that activities of daily living were not impacted by hair loss. Examination of self-esteem is important in the alopecia population because the effect of hair loss on mental status is well documented.15-17 Low self-esteem has been reported as a prospective risk factor for clinical depression.18-20 In black patients, clinical depression rates surpass those of Hispanics and non-Hispanic white individuals.21 Dermatologists must consider the psychological status of all patients, particularly populations at risk for severe disease.

Limitations of this study include the small (34 participants) and mostly highly educated sample size, limited survey validity, and potential patient bias. Because many patients changed their address and/or telephone number in the time between CCCA diagnosis and the present study, we were left with a small pilot study, which minimizes the impact of our findings. Furthermore, our survey was created by a single expert’s opinion and modeling from preexisting alopecia questionnaires16; full validity procedures analyzing face, content, and criterion validity were not undertaken. Finally, the majority of respondents were patients of one of the study’s authors (S.S.L.P.), which could influence survey responses. The fact that some providers were hair experts and some were race concordant with their patients also could potentially affect the responses received, which was not analyzed in the present study. Future studies with more respondents from multiple providers would help clarify our preliminary findings.

Conclusion

Analysis of barriers to care and QOL in patients with skin of color is an essential addition to dermatologic discourse. Alopecia is particularly important to investigate, as prior research has found it to be one of the top 5 diagnoses made in patients with skin of color.3,4 Alopecia has been shown to negatively affect QOL.15,22,23 This study, although limited by small sample size, suggests CCCA also is a contributor to self-esteem challenges, similar to other forms of hair loss. Patient-physician interactions and personal hairstyling practices are prominent barriers to care for CCCA patients, demonstrating the need for quality education on skin of color and cultural competency in dermatology residencies across the country.

- Ogunleye TA, McMichael A, Olsen EA. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: what has been achieved, current clues for future research. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:173-181.

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342.

- Halder RM, Grimes PE, McLaurin CI, et al. Incidence of common dermatoses in a predominantly black dermatologic practice. Cutis. 1983;32:388, 390.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Olsen EA, Callender V, McMichael A, et al. Central hair loss in African American women: incidence and potential risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:245-252.

- Gathers RC, Lim HW. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:660-668.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African american women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Van Der Donk J, Hunfeld JA, Passchier J, et al. Quality of life and maladjustment associated with hair loss in women with alopecia androgenetica. Social Sci Med. 1994;38:159-163.

- Sperling LC, Sau P. The follicular degeneration syndrome in black patients. ‘hot comb alopecia’ revisited and revised. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:68-74.

- Gathers RC, Jankowski M, Eide M, et al. Hair grooming practices and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:574-578.

- Harvey VM, Ozoemena U, Paul J, et al. Patient-provider communication, concordance, and ratings of care in dermatology: results of a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22. pii: 13030/qt06j6p7gh.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Suchonwanit P, Hector CE, Bin Saif GA, et al. Factors affecting the severity of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E338-E343.

- Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. The effect of hair loss on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:137-139.

- Fabbrocini G, Panariello L, De Vita V, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a disease-specific questionnaire. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E276-E281.

- Ramos PM, Miot HA. Female pattern hair loss: a clinical and pathophysiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:529-543.

- Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:213-240.

- Steiger AE, Allemand M, Robins RW, et al. Low and decreasing self-esteem during adolescence predict adult depression two decades later. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:325-338.

- Wegener I, Geiser F, Alfter S, et al. Changes of explicitly and implicitly measured self-esteem in the treatment of major depression: evidence for implicit self-esteem compensation. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:57-67.

- Pratt LAB, Brody DJ. Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009-2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. NCHS Data Brief, No. 172. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db172.pdf. Published December 2014. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Schmidt S, Fischer TW, Chren MM, et al. Strategies of coping and quality of life in women with alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1038-1043.

- Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. Br Med J. 2005;331:951-953.

- Ogunleye TA, McMichael A, Olsen EA. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: what has been achieved, current clues for future research. Dermatol Clin. 2014;32:173-181.

- Sperling LC. Scarring alopecia and the dermatopathologist. J Cutan Pathol. 2001;28:333-342.

- Halder RM, Grimes PE, McLaurin CI, et al. Incidence of common dermatoses in a predominantly black dermatologic practice. Cutis. 1983;32:388, 390.

- Alexis AF, Sergay AB, Taylor SC. Common dermatologic disorders in skin of color: a comparative practice survey. Cutis. 2007;80:387-394.

- Olsen EA, Callender V, McMichael A, et al. Central hair loss in African American women: incidence and potential risk factors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:245-252.

- Gathers RC, Lim HW. Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia: past, present, and future. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:660-668.

- Gathers RC, Mahan MG. African american women, hair care, and health barriers. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2014;7:26-29.

- Van Der Donk J, Hunfeld JA, Passchier J, et al. Quality of life and maladjustment associated with hair loss in women with alopecia androgenetica. Social Sci Med. 1994;38:159-163.

- Sperling LC, Sau P. The follicular degeneration syndrome in black patients. ‘hot comb alopecia’ revisited and revised. Arch Dermatol. 1992;128:68-74.

- Gathers RC, Jankowski M, Eide M, et al. Hair grooming practices and central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:574-578.

- Harvey VM, Ozoemena U, Paul J, et al. Patient-provider communication, concordance, and ratings of care in dermatology: results of a cross-sectional study. Dermatol Online J. 2016;22. pii: 13030/qt06j6p7gh.

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43:296-306.

- Nijhawan RI, Jacob SE, Woolery-Lloyd H. Skin of color education in dermatology residency programs: does residency training reflect the changing demographics of the United States? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;59:615-618.

- Suchonwanit P, Hector CE, Bin Saif GA, et al. Factors affecting the severity of central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:E338-E343.

- Williamson D, Gonzalez M, Finlay AY. The effect of hair loss on quality of life. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001;15:137-139.

- Fabbrocini G, Panariello L, De Vita V, et al. Quality of life in alopecia areata: a disease-specific questionnaire. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E276-E281.

- Ramos PM, Miot HA. Female pattern hair loss: a clinical and pathophysiological review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:529-543.

- Sowislo JF, Orth U. Does low self-esteem predict depression and anxiety? a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull. 2013;139:213-240.

- Steiger AE, Allemand M, Robins RW, et al. Low and decreasing self-esteem during adolescence predict adult depression two decades later. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106:325-338.

- Wegener I, Geiser F, Alfter S, et al. Changes of explicitly and implicitly measured self-esteem in the treatment of major depression: evidence for implicit self-esteem compensation. Compr Psychiatry. 2015;58:57-67.

- Pratt LAB, Brody DJ. Depression in the U.S. Household Population, 2009-2012. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2014. NCHS Data Brief, No. 172. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db172.pdf. Published December 2014. Accessed November 19, 2018.

- Schmidt S, Fischer TW, Chren MM, et al. Strategies of coping and quality of life in women with alopecia. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:1038-1043.

- Hunt N, McHale S. The psychological impact of alopecia. Br Med J. 2005;331:951-953.

Practice Points

- Central centrifugal cicatricial alopecia (CCCA) presents a unique set of challenges for both patients and providers.

- Lack of physician experience with black hair/CCCA and the potential impact of care on personal hairstyling practices are 2 barriers to care for many patients with this disease.

- There is a need for improved patient-provider communication strategies, quality education on hair in skin of color patients, and cultural competency training in dermatology residencies across the country.