User login

Contraceptive care best practices

While the unintended pregnancy rate for women ages 15 to 44 years decreased by 18% between 2008 and 2011, almost half of pregnancies in the United States remain unintended.1 On a more positive note, however, women who use birth control consistently and correctly account for only 5% of unintended pregnancies.2 As family physicians (FPs), we can support and facilitate our female patients’ efforts to consistently use highly effective forms of contraception. The 5 initiatives detailed here can help toward that end.

1. Routinely screen patients for their reproductive intentions

All women of reproductive age should be screened routinely for their pregnancy intentions. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) encourages clinicians to ask women about pregnancy intendedness and encourages patients to develop a reproductive life plan, or a set of personal goals about whether or when to have children.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also developed a reproductive life plan tool for health professionals to encourage women and men to reflect upon their plans.4 So just as we regularly screen and document cigarette use and blood pressure (BP), so too, should we routinely screen women for their reproductive goals.

Ask women this one question. The Oregon Foundation for Reproductive Health launched the One Key Question Initiative, which proposes that the care team ask women ages 18 to 50: “Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?”5 A common workflow includes the medical assistant asking women about pregnancy intentions and providing a preconception and/or contraceptive handout, if appropriate. The physician provides additional counseling as needed. Pilot studies of One Key Question indicate that 30% to 40% of women screened needed follow-up counseling, suggesting the need for clinicians to be proactive in asking about reproductive plans. (Additional information on the Initiative is available on the Foundation’s Web site at http://www.orfrh.org/.)

This approach assumes women feel in control of their reproduction; however, this may not be the reality for many, especially low-income women.6 Additionally, women commonly cite planning a pregnancy as appropriate only when they are in an ideal relationship and when they are living in a financially stable environment—conditions that some women may never achieve.

Another caveat is that women may not have explicit pregnancy intentions, in which case, this particular approach may not be effective. A study of low-income women found only 60% intended to use the method prescribed after contraception counseling, with 37% of those stopping because of adverse effects, 23% saying they wanted another method, and 17% citing method complexity.7

Reproductive coercion from male partners, ranging from pressure to become pregnant to method sabotage, is also common in low-income women.8 Regular conversations that prioritize a woman’s values and experience are needed to promote reproductive autonomy.

2. Decouple provision of contraception from unnecessary exams

Pelvic exams and pap smears should not be required prior to offering patients hormonal contraception, according to the Choosing Wisely campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine and ACOG.9,10 Hormonal contraception may instead be provided safely based on a medical history and BP assessment. Adolescents, minority groups, obese women, and victims of sexual trauma, in particular may avoid asking about birth control because of anxiety and fear of pain from these exams.11 The American College of Physicians recommends against speculum and bimanual exams in asymptomatic, non-pregnant, adult women.12 Pap smears and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing should be performed at their normally scheduled intervals as recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and not be tied to contraceptive provision.13

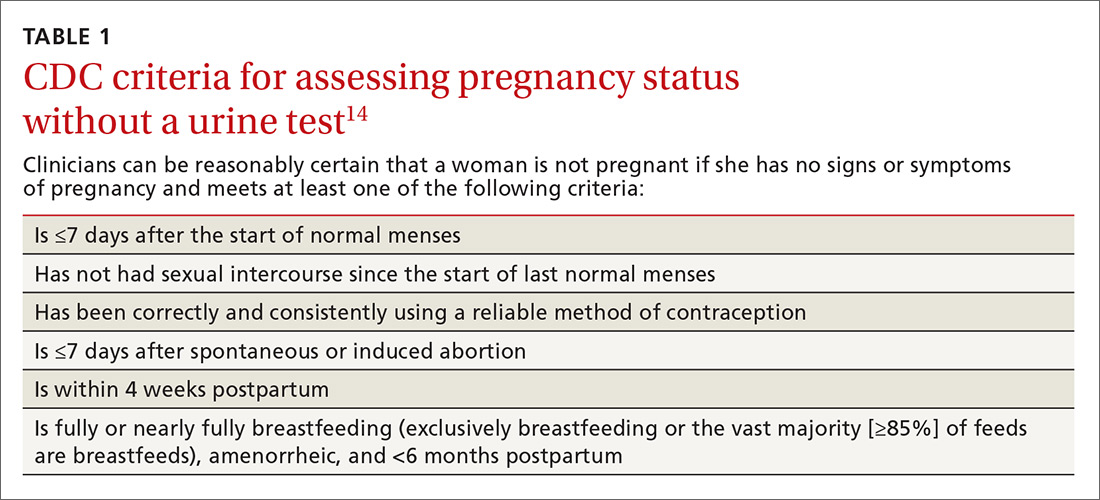

Assess pregnancy status using criteria,rather than a pregnancy text

Use the CDC’s criteria to assess pregnancy status rather than relying on a urine pregnancy test prior to providing contraception. Once you are reasonably sure that a woman is not pregnant (TABLE 114), contraception may be started. Some physicians have traditionally requested that a woman delay starting contraception until the next menses to ensure that she is not already pregnant. However, given the evidence that hormonal contraception does not cause birth defects, such a delay is not warranted and puts the woman at risk of an unintended pregnancy during the gap.15

Furthermore, there is an approximate 2-week window in which a woman could have a negative urine pregnancy test despite being pregnant, so the test alone is not completely reliable. In addition, obese women may experience irregular cycles, further complicating the traditional approach.16

Another largely unnecessary step … The US Selected Practice Recommendations (US SPR) from the CDC notes that additional STI screening prior to an intrauterine device (IUD) insertion is unnecessary for most women if appropriate screening guidelines have been previously followed.14 For those who have not been screened according to guidelines, the CDC recommends same-day screening and IUD insertion. You can then treat an STI without removing the IUD. Women with purulent cervicitis or a current chlamydial or gonorrheal infection should delay IUD insertion until after treatment.

3. Expand long-acting reversible contraception counseling and access

Offer long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as IUDs and implants, as first-line options for most women. ACOG endorses LARC as the most effective reversible method for most women, including those who have not given birth and adolescents.17 Unfortunately, a 2012 study found that family physicians were less likely than OB-GYNs to have enough time for contraceptive counseling and fewer than half felt competent inserting IUDs.18 While 79% of OB-GYNs routinely discussed IUDs with their patients, only 47% of family physicians did. In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) endorsed a LARC-first tiered counseling approach for adolescents.19

A test of LARC-first counseling

The Contraceptive CHOICE project, a St. Louis, Missouri-based initiative, was launched to reduce unintended pregnancies in women ages 14 to 45 years by offering LARC-first counseling and free contraception of their choice.20 This project involved more than 9000 women at high risk for unintended pregnancy. Same-day LARC insertion was available. Seventy-five percent of women chose a LARC method and they reported greater continuation at 12 and 24 months, when compared to women who did not choose a LARC method. LARC users also reported higher satisfaction at one year. Provision of contraception through the project contributed to a reduction in repeat abortions as well as decreased rates of teenage pregnancy, birth, and abortion. Three years after the start of the project, IUDs had continuation rates of nearly 70%, implants of 56%, and non-LARC methods of 31%.21

When counseling women, it’s important to remember that effectiveness may not be the only criterium a woman uses when choosing a method. A 2010 study found that for 91% of women at high risk for unintended pregnancy, no single method possessed all the features they deemed “extremely important.”22 Clinicians should take a patient-centered approach to find birth control that fits each patient’s priorities.

Clinicians need proper training in LARC methods

Only 20% of FPs regularly insert IUDs, and 11% offer contraceptive implants, according to estimates from physicians recertifying with the American Board of Family Medicine in 2014.23 Access to training during residency is a key component to increasing these rates. FPs who practice obstetrics should be trained in postpartum LARC insertion and offer this option prior to hospital discharge as well as during the postpartum office visit.

Performing LARC insertions on the same day as counseling is ideal, and clinics should strive to reduce barriers to same-day procedures. Time constraints may be addressed by shifting tasks among the medical team. In the CHOICE project, contraceptive counselors—half of whom had no clinical experience—were trained to provide tiered counseling to participants. By working with a cross-trained health care team and offering prepared resources, clinicians can save time and improve access.

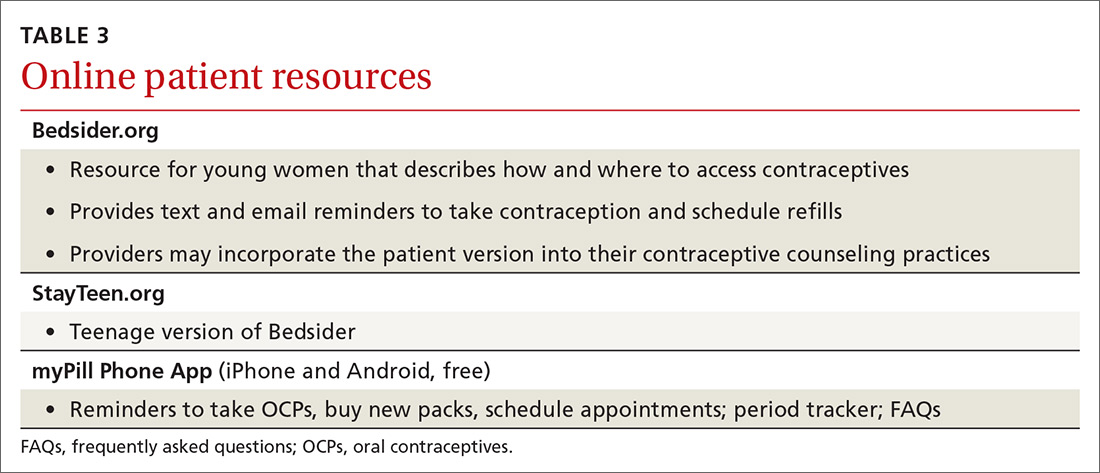

Physicians may want to incorporate the free online resources Bedsider.org or Stayteen.org to help women learn about contraceptive methods.24 The user-friendly Web sites, operated by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, describe various forms of contraception and offer text and email reminders. Incorporating Bedsider into the counseling workflow and discussing the various reminder tools available may improve patients’ knowledge and enhance their compliance.

Additional barriers for practices may include high upfront costs associated with stocking devices. Practices that may be unable to sustain the costs surrounding enhanced contraception counseling and provision can collaborate with family planning clinics that are able to offer same-day services. A study of clinics in California found that Title X clinics were more likely to provide on-site LARC services than non-Title X public and private providers.25

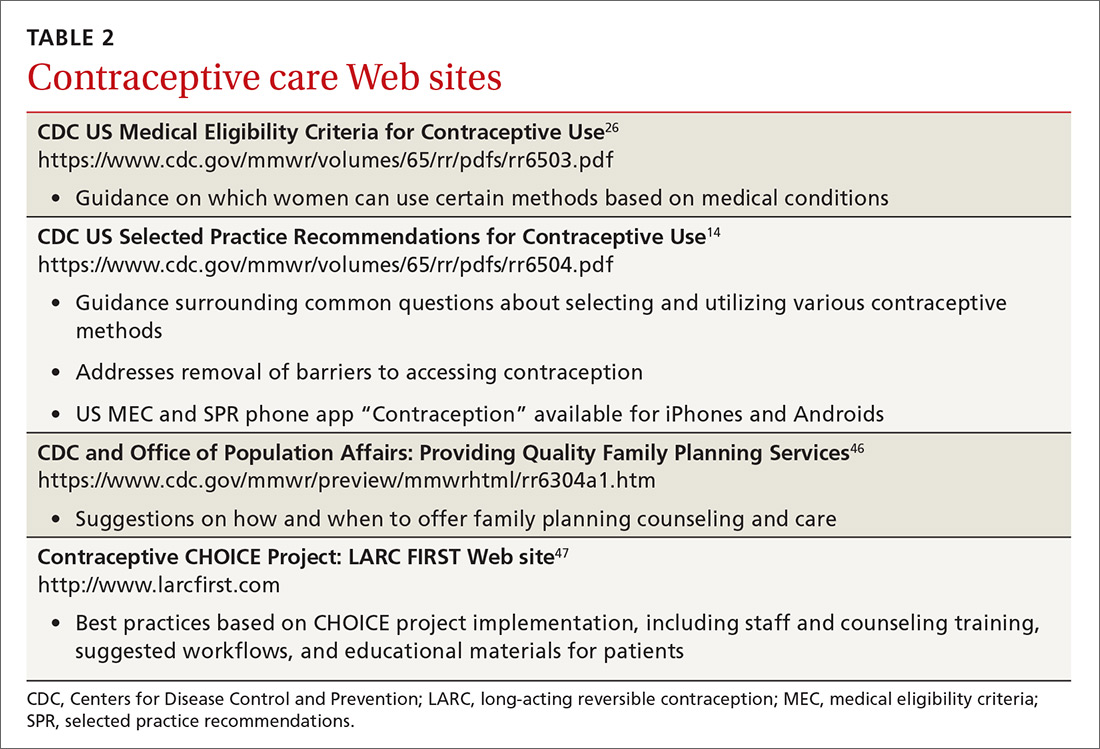

4. Follow CDC guidelines for initiating and continuing contraception

Follow the US SPR for guidance on initiating and continuing contraceptive methods.14 The CDC’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use is another vital resource, providing recommendations for contraceptive methods to patients who have specific medical conditions or characteristics.26

Utilize the “quick start” method for hormonal contraception, where birth control is started on the same day as its prescription regardless of timing of the menstrual cycle. If you can’t be reasonably certain that a woman is not pregnant based on the criteria listed in TABLE 1,14 conduct a pregnancy test (while recognizing the aforementioned 2-week window of limitations) and counsel the patient to use back-up protection for the first 7 days along with repeating a pregnancy test in 2 weeks’ time.

The quick start method may lead to higher adherence than delayed initiation.27 Differences in continuation rates between women who use the quick start method and those who follow the delayed approach may disappear over time.28

Prescribe and provide a year’s supply of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) as recommended by the CDC US SPR.14 It is important to note that pharmacists are usually restricted by insurance companies to only fill a one or 3 month’s supply.

In January 2016, Oregon began requiring private and state health insurance providers to reimburse for a year’s supply of prescription contraception; in January 2017, insurers in Washington, DC, were also required to offer women a year’s supply of prescription contraception.29,30 Several other states have followed suit. The California Health Benefits Review Program estimates a savings of $42.8 million a year from fewer office visits and 15,000 fewer unintended pregnancies if their state enacts a similar policy.31

Pharmacist initiatives are worth watching. In January 2016, Oregon pharmacists with additional training were allowed to prescribe OCs and hormonal patches to women 18 years and older.32 In April 2016, a similar law went into effect in California, but without a minimum age requirement and with the additional coverage of vaginal rings and Depo-Provera (depo) injections.33 Pharmacists in both states must review a health questionnaire completed by the woman and can refer to a physician as necessary.

The CDC recommends that clinicians extend the allowed window for repeat depo injections to 15 weeks.14 Common institutional protocol is to give repeat injections every 11 to 13 weeks. If past that window, protocol often dictates the woman abstain from unprotected sex for 2 weeks and then return for a negative pregnancy test (or await menses) before the next injection. However, the CDC notes that depo is effective for longer than the 13-week period.14 No additional birth control or pregnancy testing is needed and the woman can receive the next depo shot if she is up to 15 weeks from the previous shot.

One study found no additional pregnancy risks for those who were up to 4 weeks “late” for their next shot, suggesting there is potential for an even larger grace period.34 The World Health Organization advises allowing a repeat injection up to 4 weeks late.35 We encourage institutions to change their policies to comply with the CDC’s 15-week window.

Another initiative is over-the-counter (OTC) access to OCs, which the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and ACOG support.36,37 ACOG notes that “no drug or intervention is completely without risk of harm” and that the risk of venous thromboembolism for OC users is lower than the risk of pregnancy.37 Women can successfully self-screen for contraindications using a checklist. Concerns about women potentially being less adherent or less likely to choose LARCs are not reasons to preclude access to other methods. The AAFP supports insurance coverage of OCs, regardless of prescription status.36

5. Routinely counsel about, and advance-prescribe, emergency contraception pills

Physicians should counsel and advance-prescribe emergency contraception pills (ECPs) to women, including adolescents, using less reliable contraception, as recommended by ACOG, AAP, and the CDC.14,37,38 It’s also important to provide information on the copper IUD as the most effective method of emergency contraception, with nearly 100% efficacy if placed within 5 days.39 An easy-to-read patient hand-out in English and Spanish on EC options can be found at http://beyondthepill.ucsf.edu/tools-materials.

Only 3% of respondents participating in the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth received counseling about emergency contraception in the past year.40 ECPs are most effective when used within 24 hours but have some efficacy up to 5 days.37 Due to the Affordable Care Act, most insurance plans will cover ECPs if purchased with a prescription, but coverage varies by state.41 Ulipristal acetate (UPA) ECP is only available with a prescription. Advance prescriptions can alleviate financial burdens on women when they need to access ECPs quickly.

Women should wait at least 5 days before resuming or starting hormonal contraception after taking UPA-based ECP, as it may reduce the ovulation-delaying effect of the ECP.14 For IUDs, implants, and depo, which require a visit to a health care provider, physicians evaluating earlier provision should consider the risks of reduced efficacy against the many barriers to access.

UPA-based ECPs (such as ella) may be more effective for overweight and obese women than levonorgestrel-based ECPs (such as Plan B and Next Choice).14 Consider advance-prescribing UPA ECPs to women with a body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2.42 Such considerations are important as the prevalence of obesity in women between 2013 and 2014 was 40.4%.43

In May 2016, the FDA noted that while current data are insufficient regarding whether the effectiveness of levonorgestrel ECPs is reduced in overweight or obese women, there are no safety concerns regarding their use in this population.44 Therefore, a woman with a BMI >25 kg/m2 should use UPA ECPs if available; but if not, she can still use levonorgestrel ECPs. One study, however, has found that UPA ECPs are only as effective as a placebo when BMI is ≥35 kg/m2, at which point a copper IUD may be the only effective form of emergency contraception.45

Transitioning from customary practices to best practices

Following these practical steps, FPs can improve contraceptive care for women. However, to make a significant impact, clinicians must be willing to change customary practices that are based on tradition, routines, or outdated protocols in favor of those based on current evidence.

One good place to start the transition to best practices is to familiarize yourself with the 2016 US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use26 and Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use.14 TABLES 214,26,46,47 and 3 offer additional resources that can enhance contraceptive counseling and further promote access to contraceptive care.

The contraceptive coverage guarantee under the Affordable Care Act has allowed many women to make contraceptive choices based on personal needs and preferences rather than cost. The new contraceptive coverage exemptions issued under the Trump administration will bring cost back as the driving decision factor for women whose employers choose not to provide contraceptive coverage. Providers should be aware of the typical costs associated with the various contraceptive options offered in their practice and community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Dalby, MD, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1102 South Park St, Suite 100, Madison, WI 53715; Jessica.Dalby@fammed.wisc.edu.

1. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374:843-852.

2. Sonfield A, Hasstedt K, Gold RB. Moving Forward: Family Planning in the Era of Health Reform. New York: Guttmacher Institute. 2014. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/moving-forward-family-planning-era-health-reform. Accessed October 5, 2017.

3. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Reproductive Life Planning to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2016. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Reproductive-Life-Planning-to-Reduce-Unintended-Pregnancy. Accessed October 5, 2017.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive Life Plan Tool for Health Care Providers. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/preconception/rlptool.html. Accessed August 31, 2016.

5. Oregon Health Authority. Effective Contraceptive Use among Women at Risk of Unintended Pregnancy Guidance Document. 2014. Available at: http://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/ANALYTICS/CCOData/Effective%20Contraceptive%20Use%20Guidance%20Document.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

6. Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Steinberg JR, et al. “It just happens”: a qualitative study exploring low-income women’s perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception. 2015;91:150-156.

7. Yee LM, Farner KC, King E, et al. What do women want? Experiences of low-income women with postpartum contraception and contraceptive counseling. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2015;2.

8. Kalichman SC, Williams EA, Cherry C, et al. Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. J Womens Health. 1998;7:371-378.

9. ABIM Foundation. Pelvic Exams, Pap Tests and Oral Contraceptives. 2016. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/patient-resources/pelvic-exams-pap-tests-and-oral-contraceptives/. Accessed May 31, 2016.

10. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Access to Contraception: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2015. Number 615. Available at: https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=201710. Accessed October 5, 2017.

11. Bates CK, Carroll N, Potter J. The challenging pelvic examination. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:651-657.

12. Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Harris R, et al. Screening pelvic examination in adult women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:67-72.

13. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Cervical Cancer: Screening. 2012. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening. Accessed May 25, 2016.

14. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

15. Lesnewski R, Prine L. Initiating hormonal contraception. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:105-112.

16. Jacobsen BK, Knutsen SF, Oda K, et al. Obesity at age 20 and the risk of miscarriages, irregular periods and reported problems of becoming pregnant: the Adventist Health Study-2. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012; 27:923-931.

17. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Increasing Access to Contraceptive Implants and Intrauterine Devices to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2015. Number 642. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Increasing-Access-to-Contraceptive-Implants-and-Intrauterine-Devices-to-Reduce-Unintended-Pregnancy. Accessed October 5, 2017.

18. Harper CC, Henderson JT, Raine TR, et al. Evidence-based IUD practice: family physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists. Fam Med. 2012;44:637-645.

19. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence. Policy statement: Contraception for Adolescents. 2014. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2014/09/24/peds.2014-2299.full.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

20. Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancy: The Contraceptive CHOICE Project in review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:349-353.

21. Diedrich JT, Zhao Q, Madden T, et al. Three-year continuation of reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:662.e1-e8.

22. Lessard LN, Karasek D, Ma S, et al. Contraceptive features preferred by women at high risk of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44:194-200.

23. Nisen MB, Peterson LE, Cochrane A, et al. US family physicians’ intrauterine and implantable contraception provision: results from a national survey. Contraception. 2016;93:432-437.

24. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Bedsider. Available at: https://bedsider.org/. Accessed June 14, 2016.

25. Park HY, Rodriguez MI, Hulett D, et al. Long-acting reversible contraception method use among Title X providers and non-Title X providers in California. Contraception. 2012;86:557-561.

26. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

27. Westhoff C, Kerns J, Morroni C, et al. Quick start: novel oral contraceptive initiation method. Contraception. 2002;66:141-145.

28. Brahmi D, Curtis KM. When can a woman start combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs)? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:524-538.

29. Lachman S. Oregon To Require Insurers To Cover A Year’s Supply Of Birth Control. Huffington Post. June 11, 2015. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/11/oregon-birth-control-_n_7564712.html. Accessed October 16, 2017.

30. Andrews M. D.C. Women To Get Access To Full Year’s Worth Of Contraceptives. Kaiser Health News. September 25, 2015. Available at: https://khn.org/news/d-c-women-to-get-access-to-full-years-worth-of-contraceptives/. Accessed October 16, 2017.

31. Analysis of California Senate Bill (SB) 999 Contraceptives: Annual Supply: A Report to the 2015-2016 California State Legislature: California Health Benefits Review Program. 2016. Available at: http://chbrp.ucop.edu/index.php?action=read&bill_id=195&doc_type=1000. Accessed October 5, 2017.

32. Frazier A. Pharmacist-prescribed birth control in effect Jan 1. KOIN News. December 30, 2015. Available at: http://koin.com/2015/12/30/pharmacist-provided-birth-control-in-effect-jan-1/. Accessed October 5, 2017.

33. Karlamangla S. Birth control pills without prescriptions, coming soon to California under new law. Los Angeles Times. February 14, 2016. Available at: http://www.latimes.com/health/la-me-birth-control-pharmacies-20160214-story.html. Accessed October 16, 2017.

34. Steiner MJ, Kwok C, Stanback J, et al. Injectable contraception: what should the longest interval be for reinjections? Contraception. 2008;77:410-414.

35. World Health Organization. Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers. 2011. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44028/1/9780978856373_eng.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

36. American Academy of Family Physicians. Over-the-Counter Oral Contraceptives. 2014; Available at: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/otc-oral-contraceptives.html. Accessed June 2, 2016.

37. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Over-the-Counter Access to Oral Contraceptives: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2012. Number 544. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Over-the-Counter-Access-to-Oral-Contraceptives. Accessed October 5, 2017.

38. Committee on Adolescence. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2012;130:1174-1182.

39. Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, et al. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1994-2000.

40. Martinez G, Chandra A, Febo-Vazquez I, et al. Use of Family Planning and Related Medical Services Among Women Aged 15–44 in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006–2010: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr068.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

41. Guttmacher Institute. Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives: Guttmacher Institute;2017. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/insurance-coverage-contraceptives Accessed October 7, 2017.

42. Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84:363-367.

43. Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2284-2291.

44. US Food & Drug Administration. Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers - Plan B (0.75mg levonorgestrel) and Plan B One-Step (1.5 mg levonorgestrel) Tablets Information. 2016; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm109775.htm. Accessed May 25, 2016.

45. Simmons KB, Edelman AB. Contraception and sexual health in obese women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29:466-478.

46. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63:1-29.

47. LARC FIRST. Available at: http://www.larcfirst.com/index.html. Accessed May 2016.

While the unintended pregnancy rate for women ages 15 to 44 years decreased by 18% between 2008 and 2011, almost half of pregnancies in the United States remain unintended.1 On a more positive note, however, women who use birth control consistently and correctly account for only 5% of unintended pregnancies.2 As family physicians (FPs), we can support and facilitate our female patients’ efforts to consistently use highly effective forms of contraception. The 5 initiatives detailed here can help toward that end.

1. Routinely screen patients for their reproductive intentions

All women of reproductive age should be screened routinely for their pregnancy intentions. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) encourages clinicians to ask women about pregnancy intendedness and encourages patients to develop a reproductive life plan, or a set of personal goals about whether or when to have children.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also developed a reproductive life plan tool for health professionals to encourage women and men to reflect upon their plans.4 So just as we regularly screen and document cigarette use and blood pressure (BP), so too, should we routinely screen women for their reproductive goals.

Ask women this one question. The Oregon Foundation for Reproductive Health launched the One Key Question Initiative, which proposes that the care team ask women ages 18 to 50: “Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?”5 A common workflow includes the medical assistant asking women about pregnancy intentions and providing a preconception and/or contraceptive handout, if appropriate. The physician provides additional counseling as needed. Pilot studies of One Key Question indicate that 30% to 40% of women screened needed follow-up counseling, suggesting the need for clinicians to be proactive in asking about reproductive plans. (Additional information on the Initiative is available on the Foundation’s Web site at http://www.orfrh.org/.)

This approach assumes women feel in control of their reproduction; however, this may not be the reality for many, especially low-income women.6 Additionally, women commonly cite planning a pregnancy as appropriate only when they are in an ideal relationship and when they are living in a financially stable environment—conditions that some women may never achieve.

Another caveat is that women may not have explicit pregnancy intentions, in which case, this particular approach may not be effective. A study of low-income women found only 60% intended to use the method prescribed after contraception counseling, with 37% of those stopping because of adverse effects, 23% saying they wanted another method, and 17% citing method complexity.7

Reproductive coercion from male partners, ranging from pressure to become pregnant to method sabotage, is also common in low-income women.8 Regular conversations that prioritize a woman’s values and experience are needed to promote reproductive autonomy.

2. Decouple provision of contraception from unnecessary exams

Pelvic exams and pap smears should not be required prior to offering patients hormonal contraception, according to the Choosing Wisely campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine and ACOG.9,10 Hormonal contraception may instead be provided safely based on a medical history and BP assessment. Adolescents, minority groups, obese women, and victims of sexual trauma, in particular may avoid asking about birth control because of anxiety and fear of pain from these exams.11 The American College of Physicians recommends against speculum and bimanual exams in asymptomatic, non-pregnant, adult women.12 Pap smears and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing should be performed at their normally scheduled intervals as recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and not be tied to contraceptive provision.13

Assess pregnancy status using criteria,rather than a pregnancy text

Use the CDC’s criteria to assess pregnancy status rather than relying on a urine pregnancy test prior to providing contraception. Once you are reasonably sure that a woman is not pregnant (TABLE 114), contraception may be started. Some physicians have traditionally requested that a woman delay starting contraception until the next menses to ensure that she is not already pregnant. However, given the evidence that hormonal contraception does not cause birth defects, such a delay is not warranted and puts the woman at risk of an unintended pregnancy during the gap.15

Furthermore, there is an approximate 2-week window in which a woman could have a negative urine pregnancy test despite being pregnant, so the test alone is not completely reliable. In addition, obese women may experience irregular cycles, further complicating the traditional approach.16

Another largely unnecessary step … The US Selected Practice Recommendations (US SPR) from the CDC notes that additional STI screening prior to an intrauterine device (IUD) insertion is unnecessary for most women if appropriate screening guidelines have been previously followed.14 For those who have not been screened according to guidelines, the CDC recommends same-day screening and IUD insertion. You can then treat an STI without removing the IUD. Women with purulent cervicitis or a current chlamydial or gonorrheal infection should delay IUD insertion until after treatment.

3. Expand long-acting reversible contraception counseling and access

Offer long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as IUDs and implants, as first-line options for most women. ACOG endorses LARC as the most effective reversible method for most women, including those who have not given birth and adolescents.17 Unfortunately, a 2012 study found that family physicians were less likely than OB-GYNs to have enough time for contraceptive counseling and fewer than half felt competent inserting IUDs.18 While 79% of OB-GYNs routinely discussed IUDs with their patients, only 47% of family physicians did. In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) endorsed a LARC-first tiered counseling approach for adolescents.19

A test of LARC-first counseling

The Contraceptive CHOICE project, a St. Louis, Missouri-based initiative, was launched to reduce unintended pregnancies in women ages 14 to 45 years by offering LARC-first counseling and free contraception of their choice.20 This project involved more than 9000 women at high risk for unintended pregnancy. Same-day LARC insertion was available. Seventy-five percent of women chose a LARC method and they reported greater continuation at 12 and 24 months, when compared to women who did not choose a LARC method. LARC users also reported higher satisfaction at one year. Provision of contraception through the project contributed to a reduction in repeat abortions as well as decreased rates of teenage pregnancy, birth, and abortion. Three years after the start of the project, IUDs had continuation rates of nearly 70%, implants of 56%, and non-LARC methods of 31%.21

When counseling women, it’s important to remember that effectiveness may not be the only criterium a woman uses when choosing a method. A 2010 study found that for 91% of women at high risk for unintended pregnancy, no single method possessed all the features they deemed “extremely important.”22 Clinicians should take a patient-centered approach to find birth control that fits each patient’s priorities.

Clinicians need proper training in LARC methods

Only 20% of FPs regularly insert IUDs, and 11% offer contraceptive implants, according to estimates from physicians recertifying with the American Board of Family Medicine in 2014.23 Access to training during residency is a key component to increasing these rates. FPs who practice obstetrics should be trained in postpartum LARC insertion and offer this option prior to hospital discharge as well as during the postpartum office visit.

Performing LARC insertions on the same day as counseling is ideal, and clinics should strive to reduce barriers to same-day procedures. Time constraints may be addressed by shifting tasks among the medical team. In the CHOICE project, contraceptive counselors—half of whom had no clinical experience—were trained to provide tiered counseling to participants. By working with a cross-trained health care team and offering prepared resources, clinicians can save time and improve access.

Physicians may want to incorporate the free online resources Bedsider.org or Stayteen.org to help women learn about contraceptive methods.24 The user-friendly Web sites, operated by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, describe various forms of contraception and offer text and email reminders. Incorporating Bedsider into the counseling workflow and discussing the various reminder tools available may improve patients’ knowledge and enhance their compliance.

Additional barriers for practices may include high upfront costs associated with stocking devices. Practices that may be unable to sustain the costs surrounding enhanced contraception counseling and provision can collaborate with family planning clinics that are able to offer same-day services. A study of clinics in California found that Title X clinics were more likely to provide on-site LARC services than non-Title X public and private providers.25

4. Follow CDC guidelines for initiating and continuing contraception

Follow the US SPR for guidance on initiating and continuing contraceptive methods.14 The CDC’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use is another vital resource, providing recommendations for contraceptive methods to patients who have specific medical conditions or characteristics.26

Utilize the “quick start” method for hormonal contraception, where birth control is started on the same day as its prescription regardless of timing of the menstrual cycle. If you can’t be reasonably certain that a woman is not pregnant based on the criteria listed in TABLE 1,14 conduct a pregnancy test (while recognizing the aforementioned 2-week window of limitations) and counsel the patient to use back-up protection for the first 7 days along with repeating a pregnancy test in 2 weeks’ time.

The quick start method may lead to higher adherence than delayed initiation.27 Differences in continuation rates between women who use the quick start method and those who follow the delayed approach may disappear over time.28

Prescribe and provide a year’s supply of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) as recommended by the CDC US SPR.14 It is important to note that pharmacists are usually restricted by insurance companies to only fill a one or 3 month’s supply.

In January 2016, Oregon began requiring private and state health insurance providers to reimburse for a year’s supply of prescription contraception; in January 2017, insurers in Washington, DC, were also required to offer women a year’s supply of prescription contraception.29,30 Several other states have followed suit. The California Health Benefits Review Program estimates a savings of $42.8 million a year from fewer office visits and 15,000 fewer unintended pregnancies if their state enacts a similar policy.31

Pharmacist initiatives are worth watching. In January 2016, Oregon pharmacists with additional training were allowed to prescribe OCs and hormonal patches to women 18 years and older.32 In April 2016, a similar law went into effect in California, but without a minimum age requirement and with the additional coverage of vaginal rings and Depo-Provera (depo) injections.33 Pharmacists in both states must review a health questionnaire completed by the woman and can refer to a physician as necessary.

The CDC recommends that clinicians extend the allowed window for repeat depo injections to 15 weeks.14 Common institutional protocol is to give repeat injections every 11 to 13 weeks. If past that window, protocol often dictates the woman abstain from unprotected sex for 2 weeks and then return for a negative pregnancy test (or await menses) before the next injection. However, the CDC notes that depo is effective for longer than the 13-week period.14 No additional birth control or pregnancy testing is needed and the woman can receive the next depo shot if she is up to 15 weeks from the previous shot.

One study found no additional pregnancy risks for those who were up to 4 weeks “late” for their next shot, suggesting there is potential for an even larger grace period.34 The World Health Organization advises allowing a repeat injection up to 4 weeks late.35 We encourage institutions to change their policies to comply with the CDC’s 15-week window.

Another initiative is over-the-counter (OTC) access to OCs, which the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and ACOG support.36,37 ACOG notes that “no drug or intervention is completely without risk of harm” and that the risk of venous thromboembolism for OC users is lower than the risk of pregnancy.37 Women can successfully self-screen for contraindications using a checklist. Concerns about women potentially being less adherent or less likely to choose LARCs are not reasons to preclude access to other methods. The AAFP supports insurance coverage of OCs, regardless of prescription status.36

5. Routinely counsel about, and advance-prescribe, emergency contraception pills

Physicians should counsel and advance-prescribe emergency contraception pills (ECPs) to women, including adolescents, using less reliable contraception, as recommended by ACOG, AAP, and the CDC.14,37,38 It’s also important to provide information on the copper IUD as the most effective method of emergency contraception, with nearly 100% efficacy if placed within 5 days.39 An easy-to-read patient hand-out in English and Spanish on EC options can be found at http://beyondthepill.ucsf.edu/tools-materials.

Only 3% of respondents participating in the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth received counseling about emergency contraception in the past year.40 ECPs are most effective when used within 24 hours but have some efficacy up to 5 days.37 Due to the Affordable Care Act, most insurance plans will cover ECPs if purchased with a prescription, but coverage varies by state.41 Ulipristal acetate (UPA) ECP is only available with a prescription. Advance prescriptions can alleviate financial burdens on women when they need to access ECPs quickly.

Women should wait at least 5 days before resuming or starting hormonal contraception after taking UPA-based ECP, as it may reduce the ovulation-delaying effect of the ECP.14 For IUDs, implants, and depo, which require a visit to a health care provider, physicians evaluating earlier provision should consider the risks of reduced efficacy against the many barriers to access.

UPA-based ECPs (such as ella) may be more effective for overweight and obese women than levonorgestrel-based ECPs (such as Plan B and Next Choice).14 Consider advance-prescribing UPA ECPs to women with a body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2.42 Such considerations are important as the prevalence of obesity in women between 2013 and 2014 was 40.4%.43

In May 2016, the FDA noted that while current data are insufficient regarding whether the effectiveness of levonorgestrel ECPs is reduced in overweight or obese women, there are no safety concerns regarding their use in this population.44 Therefore, a woman with a BMI >25 kg/m2 should use UPA ECPs if available; but if not, she can still use levonorgestrel ECPs. One study, however, has found that UPA ECPs are only as effective as a placebo when BMI is ≥35 kg/m2, at which point a copper IUD may be the only effective form of emergency contraception.45

Transitioning from customary practices to best practices

Following these practical steps, FPs can improve contraceptive care for women. However, to make a significant impact, clinicians must be willing to change customary practices that are based on tradition, routines, or outdated protocols in favor of those based on current evidence.

One good place to start the transition to best practices is to familiarize yourself with the 2016 US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use26 and Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use.14 TABLES 214,26,46,47 and 3 offer additional resources that can enhance contraceptive counseling and further promote access to contraceptive care.

The contraceptive coverage guarantee under the Affordable Care Act has allowed many women to make contraceptive choices based on personal needs and preferences rather than cost. The new contraceptive coverage exemptions issued under the Trump administration will bring cost back as the driving decision factor for women whose employers choose not to provide contraceptive coverage. Providers should be aware of the typical costs associated with the various contraceptive options offered in their practice and community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Dalby, MD, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1102 South Park St, Suite 100, Madison, WI 53715; Jessica.Dalby@fammed.wisc.edu.

While the unintended pregnancy rate for women ages 15 to 44 years decreased by 18% between 2008 and 2011, almost half of pregnancies in the United States remain unintended.1 On a more positive note, however, women who use birth control consistently and correctly account for only 5% of unintended pregnancies.2 As family physicians (FPs), we can support and facilitate our female patients’ efforts to consistently use highly effective forms of contraception. The 5 initiatives detailed here can help toward that end.

1. Routinely screen patients for their reproductive intentions

All women of reproductive age should be screened routinely for their pregnancy intentions. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) encourages clinicians to ask women about pregnancy intendedness and encourages patients to develop a reproductive life plan, or a set of personal goals about whether or when to have children.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has also developed a reproductive life plan tool for health professionals to encourage women and men to reflect upon their plans.4 So just as we regularly screen and document cigarette use and blood pressure (BP), so too, should we routinely screen women for their reproductive goals.

Ask women this one question. The Oregon Foundation for Reproductive Health launched the One Key Question Initiative, which proposes that the care team ask women ages 18 to 50: “Would you like to become pregnant in the next year?”5 A common workflow includes the medical assistant asking women about pregnancy intentions and providing a preconception and/or contraceptive handout, if appropriate. The physician provides additional counseling as needed. Pilot studies of One Key Question indicate that 30% to 40% of women screened needed follow-up counseling, suggesting the need for clinicians to be proactive in asking about reproductive plans. (Additional information on the Initiative is available on the Foundation’s Web site at http://www.orfrh.org/.)

This approach assumes women feel in control of their reproduction; however, this may not be the reality for many, especially low-income women.6 Additionally, women commonly cite planning a pregnancy as appropriate only when they are in an ideal relationship and when they are living in a financially stable environment—conditions that some women may never achieve.

Another caveat is that women may not have explicit pregnancy intentions, in which case, this particular approach may not be effective. A study of low-income women found only 60% intended to use the method prescribed after contraception counseling, with 37% of those stopping because of adverse effects, 23% saying they wanted another method, and 17% citing method complexity.7

Reproductive coercion from male partners, ranging from pressure to become pregnant to method sabotage, is also common in low-income women.8 Regular conversations that prioritize a woman’s values and experience are needed to promote reproductive autonomy.

2. Decouple provision of contraception from unnecessary exams

Pelvic exams and pap smears should not be required prior to offering patients hormonal contraception, according to the Choosing Wisely campaign of the American Board of Internal Medicine and ACOG.9,10 Hormonal contraception may instead be provided safely based on a medical history and BP assessment. Adolescents, minority groups, obese women, and victims of sexual trauma, in particular may avoid asking about birth control because of anxiety and fear of pain from these exams.11 The American College of Physicians recommends against speculum and bimanual exams in asymptomatic, non-pregnant, adult women.12 Pap smears and sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing should be performed at their normally scheduled intervals as recommended by the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and not be tied to contraceptive provision.13

Assess pregnancy status using criteria,rather than a pregnancy text

Use the CDC’s criteria to assess pregnancy status rather than relying on a urine pregnancy test prior to providing contraception. Once you are reasonably sure that a woman is not pregnant (TABLE 114), contraception may be started. Some physicians have traditionally requested that a woman delay starting contraception until the next menses to ensure that she is not already pregnant. However, given the evidence that hormonal contraception does not cause birth defects, such a delay is not warranted and puts the woman at risk of an unintended pregnancy during the gap.15

Furthermore, there is an approximate 2-week window in which a woman could have a negative urine pregnancy test despite being pregnant, so the test alone is not completely reliable. In addition, obese women may experience irregular cycles, further complicating the traditional approach.16

Another largely unnecessary step … The US Selected Practice Recommendations (US SPR) from the CDC notes that additional STI screening prior to an intrauterine device (IUD) insertion is unnecessary for most women if appropriate screening guidelines have been previously followed.14 For those who have not been screened according to guidelines, the CDC recommends same-day screening and IUD insertion. You can then treat an STI without removing the IUD. Women with purulent cervicitis or a current chlamydial or gonorrheal infection should delay IUD insertion until after treatment.

3. Expand long-acting reversible contraception counseling and access

Offer long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), such as IUDs and implants, as first-line options for most women. ACOG endorses LARC as the most effective reversible method for most women, including those who have not given birth and adolescents.17 Unfortunately, a 2012 study found that family physicians were less likely than OB-GYNs to have enough time for contraceptive counseling and fewer than half felt competent inserting IUDs.18 While 79% of OB-GYNs routinely discussed IUDs with their patients, only 47% of family physicians did. In 2014, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) endorsed a LARC-first tiered counseling approach for adolescents.19

A test of LARC-first counseling

The Contraceptive CHOICE project, a St. Louis, Missouri-based initiative, was launched to reduce unintended pregnancies in women ages 14 to 45 years by offering LARC-first counseling and free contraception of their choice.20 This project involved more than 9000 women at high risk for unintended pregnancy. Same-day LARC insertion was available. Seventy-five percent of women chose a LARC method and they reported greater continuation at 12 and 24 months, when compared to women who did not choose a LARC method. LARC users also reported higher satisfaction at one year. Provision of contraception through the project contributed to a reduction in repeat abortions as well as decreased rates of teenage pregnancy, birth, and abortion. Three years after the start of the project, IUDs had continuation rates of nearly 70%, implants of 56%, and non-LARC methods of 31%.21

When counseling women, it’s important to remember that effectiveness may not be the only criterium a woman uses when choosing a method. A 2010 study found that for 91% of women at high risk for unintended pregnancy, no single method possessed all the features they deemed “extremely important.”22 Clinicians should take a patient-centered approach to find birth control that fits each patient’s priorities.

Clinicians need proper training in LARC methods

Only 20% of FPs regularly insert IUDs, and 11% offer contraceptive implants, according to estimates from physicians recertifying with the American Board of Family Medicine in 2014.23 Access to training during residency is a key component to increasing these rates. FPs who practice obstetrics should be trained in postpartum LARC insertion and offer this option prior to hospital discharge as well as during the postpartum office visit.

Performing LARC insertions on the same day as counseling is ideal, and clinics should strive to reduce barriers to same-day procedures. Time constraints may be addressed by shifting tasks among the medical team. In the CHOICE project, contraceptive counselors—half of whom had no clinical experience—were trained to provide tiered counseling to participants. By working with a cross-trained health care team and offering prepared resources, clinicians can save time and improve access.

Physicians may want to incorporate the free online resources Bedsider.org or Stayteen.org to help women learn about contraceptive methods.24 The user-friendly Web sites, operated by the National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy, describe various forms of contraception and offer text and email reminders. Incorporating Bedsider into the counseling workflow and discussing the various reminder tools available may improve patients’ knowledge and enhance their compliance.

Additional barriers for practices may include high upfront costs associated with stocking devices. Practices that may be unable to sustain the costs surrounding enhanced contraception counseling and provision can collaborate with family planning clinics that are able to offer same-day services. A study of clinics in California found that Title X clinics were more likely to provide on-site LARC services than non-Title X public and private providers.25

4. Follow CDC guidelines for initiating and continuing contraception

Follow the US SPR for guidance on initiating and continuing contraceptive methods.14 The CDC’s Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use is another vital resource, providing recommendations for contraceptive methods to patients who have specific medical conditions or characteristics.26

Utilize the “quick start” method for hormonal contraception, where birth control is started on the same day as its prescription regardless of timing of the menstrual cycle. If you can’t be reasonably certain that a woman is not pregnant based on the criteria listed in TABLE 1,14 conduct a pregnancy test (while recognizing the aforementioned 2-week window of limitations) and counsel the patient to use back-up protection for the first 7 days along with repeating a pregnancy test in 2 weeks’ time.

The quick start method may lead to higher adherence than delayed initiation.27 Differences in continuation rates between women who use the quick start method and those who follow the delayed approach may disappear over time.28

Prescribe and provide a year’s supply of oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) as recommended by the CDC US SPR.14 It is important to note that pharmacists are usually restricted by insurance companies to only fill a one or 3 month’s supply.

In January 2016, Oregon began requiring private and state health insurance providers to reimburse for a year’s supply of prescription contraception; in January 2017, insurers in Washington, DC, were also required to offer women a year’s supply of prescription contraception.29,30 Several other states have followed suit. The California Health Benefits Review Program estimates a savings of $42.8 million a year from fewer office visits and 15,000 fewer unintended pregnancies if their state enacts a similar policy.31

Pharmacist initiatives are worth watching. In January 2016, Oregon pharmacists with additional training were allowed to prescribe OCs and hormonal patches to women 18 years and older.32 In April 2016, a similar law went into effect in California, but without a minimum age requirement and with the additional coverage of vaginal rings and Depo-Provera (depo) injections.33 Pharmacists in both states must review a health questionnaire completed by the woman and can refer to a physician as necessary.

The CDC recommends that clinicians extend the allowed window for repeat depo injections to 15 weeks.14 Common institutional protocol is to give repeat injections every 11 to 13 weeks. If past that window, protocol often dictates the woman abstain from unprotected sex for 2 weeks and then return for a negative pregnancy test (or await menses) before the next injection. However, the CDC notes that depo is effective for longer than the 13-week period.14 No additional birth control or pregnancy testing is needed and the woman can receive the next depo shot if she is up to 15 weeks from the previous shot.

One study found no additional pregnancy risks for those who were up to 4 weeks “late” for their next shot, suggesting there is potential for an even larger grace period.34 The World Health Organization advises allowing a repeat injection up to 4 weeks late.35 We encourage institutions to change their policies to comply with the CDC’s 15-week window.

Another initiative is over-the-counter (OTC) access to OCs, which the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and ACOG support.36,37 ACOG notes that “no drug or intervention is completely without risk of harm” and that the risk of venous thromboembolism for OC users is lower than the risk of pregnancy.37 Women can successfully self-screen for contraindications using a checklist. Concerns about women potentially being less adherent or less likely to choose LARCs are not reasons to preclude access to other methods. The AAFP supports insurance coverage of OCs, regardless of prescription status.36

5. Routinely counsel about, and advance-prescribe, emergency contraception pills

Physicians should counsel and advance-prescribe emergency contraception pills (ECPs) to women, including adolescents, using less reliable contraception, as recommended by ACOG, AAP, and the CDC.14,37,38 It’s also important to provide information on the copper IUD as the most effective method of emergency contraception, with nearly 100% efficacy if placed within 5 days.39 An easy-to-read patient hand-out in English and Spanish on EC options can be found at http://beyondthepill.ucsf.edu/tools-materials.

Only 3% of respondents participating in the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth received counseling about emergency contraception in the past year.40 ECPs are most effective when used within 24 hours but have some efficacy up to 5 days.37 Due to the Affordable Care Act, most insurance plans will cover ECPs if purchased with a prescription, but coverage varies by state.41 Ulipristal acetate (UPA) ECP is only available with a prescription. Advance prescriptions can alleviate financial burdens on women when they need to access ECPs quickly.

Women should wait at least 5 days before resuming or starting hormonal contraception after taking UPA-based ECP, as it may reduce the ovulation-delaying effect of the ECP.14 For IUDs, implants, and depo, which require a visit to a health care provider, physicians evaluating earlier provision should consider the risks of reduced efficacy against the many barriers to access.

UPA-based ECPs (such as ella) may be more effective for overweight and obese women than levonorgestrel-based ECPs (such as Plan B and Next Choice).14 Consider advance-prescribing UPA ECPs to women with a body mass index (BMI) >25 kg/m2.42 Such considerations are important as the prevalence of obesity in women between 2013 and 2014 was 40.4%.43

In May 2016, the FDA noted that while current data are insufficient regarding whether the effectiveness of levonorgestrel ECPs is reduced in overweight or obese women, there are no safety concerns regarding their use in this population.44 Therefore, a woman with a BMI >25 kg/m2 should use UPA ECPs if available; but if not, she can still use levonorgestrel ECPs. One study, however, has found that UPA ECPs are only as effective as a placebo when BMI is ≥35 kg/m2, at which point a copper IUD may be the only effective form of emergency contraception.45

Transitioning from customary practices to best practices

Following these practical steps, FPs can improve contraceptive care for women. However, to make a significant impact, clinicians must be willing to change customary practices that are based on tradition, routines, or outdated protocols in favor of those based on current evidence.

One good place to start the transition to best practices is to familiarize yourself with the 2016 US Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use26 and Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use.14 TABLES 214,26,46,47 and 3 offer additional resources that can enhance contraceptive counseling and further promote access to contraceptive care.

The contraceptive coverage guarantee under the Affordable Care Act has allowed many women to make contraceptive choices based on personal needs and preferences rather than cost. The new contraceptive coverage exemptions issued under the Trump administration will bring cost back as the driving decision factor for women whose employers choose not to provide contraceptive coverage. Providers should be aware of the typical costs associated with the various contraceptive options offered in their practice and community.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jessica Dalby, MD, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1102 South Park St, Suite 100, Madison, WI 53715; Jessica.Dalby@fammed.wisc.edu.

1. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374:843-852.

2. Sonfield A, Hasstedt K, Gold RB. Moving Forward: Family Planning in the Era of Health Reform. New York: Guttmacher Institute. 2014. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/moving-forward-family-planning-era-health-reform. Accessed October 5, 2017.

3. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Reproductive Life Planning to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2016. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Reproductive-Life-Planning-to-Reduce-Unintended-Pregnancy. Accessed October 5, 2017.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive Life Plan Tool for Health Care Providers. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/preconception/rlptool.html. Accessed August 31, 2016.

5. Oregon Health Authority. Effective Contraceptive Use among Women at Risk of Unintended Pregnancy Guidance Document. 2014. Available at: http://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/ANALYTICS/CCOData/Effective%20Contraceptive%20Use%20Guidance%20Document.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

6. Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Steinberg JR, et al. “It just happens”: a qualitative study exploring low-income women’s perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception. 2015;91:150-156.

7. Yee LM, Farner KC, King E, et al. What do women want? Experiences of low-income women with postpartum contraception and contraceptive counseling. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2015;2.

8. Kalichman SC, Williams EA, Cherry C, et al. Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. J Womens Health. 1998;7:371-378.

9. ABIM Foundation. Pelvic Exams, Pap Tests and Oral Contraceptives. 2016. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/patient-resources/pelvic-exams-pap-tests-and-oral-contraceptives/. Accessed May 31, 2016.

10. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Access to Contraception: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2015. Number 615. Available at: https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=201710. Accessed October 5, 2017.

11. Bates CK, Carroll N, Potter J. The challenging pelvic examination. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:651-657.

12. Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Harris R, et al. Screening pelvic examination in adult women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:67-72.

13. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Cervical Cancer: Screening. 2012. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening. Accessed May 25, 2016.

14. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

15. Lesnewski R, Prine L. Initiating hormonal contraception. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:105-112.

16. Jacobsen BK, Knutsen SF, Oda K, et al. Obesity at age 20 and the risk of miscarriages, irregular periods and reported problems of becoming pregnant: the Adventist Health Study-2. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012; 27:923-931.

17. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Increasing Access to Contraceptive Implants and Intrauterine Devices to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2015. Number 642. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Increasing-Access-to-Contraceptive-Implants-and-Intrauterine-Devices-to-Reduce-Unintended-Pregnancy. Accessed October 5, 2017.

18. Harper CC, Henderson JT, Raine TR, et al. Evidence-based IUD practice: family physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists. Fam Med. 2012;44:637-645.

19. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence. Policy statement: Contraception for Adolescents. 2014. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2014/09/24/peds.2014-2299.full.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

20. Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancy: The Contraceptive CHOICE Project in review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:349-353.

21. Diedrich JT, Zhao Q, Madden T, et al. Three-year continuation of reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:662.e1-e8.

22. Lessard LN, Karasek D, Ma S, et al. Contraceptive features preferred by women at high risk of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44:194-200.

23. Nisen MB, Peterson LE, Cochrane A, et al. US family physicians’ intrauterine and implantable contraception provision: results from a national survey. Contraception. 2016;93:432-437.

24. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Bedsider. Available at: https://bedsider.org/. Accessed June 14, 2016.

25. Park HY, Rodriguez MI, Hulett D, et al. Long-acting reversible contraception method use among Title X providers and non-Title X providers in California. Contraception. 2012;86:557-561.

26. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

27. Westhoff C, Kerns J, Morroni C, et al. Quick start: novel oral contraceptive initiation method. Contraception. 2002;66:141-145.

28. Brahmi D, Curtis KM. When can a woman start combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs)? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:524-538.

29. Lachman S. Oregon To Require Insurers To Cover A Year’s Supply Of Birth Control. Huffington Post. June 11, 2015. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/11/oregon-birth-control-_n_7564712.html. Accessed October 16, 2017.

30. Andrews M. D.C. Women To Get Access To Full Year’s Worth Of Contraceptives. Kaiser Health News. September 25, 2015. Available at: https://khn.org/news/d-c-women-to-get-access-to-full-years-worth-of-contraceptives/. Accessed October 16, 2017.

31. Analysis of California Senate Bill (SB) 999 Contraceptives: Annual Supply: A Report to the 2015-2016 California State Legislature: California Health Benefits Review Program. 2016. Available at: http://chbrp.ucop.edu/index.php?action=read&bill_id=195&doc_type=1000. Accessed October 5, 2017.

32. Frazier A. Pharmacist-prescribed birth control in effect Jan 1. KOIN News. December 30, 2015. Available at: http://koin.com/2015/12/30/pharmacist-provided-birth-control-in-effect-jan-1/. Accessed October 5, 2017.

33. Karlamangla S. Birth control pills without prescriptions, coming soon to California under new law. Los Angeles Times. February 14, 2016. Available at: http://www.latimes.com/health/la-me-birth-control-pharmacies-20160214-story.html. Accessed October 16, 2017.

34. Steiner MJ, Kwok C, Stanback J, et al. Injectable contraception: what should the longest interval be for reinjections? Contraception. 2008;77:410-414.

35. World Health Organization. Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers. 2011. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44028/1/9780978856373_eng.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

36. American Academy of Family Physicians. Over-the-Counter Oral Contraceptives. 2014; Available at: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/otc-oral-contraceptives.html. Accessed June 2, 2016.

37. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Over-the-Counter Access to Oral Contraceptives: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2012. Number 544. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Over-the-Counter-Access-to-Oral-Contraceptives. Accessed October 5, 2017.

38. Committee on Adolescence. Emergency contraception. Pediatrics. 2012;130:1174-1182.

39. Cleland K, Zhu H, Goldstuck N, et al. The efficacy of intrauterine devices for emergency contraception: a systematic review of 35 years of experience. Hum Reprod. 2012;27:1994-2000.

40. Martinez G, Chandra A, Febo-Vazquez I, et al. Use of Family Planning and Related Medical Services Among Women Aged 15–44 in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006–2010: National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2013. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nhsr/nhsr068.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

41. Guttmacher Institute. Insurance Coverage of Contraceptives: Guttmacher Institute;2017. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy/explore/insurance-coverage-contraceptives Accessed October 7, 2017.

42. Glasier A, Cameron ST, Blithe D, et al. Can we identify women at risk of pregnancy despite using emergency contraception? Data from randomized trials of ulipristal acetate and levonorgestrel. Contraception. 2011;84:363-367.

43. Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA. 2016;315:2284-2291.

44. US Food & Drug Administration. Postmarket Drug Safety Information for Patients and Providers - Plan B (0.75mg levonorgestrel) and Plan B One-Step (1.5 mg levonorgestrel) Tablets Information. 2016; Available at: http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/ucm109775.htm. Accessed May 25, 2016.

45. Simmons KB, Edelman AB. Contraception and sexual health in obese women. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2015;29:466-478.

46. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Providing quality family planning services: recommendations of CDC and the U.S. Office of Population Affairs. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2014;63:1-29.

47. LARC FIRST. Available at: http://www.larcfirst.com/index.html. Accessed May 2016.

1. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med. 2016; 374:843-852.

2. Sonfield A, Hasstedt K, Gold RB. Moving Forward: Family Planning in the Era of Health Reform. New York: Guttmacher Institute. 2014. Available at: https://www.guttmacher.org/report/moving-forward-family-planning-era-health-reform. Accessed October 5, 2017.

3. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Reproductive Life Planning to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2016. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/Reproductive-Life-Planning-to-Reduce-Unintended-Pregnancy. Accessed October 5, 2017.

4. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reproductive Life Plan Tool for Health Care Providers. 2016. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/preconception/rlptool.html. Accessed August 31, 2016.

5. Oregon Health Authority. Effective Contraceptive Use among Women at Risk of Unintended Pregnancy Guidance Document. 2014. Available at: http://www.oregon.gov/oha/HPA/ANALYTICS/CCOData/Effective%20Contraceptive%20Use%20Guidance%20Document.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

6. Borrero S, Nikolajski C, Steinberg JR, et al. “It just happens”: a qualitative study exploring low-income women’s perspectives on pregnancy intention and planning. Contraception. 2015;91:150-156.

7. Yee LM, Farner KC, King E, et al. What do women want? Experiences of low-income women with postpartum contraception and contraceptive counseling. J Pregnancy Child Health. 2015;2.

8. Kalichman SC, Williams EA, Cherry C, et al. Sexual coercion, domestic violence, and negotiating condom use among low-income African American women. J Womens Health. 1998;7:371-378.

9. ABIM Foundation. Pelvic Exams, Pap Tests and Oral Contraceptives. 2016. Available at: http://www.choosingwisely.org/patient-resources/pelvic-exams-pap-tests-and-oral-contraceptives/. Accessed May 31, 2016.

10. Committee on Health Care for Underserved Women. Access to Contraception: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2015. Number 615. Available at: https://www.acog.org/-/media/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Health-Care-for-Underserved-Women/co615.pdf?dmc=1&ts=201710. Accessed October 5, 2017.

11. Bates CK, Carroll N, Potter J. The challenging pelvic examination. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:651-657.

12. Qaseem A, Humphrey LL, Harris R, et al. Screening pelvic examination in adult women: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:67-72.

13. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Cervical Cancer: Screening. 2012. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/cervical-cancer-screening. Accessed May 25, 2016.

14. Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-66.

15. Lesnewski R, Prine L. Initiating hormonal contraception. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74:105-112.

16. Jacobsen BK, Knutsen SF, Oda K, et al. Obesity at age 20 and the risk of miscarriages, irregular periods and reported problems of becoming pregnant: the Adventist Health Study-2. Eur J Epidemiol. 2012; 27:923-931.

17. Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Increasing Access to Contraceptive Implants and Intrauterine Devices to Reduce Unintended Pregnancy: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. 2015. Number 642. Available at: https://www.acog.org/Resources-And-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Gynecologic-Practice/Increasing-Access-to-Contraceptive-Implants-and-Intrauterine-Devices-to-Reduce-Unintended-Pregnancy. Accessed October 5, 2017.

18. Harper CC, Henderson JT, Raine TR, et al. Evidence-based IUD practice: family physicians and obstetrician-gynecologists. Fam Med. 2012;44:637-645.

19. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Adolescence. Policy statement: Contraception for Adolescents. 2014. Available at: http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/pediatrics/early/2014/09/24/peds.2014-2299.full.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

20. Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancy: The Contraceptive CHOICE Project in review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:349-353.

21. Diedrich JT, Zhao Q, Madden T, et al. Three-year continuation of reversible contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:662.e1-e8.

22. Lessard LN, Karasek D, Ma S, et al. Contraceptive features preferred by women at high risk of unintended pregnancy. Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2012;44:194-200.

23. Nisen MB, Peterson LE, Cochrane A, et al. US family physicians’ intrauterine and implantable contraception provision: results from a national survey. Contraception. 2016;93:432-437.

24. National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy. Bedsider. Available at: https://bedsider.org/. Accessed June 14, 2016.

25. Park HY, Rodriguez MI, Hulett D, et al. Long-acting reversible contraception method use among Title X providers and non-Title X providers in California. Contraception. 2012;86:557-561.

26. Curtis KM, Tepper NK, Jatlaoui TC, et al. U.S. medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-103.

27. Westhoff C, Kerns J, Morroni C, et al. Quick start: novel oral contraceptive initiation method. Contraception. 2002;66:141-145.

28. Brahmi D, Curtis KM. When can a woman start combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs)? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:524-538.

29. Lachman S. Oregon To Require Insurers To Cover A Year’s Supply Of Birth Control. Huffington Post. June 11, 2015. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2015/06/11/oregon-birth-control-_n_7564712.html. Accessed October 16, 2017.

30. Andrews M. D.C. Women To Get Access To Full Year’s Worth Of Contraceptives. Kaiser Health News. September 25, 2015. Available at: https://khn.org/news/d-c-women-to-get-access-to-full-years-worth-of-contraceptives/. Accessed October 16, 2017.

31. Analysis of California Senate Bill (SB) 999 Contraceptives: Annual Supply: A Report to the 2015-2016 California State Legislature: California Health Benefits Review Program. 2016. Available at: http://chbrp.ucop.edu/index.php?action=read&bill_id=195&doc_type=1000. Accessed October 5, 2017.

32. Frazier A. Pharmacist-prescribed birth control in effect Jan 1. KOIN News. December 30, 2015. Available at: http://koin.com/2015/12/30/pharmacist-provided-birth-control-in-effect-jan-1/. Accessed October 5, 2017.

33. Karlamangla S. Birth control pills without prescriptions, coming soon to California under new law. Los Angeles Times. February 14, 2016. Available at: http://www.latimes.com/health/la-me-birth-control-pharmacies-20160214-story.html. Accessed October 16, 2017.

34. Steiner MJ, Kwok C, Stanback J, et al. Injectable contraception: what should the longest interval be for reinjections? Contraception. 2008;77:410-414.

35. World Health Organization. Family Planning: A Global Handbook for Providers. 2011. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44028/1/9780978856373_eng.pdf. Accessed October 5, 2017.

36. American Academy of Family Physicians. Over-the-Counter Oral Contraceptives. 2014; Available at: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/otc-oral-contraceptives.html. Accessed June 2, 2016.