User login

Atypical Localized Scleroderma Development During Nivolumab Therapy for Metastatic Lung Adenocarcinoma

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

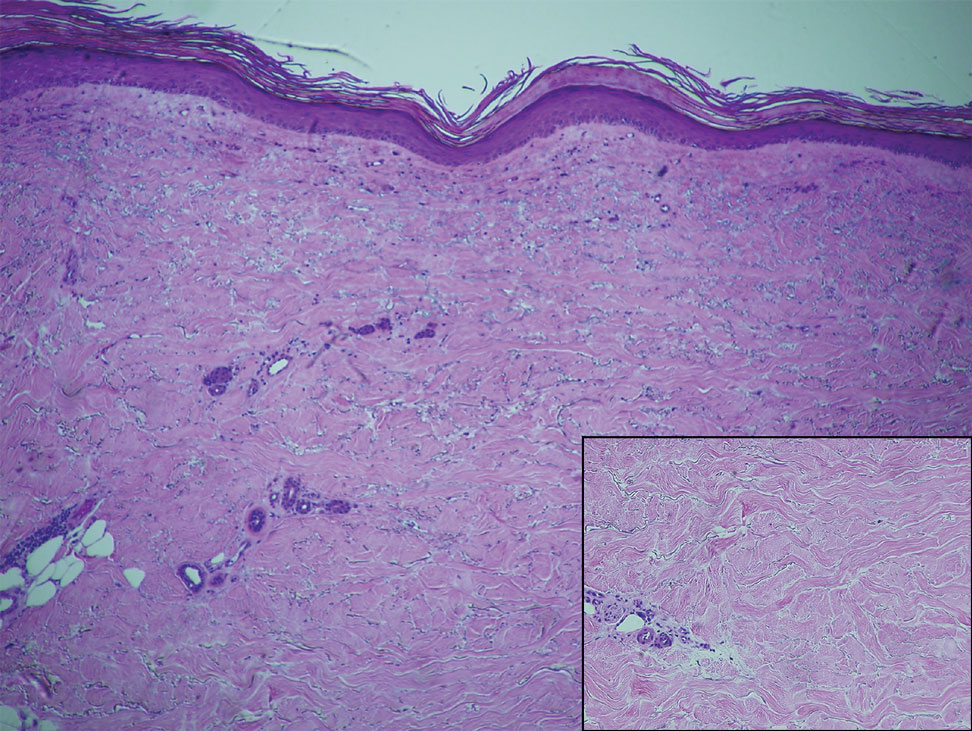

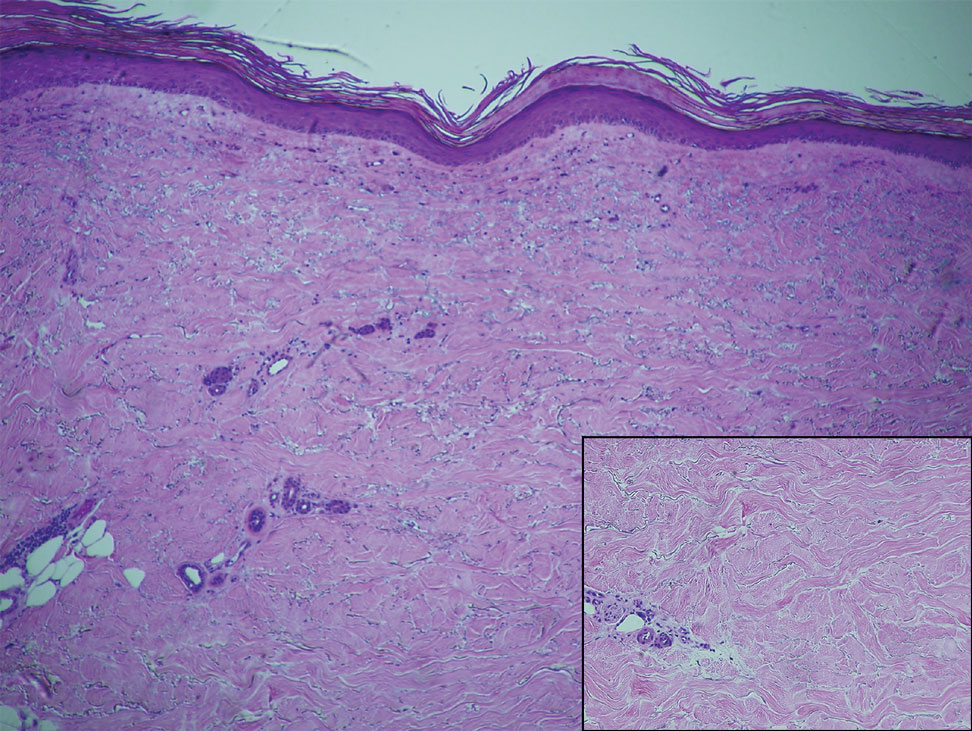

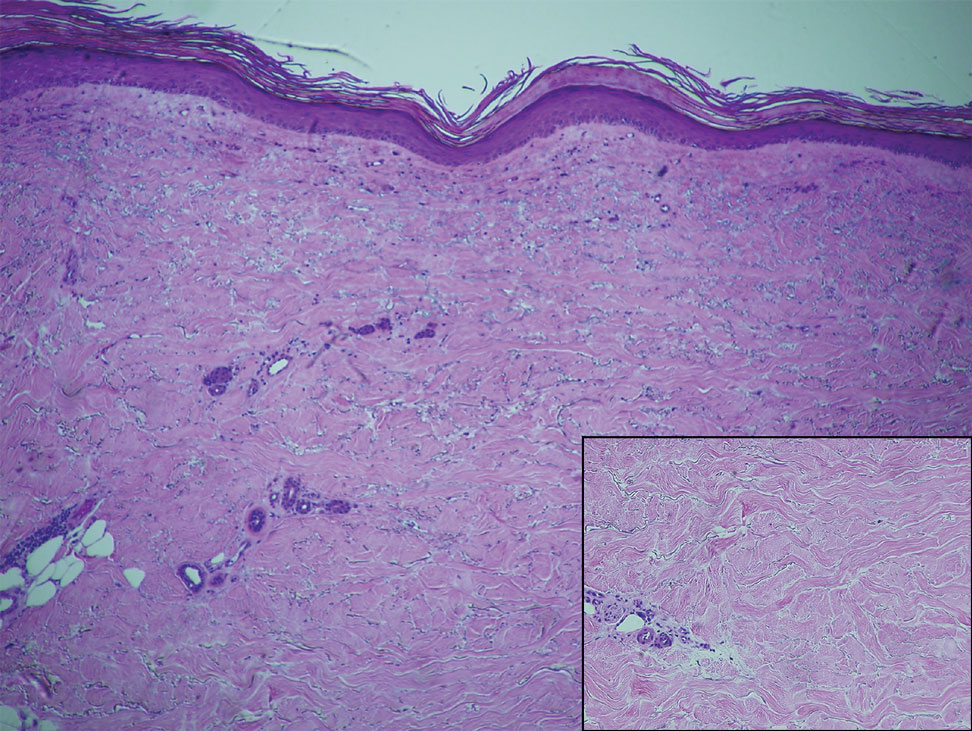

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

To the Editor:

Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as anti–programmed cell death protein 1 (anti–PD-1) and anticytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated protein 4 therapies are a promising class of cancer therapeutics. However, they are associated with a variety of immune-related adverse events (irAEs), including cutaneous toxicity.1 The PD-1/programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) pathway is important for the maintenance of immune tolerance, and a blockade has been shown to lead to development of various autoimmune diseases.2 We present the case of a patient who developed new-onset localized scleroderma during treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab.

A 65-year-old woman presented with a rash on the left thigh that was associated with pruritus, pain, and a pulling sensation. She had a history of stage IV lung adenocarcinoma, with a mass in the right upper lobe with metastatic foci to the left femur, right humerus, right hilar, and pretracheal lymph nodes. She received palliative radiation to the left femur and was started on carboplatin and pemetrexed. Metastasis to the liver was noted after completion of 6 cycles of therapy, and the patient’s treatment was changed to nivolumab. After 17 months on nivolumab therapy (2 years after initial diagnosis and 20 months after radiation therapy), she presented to our dermatology clinic with a cutaneous eruption on the buttocks that spread to the left thigh. The rash failed to improve after 1 month of treatment with emollients and triamcinolone cream 0.1%.

At the current presentation, which was 2 months after she initially presented to our clinic, dermatologic examination revealed erythematous and sclerotic plaques on the left lateral thigh (Figure 1A). Betamethasone cream 0.05% was prescribed, and nivolumab was discontinued due to progression of cutaneous symptoms. A punch biopsy from the left thigh demonstrated superficial dermal sclerosis that was suggestive of chronic radiation dermatitis; direct immunofluorescence testing was negative. The patient was started on prednisone 50 mg daily, which resulted in mild improvement in symptoms.

Within 6 months, new sclerotic plaques developed on the patient’s back and right thigh (Figure 1B). Because the lesions were located outside the radiation field of the left femur, a second biopsy was obtained from the right thigh. Histopathology revealed extensive dermal sclerosis and a perivascular lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate (Figure 2). An antinuclear antibody test was weakly positive (1:40, nucleolar pattern) with a negative extractable nuclear antigen panel result. Anti–double-stranded DNA, anti–topoisomerase 1, anti-Smith, antiribonucleoprotein, anti–Sjögren syndrome type A, anti–Sjögren syndrome type B, and anticentromere serology test results were negative. The patient denied decreased oral aperture, difficulty swallowing, or Raynaud phenomenon. Due to the atypical clinical presentation in the setting of PD-1 inhibitor therapy, the etiology of the eruption was potentially attributable to nivolumab. She was started on treatment with methotrexate 20 mg weekly and clobetasol cream 0.05% twice daily; she continued taking prednisone 5 mg daily. The cutaneous manifestations on the patient’s back completely resolved, and the legs continued to gradually improve on this regimen. Immunotherapy continued to be held due to skin toxicity.

Localized scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder characterized by inflammation and skin thickening. Overactive fibroblasts produce excess collagen, leading to the clinical symptoms of skin thickening, hardening, and discoloration.3 Lesions frequently develop on the arms, face, or legs and can present as patches or linear bands. Unlike systemic sclerosis, the internal organs typically are uninvolved; however, sclerotic lesions can be disfiguring and cause notable disability if they impede joint movement.

The PD-1/PD-L1 pathway is a negative regulator of the immune response that inactivates T cells and helps maintain self-tolerance. Modulation of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway and overexpression of PD-L1 are seen in various cancers as a mechanism to help malignant cells avoid immune destruction.4 Conversely, inhibition of this pathway can be used to stimulate an antitumor immune response. This checkpoint inhibition strategy has been highly successful for the treatment of various cancers including melanoma and non–small cell lung carcinoma. There are several checkpoint inhibitors approved in the United States that are used for cancer therapy and target the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway, such as nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.4 A downside of checkpoint inhibitor treatment is that uncontrolled T-cell activation can lead to irAEs, including cutaneous eruptions, pruritus, diarrhea, colitis, hepatitis, endocrinopathies, pneumonitis, and renal insufficiency.5 These toxicities are reversible if treated appropriately but can cause notable morbidity and mortality if left unrecognized. Cutaneous eruption is one of the most common irAEs associated with anti–PD-1 and anti–PD-L1 therapies and can limit therapeutic efficacy, as the drug may need to be held or discontinued due to the severity of the eruption.6 Mid-potency to high-potency topical corticosteroids and systemic antihistamines are first-line treatments of grades 1 and 2 skin toxicities associated with PD-1 inhibitor therapy. For eruptions classified as grades 3 or 4 or refractory grade 2, discontinuation of the drug and systemic corticosteroids is recommended.7

The cutaneous eruption in immunotherapy-mediated dermatitis is thought to be largely mediated by activated T cells infiltrating the dermis.8 In localized scleroderma, increased tumor necrosis factor α, IFN-γ, IFN-γ–induced protein 10, and granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor activity have been shown to correlate with disease activity.9,10 Interestingly, increased tumor necrosis factor α and IFN-γ correlate with better response and increased overall survival in PD-1 inhibition therapy, suggesting a correlation between PD-1 inhibition and T helper activation as noted by the etiology of sclerosis in our patient.11 Additionally, history of radiation was a confounding factor in the diagnosis of our patient, as both sclerodermoid reactions and chronic radiation dermatitis can present with dermal sclerosis. However, the progression of disease outside of the radiation field excluded this etiology. Although new-onset sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, they have been described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions from treatment with pembrolizumab.12,13 One case series reported a case of diffuse sclerodermoid reaction and a limited reaction in response to pembrolizumab treatment, while another case report described a relapse of generalized morphea in response to pembrolizumab treatment.12,13 One case of relapsing morphea in response to nivolumab treatment for stage IV lung adenocarcinoma also has been reported.14

Cutaneous toxicities are one of the most common irAEs associated with checkpoint inhibitors and are seen in more than one-third of treated patients. Most frequently, these irAEs manifest as spongiotic dermatitis on histopathology, but a broad spectrum of cutaneous reactions have been observed.15 Although sclerodermoid reactions have been reported with PD-1 inhibitors, most are described secondary to sclerodermoid reactions with pembrolizumab and involve relapse of previously diagnosed morphea rather than new-onset disease.12-14

Our case highlights new-onset localized scleroderma in the setting of nivolumab therapy that showed clinical improvement with methotrexate and topical and systemic steroids. This reaction pattern should be considered in all patients who develop cutaneous eruptions when treated with a PD-1 inhibitor. There should be a high index of suspicion for the potential occurrence of irAEs to ensure early recognition and treatment to minimize morbidity and maximize adherence to therapy for the underlying malignancy.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

- Baxi S, Yang A, Gennarelli RL, et al. Immune-related adverse events for anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 drugs: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2018;360:k793.

- Dai S, Jia R, Zhang X, et al. The PD-1/PD-Ls pathway and autoimmune diseases. Cell Immunol. 2014;290:72-79.

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, et al. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009;48:213-221.

- Constantinidou A, Alifieris C, Trafalis DT. Targeting programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) and ligand (PD-L1): a new era in cancer active immunotherapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2019;194:84-106.

- Villadolid J, Asim A. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in clinical practice: update on management of immune-related toxicities. Transl Lung Cancer Res. 2015;4:560-575.

- Naidoo J, Page DB, Li BT, et al. Toxicities of the anti-PD-1 and anti-PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:1362.

- O’Kane GM, Labbé C, Doherty MK, et al. Monitoring and management of immune-related adverse events associated with programmed cell death protein-1 axis inhibitors in lung cancer. Oncologist. 2017;22:70-80.

- Shi VJ, Rodic N, Gettinger S, et al. Clinical and histologic features of lichenoid mucocutaneous eruptions due to anti-programmed celldeath 1 and anti-programmed cell death ligand 1 immunotherapy. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:1128-1136.

- Torok KS, Kurzinski K, Kelsey C, et al. Peripheral blood cytokine and chemokine profiles in juvenile localized scleroderma: T-helper cell-associated cytokine profiles. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45:284-293.

- Guo X, Higgs BW, Bay-Jensen AC, et al. Suppression of T cell activation and collagen accumulation by an anti-IFNAR1 mAb, anifrolumab, in adult patients with systemic sclerosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2402-2409.

- Boutsikou E, Domvri K, Hardavella G, et al. Tumor necrosis factor, interferon-gamma and interleukins as predictive markers of antiprogrammed cell-death protein-1 treatment in advanced non-small cell lung cancer: a pragmatic approach in clinical practice. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2018;10:1758835918768238.

- Barbosa NS, Wetter DA, Wieland CN, et al. Scleroderma induced by pembrolizumab: a case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1158-1163.

- Cheng MW, Hisaw LD, Bernet L. Generalized morphea in the setting of pembrolizumab. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:736-738.

- Alegre-Sánchez A, Fonda-Pascual P, Saceda-Corralo D, et al. Relapse of morphea during nivolumab therapy for lung adenocarcinoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:69-70.

- Sibaud V. Dermatologic reactions to immune checkpoint inhibitors: skin toxicities and immunotherapy. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:345-361.

Practice Points

- Immune checkpoint inhibitors such as nivolumab, a programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) inhibitor, are associated with immune-related adverse events (irAEs) such as skin toxicity.

- Scleroderma should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients who develop cutaneous eruptions during treatment with PD-1 inhibitors.

- To ensure prompt recognition and treatment, health care providers should maintain a high index of suspicion for development of cutaneous irAEs in patients using checkpoint inhibitors.

Facial Malignancies in Patients Referred for Mohs Micrographic Surgery: A Retrospective Review of the Impact of Hair Growth on Tumor and Defect Size

Male facial hair trends are continuously changing and are influenced by culture, geography, religion, and ethnicity.1 Although the natural pattern of these hairs is largely androgen dependent, the phenotypic presentation often is a result of contemporary grooming practices that reflect prevailing trends.2 Beards are common throughout adulthood, and thus, preserving this facial hair pattern is considered with reconstructive techniques.3,4 Male facial skin physiology and beard hair biology are a dynamic interplay between both internal (eg, hormonal) and external (eg, shaving) variables. The density of beard hair follicles varies within different subunits, ranging between 20 and 80 follicles/cm2. Macroscopically, hairs vary in length, diameter, color, and growth rate across individuals and ethnicities.1,5

There is a paucity of literature assessing if male facial hair offers a protective role for external insults. One study utilized dosimetry to examine the effectiveness of facial hair on mannequins with varying lengths of hair in protecting against erythemal UV radiation (UVR). The authors concluded that, although facial hair provides protection from UVR, it is not significant.6 In a study of 200 male patients with

We sought to determine if facial hair growth is implicated in the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous malignancies. Specifically, we hypothesized that the presence of facial hair leads to a delay in diagnosis with increased subclinical growth given that tumors may be camouflaged and go undetected. Although there is a lack of literature, our anecdotal evidence suggests that male patients with facial hair have larger tumors compared to patients who do not regularly maintain any facial hair.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review following approval from the institutional review board at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We identified all male patients with a cutaneous malignancy located on the face who were treated from January 2015 to December 2018. Photographs were reviewed and patients with tumors located within the following facial hair-bearing anatomic subunits were included: lip, melolabial fold, chin, mandible, preauricular cheek, buccal cheek, and parotid-masseteric cheek. Tumors located within the medial cheek were excluded.

Facial hair growth was determined via image review. Because biopsy photographs were not uploaded into the health record for patients who were referred externally, we reviewed all historical photographs for patients who had undergone prior Mohs micrographic surgery at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, preoperative photographs, and follow-up photographs as a proxy to determine facial hair status. Postoperative photographs taken within 2 weeks following surgery were not reviewed, as any facial hair growth was likely due to disinclination on behalf of the patient to shave near or over the incision. Age, number of days from biopsy to surgery, pathology, preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs layers, and defect size also were extrapolated from our chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were applied to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. An unpaired 2-tailed t test was utilized to test the null hypothesis that the mean difference was zero. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Results achieving P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We reviewed medical records for 171 patients with facial hair and 336 patients without facial hair. The primary outcomes for this study assessed tumor and defect size in patients with facial hair compared to patients with no facial hair (Table 1). On average, patients who had facial hair were younger (67.5 years vs 74.0 years, P<.001). The median number of days from biopsy to surgery (43.0 vs 44.0 days) was comparable across both groups. The majority of patients (47%) exhibited a beard, while 30% had a mustache and 23% had a goatee. The most common tumor location was the preauricular cheek for both groups (29% and 28%, respectively). The mean preoperative tumor size in the facial hair cohort was 1.40 cm compared to 1.22 cm in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The mean number of Mohs layers in the facial hair cohort was 1.53 compared to 1.33 in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The facial hair cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (2.18 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.98 cm); however, this finding was not significant (P=.05).

We then stratified our data to analyze only lip tumors in patients with and without a mustache (Table 2). The mean preoperative tumor size in the mustache cohort was 1.10 cm compared to 0.82 cm in the group with no mustaches (P=.046). The mean number of Mohs layers in the mustache cohort was 1.57 compared to 1.42 in the group with no mustaches (P=.43). The mustache cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (1.63 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.33 cm), though this finding also did not reach significance (P=.13).

Comment

Our findings support anecdotal observations that tumors in men with facial hair are larger, require more Mohs layers, and result in larger defects compared with patients who are clean shaven. Similarly, in lip tumors, men with a mustache had a larger preoperative tumor size. Although these patients also required more Mohs layers to clear and a larger defect size, these parameters did not reach significance. These outcomes may, in part, be explained by a delay in diagnosis, as patients with facial hair may not notice any new suspicious lesions within the underlying skin as easily as patients with glabrous skin.

Although facial hair may shield skin from UVR, we agree with Parisi et al6 that this protection is marginal at best and that early persistent exposure to UVR plays a much more notable role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. As more men continue to grow facial hairstyles that emulate historical or contemporary trends, dermatologists should emphasize the risk for cutaneous malignancies within these sun-exposed areas of the face. Although some facial hair practices may reflect cultural or ethnic settings, the majority reflect a desired appearance that is achieved with grooming or otherwise.

Skin cancer screening in men with facial hair, particularly those with a strong history of UVR exposure and/or family history, should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose cutaneous tumors earlier. We encourage men with facial hair to be cognizant that cutaneous malignancies can arise within hair-bearing skin and to incorporate self–skin checks into grooming routines, which is particularly important in men with dense facial hair who forego regular self-care grooming or trim intermittently. Furthermore, we urge dermatologists to continue to thoroughly examine the underlying skin, especially in patients with full beards, during skin examinations. Diagnosing and treating cutaneous malignancies early is imperative to maximize ideal functional and cosmetic outcomes, particularly within perioral and lip subunits, where marginal millimeters can impact reconstructive complexity.

Conclusion

Men with facial hair who had cutaneous tumors in our study exhibited larger tumors, required more Mohs layers, and had a larger defect size compared to men without any facial hair growth. Similar findings also were noted when we stratified and compared lip tumors in patients with and without mustaches. Given these observations, patients and dermatologists should continue to have a high index of suspicion for any concerning lesion located within skin underlying facial hair. Regular screening in men with facial hair should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose and treat potential cutaneous tumors earlier.

- Wu Y, Konduru R, Deng D. Skin characteristics of Chinese men and their beard removal habits. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:17-21.

- Janif ZJ, Brooks RC, Dixson BJ. Negative frequency-dependent preferences and variation in male facial hair. Biol Lett. 2014;10:20130958.

- Benjegerdes KE, Jamerson J, Housewright CD. Repair of a large submental defect. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:141-143.

- Ninkovic M, Heidekruegger PI, Ehri D, et al. Beard reconstruction: a surgical algorithm. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:E111-E118.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin–challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(suppl 1):3-9.

- Parisi AV, Turnbull DJ, Downs N, et al. Dosimetric investigation of the solar erythemal UV radiation protection provided by beards and moustaches. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2012;150:278-282.

- Liu DY, Gul MI, Wick J, et al. Long-term sheltering mustaches reduce incidence of lower lip actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1757-1758.e1.

Male facial hair trends are continuously changing and are influenced by culture, geography, religion, and ethnicity.1 Although the natural pattern of these hairs is largely androgen dependent, the phenotypic presentation often is a result of contemporary grooming practices that reflect prevailing trends.2 Beards are common throughout adulthood, and thus, preserving this facial hair pattern is considered with reconstructive techniques.3,4 Male facial skin physiology and beard hair biology are a dynamic interplay between both internal (eg, hormonal) and external (eg, shaving) variables. The density of beard hair follicles varies within different subunits, ranging between 20 and 80 follicles/cm2. Macroscopically, hairs vary in length, diameter, color, and growth rate across individuals and ethnicities.1,5

There is a paucity of literature assessing if male facial hair offers a protective role for external insults. One study utilized dosimetry to examine the effectiveness of facial hair on mannequins with varying lengths of hair in protecting against erythemal UV radiation (UVR). The authors concluded that, although facial hair provides protection from UVR, it is not significant.6 In a study of 200 male patients with

We sought to determine if facial hair growth is implicated in the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous malignancies. Specifically, we hypothesized that the presence of facial hair leads to a delay in diagnosis with increased subclinical growth given that tumors may be camouflaged and go undetected. Although there is a lack of literature, our anecdotal evidence suggests that male patients with facial hair have larger tumors compared to patients who do not regularly maintain any facial hair.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review following approval from the institutional review board at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We identified all male patients with a cutaneous malignancy located on the face who were treated from January 2015 to December 2018. Photographs were reviewed and patients with tumors located within the following facial hair-bearing anatomic subunits were included: lip, melolabial fold, chin, mandible, preauricular cheek, buccal cheek, and parotid-masseteric cheek. Tumors located within the medial cheek were excluded.

Facial hair growth was determined via image review. Because biopsy photographs were not uploaded into the health record for patients who were referred externally, we reviewed all historical photographs for patients who had undergone prior Mohs micrographic surgery at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, preoperative photographs, and follow-up photographs as a proxy to determine facial hair status. Postoperative photographs taken within 2 weeks following surgery were not reviewed, as any facial hair growth was likely due to disinclination on behalf of the patient to shave near or over the incision. Age, number of days from biopsy to surgery, pathology, preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs layers, and defect size also were extrapolated from our chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were applied to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. An unpaired 2-tailed t test was utilized to test the null hypothesis that the mean difference was zero. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Results achieving P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We reviewed medical records for 171 patients with facial hair and 336 patients without facial hair. The primary outcomes for this study assessed tumor and defect size in patients with facial hair compared to patients with no facial hair (Table 1). On average, patients who had facial hair were younger (67.5 years vs 74.0 years, P<.001). The median number of days from biopsy to surgery (43.0 vs 44.0 days) was comparable across both groups. The majority of patients (47%) exhibited a beard, while 30% had a mustache and 23% had a goatee. The most common tumor location was the preauricular cheek for both groups (29% and 28%, respectively). The mean preoperative tumor size in the facial hair cohort was 1.40 cm compared to 1.22 cm in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The mean number of Mohs layers in the facial hair cohort was 1.53 compared to 1.33 in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The facial hair cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (2.18 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.98 cm); however, this finding was not significant (P=.05).

We then stratified our data to analyze only lip tumors in patients with and without a mustache (Table 2). The mean preoperative tumor size in the mustache cohort was 1.10 cm compared to 0.82 cm in the group with no mustaches (P=.046). The mean number of Mohs layers in the mustache cohort was 1.57 compared to 1.42 in the group with no mustaches (P=.43). The mustache cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (1.63 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.33 cm), though this finding also did not reach significance (P=.13).

Comment

Our findings support anecdotal observations that tumors in men with facial hair are larger, require more Mohs layers, and result in larger defects compared with patients who are clean shaven. Similarly, in lip tumors, men with a mustache had a larger preoperative tumor size. Although these patients also required more Mohs layers to clear and a larger defect size, these parameters did not reach significance. These outcomes may, in part, be explained by a delay in diagnosis, as patients with facial hair may not notice any new suspicious lesions within the underlying skin as easily as patients with glabrous skin.

Although facial hair may shield skin from UVR, we agree with Parisi et al6 that this protection is marginal at best and that early persistent exposure to UVR plays a much more notable role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. As more men continue to grow facial hairstyles that emulate historical or contemporary trends, dermatologists should emphasize the risk for cutaneous malignancies within these sun-exposed areas of the face. Although some facial hair practices may reflect cultural or ethnic settings, the majority reflect a desired appearance that is achieved with grooming or otherwise.

Skin cancer screening in men with facial hair, particularly those with a strong history of UVR exposure and/or family history, should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose cutaneous tumors earlier. We encourage men with facial hair to be cognizant that cutaneous malignancies can arise within hair-bearing skin and to incorporate self–skin checks into grooming routines, which is particularly important in men with dense facial hair who forego regular self-care grooming or trim intermittently. Furthermore, we urge dermatologists to continue to thoroughly examine the underlying skin, especially in patients with full beards, during skin examinations. Diagnosing and treating cutaneous malignancies early is imperative to maximize ideal functional and cosmetic outcomes, particularly within perioral and lip subunits, where marginal millimeters can impact reconstructive complexity.

Conclusion

Men with facial hair who had cutaneous tumors in our study exhibited larger tumors, required more Mohs layers, and had a larger defect size compared to men without any facial hair growth. Similar findings also were noted when we stratified and compared lip tumors in patients with and without mustaches. Given these observations, patients and dermatologists should continue to have a high index of suspicion for any concerning lesion located within skin underlying facial hair. Regular screening in men with facial hair should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose and treat potential cutaneous tumors earlier.

Male facial hair trends are continuously changing and are influenced by culture, geography, religion, and ethnicity.1 Although the natural pattern of these hairs is largely androgen dependent, the phenotypic presentation often is a result of contemporary grooming practices that reflect prevailing trends.2 Beards are common throughout adulthood, and thus, preserving this facial hair pattern is considered with reconstructive techniques.3,4 Male facial skin physiology and beard hair biology are a dynamic interplay between both internal (eg, hormonal) and external (eg, shaving) variables. The density of beard hair follicles varies within different subunits, ranging between 20 and 80 follicles/cm2. Macroscopically, hairs vary in length, diameter, color, and growth rate across individuals and ethnicities.1,5

There is a paucity of literature assessing if male facial hair offers a protective role for external insults. One study utilized dosimetry to examine the effectiveness of facial hair on mannequins with varying lengths of hair in protecting against erythemal UV radiation (UVR). The authors concluded that, although facial hair provides protection from UVR, it is not significant.6 In a study of 200 male patients with

We sought to determine if facial hair growth is implicated in the diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous malignancies. Specifically, we hypothesized that the presence of facial hair leads to a delay in diagnosis with increased subclinical growth given that tumors may be camouflaged and go undetected. Although there is a lack of literature, our anecdotal evidence suggests that male patients with facial hair have larger tumors compared to patients who do not regularly maintain any facial hair.

Methods

We performed a retrospective chart review following approval from the institutional review board at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. We identified all male patients with a cutaneous malignancy located on the face who were treated from January 2015 to December 2018. Photographs were reviewed and patients with tumors located within the following facial hair-bearing anatomic subunits were included: lip, melolabial fold, chin, mandible, preauricular cheek, buccal cheek, and parotid-masseteric cheek. Tumors located within the medial cheek were excluded.

Facial hair growth was determined via image review. Because biopsy photographs were not uploaded into the health record for patients who were referred externally, we reviewed all historical photographs for patients who had undergone prior Mohs micrographic surgery at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, preoperative photographs, and follow-up photographs as a proxy to determine facial hair status. Postoperative photographs taken within 2 weeks following surgery were not reviewed, as any facial hair growth was likely due to disinclination on behalf of the patient to shave near or over the incision. Age, number of days from biopsy to surgery, pathology, preoperative tumor size, number of Mohs layers, and defect size also were extrapolated from our chart review.

Statistical Analysis

Summary statistics were applied to describe demographic and clinical characteristics. An unpaired 2-tailed t test was utilized to test the null hypothesis that the mean difference was zero. The χ2 test was used for categorical variables. Results achieving P<.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

We reviewed medical records for 171 patients with facial hair and 336 patients without facial hair. The primary outcomes for this study assessed tumor and defect size in patients with facial hair compared to patients with no facial hair (Table 1). On average, patients who had facial hair were younger (67.5 years vs 74.0 years, P<.001). The median number of days from biopsy to surgery (43.0 vs 44.0 days) was comparable across both groups. The majority of patients (47%) exhibited a beard, while 30% had a mustache and 23% had a goatee. The most common tumor location was the preauricular cheek for both groups (29% and 28%, respectively). The mean preoperative tumor size in the facial hair cohort was 1.40 cm compared to 1.22 cm in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The mean number of Mohs layers in the facial hair cohort was 1.53 compared to 1.33 in the group with no facial hair (P=.03). The facial hair cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (2.18 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.98 cm); however, this finding was not significant (P=.05).

We then stratified our data to analyze only lip tumors in patients with and without a mustache (Table 2). The mean preoperative tumor size in the mustache cohort was 1.10 cm compared to 0.82 cm in the group with no mustaches (P=.046). The mean number of Mohs layers in the mustache cohort was 1.57 compared to 1.42 in the group with no mustaches (P=.43). The mustache cohort also had a larger mean postoperative defect size (1.63 cm) compared to the group with no facial hair (1.33 cm), though this finding also did not reach significance (P=.13).

Comment

Our findings support anecdotal observations that tumors in men with facial hair are larger, require more Mohs layers, and result in larger defects compared with patients who are clean shaven. Similarly, in lip tumors, men with a mustache had a larger preoperative tumor size. Although these patients also required more Mohs layers to clear and a larger defect size, these parameters did not reach significance. These outcomes may, in part, be explained by a delay in diagnosis, as patients with facial hair may not notice any new suspicious lesions within the underlying skin as easily as patients with glabrous skin.

Although facial hair may shield skin from UVR, we agree with Parisi et al6 that this protection is marginal at best and that early persistent exposure to UVR plays a much more notable role in cutaneous carcinogenesis. As more men continue to grow facial hairstyles that emulate historical or contemporary trends, dermatologists should emphasize the risk for cutaneous malignancies within these sun-exposed areas of the face. Although some facial hair practices may reflect cultural or ethnic settings, the majority reflect a desired appearance that is achieved with grooming or otherwise.

Skin cancer screening in men with facial hair, particularly those with a strong history of UVR exposure and/or family history, should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose cutaneous tumors earlier. We encourage men with facial hair to be cognizant that cutaneous malignancies can arise within hair-bearing skin and to incorporate self–skin checks into grooming routines, which is particularly important in men with dense facial hair who forego regular self-care grooming or trim intermittently. Furthermore, we urge dermatologists to continue to thoroughly examine the underlying skin, especially in patients with full beards, during skin examinations. Diagnosing and treating cutaneous malignancies early is imperative to maximize ideal functional and cosmetic outcomes, particularly within perioral and lip subunits, where marginal millimeters can impact reconstructive complexity.

Conclusion

Men with facial hair who had cutaneous tumors in our study exhibited larger tumors, required more Mohs layers, and had a larger defect size compared to men without any facial hair growth. Similar findings also were noted when we stratified and compared lip tumors in patients with and without mustaches. Given these observations, patients and dermatologists should continue to have a high index of suspicion for any concerning lesion located within skin underlying facial hair. Regular screening in men with facial hair should be discussed and encouraged to diagnose and treat potential cutaneous tumors earlier.

- Wu Y, Konduru R, Deng D. Skin characteristics of Chinese men and their beard removal habits. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:17-21.

- Janif ZJ, Brooks RC, Dixson BJ. Negative frequency-dependent preferences and variation in male facial hair. Biol Lett. 2014;10:20130958.

- Benjegerdes KE, Jamerson J, Housewright CD. Repair of a large submental defect. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:141-143.

- Ninkovic M, Heidekruegger PI, Ehri D, et al. Beard reconstruction: a surgical algorithm. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:E111-E118.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin–challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(suppl 1):3-9.

- Parisi AV, Turnbull DJ, Downs N, et al. Dosimetric investigation of the solar erythemal UV radiation protection provided by beards and moustaches. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2012;150:278-282.

- Liu DY, Gul MI, Wick J, et al. Long-term sheltering mustaches reduce incidence of lower lip actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1757-1758.e1.

- Wu Y, Konduru R, Deng D. Skin characteristics of Chinese men and their beard removal habits. Br J Dermatol. 2012;166:17-21.

- Janif ZJ, Brooks RC, Dixson BJ. Negative frequency-dependent preferences and variation in male facial hair. Biol Lett. 2014;10:20130958.

- Benjegerdes KE, Jamerson J, Housewright CD. Repair of a large submental defect. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:141-143.

- Ninkovic M, Heidekruegger PI, Ehri D, et al. Beard reconstruction: a surgical algorithm. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2016;69:E111-E118.

- Maurer M, Rietzler M, Burghardt R, et al. The male beard hair and facial skin–challenges for shaving. Int J Cosmet Sci. 2016;38(suppl 1):3-9.

- Parisi AV, Turnbull DJ, Downs N, et al. Dosimetric investigation of the solar erythemal UV radiation protection provided by beards and moustaches. Radiat Prot Dosimetry. 2012;150:278-282.

- Liu DY, Gul MI, Wick J, et al. Long-term sheltering mustaches reduce incidence of lower lip actinic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1757-1758.e1.

Practice Points

- In our study, men with cutaneous tumors who had facial hair exhibited larger tumors, required more Mohs layers, and had a larger defect size compared to men who do not have any facial hair growth.

- Both patients and dermatologists should have a high index of suspicion for any concerning lesion contained within skin underlying facial hair to ensure prompt diagnosis and treatment of cutaneous tumors.