User login

Two skin problems related or not?

HISTORY

A 36-year-old man self-refers to dermatology with two complaints. The more serious is the very itchy rash present on his back for several weeks. He has tried treating it with several OTC creams, including 1% hydrocortisone, triple-antibiotic, and diphenhydramine. The hydrocortisone cream provided some short-term relief from the itching, but over time, the rash has grown and become more symptomatic.

The condition affecting his feet has caused little in the way of symptoms. However, it has caused quite a stir in the family; every night, on returning from work, the patient removes his shoes, releasing a pervasive, highly objectionable odor. It didn’t take long for his family to insist that he remove his shoes in the backyard, where he is to remain until the odor clears a bit. The patient is also concerned about a “spongy” feeling the soles of his feet have acquired along with the odor. Neither symptom has responded to topical OTC products, such as athlete’s foot cream (tonaftate) and spray or calamine lotion; lengthy soaks in bleach-containing water have not helped, either.

The patient claims to be in reasonably good health. He is working in a new job, repairing air conditioners on the roofs of commercial buildings.

EXAMINATION

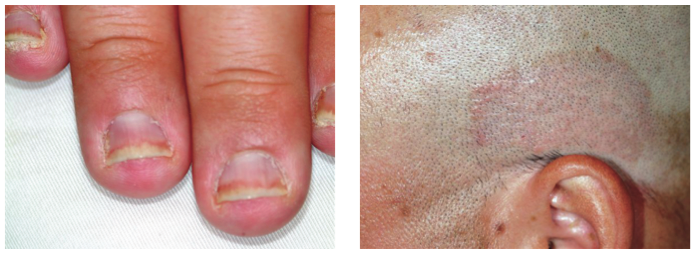

An impressive rash is seen on the patient’s upper back, extending from the hairline to mid-back, with a long, curved papulosquamous border on its inferior aspect. Aside from the soles of his feet, the only other skin abnormality is a faintly erythematous rash around the rims of both feet. KOH examination reveals these patches to be loaded with fungal elements.

Both soles have a spongy, whitish look, with focal areas of punctuate crateriform and arciform superficial loss of the outer keratin layer of skin. But there is no erythema or no tenderness on palpation.

DISCUSSION

Daily exposure to constant sweat and heat is responsible for all of this man’s skin problems, although there are two different conditions involved. Tinea corporis is the explanation for the extensive rash on his upper back. However, the repeated application of topical steroids is the likely explanation for the astonishing size and scope of the rash, since steroids (even 1% hydrocortisone!) blunt the body’s immune response to this superficial dermatophytosis. As is often the case, this outbreak was so large it was hard to see. Heat and sweat might be the immediate cause, but what about the source?

The fungal organisms on the rims of his feet, probably present asymptomatically (and unrecognized) for years, provide a clue to the patient’s susceptibility to this class of organisms. Trichophyton rubrum is by far the most common cause; given enough heat, sweat, and steroids, it can easily spread to other areas of the body.

Now to the feet, where antifungal cream (tolnaftate) and bleach had no good effect: The name given to this common condition is pitted keratolysis (PK). PK is caused by several bacterial organisms that thrive in this hot, humid environment, feeding on the keratin layer and producing the pattern seen. The most common bacteria involved is Kytococcus sedentarius, but all are part of normal gram-positive flora and are also responsible for the powerful odor noted in many—though not all—cases. Since the organism feeds on lifeless keratin and causes no inflammatory response or symptoms, PK is not really an “infection” in the sense that we normally use this word.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

PK is successfully treated with a combination of topically applied antiperspirant (such as prescription-strength aluminum chloride, or OTC antiperspirant with aluminum chorhydroxide) and topical clindamycin 2% solution. Though an endpoint is unlikely with these treatments, control is possible.

The same could be said for the steroid-exacerbated tinea corporis on the patient’s back, since the conditions that lead to its appearance will still be present. Given the severity and symptomatic nature of this eruption, I gave the patient oral terbinafine (250 mg bid for 10 days) plus topical econazole cream (bid until the rash is clear). For maintenance, he’ll use OTC ketoconazole shampoo as a body wash, to reduce the numbers of these organisms.

During the winter, both of these conditions will abate sharply, only to reappear when the weather heats up in the spring. Patient education is necessary as to this aspect of both conditions, including their prognoses.

For the provider, this case highlights, once again, the difficulty that dermatologic complaints present. PK, for example, looks very much as though it should “have a name,” but neither its name nor its origins nor remedies will be clear if the requisite time has not been spent learning about it in advance of its inevitable sighting.

HISTORY

A 36-year-old man self-refers to dermatology with two complaints. The more serious is the very itchy rash present on his back for several weeks. He has tried treating it with several OTC creams, including 1% hydrocortisone, triple-antibiotic, and diphenhydramine. The hydrocortisone cream provided some short-term relief from the itching, but over time, the rash has grown and become more symptomatic.

The condition affecting his feet has caused little in the way of symptoms. However, it has caused quite a stir in the family; every night, on returning from work, the patient removes his shoes, releasing a pervasive, highly objectionable odor. It didn’t take long for his family to insist that he remove his shoes in the backyard, where he is to remain until the odor clears a bit. The patient is also concerned about a “spongy” feeling the soles of his feet have acquired along with the odor. Neither symptom has responded to topical OTC products, such as athlete’s foot cream (tonaftate) and spray or calamine lotion; lengthy soaks in bleach-containing water have not helped, either.

The patient claims to be in reasonably good health. He is working in a new job, repairing air conditioners on the roofs of commercial buildings.

EXAMINATION

An impressive rash is seen on the patient’s upper back, extending from the hairline to mid-back, with a long, curved papulosquamous border on its inferior aspect. Aside from the soles of his feet, the only other skin abnormality is a faintly erythematous rash around the rims of both feet. KOH examination reveals these patches to be loaded with fungal elements.

Both soles have a spongy, whitish look, with focal areas of punctuate crateriform and arciform superficial loss of the outer keratin layer of skin. But there is no erythema or no tenderness on palpation.

DISCUSSION

Daily exposure to constant sweat and heat is responsible for all of this man’s skin problems, although there are two different conditions involved. Tinea corporis is the explanation for the extensive rash on his upper back. However, the repeated application of topical steroids is the likely explanation for the astonishing size and scope of the rash, since steroids (even 1% hydrocortisone!) blunt the body’s immune response to this superficial dermatophytosis. As is often the case, this outbreak was so large it was hard to see. Heat and sweat might be the immediate cause, but what about the source?

The fungal organisms on the rims of his feet, probably present asymptomatically (and unrecognized) for years, provide a clue to the patient’s susceptibility to this class of organisms. Trichophyton rubrum is by far the most common cause; given enough heat, sweat, and steroids, it can easily spread to other areas of the body.

Now to the feet, where antifungal cream (tolnaftate) and bleach had no good effect: The name given to this common condition is pitted keratolysis (PK). PK is caused by several bacterial organisms that thrive in this hot, humid environment, feeding on the keratin layer and producing the pattern seen. The most common bacteria involved is Kytococcus sedentarius, but all are part of normal gram-positive flora and are also responsible for the powerful odor noted in many—though not all—cases. Since the organism feeds on lifeless keratin and causes no inflammatory response or symptoms, PK is not really an “infection” in the sense that we normally use this word.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

PK is successfully treated with a combination of topically applied antiperspirant (such as prescription-strength aluminum chloride, or OTC antiperspirant with aluminum chorhydroxide) and topical clindamycin 2% solution. Though an endpoint is unlikely with these treatments, control is possible.

The same could be said for the steroid-exacerbated tinea corporis on the patient’s back, since the conditions that lead to its appearance will still be present. Given the severity and symptomatic nature of this eruption, I gave the patient oral terbinafine (250 mg bid for 10 days) plus topical econazole cream (bid until the rash is clear). For maintenance, he’ll use OTC ketoconazole shampoo as a body wash, to reduce the numbers of these organisms.

During the winter, both of these conditions will abate sharply, only to reappear when the weather heats up in the spring. Patient education is necessary as to this aspect of both conditions, including their prognoses.

For the provider, this case highlights, once again, the difficulty that dermatologic complaints present. PK, for example, looks very much as though it should “have a name,” but neither its name nor its origins nor remedies will be clear if the requisite time has not been spent learning about it in advance of its inevitable sighting.

HISTORY

A 36-year-old man self-refers to dermatology with two complaints. The more serious is the very itchy rash present on his back for several weeks. He has tried treating it with several OTC creams, including 1% hydrocortisone, triple-antibiotic, and diphenhydramine. The hydrocortisone cream provided some short-term relief from the itching, but over time, the rash has grown and become more symptomatic.

The condition affecting his feet has caused little in the way of symptoms. However, it has caused quite a stir in the family; every night, on returning from work, the patient removes his shoes, releasing a pervasive, highly objectionable odor. It didn’t take long for his family to insist that he remove his shoes in the backyard, where he is to remain until the odor clears a bit. The patient is also concerned about a “spongy” feeling the soles of his feet have acquired along with the odor. Neither symptom has responded to topical OTC products, such as athlete’s foot cream (tonaftate) and spray or calamine lotion; lengthy soaks in bleach-containing water have not helped, either.

The patient claims to be in reasonably good health. He is working in a new job, repairing air conditioners on the roofs of commercial buildings.

EXAMINATION

An impressive rash is seen on the patient’s upper back, extending from the hairline to mid-back, with a long, curved papulosquamous border on its inferior aspect. Aside from the soles of his feet, the only other skin abnormality is a faintly erythematous rash around the rims of both feet. KOH examination reveals these patches to be loaded with fungal elements.

Both soles have a spongy, whitish look, with focal areas of punctuate crateriform and arciform superficial loss of the outer keratin layer of skin. But there is no erythema or no tenderness on palpation.

DISCUSSION

Daily exposure to constant sweat and heat is responsible for all of this man’s skin problems, although there are two different conditions involved. Tinea corporis is the explanation for the extensive rash on his upper back. However, the repeated application of topical steroids is the likely explanation for the astonishing size and scope of the rash, since steroids (even 1% hydrocortisone!) blunt the body’s immune response to this superficial dermatophytosis. As is often the case, this outbreak was so large it was hard to see. Heat and sweat might be the immediate cause, but what about the source?

The fungal organisms on the rims of his feet, probably present asymptomatically (and unrecognized) for years, provide a clue to the patient’s susceptibility to this class of organisms. Trichophyton rubrum is by far the most common cause; given enough heat, sweat, and steroids, it can easily spread to other areas of the body.

Now to the feet, where antifungal cream (tolnaftate) and bleach had no good effect: The name given to this common condition is pitted keratolysis (PK). PK is caused by several bacterial organisms that thrive in this hot, humid environment, feeding on the keratin layer and producing the pattern seen. The most common bacteria involved is Kytococcus sedentarius, but all are part of normal gram-positive flora and are also responsible for the powerful odor noted in many—though not all—cases. Since the organism feeds on lifeless keratin and causes no inflammatory response or symptoms, PK is not really an “infection” in the sense that we normally use this word.

TREATMENT AND PROGNOSIS

PK is successfully treated with a combination of topically applied antiperspirant (such as prescription-strength aluminum chloride, or OTC antiperspirant with aluminum chorhydroxide) and topical clindamycin 2% solution. Though an endpoint is unlikely with these treatments, control is possible.

The same could be said for the steroid-exacerbated tinea corporis on the patient’s back, since the conditions that lead to its appearance will still be present. Given the severity and symptomatic nature of this eruption, I gave the patient oral terbinafine (250 mg bid for 10 days) plus topical econazole cream (bid until the rash is clear). For maintenance, he’ll use OTC ketoconazole shampoo as a body wash, to reduce the numbers of these organisms.

During the winter, both of these conditions will abate sharply, only to reappear when the weather heats up in the spring. Patient education is necessary as to this aspect of both conditions, including their prognoses.

For the provider, this case highlights, once again, the difficulty that dermatologic complaints present. PK, for example, looks very much as though it should “have a name,” but neither its name nor its origins nor remedies will be clear if the requisite time has not been spent learning about it in advance of its inevitable sighting.

Ear lesion suspicious for melanoma?

Family members bring in an 80-year-old man for urgent evaluation of a number of skin lesions. Most alarming to them is the lesion on his right ear, although many others, including numerous dark lesions on his back, have also raised their concern. The patient and his wife are “positive” all the lesions have been present, unchanged, for years.

EXAMINATION

Your attention is quickly drawn to the superior helical area of the patient’s right ear, where a large, irregularly pigmented and bordered black patch covers most of the superior helix. The surrounding skin is quite fair and sun-damaged, with extensive solar elastosis seen all across the patient’s face—especially on the forehead, where multiple actinic keratoses are also seen and felt.

Hundreds of dark brown–to-black warty epidermal papules, nodules, and plaques are observed on the patient’s trunk; some are as large as 6 cm, while most average 2 to 3 cm. Fortunately, no other worrisome lesions are seen, except for the right superior helical lesion, which appears exceptionally suspicious for melanoma.

A tray is set up for the performance of a 3-mm punch biopsy of the ear lesion. Prior to that procedure, direct examination of the lesion is carried out with a dermatoscope, a magnifying (10x power) handheld viewing device that illuminates the site with flat, polarized light. It can be used to look for specific features of benign versus malignant lesions. After the entire lesion’s surface has been examined, the biopsy is cancelled and the family reassured regarding the benignancy of the ear lesion.

DISCUSSION

One reason for the dermatoscopic examination was the size of the ear lesion; it was so large that the chance of sampling error became a definite concern. A single 3-mm punch biopsy taken from a 4-cm lesion, if negative for cancer, could simply have missed the malignancy. However, removal of the entire lesion was not at all practical. Multiple punch biopsies from several areas within the lesion would have been an acceptable, but clumsy, alternative.

Thankfully, the dermatoscopic examination results obviated the need for invasive alternatives. Here’s why: Seen with the dermatoscope, over the entire surface of the lesion, were white pinpoint spots at regular intervals, called pseudocysts. These indentations are filled with keratin and are pathognomic for the diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK). Moreover, no organized collections of pigment (streaks, globules, or networks) were seen; these might have suggested melanoma. The presence of so many other SKs elsewhere lent credence to that same diagnosis on the ear.

Even though SKs are often seen in non–sun-exposed areas, there is evidence to suggest that ultraviolet exposure can play a part in their genesis. Heredity and age are arguably more significant factors; SKs are seldom seen before the fourth decade of life.

SKs have little if any malignant potential, but they have been known to coincide with sun-caused skin cancers, such as basal or squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma, with one adjacent to or even overlying the other. And while the lesions of SK are typically raised and warty (epidermal or “stuck on”), they can appear quite flat and smooth at times, in addition to occasionally being darker than SKs are “supposed to be,” increasing their resemblance to a melanoma.

Biopsy of an SK shows diagnostic features of variable papillomatosis, as well as comedone-like openings, fissures, and keratin-filled pseudocysts. The differential for SKs includes wart, melanoma, and solar lentigo.

No treatment was attempted for this helical SK. However, the patient will be monitored during twice-yearly follow-up visits to dermatology, not only for changes to his ear lesion but also for changes anywhere else on his skin.

LEARNING POINTS

• Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is the most common example of a benign epidermal (“stuck-on”) lesion.

• That “stuck-on” nature is what usually distinguishes SK from melanoma.

• However, some SKs are almost completely flat and occasionally totally black—and therefore difficult to distinguish from melanoma, especially in sebum-rich skin.

• Biopsy is often necessary, but dermatoscopic examination (in trained hands) is a useful noninvasive procedure that can obviate the need for biopsy.

Family members bring in an 80-year-old man for urgent evaluation of a number of skin lesions. Most alarming to them is the lesion on his right ear, although many others, including numerous dark lesions on his back, have also raised their concern. The patient and his wife are “positive” all the lesions have been present, unchanged, for years.

EXAMINATION

Your attention is quickly drawn to the superior helical area of the patient’s right ear, where a large, irregularly pigmented and bordered black patch covers most of the superior helix. The surrounding skin is quite fair and sun-damaged, with extensive solar elastosis seen all across the patient’s face—especially on the forehead, where multiple actinic keratoses are also seen and felt.

Hundreds of dark brown–to-black warty epidermal papules, nodules, and plaques are observed on the patient’s trunk; some are as large as 6 cm, while most average 2 to 3 cm. Fortunately, no other worrisome lesions are seen, except for the right superior helical lesion, which appears exceptionally suspicious for melanoma.

A tray is set up for the performance of a 3-mm punch biopsy of the ear lesion. Prior to that procedure, direct examination of the lesion is carried out with a dermatoscope, a magnifying (10x power) handheld viewing device that illuminates the site with flat, polarized light. It can be used to look for specific features of benign versus malignant lesions. After the entire lesion’s surface has been examined, the biopsy is cancelled and the family reassured regarding the benignancy of the ear lesion.

DISCUSSION

One reason for the dermatoscopic examination was the size of the ear lesion; it was so large that the chance of sampling error became a definite concern. A single 3-mm punch biopsy taken from a 4-cm lesion, if negative for cancer, could simply have missed the malignancy. However, removal of the entire lesion was not at all practical. Multiple punch biopsies from several areas within the lesion would have been an acceptable, but clumsy, alternative.

Thankfully, the dermatoscopic examination results obviated the need for invasive alternatives. Here’s why: Seen with the dermatoscope, over the entire surface of the lesion, were white pinpoint spots at regular intervals, called pseudocysts. These indentations are filled with keratin and are pathognomic for the diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK). Moreover, no organized collections of pigment (streaks, globules, or networks) were seen; these might have suggested melanoma. The presence of so many other SKs elsewhere lent credence to that same diagnosis on the ear.

Even though SKs are often seen in non–sun-exposed areas, there is evidence to suggest that ultraviolet exposure can play a part in their genesis. Heredity and age are arguably more significant factors; SKs are seldom seen before the fourth decade of life.

SKs have little if any malignant potential, but they have been known to coincide with sun-caused skin cancers, such as basal or squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma, with one adjacent to or even overlying the other. And while the lesions of SK are typically raised and warty (epidermal or “stuck on”), they can appear quite flat and smooth at times, in addition to occasionally being darker than SKs are “supposed to be,” increasing their resemblance to a melanoma.

Biopsy of an SK shows diagnostic features of variable papillomatosis, as well as comedone-like openings, fissures, and keratin-filled pseudocysts. The differential for SKs includes wart, melanoma, and solar lentigo.

No treatment was attempted for this helical SK. However, the patient will be monitored during twice-yearly follow-up visits to dermatology, not only for changes to his ear lesion but also for changes anywhere else on his skin.

LEARNING POINTS

• Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is the most common example of a benign epidermal (“stuck-on”) lesion.

• That “stuck-on” nature is what usually distinguishes SK from melanoma.

• However, some SKs are almost completely flat and occasionally totally black—and therefore difficult to distinguish from melanoma, especially in sebum-rich skin.

• Biopsy is often necessary, but dermatoscopic examination (in trained hands) is a useful noninvasive procedure that can obviate the need for biopsy.

Family members bring in an 80-year-old man for urgent evaluation of a number of skin lesions. Most alarming to them is the lesion on his right ear, although many others, including numerous dark lesions on his back, have also raised their concern. The patient and his wife are “positive” all the lesions have been present, unchanged, for years.

EXAMINATION

Your attention is quickly drawn to the superior helical area of the patient’s right ear, where a large, irregularly pigmented and bordered black patch covers most of the superior helix. The surrounding skin is quite fair and sun-damaged, with extensive solar elastosis seen all across the patient’s face—especially on the forehead, where multiple actinic keratoses are also seen and felt.

Hundreds of dark brown–to-black warty epidermal papules, nodules, and plaques are observed on the patient’s trunk; some are as large as 6 cm, while most average 2 to 3 cm. Fortunately, no other worrisome lesions are seen, except for the right superior helical lesion, which appears exceptionally suspicious for melanoma.

A tray is set up for the performance of a 3-mm punch biopsy of the ear lesion. Prior to that procedure, direct examination of the lesion is carried out with a dermatoscope, a magnifying (10x power) handheld viewing device that illuminates the site with flat, polarized light. It can be used to look for specific features of benign versus malignant lesions. After the entire lesion’s surface has been examined, the biopsy is cancelled and the family reassured regarding the benignancy of the ear lesion.

DISCUSSION

One reason for the dermatoscopic examination was the size of the ear lesion; it was so large that the chance of sampling error became a definite concern. A single 3-mm punch biopsy taken from a 4-cm lesion, if negative for cancer, could simply have missed the malignancy. However, removal of the entire lesion was not at all practical. Multiple punch biopsies from several areas within the lesion would have been an acceptable, but clumsy, alternative.

Thankfully, the dermatoscopic examination results obviated the need for invasive alternatives. Here’s why: Seen with the dermatoscope, over the entire surface of the lesion, were white pinpoint spots at regular intervals, called pseudocysts. These indentations are filled with keratin and are pathognomic for the diagnosis of seborrheic keratosis (SK). Moreover, no organized collections of pigment (streaks, globules, or networks) were seen; these might have suggested melanoma. The presence of so many other SKs elsewhere lent credence to that same diagnosis on the ear.

Even though SKs are often seen in non–sun-exposed areas, there is evidence to suggest that ultraviolet exposure can play a part in their genesis. Heredity and age are arguably more significant factors; SKs are seldom seen before the fourth decade of life.

SKs have little if any malignant potential, but they have been known to coincide with sun-caused skin cancers, such as basal or squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma, with one adjacent to or even overlying the other. And while the lesions of SK are typically raised and warty (epidermal or “stuck on”), they can appear quite flat and smooth at times, in addition to occasionally being darker than SKs are “supposed to be,” increasing their resemblance to a melanoma.

Biopsy of an SK shows diagnostic features of variable papillomatosis, as well as comedone-like openings, fissures, and keratin-filled pseudocysts. The differential for SKs includes wart, melanoma, and solar lentigo.

No treatment was attempted for this helical SK. However, the patient will be monitored during twice-yearly follow-up visits to dermatology, not only for changes to his ear lesion but also for changes anywhere else on his skin.

LEARNING POINTS

• Seborrheic keratosis (SK) is the most common example of a benign epidermal (“stuck-on”) lesion.

• That “stuck-on” nature is what usually distinguishes SK from melanoma.

• However, some SKs are almost completely flat and occasionally totally black—and therefore difficult to distinguish from melanoma, especially in sebum-rich skin.

• Biopsy is often necessary, but dermatoscopic examination (in trained hands) is a useful noninvasive procedure that can obviate the need for biopsy.

Recurrent "rash" on eyelid cause for concern?

With her family’s encouragement, this 17-year-old girl self-refers to dermatology for a recurrent facial lesion. It has reappeared in the same location and in the same manner over the past 18 months; they suspect it is a staph infection.

First, the patient experiences localized itching and tingling in the same location on her left upper eyelid. Within a day or two, clusters of tiny blisters appear and the surrounding skin becomes erythematous. Ten days or so into the episode, the blisters begin to scab over and the redness subsides. Within two weeks, the condition totally resolves, only to reappear later.

Each time, she has been seen in an urgent care clinic, given a diagnosis of staph infection, and prescribed a 10-day course of trimethoprim/sulfa, which appears to clear the infection.

DIAGNOSIS/DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates the curious nature of extragenital/extralabial herpes simplex virus (HSV), which can manifest in virtually any location on the body. We can all agree that HSV far more commonly affects the lip, where a lesion such as this one would be readily recognized. But the diagnosis becomes problematic when the same blisters appear in an unfamiliar location.

Assumptions are made, often fueled by family fears, themselves fed by opinions from other well-meaning friends and acquaintances. And in such cases, treatment with antibiotics certainly appears to corroborate the diagnosis because it “works.” But the family’s nagging question of “Why?” is reasonable, and the answer telling.

The truth is, it would be quite out of the ordinary for a staph infection to present with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base, over and over again in the same location. It would also be unlike staph to merely tingle and itch, since pain and tenderness are far more typical.

If we really wanted to rule out staph infection, we would have to obtain a culture, which would not only provide an organism but also solid information about which antibiotics are likely to be effective against that particular organism. Had that been done in this case, the culture would have shown “no growth,” leaving us where we started, since a routine culture only identifies bacteria. A viral culture, taken from the vesicular fluid, would probably have proven the culprit to be herpes—but that possibility would first have to be entertained.

Had herpes been considered as a diagnosis, other corroboratory historical facts might have included the patient’s history of severe atopy, plus the fact that most of the episodes occurred during periods of increased stress. Both of these factors are well known to predispose patients to a number of skin infections—most notably, HSV. The premonitory symptoms of tingle and itch (and sometimes a bit of pain) were also instructive.

It also helps simply to know that such HSV infections are quite common (though often, as in this case, misdiagnosed). I’ve seen HSV in the scalp, on the ear, on the chest, on fingers, toes, thighs, and on the bottom of the foot. I’ve also seen it affect the eye itself, where it can cause scarring of the cornea. Fortunately, our patient had no symptoms referable to the eye. Had that been the case, referral to ophthalmology on an urgent basis would have been necessary.

Had this condition occurred only once, other items in the differential might have been considered: contact dermatitis and the blistering diseases (pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid, and others). But the recurrent nature was all but pathognomic.

TREATMENT

For this patient, there was no effective treatment for the current episode, since the acyclovir family of antivirals can only slow viral replication, which had already taken place. But I did provide a prescription for valcyclovir 500-mg capsules, dispensing 10. The patient was advised to take them twice a day for five days, starting at the earliest signs of her next episode, which should halt the progression. If the patient has more than six or eight eruptions a year, a case could be made for prophylactic medication to be taken daily.

Ultimately, the most valuable thing provided to this patient was the answer to the questions: What is this, and why does it affect me? Two good questions remain unanswered: How did she get HSV in that exact location? And how can we cure her? With a little luck, in the reader’s career, we’ll come up with a cure, just as science came up with the acyclovir family of medicines early in my career.

LEARNING POINTS

• Grouped vesicles on an erythematous base, recurring in the same location, are HSV until proven otherwise.

• HSV episodes typically last 10 to 14 days.

• Staph infections are typically painful, and rarely recur in the same locations.

• Atopy predisposes to extralabial HSV.

• There are many causes of inflammation, only one of which is infection.

• There are many types of infection that are not bacterial (eg, viral, fungal, protozoan).

With her family’s encouragement, this 17-year-old girl self-refers to dermatology for a recurrent facial lesion. It has reappeared in the same location and in the same manner over the past 18 months; they suspect it is a staph infection.

First, the patient experiences localized itching and tingling in the same location on her left upper eyelid. Within a day or two, clusters of tiny blisters appear and the surrounding skin becomes erythematous. Ten days or so into the episode, the blisters begin to scab over and the redness subsides. Within two weeks, the condition totally resolves, only to reappear later.

Each time, she has been seen in an urgent care clinic, given a diagnosis of staph infection, and prescribed a 10-day course of trimethoprim/sulfa, which appears to clear the infection.

DIAGNOSIS/DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates the curious nature of extragenital/extralabial herpes simplex virus (HSV), which can manifest in virtually any location on the body. We can all agree that HSV far more commonly affects the lip, where a lesion such as this one would be readily recognized. But the diagnosis becomes problematic when the same blisters appear in an unfamiliar location.

Assumptions are made, often fueled by family fears, themselves fed by opinions from other well-meaning friends and acquaintances. And in such cases, treatment with antibiotics certainly appears to corroborate the diagnosis because it “works.” But the family’s nagging question of “Why?” is reasonable, and the answer telling.

The truth is, it would be quite out of the ordinary for a staph infection to present with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base, over and over again in the same location. It would also be unlike staph to merely tingle and itch, since pain and tenderness are far more typical.

If we really wanted to rule out staph infection, we would have to obtain a culture, which would not only provide an organism but also solid information about which antibiotics are likely to be effective against that particular organism. Had that been done in this case, the culture would have shown “no growth,” leaving us where we started, since a routine culture only identifies bacteria. A viral culture, taken from the vesicular fluid, would probably have proven the culprit to be herpes—but that possibility would first have to be entertained.

Had herpes been considered as a diagnosis, other corroboratory historical facts might have included the patient’s history of severe atopy, plus the fact that most of the episodes occurred during periods of increased stress. Both of these factors are well known to predispose patients to a number of skin infections—most notably, HSV. The premonitory symptoms of tingle and itch (and sometimes a bit of pain) were also instructive.

It also helps simply to know that such HSV infections are quite common (though often, as in this case, misdiagnosed). I’ve seen HSV in the scalp, on the ear, on the chest, on fingers, toes, thighs, and on the bottom of the foot. I’ve also seen it affect the eye itself, where it can cause scarring of the cornea. Fortunately, our patient had no symptoms referable to the eye. Had that been the case, referral to ophthalmology on an urgent basis would have been necessary.

Had this condition occurred only once, other items in the differential might have been considered: contact dermatitis and the blistering diseases (pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid, and others). But the recurrent nature was all but pathognomic.

TREATMENT

For this patient, there was no effective treatment for the current episode, since the acyclovir family of antivirals can only slow viral replication, which had already taken place. But I did provide a prescription for valcyclovir 500-mg capsules, dispensing 10. The patient was advised to take them twice a day for five days, starting at the earliest signs of her next episode, which should halt the progression. If the patient has more than six or eight eruptions a year, a case could be made for prophylactic medication to be taken daily.

Ultimately, the most valuable thing provided to this patient was the answer to the questions: What is this, and why does it affect me? Two good questions remain unanswered: How did she get HSV in that exact location? And how can we cure her? With a little luck, in the reader’s career, we’ll come up with a cure, just as science came up with the acyclovir family of medicines early in my career.

LEARNING POINTS

• Grouped vesicles on an erythematous base, recurring in the same location, are HSV until proven otherwise.

• HSV episodes typically last 10 to 14 days.

• Staph infections are typically painful, and rarely recur in the same locations.

• Atopy predisposes to extralabial HSV.

• There are many causes of inflammation, only one of which is infection.

• There are many types of infection that are not bacterial (eg, viral, fungal, protozoan).

With her family’s encouragement, this 17-year-old girl self-refers to dermatology for a recurrent facial lesion. It has reappeared in the same location and in the same manner over the past 18 months; they suspect it is a staph infection.

First, the patient experiences localized itching and tingling in the same location on her left upper eyelid. Within a day or two, clusters of tiny blisters appear and the surrounding skin becomes erythematous. Ten days or so into the episode, the blisters begin to scab over and the redness subsides. Within two weeks, the condition totally resolves, only to reappear later.

Each time, she has been seen in an urgent care clinic, given a diagnosis of staph infection, and prescribed a 10-day course of trimethoprim/sulfa, which appears to clear the infection.

DIAGNOSIS/DISCUSSION

This case nicely illustrates the curious nature of extragenital/extralabial herpes simplex virus (HSV), which can manifest in virtually any location on the body. We can all agree that HSV far more commonly affects the lip, where a lesion such as this one would be readily recognized. But the diagnosis becomes problematic when the same blisters appear in an unfamiliar location.

Assumptions are made, often fueled by family fears, themselves fed by opinions from other well-meaning friends and acquaintances. And in such cases, treatment with antibiotics certainly appears to corroborate the diagnosis because it “works.” But the family’s nagging question of “Why?” is reasonable, and the answer telling.

The truth is, it would be quite out of the ordinary for a staph infection to present with grouped vesicles on an erythematous base, over and over again in the same location. It would also be unlike staph to merely tingle and itch, since pain and tenderness are far more typical.

If we really wanted to rule out staph infection, we would have to obtain a culture, which would not only provide an organism but also solid information about which antibiotics are likely to be effective against that particular organism. Had that been done in this case, the culture would have shown “no growth,” leaving us where we started, since a routine culture only identifies bacteria. A viral culture, taken from the vesicular fluid, would probably have proven the culprit to be herpes—but that possibility would first have to be entertained.

Had herpes been considered as a diagnosis, other corroboratory historical facts might have included the patient’s history of severe atopy, plus the fact that most of the episodes occurred during periods of increased stress. Both of these factors are well known to predispose patients to a number of skin infections—most notably, HSV. The premonitory symptoms of tingle and itch (and sometimes a bit of pain) were also instructive.

It also helps simply to know that such HSV infections are quite common (though often, as in this case, misdiagnosed). I’ve seen HSV in the scalp, on the ear, on the chest, on fingers, toes, thighs, and on the bottom of the foot. I’ve also seen it affect the eye itself, where it can cause scarring of the cornea. Fortunately, our patient had no symptoms referable to the eye. Had that been the case, referral to ophthalmology on an urgent basis would have been necessary.

Had this condition occurred only once, other items in the differential might have been considered: contact dermatitis and the blistering diseases (pemphigus, bullous pemphigoid, and others). But the recurrent nature was all but pathognomic.

TREATMENT

For this patient, there was no effective treatment for the current episode, since the acyclovir family of antivirals can only slow viral replication, which had already taken place. But I did provide a prescription for valcyclovir 500-mg capsules, dispensing 10. The patient was advised to take them twice a day for five days, starting at the earliest signs of her next episode, which should halt the progression. If the patient has more than six or eight eruptions a year, a case could be made for prophylactic medication to be taken daily.

Ultimately, the most valuable thing provided to this patient was the answer to the questions: What is this, and why does it affect me? Two good questions remain unanswered: How did she get HSV in that exact location? And how can we cure her? With a little luck, in the reader’s career, we’ll come up with a cure, just as science came up with the acyclovir family of medicines early in my career.

LEARNING POINTS

• Grouped vesicles on an erythematous base, recurring in the same location, are HSV until proven otherwise.

• HSV episodes typically last 10 to 14 days.

• Staph infections are typically painful, and rarely recur in the same locations.

• Atopy predisposes to extralabial HSV.

• There are many causes of inflammation, only one of which is infection.

• There are many types of infection that are not bacterial (eg, viral, fungal, protozoan).

Recurrent pigment loss worries patient

HISTORY

Pigment loss is no joke, especially when it appears annually in the same locations. Although it eventually clears up, this 30-year-old-woman has been worried about her condition ever since her (no doubt, well-meaning) sister-in-law suggested it might be vitiligo.

The patient had no idea what vitiligo was but soon found out when she looked it up. To add to that angst, she has been seen by any number of providers over the years and has been given about as many different diagnoses, including the ever-popular “ringworm,” psoriasis, and mere dry skin.

The patient knows she has always had exceptionally dry skin, as well as seasonal allergies. These are problems almost everyone on her mother’s side of the family has had (as well as the patient’s two siblings).

The patient’s pigment loss seems to peak in the summer, resolving almost completely by Christmas.

DISCUSSION

In general, change in pigment is called dyschromia, but when one adds or loses the normal color of the skin, it’s called either hyperchromia or hypochromia. The distinction is not merely academic, since dyschromic patients can turn a variety of colors: blue (with ingestion of silver salts or minocycline, for example), bronze (seen with Wilson’s and Addison’s diseases and hemochromatosis), brown (as in melasma), or gray (seen with administration of gold salts).

One unusual form of hypochromia is vitiligo, an autoimmune disease eventuating in sharply demarcated areas of complete pigment loss, leaving perfectly white skin in its wake. Vitiligo seldom, if ever, waxes and wanes and never involves associated scaling. But it can certainly be a cosmetic problem, often affecting the face, hands, arms, and legs.

Vitilgo can be treated with varying degrees of success, depending on how early the treatment is instituted and how aggressive the disease is. Quite often, it progresses unnoticed until it has become permanent.

Fortunately, our patient did not have vitiligo and instead had the extremely common pityriasis alba (PA). Osler, the most famous physician of his time (1900), once quipped that he could ”forgive dermatology its complexity, but never its terminology.” Pityriasis alba (PA) sounds imposing. But in fact, it represents a simple but important concept: As cutaneous inflammation subsides, the epidermis can add pigment (called postinflammatory hyperpigmentation) or lose it (postinflammatory hypopigmentation).

PA manifests with patchy partial pigment loss as a postinflammatory consequence of antecedent eczema. The latter, originating most commonly in winter, is almost always part of an overarching diagnosis of atopic dermatitis, minor diagnostic criteria for which also include dry, sensitive skin, seasonal allergies, and asthma (all inherited traits).

The usual progression is thus: Patients with xerosis (dry skin), which is worsened by the low humidity of winter and the appeal of long, hot showers, begin to develop faintly defined, round, slightly scaly patches of eczema on the sides of the face and on the arms. These are so faint that they are often missed by the patient and family until later, in the spring, when the postinflammatory loss of pigment is made more obvious by tanning of the surrounding skin. As one might expect, this is especially obvious in darker-skinned patients whose eczema has long since faded, leaving an exceedingly fine scale (if any).

When the eczema is especially active and inflamed, the annular shape and scaly surface put the inexperienced provider in mind of “ringworm” (tinea corporis). This can be ruled out with a KOH prep and brief history-taking to identify whether a potential source for fungal organisms (new pet, playmates, siblings) exists. Keep in mind that pityriasis alba is far more common than tinea corporis.

The differential diagnosis for patchy hypopigmentation also includes tinea versicolor and (in older patients) cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which would be progressive (albeit slowly) and not seasonal. The organism responsible for tinea versicolor (the commensal yeast Malassezia furfur) needs, among other things, much sebum in order to thrive. As this is an ingredient missing in prepubescent children, it is an important point in ruling out tinea versicolor, which is almost always seasonal as well, in young patients.

On a practical level, the “treatment” of PA predominantly involves easing patients’ (and parents’) minds by giving them a firm diagnosis that does not involve “ringworm,” and a clear idea of the self-limiting nature of the problem. See below for other treatment ideas.

LEARNING POINTS

Pityriasis alba (PA) favors the sides of the face and triceps areas of both arms; it is especially common in darker-skinned children.

PA is nearly always part of atopic dermatitis, the presence of which can help to corroborate the diagnosis.

The use of sunscreen helps to prevent the darkening of surrounding skin, making PA less obvious.

Preventing the eczema in the first place, by taking short showers, using emollients soaps, and moisturizing daily, may be beneficial.

Treating the antecedent eczema early on with group IV or V steroid creams (such as desonide) is useful in decreasing hypopigmentation later on.

HISTORY

Pigment loss is no joke, especially when it appears annually in the same locations. Although it eventually clears up, this 30-year-old-woman has been worried about her condition ever since her (no doubt, well-meaning) sister-in-law suggested it might be vitiligo.

The patient had no idea what vitiligo was but soon found out when she looked it up. To add to that angst, she has been seen by any number of providers over the years and has been given about as many different diagnoses, including the ever-popular “ringworm,” psoriasis, and mere dry skin.

The patient knows she has always had exceptionally dry skin, as well as seasonal allergies. These are problems almost everyone on her mother’s side of the family has had (as well as the patient’s two siblings).

The patient’s pigment loss seems to peak in the summer, resolving almost completely by Christmas.

DISCUSSION

In general, change in pigment is called dyschromia, but when one adds or loses the normal color of the skin, it’s called either hyperchromia or hypochromia. The distinction is not merely academic, since dyschromic patients can turn a variety of colors: blue (with ingestion of silver salts or minocycline, for example), bronze (seen with Wilson’s and Addison’s diseases and hemochromatosis), brown (as in melasma), or gray (seen with administration of gold salts).

One unusual form of hypochromia is vitiligo, an autoimmune disease eventuating in sharply demarcated areas of complete pigment loss, leaving perfectly white skin in its wake. Vitiligo seldom, if ever, waxes and wanes and never involves associated scaling. But it can certainly be a cosmetic problem, often affecting the face, hands, arms, and legs.

Vitilgo can be treated with varying degrees of success, depending on how early the treatment is instituted and how aggressive the disease is. Quite often, it progresses unnoticed until it has become permanent.

Fortunately, our patient did not have vitiligo and instead had the extremely common pityriasis alba (PA). Osler, the most famous physician of his time (1900), once quipped that he could ”forgive dermatology its complexity, but never its terminology.” Pityriasis alba (PA) sounds imposing. But in fact, it represents a simple but important concept: As cutaneous inflammation subsides, the epidermis can add pigment (called postinflammatory hyperpigmentation) or lose it (postinflammatory hypopigmentation).

PA manifests with patchy partial pigment loss as a postinflammatory consequence of antecedent eczema. The latter, originating most commonly in winter, is almost always part of an overarching diagnosis of atopic dermatitis, minor diagnostic criteria for which also include dry, sensitive skin, seasonal allergies, and asthma (all inherited traits).

The usual progression is thus: Patients with xerosis (dry skin), which is worsened by the low humidity of winter and the appeal of long, hot showers, begin to develop faintly defined, round, slightly scaly patches of eczema on the sides of the face and on the arms. These are so faint that they are often missed by the patient and family until later, in the spring, when the postinflammatory loss of pigment is made more obvious by tanning of the surrounding skin. As one might expect, this is especially obvious in darker-skinned patients whose eczema has long since faded, leaving an exceedingly fine scale (if any).

When the eczema is especially active and inflamed, the annular shape and scaly surface put the inexperienced provider in mind of “ringworm” (tinea corporis). This can be ruled out with a KOH prep and brief history-taking to identify whether a potential source for fungal organisms (new pet, playmates, siblings) exists. Keep in mind that pityriasis alba is far more common than tinea corporis.

The differential diagnosis for patchy hypopigmentation also includes tinea versicolor and (in older patients) cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which would be progressive (albeit slowly) and not seasonal. The organism responsible for tinea versicolor (the commensal yeast Malassezia furfur) needs, among other things, much sebum in order to thrive. As this is an ingredient missing in prepubescent children, it is an important point in ruling out tinea versicolor, which is almost always seasonal as well, in young patients.

On a practical level, the “treatment” of PA predominantly involves easing patients’ (and parents’) minds by giving them a firm diagnosis that does not involve “ringworm,” and a clear idea of the self-limiting nature of the problem. See below for other treatment ideas.

LEARNING POINTS

Pityriasis alba (PA) favors the sides of the face and triceps areas of both arms; it is especially common in darker-skinned children.

PA is nearly always part of atopic dermatitis, the presence of which can help to corroborate the diagnosis.

The use of sunscreen helps to prevent the darkening of surrounding skin, making PA less obvious.

Preventing the eczema in the first place, by taking short showers, using emollients soaps, and moisturizing daily, may be beneficial.

Treating the antecedent eczema early on with group IV or V steroid creams (such as desonide) is useful in decreasing hypopigmentation later on.

HISTORY

Pigment loss is no joke, especially when it appears annually in the same locations. Although it eventually clears up, this 30-year-old-woman has been worried about her condition ever since her (no doubt, well-meaning) sister-in-law suggested it might be vitiligo.

The patient had no idea what vitiligo was but soon found out when she looked it up. To add to that angst, she has been seen by any number of providers over the years and has been given about as many different diagnoses, including the ever-popular “ringworm,” psoriasis, and mere dry skin.

The patient knows she has always had exceptionally dry skin, as well as seasonal allergies. These are problems almost everyone on her mother’s side of the family has had (as well as the patient’s two siblings).

The patient’s pigment loss seems to peak in the summer, resolving almost completely by Christmas.

DISCUSSION

In general, change in pigment is called dyschromia, but when one adds or loses the normal color of the skin, it’s called either hyperchromia or hypochromia. The distinction is not merely academic, since dyschromic patients can turn a variety of colors: blue (with ingestion of silver salts or minocycline, for example), bronze (seen with Wilson’s and Addison’s diseases and hemochromatosis), brown (as in melasma), or gray (seen with administration of gold salts).

One unusual form of hypochromia is vitiligo, an autoimmune disease eventuating in sharply demarcated areas of complete pigment loss, leaving perfectly white skin in its wake. Vitiligo seldom, if ever, waxes and wanes and never involves associated scaling. But it can certainly be a cosmetic problem, often affecting the face, hands, arms, and legs.

Vitilgo can be treated with varying degrees of success, depending on how early the treatment is instituted and how aggressive the disease is. Quite often, it progresses unnoticed until it has become permanent.

Fortunately, our patient did not have vitiligo and instead had the extremely common pityriasis alba (PA). Osler, the most famous physician of his time (1900), once quipped that he could ”forgive dermatology its complexity, but never its terminology.” Pityriasis alba (PA) sounds imposing. But in fact, it represents a simple but important concept: As cutaneous inflammation subsides, the epidermis can add pigment (called postinflammatory hyperpigmentation) or lose it (postinflammatory hypopigmentation).

PA manifests with patchy partial pigment loss as a postinflammatory consequence of antecedent eczema. The latter, originating most commonly in winter, is almost always part of an overarching diagnosis of atopic dermatitis, minor diagnostic criteria for which also include dry, sensitive skin, seasonal allergies, and asthma (all inherited traits).

The usual progression is thus: Patients with xerosis (dry skin), which is worsened by the low humidity of winter and the appeal of long, hot showers, begin to develop faintly defined, round, slightly scaly patches of eczema on the sides of the face and on the arms. These are so faint that they are often missed by the patient and family until later, in the spring, when the postinflammatory loss of pigment is made more obvious by tanning of the surrounding skin. As one might expect, this is especially obvious in darker-skinned patients whose eczema has long since faded, leaving an exceedingly fine scale (if any).

When the eczema is especially active and inflamed, the annular shape and scaly surface put the inexperienced provider in mind of “ringworm” (tinea corporis). This can be ruled out with a KOH prep and brief history-taking to identify whether a potential source for fungal organisms (new pet, playmates, siblings) exists. Keep in mind that pityriasis alba is far more common than tinea corporis.

The differential diagnosis for patchy hypopigmentation also includes tinea versicolor and (in older patients) cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, which would be progressive (albeit slowly) and not seasonal. The organism responsible for tinea versicolor (the commensal yeast Malassezia furfur) needs, among other things, much sebum in order to thrive. As this is an ingredient missing in prepubescent children, it is an important point in ruling out tinea versicolor, which is almost always seasonal as well, in young patients.

On a practical level, the “treatment” of PA predominantly involves easing patients’ (and parents’) minds by giving them a firm diagnosis that does not involve “ringworm,” and a clear idea of the self-limiting nature of the problem. See below for other treatment ideas.

LEARNING POINTS

Pityriasis alba (PA) favors the sides of the face and triceps areas of both arms; it is especially common in darker-skinned children.

PA is nearly always part of atopic dermatitis, the presence of which can help to corroborate the diagnosis.

The use of sunscreen helps to prevent the darkening of surrounding skin, making PA less obvious.

Preventing the eczema in the first place, by taking short showers, using emollients soaps, and moisturizing daily, may be beneficial.

Treating the antecedent eczema early on with group IV or V steroid creams (such as desonide) is useful in decreasing hypopigmentation later on.

Patient caught in "vicious cycle" with perioral rash

PATIENT HISTORY

A 38-year-old woman presents with a perioral rash composed of fine papules and pustules, slight erythema, and focal fine scale, which spares the vermillion border by several millimeters. The rash, which burns slightly and feels “tight,” has been present for several months.

During this time, the patient has been applying her sister’s psoriasis cream (clobetasol 0.05%) to the area several times a week. After each application, the rash feels and looks better—but only for a few hours. When she tries to stop using the cream, however, the burning and tightness worsen until she relents and re-applies the cream.

She has already tried changing her makeup and other facial care products, without success. A visit to her primary care provider yielded the diagnosis of “yeast infection,” but the clotrimazole cream he prescribed only made the situation worse.

The patient feels trapped in a vicious cycle, knowing the clobetasol is not really helping but unable to endure the symptoms if she doesn’t use it. A friend finally suggests she see a dermatology provider, an option she hadn’t considered.

DIAGNOSIS/DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of perioral dermatitis (POD), a very common condition that nonetheless seems to baffle non-derm providers. As with so many conditions, POD’s etiology is unknown.

The literature says that at least 90% of POD patients are women, but in my experience, it’s closer to 98%. There are rare cases seen in young children of both genders, and every five years or so, in an adult male.

But just because it occurs mostly in women ages 20 to 50 doesn’t mean it is hormonal in origin, or related to makeup or facial care. As this case illustrates, virtually every woman I’ve seen with POD has long since eliminated those items by trial and error, prior to being seen in dermatology.

The use of steroid medications, as in this case, is common; however, at least half the cases I see do not involve them. By the same token, we often see patients who were treating facial seborrhea or psoriasis with potent topical steroid creams and developed a POD-like eruption in the treated areas (eg, periocular or pernasilar skin).

This case also illustrates the phenomenon of “steroid addiction,” in which the symptoms worsen with attempted withdrawal from the steroid preparation. This locks the patient into a vicious cycle that not only irreparably thins the treated skin, but also makes the POD more difficult to treat.

Histologically, POD closely resembles rosacea, and it responds to some of the same medications. But POD in no way resembles rosacea clinically, and it does not afflict the same population (“flushers and blushers”).

The fine papulopustular, slightly scaly perioral rash seen in this case is typical, as is the sharp sparing of the vermillion border. Various microorganisms have been cultured from POD lesions, but none appear to be causative.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

Topical medications, such as clindamycin and metronidazole, have been used for POD with modest success, but many POD patients complain of already sensitive skin that is further irritated by topical antibiotics. More effective and better tolerated are the oral antibiotics, such as tetracycline (250 to 500 mg bid) or minocycline (50 to 100 mg bid), typically given for at least a month, occasionally longer. This usually results in a cure, though relapses months later are not uncommon.

In this and similar cases, the clobetasol must be discontinued by changing to a much weaker steroid preparation, such as hydrocortisone 2.5 % or topical pimecrolimus 0.1% ointment, eliminating the steroids within two to three weeks. Because withdrawal symptoms in such cases can be severe, considerable patient education and frequent follow-up are necessary. This particular patient was treated with oral minocycline (100 mg bid for two weeks, dropping to 100 QD for three weeks), and will be reevaluated at the end of the treatment cycle.

There is a school of thought that asserts that the best treatment for POD is to withdraw the patient from virtually every contactant, since many POD patients are applying multiple products to their face out of desperation. None work, and some possibly irritate and thus perpetuate the problem.

The rapid response of POD to oral medication is so typical that it is, in effect, diagnostic. With treatment failure, other items in the differential diagnosis would include: contact dermatitis, impetigo, psoriasis, seborrhea, and neurodermatitis (lichen simplex chronicus).

TAKE-HOME TEACHING POINTS

1. POD involves a fine sparse perioral papulopustular rash that spares the upper vermillion border sharply.

2. At least 90% of POD patients are women.

3. Injudicious and prolonged application of steroid creams (especially fluorinated) are implicated in a significant percentage of cases.

4. When steroid “addiction” is found, the medication must be withdrawn slowly and replaced by a weaker steroid cream or pimecrolimus ointment for up to a month.

5. POD can also be seen in the periorbital, perinasilar, and nasolabial areas.

6. In mild cases, consider “treating” POD by simply ceasing all contactants.

7. Consider early referral to dermatology.

PATIENT HISTORY

A 38-year-old woman presents with a perioral rash composed of fine papules and pustules, slight erythema, and focal fine scale, which spares the vermillion border by several millimeters. The rash, which burns slightly and feels “tight,” has been present for several months.

During this time, the patient has been applying her sister’s psoriasis cream (clobetasol 0.05%) to the area several times a week. After each application, the rash feels and looks better—but only for a few hours. When she tries to stop using the cream, however, the burning and tightness worsen until she relents and re-applies the cream.

She has already tried changing her makeup and other facial care products, without success. A visit to her primary care provider yielded the diagnosis of “yeast infection,” but the clotrimazole cream he prescribed only made the situation worse.

The patient feels trapped in a vicious cycle, knowing the clobetasol is not really helping but unable to endure the symptoms if she doesn’t use it. A friend finally suggests she see a dermatology provider, an option she hadn’t considered.

DIAGNOSIS/DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of perioral dermatitis (POD), a very common condition that nonetheless seems to baffle non-derm providers. As with so many conditions, POD’s etiology is unknown.

The literature says that at least 90% of POD patients are women, but in my experience, it’s closer to 98%. There are rare cases seen in young children of both genders, and every five years or so, in an adult male.

But just because it occurs mostly in women ages 20 to 50 doesn’t mean it is hormonal in origin, or related to makeup or facial care. As this case illustrates, virtually every woman I’ve seen with POD has long since eliminated those items by trial and error, prior to being seen in dermatology.

The use of steroid medications, as in this case, is common; however, at least half the cases I see do not involve them. By the same token, we often see patients who were treating facial seborrhea or psoriasis with potent topical steroid creams and developed a POD-like eruption in the treated areas (eg, periocular or pernasilar skin).

This case also illustrates the phenomenon of “steroid addiction,” in which the symptoms worsen with attempted withdrawal from the steroid preparation. This locks the patient into a vicious cycle that not only irreparably thins the treated skin, but also makes the POD more difficult to treat.

Histologically, POD closely resembles rosacea, and it responds to some of the same medications. But POD in no way resembles rosacea clinically, and it does not afflict the same population (“flushers and blushers”).

The fine papulopustular, slightly scaly perioral rash seen in this case is typical, as is the sharp sparing of the vermillion border. Various microorganisms have been cultured from POD lesions, but none appear to be causative.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

Topical medications, such as clindamycin and metronidazole, have been used for POD with modest success, but many POD patients complain of already sensitive skin that is further irritated by topical antibiotics. More effective and better tolerated are the oral antibiotics, such as tetracycline (250 to 500 mg bid) or minocycline (50 to 100 mg bid), typically given for at least a month, occasionally longer. This usually results in a cure, though relapses months later are not uncommon.

In this and similar cases, the clobetasol must be discontinued by changing to a much weaker steroid preparation, such as hydrocortisone 2.5 % or topical pimecrolimus 0.1% ointment, eliminating the steroids within two to three weeks. Because withdrawal symptoms in such cases can be severe, considerable patient education and frequent follow-up are necessary. This particular patient was treated with oral minocycline (100 mg bid for two weeks, dropping to 100 QD for three weeks), and will be reevaluated at the end of the treatment cycle.

There is a school of thought that asserts that the best treatment for POD is to withdraw the patient from virtually every contactant, since many POD patients are applying multiple products to their face out of desperation. None work, and some possibly irritate and thus perpetuate the problem.

The rapid response of POD to oral medication is so typical that it is, in effect, diagnostic. With treatment failure, other items in the differential diagnosis would include: contact dermatitis, impetigo, psoriasis, seborrhea, and neurodermatitis (lichen simplex chronicus).

TAKE-HOME TEACHING POINTS

1. POD involves a fine sparse perioral papulopustular rash that spares the upper vermillion border sharply.

2. At least 90% of POD patients are women.

3. Injudicious and prolonged application of steroid creams (especially fluorinated) are implicated in a significant percentage of cases.

4. When steroid “addiction” is found, the medication must be withdrawn slowly and replaced by a weaker steroid cream or pimecrolimus ointment for up to a month.

5. POD can also be seen in the periorbital, perinasilar, and nasolabial areas.

6. In mild cases, consider “treating” POD by simply ceasing all contactants.

7. Consider early referral to dermatology.

PATIENT HISTORY

A 38-year-old woman presents with a perioral rash composed of fine papules and pustules, slight erythema, and focal fine scale, which spares the vermillion border by several millimeters. The rash, which burns slightly and feels “tight,” has been present for several months.

During this time, the patient has been applying her sister’s psoriasis cream (clobetasol 0.05%) to the area several times a week. After each application, the rash feels and looks better—but only for a few hours. When she tries to stop using the cream, however, the burning and tightness worsen until she relents and re-applies the cream.

She has already tried changing her makeup and other facial care products, without success. A visit to her primary care provider yielded the diagnosis of “yeast infection,” but the clotrimazole cream he prescribed only made the situation worse.

The patient feels trapped in a vicious cycle, knowing the clobetasol is not really helping but unable to endure the symptoms if she doesn’t use it. A friend finally suggests she see a dermatology provider, an option she hadn’t considered.

DIAGNOSIS/DISCUSSION

This is a typical case of perioral dermatitis (POD), a very common condition that nonetheless seems to baffle non-derm providers. As with so many conditions, POD’s etiology is unknown.

The literature says that at least 90% of POD patients are women, but in my experience, it’s closer to 98%. There are rare cases seen in young children of both genders, and every five years or so, in an adult male.

But just because it occurs mostly in women ages 20 to 50 doesn’t mean it is hormonal in origin, or related to makeup or facial care. As this case illustrates, virtually every woman I’ve seen with POD has long since eliminated those items by trial and error, prior to being seen in dermatology.

The use of steroid medications, as in this case, is common; however, at least half the cases I see do not involve them. By the same token, we often see patients who were treating facial seborrhea or psoriasis with potent topical steroid creams and developed a POD-like eruption in the treated areas (eg, periocular or pernasilar skin).

This case also illustrates the phenomenon of “steroid addiction,” in which the symptoms worsen with attempted withdrawal from the steroid preparation. This locks the patient into a vicious cycle that not only irreparably thins the treated skin, but also makes the POD more difficult to treat.

Histologically, POD closely resembles rosacea, and it responds to some of the same medications. But POD in no way resembles rosacea clinically, and it does not afflict the same population (“flushers and blushers”).

The fine papulopustular, slightly scaly perioral rash seen in this case is typical, as is the sharp sparing of the vermillion border. Various microorganisms have been cultured from POD lesions, but none appear to be causative.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

Topical medications, such as clindamycin and metronidazole, have been used for POD with modest success, but many POD patients complain of already sensitive skin that is further irritated by topical antibiotics. More effective and better tolerated are the oral antibiotics, such as tetracycline (250 to 500 mg bid) or minocycline (50 to 100 mg bid), typically given for at least a month, occasionally longer. This usually results in a cure, though relapses months later are not uncommon.

In this and similar cases, the clobetasol must be discontinued by changing to a much weaker steroid preparation, such as hydrocortisone 2.5 % or topical pimecrolimus 0.1% ointment, eliminating the steroids within two to three weeks. Because withdrawal symptoms in such cases can be severe, considerable patient education and frequent follow-up are necessary. This particular patient was treated with oral minocycline (100 mg bid for two weeks, dropping to 100 QD for three weeks), and will be reevaluated at the end of the treatment cycle.

There is a school of thought that asserts that the best treatment for POD is to withdraw the patient from virtually every contactant, since many POD patients are applying multiple products to their face out of desperation. None work, and some possibly irritate and thus perpetuate the problem.

The rapid response of POD to oral medication is so typical that it is, in effect, diagnostic. With treatment failure, other items in the differential diagnosis would include: contact dermatitis, impetigo, psoriasis, seborrhea, and neurodermatitis (lichen simplex chronicus).

TAKE-HOME TEACHING POINTS

1. POD involves a fine sparse perioral papulopustular rash that spares the upper vermillion border sharply.

2. At least 90% of POD patients are women.

3. Injudicious and prolonged application of steroid creams (especially fluorinated) are implicated in a significant percentage of cases.

4. When steroid “addiction” is found, the medication must be withdrawn slowly and replaced by a weaker steroid cream or pimecrolimus ointment for up to a month.

5. POD can also be seen in the periorbital, perinasilar, and nasolabial areas.

6. In mild cases, consider “treating” POD by simply ceasing all contactants.

7. Consider early referral to dermatology.

A persistent rash eludes treatment

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS

A 25-year-old man is urgently referred to dermatology by a local emergency department, where he was seen this morning for the highly symptomatic rash present on his abdomen for more than a year. The presumptive diagnosis is cellulitis; however, the patient has been seen in a number of other medical venues, including urgent care clinics and his primary care provider’s office, where he has received several diagnoses and treatments for yeast infection, impetigo, and fungal infection.

The rash started a few centimeters below his umbilicus but has grown in size. Recently, it became so wet that he started applying a large adhesive bandage to the spot (sometimes twice a day). During this time, he has applied a number of topical products (antifungal creams, antihistamine creams, calamine lotion, and, most consistently, triple-antibiotic cream) and taken several courses of oral antibiotics, including cephalexin and trimethoprim/sulfa. His condition has only worsened.

The patient claims to be in good health otherwise, although he admits to a history of atopy, marked by seasonal allergies and asthma in childhood.

EXAMINATION

This striking rash is sharply confined within square-shaped linear borders (8.5 cm per side), between the umbilicus and the suprapubic area. The surface is quite red and scaly, with focal vesiculation and lichenification. The large bandage (shown reflected inferiorly) has adhesive borders; its surface is visibly damp, but with no discoloration.

The site is slightly edematous but neither tender to touch nor especially warm. There are no palpable nodes in either groin. The patient’s skin elsewhere is free of notable changes or lesions.

DIAGNOSIS/DISCUSSION

It has been pointed out that at least 50% of all cases of allergic contact dermatitis are caused by one of 25 common allergens. Among these, the #1 offender worldwide is nickel–a ubiquitous metal found in inexpensive jewelry and other accessories, such as belt buckles. Chronic exposure to the latter is probably what triggered this patient’s original rash. However, as is often the case, what the patient treats the rash with becomes the problem.

In this case, the topical medication the patient applied most consistently was triple-antibiotic ointment. Triple-antibiotic ointment contains three antimicrobials: neomycin, bacitracin, and polymyxin. The first two are common topical sensitizers. More than likely, this was part of our patient’s problem—as was the unfortunate fact that the belt he is seen wearing was the only belt he owned. In his job as a computer programmer, he was seated at his desk all day, a position that brought the buckle into constant contact with the affected area.

The red linear outline of the area likely represented an irritant dermatitis, an extremely common problem caused by the bandage’s application and removal, as well as the maceration and tearing of the skin, which was already “excited” from the adjacent process. The occlusion provided by the bandage also served to potentiate the effects of the triple-antibiotic ointment.

To summarize, it appears likely that this patient’s rash was initially caused by an allergy to the nickel in his belt buckle, was worsened by the regular application of triple-antibiotic ointment, and was further exacerbated by the application of the large adhesive bandage.

The differential diagnosis included: asteatotic eczema, seborrheic dermatitis, psoriasis, intertrigo, tinea, and impetigo.

TREATMENT/PROGNOSIS

Successful treatment is quite simple: (1) Provide patient education regarding the nature of the problem. (2) Recommend the patient discontinue use of triple-antibiotic ointment (now and forever). (3) Advise the patient to buy and use a new, nonmetallic belt to the exclusion of his old metal belt (now and forever). (4) Prescribe twice-daily application of clobetasol ointment for at least two weeks (with follow-up). (5) Consider the option of prescribing a two-week course of prednisone (tapering from 40 mg/d) or the alternative of intramuscular injection of triamcinolone acetonide (40 to 60 mg), either of which might have been necessary in a more severe case.

TAKE-HOME TEACHING POINTS

1. Consider a broad differential for inflammation of the skin, which includes noninfectious causes.

2. Nickel is the most common topical sensitizer worldwide and affects a significant percentage of the population.

3. What the patient applies to a rash often becomes the problem.

4. Neomycin and bacitracin are common topical sensitizers that are present in triple-antibiotic ointment/cream.

5. Linearity in a rash is strongly suggestive of contact dermatitis.

6. Clear serous drainage is suggestive of inflammation, not infection.

HISTORY OF PRESENT ILLNESS