User login

What medical therapies work for gastroparesis?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

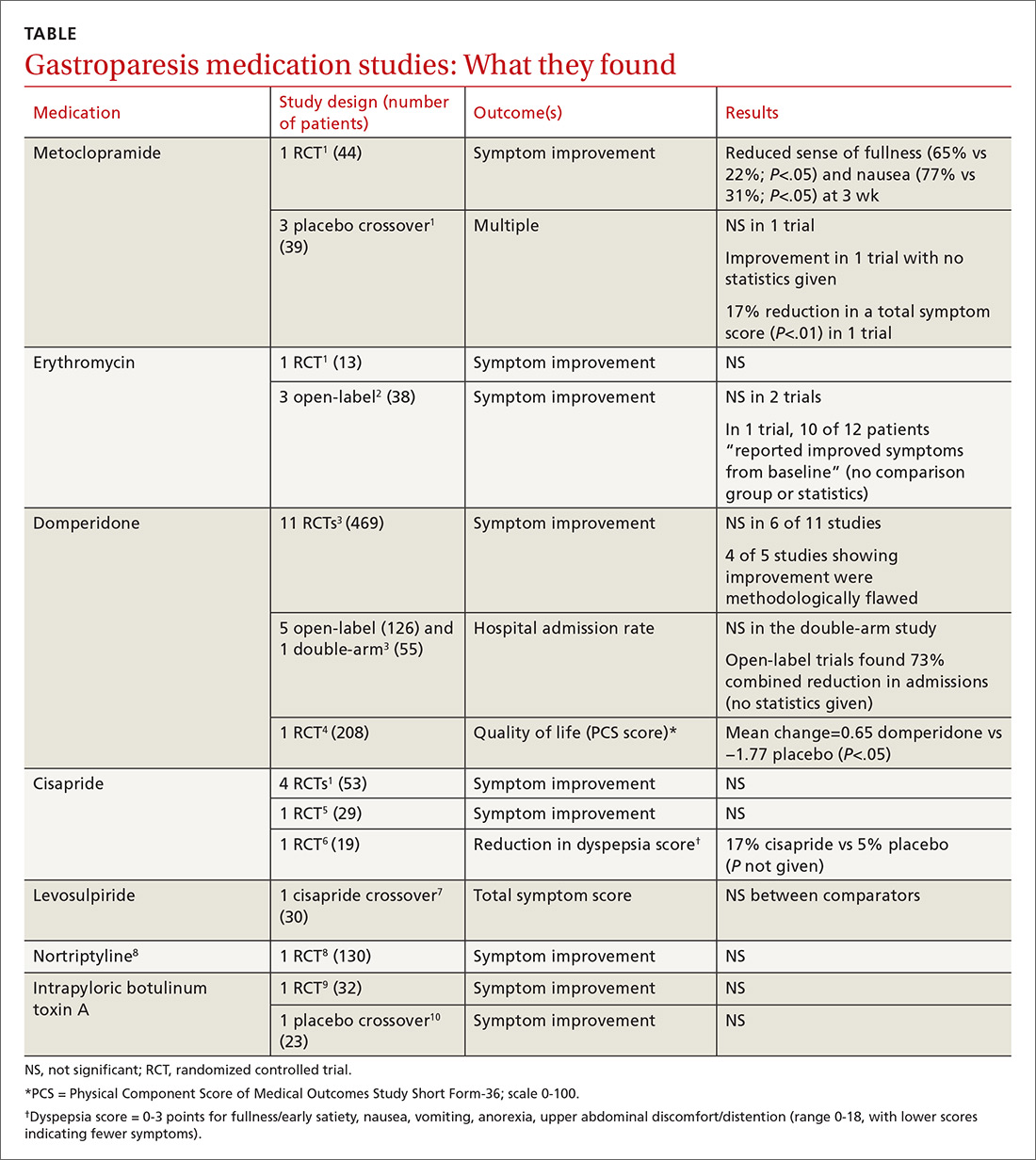

Metoclopramide. One systematic review that looked at the efficacy of metoclopramide for gastroparesis identified one small RCT and 3 smaller placebo-controlled crossover trials.1 The RCT (using 10 mg of metoclopramide after meals and at bedtime) found consistent improvement in the sense of fullness over 3 weeks of therapy, with reduction of nausea at one and 3 weeks, but not at 2 weeks. Vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety didn’t improve. The crossover trials had inconsistent results. The largest one, with only 16 patients, didn’t find an improvement in symptoms.

Erythromycin. Two systematic reviews looked at the efficacy of erythromycin, primarily identifying studies 20- to 30-years old. The first systematic review identified only one small (single-blind) RCT in which erythromycin treatment didn’t change symptoms.1 A second review identified 3 trials described as “open label,” all with fewer than 14 subjects and all lasting a month or less.2 Erythromycin improved patient symptoms in only 1 of the 3, and this trial (like the others) had significant methodologic flaws. The authors of the second review concluded that “the true efficacy of erythromycin in relieving symptoms … remains to be determined.”

Domperidone. A systematic review and one subsequent RCT evaluated domperidone. The systematic review identified 11 randomized, placebo-controlled trials (469 patients).3 Six studies found no impact on patient symptoms, while 5 reported a positive effect. The review also identified 6 trials that evaluated domperidone treatment on hospitalization rates. Open-label (single-arm, unblinded) trials tended to find a reduction in hospitalizations with domperidone, an effect not seen in the one double-arm study that evaluated this outcome.

The review authors noted that given the small size and low methodologic quality of most studies “it is not surprising … that there continues to be controversy about the efficacy of this drug” for symptoms of gastroparesis.

One subsequent RCT, using domperidone 20 mg 4 times daily for 4 weeks, found a 2% improvement over placebo in the physical component of a multifaceted quality-of-life measure.4 The improvement was statistically significant, but of unclear clinical importance.

Cisapride. One systematic review and 2 subsequent RCTs evaluated the clinical effects of cisapride. The systematic review included 4 small RCTs (53 patients) that didn’t individually find changes in patient symptoms.

In one subsequent RCT, comparing 10 mg cisapride 3 times daily to placebo for 2 weeks, cisapride yielded no significant change in symptoms.5 The other RCT compared oral cisapride 10 mg 3 times daily to placebo for one year. Cisapride treatment produced a 17% reduction in symptoms (P<.002 vs baseline), and placebo produced a 5% reduction (P=NS vs baseline). The study didn’t state if the difference between the 2 outcomes was statistically significant.6

Continue to: Levosulpiride

Levosulpiride. One crossover study compared 25 mg levosulpiride with 10 mg cisapride (both given orally 3 times a day) on gastroparesis symptoms and gastric emptying. Each medication was given for one month (washout duration not given). The study found similar efficacy between levosulpiride and cisapride in terms of improvement in gastric emptying rates and total symptom scores.7 No studies compare levosulpiride to placebo.

Nortriptyline. A multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind RCT comparing 75 mg/d nortriptyline for 15 weeks with placebo in adult patients with moderate to severe symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis for at least 6 months found that nortriptyline didn’t improve symptoms.8

Botulinum toxin A. An RCT comparing a single injection of 200 units intrapyloric botulinum toxin A with placebo in adult patients with severe gastroparesis symptoms found that botulinum toxin A didn’t result in symptomatic improvement.9 A crossover trial comparing 100 units monthly intrapyloric botulinum toxin A for 3 months with placebo in patients with gastroparesis found that neither symptoms nor rate of gastric emptying changed with the toxin.10

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology list metoclopramide as the first-line agent for gastroparesis requiring medical therapy, followed by domperidone and then erythromycin (all based on “moderate quality evidence”). Antiemetic agents are also recommended for symptom control.11

1. Sturm A, Holtmann G, Goebell H, et al. Prokinetics in patients with gastroparesis: a systematic analysis. Digestion. 1999;60:422-427.

2. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:259-263.

3. Sugumar A, Singh A, Pasricha PJ. A systematic review of the efficacy of domperidone for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:726-733.

4. Farup CE, Leidy NK, Murray M, et al. Effect of domperidone on the health-related quality of life of patients with symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1699-1706.

5. Dutta U, Padhy AK, Ahuja V, et al. Double blind controlled trial of effect of cisapride on gastric emptying in diabetics. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:116-119.

6. Braden B, Enghofer M, Schaub M, et al. Long-term cisapride treatment improves diabetic gastroparesis but not glycaemic control. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1341-1346.

7. Mansi C, Borro P, Giacomini M, et al. Comparative effects of levosulpiride and cisapride on gastric emptying and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:561-569.

8. Parkman HP, Van Natta ML, Abell TL, et al. Effect of nortriptyline on symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis: the NORIG randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2640-2649.

9. Friedenberg FK, Palit A, Parkman HP, et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of delayed gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:416-423.

10. Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1251-1258.

11. Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-38.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Metoclopramide. One systematic review that looked at the efficacy of metoclopramide for gastroparesis identified one small RCT and 3 smaller placebo-controlled crossover trials.1 The RCT (using 10 mg of metoclopramide after meals and at bedtime) found consistent improvement in the sense of fullness over 3 weeks of therapy, with reduction of nausea at one and 3 weeks, but not at 2 weeks. Vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety didn’t improve. The crossover trials had inconsistent results. The largest one, with only 16 patients, didn’t find an improvement in symptoms.

Erythromycin. Two systematic reviews looked at the efficacy of erythromycin, primarily identifying studies 20- to 30-years old. The first systematic review identified only one small (single-blind) RCT in which erythromycin treatment didn’t change symptoms.1 A second review identified 3 trials described as “open label,” all with fewer than 14 subjects and all lasting a month or less.2 Erythromycin improved patient symptoms in only 1 of the 3, and this trial (like the others) had significant methodologic flaws. The authors of the second review concluded that “the true efficacy of erythromycin in relieving symptoms … remains to be determined.”

Domperidone. A systematic review and one subsequent RCT evaluated domperidone. The systematic review identified 11 randomized, placebo-controlled trials (469 patients).3 Six studies found no impact on patient symptoms, while 5 reported a positive effect. The review also identified 6 trials that evaluated domperidone treatment on hospitalization rates. Open-label (single-arm, unblinded) trials tended to find a reduction in hospitalizations with domperidone, an effect not seen in the one double-arm study that evaluated this outcome.

The review authors noted that given the small size and low methodologic quality of most studies “it is not surprising … that there continues to be controversy about the efficacy of this drug” for symptoms of gastroparesis.

One subsequent RCT, using domperidone 20 mg 4 times daily for 4 weeks, found a 2% improvement over placebo in the physical component of a multifaceted quality-of-life measure.4 The improvement was statistically significant, but of unclear clinical importance.

Cisapride. One systematic review and 2 subsequent RCTs evaluated the clinical effects of cisapride. The systematic review included 4 small RCTs (53 patients) that didn’t individually find changes in patient symptoms.

In one subsequent RCT, comparing 10 mg cisapride 3 times daily to placebo for 2 weeks, cisapride yielded no significant change in symptoms.5 The other RCT compared oral cisapride 10 mg 3 times daily to placebo for one year. Cisapride treatment produced a 17% reduction in symptoms (P<.002 vs baseline), and placebo produced a 5% reduction (P=NS vs baseline). The study didn’t state if the difference between the 2 outcomes was statistically significant.6

Continue to: Levosulpiride

Levosulpiride. One crossover study compared 25 mg levosulpiride with 10 mg cisapride (both given orally 3 times a day) on gastroparesis symptoms and gastric emptying. Each medication was given for one month (washout duration not given). The study found similar efficacy between levosulpiride and cisapride in terms of improvement in gastric emptying rates and total symptom scores.7 No studies compare levosulpiride to placebo.

Nortriptyline. A multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind RCT comparing 75 mg/d nortriptyline for 15 weeks with placebo in adult patients with moderate to severe symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis for at least 6 months found that nortriptyline didn’t improve symptoms.8

Botulinum toxin A. An RCT comparing a single injection of 200 units intrapyloric botulinum toxin A with placebo in adult patients with severe gastroparesis symptoms found that botulinum toxin A didn’t result in symptomatic improvement.9 A crossover trial comparing 100 units monthly intrapyloric botulinum toxin A for 3 months with placebo in patients with gastroparesis found that neither symptoms nor rate of gastric emptying changed with the toxin.10

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology list metoclopramide as the first-line agent for gastroparesis requiring medical therapy, followed by domperidone and then erythromycin (all based on “moderate quality evidence”). Antiemetic agents are also recommended for symptom control.11

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

Metoclopramide. One systematic review that looked at the efficacy of metoclopramide for gastroparesis identified one small RCT and 3 smaller placebo-controlled crossover trials.1 The RCT (using 10 mg of metoclopramide after meals and at bedtime) found consistent improvement in the sense of fullness over 3 weeks of therapy, with reduction of nausea at one and 3 weeks, but not at 2 weeks. Vomiting, anorexia, and early satiety didn’t improve. The crossover trials had inconsistent results. The largest one, with only 16 patients, didn’t find an improvement in symptoms.

Erythromycin. Two systematic reviews looked at the efficacy of erythromycin, primarily identifying studies 20- to 30-years old. The first systematic review identified only one small (single-blind) RCT in which erythromycin treatment didn’t change symptoms.1 A second review identified 3 trials described as “open label,” all with fewer than 14 subjects and all lasting a month or less.2 Erythromycin improved patient symptoms in only 1 of the 3, and this trial (like the others) had significant methodologic flaws. The authors of the second review concluded that “the true efficacy of erythromycin in relieving symptoms … remains to be determined.”

Domperidone. A systematic review and one subsequent RCT evaluated domperidone. The systematic review identified 11 randomized, placebo-controlled trials (469 patients).3 Six studies found no impact on patient symptoms, while 5 reported a positive effect. The review also identified 6 trials that evaluated domperidone treatment on hospitalization rates. Open-label (single-arm, unblinded) trials tended to find a reduction in hospitalizations with domperidone, an effect not seen in the one double-arm study that evaluated this outcome.

The review authors noted that given the small size and low methodologic quality of most studies “it is not surprising … that there continues to be controversy about the efficacy of this drug” for symptoms of gastroparesis.

One subsequent RCT, using domperidone 20 mg 4 times daily for 4 weeks, found a 2% improvement over placebo in the physical component of a multifaceted quality-of-life measure.4 The improvement was statistically significant, but of unclear clinical importance.

Cisapride. One systematic review and 2 subsequent RCTs evaluated the clinical effects of cisapride. The systematic review included 4 small RCTs (53 patients) that didn’t individually find changes in patient symptoms.

In one subsequent RCT, comparing 10 mg cisapride 3 times daily to placebo for 2 weeks, cisapride yielded no significant change in symptoms.5 The other RCT compared oral cisapride 10 mg 3 times daily to placebo for one year. Cisapride treatment produced a 17% reduction in symptoms (P<.002 vs baseline), and placebo produced a 5% reduction (P=NS vs baseline). The study didn’t state if the difference between the 2 outcomes was statistically significant.6

Continue to: Levosulpiride

Levosulpiride. One crossover study compared 25 mg levosulpiride with 10 mg cisapride (both given orally 3 times a day) on gastroparesis symptoms and gastric emptying. Each medication was given for one month (washout duration not given). The study found similar efficacy between levosulpiride and cisapride in terms of improvement in gastric emptying rates and total symptom scores.7 No studies compare levosulpiride to placebo.

Nortriptyline. A multicenter, parallel-group, double-blind RCT comparing 75 mg/d nortriptyline for 15 weeks with placebo in adult patients with moderate to severe symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis for at least 6 months found that nortriptyline didn’t improve symptoms.8

Botulinum toxin A. An RCT comparing a single injection of 200 units intrapyloric botulinum toxin A with placebo in adult patients with severe gastroparesis symptoms found that botulinum toxin A didn’t result in symptomatic improvement.9 A crossover trial comparing 100 units monthly intrapyloric botulinum toxin A for 3 months with placebo in patients with gastroparesis found that neither symptoms nor rate of gastric emptying changed with the toxin.10

RECOMMENDATIONS

The 2013 guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology list metoclopramide as the first-line agent for gastroparesis requiring medical therapy, followed by domperidone and then erythromycin (all based on “moderate quality evidence”). Antiemetic agents are also recommended for symptom control.11

1. Sturm A, Holtmann G, Goebell H, et al. Prokinetics in patients with gastroparesis: a systematic analysis. Digestion. 1999;60:422-427.

2. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:259-263.

3. Sugumar A, Singh A, Pasricha PJ. A systematic review of the efficacy of domperidone for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:726-733.

4. Farup CE, Leidy NK, Murray M, et al. Effect of domperidone on the health-related quality of life of patients with symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1699-1706.

5. Dutta U, Padhy AK, Ahuja V, et al. Double blind controlled trial of effect of cisapride on gastric emptying in diabetics. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:116-119.

6. Braden B, Enghofer M, Schaub M, et al. Long-term cisapride treatment improves diabetic gastroparesis but not glycaemic control. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1341-1346.

7. Mansi C, Borro P, Giacomini M, et al. Comparative effects of levosulpiride and cisapride on gastric emptying and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:561-569.

8. Parkman HP, Van Natta ML, Abell TL, et al. Effect of nortriptyline on symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis: the NORIG randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2640-2649.

9. Friedenberg FK, Palit A, Parkman HP, et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of delayed gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:416-423.

10. Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1251-1258.

11. Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-38.

1. Sturm A, Holtmann G, Goebell H, et al. Prokinetics in patients with gastroparesis: a systematic analysis. Digestion. 1999;60:422-427.

2. Maganti K, Onyemere K, Jones MP. Oral erythromycin and symptomatic relief of gastroparesis: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:259-263.

3. Sugumar A, Singh A, Pasricha PJ. A systematic review of the efficacy of domperidone for the treatment of diabetic gastroparesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:726-733.

4. Farup CE, Leidy NK, Murray M, et al. Effect of domperidone on the health-related quality of life of patients with symptoms of diabetic gastroparesis. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:1699-1706.

5. Dutta U, Padhy AK, Ahuja V, et al. Double blind controlled trial of effect of cisapride on gastric emptying in diabetics. Trop Gastroenterol. 1999;20:116-119.

6. Braden B, Enghofer M, Schaub M, et al. Long-term cisapride treatment improves diabetic gastroparesis but not glycaemic control. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1341-1346.

7. Mansi C, Borro P, Giacomini M, et al. Comparative effects of levosulpiride and cisapride on gastric emptying and symptoms in patients with functional dyspepsia and gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2000;14:561-569.

8. Parkman HP, Van Natta ML, Abell TL, et al. Effect of nortriptyline on symptoms of idiopathic gastroparesis: the NORIG randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2640-2649.

9. Friedenberg FK, Palit A, Parkman HP, et al. Botulinum toxin A for the treatment of delayed gastric emptying. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:416-423.

10. Arts J, Holvoet L, Caenepeel P, et al. Clinical trial: a randomized-controlled crossover study of intrapyloric injection of botulinum toxin in gastroparesis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1251-1258.

11. Camilleri M, Parkman HP, Shafi MA, et al. Clinical guideline: management of gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:18-38.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

It’s unclear if there are any highly effective medications for gastroparesis (TABLE1-10). Metoclopramide improves the sense of fullness by about 40% for as long as 3 weeks, may improve nausea, and doesn’t affect vomiting or anorexia (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small randomized controlled trial [RCT]).

Whether or not erythromycin has an effect on symptoms is unclear (SOR: C, conflicting trials and expert opinion).

Domperidone may improve quality of life (by 2%) for as long as a year, but its effect on symptoms is also unclear (SOR: C, small RCTs).

Cisapride may not be effective for symptom relief (SOR: C, small conflicting RCTs), and levosulpiride is likely similar to cisapride (SOR: C, single small crossover trial).

Nortriptyline (SOR: B, single RCT) and intrapyloric botulinum toxin A (SOR: B, small RCT and crossover trial) aren’t effective for symptom relief.

How effectively do ACE inhibitors and ARBs prevent migraines?

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

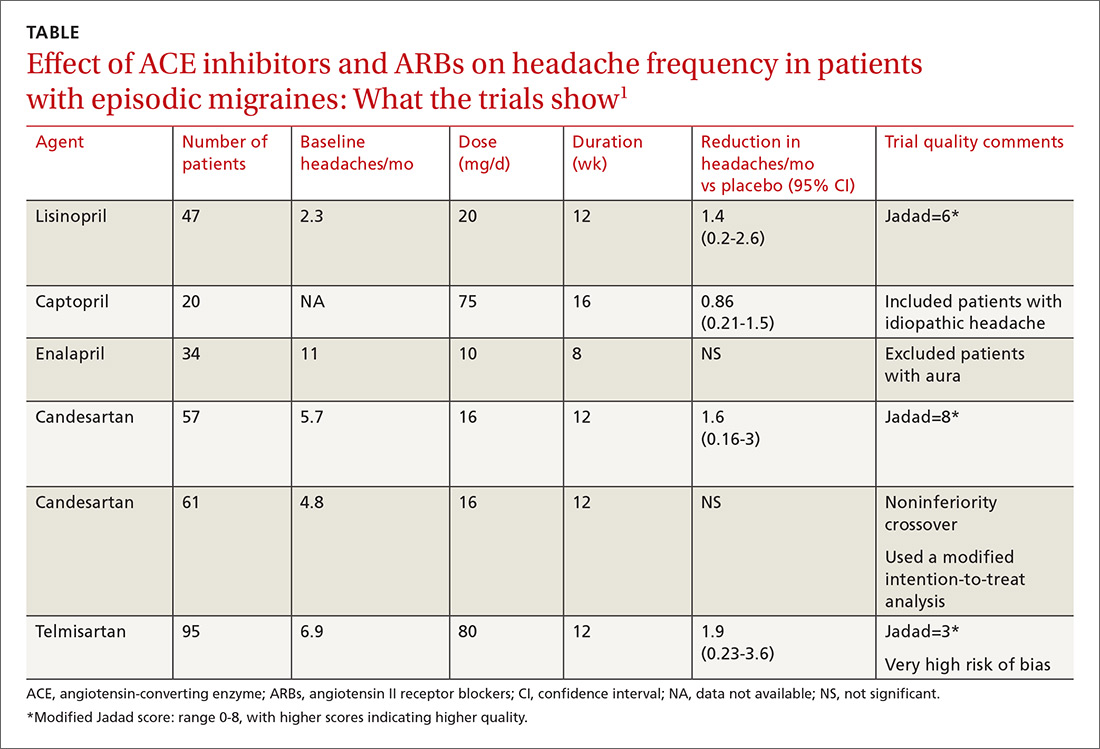

A network meta-analysis of 179 placebo-controlled trials of medications to treat migraine1 headache identified 3 trials involving ACE inhibitors and 3 involving ARBs (TABLE1). The authors of the meta-analysis gave 2 trials (one of lisinopril and one of candesartan) relatively high scores for methodologic quality.

Lisinopril reduces hours, days with headache and days with migraine

The first, a placebo-controlled lisinopril crossover trial, included 60 patients, 19 to 59 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.2 Thirty patients received lisinopril 10 mg once daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg once daily (using 10-mg tablets) for 11 weeks. The other 30 patients received a similarly titrated placebo for 12 weeks. After a 2-week washout period, the groups were given the other therapy. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. Primary outcomes, extracted from headache diaries, included the number of hours and days with headache (of any type) and number of days with migraine specifically.

Out of the initial 60 participants, 47 completed the study. Using intention-to-treat analysis, lisinopril therapy resulted in fewer hours with headache (162 vs 138, a 15% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0-30), fewer days with headache (25 vs 21, a 16% difference; 95% CI, 5-27), and fewer days with migraine (19 vs 15, a 22% change; 95% CI, 11-33), compared with placebo. Three patients discontinued lisinopril because of adverse events. Mean blood pressure reduction with lisinopril was 7 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic more than placebo (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Candesartan also decreases headaches and migraine

The other study given a high methodologic quality score by the network-meta-analysis authors was a placebo-controlled candesartan crossover trial.3 It enrolled 60 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.

Thirty patients received 16 mg candesartan daily for 12 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period before taking a placebo tablet daily for 12 weeks. The other 30 received placebo followed by candesartan. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. The primary outcome measure was days with headache, recorded by patients using daily diaries. Three patients didn’t complete the study.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, the mean number of days with headache was 18.5 with placebo and 13.6 with candesartan (P=.001). Secondary end points that also favored candesartan were hours with migraine (92 vs 59; P<.001), hours with headache (139 vs 95; P<.001), days with migraine (13 vs 9; P<.001), and days of sick leave (3.9 vs 1.4; P=.01). Adverse events, including dizziness, were similar with candesartan and placebo. Mean blood pressure reduction with candesartan was 11 mm Hg systolic and 7 mm Hg diastolic over placebo (P<.001 for both comparisons).

Continue to: Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Among all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials in the review, a network meta-analysis (designed to compare interventions never studied head-to-head) could be performed only on candesartan, which had a small effect size on headache frequency relative to placebo (2 trials, 118 patients; standardized mean difference [SMD]= −0.33; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.7).1 (An SMD of 0.2 is considered small, 0.6 moderate, and 1.2 large). Combining data from all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials together in a standard meta-analysis yielded a large effect size on number of headaches per month compared with placebo (6 trials, 351 patients; SMD= −1.12; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.27).1

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society published guidelines on pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults.4 The guidelines stated that lisinopril and candesartan were “possibly effective” for migraine prevention (level C recommendation based on a single lower-quality randomized clinical trial). They further advised clinicians to be “mindful of comorbid and coexistent conditions in patients with migraine to maximize potential treatment efficacy.”

1. Jackson JL, Cogbil E, Santana-Davila R, et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PloS One. 2015;10:e0130733.

2. Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19-22.

3. Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65-69.

4. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis of 179 placebo-controlled trials of medications to treat migraine1 headache identified 3 trials involving ACE inhibitors and 3 involving ARBs (TABLE1). The authors of the meta-analysis gave 2 trials (one of lisinopril and one of candesartan) relatively high scores for methodologic quality.

Lisinopril reduces hours, days with headache and days with migraine

The first, a placebo-controlled lisinopril crossover trial, included 60 patients, 19 to 59 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.2 Thirty patients received lisinopril 10 mg once daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg once daily (using 10-mg tablets) for 11 weeks. The other 30 patients received a similarly titrated placebo for 12 weeks. After a 2-week washout period, the groups were given the other therapy. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. Primary outcomes, extracted from headache diaries, included the number of hours and days with headache (of any type) and number of days with migraine specifically.

Out of the initial 60 participants, 47 completed the study. Using intention-to-treat analysis, lisinopril therapy resulted in fewer hours with headache (162 vs 138, a 15% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0-30), fewer days with headache (25 vs 21, a 16% difference; 95% CI, 5-27), and fewer days with migraine (19 vs 15, a 22% change; 95% CI, 11-33), compared with placebo. Three patients discontinued lisinopril because of adverse events. Mean blood pressure reduction with lisinopril was 7 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic more than placebo (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Candesartan also decreases headaches and migraine

The other study given a high methodologic quality score by the network-meta-analysis authors was a placebo-controlled candesartan crossover trial.3 It enrolled 60 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.

Thirty patients received 16 mg candesartan daily for 12 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period before taking a placebo tablet daily for 12 weeks. The other 30 received placebo followed by candesartan. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. The primary outcome measure was days with headache, recorded by patients using daily diaries. Three patients didn’t complete the study.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, the mean number of days with headache was 18.5 with placebo and 13.6 with candesartan (P=.001). Secondary end points that also favored candesartan were hours with migraine (92 vs 59; P<.001), hours with headache (139 vs 95; P<.001), days with migraine (13 vs 9; P<.001), and days of sick leave (3.9 vs 1.4; P=.01). Adverse events, including dizziness, were similar with candesartan and placebo. Mean blood pressure reduction with candesartan was 11 mm Hg systolic and 7 mm Hg diastolic over placebo (P<.001 for both comparisons).

Continue to: Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Among all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials in the review, a network meta-analysis (designed to compare interventions never studied head-to-head) could be performed only on candesartan, which had a small effect size on headache frequency relative to placebo (2 trials, 118 patients; standardized mean difference [SMD]= −0.33; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.7).1 (An SMD of 0.2 is considered small, 0.6 moderate, and 1.2 large). Combining data from all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials together in a standard meta-analysis yielded a large effect size on number of headaches per month compared with placebo (6 trials, 351 patients; SMD= −1.12; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.27).1

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society published guidelines on pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults.4 The guidelines stated that lisinopril and candesartan were “possibly effective” for migraine prevention (level C recommendation based on a single lower-quality randomized clinical trial). They further advised clinicians to be “mindful of comorbid and coexistent conditions in patients with migraine to maximize potential treatment efficacy.”

EVIDENCE SUMMARY

A network meta-analysis of 179 placebo-controlled trials of medications to treat migraine1 headache identified 3 trials involving ACE inhibitors and 3 involving ARBs (TABLE1). The authors of the meta-analysis gave 2 trials (one of lisinopril and one of candesartan) relatively high scores for methodologic quality.

Lisinopril reduces hours, days with headache and days with migraine

The first, a placebo-controlled lisinopril crossover trial, included 60 patients, 19 to 59 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.2 Thirty patients received lisinopril 10 mg once daily for 1 week followed by 20 mg once daily (using 10-mg tablets) for 11 weeks. The other 30 patients received a similarly titrated placebo for 12 weeks. After a 2-week washout period, the groups were given the other therapy. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. Primary outcomes, extracted from headache diaries, included the number of hours and days with headache (of any type) and number of days with migraine specifically.

Out of the initial 60 participants, 47 completed the study. Using intention-to-treat analysis, lisinopril therapy resulted in fewer hours with headache (162 vs 138, a 15% difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0-30), fewer days with headache (25 vs 21, a 16% difference; 95% CI, 5-27), and fewer days with migraine (19 vs 15, a 22% change; 95% CI, 11-33), compared with placebo. Three patients discontinued lisinopril because of adverse events. Mean blood pressure reduction with lisinopril was 7 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic more than placebo (P<.0001 for both comparisons).

Candesartan also decreases headaches and migraine

The other study given a high methodologic quality score by the network-meta-analysis authors was a placebo-controlled candesartan crossover trial.3 It enrolled 60 patients, 18 to 65 years of age, who experienced migraines with or without auras 2 to 6 times per month.

Thirty patients received 16 mg candesartan daily for 12 weeks, followed by a 4-week washout period before taking a placebo tablet daily for 12 weeks. The other 30 received placebo followed by candesartan. Patients took triptan medications and analgesics as needed. The primary outcome measure was days with headache, recorded by patients using daily diaries. Three patients didn’t complete the study.

Using intention-to-treat analysis, the mean number of days with headache was 18.5 with placebo and 13.6 with candesartan (P=.001). Secondary end points that also favored candesartan were hours with migraine (92 vs 59; P<.001), hours with headache (139 vs 95; P<.001), days with migraine (13 vs 9; P<.001), and days of sick leave (3.9 vs 1.4; P=.01). Adverse events, including dizziness, were similar with candesartan and placebo. Mean blood pressure reduction with candesartan was 11 mm Hg systolic and 7 mm Hg diastolic over placebo (P<.001 for both comparisons).

Continue to: Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Overall both drugs have a significant effect on number of headaches

Among all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials in the review, a network meta-analysis (designed to compare interventions never studied head-to-head) could be performed only on candesartan, which had a small effect size on headache frequency relative to placebo (2 trials, 118 patients; standardized mean difference [SMD]= −0.33; 95% CI, −0.59 to −0.7).1 (An SMD of 0.2 is considered small, 0.6 moderate, and 1.2 large). Combining data from all ACE inhibitor and ARB trials together in a standard meta-analysis yielded a large effect size on number of headaches per month compared with placebo (6 trials, 351 patients; SMD= −1.12; 95% CI, −1.97 to −0.27).1

RECOMMENDATIONS

In 2012, the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society published guidelines on pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults.4 The guidelines stated that lisinopril and candesartan were “possibly effective” for migraine prevention (level C recommendation based on a single lower-quality randomized clinical trial). They further advised clinicians to be “mindful of comorbid and coexistent conditions in patients with migraine to maximize potential treatment efficacy.”

1. Jackson JL, Cogbil E, Santana-Davila R, et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PloS One. 2015;10:e0130733.

2. Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19-22.

3. Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65-69.

4. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

1. Jackson JL, Cogbil E, Santana-Davila R, et al. A comparative effectiveness meta-analysis of drugs for the prophylaxis of migraine headache. PloS One. 2015;10:e0130733.

2. Schrader H, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomized, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ. 2001;322:19-22.

3. Tronvik E, Stovner LJ, Helde G, et al. Prophylactic treatment of migraine with an angiotensin II receptor blocker: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;289:65-69.

4. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology. 2012;78:1337-1345.

EVIDENCE-BASED ANSWER:

The angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor lisinopril reduces the number of migraines by about 1.5 per month in patients experiencing 2 to 6 migraines monthly (strength of recommendation [SOR]: B, small crossover trial); the angiotensin II receptor blocker (ARB) candesartan may produce a similar reduction (SOR: C, conflicting crossover trials).

Considered as a group, ACE inhibitors and ARBs have a moderate to large effect on the frequency of migraine headaches (SOR: B, meta-analysis of small clinical trials), although only lisinopril and candesartan show fair to good evidence of efficacy.

Providers may consider lisinopril or candesartan for migraine prevention, taking into account their effect on other medical conditions (SOR: C, expert opinion).