User login

Red painful nodules in a hospitalized patient

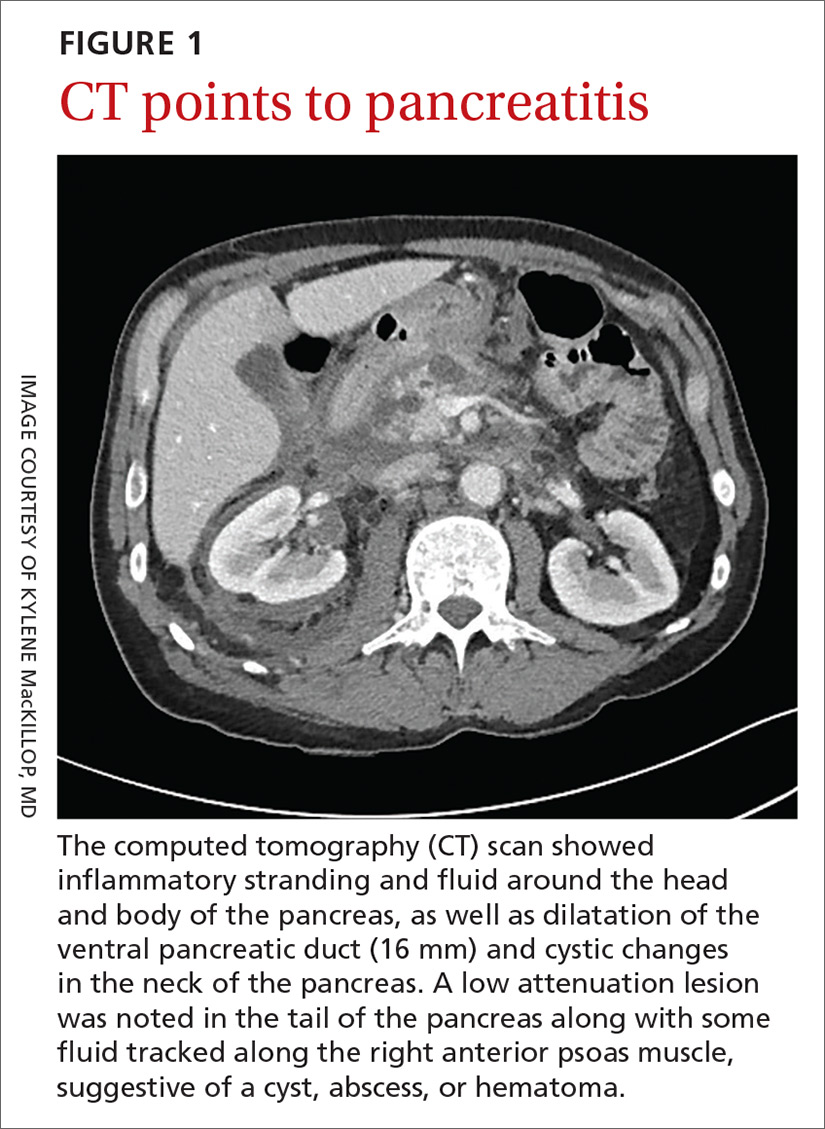

A 58-year-old white man with a history of alcoholism presented to the emergency department with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back, as well as emesis and anorexia. An elevated lipase of 16,609 U/L (reference range, 31–186 U/L) and pathognomonic abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings (FIGURE 1) led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, for which he was admitted.

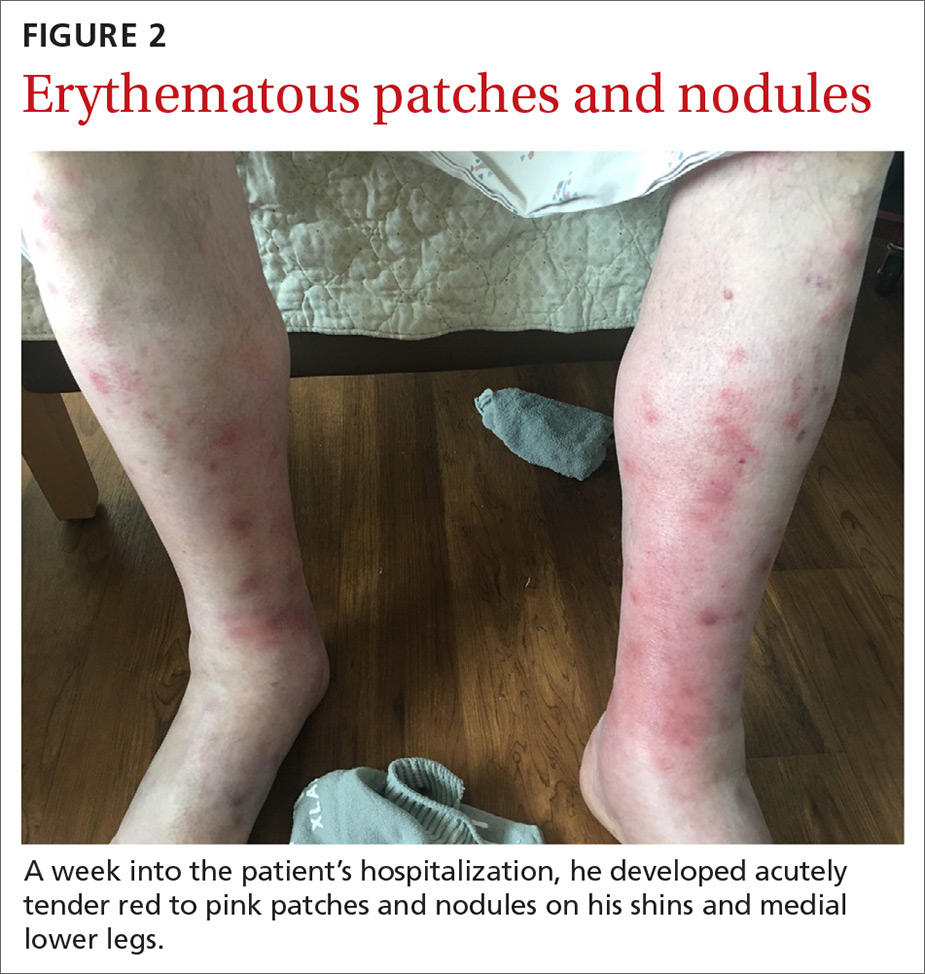

Fluid resuscitation and pain management were implemented, and over 3 days his diet was advanced from NPO to clear fluids to a full diet. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient developed increasing abdominal pain and worsening leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.6–22 K/mcL [reference range, 4.5–11 K/mcL]). Repeat CT and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for presumed necrotizing pancreatitis. The next day he developed acutely tender red to pink patches and nodules on his shins and medial lower legs (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pancreatic panniculitis

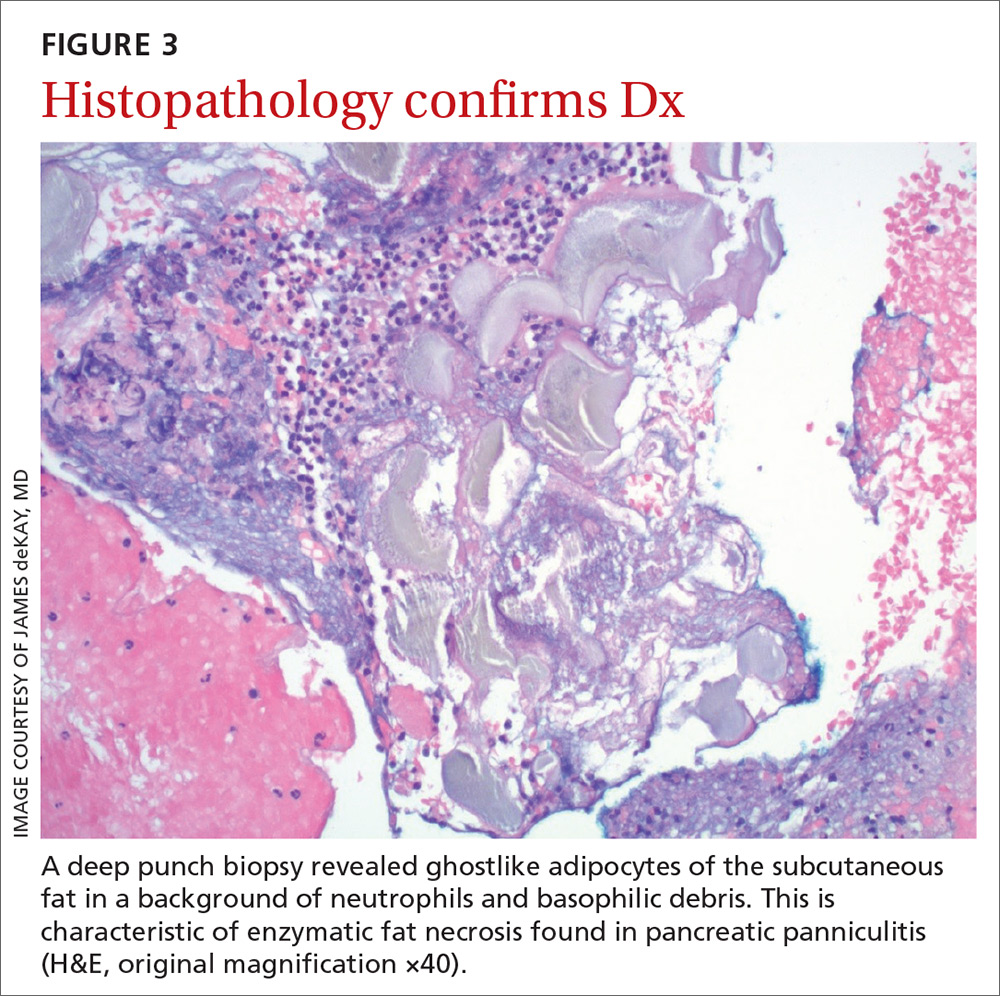

It’s theorized that the systemic release of trypsin from pancreatic cell destruction causes increased capillary permeability and subsequent escape of lipase from the circulation into the subcutaneous fat. This causes fat necrosis, saponification, and inflammation.3,4 Pancreatic panniculitis is demonstrated histologically as hollowed-out adipocytes with granular basophilic cytoplasm and displaced or absent nuclei—aptly named “ghostlike” adipocytes.3-6

Painful, erythematous nodules most commonly present on the distal lower extremities. Nodules may be found over the shins, posterior calves, and periarticular skin. Rarely, nodules may occur on the buttocks, abdomen, or intramedullary bone.7 In severe cases, nodules spontaneously may ulcerate and drain an oily brown, viscous material formed from necrotic adipocytes.1

Timing of the eruption of skin lesions is varied and may even precede abdominal pain. Lesions can involute and regress several weeks after the underlying etiology improves. With pancreatic carcinoma, there is a greater likelihood of persistence, atypical locations of involvement, ulcerations, and recurrences.7

The histologic features of pancreatic panniculitis and the assessment of the subcutaneous fat are paramount in diagnosis. A deep punch biopsy or incisional biopsy is necessary to reliably reach the depth of the subcutaneous tissue. In our patient, a deep punch biopsy from the lateral calf was performed at the suggestion of Dermatology, and histopathology revealed necrosis of fat lobules with calcium soap around necrotic lipocytes, consistent with pancreatic panniculitis (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

The differential diagnosis was broad due to the confounding factors of recent antibiotic use and worsening pancreatitis.

Cellulitis may present as a red patch and is common on the lower legs; it often is associated with skin pathogens including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Usually, symptoms are unilateral and associated with warmth to the touch, expanding borders, leukocytosis, and systemic symptoms.

Vasculitis, which is an inflammation of various sized vessels through immunologic or infectious processes, often manifests on the lower legs. The characteristic sign of small vessel vasculitis is nonblanching purpura or petechiae. There often is a preceding illness or medication that triggers immunoglobulin proliferation and off-target inflammation of the vessels. Associated symptoms include pain and pruritus.

Drug eruptions may present as red patches on the skin. Often the patches are scaly and red and have more widespread distribution than the lower legs. A history of exposure is important, but common inciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used only occasionally and are challenging to elicit in the history. Our patient did have known drug changes (ie, the introduction of meropenem) while hospitalized, but the morphology was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Treatment is directed to underlying disease

Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis primarily is supportive and directed toward treating the underlying pancreatic disease. Depending upon the underlying pancreatic diagnosis, surgical correction of anatomic or ductal anomalies or pseudocysts may lead to resolution of panniculitis.3,7,8

Continue to: In this case

In this case, our patient had already received fluid resuscitation and pain management, and his diet had been advanced. In addition, his antibiotics were changed to exclude drug eruption as a cause. Over the course of a week, our patient saw a reduction in his pain level and an improvement in the appearance of his legs (FIGURE 4).

His pancreatitis, however, continued to persist and resist increases in his diet. He ultimately required transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of interventional options including stenting. The patient ultimately recovered, after stenting of the main pancreatic duct, and was discharged home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; Jonathan.Karnes@mainegeneral.org

1. Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 2):331-334.

3. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

4. Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

5. Förström TL, Winkelmann RK. Acute, generalized panniculitis with amylase and lipase in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:497-502.

6. Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:506-510.

7. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

8. Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chro nic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835-1837.

A 58-year-old white man with a history of alcoholism presented to the emergency department with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back, as well as emesis and anorexia. An elevated lipase of 16,609 U/L (reference range, 31–186 U/L) and pathognomonic abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings (FIGURE 1) led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, for which he was admitted.

Fluid resuscitation and pain management were implemented, and over 3 days his diet was advanced from NPO to clear fluids to a full diet. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient developed increasing abdominal pain and worsening leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.6–22 K/mcL [reference range, 4.5–11 K/mcL]). Repeat CT and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for presumed necrotizing pancreatitis. The next day he developed acutely tender red to pink patches and nodules on his shins and medial lower legs (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pancreatic panniculitis

It’s theorized that the systemic release of trypsin from pancreatic cell destruction causes increased capillary permeability and subsequent escape of lipase from the circulation into the subcutaneous fat. This causes fat necrosis, saponification, and inflammation.3,4 Pancreatic panniculitis is demonstrated histologically as hollowed-out adipocytes with granular basophilic cytoplasm and displaced or absent nuclei—aptly named “ghostlike” adipocytes.3-6

Painful, erythematous nodules most commonly present on the distal lower extremities. Nodules may be found over the shins, posterior calves, and periarticular skin. Rarely, nodules may occur on the buttocks, abdomen, or intramedullary bone.7 In severe cases, nodules spontaneously may ulcerate and drain an oily brown, viscous material formed from necrotic adipocytes.1

Timing of the eruption of skin lesions is varied and may even precede abdominal pain. Lesions can involute and regress several weeks after the underlying etiology improves. With pancreatic carcinoma, there is a greater likelihood of persistence, atypical locations of involvement, ulcerations, and recurrences.7

The histologic features of pancreatic panniculitis and the assessment of the subcutaneous fat are paramount in diagnosis. A deep punch biopsy or incisional biopsy is necessary to reliably reach the depth of the subcutaneous tissue. In our patient, a deep punch biopsy from the lateral calf was performed at the suggestion of Dermatology, and histopathology revealed necrosis of fat lobules with calcium soap around necrotic lipocytes, consistent with pancreatic panniculitis (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

The differential diagnosis was broad due to the confounding factors of recent antibiotic use and worsening pancreatitis.

Cellulitis may present as a red patch and is common on the lower legs; it often is associated with skin pathogens including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Usually, symptoms are unilateral and associated with warmth to the touch, expanding borders, leukocytosis, and systemic symptoms.

Vasculitis, which is an inflammation of various sized vessels through immunologic or infectious processes, often manifests on the lower legs. The characteristic sign of small vessel vasculitis is nonblanching purpura or petechiae. There often is a preceding illness or medication that triggers immunoglobulin proliferation and off-target inflammation of the vessels. Associated symptoms include pain and pruritus.

Drug eruptions may present as red patches on the skin. Often the patches are scaly and red and have more widespread distribution than the lower legs. A history of exposure is important, but common inciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used only occasionally and are challenging to elicit in the history. Our patient did have known drug changes (ie, the introduction of meropenem) while hospitalized, but the morphology was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Treatment is directed to underlying disease

Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis primarily is supportive and directed toward treating the underlying pancreatic disease. Depending upon the underlying pancreatic diagnosis, surgical correction of anatomic or ductal anomalies or pseudocysts may lead to resolution of panniculitis.3,7,8

Continue to: In this case

In this case, our patient had already received fluid resuscitation and pain management, and his diet had been advanced. In addition, his antibiotics were changed to exclude drug eruption as a cause. Over the course of a week, our patient saw a reduction in his pain level and an improvement in the appearance of his legs (FIGURE 4).

His pancreatitis, however, continued to persist and resist increases in his diet. He ultimately required transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of interventional options including stenting. The patient ultimately recovered, after stenting of the main pancreatic duct, and was discharged home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; Jonathan.Karnes@mainegeneral.org

A 58-year-old white man with a history of alcoholism presented to the emergency department with epigastric and right upper quadrant pain radiating to the back, as well as emesis and anorexia. An elevated lipase of 16,609 U/L (reference range, 31–186 U/L) and pathognomonic abdominal computed tomography (CT) findings (FIGURE 1) led to the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis, for which he was admitted.

Fluid resuscitation and pain management were implemented, and over 3 days his diet was advanced from NPO to clear fluids to a full diet. On the sixth day of hospitalization, the patient developed increasing abdominal pain and worsening leukocytosis (white blood cell count, 16.6–22 K/mcL [reference range, 4.5–11 K/mcL]). Repeat CT and blood cultures were obtained, and the patient was started on intravenous meropenem 1 g every 8 hours for presumed necrotizing pancreatitis. The next day he developed acutely tender red to pink patches and nodules on his shins and medial lower legs (FIGURE 2).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Pancreatic panniculitis

It’s theorized that the systemic release of trypsin from pancreatic cell destruction causes increased capillary permeability and subsequent escape of lipase from the circulation into the subcutaneous fat. This causes fat necrosis, saponification, and inflammation.3,4 Pancreatic panniculitis is demonstrated histologically as hollowed-out adipocytes with granular basophilic cytoplasm and displaced or absent nuclei—aptly named “ghostlike” adipocytes.3-6

Painful, erythematous nodules most commonly present on the distal lower extremities. Nodules may be found over the shins, posterior calves, and periarticular skin. Rarely, nodules may occur on the buttocks, abdomen, or intramedullary bone.7 In severe cases, nodules spontaneously may ulcerate and drain an oily brown, viscous material formed from necrotic adipocytes.1

Timing of the eruption of skin lesions is varied and may even precede abdominal pain. Lesions can involute and regress several weeks after the underlying etiology improves. With pancreatic carcinoma, there is a greater likelihood of persistence, atypical locations of involvement, ulcerations, and recurrences.7

The histologic features of pancreatic panniculitis and the assessment of the subcutaneous fat are paramount in diagnosis. A deep punch biopsy or incisional biopsy is necessary to reliably reach the depth of the subcutaneous tissue. In our patient, a deep punch biopsy from the lateral calf was performed at the suggestion of Dermatology, and histopathology revealed necrosis of fat lobules with calcium soap around necrotic lipocytes, consistent with pancreatic panniculitis (FIGURE 3).

Continue to: Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

Differential was complicated by antibiotic use

The differential diagnosis was broad due to the confounding factors of recent antibiotic use and worsening pancreatitis.

Cellulitis may present as a red patch and is common on the lower legs; it often is associated with skin pathogens including Staphylococcus and Streptococcus. Usually, symptoms are unilateral and associated with warmth to the touch, expanding borders, leukocytosis, and systemic symptoms.

Vasculitis, which is an inflammation of various sized vessels through immunologic or infectious processes, often manifests on the lower legs. The characteristic sign of small vessel vasculitis is nonblanching purpura or petechiae. There often is a preceding illness or medication that triggers immunoglobulin proliferation and off-target inflammation of the vessels. Associated symptoms include pain and pruritus.

Drug eruptions may present as red patches on the skin. Often the patches are scaly and red and have more widespread distribution than the lower legs. A history of exposure is important, but common inciting drugs include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that may be used only occasionally and are challenging to elicit in the history. Our patient did have known drug changes (ie, the introduction of meropenem) while hospitalized, but the morphology was not consistent with this diagnosis.

Treatment is directed to underlying disease

Treatment of pancreatic panniculitis primarily is supportive and directed toward treating the underlying pancreatic disease. Depending upon the underlying pancreatic diagnosis, surgical correction of anatomic or ductal anomalies or pseudocysts may lead to resolution of panniculitis.3,7,8

Continue to: In this case

In this case, our patient had already received fluid resuscitation and pain management, and his diet had been advanced. In addition, his antibiotics were changed to exclude drug eruption as a cause. Over the course of a week, our patient saw a reduction in his pain level and an improvement in the appearance of his legs (FIGURE 4).

His pancreatitis, however, continued to persist and resist increases in his diet. He ultimately required transfer to a tertiary care center for consideration of interventional options including stenting. The patient ultimately recovered, after stenting of the main pancreatic duct, and was discharged home.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; Jonathan.Karnes@mainegeneral.org

1. Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 2):331-334.

3. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

4. Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

5. Förström TL, Winkelmann RK. Acute, generalized panniculitis with amylase and lipase in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:497-502.

6. Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:506-510.

7. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

8. Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chro nic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835-1837.

1. Madarasingha NP, Satgurunathan K, Fernando R. Pancreatic panniculitis: a rare form of panniculitis. Dermatol Online J. 2009;15:17.

2. Haber RM, Assaad DM. Panniculitis associated with a pancreas divisum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1986;14(2 pt 2):331-334.

3. Requena L, Sánchez Yus E. Panniculitis. part II. mostly lobular panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:325-361.

4. Rongioletti F, Caputo V. Pancreatic panniculitis. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 2013;148:419-425.

5. Förström TL, Winkelmann RK. Acute, generalized panniculitis with amylase and lipase in skin. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:497-502.

6. Hughes SH, Apisarnthanarax P, Mullins F. Subcutaneous fat necrosis associated with pancreatic disease. Arch Dermatol. 1975;111:506-510.

7. Dahl PR, Su WP, Cullimore KC, et al. Pancreatic panniculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;33:413-417.

8. Lambiase P, Seery JP, Taylor-Robinson SD, et al. Resolution of panniculitis after placement of pancreatic duct stent in chro nic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1835-1837.

Large plaques on a baby boy

A 25-year-old G2P1 mother gave birth to a boy at 40 and 6/7 weeks by vaginal delivery. Labor was induced because of oligohydramnios complicated by chorioamnionitis. The mother was treated with vancomycin and gentamicin. Prenatal lab work and delivery were otherwise unremarkable.

The delivering physician (CG) noted that the neonate had numerous brown, red, and black plaques distributed over his abdomen, lower back, groin, and thighs (FIGURE). Some plaques were hypertrichotic and other areas, apart from the plaques, were thinly desquamated. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 and the remainder of the exam, including the neurologic exam, was normal. The Dermatology Service (JK) was consulted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Giant congenital nevus

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are pigmented lesions that are present at birth and created by the abnormal migration of neural crest cells during embryogenesis.1 Nevi are categorized by size as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-20 cm), large (>20 cm), and giant (>40 cm).2 Congenital nevi tend to start out flat, with uniform pigmentation, but can become more variegated in texture and color as normal growth and development continue. Giant congenital nevi are likely to thicken, darken, and enlarge as the patient grows. Some nevi may develop very coarse or dark hair.

CMN can cover any part of the body and occur independent of skin color and other ethnic factors.3 Giant congenital nevi are rare, with an incidence of approximately one in 50,000 live births and with males and females equally affected.3,4 The condition is diagnosed at birth, based on the appearance of the lesions.

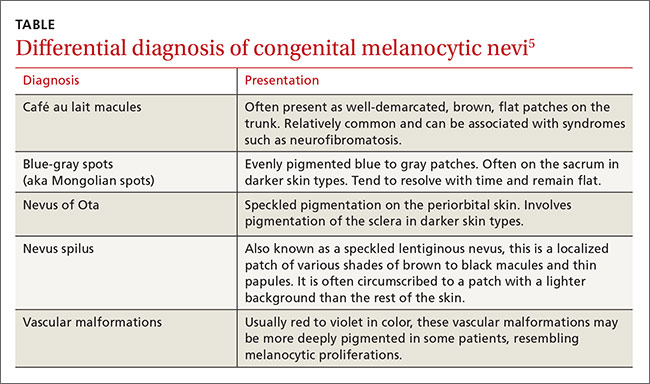

The differential diagnosis for CMN includes café au lait macules, blue-gray spots (aka Mongolian spots), nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations (TABLE).5 CMN may present in almost any location and may be brown, black, pink, or purple in color. Café au lait macules, blue-gray spots, nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations have individual location and color characteristics that set them apart clinically.

Monitor patients for melanoma, CNS complications

Patients with CMN are at increased risk of neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) and cutaneous melanoma.

Neurocutaneous melanosis, a complication of giant congenital nevi, is a melanocyte proliferation in the central nervous system (CNS). Between 6% and 11% of patients with giant congenital nevi develop symptomatic NCM in childhood. Thus, any CNS symptoms should be fully evaluated.4,6 NCM can result in seizures, cranial nerve palsy, hydrocephalus, and leptomeningeal melanoma.

Besides giant congenital nevi, risk factors for NCM include male sex, large numbers of satellite nevi, and the presence of nevi over the posterior midline or head and neck.7 The prognosis is poor for patients who develop neurologic symptoms. NCM is associated with other malignancies, including rhadomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful to exclude NCM. Ideally, an MRI should be ordered before 4 months of age, at which time myelination begins to make the identification of melanin deposits in the CNS more challenging.7 Not all patients with imaging findings that are consistent with NCM will develop symptoms.8

Melanoma. By age 10, up to 8% of patients with giant congenital nevi will develop melanoma within the nevi; most of these cases occur during the first 2 years of life.7,9 Patients with NCM are at even greater risk: their rate of malignant melanoma is between 40% and 60%.6 As a result, patients should be monitored closely for any signs of the disease. Total body photography, serial clinical photos, and patient self-exam are helpful to detect changes and de novo lesions. New lesions or ulcerations superimposed on existing nevi may indicate malignancy.7 Sun protection is critical to reduce the risk of melanogenesis.

Should patients pursue surgery? It’s debatable

Options for patients with large and giant CMN include early curettage (prior to 2 weeks of life), local excision (often with tissue expansion), dermabrasion, and laser therapy.2 There is considerable debate about surgery. Advocates of surgery cite psychosocial relief as a major treatment benefit and speculate about prevention of melanoma. Opponents worry that excessive surgical intervention may cause melanogenesis in a scar or deep in an area of treatment. And, while smaller congenital nevi are easier to surgically remove, they have a low associated risk of developing melanoma and are typically monitored clinically.

Children with congenital nevi will need support

Several nonprofit organizations offer resources for children with congenital nevi and their families. Nevus Outreach (www.nevus.org) is an organization devoted to improving awareness and providing support for people with CMN and NCM. The group maintains a registry of patients with large nevi in an effort to help researchers improve treatment and identify a cure.

For children with congenital nevi and other skin conditions, the American Academy of Dermatology offers its “Camp Discovery” at locations across the country (https://www.aad.org/public/kids/camp-discovery). Camp Discovery provides full scholarships and includes transportation to each of the individual camps for attendees.

Our patient underwent an MRI on his fifth day of life. The results were normal and he hadn’t developed any neurologic symptoms at 4 months of age. The child sees his family physician for routine well-child visits and a dermatologist annually. The dermatologist is carefully monitoring the nevi, which continue to grow.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Suite 340, Augusta, ME 04330; jonathan.karnes@mainegeneral.org.

1. Sarnat HB, Flores-Sarnat L. Embryology of the neural crest: its inductive role in the neurocutaneous syndromes. J Child Neurol. 2005:20:637-643.

2. Gosain AK, Santoro TD, Larson DL, et al. Giant congenital nevi: a 20-year experience and an algorithm for their management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:622-636.

3. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Giant congenital melanocytic nevus. National Organization for Rare Disorders Web site. Available at: http://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/giant-congenital-melanocytic-nevus. Accessed April 29, 2016.

4. Vourc’h-Jourdain M, Martin L, Barbarot S; aRED. Large congenital melanocytic nevi: therapeutic management and melanoma risk: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:493-498.e1-e14.

5. Jackson SM, Nesbitt LT. Differential Diagnosis for the Dermatologist. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2012.

6. Jain P, Kannan L, Kumar A, et al. Symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis in a child. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:516.

7. Kinsler VA, Chong WK, Aylett SE, et al. Complications of congenital melanocytic naevi in children: analysis of 16 years’ experience and clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:907-914.

8. Agero AL, B envenuto-Andrade C, Dusza SW, et al. Asymptomatic neurocutaneous melanocytosis in patients with large congenital melanocytic nevi: a study of cases from an Internet-based registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:959-965.

9. Zayour M, Lazova R. Congenital melanocytic nevi. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:267-280.

A 25-year-old G2P1 mother gave birth to a boy at 40 and 6/7 weeks by vaginal delivery. Labor was induced because of oligohydramnios complicated by chorioamnionitis. The mother was treated with vancomycin and gentamicin. Prenatal lab work and delivery were otherwise unremarkable.

The delivering physician (CG) noted that the neonate had numerous brown, red, and black plaques distributed over his abdomen, lower back, groin, and thighs (FIGURE). Some plaques were hypertrichotic and other areas, apart from the plaques, were thinly desquamated. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 and the remainder of the exam, including the neurologic exam, was normal. The Dermatology Service (JK) was consulted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Giant congenital nevus

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are pigmented lesions that are present at birth and created by the abnormal migration of neural crest cells during embryogenesis.1 Nevi are categorized by size as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-20 cm), large (>20 cm), and giant (>40 cm).2 Congenital nevi tend to start out flat, with uniform pigmentation, but can become more variegated in texture and color as normal growth and development continue. Giant congenital nevi are likely to thicken, darken, and enlarge as the patient grows. Some nevi may develop very coarse or dark hair.

CMN can cover any part of the body and occur independent of skin color and other ethnic factors.3 Giant congenital nevi are rare, with an incidence of approximately one in 50,000 live births and with males and females equally affected.3,4 The condition is diagnosed at birth, based on the appearance of the lesions.

The differential diagnosis for CMN includes café au lait macules, blue-gray spots (aka Mongolian spots), nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations (TABLE).5 CMN may present in almost any location and may be brown, black, pink, or purple in color. Café au lait macules, blue-gray spots, nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations have individual location and color characteristics that set them apart clinically.

Monitor patients for melanoma, CNS complications

Patients with CMN are at increased risk of neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) and cutaneous melanoma.

Neurocutaneous melanosis, a complication of giant congenital nevi, is a melanocyte proliferation in the central nervous system (CNS). Between 6% and 11% of patients with giant congenital nevi develop symptomatic NCM in childhood. Thus, any CNS symptoms should be fully evaluated.4,6 NCM can result in seizures, cranial nerve palsy, hydrocephalus, and leptomeningeal melanoma.

Besides giant congenital nevi, risk factors for NCM include male sex, large numbers of satellite nevi, and the presence of nevi over the posterior midline or head and neck.7 The prognosis is poor for patients who develop neurologic symptoms. NCM is associated with other malignancies, including rhadomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful to exclude NCM. Ideally, an MRI should be ordered before 4 months of age, at which time myelination begins to make the identification of melanin deposits in the CNS more challenging.7 Not all patients with imaging findings that are consistent with NCM will develop symptoms.8

Melanoma. By age 10, up to 8% of patients with giant congenital nevi will develop melanoma within the nevi; most of these cases occur during the first 2 years of life.7,9 Patients with NCM are at even greater risk: their rate of malignant melanoma is between 40% and 60%.6 As a result, patients should be monitored closely for any signs of the disease. Total body photography, serial clinical photos, and patient self-exam are helpful to detect changes and de novo lesions. New lesions or ulcerations superimposed on existing nevi may indicate malignancy.7 Sun protection is critical to reduce the risk of melanogenesis.

Should patients pursue surgery? It’s debatable

Options for patients with large and giant CMN include early curettage (prior to 2 weeks of life), local excision (often with tissue expansion), dermabrasion, and laser therapy.2 There is considerable debate about surgery. Advocates of surgery cite psychosocial relief as a major treatment benefit and speculate about prevention of melanoma. Opponents worry that excessive surgical intervention may cause melanogenesis in a scar or deep in an area of treatment. And, while smaller congenital nevi are easier to surgically remove, they have a low associated risk of developing melanoma and are typically monitored clinically.

Children with congenital nevi will need support

Several nonprofit organizations offer resources for children with congenital nevi and their families. Nevus Outreach (www.nevus.org) is an organization devoted to improving awareness and providing support for people with CMN and NCM. The group maintains a registry of patients with large nevi in an effort to help researchers improve treatment and identify a cure.

For children with congenital nevi and other skin conditions, the American Academy of Dermatology offers its “Camp Discovery” at locations across the country (https://www.aad.org/public/kids/camp-discovery). Camp Discovery provides full scholarships and includes transportation to each of the individual camps for attendees.

Our patient underwent an MRI on his fifth day of life. The results were normal and he hadn’t developed any neurologic symptoms at 4 months of age. The child sees his family physician for routine well-child visits and a dermatologist annually. The dermatologist is carefully monitoring the nevi, which continue to grow.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Suite 340, Augusta, ME 04330; jonathan.karnes@mainegeneral.org.

A 25-year-old G2P1 mother gave birth to a boy at 40 and 6/7 weeks by vaginal delivery. Labor was induced because of oligohydramnios complicated by chorioamnionitis. The mother was treated with vancomycin and gentamicin. Prenatal lab work and delivery were otherwise unremarkable.

The delivering physician (CG) noted that the neonate had numerous brown, red, and black plaques distributed over his abdomen, lower back, groin, and thighs (FIGURE). Some plaques were hypertrichotic and other areas, apart from the plaques, were thinly desquamated. Apgar scores were 8 and 9 and the remainder of the exam, including the neurologic exam, was normal. The Dermatology Service (JK) was consulted.

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Giant congenital nevus

Congenital melanocytic nevi (CMN) are pigmented lesions that are present at birth and created by the abnormal migration of neural crest cells during embryogenesis.1 Nevi are categorized by size as small (<1.5 cm), medium (1.5-20 cm), large (>20 cm), and giant (>40 cm).2 Congenital nevi tend to start out flat, with uniform pigmentation, but can become more variegated in texture and color as normal growth and development continue. Giant congenital nevi are likely to thicken, darken, and enlarge as the patient grows. Some nevi may develop very coarse or dark hair.

CMN can cover any part of the body and occur independent of skin color and other ethnic factors.3 Giant congenital nevi are rare, with an incidence of approximately one in 50,000 live births and with males and females equally affected.3,4 The condition is diagnosed at birth, based on the appearance of the lesions.

The differential diagnosis for CMN includes café au lait macules, blue-gray spots (aka Mongolian spots), nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations (TABLE).5 CMN may present in almost any location and may be brown, black, pink, or purple in color. Café au lait macules, blue-gray spots, nevus of Ota, nevus spilus, and vascular malformations have individual location and color characteristics that set them apart clinically.

Monitor patients for melanoma, CNS complications

Patients with CMN are at increased risk of neurocutaneous melanosis (NCM) and cutaneous melanoma.

Neurocutaneous melanosis, a complication of giant congenital nevi, is a melanocyte proliferation in the central nervous system (CNS). Between 6% and 11% of patients with giant congenital nevi develop symptomatic NCM in childhood. Thus, any CNS symptoms should be fully evaluated.4,6 NCM can result in seizures, cranial nerve palsy, hydrocephalus, and leptomeningeal melanoma.

Besides giant congenital nevi, risk factors for NCM include male sex, large numbers of satellite nevi, and the presence of nevi over the posterior midline or head and neck.7 The prognosis is poor for patients who develop neurologic symptoms. NCM is associated with other malignancies, including rhadomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors.4

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is helpful to exclude NCM. Ideally, an MRI should be ordered before 4 months of age, at which time myelination begins to make the identification of melanin deposits in the CNS more challenging.7 Not all patients with imaging findings that are consistent with NCM will develop symptoms.8

Melanoma. By age 10, up to 8% of patients with giant congenital nevi will develop melanoma within the nevi; most of these cases occur during the first 2 years of life.7,9 Patients with NCM are at even greater risk: their rate of malignant melanoma is between 40% and 60%.6 As a result, patients should be monitored closely for any signs of the disease. Total body photography, serial clinical photos, and patient self-exam are helpful to detect changes and de novo lesions. New lesions or ulcerations superimposed on existing nevi may indicate malignancy.7 Sun protection is critical to reduce the risk of melanogenesis.

Should patients pursue surgery? It’s debatable

Options for patients with large and giant CMN include early curettage (prior to 2 weeks of life), local excision (often with tissue expansion), dermabrasion, and laser therapy.2 There is considerable debate about surgery. Advocates of surgery cite psychosocial relief as a major treatment benefit and speculate about prevention of melanoma. Opponents worry that excessive surgical intervention may cause melanogenesis in a scar or deep in an area of treatment. And, while smaller congenital nevi are easier to surgically remove, they have a low associated risk of developing melanoma and are typically monitored clinically.

Children with congenital nevi will need support

Several nonprofit organizations offer resources for children with congenital nevi and their families. Nevus Outreach (www.nevus.org) is an organization devoted to improving awareness and providing support for people with CMN and NCM. The group maintains a registry of patients with large nevi in an effort to help researchers improve treatment and identify a cure.

For children with congenital nevi and other skin conditions, the American Academy of Dermatology offers its “Camp Discovery” at locations across the country (https://www.aad.org/public/kids/camp-discovery). Camp Discovery provides full scholarships and includes transportation to each of the individual camps for attendees.

Our patient underwent an MRI on his fifth day of life. The results were normal and he hadn’t developed any neurologic symptoms at 4 months of age. The child sees his family physician for routine well-child visits and a dermatologist annually. The dermatologist is carefully monitoring the nevi, which continue to grow.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, 6 East Chestnut Street, Suite 340, Augusta, ME 04330; jonathan.karnes@mainegeneral.org.

1. Sarnat HB, Flores-Sarnat L. Embryology of the neural crest: its inductive role in the neurocutaneous syndromes. J Child Neurol. 2005:20:637-643.

2. Gosain AK, Santoro TD, Larson DL, et al. Giant congenital nevi: a 20-year experience and an algorithm for their management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:622-636.

3. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Giant congenital melanocytic nevus. National Organization for Rare Disorders Web site. Available at: http://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/giant-congenital-melanocytic-nevus. Accessed April 29, 2016.

4. Vourc’h-Jourdain M, Martin L, Barbarot S; aRED. Large congenital melanocytic nevi: therapeutic management and melanoma risk: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:493-498.e1-e14.

5. Jackson SM, Nesbitt LT. Differential Diagnosis for the Dermatologist. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2012.

6. Jain P, Kannan L, Kumar A, et al. Symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis in a child. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:516.

7. Kinsler VA, Chong WK, Aylett SE, et al. Complications of congenital melanocytic naevi in children: analysis of 16 years’ experience and clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:907-914.

8. Agero AL, B envenuto-Andrade C, Dusza SW, et al. Asymptomatic neurocutaneous melanocytosis in patients with large congenital melanocytic nevi: a study of cases from an Internet-based registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:959-965.

9. Zayour M, Lazova R. Congenital melanocytic nevi. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:267-280.

1. Sarnat HB, Flores-Sarnat L. Embryology of the neural crest: its inductive role in the neurocutaneous syndromes. J Child Neurol. 2005:20:637-643.

2. Gosain AK, Santoro TD, Larson DL, et al. Giant congenital nevi: a 20-year experience and an algorithm for their management. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:622-636.

3. National Organization for Rare Disorders. Giant congenital melanocytic nevus. National Organization for Rare Disorders Web site. Available at: http://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/giant-congenital-melanocytic-nevus. Accessed April 29, 2016.

4. Vourc’h-Jourdain M, Martin L, Barbarot S; aRED. Large congenital melanocytic nevi: therapeutic management and melanoma risk: a systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;68:493-498.e1-e14.

5. Jackson SM, Nesbitt LT. Differential Diagnosis for the Dermatologist. 2nd ed. Berlin: Springer; 2012.

6. Jain P, Kannan L, Kumar A, et al. Symptomatic neurocutaneous melanosis in a child. JAMA Neurol. 2013;70:516.

7. Kinsler VA, Chong WK, Aylett SE, et al. Complications of congenital melanocytic naevi in children: analysis of 16 years’ experience and clinical practice. Br J Dermatol. 2008;159:907-914.

8. Agero AL, B envenuto-Andrade C, Dusza SW, et al. Asymptomatic neurocutaneous melanocytosis in patients with large congenital melanocytic nevi: a study of cases from an Internet-based registry. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:959-965.

9. Zayour M, Lazova R. Congenital melanocytic nevi. Clin Lab Med. 2011;31:267-280.

Plaques on dorsal hands & arms

A 45-year-old woman sought treatment for plaques that she’d had on the top of her hands for 6 months (FIGURE 1). These plaques had been getting larger, and new papules and plaques were now developing on the dorsal arms. She’d first noticed the lesions after unpacking some crates from overseas while working at a hardware store. She’d applied unspecified types and dosages of topical steroids and antifungals, but her condition hadn’t improved. We performed a punch biopsy of a lesion on her arm.

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Chromoblastomycosis

The punch biopsy revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses (FIGURE 2), which was consistent with chromoblastomycosis. Two additional biopsies taken from plaques on the patient’s arm grew Phialophora verrucosa, confirming the diagnosis. We assumed she contracted chromoblastomycosis from her exposure to the overseas crates at her job, but we could not confirm this. However, there were no other likely sources of infection.

Differential Dx includes BCC and sarcoidosis

Superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC).3 Like chromoblastomycosis, BCC has a similar history of slow-growing scaly plaques. With BCC, there is usually a solitary plaque, although it may be large. Biopsy would distinguish BCC from chromoblastomycosis.

Sarcoidosis.3,4 The plaques of sarcoidosis are less scaly than those of chromoblastomycosis and biopsy would show granulomatous process. Sarcoidosis may also be associated with respiratory symptoms, elevated angiotensin converting enzyme, or hilar nodules on chest x-ray.

Plaque-type porokeratosis.4 Porokera-tosis is an inherited or acquired solitary lesion that is annular, round, and thin with raised edges; it often develops on the lower legs. What triggers its appearance is unknown, though trauma and photodamage have been suggested. In some variants, it may appear similar to chromoblastomycosis.

Cellulitis. In cellulitis, the advancing edge of erythema changes over days instead of months to years (as chromoblastomycosis does). Possible systemic symptoms of cellulitis include pain, fever, swelling, or malaise.

Cutaneous tuberculosis.3 Although rare, cutaneous tuberculosis, which often presents as firm, shallow ulcers with a granular base, may be associated with significant discomfort. It can persist for up to a year, is more likely to form an abscess and drain, and is associated with lymphadenopathy after several weeks.

Sporotrichosis.3 The appearance of sporotrichosis is similar to that of chromoblastomycosis, with hematogenous spread that may mimic autoinoculation. Biopsy and tissue culture would differentiate sporotrichosis from chromoblastomycosis.

Tissue culture clinches the Dx

Diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis is often delayed because of the slow-growing nature of the plaques, its few initial symptoms, and the rarity of the condition in nonendemic regions.1,2 A skin scraping may demonstrate hyphae or spores. On histology, clusters of brown spores (“copper pennies”) are pathognomonic.5 A biopsy and tissue culture establish the diagnosis. The most frequent organisms identified include Phialophora, Fonsecaea, and Cladosporium.1

More than one type of treatment may be necessary

Chromoblastomycosis is often extremely difficult to treat; frequent recurrences may require multimodal therapy.6,7 Treatment options include pharmacotherapy, surgery, and destructive therapy.

Systemic antifungals are the mainstay of therapy because topical antifungals do not penetrate deep enough in the skin. Several regimens have been presented in the literature. A common starting point is oral terbinafine8 250 to 500 mg/d and itraconazole9 200 mg to 400 mg/d for 6 to 12 months. Another medication used to treat chromoblastomycosis is intralesional or intravenous amphotericin B dosed variably with or without 5-flucytosine until the plaques clear.10 Based on small trials, treatment efficacy with antifungals ranges from 70% to 90%.6,7 Treatment often is limited by medication interactions and adverse effects.

Surgical therapy. A solitary plaque or smaller plaques may be removed with good outcomes. However, plaques may be so large that surgical removal is impractical or disfiguring.5,11

Destructive therapy. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or electrocautery may be used to destroy plaques. This approach may be used with or without pharmacotherapy.11

Our patient. Because chromoblastomycosis is rare in North America, we consulted with a dermatologist who worked in an endemic area. Our patient was also seen by an infectious disease specialist. For 9 months, she took oral terbinafine 500 mg/d and itraconazole 200 mg/d. Initially, the patient experienced modest improvement in the largest plaques, but they didn’t clear completely. Smaller lesions cleared with cryotherapy but new lesions developed on her ears. The patient’s lesions finally cleared after 12 months of therapy; 2 repeated cultures were also negative.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, Maine-Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, 15 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; jonathan.karnes@mainegeneral.org

1. Correia RT, Valente NY, Criado PR, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: study of 27 cases and review of medical literature. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:448-454.

2. Minotto R, Bernardi CD, Mallmann LF, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: a review of 100 cases in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:585-592.

3. Krzyściak PM, Pindycka-Piaszczyńska M, Piaszczyński M. Chromoblastomycosis. Postep Derm Alergol. 2014;31:310-321.

4. Long H, Zhang G, Lu Q. A persistent red crusted plaque on the back. JAMA. 2013;310:1730-1731.

5. Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

6. Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

7. Tuffanelli L, Millburn PB. Treatment of chromoblastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(4 pt 1):728-732.

8. Lamisil [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2001.

9. Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis treatment & management. Medscape Web site. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-treatment. Accessed February 19, 2015.

10. Poirriez J, Breuillard F, Francois N, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by a combination of cryotherapy, shaving, oral 5-fluorocystosine and oral amphotericin B. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:61-63.

11. Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

A 45-year-old woman sought treatment for plaques that she’d had on the top of her hands for 6 months (FIGURE 1). These plaques had been getting larger, and new papules and plaques were now developing on the dorsal arms. She’d first noticed the lesions after unpacking some crates from overseas while working at a hardware store. She’d applied unspecified types and dosages of topical steroids and antifungals, but her condition hadn’t improved. We performed a punch biopsy of a lesion on her arm.

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Chromoblastomycosis

The punch biopsy revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses (FIGURE 2), which was consistent with chromoblastomycosis. Two additional biopsies taken from plaques on the patient’s arm grew Phialophora verrucosa, confirming the diagnosis. We assumed she contracted chromoblastomycosis from her exposure to the overseas crates at her job, but we could not confirm this. However, there were no other likely sources of infection.

Differential Dx includes BCC and sarcoidosis

Superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC).3 Like chromoblastomycosis, BCC has a similar history of slow-growing scaly plaques. With BCC, there is usually a solitary plaque, although it may be large. Biopsy would distinguish BCC from chromoblastomycosis.

Sarcoidosis.3,4 The plaques of sarcoidosis are less scaly than those of chromoblastomycosis and biopsy would show granulomatous process. Sarcoidosis may also be associated with respiratory symptoms, elevated angiotensin converting enzyme, or hilar nodules on chest x-ray.

Plaque-type porokeratosis.4 Porokera-tosis is an inherited or acquired solitary lesion that is annular, round, and thin with raised edges; it often develops on the lower legs. What triggers its appearance is unknown, though trauma and photodamage have been suggested. In some variants, it may appear similar to chromoblastomycosis.

Cellulitis. In cellulitis, the advancing edge of erythema changes over days instead of months to years (as chromoblastomycosis does). Possible systemic symptoms of cellulitis include pain, fever, swelling, or malaise.

Cutaneous tuberculosis.3 Although rare, cutaneous tuberculosis, which often presents as firm, shallow ulcers with a granular base, may be associated with significant discomfort. It can persist for up to a year, is more likely to form an abscess and drain, and is associated with lymphadenopathy after several weeks.

Sporotrichosis.3 The appearance of sporotrichosis is similar to that of chromoblastomycosis, with hematogenous spread that may mimic autoinoculation. Biopsy and tissue culture would differentiate sporotrichosis from chromoblastomycosis.

Tissue culture clinches the Dx

Diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis is often delayed because of the slow-growing nature of the plaques, its few initial symptoms, and the rarity of the condition in nonendemic regions.1,2 A skin scraping may demonstrate hyphae or spores. On histology, clusters of brown spores (“copper pennies”) are pathognomonic.5 A biopsy and tissue culture establish the diagnosis. The most frequent organisms identified include Phialophora, Fonsecaea, and Cladosporium.1

More than one type of treatment may be necessary

Chromoblastomycosis is often extremely difficult to treat; frequent recurrences may require multimodal therapy.6,7 Treatment options include pharmacotherapy, surgery, and destructive therapy.

Systemic antifungals are the mainstay of therapy because topical antifungals do not penetrate deep enough in the skin. Several regimens have been presented in the literature. A common starting point is oral terbinafine8 250 to 500 mg/d and itraconazole9 200 mg to 400 mg/d for 6 to 12 months. Another medication used to treat chromoblastomycosis is intralesional or intravenous amphotericin B dosed variably with or without 5-flucytosine until the plaques clear.10 Based on small trials, treatment efficacy with antifungals ranges from 70% to 90%.6,7 Treatment often is limited by medication interactions and adverse effects.

Surgical therapy. A solitary plaque or smaller plaques may be removed with good outcomes. However, plaques may be so large that surgical removal is impractical or disfiguring.5,11

Destructive therapy. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or electrocautery may be used to destroy plaques. This approach may be used with or without pharmacotherapy.11

Our patient. Because chromoblastomycosis is rare in North America, we consulted with a dermatologist who worked in an endemic area. Our patient was also seen by an infectious disease specialist. For 9 months, she took oral terbinafine 500 mg/d and itraconazole 200 mg/d. Initially, the patient experienced modest improvement in the largest plaques, but they didn’t clear completely. Smaller lesions cleared with cryotherapy but new lesions developed on her ears. The patient’s lesions finally cleared after 12 months of therapy; 2 repeated cultures were also negative.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, Maine-Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, 15 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; jonathan.karnes@mainegeneral.org

A 45-year-old woman sought treatment for plaques that she’d had on the top of her hands for 6 months (FIGURE 1). These plaques had been getting larger, and new papules and plaques were now developing on the dorsal arms. She’d first noticed the lesions after unpacking some crates from overseas while working at a hardware store. She’d applied unspecified types and dosages of topical steroids and antifungals, but her condition hadn’t improved. We performed a punch biopsy of a lesion on her arm.

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Chromoblastomycosis

The punch biopsy revealed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia with intraepidermal microabscesses (FIGURE 2), which was consistent with chromoblastomycosis. Two additional biopsies taken from plaques on the patient’s arm grew Phialophora verrucosa, confirming the diagnosis. We assumed she contracted chromoblastomycosis from her exposure to the overseas crates at her job, but we could not confirm this. However, there were no other likely sources of infection.

Differential Dx includes BCC and sarcoidosis

Superficial basal cell carcinoma (BCC).3 Like chromoblastomycosis, BCC has a similar history of slow-growing scaly plaques. With BCC, there is usually a solitary plaque, although it may be large. Biopsy would distinguish BCC from chromoblastomycosis.

Sarcoidosis.3,4 The plaques of sarcoidosis are less scaly than those of chromoblastomycosis and biopsy would show granulomatous process. Sarcoidosis may also be associated with respiratory symptoms, elevated angiotensin converting enzyme, or hilar nodules on chest x-ray.

Plaque-type porokeratosis.4 Porokera-tosis is an inherited or acquired solitary lesion that is annular, round, and thin with raised edges; it often develops on the lower legs. What triggers its appearance is unknown, though trauma and photodamage have been suggested. In some variants, it may appear similar to chromoblastomycosis.

Cellulitis. In cellulitis, the advancing edge of erythema changes over days instead of months to years (as chromoblastomycosis does). Possible systemic symptoms of cellulitis include pain, fever, swelling, or malaise.

Cutaneous tuberculosis.3 Although rare, cutaneous tuberculosis, which often presents as firm, shallow ulcers with a granular base, may be associated with significant discomfort. It can persist for up to a year, is more likely to form an abscess and drain, and is associated with lymphadenopathy after several weeks.

Sporotrichosis.3 The appearance of sporotrichosis is similar to that of chromoblastomycosis, with hematogenous spread that may mimic autoinoculation. Biopsy and tissue culture would differentiate sporotrichosis from chromoblastomycosis.

Tissue culture clinches the Dx

Diagnosis of chromoblastomycosis is often delayed because of the slow-growing nature of the plaques, its few initial symptoms, and the rarity of the condition in nonendemic regions.1,2 A skin scraping may demonstrate hyphae or spores. On histology, clusters of brown spores (“copper pennies”) are pathognomonic.5 A biopsy and tissue culture establish the diagnosis. The most frequent organisms identified include Phialophora, Fonsecaea, and Cladosporium.1

More than one type of treatment may be necessary

Chromoblastomycosis is often extremely difficult to treat; frequent recurrences may require multimodal therapy.6,7 Treatment options include pharmacotherapy, surgery, and destructive therapy.

Systemic antifungals are the mainstay of therapy because topical antifungals do not penetrate deep enough in the skin. Several regimens have been presented in the literature. A common starting point is oral terbinafine8 250 to 500 mg/d and itraconazole9 200 mg to 400 mg/d for 6 to 12 months. Another medication used to treat chromoblastomycosis is intralesional or intravenous amphotericin B dosed variably with or without 5-flucytosine until the plaques clear.10 Based on small trials, treatment efficacy with antifungals ranges from 70% to 90%.6,7 Treatment often is limited by medication interactions and adverse effects.

Surgical therapy. A solitary plaque or smaller plaques may be removed with good outcomes. However, plaques may be so large that surgical removal is impractical or disfiguring.5,11

Destructive therapy. Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen or electrocautery may be used to destroy plaques. This approach may be used with or without pharmacotherapy.11

Our patient. Because chromoblastomycosis is rare in North America, we consulted with a dermatologist who worked in an endemic area. Our patient was also seen by an infectious disease specialist. For 9 months, she took oral terbinafine 500 mg/d and itraconazole 200 mg/d. Initially, the patient experienced modest improvement in the largest plaques, but they didn’t clear completely. Smaller lesions cleared with cryotherapy but new lesions developed on her ears. The patient’s lesions finally cleared after 12 months of therapy; 2 repeated cultures were also negative.

CORRESPONDENCE

Jonathan Karnes, MD, Maine-Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency, 15 East Chestnut Street, Augusta, ME 04330; jonathan.karnes@mainegeneral.org

1. Correia RT, Valente NY, Criado PR, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: study of 27 cases and review of medical literature. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:448-454.

2. Minotto R, Bernardi CD, Mallmann LF, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: a review of 100 cases in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:585-592.

3. Krzyściak PM, Pindycka-Piaszczyńska M, Piaszczyński M. Chromoblastomycosis. Postep Derm Alergol. 2014;31:310-321.

4. Long H, Zhang G, Lu Q. A persistent red crusted plaque on the back. JAMA. 2013;310:1730-1731.

5. Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

6. Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

7. Tuffanelli L, Millburn PB. Treatment of chromoblastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(4 pt 1):728-732.

8. Lamisil [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2001.

9. Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis treatment & management. Medscape Web site. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-treatment. Accessed February 19, 2015.

10. Poirriez J, Breuillard F, Francois N, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by a combination of cryotherapy, shaving, oral 5-fluorocystosine and oral amphotericin B. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:61-63.

11. Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.

1. Correia RT, Valente NY, Criado PR, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: study of 27 cases and review of medical literature. An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:448-454.

2. Minotto R, Bernardi CD, Mallmann LF, et al. Chromoblastomycosis: a review of 100 cases in the state of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:585-592.

3. Krzyściak PM, Pindycka-Piaszczyńska M, Piaszczyński M. Chromoblastomycosis. Postep Derm Alergol. 2014;31:310-321.

4. Long H, Zhang G, Lu Q. A persistent red crusted plaque on the back. JAMA. 2013;310:1730-1731.

5. Ameen M. Managing chromoblastomycosis. Trop Doct. 2010;40:65-67.

6. Torres-Guerrero E, Isa-Isa R, Isa M, et al. Chromoblastomycosis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:403-408.

7. Tuffanelli L, Millburn PB. Treatment of chromoblastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1990;23(4 pt 1):728-732.

8. Lamisil [package insert]. East Hanover, NJ: Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; 2001.

9. Schwartz RA. Chromoblastomycosis treatment & management. Medscape Web site. Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1092695-treatment. Accessed February 19, 2015.

10. Poirriez J, Breuillard F, Francois N, et al. A case of chromomycosis treated by a combination of cryotherapy, shaving, oral 5-fluorocystosine and oral amphotericin B. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2000;63:61-63.

11. Ameen M. Chromoblastomycosis: clinical presentation and management. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2009;34:849-854.