User login

Readmissions after Pediatric Hospitalization for Suicide Ideation and Suicide Attempt

Suicide is a leading cause of death among 10- to 34-year-olds in the United States.1,2 During the past two decades, the youth suicide death rate has risen by 24%, and more than 5,000 young people die from suicide each year.3 Suicide ideation (SI) and suicide attempts (SAs) are well-established risk factors for suicide death and a source of morbidity for patients and families. One-third of youth with SI attempt suicide at some point in their lifetime.4 Approximately 11% of youth SAs result in suicide death, and 2% of youth who attempt suicide subsequently go on to die from suicide after recovering from a prior SA.5 More than 60,000 youth are hospitalized for SI or SA each year,6 and young people hospitalized for SA are at high short-term risk of repeat SA and suicide death.7 Hospitals need strategies for measuring the quality of SI and SA hospitalizations, monitoring postdischarge outcomes, and identifying the patients at the highest risk of poor outcomes. Readmissions are a useful hospital quality measure that can indicate re-emergence of SI, repeat SA, or inadequate community-based mental health treatment, and interventions designed for patients with readmissions can potentially avert morbidity or mortality.

The National Committee on Quality Assurance recommends measurement of quality metrics for 30-day mental health follow-up after psychiatric hospitalizations, 30-day readmissions after adult (but not pediatric) psychiatric hospitalizations, and 30-day readmissions in pediatric medical and surgical hospitalizations. Readmission measures are not consistently used to evaluate pediatric psychiatric hospitalizations, and psychiatric quality measures are not used to evaluate medical or surgical hospitalizations for SA. Recent research has investigated transfers to postacute care,8 readmission prevalence, variation in hospital readmission performance, and risk factors for readmissions after pediatric psychiatric hospitalizations.9–11 However, no national study has investigated 30-day readmissions in youth hospitalized specifically for SI or SA.

To inform hospital quality measurement and improve hospital and postdischarge care for youth at risk of suicide, more information is needed about the characteristics of and the risk factors for readmissions after index SI/SA hospitalization. To address this knowledge gap, among SI/SA hospitalizations in 6- to 17-year-olds, we examined (1) unplanned 30-day readmissions and characteristics of hospitalizations by 30-day readmission status; (2) patient, hospital, and regional characteristics associated with 30-day readmissions; and (3) characteristics of 30-day readmissions.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a national, retrospective cohort study of hospitalizations for patients aged 6-17 years using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) 2013 and 2014 Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). The combined 2013-2014 NRD includes administrative data from a nationally representative sample of 29 million hospitalizations in 22 states, accounting for 49.3% of all US hospitalizations, and is weighted for national projections. The NRD includes hospital information, patient demographic information, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis, procedure, and external cause of injury codes (E-codes). The database includes one primary diagnosis, up to 24 additional diagnoses, and up to 4 E-codes for each hospitalization. The NRD includes information about hospitalizations in acute-care general hospitals (including their psychiatric units) but not from specialty psychiatric hospitals. The database also includes de-identified, verified patient linkage numbers so that patients can be tracked across multiple hospitalizations at the same institution or different institutions within the same state. This study was considered to be exempt from review by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board.

Sample

We identified a sample of 181,575 hospitalizations for SI (n = 119,037) or SA (n = 62,538) among 6- to 17-year-olds between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2014 (Figure). We included children as young as 6 years because validated methods exist to identify SI and SA in this age group,12 and because suicide deaths have recently increased among younger children.3 We excluded patients aged 18 years and older from this study since delivery of mental health services differs for adults.13 To create the sample, we first identified all hospitalizations of patients aged 6-17 years. We then used a validated algorithm relying on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for poisonings and E-codes for self-injury (E950-959) to identify hospitalizations related to SA.12 Because E-code completeness varies among states,14 we also used the combination of having both a diagnosis code for injury (800-999) and an ICD-9-CM code for SI (V62.84) as a proxy for SA. Among hospitalizations without SA, we identified hospitalizations with SI using the ICD-9-CM code for SI (V62.84) in any position.

We identified 133,516 index hospitalizations with complete data at risk for an unplanned readmission. Because NRD data cannot be linked between calendar years, we limited the study time period for each calendar year to 10 months. We excluded hospitalizations in January because the full 30-day time frame to determine whether a hospitalization had occurred in the preceding 30 days, a known risk factor for readmissions in other samples,15 was not available. We excluded index hospitalizations occurring in December, because the full 30-day time frame to ascertain readmissions was not available. We excluded hospitalizations resulting in death, since these are not at risk for readmission, and hospitalizations resulting in transfer, since the timing of discharge to the community was not known. Readmission hospitalizations were eligible to be included as index hospitalizations if they met sample inclusion criteria. The final sample for readmission analyses included 95,354 SI hospitalizations and 38,162 SA hospitalizations (Figure).

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was any unplanned, all-cause readmission within 30 days of index hospitalization for SI or SA. Among 30-day readmissions, we examined readmission timing, whether the readmission was to the same hospital or a different hospital, length of stay, and indication for readmission (medical/surgical or psychiatric, and presence of SI or SA diagnoses). Planned readmissions were identified using measure specifications endorsed by the AHRQ and the National Quality Forum16 and excluded from measurement.

Among index hospitalizations for SI, we specifically examined 30-day readmissions for subsequent SA, since one objective of hospitalization for SI is to prevent progression to SA or death. We could not identify hospitalizations for repeat SA after index hospitalization for SA, because diagnosis codes did not differentiate between readmission for complications of index SA and readmission for repeat SA.

Independent Variables

We analyzed demographic, clinical, and hospital factors associated with readmissions in other samples.17–20 Demographic characteristics included patient gender and age, urban or rural residence, payer, and median national income quartile for a patient’s ZIP code. Race and ethnicity data are not available in the NRD.

Clinical characteristics included hospitalization in the 30-days preceding the index hospitalization, index hospitalization length of stay, and admission via the emergency department (ED) versus direct admission. A patient’s chronic condition profile was determined using index hospitalization diagnosis codes. Complex chronic conditions (eg, cancer, cystic fibrosis) were identified using a classification system used in several prior studies of hospital administrative datasets,21 and other noncomplex chronic medical conditions (eg, asthma, obesity) were identified using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) chronic condition indicator system.22 Psychiatric conditions (eg, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, autism) were identified and categorized using a classification system used in studies of hospital administrative datasets.23 The number of psychiatric conditions was determined by counting the number of psychiatric condition categories in which a patient had a diagnosis. SA was categorized as having lower risk of death (eg, medication overdose, injury from cutting or piercing) or higher risk of death (eg, hanging, suffocation, or firearm injury).24

Because of known temporal trends in SI and SA,25,26 the month and year of admission were included as covariates. Hospital characteristics included teaching hospital and children’s hospital designations.

Statistical Analysis

We compared descriptive, summary statistics for characteristics of index hospitalizations with and without a 30-day readmission using Rao-Scott chi-square tests. In multivariable analyses, we derived logistic regression models to measure the associations of patient, hospital, and temporal factors with 30-day hospital readmissions. Analyses were conducted in SAS PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC and were weighted to achieve national estimates, clustered by sample stratum and hospital to account for the complex survey design,27 clustered by patients to account for multiple index visits per patient, and adjusted for clinical, demographic, and hospital characteristics. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses. All tests were two-sided, and a P value <.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

In the weighted analyses, we identified 133,516 hospitalizations in acute-care hospitals for SI or SA, and 8.5% (n = 11,375) of hospitalizations had at least one unplanned 30-day readmission to an acute-care hospital. Unweighted, the sample included 37,683 patients and 42,198 hospitalizations. Among all patients represented in the sample, 90.5% had only a single SI or SA hospitalization, 7.7% had two hospitalizations, and 1.8% had >2 hospitalizations in one year.

Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics and displays the demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics of index hospitalizations by the 30-day readmission status. Patients represented in the index hospitalizations were 64.9% female, 3.6% were aged 6-9 years, 40.1% were aged 10-14 years, and 56.3% were aged 15-17 years. Nearly half of the patients (49.1%) used public insurance. Nearly half (44.9%) lived in metropolitan areas with >1 million residents, 36.1% lived in metropolitan areas with 50,000 to 1 million residents, and 14.7% lived in rural areas.

Median length of stay for the index hospitalization was 5 days (interquartile range [IQR] 3-7). Nearly one-third (32.3%) of patients had a noncomplex chronic medical condition, 7.8% had a complex chronic medical condition, and 98.1% had a psychiatric condition. The most common psychiatric conditions were depressive disorders (60.0%) and anxiety disorders (42.2%). More than half (55.0%) of the patients had >2 psychiatric conditions. Most hospitalizations in the sample had SI only (71.4%). Among patients with SA, 81.0% had a lower lethality mechanism of injury and 19.0% had a higher lethality mechanism.

Patients experiencing a readmission were more likely to be 10-14 years old and use public insurance than patients without a readmission (P < .001 for both). For clinical characteristics, patients with a readmission were more likely to have longer index hospital stays (6 vs. 5 days), >2 psychiatric conditions (SI vs. SA), a prior admission in the 30 days preceding the index hospitalization, and admission via the ED (vs. direct admission) (P < .001 for all).

Association of Patient and Hospital Characteristics with Readmissions

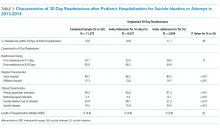

Table 2 displays the patient and hospital characteristics associated with readmissions. Among demographic characteristics, 10- to 14-year-old patients had higher odds of readmission (odds ratio [OR]: 1.18, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.07-1.29) than 15- to 17-year-old patients. Having public insurance was associated with higher odds of readmission (OR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.04-1.25). We found no differences in readmission rates based on sex, urban or rural location, or patient’s ZIP code income quartile.

Among clinical characteristics, hospitalizations with an admission for SI or SA in the preceding 30 days, meaning that the index hospitalization itself was a readmission, had the strongest association with readmissions (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 2.73-3.61). In addition, patients admitted via the ED for the index hospitalization had higher odds of readmission (OR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.15-1.36). Chronic psychiatric conditions associated with higher odds of readmission included psychotic disorders (OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.16-1.67) and bipolar disorder (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.13-1.44).

Characteristics of 30-day Readmissions

Table 3 displays the characteristics of readmissions after SI compared to that after SA. Among the combined sample of 11,375 30-day readmissions, 34.1% occurred within 7 days, and 65.9% in 8-30 days. Eleven percent of patients with any readmission had more than one readmission within 30 days. Among readmissions, 94.5% were for a psychiatric problem and 5.5% were for a medical or surgical problem. A total of 43.9% had a diagnosis of SI and 19.5% a diagnosis of SA. Readmissions were more likely to occur at a different hospital after SI than after SA (48.1% vs. 31.3%, P < .001). Medical and surgical indications for readmission were less common after SI than after SA (4.4% vs. 8.7%, P < .001). Only 1.2% of SI hospitalizations had a readmission for SA within 30 days. Of these cases, 55.6% were aged 15-17 years, 43.3% were aged 10-14 years, and 1.1% were aged 6-9 years; 73.1% of the patients were female, and 49.1% used public insurance.

DISCUSSION

SI and SA in children and adolescents are substantial public health problems associated with significant hospital resource utilization. In 2013 and 2014, there were 181,575 pediatric acute-care hospitalizations for SI or SA, accounting for 9.5% of all hospitalizations in 6- to 17-year-old patients nationally. Among acute-care SI and SA hospitalizations, 8.5% had a readmission to an acute-care hospital within 30 days. The study data source did not include psychiatric specialty hospitals, and the number of index hospitalizations is likely substantially higher when psychiatric specialty hospitalizations are included. Readmissions may also be higher if patients were readmitted to psychiatric specialty hospitals after discharge from acute-care hospitals. The strongest risk factor for unplanned 30-day readmissions was a previous hospitalization in the 30 days before the index admission, likely a marker for severity or complexity of psychiatric illness. Other characteristics associated with higher odds of readmission were bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, and age 10-14 years. More than one-third of readmissions occurred within the first 7 days after hospital discharge. The prevalence of SI and SA hospitalizations and readmissions was similar to findings in previous analyses of mental health hospitalizations.10,28

A patient’s psychiatric illness type and severity, as evidenced by the need for frequent repeat hospitalizations, was highly associated with the risk of 30-day readmission. Any hospitalization in the 30 days preceding the index hospitalization, whether for SI/SA or for another problem, was a strong risk factor for readmissions. We suspect that prior SI/SA hospitalizations reflect a patient’s chronic elevated risk for suicide. Prior hospitalizations not for SI or SA could be hospitalizations for mental illness exacerbations that increase the risk of SI or SA, eg, bipolar disorder with acute mania, or they could represent physical health problems. Chronic physical health problems are a known risk factor for SI and SA.29

A knowledge of those characteristics that increase the readmission risk can inform future resource allocation, research, and policy in several ways. First, longer hospital stays could mitigate readmission risk in some patients with severe psychiatric illness. European studies in older adolescents and adults show that for severe psychiatric illness, a longer hospital stay is associated with a lower risk of hospital readmission.15,30 Second, better access to intensive community-based mental health (MH) services, including evidence-based psychotherapy and medication management, improves symptoms in young people.31 Access to these services likely affects the risk of hospital readmission. We found that readmission risk was highest in 10- to 14-year-olds. Taken in the context of existing evidence that suicide rates are rising in younger patients,1,3 our findings suggest that particular attention to community services for younger patients is needed. Third, care coordination could help patients access beneficial services to reduce readmissions and improve other outcomes. Enhanced discharge care coordination reduced suicide deaths in high-risk populations in Europe32 and Japan33 and improved attendance at mental health follow-up after pediatric ED discharge in a small United States sample.34 Given that one-third of readmissions occurred within seven days, care coordination designed to ensure access to ambulatory services in the immediate postdischarge period may be particularly beneficial.

We found that ZIP code income quartile was not associated with readmissions. We suspect that poverty is not as closely correlated with MH hospitalization outcomes as it is with physical health hospitalization outcomes for several reasons. Medicaid insurance historically has more robust coverage of mental health services than some private insurance plans, which might offset some of the risk of poor mental health outcomes associated with poverty. Low-income families are eligible to use social services, and families accessing social services might have more opportunities to become familiar with community mental health programs. Further, the expectation of high achievement found in some higher income families is associated with MH problems in children and adolescents.35 Therefore, being in a higher income quartile might not be as protective against poor mental health outcomes as it is against poor physical health outcomes.

Although the NRD provides a rich source of readmission data across hospitals nationally, several limitations are inherent to this administrative dataset. First, data from specialty psychiatric hospitals were not included in the NRD. The study underestimates the total number of index hospitalizations and readmissions, since index SI/SA hospitalizations at psychiatric hospitals are not included, and readmissions are not included if they occurred at specialty psychiatric hospitals. Second, because data cannot be linked between calendar years, we excluded January and December hospitalizations, and findings might not generalize to hospitalizations in January and December. Seasonal trends in SI/SA hospitalizations are known to occur.36 Third, race, ethnicity, primary language, gender identity, and sexual orientation are not available in the NRD, and we could not examine the association of these characteristics with the likelihood of readmissions. Fourth, we did not have information about pre- or posthospitalization insurance enrollment or outpatient services that could affect the risk of readmission. Nevertheless, this study offers information on the characteristics of readmissions after hospitalizations for SI and SA in a large nationally representative sample of youth, and the findings can inform resource planning to prevent suicides.

CONCLUSION

Hospital readmissions are common in patients with SI and SA, and patients with a recent previous hospitalization have the highest risk of readmission. More than one-third of readmissions after SI or SA occurred within the first seven days. Due to the dearth of mental health services in the community, hospitals offer an important safety net for youth experiencing acute suicidal crises. Strategies to improve the continuum of care for patients at risk of suicide that solely focus on reducing readmissions are not likely to benefit patients. However, readmissions can identify opportunities for improving hospital discharge processes and outpatient services. Future research and clinical innovation to investigate and improve hospital discharge planning and access to community mental health services is likely to benefit patients and could reduce 30-day hospital readmissions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Lawlor for his assistance with the analysis.

Disclosures

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Zima received funding from the Behavioral Health Centers of Excellence for California (SB852).

1. Sheftall AH, Asti L, Horowitz LM, et al. Suicide in elementary school-aged children and early adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20160436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0436. PubMed

2. Prevention CNC for I. Suicide facts at a Glance 2015 nonfatal suicidal thoughts and behavior. In: 2015:3-4. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/34181/cdc_34181_DS1.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2016.

3. Curtin S, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. Hyattsville, MD; 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db241.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2016. PubMed

4. Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. PubMed

5. Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, Mckean AJ. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(11):1094-1100. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854. PubMed

6. Torio CM, Encinosa W, Berdahl T, McCormick MC, Simpson LA. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the united states: national estimates of cost, utilization and expenditures for children with mental health conditions. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):19-35. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.07.007. PubMed

7. Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173517. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3517. PubMed

8. Gay JC, Zima BT, Coker TR, et al. Postacute care after pediatric hospitalizations for a primary mental health condition. J Pediatr. 2018;193:222-228.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.058. PubMed

9. Heslin KC, Weiss AJ. Hospital Readmissions Involving Psychiatric Disorders, 2012. 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305353/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK305353.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2017. PubMed

10. Feng JY, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, Nakamura MM, Schuster MA. Readmission after pediatric mental health admissions. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20171571. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1571. PubMed

11. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3527. PubMed

12. Callahan ST, Fuchs DC, Shelton RC, et al. Identifying suicidal behavior among adolescents using administrative claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(7):769-775. doi: 10.1002/pds.3421. PubMed

13. SAMHSA, HHS, Synectics for Management Decisions, Mathematica Policy Research. National Mental Health Services Survey: 2010: Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities. http://media.samhsa.gov/data/DASIS/NMHSS2010D/NMHSS2010_Web.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2015.

14. Patrick AR, Miller M, Barber CW, Wang PS, Canning CF, Schneeweiss S. Identification of hospitalizations for intentional self-harm when E-codes are incompletely recorded. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(12):1263-1275. doi: 10.1002/pds.2037. PubMed

15. Mellesdal L, Mehlum L, Wentzel-Larsen T, Kroken R, Jørgensen HA. Suicide risk and acute psychiatric readmissions: a prospective cohort study. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(1):25-31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.25. PubMed

16. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. Measure: Pediatric All-Condition Readmission Measure Measure Developer: Center of Excellence for Pediatric Quality Measurement (CEPQM). https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/policymakers/chipra/factsheets/chipra_14-p008-1-ef.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2017.

17. Cancino RS, Culpepper L, Sadikova E, Martin J, Jack BW, Mitchell SE. Dose-response relationship between depressive symptoms and hospital readmission. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(6):358-364. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2180. PubMed

18. Carlisle CE, Mamdani M, Schachar R, To T. Aftercare, emergency department visits, and readmission in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(3):283-293. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0890856711011002. Accessed November 2, 2015. PubMed

19. Fadum EA, Stanley B, Qin P, Diep LM, Mehlum L. Self-poisoning with medications in adolescents: a national register study of hospital admissions and readmissions. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(6):709-715. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.09.004. PubMed

20. Bernet AC. Predictors of psychiatric readmission among veterans at high risk of suicide: the impact of post-discharge aftercare. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;27(5):260-261. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.07.001. PubMed

21. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-199. PubMed

22. HCUP. HCUP-US Tools & Software Page. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Published 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

23. Zima BT, Rodean J, Hall M, Bardach NS, Coker TR, Berry JG. Psychiatric disorders and trends in resource use in pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20160909-e20160909. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0909. PubMed

24. Spicer RS, Miller TR. Suicide acts in 8 states: incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and method. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1885-1891. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.12.1885. PubMed

25. Hansen B, Lang M. Back to school blues: Seasonality of youth suicide and the academic calendar. Econ Educ Rev. 2011;30(5):850-861. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.04.012.

26. Lueck C, Kearl L, Lam CN, Claudius I. Do emergency pediatric psychiatric visits for danger to self or others correspond to times of school attendance? Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(5):682-684. doi: 10.1016/J.AJEM.2015.02.055. PubMed

27. Healthcare Cost And Utilization Project. Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Readmissions Database. Rockville, MD; 2017. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nrd/Introduction_NRD_2010-2014.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2017.

28. Bardach NS, Coker TR, Zima BT, et al. Common and costly hospitalizations for pediatric mental health disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):602-609. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3165. PubMed

29. Ahmedani BK, Peterson EL, Hu Y, et al. Major physical health conditions and risk of suicide. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3):308-315. doi: 10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2017.04.001. PubMed

30. Gunnell D, Hawton K, Ho D, et al. Hospital admissions for self harm after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care: cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2278. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2278. PubMed

31. The TADS Team. The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1132. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1132. PubMed

32. While D, Bickley H, Roscoe A, et al. Implementation of mental health service recommendations in England and Wales and suicide rates, 1997-2006: A cross-sectional and before-and-after observational study. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1005-1012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61712-1. PubMed

33. Kawanishi C, Aruga T, Ishizuka N, et al. Assertive case management versus enhanced usual care for people with mental health problems who had attempted suicide and were admitted to hospital emergency departments in Japan (ACTION-J): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(3):193-201. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70259-7. PubMed

34. Grupp-Phelan J, McGuire L, Husky MM, Olfson M. A randomized controlled trial to engage in care of adolescent emergency department patients with mental health problems that increase suicide risk. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(12):1263-1268. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182767ac8. PubMed

35. Ciciolla L, Curlee AS, Karageorge J, Luthar SS. When mothers and fathers are seen as disproportionately valuing achievements: implications for adjustment among upper middle class youth. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(5):1057-1075. doi: 10.1007/s10964-016-0596-x. PubMed

36. Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008–2015. Pediatrics. May 2018:e20172426. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2426. PubMed

Suicide is a leading cause of death among 10- to 34-year-olds in the United States.1,2 During the past two decades, the youth suicide death rate has risen by 24%, and more than 5,000 young people die from suicide each year.3 Suicide ideation (SI) and suicide attempts (SAs) are well-established risk factors for suicide death and a source of morbidity for patients and families. One-third of youth with SI attempt suicide at some point in their lifetime.4 Approximately 11% of youth SAs result in suicide death, and 2% of youth who attempt suicide subsequently go on to die from suicide after recovering from a prior SA.5 More than 60,000 youth are hospitalized for SI or SA each year,6 and young people hospitalized for SA are at high short-term risk of repeat SA and suicide death.7 Hospitals need strategies for measuring the quality of SI and SA hospitalizations, monitoring postdischarge outcomes, and identifying the patients at the highest risk of poor outcomes. Readmissions are a useful hospital quality measure that can indicate re-emergence of SI, repeat SA, or inadequate community-based mental health treatment, and interventions designed for patients with readmissions can potentially avert morbidity or mortality.

The National Committee on Quality Assurance recommends measurement of quality metrics for 30-day mental health follow-up after psychiatric hospitalizations, 30-day readmissions after adult (but not pediatric) psychiatric hospitalizations, and 30-day readmissions in pediatric medical and surgical hospitalizations. Readmission measures are not consistently used to evaluate pediatric psychiatric hospitalizations, and psychiatric quality measures are not used to evaluate medical or surgical hospitalizations for SA. Recent research has investigated transfers to postacute care,8 readmission prevalence, variation in hospital readmission performance, and risk factors for readmissions after pediatric psychiatric hospitalizations.9–11 However, no national study has investigated 30-day readmissions in youth hospitalized specifically for SI or SA.

To inform hospital quality measurement and improve hospital and postdischarge care for youth at risk of suicide, more information is needed about the characteristics of and the risk factors for readmissions after index SI/SA hospitalization. To address this knowledge gap, among SI/SA hospitalizations in 6- to 17-year-olds, we examined (1) unplanned 30-day readmissions and characteristics of hospitalizations by 30-day readmission status; (2) patient, hospital, and regional characteristics associated with 30-day readmissions; and (3) characteristics of 30-day readmissions.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a national, retrospective cohort study of hospitalizations for patients aged 6-17 years using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) 2013 and 2014 Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). The combined 2013-2014 NRD includes administrative data from a nationally representative sample of 29 million hospitalizations in 22 states, accounting for 49.3% of all US hospitalizations, and is weighted for national projections. The NRD includes hospital information, patient demographic information, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis, procedure, and external cause of injury codes (E-codes). The database includes one primary diagnosis, up to 24 additional diagnoses, and up to 4 E-codes for each hospitalization. The NRD includes information about hospitalizations in acute-care general hospitals (including their psychiatric units) but not from specialty psychiatric hospitals. The database also includes de-identified, verified patient linkage numbers so that patients can be tracked across multiple hospitalizations at the same institution or different institutions within the same state. This study was considered to be exempt from review by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board.

Sample

We identified a sample of 181,575 hospitalizations for SI (n = 119,037) or SA (n = 62,538) among 6- to 17-year-olds between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2014 (Figure). We included children as young as 6 years because validated methods exist to identify SI and SA in this age group,12 and because suicide deaths have recently increased among younger children.3 We excluded patients aged 18 years and older from this study since delivery of mental health services differs for adults.13 To create the sample, we first identified all hospitalizations of patients aged 6-17 years. We then used a validated algorithm relying on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for poisonings and E-codes for self-injury (E950-959) to identify hospitalizations related to SA.12 Because E-code completeness varies among states,14 we also used the combination of having both a diagnosis code for injury (800-999) and an ICD-9-CM code for SI (V62.84) as a proxy for SA. Among hospitalizations without SA, we identified hospitalizations with SI using the ICD-9-CM code for SI (V62.84) in any position.

We identified 133,516 index hospitalizations with complete data at risk for an unplanned readmission. Because NRD data cannot be linked between calendar years, we limited the study time period for each calendar year to 10 months. We excluded hospitalizations in January because the full 30-day time frame to determine whether a hospitalization had occurred in the preceding 30 days, a known risk factor for readmissions in other samples,15 was not available. We excluded index hospitalizations occurring in December, because the full 30-day time frame to ascertain readmissions was not available. We excluded hospitalizations resulting in death, since these are not at risk for readmission, and hospitalizations resulting in transfer, since the timing of discharge to the community was not known. Readmission hospitalizations were eligible to be included as index hospitalizations if they met sample inclusion criteria. The final sample for readmission analyses included 95,354 SI hospitalizations and 38,162 SA hospitalizations (Figure).

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was any unplanned, all-cause readmission within 30 days of index hospitalization for SI or SA. Among 30-day readmissions, we examined readmission timing, whether the readmission was to the same hospital or a different hospital, length of stay, and indication for readmission (medical/surgical or psychiatric, and presence of SI or SA diagnoses). Planned readmissions were identified using measure specifications endorsed by the AHRQ and the National Quality Forum16 and excluded from measurement.

Among index hospitalizations for SI, we specifically examined 30-day readmissions for subsequent SA, since one objective of hospitalization for SI is to prevent progression to SA or death. We could not identify hospitalizations for repeat SA after index hospitalization for SA, because diagnosis codes did not differentiate between readmission for complications of index SA and readmission for repeat SA.

Independent Variables

We analyzed demographic, clinical, and hospital factors associated with readmissions in other samples.17–20 Demographic characteristics included patient gender and age, urban or rural residence, payer, and median national income quartile for a patient’s ZIP code. Race and ethnicity data are not available in the NRD.

Clinical characteristics included hospitalization in the 30-days preceding the index hospitalization, index hospitalization length of stay, and admission via the emergency department (ED) versus direct admission. A patient’s chronic condition profile was determined using index hospitalization diagnosis codes. Complex chronic conditions (eg, cancer, cystic fibrosis) were identified using a classification system used in several prior studies of hospital administrative datasets,21 and other noncomplex chronic medical conditions (eg, asthma, obesity) were identified using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) chronic condition indicator system.22 Psychiatric conditions (eg, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, autism) were identified and categorized using a classification system used in studies of hospital administrative datasets.23 The number of psychiatric conditions was determined by counting the number of psychiatric condition categories in which a patient had a diagnosis. SA was categorized as having lower risk of death (eg, medication overdose, injury from cutting or piercing) or higher risk of death (eg, hanging, suffocation, or firearm injury).24

Because of known temporal trends in SI and SA,25,26 the month and year of admission were included as covariates. Hospital characteristics included teaching hospital and children’s hospital designations.

Statistical Analysis

We compared descriptive, summary statistics for characteristics of index hospitalizations with and without a 30-day readmission using Rao-Scott chi-square tests. In multivariable analyses, we derived logistic regression models to measure the associations of patient, hospital, and temporal factors with 30-day hospital readmissions. Analyses were conducted in SAS PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC and were weighted to achieve national estimates, clustered by sample stratum and hospital to account for the complex survey design,27 clustered by patients to account for multiple index visits per patient, and adjusted for clinical, demographic, and hospital characteristics. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses. All tests were two-sided, and a P value <.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

In the weighted analyses, we identified 133,516 hospitalizations in acute-care hospitals for SI or SA, and 8.5% (n = 11,375) of hospitalizations had at least one unplanned 30-day readmission to an acute-care hospital. Unweighted, the sample included 37,683 patients and 42,198 hospitalizations. Among all patients represented in the sample, 90.5% had only a single SI or SA hospitalization, 7.7% had two hospitalizations, and 1.8% had >2 hospitalizations in one year.

Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics and displays the demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics of index hospitalizations by the 30-day readmission status. Patients represented in the index hospitalizations were 64.9% female, 3.6% were aged 6-9 years, 40.1% were aged 10-14 years, and 56.3% were aged 15-17 years. Nearly half of the patients (49.1%) used public insurance. Nearly half (44.9%) lived in metropolitan areas with >1 million residents, 36.1% lived in metropolitan areas with 50,000 to 1 million residents, and 14.7% lived in rural areas.

Median length of stay for the index hospitalization was 5 days (interquartile range [IQR] 3-7). Nearly one-third (32.3%) of patients had a noncomplex chronic medical condition, 7.8% had a complex chronic medical condition, and 98.1% had a psychiatric condition. The most common psychiatric conditions were depressive disorders (60.0%) and anxiety disorders (42.2%). More than half (55.0%) of the patients had >2 psychiatric conditions. Most hospitalizations in the sample had SI only (71.4%). Among patients with SA, 81.0% had a lower lethality mechanism of injury and 19.0% had a higher lethality mechanism.

Patients experiencing a readmission were more likely to be 10-14 years old and use public insurance than patients without a readmission (P < .001 for both). For clinical characteristics, patients with a readmission were more likely to have longer index hospital stays (6 vs. 5 days), >2 psychiatric conditions (SI vs. SA), a prior admission in the 30 days preceding the index hospitalization, and admission via the ED (vs. direct admission) (P < .001 for all).

Association of Patient and Hospital Characteristics with Readmissions

Table 2 displays the patient and hospital characteristics associated with readmissions. Among demographic characteristics, 10- to 14-year-old patients had higher odds of readmission (odds ratio [OR]: 1.18, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.07-1.29) than 15- to 17-year-old patients. Having public insurance was associated with higher odds of readmission (OR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.04-1.25). We found no differences in readmission rates based on sex, urban or rural location, or patient’s ZIP code income quartile.

Among clinical characteristics, hospitalizations with an admission for SI or SA in the preceding 30 days, meaning that the index hospitalization itself was a readmission, had the strongest association with readmissions (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 2.73-3.61). In addition, patients admitted via the ED for the index hospitalization had higher odds of readmission (OR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.15-1.36). Chronic psychiatric conditions associated with higher odds of readmission included psychotic disorders (OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.16-1.67) and bipolar disorder (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.13-1.44).

Characteristics of 30-day Readmissions

Table 3 displays the characteristics of readmissions after SI compared to that after SA. Among the combined sample of 11,375 30-day readmissions, 34.1% occurred within 7 days, and 65.9% in 8-30 days. Eleven percent of patients with any readmission had more than one readmission within 30 days. Among readmissions, 94.5% were for a psychiatric problem and 5.5% were for a medical or surgical problem. A total of 43.9% had a diagnosis of SI and 19.5% a diagnosis of SA. Readmissions were more likely to occur at a different hospital after SI than after SA (48.1% vs. 31.3%, P < .001). Medical and surgical indications for readmission were less common after SI than after SA (4.4% vs. 8.7%, P < .001). Only 1.2% of SI hospitalizations had a readmission for SA within 30 days. Of these cases, 55.6% were aged 15-17 years, 43.3% were aged 10-14 years, and 1.1% were aged 6-9 years; 73.1% of the patients were female, and 49.1% used public insurance.

DISCUSSION

SI and SA in children and adolescents are substantial public health problems associated with significant hospital resource utilization. In 2013 and 2014, there were 181,575 pediatric acute-care hospitalizations for SI or SA, accounting for 9.5% of all hospitalizations in 6- to 17-year-old patients nationally. Among acute-care SI and SA hospitalizations, 8.5% had a readmission to an acute-care hospital within 30 days. The study data source did not include psychiatric specialty hospitals, and the number of index hospitalizations is likely substantially higher when psychiatric specialty hospitalizations are included. Readmissions may also be higher if patients were readmitted to psychiatric specialty hospitals after discharge from acute-care hospitals. The strongest risk factor for unplanned 30-day readmissions was a previous hospitalization in the 30 days before the index admission, likely a marker for severity or complexity of psychiatric illness. Other characteristics associated with higher odds of readmission were bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, and age 10-14 years. More than one-third of readmissions occurred within the first 7 days after hospital discharge. The prevalence of SI and SA hospitalizations and readmissions was similar to findings in previous analyses of mental health hospitalizations.10,28

A patient’s psychiatric illness type and severity, as evidenced by the need for frequent repeat hospitalizations, was highly associated with the risk of 30-day readmission. Any hospitalization in the 30 days preceding the index hospitalization, whether for SI/SA or for another problem, was a strong risk factor for readmissions. We suspect that prior SI/SA hospitalizations reflect a patient’s chronic elevated risk for suicide. Prior hospitalizations not for SI or SA could be hospitalizations for mental illness exacerbations that increase the risk of SI or SA, eg, bipolar disorder with acute mania, or they could represent physical health problems. Chronic physical health problems are a known risk factor for SI and SA.29

A knowledge of those characteristics that increase the readmission risk can inform future resource allocation, research, and policy in several ways. First, longer hospital stays could mitigate readmission risk in some patients with severe psychiatric illness. European studies in older adolescents and adults show that for severe psychiatric illness, a longer hospital stay is associated with a lower risk of hospital readmission.15,30 Second, better access to intensive community-based mental health (MH) services, including evidence-based psychotherapy and medication management, improves symptoms in young people.31 Access to these services likely affects the risk of hospital readmission. We found that readmission risk was highest in 10- to 14-year-olds. Taken in the context of existing evidence that suicide rates are rising in younger patients,1,3 our findings suggest that particular attention to community services for younger patients is needed. Third, care coordination could help patients access beneficial services to reduce readmissions and improve other outcomes. Enhanced discharge care coordination reduced suicide deaths in high-risk populations in Europe32 and Japan33 and improved attendance at mental health follow-up after pediatric ED discharge in a small United States sample.34 Given that one-third of readmissions occurred within seven days, care coordination designed to ensure access to ambulatory services in the immediate postdischarge period may be particularly beneficial.

We found that ZIP code income quartile was not associated with readmissions. We suspect that poverty is not as closely correlated with MH hospitalization outcomes as it is with physical health hospitalization outcomes for several reasons. Medicaid insurance historically has more robust coverage of mental health services than some private insurance plans, which might offset some of the risk of poor mental health outcomes associated with poverty. Low-income families are eligible to use social services, and families accessing social services might have more opportunities to become familiar with community mental health programs. Further, the expectation of high achievement found in some higher income families is associated with MH problems in children and adolescents.35 Therefore, being in a higher income quartile might not be as protective against poor mental health outcomes as it is against poor physical health outcomes.

Although the NRD provides a rich source of readmission data across hospitals nationally, several limitations are inherent to this administrative dataset. First, data from specialty psychiatric hospitals were not included in the NRD. The study underestimates the total number of index hospitalizations and readmissions, since index SI/SA hospitalizations at psychiatric hospitals are not included, and readmissions are not included if they occurred at specialty psychiatric hospitals. Second, because data cannot be linked between calendar years, we excluded January and December hospitalizations, and findings might not generalize to hospitalizations in January and December. Seasonal trends in SI/SA hospitalizations are known to occur.36 Third, race, ethnicity, primary language, gender identity, and sexual orientation are not available in the NRD, and we could not examine the association of these characteristics with the likelihood of readmissions. Fourth, we did not have information about pre- or posthospitalization insurance enrollment or outpatient services that could affect the risk of readmission. Nevertheless, this study offers information on the characteristics of readmissions after hospitalizations for SI and SA in a large nationally representative sample of youth, and the findings can inform resource planning to prevent suicides.

CONCLUSION

Hospital readmissions are common in patients with SI and SA, and patients with a recent previous hospitalization have the highest risk of readmission. More than one-third of readmissions after SI or SA occurred within the first seven days. Due to the dearth of mental health services in the community, hospitals offer an important safety net for youth experiencing acute suicidal crises. Strategies to improve the continuum of care for patients at risk of suicide that solely focus on reducing readmissions are not likely to benefit patients. However, readmissions can identify opportunities for improving hospital discharge processes and outpatient services. Future research and clinical innovation to investigate and improve hospital discharge planning and access to community mental health services is likely to benefit patients and could reduce 30-day hospital readmissions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Lawlor for his assistance with the analysis.

Disclosures

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Zima received funding from the Behavioral Health Centers of Excellence for California (SB852).

Suicide is a leading cause of death among 10- to 34-year-olds in the United States.1,2 During the past two decades, the youth suicide death rate has risen by 24%, and more than 5,000 young people die from suicide each year.3 Suicide ideation (SI) and suicide attempts (SAs) are well-established risk factors for suicide death and a source of morbidity for patients and families. One-third of youth with SI attempt suicide at some point in their lifetime.4 Approximately 11% of youth SAs result in suicide death, and 2% of youth who attempt suicide subsequently go on to die from suicide after recovering from a prior SA.5 More than 60,000 youth are hospitalized for SI or SA each year,6 and young people hospitalized for SA are at high short-term risk of repeat SA and suicide death.7 Hospitals need strategies for measuring the quality of SI and SA hospitalizations, monitoring postdischarge outcomes, and identifying the patients at the highest risk of poor outcomes. Readmissions are a useful hospital quality measure that can indicate re-emergence of SI, repeat SA, or inadequate community-based mental health treatment, and interventions designed for patients with readmissions can potentially avert morbidity or mortality.

The National Committee on Quality Assurance recommends measurement of quality metrics for 30-day mental health follow-up after psychiatric hospitalizations, 30-day readmissions after adult (but not pediatric) psychiatric hospitalizations, and 30-day readmissions in pediatric medical and surgical hospitalizations. Readmission measures are not consistently used to evaluate pediatric psychiatric hospitalizations, and psychiatric quality measures are not used to evaluate medical or surgical hospitalizations for SA. Recent research has investigated transfers to postacute care,8 readmission prevalence, variation in hospital readmission performance, and risk factors for readmissions after pediatric psychiatric hospitalizations.9–11 However, no national study has investigated 30-day readmissions in youth hospitalized specifically for SI or SA.

To inform hospital quality measurement and improve hospital and postdischarge care for youth at risk of suicide, more information is needed about the characteristics of and the risk factors for readmissions after index SI/SA hospitalization. To address this knowledge gap, among SI/SA hospitalizations in 6- to 17-year-olds, we examined (1) unplanned 30-day readmissions and characteristics of hospitalizations by 30-day readmission status; (2) patient, hospital, and regional characteristics associated with 30-day readmissions; and (3) characteristics of 30-day readmissions.

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a national, retrospective cohort study of hospitalizations for patients aged 6-17 years using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) 2013 and 2014 Nationwide Readmissions Database (NRD). The combined 2013-2014 NRD includes administrative data from a nationally representative sample of 29 million hospitalizations in 22 states, accounting for 49.3% of all US hospitalizations, and is weighted for national projections. The NRD includes hospital information, patient demographic information, and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis, procedure, and external cause of injury codes (E-codes). The database includes one primary diagnosis, up to 24 additional diagnoses, and up to 4 E-codes for each hospitalization. The NRD includes information about hospitalizations in acute-care general hospitals (including their psychiatric units) but not from specialty psychiatric hospitals. The database also includes de-identified, verified patient linkage numbers so that patients can be tracked across multiple hospitalizations at the same institution or different institutions within the same state. This study was considered to be exempt from review by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Institutional Review Board.

Sample

We identified a sample of 181,575 hospitalizations for SI (n = 119,037) or SA (n = 62,538) among 6- to 17-year-olds between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2014 (Figure). We included children as young as 6 years because validated methods exist to identify SI and SA in this age group,12 and because suicide deaths have recently increased among younger children.3 We excluded patients aged 18 years and older from this study since delivery of mental health services differs for adults.13 To create the sample, we first identified all hospitalizations of patients aged 6-17 years. We then used a validated algorithm relying on ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes for poisonings and E-codes for self-injury (E950-959) to identify hospitalizations related to SA.12 Because E-code completeness varies among states,14 we also used the combination of having both a diagnosis code for injury (800-999) and an ICD-9-CM code for SI (V62.84) as a proxy for SA. Among hospitalizations without SA, we identified hospitalizations with SI using the ICD-9-CM code for SI (V62.84) in any position.

We identified 133,516 index hospitalizations with complete data at risk for an unplanned readmission. Because NRD data cannot be linked between calendar years, we limited the study time period for each calendar year to 10 months. We excluded hospitalizations in January because the full 30-day time frame to determine whether a hospitalization had occurred in the preceding 30 days, a known risk factor for readmissions in other samples,15 was not available. We excluded index hospitalizations occurring in December, because the full 30-day time frame to ascertain readmissions was not available. We excluded hospitalizations resulting in death, since these are not at risk for readmission, and hospitalizations resulting in transfer, since the timing of discharge to the community was not known. Readmission hospitalizations were eligible to be included as index hospitalizations if they met sample inclusion criteria. The final sample for readmission analyses included 95,354 SI hospitalizations and 38,162 SA hospitalizations (Figure).

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was any unplanned, all-cause readmission within 30 days of index hospitalization for SI or SA. Among 30-day readmissions, we examined readmission timing, whether the readmission was to the same hospital or a different hospital, length of stay, and indication for readmission (medical/surgical or psychiatric, and presence of SI or SA diagnoses). Planned readmissions were identified using measure specifications endorsed by the AHRQ and the National Quality Forum16 and excluded from measurement.

Among index hospitalizations for SI, we specifically examined 30-day readmissions for subsequent SA, since one objective of hospitalization for SI is to prevent progression to SA or death. We could not identify hospitalizations for repeat SA after index hospitalization for SA, because diagnosis codes did not differentiate between readmission for complications of index SA and readmission for repeat SA.

Independent Variables

We analyzed demographic, clinical, and hospital factors associated with readmissions in other samples.17–20 Demographic characteristics included patient gender and age, urban or rural residence, payer, and median national income quartile for a patient’s ZIP code. Race and ethnicity data are not available in the NRD.

Clinical characteristics included hospitalization in the 30-days preceding the index hospitalization, index hospitalization length of stay, and admission via the emergency department (ED) versus direct admission. A patient’s chronic condition profile was determined using index hospitalization diagnosis codes. Complex chronic conditions (eg, cancer, cystic fibrosis) were identified using a classification system used in several prior studies of hospital administrative datasets,21 and other noncomplex chronic medical conditions (eg, asthma, obesity) were identified using the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) chronic condition indicator system.22 Psychiatric conditions (eg, anxiety disorders, substance abuse, autism) were identified and categorized using a classification system used in studies of hospital administrative datasets.23 The number of psychiatric conditions was determined by counting the number of psychiatric condition categories in which a patient had a diagnosis. SA was categorized as having lower risk of death (eg, medication overdose, injury from cutting or piercing) or higher risk of death (eg, hanging, suffocation, or firearm injury).24

Because of known temporal trends in SI and SA,25,26 the month and year of admission were included as covariates. Hospital characteristics included teaching hospital and children’s hospital designations.

Statistical Analysis

We compared descriptive, summary statistics for characteristics of index hospitalizations with and without a 30-day readmission using Rao-Scott chi-square tests. In multivariable analyses, we derived logistic regression models to measure the associations of patient, hospital, and temporal factors with 30-day hospital readmissions. Analyses were conducted in SAS PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC and were weighted to achieve national estimates, clustered by sample stratum and hospital to account for the complex survey design,27 clustered by patients to account for multiple index visits per patient, and adjusted for clinical, demographic, and hospital characteristics. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina) was used for all analyses. All tests were two-sided, and a P value <.05 was considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

In the weighted analyses, we identified 133,516 hospitalizations in acute-care hospitals for SI or SA, and 8.5% (n = 11,375) of hospitalizations had at least one unplanned 30-day readmission to an acute-care hospital. Unweighted, the sample included 37,683 patients and 42,198 hospitalizations. Among all patients represented in the sample, 90.5% had only a single SI or SA hospitalization, 7.7% had two hospitalizations, and 1.8% had >2 hospitalizations in one year.

Table 1 summarizes the sample characteristics and displays the demographic, clinical, and hospital characteristics of index hospitalizations by the 30-day readmission status. Patients represented in the index hospitalizations were 64.9% female, 3.6% were aged 6-9 years, 40.1% were aged 10-14 years, and 56.3% were aged 15-17 years. Nearly half of the patients (49.1%) used public insurance. Nearly half (44.9%) lived in metropolitan areas with >1 million residents, 36.1% lived in metropolitan areas with 50,000 to 1 million residents, and 14.7% lived in rural areas.

Median length of stay for the index hospitalization was 5 days (interquartile range [IQR] 3-7). Nearly one-third (32.3%) of patients had a noncomplex chronic medical condition, 7.8% had a complex chronic medical condition, and 98.1% had a psychiatric condition. The most common psychiatric conditions were depressive disorders (60.0%) and anxiety disorders (42.2%). More than half (55.0%) of the patients had >2 psychiatric conditions. Most hospitalizations in the sample had SI only (71.4%). Among patients with SA, 81.0% had a lower lethality mechanism of injury and 19.0% had a higher lethality mechanism.

Patients experiencing a readmission were more likely to be 10-14 years old and use public insurance than patients without a readmission (P < .001 for both). For clinical characteristics, patients with a readmission were more likely to have longer index hospital stays (6 vs. 5 days), >2 psychiatric conditions (SI vs. SA), a prior admission in the 30 days preceding the index hospitalization, and admission via the ED (vs. direct admission) (P < .001 for all).

Association of Patient and Hospital Characteristics with Readmissions

Table 2 displays the patient and hospital characteristics associated with readmissions. Among demographic characteristics, 10- to 14-year-old patients had higher odds of readmission (odds ratio [OR]: 1.18, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.07-1.29) than 15- to 17-year-old patients. Having public insurance was associated with higher odds of readmission (OR: 1.14, 95% CI: 1.04-1.25). We found no differences in readmission rates based on sex, urban or rural location, or patient’s ZIP code income quartile.

Among clinical characteristics, hospitalizations with an admission for SI or SA in the preceding 30 days, meaning that the index hospitalization itself was a readmission, had the strongest association with readmissions (OR: 3.14, 95% CI: 2.73-3.61). In addition, patients admitted via the ED for the index hospitalization had higher odds of readmission (OR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.15-1.36). Chronic psychiatric conditions associated with higher odds of readmission included psychotic disorders (OR: 1.39, 95% CI: 1.16-1.67) and bipolar disorder (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.13-1.44).

Characteristics of 30-day Readmissions

Table 3 displays the characteristics of readmissions after SI compared to that after SA. Among the combined sample of 11,375 30-day readmissions, 34.1% occurred within 7 days, and 65.9% in 8-30 days. Eleven percent of patients with any readmission had more than one readmission within 30 days. Among readmissions, 94.5% were for a psychiatric problem and 5.5% were for a medical or surgical problem. A total of 43.9% had a diagnosis of SI and 19.5% a diagnosis of SA. Readmissions were more likely to occur at a different hospital after SI than after SA (48.1% vs. 31.3%, P < .001). Medical and surgical indications for readmission were less common after SI than after SA (4.4% vs. 8.7%, P < .001). Only 1.2% of SI hospitalizations had a readmission for SA within 30 days. Of these cases, 55.6% were aged 15-17 years, 43.3% were aged 10-14 years, and 1.1% were aged 6-9 years; 73.1% of the patients were female, and 49.1% used public insurance.

DISCUSSION

SI and SA in children and adolescents are substantial public health problems associated with significant hospital resource utilization. In 2013 and 2014, there were 181,575 pediatric acute-care hospitalizations for SI or SA, accounting for 9.5% of all hospitalizations in 6- to 17-year-old patients nationally. Among acute-care SI and SA hospitalizations, 8.5% had a readmission to an acute-care hospital within 30 days. The study data source did not include psychiatric specialty hospitals, and the number of index hospitalizations is likely substantially higher when psychiatric specialty hospitalizations are included. Readmissions may also be higher if patients were readmitted to psychiatric specialty hospitals after discharge from acute-care hospitals. The strongest risk factor for unplanned 30-day readmissions was a previous hospitalization in the 30 days before the index admission, likely a marker for severity or complexity of psychiatric illness. Other characteristics associated with higher odds of readmission were bipolar disorder, psychotic disorders, and age 10-14 years. More than one-third of readmissions occurred within the first 7 days after hospital discharge. The prevalence of SI and SA hospitalizations and readmissions was similar to findings in previous analyses of mental health hospitalizations.10,28

A patient’s psychiatric illness type and severity, as evidenced by the need for frequent repeat hospitalizations, was highly associated with the risk of 30-day readmission. Any hospitalization in the 30 days preceding the index hospitalization, whether for SI/SA or for another problem, was a strong risk factor for readmissions. We suspect that prior SI/SA hospitalizations reflect a patient’s chronic elevated risk for suicide. Prior hospitalizations not for SI or SA could be hospitalizations for mental illness exacerbations that increase the risk of SI or SA, eg, bipolar disorder with acute mania, or they could represent physical health problems. Chronic physical health problems are a known risk factor for SI and SA.29

A knowledge of those characteristics that increase the readmission risk can inform future resource allocation, research, and policy in several ways. First, longer hospital stays could mitigate readmission risk in some patients with severe psychiatric illness. European studies in older adolescents and adults show that for severe psychiatric illness, a longer hospital stay is associated with a lower risk of hospital readmission.15,30 Second, better access to intensive community-based mental health (MH) services, including evidence-based psychotherapy and medication management, improves symptoms in young people.31 Access to these services likely affects the risk of hospital readmission. We found that readmission risk was highest in 10- to 14-year-olds. Taken in the context of existing evidence that suicide rates are rising in younger patients,1,3 our findings suggest that particular attention to community services for younger patients is needed. Third, care coordination could help patients access beneficial services to reduce readmissions and improve other outcomes. Enhanced discharge care coordination reduced suicide deaths in high-risk populations in Europe32 and Japan33 and improved attendance at mental health follow-up after pediatric ED discharge in a small United States sample.34 Given that one-third of readmissions occurred within seven days, care coordination designed to ensure access to ambulatory services in the immediate postdischarge period may be particularly beneficial.

We found that ZIP code income quartile was not associated with readmissions. We suspect that poverty is not as closely correlated with MH hospitalization outcomes as it is with physical health hospitalization outcomes for several reasons. Medicaid insurance historically has more robust coverage of mental health services than some private insurance plans, which might offset some of the risk of poor mental health outcomes associated with poverty. Low-income families are eligible to use social services, and families accessing social services might have more opportunities to become familiar with community mental health programs. Further, the expectation of high achievement found in some higher income families is associated with MH problems in children and adolescents.35 Therefore, being in a higher income quartile might not be as protective against poor mental health outcomes as it is against poor physical health outcomes.

Although the NRD provides a rich source of readmission data across hospitals nationally, several limitations are inherent to this administrative dataset. First, data from specialty psychiatric hospitals were not included in the NRD. The study underestimates the total number of index hospitalizations and readmissions, since index SI/SA hospitalizations at psychiatric hospitals are not included, and readmissions are not included if they occurred at specialty psychiatric hospitals. Second, because data cannot be linked between calendar years, we excluded January and December hospitalizations, and findings might not generalize to hospitalizations in January and December. Seasonal trends in SI/SA hospitalizations are known to occur.36 Third, race, ethnicity, primary language, gender identity, and sexual orientation are not available in the NRD, and we could not examine the association of these characteristics with the likelihood of readmissions. Fourth, we did not have information about pre- or posthospitalization insurance enrollment or outpatient services that could affect the risk of readmission. Nevertheless, this study offers information on the characteristics of readmissions after hospitalizations for SI and SA in a large nationally representative sample of youth, and the findings can inform resource planning to prevent suicides.

CONCLUSION

Hospital readmissions are common in patients with SI and SA, and patients with a recent previous hospitalization have the highest risk of readmission. More than one-third of readmissions after SI or SA occurred within the first seven days. Due to the dearth of mental health services in the community, hospitals offer an important safety net for youth experiencing acute suicidal crises. Strategies to improve the continuum of care for patients at risk of suicide that solely focus on reducing readmissions are not likely to benefit patients. However, readmissions can identify opportunities for improving hospital discharge processes and outpatient services. Future research and clinical innovation to investigate and improve hospital discharge planning and access to community mental health services is likely to benefit patients and could reduce 30-day hospital readmissions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank John Lawlor for his assistance with the analysis.

Disclosures

The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Zima received funding from the Behavioral Health Centers of Excellence for California (SB852).

1. Sheftall AH, Asti L, Horowitz LM, et al. Suicide in elementary school-aged children and early adolescents. Pediatrics. 2016;138(4):e20160436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0436. PubMed

2. Prevention CNC for I. Suicide facts at a Glance 2015 nonfatal suicidal thoughts and behavior. In: 2015:3-4. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/34181/cdc_34181_DS1.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2016.

3. Curtin S, Warner M, Hedegaard H. Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999-2014. Hyattsville, MD; 2016. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db241.pdf. Accessed November 7, 2016. PubMed

4. Nock MK, Green JG, Hwang I, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and treatment of lifetime suicidal behavior among adolescents: results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(3):300. doi: 10.1001/2013.jamapsychiatry.55. PubMed

5. Bostwick JM, Pabbati C, Geske JR, Mckean AJ. Suicide attempt as a risk factor for completed suicide: even more lethal than we knew. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173(11):1094-1100. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.15070854. PubMed

6. Torio CM, Encinosa W, Berdahl T, McCormick MC, Simpson LA. Annual report on health care for children and youth in the united states: national estimates of cost, utilization and expenditures for children with mental health conditions. Acad Pediatr. 2015;15(1):19-35. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2014.07.007. PubMed

7. Olfson M, Wall M, Wang S, et al. Suicide after deliberate self-harm in adolescents and young adults. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20173517. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3517. PubMed

8. Gay JC, Zima BT, Coker TR, et al. Postacute care after pediatric hospitalizations for a primary mental health condition. J Pediatr. 2018;193:222-228.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.09.058. PubMed

9. Heslin KC, Weiss AJ. Hospital Readmissions Involving Psychiatric Disorders, 2012. 2015. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK305353/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK305353.pdf. Accessed September 8, 2017. PubMed

10. Feng JY, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, Nakamura MM, Schuster MA. Readmission after pediatric mental health admissions. Pediatrics. 2017;140(6):e20171571. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-1571. PubMed

11. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3527. PubMed

12. Callahan ST, Fuchs DC, Shelton RC, et al. Identifying suicidal behavior among adolescents using administrative claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(7):769-775. doi: 10.1002/pds.3421. PubMed

13. SAMHSA, HHS, Synectics for Management Decisions, Mathematica Policy Research. National Mental Health Services Survey: 2010: Data on Mental Health Treatment Facilities. http://media.samhsa.gov/data/DASIS/NMHSS2010D/NMHSS2010_Web.pdf. Accessed November 13, 2015.

14. Patrick AR, Miller M, Barber CW, Wang PS, Canning CF, Schneeweiss S. Identification of hospitalizations for intentional self-harm when E-codes are incompletely recorded. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(12):1263-1275. doi: 10.1002/pds.2037. PubMed

15. Mellesdal L, Mehlum L, Wentzel-Larsen T, Kroken R, Jørgensen HA. Suicide risk and acute psychiatric readmissions: a prospective cohort study. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61(1):25-31. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.25. PubMed

16. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. Measure: Pediatric All-Condition Readmission Measure Measure Developer: Center of Excellence for Pediatric Quality Measurement (CEPQM). https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/policymakers/chipra/factsheets/chipra_14-p008-1-ef.pdf. Accessed November 15, 2017.

17. Cancino RS, Culpepper L, Sadikova E, Martin J, Jack BW, Mitchell SE. Dose-response relationship between depressive symptoms and hospital readmission. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(6):358-364. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2180. PubMed

18. Carlisle CE, Mamdani M, Schachar R, To T. Aftercare, emergency department visits, and readmission in adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(3):283-293. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0890856711011002. Accessed November 2, 2015. PubMed

19. Fadum EA, Stanley B, Qin P, Diep LM, Mehlum L. Self-poisoning with medications in adolescents: a national register study of hospital admissions and readmissions. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36(6):709-715. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2014.09.004. PubMed

20. Bernet AC. Predictors of psychiatric readmission among veterans at high risk of suicide: the impact of post-discharge aftercare. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2013;27(5):260-261. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2013.07.001. PubMed

21. Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14(1):199. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-14-199. PubMed

22. HCUP. HCUP-US Tools & Software Page. http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. Published 2015. Accessed October 30, 2015.

23. Zima BT, Rodean J, Hall M, Bardach NS, Coker TR, Berry JG. Psychiatric disorders and trends in resource use in pediatric hospitals. Pediatrics. 2016;138(5):e20160909-e20160909. doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0909. PubMed

24. Spicer RS, Miller TR. Suicide acts in 8 states: incidence and case fatality rates by demographics and method. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(12):1885-1891. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.90.12.1885. PubMed

25. Hansen B, Lang M. Back to school blues: Seasonality of youth suicide and the academic calendar. Econ Educ Rev. 2011;30(5):850-861. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2011.04.012.

26. Lueck C, Kearl L, Lam CN, Claudius I. Do emergency pediatric psychiatric visits for danger to self or others correspond to times of school attendance? Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(5):682-684. doi: 10.1016/J.AJEM.2015.02.055. PubMed

27. Healthcare Cost And Utilization Project. Introduction to the HCUP Nationwide Readmissions Database. Rockville, MD; 2017. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/db/nation/nrd/Introduction_NRD_2010-2014.pdf. Accessed November 14, 2017.

28. Bardach NS, Coker TR, Zima BT, et al. Common and costly hospitalizations for pediatric mental health disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(4):602-609. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3165. PubMed

29. Ahmedani BK, Peterson EL, Hu Y, et al. Major physical health conditions and risk of suicide. Am J Prev Med. 2017;53(3):308-315. doi: 10.1016/J.AMEPRE.2017.04.001. PubMed

30. Gunnell D, Hawton K, Ho D, et al. Hospital admissions for self harm after discharge from psychiatric inpatient care: cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2278. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a2278. PubMed

31. The TADS Team. The treatment for adolescents with depression study (TADS). Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(10):1132. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1132. PubMed

32. While D, Bickley H, Roscoe A, et al. Implementation of mental health service recommendations in England and Wales and suicide rates, 1997-2006: A cross-sectional and before-and-after observational study. Lancet. 2012;379(9820):1005-1012. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61712-1. PubMed

33. Kawanishi C, Aruga T, Ishizuka N, et al. Assertive case management versus enhanced usual care for people with mental health problems who had attempted suicide and were admitted to hospital emergency departments in Japan (ACTION-J): a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1(3):193-201. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70259-7. PubMed

34. Grupp-Phelan J, McGuire L, Husky MM, Olfson M. A randomized controlled trial to engage in care of adolescent emergency department patients with mental health problems that increase suicide risk. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2012;28(12):1263-1268. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0b013e3182767ac8. PubMed