User login

A Comparison of 4 Single-Question Measures of Patient Satisfaction

From Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: Satisfaction measures often show substantial ceiling effects. This randomized controlled trial tested the null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean overall satisfaction, ceiling and floor effect, and data distribution between 4 different kinds of single-question scales assessing the helpfulness of a visit. We also hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared with the Net Promoter Scores (NPS).

- Design: Randomized controlled trial.

- Methods: We enrolled 258 adult, English-speaking new and returning patients. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 different scale types: (1) an 11-point ordinal scale with 5 anchor points; (2) a 5-point Likert scale; (3) a 0-100 visual analogue scale (VAS) electronic slider with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; and (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers. Additionally, patients completed the 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2), 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression. We assessed mean and median score, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis for each scale. Spearman correlation tests were used to test correlations between satisfaction and psychological status.

- Results: The nonnumerical 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and the 5-point Likert scale had the least ceiling effect (12% and 20%, respectively). The 11-point ordinal scale had skewness and kurtosis closest to a normal distribution (skew = –0.58 and kurtosis = 4.0). Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064). NPS were 35, 16, 67, and 20 for the scales, respectively.

- Conclusion: Single-question measures of satisfaction can be adjusted to limit the ceiling effect. Additional research in this area is warranted.

Keywords: patient satisfaction; floor and ceiling effect; skewness and kurtosis; quality improvement.

Patient satisfaction is an important quality metric that is increasingly being measured, reported, and incentivized. A qualitative study identified 7 themes influencing satisfaction among people visiting an orthopedic surgeon’s office: trust, relatedness, expectations, wait time, visit duration, communication, and empathy.1 However, another study found that satisfaction and perceived empathy are not associated with wait time or visit duration, but rather with the quality of the visit.2 Satisfaction measures that incorporate many of these features in relatively long questionnaires are associated with lower response rates3 and overlap with the factors whose influence on satisfaction one would like to study (eg, perceived empathy or communication effectiveness).4 Single- and multiple-question satisfaction scores are prone to a strong right skew, with a substantial ceiling effect.5 Ceiling effect occurs when a considerable proportion (about half) of participants select 1 of the top 2 scores (or the maximum score). An ideal scale would measure satisfaction independent from other factors, would use 1 or just a few questions, and would have little or no ceiling effect.

In this randomized controlled trial, we examined whether there were significant differences in mean and median satisfaction, floor and ceiling effect, and data distribution (by looking at skewness and kurtosis) between 4 different kinds of satisfaction scales asking about the helpfulness of a visit. Additionally, we hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared to the Net Promoter Scores (NPS). NPS are commonly used in the service industry to measure customer satisfaction; we are using these scores as a measure of patient satisfaction.

Methods

Study Design

All English-speaking new and return patients ages 18 to 89 years visiting an orthopedic surgeon in 1 of 7 clinics located in a large urban area were considered eligible for this study. Enrollment took place intermittently over a 5-month period. We were granted a waiver of written informed consent. Patients indicated their consent by completing the surveys. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of the 4 questionnaires containing different scale types using an Excel random-number generator. After the visit, patients were asked to complete the survey. All questionnaires were administered on an encrypted tablet via a HIPAA-compliant, secure web-based application for building and managing online surveys and databases (REDCap; Research Electronic Data Capture).6 This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03686735).7

Outcome Measures

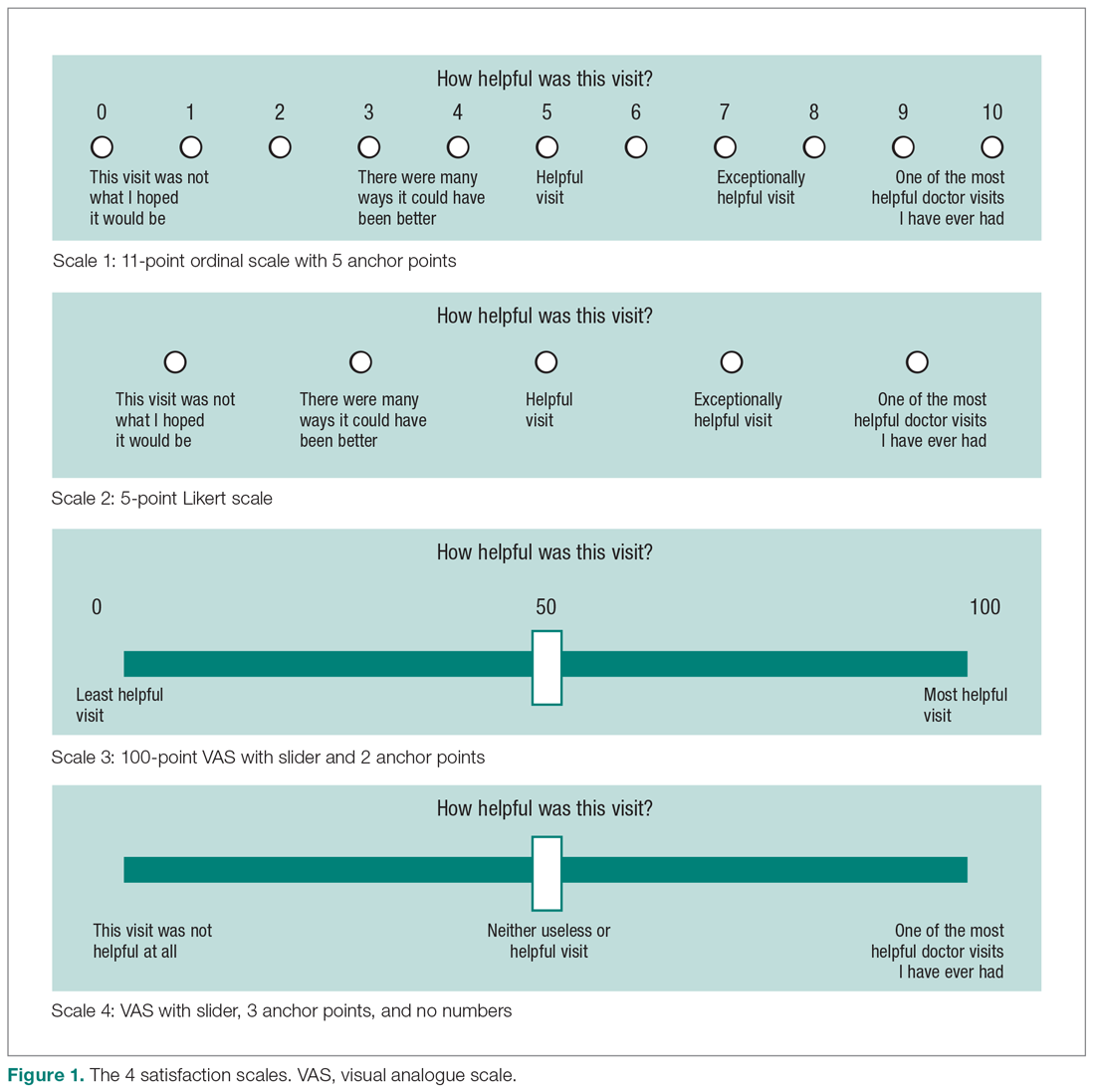

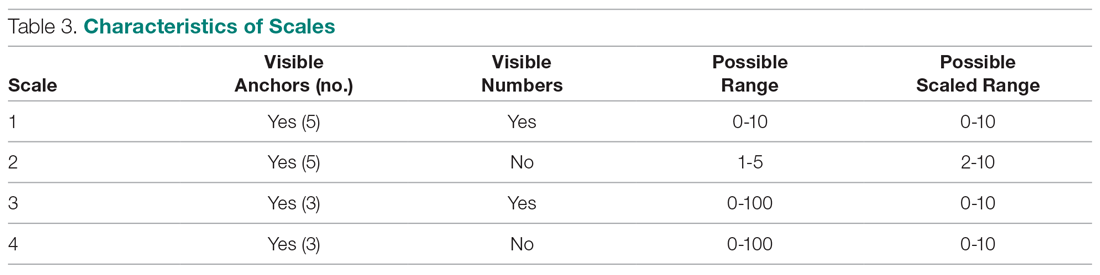

Study participants were asked to complete questionnaires regarding demographics (sex, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, level of education, work status, insurance status, comorbidities) and to rate satisfaction with their visit on the scale that was randomly assigned to them: (1) an 11-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers; (2) a 5-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and no visible numbers; (3) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers (Figure 1). The 4 scales should not differ in time needed to complete them; however, we did not explicitly measure time to completion. Participants also completed measures of psychological aspects of illness. The 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2) was used to measure pain self-efficacy, an effective coping strategy for pain.8 Higher PSEQ-2 scores indicate a higher level of pain self-efficacy. The 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5) was also administered; higher scores on this scale indicate a greater degree of health anxiety.9 The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression was used to measure symptoms of depression.10 Finally, the diagnosis was recorded by the surgeon (not in table).

Statistical Analysis

We reported continuous variables using mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. We calculated floor and ceiling effect and the skewness and kurtosis of every scale. We scaled every scale to 10 and also standardized every scale. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare differences in satisfaction between the scales; Fisher’s exact test to compare differences in floor and ceiling effect; and Spearman correlation tests to test the correlation between scaled satisfaction scores and psychological status.

Ceiling effects are present when patients select the highest value on a scale rather than a value that reflects their actual feelings about a certain topic. Floor effects are present when patients select the lowest value in a similar fashion. These 2 effects indicate that an independent variable no longer influences the dependent variable being tested. Skewness and kurtosis are rough indicators of a normal distribution of values. Skewness (γ1) is an index of the symmetry of a distribution, with symmetric distributions having a skewness of 0. If skewness has a positive value, it suggests relatively many low values, having a long right tail. Negative skewness suggests relatively many high values, having a long left tail. Kurtosis (γ2) is a measure to describe tailedness of a distribution. Kurtosis of a normal distribution is 3. Negative kurtosis represents little peaked distribution, and positive kurtosis represents more peaked distribution.11,12 If skewness is 0 and kurtosis is 3, there is a normal, or Gaussian, distribution.

Finally, we manually calculated the NPS for all scales by subtracting the percentage of detractors (people who scored between 0 and 6) from the percentage of promoters (people who scored 9 or 10).13 NPS are widely used in the service industry to assess customer satisfaction, and scores range between –100 and 100.

An a priori power analysis indicated that in order to find a difference in satisfaction of 0.5 on a 0-10 scale, with an effect size of 80% and alpha set at 0.05, we needed 128 patients (64 per group). Since we wanted to compare 4 satisfaction scales, we doubled this.

Results

Patient Characteristics

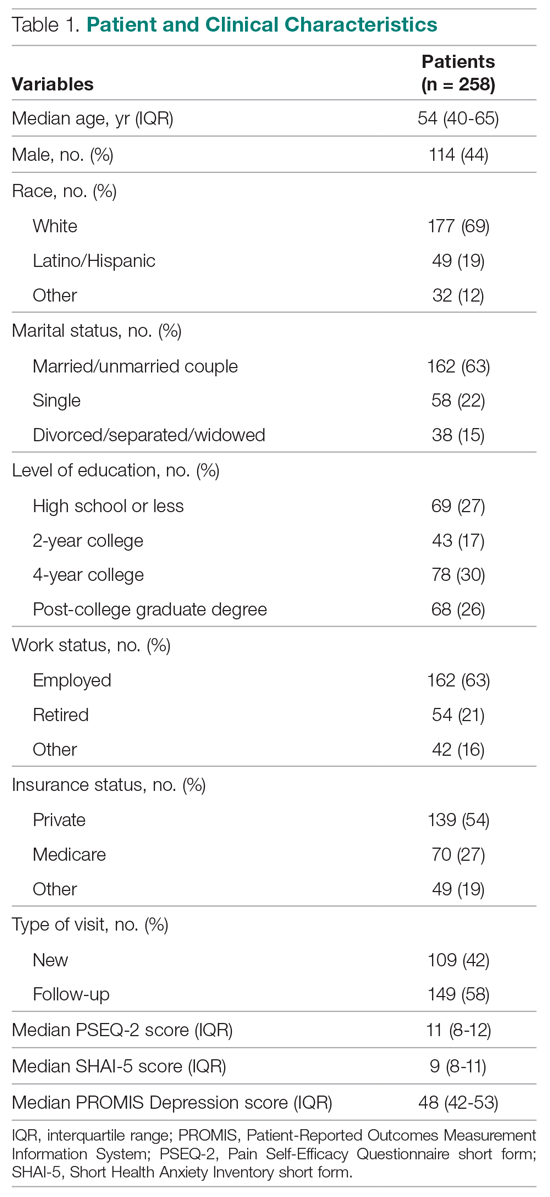

All patients invited to participate in this study agreed, and 258 patients with various diagnoses were enrolled. The median age of the cohort was 54 years (IQR, 40-65 years); 114 (44%) were men, and 119 (42%) were new patients (Table 1). The number of patients assigned to scales 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 62 (24%), 70 (27%), 67 (26%), and 59 (23%), respectively.

Difference in Distribution

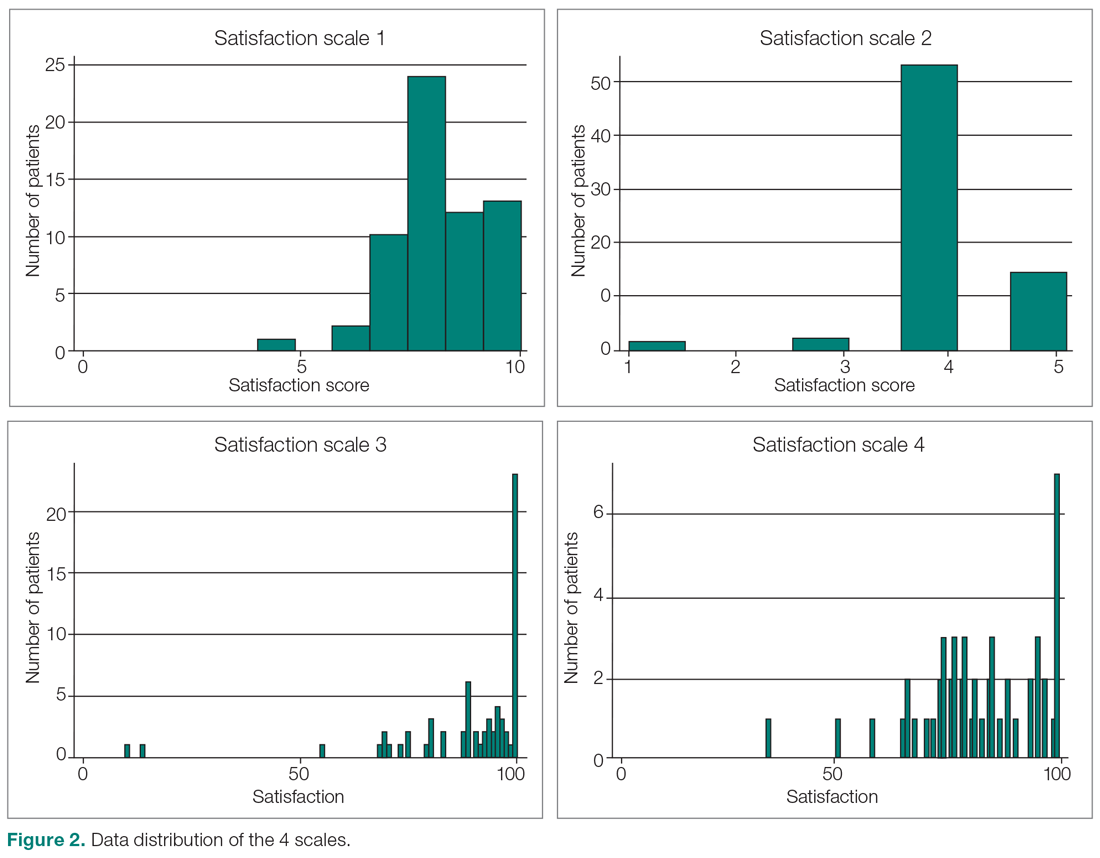

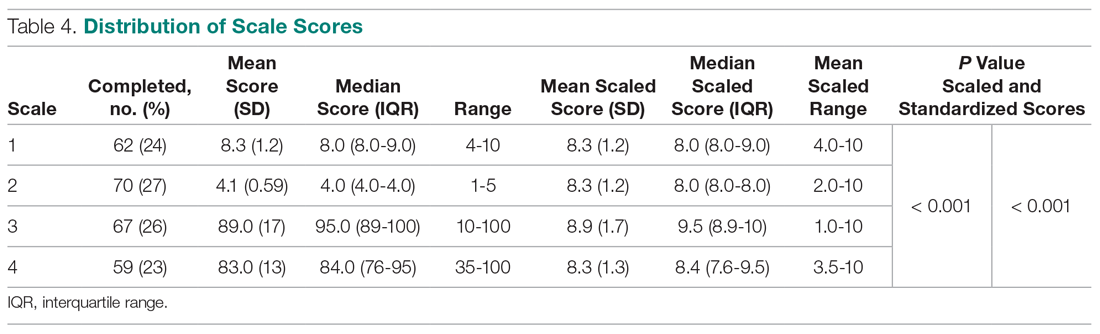

Looking at the data distribution (Figure 2) and skewness and kurtosis (Table 2) of the scales, we found that none of the scales was normally distributed.

Difference in Satisfaction Scores

Mean (SD) scaled satisfaction scores (range, 0-10) were 8.3 (1.2) for the 11-point ordinal scale, 8.3 (1.2) for the 5-point Likert scale, 8.9 (1.7) for the 0-100 numerical VAS, and 8.3 (1.3) for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS (Table 3 and Table 4).

Difference in Floor and Ceiling Effect

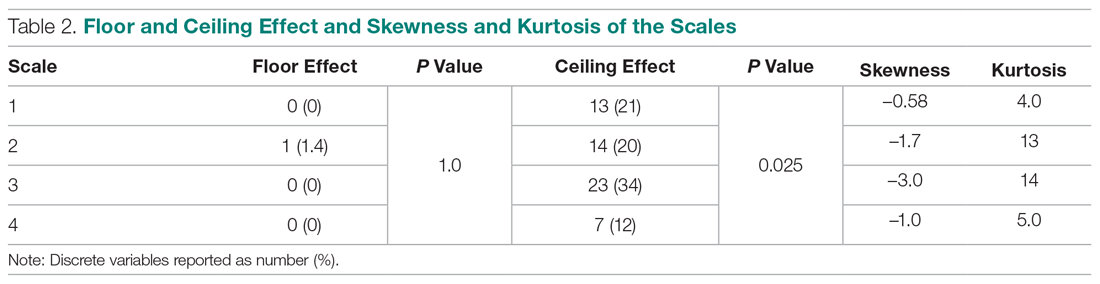

A difference was found in ceiling effect between the different scales (P = 0.025), with the 0-100 numerical VAS showing the highest ceiling effect (34%) and the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS showing the lowest ceiling effect (12%; Table 2). There was no floor effect. A single patient used the lowest score (on the Likert scale).

Correlation Between Satisfaction and Psychological Status

Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064; not in table), indicating that patients with more self-efficacy had higher satisfaction ratings.

Net Promoter Scores

NPS were 35 for the 11-point ordinal scale; 16 for the 5-point Likert scale; 67 for the 0-100 numerical VAS; and 20 for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS.

Discussion

Single-question measures of satisfaction can decrease patient burden and limit overlap with measures of communication effectiveness and perceived empathy. Both long and short questionnaires addressing satisfaction and perceived empathy show substantial ceiling effect. We compared 4 different measures for overall scores, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis, and assessed the correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. We found that scale type influenced the median helpfulness score. As one would expect, scales with less ceiling effect have lower median scores. In other words, if the goal is to collect meaningful information and identify areas for improvement, there must be a willingness to accept lower scores.

Only the nonnumerical VAS was below the threshold of 15% ceiling effect proposed by Terwee et al.14 This scale with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers showed the least ceiling effect (12%) and minimal skew (–1.0), and was closer to kurtosis consistent with a normal distribution (5.0). However, the 11-point ordinal Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers had the lowest skewness and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0). The low ceiling effect observed with the nonnumerical VAS (12%) might be explained by the fact that the scale does not lead patients to a specific description of the helpfulness of their visit, but rather asks patients to use their own judgement in making the rating. The ordinal scale approached the most normal data distribution, and this might be explained by the presence of numbers on the scale. Ratings based on a 0-10 scale are commonly used, and familiarity with the system might have allowed people to pick a number that represents their actual view of the visit helpfulness, rather than picking the highest possible choice (which would have led to a ceiling effect). Study results comparing Likert scales and VAS are conflicting,15 with some preferring Likert scales for their responsiveness16 and ease of use in practice,17 and others preferring VAS for their sensitivity to describe continuous, subjective phenomenon and their high validity and reliability.18 Looking at our nonnumerical VAS, adding numbers to a scale might not help avoid, and may actually increase, the presence of ceiling effect. However, with the ordinal scale with visible numbers, we saw a 21% ceiling effect coupled with low skew and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0), which indicate that the distribution of scores is relatively normal. This finding is in line with other study results.19

Our findings demonstrated that feedback concerning self-efficacy, health anxiety, or depression had no or only a small effect on patient satisfaction. Consistent with prior evidence, psychological factors had limited or no correlation with satisfaction.20-24 Given the effect that priming has on patient-reported outcome measures, the effect of psychological factors on satisfaction could be an area of future study.

The NPS varied substantially based on scale structure. Increasing the spread of the scores to limit the ceiling effect will likely reduce promoters and detractors and increase neutrals. NPS systems have been used in the past to measure patient satisfaction with common hand surgery techniques and with community mental health services.25,26 These studies suggest that NPS could be a helpful addition to commonly used clinical measures of satisfaction, after more research has been done to validate it. The evidence showing that NPS are strongly influenced by scale structure suggests that NPS should be used and interpreted with caution.

Several caveats regarding this study should be kept in mind. This study specifically addressed ratings of visit helpfulness. Differently phrased questions might lead to different results. More work is needed to determine the essence of satisfaction with a medical visit.1 In addition, the majority of our patient population was white, employed, and privately insured, limiting generalizability to other populations with different demographics. Finally, all patients were seen by an orthopedic surgeon, and our results might not apply to other populations or clinical settings. However, given the scope of this study, we suspect that the findings can be generalized to specialty care in general and likely all medical contexts.

Conclusion

It is clear from this work that scale design can affect ceiling effect. We plan to test alternative phrasings and structures of single-question measures of satisfaction with a medical visit so that we can better study what factors contribute to satisfaction. It is notable that this approach runs counter to efforts to improve satisfaction scores, because reducing the ceiling effect reduces the mean score and may contribute to worse NPS. Further study is needed to find the optimal measure to assess satisfaction ratings.

Corresponding author: David Ring, MD, PhD, 1701 Trinity Street, Austin, TX, 78712; david.ring@austin.utexas.edu.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Ring has or may receive payment or benefits from Skeletal Dynamics; Wright Medical Group; the journal Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; and universities, hospitals, and lawyers not related to the submitted work.

1. Waters S, Edmondston SJ, Yates PJ, Gucciardi DF. Identification of factors influencing patient satisfaction with orthopaedic outpatient clinic consultation: A qualitative study. Man Ther. 2016;25:48-55.

2. Kortlever JTP, Ottenhoff JSE, Vagner GA, et al. Visit duration does not correlate with perceived physician empathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:296-301.

3. Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Methods to influence response to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001(3):CD003227.

4. Salisbury C, Burgess A, Lattimer V, et al. Developing a standard short questionnaire for the assessment of patient satisfaction with out-of-hours primary care. Fam Pract. 2005;22:560-569.

5. Ross CK, Steward CA, Sinacore JM. A comparative study of seven measures of patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1995;33:392-406.

6. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381.

7. Medicine USNLo. ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed March 18, 2019.

8. Nicholas MK, McGuire BE, Asghari A. A 2-item short form of the Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire: development and psychometric evaluation of PSEQ-2. J Pain. 2015;16:153-163.

9. Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick H, Clark D. The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32:843-853.

10. Schalet BD, Pilkonis PA, Yu L, et al. Clinical validity of PROMIS depression, anxiety, and anger across diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:119-127.

11. Ho AD, Yu CC. Descriptive statistics for modern test score distributions: skewness, kurtosis, discreteness, and ceiling effects. Educ Psychol Meas. 2015;75:365-388.

12. Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38:52-54.

13. NICE Satmetrix. What is net promoter? https://www.netpromoter.com/know/. Accessed March 18, 2019.

14. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34-42.

15. Hasson D, Arnetz BB. Validation and findings comparing VAS vs. Likert scales for psychosocial measurements. Int Electronic J Health Educ. 2005;8:178-192.

16. Vickers AJ. Comparison of an ordinal and a continuous outcome measure of muscle soreness. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1999;15:709-716.

17. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. A comparison of seven-point and visual analogue scales: data from a randomized trial. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:43-51.

18. Voutilainen A, Pitkaaho T, Kvist T, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. How to ask about patient satisfaction? The visual analogue scale is less vulnerable to confounding factors and ceiling effect than a symmetric Likert scale. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:946-957.

19. Brunelli C, Zecca E, Martini C, et al. Comparison of numerical and verbal rating scales to measure pain exacerbations in patients with chronic cancer pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:42.

20. Hageman MG, Briet JP, Bossen JK, et al. Do previsit expectations correlate with satisfaction of new patients presenting for evaluation with an orthopaedic surgical practice? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:716-721.

21. Keulen MHF, Teunis T, Vagner GA, et al. The effect of the content of patient-reported outcome measures on patient perceived empathy and satisfaction: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:1141.e1-e9.

22. Mellema JJ, O’Connor CM, Overbeek CL, et al. The effect of feedback regarding coping strategies and illness behavior on hand surgery patient satisfaction and communication: a randomized controlled trial. Hand. 2015;10:503-511.

23. Tyser AR, Gaffney CJ, Zhang C, Presson AP. The association of patient satisfaction with pain, anxiety, and self-reported physical function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1811-1818.

24. Vranceanu AM, Ring D. Factors associated with patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1504-1508.

25. Stirling P, Jenkins PJ, Clement ND, et al. The Net Promoter Scores with Friends and Family Test after four hand surgery procedures. J Hand Surg Eur. 2019;44:290-295.

26. Wilberforce M, Poll S, Langham H, et al. Measuring the patient experience in community mental health services for older people: A study of the Net Promoter Score using the Friends and Family Test in England. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:31-37.

From Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: Satisfaction measures often show substantial ceiling effects. This randomized controlled trial tested the null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean overall satisfaction, ceiling and floor effect, and data distribution between 4 different kinds of single-question scales assessing the helpfulness of a visit. We also hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared with the Net Promoter Scores (NPS).

- Design: Randomized controlled trial.

- Methods: We enrolled 258 adult, English-speaking new and returning patients. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 different scale types: (1) an 11-point ordinal scale with 5 anchor points; (2) a 5-point Likert scale; (3) a 0-100 visual analogue scale (VAS) electronic slider with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; and (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers. Additionally, patients completed the 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2), 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression. We assessed mean and median score, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis for each scale. Spearman correlation tests were used to test correlations between satisfaction and psychological status.

- Results: The nonnumerical 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and the 5-point Likert scale had the least ceiling effect (12% and 20%, respectively). The 11-point ordinal scale had skewness and kurtosis closest to a normal distribution (skew = –0.58 and kurtosis = 4.0). Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064). NPS were 35, 16, 67, and 20 for the scales, respectively.

- Conclusion: Single-question measures of satisfaction can be adjusted to limit the ceiling effect. Additional research in this area is warranted.

Keywords: patient satisfaction; floor and ceiling effect; skewness and kurtosis; quality improvement.

Patient satisfaction is an important quality metric that is increasingly being measured, reported, and incentivized. A qualitative study identified 7 themes influencing satisfaction among people visiting an orthopedic surgeon’s office: trust, relatedness, expectations, wait time, visit duration, communication, and empathy.1 However, another study found that satisfaction and perceived empathy are not associated with wait time or visit duration, but rather with the quality of the visit.2 Satisfaction measures that incorporate many of these features in relatively long questionnaires are associated with lower response rates3 and overlap with the factors whose influence on satisfaction one would like to study (eg, perceived empathy or communication effectiveness).4 Single- and multiple-question satisfaction scores are prone to a strong right skew, with a substantial ceiling effect.5 Ceiling effect occurs when a considerable proportion (about half) of participants select 1 of the top 2 scores (or the maximum score). An ideal scale would measure satisfaction independent from other factors, would use 1 or just a few questions, and would have little or no ceiling effect.

In this randomized controlled trial, we examined whether there were significant differences in mean and median satisfaction, floor and ceiling effect, and data distribution (by looking at skewness and kurtosis) between 4 different kinds of satisfaction scales asking about the helpfulness of a visit. Additionally, we hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared to the Net Promoter Scores (NPS). NPS are commonly used in the service industry to measure customer satisfaction; we are using these scores as a measure of patient satisfaction.

Methods

Study Design

All English-speaking new and return patients ages 18 to 89 years visiting an orthopedic surgeon in 1 of 7 clinics located in a large urban area were considered eligible for this study. Enrollment took place intermittently over a 5-month period. We were granted a waiver of written informed consent. Patients indicated their consent by completing the surveys. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of the 4 questionnaires containing different scale types using an Excel random-number generator. After the visit, patients were asked to complete the survey. All questionnaires were administered on an encrypted tablet via a HIPAA-compliant, secure web-based application for building and managing online surveys and databases (REDCap; Research Electronic Data Capture).6 This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03686735).7

Outcome Measures

Study participants were asked to complete questionnaires regarding demographics (sex, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, level of education, work status, insurance status, comorbidities) and to rate satisfaction with their visit on the scale that was randomly assigned to them: (1) an 11-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers; (2) a 5-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and no visible numbers; (3) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers (Figure 1). The 4 scales should not differ in time needed to complete them; however, we did not explicitly measure time to completion. Participants also completed measures of psychological aspects of illness. The 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2) was used to measure pain self-efficacy, an effective coping strategy for pain.8 Higher PSEQ-2 scores indicate a higher level of pain self-efficacy. The 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5) was also administered; higher scores on this scale indicate a greater degree of health anxiety.9 The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression was used to measure symptoms of depression.10 Finally, the diagnosis was recorded by the surgeon (not in table).

Statistical Analysis

We reported continuous variables using mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. We calculated floor and ceiling effect and the skewness and kurtosis of every scale. We scaled every scale to 10 and also standardized every scale. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare differences in satisfaction between the scales; Fisher’s exact test to compare differences in floor and ceiling effect; and Spearman correlation tests to test the correlation between scaled satisfaction scores and psychological status.

Ceiling effects are present when patients select the highest value on a scale rather than a value that reflects their actual feelings about a certain topic. Floor effects are present when patients select the lowest value in a similar fashion. These 2 effects indicate that an independent variable no longer influences the dependent variable being tested. Skewness and kurtosis are rough indicators of a normal distribution of values. Skewness (γ1) is an index of the symmetry of a distribution, with symmetric distributions having a skewness of 0. If skewness has a positive value, it suggests relatively many low values, having a long right tail. Negative skewness suggests relatively many high values, having a long left tail. Kurtosis (γ2) is a measure to describe tailedness of a distribution. Kurtosis of a normal distribution is 3. Negative kurtosis represents little peaked distribution, and positive kurtosis represents more peaked distribution.11,12 If skewness is 0 and kurtosis is 3, there is a normal, or Gaussian, distribution.

Finally, we manually calculated the NPS for all scales by subtracting the percentage of detractors (people who scored between 0 and 6) from the percentage of promoters (people who scored 9 or 10).13 NPS are widely used in the service industry to assess customer satisfaction, and scores range between –100 and 100.

An a priori power analysis indicated that in order to find a difference in satisfaction of 0.5 on a 0-10 scale, with an effect size of 80% and alpha set at 0.05, we needed 128 patients (64 per group). Since we wanted to compare 4 satisfaction scales, we doubled this.

Results

Patient Characteristics

All patients invited to participate in this study agreed, and 258 patients with various diagnoses were enrolled. The median age of the cohort was 54 years (IQR, 40-65 years); 114 (44%) were men, and 119 (42%) were new patients (Table 1). The number of patients assigned to scales 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 62 (24%), 70 (27%), 67 (26%), and 59 (23%), respectively.

Difference in Distribution

Looking at the data distribution (Figure 2) and skewness and kurtosis (Table 2) of the scales, we found that none of the scales was normally distributed.

Difference in Satisfaction Scores

Mean (SD) scaled satisfaction scores (range, 0-10) were 8.3 (1.2) for the 11-point ordinal scale, 8.3 (1.2) for the 5-point Likert scale, 8.9 (1.7) for the 0-100 numerical VAS, and 8.3 (1.3) for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS (Table 3 and Table 4).

Difference in Floor and Ceiling Effect

A difference was found in ceiling effect between the different scales (P = 0.025), with the 0-100 numerical VAS showing the highest ceiling effect (34%) and the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS showing the lowest ceiling effect (12%; Table 2). There was no floor effect. A single patient used the lowest score (on the Likert scale).

Correlation Between Satisfaction and Psychological Status

Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064; not in table), indicating that patients with more self-efficacy had higher satisfaction ratings.

Net Promoter Scores

NPS were 35 for the 11-point ordinal scale; 16 for the 5-point Likert scale; 67 for the 0-100 numerical VAS; and 20 for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS.

Discussion

Single-question measures of satisfaction can decrease patient burden and limit overlap with measures of communication effectiveness and perceived empathy. Both long and short questionnaires addressing satisfaction and perceived empathy show substantial ceiling effect. We compared 4 different measures for overall scores, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis, and assessed the correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. We found that scale type influenced the median helpfulness score. As one would expect, scales with less ceiling effect have lower median scores. In other words, if the goal is to collect meaningful information and identify areas for improvement, there must be a willingness to accept lower scores.

Only the nonnumerical VAS was below the threshold of 15% ceiling effect proposed by Terwee et al.14 This scale with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers showed the least ceiling effect (12%) and minimal skew (–1.0), and was closer to kurtosis consistent with a normal distribution (5.0). However, the 11-point ordinal Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers had the lowest skewness and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0). The low ceiling effect observed with the nonnumerical VAS (12%) might be explained by the fact that the scale does not lead patients to a specific description of the helpfulness of their visit, but rather asks patients to use their own judgement in making the rating. The ordinal scale approached the most normal data distribution, and this might be explained by the presence of numbers on the scale. Ratings based on a 0-10 scale are commonly used, and familiarity with the system might have allowed people to pick a number that represents their actual view of the visit helpfulness, rather than picking the highest possible choice (which would have led to a ceiling effect). Study results comparing Likert scales and VAS are conflicting,15 with some preferring Likert scales for their responsiveness16 and ease of use in practice,17 and others preferring VAS for their sensitivity to describe continuous, subjective phenomenon and their high validity and reliability.18 Looking at our nonnumerical VAS, adding numbers to a scale might not help avoid, and may actually increase, the presence of ceiling effect. However, with the ordinal scale with visible numbers, we saw a 21% ceiling effect coupled with low skew and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0), which indicate that the distribution of scores is relatively normal. This finding is in line with other study results.19

Our findings demonstrated that feedback concerning self-efficacy, health anxiety, or depression had no or only a small effect on patient satisfaction. Consistent with prior evidence, psychological factors had limited or no correlation with satisfaction.20-24 Given the effect that priming has on patient-reported outcome measures, the effect of psychological factors on satisfaction could be an area of future study.

The NPS varied substantially based on scale structure. Increasing the spread of the scores to limit the ceiling effect will likely reduce promoters and detractors and increase neutrals. NPS systems have been used in the past to measure patient satisfaction with common hand surgery techniques and with community mental health services.25,26 These studies suggest that NPS could be a helpful addition to commonly used clinical measures of satisfaction, after more research has been done to validate it. The evidence showing that NPS are strongly influenced by scale structure suggests that NPS should be used and interpreted with caution.

Several caveats regarding this study should be kept in mind. This study specifically addressed ratings of visit helpfulness. Differently phrased questions might lead to different results. More work is needed to determine the essence of satisfaction with a medical visit.1 In addition, the majority of our patient population was white, employed, and privately insured, limiting generalizability to other populations with different demographics. Finally, all patients were seen by an orthopedic surgeon, and our results might not apply to other populations or clinical settings. However, given the scope of this study, we suspect that the findings can be generalized to specialty care in general and likely all medical contexts.

Conclusion

It is clear from this work that scale design can affect ceiling effect. We plan to test alternative phrasings and structures of single-question measures of satisfaction with a medical visit so that we can better study what factors contribute to satisfaction. It is notable that this approach runs counter to efforts to improve satisfaction scores, because reducing the ceiling effect reduces the mean score and may contribute to worse NPS. Further study is needed to find the optimal measure to assess satisfaction ratings.

Corresponding author: David Ring, MD, PhD, 1701 Trinity Street, Austin, TX, 78712; david.ring@austin.utexas.edu.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Ring has or may receive payment or benefits from Skeletal Dynamics; Wright Medical Group; the journal Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; and universities, hospitals, and lawyers not related to the submitted work.

From Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX.

Abstract

- Objective: Satisfaction measures often show substantial ceiling effects. This randomized controlled trial tested the null hypothesis that there is no difference in mean overall satisfaction, ceiling and floor effect, and data distribution between 4 different kinds of single-question scales assessing the helpfulness of a visit. We also hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared with the Net Promoter Scores (NPS).

- Design: Randomized controlled trial.

- Methods: We enrolled 258 adult, English-speaking new and returning patients. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of 4 different scale types: (1) an 11-point ordinal scale with 5 anchor points; (2) a 5-point Likert scale; (3) a 0-100 visual analogue scale (VAS) electronic slider with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; and (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers. Additionally, patients completed the 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2), 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5), and Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression. We assessed mean and median score, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis for each scale. Spearman correlation tests were used to test correlations between satisfaction and psychological status.

- Results: The nonnumerical 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and the 5-point Likert scale had the least ceiling effect (12% and 20%, respectively). The 11-point ordinal scale had skewness and kurtosis closest to a normal distribution (skew = –0.58 and kurtosis = 4.0). Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064). NPS were 35, 16, 67, and 20 for the scales, respectively.

- Conclusion: Single-question measures of satisfaction can be adjusted to limit the ceiling effect. Additional research in this area is warranted.

Keywords: patient satisfaction; floor and ceiling effect; skewness and kurtosis; quality improvement.

Patient satisfaction is an important quality metric that is increasingly being measured, reported, and incentivized. A qualitative study identified 7 themes influencing satisfaction among people visiting an orthopedic surgeon’s office: trust, relatedness, expectations, wait time, visit duration, communication, and empathy.1 However, another study found that satisfaction and perceived empathy are not associated with wait time or visit duration, but rather with the quality of the visit.2 Satisfaction measures that incorporate many of these features in relatively long questionnaires are associated with lower response rates3 and overlap with the factors whose influence on satisfaction one would like to study (eg, perceived empathy or communication effectiveness).4 Single- and multiple-question satisfaction scores are prone to a strong right skew, with a substantial ceiling effect.5 Ceiling effect occurs when a considerable proportion (about half) of participants select 1 of the top 2 scores (or the maximum score). An ideal scale would measure satisfaction independent from other factors, would use 1 or just a few questions, and would have little or no ceiling effect.

In this randomized controlled trial, we examined whether there were significant differences in mean and median satisfaction, floor and ceiling effect, and data distribution (by looking at skewness and kurtosis) between 4 different kinds of satisfaction scales asking about the helpfulness of a visit. Additionally, we hypothesized that there is no correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. Finally, we assessed how the satisfaction scores compared to the Net Promoter Scores (NPS). NPS are commonly used in the service industry to measure customer satisfaction; we are using these scores as a measure of patient satisfaction.

Methods

Study Design

All English-speaking new and return patients ages 18 to 89 years visiting an orthopedic surgeon in 1 of 7 clinics located in a large urban area were considered eligible for this study. Enrollment took place intermittently over a 5-month period. We were granted a waiver of written informed consent. Patients indicated their consent by completing the surveys. Patients were randomly assigned to 1 of the 4 questionnaires containing different scale types using an Excel random-number generator. After the visit, patients were asked to complete the survey. All questionnaires were administered on an encrypted tablet via a HIPAA-compliant, secure web-based application for building and managing online surveys and databases (REDCap; Research Electronic Data Capture).6 This study was approved by our Institutional Review Board and is registered on ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT03686735).7

Outcome Measures

Study participants were asked to complete questionnaires regarding demographics (sex, age, race/ethnicity, marital status, level of education, work status, insurance status, comorbidities) and to rate satisfaction with their visit on the scale that was randomly assigned to them: (1) an 11-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers; (2) a 5-point Likert scale with 5 anchor points and no visible numbers; (3) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and visible numbers; (4) a 0-100 VAS with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers (Figure 1). The 4 scales should not differ in time needed to complete them; however, we did not explicitly measure time to completion. Participants also completed measures of psychological aspects of illness. The 2-item Pain Self-Efficacy Questionnaire (PSEQ-2) was used to measure pain self-efficacy, an effective coping strategy for pain.8 Higher PSEQ-2 scores indicate a higher level of pain self-efficacy. The 5-item Short Health Anxiety Inventory scale (SHAI-5) was also administered; higher scores on this scale indicate a greater degree of health anxiety.9 The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Depression was used to measure symptoms of depression.10 Finally, the diagnosis was recorded by the surgeon (not in table).

Statistical Analysis

We reported continuous variables using mean, standard deviation (SD), median, and interquartile range (IQR). Categorical data are presented as frequencies and percentages. We calculated floor and ceiling effect and the skewness and kurtosis of every scale. We scaled every scale to 10 and also standardized every scale. We used the Kruskal–Wallis test to compare differences in satisfaction between the scales; Fisher’s exact test to compare differences in floor and ceiling effect; and Spearman correlation tests to test the correlation between scaled satisfaction scores and psychological status.

Ceiling effects are present when patients select the highest value on a scale rather than a value that reflects their actual feelings about a certain topic. Floor effects are present when patients select the lowest value in a similar fashion. These 2 effects indicate that an independent variable no longer influences the dependent variable being tested. Skewness and kurtosis are rough indicators of a normal distribution of values. Skewness (γ1) is an index of the symmetry of a distribution, with symmetric distributions having a skewness of 0. If skewness has a positive value, it suggests relatively many low values, having a long right tail. Negative skewness suggests relatively many high values, having a long left tail. Kurtosis (γ2) is a measure to describe tailedness of a distribution. Kurtosis of a normal distribution is 3. Negative kurtosis represents little peaked distribution, and positive kurtosis represents more peaked distribution.11,12 If skewness is 0 and kurtosis is 3, there is a normal, or Gaussian, distribution.

Finally, we manually calculated the NPS for all scales by subtracting the percentage of detractors (people who scored between 0 and 6) from the percentage of promoters (people who scored 9 or 10).13 NPS are widely used in the service industry to assess customer satisfaction, and scores range between –100 and 100.

An a priori power analysis indicated that in order to find a difference in satisfaction of 0.5 on a 0-10 scale, with an effect size of 80% and alpha set at 0.05, we needed 128 patients (64 per group). Since we wanted to compare 4 satisfaction scales, we doubled this.

Results

Patient Characteristics

All patients invited to participate in this study agreed, and 258 patients with various diagnoses were enrolled. The median age of the cohort was 54 years (IQR, 40-65 years); 114 (44%) were men, and 119 (42%) were new patients (Table 1). The number of patients assigned to scales 1, 2, 3, and 4 were 62 (24%), 70 (27%), 67 (26%), and 59 (23%), respectively.

Difference in Distribution

Looking at the data distribution (Figure 2) and skewness and kurtosis (Table 2) of the scales, we found that none of the scales was normally distributed.

Difference in Satisfaction Scores

Mean (SD) scaled satisfaction scores (range, 0-10) were 8.3 (1.2) for the 11-point ordinal scale, 8.3 (1.2) for the 5-point Likert scale, 8.9 (1.7) for the 0-100 numerical VAS, and 8.3 (1.3) for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS (Table 3 and Table 4).

Difference in Floor and Ceiling Effect

A difference was found in ceiling effect between the different scales (P = 0.025), with the 0-100 numerical VAS showing the highest ceiling effect (34%) and the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS showing the lowest ceiling effect (12%; Table 2). There was no floor effect. A single patient used the lowest score (on the Likert scale).

Correlation Between Satisfaction and Psychological Status

Scaled satisfaction scores had a small but significant correlation with PSEQ-2 (r = 0.17; P = 0.006), but not with SHAI-5 (r = –0.12; P = 0.052) or PROMIS Depression (r = –0.12; P = 0.064; not in table), indicating that patients with more self-efficacy had higher satisfaction ratings.

Net Promoter Scores

NPS were 35 for the 11-point ordinal scale; 16 for the 5-point Likert scale; 67 for the 0-100 numerical VAS; and 20 for the 0-100 nonnumerical VAS.

Discussion

Single-question measures of satisfaction can decrease patient burden and limit overlap with measures of communication effectiveness and perceived empathy. Both long and short questionnaires addressing satisfaction and perceived empathy show substantial ceiling effect. We compared 4 different measures for overall scores, floor and ceiling effect, and skewness and kurtosis, and assessed the correlation between scaled satisfaction and psychological status. We found that scale type influenced the median helpfulness score. As one would expect, scales with less ceiling effect have lower median scores. In other words, if the goal is to collect meaningful information and identify areas for improvement, there must be a willingness to accept lower scores.

Only the nonnumerical VAS was below the threshold of 15% ceiling effect proposed by Terwee et al.14 This scale with 3 anchor points and no visible numbers showed the least ceiling effect (12%) and minimal skew (–1.0), and was closer to kurtosis consistent with a normal distribution (5.0). However, the 11-point ordinal Likert scale with 5 anchor points and visible numbers had the lowest skewness and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0). The low ceiling effect observed with the nonnumerical VAS (12%) might be explained by the fact that the scale does not lead patients to a specific description of the helpfulness of their visit, but rather asks patients to use their own judgement in making the rating. The ordinal scale approached the most normal data distribution, and this might be explained by the presence of numbers on the scale. Ratings based on a 0-10 scale are commonly used, and familiarity with the system might have allowed people to pick a number that represents their actual view of the visit helpfulness, rather than picking the highest possible choice (which would have led to a ceiling effect). Study results comparing Likert scales and VAS are conflicting,15 with some preferring Likert scales for their responsiveness16 and ease of use in practice,17 and others preferring VAS for their sensitivity to describe continuous, subjective phenomenon and their high validity and reliability.18 Looking at our nonnumerical VAS, adding numbers to a scale might not help avoid, and may actually increase, the presence of ceiling effect. However, with the ordinal scale with visible numbers, we saw a 21% ceiling effect coupled with low skew and kurtosis (–0.58 and 4.0), which indicate that the distribution of scores is relatively normal. This finding is in line with other study results.19

Our findings demonstrated that feedback concerning self-efficacy, health anxiety, or depression had no or only a small effect on patient satisfaction. Consistent with prior evidence, psychological factors had limited or no correlation with satisfaction.20-24 Given the effect that priming has on patient-reported outcome measures, the effect of psychological factors on satisfaction could be an area of future study.

The NPS varied substantially based on scale structure. Increasing the spread of the scores to limit the ceiling effect will likely reduce promoters and detractors and increase neutrals. NPS systems have been used in the past to measure patient satisfaction with common hand surgery techniques and with community mental health services.25,26 These studies suggest that NPS could be a helpful addition to commonly used clinical measures of satisfaction, after more research has been done to validate it. The evidence showing that NPS are strongly influenced by scale structure suggests that NPS should be used and interpreted with caution.

Several caveats regarding this study should be kept in mind. This study specifically addressed ratings of visit helpfulness. Differently phrased questions might lead to different results. More work is needed to determine the essence of satisfaction with a medical visit.1 In addition, the majority of our patient population was white, employed, and privately insured, limiting generalizability to other populations with different demographics. Finally, all patients were seen by an orthopedic surgeon, and our results might not apply to other populations or clinical settings. However, given the scope of this study, we suspect that the findings can be generalized to specialty care in general and likely all medical contexts.

Conclusion

It is clear from this work that scale design can affect ceiling effect. We plan to test alternative phrasings and structures of single-question measures of satisfaction with a medical visit so that we can better study what factors contribute to satisfaction. It is notable that this approach runs counter to efforts to improve satisfaction scores, because reducing the ceiling effect reduces the mean score and may contribute to worse NPS. Further study is needed to find the optimal measure to assess satisfaction ratings.

Corresponding author: David Ring, MD, PhD, 1701 Trinity Street, Austin, TX, 78712; david.ring@austin.utexas.edu.

Financial disclosures: Dr. Ring has or may receive payment or benefits from Skeletal Dynamics; Wright Medical Group; the journal Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; and universities, hospitals, and lawyers not related to the submitted work.

1. Waters S, Edmondston SJ, Yates PJ, Gucciardi DF. Identification of factors influencing patient satisfaction with orthopaedic outpatient clinic consultation: A qualitative study. Man Ther. 2016;25:48-55.

2. Kortlever JTP, Ottenhoff JSE, Vagner GA, et al. Visit duration does not correlate with perceived physician empathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:296-301.

3. Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Methods to influence response to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001(3):CD003227.

4. Salisbury C, Burgess A, Lattimer V, et al. Developing a standard short questionnaire for the assessment of patient satisfaction with out-of-hours primary care. Fam Pract. 2005;22:560-569.

5. Ross CK, Steward CA, Sinacore JM. A comparative study of seven measures of patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1995;33:392-406.

6. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381.

7. Medicine USNLo. ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed March 18, 2019.

8. Nicholas MK, McGuire BE, Asghari A. A 2-item short form of the Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire: development and psychometric evaluation of PSEQ-2. J Pain. 2015;16:153-163.

9. Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick H, Clark D. The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32:843-853.

10. Schalet BD, Pilkonis PA, Yu L, et al. Clinical validity of PROMIS depression, anxiety, and anger across diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:119-127.

11. Ho AD, Yu CC. Descriptive statistics for modern test score distributions: skewness, kurtosis, discreteness, and ceiling effects. Educ Psychol Meas. 2015;75:365-388.

12. Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38:52-54.

13. NICE Satmetrix. What is net promoter? https://www.netpromoter.com/know/. Accessed March 18, 2019.

14. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34-42.

15. Hasson D, Arnetz BB. Validation and findings comparing VAS vs. Likert scales for psychosocial measurements. Int Electronic J Health Educ. 2005;8:178-192.

16. Vickers AJ. Comparison of an ordinal and a continuous outcome measure of muscle soreness. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1999;15:709-716.

17. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. A comparison of seven-point and visual analogue scales: data from a randomized trial. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:43-51.

18. Voutilainen A, Pitkaaho T, Kvist T, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. How to ask about patient satisfaction? The visual analogue scale is less vulnerable to confounding factors and ceiling effect than a symmetric Likert scale. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:946-957.

19. Brunelli C, Zecca E, Martini C, et al. Comparison of numerical and verbal rating scales to measure pain exacerbations in patients with chronic cancer pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:42.

20. Hageman MG, Briet JP, Bossen JK, et al. Do previsit expectations correlate with satisfaction of new patients presenting for evaluation with an orthopaedic surgical practice? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:716-721.

21. Keulen MHF, Teunis T, Vagner GA, et al. The effect of the content of patient-reported outcome measures on patient perceived empathy and satisfaction: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:1141.e1-e9.

22. Mellema JJ, O’Connor CM, Overbeek CL, et al. The effect of feedback regarding coping strategies and illness behavior on hand surgery patient satisfaction and communication: a randomized controlled trial. Hand. 2015;10:503-511.

23. Tyser AR, Gaffney CJ, Zhang C, Presson AP. The association of patient satisfaction with pain, anxiety, and self-reported physical function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1811-1818.

24. Vranceanu AM, Ring D. Factors associated with patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1504-1508.

25. Stirling P, Jenkins PJ, Clement ND, et al. The Net Promoter Scores with Friends and Family Test after four hand surgery procedures. J Hand Surg Eur. 2019;44:290-295.

26. Wilberforce M, Poll S, Langham H, et al. Measuring the patient experience in community mental health services for older people: A study of the Net Promoter Score using the Friends and Family Test in England. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:31-37.

1. Waters S, Edmondston SJ, Yates PJ, Gucciardi DF. Identification of factors influencing patient satisfaction with orthopaedic outpatient clinic consultation: A qualitative study. Man Ther. 2016;25:48-55.

2. Kortlever JTP, Ottenhoff JSE, Vagner GA, et al. Visit duration does not correlate with perceived physician empathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2019;101:296-301.

3. Edwards P, Roberts I, Clarke M, et al. Methods to influence response to postal questionnaires. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001(3):CD003227.

4. Salisbury C, Burgess A, Lattimer V, et al. Developing a standard short questionnaire for the assessment of patient satisfaction with out-of-hours primary care. Fam Pract. 2005;22:560-569.

5. Ross CK, Steward CA, Sinacore JM. A comparative study of seven measures of patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1995;33:392-406.

6. Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377-381.

7. Medicine USNLo. ClinicalTrials.gov. Accessed March 18, 2019.

8. Nicholas MK, McGuire BE, Asghari A. A 2-item short form of the Pain Self-efficacy Questionnaire: development and psychometric evaluation of PSEQ-2. J Pain. 2015;16:153-163.

9. Salkovskis PM, Rimes KA, Warwick H, Clark D. The Health Anxiety Inventory: development and validation of scales for the measurement of health anxiety and hypochondriasis. Psychol Med. 2002;32:843-853.

10. Schalet BD, Pilkonis PA, Yu L, et al. Clinical validity of PROMIS depression, anxiety, and anger across diverse clinical samples. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;73:119-127.

11. Ho AD, Yu CC. Descriptive statistics for modern test score distributions: skewness, kurtosis, discreteness, and ceiling effects. Educ Psychol Meas. 2015;75:365-388.

12. Kim HY. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38:52-54.

13. NICE Satmetrix. What is net promoter? https://www.netpromoter.com/know/. Accessed March 18, 2019.

14. Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34-42.

15. Hasson D, Arnetz BB. Validation and findings comparing VAS vs. Likert scales for psychosocial measurements. Int Electronic J Health Educ. 2005;8:178-192.

16. Vickers AJ. Comparison of an ordinal and a continuous outcome measure of muscle soreness. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1999;15:709-716.

17. Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. A comparison of seven-point and visual analogue scales: data from a randomized trial. Control Clin Trials. 1990;11:43-51.

18. Voutilainen A, Pitkaaho T, Kvist T, Vehvilainen-Julkunen K. How to ask about patient satisfaction? The visual analogue scale is less vulnerable to confounding factors and ceiling effect than a symmetric Likert scale. J Adv Nurs. 2016;72:946-957.

19. Brunelli C, Zecca E, Martini C, et al. Comparison of numerical and verbal rating scales to measure pain exacerbations in patients with chronic cancer pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:42.

20. Hageman MG, Briet JP, Bossen JK, et al. Do previsit expectations correlate with satisfaction of new patients presenting for evaluation with an orthopaedic surgical practice? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:716-721.

21. Keulen MHF, Teunis T, Vagner GA, et al. The effect of the content of patient-reported outcome measures on patient perceived empathy and satisfaction: a randomized controlled trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2018;43:1141.e1-e9.

22. Mellema JJ, O’Connor CM, Overbeek CL, et al. The effect of feedback regarding coping strategies and illness behavior on hand surgery patient satisfaction and communication: a randomized controlled trial. Hand. 2015;10:503-511.

23. Tyser AR, Gaffney CJ, Zhang C, Presson AP. The association of patient satisfaction with pain, anxiety, and self-reported physical function. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:1811-1818.

24. Vranceanu AM, Ring D. Factors associated with patient satisfaction. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36:1504-1508.

25. Stirling P, Jenkins PJ, Clement ND, et al. The Net Promoter Scores with Friends and Family Test after four hand surgery procedures. J Hand Surg Eur. 2019;44:290-295.

26. Wilberforce M, Poll S, Langham H, et al. Measuring the patient experience in community mental health services for older people: A study of the Net Promoter Score using the Friends and Family Test in England. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34:31-37.

Is Patient Satisfaction the Same Immediately After the First Visit Compared to Two Weeks Later?

From the Department of Surgery and Perioperative Care, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX (Dr. Kortlever, Ms. Haidar, Dr. Reichel, Dr. Driscoll, Dr. Ring, and Dr. Vagner) and University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, The Netherlands (Dr. Teunis).

Abstract

- Objective: Patient satisfaction is considered a quality measure. Satisfaction is typically measured directly after an in-person visit in research and 2 weeks later in practice surveys. We assessed if there was a difference in immediate and delayed measurement of satisfaction.

- Questions: (1) There is no difference in patient satisfaction (measured by Numerical Rating Scale [NRS]) and (2) perceived empathy (measured by the Jefferson Scale of Patient Perceptions of Physician Empathy [JSPPPE]) immediately after the initial visit compared to 2 weeks later. (3) Change in disability (measured by the Patient-Reported Outcome Measurement Information System Physical Function-Upper Extremity [PROMIS PF-UE]) is not independently associated with change in satisfaction and (4) empathy after the initial visit compared to 2 weeks later.

- Methods: 150 new patients completed a survey of demographics, satisfaction with the surgeon, rating of the surgeon’s empathy, and upper extremity specific limitations. The satisfaction, empathy, and limitation questionnaires were repeated 2 weeks later.

- Results: We found a slight but significant decrease in satisfaction 2 weeks after the in-person visit (–0.41, P = 0.001). There was no significant change in perceived empathy (–0.71, P = 0.19). Change in limitations did not account for a change in satisfaction (P = 0.79) or perceived empathy (P = 0.93).

- Conclusion: Satisfaction and perceived empathy are relatively stable constructs that can be measured immediately after the visit.

Keywords: satisfaction, empathy, change, upper extremity, disability.

Patient satisfaction is increasingly being used as a performance measure to evaluate quality of care.1-8 Patient satisfaction correlates with adherence with recommended treatment.1,6,8-10 Satisfaction measured on an 11-point ordinal scale immediately after the visit correlates strongly with the perception of clinician empathy.2,3 Indeed, some satisfaction questionnaires such as the Medical Interview Satisfaction Scale (MISS)11,12 have questions very similar to empathy questionnaires. It may be that satisfaction is a construct similar to feeling that your doctor listened and cared about you as an individual (perceived physician empathy).

Higher ratings of satisfaction also seem to be related to a physician’s communication style.1,4,7-10 One study of 13 fertility doctors found that training in effective communication strategies led to improved patient satisfaction.7 A qualitative study of 36 patients, health professionals, and clinical support staff in an orthopaedic outpatient setting held interviews and focus group sessions to identify themes influencing patient satisfaction.4 Communication and expectation were among the 7 themes identified. We have noticed a high ceiling effect (maximum scores) with measures of patient satisfaction and perceived empathy.2,3 Another study also noted a high ceiling effect when using an ordinal scale.5 It may be that people with a positive feeling shortly after a health care encounter give top ratings out of politeness or gratefulness. It is also possible they will feel differently a few weeks after they leave the office. Furthermore, ratings of satisfaction gathered by a practice or health care system for practice assessment/improvement are often obtained several days to weeks after the visit, while research often obtains satisfaction ratings immediately after the visit for practical reasons. There may be differences between immediate and delayed measurement of satisfaction beyond the mentioned social norms.

Therefore, this study tested the primary null hypothesis that there is no difference in patient satisfaction (measured by Numerical Rating Scale [NRS]) immediately after the initial visit compared to 2 weeks later. Additionally, we assessed the difference in perceived empathy immediately after the initial visit compared to 2 weeks later, and whether change in disability was independently associated with change in satisfaction and empathy after the initial visit compared to 2 weeks later.

Methods

Study Design

After Institutional Review Board approval of this prospective, longitudinal, observational cohort study, we prospectively enrolled 150 adult patients between November 29, 2017 and January 10, 2018. Patients were seen at 5 orthopaedic clinics in a large urban area. We included all new English-speaking patients aged 18 to 89 years who were visiting 1 of 6 participating orthopaedic surgeons for any upper extremity problem and who were able to provide informed consent. We excluded follow-up visits and patients who were unable to speak and understand English. Four research assistants who were not involved with patient treatment described the study to patients before or after the visit with the surgeon. We were granted a waiver of written informed consent; patients indicated their consent by completing the surveys.

Patients could choose either phone or email as their preferred mode of contact for follow-up in this study. For patients who selected email as the preferred mode of contact, the follow-up survey was sent automatically 2 weeks after completion date, and a maximum of 3 reminder emails with 2-day time intervals between them were sent to those who did not respond to the initial invitation. For patients who selected phone as the preferred mode of contact, the follow-up survey was done by an English-speaking research assistant who was not involved with patient treatment. When a response was not obtained on the initial phone call, 3 additional phone calls were made (1 later that same day and 2 the next day). One patient declined participation because he was not interested in the study and had no time after his visit.

Measurements

Patients were asked to complete a set of questionnaires at the end of their visit:

1. A demographic questionnaire consisting of preferred mode of contact for follow-up (phone or email), age, sex, race/ethnicity, marital status, education status, work status, insurance status, and type of visit (first visit or second opinion);

2. An 11-point ordinal measure of satisfaction with the surgeon, with scores ranging from 0 (Worst Surgeon Possible) to 10 (Best Surgeon Possible);

3. The patient’s rating of the surgeon’s empathy, measured by the Jefferson Scale of Patient Perceptions of Physician Empathy (JSPPPE).13 The JSPPPE is a 5-item questionnaire, measured on a 7-point Likert scale, with scores ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), that assesses agreement with statements about the physician. The total score is the sum of all item scores (5-35), with higher scores representing a higher degree of perceived physician empathy.

4. Upper extremity disability, measured by the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Physical Function-Upper Extremity (PROMIS PF-UE) Computer Adaptive Test (CAT).14-16 This is a measure of physical limitations in the upper extremity. It can be completed with as few as 4 questions while still achieving high precision in scoring and thereby decreasing survey burden. PROMIS presents a continuous T-score with a mean of 50 and standard deviation (SD) of 10, with higher scores reflecting better physical function compared to the average of the US general population.15

After completing the initial questionnaire, the research assistant filled out the office and surgeon name and asked the surgeon to complete the diagnosis. All questionnaires were administered on an encrypted tablet via the secure, HIPAA-compliant electronic platform REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a web-based application for building and managing online surveys and databases.17 The follow-up survey was sent automatically or was done by phone call as previously described. The follow-up survey consisted of (1) the 11-point ordinal measure of satisfaction with the surgeon, (2) the JSPPPE for perceived empathy, and (3) the PROMIS PF-UE for physical limitations in the upper extremity.

Analysis

Continuous variables are presented as mean ± SD and discrete data as proportions. We used Student’s t-tests to assess baseline differences between continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for discrete variables. To assess differences in satisfaction and perceived empathy after 2 weeks, we used Student’s paired t-tests. We created 2 multilevel multivariable linear regression models to assess factors associated with (1) change in satisfaction with the surgeon and (2) change in perceived physician empathy. These models account for correlation of patients treated by the same surgeon. We selected variables to be included in the final models by running multilevel models with only 1 independent variable of interest (Appendix 1). Variables with P < 0.10 were included in our final models. We also included change in PROMIS PF-UE in both models because this was our variable of interest. We considered P < 0.05 significant.

We performed a power analysis for the difference in patient satisfaction immediately after the first visit compared to 2 weeks later. Based on our pilot data where we found an initial mean satisfaction score of 9.4 and mean satisfaction score after 2 weeks of 9.1 (SD of difference 1.0), a priori power analysis showed that we needed a minimum sample size of 90 patients to detect a difference with power set at 0.80 and alpha set at 0.05. In order to account for loss to follow-up as previously noted,18 we enrolled 67% more patients (total of 150).

Results

Respondent Characteristics

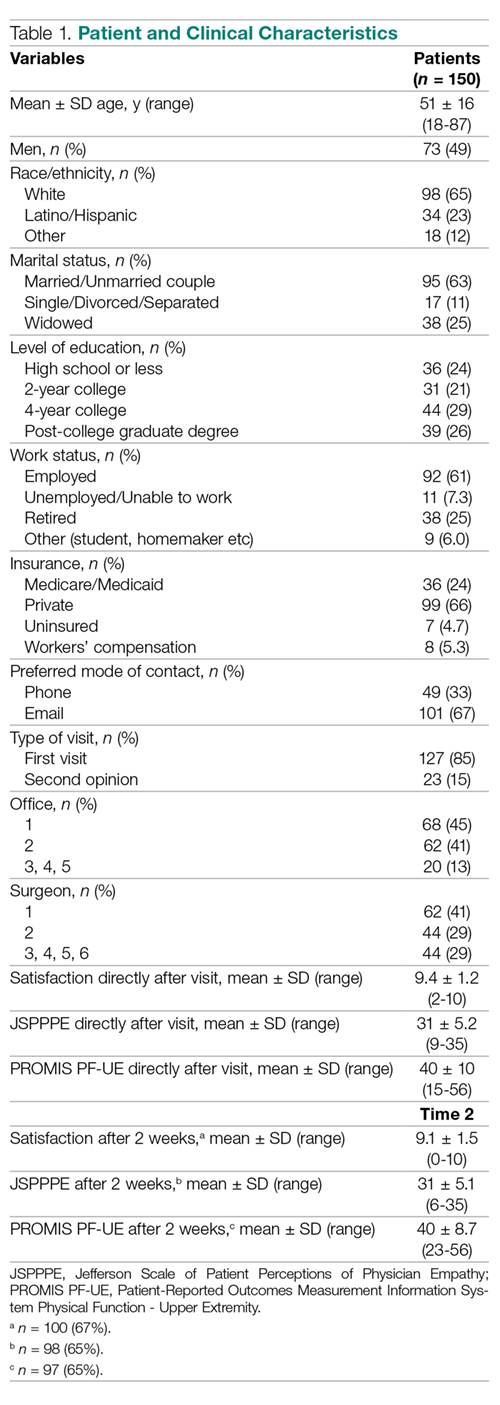

None of the 150 patients were excluded from the analysis. The study patients’ mean age was 51 ± 16 years (range, 18-87 years), and 73 (49%) were men (Table 1). Mean scores directly after the visit were 9.4 ± 1.2 (range, 2-10) for satisfaction with the surgeon, 31 ± 5.2 (range, 9-35) for perceived physician empathy, and 40 ± 10 (range 15-56) for upper extremity disability. Most patients (n = 130, 87%) were seen in 2 of 5 offices, and 106 (71%) were seen by 2 out of 6 participating surgeons.

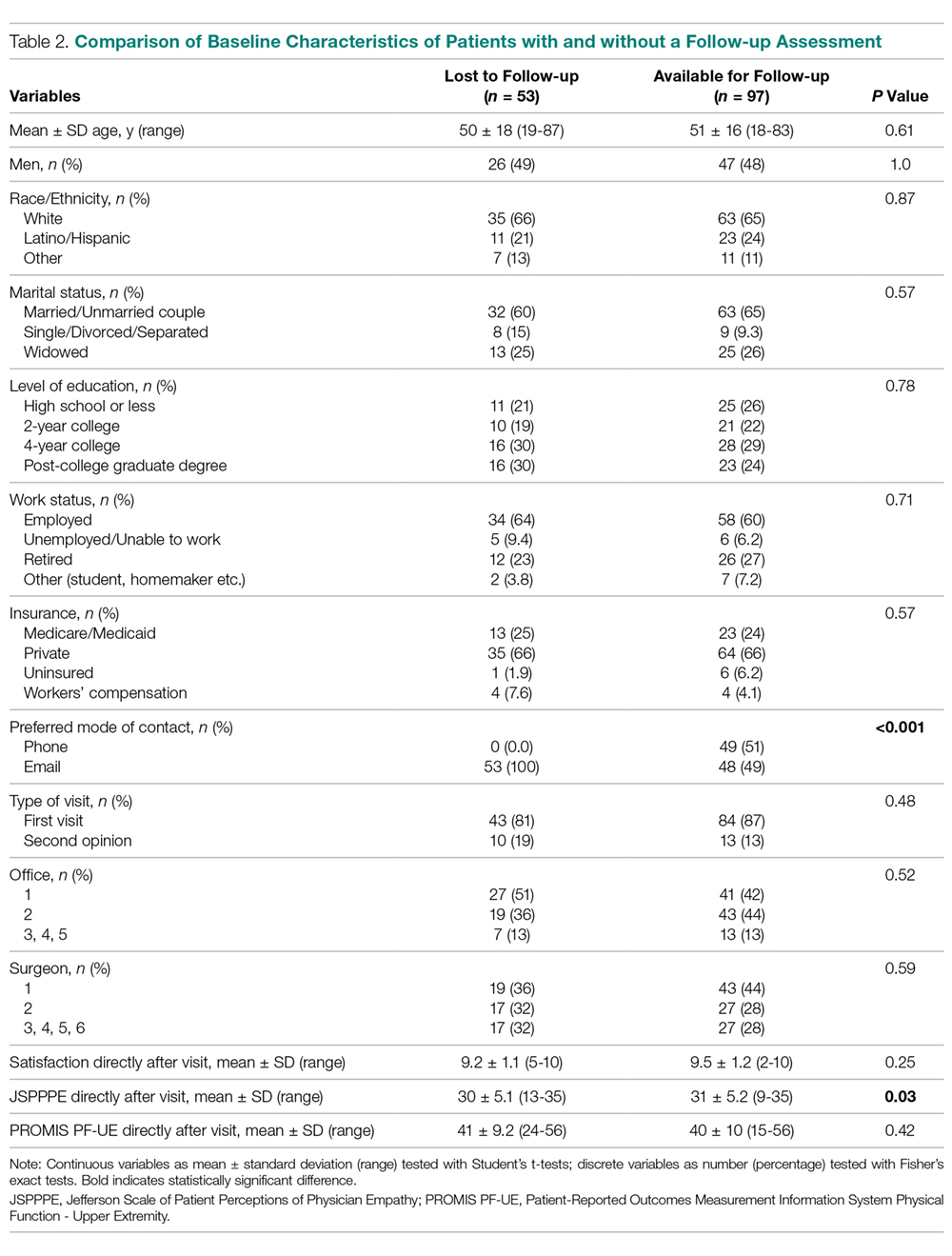

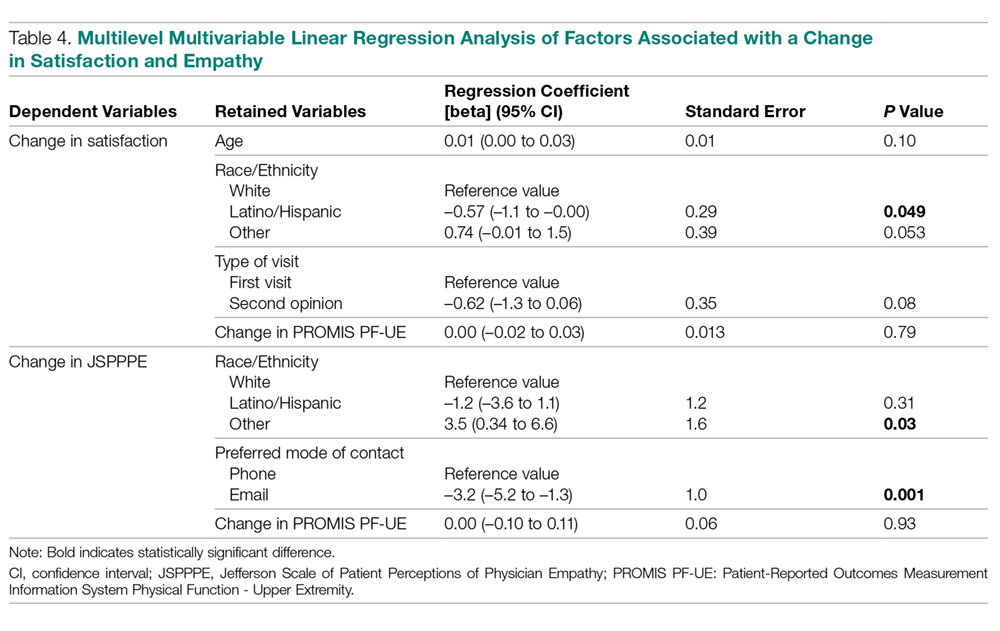

Ninety-seven (65%) patients completed their follow-up assessment 2 weeks after their initial visit, 49 (51%) by phone and 48 (49%) by email. This is a slightly better rate than the 36% rate reported in previous research.18 After 2 weeks, the mean score for satisfaction with the surgeon was 9.1 ± 1.5 (range, 0-10), the mean perceived empathy score was 31 ± 5.1 (range, 6-35), and the mean upper extremity disability score was 40 ± 8.7 (range, 23-56). Responders did not differ from nonresponders based on demographic data (Table 2). However, nonresponders had lower perceived empathy scores directly after their visit (P = 0.03) and none had initially chosen phone as their preferred mode of contact for follow-up (P < 0.001). A list of all diagnoses with frequencies the surgeons stated is listed in Appendix 2.

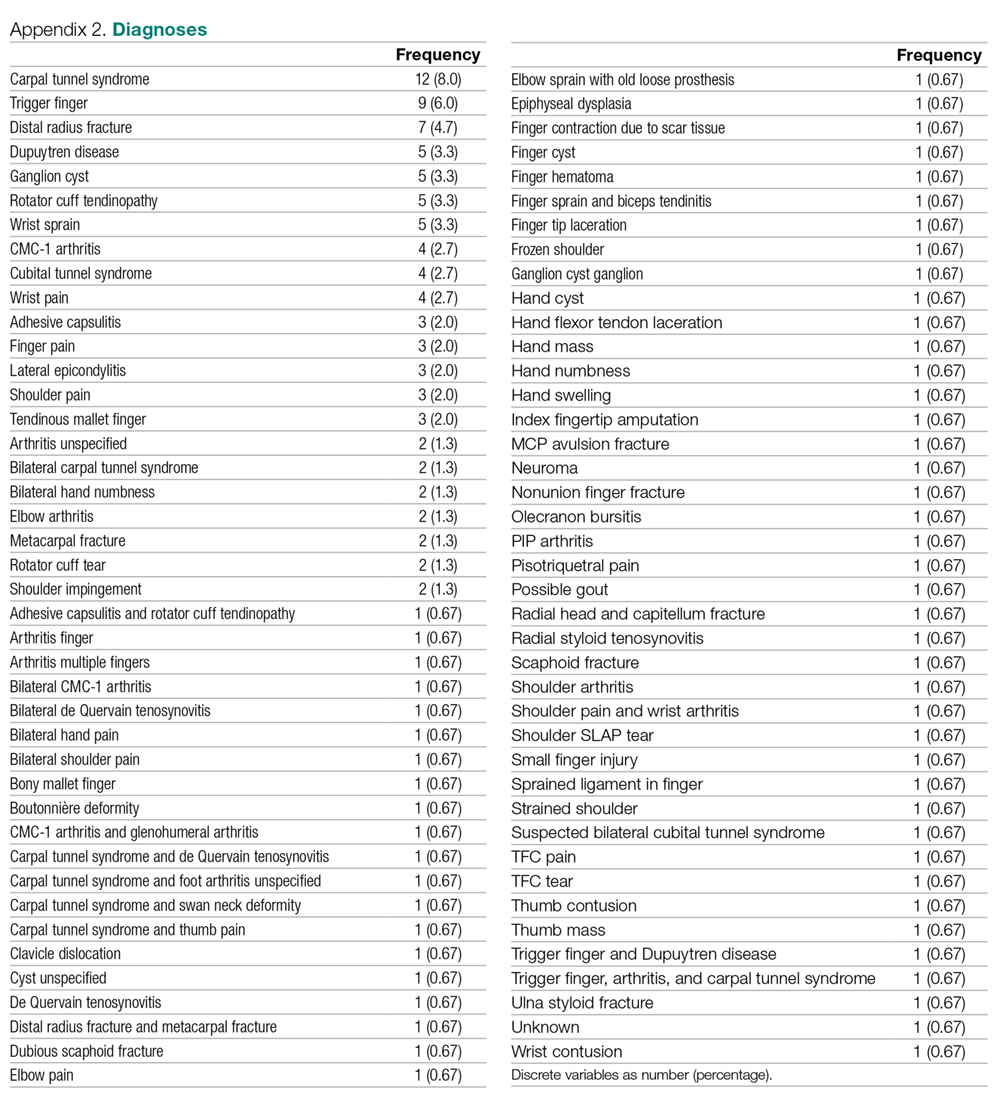

Difference in Satisfaction with the Surgeon

Satisfaction with the surgeon 2 weeks after the in-person visit was slightly, but significantly, lower on bivariate analysis compared to satisfaction with the surgeon immediately after the initial visit (–0.41 ± 1.2, P = 0.001; Table 3).

Difference in Perceived Physician Empathy

Perceived physician empathy 2 weeks after the in-person visit was not significantly lower on bivariate analysis compared to perceived physician empathy immediately after the initial visit (–0.71 ± 5.3, P = 0.19; Table 3).

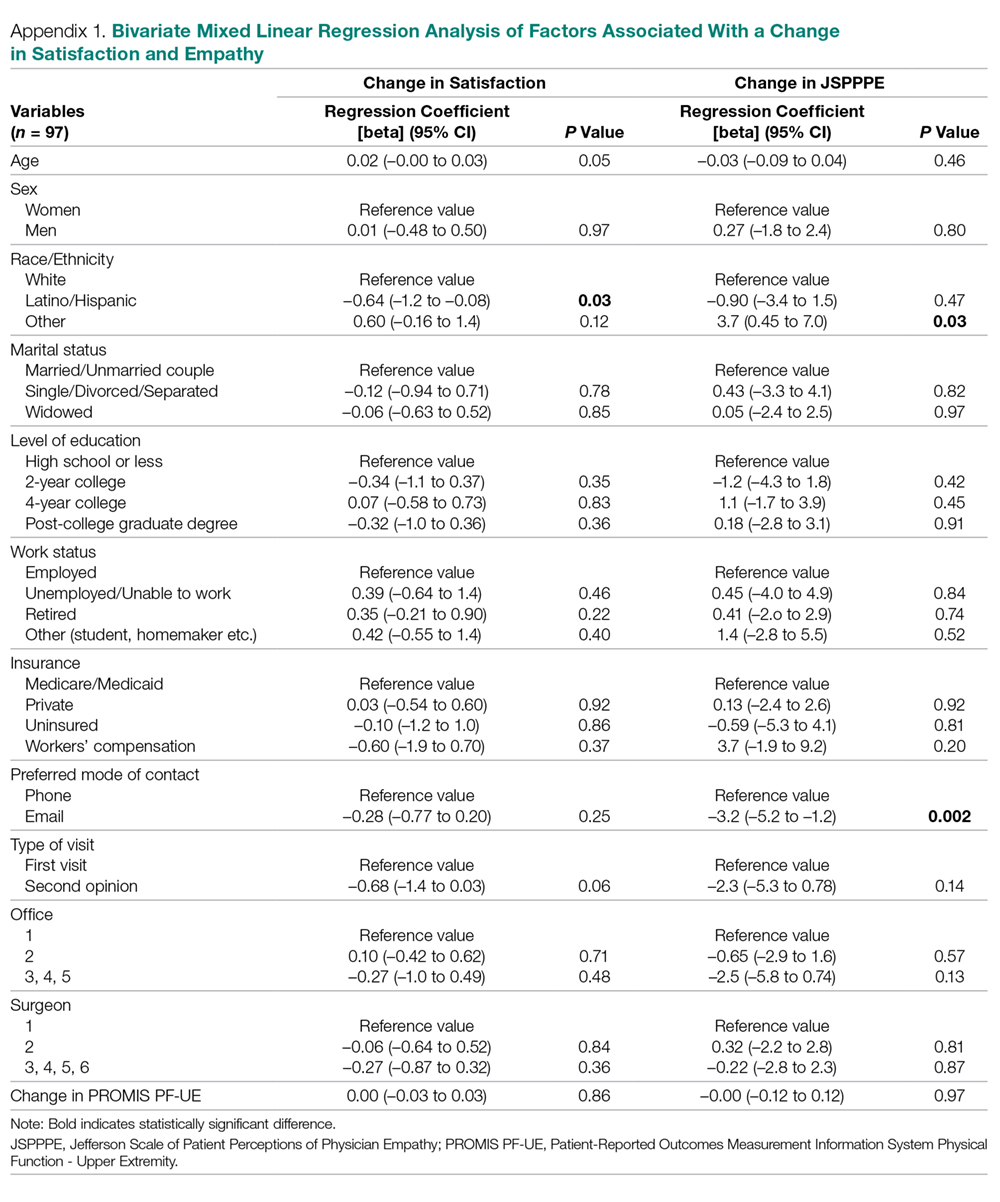

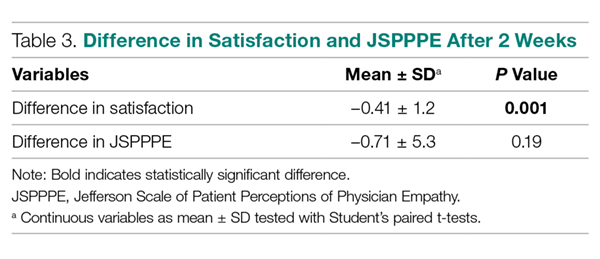

Factors Associated with Change in Satisfaction with the Surgeon

Accounting for potential interaction of variables using multilevel multivariable analysis, change in disability of the upper extremity was not associated with change in satisfaction with the surgeon (regression coefficient [beta], 0.00 [95% confidence interval {CI}, –0.02 to 0.03]; standard error [SE], 0.01; P = 0.79 [Table 4]). Being Latino was independently associated with less change in satisfaction with the surgeon (beta coefficient, –0.57 [95% CI, –1.1 to 0.00]; SE, 0.29; P = 0.049).

Factors Associated with Change in Perceived Physician Empathy

Accounting for potential interaction of variables using multilevel multivariable analysis, change in disability of the upper extremity was not associated with change in perceived physician empathy (beta coefficient = 0.00 [95% CI, –0.10 to 0.11]; SE, 0.06; P = 0.93 [Table 4]). Race/ethnicity other than white or Latino was independently associated with more change in perceived physician empathy (beta coefficient, 3.5 [95% CI, 0.34 to 6.6]; SE, 1.6; P = 0.030), and preferring email as mode of contact for follow-up was independently associated with less change in perceived physician empathy (beta coefficient, –3.2 [95% CI, –5.2 to –1.3]; SE, 1.0; P = 0.001).

Discussion

Patient satisfaction is considered a quality measure1-8 and is typically measured directly after an in-person visit. This study tested differences in patient satisfaction and perceived empathy immediately after the initial visit compared to 2 weeks later. In addition, we assessed whether change in disability was independently associated with change in satisfaction and empathy after the initial visit compared to 2 weeks later.

We acknowledge some study limitations. First, we only measured satisfaction based on 1 visit rather than multiple visits over time. It might be that satisfaction ratings differ when the physician-patient relationship is more established. However, we found overall high satisfaction ratings and a well-established relationship might not add to this finding. Second, surgeons were aware of the study and its purpose, which might have resulted in subconsciously altering the behavior to improve satisfaction. The effect of people acting differently as a result of being observed is called the Hawthorne effect.19 Third, we only used 1 simple ordinal measure to assess patient satisfaction with the surgeon. There is a wide variety of satisfaction measures,20 though the focus of this study was not to test the best possible satisfaction measure but to assess changes in satisfaction over time and its predictors. The simple 11-point ordinal satisfaction measure has proved reliable.6 Fourth, 35% of patients did not make a second rating. This is not unusual for phone or email studies. Our response rate was relatively high compared to other studies in our field,18 perhaps because the time to the second assessment was only 2 weeks and all people were available for follow-up by phone. Fifth, we analyzed 4 surgeons as 1 group and 3 offices as 1 group since we did not enroll enough patients per surgeon and office for individual analysis. However, multilevel linear analysis takes surgeon specific factors into account within that group.

The finding that satisfaction with the surgeon after 2 weeks was significantly lower on bivariate analysis compared to immediately after the initial visit is different from a study that found small increases in satisfaction after 2 weeks and 3 months,1 but comparable to another study in our field.21 Although significant, we believe the decrease in satisfaction is probably not clinically relevant. It might also be that satisfaction at follow-up is lower than measured, but that the least satisfied people did not respond on the follow-up survey.

We found no significant change in perceived empathy after 2 weeks. Since empathy is a strong driver of satisfaction,2,4-7 we did not expect to find differing results for empathy and for satisfaction over time. Both satisfaction and empathy seem to be relatively durable measures with current measurement tools.

The finding that change in disability was neither independently associated with change in satisfaction nor change in empathy is consistent with prior research.2,3,21 We cannot adequately study the impact of changes since we did not find an important change in either satisfaction or empathy over time. Jackson et al found higher satisfaction ratings over time in patients who had an increase in physical function and a decrease in symptoms.1 They also found that met expectations was associated with higher satisfaction immediately after the visit, after 2 weeks, and after 3 months.1 We feel that met expectations and fewer symptoms and limitations are likely highly co-linear with satisfaction. We therefore may not be able to learn much about one from the others.

The slight change we found in satisfaction with the surgeon among Latino patients was significantly less than the change among white patients. This suggests Latino patients might have a more stable opinion over time (a cultural phenomenon), or it might be spurious given the small number of Latino patients included in the study. The same can be said for the finding that race/ethnicity other than white or Latino was independently associated with greater change in empathy. Providing email as the preferred mode of contact was found to be independently associated with less change in perceived empathy compared to follow-up by phone. We had a 100% success rate for our follow-ups by phone. Our findings suggest that patients might more easily switch ratings on an 11-point ordinal scale than on a 5-item Likert scale. However, both measures are often rated at the ceiling of the scale.2,21

Conclusion

Satisfaction and perceived empathy are relatively stable constructs, are not clearly associated with other factors, and are strongly correlated with one another. This study supports the research practice of measuring satisfaction immediately after the visit, which is more convenient for both participant and researcher and avoids the loss of more than one third of the patients, and those with a worse experience in particular. To improve the utility and interpretation of patient-reported experience measures such as these, we might direct our efforts to developing scales with less ceiling effect.

Corresponding author: David Ring, MD, PhD, Dell Medical School, The University of Texas at Austin, Health Discovery Building HDB 6.706, 1701 Trinity St., Austin, TX 78705; david.ring@austin.utexas.edu.