User login

More Patients Pick Acupuncture

In 2004, 370 of 1,394 reporting hospitals offered some complementary alternative medicine (CAM) services in the U.S. Of the 370 hospitals reporting CAM services, 11.5% (42 hospitals) reported inpatient acupuncture services.1

This threefold increase since 1998 demonstrates the growing use of and demand for acupuncture services in hospitals. This trend is driven by patient demand and clinical effectiveness. Acupuncture is a safe treatment modality hospital physicians should be familiar because it can benefit patients in the inpatient setting.

Origins of Acupuncture

The first use of acupuncture is not known. The earliest medical textbook on acupuncture was The Medical Classic of the Yellow Emperor, written about 100 B.C. The first translation of this text into English was in 1949.2

The book outlined the theory of a system of six sets of symmetrical channels on the body’s surface, which it called meridians; along these, it posited an intricate network of points.3 Needling the points was supposed to manipulate or release the flow of energy or life force—Qi—to the internal organs, thereby alleviating symptoms. Heating acupuncture points with burning herbs—moxibustion—was also purported to relieve pain.

Acupuncture in the U.S.

The first documented use of acupuncture in the United States occurred in the 19th century. In 1826, Bache used it to treat lumbago.4 During that same era, William Mosley used acupuncture to treat patients with lumbago and sciatica.5

In 1971, a first-person account of the use of acupuncture by New York Times reporter James Reston excited great interest in the technique. Reston was introduced to the procedure to relieve pain after an emergency appendectomy during a trip to China with Henry A. Kissinger.6

Since then, there has been a steady increase in the use of acupuncture by physicians. The American Academy of Medical Acupuncture, the only physician-based acupuncture society in North America, was formed in 1987; in 1992, the Office of Alternative Medicine was created within the NIH. In November 1997, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) removed the experimental designation for acupuncture needles and approved their use by licensed practitioners. By 1993, the FDA had a record of more than 9,000 licensed acupuncturists, estimated to be providing more than 10 million treatments annually at a cost in excess of $500 million.7

Acupuncture is part of the quasi-medical area of complementary and alternative medicine, whose practitioners field more visits annually than all primary-care physicians in this country combined.8 Most acupuncturists practice the Chinese technique.9

Licensing requirements vary by state.10 As acupuncture has gained popularity and respect, and as its benefit for various medical conditions has been proved in high-quality studies, many well-established medical institutions and universities have begun to integrate it with more traditional Western medical treatments.

Acupuncture Theories

The early Chinese theories about how best to perform acupuncture were varied and sometimes conflicting.11 Early treatments using heat, bloodletting, and crude stone implementation evolved over centuries into the intricate practice known today.

Western scientists first became seriously interested in researching the effects of acupuncture in the 1970s. Many of the early studies were poorly designed, and the results were often not reproducible. They were not sufficiently randomized or blinded, and placebo controls were unreliable or nonexistent. To date, no single theory has been put forth that can explain all the phenomena associated with acupuncture treatment.

In 1991, the World Health Organization proposed a standard nomenclature for the 400 acupuncture points and the 20 meridians connecting those points.12 The precise anatomical locations of these areas have not yet been identified definitively. They have a low electrical resistance compared with surrounding tissue. Theories attempting to correlate the acupuncture points with neurovascular bundles have been postulated but remain unproved. The existence of acupuncture points has been verified with galvanometer scanning. These devices measure electrical conductance and emit an audio signal when an area of low resistance is encountered. New points have been added and the location of some of the original ones redefined by this technique.

In some of the earliest research conducted, French acupuncturists Niboyet and Grall mapped many of the points.13,14 Darras attempted to prove the existence of the meridians by tracing the flow of the radionuclide technetium TC 99m sulfur colloid after it was injected into them.15 No published reports in the English-language medical literature have reliably confirmed scientific studies documenting either the existence or location of the meridians.16

The neurohumoral theory postulates that the analgesic effects of acupuncture are related to the release of neurotransmitters such as endogenous opioids. In addition, acupuncture appears to inhibit the transmission of C-fiber pain at the level of the spinal cord.17,18 Other physiological phenomena have also been observed with acupuncture by needling. They include vasodilation, increased serum cortisol, variations in serum glucose and cholesterol levels, increased white blood cell counts, and acid suppression.5 Their significance continues to be questioned.

Evidence-Based Approach

Many studies of acupuncture have methodological flaws. The biggest problem as yet unresolved is an appropriate placebo control.19 Sham acupuncture, which involves needling non-acupuncture points, is frequently the control of choice but has serious limitations.

In 1997, the landmark NIH consensus statement was probably the most important presentation of evidence supporting the efficacy of acupuncture.20 Conclusions made about the effectiveness of acupuncture were based on evidence from reliable studies. Many promising results emerged. Specific indications for use of acupuncture were identified on the basis of published reports of its effectiveness. Efficacy in treating dental pain and post-operative and chemotherapy-induced nausea were demonstrated. Research suggested its usefulness as an adjunct or alternative treatment for lower-back pain, osteoarthritis, addiction, and stroke rehabilitation. The panel also concluded that further research would likely uncover additional uses for acupuncture.

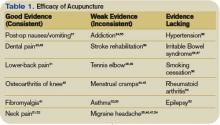

From the standpoint of acupuncture’s effectiveness, it can clearly benefit specific patient groups. It is most commonly used as a treatment for back pain.21 Since the NIH conference, further research has confirmed its effectiveness in treating a variety of medical conditions. (See Table 1, above)

Much of the ongoing research on acupuncture has focused on the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, specifically on the areas that light up, or show brain activity, during activities or a state of pain.22-24 Acupuncture has been found to reduce the intensity of signals in such areas. The mechanism for the analgesic effects of acupuncture may be the result of reduced blood flow to the brain.24 Several studies have identified specific areas of the brain affected by pressure on various acupuncture points.25

Practical Aspects

Acupuncture treatments are extremely time efficient and require minimal equipment. They can be administered with the patient in the recumbent position or sitting upright. For initial sessions, I prefer the former, especially for younger males, who are more prone to vasovagal reactions. Any of several different methods of acupuncture can be used to stimulate points. In addition to needling, acupuncture can be conducted by electro-acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping, scraping, tapping, acupressure, or laser.

Most inpatient referrals are for pain management. Other common indications include post-operative or chemotherapy-induced nausea (emesis), anxiety, and prevention of withdrawal symptoms from narcotics.

Acupuncture Safety

Overall, acupuncture is a safe treatment method. Many large studies have confirmed that most types of acupuncture have a low rate of complications and that most of these complications are transient and minor in nature.28,29 They are incident-reporting studies, however, and have the limitations inherent in these studies. Nausea, dizziness, bruising, and needle pain are some of the most commonly reported. The rare but serious adverse events, such as pneumothorax, usually occur as a result of the practitioner’s poor training or technique.30

Future of Acupuncture

Public acceptance of, and demand for, acupuncture for pain relief is increasing. Additional clinical studies are needed, however, to expand the types of conditions for which acupuncture may be useful. It is essential to maintain a constant focus on safe practice, which would be aided by the establishment of a standardized accreditation and training system. Hospitals need to establish uniform credentialing guidelines similar to those for other procedures that require evidence of medical competence and safety.31

In February 2005, the Federal Acupuncture Coverage Act was introduced to Congress. If enacted, the measure would allow acupuncture to be covered under Part B for Medicare recipients.

The trend toward an integrated approach to patient therapy in large academic medical institutions is encouraging. The incorporation of the teaching of acupuncture within the current medical school curricula would no doubt complement this approach. TH

Joseph C. Charles, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of medicine and division education coordinator for the Department of Hospital Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic Hospital Arizona.

References

- Ananth, S. Health Forum 2005 Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals, July 19, 2006. News release, American Hospital Association.

- Veith I (trans). The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. Baltimore; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins: 1949.

- Ming Z (trans). The Medical Classic of the Yellow Emperor. Beijing; Foreign Languages Press: 2001.

- Cassedy JH. Early uses of acupuncture in the United States, with an addendum (1826) by Franklin Bache, M.D. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1974 Sep;50(8):892-906.

- Osler W. The Principles and Practice of Medicine. New York: D. Appleton and Company; 1892.

- Reston J. Now, let me tell you about my appendectomy in Peking. New York Times. July 26, 1971.

- Mitchell BB. Educational and licensing requirements for acupuncturists. J Altern Complement Med. 1996 spring;2(1):33-35.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993 Jan 28;328(4):246-252.

- Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Eisenberg DM, et al. The practice of acupuncture: who are the providers and what do they do? Ann Fam Med. 2005 Mar-Apr;3(2):151-158.

- Leake R, Broderick JE. Current licensure for acupuncture in the United States. Altern Ther Health Med. 1999 Jul;5(4):94-96.

- Shang C. The past, present, and future of meridian system research. In: Stux G, Hammerschlag R, eds. Clinical Acupuncture: Scientific Basis. Berlin: Springer; 2001:69-82.

- WHO Scientific Group on International Acupuncture Nomenclature. A proposed standard international acupuncture nomenclature: report of a WHO Scientific Group. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991.

- Niboyet JEH. Nouvelles constatations sur les proprietes electriques des points chinois. Bull Soc Acupunct. 1938;4:30-79.

- Helms JM. Acupuncture Energetics: A Clinical Approach for Physicians. Berkeley, Calif.: Medical Acupuncture Publishers; 1995:23-24.

- De Vernejoul P, Albarede P, Darras JC. Study of acupuncture meridians using radioactive tracers [in French]. Bull Acad Natl Med. 1985 Oct;169(7):1071-1075.

- Simon J, Guiraud G, Esquerre JP, et al. Acupuncture meridians demythified. Contribution of radiotracer methodology [in French]. Presse Med. 1988 Jul 2;17(26):1341-1344.

- Pomeranz B, Chiu D. Naloxone blockade of acupuncture analgesia: endorphin implicated. Life Sci. 1976 Dec 1;19(11):1757-1762.

- Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:374-383.

- Vincent C, Lewith G. Placebo controls for acupuncture studies. J R Soc Med. 1995 Apr;88(4):199-202.

- Acupuncture. NIH Consensus Statement 1997; 15:1-34

- Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, et al. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:651-663.

- Tank DW, Oqawa S, Uqurbil K. Mapping the brain with MRI. Curr Biol. 1992;525-528.

- Salvatore S. Brain imaging suggests acupuncture works, study says. [monograph on the Internet]. CNN.com with WebMD.com. Dec. 1, 1999. Available at http://archives.cnn.com/1999/HEALTH/alternative/12/01/brain.acupuncture/index.html. Last accessed April 14, 2007.

- Fang JL, Krings T, Weidemann J, et al. Functional MRI in healthy subjects during acupuncture: different effects of needle rotation in real and false acupoints. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:359-362.

- Cho ZH, Chung SC, Jones JP, et al. New findings of the correlation between acupoints and corresponding brain cortices using functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998 Mar;95(5):2670-2673. Retraction in Cho ZH, Chung SC, Lee HJ, Wong EK, Min BI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006 Jul 5;103(27):10527.

- Ulett GA, Han S, Han JS. Electroacupuncture: mechanisms and clinical application. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:129-138.

- Gam AN, Thorsen H, Lonnberg F. The effect of low-level laser therapy on musculoskeletal pain: a meta-analysis. Pain. 1993;52:63-66.

- White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A, et al. Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32, 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ. 2001 Sep 1;323(7311):485-486.

- MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, et al. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ. 2001;323:486-487. Comment in BMJ. 2001 Sep 1;323(7311):467-8. BMJ. 2002 Jan 19;324(7330):170-1.

- Chauffe RJ, Duskin AL. Pneumothorax secondary to acupuncture therapy. South Med J. 2006;99:1297-1299.

- Cohen MH, Hrbek A, Davis RB, et al. Emerging credentialing practices, malpractice liability policies, and guidelines governing complementary and alternative medical practices and dietary supplement recommendations: a descriptive study of 19 integrative health care centers in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:289-295.

- Linde K, Jobst K, Panton J. Acupuncture for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000008.

- Kleijnen J, Ter Riet G, Knipschild P. Acupuncture and asthma: a review of controlled trials. Thorax. 1991;46:799-802.

- Ter Reit G, Kleijnen J, Knipschild P. A meta-analysis of studies into the effect of acupuncture on addiction. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:379-382.

- Vincent CA. A controlled trial of the treatment of migraine by acupuncture. Clin J Pain. 1989;5:305-312.

- White AR, Rampes H, Ernst E. Acupuncture for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000009.

- Mann E. Using acupuncture and acupressure to treat postoperative emesis. Prof Nurse. 1999; 14:691-694.

- Macklin EA, Wayne PM, Kalish LA, et al. Stop hypertension with the acupuncture research program (SHARP): results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Hypertension. 2006;48:838-845.

- Lee JD, Chon JS, Jeong HK, et al. The cerebrovascular response to traditional acupuncture after stroke. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:780-784.

- Scharf HP, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, et al. Acupuncture and knee osteoarthritis: a three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:12-20.

- Martin DP, Sletten CD, Williams BA, et al. Improvement in fibromyalgia symptoms with acupuncture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:749-757.

- Lu DP, Lu GP. Anatomical relevance of some acupuncture points in the head and neck region that dictate medical or dental application depending on depth of needle insertion. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2003;28(3-4):145-156.

- Ernst E, Pittler MH. The effectiveness of acupuncture in treating acute dental pain: a systemic review. Br Dent J. 1998;184:443-447.

- Chen HM, Chen CH. Effects of acupressure at the Sanyinjiao point on primary dysmenorrhoea. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(4):380-387.

- Pouresmail Z, Ibrahimzadeh R. Effects of acupressure and ibuprofen on the severity of primary dysmenorrhea. J Tradit Chin Med. 2002 Sep; 22(3):205-210.

- Linde K, Streng A, Jurgens S, et al. Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005 May 4;293(17):2118-2125.

- Allais G, De Lorenzo C, Quirico PE, et al. Acupuncture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine without aura: a comparison with flunarizine. Headache. 2002 Oct;42(9):855-861.

- Green S, Buchbinder R, Barnsley L, et al. Acupuncture for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD003527. Review.

- Trinh KV, Phillips SD. Acupuncture for the alleviation of lateral epicondyle pain: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004:43:1085-1090.

- David J, Townsend S, Sathanathan R, et al. The effect of acupuncture on patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999 Sep;38(9):864-869. Comment in Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000 Oct;39(10):1153-1154.

- Irnich D, Behrens N, Molzen H, et al. Randomised trial of acupuncture compared with conventional massage and “sham” laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain. BMJ. 2001 Jun 30;322(7302):1574-1578. Comment in BMJ. 2001 Dec 1;323(7324):1306-7.

- White P, Lewith G, Prescott P, et al. Acupuncture versus placebo for the treatment of chronic mechanical neck pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Dec 21;141(12):911-919. Comment in Ann Intern Med. 2004 Dec 21;141(12):957-958. Ann Intern Med. 2005 May 17;142(10):873; author reply 873-874.

- Cheuk DK, Wong V. Acupuncture for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD005062.

- Griggs C, Jensen J. Effectiveness of acupuncture for migraine: critical literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006 May;54(4):491-501.

- Kim YH, Schiff E, Waalen J, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for treating cocaine addiction: a review paper. J Addict Dis. 2005;24(4):115-132.

- Forbes A, Jackson S, Walter C, et al. Acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome: a blinded placebo-controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 Jul 14;11(26):4040-4044.

- Schneider A, Enck P, Streitberger K, et al. Acupuncture treatment in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:649-654.

In 2004, 370 of 1,394 reporting hospitals offered some complementary alternative medicine (CAM) services in the U.S. Of the 370 hospitals reporting CAM services, 11.5% (42 hospitals) reported inpatient acupuncture services.1

This threefold increase since 1998 demonstrates the growing use of and demand for acupuncture services in hospitals. This trend is driven by patient demand and clinical effectiveness. Acupuncture is a safe treatment modality hospital physicians should be familiar because it can benefit patients in the inpatient setting.

Origins of Acupuncture

The first use of acupuncture is not known. The earliest medical textbook on acupuncture was The Medical Classic of the Yellow Emperor, written about 100 B.C. The first translation of this text into English was in 1949.2

The book outlined the theory of a system of six sets of symmetrical channels on the body’s surface, which it called meridians; along these, it posited an intricate network of points.3 Needling the points was supposed to manipulate or release the flow of energy or life force—Qi—to the internal organs, thereby alleviating symptoms. Heating acupuncture points with burning herbs—moxibustion—was also purported to relieve pain.

Acupuncture in the U.S.

The first documented use of acupuncture in the United States occurred in the 19th century. In 1826, Bache used it to treat lumbago.4 During that same era, William Mosley used acupuncture to treat patients with lumbago and sciatica.5

In 1971, a first-person account of the use of acupuncture by New York Times reporter James Reston excited great interest in the technique. Reston was introduced to the procedure to relieve pain after an emergency appendectomy during a trip to China with Henry A. Kissinger.6

Since then, there has been a steady increase in the use of acupuncture by physicians. The American Academy of Medical Acupuncture, the only physician-based acupuncture society in North America, was formed in 1987; in 1992, the Office of Alternative Medicine was created within the NIH. In November 1997, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) removed the experimental designation for acupuncture needles and approved their use by licensed practitioners. By 1993, the FDA had a record of more than 9,000 licensed acupuncturists, estimated to be providing more than 10 million treatments annually at a cost in excess of $500 million.7

Acupuncture is part of the quasi-medical area of complementary and alternative medicine, whose practitioners field more visits annually than all primary-care physicians in this country combined.8 Most acupuncturists practice the Chinese technique.9

Licensing requirements vary by state.10 As acupuncture has gained popularity and respect, and as its benefit for various medical conditions has been proved in high-quality studies, many well-established medical institutions and universities have begun to integrate it with more traditional Western medical treatments.

Acupuncture Theories

The early Chinese theories about how best to perform acupuncture were varied and sometimes conflicting.11 Early treatments using heat, bloodletting, and crude stone implementation evolved over centuries into the intricate practice known today.

Western scientists first became seriously interested in researching the effects of acupuncture in the 1970s. Many of the early studies were poorly designed, and the results were often not reproducible. They were not sufficiently randomized or blinded, and placebo controls were unreliable or nonexistent. To date, no single theory has been put forth that can explain all the phenomena associated with acupuncture treatment.

In 1991, the World Health Organization proposed a standard nomenclature for the 400 acupuncture points and the 20 meridians connecting those points.12 The precise anatomical locations of these areas have not yet been identified definitively. They have a low electrical resistance compared with surrounding tissue. Theories attempting to correlate the acupuncture points with neurovascular bundles have been postulated but remain unproved. The existence of acupuncture points has been verified with galvanometer scanning. These devices measure electrical conductance and emit an audio signal when an area of low resistance is encountered. New points have been added and the location of some of the original ones redefined by this technique.

In some of the earliest research conducted, French acupuncturists Niboyet and Grall mapped many of the points.13,14 Darras attempted to prove the existence of the meridians by tracing the flow of the radionuclide technetium TC 99m sulfur colloid after it was injected into them.15 No published reports in the English-language medical literature have reliably confirmed scientific studies documenting either the existence or location of the meridians.16

The neurohumoral theory postulates that the analgesic effects of acupuncture are related to the release of neurotransmitters such as endogenous opioids. In addition, acupuncture appears to inhibit the transmission of C-fiber pain at the level of the spinal cord.17,18 Other physiological phenomena have also been observed with acupuncture by needling. They include vasodilation, increased serum cortisol, variations in serum glucose and cholesterol levels, increased white blood cell counts, and acid suppression.5 Their significance continues to be questioned.

Evidence-Based Approach

Many studies of acupuncture have methodological flaws. The biggest problem as yet unresolved is an appropriate placebo control.19 Sham acupuncture, which involves needling non-acupuncture points, is frequently the control of choice but has serious limitations.

In 1997, the landmark NIH consensus statement was probably the most important presentation of evidence supporting the efficacy of acupuncture.20 Conclusions made about the effectiveness of acupuncture were based on evidence from reliable studies. Many promising results emerged. Specific indications for use of acupuncture were identified on the basis of published reports of its effectiveness. Efficacy in treating dental pain and post-operative and chemotherapy-induced nausea were demonstrated. Research suggested its usefulness as an adjunct or alternative treatment for lower-back pain, osteoarthritis, addiction, and stroke rehabilitation. The panel also concluded that further research would likely uncover additional uses for acupuncture.

From the standpoint of acupuncture’s effectiveness, it can clearly benefit specific patient groups. It is most commonly used as a treatment for back pain.21 Since the NIH conference, further research has confirmed its effectiveness in treating a variety of medical conditions. (See Table 1, above)

Much of the ongoing research on acupuncture has focused on the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, specifically on the areas that light up, or show brain activity, during activities or a state of pain.22-24 Acupuncture has been found to reduce the intensity of signals in such areas. The mechanism for the analgesic effects of acupuncture may be the result of reduced blood flow to the brain.24 Several studies have identified specific areas of the brain affected by pressure on various acupuncture points.25

Practical Aspects

Acupuncture treatments are extremely time efficient and require minimal equipment. They can be administered with the patient in the recumbent position or sitting upright. For initial sessions, I prefer the former, especially for younger males, who are more prone to vasovagal reactions. Any of several different methods of acupuncture can be used to stimulate points. In addition to needling, acupuncture can be conducted by electro-acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping, scraping, tapping, acupressure, or laser.

Most inpatient referrals are for pain management. Other common indications include post-operative or chemotherapy-induced nausea (emesis), anxiety, and prevention of withdrawal symptoms from narcotics.

Acupuncture Safety

Overall, acupuncture is a safe treatment method. Many large studies have confirmed that most types of acupuncture have a low rate of complications and that most of these complications are transient and minor in nature.28,29 They are incident-reporting studies, however, and have the limitations inherent in these studies. Nausea, dizziness, bruising, and needle pain are some of the most commonly reported. The rare but serious adverse events, such as pneumothorax, usually occur as a result of the practitioner’s poor training or technique.30

Future of Acupuncture

Public acceptance of, and demand for, acupuncture for pain relief is increasing. Additional clinical studies are needed, however, to expand the types of conditions for which acupuncture may be useful. It is essential to maintain a constant focus on safe practice, which would be aided by the establishment of a standardized accreditation and training system. Hospitals need to establish uniform credentialing guidelines similar to those for other procedures that require evidence of medical competence and safety.31

In February 2005, the Federal Acupuncture Coverage Act was introduced to Congress. If enacted, the measure would allow acupuncture to be covered under Part B for Medicare recipients.

The trend toward an integrated approach to patient therapy in large academic medical institutions is encouraging. The incorporation of the teaching of acupuncture within the current medical school curricula would no doubt complement this approach. TH

Joseph C. Charles, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of medicine and division education coordinator for the Department of Hospital Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic Hospital Arizona.

References

- Ananth, S. Health Forum 2005 Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals, July 19, 2006. News release, American Hospital Association.

- Veith I (trans). The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. Baltimore; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins: 1949.

- Ming Z (trans). The Medical Classic of the Yellow Emperor. Beijing; Foreign Languages Press: 2001.

- Cassedy JH. Early uses of acupuncture in the United States, with an addendum (1826) by Franklin Bache, M.D. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1974 Sep;50(8):892-906.

- Osler W. The Principles and Practice of Medicine. New York: D. Appleton and Company; 1892.

- Reston J. Now, let me tell you about my appendectomy in Peking. New York Times. July 26, 1971.

- Mitchell BB. Educational and licensing requirements for acupuncturists. J Altern Complement Med. 1996 spring;2(1):33-35.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993 Jan 28;328(4):246-252.

- Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Eisenberg DM, et al. The practice of acupuncture: who are the providers and what do they do? Ann Fam Med. 2005 Mar-Apr;3(2):151-158.

- Leake R, Broderick JE. Current licensure for acupuncture in the United States. Altern Ther Health Med. 1999 Jul;5(4):94-96.

- Shang C. The past, present, and future of meridian system research. In: Stux G, Hammerschlag R, eds. Clinical Acupuncture: Scientific Basis. Berlin: Springer; 2001:69-82.

- WHO Scientific Group on International Acupuncture Nomenclature. A proposed standard international acupuncture nomenclature: report of a WHO Scientific Group. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991.

- Niboyet JEH. Nouvelles constatations sur les proprietes electriques des points chinois. Bull Soc Acupunct. 1938;4:30-79.

- Helms JM. Acupuncture Energetics: A Clinical Approach for Physicians. Berkeley, Calif.: Medical Acupuncture Publishers; 1995:23-24.

- De Vernejoul P, Albarede P, Darras JC. Study of acupuncture meridians using radioactive tracers [in French]. Bull Acad Natl Med. 1985 Oct;169(7):1071-1075.

- Simon J, Guiraud G, Esquerre JP, et al. Acupuncture meridians demythified. Contribution of radiotracer methodology [in French]. Presse Med. 1988 Jul 2;17(26):1341-1344.

- Pomeranz B, Chiu D. Naloxone blockade of acupuncture analgesia: endorphin implicated. Life Sci. 1976 Dec 1;19(11):1757-1762.

- Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:374-383.

- Vincent C, Lewith G. Placebo controls for acupuncture studies. J R Soc Med. 1995 Apr;88(4):199-202.

- Acupuncture. NIH Consensus Statement 1997; 15:1-34

- Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, et al. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:651-663.

- Tank DW, Oqawa S, Uqurbil K. Mapping the brain with MRI. Curr Biol. 1992;525-528.

- Salvatore S. Brain imaging suggests acupuncture works, study says. [monograph on the Internet]. CNN.com with WebMD.com. Dec. 1, 1999. Available at http://archives.cnn.com/1999/HEALTH/alternative/12/01/brain.acupuncture/index.html. Last accessed April 14, 2007.

- Fang JL, Krings T, Weidemann J, et al. Functional MRI in healthy subjects during acupuncture: different effects of needle rotation in real and false acupoints. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:359-362.

- Cho ZH, Chung SC, Jones JP, et al. New findings of the correlation between acupoints and corresponding brain cortices using functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998 Mar;95(5):2670-2673. Retraction in Cho ZH, Chung SC, Lee HJ, Wong EK, Min BI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006 Jul 5;103(27):10527.

- Ulett GA, Han S, Han JS. Electroacupuncture: mechanisms and clinical application. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:129-138.

- Gam AN, Thorsen H, Lonnberg F. The effect of low-level laser therapy on musculoskeletal pain: a meta-analysis. Pain. 1993;52:63-66.

- White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A, et al. Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32, 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ. 2001 Sep 1;323(7311):485-486.

- MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, et al. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ. 2001;323:486-487. Comment in BMJ. 2001 Sep 1;323(7311):467-8. BMJ. 2002 Jan 19;324(7330):170-1.

- Chauffe RJ, Duskin AL. Pneumothorax secondary to acupuncture therapy. South Med J. 2006;99:1297-1299.

- Cohen MH, Hrbek A, Davis RB, et al. Emerging credentialing practices, malpractice liability policies, and guidelines governing complementary and alternative medical practices and dietary supplement recommendations: a descriptive study of 19 integrative health care centers in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:289-295.

- Linde K, Jobst K, Panton J. Acupuncture for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000008.

- Kleijnen J, Ter Riet G, Knipschild P. Acupuncture and asthma: a review of controlled trials. Thorax. 1991;46:799-802.

- Ter Reit G, Kleijnen J, Knipschild P. A meta-analysis of studies into the effect of acupuncture on addiction. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:379-382.

- Vincent CA. A controlled trial of the treatment of migraine by acupuncture. Clin J Pain. 1989;5:305-312.

- White AR, Rampes H, Ernst E. Acupuncture for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000009.

- Mann E. Using acupuncture and acupressure to treat postoperative emesis. Prof Nurse. 1999; 14:691-694.

- Macklin EA, Wayne PM, Kalish LA, et al. Stop hypertension with the acupuncture research program (SHARP): results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Hypertension. 2006;48:838-845.

- Lee JD, Chon JS, Jeong HK, et al. The cerebrovascular response to traditional acupuncture after stroke. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:780-784.

- Scharf HP, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, et al. Acupuncture and knee osteoarthritis: a three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:12-20.

- Martin DP, Sletten CD, Williams BA, et al. Improvement in fibromyalgia symptoms with acupuncture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:749-757.

- Lu DP, Lu GP. Anatomical relevance of some acupuncture points in the head and neck region that dictate medical or dental application depending on depth of needle insertion. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2003;28(3-4):145-156.

- Ernst E, Pittler MH. The effectiveness of acupuncture in treating acute dental pain: a systemic review. Br Dent J. 1998;184:443-447.

- Chen HM, Chen CH. Effects of acupressure at the Sanyinjiao point on primary dysmenorrhoea. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(4):380-387.

- Pouresmail Z, Ibrahimzadeh R. Effects of acupressure and ibuprofen on the severity of primary dysmenorrhea. J Tradit Chin Med. 2002 Sep; 22(3):205-210.

- Linde K, Streng A, Jurgens S, et al. Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005 May 4;293(17):2118-2125.

- Allais G, De Lorenzo C, Quirico PE, et al. Acupuncture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine without aura: a comparison with flunarizine. Headache. 2002 Oct;42(9):855-861.

- Green S, Buchbinder R, Barnsley L, et al. Acupuncture for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD003527. Review.

- Trinh KV, Phillips SD. Acupuncture for the alleviation of lateral epicondyle pain: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004:43:1085-1090.

- David J, Townsend S, Sathanathan R, et al. The effect of acupuncture on patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999 Sep;38(9):864-869. Comment in Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000 Oct;39(10):1153-1154.

- Irnich D, Behrens N, Molzen H, et al. Randomised trial of acupuncture compared with conventional massage and “sham” laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain. BMJ. 2001 Jun 30;322(7302):1574-1578. Comment in BMJ. 2001 Dec 1;323(7324):1306-7.

- White P, Lewith G, Prescott P, et al. Acupuncture versus placebo for the treatment of chronic mechanical neck pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Dec 21;141(12):911-919. Comment in Ann Intern Med. 2004 Dec 21;141(12):957-958. Ann Intern Med. 2005 May 17;142(10):873; author reply 873-874.

- Cheuk DK, Wong V. Acupuncture for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD005062.

- Griggs C, Jensen J. Effectiveness of acupuncture for migraine: critical literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006 May;54(4):491-501.

- Kim YH, Schiff E, Waalen J, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for treating cocaine addiction: a review paper. J Addict Dis. 2005;24(4):115-132.

- Forbes A, Jackson S, Walter C, et al. Acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome: a blinded placebo-controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 Jul 14;11(26):4040-4044.

- Schneider A, Enck P, Streitberger K, et al. Acupuncture treatment in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:649-654.

In 2004, 370 of 1,394 reporting hospitals offered some complementary alternative medicine (CAM) services in the U.S. Of the 370 hospitals reporting CAM services, 11.5% (42 hospitals) reported inpatient acupuncture services.1

This threefold increase since 1998 demonstrates the growing use of and demand for acupuncture services in hospitals. This trend is driven by patient demand and clinical effectiveness. Acupuncture is a safe treatment modality hospital physicians should be familiar because it can benefit patients in the inpatient setting.

Origins of Acupuncture

The first use of acupuncture is not known. The earliest medical textbook on acupuncture was The Medical Classic of the Yellow Emperor, written about 100 B.C. The first translation of this text into English was in 1949.2

The book outlined the theory of a system of six sets of symmetrical channels on the body’s surface, which it called meridians; along these, it posited an intricate network of points.3 Needling the points was supposed to manipulate or release the flow of energy or life force—Qi—to the internal organs, thereby alleviating symptoms. Heating acupuncture points with burning herbs—moxibustion—was also purported to relieve pain.

Acupuncture in the U.S.

The first documented use of acupuncture in the United States occurred in the 19th century. In 1826, Bache used it to treat lumbago.4 During that same era, William Mosley used acupuncture to treat patients with lumbago and sciatica.5

In 1971, a first-person account of the use of acupuncture by New York Times reporter James Reston excited great interest in the technique. Reston was introduced to the procedure to relieve pain after an emergency appendectomy during a trip to China with Henry A. Kissinger.6

Since then, there has been a steady increase in the use of acupuncture by physicians. The American Academy of Medical Acupuncture, the only physician-based acupuncture society in North America, was formed in 1987; in 1992, the Office of Alternative Medicine was created within the NIH. In November 1997, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) removed the experimental designation for acupuncture needles and approved their use by licensed practitioners. By 1993, the FDA had a record of more than 9,000 licensed acupuncturists, estimated to be providing more than 10 million treatments annually at a cost in excess of $500 million.7

Acupuncture is part of the quasi-medical area of complementary and alternative medicine, whose practitioners field more visits annually than all primary-care physicians in this country combined.8 Most acupuncturists practice the Chinese technique.9

Licensing requirements vary by state.10 As acupuncture has gained popularity and respect, and as its benefit for various medical conditions has been proved in high-quality studies, many well-established medical institutions and universities have begun to integrate it with more traditional Western medical treatments.

Acupuncture Theories

The early Chinese theories about how best to perform acupuncture were varied and sometimes conflicting.11 Early treatments using heat, bloodletting, and crude stone implementation evolved over centuries into the intricate practice known today.

Western scientists first became seriously interested in researching the effects of acupuncture in the 1970s. Many of the early studies were poorly designed, and the results were often not reproducible. They were not sufficiently randomized or blinded, and placebo controls were unreliable or nonexistent. To date, no single theory has been put forth that can explain all the phenomena associated with acupuncture treatment.

In 1991, the World Health Organization proposed a standard nomenclature for the 400 acupuncture points and the 20 meridians connecting those points.12 The precise anatomical locations of these areas have not yet been identified definitively. They have a low electrical resistance compared with surrounding tissue. Theories attempting to correlate the acupuncture points with neurovascular bundles have been postulated but remain unproved. The existence of acupuncture points has been verified with galvanometer scanning. These devices measure electrical conductance and emit an audio signal when an area of low resistance is encountered. New points have been added and the location of some of the original ones redefined by this technique.

In some of the earliest research conducted, French acupuncturists Niboyet and Grall mapped many of the points.13,14 Darras attempted to prove the existence of the meridians by tracing the flow of the radionuclide technetium TC 99m sulfur colloid after it was injected into them.15 No published reports in the English-language medical literature have reliably confirmed scientific studies documenting either the existence or location of the meridians.16

The neurohumoral theory postulates that the analgesic effects of acupuncture are related to the release of neurotransmitters such as endogenous opioids. In addition, acupuncture appears to inhibit the transmission of C-fiber pain at the level of the spinal cord.17,18 Other physiological phenomena have also been observed with acupuncture by needling. They include vasodilation, increased serum cortisol, variations in serum glucose and cholesterol levels, increased white blood cell counts, and acid suppression.5 Their significance continues to be questioned.

Evidence-Based Approach

Many studies of acupuncture have methodological flaws. The biggest problem as yet unresolved is an appropriate placebo control.19 Sham acupuncture, which involves needling non-acupuncture points, is frequently the control of choice but has serious limitations.

In 1997, the landmark NIH consensus statement was probably the most important presentation of evidence supporting the efficacy of acupuncture.20 Conclusions made about the effectiveness of acupuncture were based on evidence from reliable studies. Many promising results emerged. Specific indications for use of acupuncture were identified on the basis of published reports of its effectiveness. Efficacy in treating dental pain and post-operative and chemotherapy-induced nausea were demonstrated. Research suggested its usefulness as an adjunct or alternative treatment for lower-back pain, osteoarthritis, addiction, and stroke rehabilitation. The panel also concluded that further research would likely uncover additional uses for acupuncture.

From the standpoint of acupuncture’s effectiveness, it can clearly benefit specific patient groups. It is most commonly used as a treatment for back pain.21 Since the NIH conference, further research has confirmed its effectiveness in treating a variety of medical conditions. (See Table 1, above)

Much of the ongoing research on acupuncture has focused on the use of functional magnetic resonance imaging of the brain, specifically on the areas that light up, or show brain activity, during activities or a state of pain.22-24 Acupuncture has been found to reduce the intensity of signals in such areas. The mechanism for the analgesic effects of acupuncture may be the result of reduced blood flow to the brain.24 Several studies have identified specific areas of the brain affected by pressure on various acupuncture points.25

Practical Aspects

Acupuncture treatments are extremely time efficient and require minimal equipment. They can be administered with the patient in the recumbent position or sitting upright. For initial sessions, I prefer the former, especially for younger males, who are more prone to vasovagal reactions. Any of several different methods of acupuncture can be used to stimulate points. In addition to needling, acupuncture can be conducted by electro-acupuncture, moxibustion, cupping, scraping, tapping, acupressure, or laser.

Most inpatient referrals are for pain management. Other common indications include post-operative or chemotherapy-induced nausea (emesis), anxiety, and prevention of withdrawal symptoms from narcotics.

Acupuncture Safety

Overall, acupuncture is a safe treatment method. Many large studies have confirmed that most types of acupuncture have a low rate of complications and that most of these complications are transient and minor in nature.28,29 They are incident-reporting studies, however, and have the limitations inherent in these studies. Nausea, dizziness, bruising, and needle pain are some of the most commonly reported. The rare but serious adverse events, such as pneumothorax, usually occur as a result of the practitioner’s poor training or technique.30

Future of Acupuncture

Public acceptance of, and demand for, acupuncture for pain relief is increasing. Additional clinical studies are needed, however, to expand the types of conditions for which acupuncture may be useful. It is essential to maintain a constant focus on safe practice, which would be aided by the establishment of a standardized accreditation and training system. Hospitals need to establish uniform credentialing guidelines similar to those for other procedures that require evidence of medical competence and safety.31

In February 2005, the Federal Acupuncture Coverage Act was introduced to Congress. If enacted, the measure would allow acupuncture to be covered under Part B for Medicare recipients.

The trend toward an integrated approach to patient therapy in large academic medical institutions is encouraging. The incorporation of the teaching of acupuncture within the current medical school curricula would no doubt complement this approach. TH

Joseph C. Charles, MD, FACP, is an assistant professor of medicine and division education coordinator for the Department of Hospital Internal Medicine at the Mayo Clinic Hospital Arizona.

References

- Ananth, S. Health Forum 2005 Complementary and Alternative Medicine Survey of Hospitals, July 19, 2006. News release, American Hospital Association.

- Veith I (trans). The Yellow Emperor’s Classic of Internal Medicine. Baltimore; Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins: 1949.

- Ming Z (trans). The Medical Classic of the Yellow Emperor. Beijing; Foreign Languages Press: 2001.

- Cassedy JH. Early uses of acupuncture in the United States, with an addendum (1826) by Franklin Bache, M.D. Bull N Y Acad Med. 1974 Sep;50(8):892-906.

- Osler W. The Principles and Practice of Medicine. New York: D. Appleton and Company; 1892.

- Reston J. Now, let me tell you about my appendectomy in Peking. New York Times. July 26, 1971.

- Mitchell BB. Educational and licensing requirements for acupuncturists. J Altern Complement Med. 1996 spring;2(1):33-35.

- Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional medicine in the United States. Prevalence, costs, and patterns of use. N Engl J Med. 1993 Jan 28;328(4):246-252.

- Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Eisenberg DM, et al. The practice of acupuncture: who are the providers and what do they do? Ann Fam Med. 2005 Mar-Apr;3(2):151-158.

- Leake R, Broderick JE. Current licensure for acupuncture in the United States. Altern Ther Health Med. 1999 Jul;5(4):94-96.

- Shang C. The past, present, and future of meridian system research. In: Stux G, Hammerschlag R, eds. Clinical Acupuncture: Scientific Basis. Berlin: Springer; 2001:69-82.

- WHO Scientific Group on International Acupuncture Nomenclature. A proposed standard international acupuncture nomenclature: report of a WHO Scientific Group. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1991.

- Niboyet JEH. Nouvelles constatations sur les proprietes electriques des points chinois. Bull Soc Acupunct. 1938;4:30-79.

- Helms JM. Acupuncture Energetics: A Clinical Approach for Physicians. Berkeley, Calif.: Medical Acupuncture Publishers; 1995:23-24.

- De Vernejoul P, Albarede P, Darras JC. Study of acupuncture meridians using radioactive tracers [in French]. Bull Acad Natl Med. 1985 Oct;169(7):1071-1075.

- Simon J, Guiraud G, Esquerre JP, et al. Acupuncture meridians demythified. Contribution of radiotracer methodology [in French]. Presse Med. 1988 Jul 2;17(26):1341-1344.

- Pomeranz B, Chiu D. Naloxone blockade of acupuncture analgesia: endorphin implicated. Life Sci. 1976 Dec 1;19(11):1757-1762.

- Kaptchuk TJ. Acupuncture: theory, efficacy, and practice. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:374-383.

- Vincent C, Lewith G. Placebo controls for acupuncture studies. J R Soc Med. 1995 Apr;88(4):199-202.

- Acupuncture. NIH Consensus Statement 1997; 15:1-34

- Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, et al. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:651-663.

- Tank DW, Oqawa S, Uqurbil K. Mapping the brain with MRI. Curr Biol. 1992;525-528.

- Salvatore S. Brain imaging suggests acupuncture works, study says. [monograph on the Internet]. CNN.com with WebMD.com. Dec. 1, 1999. Available at http://archives.cnn.com/1999/HEALTH/alternative/12/01/brain.acupuncture/index.html. Last accessed April 14, 2007.

- Fang JL, Krings T, Weidemann J, et al. Functional MRI in healthy subjects during acupuncture: different effects of needle rotation in real and false acupoints. Neuroradiology. 2004;46:359-362.

- Cho ZH, Chung SC, Jones JP, et al. New findings of the correlation between acupoints and corresponding brain cortices using functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998 Mar;95(5):2670-2673. Retraction in Cho ZH, Chung SC, Lee HJ, Wong EK, Min BI. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006 Jul 5;103(27):10527.

- Ulett GA, Han S, Han JS. Electroacupuncture: mechanisms and clinical application. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:129-138.

- Gam AN, Thorsen H, Lonnberg F. The effect of low-level laser therapy on musculoskeletal pain: a meta-analysis. Pain. 1993;52:63-66.

- White A, Hayhoe S, Hart A, et al. Adverse events following acupuncture: prospective survey of 32, 000 consultations with doctors and physiotherapists. BMJ. 2001 Sep 1;323(7311):485-486.

- MacPherson H, Thomas K, Walters S, et al. The York acupuncture safety study: prospective survey of 34 000 treatments by traditional acupuncturists. BMJ. 2001;323:486-487. Comment in BMJ. 2001 Sep 1;323(7311):467-8. BMJ. 2002 Jan 19;324(7330):170-1.

- Chauffe RJ, Duskin AL. Pneumothorax secondary to acupuncture therapy. South Med J. 2006;99:1297-1299.

- Cohen MH, Hrbek A, Davis RB, et al. Emerging credentialing practices, malpractice liability policies, and guidelines governing complementary and alternative medical practices and dietary supplement recommendations: a descriptive study of 19 integrative health care centers in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:289-295.

- Linde K, Jobst K, Panton J. Acupuncture for chronic asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2):CD000008.

- Kleijnen J, Ter Riet G, Knipschild P. Acupuncture and asthma: a review of controlled trials. Thorax. 1991;46:799-802.

- Ter Reit G, Kleijnen J, Knipschild P. A meta-analysis of studies into the effect of acupuncture on addiction. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40:379-382.

- Vincent CA. A controlled trial of the treatment of migraine by acupuncture. Clin J Pain. 1989;5:305-312.

- White AR, Rampes H, Ernst E. Acupuncture for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000009.

- Mann E. Using acupuncture and acupressure to treat postoperative emesis. Prof Nurse. 1999; 14:691-694.

- Macklin EA, Wayne PM, Kalish LA, et al. Stop hypertension with the acupuncture research program (SHARP): results of a randomized, controlled clinical trial. Hypertension. 2006;48:838-845.

- Lee JD, Chon JS, Jeong HK, et al. The cerebrovascular response to traditional acupuncture after stroke. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:780-784.

- Scharf HP, Mansmann U, Streitberger K, et al. Acupuncture and knee osteoarthritis: a three-armed randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:12-20.

- Martin DP, Sletten CD, Williams BA, et al. Improvement in fibromyalgia symptoms with acupuncture: results of a randomized controlled trial. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81:749-757.

- Lu DP, Lu GP. Anatomical relevance of some acupuncture points in the head and neck region that dictate medical or dental application depending on depth of needle insertion. Acupunct Electrother Res. 2003;28(3-4):145-156.

- Ernst E, Pittler MH. The effectiveness of acupuncture in treating acute dental pain: a systemic review. Br Dent J. 1998;184:443-447.

- Chen HM, Chen CH. Effects of acupressure at the Sanyinjiao point on primary dysmenorrhoea. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48(4):380-387.

- Pouresmail Z, Ibrahimzadeh R. Effects of acupressure and ibuprofen on the severity of primary dysmenorrhea. J Tradit Chin Med. 2002 Sep; 22(3):205-210.

- Linde K, Streng A, Jurgens S, et al. Acupuncture for patients with migraine: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005 May 4;293(17):2118-2125.

- Allais G, De Lorenzo C, Quirico PE, et al. Acupuncture in the prophylactic treatment of migraine without aura: a comparison with flunarizine. Headache. 2002 Oct;42(9):855-861.

- Green S, Buchbinder R, Barnsley L, et al. Acupuncture for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD003527. Review.

- Trinh KV, Phillips SD. Acupuncture for the alleviation of lateral epicondyle pain: a systematic review. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2004:43:1085-1090.

- David J, Townsend S, Sathanathan R, et al. The effect of acupuncture on patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 1999 Sep;38(9):864-869. Comment in Rheumatology (Oxford). 2000 Oct;39(10):1153-1154.

- Irnich D, Behrens N, Molzen H, et al. Randomised trial of acupuncture compared with conventional massage and “sham” laser acupuncture for treatment of chronic neck pain. BMJ. 2001 Jun 30;322(7302):1574-1578. Comment in BMJ. 2001 Dec 1;323(7324):1306-7.

- White P, Lewith G, Prescott P, et al. Acupuncture versus placebo for the treatment of chronic mechanical neck pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Dec 21;141(12):911-919. Comment in Ann Intern Med. 2004 Dec 21;141(12):957-958. Ann Intern Med. 2005 May 17;142(10):873; author reply 873-874.

- Cheuk DK, Wong V. Acupuncture for epilepsy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD005062.

- Griggs C, Jensen J. Effectiveness of acupuncture for migraine: critical literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006 May;54(4):491-501.

- Kim YH, Schiff E, Waalen J, et al. Efficacy of acupuncture for treating cocaine addiction: a review paper. J Addict Dis. 2005;24(4):115-132.

- Forbes A, Jackson S, Walter C, et al. Acupuncture for irritable bowel syndrome: a blinded placebo-controlled trial. World J Gastroenterol. 2005 Jul 14;11(26):4040-4044.

- Schneider A, Enck P, Streitberger K, et al. Acupuncture treatment in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2006;55:649-654.