User login

A resident’s guide to lithium

Lithium has been used in psychiatry for more than half a century and is considered the gold standard for treating acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.1 Evidence supports its use to reduce suicidal behavior and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder.2 However, lithium has fallen out of favor because of its narrow therapeutic index as well as the introduction of newer psychotropic medications that have a quicker onset of action and do not require strict blood monitoring. For residents early in their training, keeping track of the laboratory monitoring and medical screening can be confusing. Different institutions and countries have specific guidelines and recommendations for monitoring patients receiving lithium, which adds to the confusion.

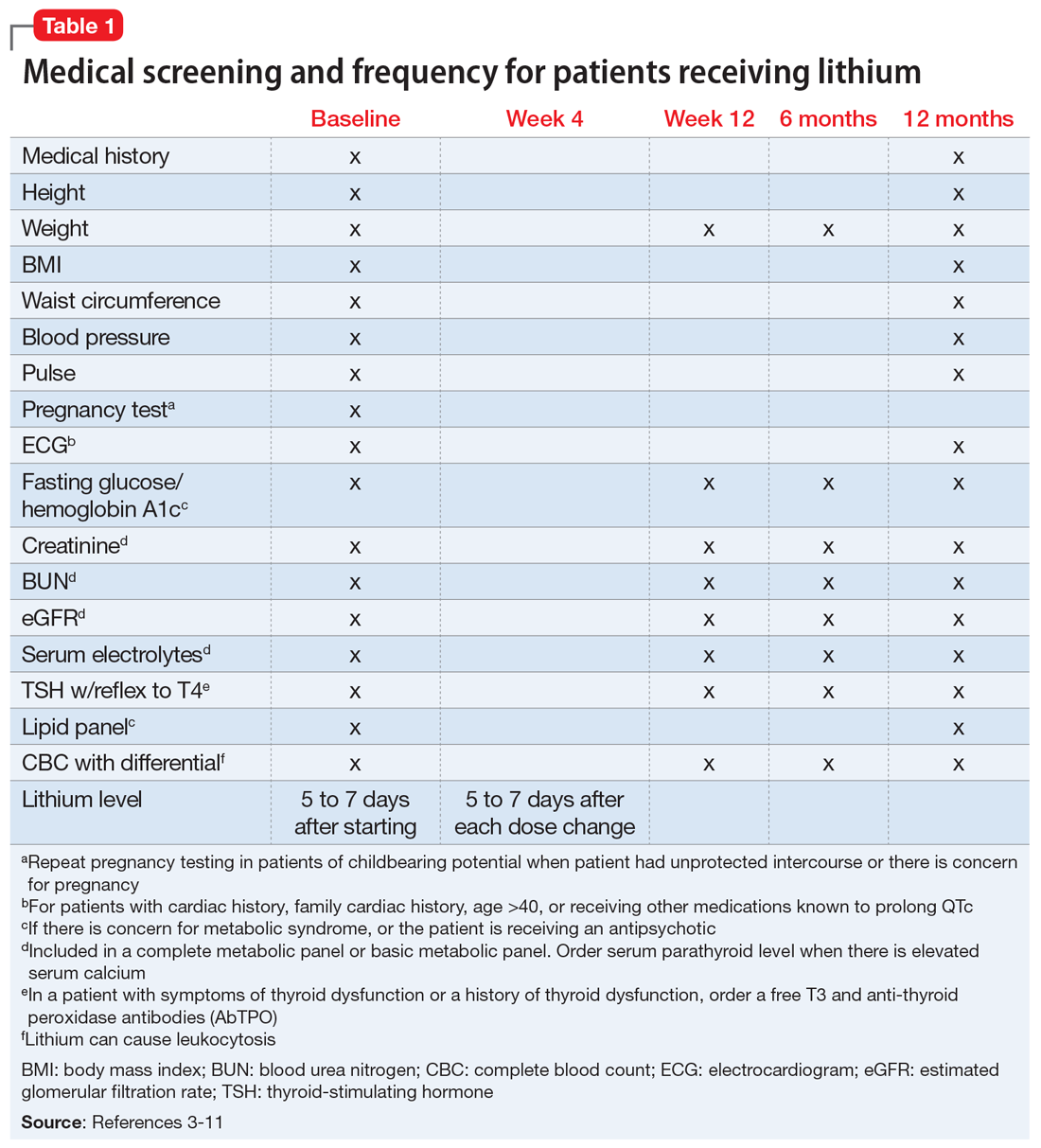

We completed a literature review to develop clear and concise recommendations for lithium monitoring for residents in our psychiatry residency program. These recommendations outline screening at baseline and after patients treated with lithium achieve stability. Table 13-11 outlines medical screening parameters, including bloodwork, that should be completed before initiating treatment, and how often such screening should be repeated. Table 2 incorporates these parameters into progress notes in the electronic medical record to keep track of the laboratory values and when they were last drawn. Our aim is to help residents stay organized and prevent missed screenings.

How often should lithium levels be monitored?

After starting a patient on lithium, check the level within 5 to 7 days, and 5 to 7 days after each dose change. Draw the lithium level 10 to 14 hours after the patient’s last dose (12 hours is best).1 Because of dosage changes, lithium levels usually are monitored more frequently during the first 3 months of treatment until therapeutic levels are reached or symptoms are controlled. It is recommended to monitor lithium levels every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after the first year of treatment once the patient is stable and considering age, medical health, and how consistently a patient reports symptoms/adverse effects.3,5 Continue monitoring levels every 3 months in older adults; in patients with renal dysfunction, thyroid dysfunction, hypercalcemia, or other significant medical comorbidities; and in those who are taking medications that affect lithium, such as pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can raise lithium levels), certain antihypertensives (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors can raise lithium levels), and diuretics (thiazide diuretics can raise lithium levels; osmotic diuretics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can reduce lithium levels).1,3,5

Lithium levels could vary by up to 0.5 mEq/L during transition between manic, euthymic, and depressive states.12 On a consistent dosage, lithium levels decrease during mania because of hemodilution, and increase during depression secondary to physiological effects specific to these episodes.13,14

Recommendations for plasma lithium levels (trough levels)

Mania. Lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L often are needed to achieve symptom control during manic episodes.15 As levels approach 1.5 mEq/L, patients are at increased risk for intolerable adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) and toxicity.16,17 Adverse effects at higher levels may result in patients abruptly discontinuing lithium. Patients who experience mania before a depressive episode at illness onsettend to have a better treatment response with lithium.18 Lithium monotherapy has been shown to be less effective for acute mania than antipsychotics or combination therapies.19 Consider combining lithium with valproate or antipsychotics for patients who have tolerated lithium in the past and plan to use lithium for maintenance treatment.20

Maintenance. In adults, the lithium level should be 0.60 to 80mEq/L, but consider levels of 0.40 to 0.60 mEq/L in patients who have a good response to lithium but develop adverse effects at higher levels.21 For patients who do not respond to treatment, such as those with severe mania, maintenance levels can be increased to 0.76 to 0.90 mEq/L.22 These same recommendations for maintenance levels can be used for children and adolescents. In older adults, aim for maintenance levels of 0.4 to 0.6 mEq/L. For patients age 65 to 79, the maximum level is 0.7 to 0.8 mEq/L, and should not exceed 0.7 mEq/L in patients age >80. Lithium levels <0.4 mEq/L do not appear to be effective.21

Depression. Aim for a lithium level of 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for patients with depression.11

Continue to: Renal function monitoring frequency

Renal function monitoring frequency

Obtain a basic metabolic panel or comprehensive metabolic panel to establish baseline levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Repeat testing at Week 12 and at 6 months to detect any changes. Renal function can be monitored every 6 to 12 months in stable patients, but should be closely watched when a patient’s clinical status changes.3 A new lower eGFR value after starting lithium therapy should be investigated with a repeat test in 2 weeks.23 Mild elevations in creatinine should be monitored, and further medical workup with a nephrologist is recommended for patients with a creatinine level ≥1.6 mg/dL.24 It is important to note that creatinine might remain within normal limits if there is considerable reduction in glomerular function. Creatinine levels could vary because of body mass and diet. Creatinine levels can be low in nonmuscular patients and elevated in patients who consume large amounts of protein.23,25

Ordering a basic metabolic panel also allows electrolyte monitoring. Hyponatremia and dehydration can lead to elevated lithium levels and result in toxicity; hypokalemia might increase the risk of lithium-induced cardiac toxicity. Monitor calcium (corrected serum calcium) because hypercalcemia has been seen in patients treated with lithium.

Thyroid function monitoring frequency

Obtain levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone with reflex to free T4 at baseline, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Monitor thyroid function every 6 to 12 months in stable patients and when a patient’s clinical status changes, such as with new reports of medical or psychiatric symptoms and when there is concern for thyroid dysfunction.3

Lithium and neurotoxicity

Lithium is known to have neurotoxic effects, such as effects on fast-acting neurons leading to dyscoordination or tremor, even at therapeutic levels.26 This is especially the case when lithium is combined with an antipsychotic,26,27 a combination that is used to treat bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Older adults are at greater risk for neurotoxicity because of physiological changes associated with increasing age.28

Educate patients about adherence, diet, and exercise

Patients might stop taking their psychotropic medications when they start feeling better. Instruct patients to discuss discontinuation with the prescribing clinician before they stop any medication. Educate patients that rapidly discontinuing lithium therapy puts them at high risk of relapse29 and increases the risk of developing treatment-refractory symptoms.23,30 Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated and maintaining adequate sodium in their diet.17,31 Consuming excessive sodium can reduce lithium levels.17,32 Lithium levels could increase when patients experience excessive sweating, such as during exercise or being outside on warm days, because of sodium and volume loss.17,33

1. Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2

2. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40345-015-0028-y

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1-50.

4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1‐44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025

5. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar disorder: the NICE guideline on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

6. Kupka R, Goossens P, van Bendegem M, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP); 2015. Accessed August 10, 2020. http://www.nvvp.net/stream/richtlijn-bipolaire-stoornissen-2015

7. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087‐1206. doi:10.1177/0004867415617657

8. Nederlof M, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG, et al. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: an international survey. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0120-1

9. Leo RJ, Sharma M, Chrostowski DA. A case of lithium-induced symptomatic hypercalcemia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09l00917. doi:10.4088/PCC.09l00917yel

10. McHenry CR, Lee K. Lithium therapy and disorders of the parathyroid glands. Endocr Pract. 1996;2(2):103-109. doi:10.4158/EP.2.2.103

11. Stahl SM. The prescribers guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

12. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D. Variations of serum lithium concentrations correlated with the phases of manic-depressive psychosis. Agressologie. 1978;19(D):219-222.

13. Rittmannsberger H, Malsiner-Walli G. Mood-dependent changes of serum lithium concentration in a rapid cycling patient maintained on stable doses of lithium carbonate. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(3):333-337. doi:10.1111/bdi.12066

14. Hochman E, Weizman A, Valevski A, et al. Association between bipolar episodes and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):781-789. doi:10.1111/bdi.12248

15. Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377

16. Boltan DD, Fenves AZ. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(3):261-263. doi:10.1080/08998280.2008.11928407

17. Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

18. Tighe SK, Mahon PB, Potash JB. Predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):209-226. doi:10.1177/2040622311399173

19. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8

20. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of co-therapy vs monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;115(1):12-20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x

21. Nolen WA, Licht RW, Young AH, et al; ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):394-409. doi:10.1111/bdi.12805

22. Maj M, Starace F, Nolfe G, et al. Minimum plasma lithium levels required for effective prophylaxis in DSM III bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):420-423. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017280

23. Gupta S, Kripalani M, Khastgir U, et al. Management of the renal adverse effects of lithium. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2013;19(6):457-466. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.112.010306

24. Gitlin M. Lithium and the kidney: an updated review. Drug Saf. 1999;20(3):231-243. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920030-00004

25. Jefferson JW. A clinician’s guide to monitoring kidney function in lithium-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1153-1157. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05917yel

26. Shah VC, Kayathi P, Singh G, et al. Enhance your understanding of lithium neurotoxicity. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3):10.4088/PCC.14l01767. doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01767

27. Netto I, Phutane VH. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01197

28. Mohandas E, Rajmohan V. Lithium use in special populations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):211-218. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37325

29. Gupta S, Khastgir U. Drug information update. Lithium and chronic kidney disease: debates and dilemmas. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):216-220. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.054031

30. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0322

31. Timmer RT, Sands JM. Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(3):666-674.

32. Demers RG, Heninger GR. Sodium intake and lithium treatment in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128(1):100-104. doi:10.1176/ajp.128.1.100

33. Hedya SA, Avula A, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

Lithium has been used in psychiatry for more than half a century and is considered the gold standard for treating acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.1 Evidence supports its use to reduce suicidal behavior and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder.2 However, lithium has fallen out of favor because of its narrow therapeutic index as well as the introduction of newer psychotropic medications that have a quicker onset of action and do not require strict blood monitoring. For residents early in their training, keeping track of the laboratory monitoring and medical screening can be confusing. Different institutions and countries have specific guidelines and recommendations for monitoring patients receiving lithium, which adds to the confusion.

We completed a literature review to develop clear and concise recommendations for lithium monitoring for residents in our psychiatry residency program. These recommendations outline screening at baseline and after patients treated with lithium achieve stability. Table 13-11 outlines medical screening parameters, including bloodwork, that should be completed before initiating treatment, and how often such screening should be repeated. Table 2 incorporates these parameters into progress notes in the electronic medical record to keep track of the laboratory values and when they were last drawn. Our aim is to help residents stay organized and prevent missed screenings.

How often should lithium levels be monitored?

After starting a patient on lithium, check the level within 5 to 7 days, and 5 to 7 days after each dose change. Draw the lithium level 10 to 14 hours after the patient’s last dose (12 hours is best).1 Because of dosage changes, lithium levels usually are monitored more frequently during the first 3 months of treatment until therapeutic levels are reached or symptoms are controlled. It is recommended to monitor lithium levels every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after the first year of treatment once the patient is stable and considering age, medical health, and how consistently a patient reports symptoms/adverse effects.3,5 Continue monitoring levels every 3 months in older adults; in patients with renal dysfunction, thyroid dysfunction, hypercalcemia, or other significant medical comorbidities; and in those who are taking medications that affect lithium, such as pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can raise lithium levels), certain antihypertensives (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors can raise lithium levels), and diuretics (thiazide diuretics can raise lithium levels; osmotic diuretics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can reduce lithium levels).1,3,5

Lithium levels could vary by up to 0.5 mEq/L during transition between manic, euthymic, and depressive states.12 On a consistent dosage, lithium levels decrease during mania because of hemodilution, and increase during depression secondary to physiological effects specific to these episodes.13,14

Recommendations for plasma lithium levels (trough levels)

Mania. Lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L often are needed to achieve symptom control during manic episodes.15 As levels approach 1.5 mEq/L, patients are at increased risk for intolerable adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) and toxicity.16,17 Adverse effects at higher levels may result in patients abruptly discontinuing lithium. Patients who experience mania before a depressive episode at illness onsettend to have a better treatment response with lithium.18 Lithium monotherapy has been shown to be less effective for acute mania than antipsychotics or combination therapies.19 Consider combining lithium with valproate or antipsychotics for patients who have tolerated lithium in the past and plan to use lithium for maintenance treatment.20

Maintenance. In adults, the lithium level should be 0.60 to 80mEq/L, but consider levels of 0.40 to 0.60 mEq/L in patients who have a good response to lithium but develop adverse effects at higher levels.21 For patients who do not respond to treatment, such as those with severe mania, maintenance levels can be increased to 0.76 to 0.90 mEq/L.22 These same recommendations for maintenance levels can be used for children and adolescents. In older adults, aim for maintenance levels of 0.4 to 0.6 mEq/L. For patients age 65 to 79, the maximum level is 0.7 to 0.8 mEq/L, and should not exceed 0.7 mEq/L in patients age >80. Lithium levels <0.4 mEq/L do not appear to be effective.21

Depression. Aim for a lithium level of 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for patients with depression.11

Continue to: Renal function monitoring frequency

Renal function monitoring frequency

Obtain a basic metabolic panel or comprehensive metabolic panel to establish baseline levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Repeat testing at Week 12 and at 6 months to detect any changes. Renal function can be monitored every 6 to 12 months in stable patients, but should be closely watched when a patient’s clinical status changes.3 A new lower eGFR value after starting lithium therapy should be investigated with a repeat test in 2 weeks.23 Mild elevations in creatinine should be monitored, and further medical workup with a nephrologist is recommended for patients with a creatinine level ≥1.6 mg/dL.24 It is important to note that creatinine might remain within normal limits if there is considerable reduction in glomerular function. Creatinine levels could vary because of body mass and diet. Creatinine levels can be low in nonmuscular patients and elevated in patients who consume large amounts of protein.23,25

Ordering a basic metabolic panel also allows electrolyte monitoring. Hyponatremia and dehydration can lead to elevated lithium levels and result in toxicity; hypokalemia might increase the risk of lithium-induced cardiac toxicity. Monitor calcium (corrected serum calcium) because hypercalcemia has been seen in patients treated with lithium.

Thyroid function monitoring frequency

Obtain levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone with reflex to free T4 at baseline, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Monitor thyroid function every 6 to 12 months in stable patients and when a patient’s clinical status changes, such as with new reports of medical or psychiatric symptoms and when there is concern for thyroid dysfunction.3

Lithium and neurotoxicity

Lithium is known to have neurotoxic effects, such as effects on fast-acting neurons leading to dyscoordination or tremor, even at therapeutic levels.26 This is especially the case when lithium is combined with an antipsychotic,26,27 a combination that is used to treat bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Older adults are at greater risk for neurotoxicity because of physiological changes associated with increasing age.28

Educate patients about adherence, diet, and exercise

Patients might stop taking their psychotropic medications when they start feeling better. Instruct patients to discuss discontinuation with the prescribing clinician before they stop any medication. Educate patients that rapidly discontinuing lithium therapy puts them at high risk of relapse29 and increases the risk of developing treatment-refractory symptoms.23,30 Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated and maintaining adequate sodium in their diet.17,31 Consuming excessive sodium can reduce lithium levels.17,32 Lithium levels could increase when patients experience excessive sweating, such as during exercise or being outside on warm days, because of sodium and volume loss.17,33

Lithium has been used in psychiatry for more than half a century and is considered the gold standard for treating acute mania and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.1 Evidence supports its use to reduce suicidal behavior and as an adjunctive treatment for major depressive disorder.2 However, lithium has fallen out of favor because of its narrow therapeutic index as well as the introduction of newer psychotropic medications that have a quicker onset of action and do not require strict blood monitoring. For residents early in their training, keeping track of the laboratory monitoring and medical screening can be confusing. Different institutions and countries have specific guidelines and recommendations for monitoring patients receiving lithium, which adds to the confusion.

We completed a literature review to develop clear and concise recommendations for lithium monitoring for residents in our psychiatry residency program. These recommendations outline screening at baseline and after patients treated with lithium achieve stability. Table 13-11 outlines medical screening parameters, including bloodwork, that should be completed before initiating treatment, and how often such screening should be repeated. Table 2 incorporates these parameters into progress notes in the electronic medical record to keep track of the laboratory values and when they were last drawn. Our aim is to help residents stay organized and prevent missed screenings.

How often should lithium levels be monitored?

After starting a patient on lithium, check the level within 5 to 7 days, and 5 to 7 days after each dose change. Draw the lithium level 10 to 14 hours after the patient’s last dose (12 hours is best).1 Because of dosage changes, lithium levels usually are monitored more frequently during the first 3 months of treatment until therapeutic levels are reached or symptoms are controlled. It is recommended to monitor lithium levels every 3 months for the first year and every 6 months after the first year of treatment once the patient is stable and considering age, medical health, and how consistently a patient reports symptoms/adverse effects.3,5 Continue monitoring levels every 3 months in older adults; in patients with renal dysfunction, thyroid dysfunction, hypercalcemia, or other significant medical comorbidities; and in those who are taking medications that affect lithium, such as pain medications (nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs can raise lithium levels), certain antihypertensives (angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitors can raise lithium levels), and diuretics (thiazide diuretics can raise lithium levels; osmotic diuretics and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors can reduce lithium levels).1,3,5

Lithium levels could vary by up to 0.5 mEq/L during transition between manic, euthymic, and depressive states.12 On a consistent dosage, lithium levels decrease during mania because of hemodilution, and increase during depression secondary to physiological effects specific to these episodes.13,14

Recommendations for plasma lithium levels (trough levels)

Mania. Lithium levels of 0.8 to 1.2 mEq/L often are needed to achieve symptom control during manic episodes.15 As levels approach 1.5 mEq/L, patients are at increased risk for intolerable adverse effects (eg, nausea and vomiting) and toxicity.16,17 Adverse effects at higher levels may result in patients abruptly discontinuing lithium. Patients who experience mania before a depressive episode at illness onsettend to have a better treatment response with lithium.18 Lithium monotherapy has been shown to be less effective for acute mania than antipsychotics or combination therapies.19 Consider combining lithium with valproate or antipsychotics for patients who have tolerated lithium in the past and plan to use lithium for maintenance treatment.20

Maintenance. In adults, the lithium level should be 0.60 to 80mEq/L, but consider levels of 0.40 to 0.60 mEq/L in patients who have a good response to lithium but develop adverse effects at higher levels.21 For patients who do not respond to treatment, such as those with severe mania, maintenance levels can be increased to 0.76 to 0.90 mEq/L.22 These same recommendations for maintenance levels can be used for children and adolescents. In older adults, aim for maintenance levels of 0.4 to 0.6 mEq/L. For patients age 65 to 79, the maximum level is 0.7 to 0.8 mEq/L, and should not exceed 0.7 mEq/L in patients age >80. Lithium levels <0.4 mEq/L do not appear to be effective.21

Depression. Aim for a lithium level of 0.6 to 1.0 mEq/L for patients with depression.11

Continue to: Renal function monitoring frequency

Renal function monitoring frequency

Obtain a basic metabolic panel or comprehensive metabolic panel to establish baseline levels of creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). Repeat testing at Week 12 and at 6 months to detect any changes. Renal function can be monitored every 6 to 12 months in stable patients, but should be closely watched when a patient’s clinical status changes.3 A new lower eGFR value after starting lithium therapy should be investigated with a repeat test in 2 weeks.23 Mild elevations in creatinine should be monitored, and further medical workup with a nephrologist is recommended for patients with a creatinine level ≥1.6 mg/dL.24 It is important to note that creatinine might remain within normal limits if there is considerable reduction in glomerular function. Creatinine levels could vary because of body mass and diet. Creatinine levels can be low in nonmuscular patients and elevated in patients who consume large amounts of protein.23,25

Ordering a basic metabolic panel also allows electrolyte monitoring. Hyponatremia and dehydration can lead to elevated lithium levels and result in toxicity; hypokalemia might increase the risk of lithium-induced cardiac toxicity. Monitor calcium (corrected serum calcium) because hypercalcemia has been seen in patients treated with lithium.

Thyroid function monitoring frequency

Obtain levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone with reflex to free T4 at baseline, 12 weeks, and 6 months. Monitor thyroid function every 6 to 12 months in stable patients and when a patient’s clinical status changes, such as with new reports of medical or psychiatric symptoms and when there is concern for thyroid dysfunction.3

Lithium and neurotoxicity

Lithium is known to have neurotoxic effects, such as effects on fast-acting neurons leading to dyscoordination or tremor, even at therapeutic levels.26 This is especially the case when lithium is combined with an antipsychotic,26,27 a combination that is used to treat bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Older adults are at greater risk for neurotoxicity because of physiological changes associated with increasing age.28

Educate patients about adherence, diet, and exercise

Patients might stop taking their psychotropic medications when they start feeling better. Instruct patients to discuss discontinuation with the prescribing clinician before they stop any medication. Educate patients that rapidly discontinuing lithium therapy puts them at high risk of relapse29 and increases the risk of developing treatment-refractory symptoms.23,30 Emphasize the importance of staying hydrated and maintaining adequate sodium in their diet.17,31 Consuming excessive sodium can reduce lithium levels.17,32 Lithium levels could increase when patients experience excessive sweating, such as during exercise or being outside on warm days, because of sodium and volume loss.17,33

1. Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2

2. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40345-015-0028-y

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1-50.

4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1‐44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025

5. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar disorder: the NICE guideline on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

6. Kupka R, Goossens P, van Bendegem M, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP); 2015. Accessed August 10, 2020. http://www.nvvp.net/stream/richtlijn-bipolaire-stoornissen-2015

7. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087‐1206. doi:10.1177/0004867415617657

8. Nederlof M, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG, et al. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: an international survey. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0120-1

9. Leo RJ, Sharma M, Chrostowski DA. A case of lithium-induced symptomatic hypercalcemia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09l00917. doi:10.4088/PCC.09l00917yel

10. McHenry CR, Lee K. Lithium therapy and disorders of the parathyroid glands. Endocr Pract. 1996;2(2):103-109. doi:10.4158/EP.2.2.103

11. Stahl SM. The prescribers guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

12. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D. Variations of serum lithium concentrations correlated with the phases of manic-depressive psychosis. Agressologie. 1978;19(D):219-222.

13. Rittmannsberger H, Malsiner-Walli G. Mood-dependent changes of serum lithium concentration in a rapid cycling patient maintained on stable doses of lithium carbonate. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(3):333-337. doi:10.1111/bdi.12066

14. Hochman E, Weizman A, Valevski A, et al. Association between bipolar episodes and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):781-789. doi:10.1111/bdi.12248

15. Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377

16. Boltan DD, Fenves AZ. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(3):261-263. doi:10.1080/08998280.2008.11928407

17. Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

18. Tighe SK, Mahon PB, Potash JB. Predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):209-226. doi:10.1177/2040622311399173

19. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8

20. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of co-therapy vs monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;115(1):12-20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x

21. Nolen WA, Licht RW, Young AH, et al; ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):394-409. doi:10.1111/bdi.12805

22. Maj M, Starace F, Nolfe G, et al. Minimum plasma lithium levels required for effective prophylaxis in DSM III bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):420-423. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017280

23. Gupta S, Kripalani M, Khastgir U, et al. Management of the renal adverse effects of lithium. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2013;19(6):457-466. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.112.010306

24. Gitlin M. Lithium and the kidney: an updated review. Drug Saf. 1999;20(3):231-243. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920030-00004

25. Jefferson JW. A clinician’s guide to monitoring kidney function in lithium-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1153-1157. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05917yel

26. Shah VC, Kayathi P, Singh G, et al. Enhance your understanding of lithium neurotoxicity. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3):10.4088/PCC.14l01767. doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01767

27. Netto I, Phutane VH. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01197

28. Mohandas E, Rajmohan V. Lithium use in special populations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):211-218. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37325

29. Gupta S, Khastgir U. Drug information update. Lithium and chronic kidney disease: debates and dilemmas. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):216-220. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.054031

30. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0322

31. Timmer RT, Sands JM. Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(3):666-674.

32. Demers RG, Heninger GR. Sodium intake and lithium treatment in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128(1):100-104. doi:10.1176/ajp.128.1.100

33. Hedya SA, Avula A, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.

1. Tondo L, Alda M, Bauer M, et al. Clinical use of lithium salts: guide for users and prescribers. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2019;7(1):16. doi:10.1186/s40345-019-0151-2

2. Azab AN, Shnaider A, Osher Y, et al. Lithium nephrotoxicity. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2015;3(1):28. doi:10.1186/s40345-015-0028-y

3. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with bipolar disorder (revision). Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1-50.

4. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) collaborative update of CANMAT guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder: update 2013. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15:1‐44. doi:10.1111/bdi.12025

5. National Collaborating Center for Mental Health (UK). Bipolar disorder: the NICE guideline on the assessment and management of bipolar disorder in adults, children and young people in primary and secondary care. The British Psychological Society and The Royal College of Psychiatrists; 2014.

6. Kupka R, Goossens P, van Bendegem M, et al. Multidisciplinaire richtlijn bipolaire stoornissen. Nederlandse Vereniging voor Psychiatrie (NVvP); 2015. Accessed August 10, 2020. http://www.nvvp.net/stream/richtlijn-bipolaire-stoornissen-2015

7. Malhi GS, Bassett D, Boyce P, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2015;49:1087‐1206. doi:10.1177/0004867415617657

8. Nederlof M, Heerdink ER, Egberts ACG, et al. Monitoring of patients treated with lithium for bipolar disorder: an international survey. Int J Bipolar Disord. 2018;6(1):12. doi:10.1186/s40345-018-0120-1

9. Leo RJ, Sharma M, Chrostowski DA. A case of lithium-induced symptomatic hypercalcemia. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09l00917. doi:10.4088/PCC.09l00917yel

10. McHenry CR, Lee K. Lithium therapy and disorders of the parathyroid glands. Endocr Pract. 1996;2(2):103-109. doi:10.4158/EP.2.2.103

11. Stahl SM. The prescribers guide: Stahl’s essential psychopharmacology. 6th ed. Cambridge University Press; 2017.

12. Kukopulos A, Reginaldi D. Variations of serum lithium concentrations correlated with the phases of manic-depressive psychosis. Agressologie. 1978;19(D):219-222.

13. Rittmannsberger H, Malsiner-Walli G. Mood-dependent changes of serum lithium concentration in a rapid cycling patient maintained on stable doses of lithium carbonate. Bipolar Disord. 2013;15(3):333-337. doi:10.1111/bdi.12066

14. Hochman E, Weizman A, Valevski A, et al. Association between bipolar episodes and fluid and electrolyte homeostasis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Bipolar Disord. 2014;16(8):781-789. doi:10.1111/bdi.12248

15. Volkmann C, Bschor T, Köhler S. Lithium treatment over the lifespan in bipolar disorders. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:377. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00377

16. Boltan DD, Fenves AZ. Effectiveness of normal saline diuresis in treating lithium overdose. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent). 2008;21(3):261-263. doi:10.1080/08998280.2008.11928407

17. Sadock BJ, Saddock VA, Ruiz P. Kaplan and Sadock’s synopsis of psychiatry. 11th ed. Wolters Kluwer; 2014.

18. Tighe SK, Mahon PB, Potash JB. Predictors of lithium response in bipolar disorder. Ther Adv Chronic Dis. 2011;2(3):209-226. doi:10.1177/2040622311399173

19. Cipriani A, Barbui C, Salanti G, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antimanic drugs in acute mania: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;378(9799):1306-1315. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60873-8

20. Smith LA, Cornelius V, Tacchi MJ, et al. Acute bipolar mania: a systematic review and meta-analysis of co-therapy vs monotherapy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;115(1):12-20. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00912.x

21. Nolen WA, Licht RW, Young AH, et al; ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on the treatment with lithium. What is the optimal serum level for lithium in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder? A systematic review and recommendations from the ISBD/IGSLI Task Force on treatment with lithium. Bipolar Disord. 2019;21(5):394-409. doi:10.1111/bdi.12805

22. Maj M, Starace F, Nolfe G, et al. Minimum plasma lithium levels required for effective prophylaxis in DSM III bipolar disorder: a prospective study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1986;19(6):420-423. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1017280

23. Gupta S, Kripalani M, Khastgir U, et al. Management of the renal adverse effects of lithium. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2013;19(6):457-466. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.112.010306

24. Gitlin M. Lithium and the kidney: an updated review. Drug Saf. 1999;20(3):231-243. doi:10.2165/00002018-199920030-00004

25. Jefferson JW. A clinician’s guide to monitoring kidney function in lithium-treated patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(9):1153-1157. doi:10.4088/JCP.09m05917yel

26. Shah VC, Kayathi P, Singh G, et al. Enhance your understanding of lithium neurotoxicity. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2015;17(3):10.4088/PCC.14l01767. doi:10.4088/PCC.14l01767

27. Netto I, Phutane VH. Reversible lithium neurotoxicity: review of the literature. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(1):PCC.11r01197. doi:10.4088/PCC.11r01197

28. Mohandas E, Rajmohan V. Lithium use in special populations. Indian J Psychiatry. 2007;49(3):211-218. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.37325

29. Gupta S, Khastgir U. Drug information update. Lithium and chronic kidney disease: debates and dilemmas. BJPsych Bull. 2017;41(4):216-220. doi:10.1192/pb.bp.116.054031

30. Post RM. Preventing the malignant transformation of bipolar disorder. JAMA. 2018;319(12):1197-1198. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.0322

31. Timmer RT, Sands JM. Lithium intoxication. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10(3):666-674.

32. Demers RG, Heninger GR. Sodium intake and lithium treatment in mania. Am J Psychiatry. 1971;128(1):100-104. doi:10.1176/ajp.128.1.100

33. Hedya SA, Avula A, Swoboda HD. Lithium toxicity. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2020.