User login

Decreasing Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria: An Interprofessional Approach to Antibiotic Stewardship

From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) denotes asymptomatic carriage of bacteria within the urinary tract and does not require treatment in most patient populations. Unnecessary antimicrobial treatment has several consequences, including promotion of antimicrobial resistance, potential for medication adverse effects, and risk for Clostridiodes difficile infection. The aim of this quality improvement effort was to decrease both the unnecessary ordering of urine culture studies and unnecessary treatment of ASB.

- Methods: This is a single-center study of patients who received care on 3 internal medicine units at a large, academic medical center. We sought to determine the impact of information technology and educational interventions to decrease both inappropriate urine culture ordering and treatment of ASB. Data from included patients were collected over 3 1-month time periods: baseline, post-information technology intervention, and post-educational intervention.

- Results: There was a reduction in the percentage of patients who received antibiotics for ASB in the post-education intervention period as compared to baseline (35% vs 42%). The proportion of total urine cultures ordered by internal medicine clinicians did not change after an information technology intervention to redesign the computerized physician order entry screen for urine cultures.

- Conclusion: Educational interventions are effective ways to reduce rates of inappropriate treatment of ASB in patients admitted to internal medicine services.

Keywords: asymptomatic bacteriuria, UTI, information technology, education, quality.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is a common condition in which bacteria are recovered from a urine culture (UC) in patients without symptoms suggestive of urinary tract infection (UTI), with no pathologic consequences to most patients who are not treated.1,2 Patients with ASB do not exhibit symptoms of a UTI such as dysuria, increased frequency of urination, increased urgency, suprapubic tenderness, or costovertebral pain. Treatment with antibiotics is not indicated for most patients with ASB.1,3 According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), screening for bacteriuria and treatment for positive results is only indicated during pregnancy and prior to urologic procedures with anticipated breach of the mucosal lining.1

An estimated 20% to 52% of patients in hospital settings receive inappropriate treatment with antibiotics for ASB.4 Unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics has several negative consequences, including increased rates of antibiotic resistance, Clostridioides difficile infection, and medication adverse events, as well as increased health care costs.2,5 Antimicrobial stewardship programs to improve judicious use of antimicrobials are paramount to reducing these consequences, and their importance is heightened with recent requirements for antimicrobial stewardship put forth by The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.6,7

A previous review of UC and antimicrobial use in patients for purposes of quality improvement at our institution over a 2-month period showed that of 59 patients with positive UCs, 47 patients (80%) did not have documented symptoms of a UTI. Of these 47 patients with ASB, 29 (61.7%) received antimicrobial treatment unnecessarily (unpublished data). We convened a group of clinicians and nonclinicians representing the areas of infectious disease, pharmacy, microbiology, statistics, and hospital internal medicine (IM) to examine the unnecessary treatment of ASB in our institution. Our objective was to address 2 antimicrobial stewardship issues: inappropriate UC ordering and unnecessary use of antibiotics to treat ASB. Our aim was to reduce the inappropriate ordering of UCs and to reduce treatment of ASB.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted on 3 IM nursing units with a total of 83 beds at a large tertiary care academic medical center in the midwestern United States, and was approved by the organization’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included all non-pregnant patients aged 18 years or older who received care from an IM primary service. These patients were admitted directly to an IM team through the emergency department (ED) or transferred to an IM team after an initial stay in the intensive care unit.

Data Source

Microbiology laboratory reports generated from the electronic health record were used to identify all patients with a collected UC sample who received care from an IM service prior to discharge. Urine samples were collected by midstream catch or catheterization. Data on urine Gram stain and urine dipstick were not included. Henceforth, the phrase “urine culture order” indicates that a UC was both ordered and performed. Data reports were generated for the month of August 2016 to determine the baseline number of UCs ordered. Charts of patients with positive UCs were reviewed to determine if antibiotics were started for the positive UC and whether the patient had signs or symptoms consistent with a UTI. If antibiotics were started in the absence of signs or symptoms to support a UTI, the patient was determined to have been unnecessarily treated for ASB. Reports were then generated for the month after each intervention was implemented, with the same chart review undertaken for positive UCs. Bacteriuria was defined in our study as the presence of microbial growth greater than 10,000 CFU/mL in UC.

Interventions

Initial analysis by our study group determined that lack of electronic clinical decision support (CDS) at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs were the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs, respectively. We reviewed the work of other groups who reported interventions to decrease treatment of ASB, ranging from educational presentations to pocket cards and treatment algorithms.8-13 We hypothesized that there would be a decrease in UC orders with CDS embedded in the computerized order entry screen, and that we would decrease unnecessary treatment of positive UCs by educating clinicians on indications for appropriate antibiotic prescribing in the setting of a positive UC.

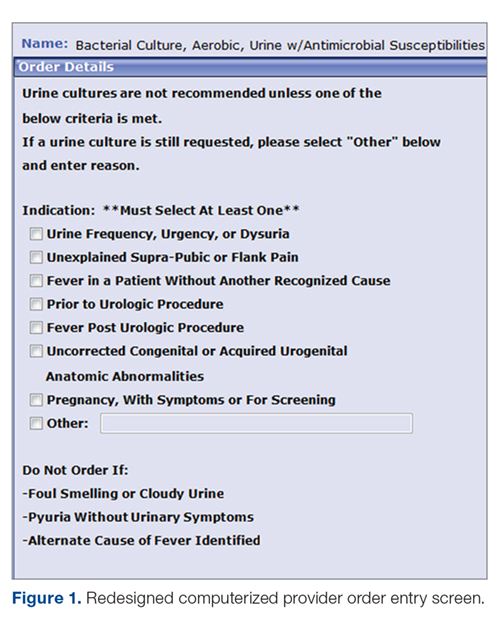

Information technology intervention. The first intervention implemented involved redesign of the UC ordering screen in the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system. This intervention went live hospital-wide, including the IM floors, intensive care units, and all other areas except the ED, on February 1, 2017 (Figure 1). The ordering screen required the prescriber to select from a list of appropriate indications for ordering a UC, including urine frequency, urgency, or dysuria; unexplained suprapubic or flank pain; fever in patients without another recognized cause; screening obtained prior to urologic procedure; or screening during pregnancy. An additional message advised prescribers to avoid ordering the culture if the patient had malodorous or cloudy urine, pyuria without urinary symptoms, or had an alternative cause of fever. Before we implemented the information technology (IT) intervention, there had been no specific point-of-care guidance on UC ordering.

Educational intervention. The second intervention, driven by clinical pharmacists, involved active and passive education of prescribers specifically designed to address unnecessary treatment of ASB. The IT intervention with CDS for UC ordering remained live. Presentations designed by the study group summarizing the appropriate indications for ordering a UC, distinguishing ASB from UTI, and discouraging treatment of ASB were delivered via a variety of routes by clinical pharmacists to nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, medical residents, and staff physicians providing care to patients on the 3 IM units over a 1-month period in March 2017. The presentations contained the same basic content, but the information was delivered to target each specific audience group.

Medical residents received a 10-minute live presentation during a conference. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and staff physicians received a presentation via email, and highlights of the presentation were delivered by clinical pharmacists at their respective monthly group meetings. A handout was presented to nursing staff at nursing huddles, and presentation slides were distributed by email. Educational posters were posted in the medical resident workrooms, nursing breakrooms, and staff bathrooms on the units.

Outcome Measurements

The endpoints of interest were the percentage of patients with positive UCs unnecessarily treated for ASB before and after each intervention and the number of UCs ordered at baseline and after implementation of each intervention. Counterbalance measures assessed included the incidence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or urosepsis within 7 days of positive UC for patients who did not receive antibiotic treatment for ASB.

Results

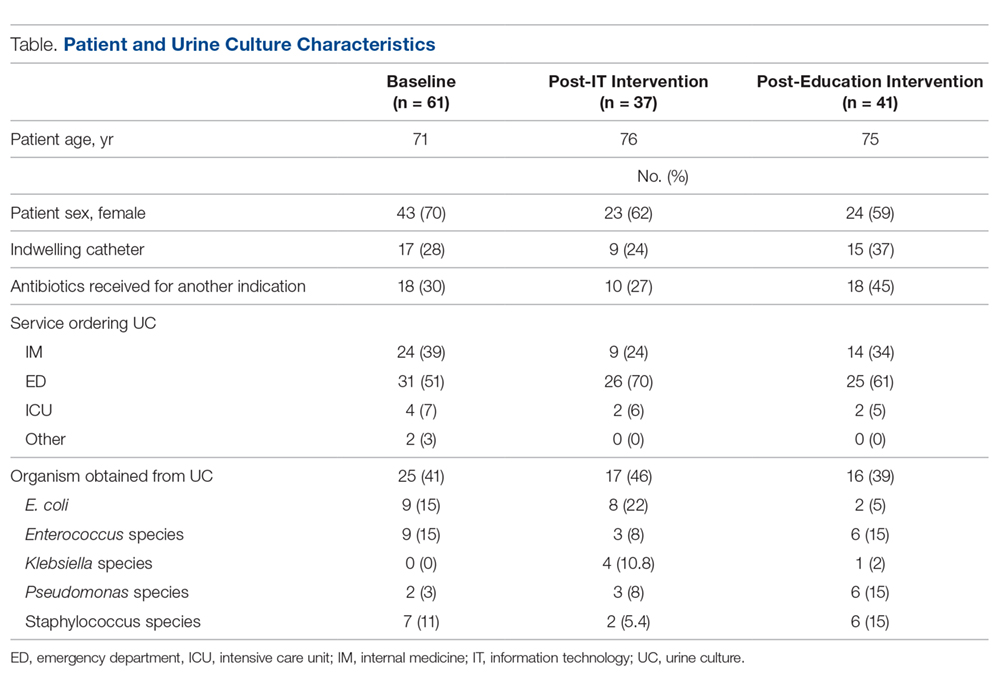

Data from a total of 270 cultures were examined from IM nursing units. A total of 117 UCs were ordered during the baseline period before interventions were implemented. For a period of 1 month following activation of the IT intervention, 73 UCs were ordered. For a period of 1 month following the educational interventions, 80 UCs were ordered. Of these, 61 (52%) UCs were positive at baseline, 37 (51%) after the IT intervention, and 41 (51%) after the educational intervention. Patient characteristics were similar between the 3 groups (Table); 64.7% of patients were female in their early to mid-seventies. The majority of UCs were ordered by providers in the ED in all 3 periods examined (51%-70%). The percentage of patients who received antibiotics prior to UC for another indication (including bacteriuria) in the baseline, post-IT intervention, and post-education intervention groups were 30%, 27%, and 45%, respectively.

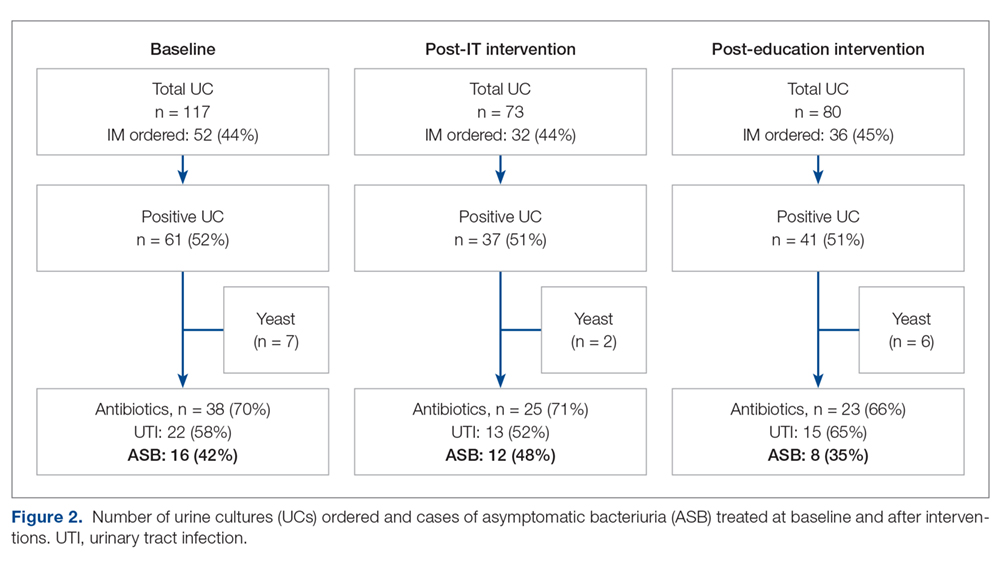

The study outcomes are summarized in Figure 2. Among patients with positive cultures, there was not a reduction in inappropriate treatment of ASB compared to baseline after the IT intervention (48% vs 42%). Following the education intervention, there was a reduction in unnecessary ASB treatment as compared both to baseline (35% vs 42%) and to post-IT intervention (35% vs 48%). There was no difference between the 3 study periods in the percentage of total UCs ordered by IM clinicians. The counterbalance measure showed that 1 patient who did not receive antibiotics within 7 days of a positive UC developed pyelonephritis, UTI, or sepsis due to a UTI in each intervention group.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the role of multimodal interventions in antimicrobial stewardship and add to the growing body of evidence supporting the work of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Our multidisciplinary study group and multipronged intervention follow recent guideline recommendations for antimicrobial stewardship program interventions against unnecessary treatment of ASB.14 Initial analysis by our study group determined lack of CDS at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs as the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs in our local practice culture. The IT component of our intervention was intended to provide CDS for ordering UCs, and the education component focused on informing clinicians’ treatment decisions for positive UCs.

It has been suggested that the type of stewardship intervention that is most effective fits the specific needs and resources of an institution.14,15 And although the IDSA does not recommend education as a stand-alone intervention,16 we found it to be an effective intervention for our clinicians in our work environment. However, since the CPOE guidance was in place during the educational study periods, it is possible that the effect was due to a combination of these 2 approaches. Our pre-intervention ASB treatment rates were consistent with a recent meta-analysis in which the rate of inappropriate treatment of ASB was 45%.17 This meta-analysis found educational and organizational interventions led to a mean absolute risk reduction of 33%. After the education intervention, we saw a 7% decrease in unnecessary treatment of ASB compared to baseline, and a 13% decrease compared to the month just prior to the educational intervention.

Lessons learned from our work included how clear review of local processes can inform quality improvement interventions. For instance, we initially hypothesized that IM clinicians would benefit from point-of-care CDS guidance, but such guidance used alone without educational interventions was not supported by the results. We also determined that the majority of UCs from patients on general medicine units were ordered by ED providers. This revealed an opportunity to implement similar interventions in the ED, as this was the initial point of contact for many of these patients.

As with any clinical intervention, the anticipated benefits should be weighed against potential harm. Using counterbalance measures, we found there was minimal risk in the occurrence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or sepsis if clinicians avoided treating ASB. This finding is consistent with IDSA guideline recommendations and other studies that suggest that withholding treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria does not lead to worse outcomes.1

This study has several limitations. Data were obtained through review of the electronic health record and therefore documentation may be incomplete. Also, antimicrobials for empiric coverage or treatment for other infections (eg, pneumonia, sepsis) may have confounded our results, as empirical antimicrobials were given to 27% to 45% of patients prior to UC. This was a quality improvement project carried out over defined time intervals, and thus our sample size was limited and not adequately powered to show statistical significance. Additionally, given the bundling of interventions, it is difficult to determine the impact of each intervention independently. Although CDS for UC ordering may not have influenced ordering, it is possible that the IT intervention raised awareness of ASB and influenced treatment practices.

Conclusion

Our work supports the principles of antibiotic stewardship as brought forth by IDSA.16 This work was the effort of a multidisciplinary team, which aligns with recommendations by Daniel and colleagues, published after our study had ended, for reducing overtreatment of ASB.14 Additionally, our study results provided valuable information for our institution. Although improvements in management of ASB were modest, the success of provider education and identification of other work areas and clinicians to target for future intervention were helpful in consideration of further studies. This work will also aid us in developing an expected effect size for future studies. We plan to provide ongoing education for IM providers as well as education in the ED to target providers who make first contact with patients admitted to inpatient services. In addition, the CPOE UC ordering screen message will continue to be used hospital-wide and will be expanded to the ED ordering system. Our interventions, experiences, and challenges may be used by other institutions to design effective antimicrobial stewardship interventions directed towards reducing rates of inappropriate ASB treatment.

Corresponding author: Prasanna P. Narayanan, PharmD, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; narayanan.prasanna@mayo.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83–75.

2. Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an antimicrobial stewardship approach for urinary catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1120-1127.

3. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309-332.

4. Trautner BW. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: when the treatment is worse than the disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;9:85-93.

5. Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, et al. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c2096.

6. The Joint Commission. Prepublication Requirements: New antimicrobial stewardship standard. Jun 22, 2016. www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/HAP-CAH_Antimicrobial_Prepub.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2019.

7. Federal Register. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Hospital and Critical Access Hospital (CAH) Changes to Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. June 16, 2016. CMS-3295-P

8. Hartley SE, Kuhn L, Valley S, et al. Evaluating a hospitalist-based intervention to decrease unnecessary antimicrobial use in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1044-1051.

9. Pavese P, Saurel N, Labarere J, et al. Does an educational session with an infectious diseases physician reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotic therapy for inpatients with positive urine culture results? A controlled before-and-after study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:596-599.

10. Kelley D, Aaronson P, Poon E, et al. Evaluation of an antimicrobial stewardship approach to minimize overuse of antibiotics in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:193-195.

11. Chowdhury F, Sarkar K, Branche A, et al. Preventing the inappropriate treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria at a community teaching hospital. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2012;2.

12. Bonnal C, Baune B, Mion M, et al. Bacteriuria in a geriatric hospital: impact of an antibiotic improvement program. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:605-609.

13. Linares LA, Thornton DJ, Strymish J, et al. Electronic memorandum decreases unnecessary antimicrobial use for asymptomatic bacteriuria and culture-negative pyuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:644-648.

14. Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, et al. An implementation guide to reducing overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:271-276.

15. Redwood R, Knobloch MJ, Pellegrini DC, et al. Reducing unnecessary culturing: a systems approach to evaluating urine culture ordering and collection practices among nurses in two acute care settings. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:4.

16. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e51–e7.

17. Flokas ME, Andreatos N, Alevizakos M, et al. Inappropriate management of asymptomatic patients with positive urine cultures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:1-10.

From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) denotes asymptomatic carriage of bacteria within the urinary tract and does not require treatment in most patient populations. Unnecessary antimicrobial treatment has several consequences, including promotion of antimicrobial resistance, potential for medication adverse effects, and risk for Clostridiodes difficile infection. The aim of this quality improvement effort was to decrease both the unnecessary ordering of urine culture studies and unnecessary treatment of ASB.

- Methods: This is a single-center study of patients who received care on 3 internal medicine units at a large, academic medical center. We sought to determine the impact of information technology and educational interventions to decrease both inappropriate urine culture ordering and treatment of ASB. Data from included patients were collected over 3 1-month time periods: baseline, post-information technology intervention, and post-educational intervention.

- Results: There was a reduction in the percentage of patients who received antibiotics for ASB in the post-education intervention period as compared to baseline (35% vs 42%). The proportion of total urine cultures ordered by internal medicine clinicians did not change after an information technology intervention to redesign the computerized physician order entry screen for urine cultures.

- Conclusion: Educational interventions are effective ways to reduce rates of inappropriate treatment of ASB in patients admitted to internal medicine services.

Keywords: asymptomatic bacteriuria, UTI, information technology, education, quality.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is a common condition in which bacteria are recovered from a urine culture (UC) in patients without symptoms suggestive of urinary tract infection (UTI), with no pathologic consequences to most patients who are not treated.1,2 Patients with ASB do not exhibit symptoms of a UTI such as dysuria, increased frequency of urination, increased urgency, suprapubic tenderness, or costovertebral pain. Treatment with antibiotics is not indicated for most patients with ASB.1,3 According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), screening for bacteriuria and treatment for positive results is only indicated during pregnancy and prior to urologic procedures with anticipated breach of the mucosal lining.1

An estimated 20% to 52% of patients in hospital settings receive inappropriate treatment with antibiotics for ASB.4 Unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics has several negative consequences, including increased rates of antibiotic resistance, Clostridioides difficile infection, and medication adverse events, as well as increased health care costs.2,5 Antimicrobial stewardship programs to improve judicious use of antimicrobials are paramount to reducing these consequences, and their importance is heightened with recent requirements for antimicrobial stewardship put forth by The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.6,7

A previous review of UC and antimicrobial use in patients for purposes of quality improvement at our institution over a 2-month period showed that of 59 patients with positive UCs, 47 patients (80%) did not have documented symptoms of a UTI. Of these 47 patients with ASB, 29 (61.7%) received antimicrobial treatment unnecessarily (unpublished data). We convened a group of clinicians and nonclinicians representing the areas of infectious disease, pharmacy, microbiology, statistics, and hospital internal medicine (IM) to examine the unnecessary treatment of ASB in our institution. Our objective was to address 2 antimicrobial stewardship issues: inappropriate UC ordering and unnecessary use of antibiotics to treat ASB. Our aim was to reduce the inappropriate ordering of UCs and to reduce treatment of ASB.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted on 3 IM nursing units with a total of 83 beds at a large tertiary care academic medical center in the midwestern United States, and was approved by the organization’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included all non-pregnant patients aged 18 years or older who received care from an IM primary service. These patients were admitted directly to an IM team through the emergency department (ED) or transferred to an IM team after an initial stay in the intensive care unit.

Data Source

Microbiology laboratory reports generated from the electronic health record were used to identify all patients with a collected UC sample who received care from an IM service prior to discharge. Urine samples were collected by midstream catch or catheterization. Data on urine Gram stain and urine dipstick were not included. Henceforth, the phrase “urine culture order” indicates that a UC was both ordered and performed. Data reports were generated for the month of August 2016 to determine the baseline number of UCs ordered. Charts of patients with positive UCs were reviewed to determine if antibiotics were started for the positive UC and whether the patient had signs or symptoms consistent with a UTI. If antibiotics were started in the absence of signs or symptoms to support a UTI, the patient was determined to have been unnecessarily treated for ASB. Reports were then generated for the month after each intervention was implemented, with the same chart review undertaken for positive UCs. Bacteriuria was defined in our study as the presence of microbial growth greater than 10,000 CFU/mL in UC.

Interventions

Initial analysis by our study group determined that lack of electronic clinical decision support (CDS) at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs were the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs, respectively. We reviewed the work of other groups who reported interventions to decrease treatment of ASB, ranging from educational presentations to pocket cards and treatment algorithms.8-13 We hypothesized that there would be a decrease in UC orders with CDS embedded in the computerized order entry screen, and that we would decrease unnecessary treatment of positive UCs by educating clinicians on indications for appropriate antibiotic prescribing in the setting of a positive UC.

Information technology intervention. The first intervention implemented involved redesign of the UC ordering screen in the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system. This intervention went live hospital-wide, including the IM floors, intensive care units, and all other areas except the ED, on February 1, 2017 (Figure 1). The ordering screen required the prescriber to select from a list of appropriate indications for ordering a UC, including urine frequency, urgency, or dysuria; unexplained suprapubic or flank pain; fever in patients without another recognized cause; screening obtained prior to urologic procedure; or screening during pregnancy. An additional message advised prescribers to avoid ordering the culture if the patient had malodorous or cloudy urine, pyuria without urinary symptoms, or had an alternative cause of fever. Before we implemented the information technology (IT) intervention, there had been no specific point-of-care guidance on UC ordering.

Educational intervention. The second intervention, driven by clinical pharmacists, involved active and passive education of prescribers specifically designed to address unnecessary treatment of ASB. The IT intervention with CDS for UC ordering remained live. Presentations designed by the study group summarizing the appropriate indications for ordering a UC, distinguishing ASB from UTI, and discouraging treatment of ASB were delivered via a variety of routes by clinical pharmacists to nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, medical residents, and staff physicians providing care to patients on the 3 IM units over a 1-month period in March 2017. The presentations contained the same basic content, but the information was delivered to target each specific audience group.

Medical residents received a 10-minute live presentation during a conference. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and staff physicians received a presentation via email, and highlights of the presentation were delivered by clinical pharmacists at their respective monthly group meetings. A handout was presented to nursing staff at nursing huddles, and presentation slides were distributed by email. Educational posters were posted in the medical resident workrooms, nursing breakrooms, and staff bathrooms on the units.

Outcome Measurements

The endpoints of interest were the percentage of patients with positive UCs unnecessarily treated for ASB before and after each intervention and the number of UCs ordered at baseline and after implementation of each intervention. Counterbalance measures assessed included the incidence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or urosepsis within 7 days of positive UC for patients who did not receive antibiotic treatment for ASB.

Results

Data from a total of 270 cultures were examined from IM nursing units. A total of 117 UCs were ordered during the baseline period before interventions were implemented. For a period of 1 month following activation of the IT intervention, 73 UCs were ordered. For a period of 1 month following the educational interventions, 80 UCs were ordered. Of these, 61 (52%) UCs were positive at baseline, 37 (51%) after the IT intervention, and 41 (51%) after the educational intervention. Patient characteristics were similar between the 3 groups (Table); 64.7% of patients were female in their early to mid-seventies. The majority of UCs were ordered by providers in the ED in all 3 periods examined (51%-70%). The percentage of patients who received antibiotics prior to UC for another indication (including bacteriuria) in the baseline, post-IT intervention, and post-education intervention groups were 30%, 27%, and 45%, respectively.

The study outcomes are summarized in Figure 2. Among patients with positive cultures, there was not a reduction in inappropriate treatment of ASB compared to baseline after the IT intervention (48% vs 42%). Following the education intervention, there was a reduction in unnecessary ASB treatment as compared both to baseline (35% vs 42%) and to post-IT intervention (35% vs 48%). There was no difference between the 3 study periods in the percentage of total UCs ordered by IM clinicians. The counterbalance measure showed that 1 patient who did not receive antibiotics within 7 days of a positive UC developed pyelonephritis, UTI, or sepsis due to a UTI in each intervention group.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the role of multimodal interventions in antimicrobial stewardship and add to the growing body of evidence supporting the work of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Our multidisciplinary study group and multipronged intervention follow recent guideline recommendations for antimicrobial stewardship program interventions against unnecessary treatment of ASB.14 Initial analysis by our study group determined lack of CDS at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs as the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs in our local practice culture. The IT component of our intervention was intended to provide CDS for ordering UCs, and the education component focused on informing clinicians’ treatment decisions for positive UCs.

It has been suggested that the type of stewardship intervention that is most effective fits the specific needs and resources of an institution.14,15 And although the IDSA does not recommend education as a stand-alone intervention,16 we found it to be an effective intervention for our clinicians in our work environment. However, since the CPOE guidance was in place during the educational study periods, it is possible that the effect was due to a combination of these 2 approaches. Our pre-intervention ASB treatment rates were consistent with a recent meta-analysis in which the rate of inappropriate treatment of ASB was 45%.17 This meta-analysis found educational and organizational interventions led to a mean absolute risk reduction of 33%. After the education intervention, we saw a 7% decrease in unnecessary treatment of ASB compared to baseline, and a 13% decrease compared to the month just prior to the educational intervention.

Lessons learned from our work included how clear review of local processes can inform quality improvement interventions. For instance, we initially hypothesized that IM clinicians would benefit from point-of-care CDS guidance, but such guidance used alone without educational interventions was not supported by the results. We also determined that the majority of UCs from patients on general medicine units were ordered by ED providers. This revealed an opportunity to implement similar interventions in the ED, as this was the initial point of contact for many of these patients.

As with any clinical intervention, the anticipated benefits should be weighed against potential harm. Using counterbalance measures, we found there was minimal risk in the occurrence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or sepsis if clinicians avoided treating ASB. This finding is consistent with IDSA guideline recommendations and other studies that suggest that withholding treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria does not lead to worse outcomes.1

This study has several limitations. Data were obtained through review of the electronic health record and therefore documentation may be incomplete. Also, antimicrobials for empiric coverage or treatment for other infections (eg, pneumonia, sepsis) may have confounded our results, as empirical antimicrobials were given to 27% to 45% of patients prior to UC. This was a quality improvement project carried out over defined time intervals, and thus our sample size was limited and not adequately powered to show statistical significance. Additionally, given the bundling of interventions, it is difficult to determine the impact of each intervention independently. Although CDS for UC ordering may not have influenced ordering, it is possible that the IT intervention raised awareness of ASB and influenced treatment practices.

Conclusion

Our work supports the principles of antibiotic stewardship as brought forth by IDSA.16 This work was the effort of a multidisciplinary team, which aligns with recommendations by Daniel and colleagues, published after our study had ended, for reducing overtreatment of ASB.14 Additionally, our study results provided valuable information for our institution. Although improvements in management of ASB were modest, the success of provider education and identification of other work areas and clinicians to target for future intervention were helpful in consideration of further studies. This work will also aid us in developing an expected effect size for future studies. We plan to provide ongoing education for IM providers as well as education in the ED to target providers who make first contact with patients admitted to inpatient services. In addition, the CPOE UC ordering screen message will continue to be used hospital-wide and will be expanded to the ED ordering system. Our interventions, experiences, and challenges may be used by other institutions to design effective antimicrobial stewardship interventions directed towards reducing rates of inappropriate ASB treatment.

Corresponding author: Prasanna P. Narayanan, PharmD, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; narayanan.prasanna@mayo.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) denotes asymptomatic carriage of bacteria within the urinary tract and does not require treatment in most patient populations. Unnecessary antimicrobial treatment has several consequences, including promotion of antimicrobial resistance, potential for medication adverse effects, and risk for Clostridiodes difficile infection. The aim of this quality improvement effort was to decrease both the unnecessary ordering of urine culture studies and unnecessary treatment of ASB.

- Methods: This is a single-center study of patients who received care on 3 internal medicine units at a large, academic medical center. We sought to determine the impact of information technology and educational interventions to decrease both inappropriate urine culture ordering and treatment of ASB. Data from included patients were collected over 3 1-month time periods: baseline, post-information technology intervention, and post-educational intervention.

- Results: There was a reduction in the percentage of patients who received antibiotics for ASB in the post-education intervention period as compared to baseline (35% vs 42%). The proportion of total urine cultures ordered by internal medicine clinicians did not change after an information technology intervention to redesign the computerized physician order entry screen for urine cultures.

- Conclusion: Educational interventions are effective ways to reduce rates of inappropriate treatment of ASB in patients admitted to internal medicine services.

Keywords: asymptomatic bacteriuria, UTI, information technology, education, quality.

Asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) is a common condition in which bacteria are recovered from a urine culture (UC) in patients without symptoms suggestive of urinary tract infection (UTI), with no pathologic consequences to most patients who are not treated.1,2 Patients with ASB do not exhibit symptoms of a UTI such as dysuria, increased frequency of urination, increased urgency, suprapubic tenderness, or costovertebral pain. Treatment with antibiotics is not indicated for most patients with ASB.1,3 According to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), screening for bacteriuria and treatment for positive results is only indicated during pregnancy and prior to urologic procedures with anticipated breach of the mucosal lining.1

An estimated 20% to 52% of patients in hospital settings receive inappropriate treatment with antibiotics for ASB.4 Unnecessary prescribing of antibiotics has several negative consequences, including increased rates of antibiotic resistance, Clostridioides difficile infection, and medication adverse events, as well as increased health care costs.2,5 Antimicrobial stewardship programs to improve judicious use of antimicrobials are paramount to reducing these consequences, and their importance is heightened with recent requirements for antimicrobial stewardship put forth by The Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.6,7

A previous review of UC and antimicrobial use in patients for purposes of quality improvement at our institution over a 2-month period showed that of 59 patients with positive UCs, 47 patients (80%) did not have documented symptoms of a UTI. Of these 47 patients with ASB, 29 (61.7%) received antimicrobial treatment unnecessarily (unpublished data). We convened a group of clinicians and nonclinicians representing the areas of infectious disease, pharmacy, microbiology, statistics, and hospital internal medicine (IM) to examine the unnecessary treatment of ASB in our institution. Our objective was to address 2 antimicrobial stewardship issues: inappropriate UC ordering and unnecessary use of antibiotics to treat ASB. Our aim was to reduce the inappropriate ordering of UCs and to reduce treatment of ASB.

Methods

Setting

The study was conducted on 3 IM nursing units with a total of 83 beds at a large tertiary care academic medical center in the midwestern United States, and was approved by the organization’s Institutional Review Board.

Participants

We included all non-pregnant patients aged 18 years or older who received care from an IM primary service. These patients were admitted directly to an IM team through the emergency department (ED) or transferred to an IM team after an initial stay in the intensive care unit.

Data Source

Microbiology laboratory reports generated from the electronic health record were used to identify all patients with a collected UC sample who received care from an IM service prior to discharge. Urine samples were collected by midstream catch or catheterization. Data on urine Gram stain and urine dipstick were not included. Henceforth, the phrase “urine culture order” indicates that a UC was both ordered and performed. Data reports were generated for the month of August 2016 to determine the baseline number of UCs ordered. Charts of patients with positive UCs were reviewed to determine if antibiotics were started for the positive UC and whether the patient had signs or symptoms consistent with a UTI. If antibiotics were started in the absence of signs or symptoms to support a UTI, the patient was determined to have been unnecessarily treated for ASB. Reports were then generated for the month after each intervention was implemented, with the same chart review undertaken for positive UCs. Bacteriuria was defined in our study as the presence of microbial growth greater than 10,000 CFU/mL in UC.

Interventions

Initial analysis by our study group determined that lack of electronic clinical decision support (CDS) at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs were the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs, respectively. We reviewed the work of other groups who reported interventions to decrease treatment of ASB, ranging from educational presentations to pocket cards and treatment algorithms.8-13 We hypothesized that there would be a decrease in UC orders with CDS embedded in the computerized order entry screen, and that we would decrease unnecessary treatment of positive UCs by educating clinicians on indications for appropriate antibiotic prescribing in the setting of a positive UC.

Information technology intervention. The first intervention implemented involved redesign of the UC ordering screen in the computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system. This intervention went live hospital-wide, including the IM floors, intensive care units, and all other areas except the ED, on February 1, 2017 (Figure 1). The ordering screen required the prescriber to select from a list of appropriate indications for ordering a UC, including urine frequency, urgency, or dysuria; unexplained suprapubic or flank pain; fever in patients without another recognized cause; screening obtained prior to urologic procedure; or screening during pregnancy. An additional message advised prescribers to avoid ordering the culture if the patient had malodorous or cloudy urine, pyuria without urinary symptoms, or had an alternative cause of fever. Before we implemented the information technology (IT) intervention, there had been no specific point-of-care guidance on UC ordering.

Educational intervention. The second intervention, driven by clinical pharmacists, involved active and passive education of prescribers specifically designed to address unnecessary treatment of ASB. The IT intervention with CDS for UC ordering remained live. Presentations designed by the study group summarizing the appropriate indications for ordering a UC, distinguishing ASB from UTI, and discouraging treatment of ASB were delivered via a variety of routes by clinical pharmacists to nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, pharmacists, medical residents, and staff physicians providing care to patients on the 3 IM units over a 1-month period in March 2017. The presentations contained the same basic content, but the information was delivered to target each specific audience group.

Medical residents received a 10-minute live presentation during a conference. Nurse practitioners, physician assistants, and staff physicians received a presentation via email, and highlights of the presentation were delivered by clinical pharmacists at their respective monthly group meetings. A handout was presented to nursing staff at nursing huddles, and presentation slides were distributed by email. Educational posters were posted in the medical resident workrooms, nursing breakrooms, and staff bathrooms on the units.

Outcome Measurements

The endpoints of interest were the percentage of patients with positive UCs unnecessarily treated for ASB before and after each intervention and the number of UCs ordered at baseline and after implementation of each intervention. Counterbalance measures assessed included the incidence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or urosepsis within 7 days of positive UC for patients who did not receive antibiotic treatment for ASB.

Results

Data from a total of 270 cultures were examined from IM nursing units. A total of 117 UCs were ordered during the baseline period before interventions were implemented. For a period of 1 month following activation of the IT intervention, 73 UCs were ordered. For a period of 1 month following the educational interventions, 80 UCs were ordered. Of these, 61 (52%) UCs were positive at baseline, 37 (51%) after the IT intervention, and 41 (51%) after the educational intervention. Patient characteristics were similar between the 3 groups (Table); 64.7% of patients were female in their early to mid-seventies. The majority of UCs were ordered by providers in the ED in all 3 periods examined (51%-70%). The percentage of patients who received antibiotics prior to UC for another indication (including bacteriuria) in the baseline, post-IT intervention, and post-education intervention groups were 30%, 27%, and 45%, respectively.

The study outcomes are summarized in Figure 2. Among patients with positive cultures, there was not a reduction in inappropriate treatment of ASB compared to baseline after the IT intervention (48% vs 42%). Following the education intervention, there was a reduction in unnecessary ASB treatment as compared both to baseline (35% vs 42%) and to post-IT intervention (35% vs 48%). There was no difference between the 3 study periods in the percentage of total UCs ordered by IM clinicians. The counterbalance measure showed that 1 patient who did not receive antibiotics within 7 days of a positive UC developed pyelonephritis, UTI, or sepsis due to a UTI in each intervention group.

Discussion

The results of this study demonstrate the role of multimodal interventions in antimicrobial stewardship and add to the growing body of evidence supporting the work of antimicrobial stewardship programs. Our multidisciplinary study group and multipronged intervention follow recent guideline recommendations for antimicrobial stewardship program interventions against unnecessary treatment of ASB.14 Initial analysis by our study group determined lack of CDS at the point of care and provider knowledge gaps in interpreting positive UCs as the 2 main contributors to unnecessary UC orders and unnecessary treatment of positive UCs in our local practice culture. The IT component of our intervention was intended to provide CDS for ordering UCs, and the education component focused on informing clinicians’ treatment decisions for positive UCs.

It has been suggested that the type of stewardship intervention that is most effective fits the specific needs and resources of an institution.14,15 And although the IDSA does not recommend education as a stand-alone intervention,16 we found it to be an effective intervention for our clinicians in our work environment. However, since the CPOE guidance was in place during the educational study periods, it is possible that the effect was due to a combination of these 2 approaches. Our pre-intervention ASB treatment rates were consistent with a recent meta-analysis in which the rate of inappropriate treatment of ASB was 45%.17 This meta-analysis found educational and organizational interventions led to a mean absolute risk reduction of 33%. After the education intervention, we saw a 7% decrease in unnecessary treatment of ASB compared to baseline, and a 13% decrease compared to the month just prior to the educational intervention.

Lessons learned from our work included how clear review of local processes can inform quality improvement interventions. For instance, we initially hypothesized that IM clinicians would benefit from point-of-care CDS guidance, but such guidance used alone without educational interventions was not supported by the results. We also determined that the majority of UCs from patients on general medicine units were ordered by ED providers. This revealed an opportunity to implement similar interventions in the ED, as this was the initial point of contact for many of these patients.

As with any clinical intervention, the anticipated benefits should be weighed against potential harm. Using counterbalance measures, we found there was minimal risk in the occurrence of UTI, pyelonephritis, or sepsis if clinicians avoided treating ASB. This finding is consistent with IDSA guideline recommendations and other studies that suggest that withholding treatment for asymptomatic bacteriuria does not lead to worse outcomes.1

This study has several limitations. Data were obtained through review of the electronic health record and therefore documentation may be incomplete. Also, antimicrobials for empiric coverage or treatment for other infections (eg, pneumonia, sepsis) may have confounded our results, as empirical antimicrobials were given to 27% to 45% of patients prior to UC. This was a quality improvement project carried out over defined time intervals, and thus our sample size was limited and not adequately powered to show statistical significance. Additionally, given the bundling of interventions, it is difficult to determine the impact of each intervention independently. Although CDS for UC ordering may not have influenced ordering, it is possible that the IT intervention raised awareness of ASB and influenced treatment practices.

Conclusion

Our work supports the principles of antibiotic stewardship as brought forth by IDSA.16 This work was the effort of a multidisciplinary team, which aligns with recommendations by Daniel and colleagues, published after our study had ended, for reducing overtreatment of ASB.14 Additionally, our study results provided valuable information for our institution. Although improvements in management of ASB were modest, the success of provider education and identification of other work areas and clinicians to target for future intervention were helpful in consideration of further studies. This work will also aid us in developing an expected effect size for future studies. We plan to provide ongoing education for IM providers as well as education in the ED to target providers who make first contact with patients admitted to inpatient services. In addition, the CPOE UC ordering screen message will continue to be used hospital-wide and will be expanded to the ED ordering system. Our interventions, experiences, and challenges may be used by other institutions to design effective antimicrobial stewardship interventions directed towards reducing rates of inappropriate ASB treatment.

Corresponding author: Prasanna P. Narayanan, PharmD, 200 First Street SW, Rochester, MN 55905; narayanan.prasanna@mayo.edu.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83–75.

2. Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an antimicrobial stewardship approach for urinary catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1120-1127.

3. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309-332.

4. Trautner BW. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: when the treatment is worse than the disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;9:85-93.

5. Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, et al. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c2096.

6. The Joint Commission. Prepublication Requirements: New antimicrobial stewardship standard. Jun 22, 2016. www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/HAP-CAH_Antimicrobial_Prepub.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2019.

7. Federal Register. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Hospital and Critical Access Hospital (CAH) Changes to Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. June 16, 2016. CMS-3295-P

8. Hartley SE, Kuhn L, Valley S, et al. Evaluating a hospitalist-based intervention to decrease unnecessary antimicrobial use in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1044-1051.

9. Pavese P, Saurel N, Labarere J, et al. Does an educational session with an infectious diseases physician reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotic therapy for inpatients with positive urine culture results? A controlled before-and-after study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:596-599.

10. Kelley D, Aaronson P, Poon E, et al. Evaluation of an antimicrobial stewardship approach to minimize overuse of antibiotics in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:193-195.

11. Chowdhury F, Sarkar K, Branche A, et al. Preventing the inappropriate treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria at a community teaching hospital. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2012;2.

12. Bonnal C, Baune B, Mion M, et al. Bacteriuria in a geriatric hospital: impact of an antibiotic improvement program. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:605-609.

13. Linares LA, Thornton DJ, Strymish J, et al. Electronic memorandum decreases unnecessary antimicrobial use for asymptomatic bacteriuria and culture-negative pyuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:644-648.

14. Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, et al. An implementation guide to reducing overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:271-276.

15. Redwood R, Knobloch MJ, Pellegrini DC, et al. Reducing unnecessary culturing: a systems approach to evaluating urine culture ordering and collection practices among nurses in two acute care settings. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:4.

16. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e51–e7.

17. Flokas ME, Andreatos N, Alevizakos M, et al. Inappropriate management of asymptomatic patients with positive urine cultures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:1-10.

1. Nicolle LE, Gupta K, Bradley SF, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the management of asymptomatic bacteriuria: 2019 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:e83–75.

2. Trautner BW, Grigoryan L, Petersen NJ, et al. Effectiveness of an antimicrobial stewardship approach for urinary catheter-associated asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175:1120-1127.

3. Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309-332.

4. Trautner BW. Asymptomatic bacteriuria: when the treatment is worse than the disease. Nat Rev Urol. 2011;9:85-93.

5. Costelloe C, Metcalfe C, Lovering A, et al. Effect of antibiotic prescribing in primary care on antimicrobial resistance in individual patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c2096.

6. The Joint Commission. Prepublication Requirements: New antimicrobial stewardship standard. Jun 22, 2016. www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/6/HAP-CAH_Antimicrobial_Prepub.pdf. Accessed January 24, 2019.

7. Federal Register. Medicare and Medicaid Programs; Hospital and Critical Access Hospital (CAH) Changes to Promote Innovation, Flexibility, and Improvement in Patient Care.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. June 16, 2016. CMS-3295-P

8. Hartley SE, Kuhn L, Valley S, et al. Evaluating a hospitalist-based intervention to decrease unnecessary antimicrobial use in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37:1044-1051.

9. Pavese P, Saurel N, Labarere J, et al. Does an educational session with an infectious diseases physician reduce the use of inappropriate antibiotic therapy for inpatients with positive urine culture results? A controlled before-and-after study. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2009;30:596-599.

10. Kelley D, Aaronson P, Poon E, et al. Evaluation of an antimicrobial stewardship approach to minimize overuse of antibiotics in patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:193-195.

11. Chowdhury F, Sarkar K, Branche A, et al. Preventing the inappropriate treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria at a community teaching hospital. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2012;2.

12. Bonnal C, Baune B, Mion M, et al. Bacteriuria in a geriatric hospital: impact of an antibiotic improvement program. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2008;9:605-609.

13. Linares LA, Thornton DJ, Strymish J, et al. Electronic memorandum decreases unnecessary antimicrobial use for asymptomatic bacteriuria and culture-negative pyuria. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2011;32:644-648.

14. Daniel M, Keller S, Mozafarihashjin M, et al. An implementation guide to reducing overtreatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:271-276.

15. Redwood R, Knobloch MJ, Pellegrini DC, et al. Reducing unnecessary culturing: a systems approach to evaluating urine culture ordering and collection practices among nurses in two acute care settings. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control. 2018;7:4.

16. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an antibiotic stewardship program: guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:e51–e7.

17. Flokas ME, Andreatos N, Alevizakos M, et al. Inappropriate management of asymptomatic patients with positive urine cultures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2017;4:1-10.

Using a Medical Interpreter with Persons of Limited English Proficiency

From the Department of Medicine, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN.

Abstract

- Objective: To provide an overview of important aspects of interpreting for medical visits for persons with limited English proficiency (LEP).

- Methods: Literature review.

- Results: When working with persons of LEP, providing a professional medical interpreter will facilitate optimal communication. Interpreters may work in different roles including as a conduit, cultural broker, clarifier, and advocate. In-person and remote (videoconferencing or telephonic) interpreting are available and one may be preferred depending on the medical visit. Clinicians should recognize that patients may have a preference for the interpreter’s gender and dialect and accommodations should be made if possible. Prior to the visit, the provider may want to clarify the goals of the medical encounter with the interpreter as some topics may be viewed differently in certain cultures. When using an interpreter, the provider should maintain eye contact with and direct speech to the patient rather than to the interpreter. The provider should speak clearly, avoid complex terminology, and pause appropriately to allow interpretation. Additionally, providers should assess patient understanding of what has been discussed. After the medical visit, providers should consider discussing with the interpreter any issues with communication or cultural factors noted to have affected the visit.

- Conclusion: Providers should utilize a professional medical interpreter for visits with persons with LEP. Appropriate communication techniques, including talking in first and second tenses and maintaining eye contact with the patient rather than the interpreter, are important for a successful visit. Realizing patients may have interpreter preferences is also important to facilitate patient-centered-care.

Key words: language barriers; quality of care; physician-patient communication; interpreter services.

The United States is a diverse country that includes many persons whose first language is not English. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, more than 63 million persons age 5 and above (about 51 million adults) reported speaking a language other than English at home. Also, about 25.7 million of the population age 5 and up (around 10.6 million adults) noted speaking English less than “very well” [1]. Protecting people from discrimination based on the language they speak is highlighted in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (which focuses on those receiving federal funding). President Clinton, furthermore, in 2000 signed Executive Order 13166, which encouraged federal agencies to provide appropriate access of their services to those with limited English proficiency (LEP) [2,3].

The benefits of using professional interpreters is well-documented. In addition to increased satisfaction with communication when professional medical interpreters are used [4], they also make fewer clinically significant interpretation errors compared to ad hoc interpreters (ie, untrained individuals such as bilingual staff member, family member, or friend who are asked to interpret) [5–7]. LEP patients who do not have a professional interpreter have less understanding of their medical issues, have less satisfaction of their medical care, and may have more tests ordered and be hospitalized more often compared to those who do utilize professional medical interpreters [8]. In addition to improved satisfaction and understanding of medical diagnoses, hospitalized persons requiring interpreters who utilized a professional medical interpreter on admission and discharge were noted to have a shorter length of stay than persons who required an interpreter and did not receive one [9].

Despite the documented benefits of using professional interpreters, they are underutilized. Reasons include underfunded medical interpreting services [10,11], lack of awareness of the risks involved with using an ad hoc interpreter [2,12], providers using their own or another worker’s limited second language skills to communicate rather than using a professional medical interpreter [13,14], perceived delay in obtaining a professional medical interpreter, and judging a medical situation as minor rather than complex [13]. In this article, the roles, importance, and considerations of using a professional medical interpreter are explored.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 23-year-old married Somali-speaking female who moved to the United States recently called a local primary care provider’s office to schedule an appointment. When asked the reason for the visit, she said the reason was private. The clinical assistant scheduled her with the next available provider.

When the patient arrived for her clinic appointment, a clinical assistant roomed her and her mother and asked the patient the reason for the visit. The patient remained quiet and her mother replied that she needed to speak with the doctor. When the female medical provider entered, she observed that the patient appeared anxious. When the doctor initiated conversation with the patient, she noted that her English was limited. Her mother tried to explain the reason for the visit saying her daughter was having severe pain. She then pointed towards her daughter’s lower abdomen. The clinician noted the limited English abilities of the patient and mother and used the interpreter line to request a Somali interpreter and placed the first available interpreter available on speaker.

How can patients who need an interpreter be identified?

Health care systems can facilitate identifying patients in need of an interpreter by routinely collecting information on LEP status. The patient should be asked during registration if her or she speaks English and has a preferred language, and the answers should be recorded in the medical record [3]. If an interpreter is used during the hospital stay, it should be recorded to alert future providers to the need of an interpreter [15]. Patients may speak a dialect of a common language and this also should be noted, as an interpreter with a similar dialect to the patient should ideally be requested when necessary [16]. Furthermore, health care systems can measure rate of screening for language need at registration and rate of interpreter use during hospital stay to assess language need and adequacy of provision of interpreters to LEP patients [15].

It should be noted that patients may be wary about the presence of an interpreter. In one study involving pediatric oncologists and Spanish-speaking parents, the former reported concern regarding the accuracy of interpretation and the latter were concerned about missing out on important information even with the use of professional medical interpreters [17]. The concern for accuracy of interpreting was shared in a study by Chinese and Vietnamese Americans with LEP [18] as well as in a Swedish study involving Arabic-speaking persons. In the latter study, Arabic-speaking patients also felt uncomfortable speaking about bodily issues in the presence of interpreters [19]. In a study of Latina patients, there were concerns about confidentiality with interpreters [20].

What is the role of the interpreter? Should they offer emotional support to the patient?

Interpreter-as-conduit reflects a neutral, more literal information exchange and is preferred by certain medical providers who prioritize a more exact interpretation of the medical conversation. In this role, the interpreter assumes a more passive role and the emphasis is on the interpreter’s linguistic ability [21]. Providers need to be aware that word-for-word interpretation may not align with what is regarded as culturally sensitive care—such as when the term “cancer” is to be used. Also, word-for-word interpretation does not necessarily mean the patient will understand what is being interpreted if the terminology does not reflect the literacy level or dialect of the person with LEP [22].

Interpreters may also assume an active role, sometimes referred to as clarifier and cultural broker. Clarifying may be utilized, for example, when a medical provider is discussing complicated treatment options. This requires an interpreter to step out of a conduit role (if that is the preferred role) and confirm or clarify information to ensure accurate information exchange [21,23]. As a cultural broker, communication between provider and patient is exchanged in a manner that reflects consideration of the patient’s cultural background. Interpreters may explain, to the provider, the cultural reason for the patient’s perspective of what is causing or contributing to the illness. Cultural brokering may as well include communicating the medical terminology and disease explanation, given by the medical provider, in a way that the patient would understand. This role, additionally, can involve educating the provider about aspects of the culture that may influence the patient’s communication with him or her [22].

Furthermore, interpreters may fulfill an advocate role for patients by helping them understand the health care system and increasing patient empowerment by seeking information and services that the patient may not know to ask about [23].

The interpreter may offer emotional support during a medical visit, for example, where the diagnosis of cancer is conveyed. In such a case, an interpreter’s emotional support may be considered by providers to be appropriate. In contrast, with visits related to mental health evaluations, having the interpreter remain neutral, rather than being a more active participant by offering emotional support, may be preferred [24]. In addition to interpreters remaining more neutral during mental health visits, providers may prefer that interpreters not speak with the patient prior to the visit, depending on the mental health condition, as negative therapeutic consequences may occur [21]. Trust is an important element of the provider-patient relationship and, as such, there is concern on the part of some providers that if the trust of patients falls to the interpreter rather than to the provider, then therapeutic progress may be compromised [24]. In general, clarifying with interpreters the goals of the visit and expectations regarding speaking to the patient outside of the visit may ensure the provider-patient relationship is not diminished [21].

What are the disadvantages and caveats of using family members or bilingual staff as interpreters?

Although family members and other ad hoc interpreters may be present and willing to interpret, the risk of miscommunication is greater than with professional medical interpreters [5,6]. This risk of miscommunication extends to partially bilingual medical providers who do not utilize appropriate interpreter services [10,25]. Ad hoc interpreters may try to answer on behalf the patient [6,26] and may not have the appropriate medical terminology to correctly interpret what the provider is trying to communicate to the patient [6].

Professional medical interpreters are trained to facilitate communication of a spoken language in a medical setting [2,10]. Certification is offered by the National Board of Certification for Medical Interpreters and the Certification Commission for Healthcare Interpreters. In order to be certified certain requirements must be met which include a minimum of 40 hours of health care interpreter training (which includes medical terminology as well as roles and ethics involved in medical interpreting) as well as demonstrated oral proficiency in English as well as another chosen language (such as Spanish) [10].

In certain circumstances, patients may feel more comfortable disclosing personal details with a professional medical interpreter rather than in the presence of an ad hoc interpreter. For example, more details of traumatic events and psychological symptoms were spoken of in the presence of a professional, rather than an ad hoc, interpreter in medical interviews of asylum seekers requiring an interpreter in Switzerland. In the presence of ad hoc interpreters, more physical symptoms were disclosed rather than psychological [6].

Furthermore, in visits concerning sexuality or abuse issues, using family members as interpreters may violate privacy concerns of the patient [2,27]. Additionally, in certain cultures where respect for elders is very important, parents who use children as interpreters may feel that the structure of the family changes when he or she interprets on behalf of the parent [18]. Also, what children consider as embarrassing may not be interpreted to either the parent or to the care provider [8]. Furthermore, one should note there are ethical issues of using non-adult children as interpreters in situations involving confidentiality and privacy—by doing so, there may be resulting harmful effects on non-adult children [27,28].

Patients may at times decline the use of a professional medical interpreter and prefer to have a family member interpret; this preference should be documented in the patient’s medical chart [10]. Caution should be had using an ad hoc interpreter when obtaining informed consent [12].

What professional interpreting services are available to the clinician?

For the most part, access to interpreters via a telephone service is widely available [10]. The cost of providing interpreters in-person and/or remotely varies depending on the health care site [29–31] In general, considerations of using professional medical interpreters, whether remotely or in-person, involves accessibility and cost. There are certain sites that have explored having a shared network of interpreters available via the telephone and videoconference to reduce the cost of providing interpreters for individual hospitals [32]. While the costs of providing a person with LEP with interpretation varies depending on the health care site, the costs of not providing a professional medical interpreter should be considered as well, which include greater malpractice risk and potential medical errors [32]. In addition, the use of employees as interpreters takes time away from their respective jobs, which results in staff time lost [31].

In-person interpreting may be preferred for certain medical visits, as an in-person interpreter can interpret both verbal and nonverbal communication [16]. When emotional support is anticipated, in-person interpreting is usually preferred by providers [24]. There may be improved cultural competence when using an in-person interpreter, which may be important for certain visits such as those involving end-of life care discussions [4]. One concern may involve the comfort level of the patient if he or she personally knows the interpreter; this can occur in smaller ethnic communities [12]. Telephonic interpreting may be preferred in certain medical situations where confidentiality is desired [16].

For providers working with persons who are deaf, options for interpreting include in-person sign language interpreters as well as remote videoconference interpretation [10].

- Are in-person interpreting and remote interpreting comparable?

In general, using in-person or remote interpreters does not significantly change patient satisfaction. In a study involving Spanish-speaking patients in a clinic setting, persons requiring an interpreter rated satisfaction of interpreting between in-person, videoconferencing, and telephonic methods highly with no significant differences. Of note, though, medical providers and interpreters preferred in-person rather than the 2 remote interpreting options [33]. In a different study involving Spanish, Chinese, Russian, or Vietnamese interpreters, satisfaction of information exchange was considered equal among the 3 interpreting modalities, although in-person interpreting was felt to establish rapport between clinician and patient with LEP better than telephonic and videoconferencing interpreting [35]. Additionally, in a study of providers in a clinic setting who worked with persons with LEP, no significant differences were noted in provider satisfaction of the medical visit, or in the quality of interpretation or communication, when using in-person versus remote videoconferencing interpretation. Providers, though, noted improved knowledge of the patient’s cultural beliefs when using in-person interpreting [4].

Regarding the question of a difference in understanding when using in-person versus remote interpreters, a study was done in a pediatric emergency department (ED) that compared in-person and telephonic interpretation. Family understanding of the discharge diagnosis was high (about 95%) regardless of whether an in-person or telephonic interpreter was utilized [36]. In a different study comparing telephone and video interpretation in a pediatric ED, while quality of communication and interpretation were rated similarly, the parents who used video interpretation were more likely to name their child’s diagnosis correctly [29].

Case Continued

The physician proceeded with introductions and explained that all conversations would be interpreted. She further stated that if there were any questions, the patient and mother should feel free to ask them. Via the interpreter, who was male, the provider began by asking about the nature of the abdominal pain. The patient looked to her mother and then down without answering. The mother nodded, but did not say more. The provider wondered if their reticence might be due to discomfort with discussing the issue through a male interpreter. The physician asked the patient if she would prefer a female interpreter and, once that was confirmed, she asked if she wanted an in-person or telephonic interpreter. The mother requested a female in-person interpreter.

How might gender-specific issues impact working with an interpreter?

As gender concordance of patient and physician [37] at times is desired, gender concordance of patient and interpreter [16,18] may also be important to optimize communication of gender-specific issues [16,18,37]. For example, an Arabic-speaking man from the Middle East may prefer to discuss sexuality-related concerns in the presence of a male rather than female interpreter [16]. An Arabic-speaking female who has a preference for female providers may prefer a female interpreter when discussing sexuality and undergoing a physical examination [19]. In one study, the majority of Somali females preferred female interpreters as well as female providers for breast, pelvic, and abdominal examinations [38]. If a same-gender interpreter cannot be present, an option is to have the interpreter either leave the room or step behind a curtain or turn away from the patient during a sensitive part of the physical examination [39].

What are recommended strategies for using a medical interpreter?

It is often helpful to have a brief discussion with the interpreter prior to the medical visit with the patient to speak about the general topics that will be discussed (especially if the topics involve sensitive issues or news that could be upsetting to the patient) and the goal of the visit [2, 11]. Certain topics may be viewed dissimilarly in different cultures, thus approaching the interpreter from the view point of cultural broker or liaison [10] may bring to light cultural factors that may influence the medical visit [40,41]. the name of the interpreter should be noted for documentation purposes [10].

To start the visit, introductions of everyone involved should take place with a brief disclosure about the role of the interpreter and assurance of confidentiality on the part of the interpreter [2,11]. Also, the provider should set the expectation that all statements said in the room will be interpreted so that all persons can understand what it being spoken [10].

There are several options for where each person should be positioned. In some medical visits, a triangle is pursued where the interpreter sits lateral to the provider, but this may lead to challenges in maintaining eye contact between the patient and provider. Another option is have the interpreter sit next to [10] and slightly behind the patient to improve eye contact between provider-patient and to maintain the patient-provider relationship [2,41]. When seated, the medical provider should try to sit at the same level as the patient [16]. Seating is different with persons requiring the use of sign language interpreters as the interpreter needs to be visible to the patient for communications purposes. One possibility is having the interpreter sit beside and slightly behind the provider; this positioning allows the patient to understand what is being communicated and also allows the patient to understand what is being communicated and allows him or her to see the provider during the conversation [40].