User login

Coaching Supports Patient Aligned Care Teams

In 2010, the VHA implemented the patient-centered medical home model of primary care health care as part of its transformational T-21 Initiatives.1 Now known as Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), the key pillars of the model include the expanded roles and responsibilities of multidisciplinary care teams who provide enhanced access and coordinated care. This model is based on a foundation of adequate resources, patient centeredness, and process improvement (Figure 1).

The national implementation strategy consisted of an initial educational conference with 3,600 attendees. The conference included a series of PACT learning collaboratives that engaged > 300 primary care teams, 5 demonstration laboratories, and educational outreach through learning centers and on-site consultations. Despite an aggressive national implementation plan, many frontline primary care teams struggled to translate the medical home theory into process.

Background

The Richard L. Roudebush VAMC (RLRVAMC) is a large tertiary medical center providing care to > 44,000 primary care patients. This care is delivered by 58 primary care physicians (PCPs) in 5 hospital-based outpatient clinics, including 1 large teaching clinic, 3 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), and a clinic that serves recently returned active-duty veterans. Administrative nursing and clerical associates report to the Office of Ambulatory Care, and physicians and nurse practitioners report to the Medicine Service. Before the implementation of the PACT model, the functional unit of primary care was an entire clinic, typically consisting of 4 to 10 PCPs, nurses, and clerical associates.

Discussions about process change had previously occurred through monthly service or clinic meetings in which administrative leaders provided direction to frontline staff. This culture of top-down leadership drove process change but was not always effective and empowering for practice change. With the implementation of PACT, the functional unit of primary care shifted from the larger clinic to a team composed of a PCP, a nurse, a licensed nurse practitioner or health technician, and a clerical associate.

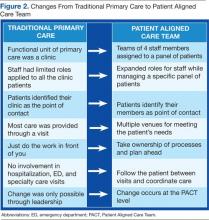

The care delivery system fundamentally changed from the traditional model to a medical home model (Figure 2). This group now represented the fundamental clinical microsystem for the delivery of primary care within the VA medical home model.2 The experience of Batalden and colleagues at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center suggests that such microsystems are very effective units of change.3 The key challenge presented to the primary care leadership was how to link these clinical PACT microsystems with an effective process that would guide practice redesign.

The concept of practice coaching or facilitation as a mechanism for physician offices to adopt evidence-based medicine and quality improvement dates to the early 1980s in England. This model spread to the U.S. in the 1990s and has continued to be used as a mechanism for leading clinical practice redesign.4 In traditional practice facilitation, a trained individual is brought in from outside the practice to help adopt evidence-based medicine guidelines.5 This individual works with the practice to implement changes that translate into patient outcome improvements.

Unlike consultation, this facilitator maintains a long-term relationship with the team as they work together to achieve goals. More important, the facilitator assists the team in developing improvement processes that are sustainable as they become incorporated within the fabric of the team culture and remain after the coach is gone. There are several reviews of clinical practice coaching that support its effectiveness in implementing evidence-based primary care guidelines.6,7 The Affordable Care Act contains provisions for the use of this model in promoting best practices and quality care.8 Manuals developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality outline how to develop a practice facilitation program.9,10

Related: Infusing Gerontologic Practice Into PACT

Essential to all practice facilitation models is the effective use of quality improvement tools. The RLRVAMC adopted the VHA Lean Healthcare Improvement Framework, which includes an approach for rapid cycle change.

The RLRVAMC adopted the facilitative coaching model in November 2011, using internal coaches who were assigned to the fundamental microsystem of its medical home.

Coach Selection

Many facilitative coaching models described in the literature use external coaches. Frequently cited advantages of external coaches include having dedicated time, receiving standardized training in facilitation, and being regarded as neutral to internal conflicts. The RLRVAMC staff elected to identify internal coaches. Advantages of this approach include the use of existing resources, the ability to develop long-term continuous relationships with PACTs, and the ability to access key internal resources to assist the team. Also, using internal individuals holding primary care leadership positions was critical to the coaching model.

Thirty-eight PACTs were initially created, and 15 internal coaches were identified. These individuals included the associate chief of staff of Ambulatory Care, chief nurse for Clinic Operations, business administrators in primary care, and all frontline unit managers and supervisors. This level of management involvement provided content expertise about primary care operations and equally important, carried the authority to implement change.

Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans

In addition, this approach provided considerable leadership credibility among frontline PACT staff. Given the large number of PACTs requiring coaching, coach recruitment was expanded to include other primary care administrative staff, such as the leads for the CBOCs, Prevention and Behavioral Health programs, System Redesign, and Telehealth Services. The most recent phase has included registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, health technicians, and physicians from high- functioning PACT teams who have experienced the process and who can now devote time to being coaches.

Qulifications and Training

Although the literature suggests multiple qualifications for practice coaches, there is a general agreement regarding core skills for strong facilitation, which includes interpersonal skills, knowledge of process improvement techniques, and an understanding of data acquisition and analysis.10 Strong interpersonal skills are often inherent but are a critical factor in motivating team members and managing conflicts that arise. Potential coaches were not selected if these skills were poorly developed.

The authors’ experiences have shown that although content knowledge about primary care operations is very helpful, it is not essential to being an effective coach. The facilitation model that was adopted for the program, as described by Bens, focuses predominately on process and not content expertise.11 The facilitator’s role is to apply a structural framework; ie, methods and tools that capitalize on content knowledge of frontline staff in identifying changes needed to implement the medical home.

Related: Updates in Specialty Care

Also, although knowledge of primary care operations was not required, formal training in understanding the goals of the medical home and the metrics related to PACT was essential for successful coaching. All coaches were required to attend PACT training sessions. Coaches were also expected to have basic training or experience in system redesign with the majority of the coaches completing Yellow Belt training, which is an introduction to the methods of process improvement through the lean thinking business model. A coaching manual was developed that contained information related to meeting structures, data definitions, extraction, and interpretation. A coaching website was developed that provided links to data sources and definitions. PACT-related tools, such as instructions on conducting group visits, phone visits, and use of population management were disseminated.

Coach-Team Meeting Structure

Coaches were assigned to teams by matching the skills of the coach with the team needs. Initially, sessions were held weekly for 1 hour, though this typically evolved into biweekly meetings. Clinic schedules were blocked, allowing PACTs the time to meet with their coaches. A ratio of 1 coach to 2 PACTs was considered optimal for individualized team meetings. The exceptions were the CBOCs, where several teams met together due to the need for coaches to travel. Meetings were held away from clinical areas to avoid distractions. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were used to plan and implement process improvements. The average time commitment for a coach assigned to 2 teams was between 2 to 4 hours a week.

The initial coaching sessions tended to be more structured, clearly defining the coach role, developing team building, identifying the goals, and outlining process improvement tools. Common challenges for the coaches were keeping teams focused and optimally managing time by preventing prolonged conversations unrelated to process improvement. Many frontline staff had never been empowered to change their practices, so their initial reaction was to focus on problems and not solutions. Once team relationships were established, the strong influence of nursing or clerical associates exerted on the PCP’ s willingness to change became evident and a key factor for success. Often the leaders of change are not the physicians, highlighting the influence of team building and the willingness of individuals to change practice due to team relationships and not by authority.12

Data Use

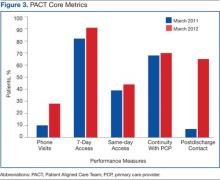

Before the implementation of this model, PACT data and metrics were posted in the clinics and briefly discussed at service-level meetings. However, this data-sharing approach rarely generated team members’ interest. By using coaching, personalized data reports that displayed team-specific information in comparison to the overall service and national VA goals were found to be a more effective technique for sharing data and performance metrics. National VA PACT core metrics tracked the following: (1) percentage of same-day appointments with PCP ratio—target 70%; (2) ratio of nontraditional encounters—target 20%; (3) percentage of continuity with PCP—target 77%; and (4) percentage of 2-day contact postdischarge ratio—target 75%. Figure 3 shows the improvements made as a facility from March 2011 (pre-PACT implementation) to March 2012 (post-PACT implementation).

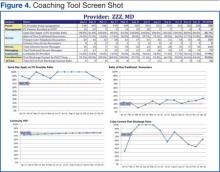

A graphic display of the team’s data, including metrics related to access, continuity, and postdischarge follow-up was reviewed monthly, and the coach provided detailed explanations (Figure 4). Of particular importance to the teams was the ability to individually identify those patients who failed the metric. Review of these “fallouts” at a coaching session often resulted in reliable, consistent process improvements that addressed the failed process.

Coach-to-Coach Meetings

Critical to the RLRVAMC coaching model were the weekly 1-hour coach-to-coach meetings. Most of the coach training occurred during these sessions, either formally or via feedback and discussion. Coaches discussed their teams’ progress, brought back questions from the teams, and sought guidance from one another. Executive leaders, who were also coaches, were present at these meetings and provided the opportunity to implement broader operational changes quickly. Coaches also served as a communication venue for frontline staff to express their concerns to primary care leaders during these meetings.

Limitations

Practice facilitation that uses internal coaches for a clinical PACT microsystem may present several potential challenges. Large primary care practices require a pool of coaches who are willing to commit the necessary time required for successful implementation of this model. Although the coaches dedicate this time as collateral duty, many express that the time spent with their teams is a rewarding experience outside of their administrative roles. The coaches express satisfaction when teams meet their goals and PDSA cycles are successful.

Coaches require significant amounts of training to reach the level of effectiveness required. Teams must realize and appreciate the importance of dedicating time away from the competing priority of patient care.

Implementation of the coaching model for physician trainees in the teaching clinic has not been successful due to the teaching clinic schedule and other issues. Also related to the complexity of the teaching clinic schedule, the coaching model did not significantly improve continuity. Coaches have recently been assigned to the teaching clinic, and each team will be identifying PDSA cycles to approach the implementation of PACT principles.

Conclusion

Despite the aforementioned challenges, the outcomes are clear. The implementation of the coaching model, using internal coaches, resulted in a significant improvement of the ability of the staff to achieve the national PACT metrics (Figure 3). More important, the model created a new structural organization for change within primary care that reversed a culture of top-down leadership to that of team empowerment.

Teams that experienced practice facilitation developed ownership in their processes, data, and performance improvement and now have a more direct mechanism of communicating with primary care leadership. The coaching model moved the teams forward from having received PACT education to having the confidence and tools to implement PACTs. Staff progressed from looking at the data given to them to collecting and interpreting the data themselves. The teams are able to articulate how they fit in to the PACT model and enthusiastically monitor their progress. As primary care moves forward with the medical home, the facilitative coaching model offers a promising option for successful implementation.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Klein S. The Veterans Health Administration: Implementing patient-centered medical homes in the nation’s largest integrated delivery system. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2011;16:1537.

2. Godfrey MM, ed. Clinical Microsystem Action Guide: Improving Health Care by Improving Your Microsystem. Version 2.1. The Dartmouth Institute Website. http://clinicalmicrosys.dartmouth.edu/wp -content/uploads/2014/07/CMAG040104.pdf. Published 2004. Accessed January 23, 2015.

3. Batalden PB, Nelson EC, Edwards WH, Godfrey MM, Mohr JJ. Microsystems in health care: Part 9. Developing a small clinical unit to attain peak performance. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29(11):575-585.

4. Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, et al. Effect of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(suppl 1):S33-S34, S92.

5. Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Robinson A, Niebauer L, Ford A. Practice facilitators and practice-based research networks. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(5):506-510.

6. Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63-74.

7. Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: A review of the literature. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):581-588.

8. Grumbach K, Bainbridge E, Bodenheimer T. Facilitating improvement in primary care: The promise of practice coaching. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;15:1-14.

9. Knox L, Taylor EF, Geonnotti K, et al. Developing and Running a Primary Care Practice Facilitation Program: A How-To Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0011.

10. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Integrating Chronic Care and Business Strategies in the Safety Net: A Practice Coaching Manual. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Website. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/primary-care /coachmnl/index.html. Published December 2012. Accessed February 26, 2015.

11. Bens I. Facilitation With Ease! Core Skills for Facilitators, Team Leaders and Members, Managers, Consultants and Trainers. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005.

12. Bodenheimer T. Building Teams in Primary Care: Lessons Learned: Part 1 and 2. Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; July 2007.

In 2010, the VHA implemented the patient-centered medical home model of primary care health care as part of its transformational T-21 Initiatives.1 Now known as Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), the key pillars of the model include the expanded roles and responsibilities of multidisciplinary care teams who provide enhanced access and coordinated care. This model is based on a foundation of adequate resources, patient centeredness, and process improvement (Figure 1).

The national implementation strategy consisted of an initial educational conference with 3,600 attendees. The conference included a series of PACT learning collaboratives that engaged > 300 primary care teams, 5 demonstration laboratories, and educational outreach through learning centers and on-site consultations. Despite an aggressive national implementation plan, many frontline primary care teams struggled to translate the medical home theory into process.

Background

The Richard L. Roudebush VAMC (RLRVAMC) is a large tertiary medical center providing care to > 44,000 primary care patients. This care is delivered by 58 primary care physicians (PCPs) in 5 hospital-based outpatient clinics, including 1 large teaching clinic, 3 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), and a clinic that serves recently returned active-duty veterans. Administrative nursing and clerical associates report to the Office of Ambulatory Care, and physicians and nurse practitioners report to the Medicine Service. Before the implementation of the PACT model, the functional unit of primary care was an entire clinic, typically consisting of 4 to 10 PCPs, nurses, and clerical associates.

Discussions about process change had previously occurred through monthly service or clinic meetings in which administrative leaders provided direction to frontline staff. This culture of top-down leadership drove process change but was not always effective and empowering for practice change. With the implementation of PACT, the functional unit of primary care shifted from the larger clinic to a team composed of a PCP, a nurse, a licensed nurse practitioner or health technician, and a clerical associate.

The care delivery system fundamentally changed from the traditional model to a medical home model (Figure 2). This group now represented the fundamental clinical microsystem for the delivery of primary care within the VA medical home model.2 The experience of Batalden and colleagues at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center suggests that such microsystems are very effective units of change.3 The key challenge presented to the primary care leadership was how to link these clinical PACT microsystems with an effective process that would guide practice redesign.

The concept of practice coaching or facilitation as a mechanism for physician offices to adopt evidence-based medicine and quality improvement dates to the early 1980s in England. This model spread to the U.S. in the 1990s and has continued to be used as a mechanism for leading clinical practice redesign.4 In traditional practice facilitation, a trained individual is brought in from outside the practice to help adopt evidence-based medicine guidelines.5 This individual works with the practice to implement changes that translate into patient outcome improvements.

Unlike consultation, this facilitator maintains a long-term relationship with the team as they work together to achieve goals. More important, the facilitator assists the team in developing improvement processes that are sustainable as they become incorporated within the fabric of the team culture and remain after the coach is gone. There are several reviews of clinical practice coaching that support its effectiveness in implementing evidence-based primary care guidelines.6,7 The Affordable Care Act contains provisions for the use of this model in promoting best practices and quality care.8 Manuals developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality outline how to develop a practice facilitation program.9,10

Related: Infusing Gerontologic Practice Into PACT

Essential to all practice facilitation models is the effective use of quality improvement tools. The RLRVAMC adopted the VHA Lean Healthcare Improvement Framework, which includes an approach for rapid cycle change.

The RLRVAMC adopted the facilitative coaching model in November 2011, using internal coaches who were assigned to the fundamental microsystem of its medical home.

Coach Selection

Many facilitative coaching models described in the literature use external coaches. Frequently cited advantages of external coaches include having dedicated time, receiving standardized training in facilitation, and being regarded as neutral to internal conflicts. The RLRVAMC staff elected to identify internal coaches. Advantages of this approach include the use of existing resources, the ability to develop long-term continuous relationships with PACTs, and the ability to access key internal resources to assist the team. Also, using internal individuals holding primary care leadership positions was critical to the coaching model.

Thirty-eight PACTs were initially created, and 15 internal coaches were identified. These individuals included the associate chief of staff of Ambulatory Care, chief nurse for Clinic Operations, business administrators in primary care, and all frontline unit managers and supervisors. This level of management involvement provided content expertise about primary care operations and equally important, carried the authority to implement change.

Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans

In addition, this approach provided considerable leadership credibility among frontline PACT staff. Given the large number of PACTs requiring coaching, coach recruitment was expanded to include other primary care administrative staff, such as the leads for the CBOCs, Prevention and Behavioral Health programs, System Redesign, and Telehealth Services. The most recent phase has included registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, health technicians, and physicians from high- functioning PACT teams who have experienced the process and who can now devote time to being coaches.

Qulifications and Training

Although the literature suggests multiple qualifications for practice coaches, there is a general agreement regarding core skills for strong facilitation, which includes interpersonal skills, knowledge of process improvement techniques, and an understanding of data acquisition and analysis.10 Strong interpersonal skills are often inherent but are a critical factor in motivating team members and managing conflicts that arise. Potential coaches were not selected if these skills were poorly developed.

The authors’ experiences have shown that although content knowledge about primary care operations is very helpful, it is not essential to being an effective coach. The facilitation model that was adopted for the program, as described by Bens, focuses predominately on process and not content expertise.11 The facilitator’s role is to apply a structural framework; ie, methods and tools that capitalize on content knowledge of frontline staff in identifying changes needed to implement the medical home.

Related: Updates in Specialty Care

Also, although knowledge of primary care operations was not required, formal training in understanding the goals of the medical home and the metrics related to PACT was essential for successful coaching. All coaches were required to attend PACT training sessions. Coaches were also expected to have basic training or experience in system redesign with the majority of the coaches completing Yellow Belt training, which is an introduction to the methods of process improvement through the lean thinking business model. A coaching manual was developed that contained information related to meeting structures, data definitions, extraction, and interpretation. A coaching website was developed that provided links to data sources and definitions. PACT-related tools, such as instructions on conducting group visits, phone visits, and use of population management were disseminated.

Coach-Team Meeting Structure

Coaches were assigned to teams by matching the skills of the coach with the team needs. Initially, sessions were held weekly for 1 hour, though this typically evolved into biweekly meetings. Clinic schedules were blocked, allowing PACTs the time to meet with their coaches. A ratio of 1 coach to 2 PACTs was considered optimal for individualized team meetings. The exceptions were the CBOCs, where several teams met together due to the need for coaches to travel. Meetings were held away from clinical areas to avoid distractions. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were used to plan and implement process improvements. The average time commitment for a coach assigned to 2 teams was between 2 to 4 hours a week.

The initial coaching sessions tended to be more structured, clearly defining the coach role, developing team building, identifying the goals, and outlining process improvement tools. Common challenges for the coaches were keeping teams focused and optimally managing time by preventing prolonged conversations unrelated to process improvement. Many frontline staff had never been empowered to change their practices, so their initial reaction was to focus on problems and not solutions. Once team relationships were established, the strong influence of nursing or clerical associates exerted on the PCP’ s willingness to change became evident and a key factor for success. Often the leaders of change are not the physicians, highlighting the influence of team building and the willingness of individuals to change practice due to team relationships and not by authority.12

Data Use

Before the implementation of this model, PACT data and metrics were posted in the clinics and briefly discussed at service-level meetings. However, this data-sharing approach rarely generated team members’ interest. By using coaching, personalized data reports that displayed team-specific information in comparison to the overall service and national VA goals were found to be a more effective technique for sharing data and performance metrics. National VA PACT core metrics tracked the following: (1) percentage of same-day appointments with PCP ratio—target 70%; (2) ratio of nontraditional encounters—target 20%; (3) percentage of continuity with PCP—target 77%; and (4) percentage of 2-day contact postdischarge ratio—target 75%. Figure 3 shows the improvements made as a facility from March 2011 (pre-PACT implementation) to March 2012 (post-PACT implementation).

A graphic display of the team’s data, including metrics related to access, continuity, and postdischarge follow-up was reviewed monthly, and the coach provided detailed explanations (Figure 4). Of particular importance to the teams was the ability to individually identify those patients who failed the metric. Review of these “fallouts” at a coaching session often resulted in reliable, consistent process improvements that addressed the failed process.

Coach-to-Coach Meetings

Critical to the RLRVAMC coaching model were the weekly 1-hour coach-to-coach meetings. Most of the coach training occurred during these sessions, either formally or via feedback and discussion. Coaches discussed their teams’ progress, brought back questions from the teams, and sought guidance from one another. Executive leaders, who were also coaches, were present at these meetings and provided the opportunity to implement broader operational changes quickly. Coaches also served as a communication venue for frontline staff to express their concerns to primary care leaders during these meetings.

Limitations

Practice facilitation that uses internal coaches for a clinical PACT microsystem may present several potential challenges. Large primary care practices require a pool of coaches who are willing to commit the necessary time required for successful implementation of this model. Although the coaches dedicate this time as collateral duty, many express that the time spent with their teams is a rewarding experience outside of their administrative roles. The coaches express satisfaction when teams meet their goals and PDSA cycles are successful.

Coaches require significant amounts of training to reach the level of effectiveness required. Teams must realize and appreciate the importance of dedicating time away from the competing priority of patient care.

Implementation of the coaching model for physician trainees in the teaching clinic has not been successful due to the teaching clinic schedule and other issues. Also related to the complexity of the teaching clinic schedule, the coaching model did not significantly improve continuity. Coaches have recently been assigned to the teaching clinic, and each team will be identifying PDSA cycles to approach the implementation of PACT principles.

Conclusion

Despite the aforementioned challenges, the outcomes are clear. The implementation of the coaching model, using internal coaches, resulted in a significant improvement of the ability of the staff to achieve the national PACT metrics (Figure 3). More important, the model created a new structural organization for change within primary care that reversed a culture of top-down leadership to that of team empowerment.

Teams that experienced practice facilitation developed ownership in their processes, data, and performance improvement and now have a more direct mechanism of communicating with primary care leadership. The coaching model moved the teams forward from having received PACT education to having the confidence and tools to implement PACTs. Staff progressed from looking at the data given to them to collecting and interpreting the data themselves. The teams are able to articulate how they fit in to the PACT model and enthusiastically monitor their progress. As primary care moves forward with the medical home, the facilitative coaching model offers a promising option for successful implementation.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

In 2010, the VHA implemented the patient-centered medical home model of primary care health care as part of its transformational T-21 Initiatives.1 Now known as Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), the key pillars of the model include the expanded roles and responsibilities of multidisciplinary care teams who provide enhanced access and coordinated care. This model is based on a foundation of adequate resources, patient centeredness, and process improvement (Figure 1).

The national implementation strategy consisted of an initial educational conference with 3,600 attendees. The conference included a series of PACT learning collaboratives that engaged > 300 primary care teams, 5 demonstration laboratories, and educational outreach through learning centers and on-site consultations. Despite an aggressive national implementation plan, many frontline primary care teams struggled to translate the medical home theory into process.

Background

The Richard L. Roudebush VAMC (RLRVAMC) is a large tertiary medical center providing care to > 44,000 primary care patients. This care is delivered by 58 primary care physicians (PCPs) in 5 hospital-based outpatient clinics, including 1 large teaching clinic, 3 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), and a clinic that serves recently returned active-duty veterans. Administrative nursing and clerical associates report to the Office of Ambulatory Care, and physicians and nurse practitioners report to the Medicine Service. Before the implementation of the PACT model, the functional unit of primary care was an entire clinic, typically consisting of 4 to 10 PCPs, nurses, and clerical associates.

Discussions about process change had previously occurred through monthly service or clinic meetings in which administrative leaders provided direction to frontline staff. This culture of top-down leadership drove process change but was not always effective and empowering for practice change. With the implementation of PACT, the functional unit of primary care shifted from the larger clinic to a team composed of a PCP, a nurse, a licensed nurse practitioner or health technician, and a clerical associate.

The care delivery system fundamentally changed from the traditional model to a medical home model (Figure 2). This group now represented the fundamental clinical microsystem for the delivery of primary care within the VA medical home model.2 The experience of Batalden and colleagues at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center suggests that such microsystems are very effective units of change.3 The key challenge presented to the primary care leadership was how to link these clinical PACT microsystems with an effective process that would guide practice redesign.

The concept of practice coaching or facilitation as a mechanism for physician offices to adopt evidence-based medicine and quality improvement dates to the early 1980s in England. This model spread to the U.S. in the 1990s and has continued to be used as a mechanism for leading clinical practice redesign.4 In traditional practice facilitation, a trained individual is brought in from outside the practice to help adopt evidence-based medicine guidelines.5 This individual works with the practice to implement changes that translate into patient outcome improvements.

Unlike consultation, this facilitator maintains a long-term relationship with the team as they work together to achieve goals. More important, the facilitator assists the team in developing improvement processes that are sustainable as they become incorporated within the fabric of the team culture and remain after the coach is gone. There are several reviews of clinical practice coaching that support its effectiveness in implementing evidence-based primary care guidelines.6,7 The Affordable Care Act contains provisions for the use of this model in promoting best practices and quality care.8 Manuals developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality outline how to develop a practice facilitation program.9,10

Related: Infusing Gerontologic Practice Into PACT

Essential to all practice facilitation models is the effective use of quality improvement tools. The RLRVAMC adopted the VHA Lean Healthcare Improvement Framework, which includes an approach for rapid cycle change.

The RLRVAMC adopted the facilitative coaching model in November 2011, using internal coaches who were assigned to the fundamental microsystem of its medical home.

Coach Selection

Many facilitative coaching models described in the literature use external coaches. Frequently cited advantages of external coaches include having dedicated time, receiving standardized training in facilitation, and being regarded as neutral to internal conflicts. The RLRVAMC staff elected to identify internal coaches. Advantages of this approach include the use of existing resources, the ability to develop long-term continuous relationships with PACTs, and the ability to access key internal resources to assist the team. Also, using internal individuals holding primary care leadership positions was critical to the coaching model.

Thirty-eight PACTs were initially created, and 15 internal coaches were identified. These individuals included the associate chief of staff of Ambulatory Care, chief nurse for Clinic Operations, business administrators in primary care, and all frontline unit managers and supervisors. This level of management involvement provided content expertise about primary care operations and equally important, carried the authority to implement change.

Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans

In addition, this approach provided considerable leadership credibility among frontline PACT staff. Given the large number of PACTs requiring coaching, coach recruitment was expanded to include other primary care administrative staff, such as the leads for the CBOCs, Prevention and Behavioral Health programs, System Redesign, and Telehealth Services. The most recent phase has included registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, health technicians, and physicians from high- functioning PACT teams who have experienced the process and who can now devote time to being coaches.

Qulifications and Training

Although the literature suggests multiple qualifications for practice coaches, there is a general agreement regarding core skills for strong facilitation, which includes interpersonal skills, knowledge of process improvement techniques, and an understanding of data acquisition and analysis.10 Strong interpersonal skills are often inherent but are a critical factor in motivating team members and managing conflicts that arise. Potential coaches were not selected if these skills were poorly developed.

The authors’ experiences have shown that although content knowledge about primary care operations is very helpful, it is not essential to being an effective coach. The facilitation model that was adopted for the program, as described by Bens, focuses predominately on process and not content expertise.11 The facilitator’s role is to apply a structural framework; ie, methods and tools that capitalize on content knowledge of frontline staff in identifying changes needed to implement the medical home.

Related: Updates in Specialty Care

Also, although knowledge of primary care operations was not required, formal training in understanding the goals of the medical home and the metrics related to PACT was essential for successful coaching. All coaches were required to attend PACT training sessions. Coaches were also expected to have basic training or experience in system redesign with the majority of the coaches completing Yellow Belt training, which is an introduction to the methods of process improvement through the lean thinking business model. A coaching manual was developed that contained information related to meeting structures, data definitions, extraction, and interpretation. A coaching website was developed that provided links to data sources and definitions. PACT-related tools, such as instructions on conducting group visits, phone visits, and use of population management were disseminated.

Coach-Team Meeting Structure

Coaches were assigned to teams by matching the skills of the coach with the team needs. Initially, sessions were held weekly for 1 hour, though this typically evolved into biweekly meetings. Clinic schedules were blocked, allowing PACTs the time to meet with their coaches. A ratio of 1 coach to 2 PACTs was considered optimal for individualized team meetings. The exceptions were the CBOCs, where several teams met together due to the need for coaches to travel. Meetings were held away from clinical areas to avoid distractions. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were used to plan and implement process improvements. The average time commitment for a coach assigned to 2 teams was between 2 to 4 hours a week.

The initial coaching sessions tended to be more structured, clearly defining the coach role, developing team building, identifying the goals, and outlining process improvement tools. Common challenges for the coaches were keeping teams focused and optimally managing time by preventing prolonged conversations unrelated to process improvement. Many frontline staff had never been empowered to change their practices, so their initial reaction was to focus on problems and not solutions. Once team relationships were established, the strong influence of nursing or clerical associates exerted on the PCP’ s willingness to change became evident and a key factor for success. Often the leaders of change are not the physicians, highlighting the influence of team building and the willingness of individuals to change practice due to team relationships and not by authority.12

Data Use

Before the implementation of this model, PACT data and metrics were posted in the clinics and briefly discussed at service-level meetings. However, this data-sharing approach rarely generated team members’ interest. By using coaching, personalized data reports that displayed team-specific information in comparison to the overall service and national VA goals were found to be a more effective technique for sharing data and performance metrics. National VA PACT core metrics tracked the following: (1) percentage of same-day appointments with PCP ratio—target 70%; (2) ratio of nontraditional encounters—target 20%; (3) percentage of continuity with PCP—target 77%; and (4) percentage of 2-day contact postdischarge ratio—target 75%. Figure 3 shows the improvements made as a facility from March 2011 (pre-PACT implementation) to March 2012 (post-PACT implementation).

A graphic display of the team’s data, including metrics related to access, continuity, and postdischarge follow-up was reviewed monthly, and the coach provided detailed explanations (Figure 4). Of particular importance to the teams was the ability to individually identify those patients who failed the metric. Review of these “fallouts” at a coaching session often resulted in reliable, consistent process improvements that addressed the failed process.

Coach-to-Coach Meetings

Critical to the RLRVAMC coaching model were the weekly 1-hour coach-to-coach meetings. Most of the coach training occurred during these sessions, either formally or via feedback and discussion. Coaches discussed their teams’ progress, brought back questions from the teams, and sought guidance from one another. Executive leaders, who were also coaches, were present at these meetings and provided the opportunity to implement broader operational changes quickly. Coaches also served as a communication venue for frontline staff to express their concerns to primary care leaders during these meetings.

Limitations

Practice facilitation that uses internal coaches for a clinical PACT microsystem may present several potential challenges. Large primary care practices require a pool of coaches who are willing to commit the necessary time required for successful implementation of this model. Although the coaches dedicate this time as collateral duty, many express that the time spent with their teams is a rewarding experience outside of their administrative roles. The coaches express satisfaction when teams meet their goals and PDSA cycles are successful.

Coaches require significant amounts of training to reach the level of effectiveness required. Teams must realize and appreciate the importance of dedicating time away from the competing priority of patient care.

Implementation of the coaching model for physician trainees in the teaching clinic has not been successful due to the teaching clinic schedule and other issues. Also related to the complexity of the teaching clinic schedule, the coaching model did not significantly improve continuity. Coaches have recently been assigned to the teaching clinic, and each team will be identifying PDSA cycles to approach the implementation of PACT principles.

Conclusion

Despite the aforementioned challenges, the outcomes are clear. The implementation of the coaching model, using internal coaches, resulted in a significant improvement of the ability of the staff to achieve the national PACT metrics (Figure 3). More important, the model created a new structural organization for change within primary care that reversed a culture of top-down leadership to that of team empowerment.

Teams that experienced practice facilitation developed ownership in their processes, data, and performance improvement and now have a more direct mechanism of communicating with primary care leadership. The coaching model moved the teams forward from having received PACT education to having the confidence and tools to implement PACTs. Staff progressed from looking at the data given to them to collecting and interpreting the data themselves. The teams are able to articulate how they fit in to the PACT model and enthusiastically monitor their progress. As primary care moves forward with the medical home, the facilitative coaching model offers a promising option for successful implementation.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Klein S. The Veterans Health Administration: Implementing patient-centered medical homes in the nation’s largest integrated delivery system. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2011;16:1537.

2. Godfrey MM, ed. Clinical Microsystem Action Guide: Improving Health Care by Improving Your Microsystem. Version 2.1. The Dartmouth Institute Website. http://clinicalmicrosys.dartmouth.edu/wp -content/uploads/2014/07/CMAG040104.pdf. Published 2004. Accessed January 23, 2015.

3. Batalden PB, Nelson EC, Edwards WH, Godfrey MM, Mohr JJ. Microsystems in health care: Part 9. Developing a small clinical unit to attain peak performance. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29(11):575-585.

4. Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, et al. Effect of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(suppl 1):S33-S34, S92.

5. Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Robinson A, Niebauer L, Ford A. Practice facilitators and practice-based research networks. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(5):506-510.

6. Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63-74.

7. Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: A review of the literature. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):581-588.

8. Grumbach K, Bainbridge E, Bodenheimer T. Facilitating improvement in primary care: The promise of practice coaching. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;15:1-14.

9. Knox L, Taylor EF, Geonnotti K, et al. Developing and Running a Primary Care Practice Facilitation Program: A How-To Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0011.

10. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Integrating Chronic Care and Business Strategies in the Safety Net: A Practice Coaching Manual. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Website. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/primary-care /coachmnl/index.html. Published December 2012. Accessed February 26, 2015.

11. Bens I. Facilitation With Ease! Core Skills for Facilitators, Team Leaders and Members, Managers, Consultants and Trainers. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005.

12. Bodenheimer T. Building Teams in Primary Care: Lessons Learned: Part 1 and 2. Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; July 2007.

1. Klein S. The Veterans Health Administration: Implementing patient-centered medical homes in the nation’s largest integrated delivery system. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2011;16:1537.

2. Godfrey MM, ed. Clinical Microsystem Action Guide: Improving Health Care by Improving Your Microsystem. Version 2.1. The Dartmouth Institute Website. http://clinicalmicrosys.dartmouth.edu/wp -content/uploads/2014/07/CMAG040104.pdf. Published 2004. Accessed January 23, 2015.

3. Batalden PB, Nelson EC, Edwards WH, Godfrey MM, Mohr JJ. Microsystems in health care: Part 9. Developing a small clinical unit to attain peak performance. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29(11):575-585.

4. Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, et al. Effect of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(suppl 1):S33-S34, S92.

5. Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Robinson A, Niebauer L, Ford A. Practice facilitators and practice-based research networks. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(5):506-510.

6. Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63-74.

7. Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: A review of the literature. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):581-588.

8. Grumbach K, Bainbridge E, Bodenheimer T. Facilitating improvement in primary care: The promise of practice coaching. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;15:1-14.

9. Knox L, Taylor EF, Geonnotti K, et al. Developing and Running a Primary Care Practice Facilitation Program: A How-To Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0011.

10. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Integrating Chronic Care and Business Strategies in the Safety Net: A Practice Coaching Manual. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Website. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/primary-care /coachmnl/index.html. Published December 2012. Accessed February 26, 2015.

11. Bens I. Facilitation With Ease! Core Skills for Facilitators, Team Leaders and Members, Managers, Consultants and Trainers. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005.

12. Bodenheimer T. Building Teams in Primary Care: Lessons Learned: Part 1 and 2. Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; July 2007.