User login

Trends in Hysterectomy Rates and Approaches in the VA

The VA operates the largest integrated health care system in the country, consisting of 144 hospitals and 1,221 outpatient clinics. This system provides medical care for about 22 million veterans. In 2015, women accounted for nearly 10% of the veteran population and are expected to increase to about 16% by 2040.1 With an expected population increase of 18,000 per year over the next 10 years, women are the fastest growing group of veterans.

The VA acknowledges that women are an integral part of the veteran community and that a paradigm shift must occur to meet their unique health needs. Although clinical services specific to women veterans’ health needs have been introduced within the VA, gynecologic surgical services must be addressed in order to improve access and provide comprehensive women’s health care within the VA system.

About 600,000 hysterectomies are performed annually in the U.S., making this procedure one of the most commonly performed in women.2 Over the past 30 years, technologic advances have allowed surgeons to perform more hysterectomies via minimally invasive methods. Both the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists have published consensus statements that minimally invasive hysterectomy should be the standard of care.3,4 Studies in non-VA facilities have shown that practice patterns in the route of hysterectomy have evolved with the advancement of surgical equipment and techniques.

It is uncertain, however, whether these changes in practice patterns exist in the VA, because there are limited published data. Given the frequency of hysterectomies in the U.S., the rate and route of this procedure are easily identifiable measures that can be evaluated and utilized as a comparison model for health care received within the VA vs the civilian sector.

The aim of this study was to assess the changes in rate and surgical approach to benign hysterectomy for women veterans at VAMCs and referrals to non-VA facilities over a 10-year period. The authors’ hypothesis was that a minimally invasive approach would be more common in recent years. This study also compares published national data to evaluate whether the VA is offering comparable surgical services to the civilian sector.

Methods

The institutional review boards of Indiana University and the Richard L. Roudebush VAMC in Indianapolis, Indiana, approved this retrospective cross-sectional study. The VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) authorized access to VA database information.

All women veterans who underwent hysterectomy for benign indications from fiscal years (FY) 2005 to 2014 were included. In order to identify this group, the authors queried the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and the Non-VA Care Cube for all hysterectomy current procedural terminology (CPT) codes typically performed for benign indications, including 58150, 58152, 58180, 58260, 58262, 58263, 58267, 58270, 58290, 58291, 58292, 58293, 58294, 58541, 58542, 58543, 58544, 58550, 58552, 58553, 58554, 58570, 58571, 58572, and 58573. For each patient identified, the following variables were collected: date of the procedure, facility location, primary CPT code, primary ICD-9 code, and patient age. Patients whose primary ICD-9 code was for a malignancy of gynecologic origin were excluded from the study.

The CDW is a national database collected by the VA Office of Information and Technology to provide clinical data for VA analytical purposes. The Non-VA Care Cube identifies services purchased for veterans with non-VA care dollars and, therefore, captures women veterans who were referred outside the VA for a hysterectomy. Additional data collected include age, gender, hospital complexity, place of care, payment location, primary CPT, primary ICD-9, and several other parameters. The annual number of women veterans accessing VA health care was extracted from the VSSC Unique Patients Cube.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy was defined as total laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, laparoscopic-supracervical hysterectomy, and robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy. Minimally invasive hysterectomy was defined as all laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies.

Frequency distributions between categoric variables were compared using chi-squared tests. The population-adjusted hysterectomy rates were estimated by dividing the total number of hysterectomies by the number of women veterans accessing VA medical care. Hysterectomy rates are reported as rate per 1,000 women per year. A time trend analysis was performed with linear regression to evaluate the slopes of trends for each route of hysterectomy, using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Redmond, WA). The authors analyzed the relationship between route of hysterectomy and fiscal year, using a multivariable logistic regression that was adjusted for age, district, and surgical diagnosis. The adjusted relative risk (RR) for each type of hysterectomy was reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 (Chicago, IL) with P < .05 defined as being statistically significant.To ensure the accuracy of the CDW data, the documented CPT and ICD-9 codes were compared between the CDW and the VA electronic medical records (EMR) for 400 charts selected at random. This cohort represents about 5% of the total charts and was felt to be an adequate measure of the entire sample since the CPT and ICD-9 codes were verified and matched 100% of the time. Demographic and descriptive data regarding body mass index, level of education, race, smoking status, medical comorbidities, and surgical history were excluded from the study because it was either not available or not consistently reported within the CDW.

Results

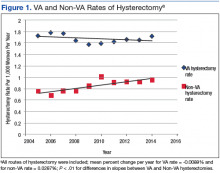

A retrospective query of the CDW identified 8,327 hysterectomies performed at the VA for benign indications from fiscal year (FY) 2005 to FY 2014. The total number of annual hysterectomies at the VA increased 30.7% from 710 in FY 2004 to 1,025 in FY 2014. The annual number of women veterans who accessed VA health care increased 30.8% from 412,271 to 596,011 during the same time frame. Thus, the population adjusted hysterectomy rate remained stable at 1.72 (Figure 1).

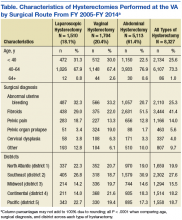

The authors also analyzed the VA data by district and decided to highlight the most recent data trends, as this is most applicable to how the VA currently operates. During FY 2014, the VA hysterectomy rates were as follows: district 1 (North Atlantic) 1.52; district 2 (Southeast) 2.21; district 3 (Midwest) 1.47; district 4 (Continental) 1.43; and district 5 (Pacific) 1.64 (Figure 2)

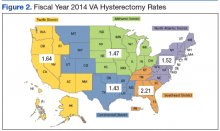

During the study period, calculated hysterectomy rates based on route at the VA showed that the laparoscopic hysterectomy rate increased from 0.11 to 0.53, the vaginal hysterectomy rate remained relatively stable at 0.34 to 0.37, and the abdominal hysterectomy rate declined from 1.28 to 0.8 (Figure 3).

Discussion

Although the total hysterectomy rate within the VA remained stable during the study period, the minimally invasive hysterectomy rate increased significantly. In FY 2014, the majority of hysterectomies at the VA were performed via a minimally invasive approach. Minimally invasive hysterectomy has many recognized advantages over abdominal hysterectomy as it offers a significant reduction in postoperative pain, narcotic use, length of stay, intraoperative blood loss, fever, deep venous thrombosis, and a faster recovery with return to baseline functioning thus improving overall quality of life.5-7 Previous literature of VA hysterectomy data from 1991 to 1997 reported an abdominal hysterectomy percentage of 74%, vaginal hysterectomy percentage of 22%, and laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy percentage of 4%.8

Additionally, previous literature of the civilian sector reported a national laparoscopic hysterectomy percentage of 32.4% in 2012, which is comparable to the laparoscopic hysterectomy percentage found in this study.9,10 These data highlight the growth of laparoscopic hysterectomy at the VA, which is comparable to that of the civilian sector.The Nationwide Inpatient Sample reported an abdominal hysterectomy percentage of 66.1% in 2003 and 52.8% in 2012.9,10 The authors observed a similar decline in the abdominal hysterectomy rate at the VA over the period studied. Although many factors may have contributed to this decline, the growth of laparoscopic hysterectomy was a possible contributing factor since the vaginal hysterectomy rate remained stable over the study period. Future studies are needed to evaluate surgical complications and readmission rates in order to more accurately assess the quality of gynecologic surgical care provided by the VA compared with the civilian sector.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several important strengths. First, the large sample size from VA nationwide databases included information from all VAMC performing hysterectomies. Second, this study included 10 years of data, with the latest data from 2014, allowing for depiction of both long-term and recent trends.

Potential issues with large databases such as the CDW and the Non-VA Care Cube included inaccurate coding of procedures and diagnoses as well as missing data. This possible limitation was addressed by randomly selecting 400 patients in the database to verify the database information against the patient’s EMR, which matched 100% of the time. In addition, the authors calculated the hysterectomy rates using a denominator based on all women veterans accessing VA health care, which included women who had previously had a hysterectomy. Therefore, the true hysterectomy rate may have been underestimated.

Conclusion

The VA operates the largest health care system in the U.S. with more than 500,000 women veterans currently utilizing VA health care.11 The VA provides services to women veterans living in urban, suburban, and rural areas. The breadth of geographic locations, the declining number of VA facilities offering gynecologic surgical services, and the growing population of female veterans present unique challenges to providing accessible and comparable health care to these female patients.

VA district 4 (Continental) has the lowest population density as well as the lowest VA hysterectomy rate in FY 2014, which may be attributable to the aforementioned challenges. As a result of these challenges, an increasing number of gynecologic surgical referrals to non-VA facilities was observed during the study period. The VA has made considerable progress in supporting and promoting health care for women by strategically enhancing services and access for women veterans. Although the number of hysterectomies has increased across VA facilities offering gynecologic surgical services, about 1 in 3 women veterans are referred to non-VA facilities for their gynecologic surgical needs. The VA has a challenging opportunity to expand gynecologic surgical services and improve access for the growing population of women veterans. To accommodate this growth, the VA may consider strategically increasing the number of facilities providing gynecologic surgical services or expanding established gynecologic surgical departments.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Unique veteran users profile FY 2015. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Unique_Veteran_Users_2015.pdf. Published December 2016. Accessed August 24, 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hysterectomy surveillance - United States, 1994-1999. Malaria surveillance - United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep; 2002;55(SS-5):1-28. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/13513/Share. Published July 12, 2002. Accessed August 24, 2017.

3. AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. AAGL position statement: route of hysterectomy to treat benign uterine disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(1):1-3.

4. [No authors listed]. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444: choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(5):1156-1158.

5. Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S, et al. The eVALuate study: two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. BMJ. 2004;328:129.

6. Marana R, Busacca M, Zupi E, Garcea N, Paparella P, Catalano GF. Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2, pt 1):270-275.

7. Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(8):CD003677.

8. Weaver F, Hynes D, Goldberg JM, Khuri S, Daley J, Henderson W. Hysterectomy in Veterans Affairs medical centers. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):88-94.

9. Desai VB, Xu X. An update on inpatient hysterectomy routes in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(5):742-743.

10. Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(5):1091-1095.

11. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Study of barriers for women veterans to VA health care. Final report 2015. http://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/Womens%20Health%20Services_Barriers%20to%20Care%20Final%20Report_April2015.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed August 24, 2017

The VA operates the largest integrated health care system in the country, consisting of 144 hospitals and 1,221 outpatient clinics. This system provides medical care for about 22 million veterans. In 2015, women accounted for nearly 10% of the veteran population and are expected to increase to about 16% by 2040.1 With an expected population increase of 18,000 per year over the next 10 years, women are the fastest growing group of veterans.

The VA acknowledges that women are an integral part of the veteran community and that a paradigm shift must occur to meet their unique health needs. Although clinical services specific to women veterans’ health needs have been introduced within the VA, gynecologic surgical services must be addressed in order to improve access and provide comprehensive women’s health care within the VA system.

About 600,000 hysterectomies are performed annually in the U.S., making this procedure one of the most commonly performed in women.2 Over the past 30 years, technologic advances have allowed surgeons to perform more hysterectomies via minimally invasive methods. Both the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists have published consensus statements that minimally invasive hysterectomy should be the standard of care.3,4 Studies in non-VA facilities have shown that practice patterns in the route of hysterectomy have evolved with the advancement of surgical equipment and techniques.

It is uncertain, however, whether these changes in practice patterns exist in the VA, because there are limited published data. Given the frequency of hysterectomies in the U.S., the rate and route of this procedure are easily identifiable measures that can be evaluated and utilized as a comparison model for health care received within the VA vs the civilian sector.

The aim of this study was to assess the changes in rate and surgical approach to benign hysterectomy for women veterans at VAMCs and referrals to non-VA facilities over a 10-year period. The authors’ hypothesis was that a minimally invasive approach would be more common in recent years. This study also compares published national data to evaluate whether the VA is offering comparable surgical services to the civilian sector.

Methods

The institutional review boards of Indiana University and the Richard L. Roudebush VAMC in Indianapolis, Indiana, approved this retrospective cross-sectional study. The VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) authorized access to VA database information.

All women veterans who underwent hysterectomy for benign indications from fiscal years (FY) 2005 to 2014 were included. In order to identify this group, the authors queried the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and the Non-VA Care Cube for all hysterectomy current procedural terminology (CPT) codes typically performed for benign indications, including 58150, 58152, 58180, 58260, 58262, 58263, 58267, 58270, 58290, 58291, 58292, 58293, 58294, 58541, 58542, 58543, 58544, 58550, 58552, 58553, 58554, 58570, 58571, 58572, and 58573. For each patient identified, the following variables were collected: date of the procedure, facility location, primary CPT code, primary ICD-9 code, and patient age. Patients whose primary ICD-9 code was for a malignancy of gynecologic origin were excluded from the study.

The CDW is a national database collected by the VA Office of Information and Technology to provide clinical data for VA analytical purposes. The Non-VA Care Cube identifies services purchased for veterans with non-VA care dollars and, therefore, captures women veterans who were referred outside the VA for a hysterectomy. Additional data collected include age, gender, hospital complexity, place of care, payment location, primary CPT, primary ICD-9, and several other parameters. The annual number of women veterans accessing VA health care was extracted from the VSSC Unique Patients Cube.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy was defined as total laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, laparoscopic-supracervical hysterectomy, and robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy. Minimally invasive hysterectomy was defined as all laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies.

Frequency distributions between categoric variables were compared using chi-squared tests. The population-adjusted hysterectomy rates were estimated by dividing the total number of hysterectomies by the number of women veterans accessing VA medical care. Hysterectomy rates are reported as rate per 1,000 women per year. A time trend analysis was performed with linear regression to evaluate the slopes of trends for each route of hysterectomy, using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Redmond, WA). The authors analyzed the relationship between route of hysterectomy and fiscal year, using a multivariable logistic regression that was adjusted for age, district, and surgical diagnosis. The adjusted relative risk (RR) for each type of hysterectomy was reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 (Chicago, IL) with P < .05 defined as being statistically significant.To ensure the accuracy of the CDW data, the documented CPT and ICD-9 codes were compared between the CDW and the VA electronic medical records (EMR) for 400 charts selected at random. This cohort represents about 5% of the total charts and was felt to be an adequate measure of the entire sample since the CPT and ICD-9 codes were verified and matched 100% of the time. Demographic and descriptive data regarding body mass index, level of education, race, smoking status, medical comorbidities, and surgical history were excluded from the study because it was either not available or not consistently reported within the CDW.

Results

A retrospective query of the CDW identified 8,327 hysterectomies performed at the VA for benign indications from fiscal year (FY) 2005 to FY 2014. The total number of annual hysterectomies at the VA increased 30.7% from 710 in FY 2004 to 1,025 in FY 2014. The annual number of women veterans who accessed VA health care increased 30.8% from 412,271 to 596,011 during the same time frame. Thus, the population adjusted hysterectomy rate remained stable at 1.72 (Figure 1).

The authors also analyzed the VA data by district and decided to highlight the most recent data trends, as this is most applicable to how the VA currently operates. During FY 2014, the VA hysterectomy rates were as follows: district 1 (North Atlantic) 1.52; district 2 (Southeast) 2.21; district 3 (Midwest) 1.47; district 4 (Continental) 1.43; and district 5 (Pacific) 1.64 (Figure 2)

During the study period, calculated hysterectomy rates based on route at the VA showed that the laparoscopic hysterectomy rate increased from 0.11 to 0.53, the vaginal hysterectomy rate remained relatively stable at 0.34 to 0.37, and the abdominal hysterectomy rate declined from 1.28 to 0.8 (Figure 3).

Discussion

Although the total hysterectomy rate within the VA remained stable during the study period, the minimally invasive hysterectomy rate increased significantly. In FY 2014, the majority of hysterectomies at the VA were performed via a minimally invasive approach. Minimally invasive hysterectomy has many recognized advantages over abdominal hysterectomy as it offers a significant reduction in postoperative pain, narcotic use, length of stay, intraoperative blood loss, fever, deep venous thrombosis, and a faster recovery with return to baseline functioning thus improving overall quality of life.5-7 Previous literature of VA hysterectomy data from 1991 to 1997 reported an abdominal hysterectomy percentage of 74%, vaginal hysterectomy percentage of 22%, and laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy percentage of 4%.8

Additionally, previous literature of the civilian sector reported a national laparoscopic hysterectomy percentage of 32.4% in 2012, which is comparable to the laparoscopic hysterectomy percentage found in this study.9,10 These data highlight the growth of laparoscopic hysterectomy at the VA, which is comparable to that of the civilian sector.The Nationwide Inpatient Sample reported an abdominal hysterectomy percentage of 66.1% in 2003 and 52.8% in 2012.9,10 The authors observed a similar decline in the abdominal hysterectomy rate at the VA over the period studied. Although many factors may have contributed to this decline, the growth of laparoscopic hysterectomy was a possible contributing factor since the vaginal hysterectomy rate remained stable over the study period. Future studies are needed to evaluate surgical complications and readmission rates in order to more accurately assess the quality of gynecologic surgical care provided by the VA compared with the civilian sector.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several important strengths. First, the large sample size from VA nationwide databases included information from all VAMC performing hysterectomies. Second, this study included 10 years of data, with the latest data from 2014, allowing for depiction of both long-term and recent trends.

Potential issues with large databases such as the CDW and the Non-VA Care Cube included inaccurate coding of procedures and diagnoses as well as missing data. This possible limitation was addressed by randomly selecting 400 patients in the database to verify the database information against the patient’s EMR, which matched 100% of the time. In addition, the authors calculated the hysterectomy rates using a denominator based on all women veterans accessing VA health care, which included women who had previously had a hysterectomy. Therefore, the true hysterectomy rate may have been underestimated.

Conclusion

The VA operates the largest health care system in the U.S. with more than 500,000 women veterans currently utilizing VA health care.11 The VA provides services to women veterans living in urban, suburban, and rural areas. The breadth of geographic locations, the declining number of VA facilities offering gynecologic surgical services, and the growing population of female veterans present unique challenges to providing accessible and comparable health care to these female patients.

VA district 4 (Continental) has the lowest population density as well as the lowest VA hysterectomy rate in FY 2014, which may be attributable to the aforementioned challenges. As a result of these challenges, an increasing number of gynecologic surgical referrals to non-VA facilities was observed during the study period. The VA has made considerable progress in supporting and promoting health care for women by strategically enhancing services and access for women veterans. Although the number of hysterectomies has increased across VA facilities offering gynecologic surgical services, about 1 in 3 women veterans are referred to non-VA facilities for their gynecologic surgical needs. The VA has a challenging opportunity to expand gynecologic surgical services and improve access for the growing population of women veterans. To accommodate this growth, the VA may consider strategically increasing the number of facilities providing gynecologic surgical services or expanding established gynecologic surgical departments.

The VA operates the largest integrated health care system in the country, consisting of 144 hospitals and 1,221 outpatient clinics. This system provides medical care for about 22 million veterans. In 2015, women accounted for nearly 10% of the veteran population and are expected to increase to about 16% by 2040.1 With an expected population increase of 18,000 per year over the next 10 years, women are the fastest growing group of veterans.

The VA acknowledges that women are an integral part of the veteran community and that a paradigm shift must occur to meet their unique health needs. Although clinical services specific to women veterans’ health needs have been introduced within the VA, gynecologic surgical services must be addressed in order to improve access and provide comprehensive women’s health care within the VA system.

About 600,000 hysterectomies are performed annually in the U.S., making this procedure one of the most commonly performed in women.2 Over the past 30 years, technologic advances have allowed surgeons to perform more hysterectomies via minimally invasive methods. Both the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and American Association of Gynecologic Laparoscopists have published consensus statements that minimally invasive hysterectomy should be the standard of care.3,4 Studies in non-VA facilities have shown that practice patterns in the route of hysterectomy have evolved with the advancement of surgical equipment and techniques.

It is uncertain, however, whether these changes in practice patterns exist in the VA, because there are limited published data. Given the frequency of hysterectomies in the U.S., the rate and route of this procedure are easily identifiable measures that can be evaluated and utilized as a comparison model for health care received within the VA vs the civilian sector.

The aim of this study was to assess the changes in rate and surgical approach to benign hysterectomy for women veterans at VAMCs and referrals to non-VA facilities over a 10-year period. The authors’ hypothesis was that a minimally invasive approach would be more common in recent years. This study also compares published national data to evaluate whether the VA is offering comparable surgical services to the civilian sector.

Methods

The institutional review boards of Indiana University and the Richard L. Roudebush VAMC in Indianapolis, Indiana, approved this retrospective cross-sectional study. The VHA Support Service Center (VSSC) authorized access to VA database information.

All women veterans who underwent hysterectomy for benign indications from fiscal years (FY) 2005 to 2014 were included. In order to identify this group, the authors queried the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW) and the Non-VA Care Cube for all hysterectomy current procedural terminology (CPT) codes typically performed for benign indications, including 58150, 58152, 58180, 58260, 58262, 58263, 58267, 58270, 58290, 58291, 58292, 58293, 58294, 58541, 58542, 58543, 58544, 58550, 58552, 58553, 58554, 58570, 58571, 58572, and 58573. For each patient identified, the following variables were collected: date of the procedure, facility location, primary CPT code, primary ICD-9 code, and patient age. Patients whose primary ICD-9 code was for a malignancy of gynecologic origin were excluded from the study.

The CDW is a national database collected by the VA Office of Information and Technology to provide clinical data for VA analytical purposes. The Non-VA Care Cube identifies services purchased for veterans with non-VA care dollars and, therefore, captures women veterans who were referred outside the VA for a hysterectomy. Additional data collected include age, gender, hospital complexity, place of care, payment location, primary CPT, primary ICD-9, and several other parameters. The annual number of women veterans accessing VA health care was extracted from the VSSC Unique Patients Cube.

Laparoscopic hysterectomy was defined as total laparoscopic hysterectomy, laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, laparoscopic-supracervical hysterectomy, and robotic-assisted laparoscopic hysterectomy. Minimally invasive hysterectomy was defined as all laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies.

Frequency distributions between categoric variables were compared using chi-squared tests. The population-adjusted hysterectomy rates were estimated by dividing the total number of hysterectomies by the number of women veterans accessing VA medical care. Hysterectomy rates are reported as rate per 1,000 women per year. A time trend analysis was performed with linear regression to evaluate the slopes of trends for each route of hysterectomy, using Microsoft Excel 2010 (Redmond, WA). The authors analyzed the relationship between route of hysterectomy and fiscal year, using a multivariable logistic regression that was adjusted for age, district, and surgical diagnosis. The adjusted relative risk (RR) for each type of hysterectomy was reported with 95% confidence intervals (CI). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 12.0 (Chicago, IL) with P < .05 defined as being statistically significant.To ensure the accuracy of the CDW data, the documented CPT and ICD-9 codes were compared between the CDW and the VA electronic medical records (EMR) for 400 charts selected at random. This cohort represents about 5% of the total charts and was felt to be an adequate measure of the entire sample since the CPT and ICD-9 codes were verified and matched 100% of the time. Demographic and descriptive data regarding body mass index, level of education, race, smoking status, medical comorbidities, and surgical history were excluded from the study because it was either not available or not consistently reported within the CDW.

Results

A retrospective query of the CDW identified 8,327 hysterectomies performed at the VA for benign indications from fiscal year (FY) 2005 to FY 2014. The total number of annual hysterectomies at the VA increased 30.7% from 710 in FY 2004 to 1,025 in FY 2014. The annual number of women veterans who accessed VA health care increased 30.8% from 412,271 to 596,011 during the same time frame. Thus, the population adjusted hysterectomy rate remained stable at 1.72 (Figure 1).

The authors also analyzed the VA data by district and decided to highlight the most recent data trends, as this is most applicable to how the VA currently operates. During FY 2014, the VA hysterectomy rates were as follows: district 1 (North Atlantic) 1.52; district 2 (Southeast) 2.21; district 3 (Midwest) 1.47; district 4 (Continental) 1.43; and district 5 (Pacific) 1.64 (Figure 2)

During the study period, calculated hysterectomy rates based on route at the VA showed that the laparoscopic hysterectomy rate increased from 0.11 to 0.53, the vaginal hysterectomy rate remained relatively stable at 0.34 to 0.37, and the abdominal hysterectomy rate declined from 1.28 to 0.8 (Figure 3).

Discussion

Although the total hysterectomy rate within the VA remained stable during the study period, the minimally invasive hysterectomy rate increased significantly. In FY 2014, the majority of hysterectomies at the VA were performed via a minimally invasive approach. Minimally invasive hysterectomy has many recognized advantages over abdominal hysterectomy as it offers a significant reduction in postoperative pain, narcotic use, length of stay, intraoperative blood loss, fever, deep venous thrombosis, and a faster recovery with return to baseline functioning thus improving overall quality of life.5-7 Previous literature of VA hysterectomy data from 1991 to 1997 reported an abdominal hysterectomy percentage of 74%, vaginal hysterectomy percentage of 22%, and laparoscopic assisted vaginal hysterectomy percentage of 4%.8

Additionally, previous literature of the civilian sector reported a national laparoscopic hysterectomy percentage of 32.4% in 2012, which is comparable to the laparoscopic hysterectomy percentage found in this study.9,10 These data highlight the growth of laparoscopic hysterectomy at the VA, which is comparable to that of the civilian sector.The Nationwide Inpatient Sample reported an abdominal hysterectomy percentage of 66.1% in 2003 and 52.8% in 2012.9,10 The authors observed a similar decline in the abdominal hysterectomy rate at the VA over the period studied. Although many factors may have contributed to this decline, the growth of laparoscopic hysterectomy was a possible contributing factor since the vaginal hysterectomy rate remained stable over the study period. Future studies are needed to evaluate surgical complications and readmission rates in order to more accurately assess the quality of gynecologic surgical care provided by the VA compared with the civilian sector.

Strengths and Limitations

This study has several important strengths. First, the large sample size from VA nationwide databases included information from all VAMC performing hysterectomies. Second, this study included 10 years of data, with the latest data from 2014, allowing for depiction of both long-term and recent trends.

Potential issues with large databases such as the CDW and the Non-VA Care Cube included inaccurate coding of procedures and diagnoses as well as missing data. This possible limitation was addressed by randomly selecting 400 patients in the database to verify the database information against the patient’s EMR, which matched 100% of the time. In addition, the authors calculated the hysterectomy rates using a denominator based on all women veterans accessing VA health care, which included women who had previously had a hysterectomy. Therefore, the true hysterectomy rate may have been underestimated.

Conclusion

The VA operates the largest health care system in the U.S. with more than 500,000 women veterans currently utilizing VA health care.11 The VA provides services to women veterans living in urban, suburban, and rural areas. The breadth of geographic locations, the declining number of VA facilities offering gynecologic surgical services, and the growing population of female veterans present unique challenges to providing accessible and comparable health care to these female patients.

VA district 4 (Continental) has the lowest population density as well as the lowest VA hysterectomy rate in FY 2014, which may be attributable to the aforementioned challenges. As a result of these challenges, an increasing number of gynecologic surgical referrals to non-VA facilities was observed during the study period. The VA has made considerable progress in supporting and promoting health care for women by strategically enhancing services and access for women veterans. Although the number of hysterectomies has increased across VA facilities offering gynecologic surgical services, about 1 in 3 women veterans are referred to non-VA facilities for their gynecologic surgical needs. The VA has a challenging opportunity to expand gynecologic surgical services and improve access for the growing population of women veterans. To accommodate this growth, the VA may consider strategically increasing the number of facilities providing gynecologic surgical services or expanding established gynecologic surgical departments.

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Unique veteran users profile FY 2015. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Unique_Veteran_Users_2015.pdf. Published December 2016. Accessed August 24, 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hysterectomy surveillance - United States, 1994-1999. Malaria surveillance - United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep; 2002;55(SS-5):1-28. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/13513/Share. Published July 12, 2002. Accessed August 24, 2017.

3. AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. AAGL position statement: route of hysterectomy to treat benign uterine disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(1):1-3.

4. [No authors listed]. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444: choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(5):1156-1158.

5. Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S, et al. The eVALuate study: two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. BMJ. 2004;328:129.

6. Marana R, Busacca M, Zupi E, Garcea N, Paparella P, Catalano GF. Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2, pt 1):270-275.

7. Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(8):CD003677.

8. Weaver F, Hynes D, Goldberg JM, Khuri S, Daley J, Henderson W. Hysterectomy in Veterans Affairs medical centers. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):88-94.

9. Desai VB, Xu X. An update on inpatient hysterectomy routes in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(5):742-743.

10. Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(5):1091-1095.

11. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Study of barriers for women veterans to VA health care. Final report 2015. http://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/Womens%20Health%20Services_Barriers%20to%20Care%20Final%20Report_April2015.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed August 24, 2017

1. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Veterans Analysis and Statistics. Unique veteran users profile FY 2015. https://www.va.gov/vetdata/docs/SpecialReports/Profile_of_Unique_Veteran_Users_2015.pdf. Published December 2016. Accessed August 24, 2017.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Hysterectomy surveillance - United States, 1994-1999. Malaria surveillance - United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep; 2002;55(SS-5):1-28. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/13513/Share. Published July 12, 2002. Accessed August 24, 2017.

3. AAGL Advancing Minimally Invasive Gynecology Worldwide. AAGL position statement: route of hysterectomy to treat benign uterine disease. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18(1):1-3.

4. [No authors listed]. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444: choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114(5):1156-1158.

5. Garry R, Fountain J, Mason S, et al. The eVALuate study: two parallel randomised trials, one comparing laparoscopic with abdominal hysterectomy, the other comparing laparoscopic with vaginal hysterectomy. BMJ. 2004;328:129.

6. Marana R, Busacca M, Zupi E, Garcea N, Paparella P, Catalano GF. Laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy versus total abdominal hysterectomy: a prospective, randomized, multicenter study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180(2, pt 1):270-275.

7. Aarts JW, Nieboer TE, Johnson N, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015(8):CD003677.

8. Weaver F, Hynes D, Goldberg JM, Khuri S, Daley J, Henderson W. Hysterectomy in Veterans Affairs medical centers. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97(6):88-94.

9. Desai VB, Xu X. An update on inpatient hysterectomy routes in the United States. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213(5):742-743.

10. Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110(5):1091-1095.

11. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Study of barriers for women veterans to VA health care. Final report 2015. http://www.womenshealth.va.gov/WOMENSHEALTH/docs/Womens%20Health%20Services_Barriers%20to%20Care%20Final%20Report_April2015.pdf. Published April 2015. Accessed August 24, 2017

Coaching Supports Patient Aligned Care Teams

In 2010, the VHA implemented the patient-centered medical home model of primary care health care as part of its transformational T-21 Initiatives.1 Now known as Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), the key pillars of the model include the expanded roles and responsibilities of multidisciplinary care teams who provide enhanced access and coordinated care. This model is based on a foundation of adequate resources, patient centeredness, and process improvement (Figure 1).

The national implementation strategy consisted of an initial educational conference with 3,600 attendees. The conference included a series of PACT learning collaboratives that engaged > 300 primary care teams, 5 demonstration laboratories, and educational outreach through learning centers and on-site consultations. Despite an aggressive national implementation plan, many frontline primary care teams struggled to translate the medical home theory into process.

Background

The Richard L. Roudebush VAMC (RLRVAMC) is a large tertiary medical center providing care to > 44,000 primary care patients. This care is delivered by 58 primary care physicians (PCPs) in 5 hospital-based outpatient clinics, including 1 large teaching clinic, 3 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), and a clinic that serves recently returned active-duty veterans. Administrative nursing and clerical associates report to the Office of Ambulatory Care, and physicians and nurse practitioners report to the Medicine Service. Before the implementation of the PACT model, the functional unit of primary care was an entire clinic, typically consisting of 4 to 10 PCPs, nurses, and clerical associates.

Discussions about process change had previously occurred through monthly service or clinic meetings in which administrative leaders provided direction to frontline staff. This culture of top-down leadership drove process change but was not always effective and empowering for practice change. With the implementation of PACT, the functional unit of primary care shifted from the larger clinic to a team composed of a PCP, a nurse, a licensed nurse practitioner or health technician, and a clerical associate.

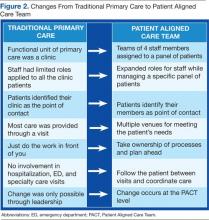

The care delivery system fundamentally changed from the traditional model to a medical home model (Figure 2). This group now represented the fundamental clinical microsystem for the delivery of primary care within the VA medical home model.2 The experience of Batalden and colleagues at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center suggests that such microsystems are very effective units of change.3 The key challenge presented to the primary care leadership was how to link these clinical PACT microsystems with an effective process that would guide practice redesign.

The concept of practice coaching or facilitation as a mechanism for physician offices to adopt evidence-based medicine and quality improvement dates to the early 1980s in England. This model spread to the U.S. in the 1990s and has continued to be used as a mechanism for leading clinical practice redesign.4 In traditional practice facilitation, a trained individual is brought in from outside the practice to help adopt evidence-based medicine guidelines.5 This individual works with the practice to implement changes that translate into patient outcome improvements.

Unlike consultation, this facilitator maintains a long-term relationship with the team as they work together to achieve goals. More important, the facilitator assists the team in developing improvement processes that are sustainable as they become incorporated within the fabric of the team culture and remain after the coach is gone. There are several reviews of clinical practice coaching that support its effectiveness in implementing evidence-based primary care guidelines.6,7 The Affordable Care Act contains provisions for the use of this model in promoting best practices and quality care.8 Manuals developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality outline how to develop a practice facilitation program.9,10

Related: Infusing Gerontologic Practice Into PACT

Essential to all practice facilitation models is the effective use of quality improvement tools. The RLRVAMC adopted the VHA Lean Healthcare Improvement Framework, which includes an approach for rapid cycle change.

The RLRVAMC adopted the facilitative coaching model in November 2011, using internal coaches who were assigned to the fundamental microsystem of its medical home.

Coach Selection

Many facilitative coaching models described in the literature use external coaches. Frequently cited advantages of external coaches include having dedicated time, receiving standardized training in facilitation, and being regarded as neutral to internal conflicts. The RLRVAMC staff elected to identify internal coaches. Advantages of this approach include the use of existing resources, the ability to develop long-term continuous relationships with PACTs, and the ability to access key internal resources to assist the team. Also, using internal individuals holding primary care leadership positions was critical to the coaching model.

Thirty-eight PACTs were initially created, and 15 internal coaches were identified. These individuals included the associate chief of staff of Ambulatory Care, chief nurse for Clinic Operations, business administrators in primary care, and all frontline unit managers and supervisors. This level of management involvement provided content expertise about primary care operations and equally important, carried the authority to implement change.

Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans

In addition, this approach provided considerable leadership credibility among frontline PACT staff. Given the large number of PACTs requiring coaching, coach recruitment was expanded to include other primary care administrative staff, such as the leads for the CBOCs, Prevention and Behavioral Health programs, System Redesign, and Telehealth Services. The most recent phase has included registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, health technicians, and physicians from high- functioning PACT teams who have experienced the process and who can now devote time to being coaches.

Qulifications and Training

Although the literature suggests multiple qualifications for practice coaches, there is a general agreement regarding core skills for strong facilitation, which includes interpersonal skills, knowledge of process improvement techniques, and an understanding of data acquisition and analysis.10 Strong interpersonal skills are often inherent but are a critical factor in motivating team members and managing conflicts that arise. Potential coaches were not selected if these skills were poorly developed.

The authors’ experiences have shown that although content knowledge about primary care operations is very helpful, it is not essential to being an effective coach. The facilitation model that was adopted for the program, as described by Bens, focuses predominately on process and not content expertise.11 The facilitator’s role is to apply a structural framework; ie, methods and tools that capitalize on content knowledge of frontline staff in identifying changes needed to implement the medical home.

Related: Updates in Specialty Care

Also, although knowledge of primary care operations was not required, formal training in understanding the goals of the medical home and the metrics related to PACT was essential for successful coaching. All coaches were required to attend PACT training sessions. Coaches were also expected to have basic training or experience in system redesign with the majority of the coaches completing Yellow Belt training, which is an introduction to the methods of process improvement through the lean thinking business model. A coaching manual was developed that contained information related to meeting structures, data definitions, extraction, and interpretation. A coaching website was developed that provided links to data sources and definitions. PACT-related tools, such as instructions on conducting group visits, phone visits, and use of population management were disseminated.

Coach-Team Meeting Structure

Coaches were assigned to teams by matching the skills of the coach with the team needs. Initially, sessions were held weekly for 1 hour, though this typically evolved into biweekly meetings. Clinic schedules were blocked, allowing PACTs the time to meet with their coaches. A ratio of 1 coach to 2 PACTs was considered optimal for individualized team meetings. The exceptions were the CBOCs, where several teams met together due to the need for coaches to travel. Meetings were held away from clinical areas to avoid distractions. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were used to plan and implement process improvements. The average time commitment for a coach assigned to 2 teams was between 2 to 4 hours a week.

The initial coaching sessions tended to be more structured, clearly defining the coach role, developing team building, identifying the goals, and outlining process improvement tools. Common challenges for the coaches were keeping teams focused and optimally managing time by preventing prolonged conversations unrelated to process improvement. Many frontline staff had never been empowered to change their practices, so their initial reaction was to focus on problems and not solutions. Once team relationships were established, the strong influence of nursing or clerical associates exerted on the PCP’ s willingness to change became evident and a key factor for success. Often the leaders of change are not the physicians, highlighting the influence of team building and the willingness of individuals to change practice due to team relationships and not by authority.12

Data Use

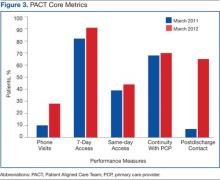

Before the implementation of this model, PACT data and metrics were posted in the clinics and briefly discussed at service-level meetings. However, this data-sharing approach rarely generated team members’ interest. By using coaching, personalized data reports that displayed team-specific information in comparison to the overall service and national VA goals were found to be a more effective technique for sharing data and performance metrics. National VA PACT core metrics tracked the following: (1) percentage of same-day appointments with PCP ratio—target 70%; (2) ratio of nontraditional encounters—target 20%; (3) percentage of continuity with PCP—target 77%; and (4) percentage of 2-day contact postdischarge ratio—target 75%. Figure 3 shows the improvements made as a facility from March 2011 (pre-PACT implementation) to March 2012 (post-PACT implementation).

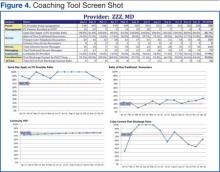

A graphic display of the team’s data, including metrics related to access, continuity, and postdischarge follow-up was reviewed monthly, and the coach provided detailed explanations (Figure 4). Of particular importance to the teams was the ability to individually identify those patients who failed the metric. Review of these “fallouts” at a coaching session often resulted in reliable, consistent process improvements that addressed the failed process.

Coach-to-Coach Meetings

Critical to the RLRVAMC coaching model were the weekly 1-hour coach-to-coach meetings. Most of the coach training occurred during these sessions, either formally or via feedback and discussion. Coaches discussed their teams’ progress, brought back questions from the teams, and sought guidance from one another. Executive leaders, who were also coaches, were present at these meetings and provided the opportunity to implement broader operational changes quickly. Coaches also served as a communication venue for frontline staff to express their concerns to primary care leaders during these meetings.

Limitations

Practice facilitation that uses internal coaches for a clinical PACT microsystem may present several potential challenges. Large primary care practices require a pool of coaches who are willing to commit the necessary time required for successful implementation of this model. Although the coaches dedicate this time as collateral duty, many express that the time spent with their teams is a rewarding experience outside of their administrative roles. The coaches express satisfaction when teams meet their goals and PDSA cycles are successful.

Coaches require significant amounts of training to reach the level of effectiveness required. Teams must realize and appreciate the importance of dedicating time away from the competing priority of patient care.

Implementation of the coaching model for physician trainees in the teaching clinic has not been successful due to the teaching clinic schedule and other issues. Also related to the complexity of the teaching clinic schedule, the coaching model did not significantly improve continuity. Coaches have recently been assigned to the teaching clinic, and each team will be identifying PDSA cycles to approach the implementation of PACT principles.

Conclusion

Despite the aforementioned challenges, the outcomes are clear. The implementation of the coaching model, using internal coaches, resulted in a significant improvement of the ability of the staff to achieve the national PACT metrics (Figure 3). More important, the model created a new structural organization for change within primary care that reversed a culture of top-down leadership to that of team empowerment.

Teams that experienced practice facilitation developed ownership in their processes, data, and performance improvement and now have a more direct mechanism of communicating with primary care leadership. The coaching model moved the teams forward from having received PACT education to having the confidence and tools to implement PACTs. Staff progressed from looking at the data given to them to collecting and interpreting the data themselves. The teams are able to articulate how they fit in to the PACT model and enthusiastically monitor their progress. As primary care moves forward with the medical home, the facilitative coaching model offers a promising option for successful implementation.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Klein S. The Veterans Health Administration: Implementing patient-centered medical homes in the nation’s largest integrated delivery system. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2011;16:1537.

2. Godfrey MM, ed. Clinical Microsystem Action Guide: Improving Health Care by Improving Your Microsystem. Version 2.1. The Dartmouth Institute Website. http://clinicalmicrosys.dartmouth.edu/wp -content/uploads/2014/07/CMAG040104.pdf. Published 2004. Accessed January 23, 2015.

3. Batalden PB, Nelson EC, Edwards WH, Godfrey MM, Mohr JJ. Microsystems in health care: Part 9. Developing a small clinical unit to attain peak performance. Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29(11):575-585.

4. Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, et al. Effect of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(suppl 1):S33-S34, S92.

5. Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Robinson A, Niebauer L, Ford A. Practice facilitators and practice-based research networks. J Am Board Fam Med. 2006;19(5):506-510.

6. Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63-74.

7. Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: A review of the literature. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):581-588.

8. Grumbach K, Bainbridge E, Bodenheimer T. Facilitating improvement in primary care: The promise of practice coaching. Issue Brief (Commonw Fund). 2012;15:1-14.

9. Knox L, Taylor EF, Geonnotti K, et al. Developing and Running a Primary Care Practice Facilitation Program: A How-To Guide. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2011. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0011.

10. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Integrating Chronic Care and Business Strategies in the Safety Net: A Practice Coaching Manual. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Website. http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/systems/primary-care /coachmnl/index.html. Published December 2012. Accessed February 26, 2015.

11. Bens I. Facilitation With Ease! Core Skills for Facilitators, Team Leaders and Members, Managers, Consultants and Trainers. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2005.

12. Bodenheimer T. Building Teams in Primary Care: Lessons Learned: Part 1 and 2. Oakland, CA: California Health Care Foundation; July 2007.

In 2010, the VHA implemented the patient-centered medical home model of primary care health care as part of its transformational T-21 Initiatives.1 Now known as Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), the key pillars of the model include the expanded roles and responsibilities of multidisciplinary care teams who provide enhanced access and coordinated care. This model is based on a foundation of adequate resources, patient centeredness, and process improvement (Figure 1).

The national implementation strategy consisted of an initial educational conference with 3,600 attendees. The conference included a series of PACT learning collaboratives that engaged > 300 primary care teams, 5 demonstration laboratories, and educational outreach through learning centers and on-site consultations. Despite an aggressive national implementation plan, many frontline primary care teams struggled to translate the medical home theory into process.

Background

The Richard L. Roudebush VAMC (RLRVAMC) is a large tertiary medical center providing care to > 44,000 primary care patients. This care is delivered by 58 primary care physicians (PCPs) in 5 hospital-based outpatient clinics, including 1 large teaching clinic, 3 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), and a clinic that serves recently returned active-duty veterans. Administrative nursing and clerical associates report to the Office of Ambulatory Care, and physicians and nurse practitioners report to the Medicine Service. Before the implementation of the PACT model, the functional unit of primary care was an entire clinic, typically consisting of 4 to 10 PCPs, nurses, and clerical associates.

Discussions about process change had previously occurred through monthly service or clinic meetings in which administrative leaders provided direction to frontline staff. This culture of top-down leadership drove process change but was not always effective and empowering for practice change. With the implementation of PACT, the functional unit of primary care shifted from the larger clinic to a team composed of a PCP, a nurse, a licensed nurse practitioner or health technician, and a clerical associate.

The care delivery system fundamentally changed from the traditional model to a medical home model (Figure 2). This group now represented the fundamental clinical microsystem for the delivery of primary care within the VA medical home model.2 The experience of Batalden and colleagues at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center suggests that such microsystems are very effective units of change.3 The key challenge presented to the primary care leadership was how to link these clinical PACT microsystems with an effective process that would guide practice redesign.

The concept of practice coaching or facilitation as a mechanism for physician offices to adopt evidence-based medicine and quality improvement dates to the early 1980s in England. This model spread to the U.S. in the 1990s and has continued to be used as a mechanism for leading clinical practice redesign.4 In traditional practice facilitation, a trained individual is brought in from outside the practice to help adopt evidence-based medicine guidelines.5 This individual works with the practice to implement changes that translate into patient outcome improvements.

Unlike consultation, this facilitator maintains a long-term relationship with the team as they work together to achieve goals. More important, the facilitator assists the team in developing improvement processes that are sustainable as they become incorporated within the fabric of the team culture and remain after the coach is gone. There are several reviews of clinical practice coaching that support its effectiveness in implementing evidence-based primary care guidelines.6,7 The Affordable Care Act contains provisions for the use of this model in promoting best practices and quality care.8 Manuals developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality outline how to develop a practice facilitation program.9,10

Related: Infusing Gerontologic Practice Into PACT

Essential to all practice facilitation models is the effective use of quality improvement tools. The RLRVAMC adopted the VHA Lean Healthcare Improvement Framework, which includes an approach for rapid cycle change.

The RLRVAMC adopted the facilitative coaching model in November 2011, using internal coaches who were assigned to the fundamental microsystem of its medical home.

Coach Selection

Many facilitative coaching models described in the literature use external coaches. Frequently cited advantages of external coaches include having dedicated time, receiving standardized training in facilitation, and being regarded as neutral to internal conflicts. The RLRVAMC staff elected to identify internal coaches. Advantages of this approach include the use of existing resources, the ability to develop long-term continuous relationships with PACTs, and the ability to access key internal resources to assist the team. Also, using internal individuals holding primary care leadership positions was critical to the coaching model.

Thirty-eight PACTs were initially created, and 15 internal coaches were identified. These individuals included the associate chief of staff of Ambulatory Care, chief nurse for Clinic Operations, business administrators in primary care, and all frontline unit managers and supervisors. This level of management involvement provided content expertise about primary care operations and equally important, carried the authority to implement change.

Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans

In addition, this approach provided considerable leadership credibility among frontline PACT staff. Given the large number of PACTs requiring coaching, coach recruitment was expanded to include other primary care administrative staff, such as the leads for the CBOCs, Prevention and Behavioral Health programs, System Redesign, and Telehealth Services. The most recent phase has included registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, health technicians, and physicians from high- functioning PACT teams who have experienced the process and who can now devote time to being coaches.

Qulifications and Training

Although the literature suggests multiple qualifications for practice coaches, there is a general agreement regarding core skills for strong facilitation, which includes interpersonal skills, knowledge of process improvement techniques, and an understanding of data acquisition and analysis.10 Strong interpersonal skills are often inherent but are a critical factor in motivating team members and managing conflicts that arise. Potential coaches were not selected if these skills were poorly developed.

The authors’ experiences have shown that although content knowledge about primary care operations is very helpful, it is not essential to being an effective coach. The facilitation model that was adopted for the program, as described by Bens, focuses predominately on process and not content expertise.11 The facilitator’s role is to apply a structural framework; ie, methods and tools that capitalize on content knowledge of frontline staff in identifying changes needed to implement the medical home.

Related: Updates in Specialty Care

Also, although knowledge of primary care operations was not required, formal training in understanding the goals of the medical home and the metrics related to PACT was essential for successful coaching. All coaches were required to attend PACT training sessions. Coaches were also expected to have basic training or experience in system redesign with the majority of the coaches completing Yellow Belt training, which is an introduction to the methods of process improvement through the lean thinking business model. A coaching manual was developed that contained information related to meeting structures, data definitions, extraction, and interpretation. A coaching website was developed that provided links to data sources and definitions. PACT-related tools, such as instructions on conducting group visits, phone visits, and use of population management were disseminated.

Coach-Team Meeting Structure

Coaches were assigned to teams by matching the skills of the coach with the team needs. Initially, sessions were held weekly for 1 hour, though this typically evolved into biweekly meetings. Clinic schedules were blocked, allowing PACTs the time to meet with their coaches. A ratio of 1 coach to 2 PACTs was considered optimal for individualized team meetings. The exceptions were the CBOCs, where several teams met together due to the need for coaches to travel. Meetings were held away from clinical areas to avoid distractions. Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles were used to plan and implement process improvements. The average time commitment for a coach assigned to 2 teams was between 2 to 4 hours a week.

The initial coaching sessions tended to be more structured, clearly defining the coach role, developing team building, identifying the goals, and outlining process improvement tools. Common challenges for the coaches were keeping teams focused and optimally managing time by preventing prolonged conversations unrelated to process improvement. Many frontline staff had never been empowered to change their practices, so their initial reaction was to focus on problems and not solutions. Once team relationships were established, the strong influence of nursing or clerical associates exerted on the PCP’ s willingness to change became evident and a key factor for success. Often the leaders of change are not the physicians, highlighting the influence of team building and the willingness of individuals to change practice due to team relationships and not by authority.12

Data Use

Before the implementation of this model, PACT data and metrics were posted in the clinics and briefly discussed at service-level meetings. However, this data-sharing approach rarely generated team members’ interest. By using coaching, personalized data reports that displayed team-specific information in comparison to the overall service and national VA goals were found to be a more effective technique for sharing data and performance metrics. National VA PACT core metrics tracked the following: (1) percentage of same-day appointments with PCP ratio—target 70%; (2) ratio of nontraditional encounters—target 20%; (3) percentage of continuity with PCP—target 77%; and (4) percentage of 2-day contact postdischarge ratio—target 75%. Figure 3 shows the improvements made as a facility from March 2011 (pre-PACT implementation) to March 2012 (post-PACT implementation).

A graphic display of the team’s data, including metrics related to access, continuity, and postdischarge follow-up was reviewed monthly, and the coach provided detailed explanations (Figure 4). Of particular importance to the teams was the ability to individually identify those patients who failed the metric. Review of these “fallouts” at a coaching session often resulted in reliable, consistent process improvements that addressed the failed process.

Coach-to-Coach Meetings

Critical to the RLRVAMC coaching model were the weekly 1-hour coach-to-coach meetings. Most of the coach training occurred during these sessions, either formally or via feedback and discussion. Coaches discussed their teams’ progress, brought back questions from the teams, and sought guidance from one another. Executive leaders, who were also coaches, were present at these meetings and provided the opportunity to implement broader operational changes quickly. Coaches also served as a communication venue for frontline staff to express their concerns to primary care leaders during these meetings.

Limitations

Practice facilitation that uses internal coaches for a clinical PACT microsystem may present several potential challenges. Large primary care practices require a pool of coaches who are willing to commit the necessary time required for successful implementation of this model. Although the coaches dedicate this time as collateral duty, many express that the time spent with their teams is a rewarding experience outside of their administrative roles. The coaches express satisfaction when teams meet their goals and PDSA cycles are successful.

Coaches require significant amounts of training to reach the level of effectiveness required. Teams must realize and appreciate the importance of dedicating time away from the competing priority of patient care.

Implementation of the coaching model for physician trainees in the teaching clinic has not been successful due to the teaching clinic schedule and other issues. Also related to the complexity of the teaching clinic schedule, the coaching model did not significantly improve continuity. Coaches have recently been assigned to the teaching clinic, and each team will be identifying PDSA cycles to approach the implementation of PACT principles.

Conclusion

Despite the aforementioned challenges, the outcomes are clear. The implementation of the coaching model, using internal coaches, resulted in a significant improvement of the ability of the staff to achieve the national PACT metrics (Figure 3). More important, the model created a new structural organization for change within primary care that reversed a culture of top-down leadership to that of team empowerment.

Teams that experienced practice facilitation developed ownership in their processes, data, and performance improvement and now have a more direct mechanism of communicating with primary care leadership. The coaching model moved the teams forward from having received PACT education to having the confidence and tools to implement PACTs. Staff progressed from looking at the data given to them to collecting and interpreting the data themselves. The teams are able to articulate how they fit in to the PACT model and enthusiastically monitor their progress. As primary care moves forward with the medical home, the facilitative coaching model offers a promising option for successful implementation.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects— before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

In 2010, the VHA implemented the patient-centered medical home model of primary care health care as part of its transformational T-21 Initiatives.1 Now known as Patient Aligned Care Teams (PACTs), the key pillars of the model include the expanded roles and responsibilities of multidisciplinary care teams who provide enhanced access and coordinated care. This model is based on a foundation of adequate resources, patient centeredness, and process improvement (Figure 1).

The national implementation strategy consisted of an initial educational conference with 3,600 attendees. The conference included a series of PACT learning collaboratives that engaged > 300 primary care teams, 5 demonstration laboratories, and educational outreach through learning centers and on-site consultations. Despite an aggressive national implementation plan, many frontline primary care teams struggled to translate the medical home theory into process.

Background

The Richard L. Roudebush VAMC (RLRVAMC) is a large tertiary medical center providing care to > 44,000 primary care patients. This care is delivered by 58 primary care physicians (PCPs) in 5 hospital-based outpatient clinics, including 1 large teaching clinic, 3 community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs), and a clinic that serves recently returned active-duty veterans. Administrative nursing and clerical associates report to the Office of Ambulatory Care, and physicians and nurse practitioners report to the Medicine Service. Before the implementation of the PACT model, the functional unit of primary care was an entire clinic, typically consisting of 4 to 10 PCPs, nurses, and clerical associates.

Discussions about process change had previously occurred through monthly service or clinic meetings in which administrative leaders provided direction to frontline staff. This culture of top-down leadership drove process change but was not always effective and empowering for practice change. With the implementation of PACT, the functional unit of primary care shifted from the larger clinic to a team composed of a PCP, a nurse, a licensed nurse practitioner or health technician, and a clerical associate.

The care delivery system fundamentally changed from the traditional model to a medical home model (Figure 2). This group now represented the fundamental clinical microsystem for the delivery of primary care within the VA medical home model.2 The experience of Batalden and colleagues at the Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center suggests that such microsystems are very effective units of change.3 The key challenge presented to the primary care leadership was how to link these clinical PACT microsystems with an effective process that would guide practice redesign.

The concept of practice coaching or facilitation as a mechanism for physician offices to adopt evidence-based medicine and quality improvement dates to the early 1980s in England. This model spread to the U.S. in the 1990s and has continued to be used as a mechanism for leading clinical practice redesign.4 In traditional practice facilitation, a trained individual is brought in from outside the practice to help adopt evidence-based medicine guidelines.5 This individual works with the practice to implement changes that translate into patient outcome improvements.

Unlike consultation, this facilitator maintains a long-term relationship with the team as they work together to achieve goals. More important, the facilitator assists the team in developing improvement processes that are sustainable as they become incorporated within the fabric of the team culture and remain after the coach is gone. There are several reviews of clinical practice coaching that support its effectiveness in implementing evidence-based primary care guidelines.6,7 The Affordable Care Act contains provisions for the use of this model in promoting best practices and quality care.8 Manuals developed by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality outline how to develop a practice facilitation program.9,10

Related: Infusing Gerontologic Practice Into PACT

Essential to all practice facilitation models is the effective use of quality improvement tools. The RLRVAMC adopted the VHA Lean Healthcare Improvement Framework, which includes an approach for rapid cycle change.

The RLRVAMC adopted the facilitative coaching model in November 2011, using internal coaches who were assigned to the fundamental microsystem of its medical home.

Coach Selection

Many facilitative coaching models described in the literature use external coaches. Frequently cited advantages of external coaches include having dedicated time, receiving standardized training in facilitation, and being regarded as neutral to internal conflicts. The RLRVAMC staff elected to identify internal coaches. Advantages of this approach include the use of existing resources, the ability to develop long-term continuous relationships with PACTs, and the ability to access key internal resources to assist the team. Also, using internal individuals holding primary care leadership positions was critical to the coaching model.

Thirty-eight PACTs were initially created, and 15 internal coaches were identified. These individuals included the associate chief of staff of Ambulatory Care, chief nurse for Clinic Operations, business administrators in primary care, and all frontline unit managers and supervisors. This level of management involvement provided content expertise about primary care operations and equally important, carried the authority to implement change.

Related: Using H-PACT to Overcome Treatment Obstacles for Homeless Veterans

In addition, this approach provided considerable leadership credibility among frontline PACT staff. Given the large number of PACTs requiring coaching, coach recruitment was expanded to include other primary care administrative staff, such as the leads for the CBOCs, Prevention and Behavioral Health programs, System Redesign, and Telehealth Services. The most recent phase has included registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, health technicians, and physicians from high- functioning PACT teams who have experienced the process and who can now devote time to being coaches.

Qulifications and Training