User login

Strategies for managing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Ms. E, age 23, presents to your office for a routine visit for management of bipolar I disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus. She currently is taking

Ms. E has a history of self-discontinuing medication when adverse events occur. She has been hospitalized twice for psychosis and suicide attempts. Past psychotropic medications that have been discontinued due to adverse effects include ziprasidone (mild abnormal lip movement), olanzapine (ineffective and drowsy), valproic acid (tremor and abdominal discomfort), lithium (rash), and aripiprazole (increased fasting blood sugar and labile mood).

At her appointment today, Ms. E says she is concerned because she has been experiencing galactorrhea for the past 4 weeks. Her prolactin level is 14.4 ng/mL; a normal level for a woman who is not pregnant is <25 ng/mL. However, a repeat prolactin level is obtained, and is found to be elevated at 38 ng/mL.

Prolactin, a polypeptide hormone that is secreted from the pituitary gland, has many functions, including involvement in the synthesis and maintenance of breast milk production, in reproductive behavior, and in luteal function.1,2 Hyperprolactinemia—an elevated prolactin level—is a common endocrinologic disorder of the hypothalamic–pituitary–axis.3 Children, adolescents, premenopausal women, and women in the perinatal period are more vulnerable to medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.4 If not asymptomatic, patients with hyperprolactinemia may experience amenorrhea, galactorrhea, hypogonadism, sexual dysfunction, or infertility.1,4 Chronic hyperprolactinemia may increase the risk for long-term complications, such as decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis, although available evidence has conflicting findings.1

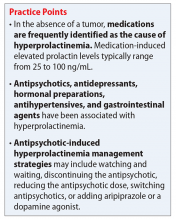

Hyperprolactinemia is diagnosed by a prolactin concentration above the upper reference range.3 Various hormones and neurotransmitters can impact inhibition or stimulation of prolactin release.5 For example, dopamine tonically inhibits prolactin release and synthesis, whereas estrogen stimulates prolactin secretion.1,5 Prolactin also can be elevated under several physiologic and pathologic conditions, such as during stressful situations, meals, or sexual activity.1,5 A prolactin level >250 ng/mL is usually indicative of a prolactinoma; however, some medications, such as strong D2 receptor antagonists (eg, risperidone, haloperidol), can cause significant elevation without evidence of prolactinoma.3 In the absence of a tumor, medications are often identified as the cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 According to the Endocrinology Society clinical practice guideline, medication-induced elevated prolactin levels are typically between 25 to 100 ng/mL.3

Medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

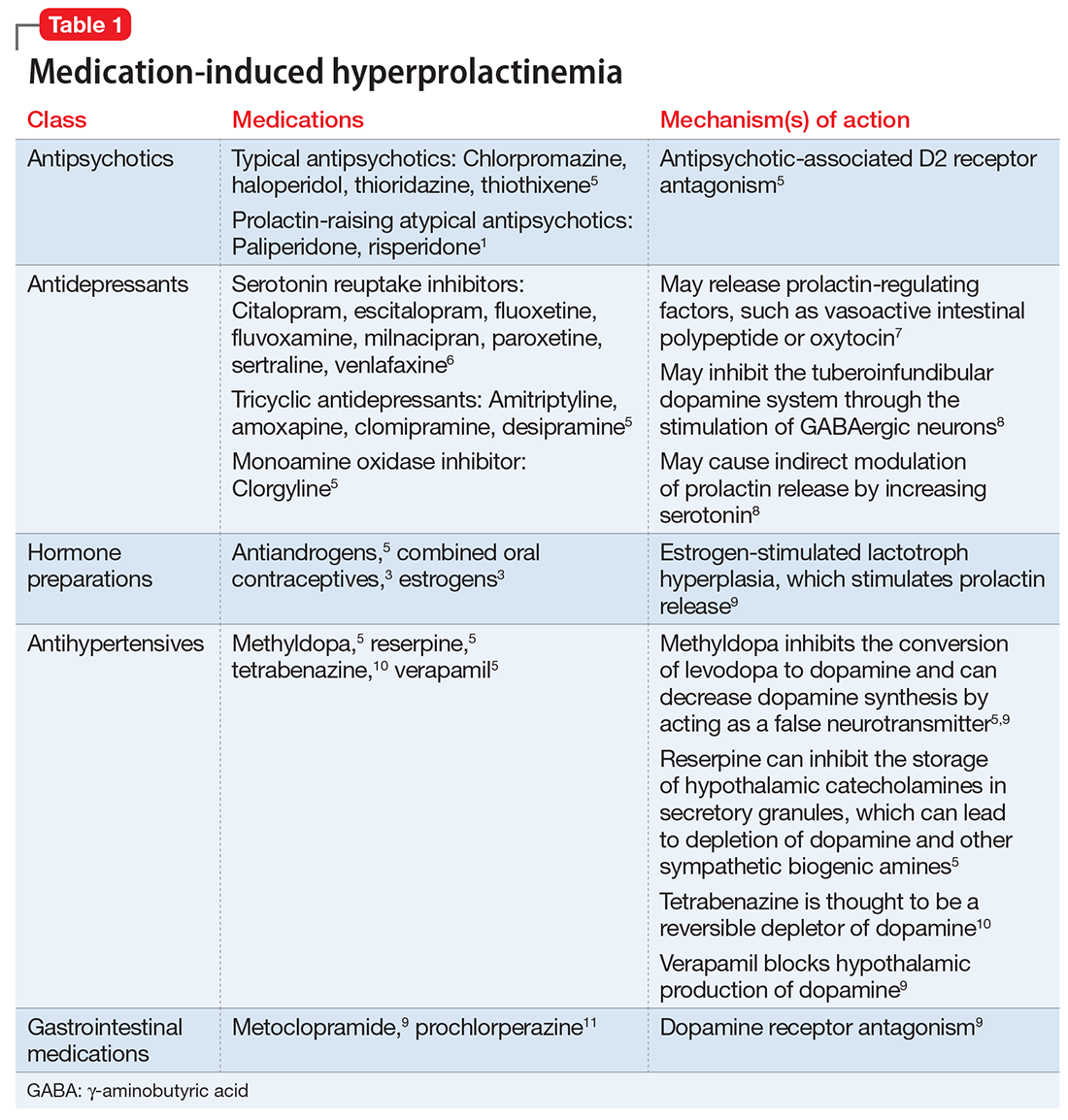

Antipsychotics, antidepressants, hormonal preparations, antihypertensives, and gastrointestinal agents have been associated with hyperprolactinemia (Table 11,3,5-11). These medication classes increase prolactin by decreasing dopamine, which facilitates disinhibition of prolactin synthesis and release, or increasing prolactin stimulating hormones, such as serotonin or estrogen.5

Antipsychotics are the most common medication-related cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 Typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause hyperprolactinemia than atypical antipsychotics; the incidence among patients taking typical antipsychotics is 40% to 90%.3 Atypical antipsychotics, except risperidone and paliperidone, are considered to cause less endocrinologic effects than typical antipsychotics through various mechanisms: serotonergic receptor antagonism, fast dissociation from D2 receptors, D2 receptor partial agonism, and preferential binding of D3 vs D2 receptors.1,5 By having transient D2 receptor association, clozapine and quetiapine are considered to have less risk of hyperprolactinemia compared with other atypical antipsychotics.1,5 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are partial D2 receptor agonists, and cariprazine is the only agent that exhibits preferential binding to D3 receptors.12,13 Based on limited data, brexpiprazole and cariprazine may have prolactin-sparing properties given their partial D2 receptor agonism.12,13 However, one study found increased prolactin levels in some patients after treatment with brexpiprazole, 4 mg/d.14 Similarly, another study found that cariprazine could increase prolactin levels as much as 4.1 ng/mL, depending on the dose.15 Except for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and clozapine, all other atypical antipsychotics marketed in the United States have a standard warning in the package insert regarding prolactin elevations.1,16,17

Because antidepressants are less well-studied as a cause of medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, drawing definitive conclusions regarding incidence rates is limited, but the incidence seems to be fairly low.6,18 A French pharmacovigilance study found that of 182,836 spontaneous adverse drug events reported between 1985 and 2009, there were 159 reports of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) inducing hyperprolactinemia.6 F

Mirtazapine and bupropion have been found to be prolactin-neutral.5 Bupropion also has been reported to decrease prolactin levels, potentially via its ability to block dopamine reuptake.19

Managing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Screening for and identifying clinically significant hyperprolactinemia is critical, because adverse effects of medications can lead to nonadherence and clinical decompensation.20 Patients must be informed of potential symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, and clinicians should inquire about such symptoms at each visit. Routine monitoring of prolactin levels in asymptomatic patients is not necessary, because the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline does not recommend treating patients with asymptomatic medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.3

In patients who report hyperprolactinemia symptoms, clinicians should review the patient’s prescribed medications and past medical history (eg, chronic renal failure, hypothyroidism) for potential causes or exacerbations, and address these factors accordingly.3 Order a measurement of prolactin level. A patient with a prolactin level >100 ng/mL should be referred to Endocrinology to rule out prolactinoma.1

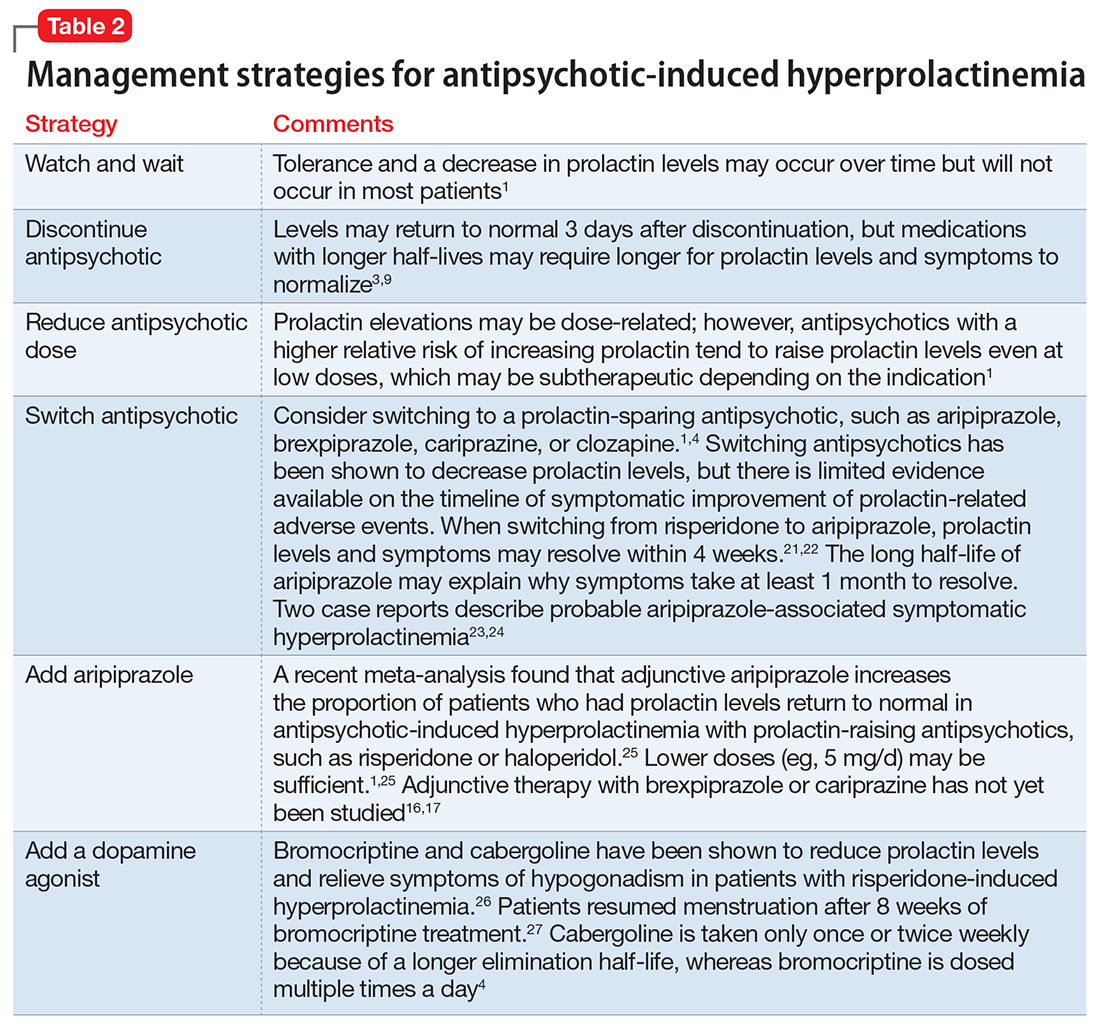

If a patient’s prolactin level is between 25 and 100 ng/mL, review the patient’s medications (Table 11,3,5-11), because prolactin levels within this range usually signal a medication-induced cause.3 For patients with antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia, there are several management strategies (Table 21,3,4,9,16,17,21-27):

- Watch and wait may be warranted when the patient is experiencing mild hyperprolactinemia symptoms.

- Discontinue. If the patient can be maintained without an antipsychotic, discontinuing the antipsychotic would be a first-line option.3

- Reduce the dose. Reducing the antipsychotic dose may be the preferred strategy for patients with moderate to severe hyperprolactinemia symptoms who responded to the antipsychotic and do not wish to start adjunctive therapy.4

- Switching to a prolactin-sparing antipsychotic may help normalize prolactin levels and may be preferred when the risk of relapse is low.3 Dopamine agonists can treat medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, but may worsen psychiatric symptoms.28,29 Therefore, this may be the preferred strategy if the offending medication cannot be discontinued or switched, or if the patient has a comorbid prolactinoma.

Less data exist on managing hyperprolactinemia that is induced by a medication other than an antipsychotic; however, it seems reasonable that the same strategies could be implemented. Specifically, for SSRI–induced hyperprolactinemia, if clinically appropriate, switching to or adding an alternative antidepressant that may be prolactin-sparing, such as mirtazapine or bupropion, could be attempted.8 One study found that fluoxetine-induced galactorrhea ceased within 10 days of discontinuing the medication.30

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. E has been on the same medication regimen for 3 years and recently developed galactorrhea, it seems unlikely that her hyperprolactinemia is medication-induced. However, a tumor-related cause is less likely because the prolactin level is <100 ng/mL. Based on the literature, the only possible medication-induced cause of her galactorrhea is risperidone. Ms. E agrees to a trial of adjunctive oral aripiprazole, 5 mg/d, with close monitoring of her type 2 diabetes mellitus. Because of the long elimination half-life of aripiprazole, 1 month is required to monitor for improvement in galactorrhea. Ms. E is advised to use breast pads as a nonpharmacologic strategy in the interim. After 1 month of treatment, Ms. E denies galactorrhea symptoms and no longer requires the use of breast pads.

1. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs.2014;28(5):421-453.

2. Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, et al. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(4):1523-1631.

3. Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Hoffman AR, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia: an Endocrine Society Clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(2):273-288.

4. Bostwick JR, Guthrie SK, Ellingrod VL. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(1):64-73.

5. La Torre D, Falorni A. Pharmacological causes of hyperprolactinemia. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(5):929-951.

6. Petit A, Piednoir D, Germain ML, et al. Drug-induced hyperprolactinemia: a case-non-case study from the national pharmacovigilance database [in French]. Therapie. 2003;58(2):159-163.

7. Emiliano AB, Fudge JL. From galactorrhea to osteopenia: rethinking serotonin-prolactin interactions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(5):833-846.

8. Coker F, Taylor D. Antidepressant-induced hyperprolactinaemia: incidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(7):563-574.

9. Molitch ME. Medication induced hyperprolactinemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(8):1050-1057.

10. Xenazine (tetrabenazine) [package insert]. Washington, DC: Prestwick Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2008.

11. Peña KS, Rosenfeld JA. Evaluation and treatment of galactorrhea. Am Fam Physician 2001;63(9):1763-1770.

12. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):63-75.

13. Das S, Barnwal P, Winston AB, et al. Brexpiprazole: so far so good. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(1):39-54.

14. Correll CU, Skuban A, Ouyang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole for the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(9):870-880.

15. Durgam S, Earley W, Guo H, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive cariprazine in inadequate responders to antidepressants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adult patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Pscyhiatry. 2016;77(3):371-378.

16. Rexulti (brexpiprazole) [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2015.

17. Cariprazine (Vraylar) [package insert]. Parsippany, New Jersey: Actavis Pharmacueitcals Inc.; 2015.

18. Marken PA, Haykal RF, Fisher JN. Management of psychotropic-induced hyperprolactinemia. Clin Pharm. 1992;11(10):851-856.

19. Meltzer HY, Fang VS, Tricou BJ, et al. Effect of antidepressants on neuroendocrine axis in humans. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1982;32:303-316.

20. Tsuboi T, Bies RR, Suzuki T, et al. Hyperprolactinemia and estimated dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia: analysis of the CATIE data. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:178-182.

21. Lee BH, Kim YK, Park SH. Using aripiprazole to resolve antipsychotic-induced symptomatic hyperprolactinemia: a pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(4):714-717.

22. Lu ML, Shen WW, Chen CH. Time course of the changes in antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia following the switch to aripiprazole. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(8):1978-1981.

23. Mendhekar DN, Andrade C. Galactorrhea with aripiprazole. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(4):243.

24. Joseph SP. Aripiprazole induced hyperprolactinemia in a young female with delusional disorder. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38(3):260-262.

25. Meng M, Li W, Zhang S, et al. Using aripiprazole to reduce antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: meta-analysis of currently available randomized controlled trials. Shaghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):4-17.

26. Tollin SR. Use of the dopamine agonists bromocriptine and cabergoline in the management of risperidone induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with psychotic disorders. J Endocrinol Invest. 2000;23(11):765-70.

27. Yuan HN, Wang CY, Sze CW, et al. A randomized, crossover comparison of herbal medicine and bromocriptine against risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(3):264-370.

28. Chang SC, Chen CH, Lu ML. Cabergoline-induced psychotic exacerbation in schizophrenic patients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2008;30(4):378-380.

29. Ishitobi M, Kosaka H, Shukunami K, et al. Adjunctive treatment with low-dosage pramipexole for risperidone-associated hyperprolactinemia and sexual dysfunction in a male patient with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;31(2):243-245.

30. Peterson MC. Reversible galactorrhea and prolactin elevation related to fluoxetine use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(2):215-216.

Ms. E, age 23, presents to your office for a routine visit for management of bipolar I disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus. She currently is taking

Ms. E has a history of self-discontinuing medication when adverse events occur. She has been hospitalized twice for psychosis and suicide attempts. Past psychotropic medications that have been discontinued due to adverse effects include ziprasidone (mild abnormal lip movement), olanzapine (ineffective and drowsy), valproic acid (tremor and abdominal discomfort), lithium (rash), and aripiprazole (increased fasting blood sugar and labile mood).

At her appointment today, Ms. E says she is concerned because she has been experiencing galactorrhea for the past 4 weeks. Her prolactin level is 14.4 ng/mL; a normal level for a woman who is not pregnant is <25 ng/mL. However, a repeat prolactin level is obtained, and is found to be elevated at 38 ng/mL.

Prolactin, a polypeptide hormone that is secreted from the pituitary gland, has many functions, including involvement in the synthesis and maintenance of breast milk production, in reproductive behavior, and in luteal function.1,2 Hyperprolactinemia—an elevated prolactin level—is a common endocrinologic disorder of the hypothalamic–pituitary–axis.3 Children, adolescents, premenopausal women, and women in the perinatal period are more vulnerable to medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.4 If not asymptomatic, patients with hyperprolactinemia may experience amenorrhea, galactorrhea, hypogonadism, sexual dysfunction, or infertility.1,4 Chronic hyperprolactinemia may increase the risk for long-term complications, such as decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis, although available evidence has conflicting findings.1

Hyperprolactinemia is diagnosed by a prolactin concentration above the upper reference range.3 Various hormones and neurotransmitters can impact inhibition or stimulation of prolactin release.5 For example, dopamine tonically inhibits prolactin release and synthesis, whereas estrogen stimulates prolactin secretion.1,5 Prolactin also can be elevated under several physiologic and pathologic conditions, such as during stressful situations, meals, or sexual activity.1,5 A prolactin level >250 ng/mL is usually indicative of a prolactinoma; however, some medications, such as strong D2 receptor antagonists (eg, risperidone, haloperidol), can cause significant elevation without evidence of prolactinoma.3 In the absence of a tumor, medications are often identified as the cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 According to the Endocrinology Society clinical practice guideline, medication-induced elevated prolactin levels are typically between 25 to 100 ng/mL.3

Medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Antipsychotics, antidepressants, hormonal preparations, antihypertensives, and gastrointestinal agents have been associated with hyperprolactinemia (Table 11,3,5-11). These medication classes increase prolactin by decreasing dopamine, which facilitates disinhibition of prolactin synthesis and release, or increasing prolactin stimulating hormones, such as serotonin or estrogen.5

Antipsychotics are the most common medication-related cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 Typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause hyperprolactinemia than atypical antipsychotics; the incidence among patients taking typical antipsychotics is 40% to 90%.3 Atypical antipsychotics, except risperidone and paliperidone, are considered to cause less endocrinologic effects than typical antipsychotics through various mechanisms: serotonergic receptor antagonism, fast dissociation from D2 receptors, D2 receptor partial agonism, and preferential binding of D3 vs D2 receptors.1,5 By having transient D2 receptor association, clozapine and quetiapine are considered to have less risk of hyperprolactinemia compared with other atypical antipsychotics.1,5 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are partial D2 receptor agonists, and cariprazine is the only agent that exhibits preferential binding to D3 receptors.12,13 Based on limited data, brexpiprazole and cariprazine may have prolactin-sparing properties given their partial D2 receptor agonism.12,13 However, one study found increased prolactin levels in some patients after treatment with brexpiprazole, 4 mg/d.14 Similarly, another study found that cariprazine could increase prolactin levels as much as 4.1 ng/mL, depending on the dose.15 Except for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and clozapine, all other atypical antipsychotics marketed in the United States have a standard warning in the package insert regarding prolactin elevations.1,16,17

Because antidepressants are less well-studied as a cause of medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, drawing definitive conclusions regarding incidence rates is limited, but the incidence seems to be fairly low.6,18 A French pharmacovigilance study found that of 182,836 spontaneous adverse drug events reported between 1985 and 2009, there were 159 reports of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) inducing hyperprolactinemia.6 F

Mirtazapine and bupropion have been found to be prolactin-neutral.5 Bupropion also has been reported to decrease prolactin levels, potentially via its ability to block dopamine reuptake.19

Managing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Screening for and identifying clinically significant hyperprolactinemia is critical, because adverse effects of medications can lead to nonadherence and clinical decompensation.20 Patients must be informed of potential symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, and clinicians should inquire about such symptoms at each visit. Routine monitoring of prolactin levels in asymptomatic patients is not necessary, because the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline does not recommend treating patients with asymptomatic medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.3

In patients who report hyperprolactinemia symptoms, clinicians should review the patient’s prescribed medications and past medical history (eg, chronic renal failure, hypothyroidism) for potential causes or exacerbations, and address these factors accordingly.3 Order a measurement of prolactin level. A patient with a prolactin level >100 ng/mL should be referred to Endocrinology to rule out prolactinoma.1

If a patient’s prolactin level is between 25 and 100 ng/mL, review the patient’s medications (Table 11,3,5-11), because prolactin levels within this range usually signal a medication-induced cause.3 For patients with antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia, there are several management strategies (Table 21,3,4,9,16,17,21-27):

- Watch and wait may be warranted when the patient is experiencing mild hyperprolactinemia symptoms.

- Discontinue. If the patient can be maintained without an antipsychotic, discontinuing the antipsychotic would be a first-line option.3

- Reduce the dose. Reducing the antipsychotic dose may be the preferred strategy for patients with moderate to severe hyperprolactinemia symptoms who responded to the antipsychotic and do not wish to start adjunctive therapy.4

- Switching to a prolactin-sparing antipsychotic may help normalize prolactin levels and may be preferred when the risk of relapse is low.3 Dopamine agonists can treat medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, but may worsen psychiatric symptoms.28,29 Therefore, this may be the preferred strategy if the offending medication cannot be discontinued or switched, or if the patient has a comorbid prolactinoma.

Less data exist on managing hyperprolactinemia that is induced by a medication other than an antipsychotic; however, it seems reasonable that the same strategies could be implemented. Specifically, for SSRI–induced hyperprolactinemia, if clinically appropriate, switching to or adding an alternative antidepressant that may be prolactin-sparing, such as mirtazapine or bupropion, could be attempted.8 One study found that fluoxetine-induced galactorrhea ceased within 10 days of discontinuing the medication.30

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. E has been on the same medication regimen for 3 years and recently developed galactorrhea, it seems unlikely that her hyperprolactinemia is medication-induced. However, a tumor-related cause is less likely because the prolactin level is <100 ng/mL. Based on the literature, the only possible medication-induced cause of her galactorrhea is risperidone. Ms. E agrees to a trial of adjunctive oral aripiprazole, 5 mg/d, with close monitoring of her type 2 diabetes mellitus. Because of the long elimination half-life of aripiprazole, 1 month is required to monitor for improvement in galactorrhea. Ms. E is advised to use breast pads as a nonpharmacologic strategy in the interim. After 1 month of treatment, Ms. E denies galactorrhea symptoms and no longer requires the use of breast pads.

Ms. E, age 23, presents to your office for a routine visit for management of bipolar I disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder with comorbid type 2 diabetes mellitus. She currently is taking

Ms. E has a history of self-discontinuing medication when adverse events occur. She has been hospitalized twice for psychosis and suicide attempts. Past psychotropic medications that have been discontinued due to adverse effects include ziprasidone (mild abnormal lip movement), olanzapine (ineffective and drowsy), valproic acid (tremor and abdominal discomfort), lithium (rash), and aripiprazole (increased fasting blood sugar and labile mood).

At her appointment today, Ms. E says she is concerned because she has been experiencing galactorrhea for the past 4 weeks. Her prolactin level is 14.4 ng/mL; a normal level for a woman who is not pregnant is <25 ng/mL. However, a repeat prolactin level is obtained, and is found to be elevated at 38 ng/mL.

Prolactin, a polypeptide hormone that is secreted from the pituitary gland, has many functions, including involvement in the synthesis and maintenance of breast milk production, in reproductive behavior, and in luteal function.1,2 Hyperprolactinemia—an elevated prolactin level—is a common endocrinologic disorder of the hypothalamic–pituitary–axis.3 Children, adolescents, premenopausal women, and women in the perinatal period are more vulnerable to medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.4 If not asymptomatic, patients with hyperprolactinemia may experience amenorrhea, galactorrhea, hypogonadism, sexual dysfunction, or infertility.1,4 Chronic hyperprolactinemia may increase the risk for long-term complications, such as decreased bone mineral density and osteoporosis, although available evidence has conflicting findings.1

Hyperprolactinemia is diagnosed by a prolactin concentration above the upper reference range.3 Various hormones and neurotransmitters can impact inhibition or stimulation of prolactin release.5 For example, dopamine tonically inhibits prolactin release and synthesis, whereas estrogen stimulates prolactin secretion.1,5 Prolactin also can be elevated under several physiologic and pathologic conditions, such as during stressful situations, meals, or sexual activity.1,5 A prolactin level >250 ng/mL is usually indicative of a prolactinoma; however, some medications, such as strong D2 receptor antagonists (eg, risperidone, haloperidol), can cause significant elevation without evidence of prolactinoma.3 In the absence of a tumor, medications are often identified as the cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 According to the Endocrinology Society clinical practice guideline, medication-induced elevated prolactin levels are typically between 25 to 100 ng/mL.3

Medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Antipsychotics, antidepressants, hormonal preparations, antihypertensives, and gastrointestinal agents have been associated with hyperprolactinemia (Table 11,3,5-11). These medication classes increase prolactin by decreasing dopamine, which facilitates disinhibition of prolactin synthesis and release, or increasing prolactin stimulating hormones, such as serotonin or estrogen.5

Antipsychotics are the most common medication-related cause of hyperprolactinemia.3 Typical antipsychotics are more likely to cause hyperprolactinemia than atypical antipsychotics; the incidence among patients taking typical antipsychotics is 40% to 90%.3 Atypical antipsychotics, except risperidone and paliperidone, are considered to cause less endocrinologic effects than typical antipsychotics through various mechanisms: serotonergic receptor antagonism, fast dissociation from D2 receptors, D2 receptor partial agonism, and preferential binding of D3 vs D2 receptors.1,5 By having transient D2 receptor association, clozapine and quetiapine are considered to have less risk of hyperprolactinemia compared with other atypical antipsychotics.1,5 Aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, and cariprazine are partial D2 receptor agonists, and cariprazine is the only agent that exhibits preferential binding to D3 receptors.12,13 Based on limited data, brexpiprazole and cariprazine may have prolactin-sparing properties given their partial D2 receptor agonism.12,13 However, one study found increased prolactin levels in some patients after treatment with brexpiprazole, 4 mg/d.14 Similarly, another study found that cariprazine could increase prolactin levels as much as 4.1 ng/mL, depending on the dose.15 Except for aripiprazole, brexpiprazole, cariprazine, and clozapine, all other atypical antipsychotics marketed in the United States have a standard warning in the package insert regarding prolactin elevations.1,16,17

Because antidepressants are less well-studied as a cause of medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, drawing definitive conclusions regarding incidence rates is limited, but the incidence seems to be fairly low.6,18 A French pharmacovigilance study found that of 182,836 spontaneous adverse drug events reported between 1985 and 2009, there were 159 reports of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) inducing hyperprolactinemia.6 F

Mirtazapine and bupropion have been found to be prolactin-neutral.5 Bupropion also has been reported to decrease prolactin levels, potentially via its ability to block dopamine reuptake.19

Managing medication-induced hyperprolactinemia

Screening for and identifying clinically significant hyperprolactinemia is critical, because adverse effects of medications can lead to nonadherence and clinical decompensation.20 Patients must be informed of potential symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, and clinicians should inquire about such symptoms at each visit. Routine monitoring of prolactin levels in asymptomatic patients is not necessary, because the Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline does not recommend treating patients with asymptomatic medication-induced hyperprolactinemia.3

In patients who report hyperprolactinemia symptoms, clinicians should review the patient’s prescribed medications and past medical history (eg, chronic renal failure, hypothyroidism) for potential causes or exacerbations, and address these factors accordingly.3 Order a measurement of prolactin level. A patient with a prolactin level >100 ng/mL should be referred to Endocrinology to rule out prolactinoma.1

If a patient’s prolactin level is between 25 and 100 ng/mL, review the patient’s medications (Table 11,3,5-11), because prolactin levels within this range usually signal a medication-induced cause.3 For patients with antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia, there are several management strategies (Table 21,3,4,9,16,17,21-27):

- Watch and wait may be warranted when the patient is experiencing mild hyperprolactinemia symptoms.

- Discontinue. If the patient can be maintained without an antipsychotic, discontinuing the antipsychotic would be a first-line option.3

- Reduce the dose. Reducing the antipsychotic dose may be the preferred strategy for patients with moderate to severe hyperprolactinemia symptoms who responded to the antipsychotic and do not wish to start adjunctive therapy.4

- Switching to a prolactin-sparing antipsychotic may help normalize prolactin levels and may be preferred when the risk of relapse is low.3 Dopamine agonists can treat medication-induced hyperprolactinemia, but may worsen psychiatric symptoms.28,29 Therefore, this may be the preferred strategy if the offending medication cannot be discontinued or switched, or if the patient has a comorbid prolactinoma.

Less data exist on managing hyperprolactinemia that is induced by a medication other than an antipsychotic; however, it seems reasonable that the same strategies could be implemented. Specifically, for SSRI–induced hyperprolactinemia, if clinically appropriate, switching to or adding an alternative antidepressant that may be prolactin-sparing, such as mirtazapine or bupropion, could be attempted.8 One study found that fluoxetine-induced galactorrhea ceased within 10 days of discontinuing the medication.30

CASE CONTINUED

Because Ms. E has been on the same medication regimen for 3 years and recently developed galactorrhea, it seems unlikely that her hyperprolactinemia is medication-induced. However, a tumor-related cause is less likely because the prolactin level is <100 ng/mL. Based on the literature, the only possible medication-induced cause of her galactorrhea is risperidone. Ms. E agrees to a trial of adjunctive oral aripiprazole, 5 mg/d, with close monitoring of her type 2 diabetes mellitus. Because of the long elimination half-life of aripiprazole, 1 month is required to monitor for improvement in galactorrhea. Ms. E is advised to use breast pads as a nonpharmacologic strategy in the interim. After 1 month of treatment, Ms. E denies galactorrhea symptoms and no longer requires the use of breast pads.

1. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs.2014;28(5):421-453.

2. Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, et al. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(4):1523-1631.

3. Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Hoffman AR, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia: an Endocrine Society Clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(2):273-288.

4. Bostwick JR, Guthrie SK, Ellingrod VL. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(1):64-73.

5. La Torre D, Falorni A. Pharmacological causes of hyperprolactinemia. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(5):929-951.

6. Petit A, Piednoir D, Germain ML, et al. Drug-induced hyperprolactinemia: a case-non-case study from the national pharmacovigilance database [in French]. Therapie. 2003;58(2):159-163.

7. Emiliano AB, Fudge JL. From galactorrhea to osteopenia: rethinking serotonin-prolactin interactions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(5):833-846.

8. Coker F, Taylor D. Antidepressant-induced hyperprolactinaemia: incidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(7):563-574.

9. Molitch ME. Medication induced hyperprolactinemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(8):1050-1057.

10. Xenazine (tetrabenazine) [package insert]. Washington, DC: Prestwick Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2008.

11. Peña KS, Rosenfeld JA. Evaluation and treatment of galactorrhea. Am Fam Physician 2001;63(9):1763-1770.

12. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):63-75.

13. Das S, Barnwal P, Winston AB, et al. Brexpiprazole: so far so good. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(1):39-54.

14. Correll CU, Skuban A, Ouyang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole for the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(9):870-880.

15. Durgam S, Earley W, Guo H, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive cariprazine in inadequate responders to antidepressants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adult patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Pscyhiatry. 2016;77(3):371-378.

16. Rexulti (brexpiprazole) [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2015.

17. Cariprazine (Vraylar) [package insert]. Parsippany, New Jersey: Actavis Pharmacueitcals Inc.; 2015.

18. Marken PA, Haykal RF, Fisher JN. Management of psychotropic-induced hyperprolactinemia. Clin Pharm. 1992;11(10):851-856.

19. Meltzer HY, Fang VS, Tricou BJ, et al. Effect of antidepressants on neuroendocrine axis in humans. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1982;32:303-316.

20. Tsuboi T, Bies RR, Suzuki T, et al. Hyperprolactinemia and estimated dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia: analysis of the CATIE data. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:178-182.

21. Lee BH, Kim YK, Park SH. Using aripiprazole to resolve antipsychotic-induced symptomatic hyperprolactinemia: a pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(4):714-717.

22. Lu ML, Shen WW, Chen CH. Time course of the changes in antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia following the switch to aripiprazole. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(8):1978-1981.

23. Mendhekar DN, Andrade C. Galactorrhea with aripiprazole. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(4):243.

24. Joseph SP. Aripiprazole induced hyperprolactinemia in a young female with delusional disorder. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38(3):260-262.

25. Meng M, Li W, Zhang S, et al. Using aripiprazole to reduce antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: meta-analysis of currently available randomized controlled trials. Shaghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):4-17.

26. Tollin SR. Use of the dopamine agonists bromocriptine and cabergoline in the management of risperidone induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with psychotic disorders. J Endocrinol Invest. 2000;23(11):765-70.

27. Yuan HN, Wang CY, Sze CW, et al. A randomized, crossover comparison of herbal medicine and bromocriptine against risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(3):264-370.

28. Chang SC, Chen CH, Lu ML. Cabergoline-induced psychotic exacerbation in schizophrenic patients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2008;30(4):378-380.

29. Ishitobi M, Kosaka H, Shukunami K, et al. Adjunctive treatment with low-dosage pramipexole for risperidone-associated hyperprolactinemia and sexual dysfunction in a male patient with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;31(2):243-245.

30. Peterson MC. Reversible galactorrhea and prolactin elevation related to fluoxetine use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(2):215-216.

1. Peuskens J, Pani L, Detraux J, et al. The effects of novel and newly approved antipsychotics on serum prolactin levels: a comprehensive review. CNS Drugs.2014;28(5):421-453.

2. Freeman ME, Kanyicska B, Lerant A, et al. Prolactin: structure, function, and regulation of secretion. Physiol Rev. 2000;80(4):1523-1631.

3. Melmed S, Casanueva FF, Hoffman AR, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of hyperprolactinemia: an Endocrine Society Clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(2):273-288.

4. Bostwick JR, Guthrie SK, Ellingrod VL. Antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia. Pharmacotherapy. 2009;29(1):64-73.

5. La Torre D, Falorni A. Pharmacological causes of hyperprolactinemia. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2007;3(5):929-951.

6. Petit A, Piednoir D, Germain ML, et al. Drug-induced hyperprolactinemia: a case-non-case study from the national pharmacovigilance database [in French]. Therapie. 2003;58(2):159-163.

7. Emiliano AB, Fudge JL. From galactorrhea to osteopenia: rethinking serotonin-prolactin interactions. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29(5):833-846.

8. Coker F, Taylor D. Antidepressant-induced hyperprolactinaemia: incidence, mechanisms and management. CNS Drugs. 2010;24(7):563-574.

9. Molitch ME. Medication induced hyperprolactinemia. Mayo Clin Proc. 2005;80(8):1050-1057.

10. Xenazine (tetrabenazine) [package insert]. Washington, DC: Prestwick Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2008.

11. Peña KS, Rosenfeld JA. Evaluation and treatment of galactorrhea. Am Fam Physician 2001;63(9):1763-1770.

12. Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. The efficacy and tolerability of cariprazine in acute mania associated with bipolar I disorder: a phase II trial. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(1):63-75.

13. Das S, Barnwal P, Winston AB, et al. Brexpiprazole: so far so good. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(1):39-54.

14. Correll CU, Skuban A, Ouyang J, et al. Efficacy and safety of brexpiprazole for the treatment of acute schizophrenia: a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172(9):870-880.

15. Durgam S, Earley W, Guo H, et al. Efficacy and safety of adjunctive cariprazine in inadequate responders to antidepressants: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in adult patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Pscyhiatry. 2016;77(3):371-378.

16. Rexulti (brexpiprazole) [package insert]. Tokyo, Japan: Otsuka Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2015.

17. Cariprazine (Vraylar) [package insert]. Parsippany, New Jersey: Actavis Pharmacueitcals Inc.; 2015.

18. Marken PA, Haykal RF, Fisher JN. Management of psychotropic-induced hyperprolactinemia. Clin Pharm. 1992;11(10):851-856.

19. Meltzer HY, Fang VS, Tricou BJ, et al. Effect of antidepressants on neuroendocrine axis in humans. Adv Biochem Psychopharmacol. 1982;32:303-316.

20. Tsuboi T, Bies RR, Suzuki T, et al. Hyperprolactinemia and estimated dopamine D2 receptor occupancy in patients with schizophrenia: analysis of the CATIE data. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2013;45:178-182.

21. Lee BH, Kim YK, Park SH. Using aripiprazole to resolve antipsychotic-induced symptomatic hyperprolactinemia: a pilot study. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30(4):714-717.

22. Lu ML, Shen WW, Chen CH. Time course of the changes in antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia following the switch to aripiprazole. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(8):1978-1981.

23. Mendhekar DN, Andrade C. Galactorrhea with aripiprazole. Can J Psychiatry. 2005;50(4):243.

24. Joseph SP. Aripiprazole induced hyperprolactinemia in a young female with delusional disorder. Indian J Psychol Med. 2016;38(3):260-262.

25. Meng M, Li W, Zhang S, et al. Using aripiprazole to reduce antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia: meta-analysis of currently available randomized controlled trials. Shaghai Arch Psychiatry. 2015;27(1):4-17.

26. Tollin SR. Use of the dopamine agonists bromocriptine and cabergoline in the management of risperidone induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with psychotic disorders. J Endocrinol Invest. 2000;23(11):765-70.

27. Yuan HN, Wang CY, Sze CW, et al. A randomized, crossover comparison of herbal medicine and bromocriptine against risperidone-induced hyperprolactinemia in patients with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28(3):264-370.

28. Chang SC, Chen CH, Lu ML. Cabergoline-induced psychotic exacerbation in schizophrenic patients. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2008;30(4):378-380.

29. Ishitobi M, Kosaka H, Shukunami K, et al. Adjunctive treatment with low-dosage pramipexole for risperidone-associated hyperprolactinemia and sexual dysfunction in a male patient with schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol 2011;31(2):243-245.

30. Peterson MC. Reversible galactorrhea and prolactin elevation related to fluoxetine use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2001;76(2):215-216.